↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current vision-language-action (VLA) models for instruction-following agents struggle with open-world environments due to challenges in handling complex, context-dependent tasks and long-term interactions. Prior methods either rely on separate controllers for action execution or directly output commands, both of which have limitations.

OmniJARVIS tackles these issues by introducing a unified tokenization scheme for multimodal interaction data. This allows the model to jointly process vision, language, and action information, facilitating more robust reasoning, planning, and execution. The key innovation lies in the self-supervised behavior tokenizer, which discretizes behavior trajectories into semantically meaningful tokens integrated into a pretrained multimodal language model. This approach leads to improved performance on a wide range of Minecraft tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to building open-world instruction-following agents, addressing limitations of existing methods. The unified tokenization of multimodal interaction data, enabling strong reasoning and efficient decision-making, is a significant advancement. This work is highly relevant to current trends in embodied AI and opens up new avenues for research in unified multimodal learning and long-term planning.

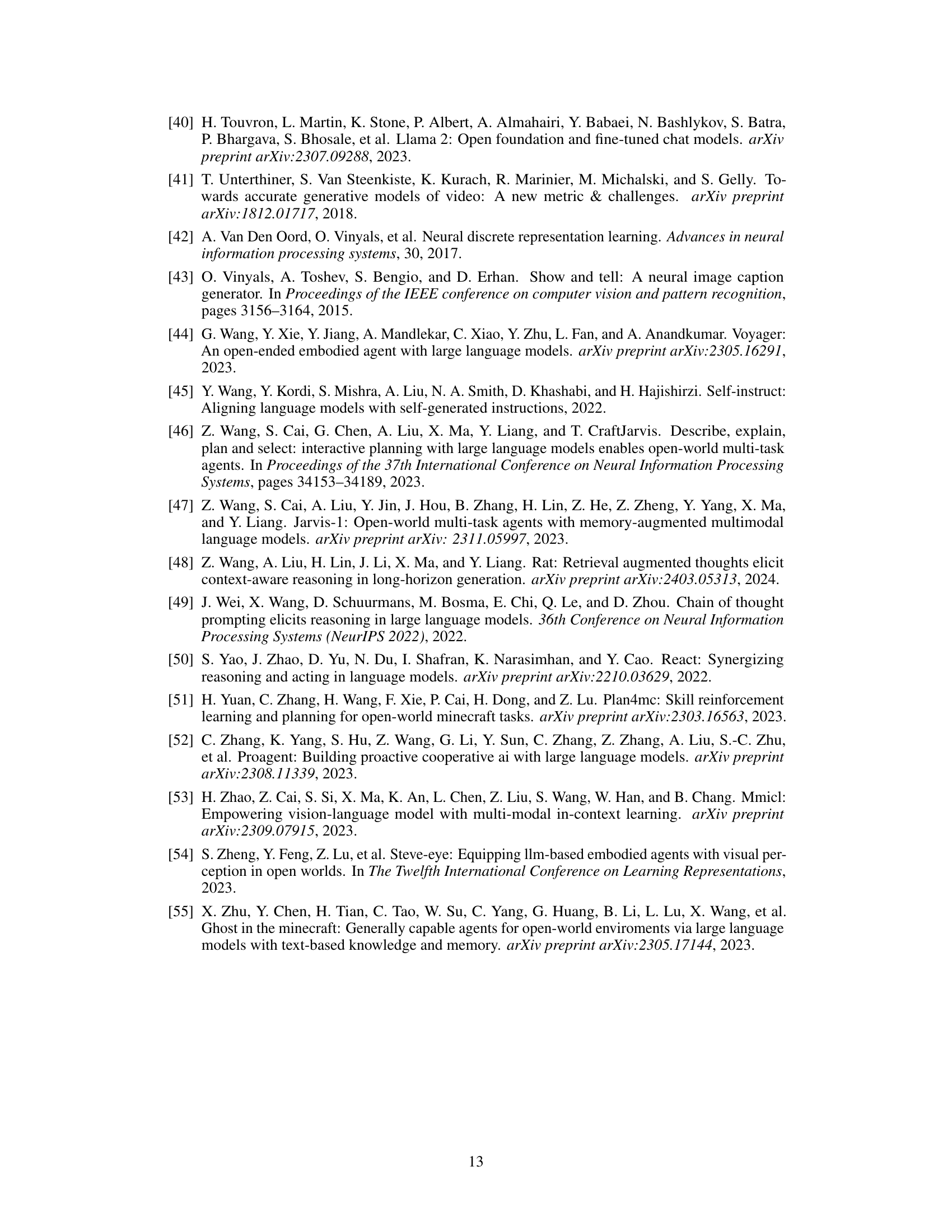

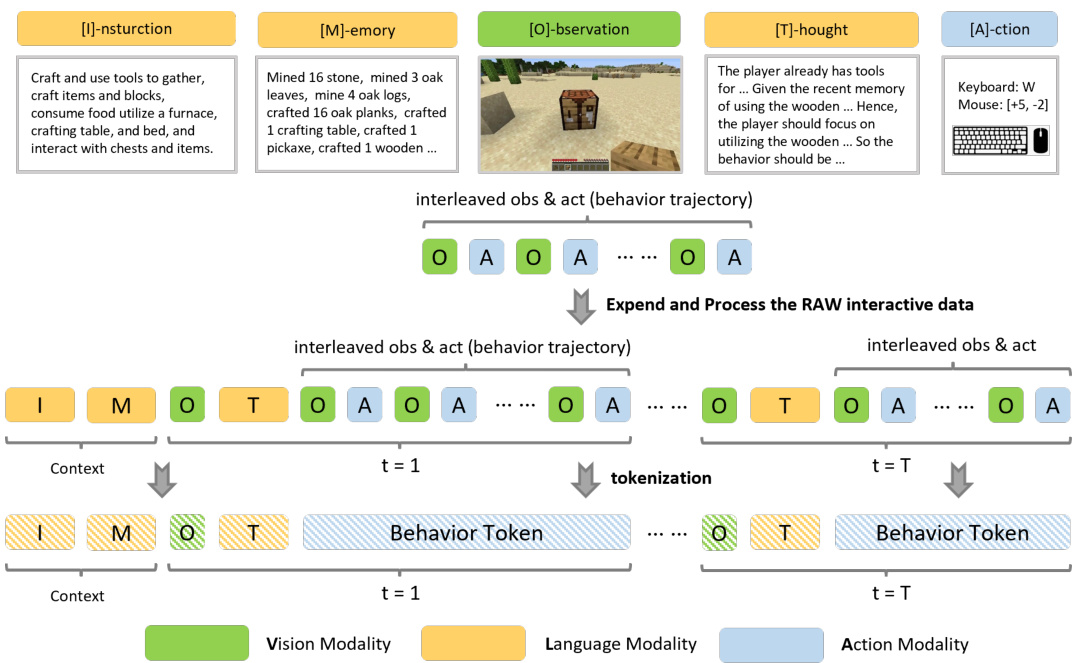

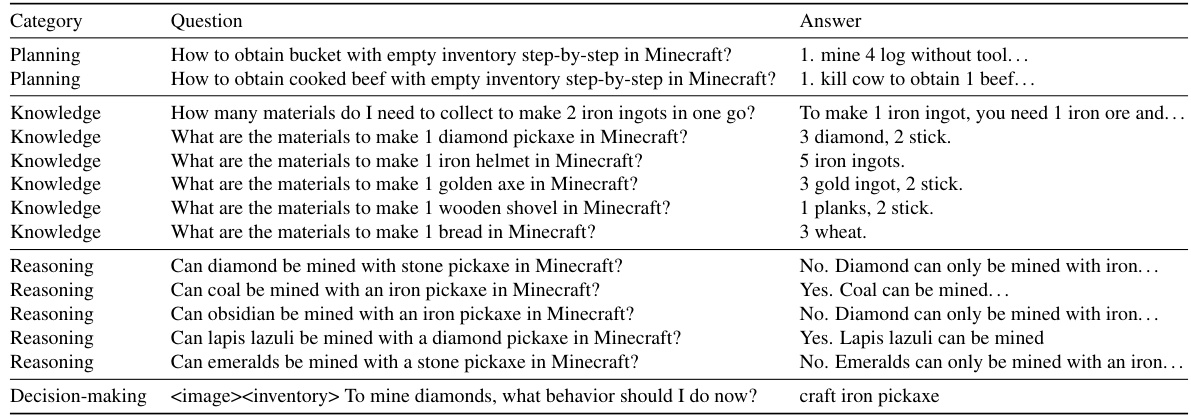

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the multimodal interaction data used for decision-making in the OmniJARVIS model. It shows a sequence of human interaction steps, starting with an instruction and memory, progressing through observations, chain-of-thought reasoning, and finally resulting in a behavior trajectory. The OmniJARVIS model uniquely unifies these different modalities (vision, language, action) into a single autoregressive sequence for prediction. A key component is a self-supervised behavior encoder that converts actions into discrete behavior tokens, which are then incorporated into the overall sequence.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of multi-modal interaction data for decision-making. A canonical interaction sequence depicting the human decision-making process starts from a given task instruction and memory, followed by a series of sub-task completion which involves initial observations, chain-of-thought reasoning, and behavior trajectories. Our proposed VLA model OmniJARVIS jointly models the vision (observations), language (instructions, memories, thoughts), and actions (behavior trajectories) as unified autoregressive sequence prediction. A self-supervised behavior encoder (detailed in Section 2 and Figure 2) converts the actions into behavior tokens while the other modalities are tokenized following the practices of MLMs [31, 3, 1].

