↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning algorithms rely on multi-agent interactions, especially in zero-sum games. However, the long-term behavior of these systems remains a significant challenge, often exhibiting complex, unpredictable dynamics. The convergence of learning algorithms to an equilibrium solution (like Nash equilibrium) is particularly important, but this is often not guaranteed.

This paper investigates whether ’no-swap-regret’ dynamics improve convergence in repeated games compared to standard ’no-external-regret’ methods. The researchers find that, under the specific conditions of a symmetric zero-sum game and symmetric initializations for the players, no-swap-regret dynamics do in fact guarantee a strong form of convergence to the Nash equilibrium. However, this result is highly sensitive to these assumptions; relaxing any of these constraints leads to potentially chaotic behavior.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals a surprising connection between symmetry, regret minimization, and convergence in game theory. Understanding these dynamics is vital for designing robust and effective multi-agent learning algorithms, particularly in the increasingly relevant field of self-play. The findings offer significant implications for AI safety and the creation of dependable AI agents.

Visual Insights#

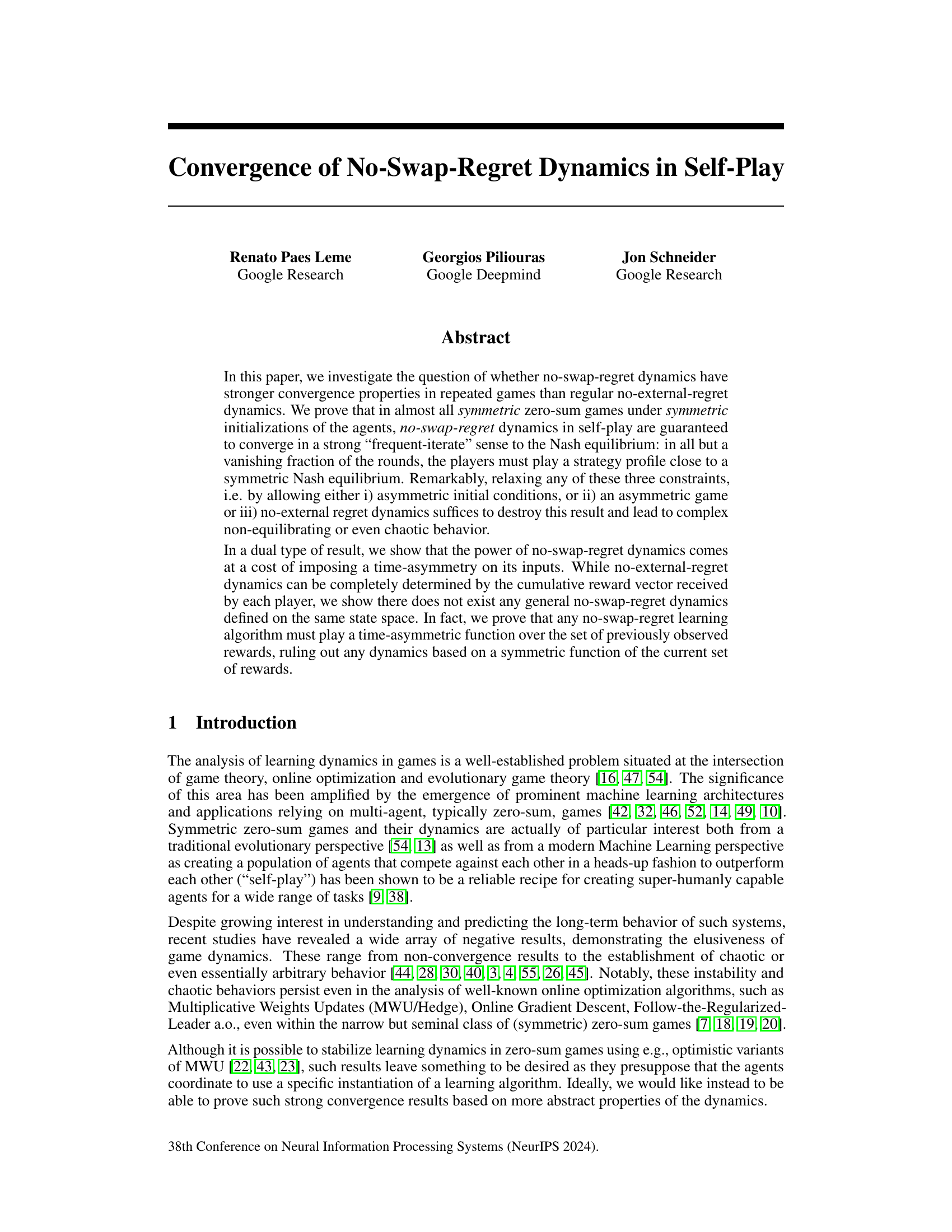

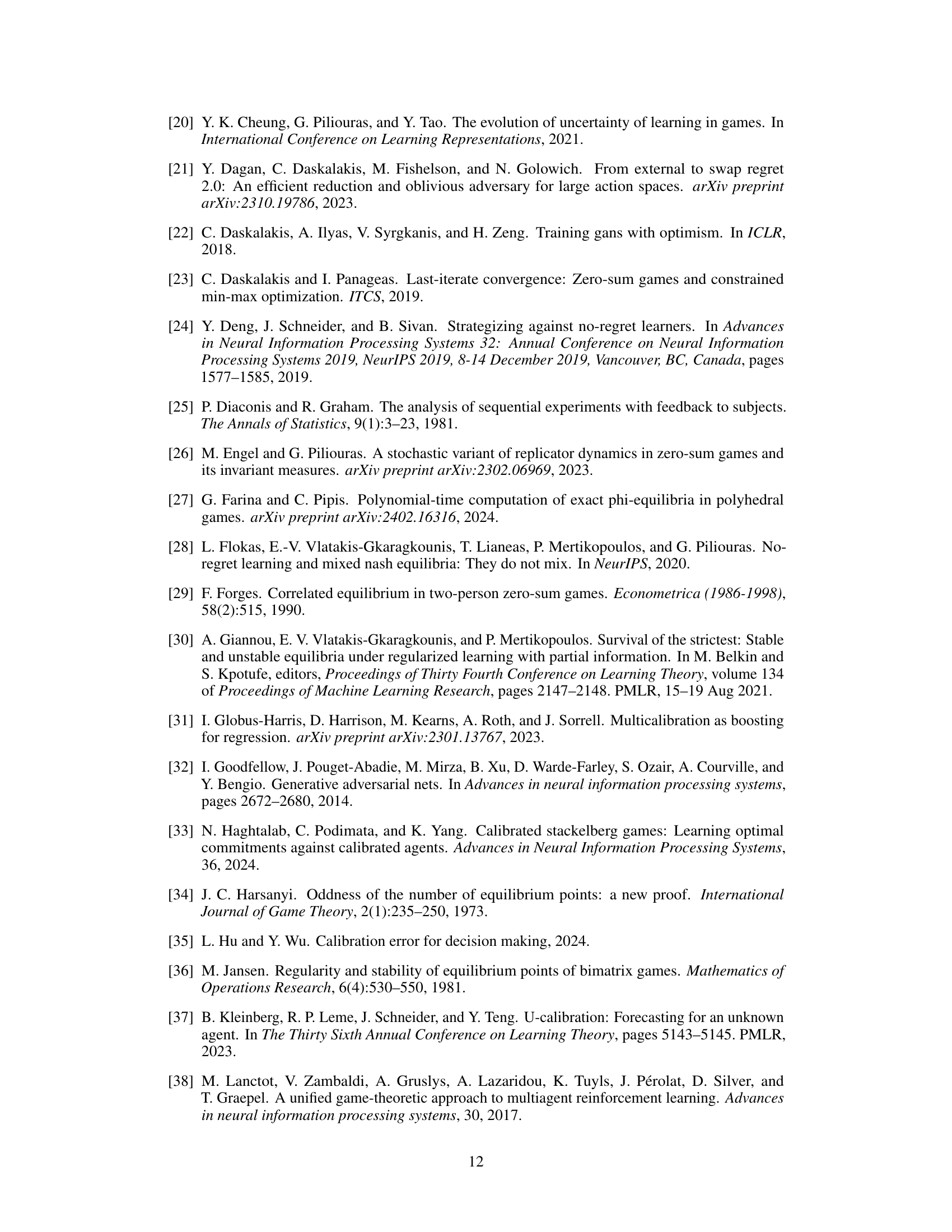

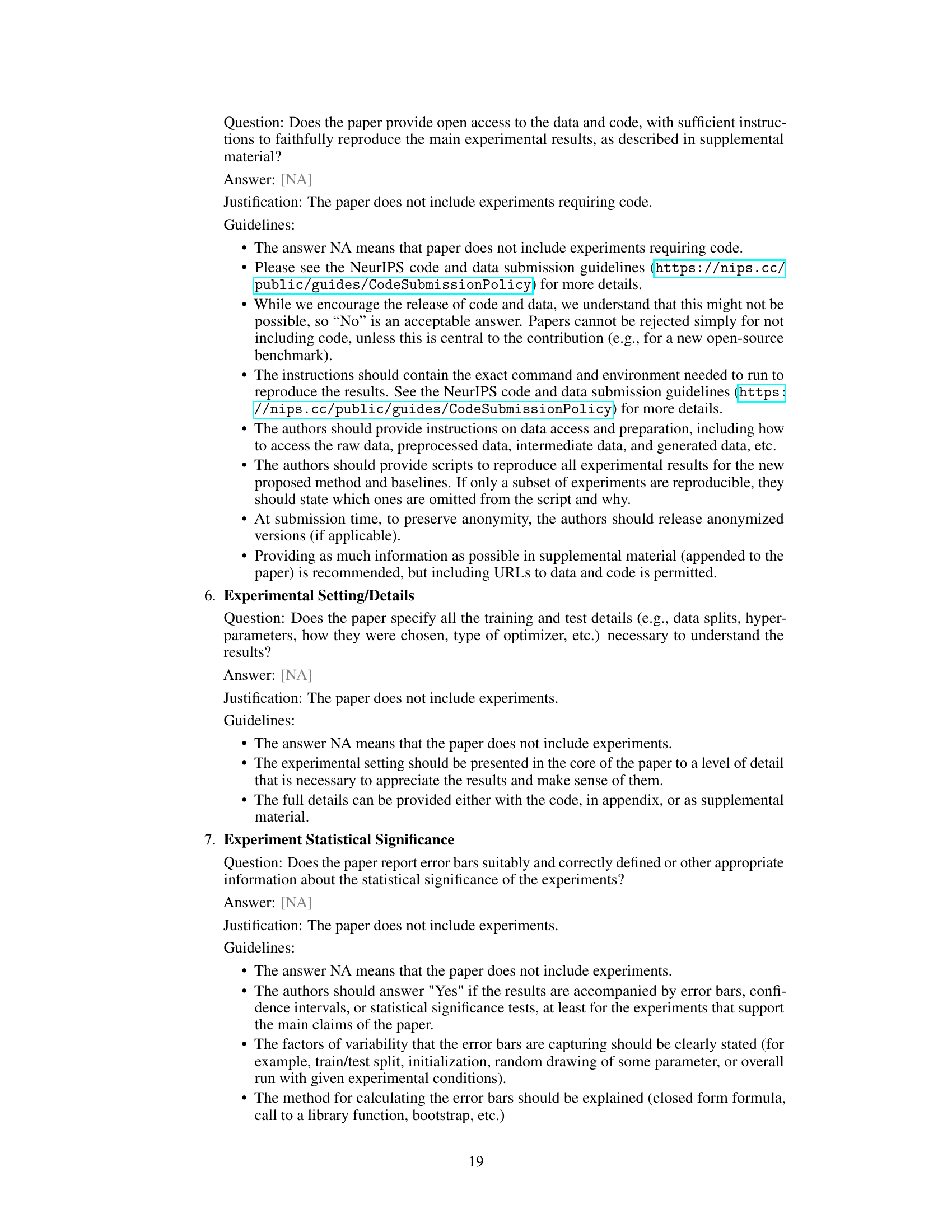

