↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating causal effects is challenging; randomized trials are often costly or impossible, while observational studies suffer from unmeasured confounding. Proxy experiments offer a middle ground but designing optimal (minimum-cost) ones is NP-complete, posing computational challenges. This is addressed by providing faster algorithms and reformulating the problem as a weighted maximum satisfiability and integer linear programming problem. These reformulations allow for more efficient algorithms that scale well with the number of variables, unlike previous approaches which require solving exponentially many NP-hard problems.

The research also investigates the problem of designing experiments that identify causal effects through valid adjustment sets. This is important because adjustment sets provide an easier and more interpretable way to identify causal effects. The authors propose a polynomial-time heuristic algorithm for this problem which outperforms previous approaches. Extensive simulations confirm that the new algorithms significantly improve upon the state-of-the-art, enabling more efficient and cost-effective causal inference studies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in causal inference and related fields. It tackles the computationally hard problem of designing cost-effective proxy experiments for causal effect identification. By providing efficient algorithms and reformulations, it directly impacts the design and analysis of real-world studies where direct experimentation is costly or impossible. The work also opens avenues for research into valid adjustment sets, enhancing the applicability of causal inference methodologies.

Visual Insights#

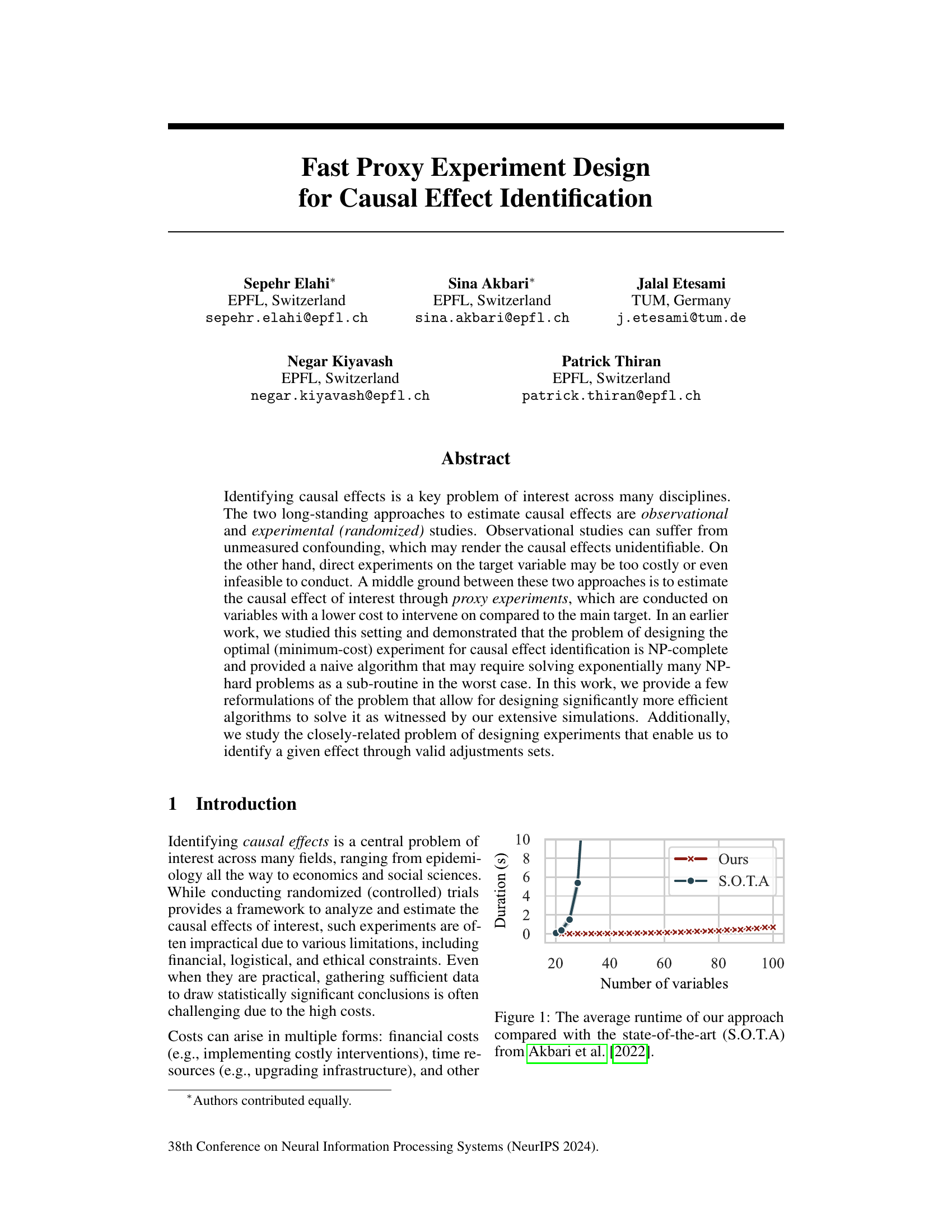

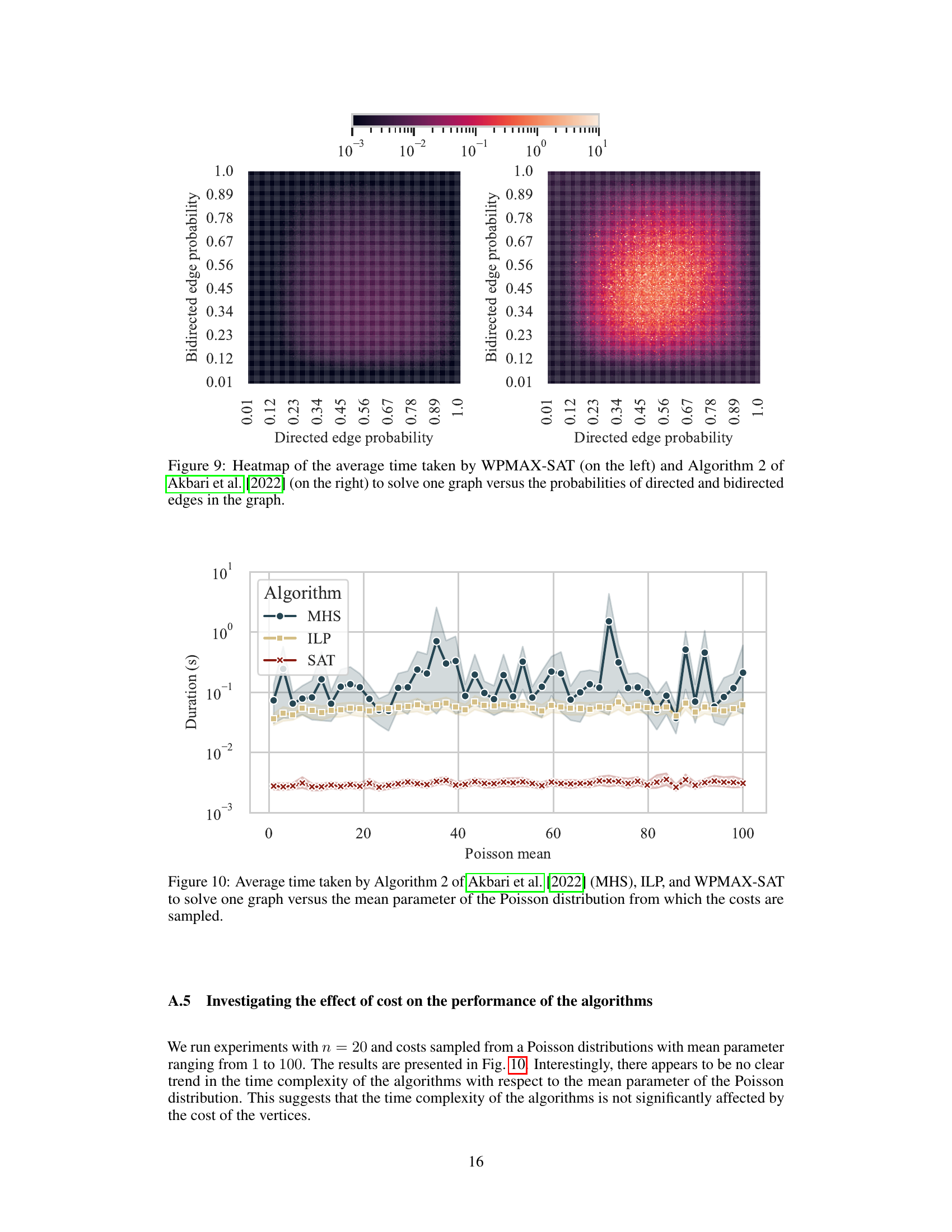

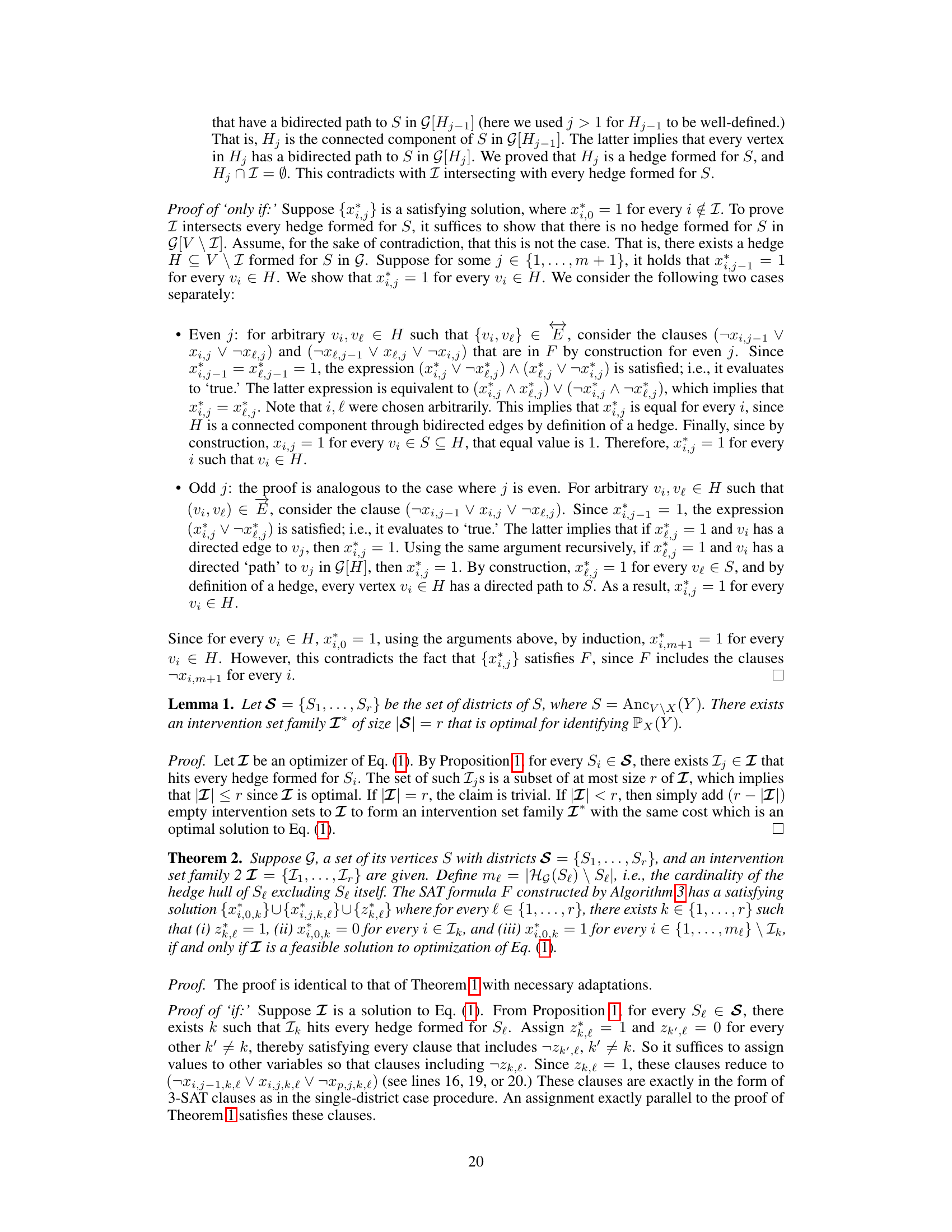

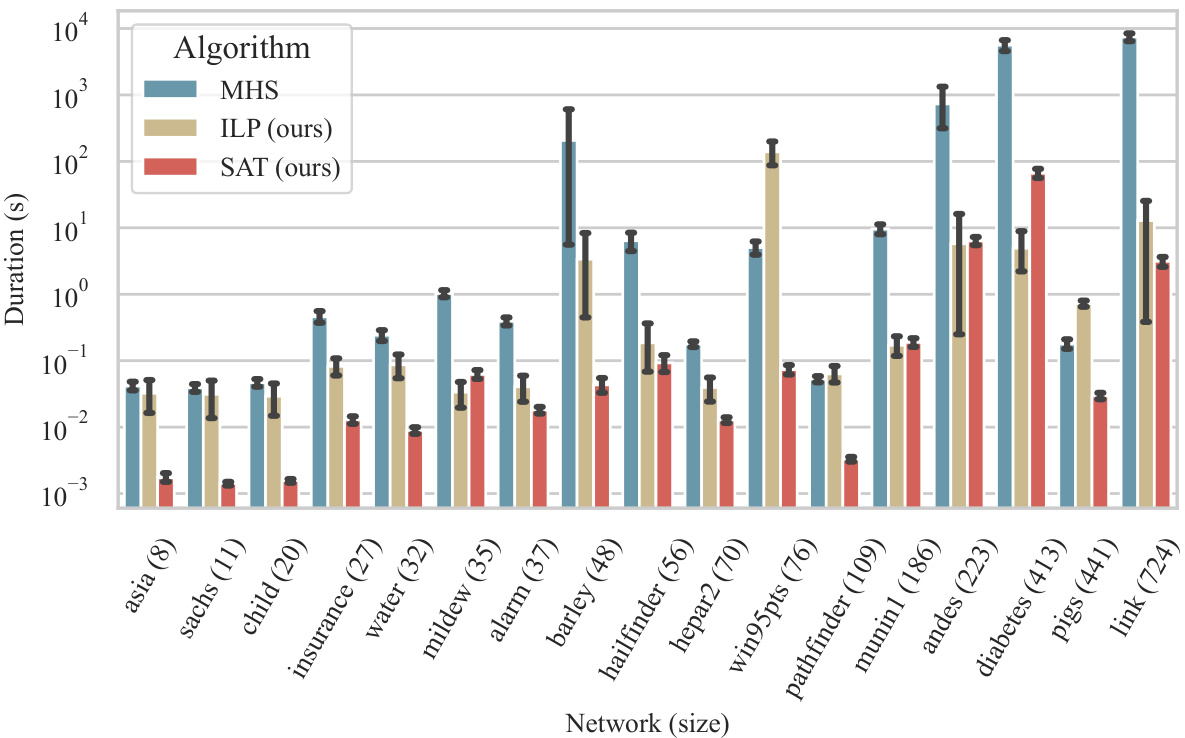

The figure shows a plot of the average runtime of the proposed approach and the state-of-the-art (SOTA) method from Akbari et al. [2022] against the number of variables. The x-axis represents the number of variables, and the y-axis represents the duration in seconds. It visually demonstrates that the proposed approach significantly outperforms the SOTA method in terms of runtime, especially as the number of variables increases.

