↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) typically rely on extensive instance training for adapting to new tasks, which limits their adaptability and efficiency. This paper addresses this challenge by simulating human learning through instructions, highlighting that humans learn efficiently by understanding and following guidelines, unlike the repetitive practice-based approach of LLMs. This is a significant limitation in real-world applications where labeled data is scarce.

The paper introduces Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI), a novel method that automatically constructs task-specific models from instructions without retraining. TAGI uses knowledge distillation to align generated task adapters with instance-trained models. A two-stage training process, hypernetwork pre-training and fine-tuning, enhances cross-task generalization. Experiments on benchmark datasets demonstrate TAGI’s ability to match or surpass meta-trained models while drastically reducing computational requirements. The key contribution lies in effectively leveraging instructions for LLM adaptation, mirroring human learning, and achieving better generalization with fewer resources.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to cross-task generalization in large language models (LLMs). By using instructions instead of extensive task data, it reduces computational costs and improves adaptability to real-world scenarios. This method is relevant to researchers working on efficient few-shot learning and LLM optimization and opens avenues for investigation in instruction-based learning and hypernetwork models.

Visual Insights#

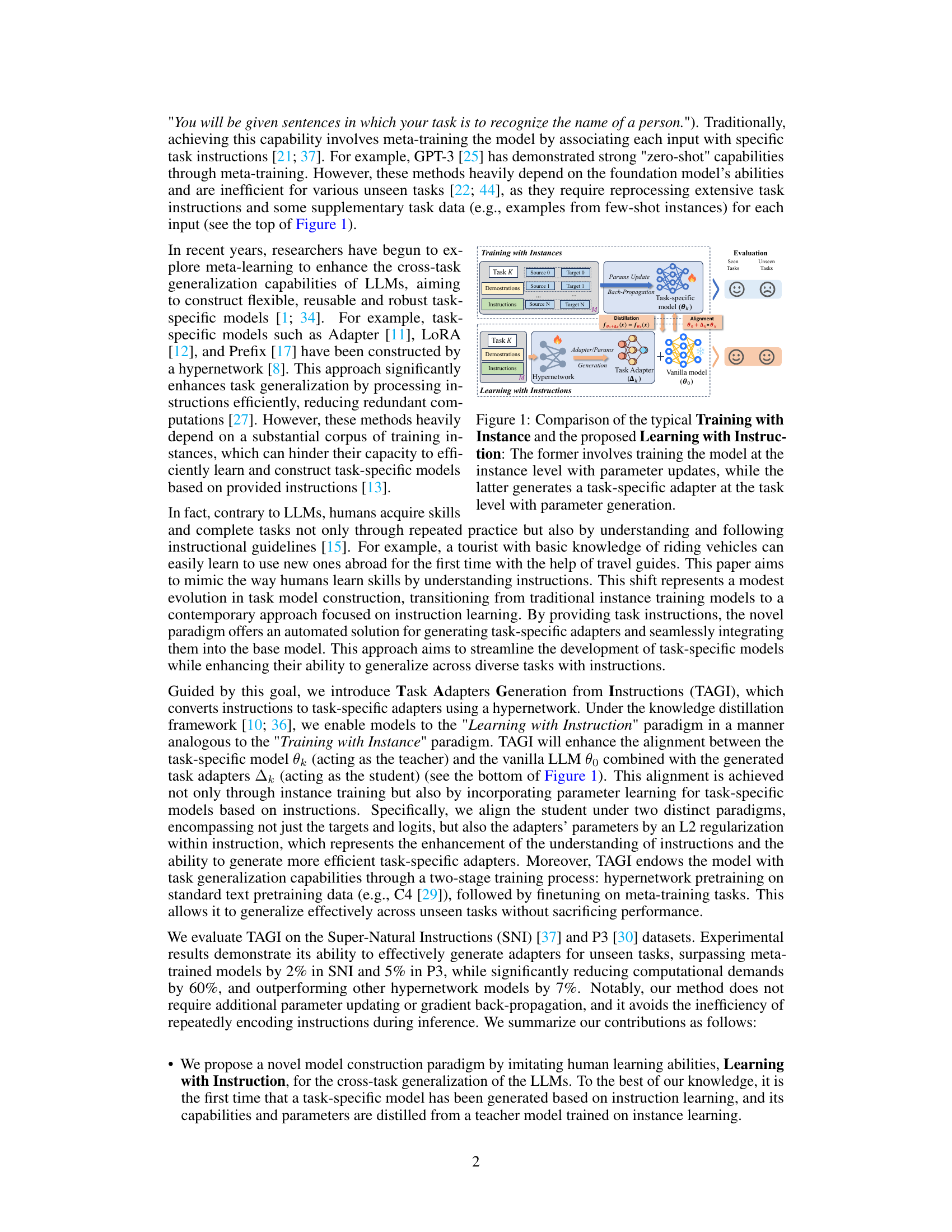

This figure compares two approaches to training language models: training with instances and learning with instructions. Training with instances involves updating model parameters through backpropagation on many labeled examples. Learning with instructions generates task-specific adapters using a hypernetwork that processes instructions instead of training on instance data. Both approaches are evaluated using seen and unseen tasks.