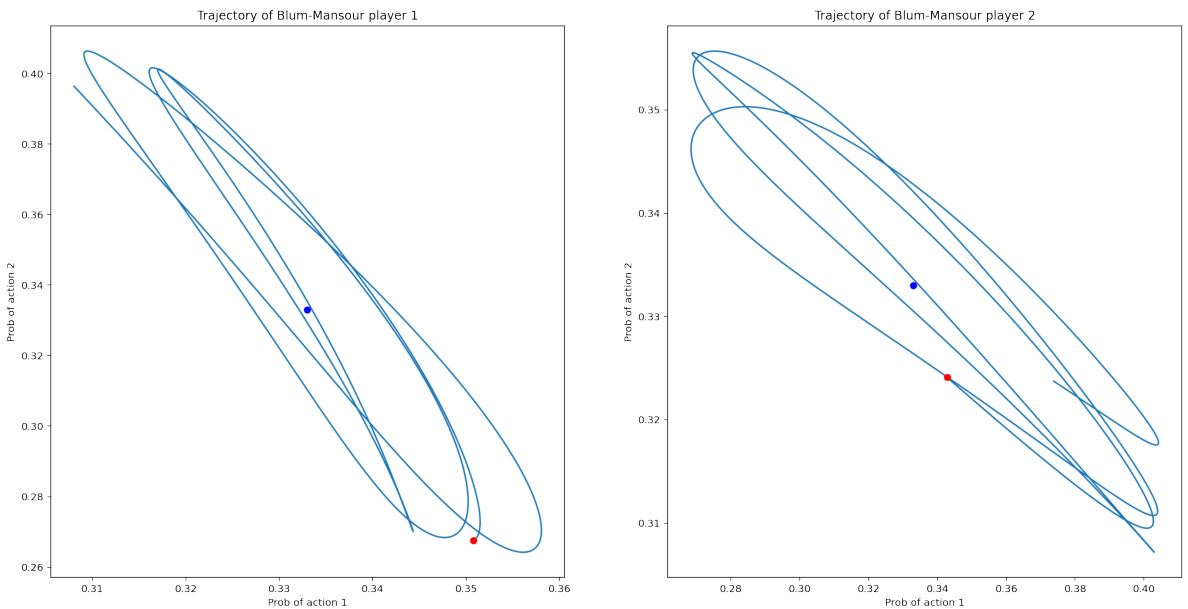

This figure shows the trajectories of two learning algorithms, Multiplicative Weights and Blum-Mansour, when playing the Rock-Paper-Scissors game. The x and y axes represent the probabilities of playing Rock and Paper, respectively. The blue dot marks the Nash equilibrium point, while the red dot indicates the final point reached by each algorithm after 10,000 iterations with a learning rate of 0.001. The figure illustrates the difference in convergence behavior between the two algorithms. Multiplicative Weights approaches the Nash equilibrium but does not converge to it in the last iteration, while Blum-Mansour shows better convergence to the equilibrium point.

In-depth insights#

Regret Dynamics#

Regret dynamics, in the context of game theory and multi-agent learning, explore how agents update their strategies based on past performance. No-regret algorithms guarantee that an agent’s average performance will not be significantly worse than the best fixed strategy in hindsight. However, no-swap regret, a stricter condition, ensures the performance is competitive against the best adaptive deviation policy, reflecting a more dynamic adversarial environment. This difference is crucial in determining the convergence properties of self-play dynamics. In symmetric zero-sum games, under symmetric initial conditions, no-swap regret dynamics exhibit strong convergence to Nash equilibrium, even in the absence of coordination between players. Symmetry, in