↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications of reinforcement learning involve noisy or partially observable environments which create challenges when using formal languages like Reward Machines to specify instructions or objectives. Existing deep RL approaches often rely on perfect knowledge of the domain’s symbolic vocabulary—an assumption which is unrealistic. This research addresses this critical gap by creating a framework that enables the use of Reward Machines in these noisy and uncertain settings.

The paper proposes a deep RL framework for handling noisy Reward Machines by modelling the problem as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP). This framework allows the use of abstraction models, which are essentially imperfect estimators of task-relevant features. The authors also propose and analyze a suite of RL algorithms that can exploit Reward Machine structure without perfect knowledge of the vocabulary. They showcase how pre-existing abstraction models (e.g., sensors, heuristics, pre-trained neural networks) can improve learning. The framework’s effectiveness is demonstrated theoretically and experimentally, highlighting pitfalls of naive approaches and demonstrating successful leveraging of task structure under noisy interpretations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep reinforcement learning (RL) and artificial intelligence (AI) because it tackles a critical issue: applying formal languages like Reward Machines in real-world scenarios where noisy and uncertain observations are prevalent. The proposed framework offers a novel way to leverage task structure in deep RL, leading to improved sample efficiency and robustness. This is highly relevant to current research trends in AI safety, robust RL, and generalizing RL agents to complex environments.

