↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional event-based algorithms often split event streams into fixed-duration or fixed-count groups, losing crucial temporal information, especially in dynamic scenarios. This can lead to information loss or redundancy, hindering the performance of downstream tasks like object tracking and recognition. These methods also require careful pre-determination of hyper-parameters which limits adaptability.

SpikeSlicer uses a low-energy SNN to dynamically determine optimal slicing points. It introduces the Spiking Position-aware Loss (SPA-Loss) to improve the SNN’s accuracy, and uses a feedback-update strategy to refine slicing decisions based on downstream ANN performance. Experimental results demonstrate that SpikeSlicer significantly improves performance in object tracking and recognition tasks. The SNN-ANN cooperation paradigm is novel and highly efficient.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and efficient method for processing event streams from event-based cameras. It addresses limitations of existing methods by using a spiking neural network (SNN) to adaptively slice event streams, improving downstream task performance. This opens new avenues for SNN-ANN cooperation and energy-efficient event processing, crucial for resource-constrained applications. The proposed SPA-Loss and feedback-update training strategy are significant contributions. The work also has high reproducibility due to detailed experimental descriptions.

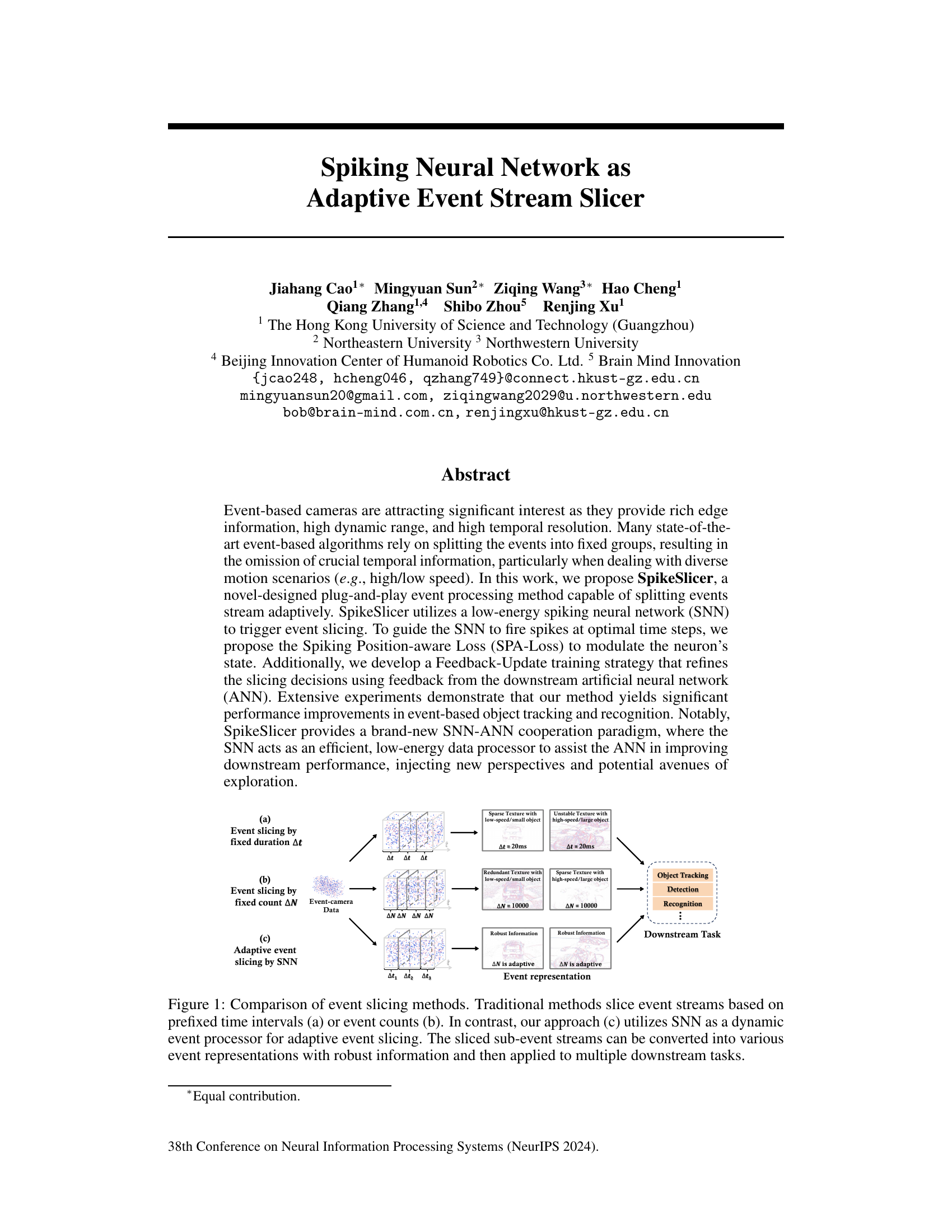

Visual Insights#

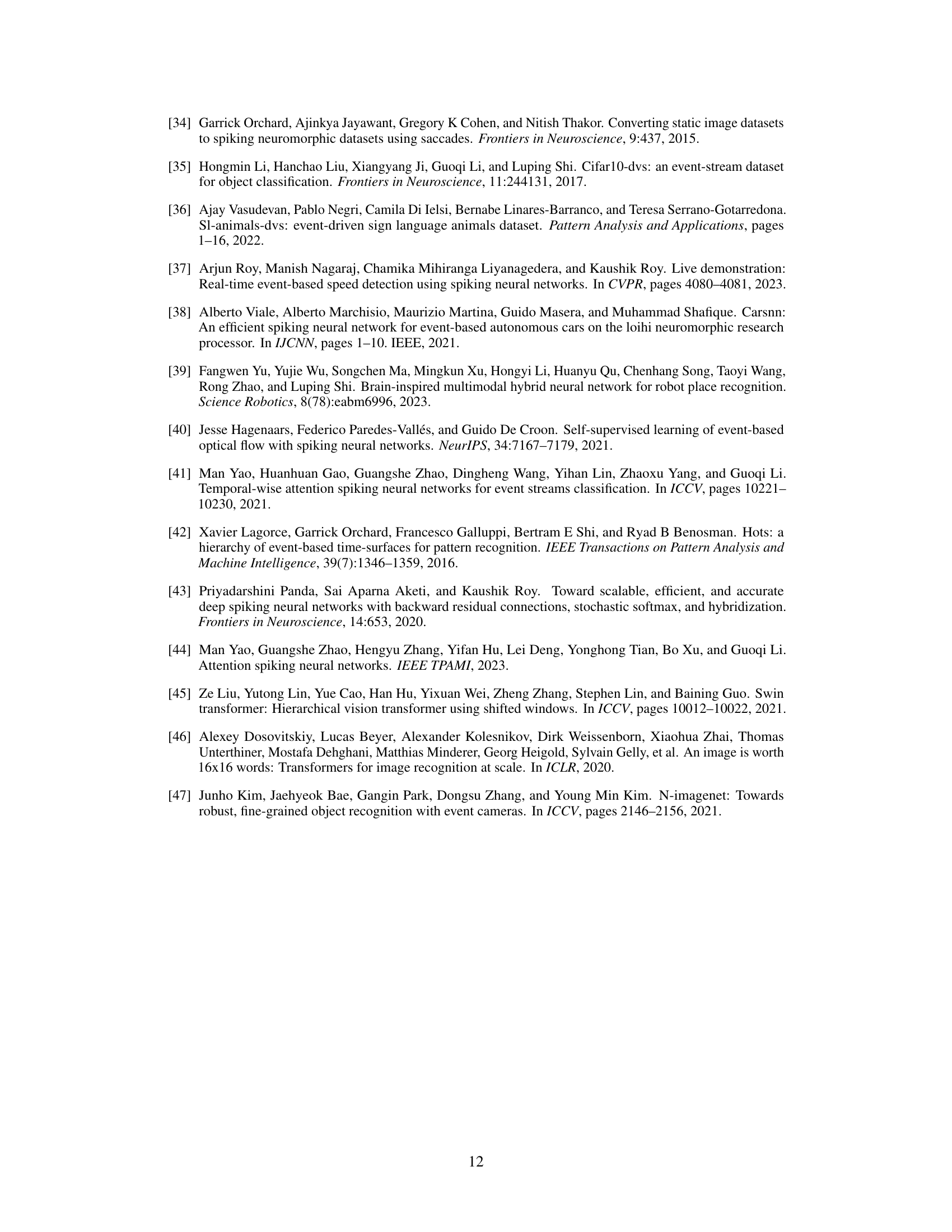

This figure compares three different event slicing methods: fixed time intervals, fixed event counts, and adaptive slicing using a spiking neural network (SNN). The fixed methods (a and b) demonstrate potential issues of either losing information in low-speed scenarios or creating redundancy in high-speed ones. In contrast, the SNN-based approach (c) adapts the slicing dynamically, leading to robust event representation for downstream tasks such as object tracking, detection, and recognition. The SNN acts as a dynamic event processor, improving information extraction by adapting to changing event density.

