↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many existing methods for ensuring fairness in machine learning models struggle with noisy labels, leading to inaccurate and unfair outcomes. This issue is particularly significant in real-world applications where data is often imperfect. Previous attempts to solve this problem required computationally expensive full model retraining, limiting their practicality.

This research tackles the problem of noisy labels in fair machine learning by introducing a novel label-correction method. This method uses label spreading on a nearest-neighbors graph built from model embeddings. This approach significantly improves the performance of state-of-the-art last-layer retraining methods, achieving the best accuracy while maintaining efficiency and minimal computational overhead. The method also works across a wide range of datasets and noise levels, making it applicable to various settings and problems in fair machine learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on fair machine learning, particularly those dealing with noisy datasets. It offers a practical and efficient solution to improve fairness in models by addressing label noise, a common issue that significantly impacts model accuracy and fairness. The proposed method is readily applicable to existing fairness-enhancing techniques, expanding research possibilities and making fairness-aware models more robust. Its simplicity and effectiveness make it a valuable contribution to the field.

Visual Insights#

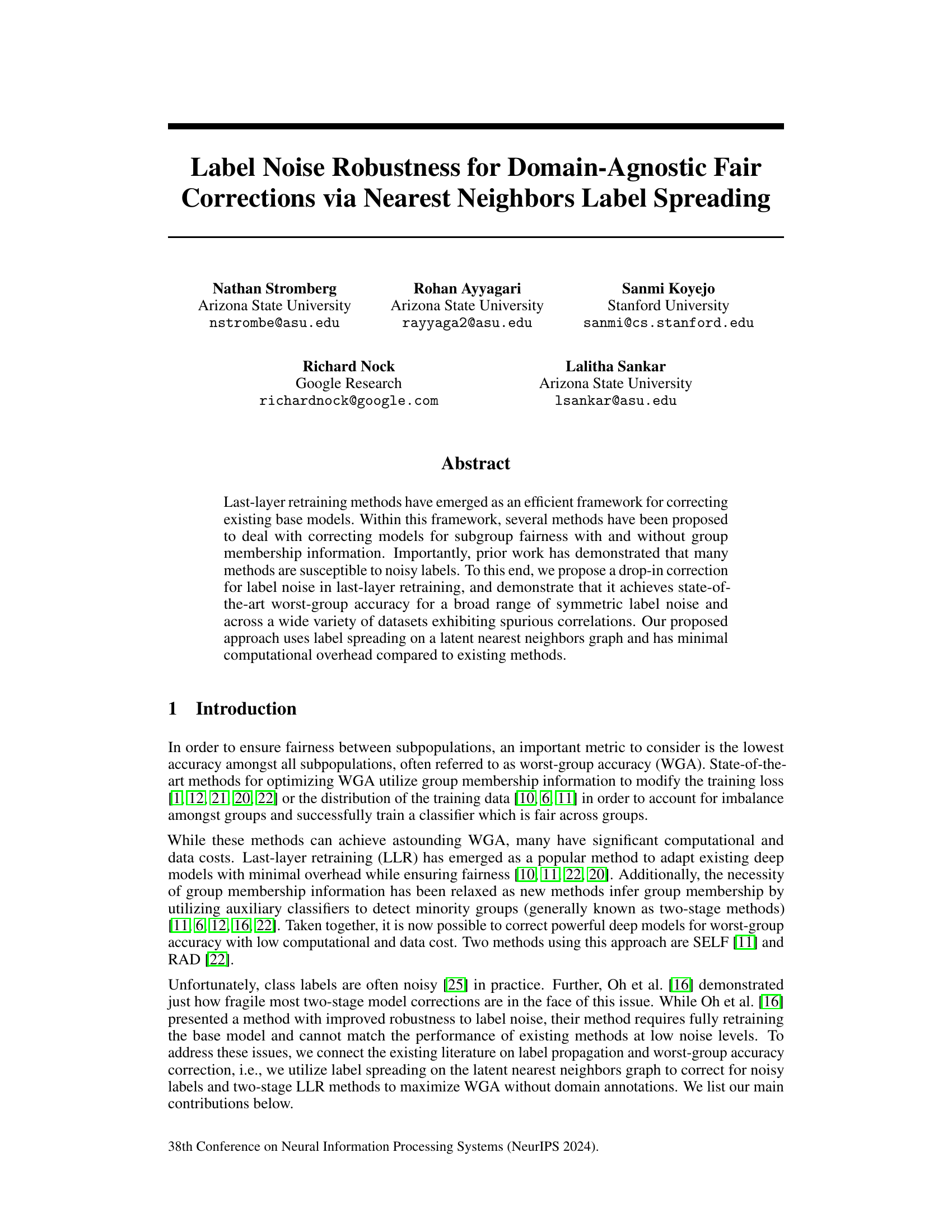

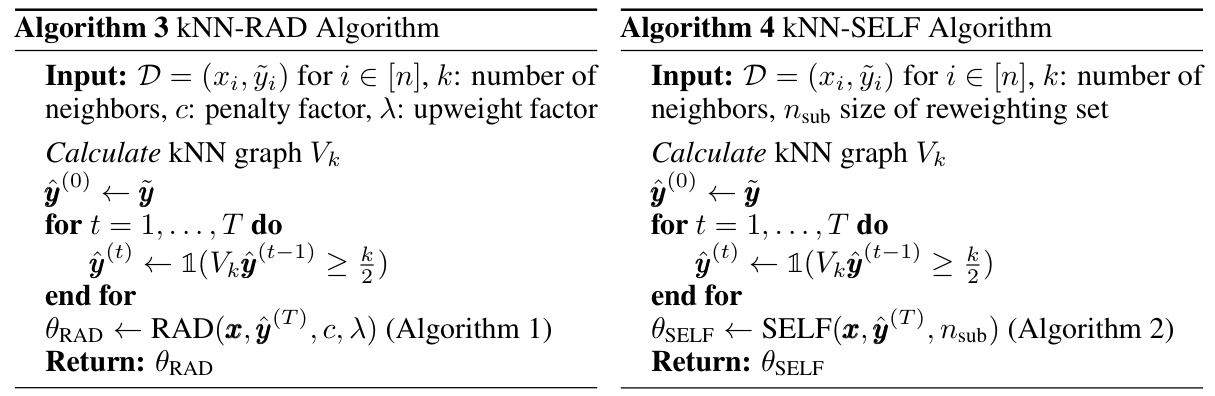

This figure shows the accuracy of KNN label spreading on three different datasets (CelebA, Waterbirds, and CMNIST) under 20% symmetric label noise. The x-axis represents the number of nearest neighbors considered, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The plots show that CelebA and Waterbirds achieve high accuracy with a large number of neighbors, indicating that the embeddings are well-separated. CMNIST, however, shows decreased performance as the number of neighbors increases, likely due to less well-separated embeddings in this dataset.

