↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep neural networks, particularly Transformer-like models, are often viewed as ‘black boxes’. Understanding their inner workings is critical to improving their design and generalization capabilities. Existing research into model interpretability often relies on experimental observation, which lacks theoretical grounding. A recent approach, Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR), offers a more principled information-theoretic method. However, this approach has not been fully optimized or studied in practice.

This paper delves into the SRR optimization, analyzing the behavior of CRATE (Coding Rate Reduction Transformer). The authors find flaws in the original CRATE implementation and introduce improved versions. They show a positive correlation between SRR and generalization performance, suggesting SRR can serve as a complexity measure and propose improving generalization by using SRR as a regularization technique. This approach consistently improves model performance on benchmark image classification datasets, demonstrating its potential for practical applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on Transformer-like models and generalization in deep learning. It offers valuable insights into the optimization process of existing models, suggesting improvements and providing a new regularization technique. It also opens avenues for further research into principled model design and the relationship between complexity measures and generalization.

Visual Insights#

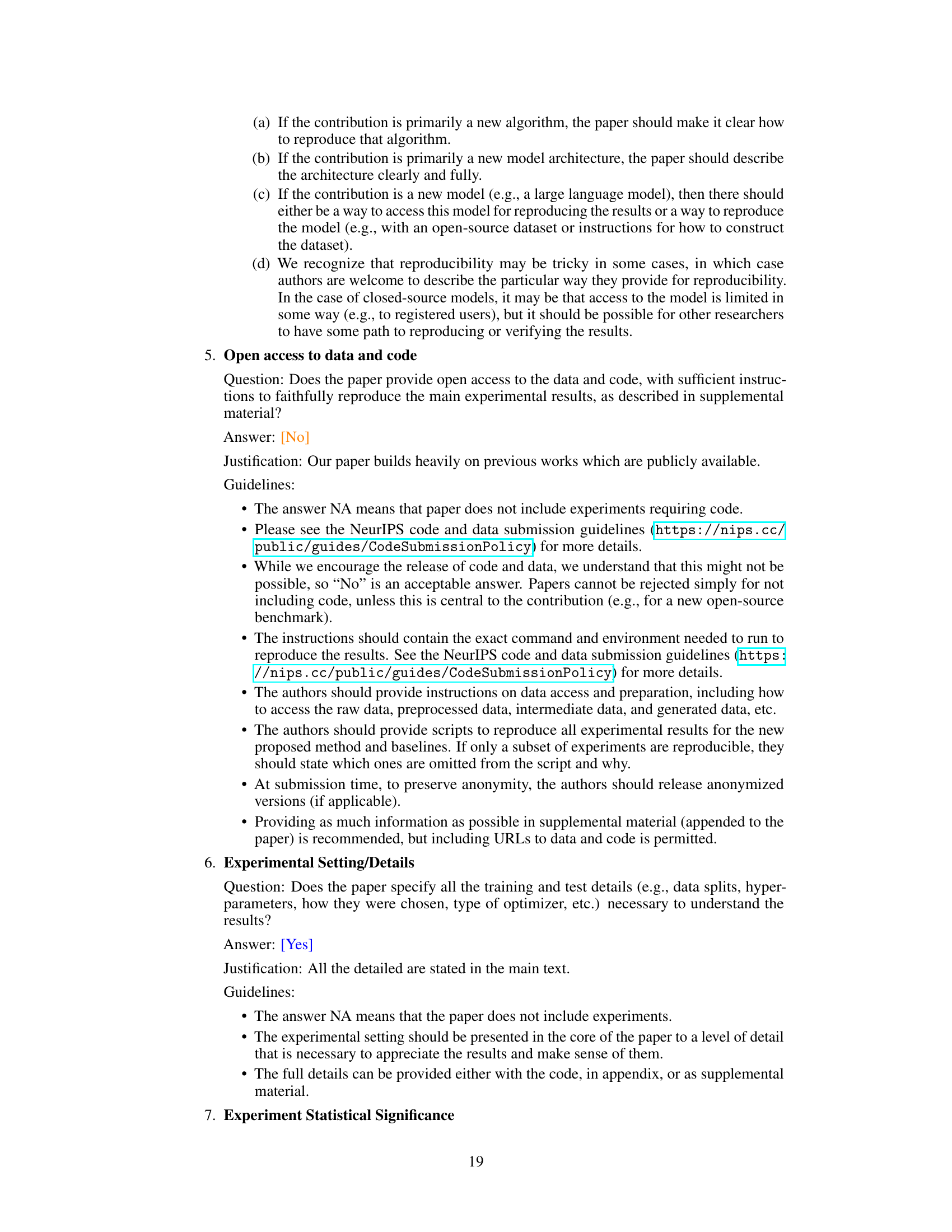

This figure shows the results of a simplified attention-only experiment. The left panel (a) demonstrates that the MSSA (Multi-head Subspace Self-Attention) operator with a skip connection, a core component of the CRATE model, unexpectedly increases the coding rate Rº(Z;U) across layers instead of decreasing it as intended. The right panel (b) visually explains this behavior by showing that the approximation used in deriving the MSSA operator, specifically omitting the first-order term in the Taylor expansion of the coding rate, leads to an ascent instead of descent on the coding rate, hence explaining the counter-intuitive result of the experiment in (a).