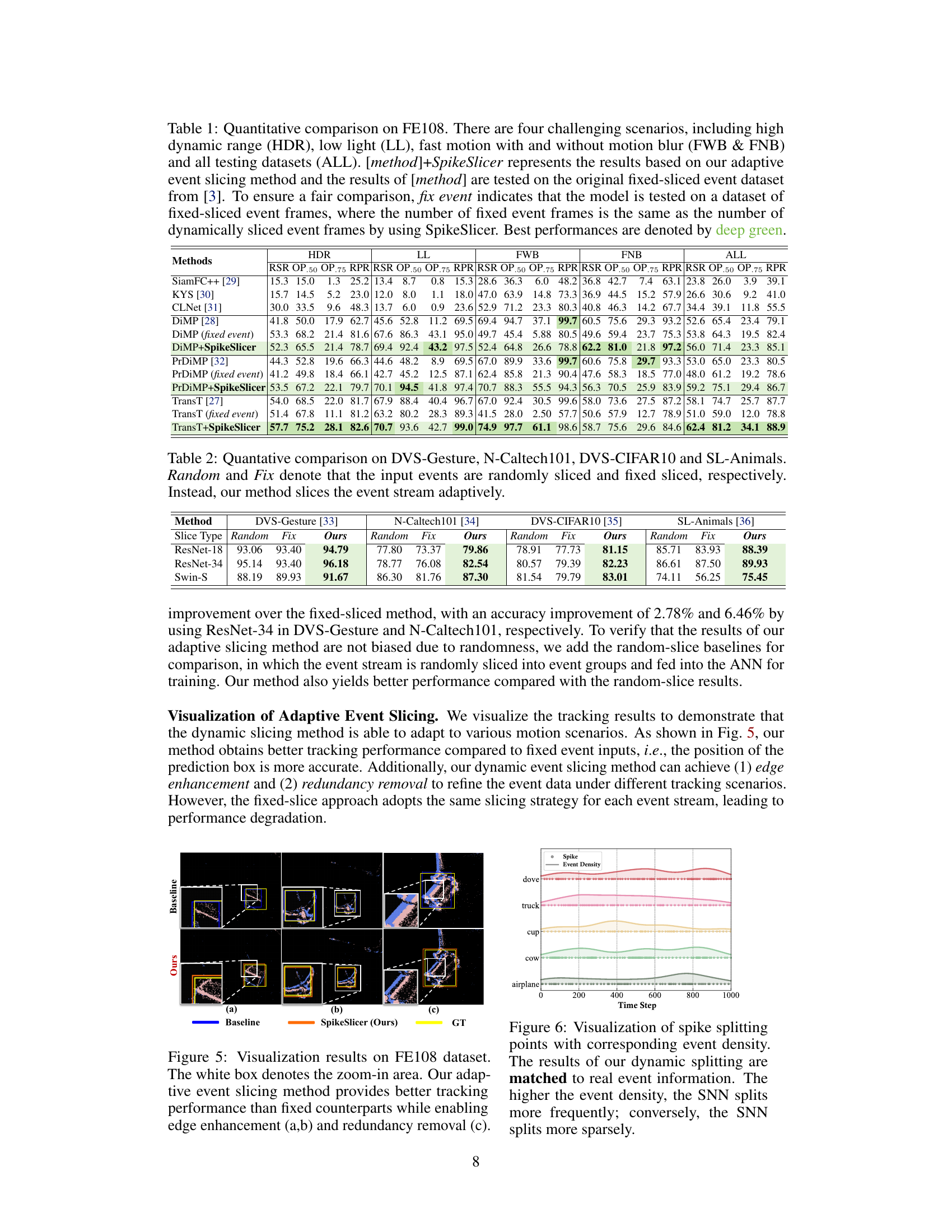

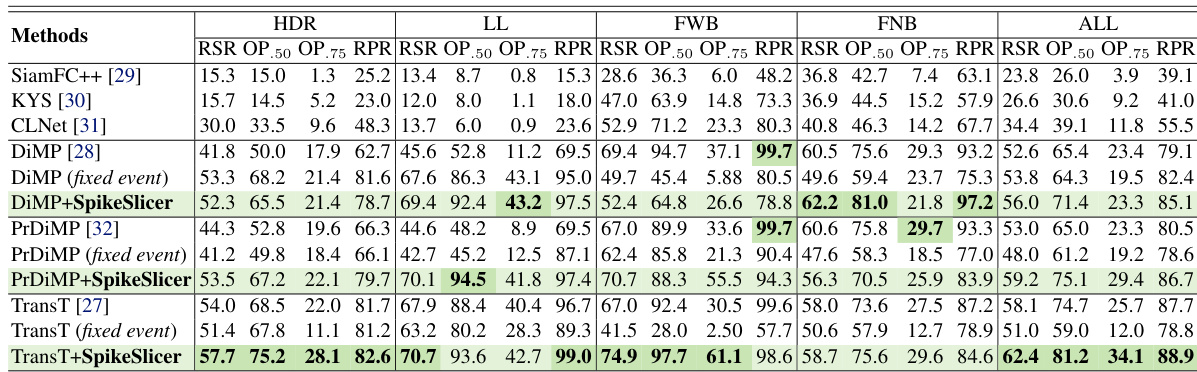

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different object tracking methods on the FE108 dataset. It compares performance across various challenging scenarios (HDR, LL, FWB, FNB) and overall. The results are shown for models both with and without the proposed SpikeSlicer adaptive event slicing method. ‘Fix event’ indicates that a model uses fixed-length event slices for comparison.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Event Slice#

Adaptive event slicing is a crucial technique in event-based vision, addressing the limitations of traditional fixed-duration or fixed-count methods. Dynamically adjusting the slicing window allows for better capture of temporal information in diverse motion scenarios, handling both high-speed and low-speed events effectively. The core idea is to adapt to the varying density and importance of events in a stream, avoiding the information loss and redundancy inherent in fixed approaches. This adaptability is key to improving downstream task performance in applications like object tracking and recognition, as it ensures the most relevant events are selected for processing. Spiking neural networks (SNNs), with their energy efficiency and event-driven nature, are ideally suited for implementing such an adaptive slicer. The use of an SNN allows for low-latency processing, making it suitable for real-time applications. A well-designed loss function is crucial for training the SNN to accurately determine optimal slicing points. The method requires careful consideration of the tradeoffs between computational cost and accuracy; the goal is to find a balance that maximizes performance improvements without introducing excessive overhead.

SNN-ANN Synergy#

The concept of ‘SNN-ANN Synergy’ in event-based vision processing is groundbreaking. It leverages the strengths of both Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to achieve superior performance. SNNs, with their energy efficiency and temporal resolution, are ideally suited for preprocessing the asynchronous event streams generated by event cameras. This preprocessing step, like adaptive event slicing, significantly reduces the computational burden on the downstream ANN. The ANN, known for its superior performance in complex tasks such as object recognition and tracking, then benefits from this streamlined input. This synergistic approach surpasses traditional methods that rely solely on ANNs, which must handle the full volume of raw event data, often resulting in increased energy consumption and decreased processing speeds. The key lies in the elegant data flow orchestrated by the SNN as a dynamic preprocessor. The SNN does not directly perform the recognition or tracking tasks, but it intelligently filters and prepares data for the ANN, enabling the latter to focus on more complex pattern recognition. This design embodies a novel paradigm of task-specific specialization, optimized for both accuracy and efficiency. The results suggest significant gains in performance, indicating the high potential for future research into SNN-ANN co-design for real-time, power-efficient event-based applications.

SPA-Loss Function#

The Spiking Position-Aware Loss (SPA-Loss) function is a novel training objective designed to enhance the accuracy of event-based slicing using Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). SPA-Loss effectively guides the SNN to fire spikes at optimal time steps, crucial for precise event stream segmentation. This is achieved by combining two key components: a Membrane Potential-driven Loss (Mem-Loss) and a Linear-assuming Loss (LA-Loss). Mem-Loss directly supervises the membrane potential to ensure a spike at the desired time, while LA-Loss addresses the challenge of ‘hill effect’ (where a spike at time n can prevent a spike at n+1). The dynamic adjustment of hyperparameters in SPA-Loss further improves performance by adapting to various event stream characteristics. The combination of Mem-Loss and LA-Loss in SPA-Loss addresses limitations of using other loss functions for SNN-based adaptive event slicing, showing its superiority in achieving accurate event stream segmentation.

Feedback Training#

Feedback training, in the context of spiking neural networks (SNNs) for event stream slicing, presents a powerful mechanism for optimizing the accuracy of event segmentation. The core concept lies in using feedback from a downstream artificial neural network (ANN) to guide the SNN’s learning process. Instead of relying solely on pre-defined loss functions, the SNN receives information about its slicing performance from the ANN. This feedback, representing the downstream task’s sensitivity to the SNN’s output, allows for a more nuanced and task-specific learning process. By iteratively refining the SNN’s slicing decisions based on the ANN’s feedback, a symbiotic relationship emerges where the SNN acts as a low-power, adaptive event pre-processor enhancing the overall system accuracy and efficiency. The feedback loop is crucial for adapting to diverse motion scenarios and optimizing the temporal dynamics of the event stream, avoiding the limitations of fixed-time or fixed-count slicing methods. A key challenge lies in designing effective strategies to incorporate and utilize this feedback signal within the SNN’s training process, impacting the network’s architecture and loss function.