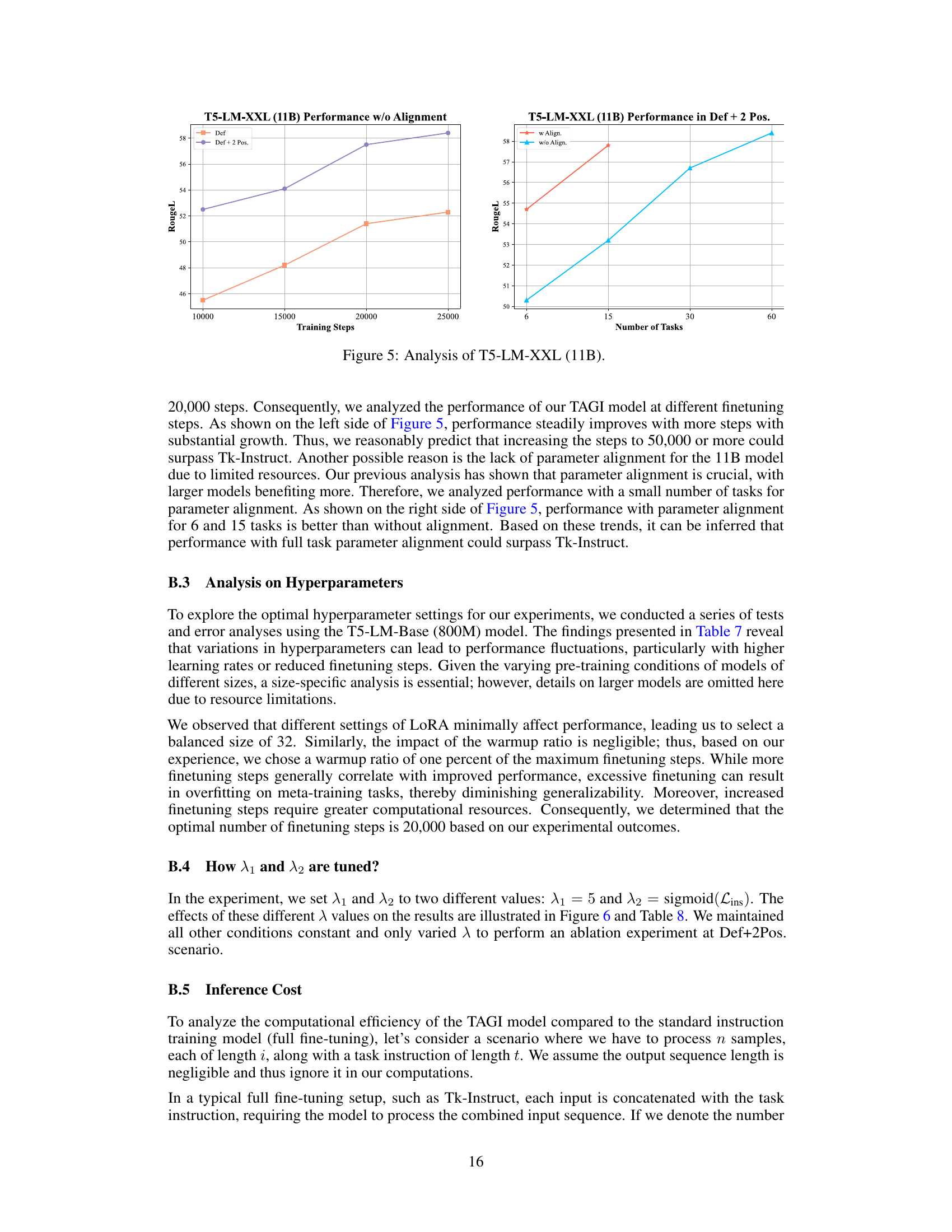

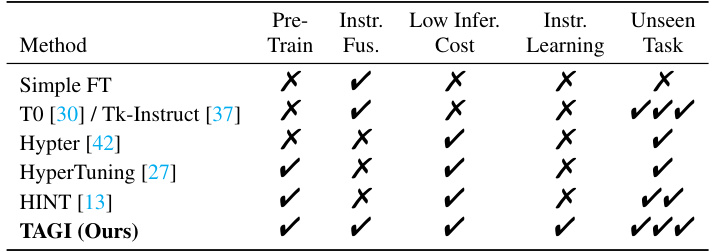

This table compares the proposed TAGI method with eight other baseline methods across several key characteristics. These characteristics include whether the method involves pre-training, instruction fusion, low inference cost, instruction learning, and the ability to handle unseen tasks. The table helps to highlight the advantages of TAGI over existing methods in terms of efficiency and generalization capabilities.

In-depth insights#

Instruction Learning#

Instruction learning, as explored in the context of large language models (LLMs), offers a compelling alternative to traditional instance-based training. Instead of relying on vast amounts of labeled data, instruction learning leverages natural language instructions to guide the model’s learning process. This paradigm shift mimics human learning, where instructions play a crucial role in skill acquisition. The core idea is to automatically generate task-specific adapters or parameters based solely on textual instructions, eliminating the need for extensive data annotation and retraining for each new task. This approach promises improved efficiency and enhanced cross-task generalization capabilities. However, challenges remain in ensuring the consistency and effectiveness of these automatically generated components, particularly when dealing with complex or ambiguous instructions. Knowledge distillation techniques can help align these automatically generated components with task-specific models trained traditionally, improving performance and generalization further. Therefore, while instruction learning presents a significant step towards more efficient and adaptable LLMs, future research needs to address the nuances of instruction interpretation and the robustness of automatically generated components.

TAGI Framework#

The TAGI framework presents a novel approach to adapting large language models (LLMs) to new tasks using instructions rather than extensive instance training. Its core innovation lies in automatically generating task-specific adapters using a hypernetwork that processes task instructions. This contrasts sharply with traditional methods that heavily rely on retraining with task-specific data. The framework incorporates knowledge distillation to align the generated adapters with those trained on instance data, thus improving the performance and consistency of the adapted model. A two-stage training process (hypernetwork pre-training and fine-tuning) further enhances the cross-task generalization capabilities of TAGI. The framework’s efficiency stems from generating task-specific parameters directly, avoiding costly retraining for each new task, and making it particularly suitable for low-resource settings. The use of LoRA parameter-efficient modules further contributes to its efficiency.

Hypernetwork Design#

A well-designed hypernetwork is crucial for the success of Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI). The encoder within the hypernetwork should efficiently transform task instructions into a concise, informative representation. This involves careful consideration of the input format (descriptions, demonstrations), embedding techniques, and architectural choices to minimize encoding biases and maximize information capture. The adapter generator should be parameter-efficient; capable of creating lightweight task-specific adapters without excessive computational cost. Knowledge distillation strategies can be integrated to align the hypernetwork outputs with pre-trained task-specific models. This alignment is important to improve performance and generalization. Finally, the architecture should be scalable, able to adapt to varying instruction lengths and complexities while maintaining efficiency. Careful consideration of factors such as the network depth, number of layers, activation functions, and regularization techniques is paramount for achieving both optimal performance and computational efficiency.