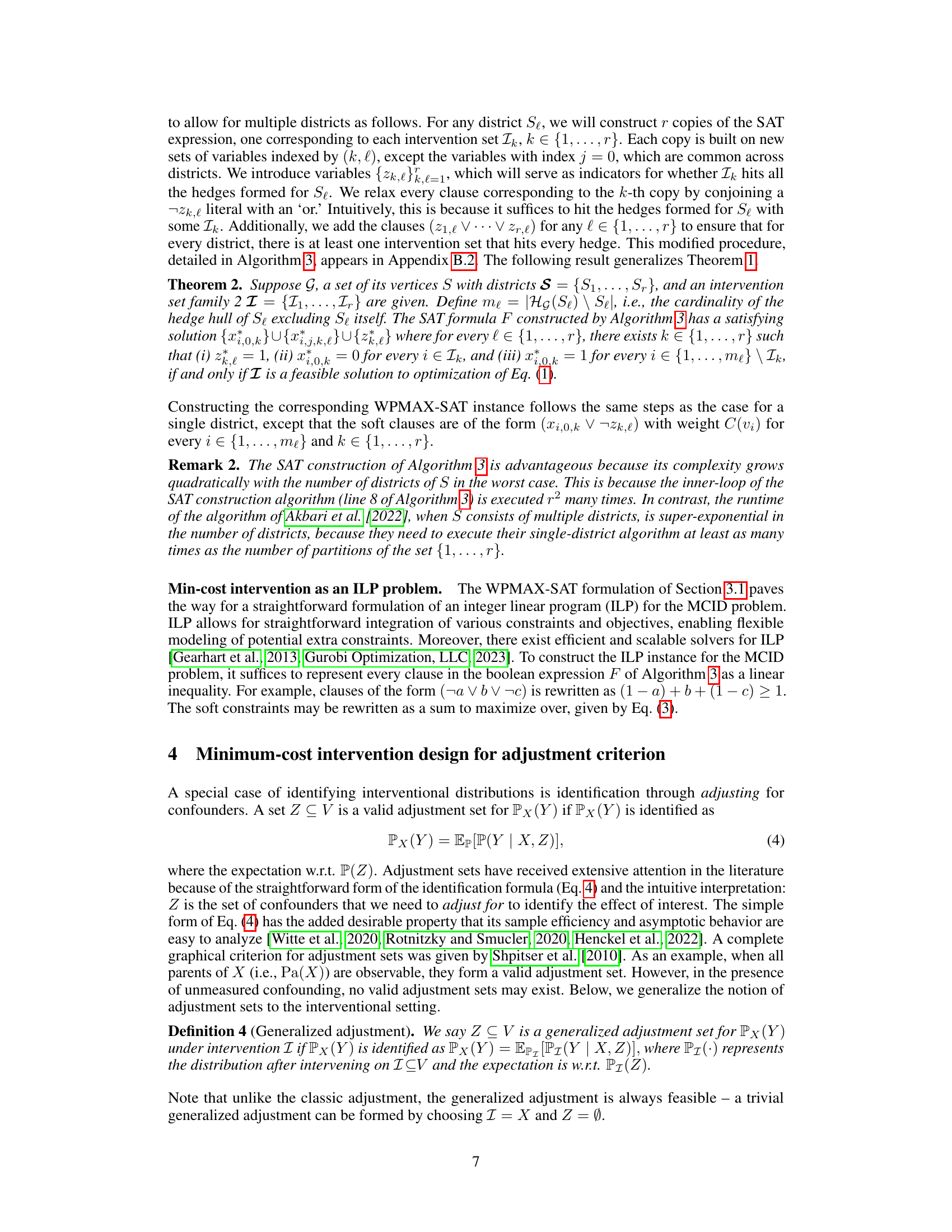

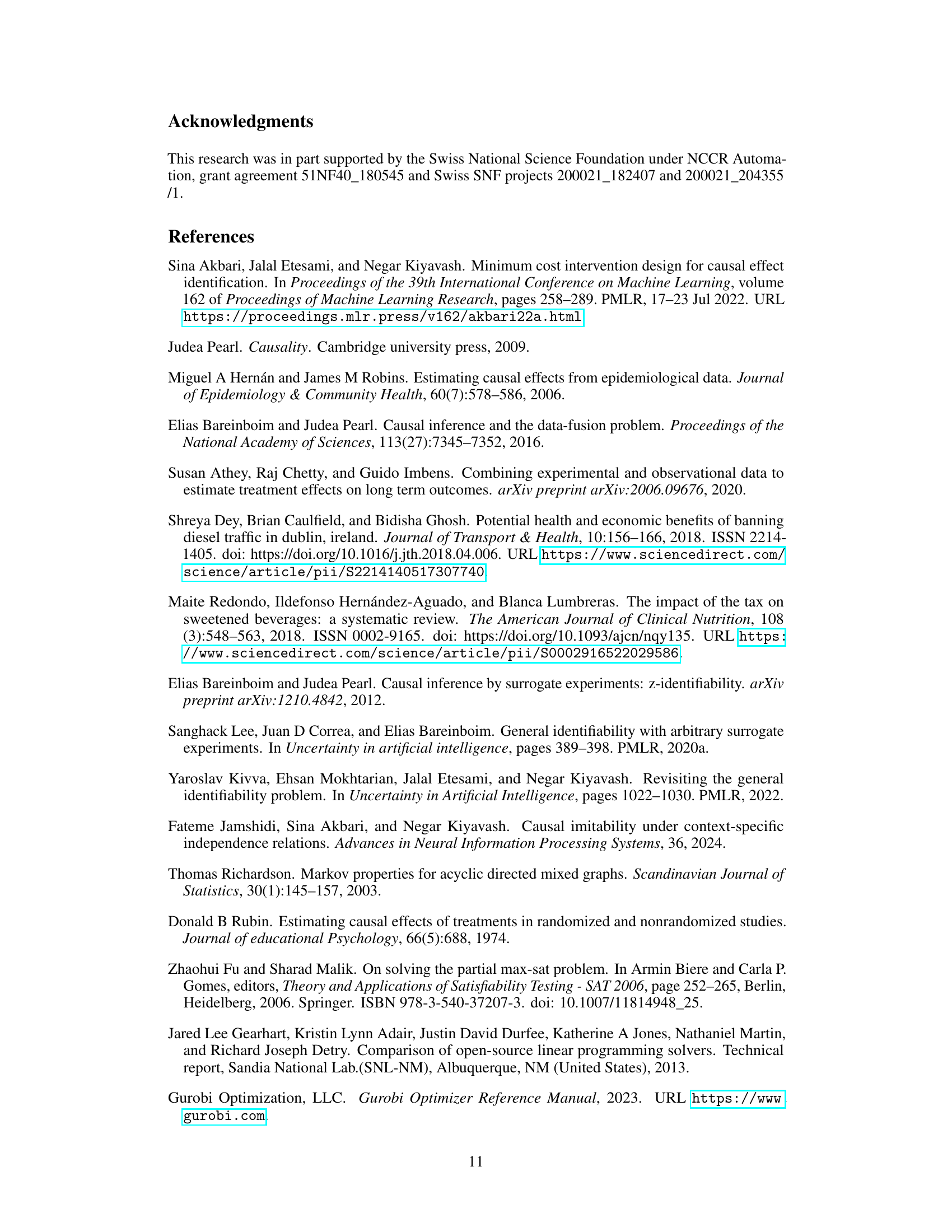

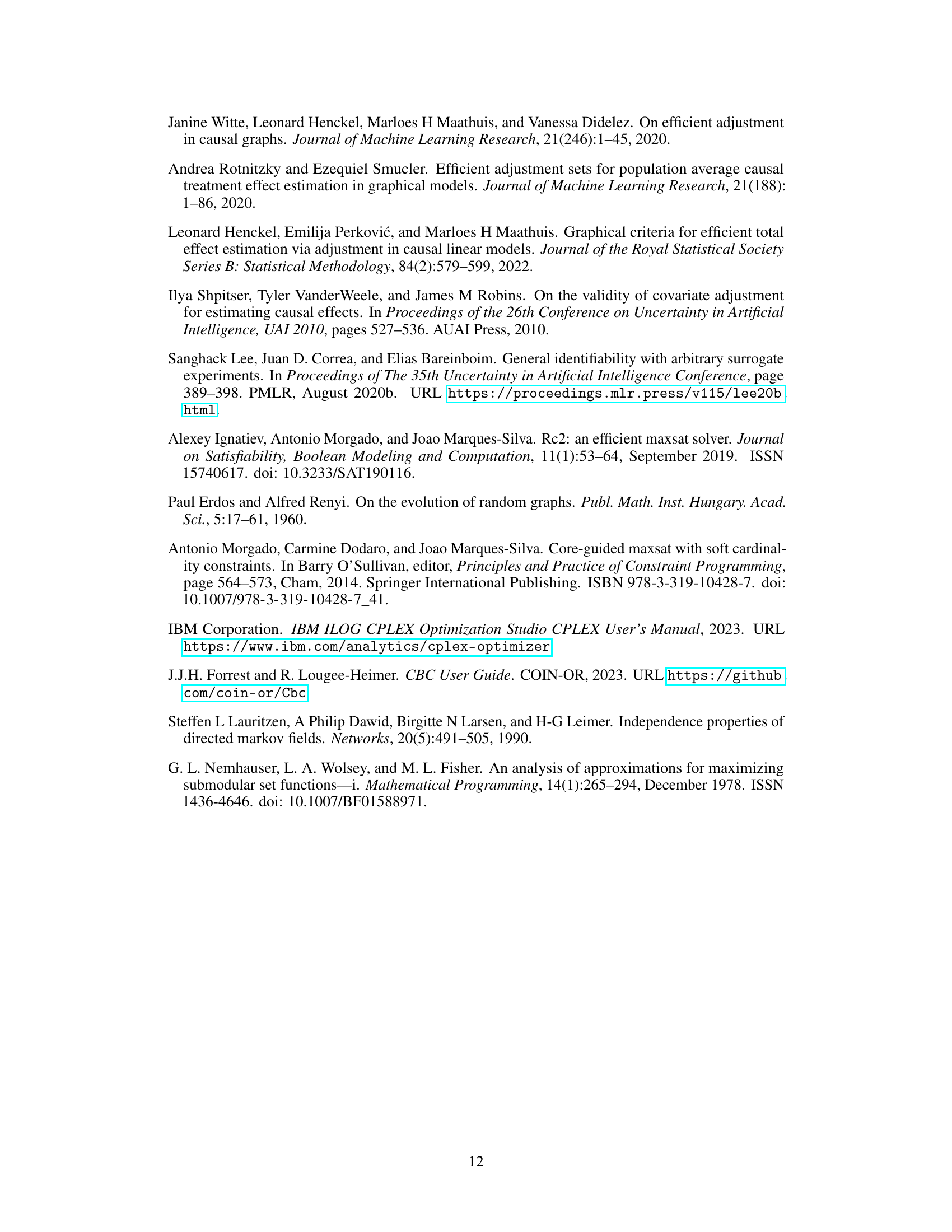

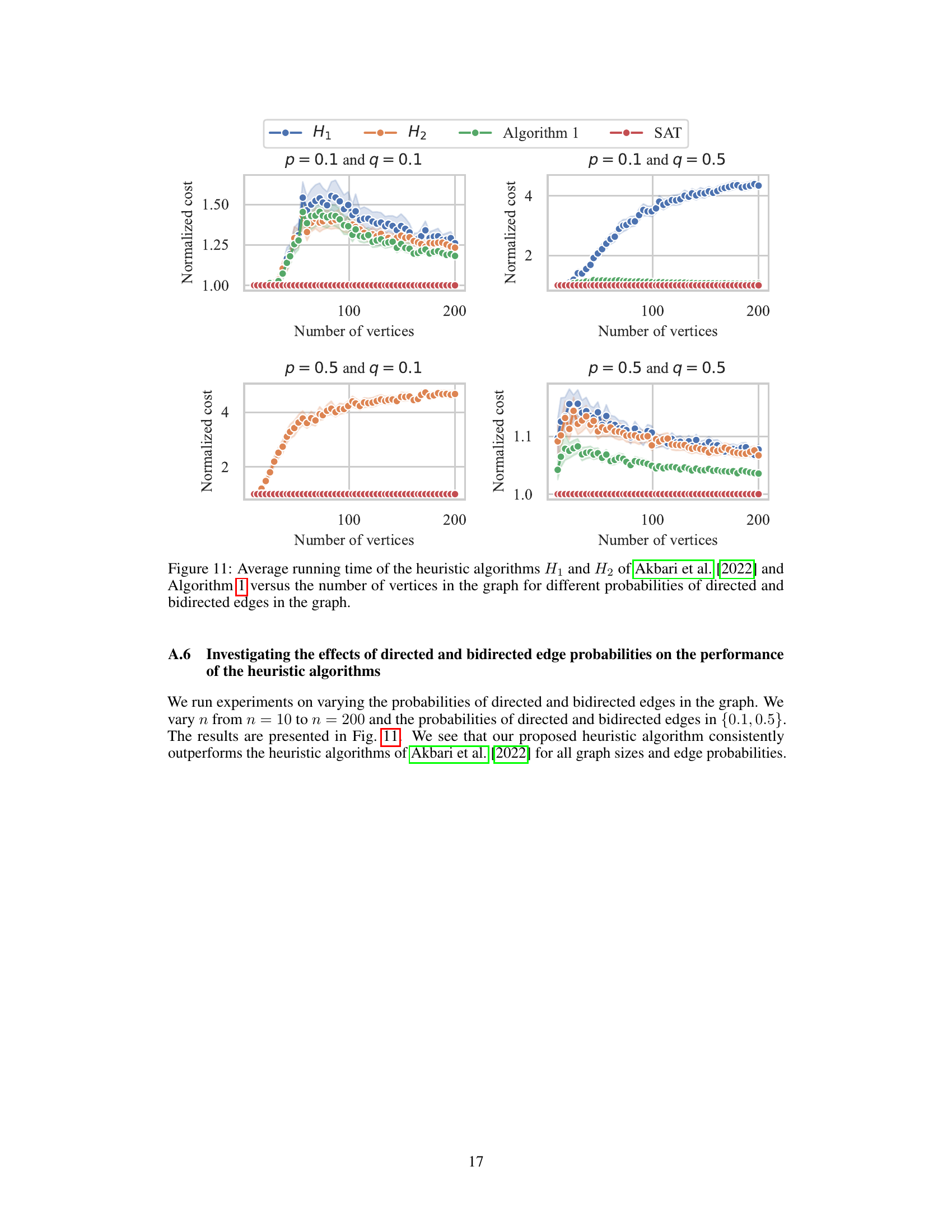

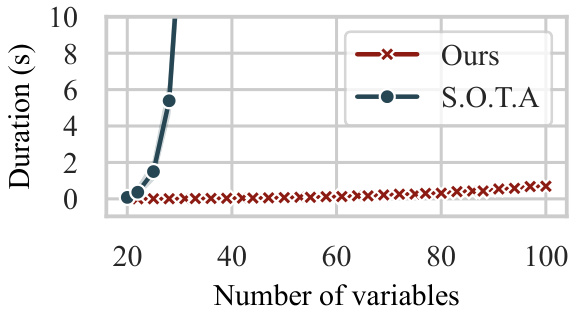

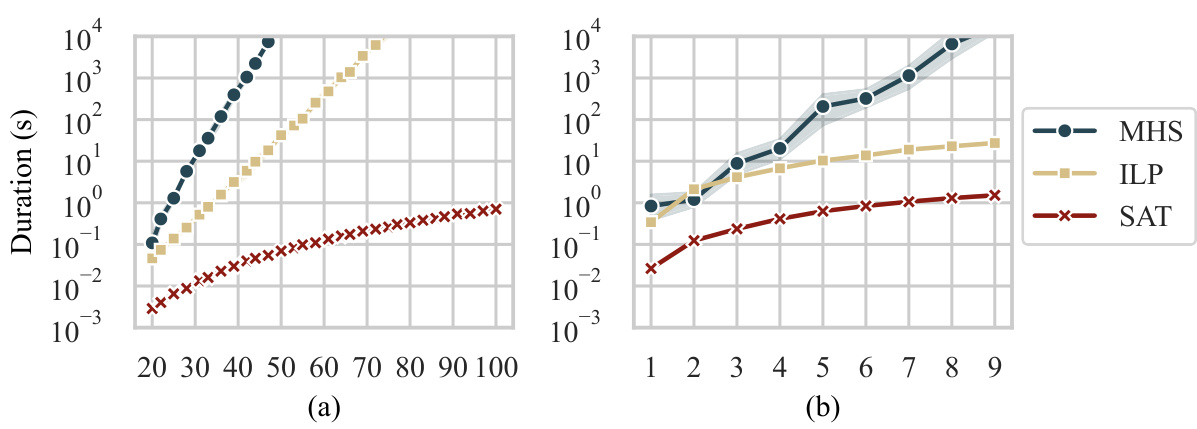

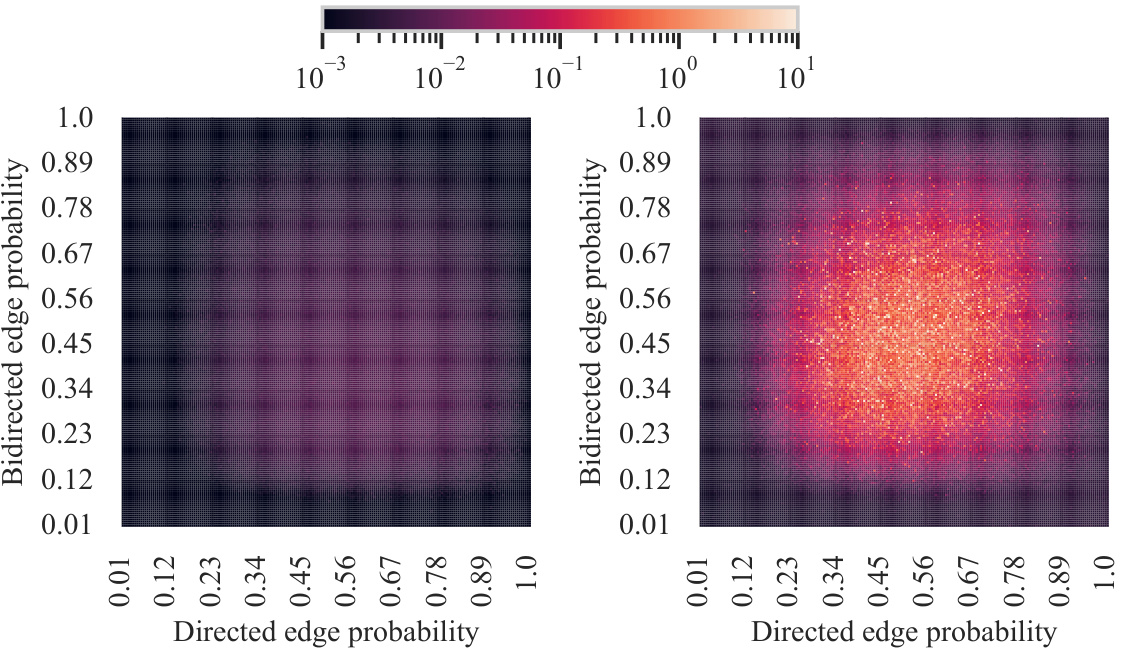

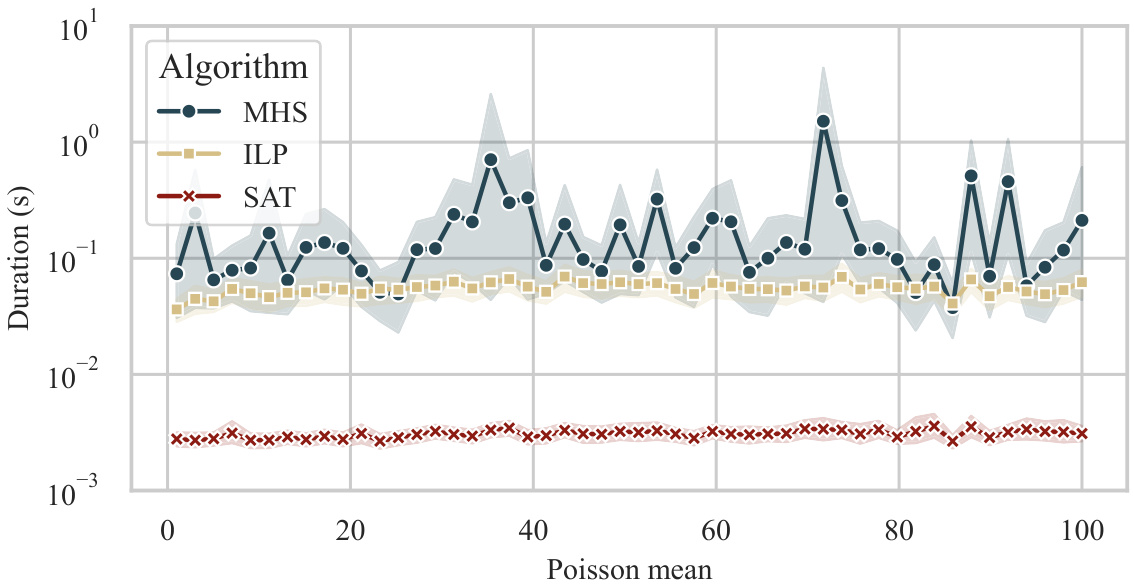

This figure compares the average runtime of three algorithms for solving the minimum-cost intervention problem: the algorithm from Akbari et al. [2022] (MHS), an Integer Linear Programming (ILP) formulation, and a Weighted Partially Max-SAT (WPMAX-SAT) formulation. Part (a) shows the runtime scaling with the number of vertices in the graph for a single district (S), while part (b) illustrates the runtime scaling with the number of districts for graphs with 20 vertices. The results demonstrate the significantly improved efficiency of the ILP and WPMAX-SAT methods compared to the MHS approach, particularly as the problem size increases.

In-depth insights#

Causal Effect ID#

Causal effect identification (Causal Effect ID) is a core challenge across many fields. The paper explores proxy experiments as a cost-effective middle ground between impractical direct experimentation and unreliable observational studies. A key contribution is the reformulation of the minimum-cost intervention design problem (MCID) into more tractable forms such as WPMAX-SAT and ILP, enabling significantly more efficient algorithmic solutions than prior state-of-the-art approaches. The work also addresses the closely related problem of designing experiments to identify causal effects via valid adjustment sets, proposing a polynomial-time heuristic algorithm that outperforms existing ones. Experimental results demonstrate substantial improvements in efficiency and speed, highlighting the practical impact of these novel methods. The focus on both exact and heuristic solutions caters to varying computational constraints and the need for both optimal and approximate solutions in practice. The exploration of the MCID problem across both single and multiple districts is another valuable aspect of this research.