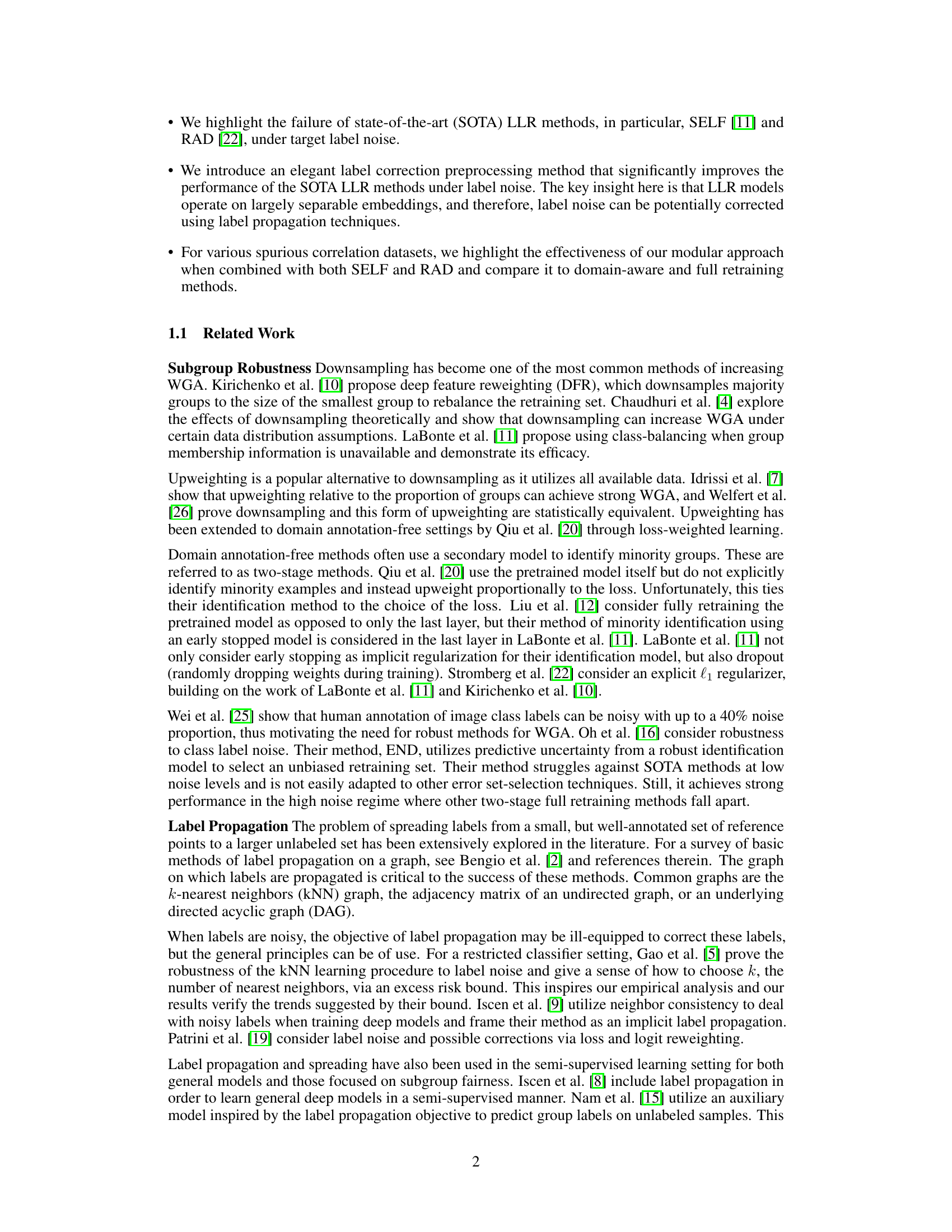

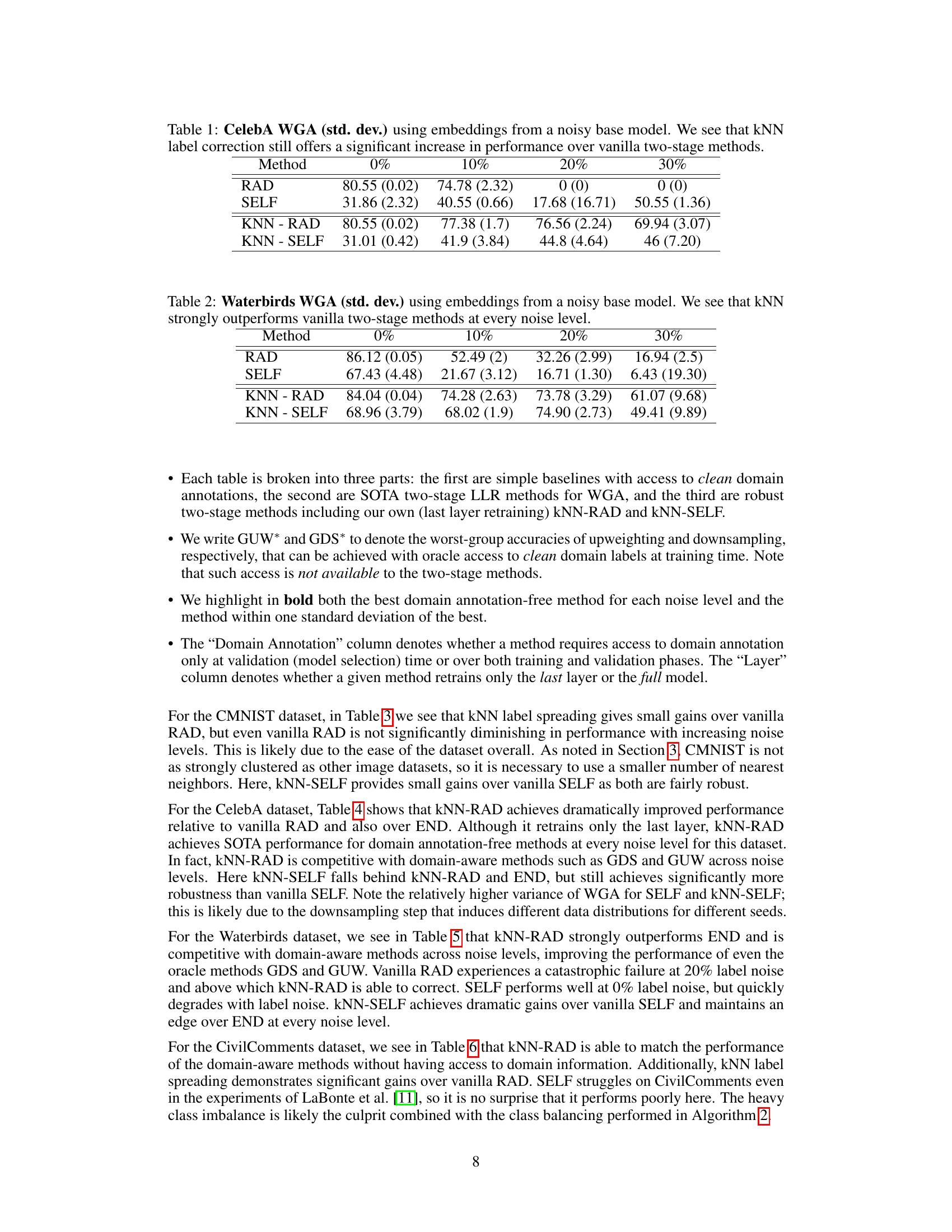

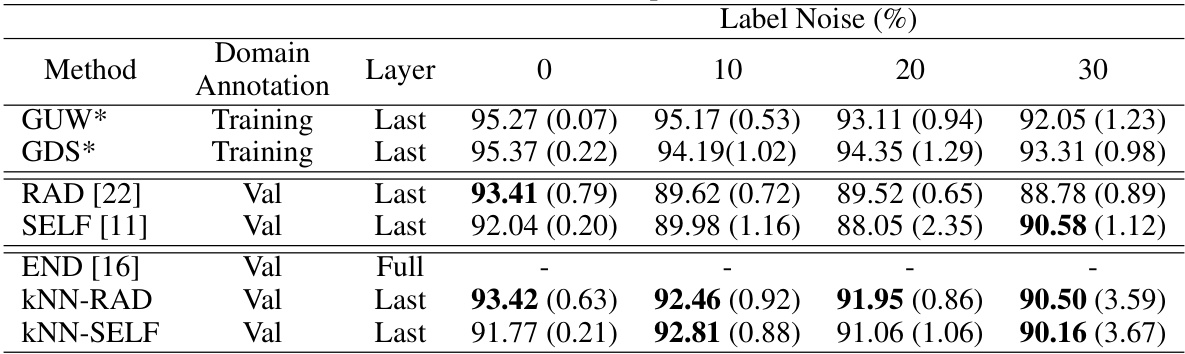

This table shows the worst-group accuracy (WGA) and standard deviation for different methods on the CelebA dataset when using embeddings from a noisy base model. It compares the performance of standard two-stage methods (RAD and SELF), their improved versions using KNN label correction (KNN-RAD and KNN-SELF), and a state-of-the-art method robust to label noise (END). The results are presented for different levels of symmetric label noise (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%). The table demonstrates that the KNN label correction significantly improves the performance of two-stage methods, especially at higher noise levels.

In-depth insights#

Noise Robustness#

The research explores methods for enhancing the robustness of fairness-focused machine learning models against noisy labels. A core challenge addressed is the vulnerability of existing last-layer retraining techniques to noisy data, impacting their ability to achieve fair outcomes across different subgroups. The proposed solution leverages label spreading via a nearest neighbors graph, acting as a preprocessing step to correct for noisy labels before the fairness correction methods are applied. This novel approach demonstrably improves the worst-group accuracy, a key metric for fairness, achieving state-of-the-art performance across various datasets and noise levels. The method’s effectiveness stems from its ability to effectively clean noisy labels using the inherent structure in the data embedding space while adding minimal computational overhead. The study highlights the critical need for noise-robust fairness-aware techniques and offers a practical and effective solution.