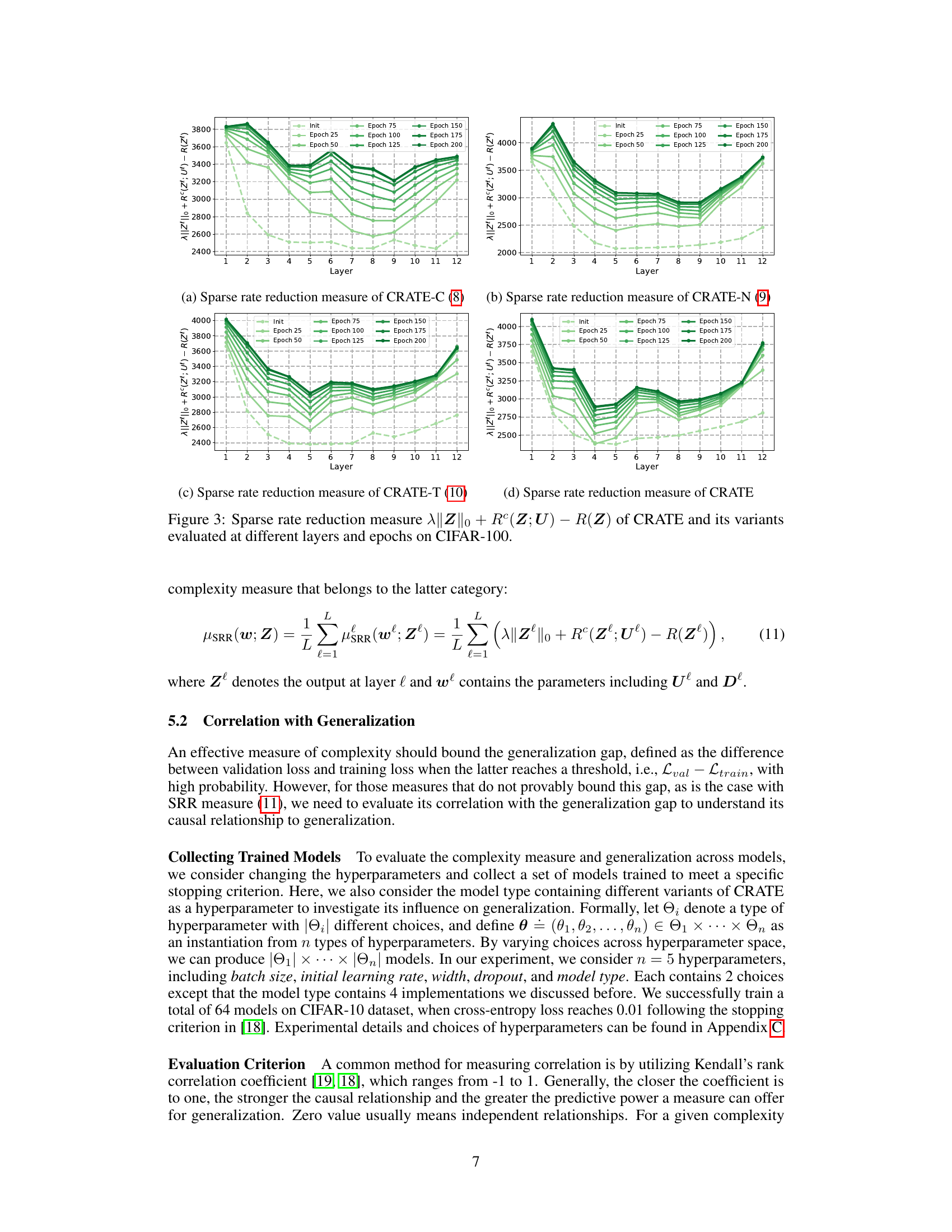

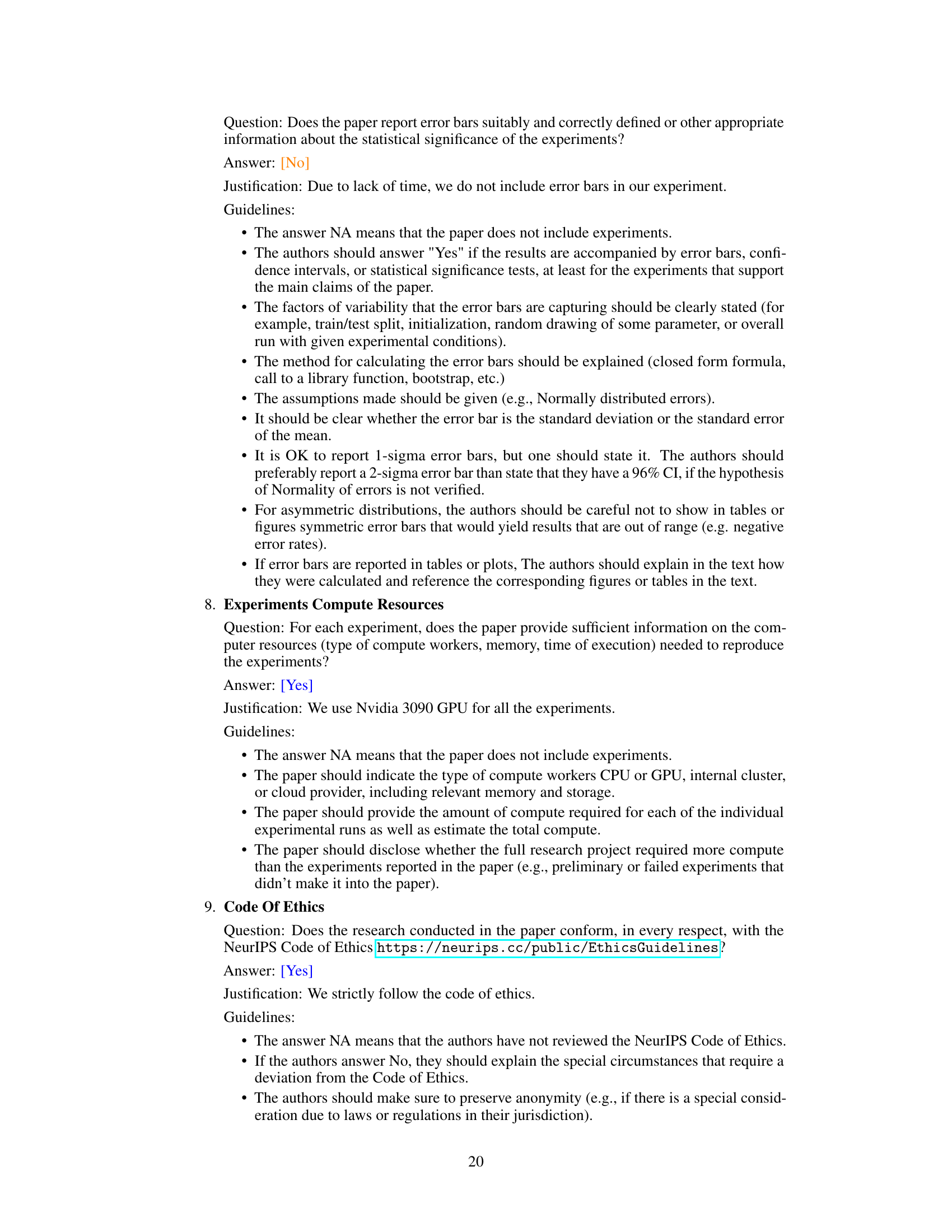

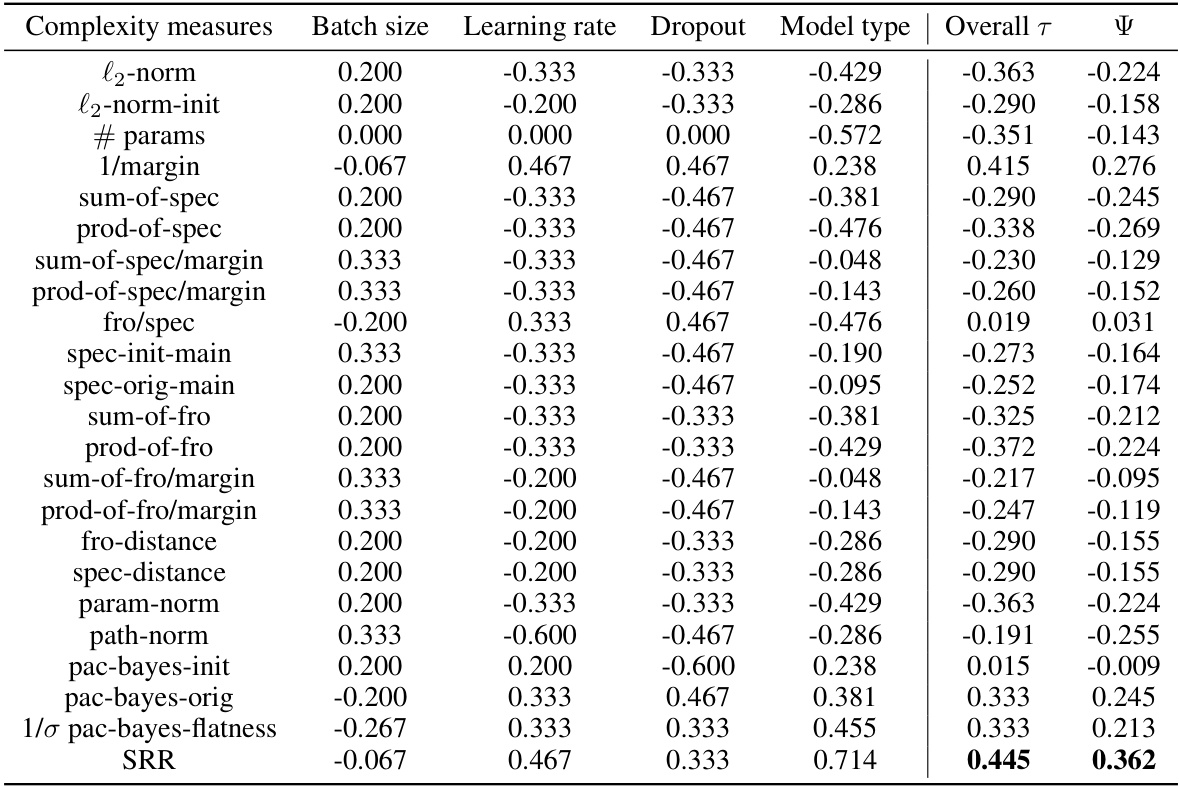

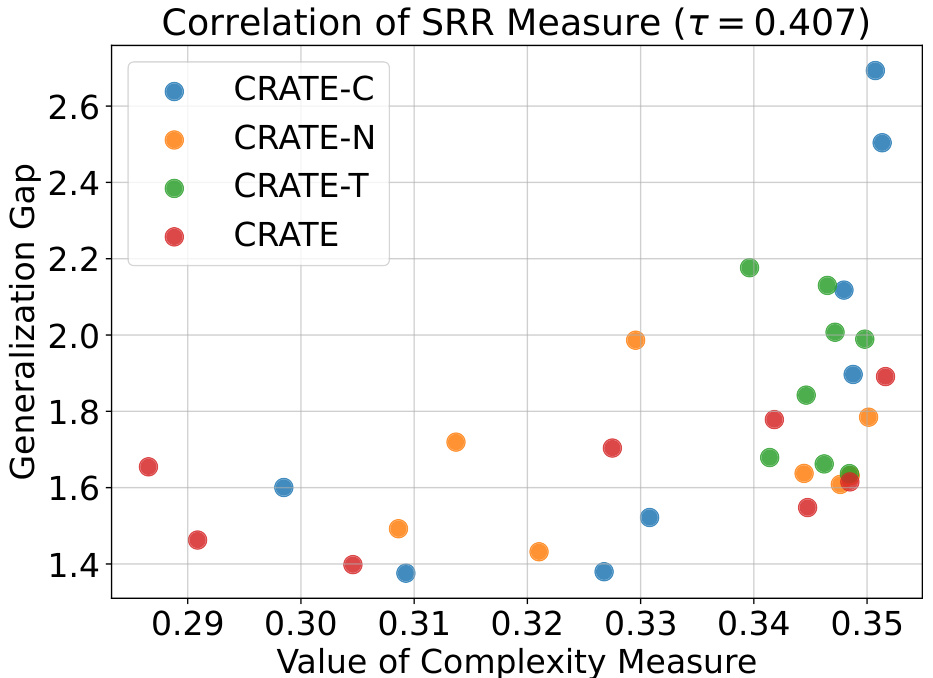

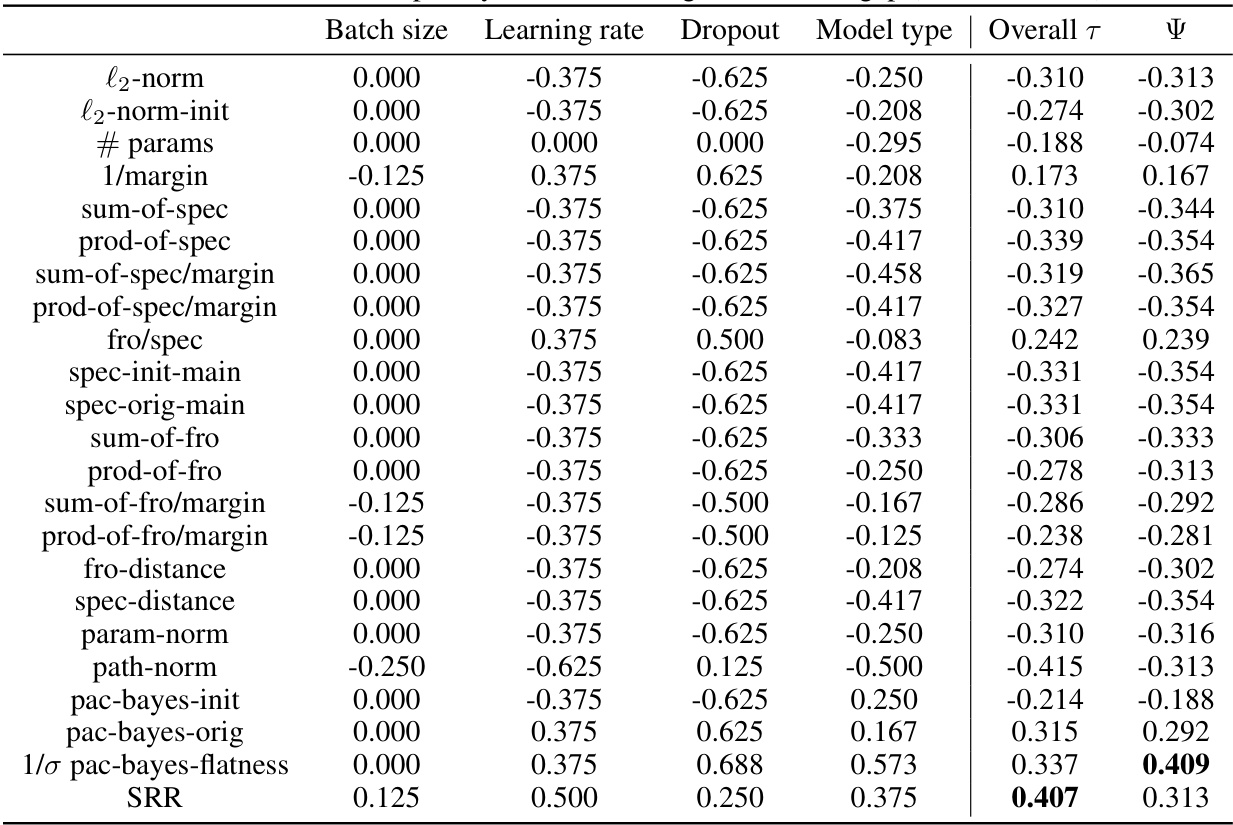

This table presents the Kendall’s rank correlation coefficients between different complexity measures and the generalization gap for Transformer-like models. The complexity measures considered include various norm-based metrics (l2-norm, path-norm, etc.), spectral-based metrics (sum-of-spec, prod-of-spec, etc.), margin-based metrics (1/margin), and the Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) measure. The table shows the correlation for each measure across different hyperparameter settings (batch size, learning rate, dropout, and model type), providing an overall correlation coefficient. A higher correlation indicates a stronger relationship between the complexity measure and generalization performance. The width of the network (d) is fixed at 384 for this analysis.

In-depth insights#

SRR’s Predictive Power#

The research investigates the predictive power of Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) as a measure of model complexity for generalization in transformer-like models. The core finding is that SRR exhibits a positive correlation with generalization performance, outperforming baselines like path-norm and sharpness-based measures. This suggests that SRR effectively captures the relationship between model complexity and generalization ability. A key contribution is the demonstration that improved generalization can be achieved by using SRR as a regularization term during training. The study provides strong empirical evidence supporting SRR’s utility but acknowledges the need for further theoretical investigation to fully understand its causal relationship to generalization. The research highlights the potential of SRR as a principled tool for both model design and improvement of generalization capabilities in transformer-like architectures.

CRATE’s Optimization#