Cross-task Results#

A dedicated ‘Cross-task Results’ section would delve into the model’s performance across diverse, unseen tasks, showcasing its generalization capabilities. Key aspects would include a comparison against established baselines (e.g., few-shot learning methods) using relevant metrics (accuracy, F1-score, BLEU). Quantitative analysis would demonstrate the model’s ability to handle various task types without retraining, highlighting any strengths or weaknesses in specific domains. Qualitative analysis could involve analyzing the model’s outputs for nuanced understanding of its success or failure in complex tasks. Crucially, the results should assess the impact of specific components (e.g., the hypernetwork, knowledge distillation) on cross-task performance. Efficiency gains over traditional methods would be highlighted, demonstrating the practical advantages of the proposed approach.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI) could focus on enhancing cross-modal capabilities, enabling TAGI to handle diverse input types beyond text. Improving the efficiency and scalability of hypernetworks is crucial, exploring more efficient architectures or training strategies to reduce computational costs. Addressing the limitations of parameter-efficient adapters like LoRA warrants further investigation; exploring alternative approaches or developing more sophisticated adaptation methods is vital. Investigating the impact of different instruction formats and prompt engineering techniques is also crucial to better understand how to optimize instruction learning. Finally, rigorous evaluations on a wider range of tasks and datasets, including multilingual and low-resource scenarios, are necessary to demonstrate TAGI’s robustness and generalizability. Exploring theoretical underpinnings of TAGI could help establish its foundations and guide future improvements.

More visual insights#

More on figures

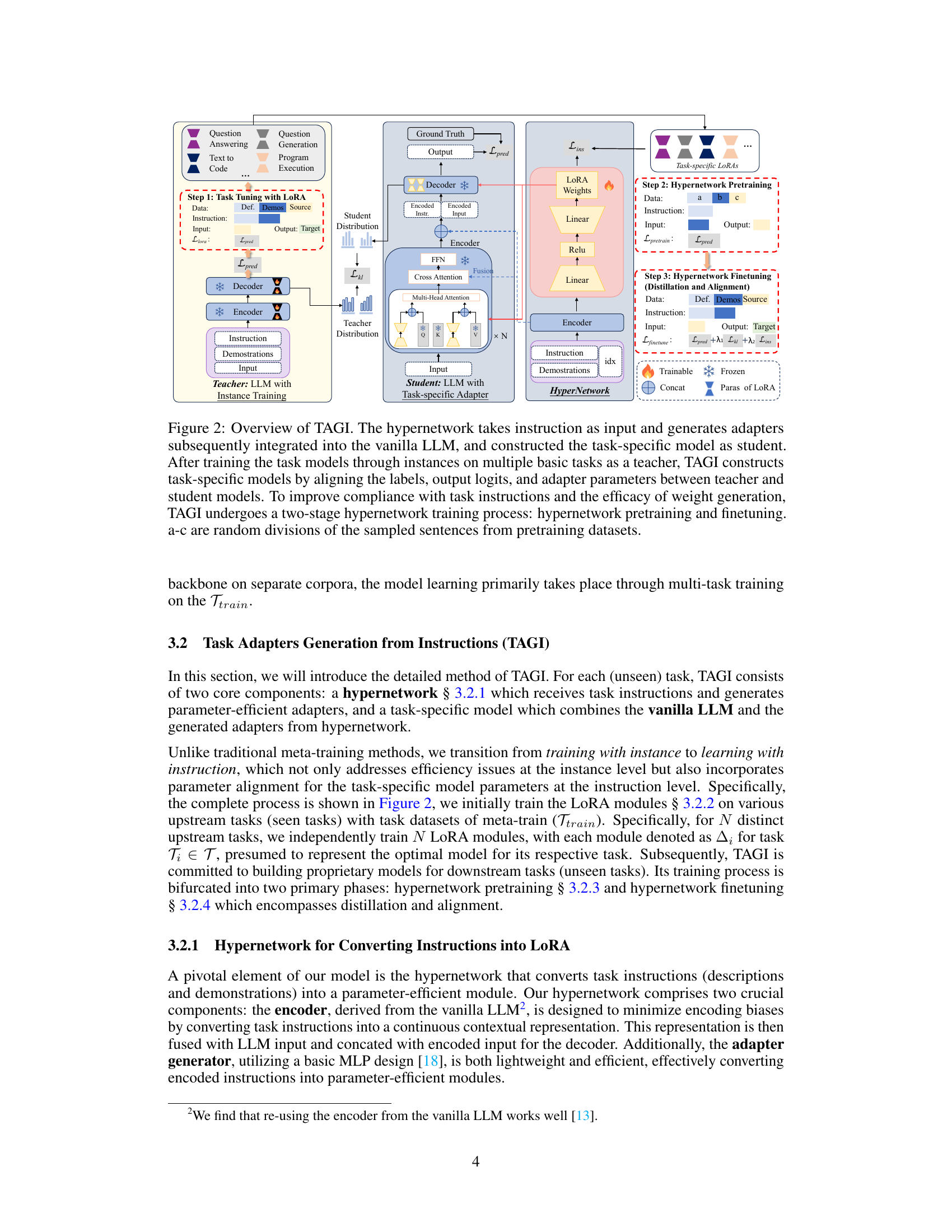

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI) model. It shows a two-stage training process. The first stage involves training a hypernetwork to generate task-specific adapters (LoRA modules) based on task instructions. These adapters are then integrated into a vanilla language model (LLM). The second stage involves knowledge distillation, aligning the student model (vanilla LLM + adapters) with a teacher model trained on instance-level data, matching outputs, logits, and adapter parameters. This alignment enhances consistency and improves generalization. The hypernetwork undergoes pretraining and finetuning steps to improve efficiency and performance.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of TAGI, a method that leverages instruction learning to enhance the cross-task generalization capabilities of LLMs. It comprises three main steps: 1. LoRA Tuning with Instance: Task-specific LoRA modules are trained on various upstream tasks using instance-based learning, establishing a teacher model. 2. Hypernetwork Pretraining: The hypernetwork is pretrained on standard text pretraining data, enabling it to generate effective adapters. 3. Hypernetwork Finetuning with Distillation and Alignment: The hypernetwork is finetuned to generate task-specific adapters based on instructions, aligning them with the teacher model through knowledge distillation and parameter alignment. The aligned student model enhances cross-task generalization.