LLR Corrections#

Last-layer retraining (LLR) methods offer an efficient approach to correct pre-trained models for subgroup fairness, either using or without group membership information. LLR’s efficiency stems from modifying only the final layer, minimizing computational costs and data requirements compared to full model retraining. However, a significant limitation of LLR methods is their vulnerability to noisy labels, which can severely impact accuracy and fairness. Existing LLR methods often struggle with noisy labels because the error set, used for retraining, becomes heavily skewed by misclassified majority group samples. This masks minority group samples and hinders fairness. Proposed solutions involving robust loss functions or intricate error set selection techniques have only limited success. Addressing this challenge is crucial for the widespread adoption of LLR, ensuring fairness while maintaining efficiency even with imperfect data.

Label Spreading#

The core idea behind label spreading is to improve the robustness of last-layer retraining methods against noisy labels by leveraging the information from a point’s nearest neighbors. This approach assumes that noisy labels are randomly distributed and that, for a given point, a majority of its nearest neighbors will have clean labels. By iteratively updating label estimates based on a weighted majority vote of a point’s neighbors, the method effectively smooths out the noise. The key insight lies in its simplicity and computational efficiency. The method’s effectiveness depends heavily on the quality of the latent space embeddings, which must be well-separated to ensure accurate propagation of clean labels. The choice of the number of nearest neighbors (k) is crucial, as a larger k is needed to mitigate higher noise levels, although this can lead to performance degradation in certain scenarios where clusters are not well-separated. Domain label spreading, on the other hand, appears less effective, likely due to a less clean and tightly-clustered latent space representation for subgroup membership compared to class labels. Despite this limitation, applying label spreading to the target labels before last-layer retraining significantly improves the robustness and worst-group accuracy of the overall approach.

Experimental Setup#

The “Experimental Setup” section of a research paper is crucial for reproducibility and assessing the validity of the results. It should meticulously detail all aspects of the experiments, including datasets used, their preprocessing steps, model architectures, hyperparameter choices and optimization strategies. The rationale behind parameter selections must be clearly articulated, highlighting the methods employed (e.g., grid search, cross-validation). Metrics used for evaluation should be explicitly stated along with their significance. Furthermore, the experimental setup needs to describe the computational resources used, allowing others to gauge the feasibility of replicating the study. Transparency regarding the specific software, hardware, and libraries employed is equally crucial for reproducibility. A robust experimental setup ensures the work is verifiable and allows researchers to build upon the foundation laid by the study, fostering scientific progress and reducing the likelihood of spurious results due to unclear methodology.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the label spreading technique to handle more complex noise models beyond symmetric noise is crucial for real-world applications. Investigating the optimal selection of the number of nearest neighbors (k) in the label spreading process warrants further study, potentially incorporating adaptive methods that adjust k based on local data characteristics. Furthermore, a deeper analysis is needed to understand how different group structures and data distributions affect the performance of the proposed approach, including developing strategies to mitigate its limitations in challenging scenarios such as highly imbalanced datasets or those with weak spurious correlations. Finally, the integration of the proposed label-noise correction methodology into other fairness-enhancing techniques to create a robust, modular fairness pipeline would significantly expand its practical applicability and impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

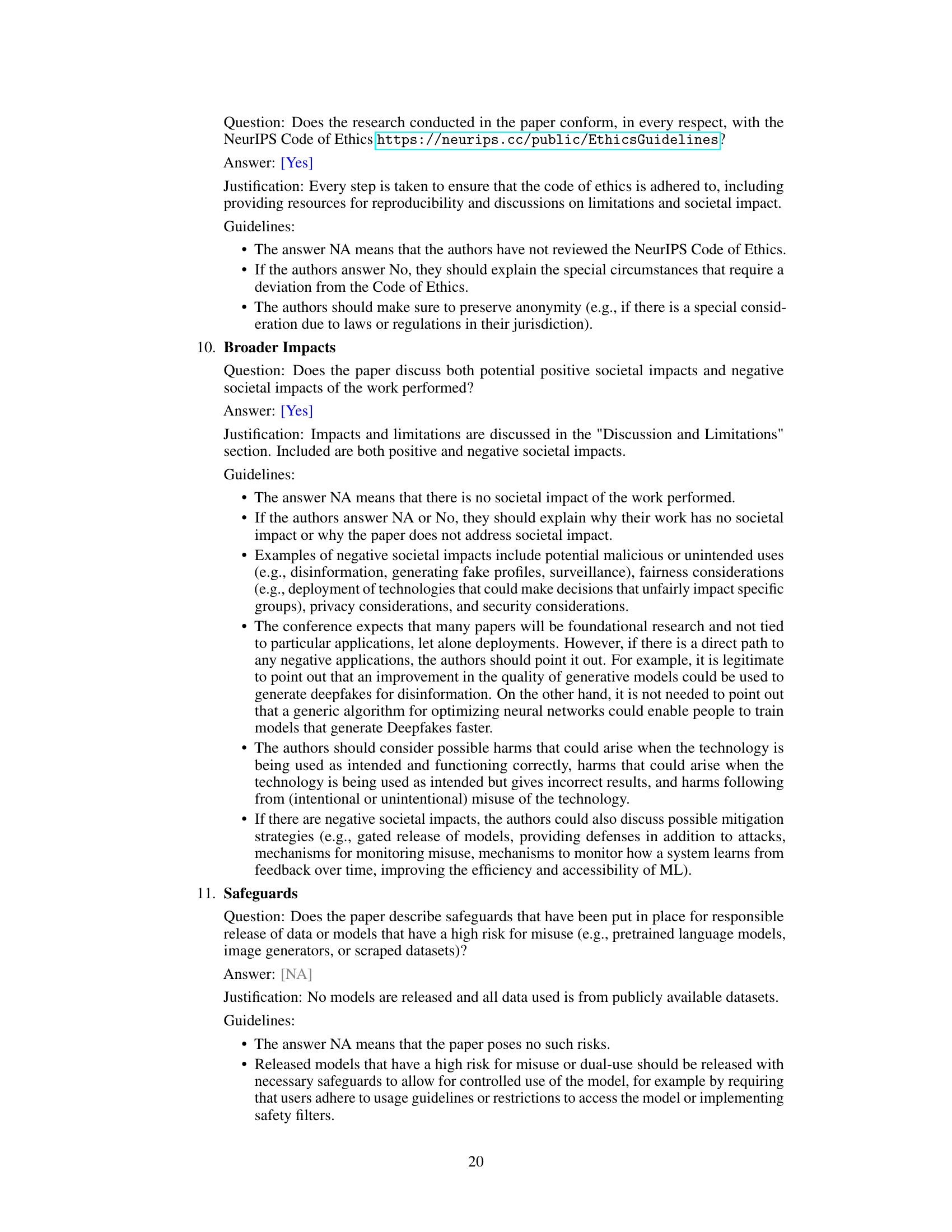

The figure shows the accuracy of KNN label spreading on three datasets (CelebA, Waterbirds, and CMNIST) under 20% symmetric label noise. The x-axis represents the number of rounds of label spreading, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. Each line represents a different number of nearest neighbors (k) used in the KNN algorithm. CelebA and Waterbirds show high accuracy with a large number of nearest neighbors, while CMNIST shows lower accuracy and is more sensitive to the number of neighbors and rounds.