The core of the paper revolves around the analysis and optimization of the Coding Rate Reduction Transformer (CRATE). CRATE’s optimization is fundamentally based on the Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) objective, aiming to maximize information gain while promoting sparsity in representations. The authors meticulously dissect CRATE’s layer-wise behavior, revealing a crucial flaw in the original derivation of CRATE’s core component—the Multi-head Subspace Self-Attention (MSSA) operator. This flaw leads to a counterintuitive effect: instead of compression, the original CRATE implementation performs decompression. To address this, they propose two variations: CRATE-N and CRATE-T, offering improved alignment with the SRR principle and enhanced performance. The investigation uncovers a positive correlation between SRR and generalization, suggesting SRR can serve as a valuable complexity measure. This finding then motivates using SRR as a regularization technique, which is empirically demonstrated to improve model generalization on benchmark image classification datasets.

SRR Regularization#

The study explores using Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) as a regularization technique in Transformer-like models. SRR, initially proposed as an information-theoretic objective function, is shown to correlate positively with generalization performance. The authors investigate various implementations of SRR, revealing potential pitfalls in the original derivation and proposing alternative variants. Experimental results demonstrate that incorporating SRR as a regularizer consistently improves generalization on benchmark image classification datasets, suggesting its utility beyond its original theoretical interpretation. This approach is particularly interesting because it leverages an interpretable objective function to guide model training, potentially addressing the ‘black box’ nature of deep learning models. The efficient implementation of SRR regularization is also discussed, highlighting the practical implications of this research.