both game structure and initial conditions, acts as a pivotal stabilizing factor. The study also reveals a time-asymmetry inherent to no-swap regret learning, contrasting with the time-symmetric nature of no-external regret algorithms. This time-asymmetry implies a dependence on the ordering of past rewards, ruling out dynamics solely determined by cumulative rewards. The interplay between symmetry, regret type, and convergence behavior provides valuable insights into the design and analysis of learning algorithms in game-theoretic settings. The inherent complexity of these systems is highlighted by the divergence observed under asymmetries, suggesting a delicate balance between algorithm properties and game characteristics.

Swap Regret Power#

The concept of “Swap Regret Power” in the context of multi-agent learning dynamics refers to the enhanced convergence properties exhibited by algorithms minimizing swap regret, compared to those minimizing standard external regret. Swap regret, a stronger notion of regret, considers not only the best fixed action in hindsight, but also the best sequence of actions, allowing for adaptation to the opponent’s strategy over time. This makes swap-regret minimizing dynamics potentially more powerful. However, this power comes at a cost. The analysis reveals that such enhanced convergence is largely contingent on specific conditions, primarily the symmetry of the game and the initializations of players’ strategies. Relaxing symmetry eliminates the guaranteed convergence to Nash equilibria, emphasizing the critical role of symmetry in harnessing swap regret’s power. The time-asymmetric nature of no-swap regret dynamics is also highlighted, contrasting with the time-symmetric nature of no-external-regret algorithms. This asymmetry fundamentally distinguishes swap-regret minimizing dynamics and further contributes to the nuanced understanding of its power and limitations.

Symmetry’s Role#

The concept of symmetry plays a crucial role in the convergence analysis of no-swap-regret dynamics in self-play, particularly within symmetric zero-sum games. Symmetry in game structure and agent initializations is shown to be a powerful catalyst for convergence to Nash equilibrium, guaranteeing that players’ strategies frequently approach the equilibrium point. This strong convergence result hinges critically on symmetry. Relaxing any of the three key constraints (symmetric game, symmetric initializations, and no-swap regret dynamics) leads to significantly more complex and potentially chaotic behavior, highlighting the importance of symmetry. The paper elegantly demonstrates that the power of no-swap-regret dynamics is inherently tied to a time-asymmetric function over past rewards, a property absent in time-symmetric no-external regret dynamics. This time-asymmetry, despite potentially offering advantages, is not compatible with symmetric reward structures, further emphasizing the pivotal role of symmetry in the analysis.