Visual Insights#

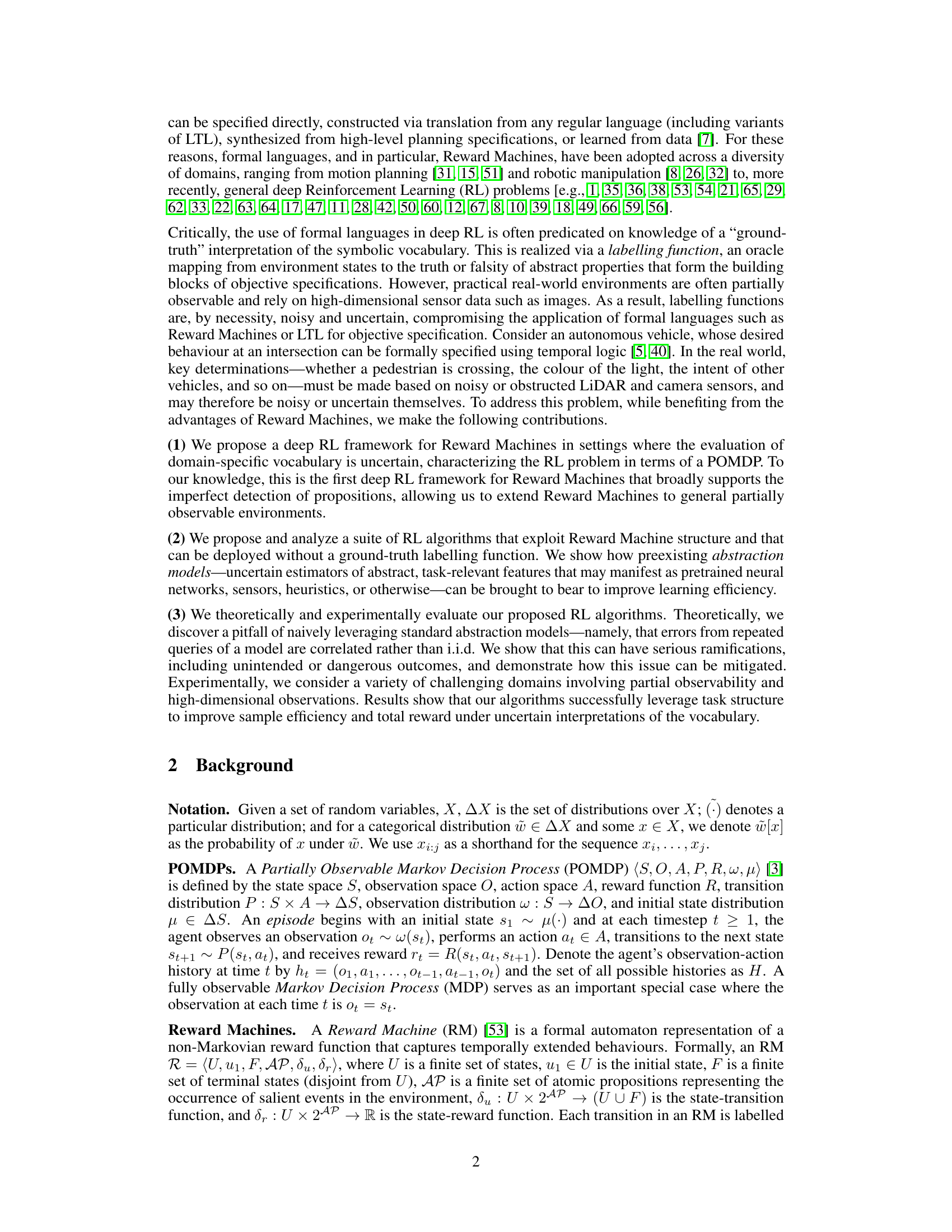

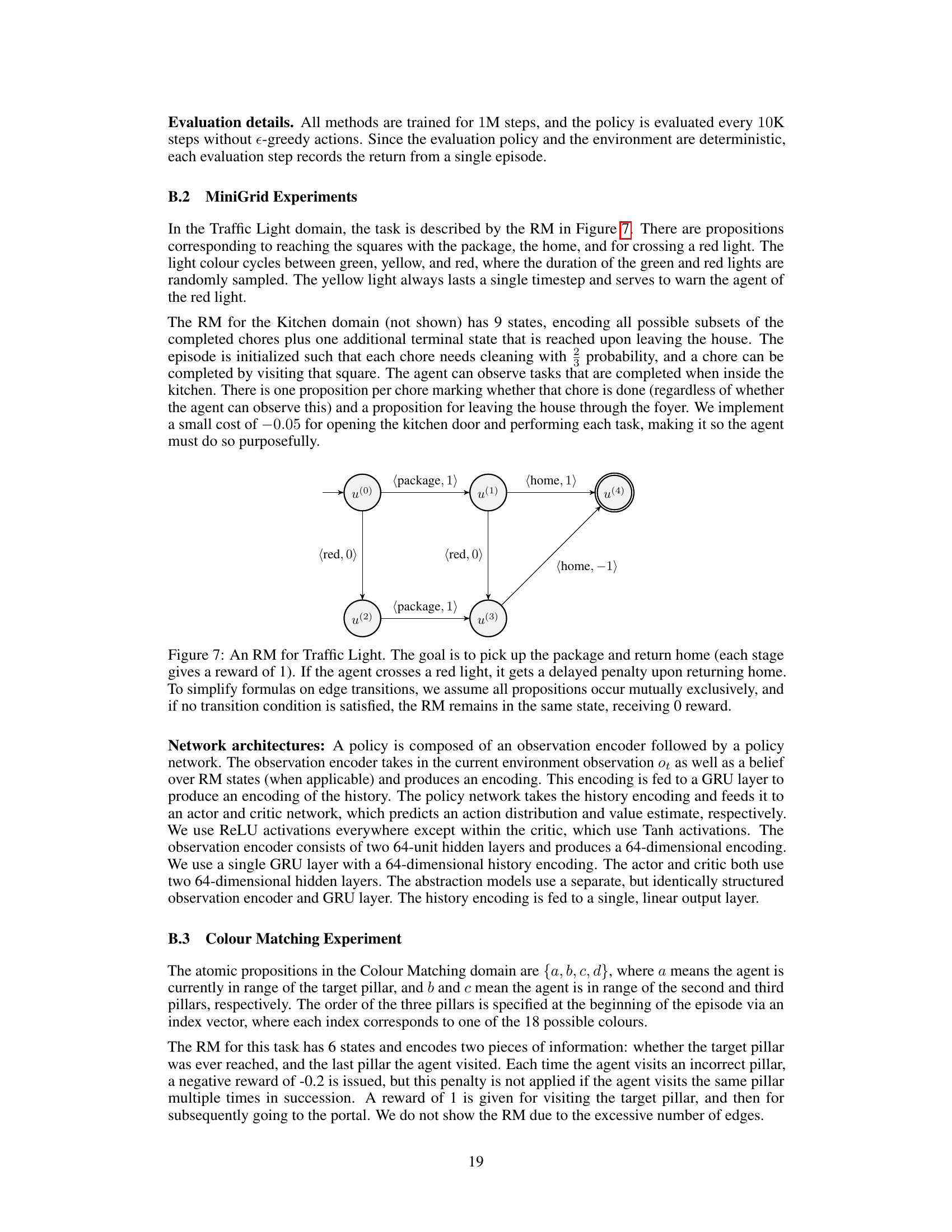

This figure illustrates the architecture of a noisy reward machine environment. The agent interacts with the environment, receiving observations and taking actions. Crucially, the agent does not have direct access to the ground-truth labelling function (which maps environment states to propositions used by the reward machine). Instead, it relies on an abstraction model, which provides noisy or uncertain interpretations of the relevant propositions. The dashed lines indicate components only used during training, not during deployment.