Proxy Experiments#

Proxy experiments offer a powerful approach to causal inference when direct experimentation is infeasible or too costly. They involve intervening on more accessible variables (proxies) that are causally related to both the treatment and outcome of interest. Careful selection of proxies is crucial, as inappropriate choices can lead to biased or unidentifiable causal effects. The design of optimal proxy experiments often involves complex optimization problems, balancing the cost of intervention with the information gained about the target causal effect. This involves navigating the trade-off between cost and identifiability, which makes the design of efficient algorithms for proxy experiment design a significant challenge. Furthermore, the validity of proxy experiments depends heavily on the underlying causal assumptions and the accuracy of the causal model employed. Therefore, rigorous sensitivity analyses are essential to assess the robustness of inferences obtained from proxy experiments to violations of these assumptions. Successful implementation demands both sophisticated statistical techniques and a deep understanding of the causal relationships within the system.

Algorithm Reformulation#

The core of the algorithm reformulation section likely centers on addressing the computational intractability of the original minimum-cost intervention (MCI) problem. The authors probably demonstrate that the NP-complete nature of MCI necessitates a reformulation into more tractable problems. This reformulation might involve expressing the MCI problem as a weighted partially maximum satisfiability (WPMAX-SAT) problem or an integer linear programming (ILP) problem. The benefits of these reformulations are twofold: Firstly, they leverage existing, highly optimized solvers for WPMAX-SAT and ILP, circumventing the need for designing a novel algorithm from scratch. Secondly, the reformulated problems likely exhibit improved computational complexity, offering significantly better scalability. A key aspect is a comparative analysis of the runtime performance of the original algorithm versus the reformulated approaches, showing substantial improvements in computational efficiency. The authors may also explore other reformulations, such as submodular function maximization or reinforcement learning. The discussion of reformulations would ideally demonstrate a trade-off between optimality and tractability, highlighting the effectiveness of the selected reformulations in solving realistically sized instances of the MCI problem.

Computational Efficiency#

The computational efficiency of causal effect identification methods is a critical concern, particularly when dealing with large datasets or complex causal graphs. This paper tackles this head-on by presenting novel reformulations of the minimum-cost intervention problem, transforming it into more tractable forms such as weighted partial MAX-SAT and integer linear programming. These reformulations enable the development of significantly faster algorithms, improving upon existing approaches by up to six orders of magnitude. The superiority of the proposed algorithms is empirically validated through extensive numerical experiments. This significant speedup is crucial for making causal inference feasible in many real-world scenarios. Furthermore, the authors also address the problem of designing experiments to identify effects through valid adjustment sets, exploring a closely related problem that allows for the development of a polynomial-time heuristic, further enhancing computational efficiency. The paper’s focus on algorithmic improvements, complemented by rigorous analysis and experimental results, makes a substantial contribution towards addressing the scalability challenge in causal inference.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more sophisticated cost models, moving beyond simple vertex costs to incorporate the complexities of real-world interventions. Investigating scalable approximation algorithms for the MCID problem is crucial, as exact solutions become computationally prohibitive for large graphs. A deeper exploration into different causal effect identification methods, beyond adjustments sets, and their integration with proxy experiments, would be valuable. Combining experimental and observational data more effectively within this framework could yield significant gains in causal inference accuracy. Finally, the development of user-friendly tools and software would facilitate broader adoption of this methodology across various disciplines.

More visual insights#

More on figures

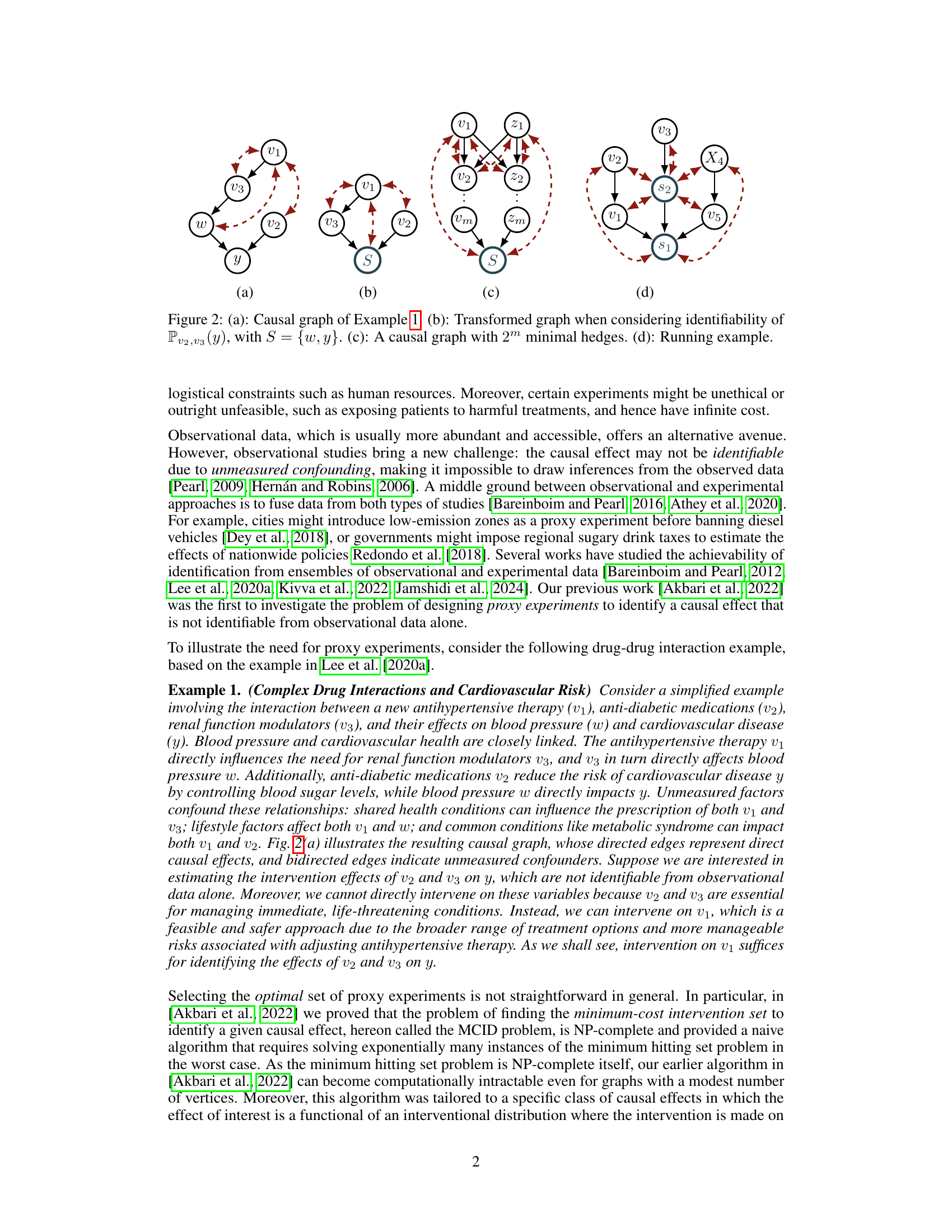

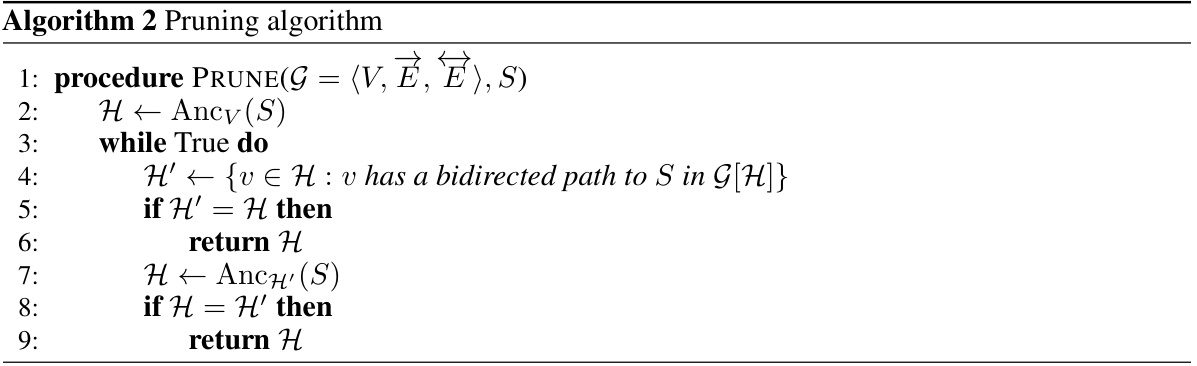

This figure presents four causal graphs illustrating different concepts related to causal effect identification. (a) shows a causal graph for Example 1 (a complex drug interaction example), illustrating the relationships between different drug therapies and their impact on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. (b) displays the transformed graph from (a), focusing on identifiability of effects given a specific intervention set. (c) is an example causal graph with many minimal hedges, highlighting the computational challenges of finding minimum interventions. Finally, (d) is another example of a causal graph illustrating the concepts discussed in the paper.

