↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Bayesian Optimization (BO) often uses a pre-defined budget as a stopping condition, which can be inefficient. This approach introduces uncertainty and lacks interpretability. Many BO methods lack effective, interpretable stopping rules. This hinders their practical use, particularly when evaluating solutions is costly. The existing rules either stop prematurely or late, and lack guarantees of convergence.

This paper proposes a novel probabilistic regret bound (PRB) approach. The method replaces the fixed budget by stopping when a solution within a pre-specified error bound of the optimum is found with a high probability. PRB uses Monte Carlo methods for efficient and robust probability estimations. This offers an adaptive stopping rule that can be tailored to specific problems and data. The approach is theoretically analyzed and empirically validated demonstrating improved efficiency and convergence compared to existing stopping techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in Bayesian Optimization as it tackles the significant challenge of developing effective stopping rules, enabling more efficient and interpretable optimization. It introduces a novel probabilistic regret bound (PRB) framework, offering model-based stopping criteria which adapt to the data. This opens new avenues for research, particularly in combining scalable sampling techniques with cost-efficient statistical testing for adaptive stopping. The PRB’s robust performance under varying conditions and its sample efficiency makes it a valuable contribution to the field.

Visual Insights#

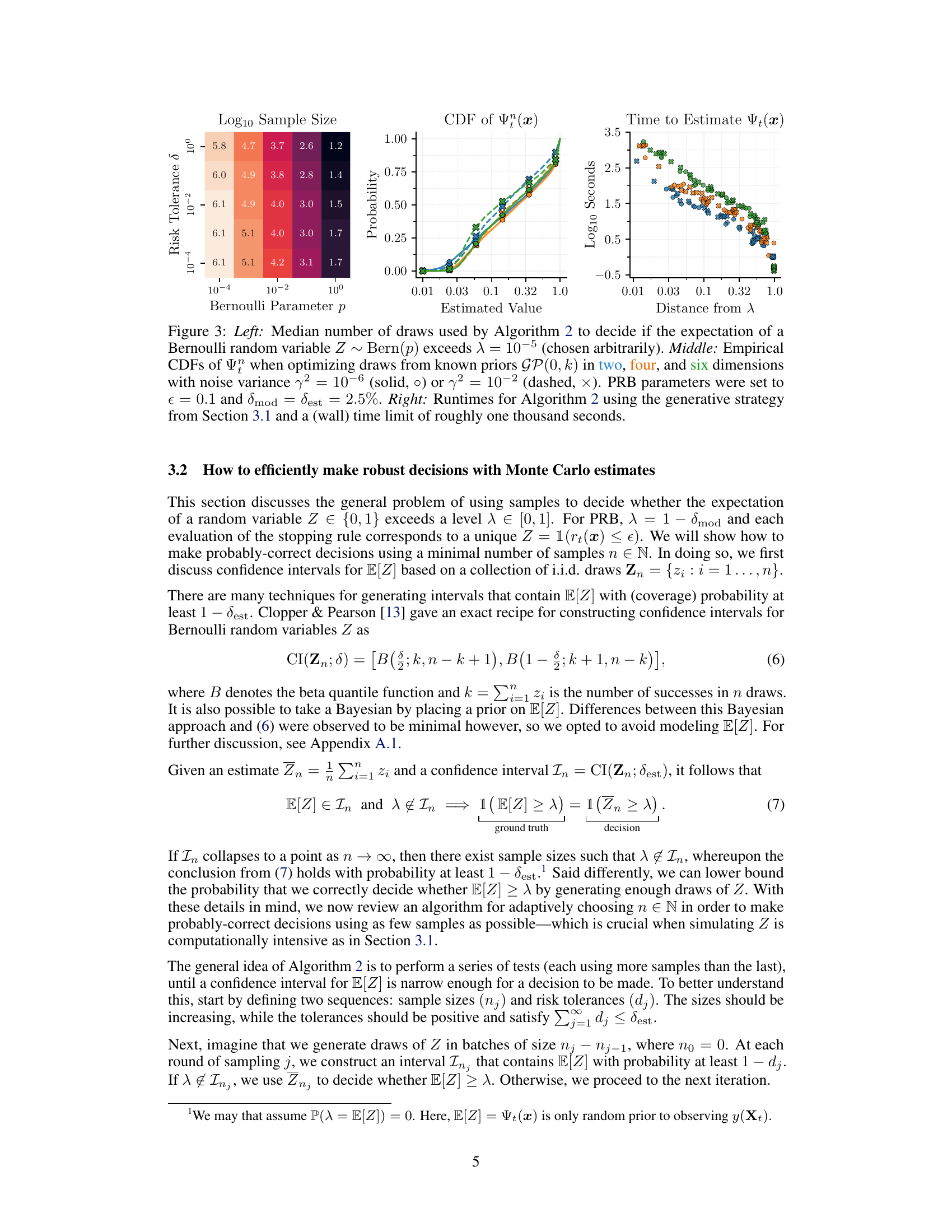

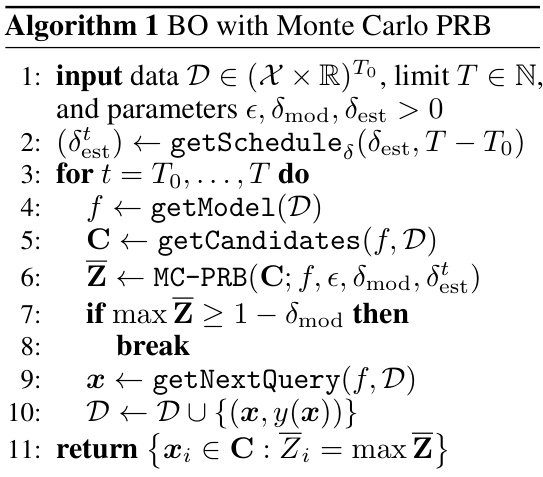

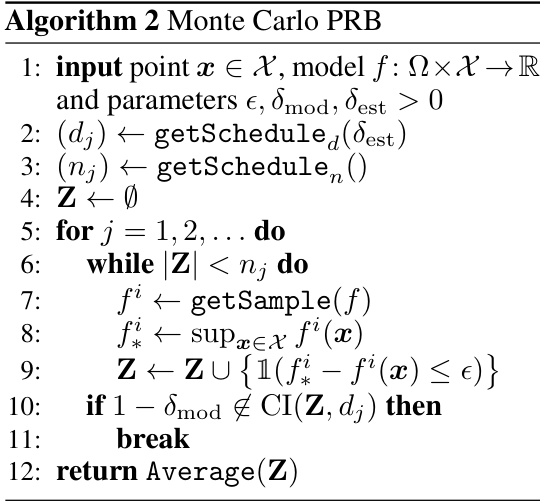

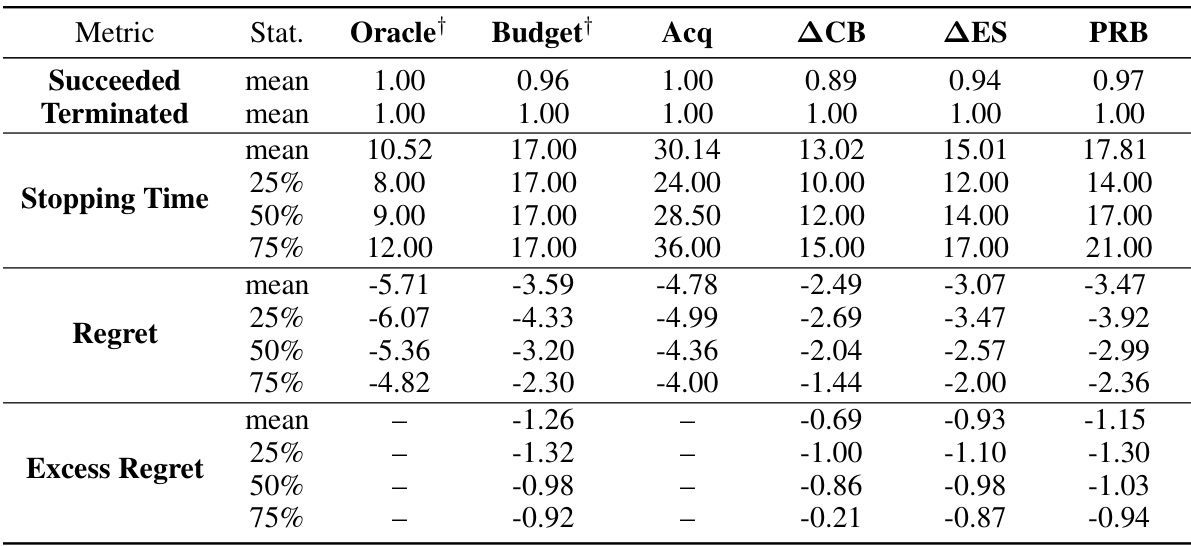

This figure visualizes the performance of the Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) stopping rule under different parameter settings. It shows how the percentage of runs stopped, the success rate (percentage of stopped runs that found an ε-optimal solution), and the median number of trials vary with different regret bounds (ε) and risk tolerances (δ). The results highlight the trade-off between stopping early and ensuring a high probability of finding a good solution.