Model Variants#

The exploration of model variants is crucial for understanding the behavior and limitations of the Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) framework. The authors cleverly create variations of the core CRATE model, such as CRATE-C, CRATE-N, and CRATE-T, each addressing specific limitations or design choices of the original model. This methodical approach allows for a deeper understanding of SRR’s sensitivity to architectural decisions and parameter choices. By empirically comparing these variants, the authors can pinpoint the reasons for successes and failures, highlighting the nuances of the SRR optimization process. This targeted experimentation is key to isolating the effects of different components, particularly the MSSA operator. Moreover, the use of variants allows assessment of the robustness and generality of SRR’s predictive power regarding model generalization. The generation of various models is not merely an implementation exercise; rather, it constitutes a crucial step in validating the SRR theoretical framework, establishing its capabilities and limitations.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion suggests several promising avenues for future research. Extending the sparse rate reduction (SRR) framework to standard Transformers is crucial, as the current formulation relies on specific matrix properties not present in standard architectures. Investigating the impact of depth in unrolled models could reveal further insights into SRR’s optimization capabilities. Connecting SRR to the forward-forward algorithm warrants exploration, potentially leading to more efficient training methods. Finally, a more rigorous empirical evaluation is needed to solidify SRR’s role as a principled complexity measure and predictive tool for generalization across diverse architectures and datasets. This comprehensive investigation will strengthen SRR’s standing as a valuable tool in both model design and the understanding of deep learning generalization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows the results of a simplified attention-only experiment. The left panel shows that the MSSA operator with skip connection, which is designed to implement a descent method on Rº(Z; U), actually implements an ascent method. The right panel shows that this is due to an artifact in the approximation of the second-order term in the Taylor expansion of Rº(Z; U).