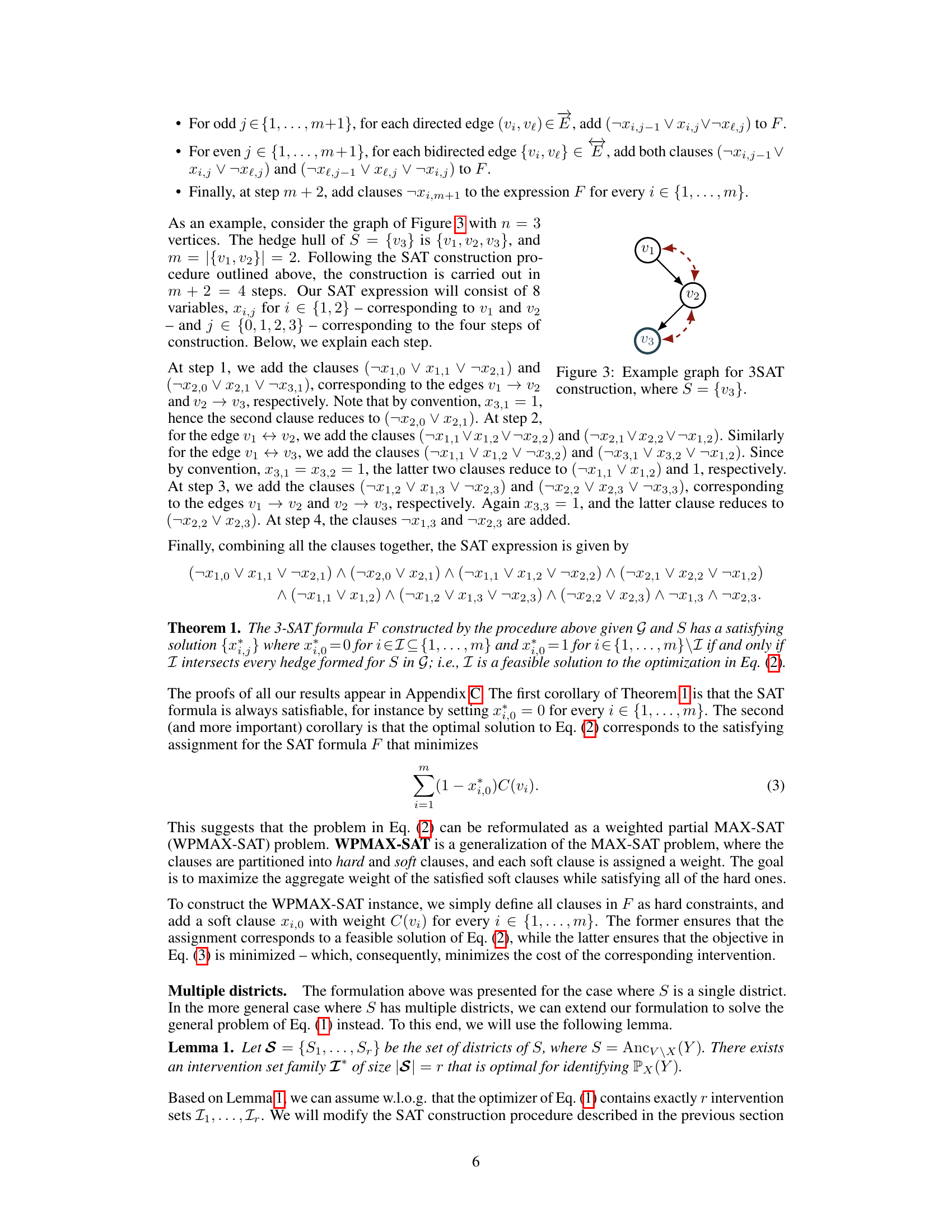

This figure shows a simple directed acyclic graph (DAG) with three vertices (v1, v2, v3) and three edges. There are two directed edges and one bidirected edge, with v3 designated as the set S. This graph serves as an example to illustrate the 3-SAT construction procedure for identifying the minimum-cost intervention set to identify a causal effect.

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms in solving the Minimum-Cost Intervention for Causal Effect Identification (MCID) problem. The x-axis of (a) represents the number of vertices in the causal graph, and the x-axis of (b) represents the number of districts within the graph. The y-axis of both graphs represents the average time (in seconds) taken to solve the MCID problem. The figure demonstrates that the ILP and WPMAX-SAT algorithms significantly outperform the MHS algorithm, especially as the problem size increases. The runtime of MHS grows exponentially with the number of both vertices and districts, while ILP and WPMAX-SAT show a more manageable growth in runtime.

