↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

High-quality human feedback is crucial for training effective AI models, but obtaining it is expensive and time-consuming. This paper tackles the challenge of efficiently gathering human feedback using optimal designs, a methodology for computing optimal information-gathering policies, generalized to handle questions with multiple answers. The current methods have limitations in their efficiency and effectiveness, especially when dealing with complex scenarios involving multiple choices and ranking tasks.

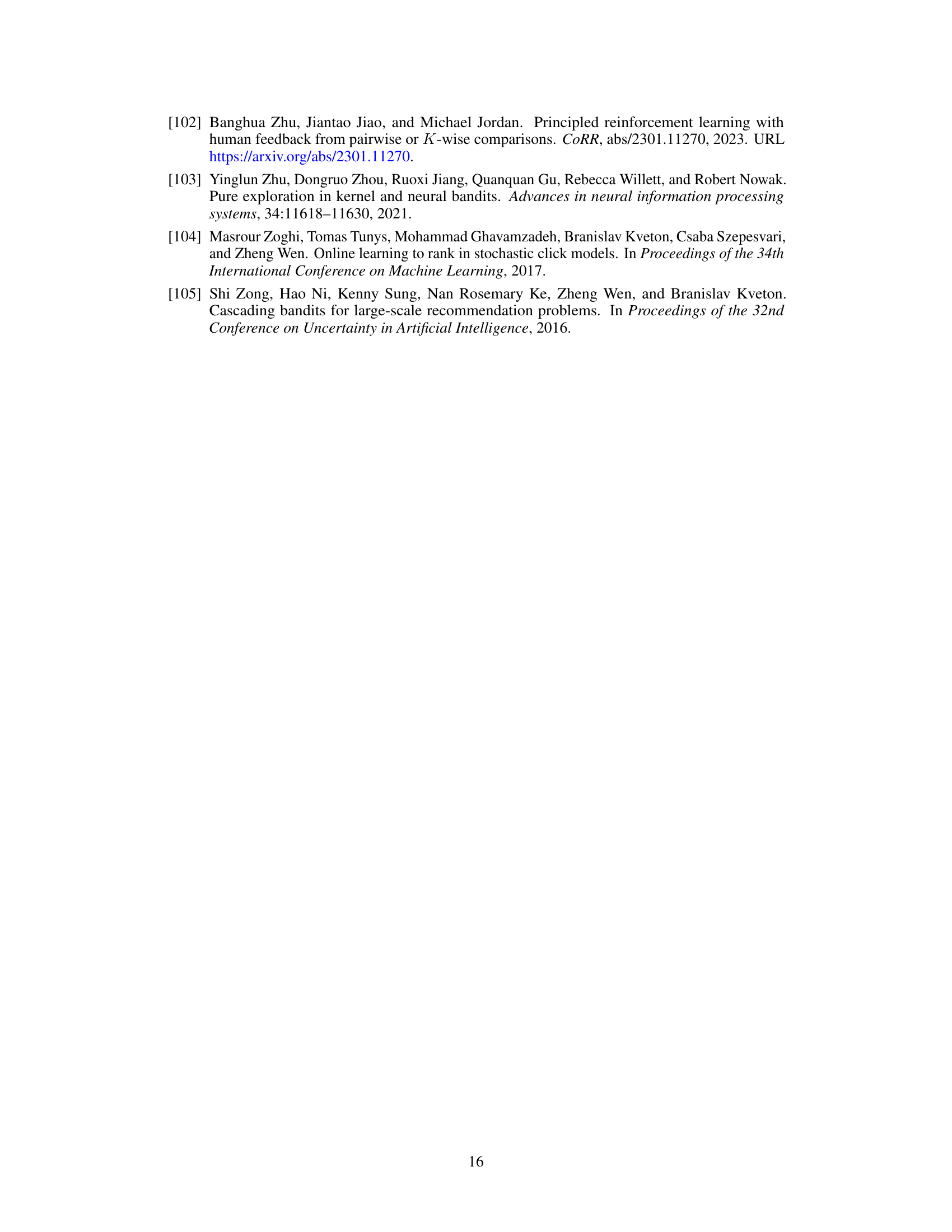

This research proposes novel algorithms called “Dope” that effectively address this challenge. Dope uses optimal designs to select the most informative lists of items, thereby maximizing the information gained from each human interaction. The algorithms are designed for both “absolute” (noisy reward for each item) and “ranking” (human-provided ranking of items) feedback models. The paper provides theoretical guarantees on the performance of the algorithms and demonstrates their practical efficacy through experiments on question-answering problems, showcasing significant improvement in ranking loss compared to existing baselines.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and human-computer interaction because it introduces efficient algorithms for human preference elicitation, a critical task in many AI applications. The work bridges the gap between theory and practice by offering both theoretical analysis and practical evaluation. It also opens up new avenues for research into optimal design and adaptive methods for collecting high-quality human feedback.

