↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many applications require understanding macroscopic system behavior, often relying on computationally expensive microscopic simulations. Current methods demand computing forces on all microscopic coordinates, a significant hurdle for large systems. This study addresses this limitation by focusing on macroscopic properties directly, rather than relying on full microscopic detail.

The researchers propose a novel method that learns macroscopic dynamics using only partial microscopic force computations. This approach relies on a sparsity assumption; each microscopic force depends only on a few others. By mapping the training to the microscopic level and using partial forces as a stochastic estimate, the method updates model parameters efficiently. The paper demonstrates accuracy and efficiency gains through various simulations, showcasing its potential for modeling complex systems more effectively.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel method to learn macroscopic dynamics from partial microscopic observations, significantly reducing computational costs for large-scale systems. This is highly relevant to materials science, where macroscopic properties are crucial but their computation is expensive. The method’s efficiency and accuracy open new avenues for data-driven modeling of complex systems, and its theoretical justification provides a solid foundation for future research.

Visual Insights#

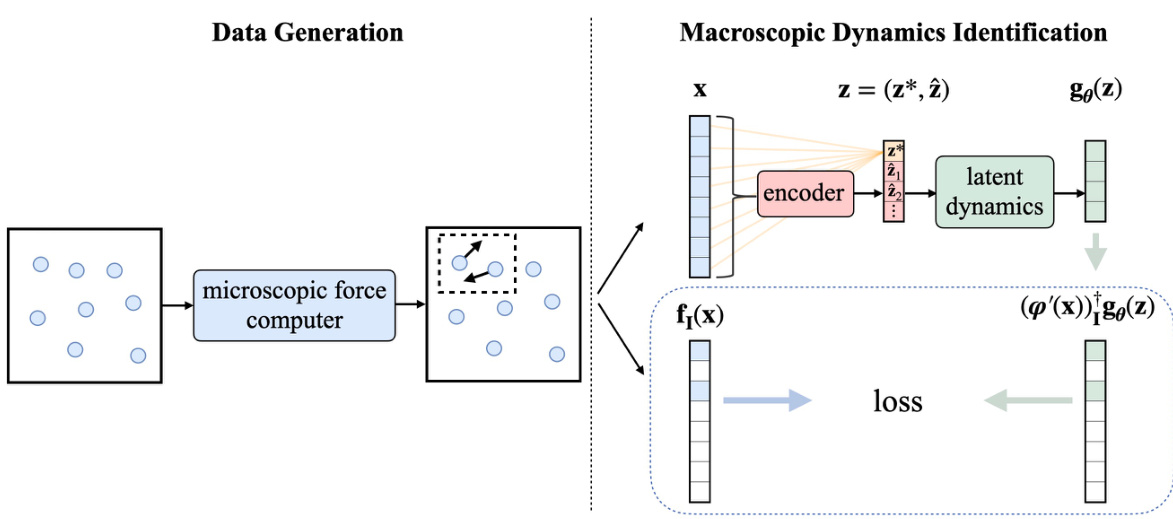

This figure illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed method. The left side shows the data generation process, where forces are computed on only a subset of microscopic coordinates to reduce computational cost. The right side illustrates the process of identifying macroscopic dynamics by mapping it back to the microscopic space and comparing it with the partially computed microscopic forces. The core idea is to learn the macroscopic dynamics without computing forces on all microscopic coordinates.