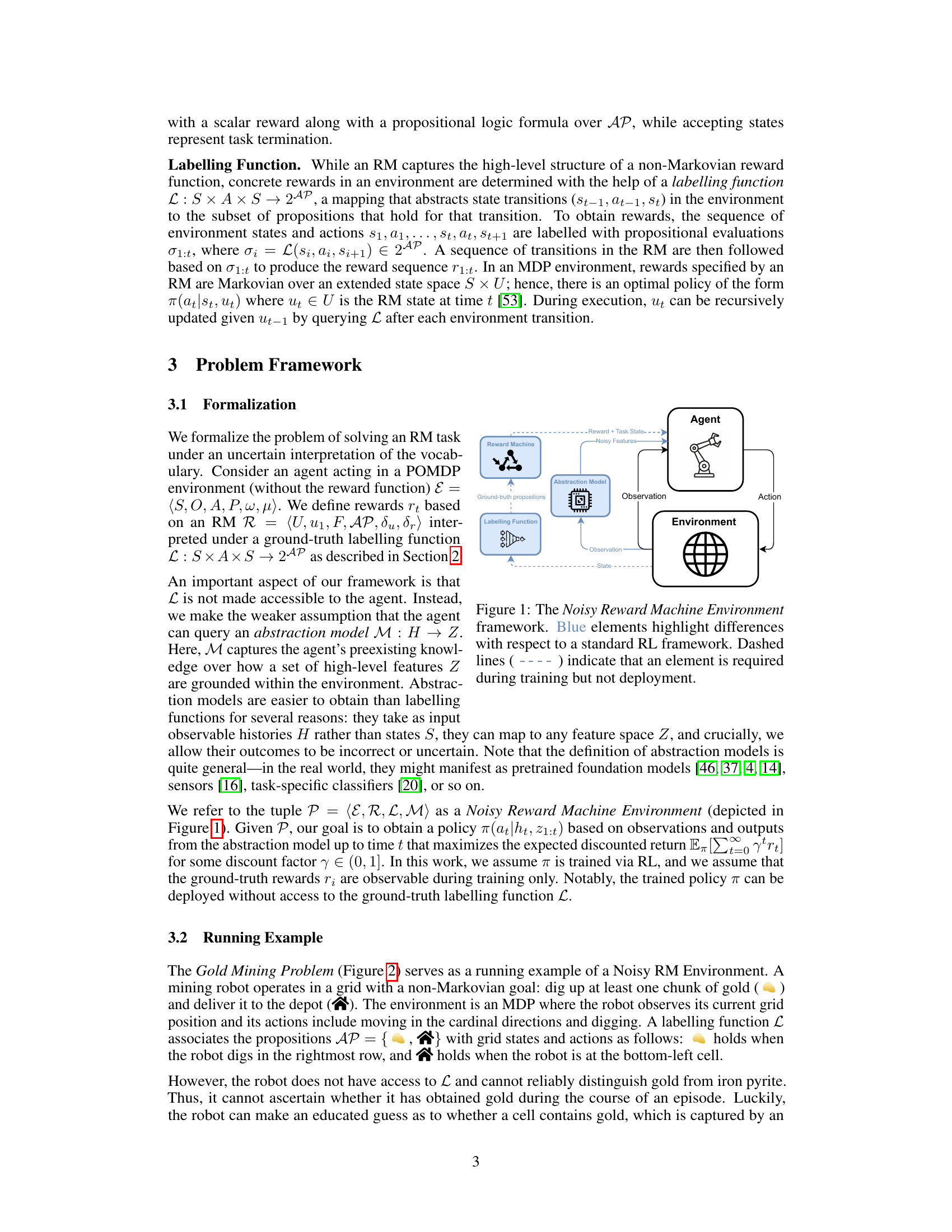

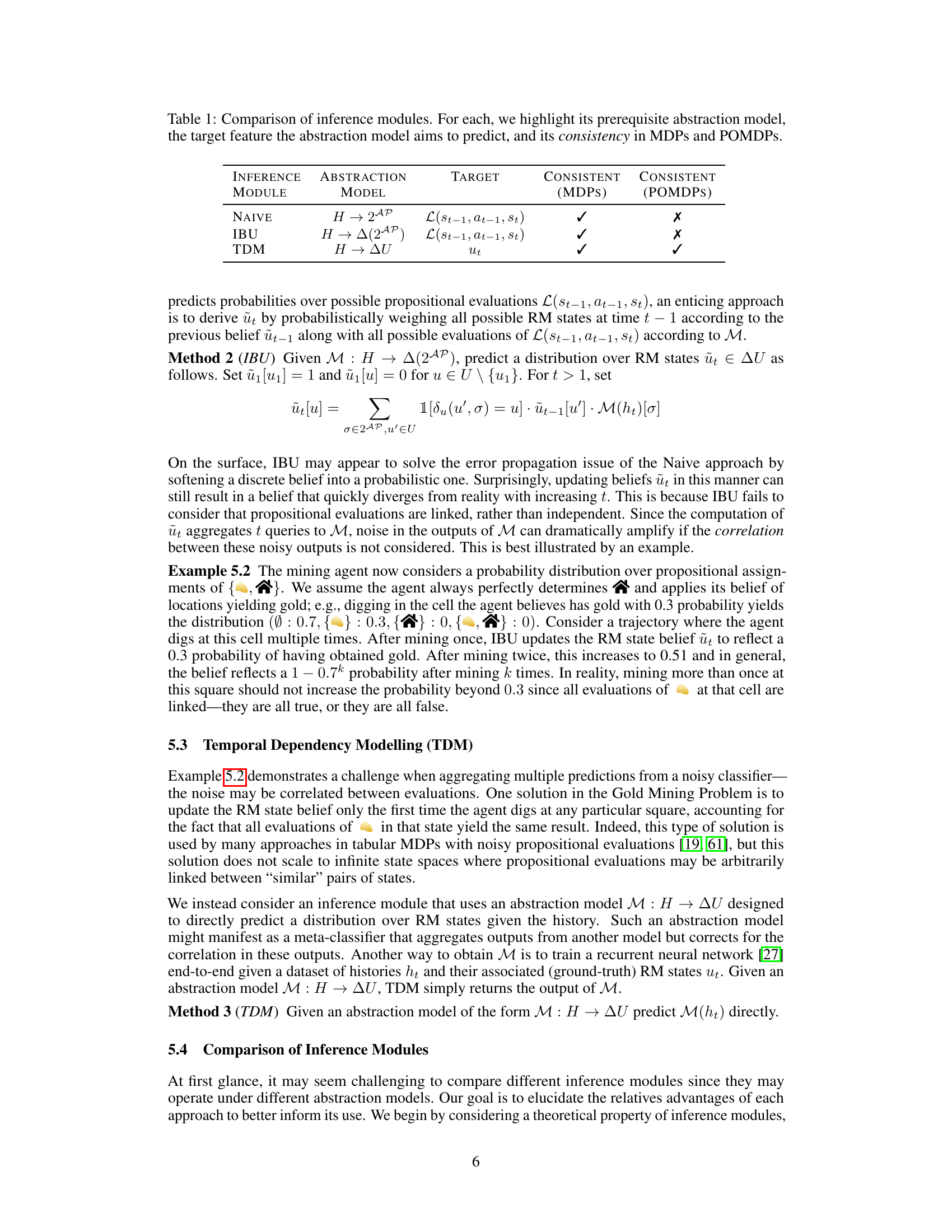

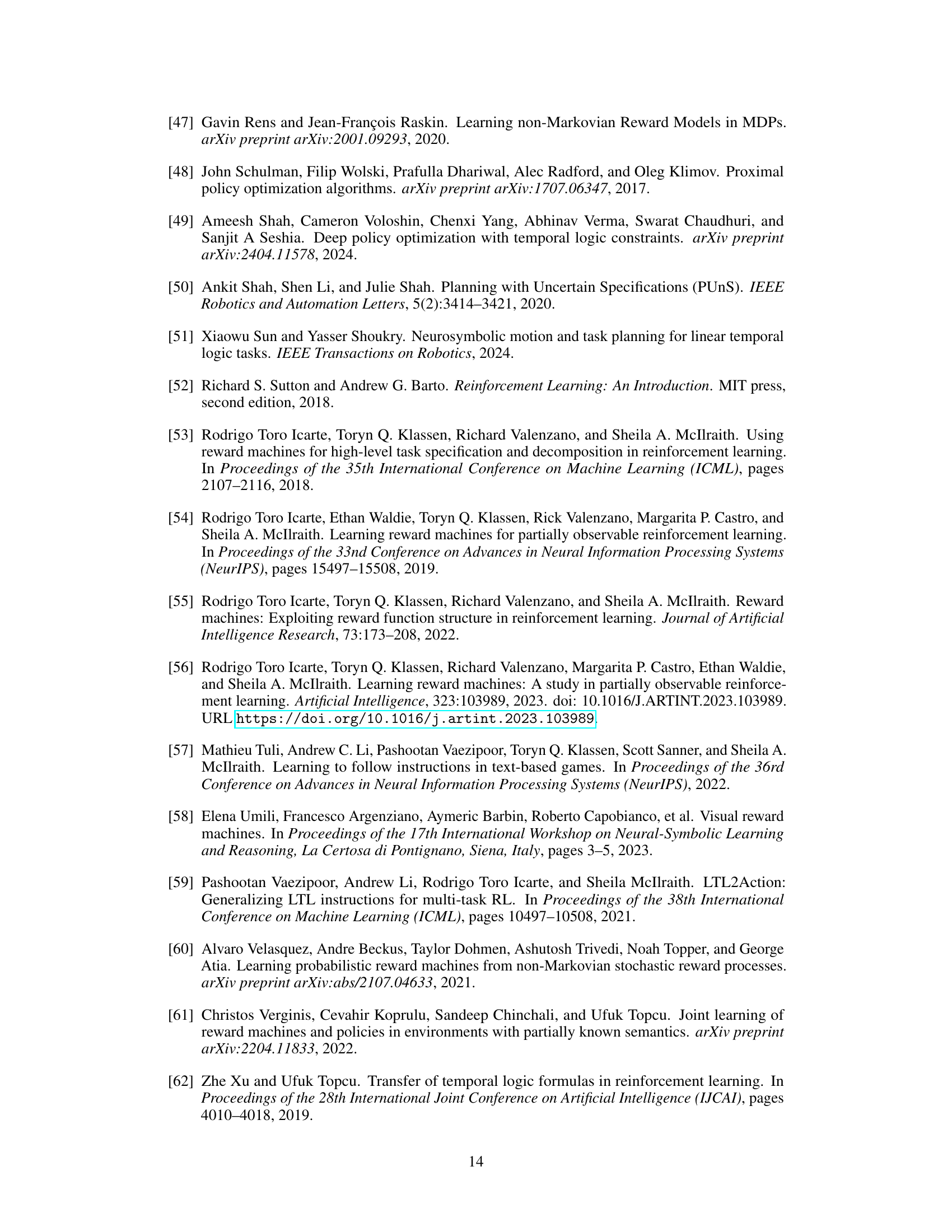

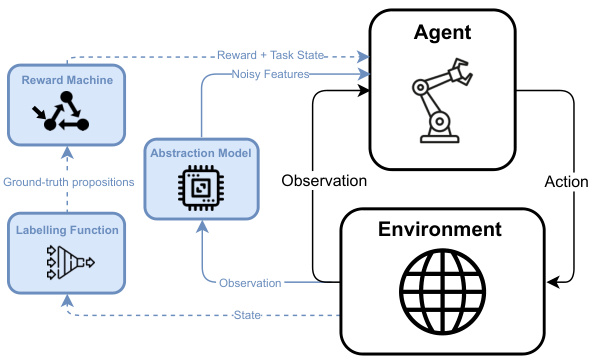

The table compares three different inference modules (Naive, IBU, TDM) used in the paper’s proposed deep RL framework for reward machines in noisy environments. For each module, it specifies the type of abstraction model required, the target feature the abstraction model is trying to predict (either the ground truth labelling function or the RM state), and whether the module is consistent for both fully observable Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) and Partially Observable MDPs (POMDPs). Consistency here refers to whether the module can perfectly recover the target feature given an ideal abstraction model.