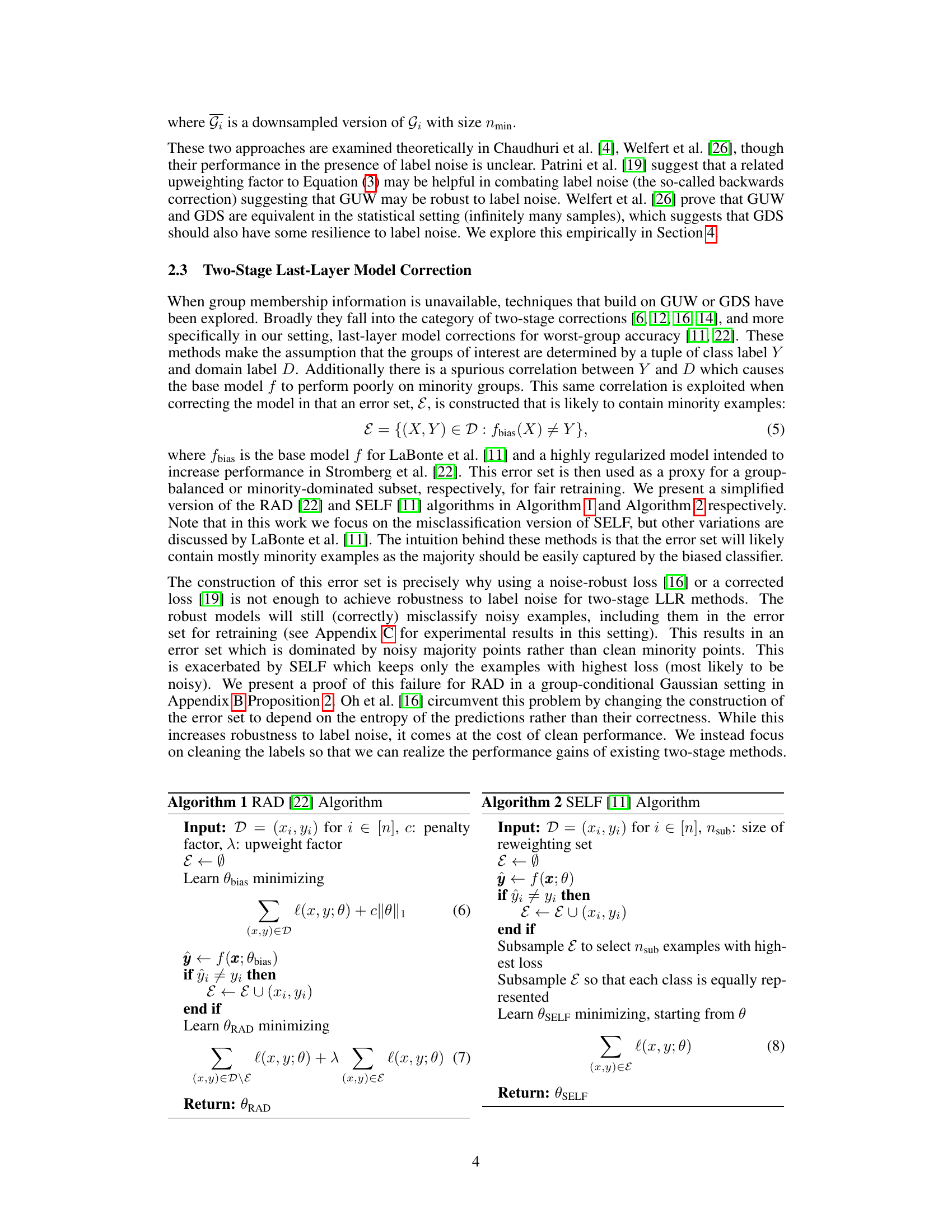

This figure shows the t-SNE visualization of 2048-dimensional latent embeddings reduced to 2 dimensions for three different datasets: CelebA, Waterbirds, and CMNIST. The visualization reveals the different clustering patterns for each dataset. CelebA and Waterbirds exhibit clear separation between classes, while CMNIST shows a more hierarchical and less clearly separated structure. This difference in clustering patterns can explain why label spreading, which relies on neighbor information, might perform differently on these datasets. The less well-separated clusters in CMNIST could hinder the effectiveness of label propagation because noisy labels from neighboring clusters are more likely to negatively impact the accuracy.

