↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many kernel k-means methods overlook fairness, potentially leading to discriminatory results. This is especially problematic in applications involving human data, such as social network analysis or crime prediction, where unbiased clustering is crucial. Existing methods often lack mechanisms to guarantee fair clustering, resulting in uneven distribution of protected groups across clusters.

To address this, the paper introduces the Fair Kernel K-Means (FKKM) framework. FKKM incorporates a novel fairness regularization term into the kernel k-means objective function, allowing for direct optimization of fairness alongside clustering accuracy. This approach is extended to the multiple kernel setting (FMKKM), enhancing flexibility. The method’s effectiveness is rigorously validated through theoretical analysis and extensive experimentation, showcasing its superiority over existing methods in ensuring both fair and accurate clustering results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it tackles the crucial issue of fairness in kernel k-means clustering, a widely used machine learning technique. By proposing a novel Fair Kernel K-Means (FKKM) framework and extending it to multiple kernels, the research directly addresses the potential for discrimination inherent in existing methods. The provided theoretical analysis and easily applicable hyperparameter strategy makes FKKM readily usable, opening up new avenues for creating fairer and more equitable machine learning models across numerous applications.

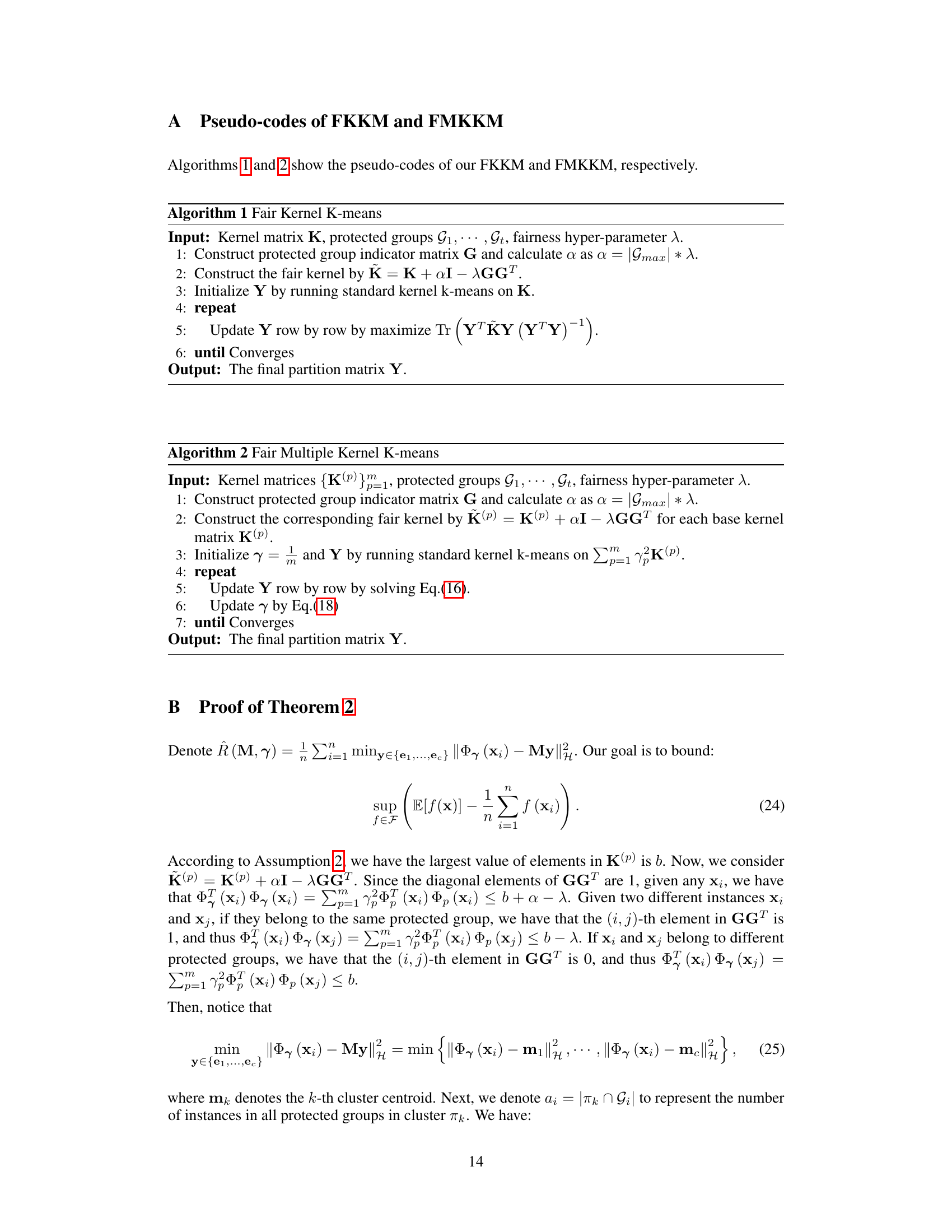

Visual Insights#

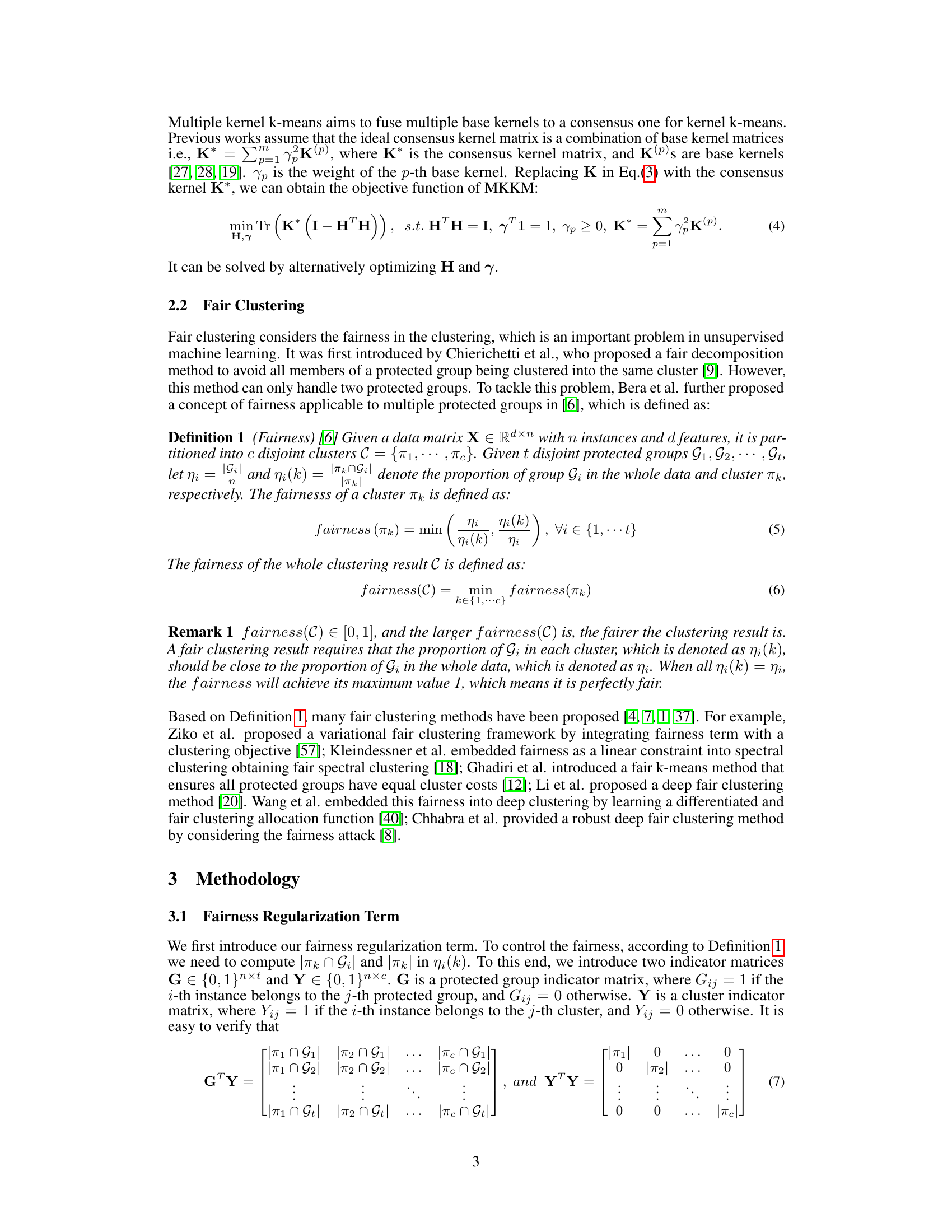

This figure visualizes the fairness of the FMKKM-f (Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means without fairness regularization) and FMKKM (Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means with fairness regularization) methods on the D&S dataset. It uses a 3D bar chart to show the number of instances from each protected group (Gj) that are assigned to each cluster (πi). The comparison between (a) and (b) demonstrates how the fairness regularization term in FMKKM leads to a more balanced distribution of protected groups across the clusters, indicating better fairness compared to FMKKM-f.