This figure shows the architecture of the Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI) model. It illustrates the two-stage training process: first, a hypernetwork is pre-trained on general text data, then fine-tuned using knowledge distillation to align a student model (vanilla LLM + generated adapters) with a teacher model (trained on instances). The hypernetwork takes instructions as input and generates task-specific adapters, which are added to the vanilla LLM to create a task-specific model. The figure highlights the alignment of labels, output logits, and adapter parameters between the teacher and student models, emphasizing the model’s ability to learn from instructions and improve efficiency.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI) model. It shows a two-stage training process: hypernetwork pretraining and finetuning. The hypernetwork takes instructions as input and generates task-specific adapters, which are then integrated into a vanilla language model (LLM). The resulting model is trained on instances of multiple basic tasks, acting as the ’teacher’. A student model is constructed by aligning the labels, output logits, and adapter parameters of the teacher and student models. This alignment enhances compliance with task instructions and improves the efficiency of weight generation. The figure highlights the process of converting instructions into parameter-efficient modules (LoRA) and shows the two-stage hypernetwork training process for improved compliance with task instructions and more efficient weight generation.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the Task Adapters Generation from Instructions (TAGI) model. It shows a two-stage training process: First, a hypernetwork is pre-trained on general text data and then fine-tuned using a knowledge distillation technique. During fine-tuning, the hypernetwork learns to generate task-specific adapters (LoRA modules) from instructions. These adapters are integrated into a vanilla language model (LLM) to create a task-specific student model. The student model’s parameters are aligned with those of a teacher model trained on instances, to ensure consistency. This alignment is performed for labels, output logits, and adapter parameters. The entire process aims to improve the efficiency of adapting the LLM to unseen tasks by leveraging instructions rather than extensive instance-level training.