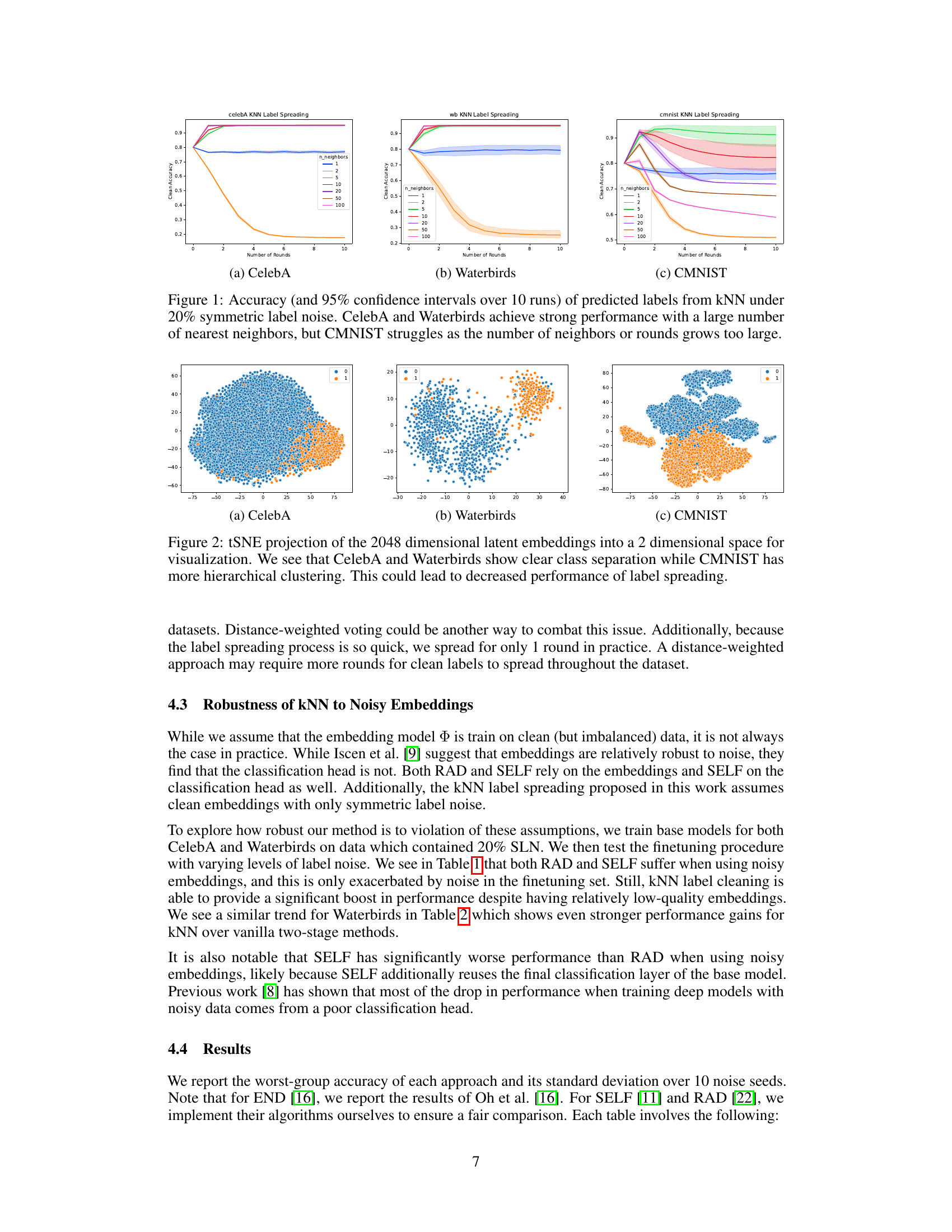

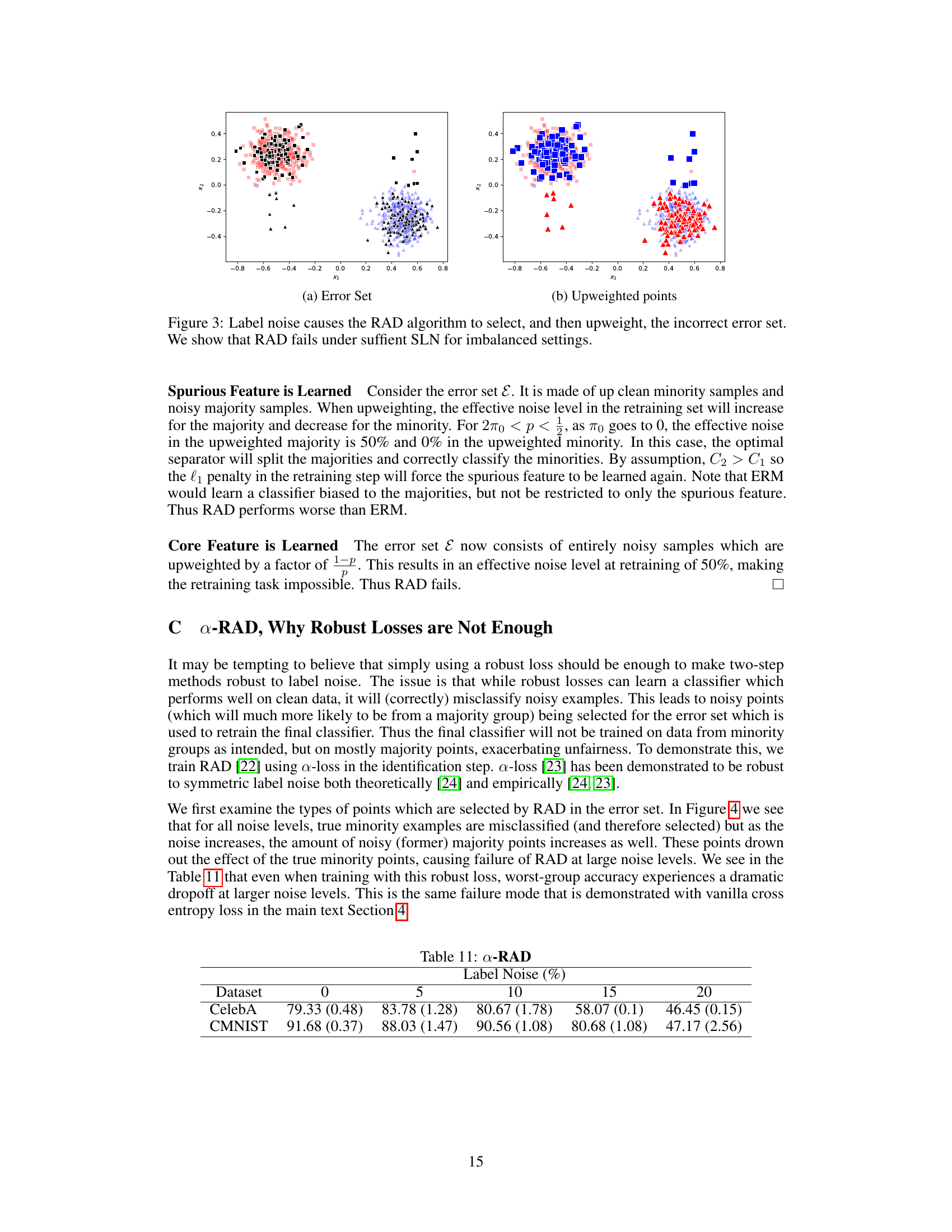

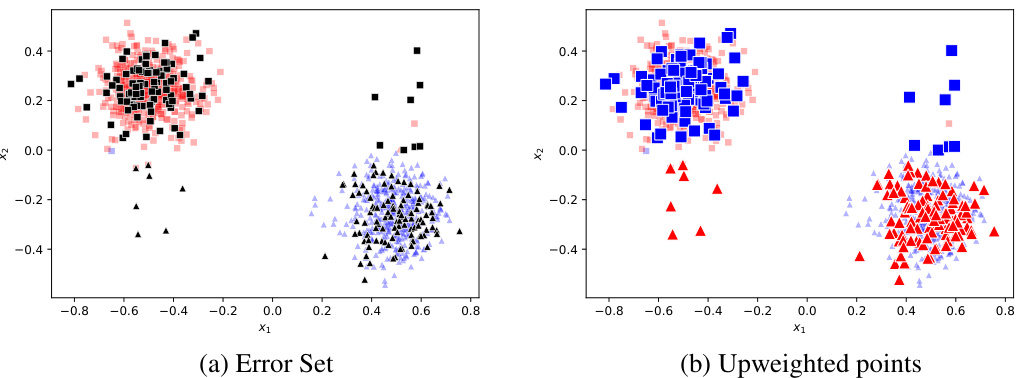

This figure visualizes the effect of label noise on the RAD algorithm’s error set selection and subsequent upweighting. The left panel (a) shows the error set, where points are colored according to their true class labels. We can see that noisy examples are incorrectly included in the error set. The right panel (b) illustrates the upweighted points from this error set. The upweighting process disproportionately emphasizes noisy majority class samples, leading to a biased retraining set that hurts the worst group accuracy. This demonstrates how RAD fails under sufficient symmetric label noise (SLN) in imbalanced settings.

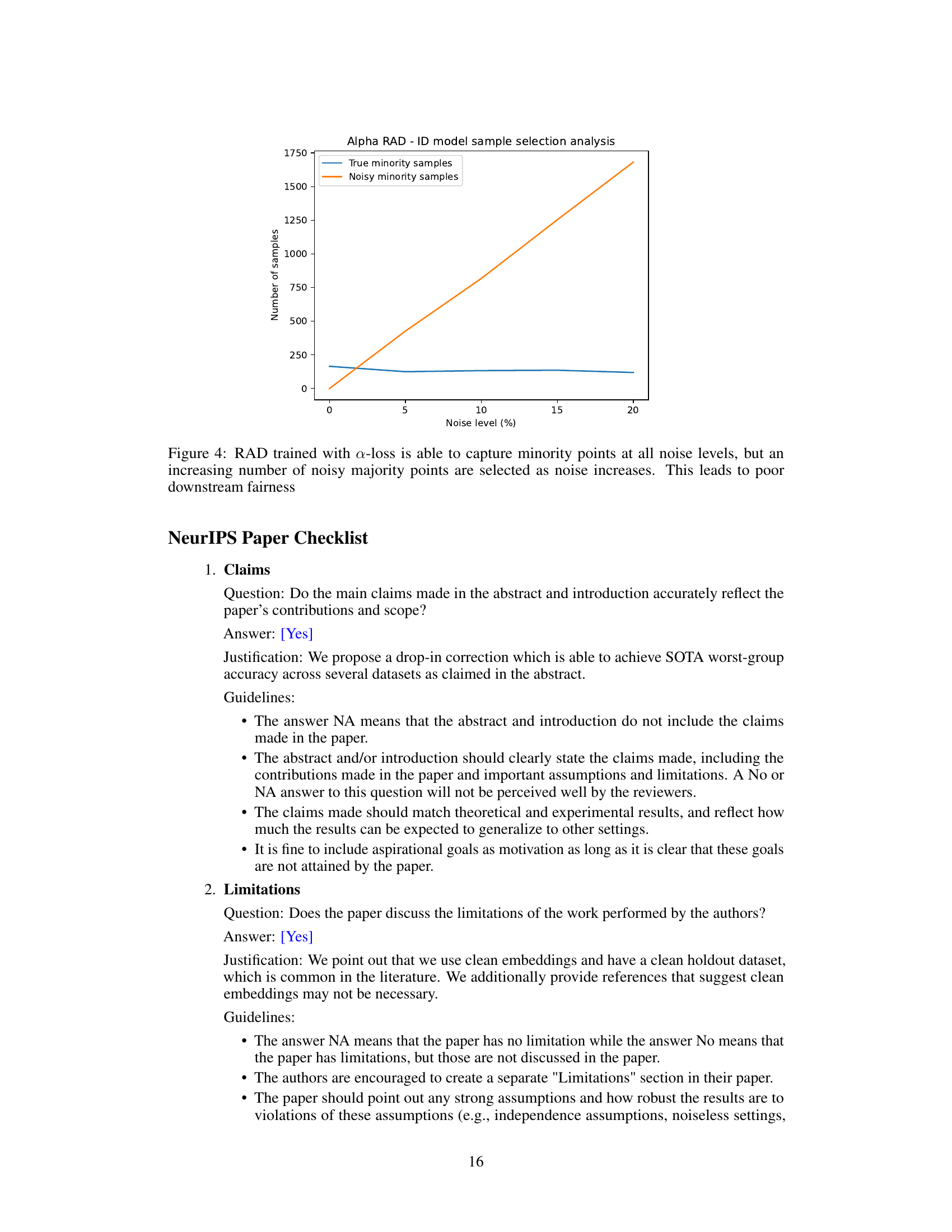

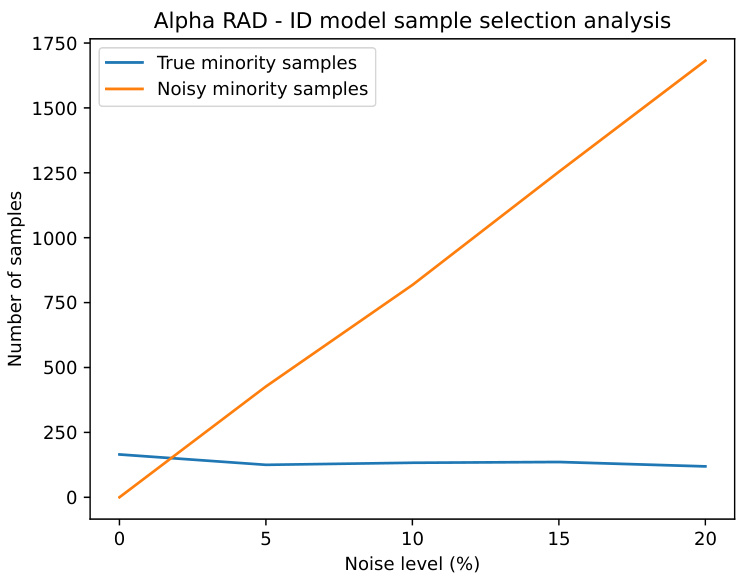

This figure shows how the number of true minority samples and noisy minority samples selected by the RAD algorithm changes with increasing levels of noise. It demonstrates that while the algorithm can capture some true minority samples even with high noise, the number of noisy majority samples selected dramatically increases, which negatively impacts downstream fairness.