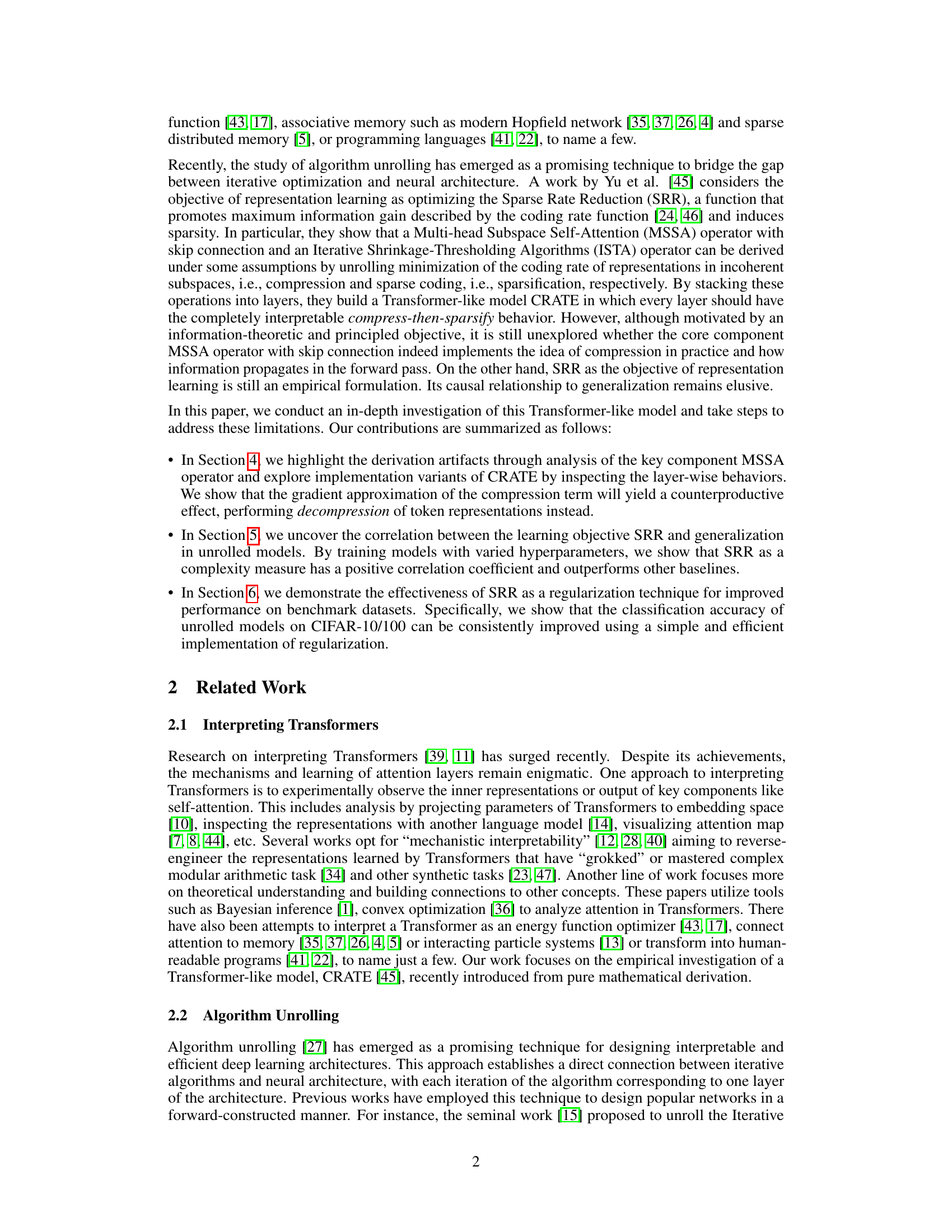

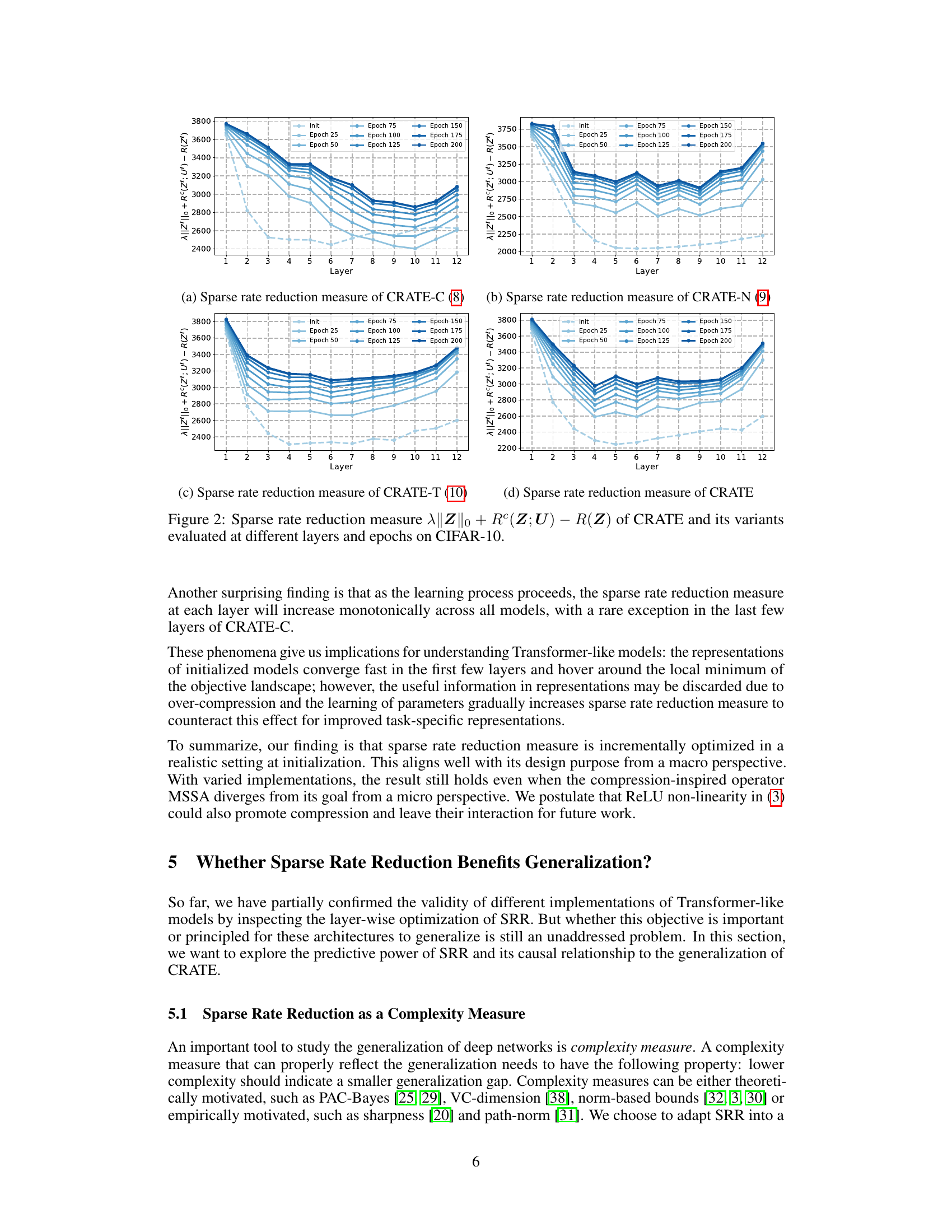

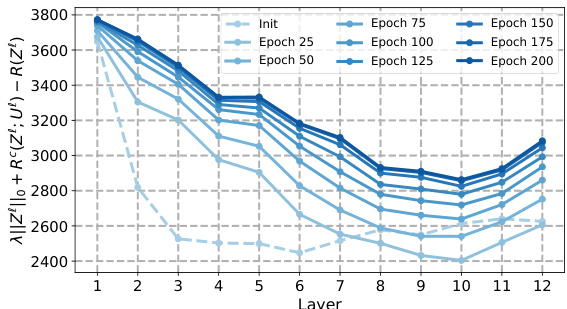

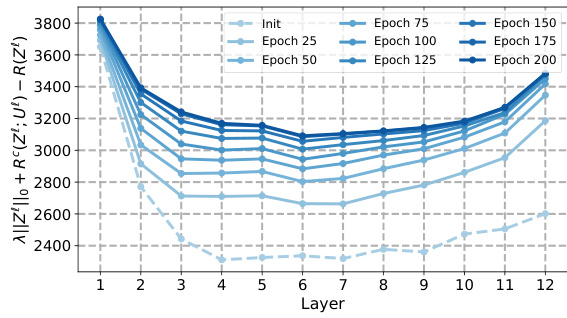

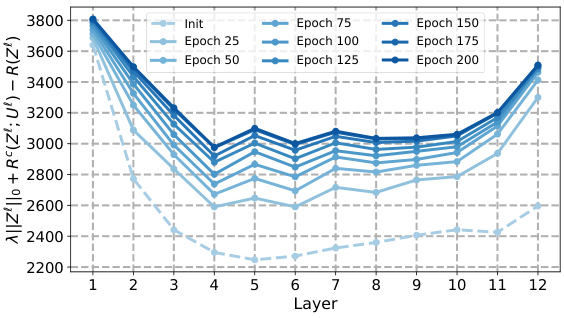

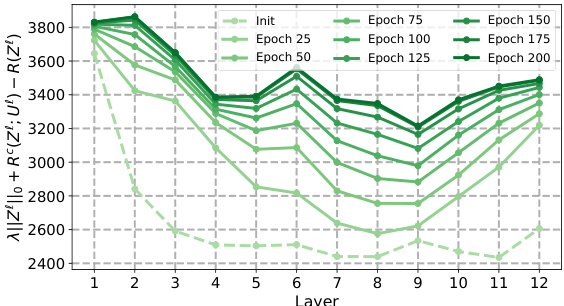

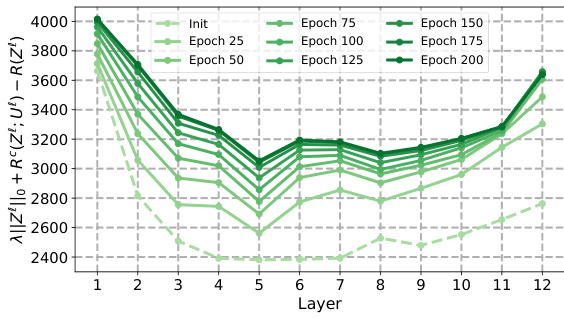

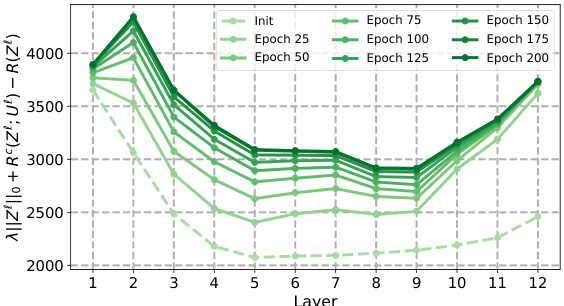

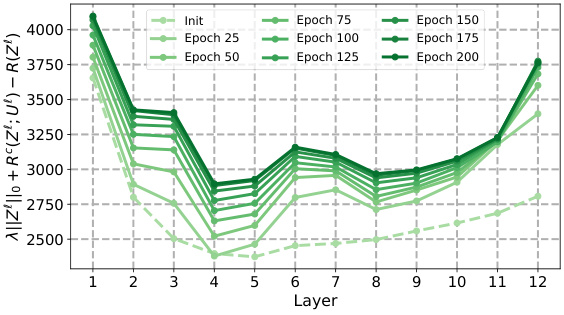

This figure shows the behavior of the sparse rate reduction measure across different layers and training epochs for four variants of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Each line represents a different epoch, illustrating how this complexity measure changes as the model trains and propagates through its layers. The figure highlights that the measure generally decreases in the initial layers and then increases in deeper layers, offering insights into the optimization process within the CRATE model.

This figure shows how the sparse rate reduction measure changes across different layers of the CRATE model and its variants (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T) during training on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the sparse rate reduction measure. Separate lines are shown for different training epochs, providing insight into how this measure evolves as the model trains. The figure aims to illustrate whether the sparse rate reduction objective is being optimized during the forward pass and how it changes throughout the training process.

This figure displays the evolution of the sparse rate reduction (SRR) measure across different layers and training epochs for four variants of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The SRR metric combines the L0 norm of the representations, the coding rate in subspaces, and the overall coding rate. The plots show how this measure changes as the model trains, indicating whether the model is successfully optimizing SRR during the forward pass. Each line represents a different epoch of training, showing how SRR changes across layers in the network over time. This visualization helps to understand the layer-wise behaviors of SRR optimization within the various CRATE models.

This figure shows the sparse rate reduction measure (||Z||o + Rº(Z;U) – R(Z)) for CRATE and its variants (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T) across different layers and epochs during training on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Each subplot represents a different variant of the CRATE model. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the sparse rate reduction measure. Different colored lines represent different epochs during training. The figure aims to illustrate how the sparse rate reduction measure evolves throughout the layers of the model and over the course of training, providing insights into the optimization process.

This figure shows how the sparse rate reduction (SRR) measure changes across different layers of four variations of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) at various training epochs (from initialization to epoch 200) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The SRR measure is a complexity metric reflecting the compactness of learned representations. The plot reveals the layer-wise behaviors of SRR optimization during training and highlights differences among the CRATE variants. The graph indicates a generally decreasing trend in SRR in the initial layers, suggesting effective compression, followed by an increase in later layers. This suggests an interplay between compression and sparsity which is not completely optimized in the CRATE model as originally proposed.

This figure shows the behavior of the sparse rate reduction measure across different layers and epochs for four variants of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the sparse rate reduction measure. Each line represents a different epoch during training, showing how this measure changes as the model learns. The figure helps visualize how the sparse rate reduction is optimized layer-wise during training for each variant and to understand differences among variants.

This figure visualizes how the sparse rate reduction measure changes across different layers of the CRATE model and its variants (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T) during training on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the sparse rate reduction measure. Each line corresponds to a different training epoch, showing the evolution of the measure over time. The figure helps in understanding the layer-wise optimization behavior of the SRR objective in various model implementations.

This figure shows the sparse rate reduction measure across different layers and epochs of four variants of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Each line represents a different epoch, showing how the measure evolves during training. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the sparse rate reduction measure.