More on tables

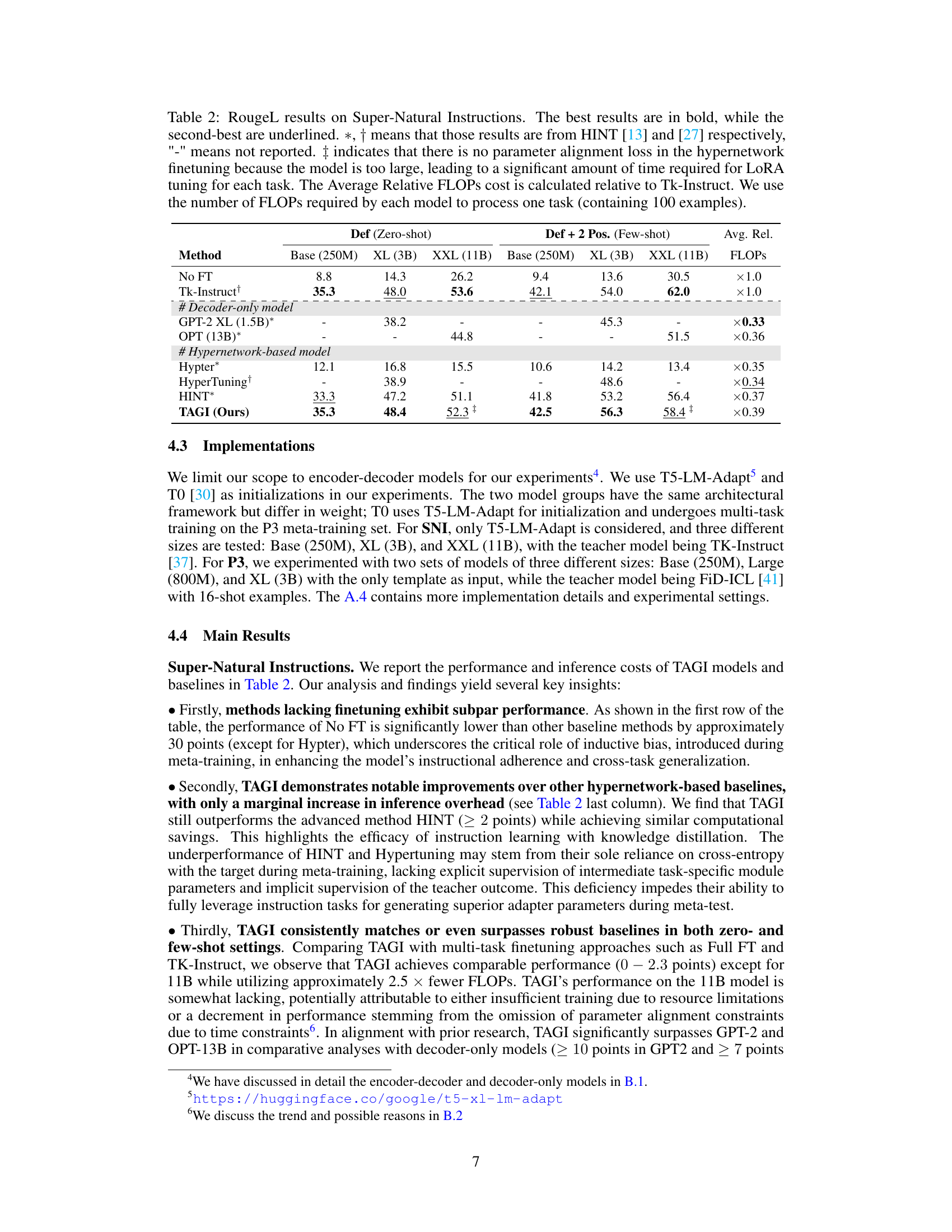

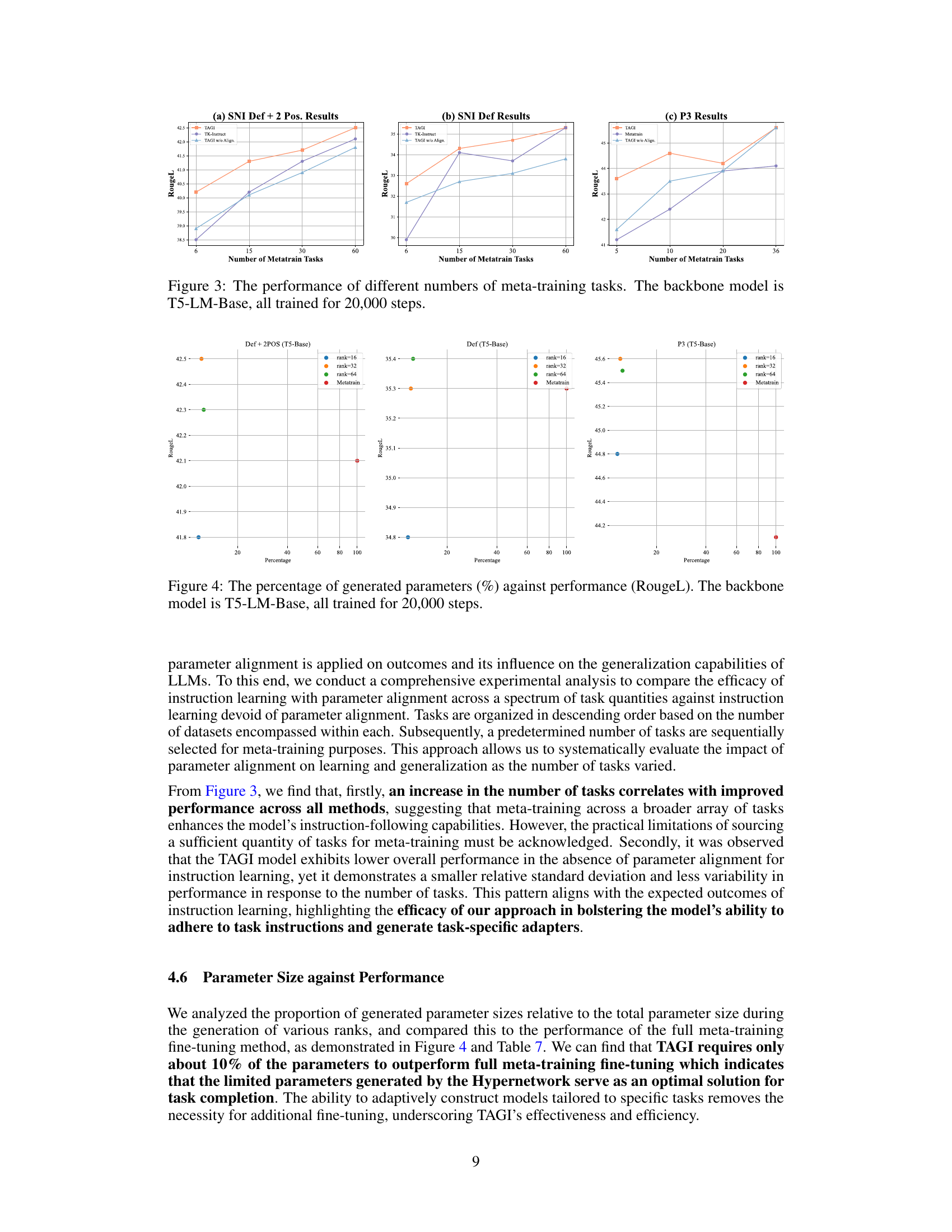

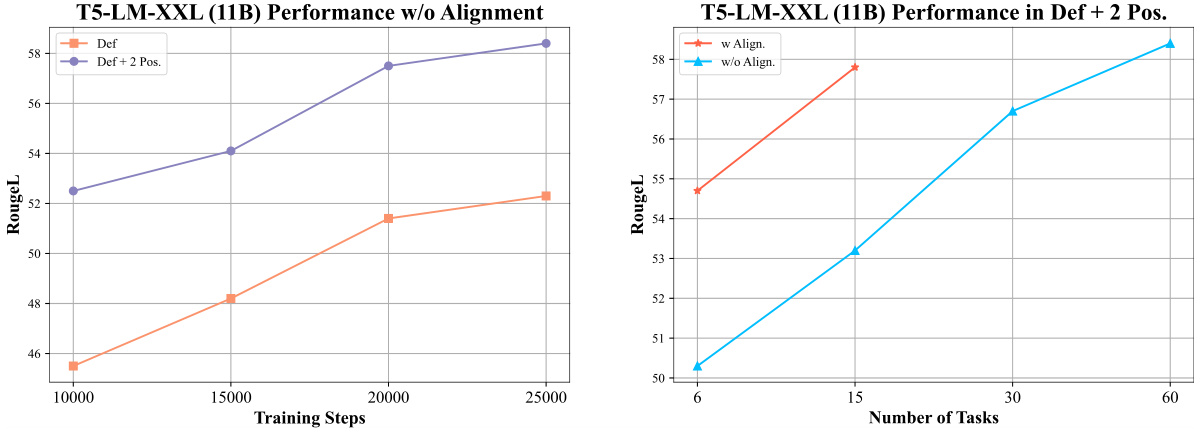

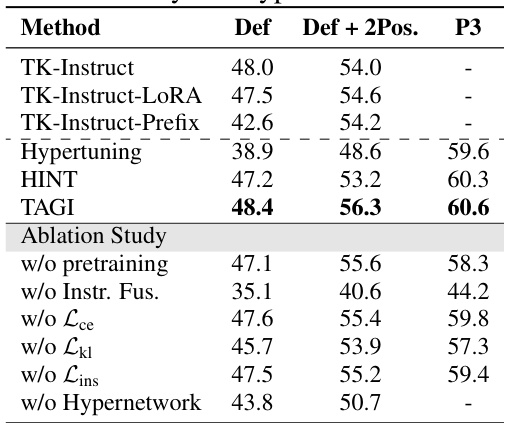

This table presents the performance of various models on the Super-Natural Instructions dataset, broken down by model size and whether zero-shot or few-shot learning was used. It compares the performance of TAGI to several baselines, including models without finetuning, hypernetwork-based models, and strong fully finetuned models. Key metrics include Rouge-L scores and relative FLOPs (floating point operations) cost.

This table presents the average accuracy results on the TO evaluation tasks of the P3 dataset after training on the TO P3 train set. It compares the performance of TAGI against several baselines, including zero-shot, full finetuning, meta-training, and other ICL-based and hypernetwork-based methods. The results show the average accuracy across the 11 meta-test tasks, and the average relative inference time, which is calculated relative to the meta-training baseline.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the TAGI model, showing the impact of removing various components on the model’s performance. The study used the T5-LM-XL (3B) model and trained for 20,000 steps. The evaluation was done on the P3 dataset as selected by the HyperT5 evaluation. The table shows the performance of the full TAGI model and also shows the effect of removing several key components: pretraining, instruction fusion, various loss functions, and the hypernetwork itself.

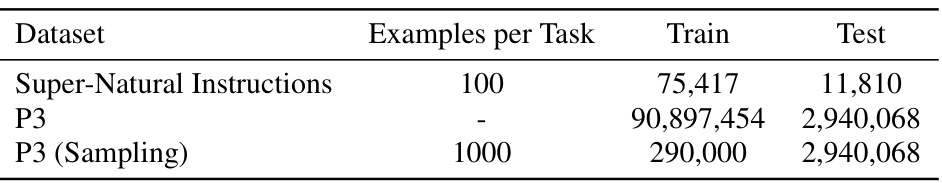

This table presents the number of training and testing samples used for each dataset in the experiments. It shows the number of examples per task and the total number of training and testing samples for Super-Natural Instructions, P3, and a sampled version of P3.

