TL;DR#

Molecule inverse folding, crucial for drug and material discovery, has been tackled separately for small and large molecules, leading to redundant efforts. Existing models often struggle with the “unit discrepancy” (using different basic units for different molecules), “geometric featurization” (varying strategies for extracting geometric properties), and “system size” (difficulty scaling to large molecules). These inconsistencies hinder the development of a generalizable solution.

UniIF proposes a unified solution by: 1) representing all molecules as block graphs, 2) introducing a geometric featurizer for consistent feature extraction, 3) using a geometric block attention network with virtual blocks to capture 3D interactions and long-range dependencies efficiently. UniIF demonstrates state-of-the-art results across protein, RNA, and material design tasks, showcasing its versatility and effectiveness as a unified solution for molecule inverse folding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly important because it presents UniIF, a unified model for molecule inverse folding, a long-standing challenge with implications for drug and material discovery. Its superior generalizability and state-of-the-art performance across diverse tasks make it a significant contribution, opening new avenues for research in AI-driven molecular design. The unified approach addresses the limitations of existing methods that focus on specific molecule types, offering a more versatile and efficient solution for future research.

Visual Insights#

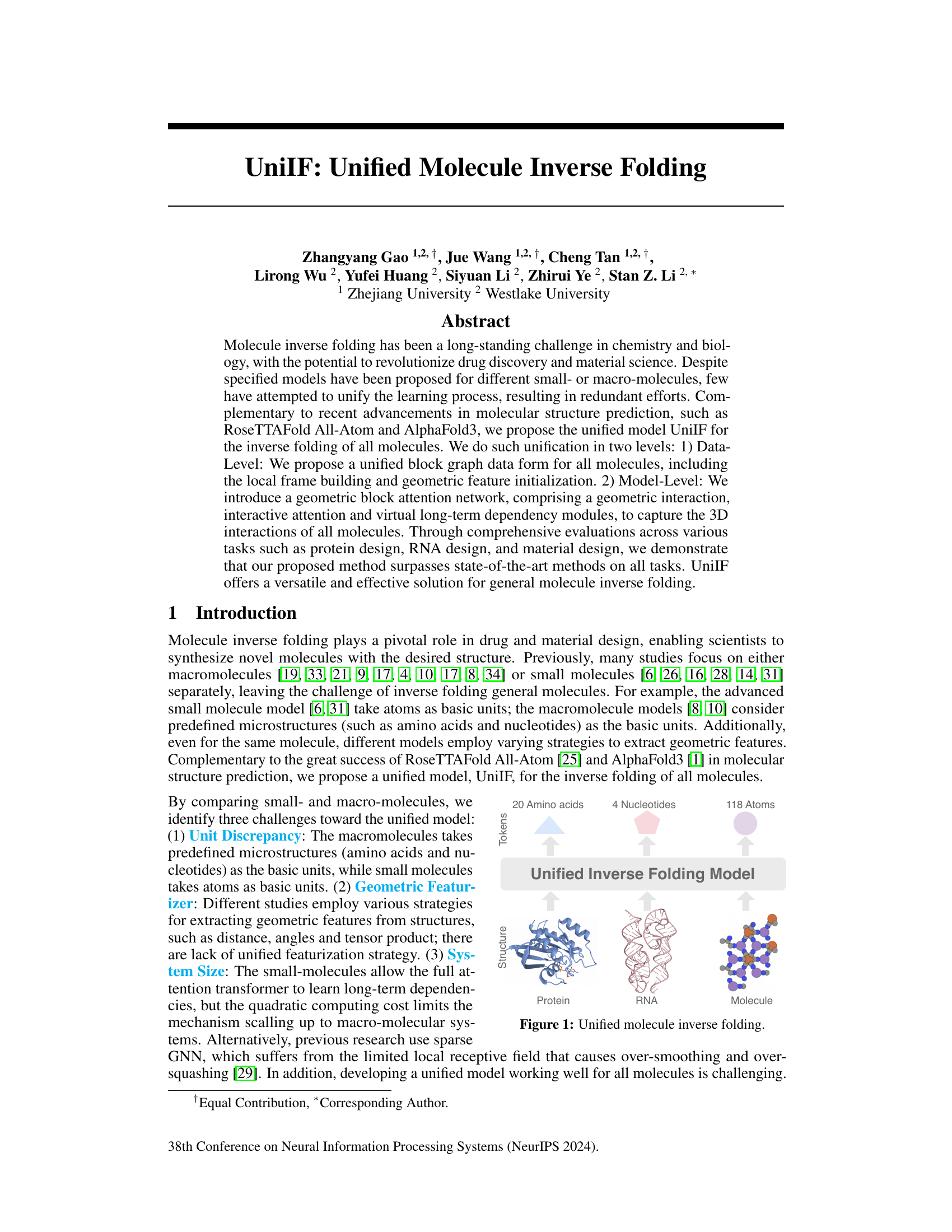

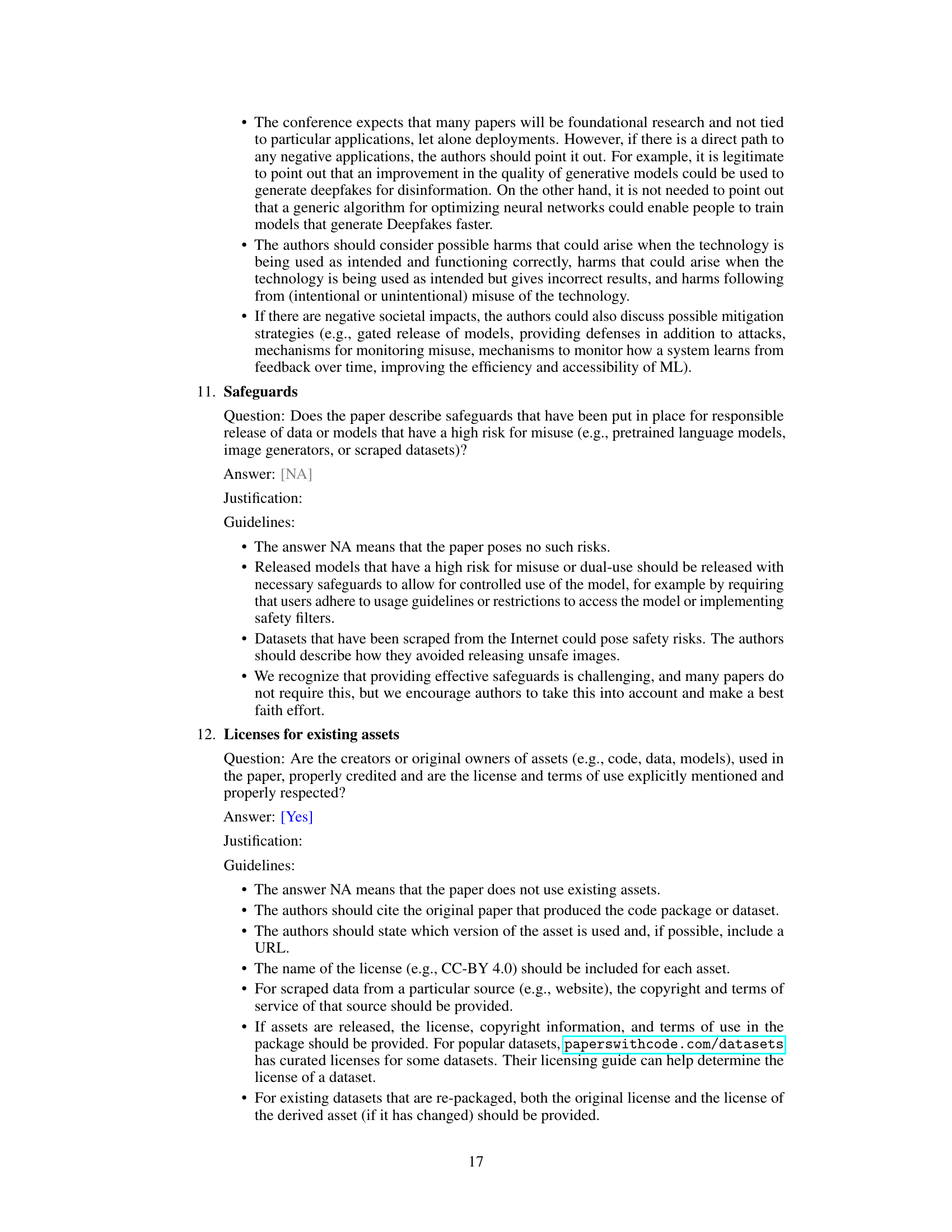

🔼 This figure illustrates the unified molecule inverse folding model, UniIF, which handles proteins, RNA, and small molecules. It highlights the different basic units used for each molecule type (amino acids for proteins, nucleotides for RNA, and atoms for small molecules) and shows how UniIF unifies their representation to perform inverse folding.

read the caption

Figure 1: Unified molecule inverse folding.