In-depth insights#

Noisy Reward Machines#

The concept of “Noisy Reward Machines” introduces a crucial layer of realism to reinforcement learning. Traditional reward machines assume precise, consistent feedback, but real-world applications are rife with noise and uncertainty in observations and reward signals. A noisy reward machine acknowledges this inherent uncertainty, modeling the ambiguity in interpreting the environment’s state and the resulting rewards. This leads to significant challenges in learning effective policies, as agents must grapple with incomplete or unreliable information. Robust algorithms are needed to handle noisy interpretations of domain-specific vocabulary, whether from imperfect sensors or noisy labelling functions. The research explores how to leverage task structure despite this noise, using abstraction models to potentially improve sample efficiency. The exploration of this area highlights the need for deep RL algorithms to be robust and adaptable to real-world complexities, pushing the boundaries of current theoretical frameworks and demanding novel solution strategies.

POMDP Deep RL#

POMDP Deep RL combines the framework of Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs) with the power of deep reinforcement learning (Deep RL). POMDPs address the challenge of partial observability, where the agent doesn’t have complete information about the environment’s state. Deep RL, with its capacity for handling high-dimensional inputs and complex state spaces, offers a powerful solution. By framing the RL problem as a POMDP, the approach explicitly accounts for uncertainty in observation, enabling more robust and effective learning. Deep RL algorithms can then learn policies that optimally navigate the uncertainty, maximizing rewards despite incomplete information. This combination is particularly valuable in complex real-world scenarios such as robotics, autonomous driving, and healthcare, where perfect state observation is often infeasible.

Abstraction Models#

The concept of ‘Abstraction Models’ in the context of reinforcement learning with reward machines is crucial for handling noisy and uncertain environments. These models act as intermediaries, bridging the gap between raw sensory inputs and the abstract propositions used within the reward machine framework. Instead of relying on a perfect ‘ground truth’ labelling function, which is often unrealistic in real-world scenarios, abstraction models provide noisy estimates of these propositions. The choice of abstraction model significantly influences the performance of the resulting RL algorithms; a poorly designed model might amplify uncertainty, leading to suboptimal or even dangerous behavior. The paper explores various methods for utilizing these models, each handling uncertainty differently and facing unique challenges. Key considerations involve how to effectively incorporate the noisy outputs from the abstraction model into the decision-making process while accounting for potential correlations in prediction errors. This involves a trade-off between utilizing the task structure inherent in the reward machine and robustness to the imperfections of the abstraction model. The effectiveness of different approaches, such as naive prediction, independent belief updating (IBU), and temporal dependency modeling (TDM), is theoretically and empirically compared.

RM Inference Methods#

The core challenge addressed in the paper is how to effectively infer the hidden state of a Reward Machine (RM) within noisy and uncertain environments, where the ground truth interpretation of domain-specific vocabulary is unavailable. This necessitates the development of robust RM inference methods that can handle imperfect observations and noisy estimates of abstract propositions. The paper introduces three such methods: Naive, Independent Belief Updating (IBU), and Temporal Dependency Modeling (TDM). Naive is simple but suffers from error propagation; IBU addresses this by incorporating probabilistic belief updates but still struggles with correlations in noise. In contrast, TDM directly models the RM state distribution, proving more resilient and accurate by explicitly accounting for the temporal dependencies in noisy observations. The experimental results highlight the strengths and weaknesses of these methods, demonstrating that TDM offers significant advantages in terms of sample efficiency and accuracy, especially when dealing with complex, real-world scenarios.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on reward machines in noisy environments could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness and efficiency of the proposed TDM approach is crucial. This could involve investigating more sophisticated abstraction models, perhaps leveraging techniques from Bayesian inference or deep learning to better handle noisy or incomplete observations. Developing methods to automatically learn the structure of the reward machine from data would significantly improve scalability and applicability. Further investigation into the interplay between abstraction model uncertainty and policy learning is needed. Theoretically analyzing the effects of correlated errors in abstraction model queries would provide strong foundations for designing better RL algorithms. Finally, applying these techniques to more complex, real-world applications, such as robotics and autonomous driving, is vital. Addressing the challenges posed by high-dimensional sensory data and long temporal horizons in real-world scenarios would help demonstrate the practical potential of this research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