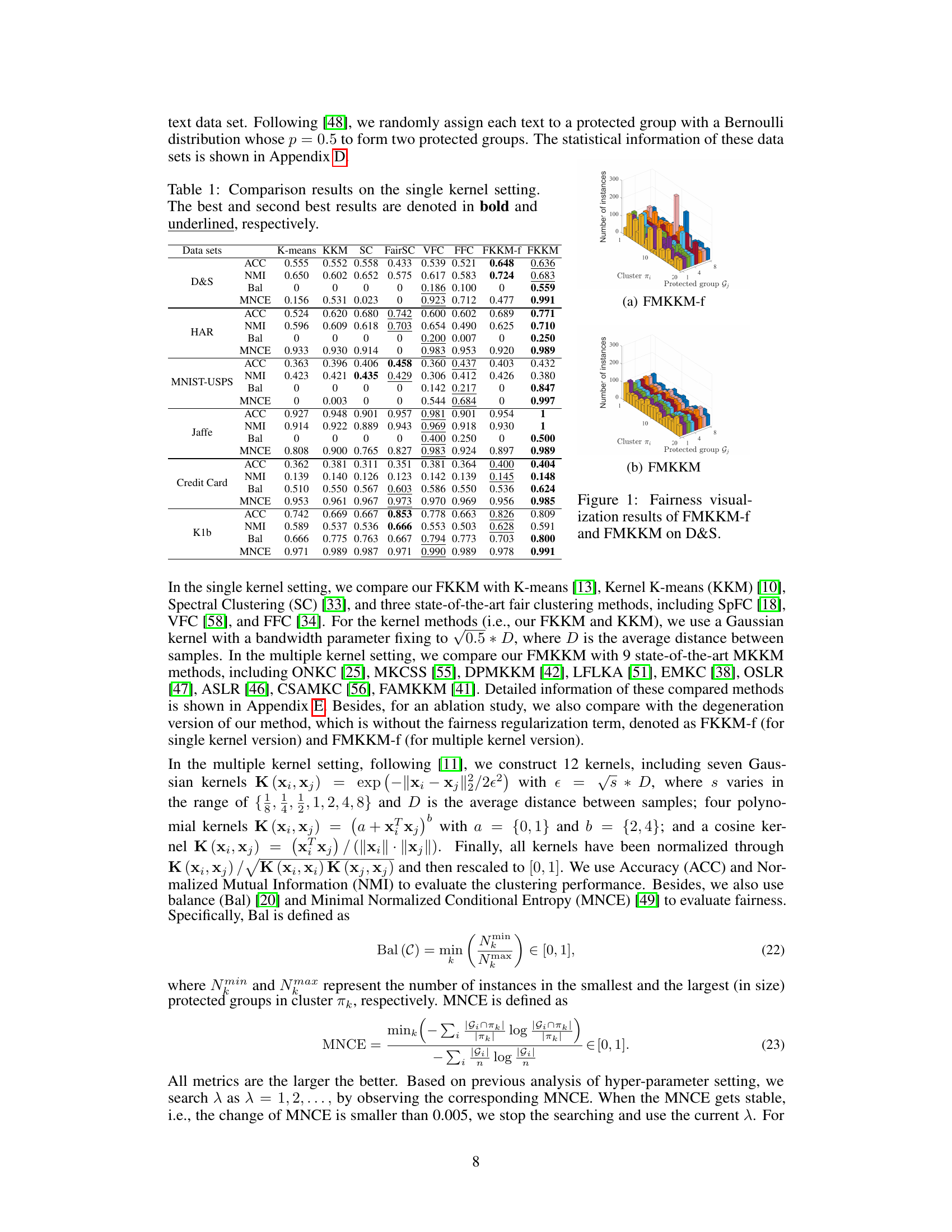

This table presents a comparison of different clustering methods on six datasets using a single kernel. The methods compared include K-means, Kernel K-Means (KKM), Spectral Clustering (SC), three state-of-the-art fair clustering methods (SpFC, VFC, FFC), and the proposed Fair Kernel K-Means (FKKM) and its ablation version (FKKM-f). The table shows the performance of each method in terms of accuracy (ACC), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), balance (Bal), and Minimal Normalized Conditional Entropy (MNCE). These metrics assess both the clustering accuracy and the fairness of the results. The best performing methods for each metric are highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Fair Clustering Intro#

Fair clustering, a subfield of machine learning, seeks to mitigate bias and discrimination in clustering algorithms. Traditional clustering methods often overlook fairness, leading to results where certain sensitive groups (e.g., racial, gender) are disproportionately represented in specific clusters. Fair clustering aims to address this by incorporating fairness constraints or metrics into the clustering process, ensuring a more equitable distribution of groups across clusters. This is particularly important in applications where clustering decisions have real-world consequences, such as loan applications, hiring processes, or social network analysis. Different notions of fairness exist, including individual fairness (similar individuals should be treated similarly) and group fairness (fair representation of groups in each cluster). The choice of fairness metric and its integration with the clustering algorithm is crucial and significantly influences the trade-off between fairness and clustering accuracy. Research in fair clustering actively explores novel algorithms and techniques to enhance fairness without sacrificing significant accuracy. Methodological challenges include the computational cost of incorporating fairness constraints and the potential conflict between different fairness metrics. Overall, fair clustering presents a significant advancement to improve the ethical implications of machine learning applications.