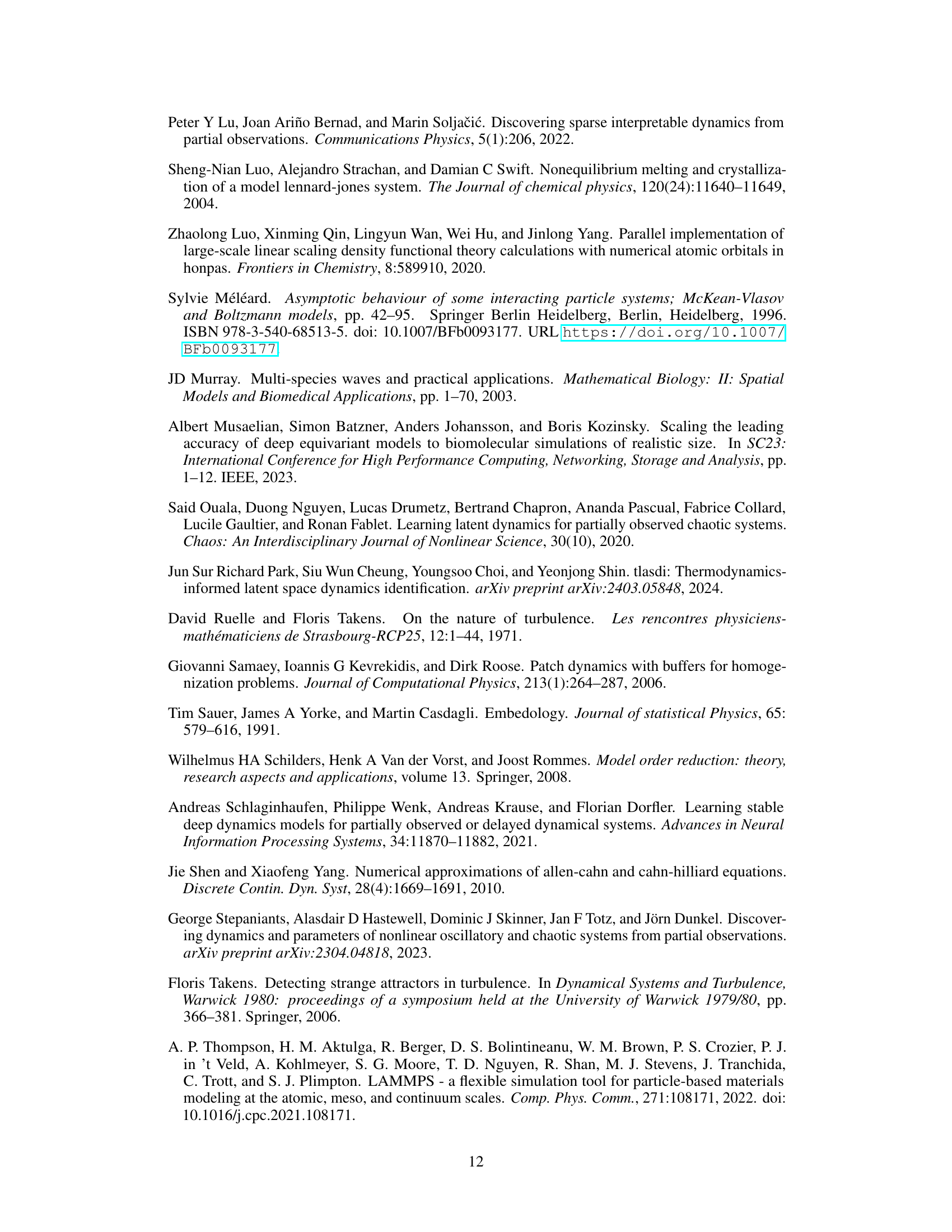

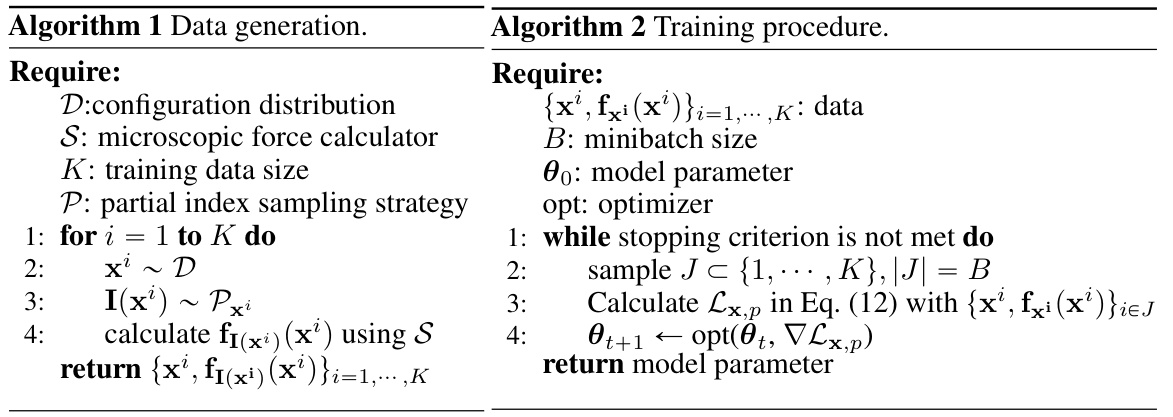

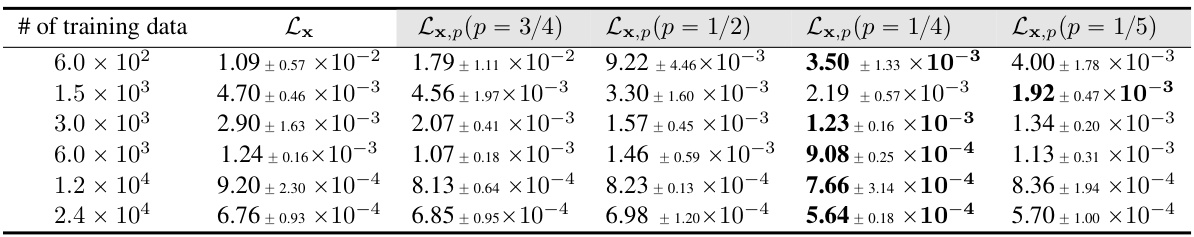

This table presents the results of the Predator-Prey system experiments. Models were trained using five different training metrics: Lx and Lx,p (with p values of 3/4, 1/2, 1/4, and 1/5). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the test error for each model, calculated across three separate experimental runs. The number of training data points used for each model and training metric is also provided.

In-depth insights#

Partial Force Learning#

Partial force learning presents a novel approach to modeling macroscopic dynamics by leveraging only partial microscopic force computations. This strategy is particularly beneficial for large-scale systems where computing all microscopic forces becomes computationally prohibitive. The core idea is to exploit sparsity assumptions within the system, suggesting that each microscopic coordinate’s force depends significantly on only a small subset of other coordinates. By mapping the learning process to the macroscopic level and employing stochastic estimation techniques using partial forces, the method achieves a significant reduction in computational costs while maintaining accuracy in predicting macroscopic behaviors. The theoretical justification for this approach, based on stochastic estimation, is a significant contribution. Robustness and efficiency are empirically validated across diverse microscopic systems, showcasing the wide applicability and potential of partial force learning for simulations and modeling.

Sparsity Assumption#

The Sparsity Assumption, crucial to the proposed method, posits that each microscopic coordinate’s force depends only on a limited subset of other coordinates. This assumption is key to achieving computational efficiency, as it avoids the need to compute forces for all microscopic coordinates, a task that is computationally prohibitive for large systems. The assumption’s validity hinges on the underlying physics of the system. Suitable conditions are needed to ensure its accuracy; otherwise, using partial forces may lead to inaccuracies in the learned dynamics. The theoretical justification provided for this assumption is crucial for understanding the robustness and reliability of the model. In essence, the Sparsity Assumption is a trade-off between computational cost and accuracy; it allows the model to learn effectively from limited information, providing a balance between efficiency and result quality.

Autoencoder Closure#