Time-Asymmetry Cost#

The concept of “Time-Asymmetry Cost” in the context of no-swap-regret dynamics highlights a crucial limitation. Unlike no-external-regret algorithms, which can base their actions solely on cumulative rewards, no-swap-regret methods require a time-asymmetric function over past rewards. This asymmetry means the algorithm’s behavior isn’t solely determined by the current state of rewards, unlike symmetrical approaches; past reward sequence matters. This inherent time-dependence increases complexity. It rules out any dynamics defined by symmetrical functions of the current reward set. This restriction implies that designing efficient no-swap-regret algorithms is significantly harder, as they necessitate a more sophisticated mechanism to track and utilize the temporal order of reward information. The trade-off is that this added complexity might yield stronger convergence properties, particularly in the context of symmetric zero-sum games. Therefore, the “Time-Asymmetry Cost” represents the price paid for achieving stronger convergence guarantees, demanding more intricate algorithm designs that explicitly consider the temporal dynamics of the game’s reward structure.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extending the theoretical framework to non-zero-sum games or asymmetric games. Investigating the impact of different learning algorithms and their inherent properties on convergence behavior would provide deeper insights into the dynamics of swap regret. Exploring scenarios beyond symmetric initializations is crucial to fully understand the role of symmetry in these games. Another avenue is to analyze the time-complexity and computational efficiency of no-swap-regret algorithms, particularly in large-scale scenarios. Finally, applying the findings to real-world applications such as multi-agent reinforcement learning and automated negotiation systems would demonstrate the practical implications and robustness of the theoretical results. Empirical validation through experiments with specific games and learning algorithms would complement the theoretical analysis and help confirm predictions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