Future Exploration#

Future exploration in adaptive event stream slicing using spiking neural networks (SNNs) could significantly benefit from investigating alternative SNN architectures beyond the Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) model used in this study. Exploring more sophisticated neuron models could lead to improved accuracy and efficiency. A deeper investigation into the feedback-update mechanism between the SNN and ANN is crucial. The current method relies on simple loss functions; optimizing this feedback loop with more advanced reinforcement learning techniques or advanced loss functions might enhance adaptive slicing. Exploring neuromorphic hardware implementations is a key area for future work. The current implementation uses software simulations; direct implementation on neuromorphic chips could unlock significant advantages in terms of energy efficiency and real-time processing. This is particularly crucial in resource-constrained applications. Finally, the applicability of this adaptive slicing method to other downstream tasks beyond object tracking and recognition should be thoroughly investigated, testing various event representations and exploring new benchmarks. Expanding to more complex scenarios, including higher-density events and more challenging motion patterns, is essential for assessing robustness and generalizability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

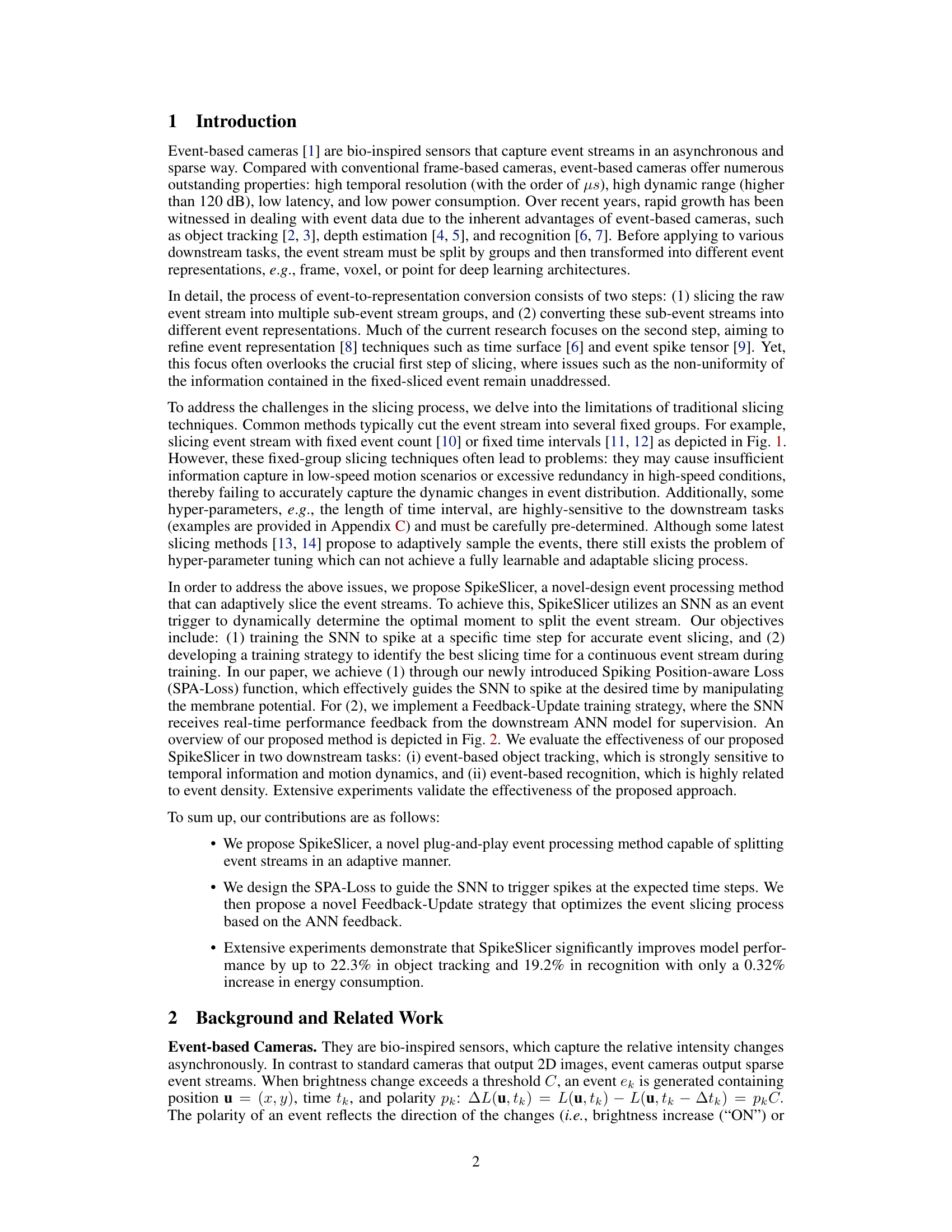

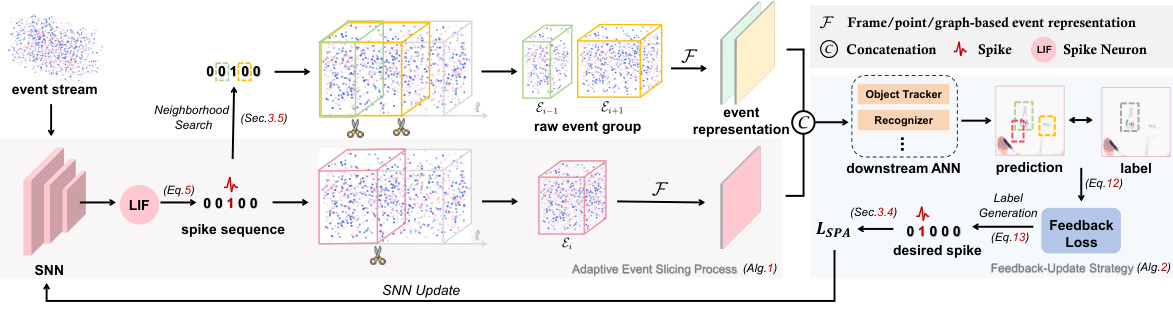

This figure illustrates the architecture of SpikeSlicer, the proposed adaptive event stream slicing method. Raw event streams are fed into a Spiking Neural Network (SNN). When the SNN fires a spike, it triggers an event slice. A neighborhood search refines the slicing time. The resulting event representations are sent to a downstream Artificial Neural Network (ANN) (e.g., object tracker or recognizer). The ANN provides feedback that refines the SNN’s slicing decisions via the Spiking Position-aware Loss (SPA-Loss).