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the performance of five different methods for learning to rank items using human feedback, across four different datasets. The x-axis represents the number of human feedback interactions. The y-axis represents the ranking loss, a metric indicating how well the learned ranking matches the true, optimal ranking. The five methods are: Unif (uniformly random sampling), Dope (the authors’ proposed method), Avg Design (average design), Clustered Design (clustered design), and APO (a baseline algorithm from related work). The plots show that Dope generally outperforms the other methods in terms of lower ranking loss across all datasets, demonstrating its efficiency in learning to rank from human feedback. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean ranking loss.

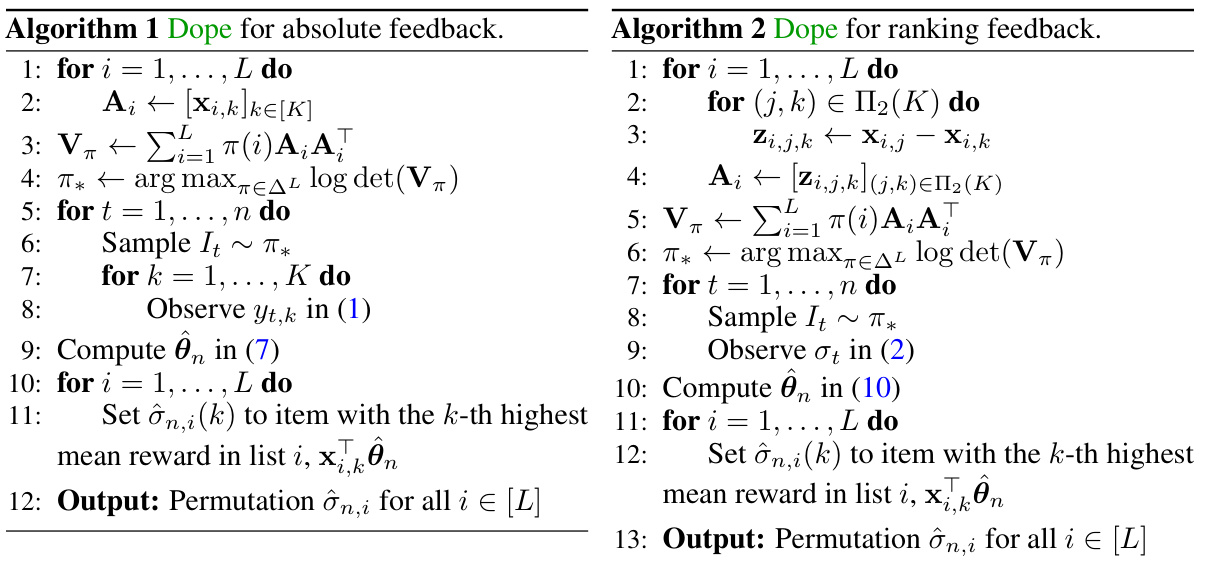

This table compares the performance of the proposed algorithm, Dope, against several plug-in design baselines and the theoretically optimal solution. The comparison is based on maximum prediction error and ranking loss. The plug-in methods vary the number of initial rounds used for estimating the model parameters before switching to the plug-in design.

In-depth insights#

Optimal Design#

The heading ‘Optimal Design’ likely refers to a section discussing efficient strategies for gathering human preference data. The core idea revolves around generalizing optimal design methodologies from traditional statistical settings to handle scenarios with multiple answer choices (e.g., lists of items). This generalization likely involves formulating policies that determine the probability of selecting specific lists for human evaluation. The research likely explores both absolute feedback models (noisy rewards per item) and ranking feedback models (human-provided item rankings). Efficient algorithms for both are likely presented and their performance is evaluated. A key contribution may involve a matrix generalization of the Kiefer-Wolfowitz theorem, enabling efficient computation of the optimal list selection distribution. The overall goal is to minimize the ranking loss or prediction error within a constrained budget of human queries, leading to a more efficient and cost-effective approach to learning preference models. The practical applicability is demonstrated via experiments on question-answering problems.