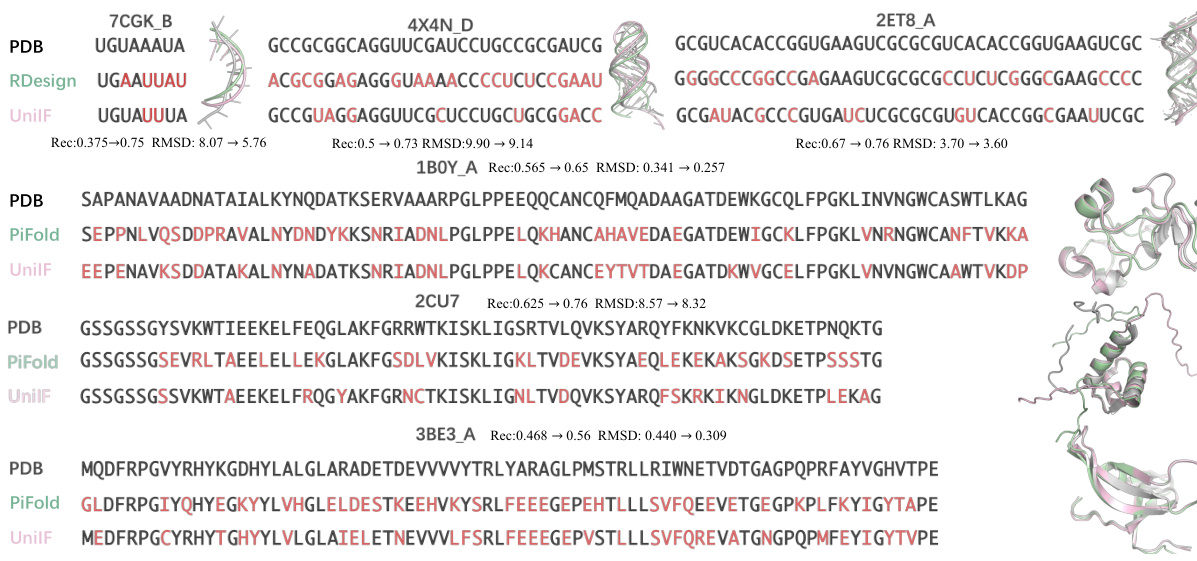

🔼 This table presents the results of protein design experiments comparing the performance of UniIF against various baselines (with and without ESM2) across different datasets (CATH4.3, CASP, NovelPro). It showcases UniIF’s superior performance, particularly in time-split evaluations where it surpasses even ESM2-based methods, highlighting its generalizability. Ablation studies analyze the effects of removing key components of the UniIF model (geometric dot product, gated edge attention, and virtual frames).

read the caption

Table 1: Protein Design results. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underlined. 'VFN' means that we replace the geometric interaction operation with VFN's operation [27]. '-GDP' means that we remove the geometric dot product features. '-EAttn' means that we replace the gated edge attention with PiGNN's attention module [10]. '-VFrame' means that we remove the global virtual frames.

In-depth insights#

Unified Inverse Folding#

The concept of “Unified Inverse Folding” presents a significant advancement in molecular design. Instead of employing separate models for different molecule types (proteins, RNA, small molecules), a unified approach offers significant advantages in efficiency and generalizability. A unified model would streamline the learning process, eliminating redundant efforts in data representation and model architecture. By leveraging shared underlying principles of molecular structure, it could potentially achieve superior performance across various tasks compared to specialized models. Challenges remain in developing a truly unified approach, as different molecule types exhibit unique structural features and properties requiring tailored strategies. The key is to effectively capture the fundamental geometric interactions governing molecular folding across all molecule types. Successful implementation would represent a major leap in the field, enabling the design of novel molecules with unprecedented speed and accuracy for various applications in drug discovery, materials science, and beyond. A crucial aspect of success would involve creating a robust and efficient data representation capable of handling the diversity of molecular structures.

Geometric Featurization#

Geometric featurization is a crucial step in geometric deep learning, particularly when applied to molecules. Effective featurization must capture the essential geometric information, such as distances, angles, and dihedral angles, in a manner that is both informative and computationally efficient. The choice of geometric features directly impacts model performance and generalizability. Simple distance-based features might be insufficient for complex molecular structures, while more sophisticated representations, such as those based on tensors or interaction fingerprints, are computationally expensive. A key challenge is to find a balance between representational power and computational cost. Furthermore, featurization should be adaptable to different molecule types, whether proteins, RNA, or small molecules, while maintaining consistency in the data representation to facilitate unified modeling. The use of equivariant representations can help preserve geometric properties under transformations, increasing the robustness of the model. Finally, successful featurization often requires careful consideration of the downstream task and careful feature engineering, potentially combining different feature types to capture the full complexity of the underlying molecular data.

Block Graph Attention#

The concept of “Block Graph Attention” suggests a novel approach to graph neural networks (GNNs) applied to molecular structures. Instead of treating individual atoms as nodes, it groups atoms into meaningful blocks (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, or groups of atoms), significantly reducing computational complexity while preserving crucial structural information. The attention mechanism is then applied at the block level, focusing on interactions between these blocks rather than individual atoms. This allows the model to capture longer-range dependencies and higher-level structural features more effectively. A key advantage is the potential for better scalability to larger molecules where atom-level GNNs become computationally prohibitive. The block representation may involve both equivariant (geometrically oriented) and invariant (atom type) features, capturing the full essence of each structural unit. By combining geometric features (distances, angles, orientations) with the invariant features in the attention mechanism, this method could potentially lead to more accurate and robust predictions in tasks like inverse molecular folding, protein/RNA design, and material discovery. Further research should investigate the optimal block definition strategies and the design of the attention mechanism itself, exploring different attention variants (e.g., self-attention, global attention) and their impact on model performance and generalizability.