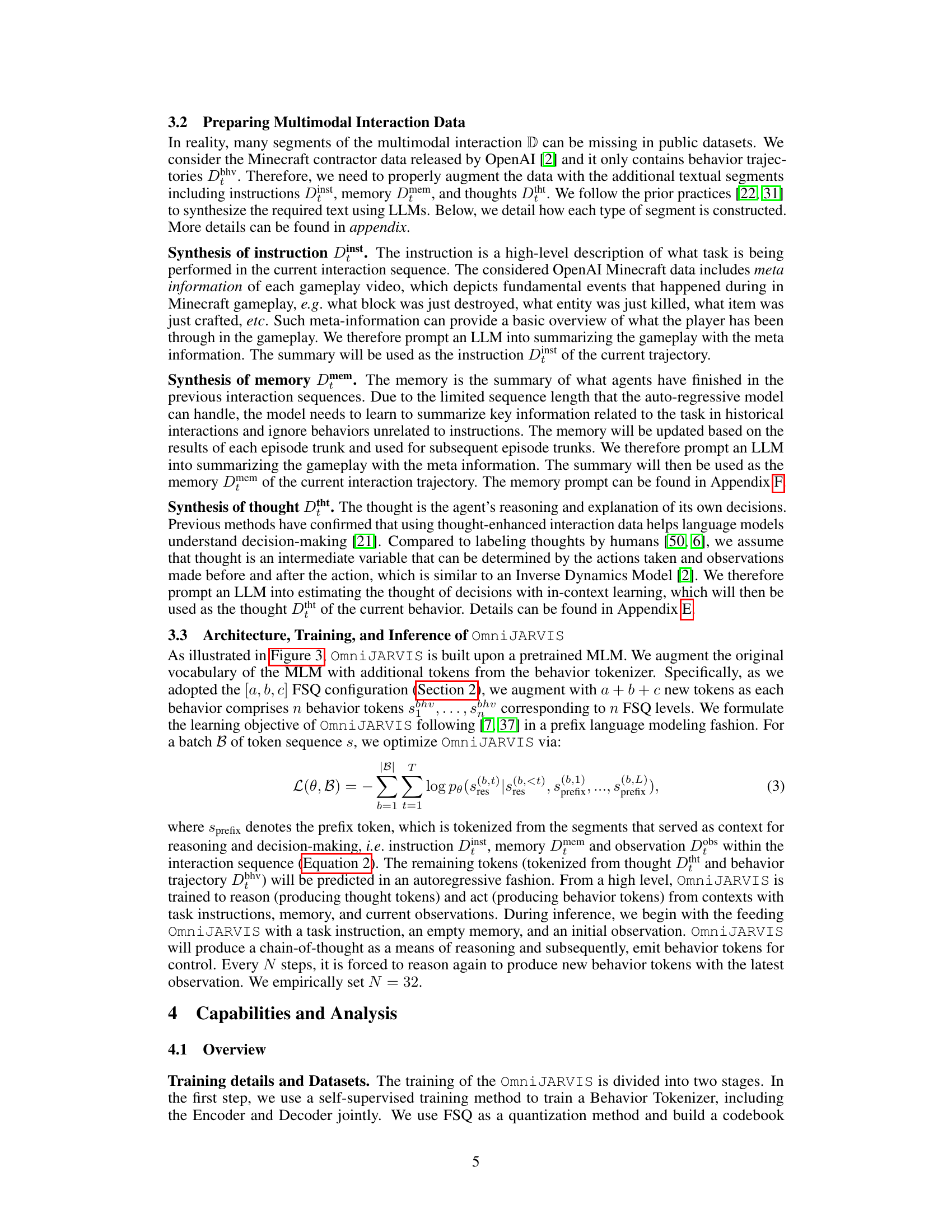

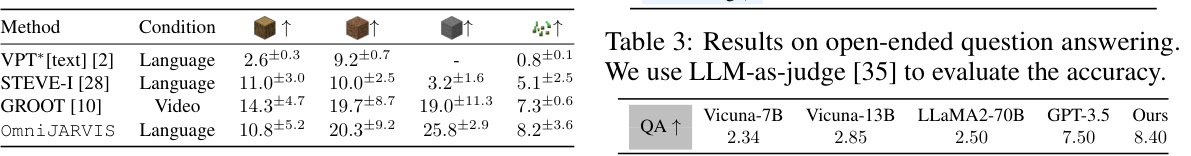

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different agents on four simple Minecraft tasks: chopping trees, mining stones, digging dirt, and collecting wheat seeds. The ‘rewards’ represent the success of each agent in completing these tasks. The table includes results for text-conditioned VPT, STEVE-I, GROOT, and OmniJARVIS, indicating their performance in completing the tasks based on the type of conditioning (language or video) used during training.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation results (rewards) on short-horizon atom tasks. The text-conditioned VPT [2] ('VPT (text)*') is from Appendix I of its paper.

In-depth insights#

Unified VLA Tokenization#

The concept of “Unified VLA Tokenization” centers on representing vision, language, and action data within a single, unified token space. This approach offers several key advantages. First, it facilitates more effective multimodal reasoning by allowing a model to directly relate observations, instructions, and actions. Second, unified tokenization enables the use of powerful autoregressive transformer models, which excel at processing sequential data and capturing long-range dependencies between different modalities. This is crucial for complex, open-world tasks where decisions depend on a history of interactions. Third, unified tokenization simplifies model architecture, avoiding the need for complex interfaces between separate vision, language, and action processing modules. This leads to improved efficiency in training and inference. Finally, this approach offers potential for better generalization, since the model learns to integrate information from all modalities seamlessly. However, challenges remain in developing effective tokenization schemes that capture the nuances of multimodal data, and sufficient training data is crucial to realize the potential of this approach.

Behavior Token Design#

Effective behavior tokenization is crucial for bridging the gap between high-level reasoning and low-level actions in embodied agents. A well-designed tokenization scheme should capture the semantic essence of action trajectories, allowing the model to understand not just individual actions, but also their temporal relationships and overall intent. This requires careful consideration of various factors, including granularity, which determines the level of detail encoded in each token; vocabulary size, balancing expressiveness with computational feasibility; and training methodology, employing techniques like self-supervised learning or reinforcement learning to efficiently learn meaningful token representations. Choosing an appropriate encoding method (e.g., one-hot encoding, vector quantization) is essential. It’s also vital to ensure the tokens are compatible with other modalities (e.g., vision and language) within the unified multimodal model, enabling seamless integration and information flow across different representations. Finally, a robust evaluation methodology is necessary to assess the effectiveness of the token design in improving the agent’s performance across various tasks and environments. Ideally, the design should be scalable and adaptable to diverse tasks and complexities, ensuring the system can handle increasingly challenging and diverse real-world scenarios.

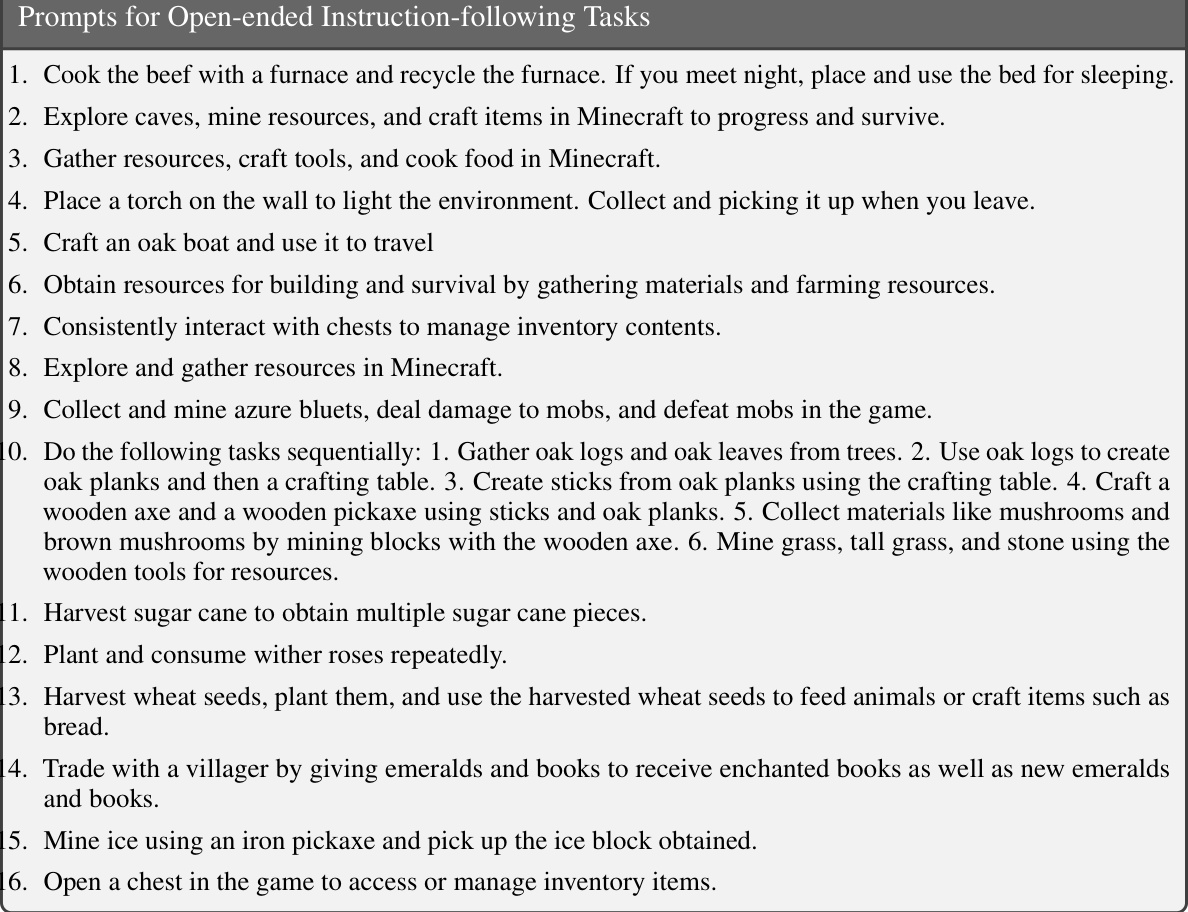

Minecraft Experiments#

A hypothetical section on “Minecraft Experiments” within a research paper would likely detail the use of the Minecraft game environment for evaluating an AI agent’s capabilities. The experiments would need to be carefully designed to test specific aspects of the agent, such as navigation, resource management, tool use, and problem-solving. A well-designed experimental setup might involve a series of increasingly complex tasks within Minecraft, starting with simple instructions and gradually progressing to more open-ended challenges. The metrics for evaluating performance would be crucial, and these could include task completion success rates, efficiency (time to completion), resource utilization, and the robustness of the agent’s actions. Control groups or baselines (e.g., other AI agents or human players) would be essential for demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed approach. The challenges of using Minecraft as an experimental platform would also warrant discussion, including the inherent variability of the game environment and the computational cost of simulating Minecraft. Finally, a thorough analysis of the results, identifying both strengths and limitations of the AI agent, would be vital for drawing valuable insights and guiding future research. Qualitative data analysis of the agent’s decision-making processes could complement quantitative results.