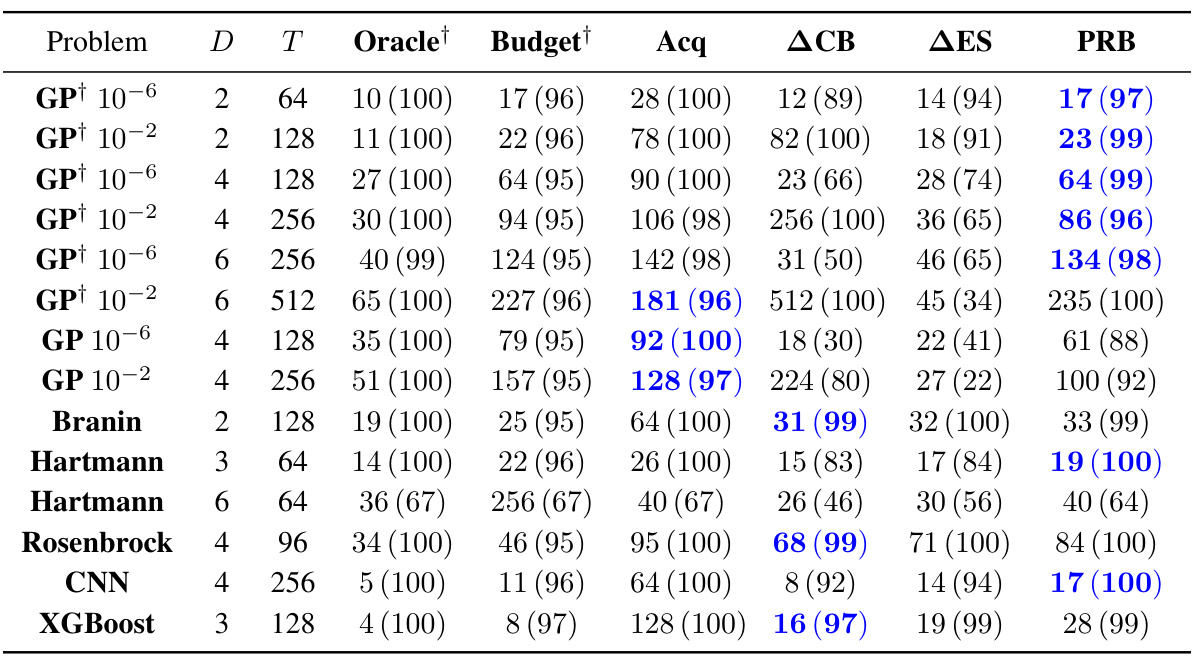

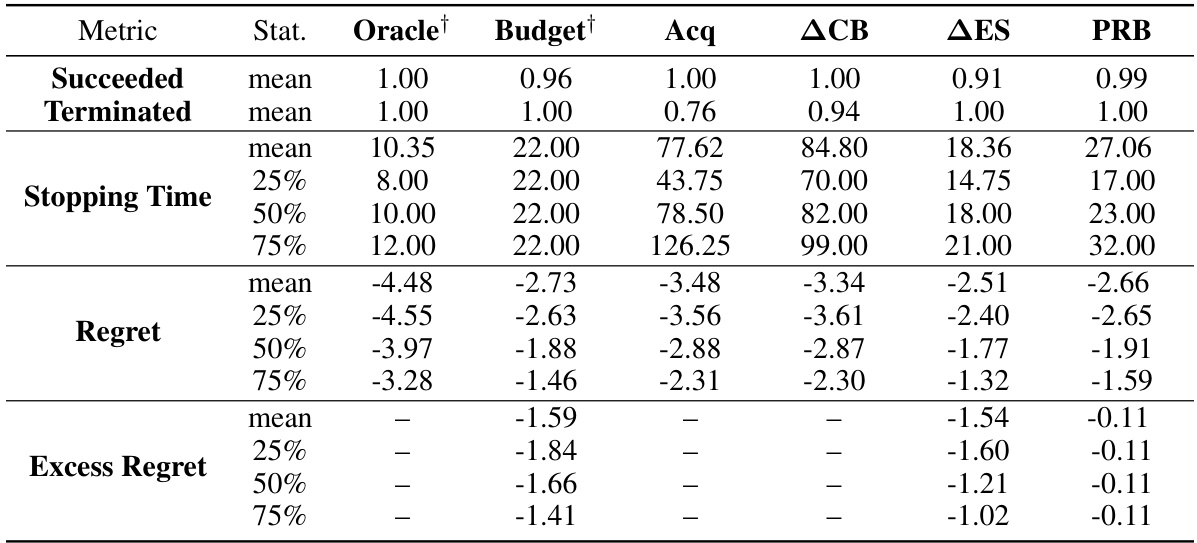

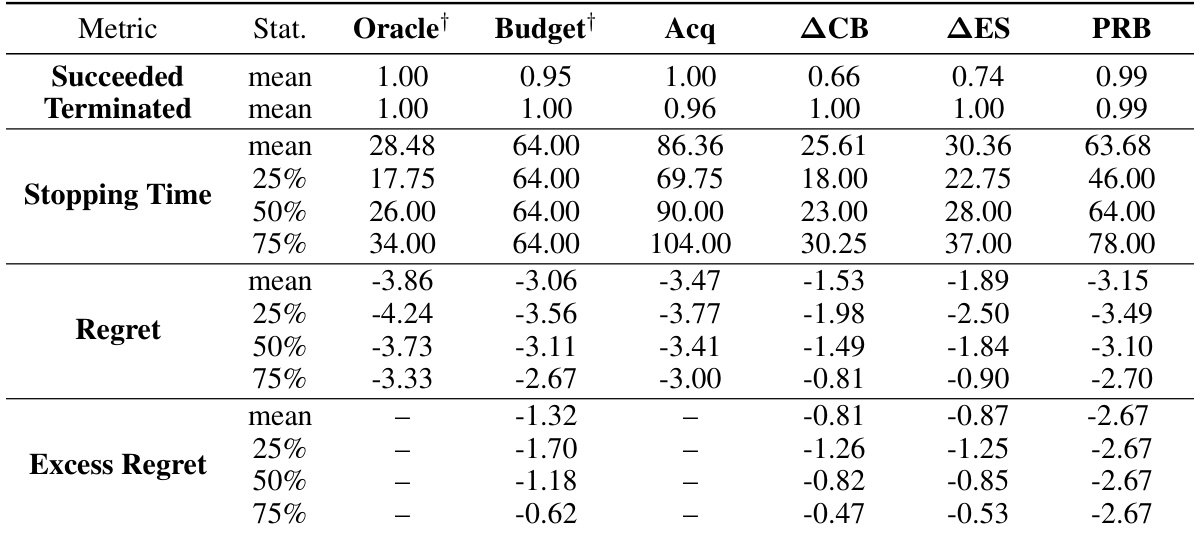

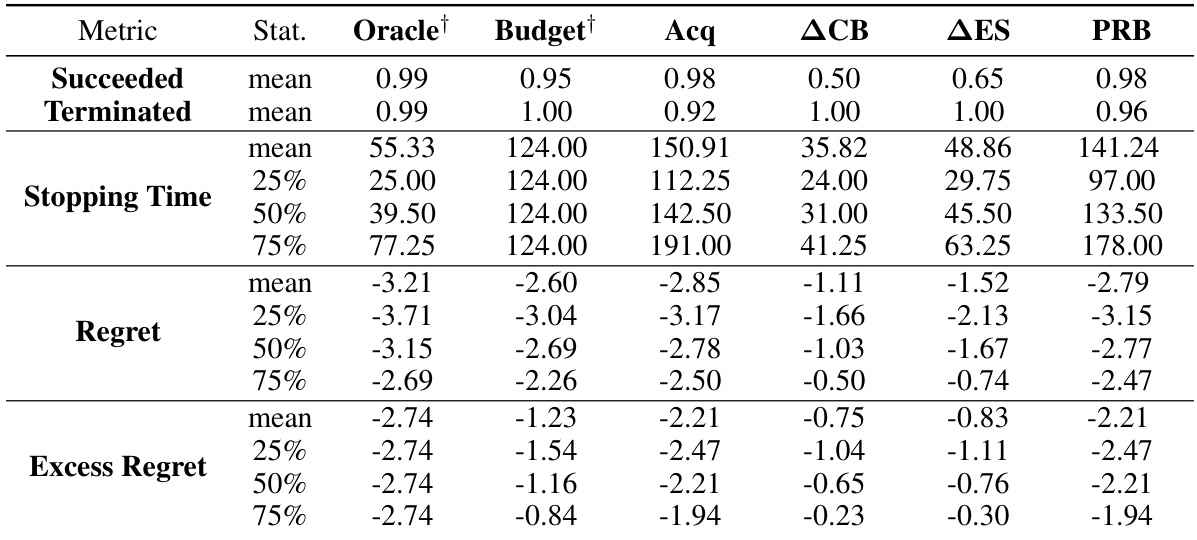

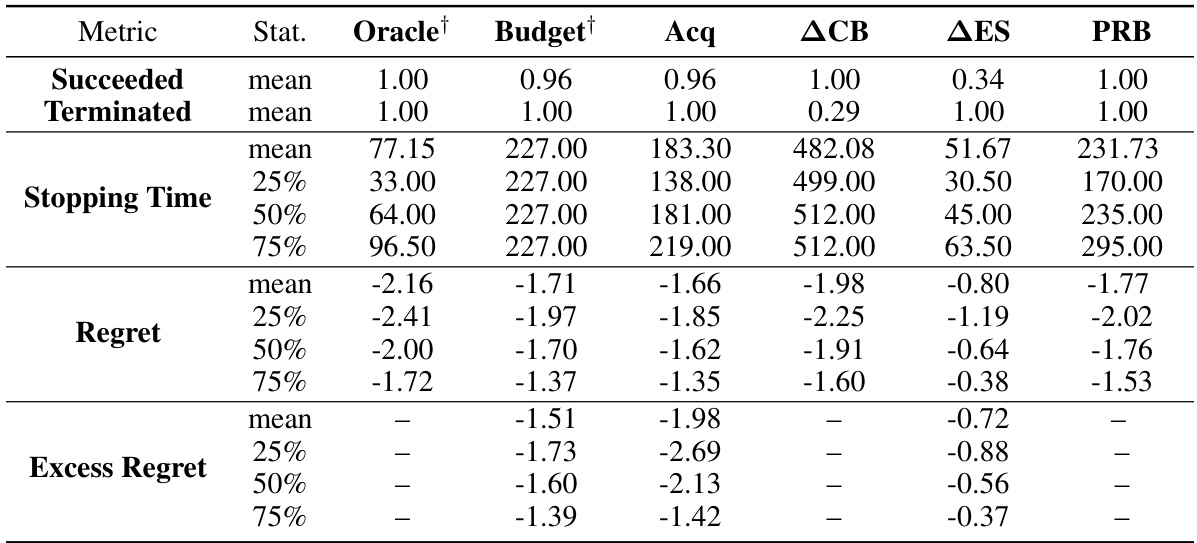

The table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates for different Bayesian optimization stopping rules across various benchmark functions. It compares the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method with several baselines (Oracle, Budget, Acq, ACB, AES), showing the median number of function evaluations needed to find a solution within ε of the optimum with probability at least 1-δ. The best-performing non-oracle methods are highlighted in blue. The table also includes the dimensionality (D) of the problem and the noise level (γ²) for Gaussian process (GP) objective functions.

In-depth insights#

Probabilistic Bounds#

The concept of “Probabilistic Bounds” in a research paper likely refers to using probabilistic models to define confidence intervals or regions around estimated quantities. This approach acknowledges the inherent uncertainty in many real-world systems, where point estimates alone are insufficient. Instead of providing single-valued predictions, probabilistic bounds quantify the uncertainty associated with those predictions. This could manifest as credible intervals from Bayesian models, confidence