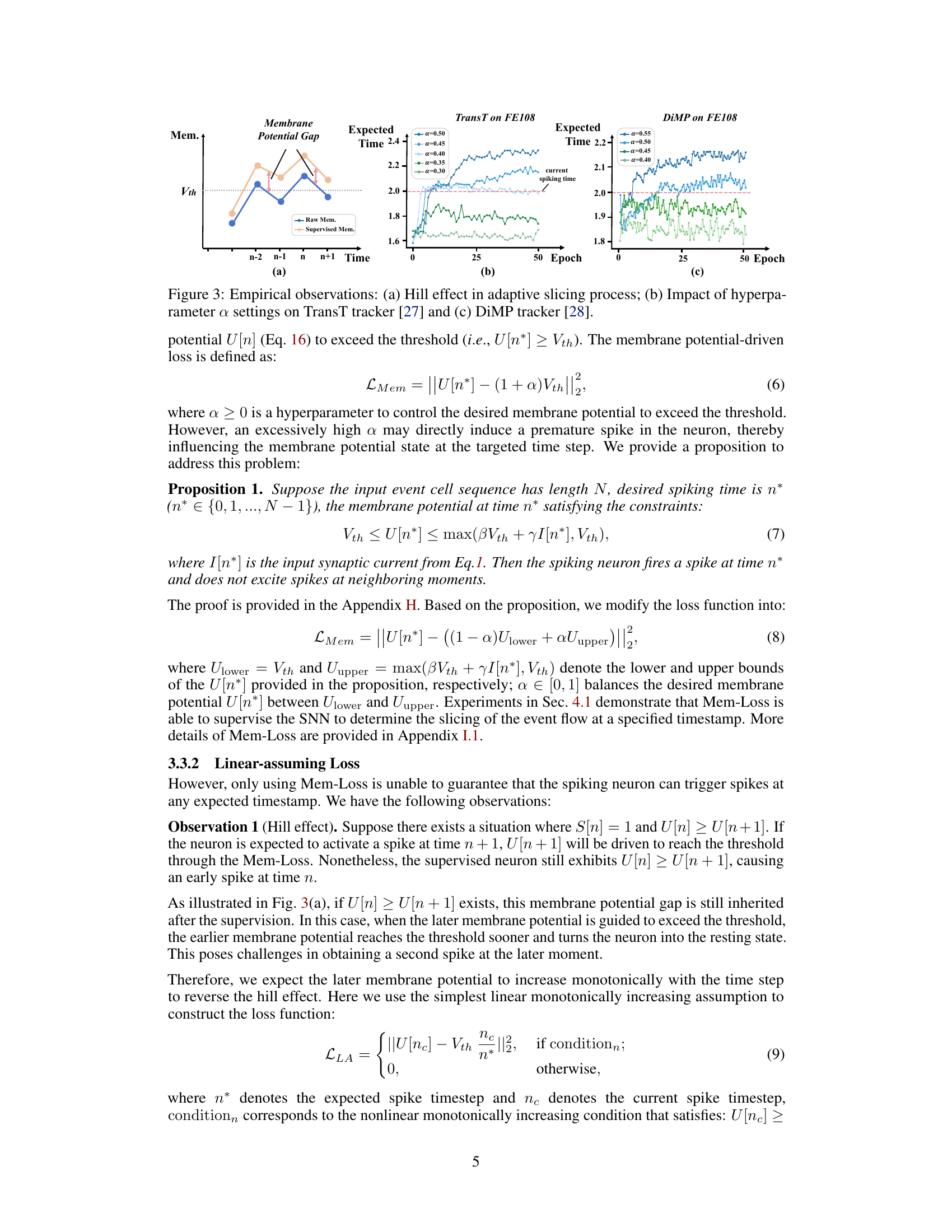

This figure demonstrates empirical observations related to the proposed method. (a) shows the Hill effect in the adaptive slicing process, illustrating the dependence phenomenon between neighboring membrane potentials. (b) and (c) illustrate the impact of hyperparameter α settings on the performance of TransT and DiMP trackers respectively, highlighting the challenges in finding the optimal value for α.

This figure compares three different event slicing methods. (a) shows traditional fixed-duration slicing, where events are grouped into fixed-length time windows. This method can miss events in high-speed motion or have redundant data in slow-speed motion. (b) shows fixed-count slicing, where a fixed number of events are grouped together. This has similar limitations to (a). (c) shows the proposed SpikeSlicer method, which uses a spiking neural network (SNN) to dynamically slice the event stream. This adaptive method is more robust to varying speeds and object sizes.

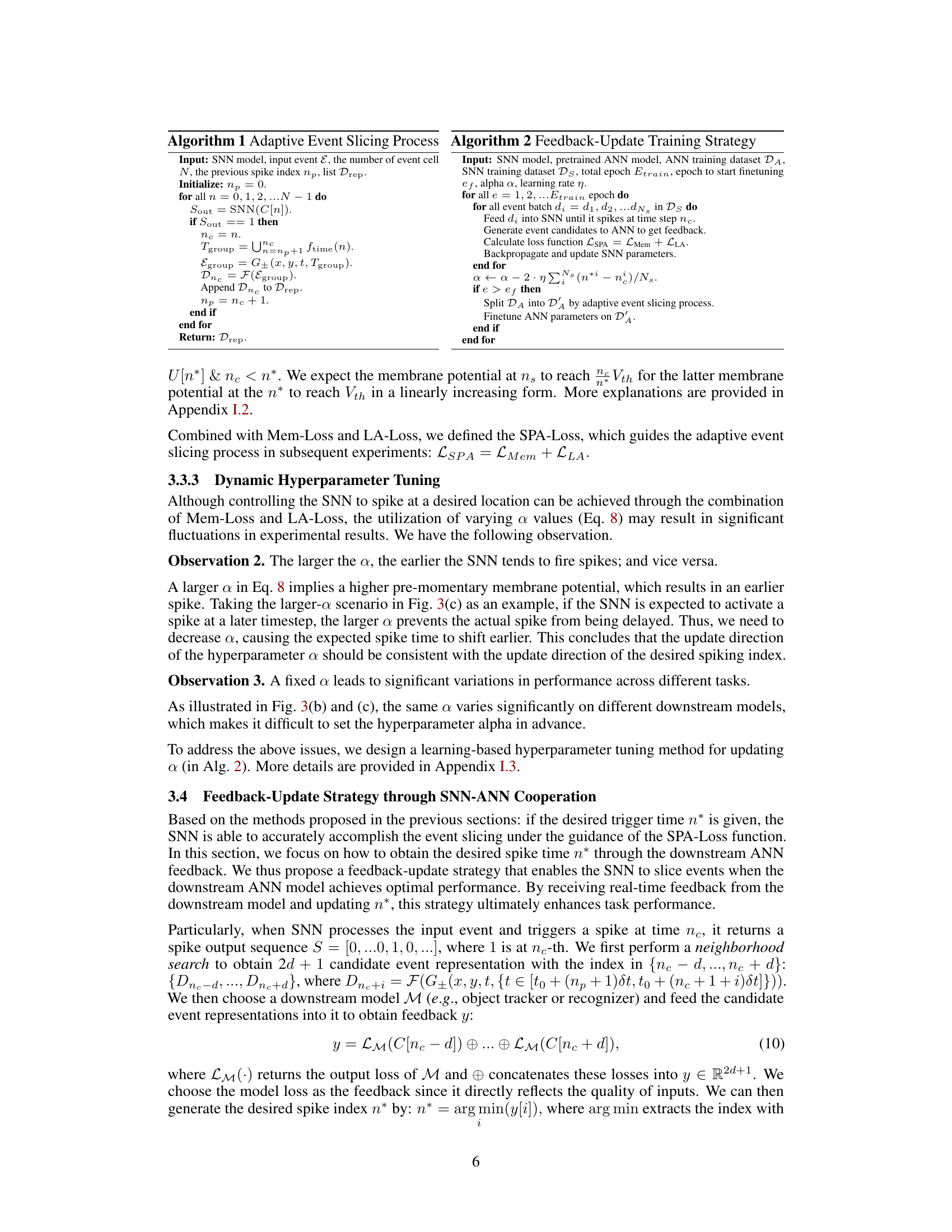

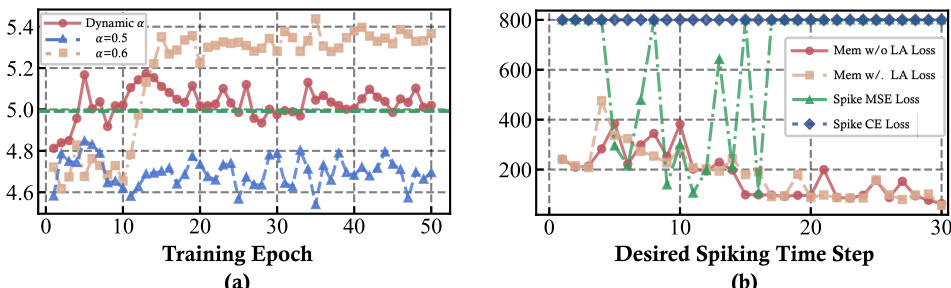

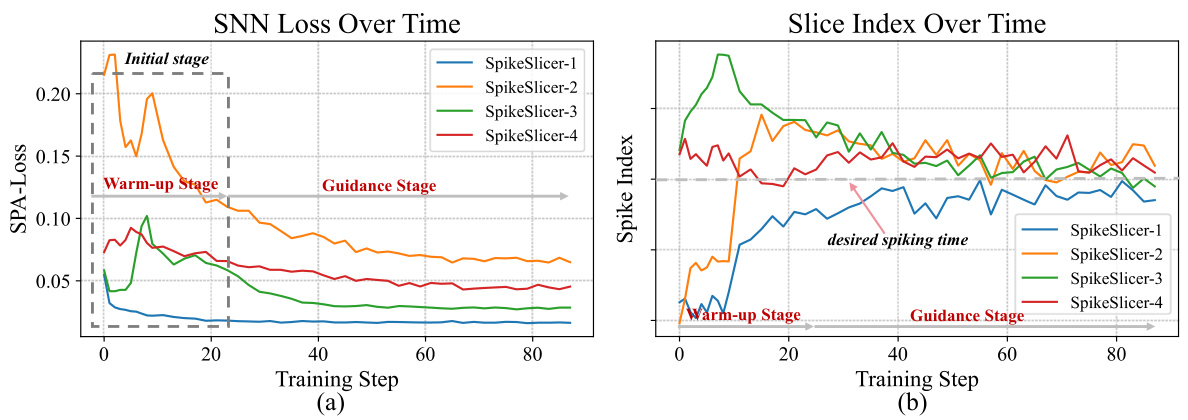

This figure presents the results of experiments comparing different loss functions for training a spiking neural network (SNN) for event slicing. (a) shows that the proposed Mem-Loss and LA-Loss converge faster than other methods to achieve the desired spiking behavior. (b) demonstrates the advantage of dynamically tuning a hyperparameter (α) in stabilizing the training process and finding the optimal spiking time, outperforming a fixed α setting.