Autoencoder closure is a technique employed to learn the dynamics of macroscopic observables from a complex system using only partial microscopic information. It leverages the power of autoencoders to discover lower-dimensional latent space representations of the system’s state. By training the autoencoder on partial microscopic force computations, the method effectively reduces the computational burden of simulating the full system. Sparsity assumptions about the underlying microscopic forces are crucial for the efficiency gains. The core idea is that if the macroscopic dynamics can be represented as a closed system in the latent space, then accurate macroscopic predictions can be made even if we only have incomplete microscopic data. This approach allows us to avoid expensive computations of forces across the entire microscopic system, making it a highly efficient technique for large-scale systems where full microscopic modeling is intractable. Theoretical guarantees are provided to support the method’s validity under specific conditions, ensuring robustness and accuracy.

Macroscopic Dynamics#

The concept of macroscopic dynamics, focusing on the collective behavior of systems, is central to this research. The paper addresses the challenge of computationally expensive simulations needed to accurately predict macroscopic dynamics from microscopic interactions. A key insight is the sparsity assumption, suggesting that individual microscopic forces depend only on a small subset of other coordinates. This allows for significant computational savings by focusing on partial force computations. The core of the methodology is a novel method to learn macroscopic dynamics directly, mapping the learning procedure back to the microscopic level for efficient, partial force calculations. Theoretical justification is provided, showing that this partial force approach provides a stochastic estimation of the full system. Validation is demonstrated through multiple experiments on diverse microscopic models including those based on differential equations and molecular dynamics, showcasing robustness and efficiency. The approach is framed within a closure modeling context, but differentiates itself from existing reduced order models by directly addressing the macroscopic observables without needing full microscopic reconstruction.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on learning macroscopic dynamics from partial microscopic observations could explore several avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the method for even larger systems is crucial. This might involve investigating more sophisticated sparsity patterns or incorporating advanced machine learning techniques for more effective data representation and model training. Another key area would be to relax the sparsity assumption, developing techniques robust to systems where forces are highly interdependent. Exploring alternative latent model structures, beyond the ones used (MLPs, OnsagerNet, GFINNs), could also enhance performance and interpretability. Finally, extending the methodology to handle stochastic microscopic systems and more complex macroscopic observables would broaden its applicability significantly. This may necessitate integrating advanced statistical methods and incorporating domain-specific knowledge to handle the complexities introduced by stochasticity and high dimensionality.