Open-World Challenges#

Open-world environments present significant challenges for AI agents due to their unpredictability and complexity. Unlike controlled lab settings, open worlds lack predefined rules, goals, and interactions. Agents must handle unexpected events, dynamic situations, and incomplete information. Robustness becomes paramount; agents must be able to adapt to unforeseen circumstances, recover from failures, and make effective decisions with limited knowledge. This requires advanced reasoning capabilities, including planning, learning, and adaptation, often within a multi-modal context (integrating vision, language, and action). Furthermore, generalization is critical; an effective open-world agent should be capable of performing a wide range of tasks across diverse environments and situations, without extensive retraining for each new scenario. Addressing these challenges requires breakthroughs in several areas, such as representation learning, reinforcement learning, and knowledge transfer, to build truly adaptable and intelligent agents.

Future Scale Potential#

The “Future Scale Potential” of large language models (LLMs) for vision-language-action (VLA) tasks, like those explored in OmniJARVIS, is significant but multifaceted. Scaling up both model size and dataset size is crucial, as demonstrated by the consistent performance improvements observed with larger models and more data. However, diminishing returns may become apparent at a certain point. The relationship between model scale and performance is not always linear; careful consideration of the cost-benefit ratio is needed. While simply increasing model parameters can be effective, research into more efficient model architectures is necessary to continue improving performance and generalization without exponential resource growth. Furthermore, the quality of interaction data is critical. More sophisticated data collection and augmentation techniques could unlock further improvements, particularly for open-world scenarios. Finally, exploring transfer learning across different tasks and environments could reduce the need for extensive, task-specific training, maximizing scalability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