FKKM Framework#

The FKKM framework, designed for fair kernel k-means clustering, presents a novel approach to integrating fairness considerations directly into the kernel k-means algorithm. A key innovation is the introduction of a novel fairness regularization term. This term is carefully designed to have a form similar to the standard kernel k-means objective function, allowing for seamless integration without major modifications to the existing algorithm. The framework’s elegance lies in its simplicity; it essentially adjusts the input kernel to incorporate fairness, rather than significantly altering the optimization process itself. This design choice makes the FKKM framework easy to implement and computationally efficient. Furthermore, the framework extends naturally to multiple kernel settings, leading to the more general FMKKM method. Theoretical analysis provides a generalization error bound and guides hyper-parameter selection, contributing to ease of use. The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the FKKM framework, showing improvements in both clustering accuracy and fairness compared to existing methods. While this approach achieves promising results, future work could address limitations such as the reliance on pre-defined protected groups.

FMKKM Extension#

An ‘FMKKM Extension’ section in a research paper would likely detail how the Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means (FMKKM) algorithm, designed for fair data clustering, can be adapted or extended to handle more complex scenarios. This might involve handling imbalanced datasets, where certain groups are under-represented, or incorporating additional fairness constraints beyond those already considered by the algorithm. The extension could explore different kernel combinations or novel weighting strategies to improve the fairness and clustering accuracy, perhaps by adding regularization techniques to prevent overfitting or introducing dynamic kernel selection. Another aspect might be analyzing the algorithm’s robustness to noisy or incomplete data, or how well it generalizes to unseen data. Finally, the extension may provide an in-depth discussion of computational complexity and scalability improvements, comparing its performance with existing fair clustering algorithms. Empirical evaluations on diverse datasets would be essential to validate the claims of improved fairness and accuracy.

Generalization Bound#

A generalization bound in machine learning provides a theoretical guarantee on the performance of a model on unseen data based on its performance on training data. For clustering algorithms like the Fair Kernel K-Means (FKKM) presented in the paper, a generalization bound would offer insights into how well the learned cluster assignments generalize to new, unobserved data points. A tighter bound implies greater confidence in the model’s ability to perform well in real-world scenarios. The derivation of such a bound typically involves analyzing the complexity of the hypothesis space (the set of all possible clusterings) and the data distribution. Factors such as the number of clusters, the dimensionality of the data, and the type of kernel used would likely influence the bound’s tightness. Furthermore, given the paper’s focus on fairness, a generalization bound analysis could also reveal how fairness constraints affect the model’s generalization capability, helping us understand the trade-off between fairness and accuracy.

Future of Fairness#

The “Future of Fairness” in AI necessitates a multi-pronged approach. Algorithmic advancements are crucial, moving beyond simple demographic parity towards more nuanced fairness metrics that account for intersectionality and contextual factors. Explainable AI (XAI) will play a vital role in building trust and ensuring transparency in decision-making processes, allowing for identification and mitigation of biases. Data collection and preprocessing must be critically examined, focusing on representative datasets and bias-mitigating techniques. Beyond technical solutions, broader societal discussions are essential, engaging stakeholders to shape ethical guidelines and address potential societal impacts. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks and legal considerations need to evolve to keep pace with AI’s rapid development, establishing clear standards and accountability measures. Finally, a continuous monitoring and evaluation system is crucial to detect and address emerging biases, promoting ongoing fairness and equity improvements. Addressing the future of fairness necessitates a collective commitment from researchers, developers, policymakers, and the wider community.