intervals from frequentist statistics, or more sophisticated methods. The value lies in providing a measure of reliability, allowing readers to assess the certainty of the results. Applications are numerous and include determining if a solution to an optimization problem is sufficiently good or understanding the uncertainty around parameters in a model. Therefore, “Probabilistic Bounds” offer a rigorous and nuanced perspective that advances scientific understanding and improves decision-making in settings with inherent variability.

Adaptive Sampling#

Adaptive sampling, in the context of Bayesian Optimization, is a crucial technique for efficiently exploring the search space. It dynamically adjusts the sampling strategy based on the information gathered so far, unlike uniform or random sampling which are static. This adaptability is particularly important when dealing with complex, high-dimensional problems, where exhaustive search is computationally prohibitive. The core idea is to focus sampling efforts on promising regions identified by the current model, which is often a probabilistic model like a Gaussian Process. This targeted sampling leads to faster convergence and better solutions by prioritizing the exploration of areas that are more likely to contain the optimum. However, adaptive sampling presents challenges: designing efficient algorithms to determine the next sample location is non-trivial, and the performance is sensitive to the choice of acquisition function and model accuracy. Careful consideration of these factors is key for successful application.

Robust Estimators#

Robust estimators are crucial in statistical analysis, especially when dealing with real-world data prone to outliers or noise. They provide reliable estimates even in the presence of unexpected deviations from assumed data distributions. The paper likely explores various types of robust estimators and compares their performance in the context of Bayesian Optimization. This would involve evaluating how well these estimators handle noisy or incomplete data, ensuring the optimization process is not unduly affected by anomalous data points. Efficiency in computation is a key consideration, since robust methods often involve iterative procedures, so the paper might also discuss strategies for efficiently calculating these estimates. A focus might be on how the robustness properties translate into overall reliability and efficacy of Bayesian optimization. The choice of robust estimators depends heavily on the characteristics of the data, making a thorough exploration necessary to determine the most suitable approach. Model assumptions regarding data distributions would play a significant role in this analysis.