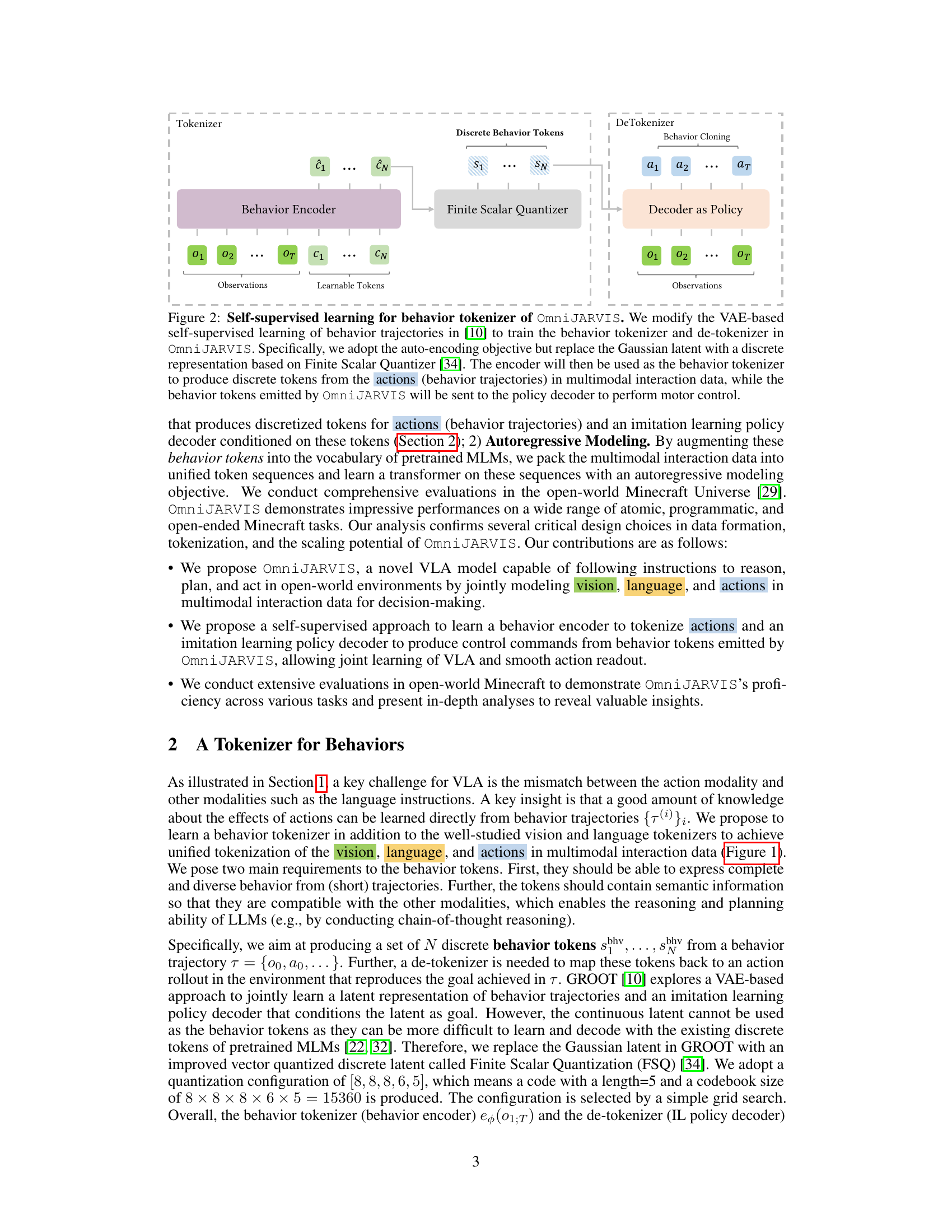

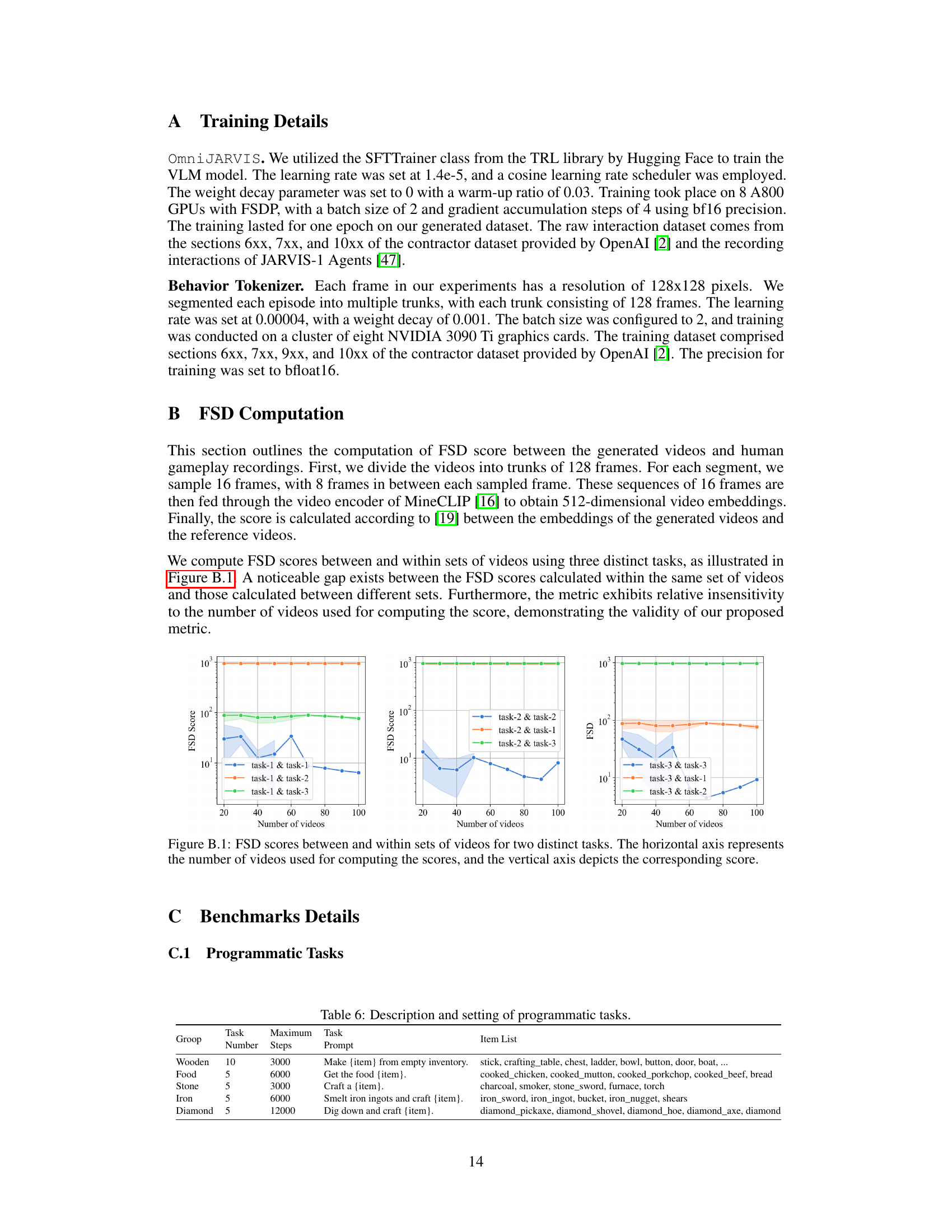

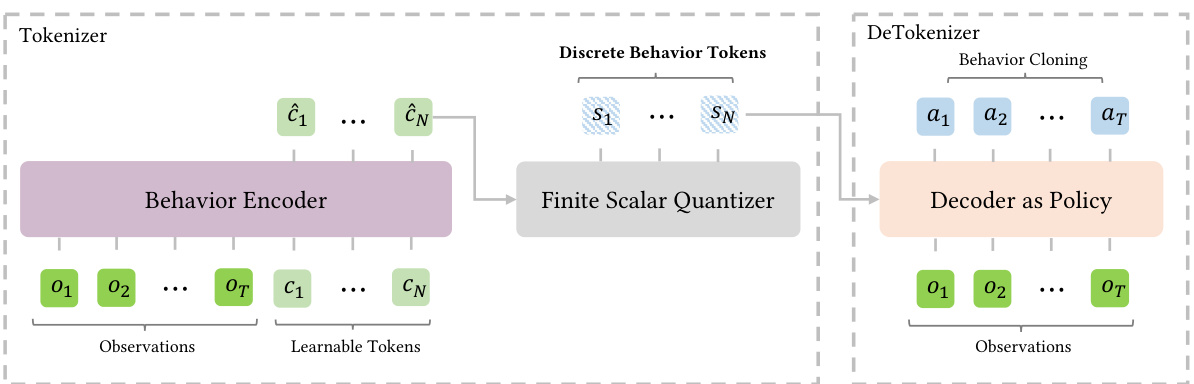

🔼 This figure illustrates the self-supervised learning process for the behavior tokenizer in OmniJARVIS. It adapts a VAE-based approach, replacing the continuous Gaussian latent representation with a discrete representation using Finite Scalar Quantizer. The encoder part of this autoencoder functions as the behavior tokenizer, converting action trajectories into discrete behavior tokens. These tokens are then used by a policy decoder (the decoder part of the autoencoder) for motor control, creating a closed loop for behavior modeling.

read the caption

Figure 2: Self-supervised learning for behavior tokenizer of OmniJARVIS. We modify the VAE-based self-supervised learning of behavior trajectories in [10] to train the behavior tokenizer and de-tokenizer in Omni JARVIS. Specifically, we adopt the auto-encoding objective but replace the Gaussian latent with a discrete representation based on Finite Scalar Quantizer [34]. The encoder will then be used as the behavior tokenizer to produce discrete tokens from the actions (behavior trajectories) in multimodal interaction data, while the behavior tokens emitted by OmniJARVIS will be sent to the policy decoder to perform motor control.

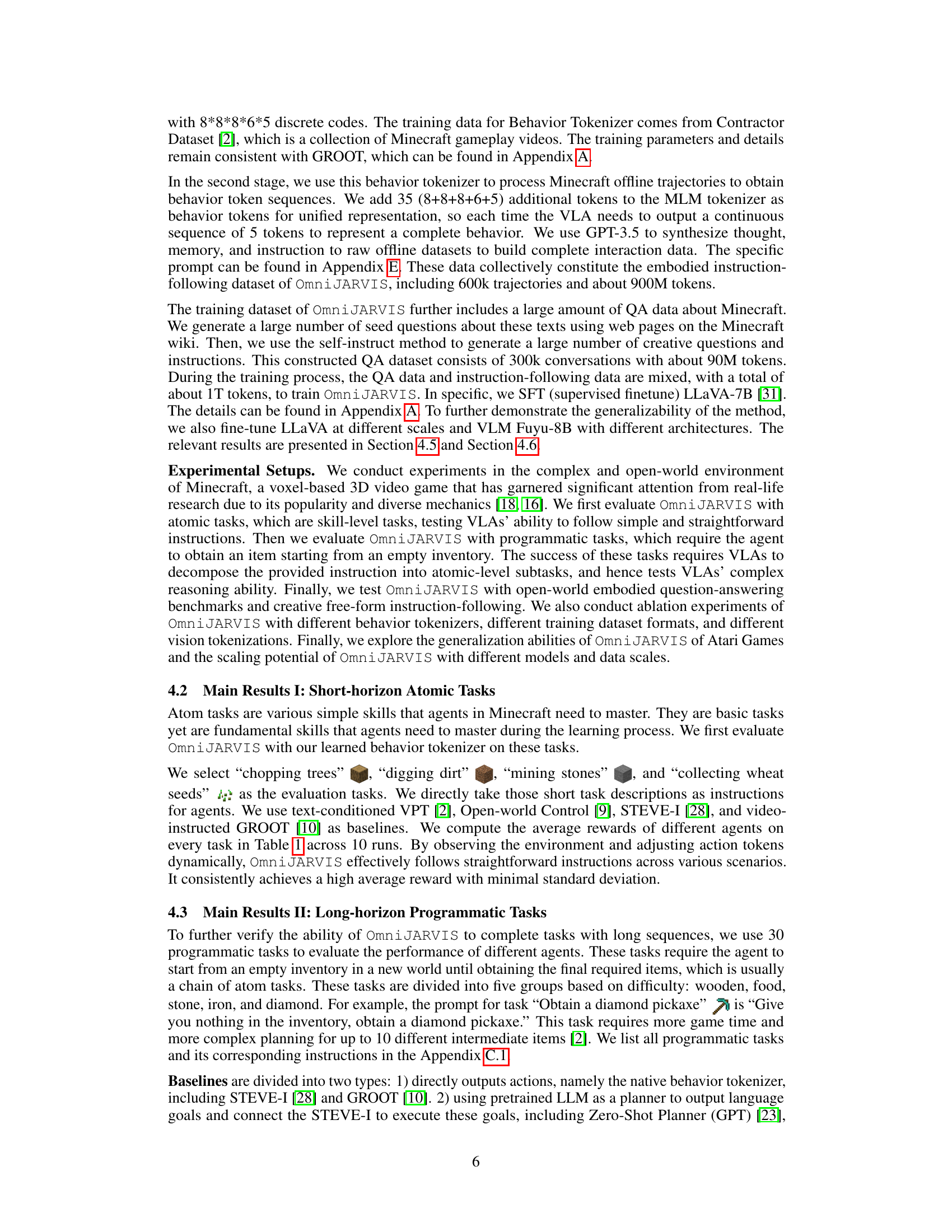

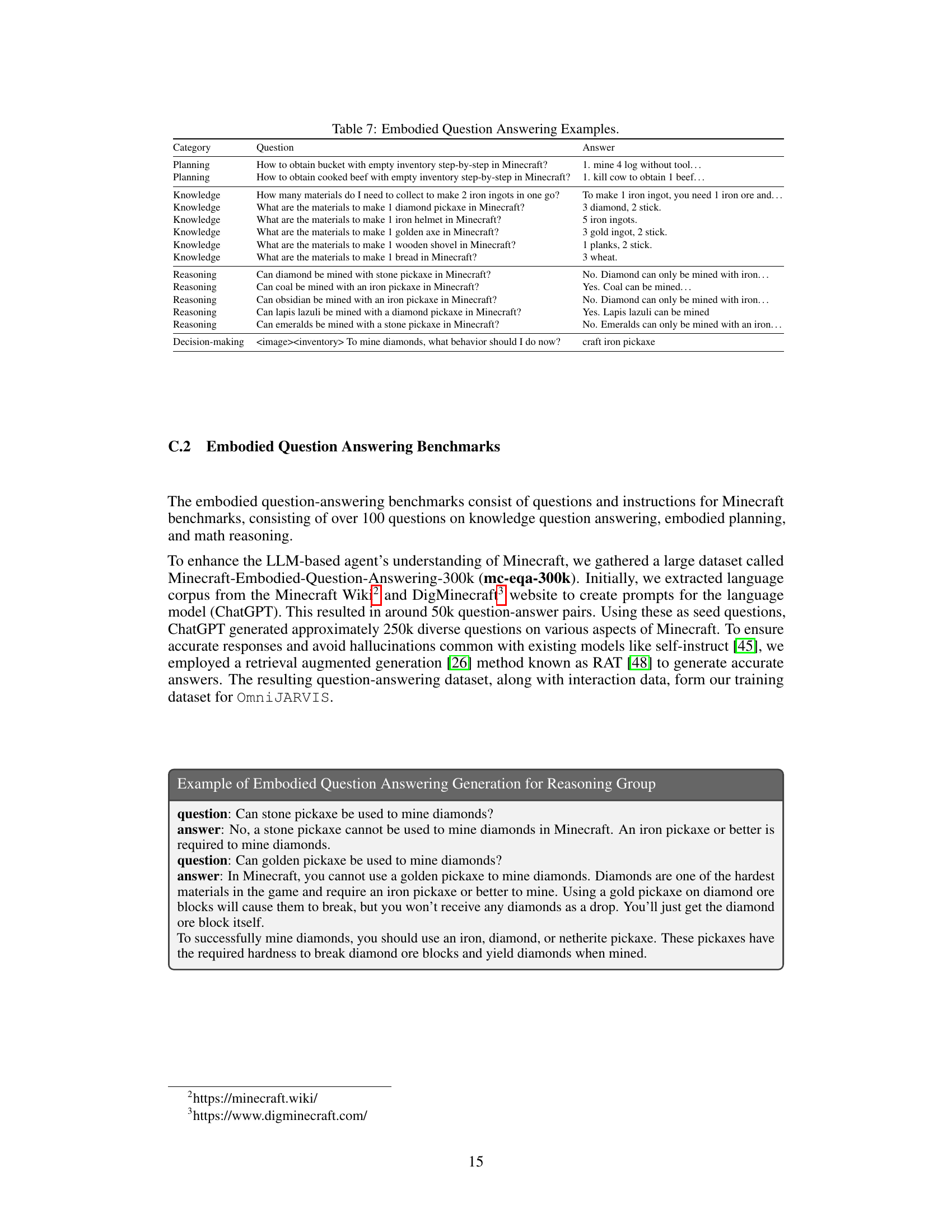

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture and inference process of OmniJARVIS. OmniJARVIS uses a multimodal language model (MLM) enhanced with behavior tokens. Starting with a task instruction, memory, and observation, it iteratively reasons using chain-of-thought and generates behavior tokens (actions) via a decoder policy. Every 128 steps, it updates its reasoning with the latest observations. It can also produce textual responses, such as answers to questions. The figure highlights the iterative decision-making process.