More visual insights#

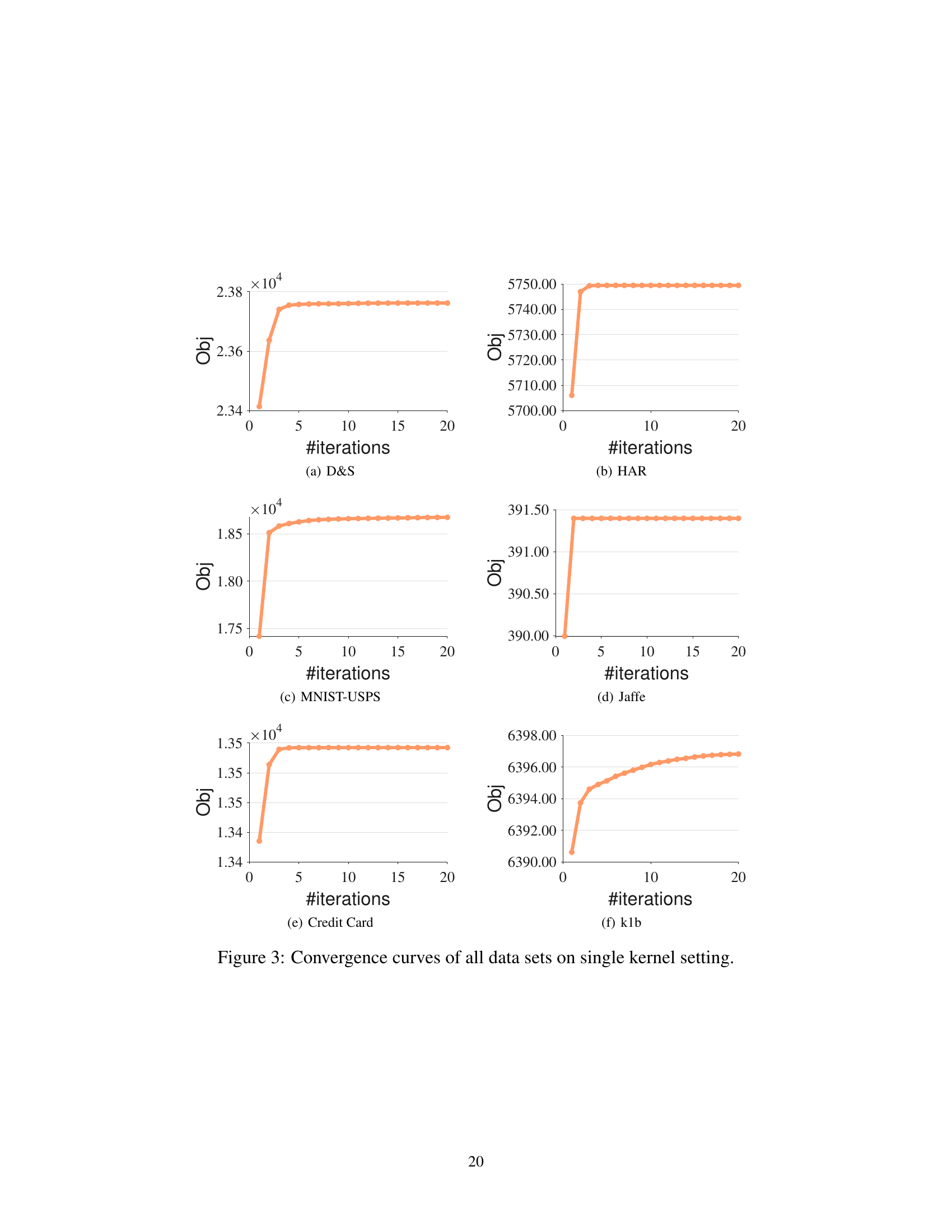

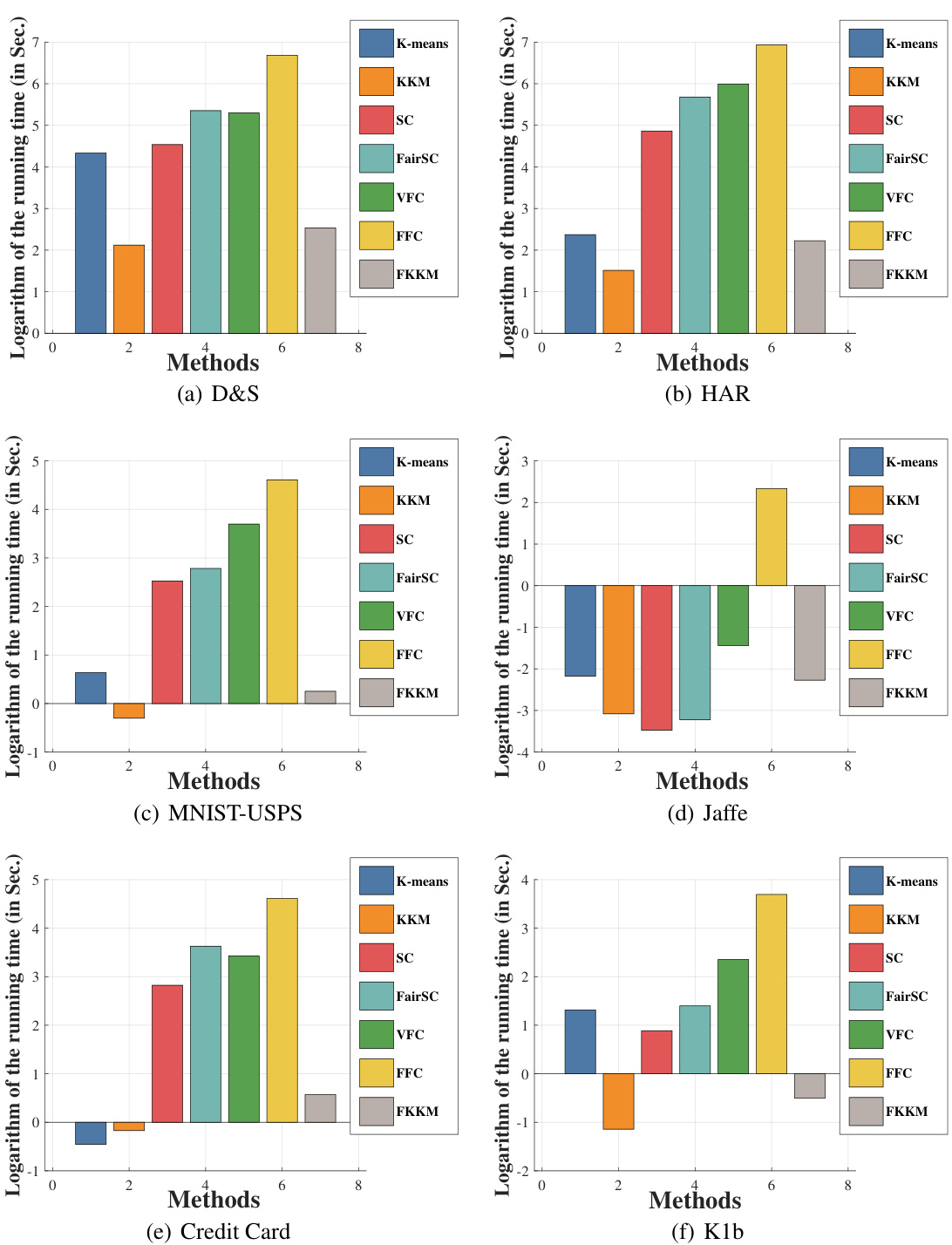

More on figures

This figure visualizes the fairness of the FMKKM-f (Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means without fairness regularization) and FMKKM (Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means with fairness regularization) methods on the D&S dataset. It shows the number of instances from each protected group within each cluster. The subfigures (a) and (b) show the distribution for FMKKM-f and FMKKM, respectively. The goal is to illustrate how FMKKM achieves better fairness by ensuring more balanced representation of protected groups across clusters compared to the unregularized FMKKM-f.

This figure visualizes the fairness achieved by the proposed methods (FMKKM and FMKKM-f) on the D&S dataset. It shows the number of instances from each protected group in each cluster. Panel (a) shows the results from the method without the fairness regularization term (FMKKM-f). Panel (b) shows the results from the full FMKKM method. The significant difference between (a) and (b) illustrates the effectiveness of the fairness regularization term in achieving more balanced cluster compositions across protected groups.

This figure visualizes the fairness results obtained by FMKKM-f (without fairness regularization) and FMKKM (with fairness regularization) on the D&S dataset. It shows the number of instances from each protected group within each cluster, illustrating the difference in fairness between the two methods. FMKKM demonstrates a more balanced distribution of protected groups across clusters, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed fairness regularization term.

This figure visualizes the fairness achieved by the proposed FMKKM and its variant without fairness regularization (FMKKM-f) on the D&S dataset. It shows the distribution of protected groups across different clusters. The comparison highlights the effectiveness of the fairness regularization term in achieving a more balanced distribution of protected groups within each cluster, demonstrating improved fairness compared to the method without fairness constraints.

This figure visualizes the fairness achieved by the proposed FMKKM and its variant without the fairness regularization term (FMKKM-f). It shows the distribution of protected groups within each cluster. The x-axis represents the cluster ID, and the y-axis represents the number of instances. Different colors indicate different protected groups. FMKKM aims for a more balanced distribution across clusters, reflecting improved fairness compared to FMKKM-f, which shows a less even distribution indicating potential unfairness.