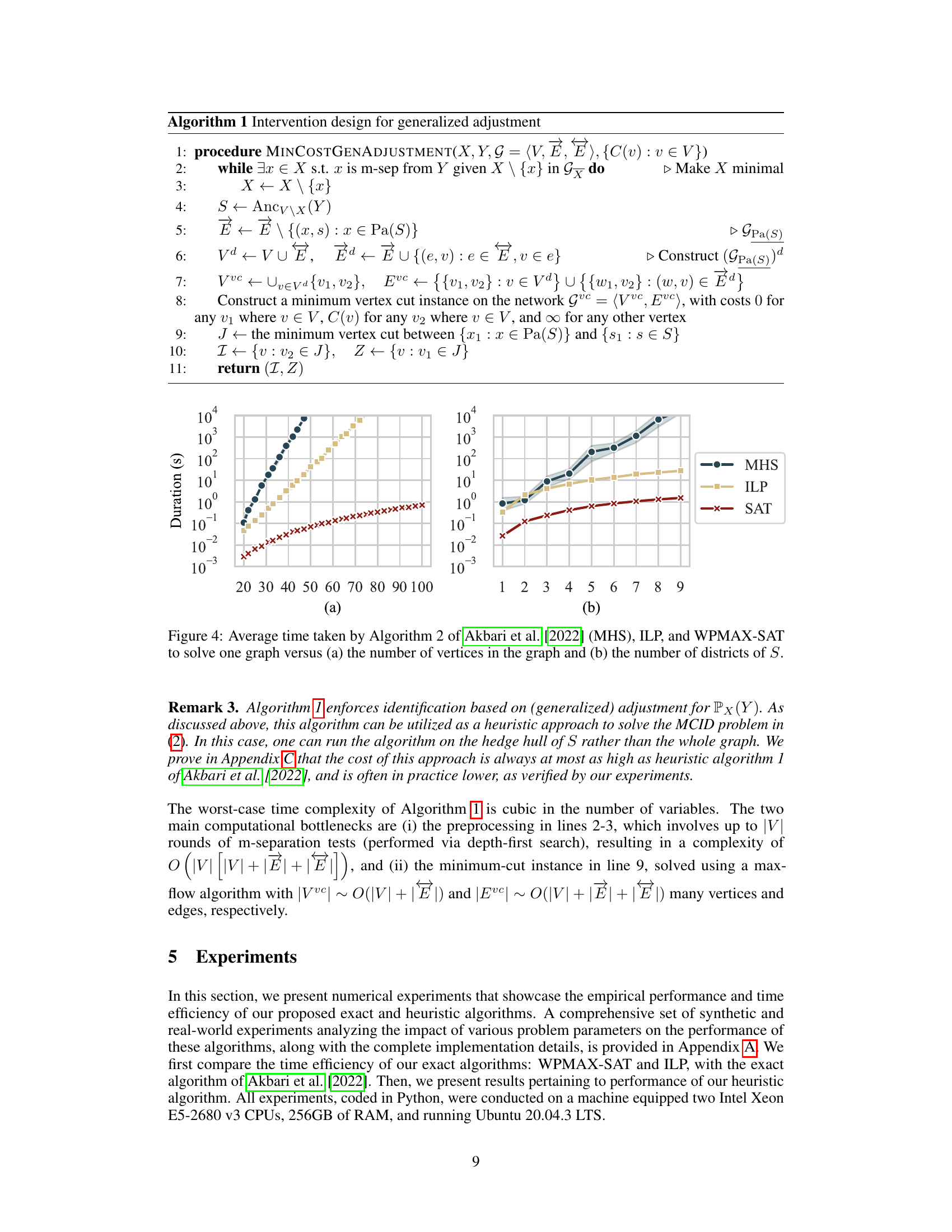

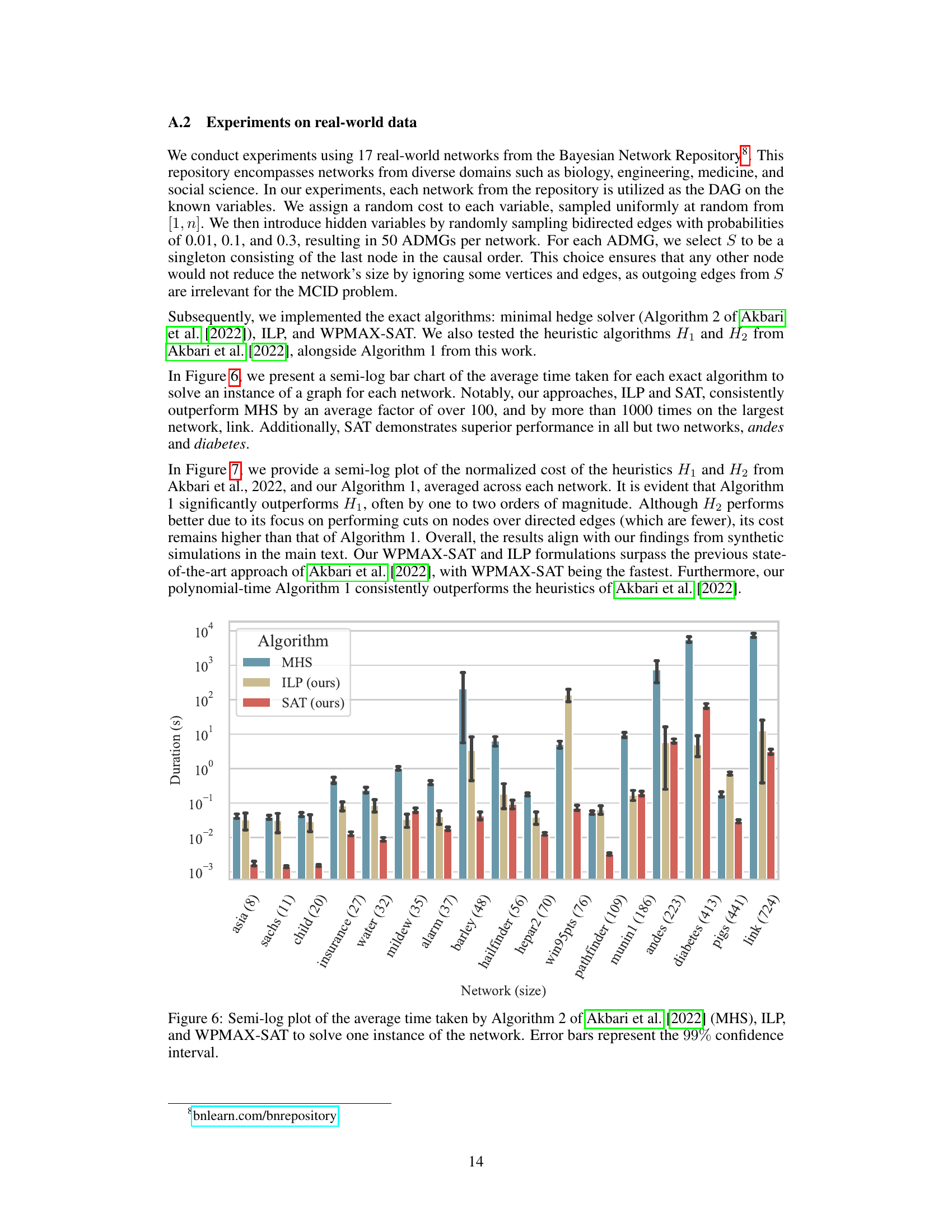

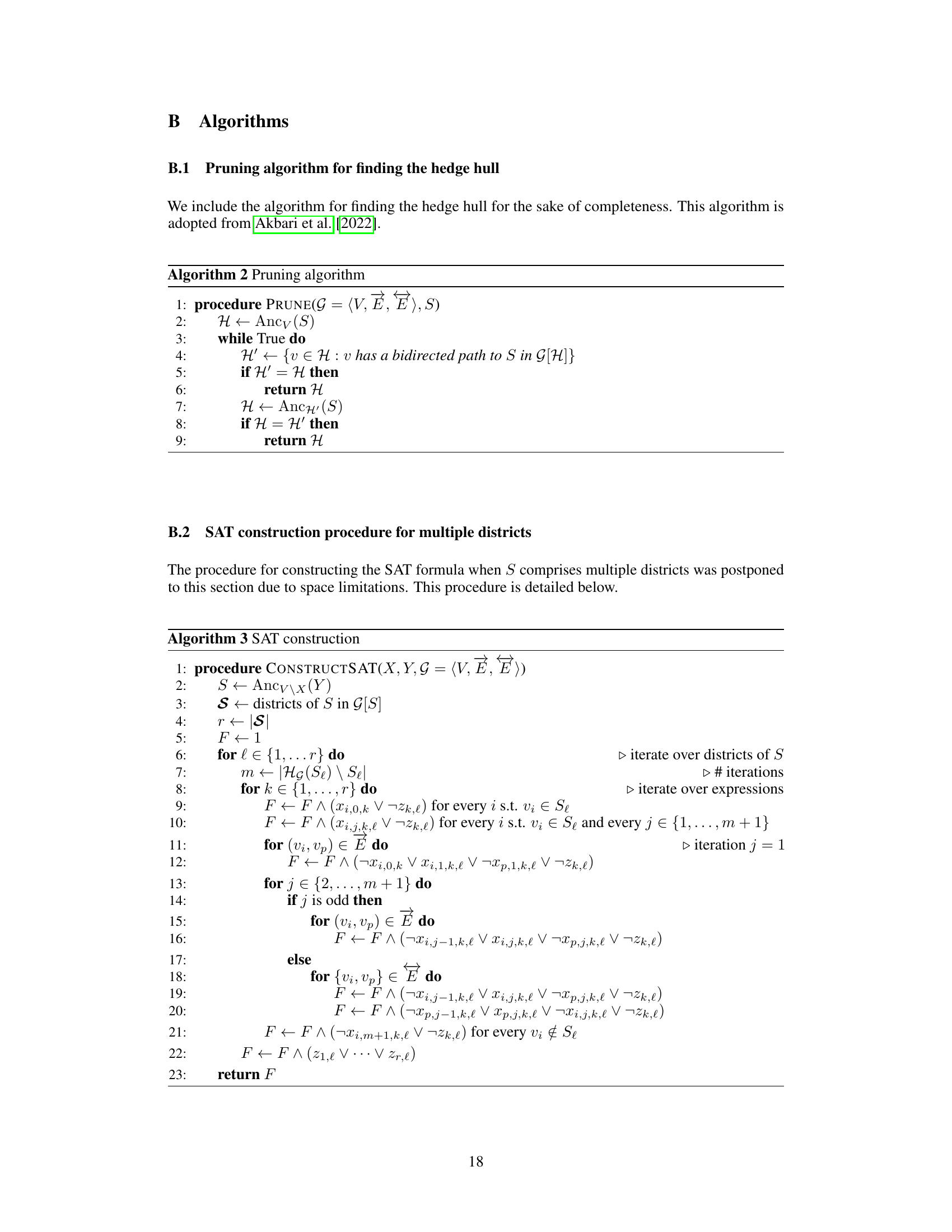

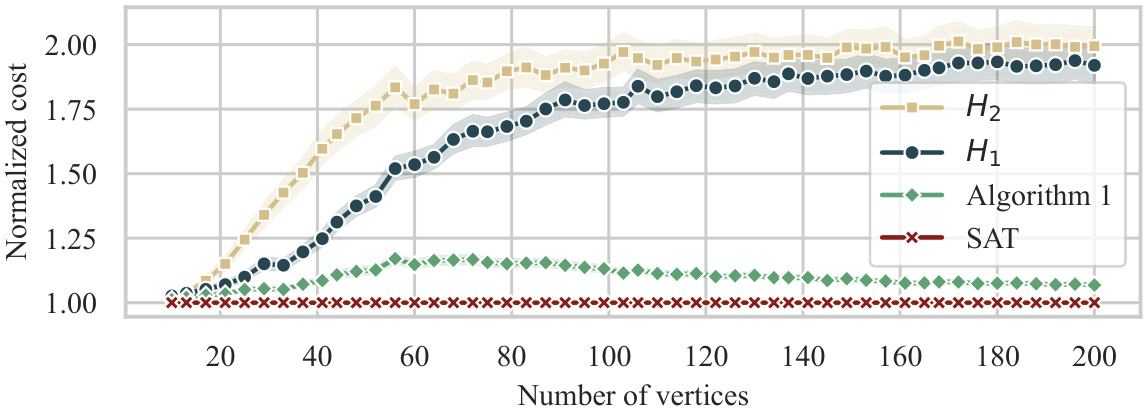

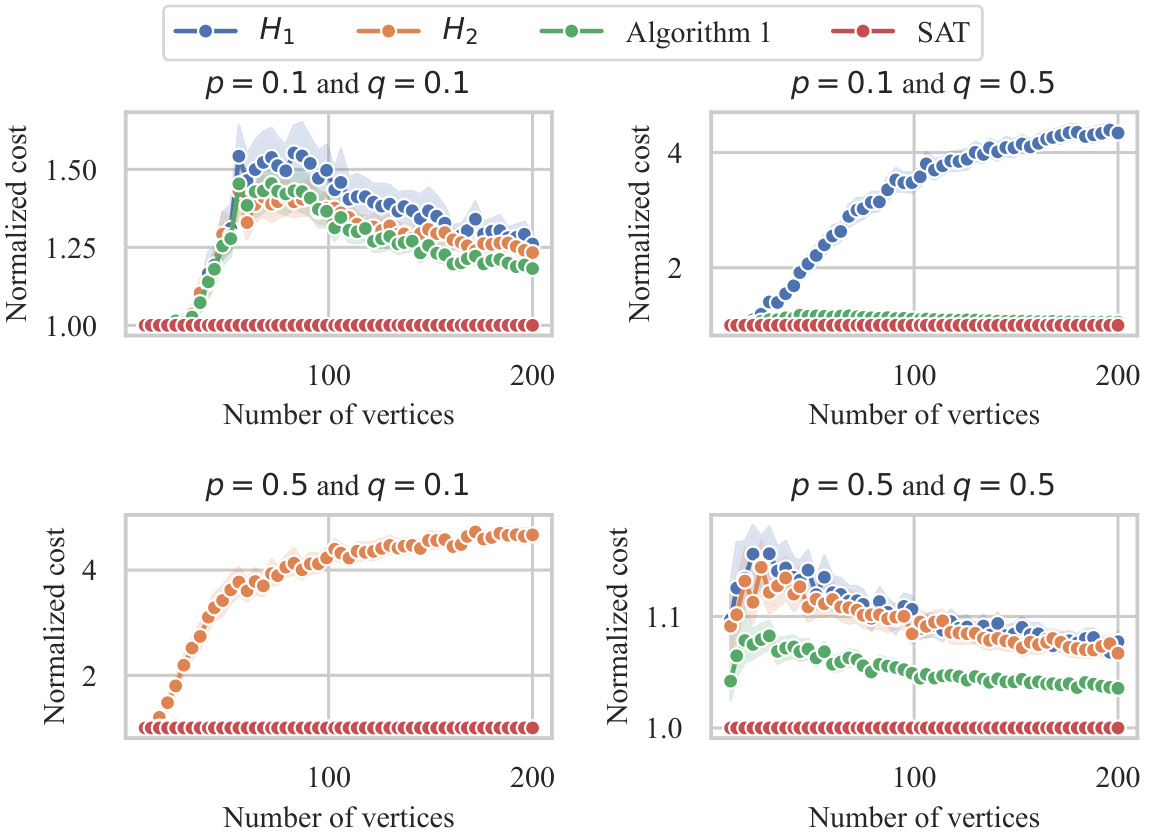

The figure shows the average normalized cost of four different algorithms (H1, H2, Algorithm 1, and SAT) for solving the minimum-cost intervention problem. The normalized cost is calculated by dividing the cost of each algorithm by the cost of the optimal solution. The x-axis represents the number of vertices in the graph, and the y-axis represents the normalized cost. The figure shows that Algorithm 1 and SAT consistently outperform H1 and H2, especially as the number of vertices increases.

This figure compares the time efficiency of three algorithms: the Minimal Hedge Solver (MHS) from Akbari et al. 2022, an Integer Linear Programming (ILP) method, and a Weighted Partially Max-SAT (WPMAX-SAT) method. The comparison is done for two scenarios: (a) varying the number of vertices in the graph while keeping the number of districts constant; and (b) keeping the number of vertices fixed while changing the number of districts. The results show that the ILP and WPMAX-SAT methods are significantly faster than the MHS algorithm, especially when the number of districts increases.

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms in solving the minimum-cost intervention problem for causal effect identification. The x-axis of (a) shows the number of vertices in the causal graph, while the x-axis of (b) shows the number of districts (subsets of variables with unmeasured confounders). The y-axis represents the average runtime in seconds. The results demonstrate that the ILP and WPMAX-SAT algorithms significantly outperform the MHS algorithm, especially as the problem size increases (more vertices or districts). The improvement is more pronounced in the multiple-district scenario.

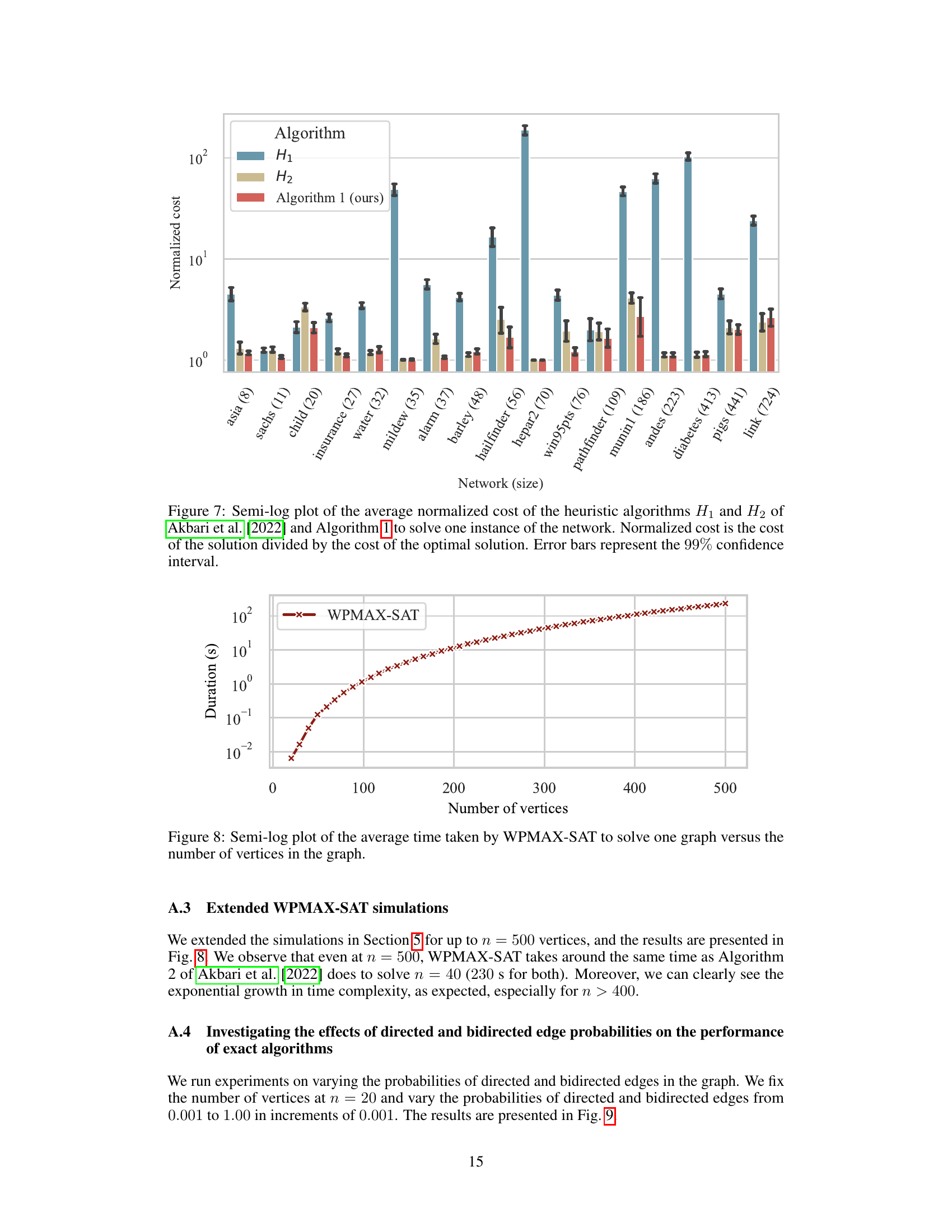

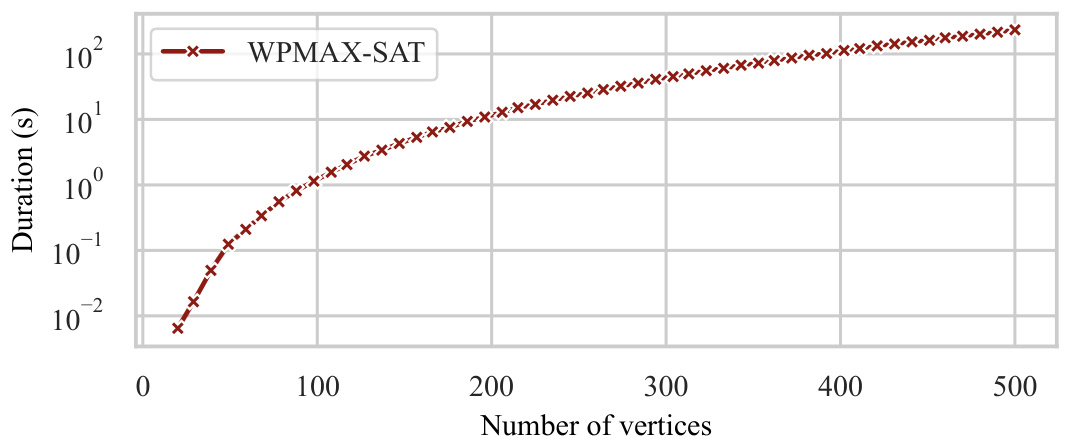