read the caption

Figure 3: Architecture and Inference of OmniJARVIS. The main body of OmniJARVIS is a multimodal language model (MLM) augmented with additional behavior tokens. Given a task instruction, initial memory, and observation, OmniJARVIS will iteratively perform chain-of-thought reasoning and produce behavior tokens as a means of control via the decoder policy (behavior de-tokenizer). Every 128 steps, OmniJARVIS is forced to reason again and produce new behavior tokens with the latest observation. (Not shown above) OmniJARVIS can also make textual responses, e.g. answering questions.

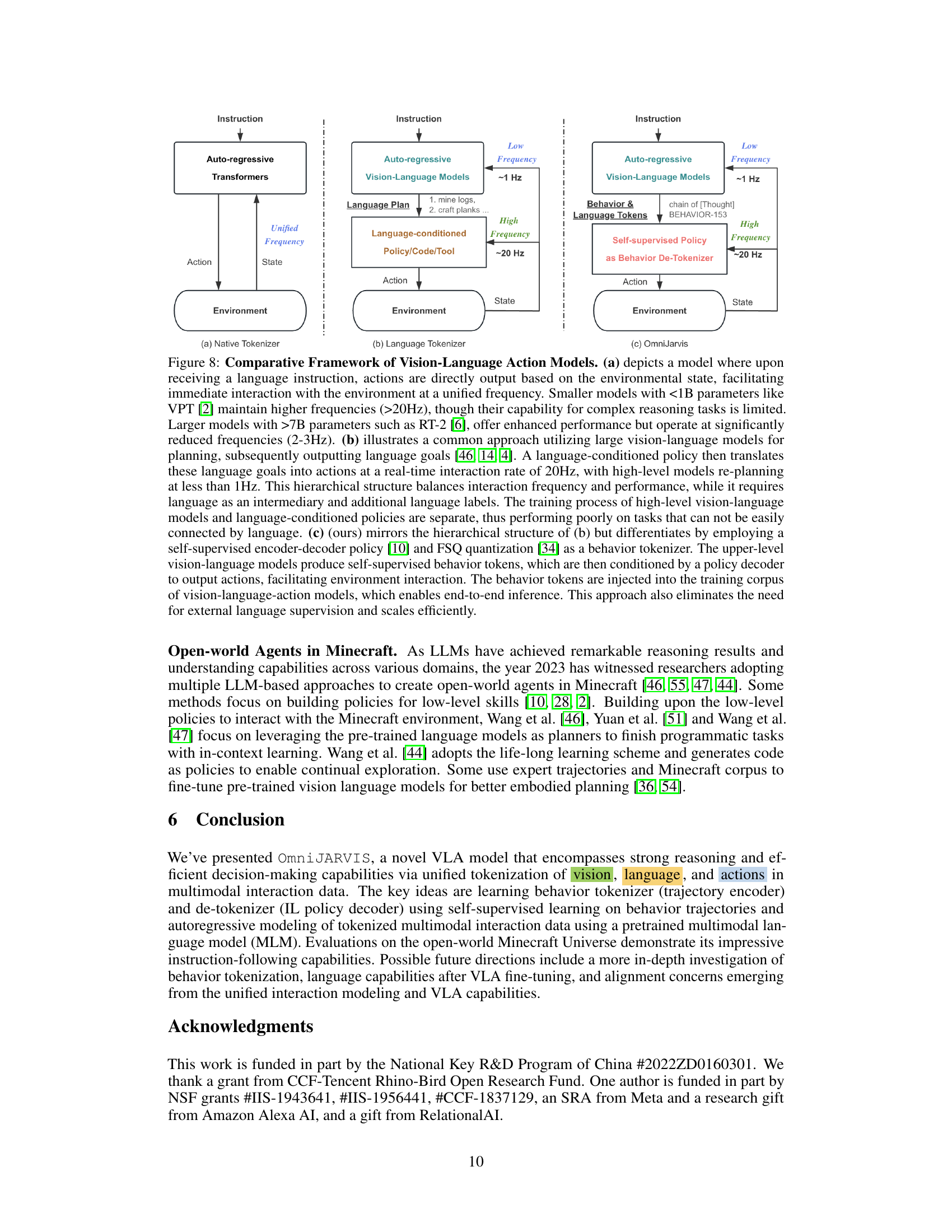

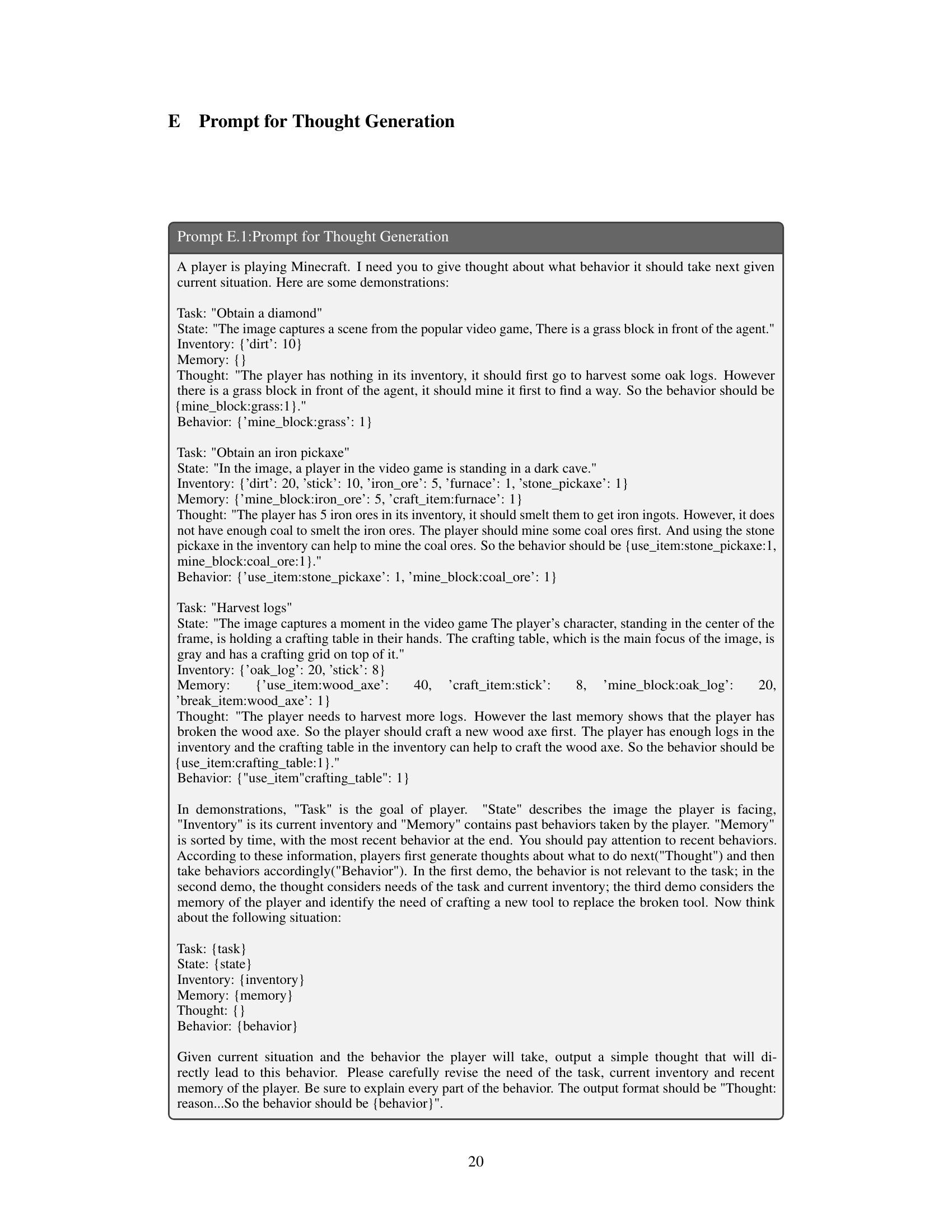

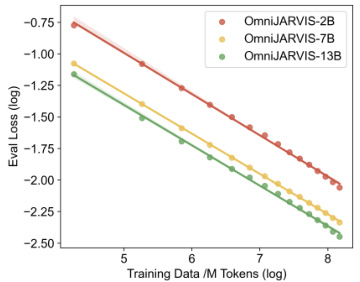

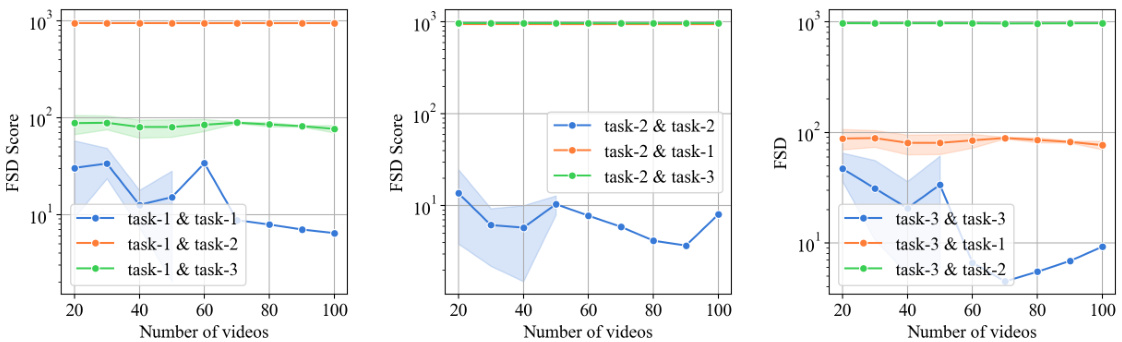

🔼 This figure shows the scaling potential of the OmniJARVIS model. The evaluation loss is plotted against the amount of training data (in millions of tokens) on a logarithmic scale. Three different model sizes (2B, 7B, and 13B parameters) are shown. As expected, the loss decreases as the amount of training data increases for all model sizes. The near-linear relationship in the log-log plot indicates that OmniJARVIS follows a power law scaling behavior, a characteristic observed in many large language models. The Pearson correlation coefficients close to 1 confirm a strong relationship between training data size and performance for each model, with larger models showing slightly slower improvements.

read the caption

Figure 5: Scaling potential of OmniJARVIS. Its evaluation loss continues to drop with the growth of data and model parameters. The Pearson coefficients for the 2B, 7B, and 13B models are 0.9991, 0.9999, and 0.9989.

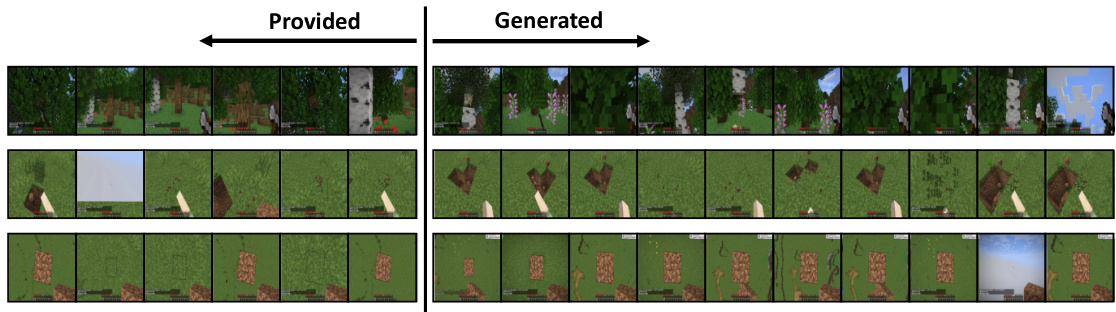