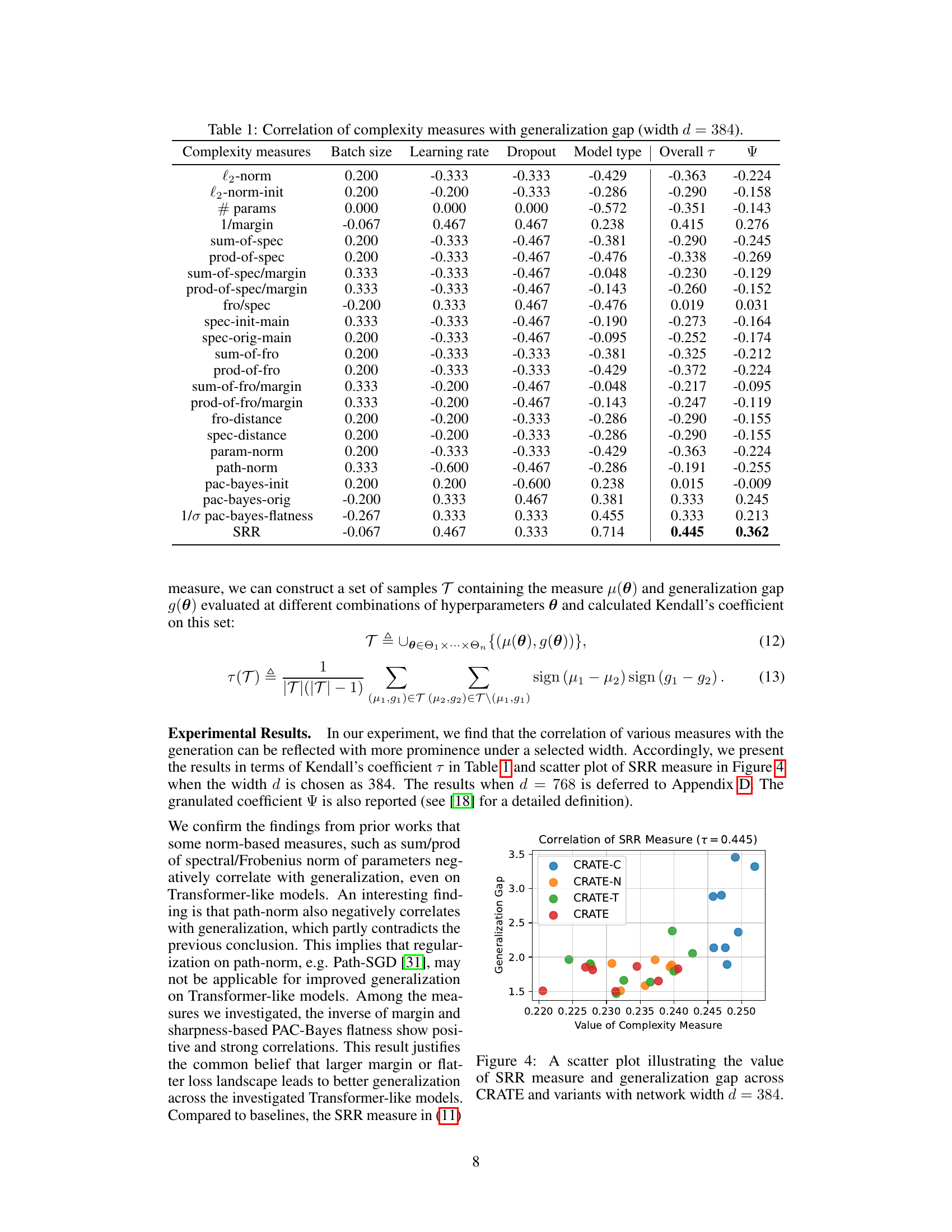

This figure shows a scatter plot that visualizes the relationship between the Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) measure and the generalization gap for various CRATE models with a network width of 384. Each point represents a different model variant, with the x-coordinate indicating the SRR measure and the y-coordinate representing the generalization gap. The plot aims to demonstrate the correlation between SRR and generalization performance. Different colors represent different CRATE variants (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, CRATE).

This figure shows the results of a simplified attention-only experiment. The left panel (a) demonstrates that, contrary to its intended purpose, the MSSA operator with skip connections actually performs an ascent on Rº(Z; U) rather than a descent. The right panel (b) illustrates why this occurs: it’s due to an artifact introduced by approximating the log(.) function using only its second-order Taylor expansion term. The graph shows that this approximation leads to maximization of Rº instead of minimization, illustrating the shortcomings of this simplification in the derivation of CRATE.

This figure shows the correlation between the Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) measure and the generalization gap for different variants of the CRATE model (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) with a network width of 768. Each point represents a model trained with different hyperparameters. The x-axis represents the SRR measure, which is used as a complexity measure, and the y-axis represents the generalization gap (the difference between validation loss and training loss). A positive correlation between SRR and generalization gap is observed, indicating that models with higher SRR values tend to have larger generalization gaps.