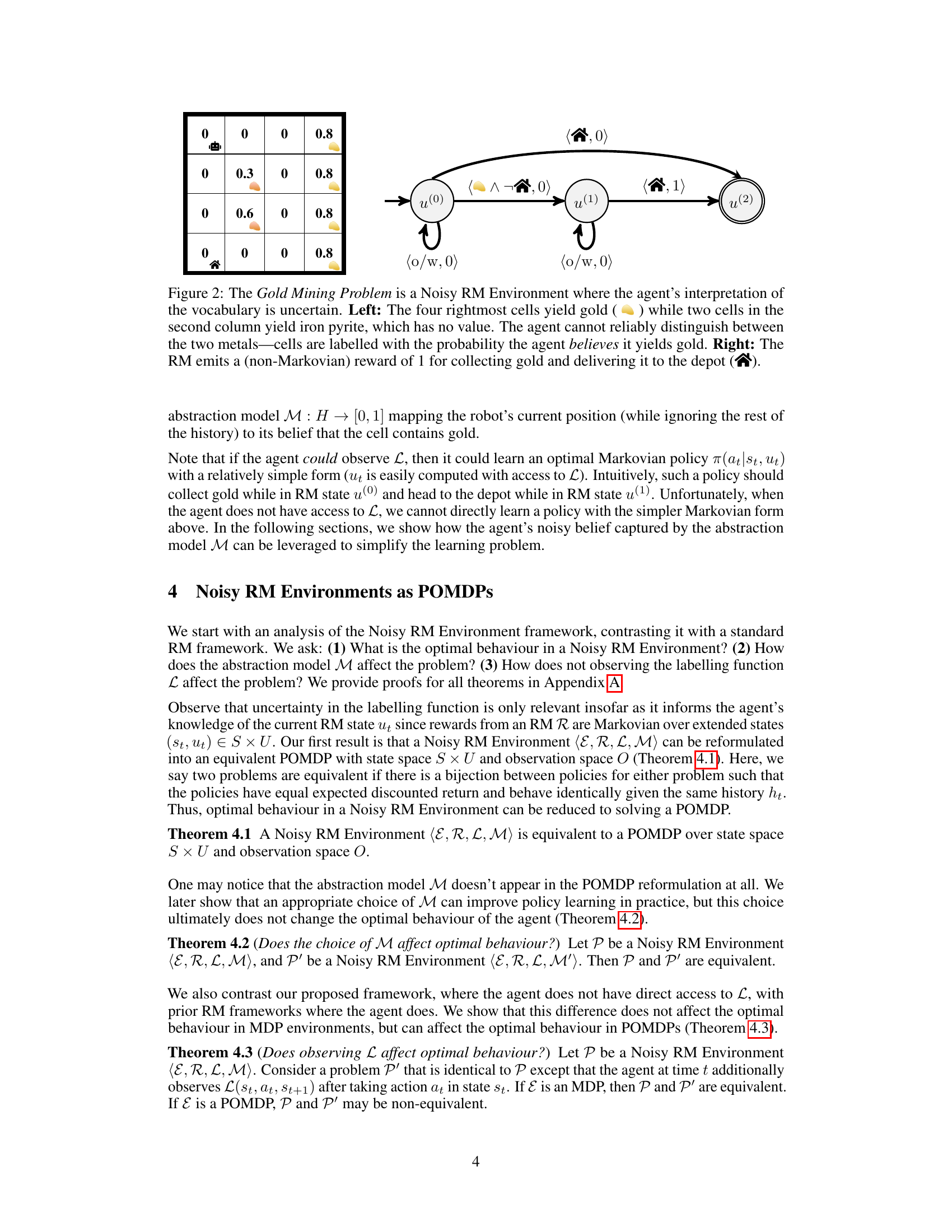

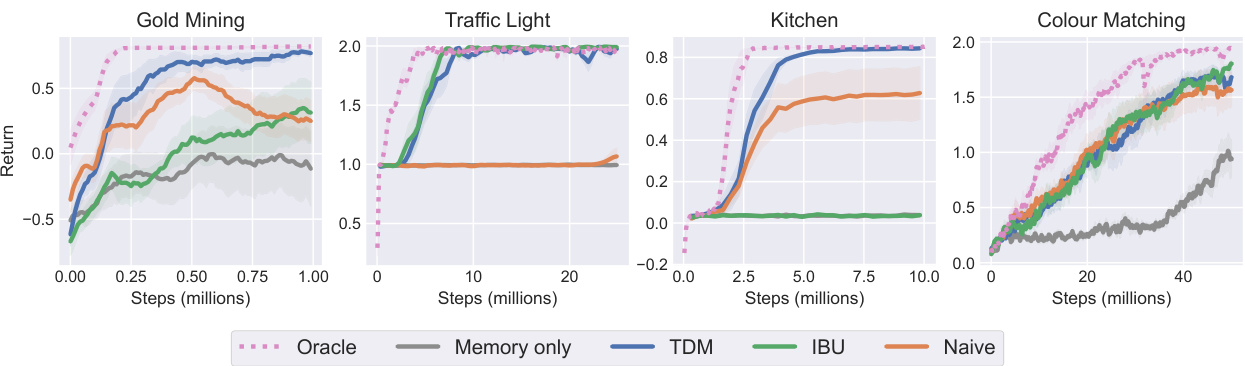

This figure illustrates the Gold Mining Problem, used as a running example in the paper. The left panel shows a grid world where the agent (robot) must collect gold. The numbers in each cell represent the probability that the cell contains gold (the agent cannot distinguish with certainty between gold and iron pyrite). The goal is to collect at least one gold and deliver it to the depot (bottom left). The right panel shows the Reward Machine (RM), a finite state automaton that defines the reward structure for this task. The RM transitions depend on whether the robot digs gold and delivers it to the depot, demonstrating a temporally extended reward.