🔼 This figure shows examples of the behavior tokenization and detokenization process. The left side displays a reference video fed into the behavior tokenizer (encoder) which uses Finite Scalar Quantization (FSQ). The right side presents the video generated by the policy decoder (which is also an imitation learning policy decoder) using the behavior tokens generated by the encoder as conditioning. The figure demonstrates that the policy decoder can successfully replicate the task shown in the reference video by using the discrete behavior tokens.

read the caption

Figure 6: Examples of behavior tokenization-detokeinzation. Left: the reference video to be tokenized by our FSQ-based behavior tokenizer (encoder). Right: the behavior of the policy decoder is conditioned on the behavior tokens. The policy decoder can reproduce the task being accomplished in the reference video.

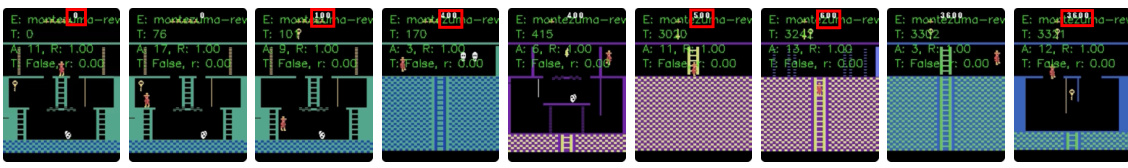

🔼 This figure shows a sequence of game frames from the Atari game Montezuma’s Revenge, showcasing the agent’s performance. The agent successfully navigates the game environment, achieving a final reward of 3600. Each frame is labeled with timestamps and other relevant metrics. The figure demonstrates the ability of the OmniJARVIS model to generalize beyond Minecraft environments and perform complex tasks in a different game.

read the caption

Figure 7: OmniJARVIS plays Montezuma's Revenge and gets a reward of 3600.

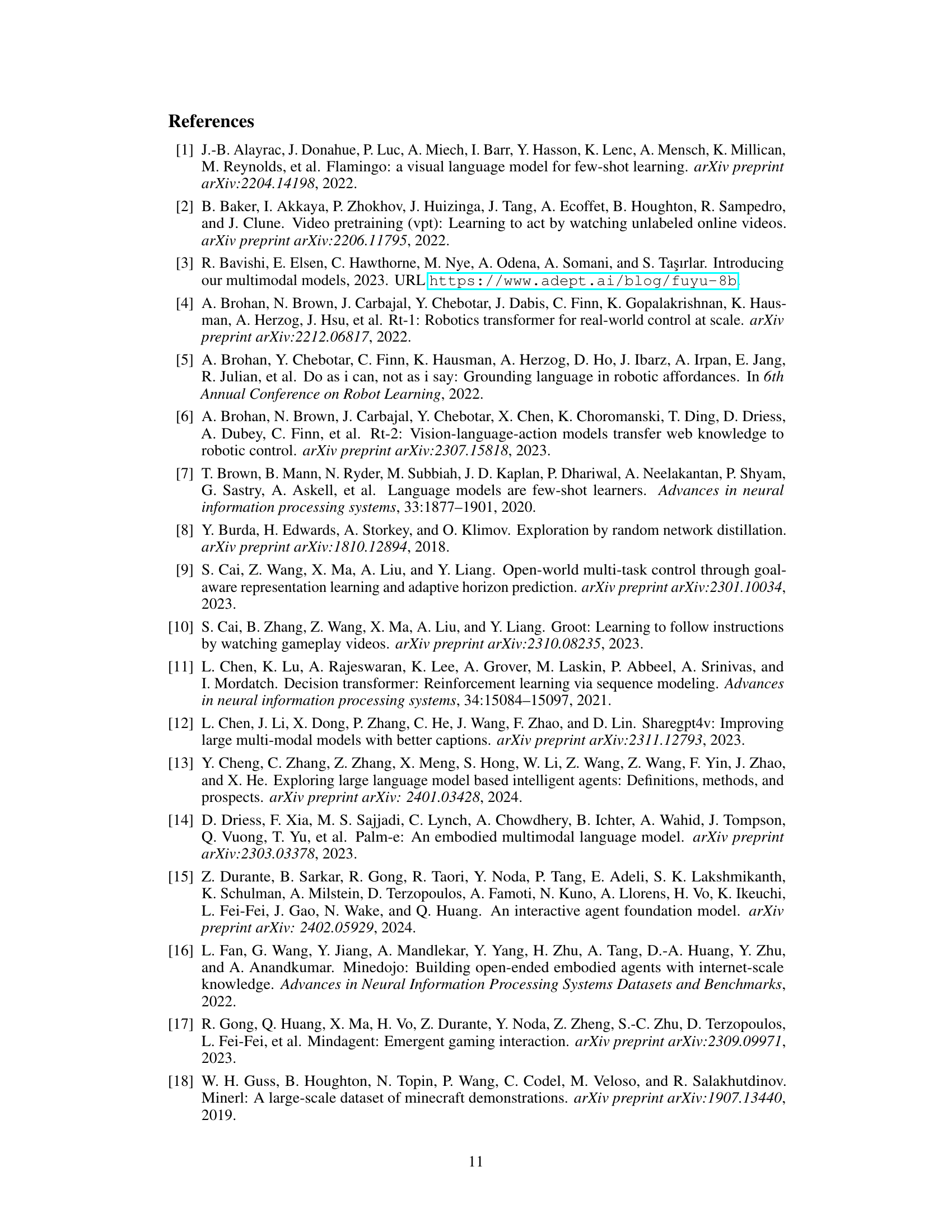

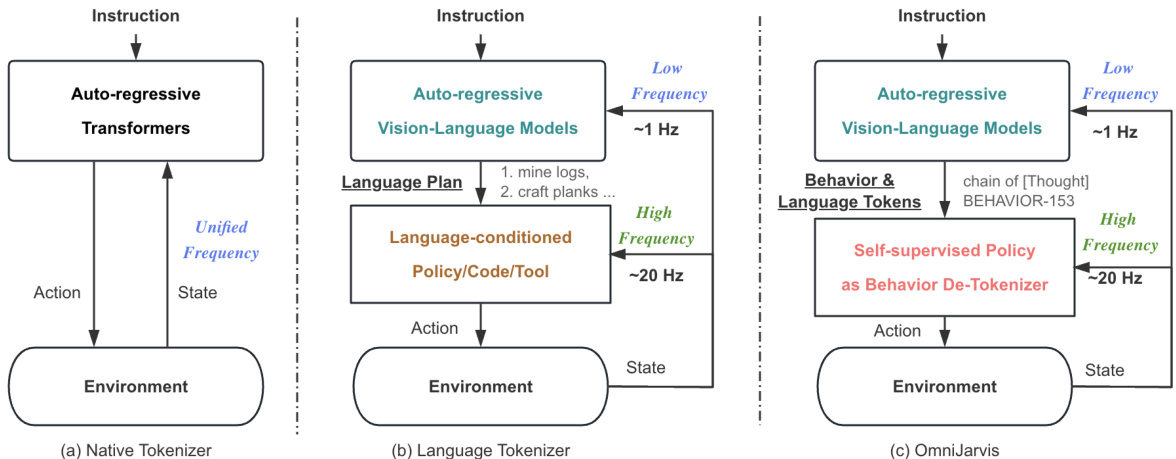

🔼 This figure compares three different architectures for Vision-Language-Action models. (a) shows a simple, high-frequency model directly mapping instructions to actions based on the current state. (b) presents a hierarchical model using a large language model for planning and a separate controller for execution. (c) illustrates OmniJARVIS, which uses a self-supervised behavior tokenizer to create behavior tokens that are jointly modeled with vision and language, enabling more efficient and seamless action generation.