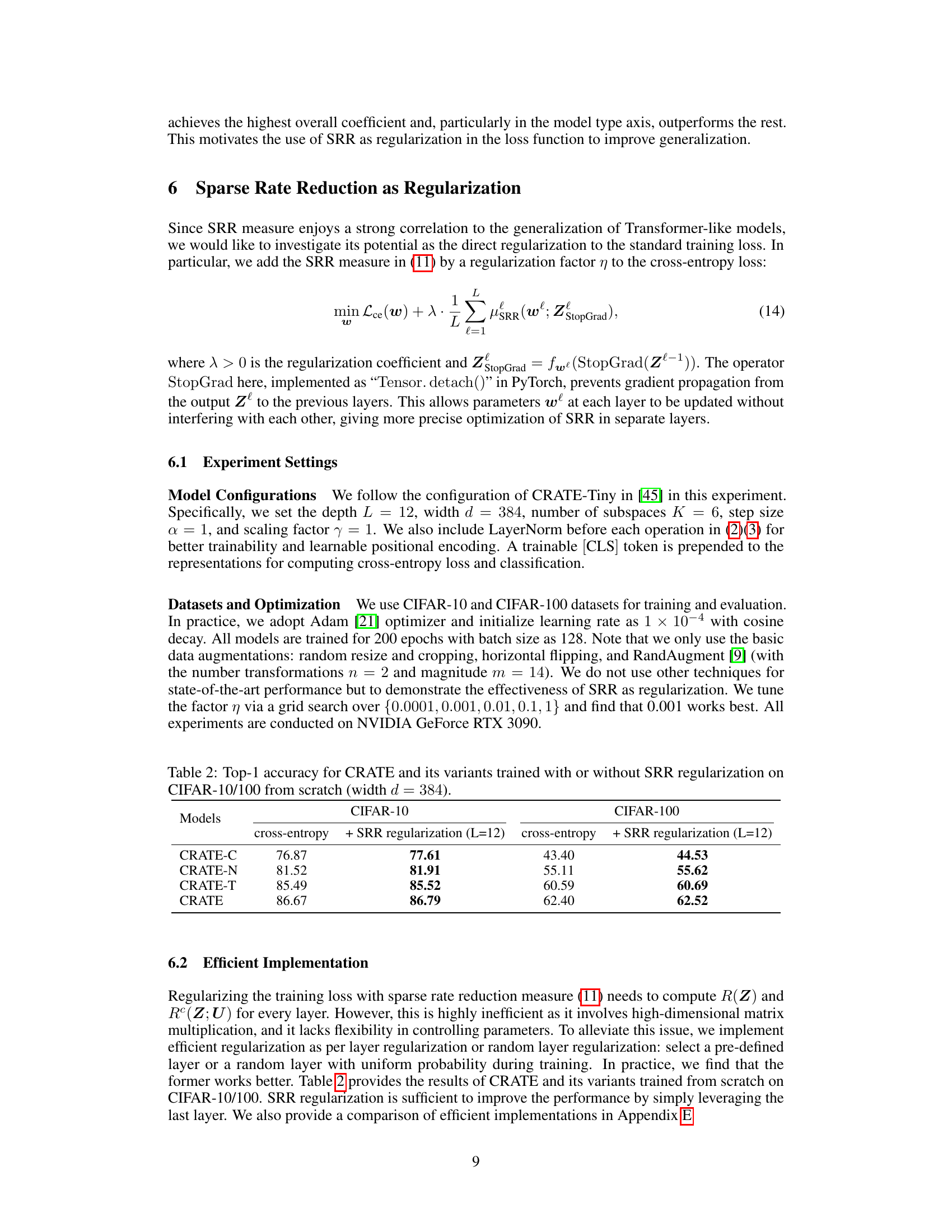

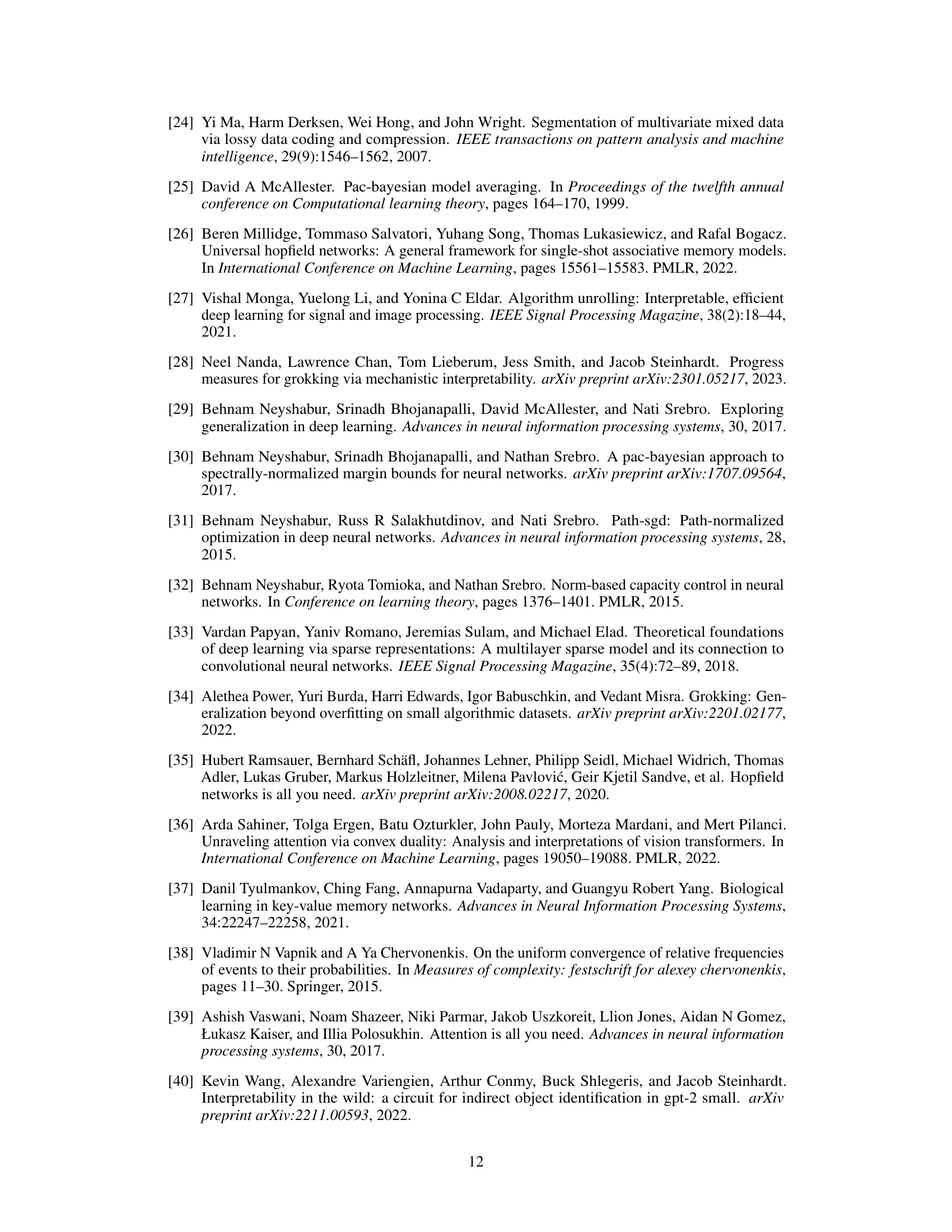

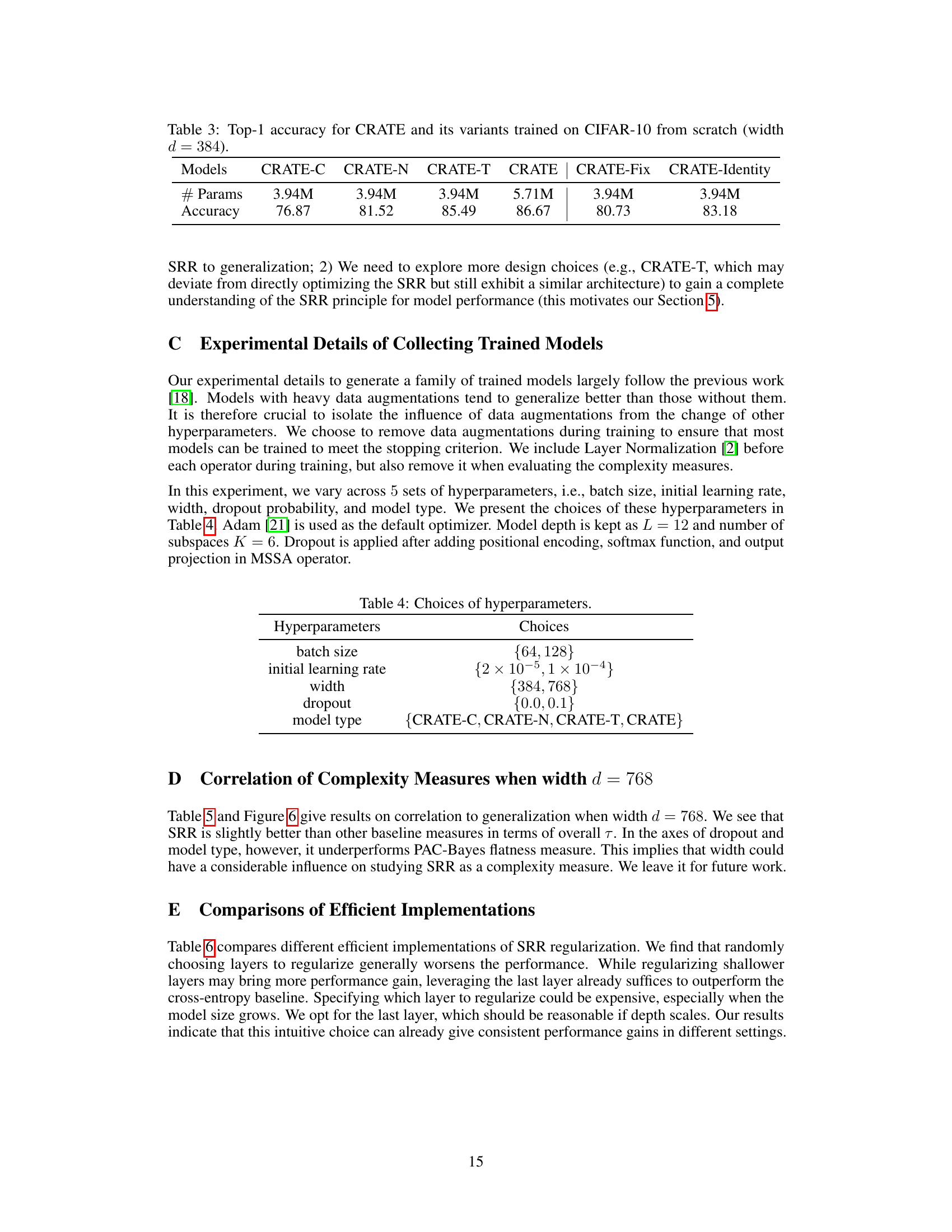

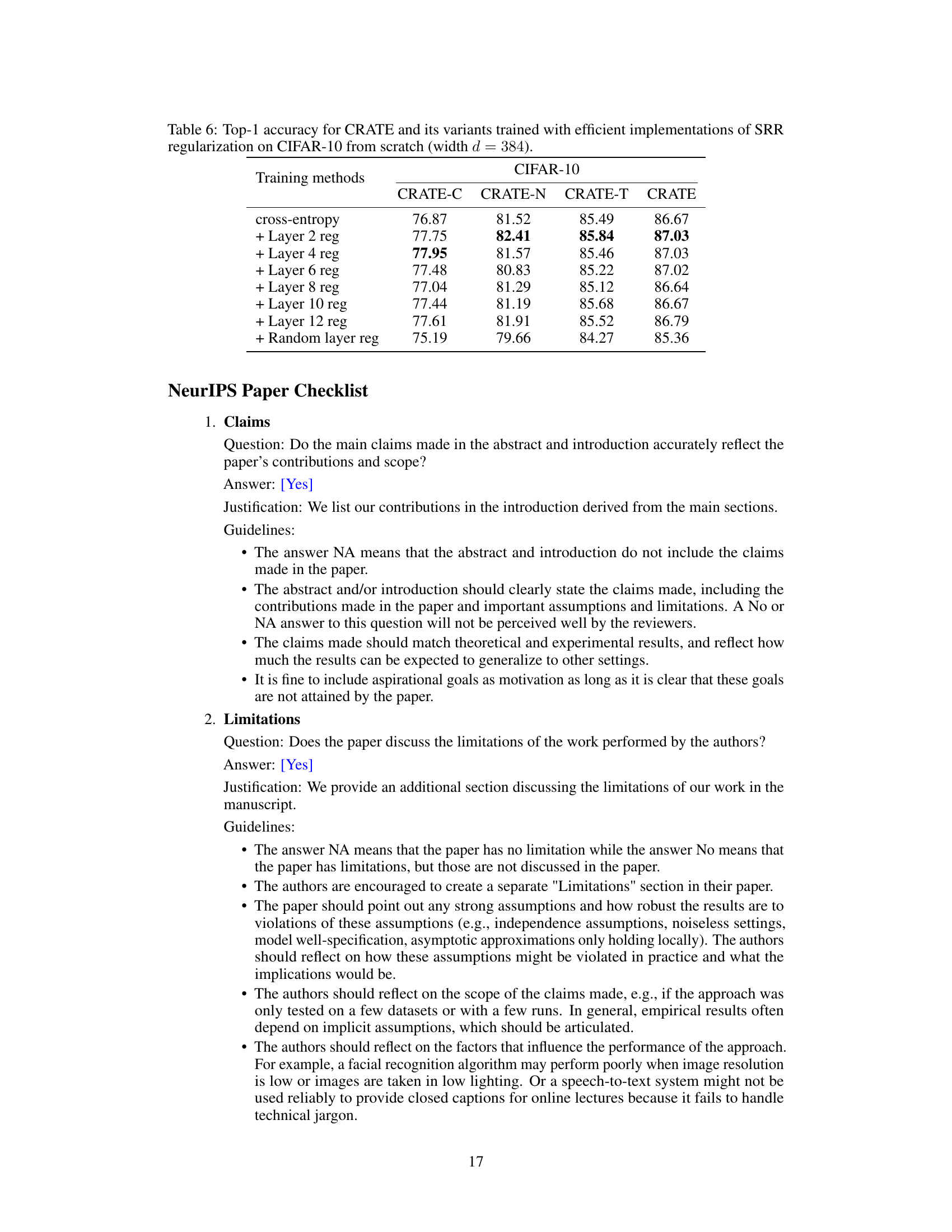

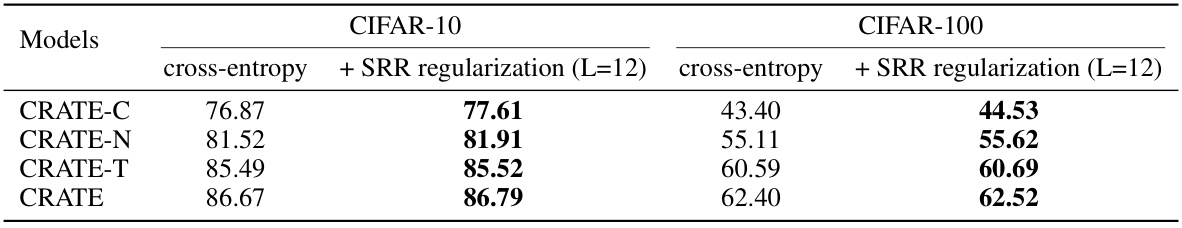

More on tables

This table shows the top-1 accuracy results achieved by four different Transformer-like models (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) when trained on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The models were trained using either only cross-entropy loss or cross-entropy loss combined with Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) regularization. The table highlights the impact of SRR regularization on model performance, demonstrating improvement in accuracy for all models across both datasets when SRR regularization was used.

This table presents the top-1 accuracy results achieved by different variants of the CRATE model on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The models were trained from scratch with a network width (d) of 384. The variants include the original CRATE-C, along with modifications CRATE-N (negative), CRATE-T (transpose), and CRATE (original with learnable parameters), CRATE-Fix (fixed output matrix), and CRATE-Identity (identity output matrix). The table also shows the number of parameters (# Params) for each model variant.

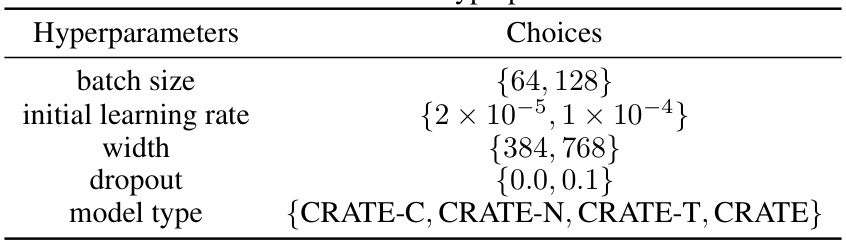