Experimental Results#

The section detailing experimental results should present a clear and concise overview of the findings, emphasizing the key contributions of the research. Quantitative metrics should be prominently featured, using tables and figures to efficiently communicate complex data. A critical analysis of the results is necessary, discussing both the strengths and weaknesses of the findings in relation to existing literature. This may involve comparisons to state-of-the-art baselines and in-depth discussions of any unexpected outcomes. Statistical significance must be rigorously established for all claims made, using appropriate statistical tests and clearly reporting p-values or confidence intervals. The presentation of results should follow a logical flow, gradually unveiling the main findings while avoiding ambiguity. Visualizations should be meticulously crafted to maximize clarity and facilitate understanding of even the most complex experimental results. It should also address any limitations of the experimental design and discuss potential sources of error. Overall, this section must provide compelling evidence to support the paper’s claims and offer insightful conclusions that advance the field.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this unified molecule inverse folding model (UniIF) could involve several key areas. Extending UniIF’s capabilities to handle even larger and more complex molecules, such as entire viral capsids or large macromolecular assemblies, is crucial. Improving efficiency by developing more sophisticated and computationally less expensive sparse graph neural networks and optimizing the training process are essential. Incorporating additional information, like dynamics or environmental factors, could significantly enhance the accuracy and predictive power of UniIF. Furthermore, exploring alternative model architectures, perhaps combining the strengths of transformers and graph neural networks in novel ways, warrants investigation. Finally, developing a robust benchmark dataset that encompasses a wide range of molecule types and sizes and that accounts for various relevant properties would greatly benefit the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

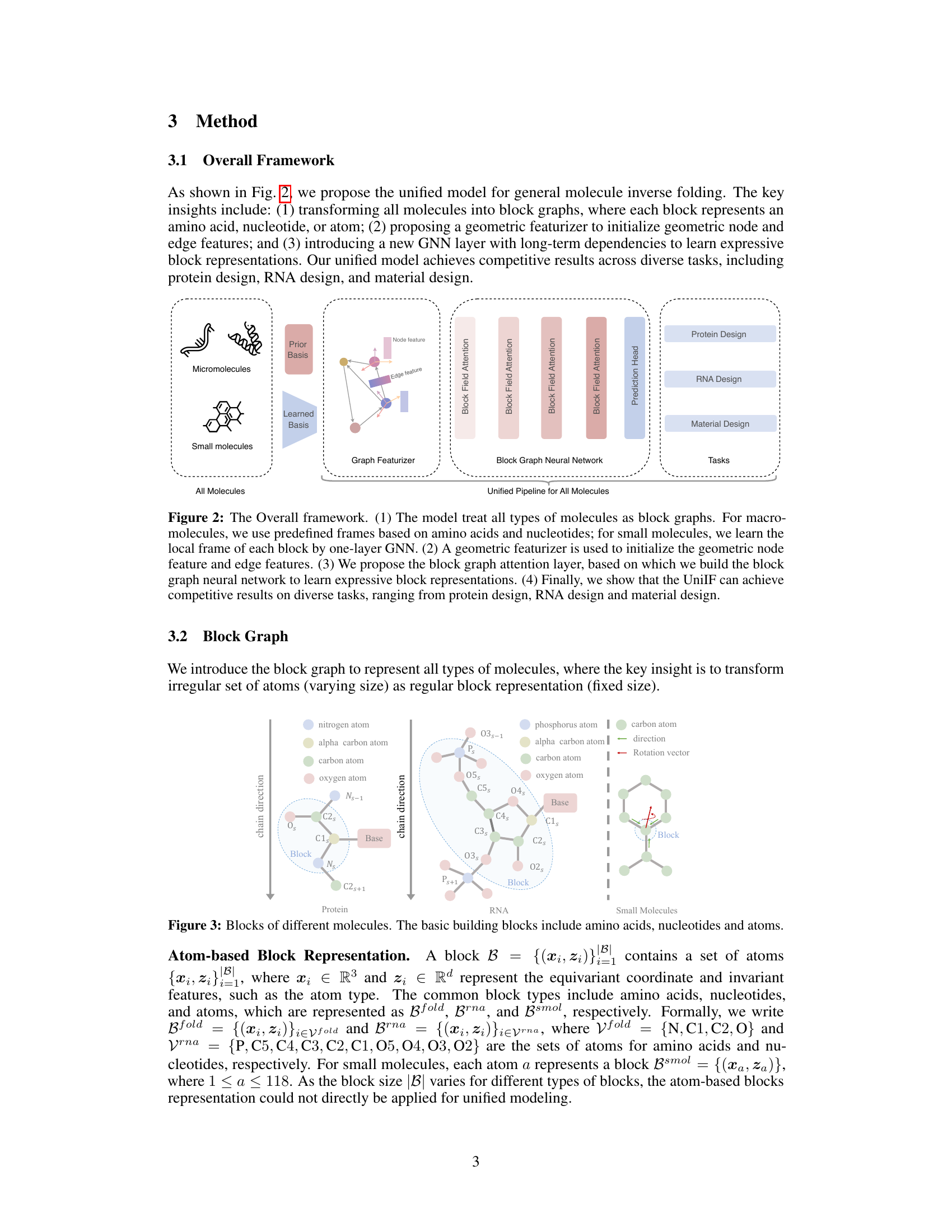

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall framework of the UniIF model. It shows how different types of molecules (micromolecules, small molecules, and all molecules) are processed using a unified pipeline. The pipeline consists of four main stages: 1. Block Graph Representation: Transforming molecules into block graphs. 2. Geometric Featurizer: Initializing geometric node and edge features. 3. Block Graph Neural Network: Learning expressive block representations using a block graph attention layer. 4. Prediction Head: Predicting the desired properties for various tasks (protein design, RNA design, material design).