More on tables

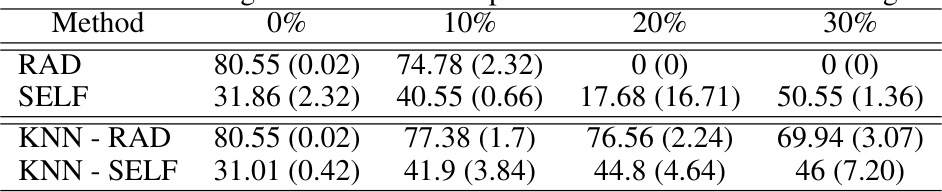

This table presents the worst-group accuracy (WGA) results for the CelebA dataset using embeddings from a noisy base model. It compares the performance of standard two-stage methods (RAD and SELF) with and without the proposed kNN-based label correction preprocessing step. The table shows that kNN label correction significantly improves the WGA, especially at higher noise levels (10%, 20%, and 30%). The results demonstrate that kNN preprocessing enhances the robustness of the two-stage methods.

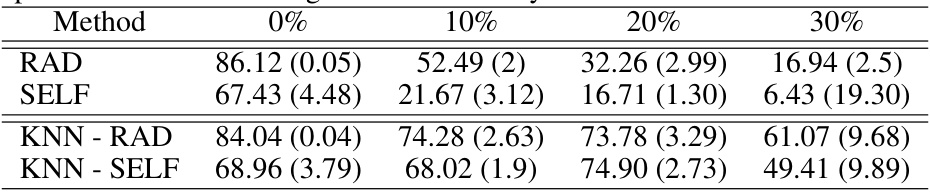

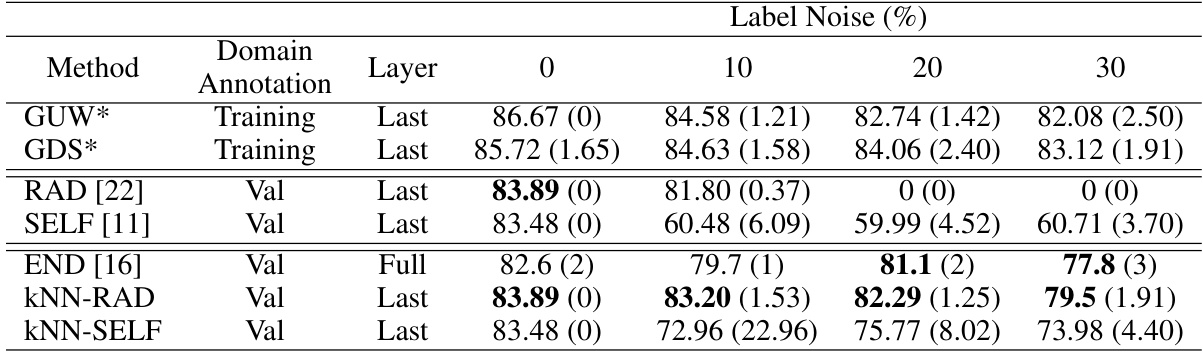

This table presents the worst-group accuracy (WGA) of different methods on the Waterbirds dataset when using embeddings from a noisy base model. It compares the performance of standard two-stage methods (RAD and SELF) with their kNN-enhanced versions (kNN-RAD and kNN-SELF). The results show that incorporating kNN significantly improves WGA across various levels of label noise (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%).

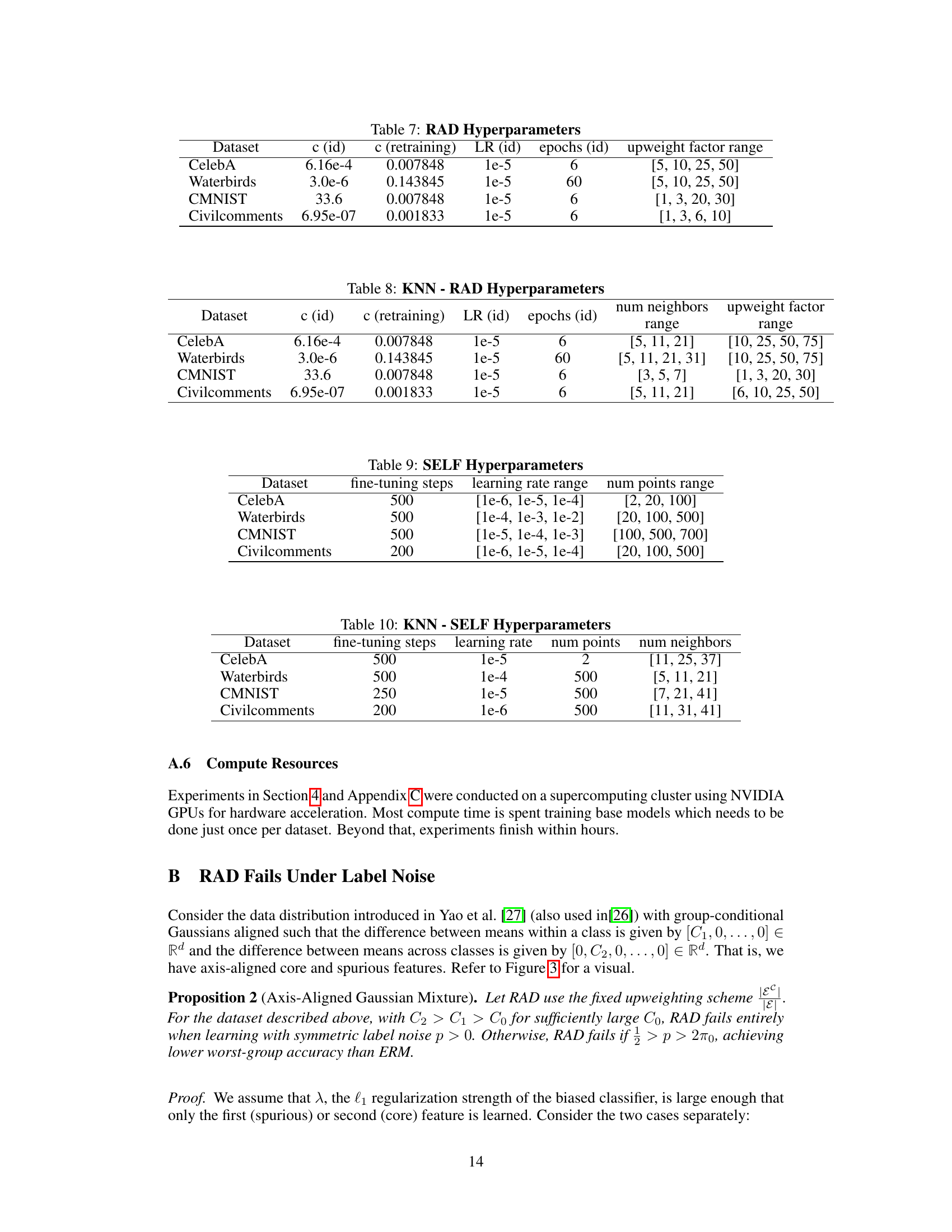

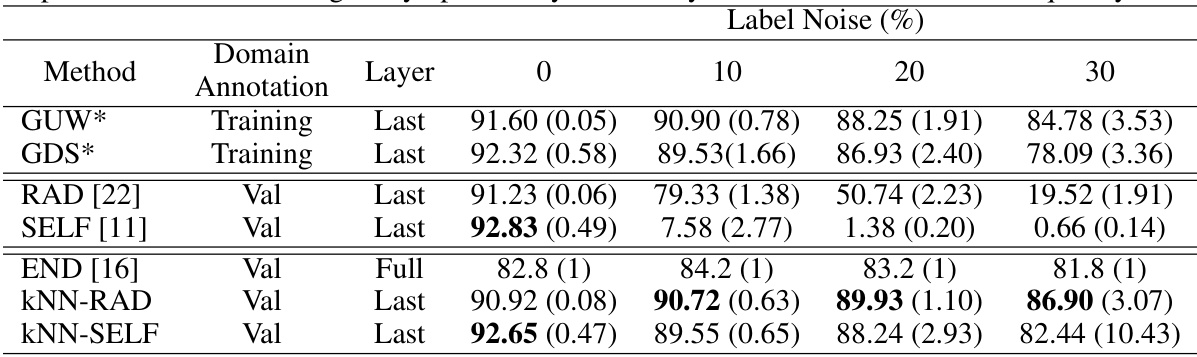

This table shows the worst-group accuracy (WGA) for different methods on the CMNIST dataset under various levels of symmetric label noise. It compares methods with and without access to clean domain labels, highlighting the robustness of kNN-enhanced approaches. Note that the END method is not included because it was not tested on the CMNIST dataset in the original paper.