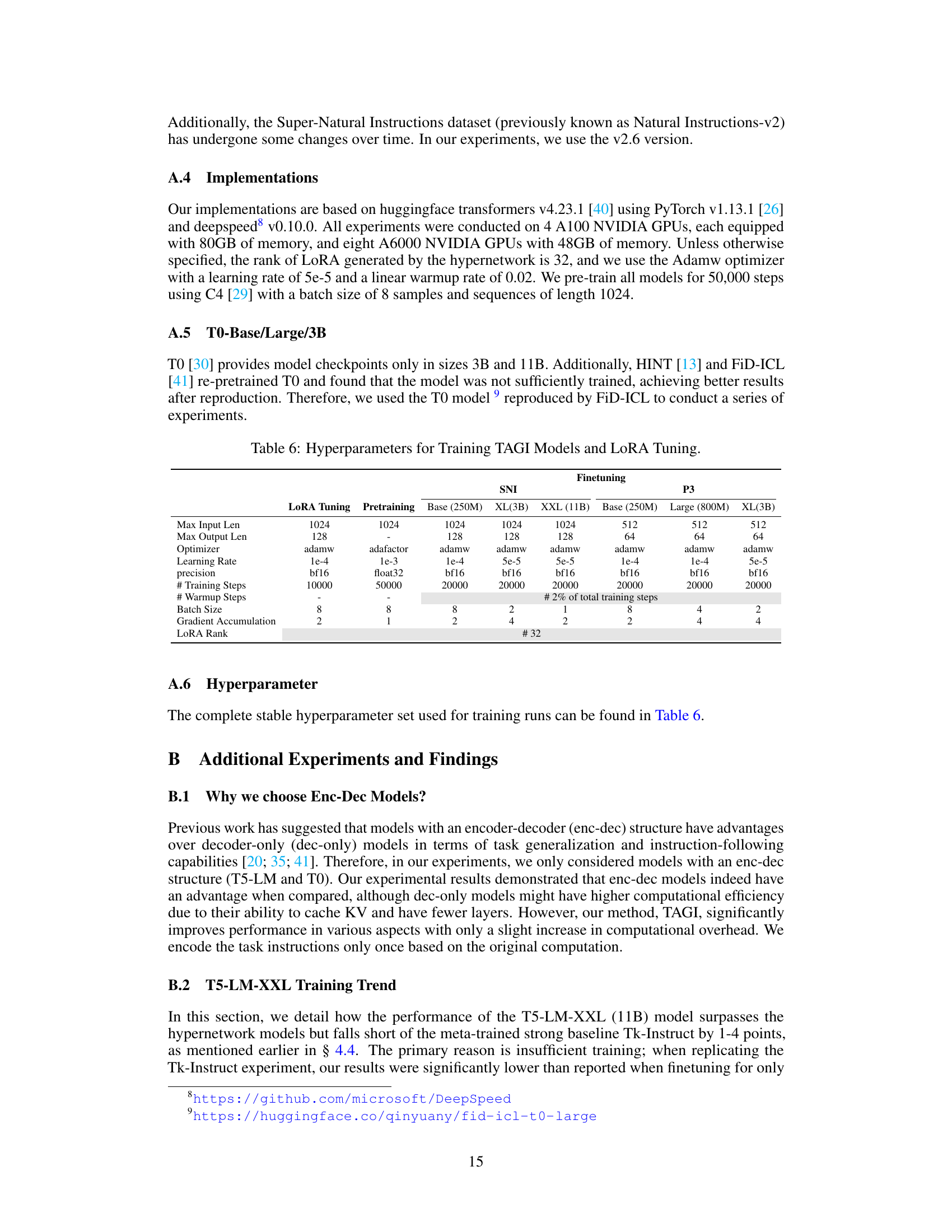

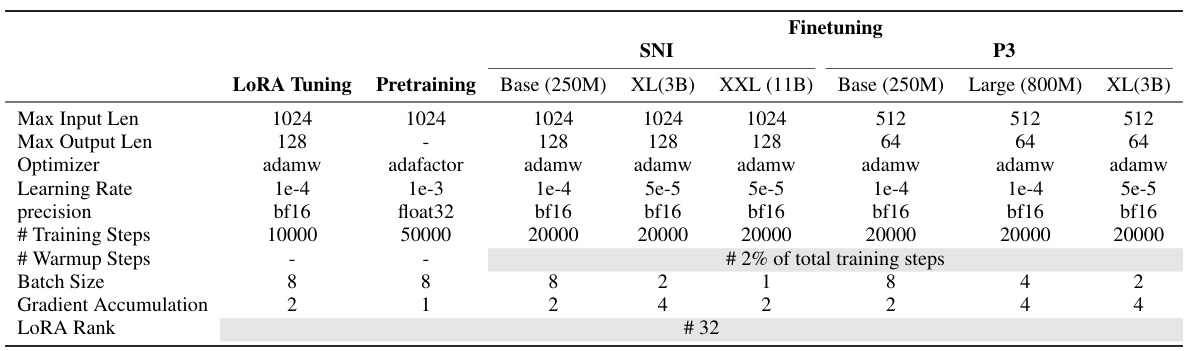

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the TAGI models and tuning the LoRA modules. It shows the settings for various parameters including maximum input and output lengths, optimizers, learning rates, precision, number of training and warmup steps, batch sizes, gradient accumulation steps, and LoRA rank. These settings are broken down separately for the LoRA tuning process, model pretraining, and finetuning on both the SNI and P3 datasets, with separate settings for different model sizes (Base, XL, XXL). The table provides a detailed view of the hyperparameter choices made for each stage of the model training process and aids in understanding and replicating the experimental results.