read the caption

Figure 2: The Overall framework. (1) The model treat all types of molecules as block graphs. For macromolecules, we use predefined frames based on amino acids and nucleotides; for small molecules, we learn the local frame of each block by one-layer GNN. (2) A geometric featurizer is used to initialize the geometric node feature and edge features. (3) We propose the block graph attention layer, based on which we build the block graph neural network to learn expressive block representations. (4) Finally, we show that the UniIF can achieve competitive results on diverse tasks, ranging from protein design, RNA design and material design.

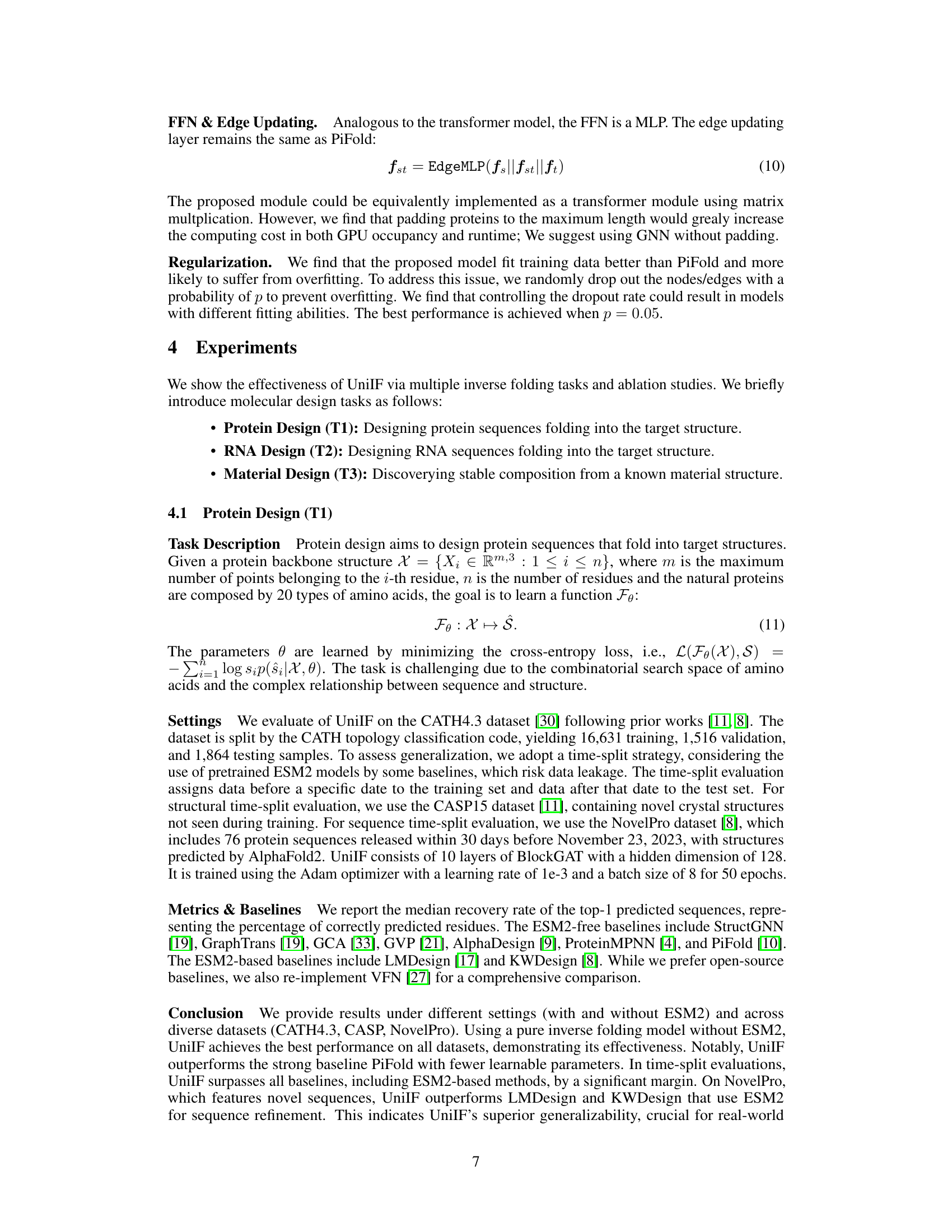

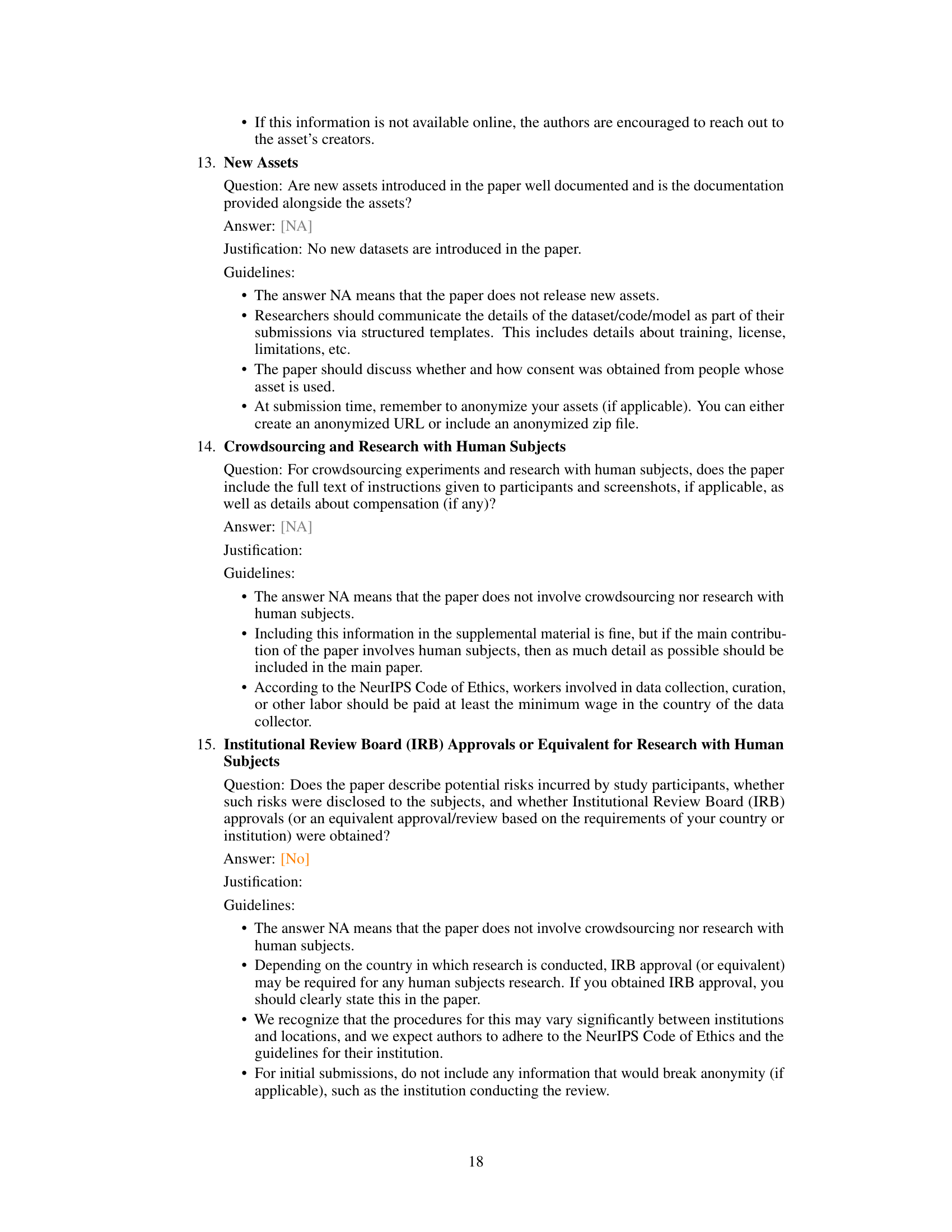

🔼 This figure illustrates how different types of molecules are represented as blocks in the UniIF model. The leftmost panel shows a protein block, composed of an amino acid and its constituent atoms (nitrogen, alpha-carbon, carbon, and oxygen). The middle panel displays an RNA block, similarly showing the nucleotides and atoms. The rightmost panel demonstrates a small molecule block, illustrating the direct representation using atoms. The consistent use of a ‘block’ as the base unit facilitates unification in the model’s architecture, accommodating the varying structural complexities of different molecule types.

read the caption

Figure 3: Blocks of different molecules. The basic building blocks include amino acids, nucleotides and atoms.

