↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent (DP-SGD) is a popular algorithm for training machine learning models while ensuring differential privacy. However, accurately assessing the real-world privacy guarantees of DP-SGD, especially in black-box scenarios where only the final model is accessible, has remained a challenge. Existing auditing methods often produce loose estimates, leaving a gap between theoretical and empirical privacy. This is particularly problematic given that bugs and violations are commonly found in DP-SGD implementations.

This research introduces a novel auditing procedure to address these issues. By crafting worst-case initial model parameters (a factor previously ignored by prior privacy analysis), the method achieves substantially tighter black-box audits of DP-SGD. Experiments conducted on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets show significantly smaller discrepancies between theoretical and empirical privacy leakage compared to previous approaches. The study also identifies factors such as dataset size and gradient clipping norm as influential elements affecting the tightness of the audits. Overall, the findings contribute towards building more robust and reliable differentially private systems by enhancing the accuracy of privacy analysis and enabling more precise detection of DP violations in implementations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with differentially private machine learning. It offers a novel auditing procedure that significantly improves the accuracy of privacy analysis, especially in black-box settings. This work is relevant because it addresses a critical gap in understanding the real-world privacy implications of widely used DP algorithms like DP-SGD. It directly contributes to building more reliable and trustworthy differentially private systems, and opens up avenues for further research into more precise privacy accounting techniques.