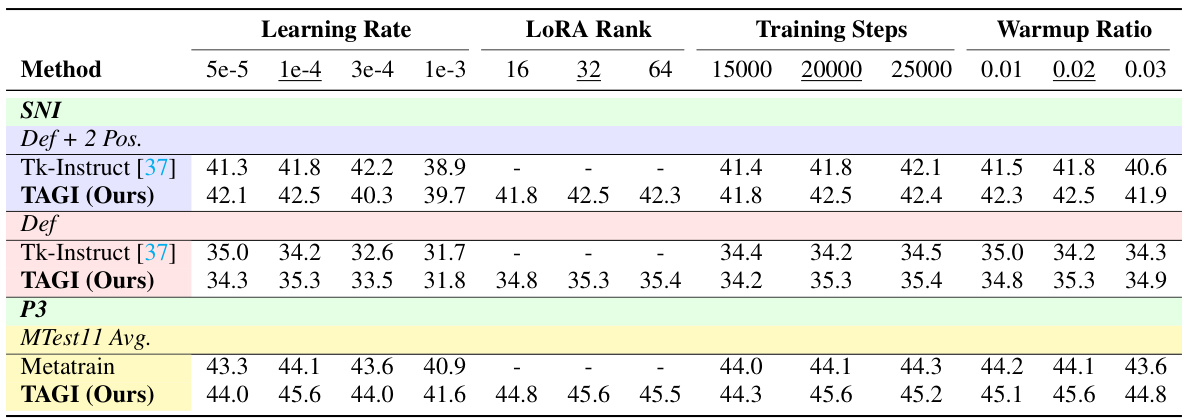

This table presents the ablation study on hyperparameters. It shows the performance variation of the T5-LM-Base model under different hyperparameter settings for the SNI and P3 datasets. The table displays results for different learning rates, LoRA ranks, training steps, and warmup ratios, highlighting how these factors affect performance on both datasets. The results are useful in determining the optimal hyperparameters for the TAGI model. The underlined values indicate the default hyperparameters used in the experiments.

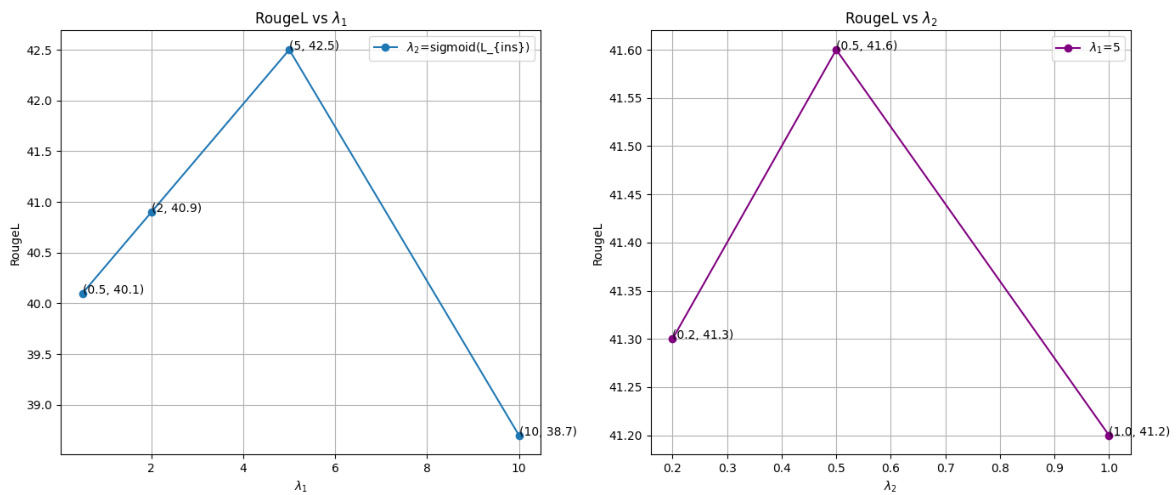

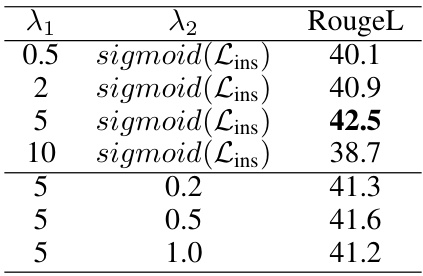

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the hyperparameters λ1 and λ2 used in the TAGI model. Different values for these hyperparameters were tested, and the resulting RougeL scores are reported. The study aims to determine the optimal balance between the two loss functions (knowledge distillation and parameter alignment) for improved performance.

This table compares the characteristics of different methods, including the proposed TAGI method, used in the paper for cross-task generalization. It provides a concise overview of each method’s approach and performance, highlighting key features like whether they use pre-training, instruction fusion, instruction learning, and their ability to generalize to unseen tasks.