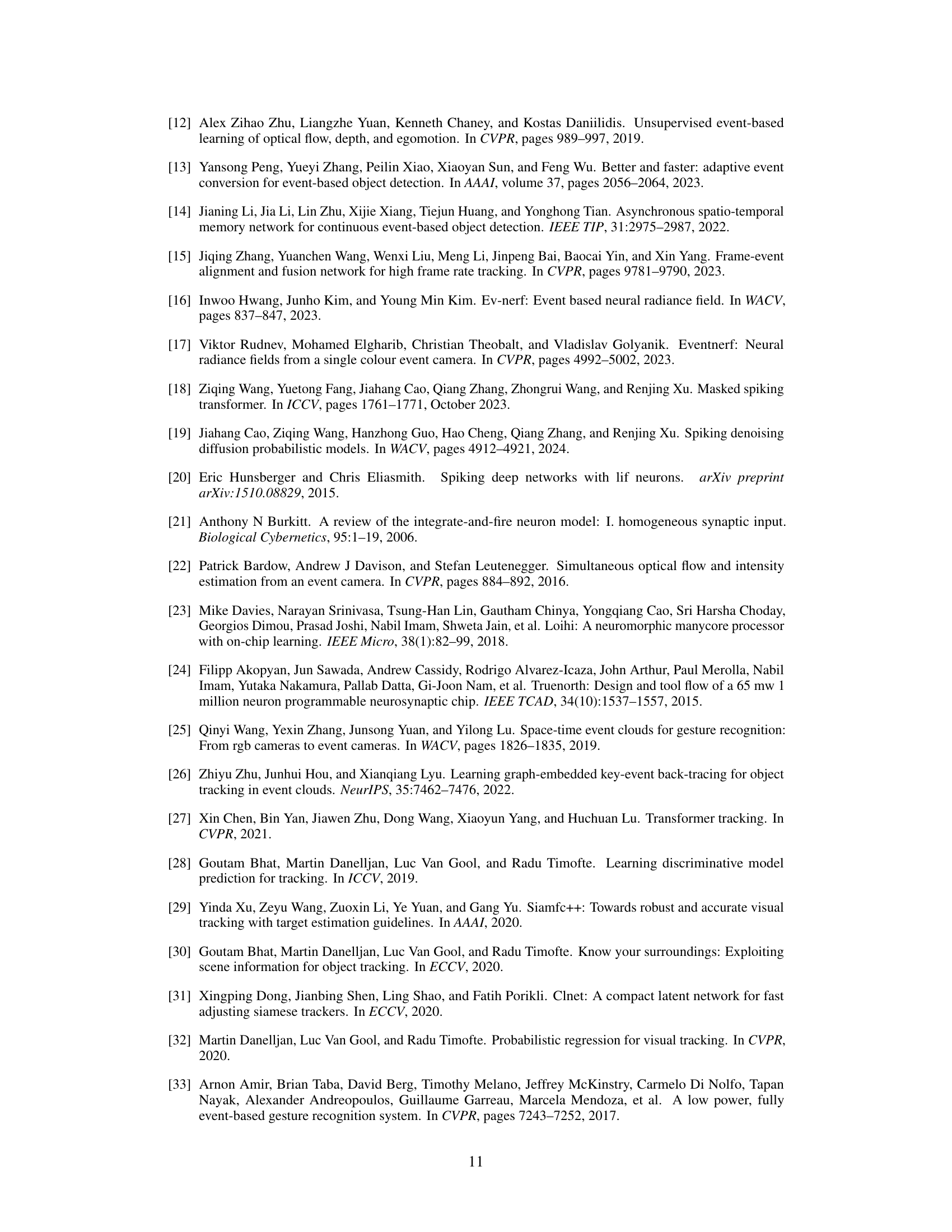

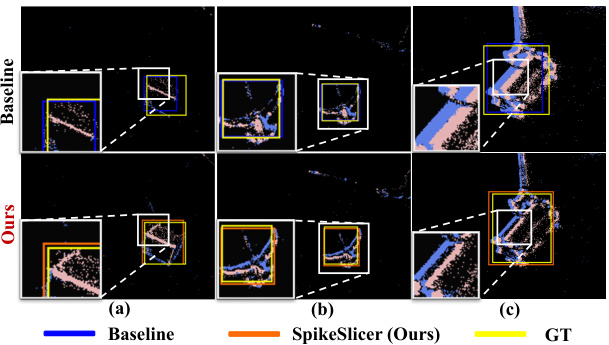

This figure compares the results of object tracking using the proposed SpikeSlicer method against a baseline method. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show example tracking results, highlighting the superior performance of SpikeSlicer in terms of accuracy and robustness, particularly in handling challenging scenarios with complex motion and varying event density. The white boxes zoom in on specific areas to better illustrate the differences between the two methods.

This figure compares the results of object tracking using the proposed SpikeSlicer method against a baseline method using fixed event slicing. The visualizations show that SpikeSlicer achieves better tracking accuracy and provides enhanced edges while removing redundant information compared to the baseline. This highlights the adaptive nature of the SpikeSlicer approach.

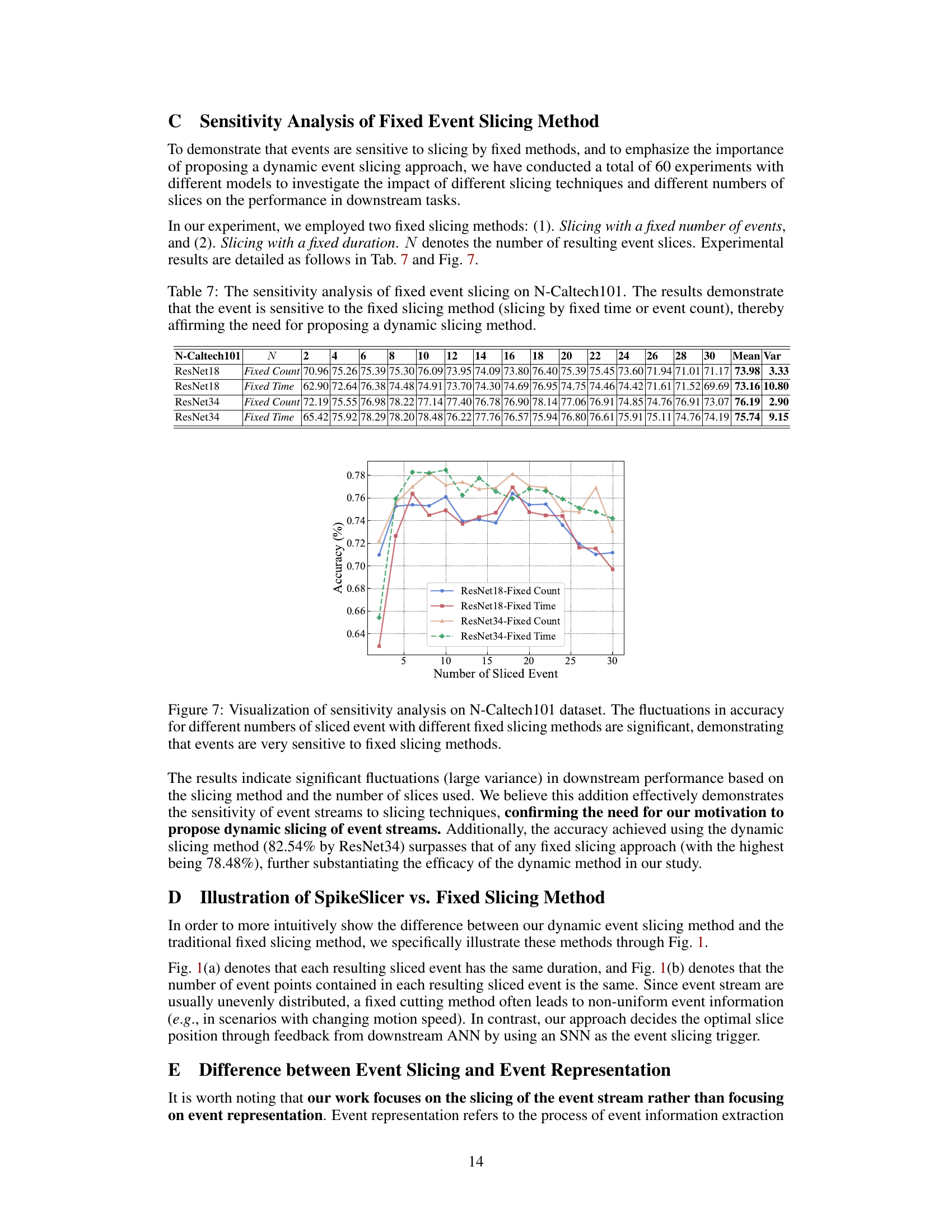

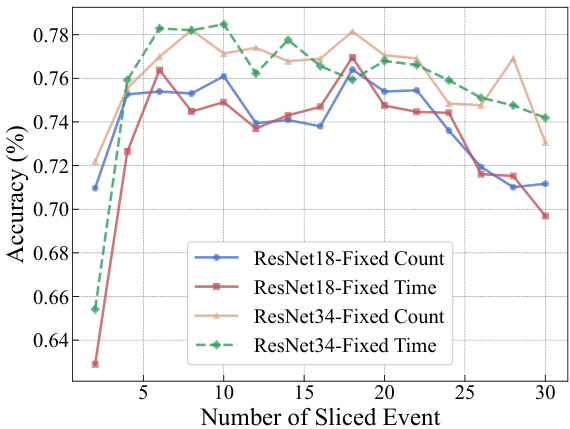

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of fixed event slicing methods on the N-Caltech101 dataset. It demonstrates that using fixed time intervals or fixed event counts to slice the event stream results in significant fluctuations in accuracy for various numbers of slices. This highlights the challenges of traditional event slicing techniques and underscores the need for a more adaptive approach like the one proposed by SpikeSlicer in the paper. Different models (ResNet18 and ResNet34) are used to assess the sensitivity.