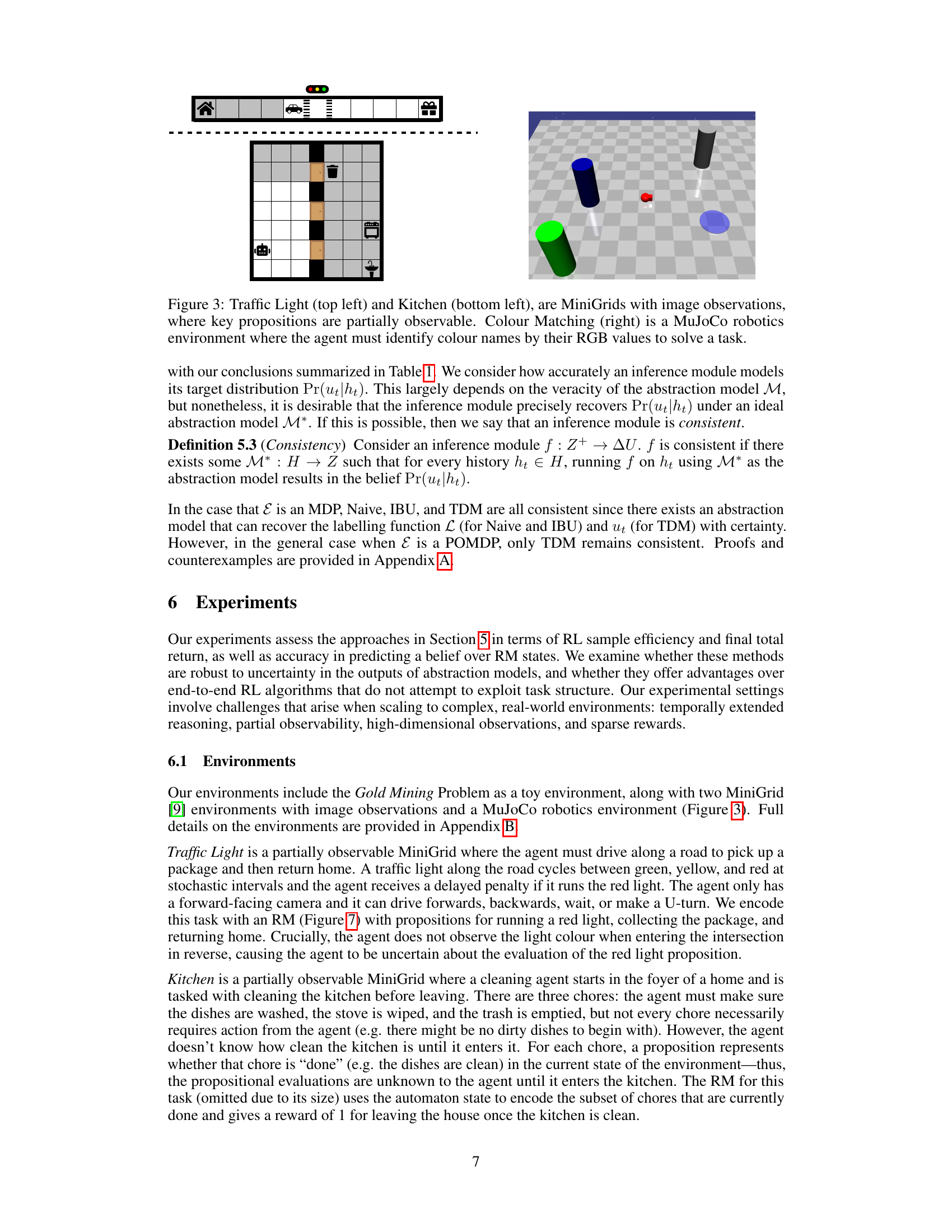

This figure shows three different reinforcement learning environments used in the paper’s experiments. The ‘Traffic Light’ and ‘Kitchen’ environments are from the MiniGrid suite and use image-based partial observability; agents must infer key features (e.g., traffic light color, kitchen cleanliness) from noisy observations. The ‘Colour Matching’ environment, on the other hand, is a MuJoCo robotics task requiring the agent to associate colors with RGB values. These diverse environments test the robustness and efficiency of the proposed algorithms in various settings.

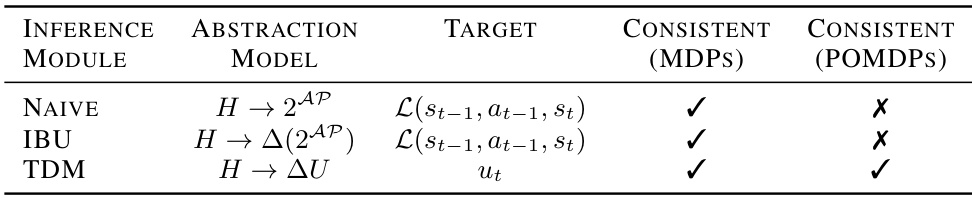

This figure shows the results of reinforcement learning experiments comparing different methods in four environments: Gold Mining, Traffic Light, Kitchen, and Colour Matching. The x-axis represents training steps in millions, and the y-axis shows the average return achieved by different RL algorithms. The algorithms compared include an oracle (with access to the true labeling function), a memory-only recurrent PPO approach, and three proposed methods: TDM, IBU, and Naive. The shaded areas represent the standard error of the mean across eight runs. The key finding is that the TDM method consistently performs well, even without access to the ground-truth labels, significantly outperforming the memory-only method.