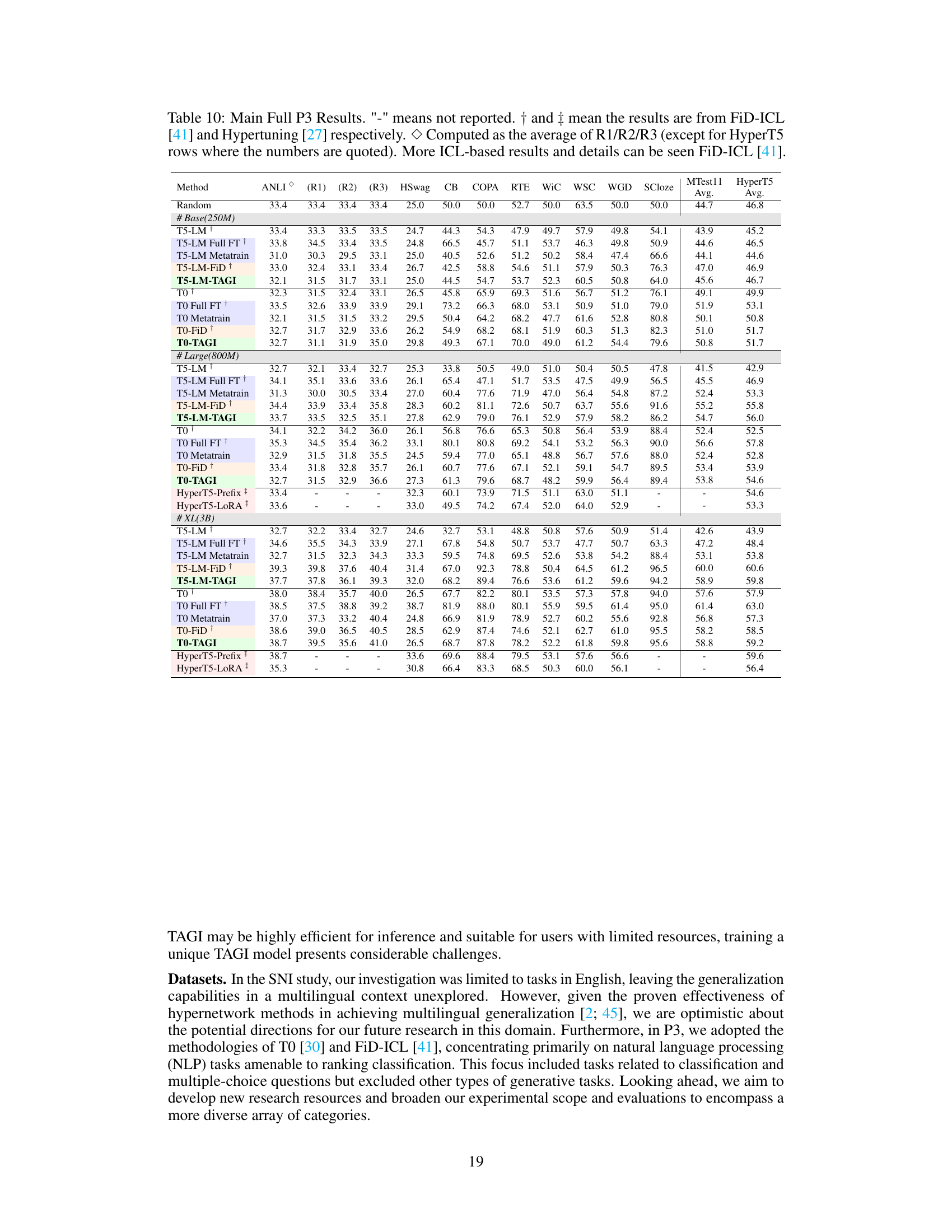

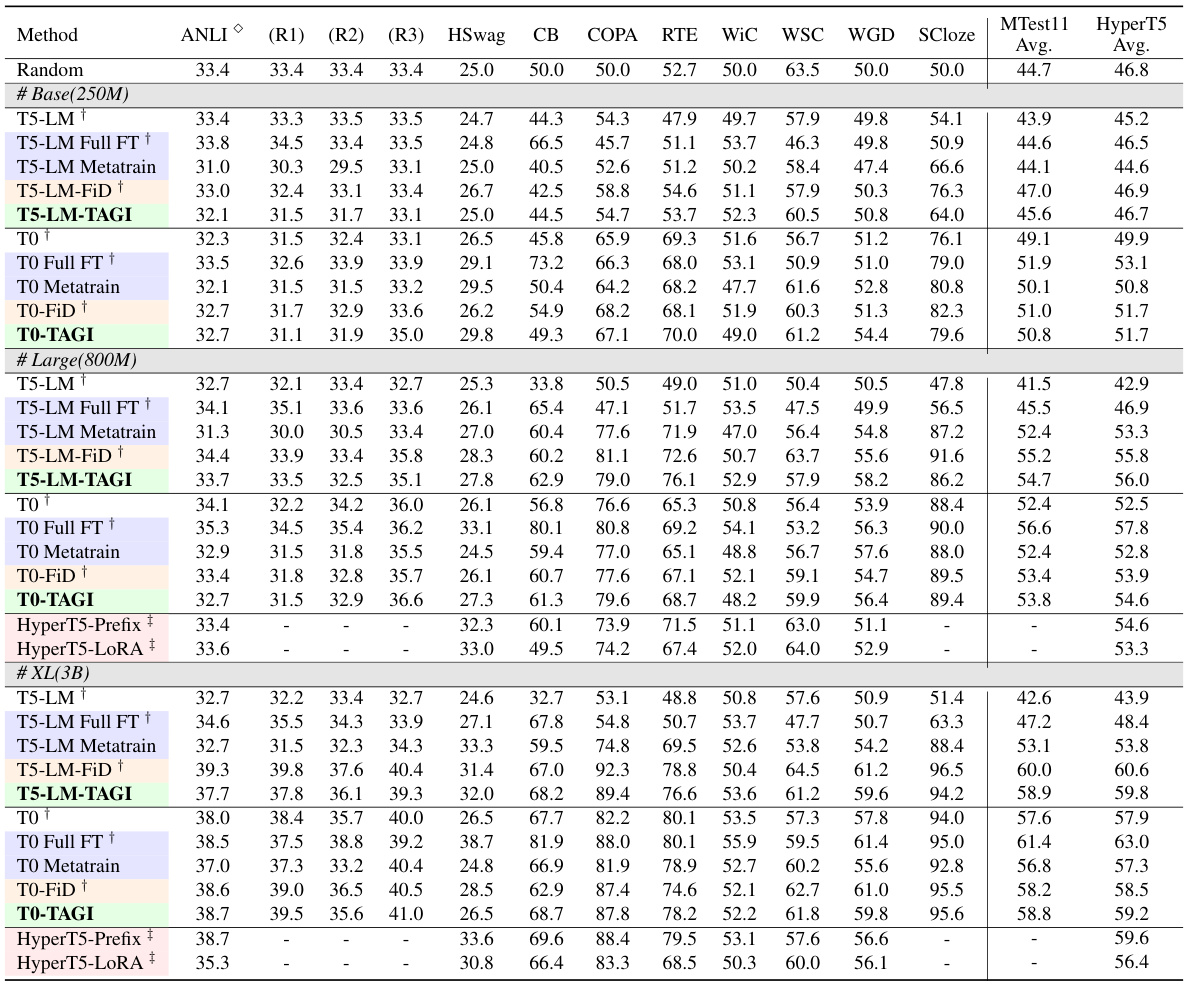

This table presents a detailed comparison of the performance of various models on the P3 dataset. It shows the average accuracy scores across different tasks, including ANLI (R1, R2, R3), Hswag, CB, COPA, RTE, WiC, WSC, WGD, SCloze, and the overall average across the 11 meta-test tasks (MTest11). The models compared include different baselines such as random, full finetuning (Full FT), meta-training (Metatrain), FiD-ICL, and Hypernetwork-based methods. The table also shows the results for different sizes of the T5-LM and TO models and HyperT5 model variations with different LoRA parameters, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of model performance and efficiency.

This table compares the proposed TAGI method with eight other baseline methods across several key characteristics. These characteristics include whether the method uses pretraining, instruction fusion, low-rank adaptation, low inference cost, instruction learning, and its ability to handle unseen tasks. The table helps to understand the advantages and disadvantages of TAGI compared to existing techniques.

Full paper#