More on tables

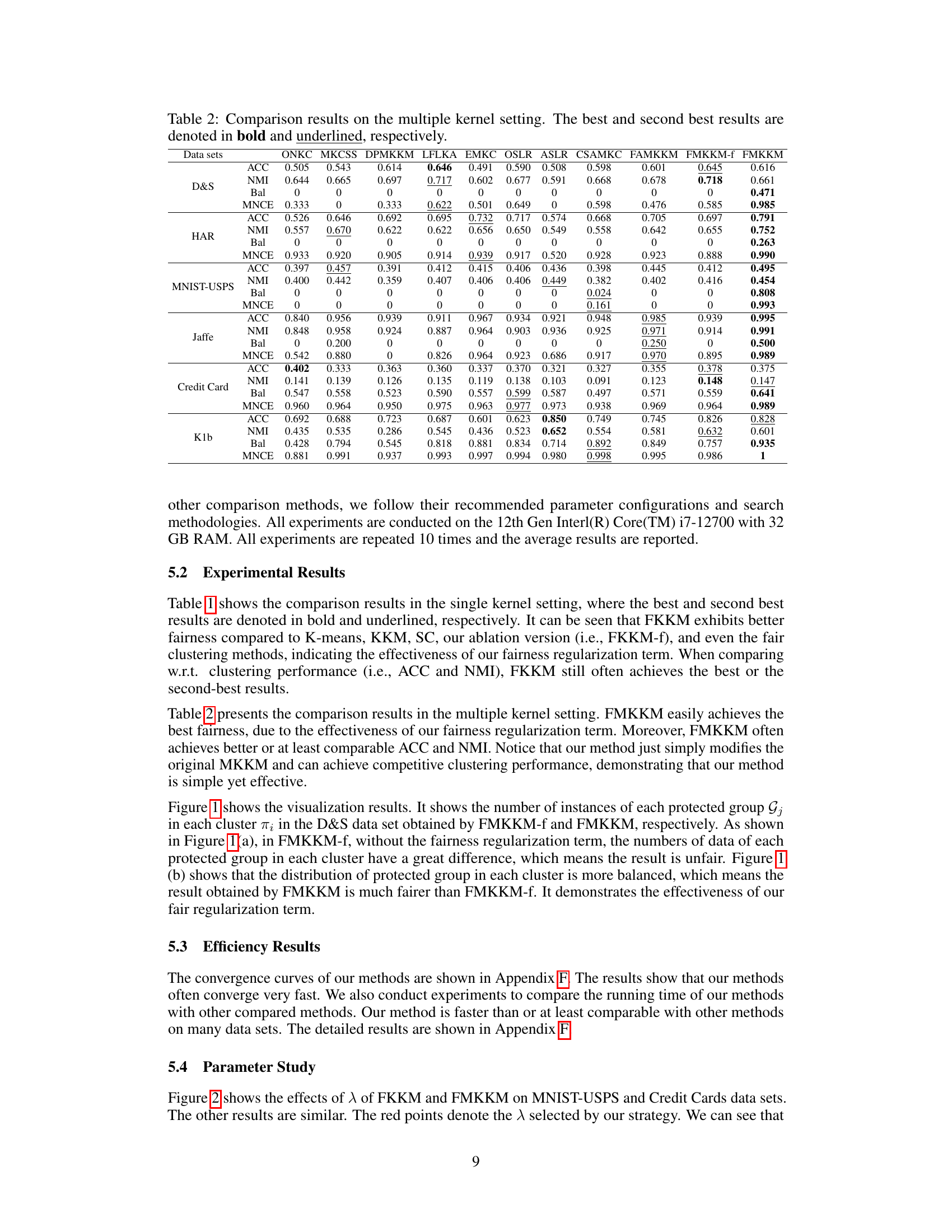

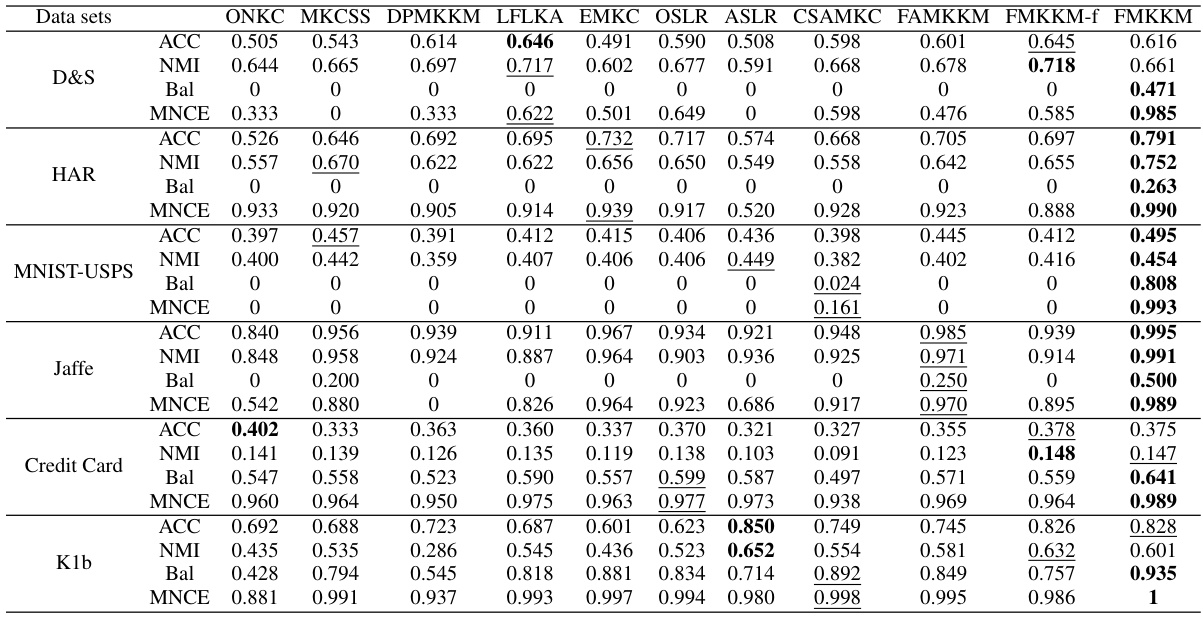

This table presents the comparison results of the proposed Fair Multiple Kernel K-Means (FMKKM) method against nine state-of-the-art Multiple Kernel K-Means (MKKM) methods across six benchmark datasets. The performance is evaluated using four metrics: Accuracy (ACC), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), Balance (Bal), and Minimal Normalized Conditional Entropy (MNCE). The best and second-best results for each dataset and metric are highlighted.