More visual insights#

More on figures

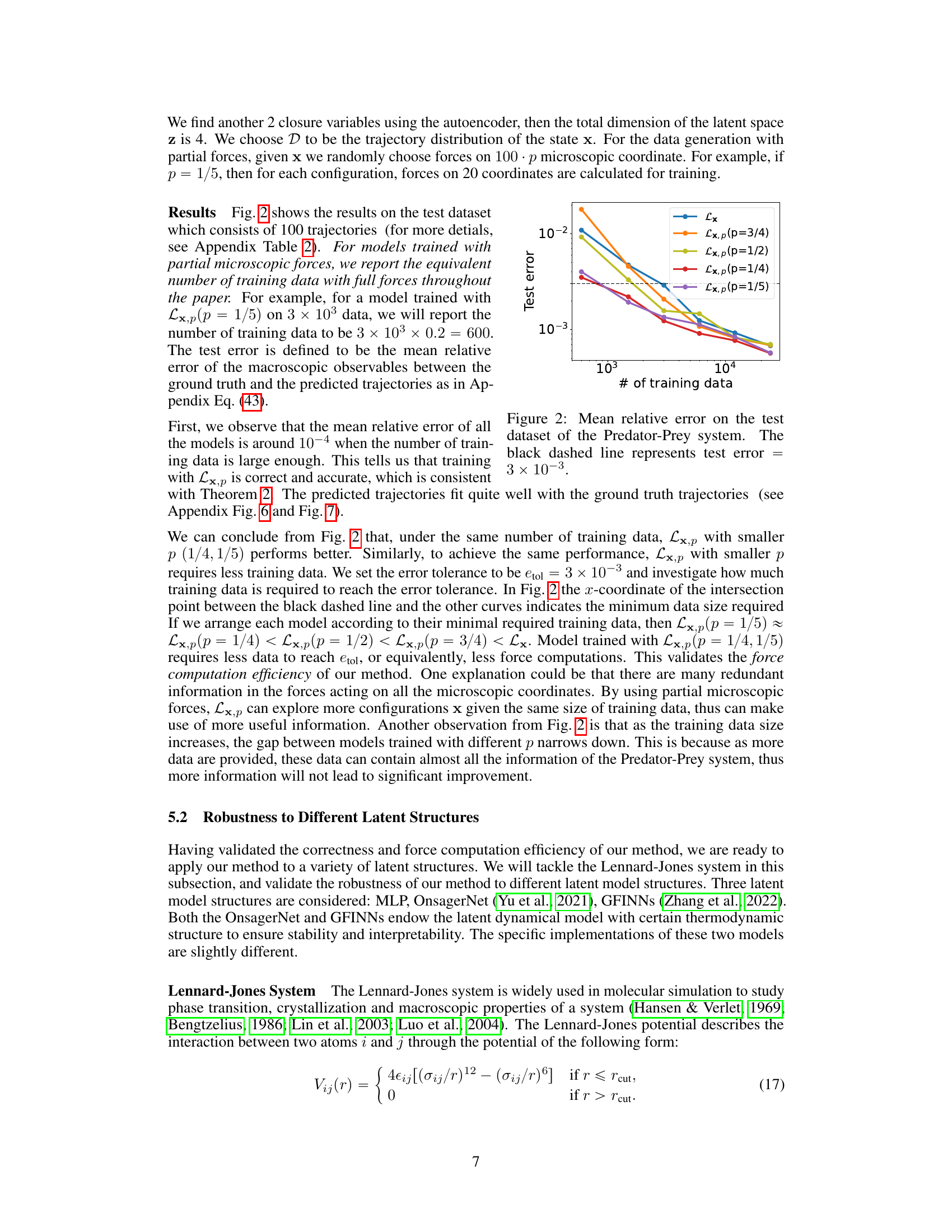

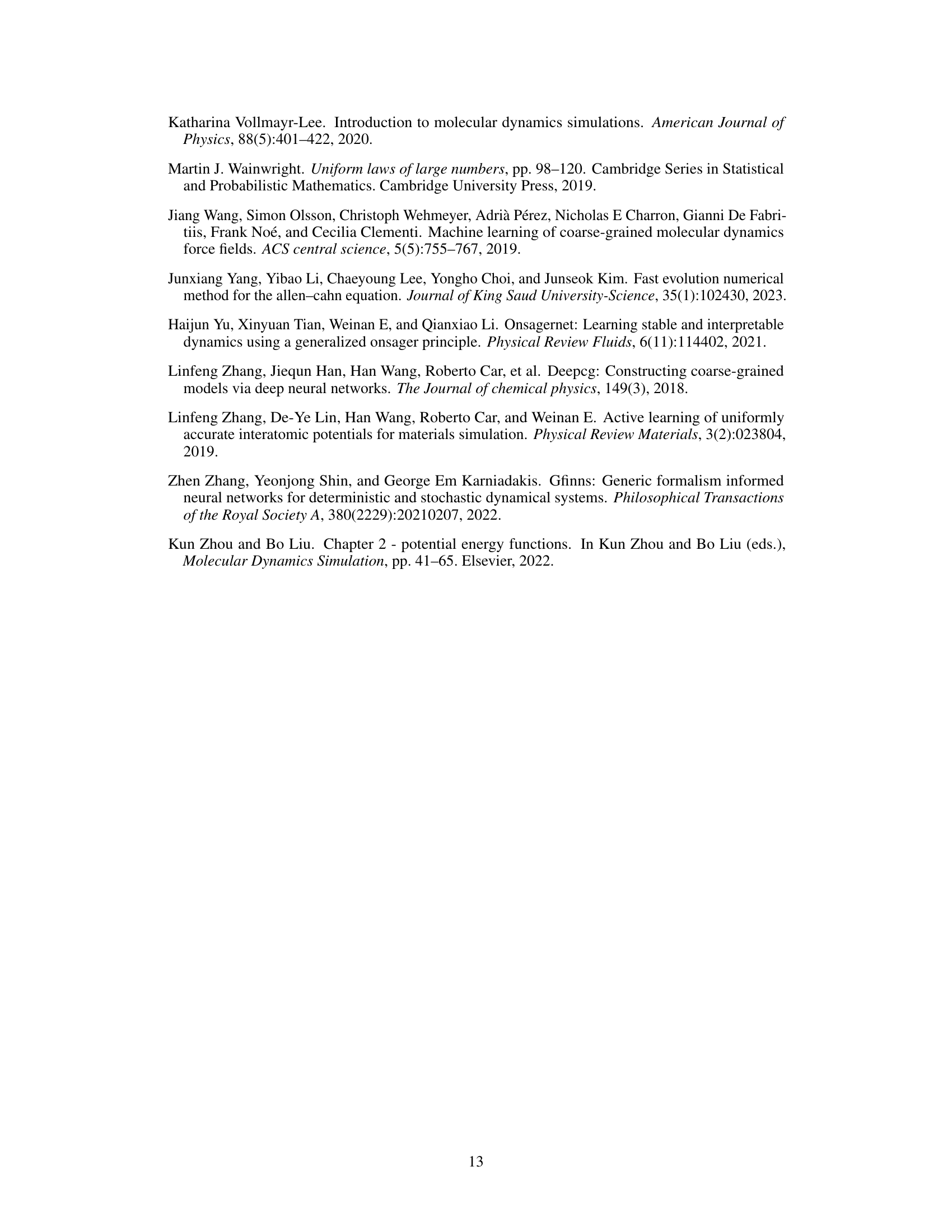

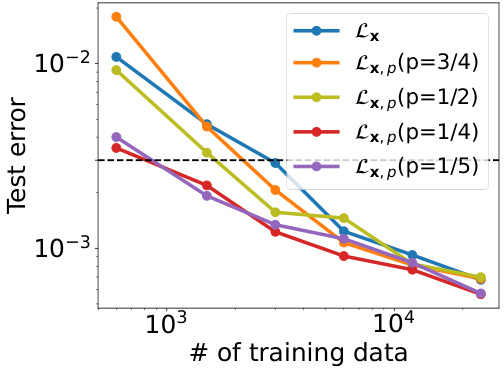

This figure shows the mean relative error on a test dataset for the Predator-Prey system using different training methods. The x-axis represents the number of training data points, and the y-axis represents the mean relative error. Multiple lines represent different methods for learning macroscopic dynamics, with different levels of partial force computation (p). The black dashed line indicates a test error threshold of 3 x 10^-3. The graph demonstrates that with sufficient data, all methods achieve a similar low error, but methods using partial force computations (especially with smaller values of p) achieve lower error with less data.