Feedback Models#

The concept of “Feedback Models” in a research paper is crucial for understanding how human interaction informs machine learning models. It would explore different ways humans provide feedback, such as absolute ratings (e.g., assigning scores to items) or relative rankings (e.g., ordering items by preference). The choice of feedback model significantly impacts the efficiency and accuracy of model training. Absolute feedback is simpler to collect but may be less informative than relative feedback, which provides finer-grained comparisons between items. The paper might analyze the statistical properties of each feedback model, discussing its strengths and limitations in terms of data efficiency and computational cost. A key consideration would be the noise inherent in human feedback; how this is modeled mathematically impacts model accuracy and interpretation. Ideally, the paper would compare the effectiveness of different feedback models, perhaps showcasing optimal design strategies to minimize the amount of data needed while maximizing learning outcomes. Ultimately, a thoughtful discussion of feedback models sheds light on the human-in-the-loop aspect of machine learning and is critical for designing robust and effective systems.

Dope Algorithm#

The DOPE algorithm, designed for efficient human preference elicitation, tackles the challenge of learning preference models cost-effectively. It cleverly generalizes optimal design methodologies to handle multiple-answer questions, framing them as lists of items. The algorithm’s core innovation lies in its efficient computation of an optimal distribution over these lists, prioritizing the most informative queries for human feedback. This approach ensures that valuable human effort is focused precisely where it yields the greatest improvement in model learning. Two key feedback models are considered: absolute (noisy rewards per item) and ranking (human-provided item order). Dope adapts to both, showcasing its versatility. The algorithm’s effectiveness is further bolstered by its theoretical analysis, including prediction error and ranking loss bounds, and demonstrated empirically through experiments on real-world question-answering datasets. Dope’s strength resides in its non-adaptive nature, allowing pre-computation of the optimal query strategy, resulting in significant efficiency gains compared to adaptive methods that explore excessively. The algorithm stands out for its practical applicability and theoretical rigor, offering a significant advancement in efficient preference model learning.

Empirical Results#

The empirical results section would ideally present a robust evaluation of the proposed DOPE algorithm. This would involve comparisons against multiple baselines, such as uniform sampling, average design, clustered design, and other relevant learning-to-rank approaches. Key performance indicators would be the ranking loss (Kendall Tau distance), possibly supplemented by other metrics like NDCG or MRR. The results should be presented across various datasets, showcasing the algorithm’s generalizability. Crucially, the choice of datasets should be justified and representative of real-world challenges in preference elicitation. Statistical significance testing (e.g., t-tests or bootstrapping) should be employed to confirm the reliability of the findings. Finally, an in-depth analysis of the algorithm’s efficiency, both computational and sample complexity, should be provided, demonstrating its practical applicability and scalability. Discussion on the relationship between hyperparameter tuning (if any) and performance would strengthen the evaluation further. Visualizations such as plots showing the ranking loss over different numbers of rounds would aid in the comprehension of the results, allowing for a clearer understanding of the algorithm’s learning curve. In short, a strong empirical results section would build compelling evidence for the proposed method’s effectiveness and practical value.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to incorporate other ranking metrics beyond Kendall tau, such as NDCG and MRR, would strengthen the evaluation. Investigating alternative feedback models beyond absolute and ranking, encompassing richer forms of human feedback, like partial rankings or comparative judgments, is crucial. Analyzing the impact of non-integer allocations in the optimal design, and developing robust methods to handle this practically, is essential for real-world applications. Exploring adaptive algorithms that combine optimal designs with adaptive strategies to enhance exploration and reduce regret warrants attention. Finally, applying these methods to diverse real-world problems, evaluating their efficiency and effectiveness in different domains, and comparing them against other state-of-the-art learning-to-rank techniques would provide valuable insights and practical impact.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the proposed Dope algorithm with several plug-in design baselines and the optimal solution (which is not practically feasible). The comparison is based on two metrics: maximum prediction error and ranking loss. The plug-in designs vary in the number of rounds used for initial exploration before plugging in an estimate of the model parameter. The table shows that Dope achieves a good balance between prediction error and ranking loss, outperforming the plug-in baselines with smaller numbers of exploration rounds, while being reasonably close to the optimal performance.