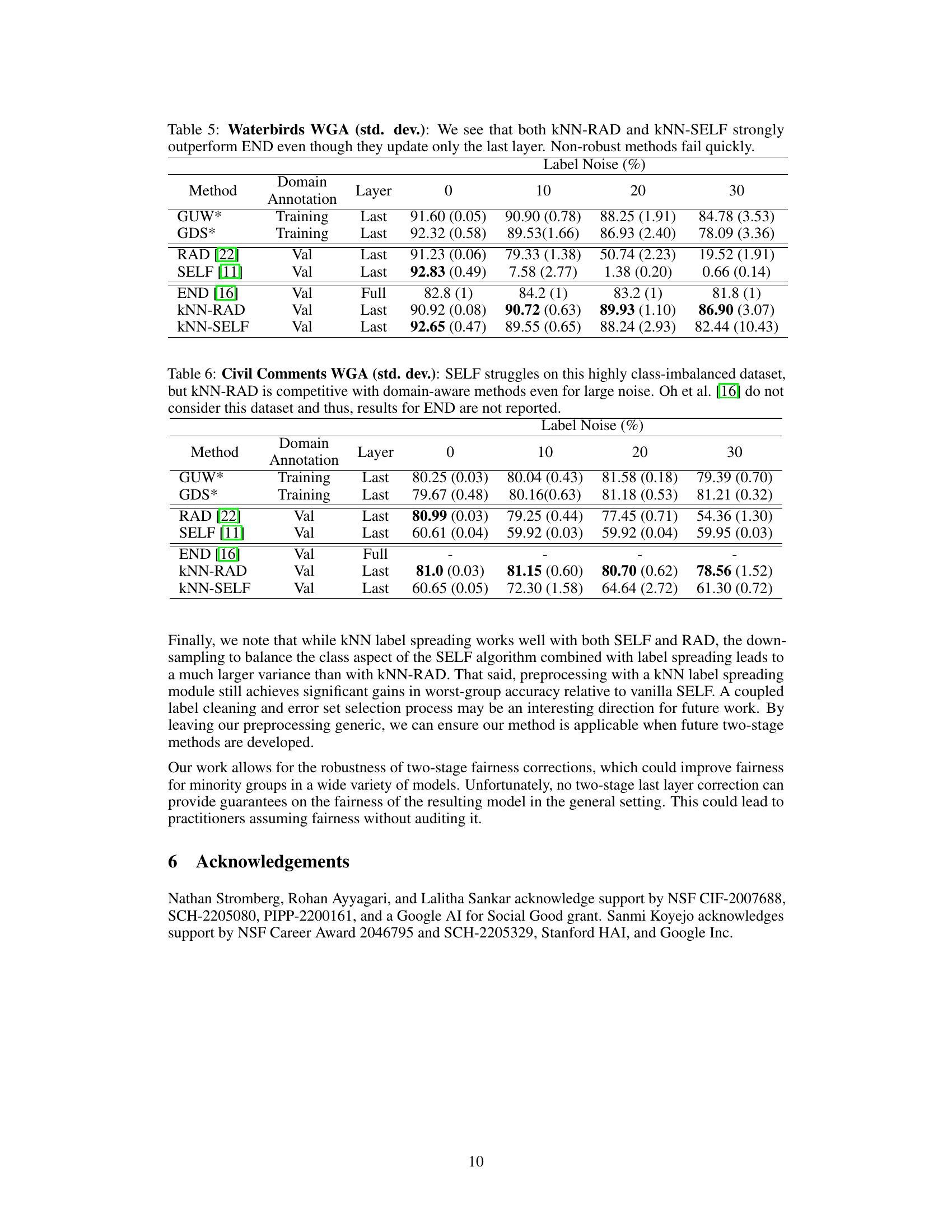

This table compares the worst-group accuracy (WGA) of different methods for correcting model bias on the CelebA dataset under various levels of symmetric label noise. The methods compared include standard two-stage techniques (RAD, SELF), a robust full retraining method (END), and the proposed kNN-enhanced versions of RAD and SELF (kNN-RAD, kNN-SELF). The results demonstrate the superior robustness of the kNN-enhanced methods to label noise, particularly kNN-RAD, outperforming other methods even with high noise levels (up to 30%).

This table compares the worst-group accuracy (WGA) of different fairness-enhancing methods on the CelebA dataset under varying levels of symmetric label noise. It shows the performance of standard methods (GUW*, GDS*, RAD, SELF, END) and the proposed methods (KNN-RAD, KNN-SELF). The results demonstrate that the proposed kNN label spreading pre-processing step significantly improves the robustness of both RAD and SELF to label noise, achieving state-of-the-art performance at higher noise levels.

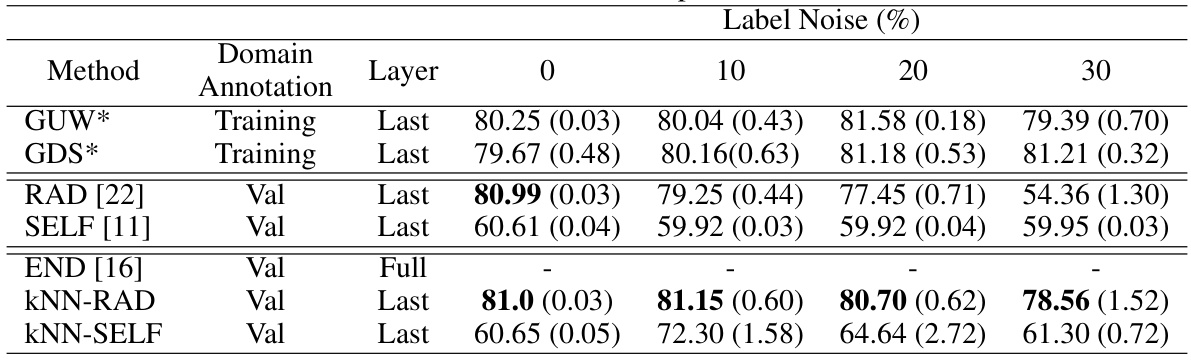

This table shows the worst-group accuracy (WGA) for different methods on the Civil Comments dataset with varying levels of label noise. It compares the performance of kNN-RAD and kNN-SELF against other state-of-the-art methods, including those that require domain annotations. The table highlights that KNN-RAD is robust to noisy labels and achieves comparable results to methods that use domain information, unlike SELF which struggles with this imbalanced dataset.