This figure shows the average runtime of the WPMAX-SAT algorithm for solving the minimum-cost intervention problem (MCID) as the number of vertices in the causal graph increases. The x-axis represents the number of vertices, and the y-axis represents the runtime in seconds. The plot shows an exponential increase in runtime as the number of vertices grows, indicating the computational complexity of the problem.

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms for solving the minimum-cost intervention problem in causal inference. The algorithms are the minimal hedge solver (MHS) from Akbari et al. (2022), an integer linear program (ILP), and a weighted partially maximum satisfiability problem (WPMAX-SAT). The plot shows the average runtime of each algorithm as a function of the number of variables (vertices) in the causal graph and the number of districts. The results demonstrate a significant speed advantage for the ILP and WPMAX-SAT algorithms compared to the MHS algorithm, particularly as the problem size increases. The WPMAX-SAT algorithm is considerably faster in most cases.

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms in solving the Minimum-Cost Intervention for Causal Effect Identification (MCID) problem. The algorithms are: the Minimal Hedge Solver (MHS) from Akbari et al. [2022], an Integer Linear Programming (ILP) approach, and a Weighted Partially Maximum Satisfiability (WPMAX-SAT) approach. The comparison is shown using two subfigures. Subfigure (a) plots the average runtime versus the number of vertices in the graph, showing that the WPMAX-SAT is significantly faster. Subfigure (b) plots the average runtime versus the number of districts in S, indicating that both ILP and WPMAX-SAT show better scaling compared to MHS.

This figure compares the average runtime of the proposed approach with the state-of-the-art (SOTA) method from Akbari et al. [2022] for solving the Minimum-Cost Intervention for Causal Effect Identification (MCID) problem. The x-axis represents the number of variables, and the y-axis represents the runtime in seconds. The graph shows that the proposed approach significantly outperforms the SOTA method, especially as the number of variables increases. This improvement in efficiency is a key contribution of the paper.

Full paper#