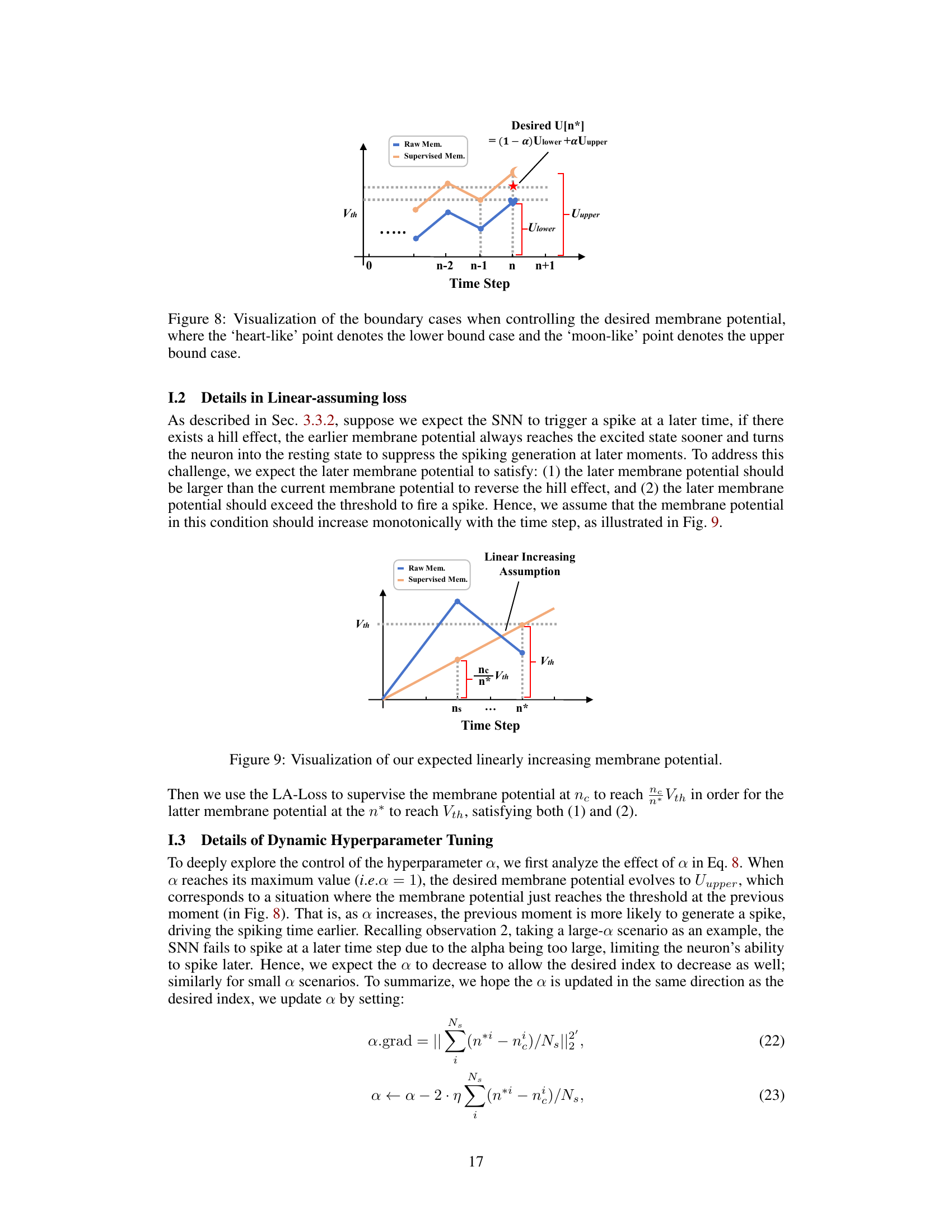

This figure illustrates the boundary conditions for the membrane potential (U[n*]) used in the membrane potential-driven loss (Mem-Loss) calculation within the Spiking Position-aware Loss (SPA-Loss) function. The lower bound ensures the membrane potential reaches the activation threshold (Vth) at the desired time step (n*), while the upper bound prevents premature spiking by limiting the membrane potential increase before n*. The figure shows how the hyperparameter ‘a’ in equation 8 balances the desired membrane potential between the lower and upper bounds.

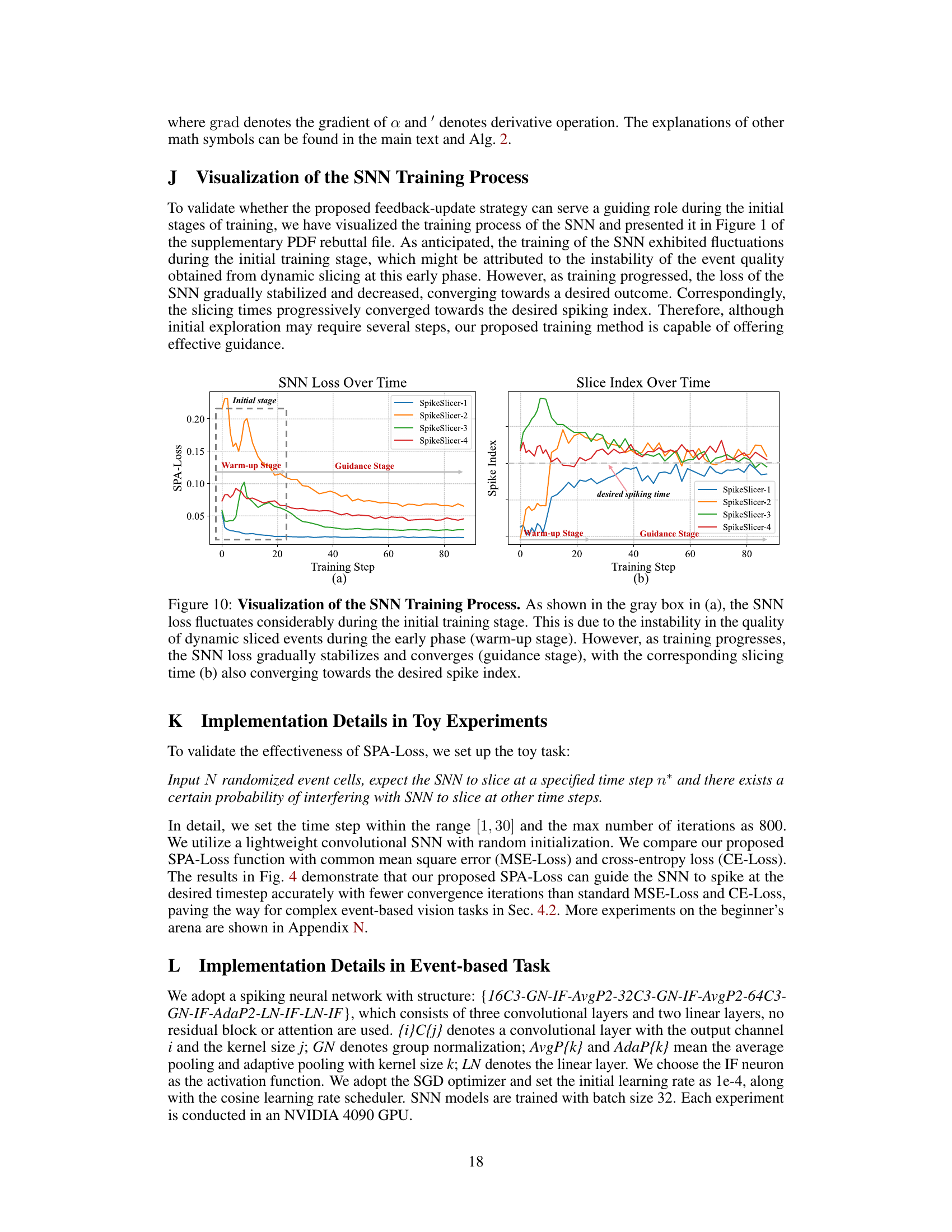

This figure illustrates the concept of the Linear-assuming Loss (LA-Loss) used in the Spiking Position-aware Loss (SPA-Loss). The LA-Loss addresses the issue of the ‘Hill effect,’ where an early spike might prevent a later, desired spike. The figure shows two membrane potential curves: raw and supervised. The supervised curve shows how the LA-Loss guides the membrane potential to increase linearly over time, ensuring that a spike occurs at the expected time (n*) without the interference from earlier spikes.