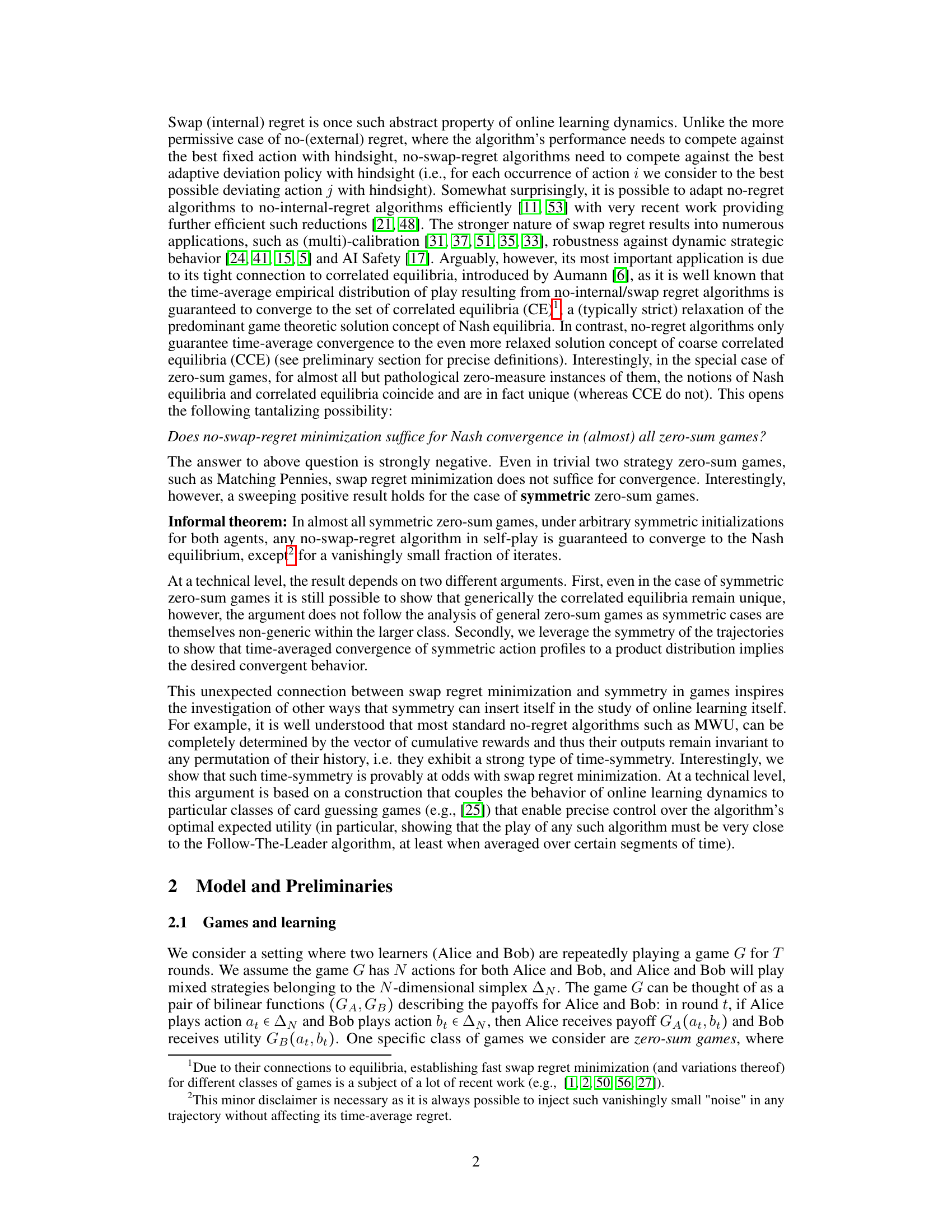

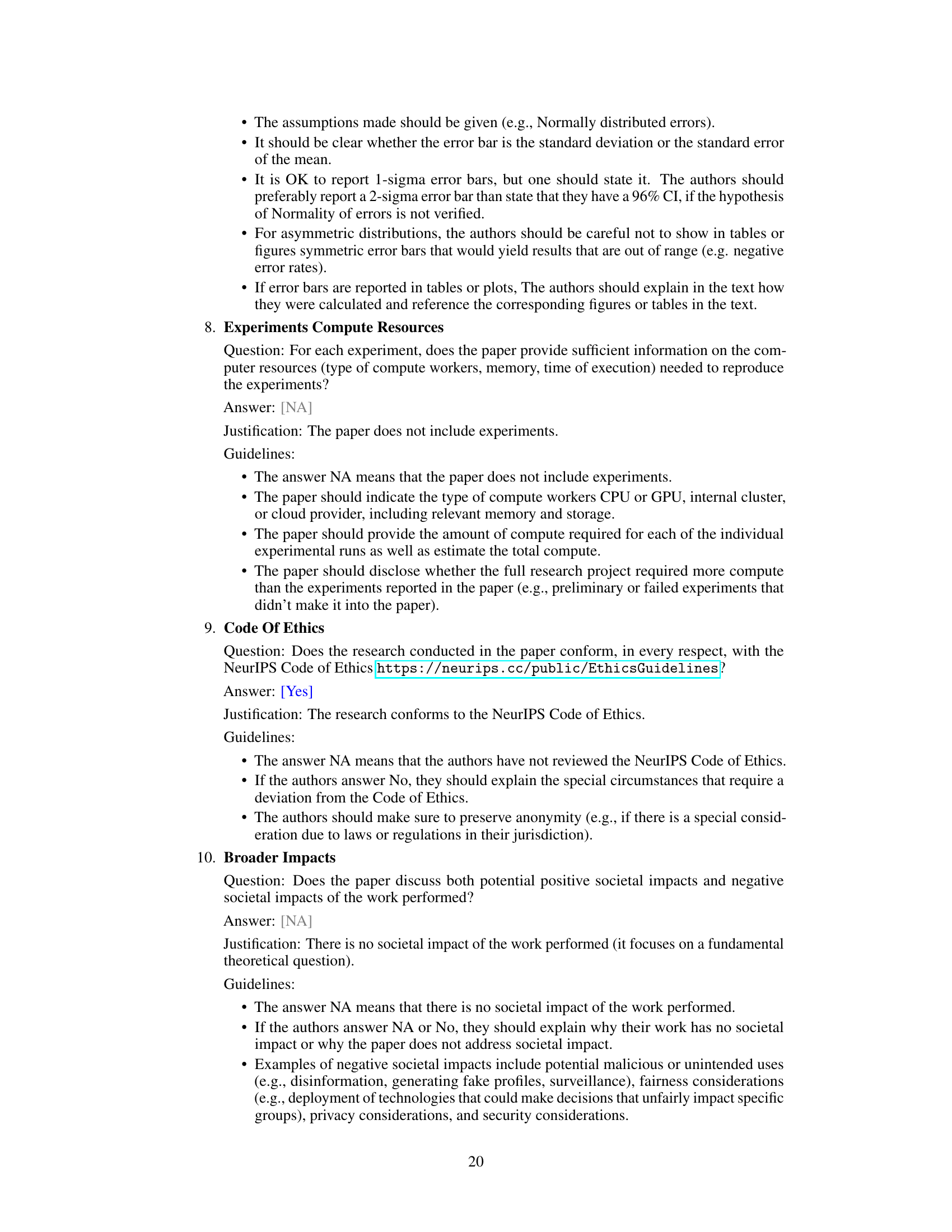

This figure shows the trajectories of two learning algorithms, Multiplicative Weights and Blum-Mansour, when playing the Rock-Paper-Scissors-Lizard-Spock game (a five-strategy extension of Rock-Paper-Scissors). The x and y axes represent the probability of playing two specific actions (e.g., Rock and Paper). The blue dot indicates the Nash equilibrium, while the red dot marks the final iterate after a set number of iterations. The figure illustrates the difference in convergence behavior between the two algorithms in this more complex game setting.