Convergence Analysis#

A rigorous convergence analysis for Bayesian Optimization (BO) with probabilistic regret bounds would explore several key aspects. First, it must establish conditions under which the algorithm is guaranteed to terminate. This likely involves demonstrating that the probabilistic stopping criterion eventually becomes satisfied with probability one, a crucial step often involving demonstrating the almost sure convergence of the posterior distribution’s uncertainty measures. Establishing sufficient conditions for termination is vital for practical application. Second, the analysis must address the rate of convergence, characterizing how quickly the algorithm approaches an epsilon-optimal solution. Analyzing the convergence rate involves understanding the interplay between exploration and exploitation strategies within the BO framework and the inherent randomness of the probabilistic model. Finally, the sensitivity to model misspecification must be examined; a robust algorithm should demonstrate graceful degradation in the presence of modeling errors. Quantifying the impact of model misspecification is critical for real-world application where perfect model accuracy is rarely achievable. A comprehensive analysis would ideally combine theoretical convergence guarantees with empirical evidence to validate the theoretical findings and showcase the algorithm’s performance in realistic settings.

Model-Based Limits#

The heading ‘Model-Based Limits’ suggests an examination of the inherent constraints and potential weaknesses within model-based approaches to Bayesian optimization. A thoughtful analysis would explore how model inaccuracies (e.g., misspecification of the prior or likelihood, insufficient data) directly impact the reliability of stopping criteria based on probabilistic regret bounds. It would delve into the trade-off between computational cost and statistical accuracy, focusing on the challenges of efficiently estimating the probability of satisfying an epsilon-optimal condition. Assumptions underlying the model (e.g., smoothness of the objective function, noise characteristics) would be critically examined, along with their potential violation in real-world applications. A discussion of robustness would address how sensitive the method is to these limitations and potential remedies, such as incorporating uncertainty quantification or adaptive sampling techniques. Finally, the section should likely include a comparison to alternative stopping rules to showcase the relative strengths and weaknesses of model-based limits in Bayesian optimization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