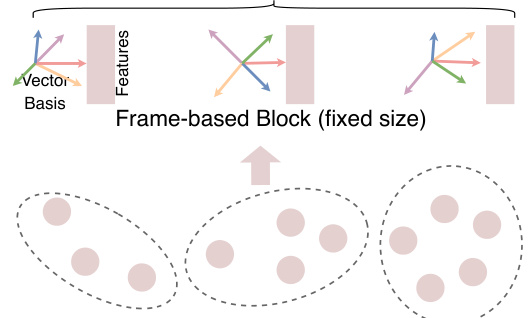

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the UniIF model, which unifies the representation of small and macro-molecules using a frame-based block. The atom-based block (varying size) is converted into a frame-based block (fixed size) for consistent processing. This block consists of an equivariant frame (axis matrix and translation vector) and invariant features. The frame-based blocks are then organized into a graph, facilitating the geometric interaction learning within the UniIF model.

read the caption

Figure 4: Unified molecule inverse folding.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Block Graph Attention Module, a key component of the UniIF model. It shows how the model handles long-range dependencies using virtual blocks, extracts geometric features through geometric interactions, and updates node features via a gated edge attention mechanism. Panel (a) depicts the virtual blocks introduced to capture long-range interactions. Panel (b) shows how the model processes both real and virtual blocks within a graph framework. Panel (c) and (d) detail the geometric interaction and gated edge attention modules, respectively, showing how the model integrates geometric information and updates features.

read the caption

Figure 5: Block Graph Attention Module. (a) Virtual Block for Long-term Dependencies. (b) Geometric Interaction Extractor for learning pairwise features. (c) Gated Edge Attention for updating node features.

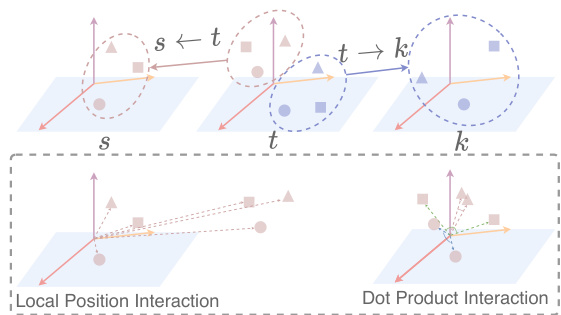

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of geometric interactions within the Block Graph Attention Module. The top panel shows three blocks (s, t, k) and their respective local coordinate systems, highlighting how interactions are modeled between neighboring blocks using relative frame transformations. The bottom panel details two key types of interactions: * Local Position Interaction: Demonstrates how the relative positions of virtual atoms are considered in capturing spatial relationships between blocks. * Dot Product Interaction: Shows how the dot product of intra-block virtual atoms is utilized to capture angular information, adding another layer of geometric context. In essence, the figure visually explains how the model uses virtual atoms and both relative positions and angular information to enrich the geometric representation of interactions between blocks within the graph.

read the caption

Figure 6: Geometric Interactions.

🔼 This figure shows three types of molecules (protein, RNA, and a small molecule) represented as unified block graphs. Each molecule type is shown as a different block representation in a unified inverse folding model, highlighting the model’s ability to handle various molecule types.

read the caption

Figure 1: Unified molecule inverse folding.

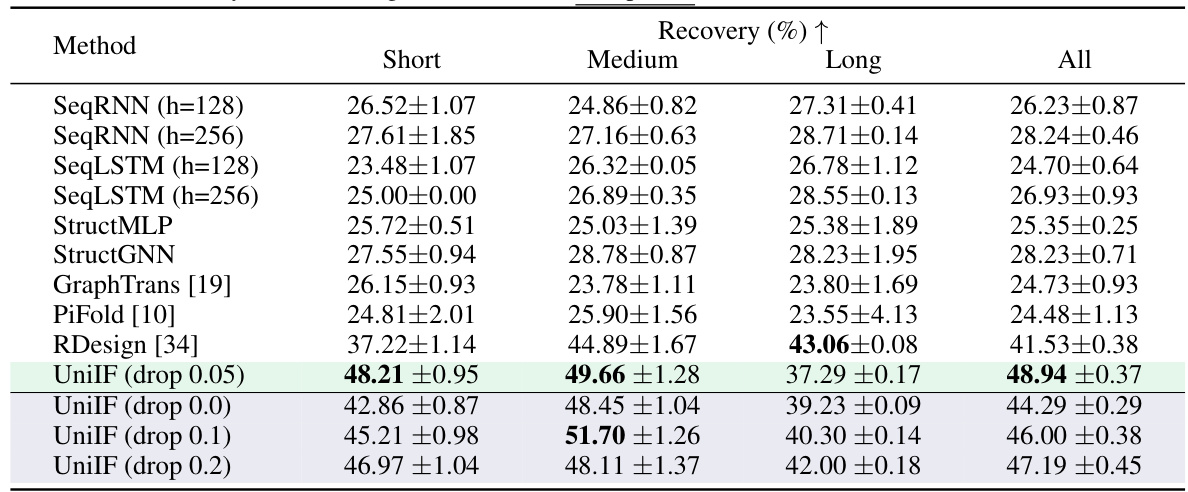

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of RNA inverse folding experiments using various methods, including SeqRNN, SeqLSTM, StructMLP, StructGNN, GraphTrans, PiFold, RDesign, and the proposed UniIF model. The recovery rate, which represents the percentage of correctly predicted residues in the RNA sequences, is reported for short, medium, long, and all lengths of RNA sequences. The results are shown as median and standard deviation over three independent runs. The table demonstrates the improved performance of the UniIF model compared to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 2: The recovery of RNA design. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underlined.