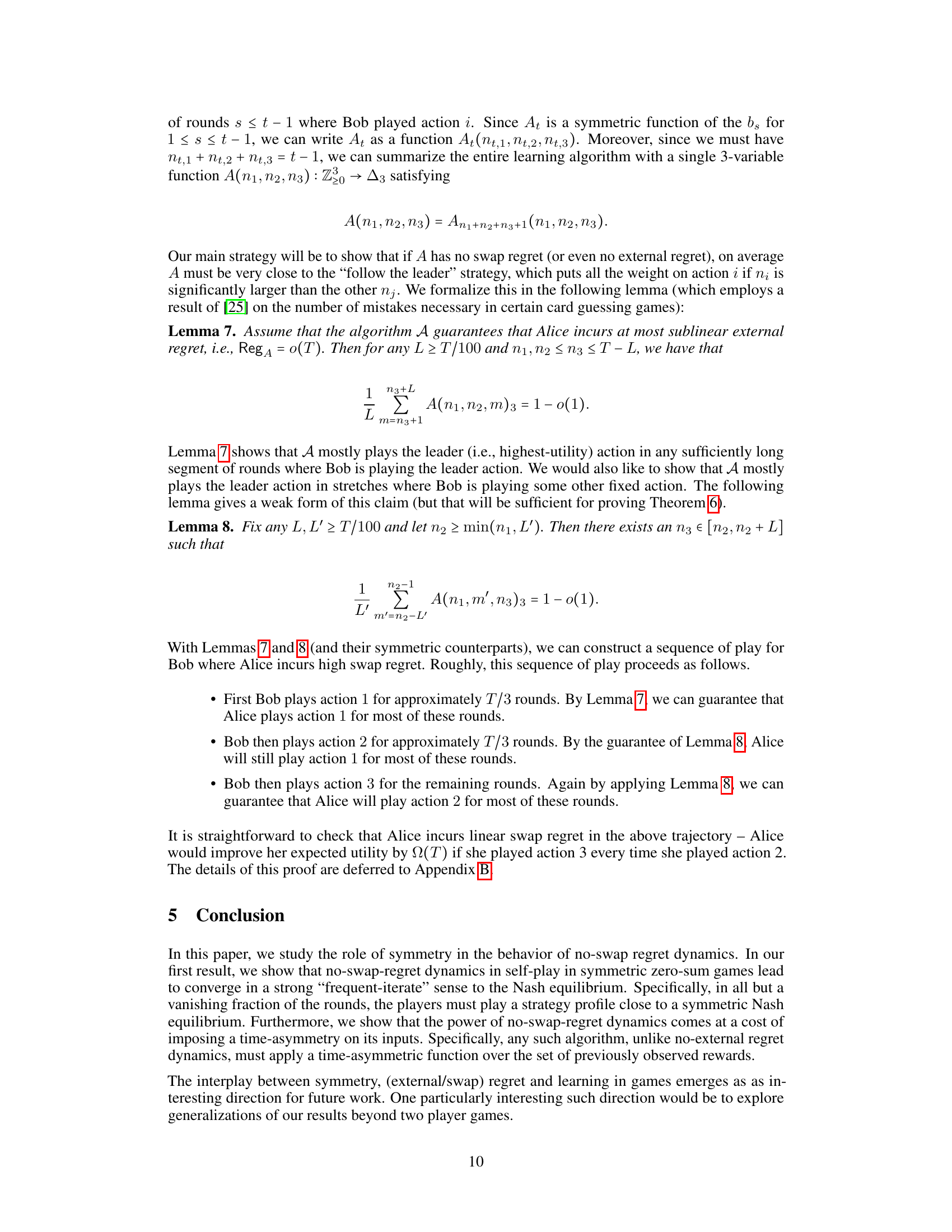

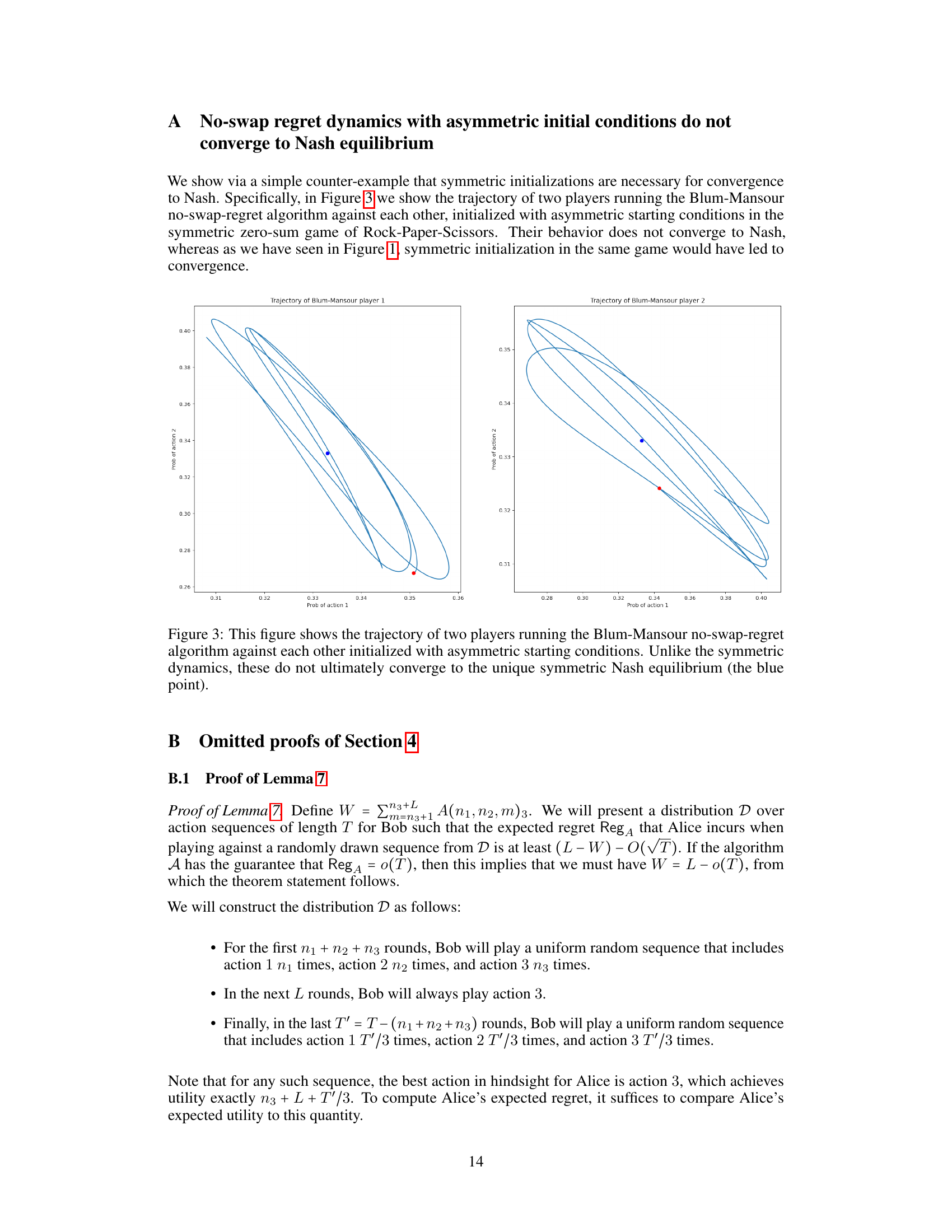

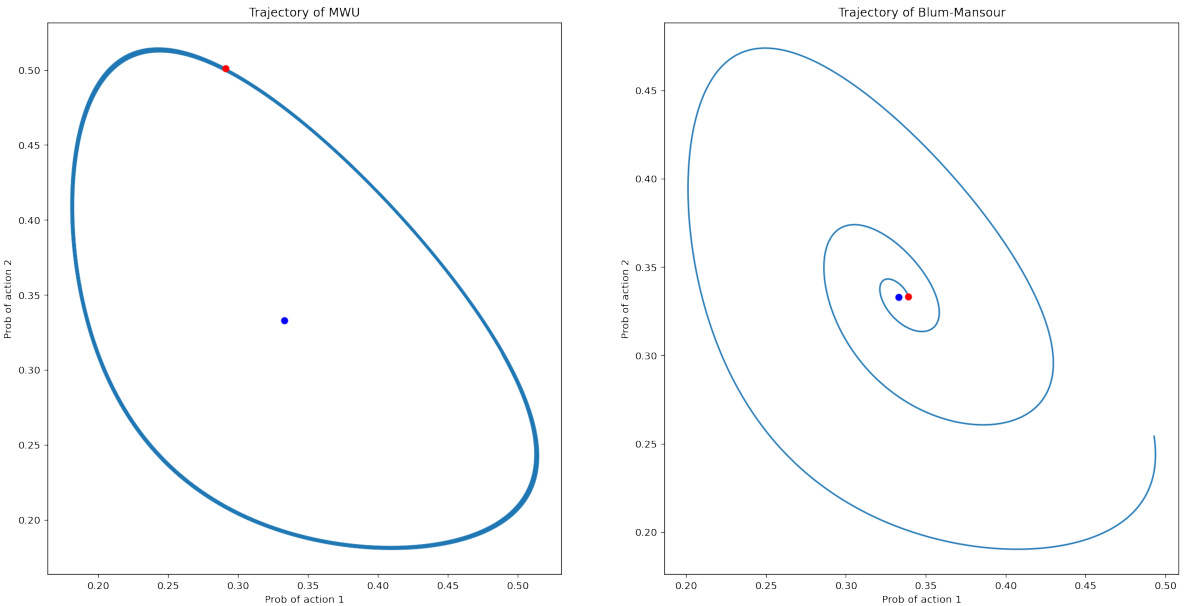

This figure shows trajectories of two players using the Blum-Mansour algorithm, a no-swap-regret learning algorithm. The players start with asymmetric initial conditions (different starting probabilities for actions) in a symmetric zero-sum game (Rock-Paper-Scissors). Unlike Figure 1, where symmetric initializations led to convergence to the Nash equilibrium, here the trajectories do not converge, illustrating that symmetric initializations are crucial for the convergence result.

Full paper#