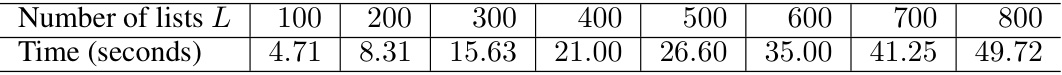

This table shows how the computation time for the optimal design policy (π*) scales with the number of lists (L). The computation time is measured in seconds and increases roughly linearly with L. This demonstrates the efficiency of the algorithm for computing the optimal distribution over lists, even with a relatively large number of lists.

This table presents the ranking loss achieved by the DOPE algorithm under various conditions. The ranking loss is the evaluation metric used to assess the performance of the algorithm in ranking items. The table shows how this ranking loss varies depending on two factors: (1) the number of lists (L), and (2) the number of items per list (K). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

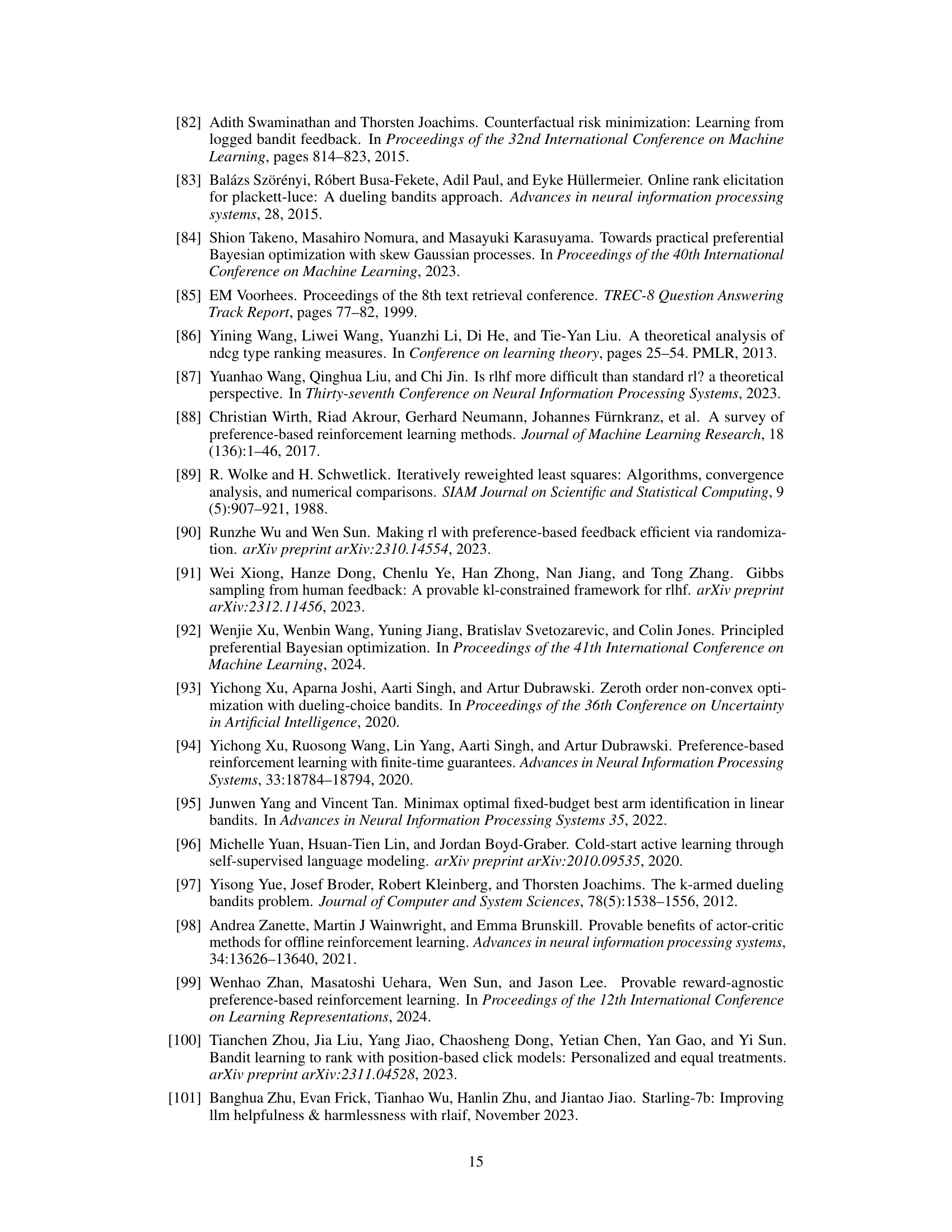

Full paper#