read the caption

Figure 8: Comparative Framework of Vision-Language Action Models. (a) depicts a model where upon receiving a language instruction, actions are directly output based on the environmental state, facilitating immediate interaction with the environment at a unified frequency. Smaller models with <1B parameters like VPT [2] maintain higher frequencies (>20Hz), though their capability for complex reasoning tasks is limited. Larger models with >7B parameters such as RT-2 [6], offer enhanced performance but operate at significantly reduced frequencies (2-3Hz). (b) illustrates a common approach utilizing large vision-language models for planning, subsequently outputting language goals [46, 14, 4]. A language-conditioned policy then translates these language goals into actions at a real-time interaction rate of 20Hz, with high-level models re-planning at less than 1Hz. This hierarchical structure balances interaction frequency and performance, while it requires language as an intermediary and additional language labels. The training process of high-level vision-language models and language-conditioned policies are separate, thus performing poorly on tasks that can not be easily connected by language. (c) (ours) mirrors the hierarchical structure of (b) but differentiates by employing a self-supervised encoder-decoder policy [10] and FSQ quantization [34] as a behavior tokenizer. The upper-level vision-language models produce self-supervised behavior tokens, which are then conditioned by a policy decoder to output actions, facilitating environment interaction. The behavior tokens are injected into the training corpus of vision-language-action models, which enables end-to-end inference. This approach also eliminates the need for external language supervision and scales efficiently.

🔼 This figure illustrates the self-supervised learning framework for the behavior tokenizer in OmniJARVIS. It shows how a variational autoencoder (VAE) is modified to learn a discrete representation of behavior trajectories. The encoder part of the VAE acts as the behavior tokenizer, converting continuous action sequences into discrete behavior tokens. These tokens are then used by a policy decoder (the decoder part of the VAE) to generate control commands. The use of a finite scalar quantizer ensures the discrete nature of the learned representation, making it compatible with other modalities in the model.

read the caption

Figure 2: Self-supervised learning for behavior tokenizer of OmniJARVIS. We modify the VAE-based self-supervised learning of behavior trajectories in [10] to train the behavior tokenizer and de-tokenizer in Omni JARVIS. Specifically, we adopt the auto-encoding objective but replace the Gaussian latent with a discrete representation based on Finite Scalar Quantizer [34]. The encoder will then be used as the behavior tokenizer to produce discrete tokens from the actions (behavior trajectories) in multimodal interaction data, while the behavior tokens emitted by OmniJARVIS will be sent to the policy decoder to perform motor control.

🔼 OmniJARVIS architecture is based on a pretrained multimodal language model (MLM) enhanced with behavior tokens. It receives a task, memory, and observation and uses chain-of-thought reasoning to generate behavior tokens that guide actions via a decoder. Every 128 steps, it updates its reasoning with the latest observations and can additionally provide textual responses.

read the caption

Figure 3: Architecture and Inference of OmniJARVIS. The main body of OmniJARVIS is a multimodal language model (MLM) augmented with additional behavior tokens. Given a task instruction, initial memory, and observation, OmniJARVIS will iteratively perform chain-of-thought reasoning and produce behavior tokens as a means of control via the decoder policy (behavior de-tokenizer). Every 128 steps, OmniJARVIS is forced to reason again and produce new behavior tokens with the latest observation. (Not shown above) OmniJARVIS can also make textual responses, e.g. answering questions.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture and inference process of OmniJARVIS. OmniJARVIS is a multimodal language model enhanced with behavior tokens. It takes task instructions, memory, and observations as input and iteratively performs chain-of-thought reasoning to generate behavior tokens. These tokens act as control signals for the decoder policy, which outputs actions. The process is repeated every 128 steps to incorporate the latest observations. OmniJARVIS is also capable of generating textual responses, such as answers to questions.

read the caption

Figure 3: Architecture and Inference of OmniJARVIS. The main body of OmniJARVIS is a multimodal language model (MLM) augmented with additional behavior tokens. Given a task instruction, initial memory, and observation, OmniJARVIS will iteratively perform chain-of-thought reasoning and produce behavior tokens as a means of control via the decoder policy (behavior de-tokenizer). Every 128 steps, OmniJARVIS is forced to reason again and produce new behavior tokens with the latest observation. (Not shown above) OmniJARVIS can also make textual responses, e.g. answering questions.

More on tables

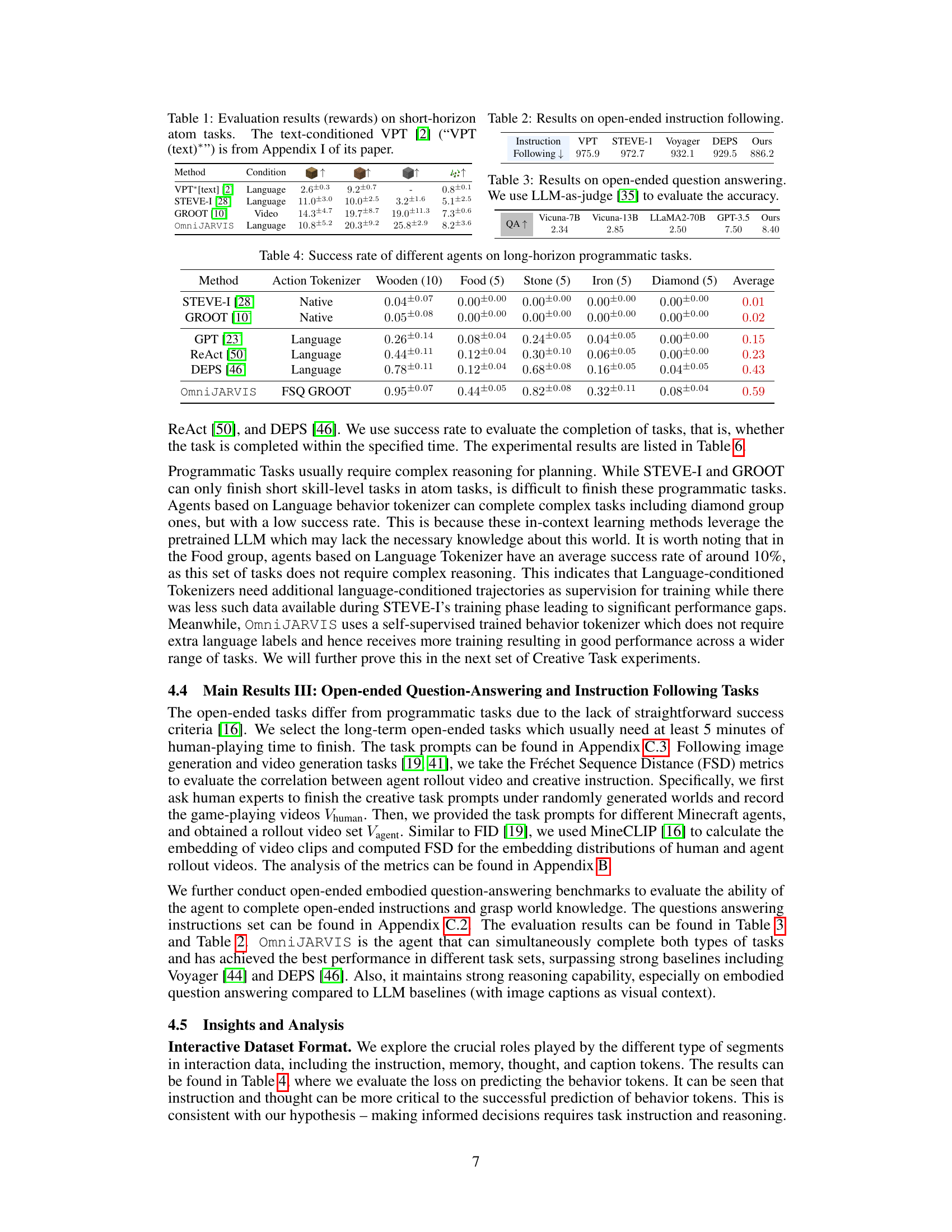

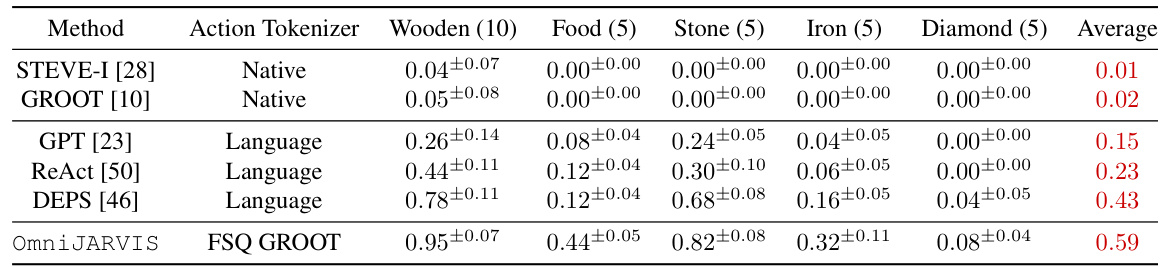

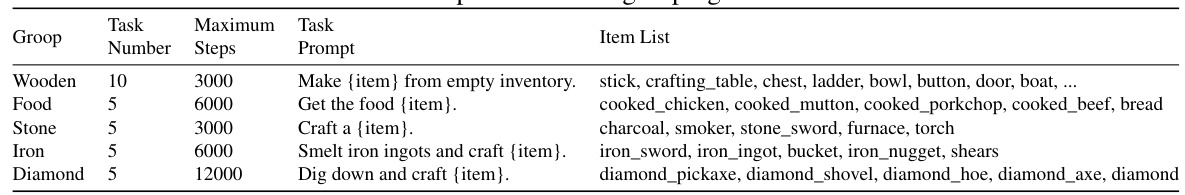

🔼 This table presents the success rates of various agents on 30 long-horizon programmatic Minecraft tasks. These tasks range in difficulty and require a chain of actions to complete, testing the agents’ planning and execution capabilities. The agents are categorized by their action tokenization method: Native (directly producing actions), or Language (using language as an intermediate step). The results are broken down by task category (wooden, food, stone, iron, diamond), showing the average success rate for each agent across all tasks within each category. The table highlights the superior performance of OmniJARVIS, which uses a behavior tokenizer, compared to baselines that rely on native actions or language-based planning.