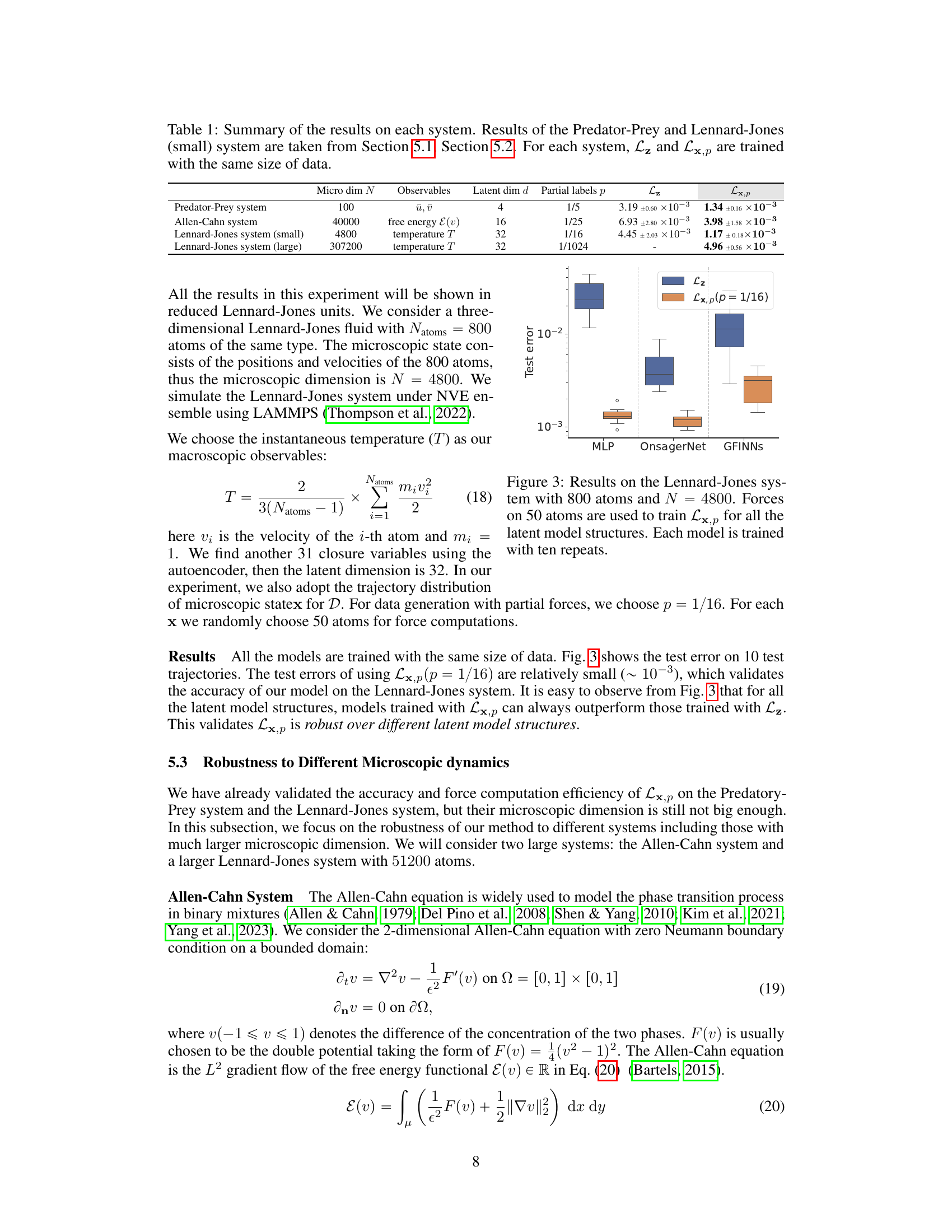

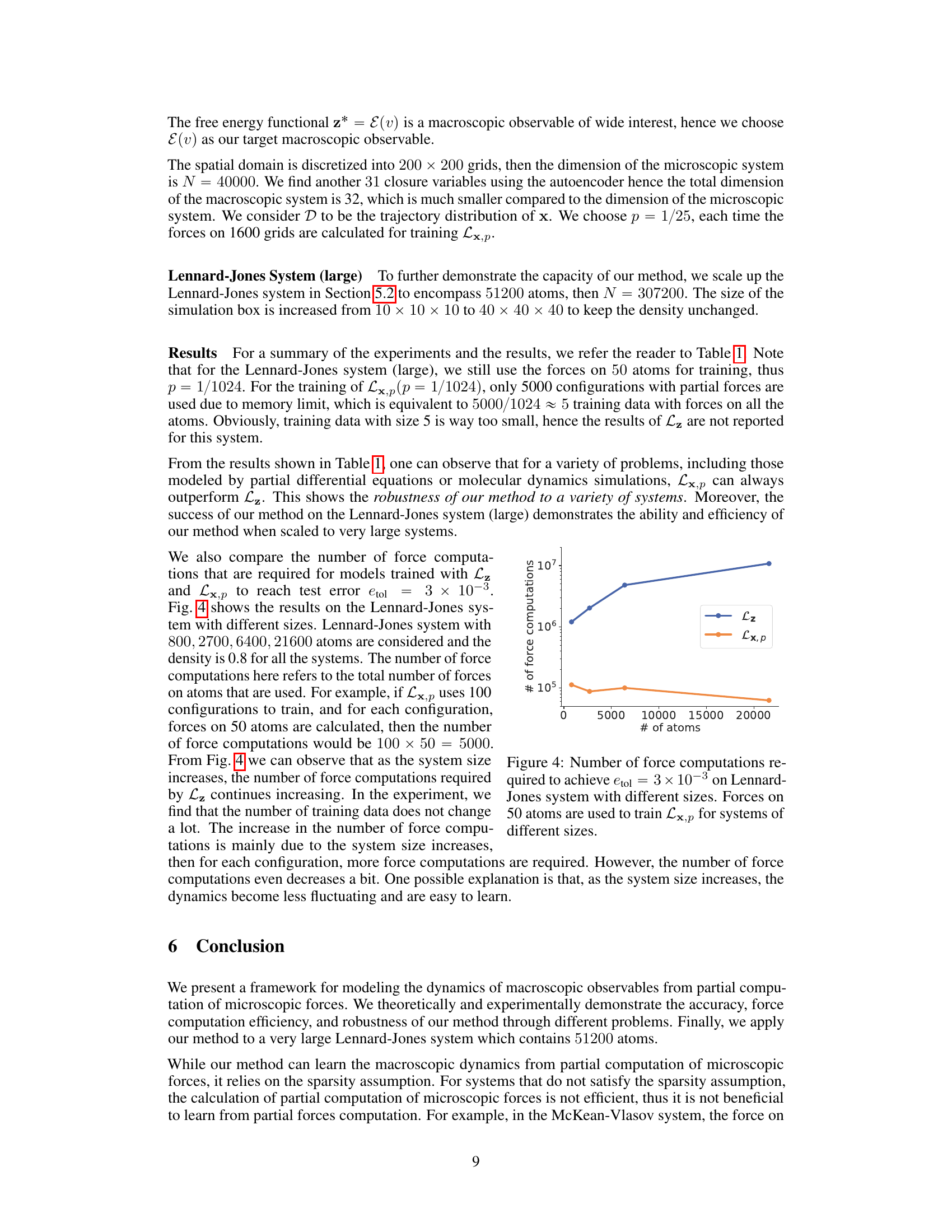

This figure shows the test error results on the Lennard-Jones system with 800 atoms (N=4800). The models used are trained with both full forces (Lz) and partial forces (Lx,p with p=1/16), using three different latent model structures: MLP, OnsagerNet, and GFINNs. The figure highlights that the models trained with partial forces (Lx,p) consistently show lower test errors compared to those trained with full forces (Lz), demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method even with reduced computational cost.