Visual Insights#

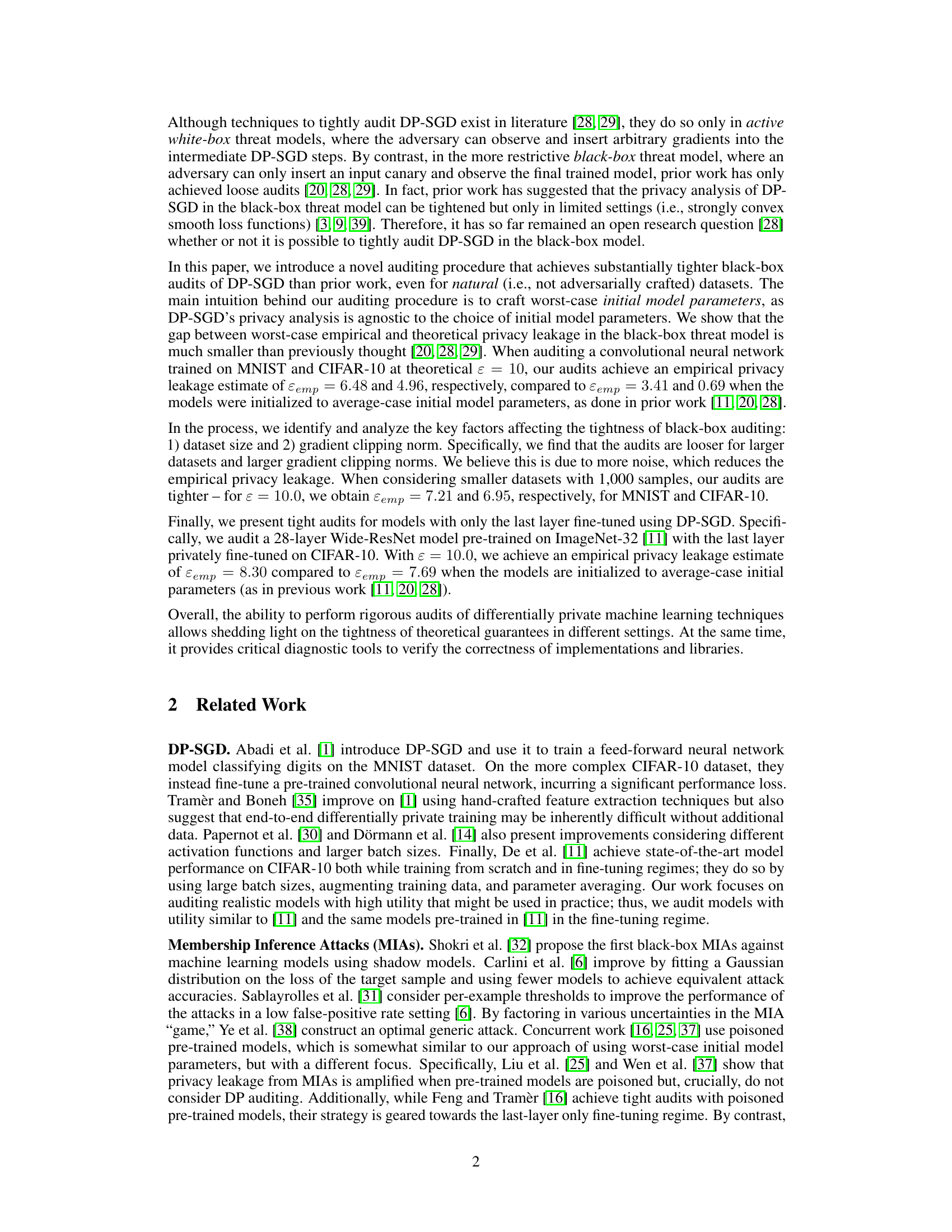

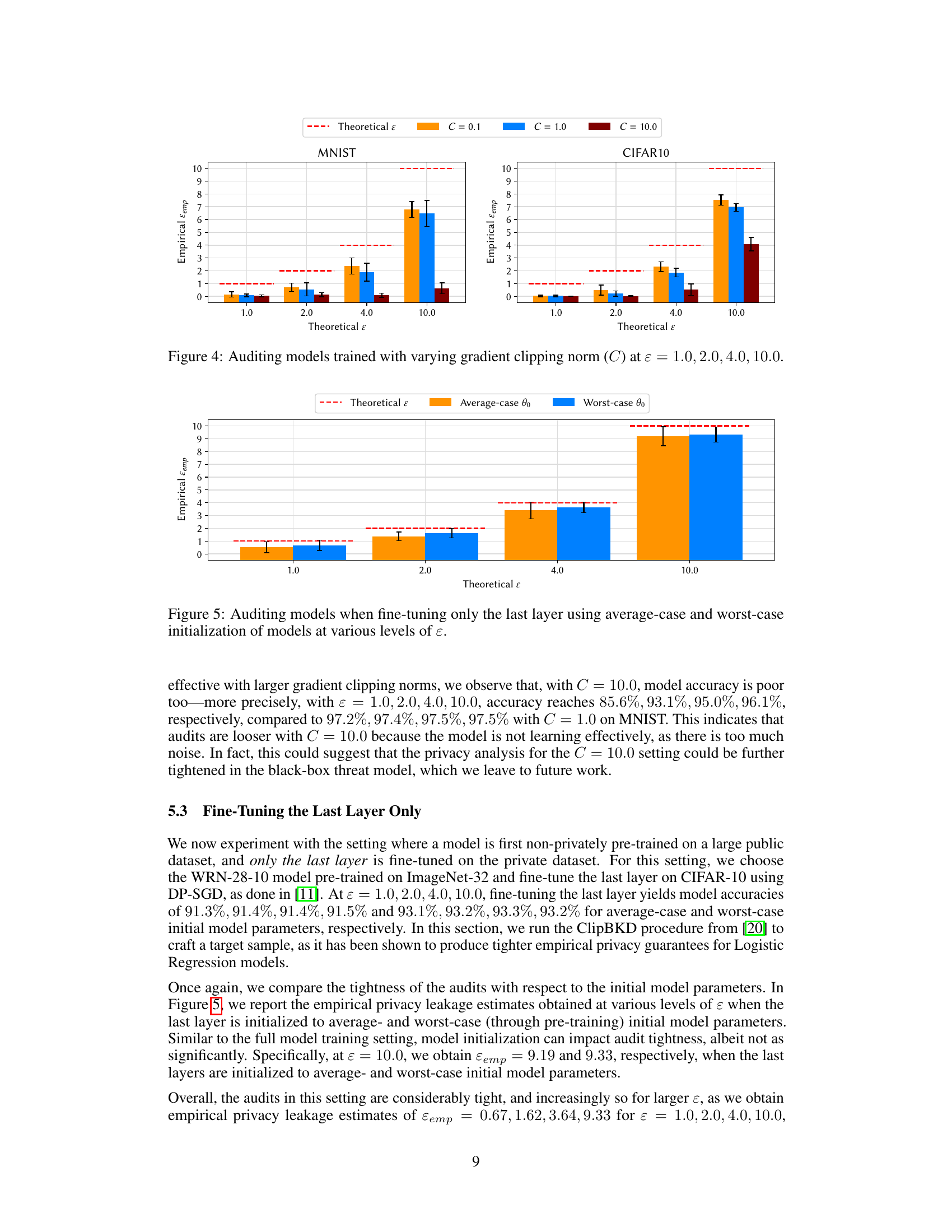

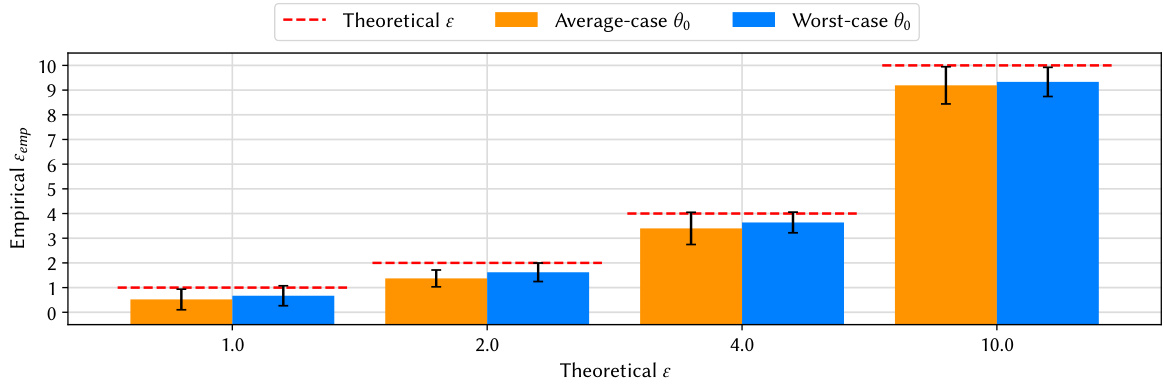

This figure compares the empirical privacy leakage (ε_emp) obtained using average-case and worst-case initial model parameters for MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets at different theoretical privacy levels (ε). The worst-case parameters, crafted to maximize privacy leakage, result in significantly higher ε_emp values, demonstrating the impact of parameter initialization on the tightness of black-box DP-SGD audits. Error bars represent the standard deviation across multiple runs of the audit procedure.

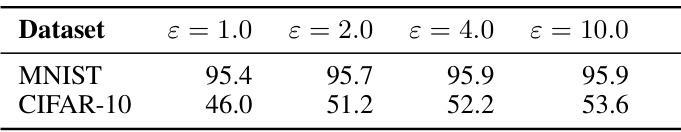

This table presents the accuracy achieved by models trained using DP-SGD with average-case initial model parameters. The accuracy is shown for different values of epsilon (ε), representing the privacy level, for both the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. Higher accuracy values indicate better model performance, while higher epsilon values represent a weaker privacy guarantee. The data in this table is used for comparison with results obtained using worst-case initial parameters.

In-depth insights#

DP-SGD Auditing#

DP-SGD auditing is crucial for verifying the privacy guarantees of differentially private machine learning models. Existing methods often fall short, providing loose empirical privacy estimates, particularly in the challenging black-box setting. This paper tackles the limitations of prior DP-SGD audits by focusing on crafting worst-case initial model parameters. This approach is particularly effective because the privacy analysis of DP-SGD is agnostic to the initial parameter choice. By identifying and exploiting this weakness, the authors achieve significantly tighter audits, bridging the gap between theoretical and empirical privacy leakage. They also explore the impact of dataset size and gradient clipping norm, highlighting the trade-off between audit tightness and practical considerations. The work’s strength lies in its rigorous methodology and realistic threat model, pushing the boundaries of black-box DP-SGD auditing and offering valuable insights into improving both privacy analysis and implementation of DP-SGD.