This figure illustrates the overall process of SpikeSlicer. Raw events are fed to an SNN which triggers a spike indicating an optimal slicing point. A neighborhood search refines the slicing point, and the sliced events are sent to an ANN. ANN’s feedback is used to optimize the SNN, thus creating a cooperative paradigm between SNN and ANN.

This figure compares three different event slicing methods. Traditional methods use either fixed time intervals (method a) or a fixed number of events (method b) to slice the event stream. These methods can lead to information loss, particularly in scenarios with varying motion speeds. The proposed method (c) uses a spiking neural network (SNN) to adaptively slice the event stream, resulting in more robust information extraction for downstream tasks. The figure visually shows the differences in slicing patterns and the resulting event representations.

This figure compares three different event slicing methods: fixed time interval slicing, fixed count slicing, and the proposed adaptive event slicing method using a spiking neural network (SNN). The fixed methods show limitations in handling events from varying speeds and densities, while the SNN-based adaptive method demonstrates more robust event stream slicing suitable for various downstream tasks.

More on tables

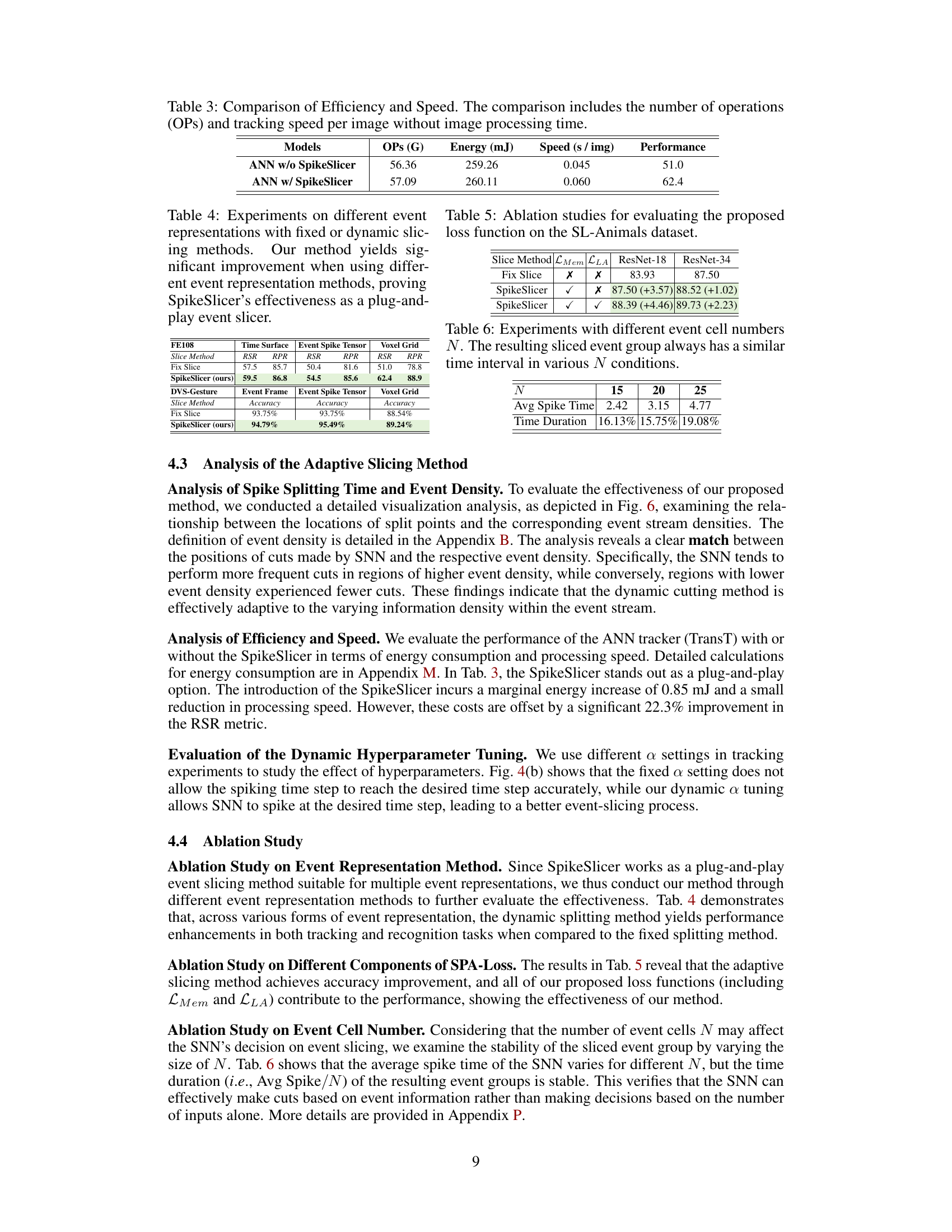

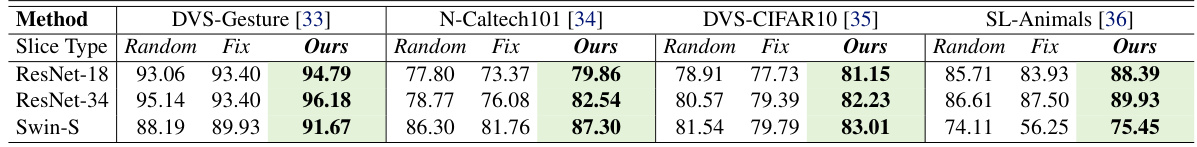

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed SpikeSlicer method against traditional fixed-sliced and random-sliced methods on four different event-based datasets: DVS-Gesture, N-Caltech101, DVS-CIFAR10, and SL-Animals. The results show the accuracy of ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and Swin-S models when using each slicing technique. The ‘Ours’ column indicates the performance using the proposed adaptive slicing method, highlighting its superior performance compared to both fixed and random slicing strategies.

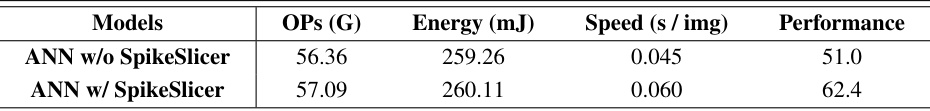

This table compares the efficiency and speed of using an ANN with and without the SpikeSlicer method for event-based object tracking. It shows the number of Giga-operations (OPs), energy consumption in millijoules (mJ), speed in seconds per image, and the performance (presumably a metric like success rate) for each approach. The results demonstrate that while adding SpikeSlicer increases the number of operations and energy consumption slightly, it significantly improves performance.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of different event representation methods (Event Frame, Event Spike Tensor, Voxel Grid) under both fixed and dynamic slicing methods. The results are shown for the DVS-Gesture dataset, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed SpikeSlicer method in improving performance across various event representations.

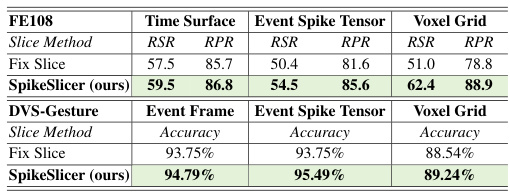

This table presents the ablation study results evaluating the effectiveness of different loss functions, specifically the proposed Mem-Loss and LA-Loss, on the SL-Animals dataset. The results are compared with the baseline using only a fixed slicing method. The table shows that the combination of Mem-Loss and LA-Loss leads to better performance on object recognition tasks.

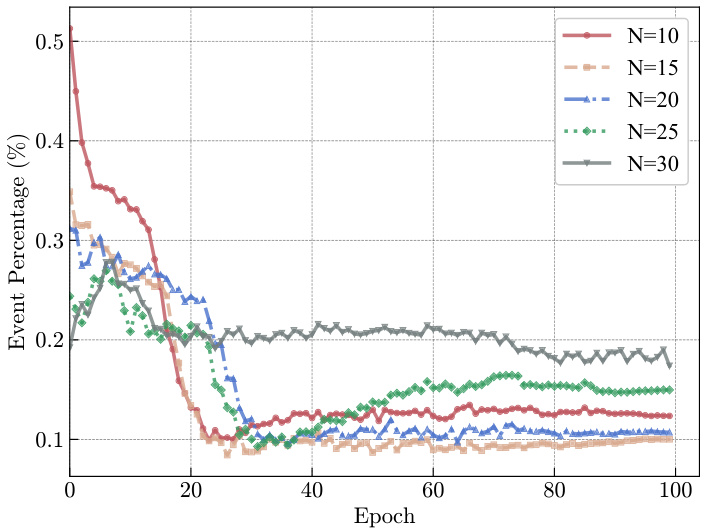

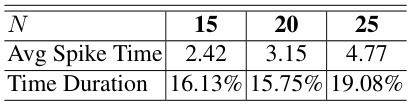

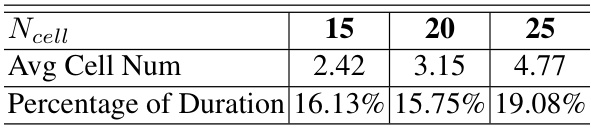

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of varying the number of event cells (N) on the adaptive event slicing process. It demonstrates the robustness of the SpikeSlicer method by showing that even when the number of event cells changes, the duration of the resulting sliced event groups remains relatively consistent. This finding highlights the algorithm’s ability to maintain consistent time intervals irrespective of input variations. This stability is important for reliable downstream processing because it ensures that the sub-event streams maintain a consistent temporal structure despite changes in data density or the granularity of the time discretization.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different object tracking methods on the FE108 dataset. It compares performance across various challenging scenarios (high dynamic range, low light, fast motion with and without blur) and evaluates the impact of the proposed SpikeSlicer method. The table shows that SpikeSlicer improves the performance of several state-of-the-art trackers, achieving best results in many scenarios. A fixed event baseline is included for fair comparison.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing different event representation methods (Event Frame, Event Spike Tensor, Voxel Grid) under three slicing methods: fixed duration, fixed event count, and the proposed SpikeSlicer. The goal was to demonstrate the effectiveness of SpikeSlicer across various event representation techniques. The results show that SpikeSlicer consistently outperforms the fixed slicing methods in terms of accuracy for the DVSGesture dataset.