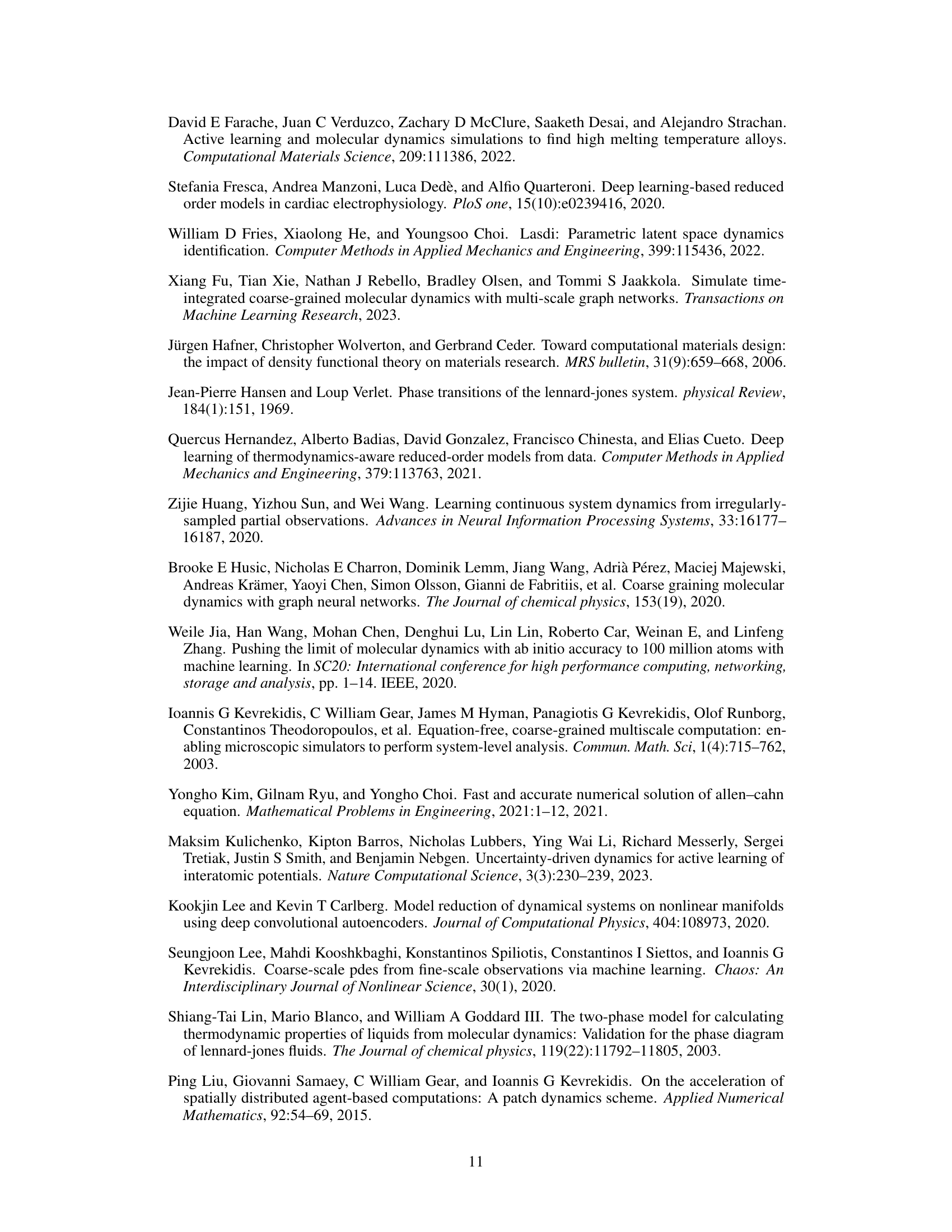

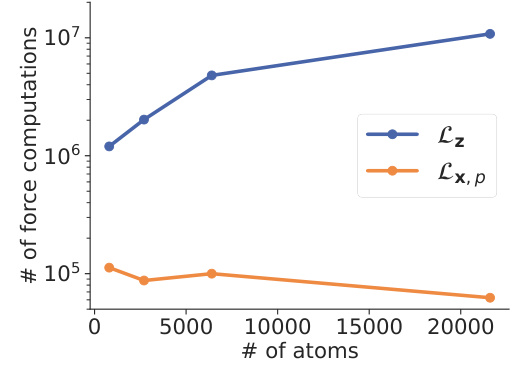

This figure compares the number of force computations needed to reach a specific error tolerance (etol = 3 × 10^-3) for two different methods (Lz and Lx,p) across Lennard-Jones systems with varying numbers of atoms. Lz represents the method using all microscopic forces, while Lx,p is the partial force method. The results demonstrate that the Lx,p method requires significantly fewer force computations, especially as the system size increases. The x-axis represents the number of atoms, and the y-axis denotes the number of force computations.

This figure illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed method. The left panel shows the data generation process: forces are computed on a subset of microscopic coordinates for each system configuration. The right panel details the macroscopic dynamics identification: the macroscopic dynamics are first mapped to the microscopic space, and then compared to the partially computed forces to update the model parameters. This comparison minimizes the loss function, leading to accurate learning of macroscopic dynamics from incomplete microscopic data.