Worst-Case Priors#

The concept of “Worst-Case Priors” in the context of differentially private machine learning (DP-ML) focuses on selecting initial model parameters that maximize the adversary’s ability to infer sensitive information. Standard DP-SGD analysis is agnostic to the choice of initial parameters, making this a critical vulnerability. By strategically choosing these priors, a tighter bound on the actual privacy leakage can be achieved, providing a more realistic estimate than average-case initializations. This approach assumes a black-box auditing setting, where the adversary only has access to the final model output and not the intermediate training steps. The effectiveness of this strategy highlights that privacy leakage is not uniformly distributed across various parameter initializations. Choosing worst-case priors helps uncover potential flaws and vulnerabilities in DP-ML implementations. It’s an adversarial approach to auditing that pushes the boundaries of privacy guarantee analysis, prompting investigation into more robust and tighter methods for privacy analysis in DP-ML. The success of this approach also suggests the need for improved DP-SGD implementation guidelines that explicitly consider the impact of model initialization on overall privacy.

Black-Box Tightness#

The concept of ‘Black-Box Tightness’ in the context of differentially private machine learning (DP-ML) audits focuses on how accurately an audit can estimate the true privacy leakage of a DP-ML model when the auditor only has black-box access. Tightness refers to the closeness of the empirically estimated privacy loss to the theoretical privacy guarantee. A high degree of black-box tightness is crucial because it indicates the reliability of the privacy claims made about the model. Achieving high tightness in a black-box setting is challenging, as the adversary has limited information about the model’s internal workings. The paper’s contribution likely involves a novel auditing technique that improves the accuracy of this estimation under black-box conditions, perhaps by carefully selecting initial model parameters or using advanced attack strategies. A key finding might be that, contrary to prior beliefs, relatively tight audits are achievable even with limited information, provided specific methods are applied. This is of great significance in evaluating real-world DP-ML deployments, as it allows for a more robust assessment of privacy guarantees without needing full white-box access which is often impractical.

Dataset Size Impact#

The analysis of “Dataset Size Impact” within the context of differentially private machine learning (DP-ML) audits reveals a nuanced relationship between dataset size and the tightness of privacy guarantees. Smaller datasets generally lead to tighter audits, enabling more precise estimation of the actual privacy leakage compared to the theoretical bounds. This is because with fewer samples, the impact of noise introduced for privacy is relatively greater, making it easier to distinguish between neighboring datasets. However, this advantage is counterbalanced by the fact that smaller datasets might compromise the statistical power of the audit and, ultimately, the reliability of the conclusions drawn from it. Larger datasets, while beneficial for generalizing model performance, reduce the relative impact of noise and make the task of distinguishing between similar datasets more challenging. This is shown through the experiment which uses only half of the available dataset for training, leading to empirically tighter privacy leakage estimates compared to the training with a full dataset. The study highlights the trade-off between a tighter audit and a sufficient number of samples for reliable statistical results. The optimal dataset size for DP-ML audits is thus dependent on the desired balance between audit precision and the overall reliability of the resulting conclusions, and this may vary depending on the specific task, algorithms, and evaluation metrics used. Further investigations are needed to determine the optimal size range for different settings.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending this work to deeper neural networks and larger datasets, while addressing the computational challenges of training numerous models for auditing. Investigating the impact of different optimization algorithms and hyperparameter tuning strategies on audit tightness is also warranted. Furthermore, a deeper dive into the theoretical underpinnings of DP-SGD, particularly for scenarios with subsampling, could yield tighter privacy analysis and more accurate auditing procedures. Finally, exploring alternative auditing methods, potentially those requiring fewer model training runs, warrants further attention, along with broadening the scope to encompass more diverse machine learning models and datasets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