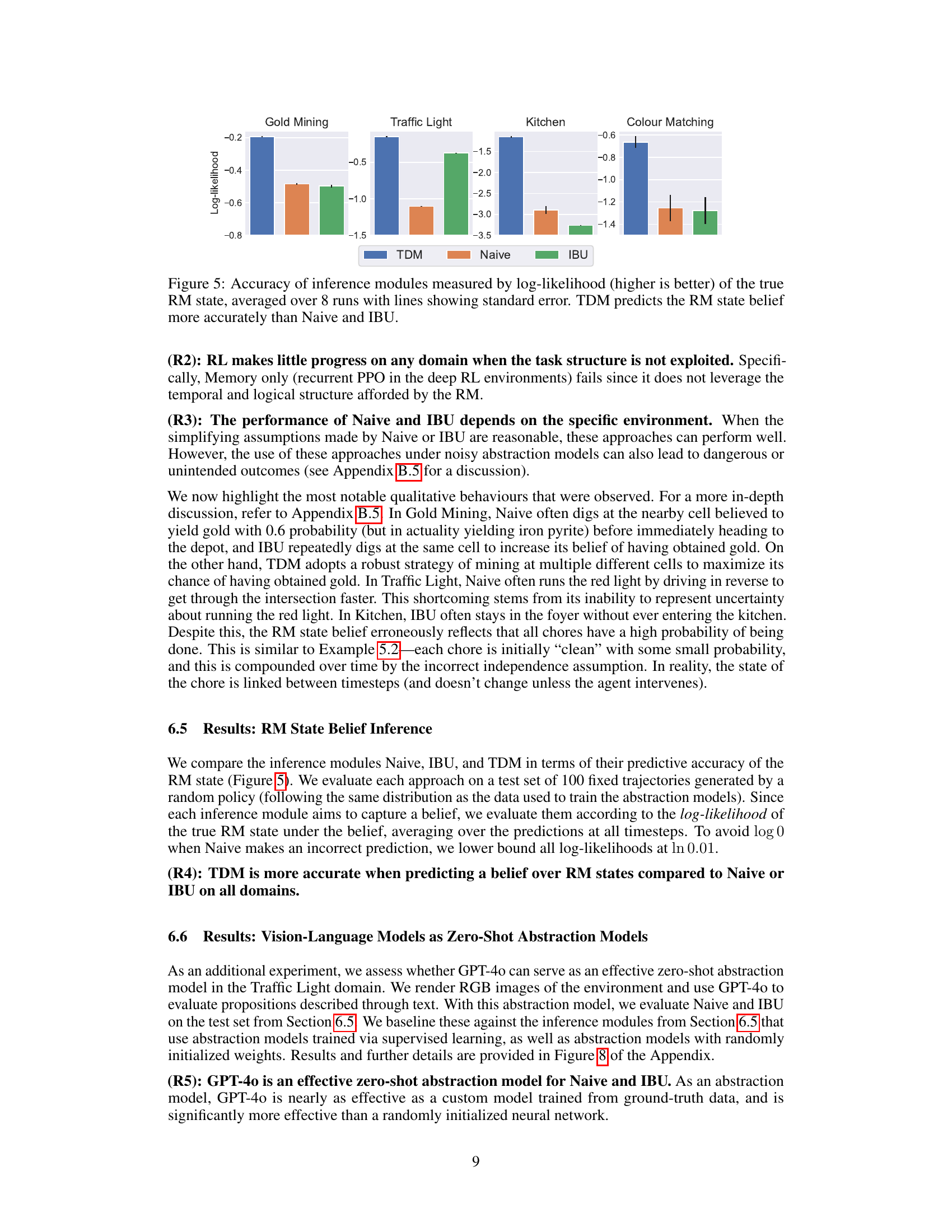

This figure compares the accuracy of three different inference modules (TDM, Naive, and IBU) in predicting the belief over Reward Machine states. The accuracy is measured using log-likelihood, with higher values indicating better accuracy. The results are averaged over 8 runs, and error bars represent the standard error. The figure shows that TDM significantly outperforms Naive and IBU in accurately predicting the RM state belief across all four experimental environments.

This figure shows the precision and recall for a classifier trained to predict the occurrence of key propositions in three different environments: Traffic Light, Kitchen, and Colour Matching. The results are averaged over eight training runs, and error bars represent the standard error. The fact that some key propositions show low precision and recall highlights the inherent uncertainty in observing these propositions in real-world environments.

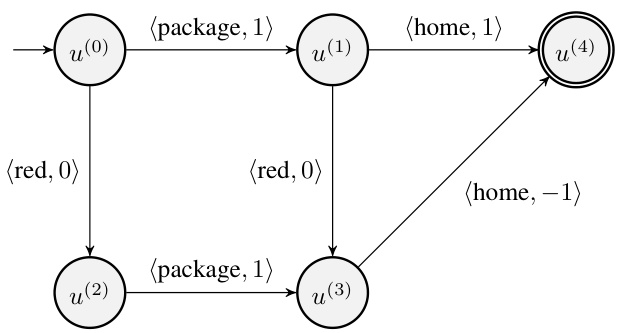

This figure shows a Reward Machine (RM) for the Traffic Light environment. The RM has four states, representing different stages of the task: initial state, reaching the package, reaching home, and a terminal state. Transitions between states are triggered by the propositions (red light, package, home). Rewards are associated with each transition. The agent receives a reward of 1 for picking up the package and arriving home and a penalty for running a red light.

This figure compares the accuracy of different inference modules (TDM, Naive, IBU) in predicting the Reward Machine (RM) state. It uses three types of abstraction models: one trained via supervised learning (SL), one using zero-shot GPT-40, and one with randomly initialized weights. The left panel shows the log-likelihood of the true RM state under the predicted belief, demonstrating TDM’s superior accuracy. The right panel shows a screenshot of the Traffic Light environment used for prompting GPT-40, illustrating the partial observability challenge.

More on tables

This table presents the hyperparameter settings used in the deep reinforcement learning experiments for three different environments: Traffic Light, Kitchen, and Colour Matching. It shows the parameters for both the main PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) algorithm and the abstraction model training process. The PPO parameters control aspects of the reinforcement learning process, such as the learning rate, discount factor, and entropy coefficient, while the abstraction model hyperparameters govern the training of the models used to estimate the truth values of propositions within the environments.

This table compares three different inference modules (Naive, IBU, TDM) used in the paper’s proposed deep RL framework for reward machines in uncertain environments. For each module, it specifies the type of abstraction model required as input (mapping from history to propositional evaluations or belief over RM states), the target feature that the abstraction model is intended to predict (ground truth propositional evaluations or RM state), and whether the inference method is theoretically consistent (meaning it can perfectly recover the true belief over the RM state) in both fully observable (MDP) and partially observable (POMDP) environments. This helps to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each approach for handling uncertainty in the interpretation of domain-specific vocabulary within reward machines.

Full paper#