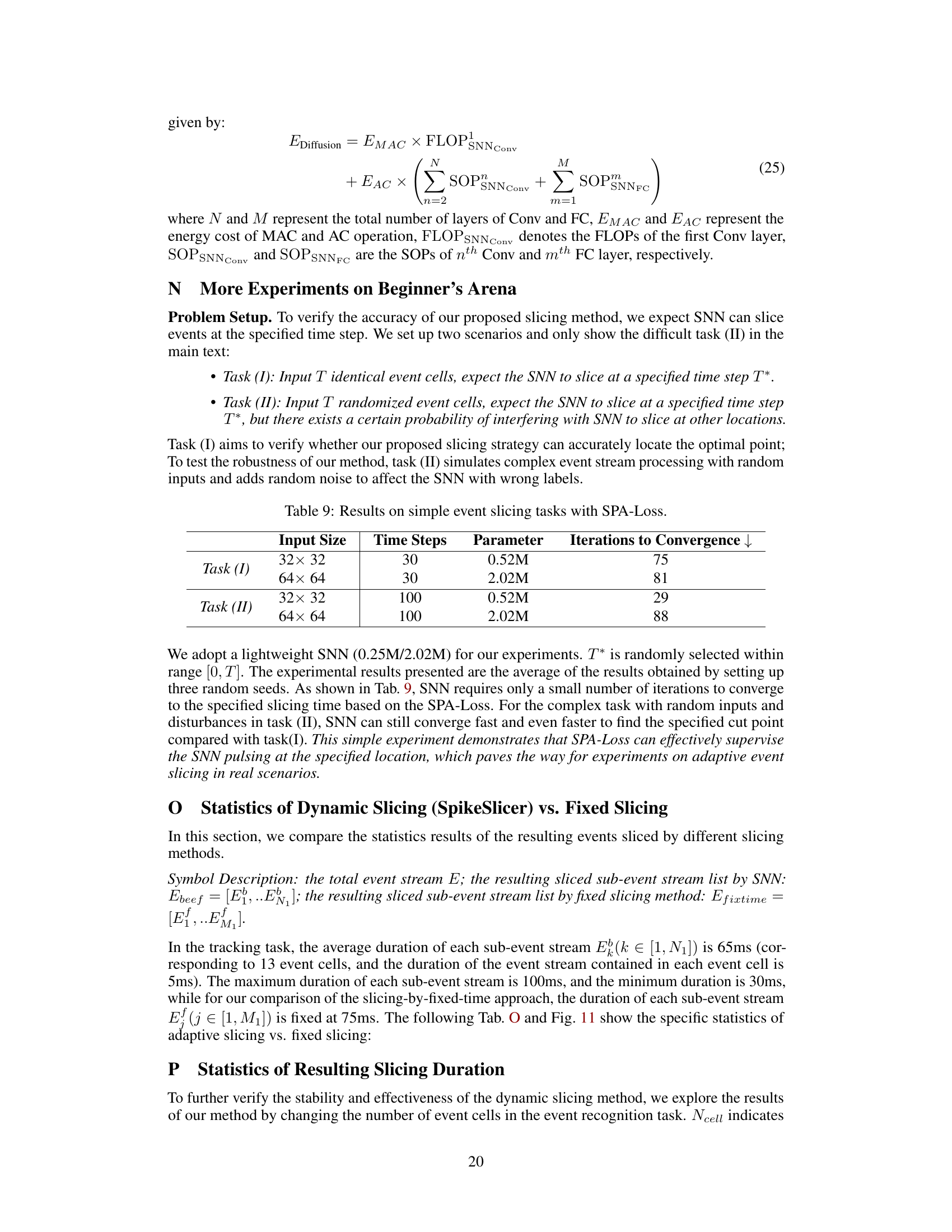

This table presents the results of experiments on simple event slicing tasks using the Spiking Position-aware Loss (SPA-Loss). Two tasks are defined: Task (I) uses identical event cells and expects the Spiking Neural Network (SNN) to slice at a specific time step. Task (II) introduces randomized event cells and noise, making it more challenging. The table shows that the SPA-Loss effectively guides the SNN to converge faster to the desired slicing time, regardless of the complexity of the task. The results are organized by input size (32x32 or 64x64), number of time steps (30 or 100), the model parameter count (0.52M or 2.02M), and the iterations needed to achieve convergence.

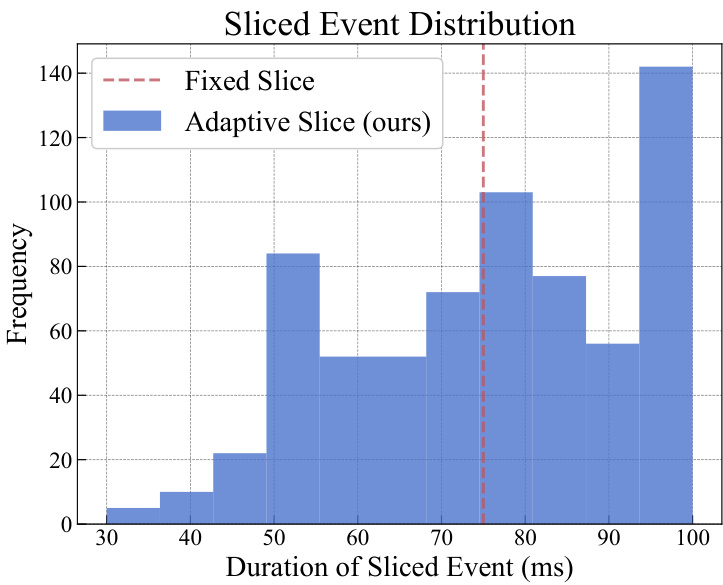

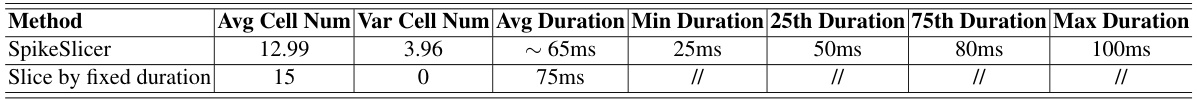

This table presents a statistical comparison of the results obtained using the proposed dynamic event slicing method (SpikeSlicer) and a fixed duration slicing method. It shows the average, variance, minimum, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and maximum durations of the sliced event streams generated by each method. The data reveals that SpikeSlicer produces a wider range of sliced stream durations, whereas the fixed duration method consistently generates streams of a single, fixed duration.

This table presents a statistical comparison of the dynamic event slicing method (SpikeSlicer) and a fixed-duration slicing method. It shows the average number of event cells used, the variance in the number of cells, and the average, minimum, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and maximum durations of the sliced event segments for both methods. The comparison highlights the variability in segment lengths produced by the dynamic method compared to the consistent lengths of the fixed-duration method.

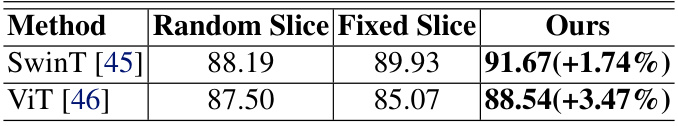

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the effectiveness of SpikeSlicer when used with different state-of-the-art recognition backbones, specifically SwinT and ViT. It compares the performance (accuracy) achieved using SpikeSlicer with two baseline methods: random slicing and fixed slicing. The improvement in accuracy obtained with SpikeSlicer is shown in parentheses for each backbone.

This table presents the quantitative comparison of using different slicing methods on the N-ImageNet dataset for object recognition. The results show the accuracy achieved using ResNet-18 for three different approaches: random slicing, fixed slicing, and the authors’ proposed adaptive slicing method (SpikeSlicer). SpikeSlicer demonstrates a significant performance improvement over the other two methods.

Full paper#