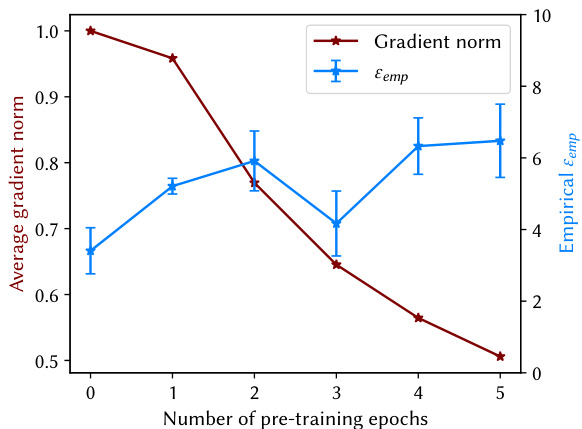

This figure shows the relationship between the average gradient norm and the empirical privacy leakage (εemp) for models trained on the MNIST dataset with a theoretical privacy parameter ε of 10.0. The x-axis represents the number of pre-training epochs used to craft the worst-case initial model parameters. The y-axis shows both the average gradient norm (in maroon) and the empirical privacy leakage (in light blue). The figure demonstrates that as the number of pre-training epochs increases, the average gradient norm decreases, while the empirical privacy leakage increases. This suggests that minimizing the gradients of normal samples through pre-training makes the target sample’s gradient more distinguishable, leading to tighter privacy audits.