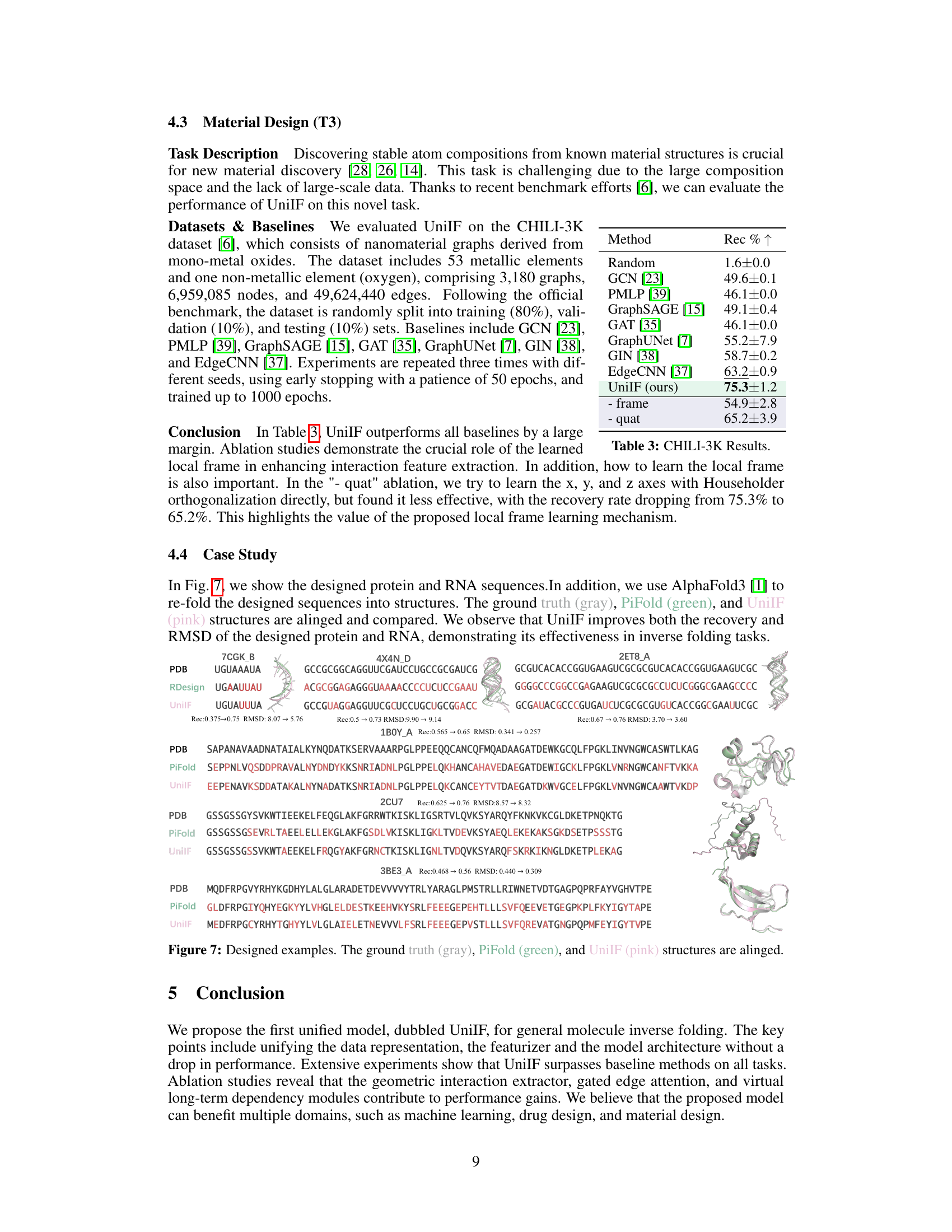

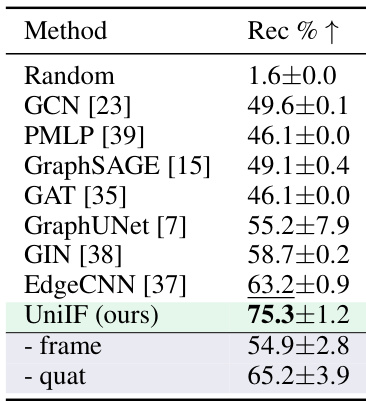

🔼 This table presents the results of the material design task (T3) on the CHILI-3K dataset. It compares the recovery rate (Rec % ↑) achieved by UniIF against several baseline methods including GCN, PMLP, GraphSAGE, GAT, GraphUNet, GIN, and EdgeCNN. The table also shows ablation studies for UniIF, specifically removing the learned frame and using quaternions instead of the learned frame for orientation representation, highlighting the importance of the proposed frame-based block representation and the learned frame for optimal performance.

read the caption

Table 3: CHILI-3K Results.

Full paper#