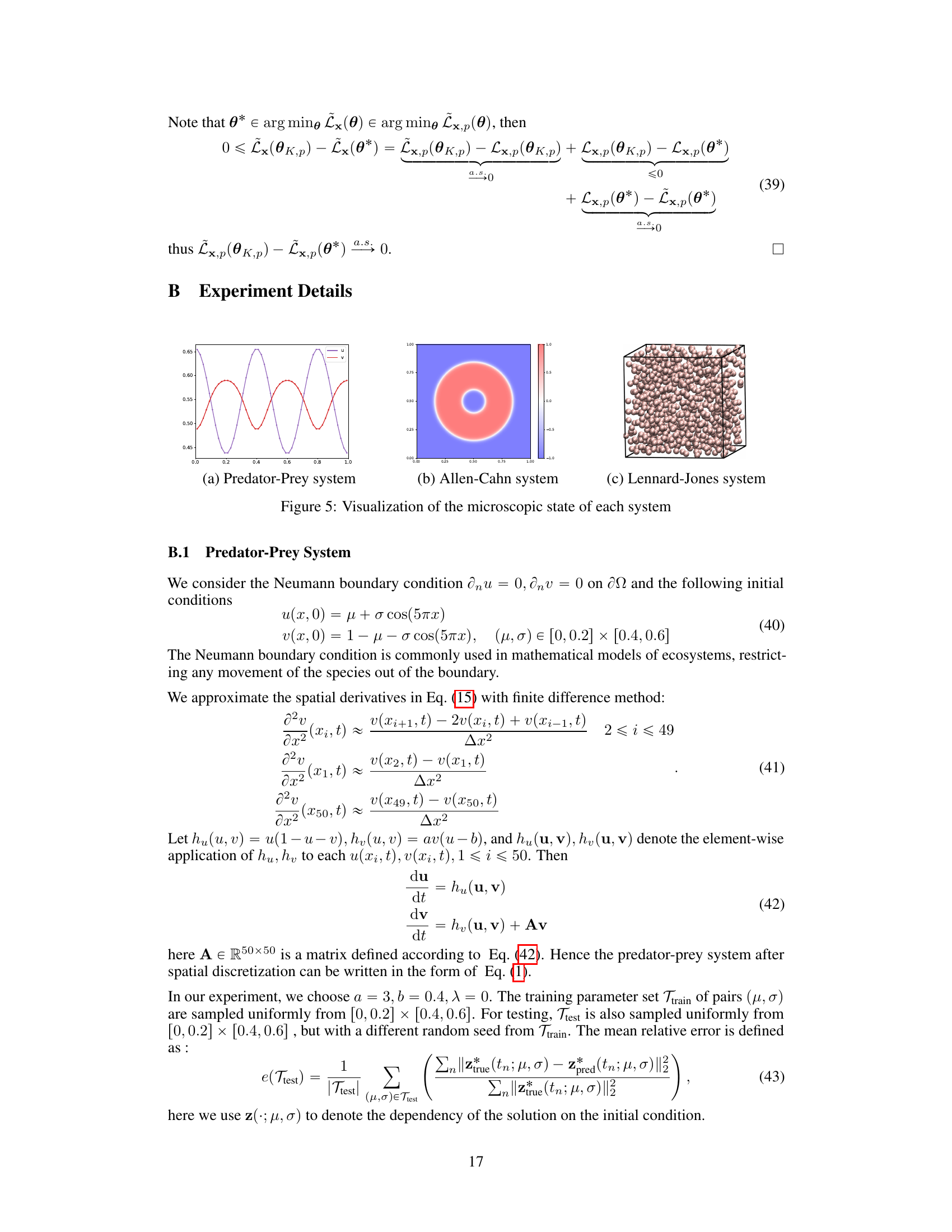

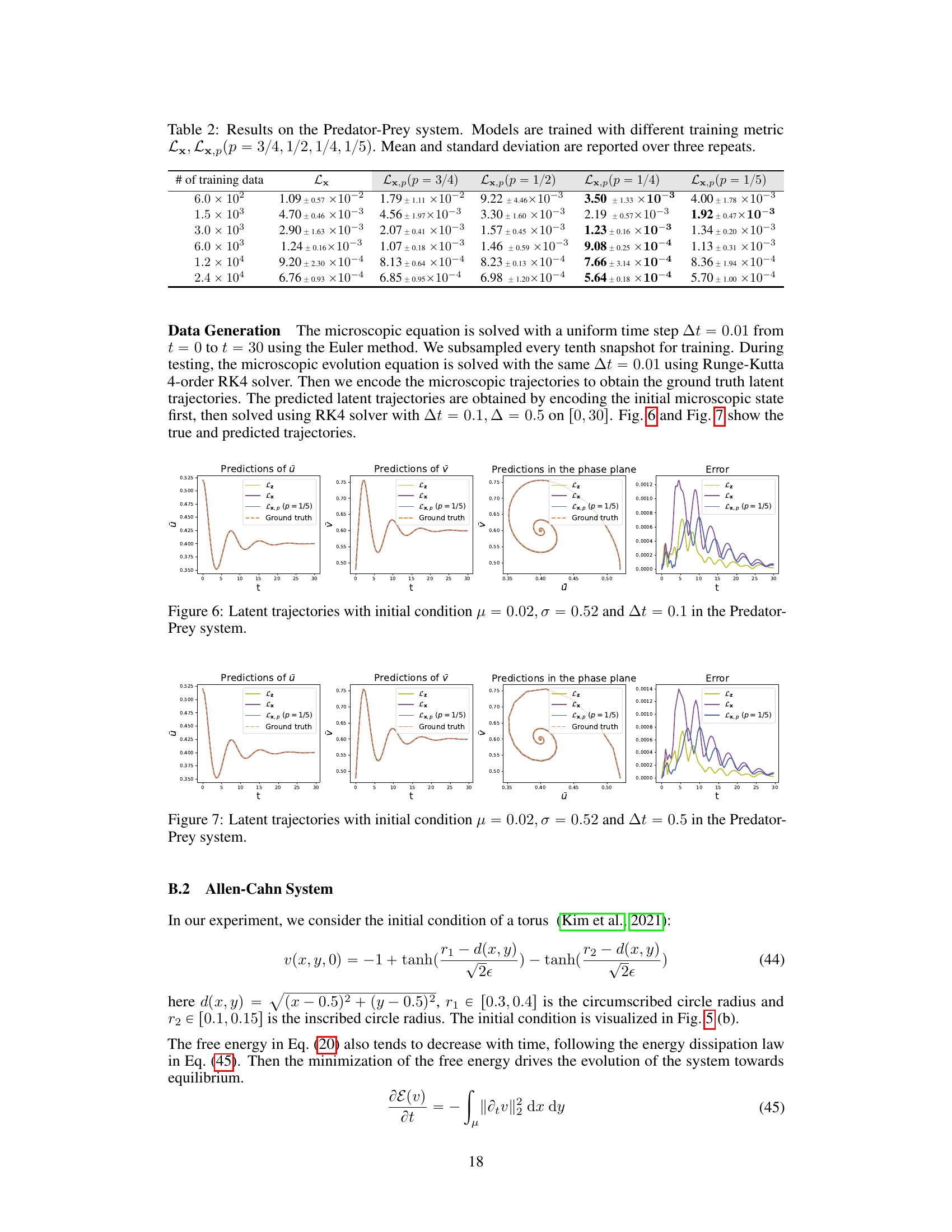

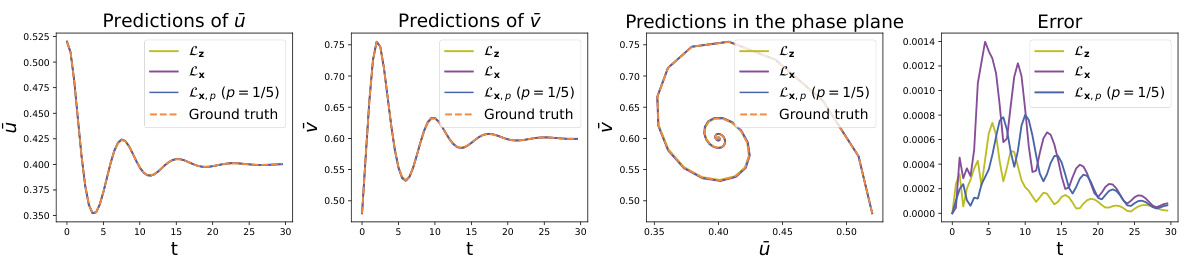

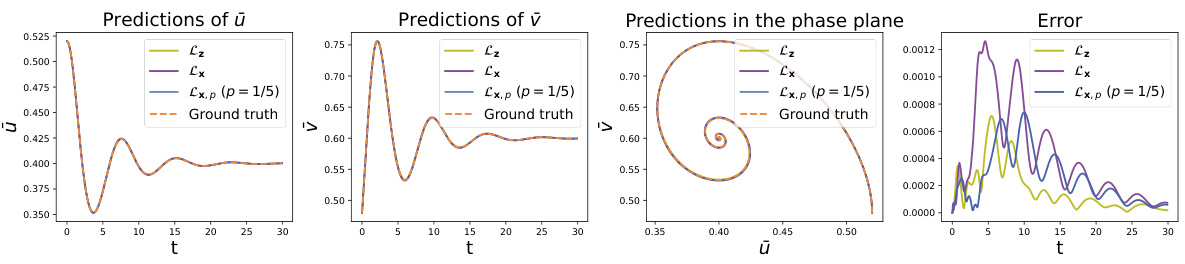

This figure shows the comparison of latent trajectories obtained from different methods in the Predator-Prey system. The initial condition is set as μ = 0.02 and σ = 0.52, and the time step is 0.5. The ground truth trajectories are generated by solving the microscopic equation and then encoding the results. The predictions from three methods are compared against the ground truth: Lz, which uses forces on all the microscopic coordinates; Lx, which uses forces on a subset of the microscopic coordinates; and Lx,p (p=1/5), which utilizes partial force computations. The figure includes plots showing the prediction of the prey and predator populations (ū and υ respectively), and a phase portrait illustrating the evolution of these populations. A final plot shows the error of the predictions from each method against the ground truth.