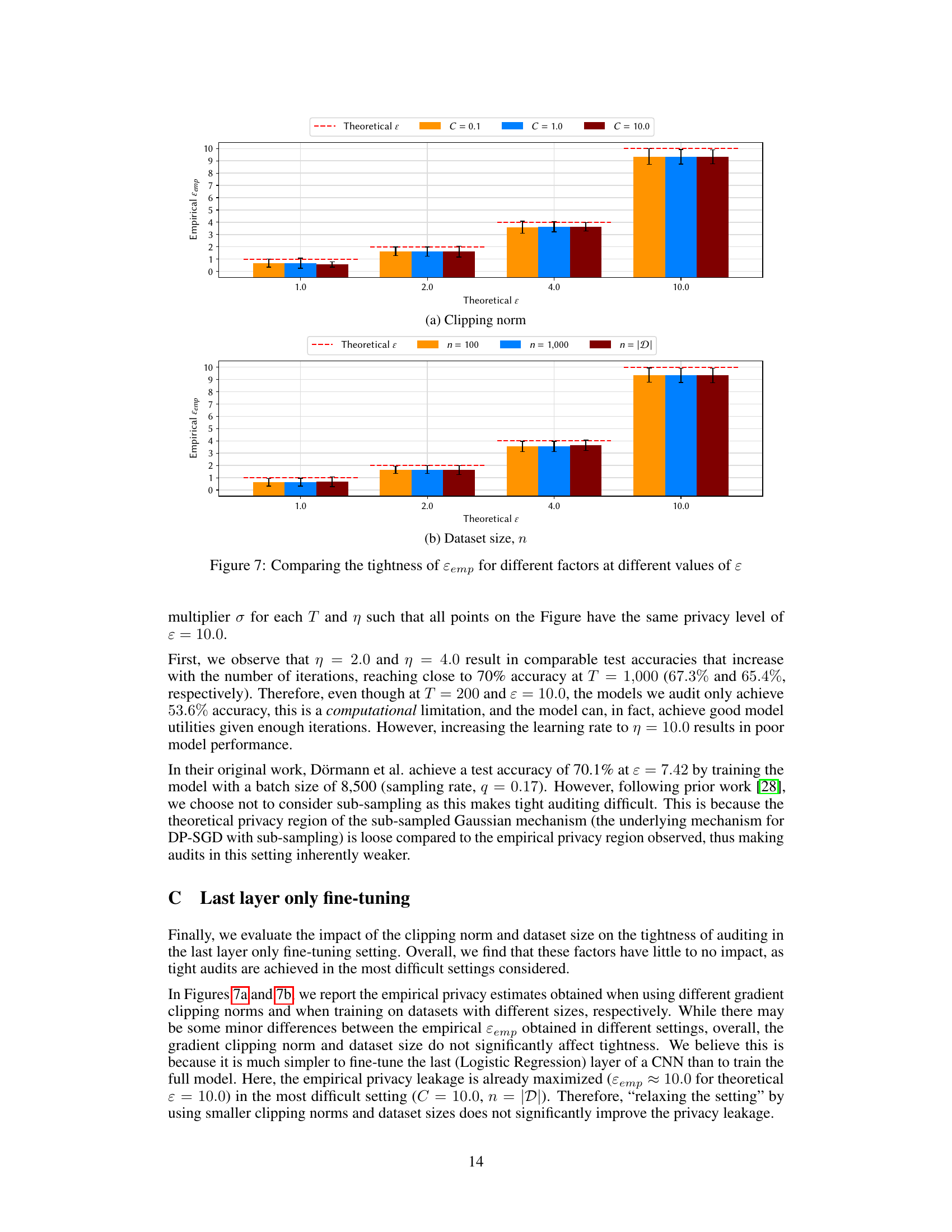

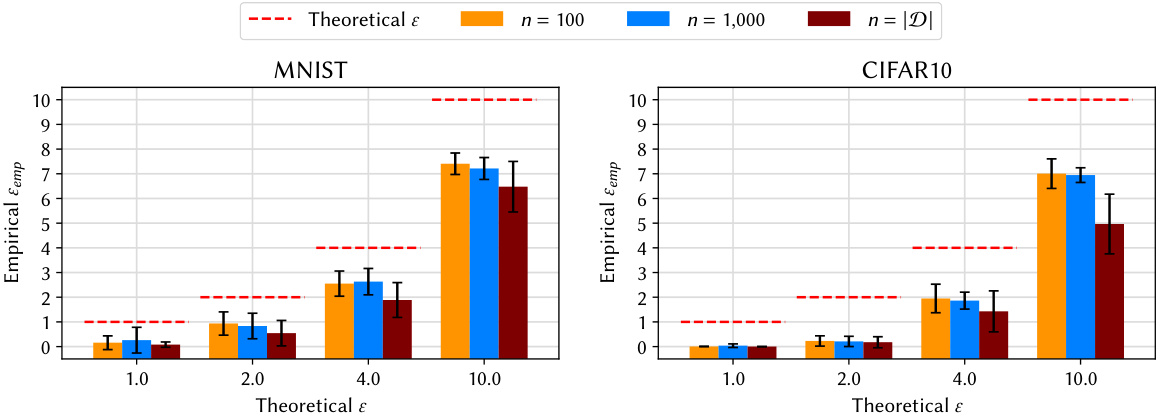

This figure displays the results of auditing models trained on different dataset sizes (n = 100, n = 1000, n = |D|, where |D| represents the full dataset size) at various privacy levels (ε). The plot shows the empirical privacy leakage (ε_emp) estimated using the auditing procedure. The results are shown separately for the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The purpose is to analyze how the size of the training dataset impacts the tightness of the privacy audit, comparing smaller subsets to the complete datasets. The theoretical privacy level (ε) is also shown for comparison.

This figure shows the result of auditing models trained with different gradient clipping norms (C = 0.1, 1.0, 10.0) at various privacy levels (ε). It compares the empirical privacy leakage (ε_emp) against the theoretical privacy guarantee (ε) for both MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The error bars represent the standard deviation across multiple runs. The figure aims to demonstrate the impact of the gradient clipping norm on the tightness of the black-box audits, showing how smaller clipping norms lead to tighter audits.

This figure compares the empirical privacy leakage (ε_emp) obtained using average-case and worst-case initial model parameters for different theoretical privacy levels (ε). The worst-case parameters were crafted to maximize the privacy leakage. The figure shows that using worst-case initial parameters leads to significantly tighter audits (ε_emp closer to the theoretical ε) than using average-case parameters, especially at higher values of ε. Error bars represent standard deviation across five independent runs.

This figure shows the test accuracy of models trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset with different learning rates (η = 2.0, 4.0, and 10.0) and varying numbers of iterations (T). The privacy parameter (ε) was fixed at 10.0 for all experiments. The plot illustrates how the model’s performance improves with increasing training iterations, and how the optimal learning rate may change depending on the number of iterations. Higher learning rates can lead to faster initial improvement but might result in lower accuracy at convergence.

This figure compares the empirical privacy leakage (εemp) against the theoretical privacy parameter (ε) for different experimental settings. Subfigure (a) shows the effect of varying the gradient clipping norm (C) on the tightness of the audits. Subfigure (b) shows the impact of different dataset sizes (n) on εemp, comparing results from using 100, 1000 and the full dataset size. The results are presented for four different values of the theoretical privacy parameter ε (1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 10.0). Error bars represent the standard deviation across five independent runs.

Full paper#