read the caption

Table 4: Success rate of different agents on long-horizon programmatic tasks.

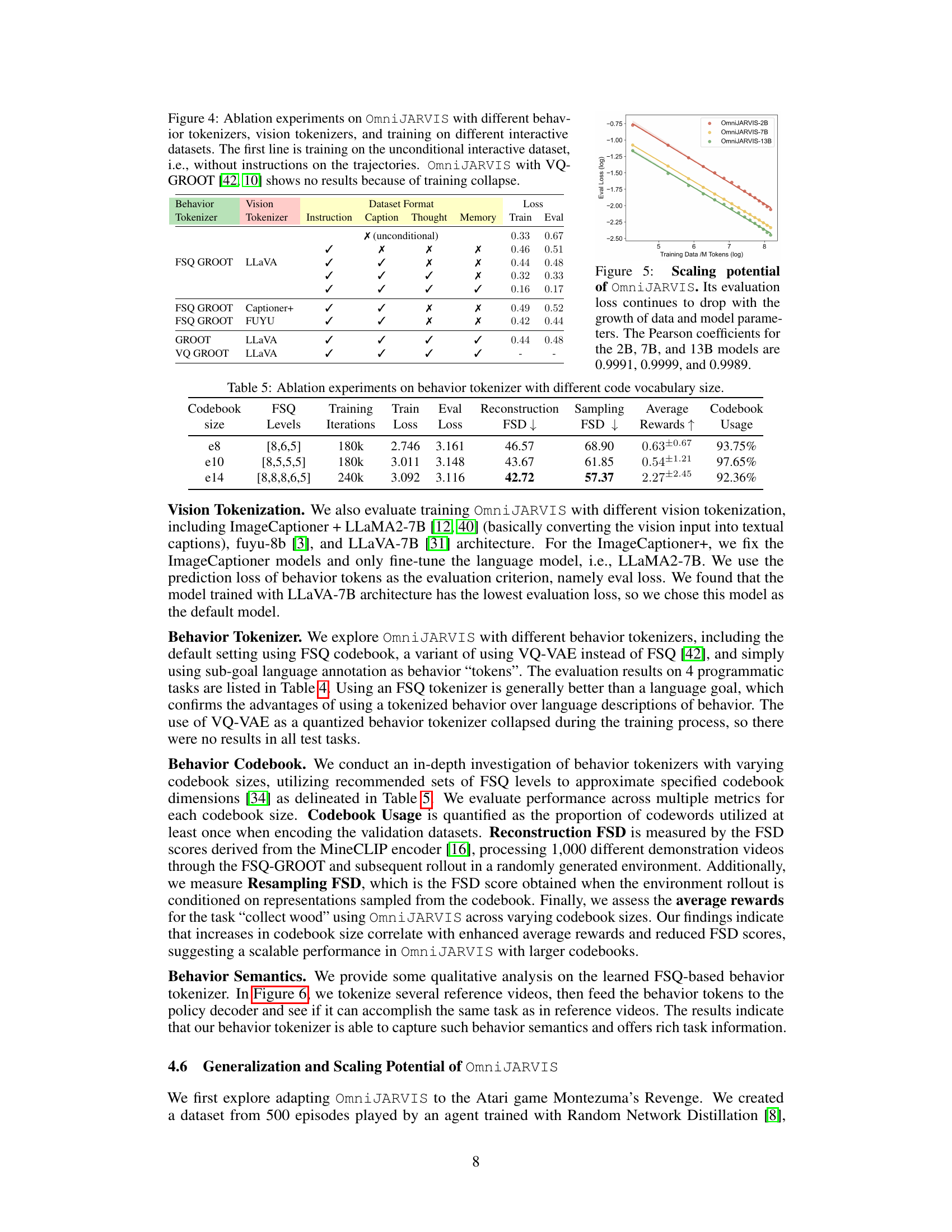

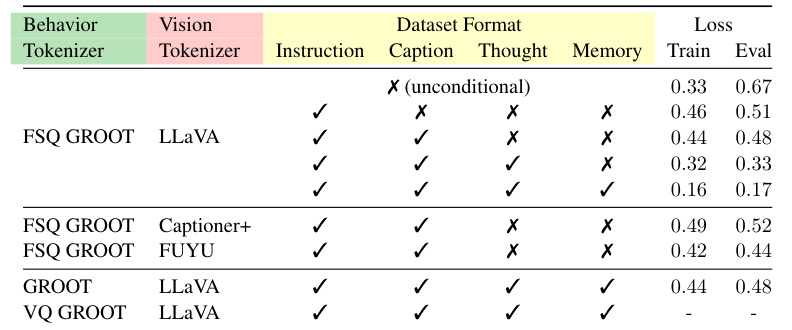

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results of OmniJARVIS. The experiment investigates the impact of different behavior tokenizers (FSQ GROOT, GROOT, VQ GROOT), vision tokenizers (LLaVA, Captioner+, FUYU), and dataset formats (with/without instructions, captions, thoughts, and memory) on the model’s performance. The loss (both training and evaluation) is used as a metric to evaluate the model’s performance under different configurations. The result shows that using FSQ GROOT as the behavior tokenizer and LLaVA as the vision tokenizer, with all components in the dataset, achieves the best performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation experiments on OmniJARVIS with different behavior tokenizers, vision tokenizers, and training on different interactive datasets. The first line is training on the unconditional interactive dataset, i.e., without instructions on the trajectories. OmniJARVIS with VQ-GROOT [42, 10] shows no results because of training collapse.

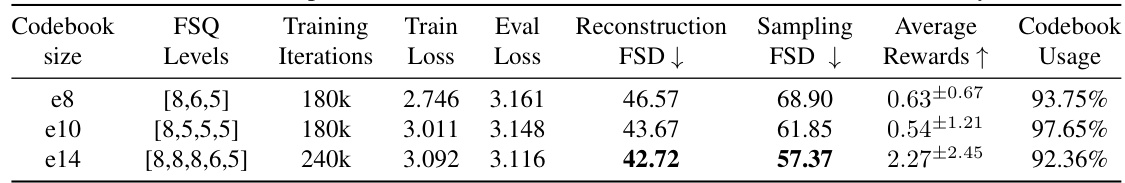

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on the behavior tokenizer using various codebook sizes (e8, e10, e14). It shows the impact of different codebook configurations on training loss, evaluation loss, reconstruction Fréchet Sequence Distance (FSD), sampling FSD and average rewards. The results demonstrate that increasing codebook size generally enhances the performance, but there might be some diminishing returns after a certain size.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation experiments on behavior tokenizer with different code vocabulary size.

🔼 This table presents the success rates of various agents in completing long-horizon programmatic tasks in Minecraft. These tasks require a chain of actions to obtain a final item, starting from an empty inventory. The tasks are categorized into five groups (Wooden, Food, Stone, Iron, Diamond) based on their difficulty. The table compares the performance of OmniJARVIS (using both its own behavior tokenizer and a baseline FSQ GROOT tokenizer), and several other agents using either native behavior tokenizers or Language-based planners. The results show that OmniJARVIS significantly outperforms the other agents, highlighting its ability to effectively perform long-horizon planning and execution.

read the caption

Table 4: Success rate of different agents on long-horizon programmatic tasks.

🔼 This table presents the evaluation results of different agents on four short-horizon atomic tasks in Minecraft. The tasks are basic yet fundamental skills like chopping trees, mining stones, digging dirt, and collecting wheat seeds. The table compares OmniJARVIS’s performance against several baselines (text-conditioned VPT, Open-world Control, STEVE-I, and video-instructed GROOT), showing the average reward of each agent on every task across 10 runs. The results highlight OmniJARVIS’s effectiveness in following straightforward instructions and achieving high average rewards with minimal standard deviation.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation results (rewards) on short-horizon atom tasks. The text-conditioned VPT [2] ('VPT (text)*') is from Appendix I of its paper.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different agents on four simple Minecraft tasks: chopping trees, mining stones, digging dirt, and collecting wheat seeds. The ‘rewards’ represent the average scores achieved by each agent across multiple trials. It compares OmniJARVIS against baselines such as text-conditioned VPT, and other agents from prior works. The goal is to assess the effectiveness of OmniJARVIS on basic, short-horizon tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation results (rewards) on short-horizon atom tasks. The text-conditioned VPT [2] ('VPT (text)*') is from Appendix I of its paper.

Full paper#