This table presents a comparison of different clustering methods on various datasets using a single kernel. The methods compared include standard K-means, Kernel K-means (KKM), Spectral Clustering (SC), three state-of-the-art fair clustering methods (SpFC, VFC, FFC), and the proposed Fair Kernel K-means (FKKM) and its ablation version (FKKM-f). The evaluation metrics used are Accuracy (ACC), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), Balance (Bal), and Minimal Normalized Conditional Entropy (MNCE). The table shows the performance of each method in terms of both clustering accuracy and fairness.

This table presents a comparison of different clustering methods’ performance on several datasets in a single-kernel setting. The methods compared include K-means, Kernel K-means (KKM), Spectral Clustering (SC), three state-of-the-art fair clustering methods (SpFC, VFC, FFC), and the proposed Fair Kernel K-Means (FKKM) and its fair-agnostic counterpart (FKKM-f). The evaluation metrics used are Accuracy (ACC), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), Balance (Bal), and Minimal Normalized Conditional Entropy (MNCE). Higher ACC and NMI values are preferred, while higher Bal and MNCE indicate better fairness.

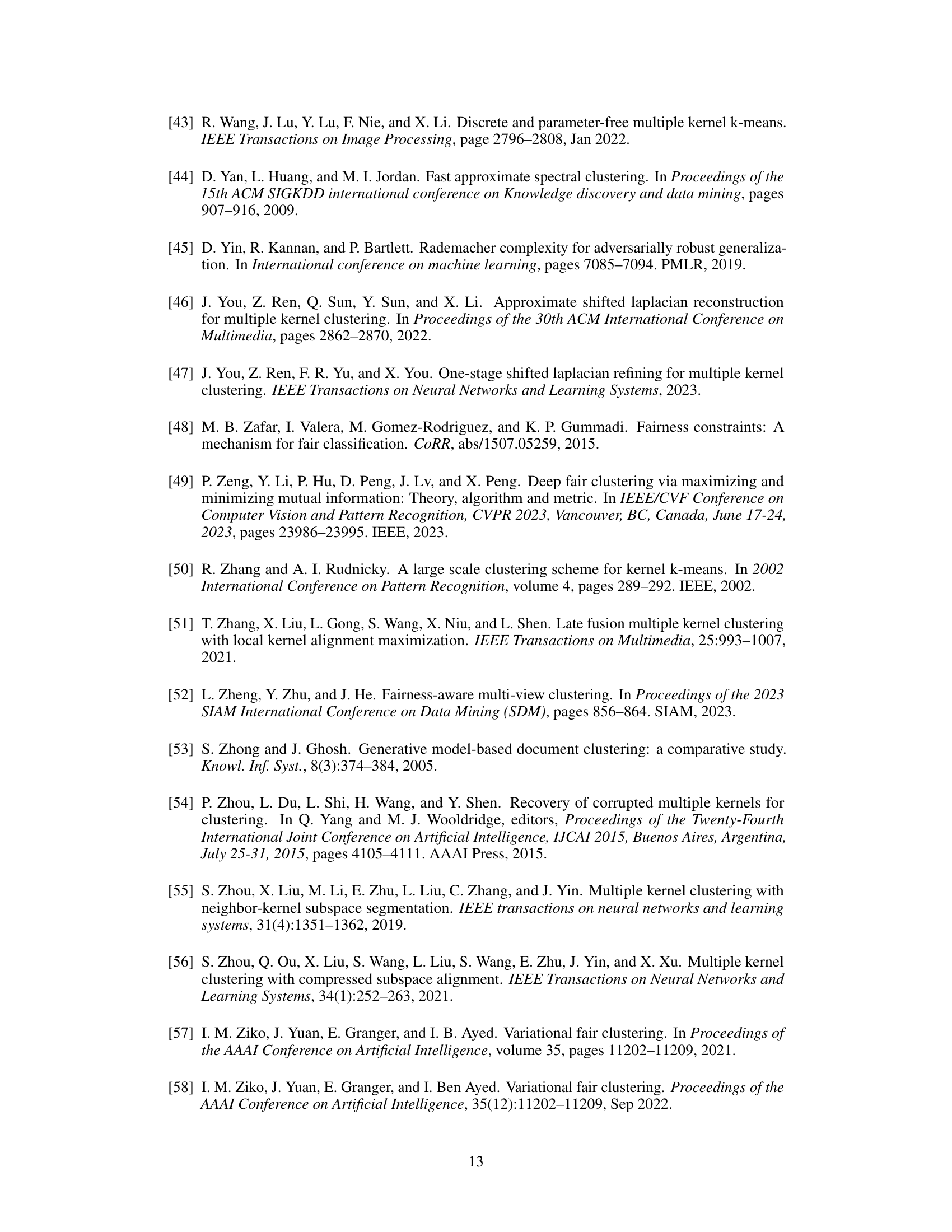

Full paper#