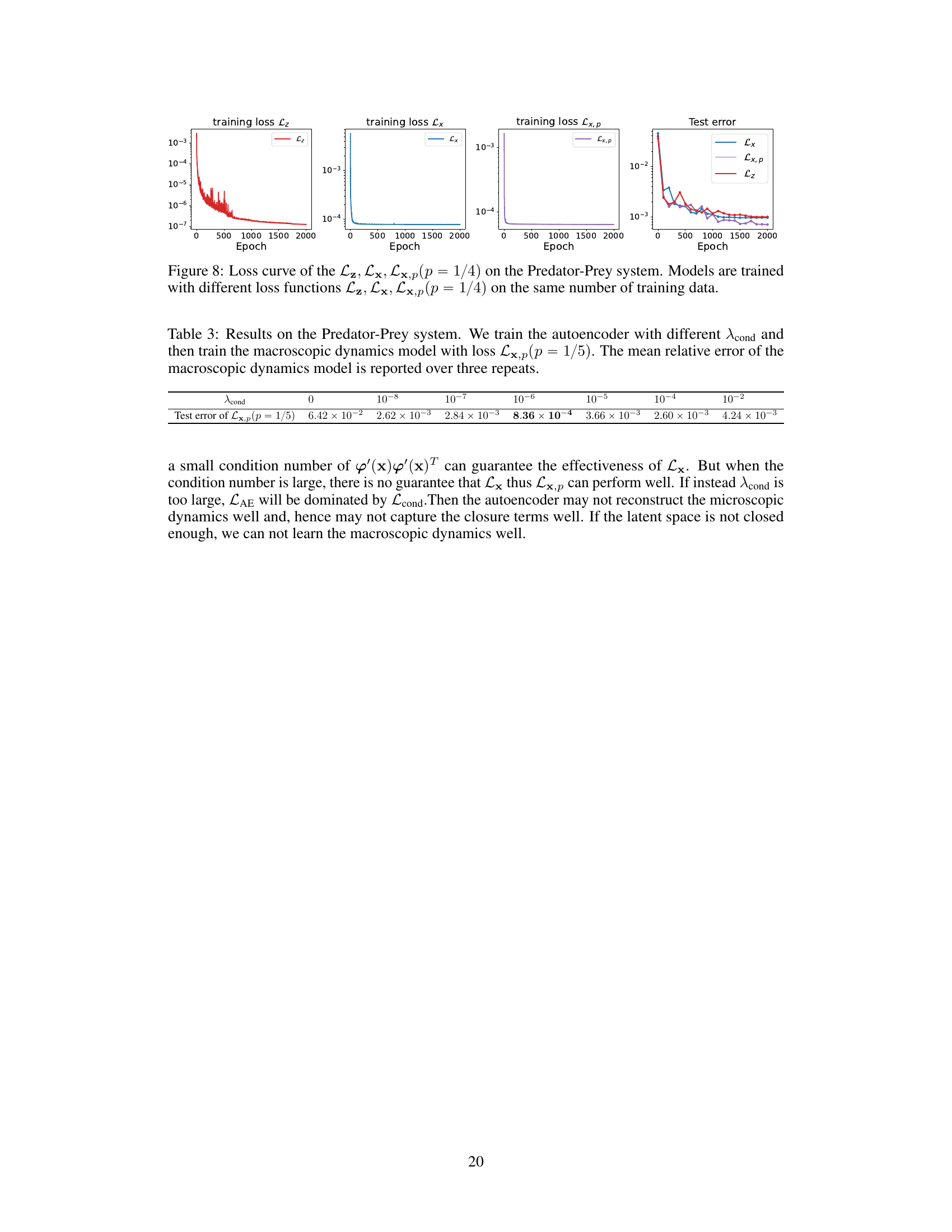

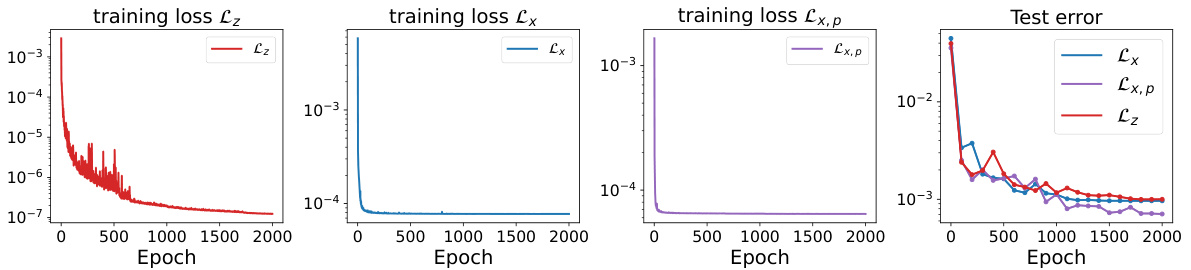

This figure compares the training and testing loss curves for three different loss functions: Lz (using all microscopic forces), Lx (using a subset of forces), and Lx,p (using a subset of forces with a specific sampling strategy). The plot shows how these loss functions converge during training, and the relative test error at the end of training. The results illustrate that Lx and Lx,p are effective and efficient alternatives to Lz, especially Lx,p, which uses a smaller subset of forces.

More on tables

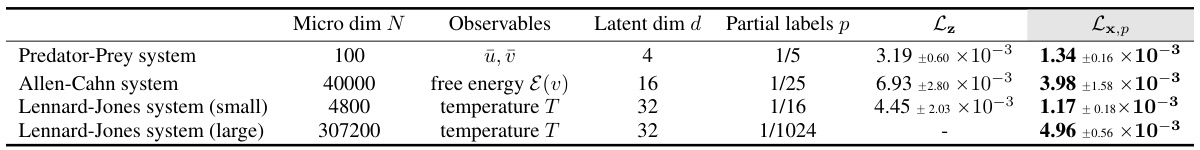

This table summarizes the performance of the proposed method (Lx,p) and the baseline method (Lz) on four different systems: Predator-Prey, Allen-Cahn, and Lennard-Jones systems (small and large). For each system, the table shows the microscopic dimension (N), macroscopic observables, latent dimension (d) of the autoencoder, fraction of microscopic coordinates used for force computation (p), and the mean relative test error for both methods (Lz and Lx,p). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of Lx,p in reducing force computation costs while maintaining accuracy, particularly noticeable in large-scale systems.

This table presents the results of experiments on the Predator-Prey system using different training metrics. It shows the mean relative error and standard deviation for each metric across three repeated experiments. The different metrics used are Lx (full microscopic forces) and Lx,p with varying values of p (the fraction of microscopic coordinates for which forces are computed). The number of training data points varies across rows.

The table presents the results of the Predator-Prey system experiments using different training metrics (Lx, Lx,p with varying p values). It shows the mean relative error (and standard deviation) on the test dataset for models trained with different amounts of training data. The results demonstrate the performance of the proposed method (Lx,p) and its comparison against the baseline method (Lx) with full forces. The p value represents the proportion of microscopic coordinates for which forces are computed.

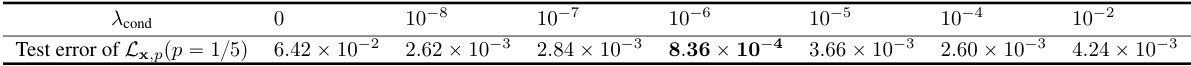

This table shows the test error of the macroscopic dynamics model trained with different values of the hyperparameter λcond. The test error is the mean relative error of the macroscopic observables between the ground truth and the predicted trajectories. The results show that the test error decreases as λcond increases from 0 to 10⁻⁶, and then increases as λcond increases further from 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻². The minimum test error is achieved when λcond = 10⁻⁶.

Full paper#