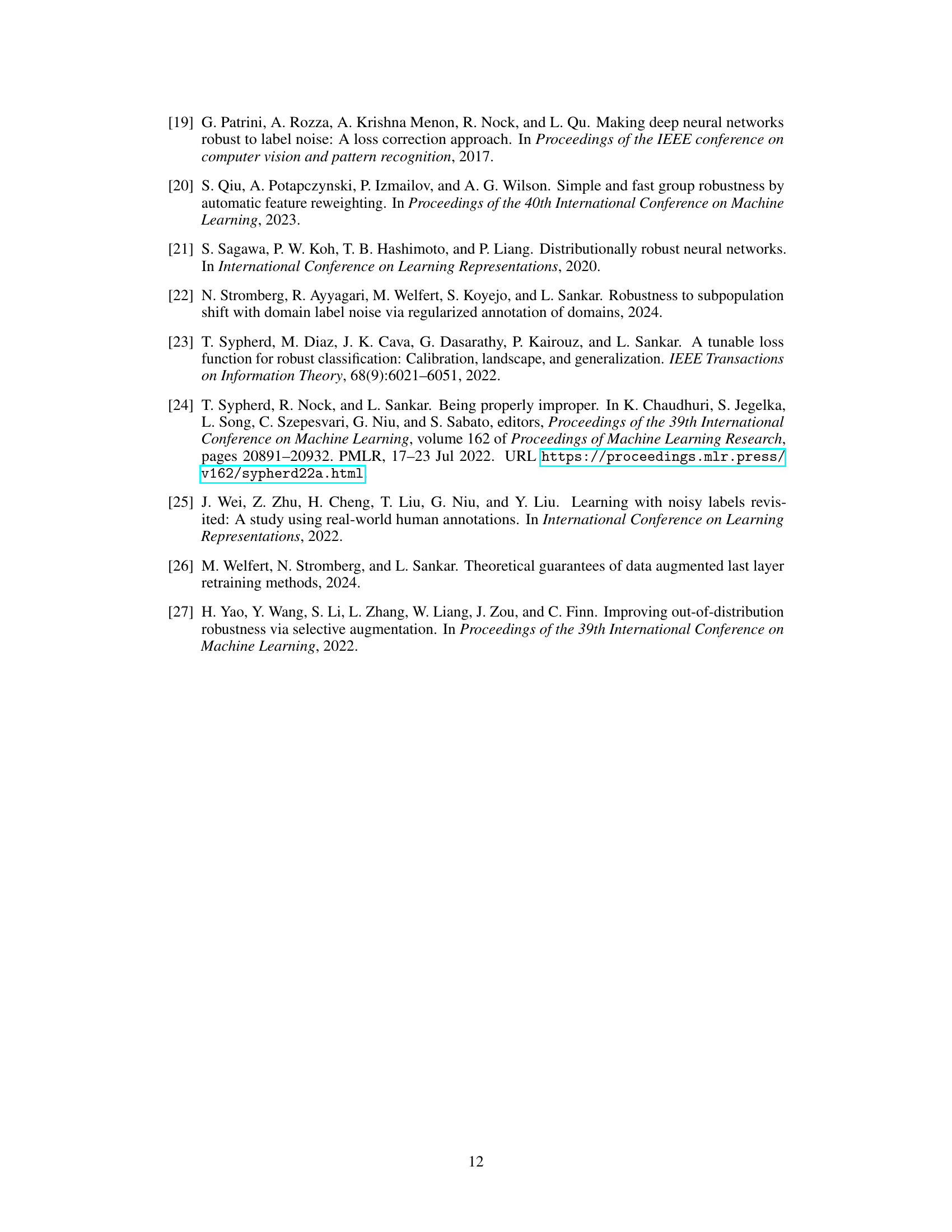

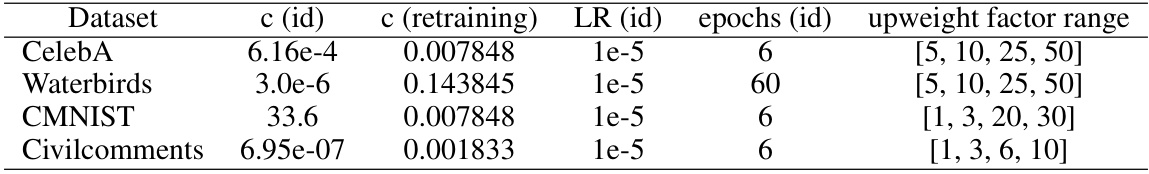

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the RAD algorithm across four different datasets: CelebA, Waterbirds, CMNIST, and CivilComments. For each dataset, it lists the penalty factor for the identification model (c (id)), the penalty factor for the retraining model (c (retraining)), the learning rate for the identification model (LR (id)), the number of epochs used for training the identification model (epochs (id)), and the range of upweight factors explored during hyperparameter tuning (upweight factor range). These hyperparameters were tuned to optimize the performance of the RAD algorithm on each dataset.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the KNN-RAD algorithm, including the penalty factors for identification and retraining models, learning rate, number of epochs, range of nearest neighbors, and range of upweight factors for four different datasets: CelebA, Waterbirds, CMNIST, and Civilcomments. The hyperparameter ranges were used in the hyperparameter selection phase of the experiments.

This table presents the hyperparameters used for the SELF algorithm across four different datasets: CelebA, Waterbirds, CMNIST, and CivilComments. For each dataset, it shows the number of fine-tuning steps, the range of learning rates explored, and the range of numbers of points considered for class balancing during the retraining process.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the KNN-SELF algorithm on each dataset. Specifically, it lists the number of fine-tuning steps, the learning rate range, the number of points used for reweighting, and the range of values tested for the number of nearest neighbors used in the KNN label-spreading preprocessing step.

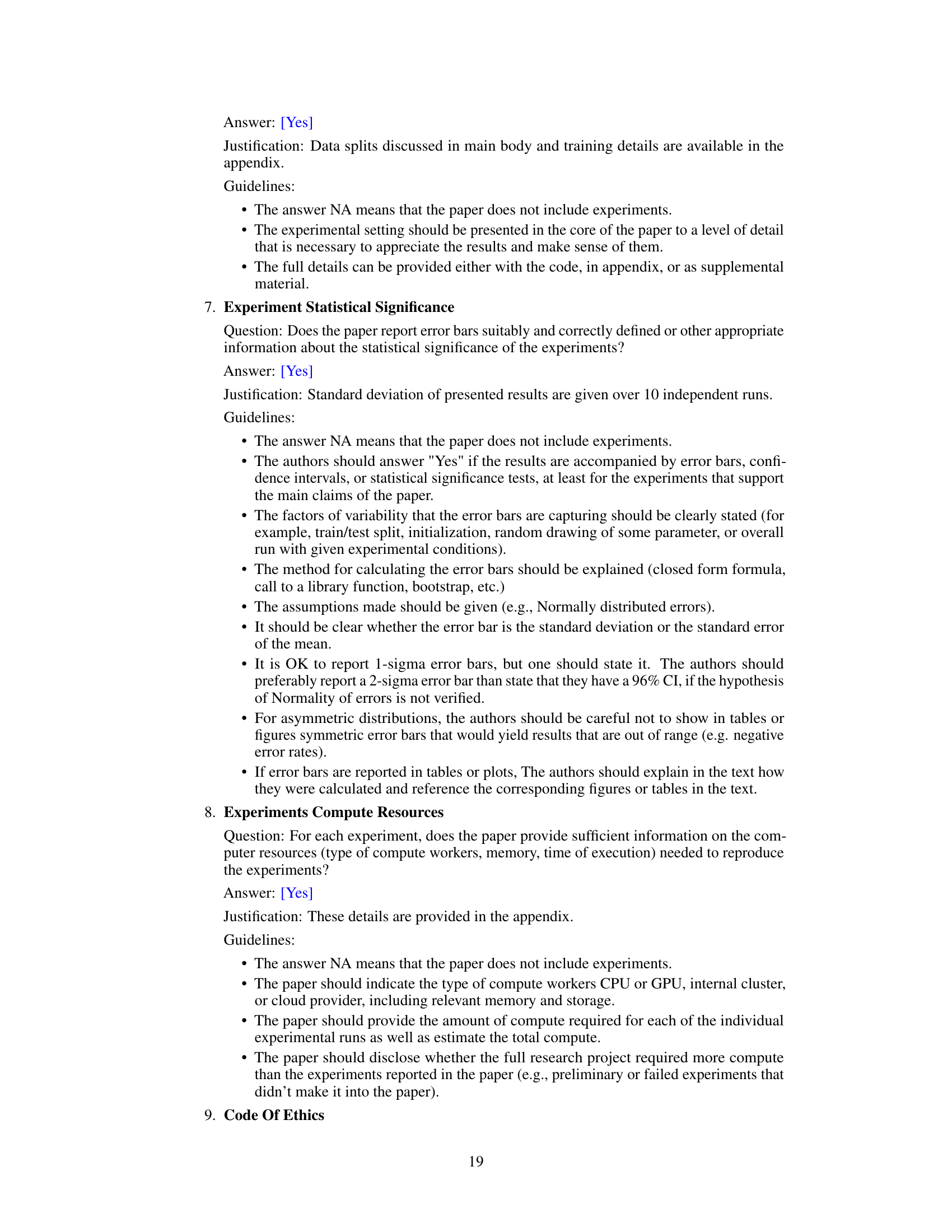

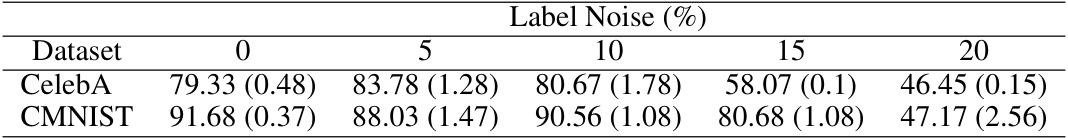

This table shows the worst-group accuracy (WGA) of the a-RAD model on CelebA and CMNIST datasets under different levels of symmetric label noise (SLN). The a-RAD model uses the alpha-loss function, which is designed to be robust to label noise. The table shows that the a-RAD model’s performance degrades significantly as the noise level increases, indicating that using a robust loss function alone is not enough to make two-stage methods robust to label noise.

Full paper#