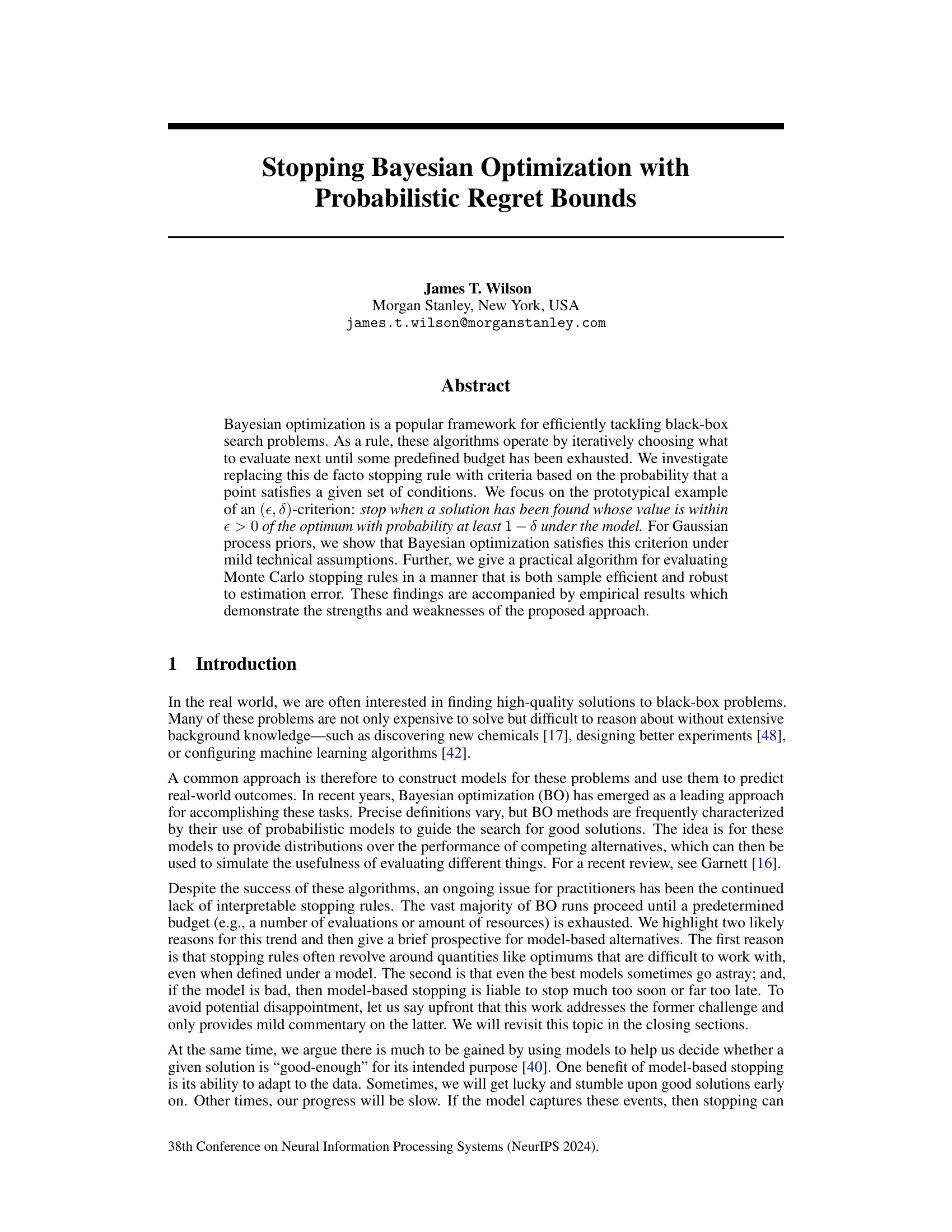

This figure shows three panels that illustrate the task of simulating whether a point x ∈ X satisfies the stopping condition, which is that the true function value f(x) is within epsilon of the optimum f*. The left panel shows the posterior mean and standard deviation of a Gaussian process (GP) model for the function f given noisy observations. The middle panel illustrates the simulation of ft using different methods (the proposed method and three competing methods), showing several draws from the posterior distribution of the GP model with the true function value overlaid. The right panel compares several estimators of the probability that the simple regret is less than epsilon.