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the experiments and their respective choices. These hyperparameters were varied to generate a set of models for evaluating the correlation between SRR and generalization. The hyperparameters include batch size, initial learning rate, width (of the model), dropout rate, and model type (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE).

This table presents the Kendall’s rank correlation coefficients (τ) between different complexity measures and the generalization gap for a network width of 768. The table shows the correlation for each measure across various hyperparameter settings (batch size, learning rate, dropout, and model type), as well as an overall correlation. Positive values indicate a positive correlation (lower complexity associated with better generalization), and negative values indicate a negative correlation.

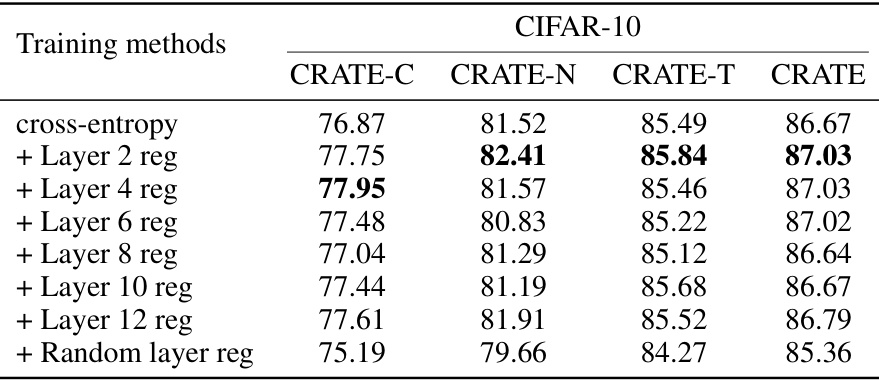

This table presents the top-1 accuracy results achieved by various CRATE models (CRATE-C, CRATE-N, CRATE-T, and CRATE) when trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset using different efficient implementations of Sparse Rate Reduction (SRR) regularization. The models were trained from scratch with a network width of 384. The table compares the performance of models trained solely with cross-entropy loss against those trained with cross-entropy loss plus SRR regularization applied to different layers (layer 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) or randomly selected layers. The results highlight the impact of applying SRR regularization at various layers and compare the effectiveness of different layer selection strategies for regularization.

Full paper#