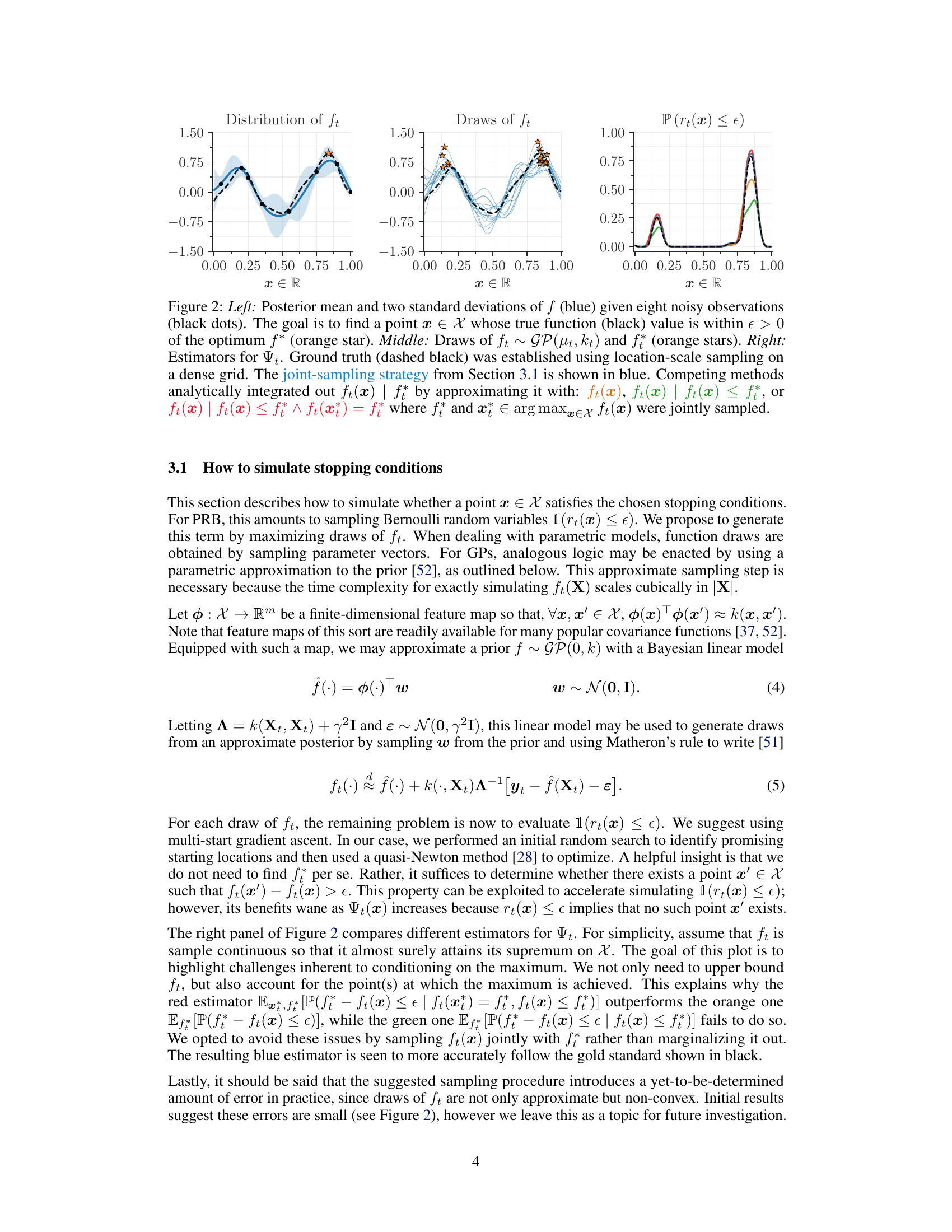

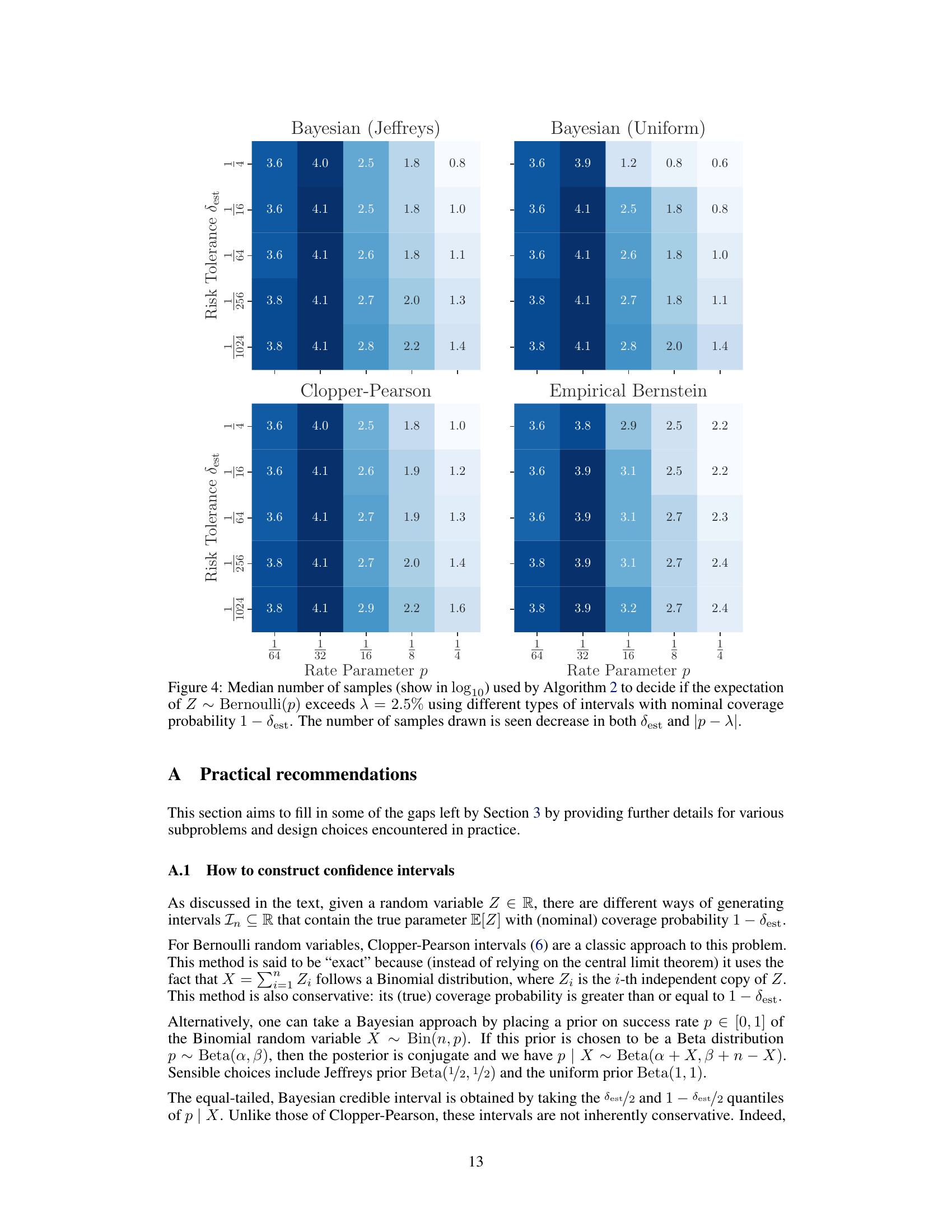

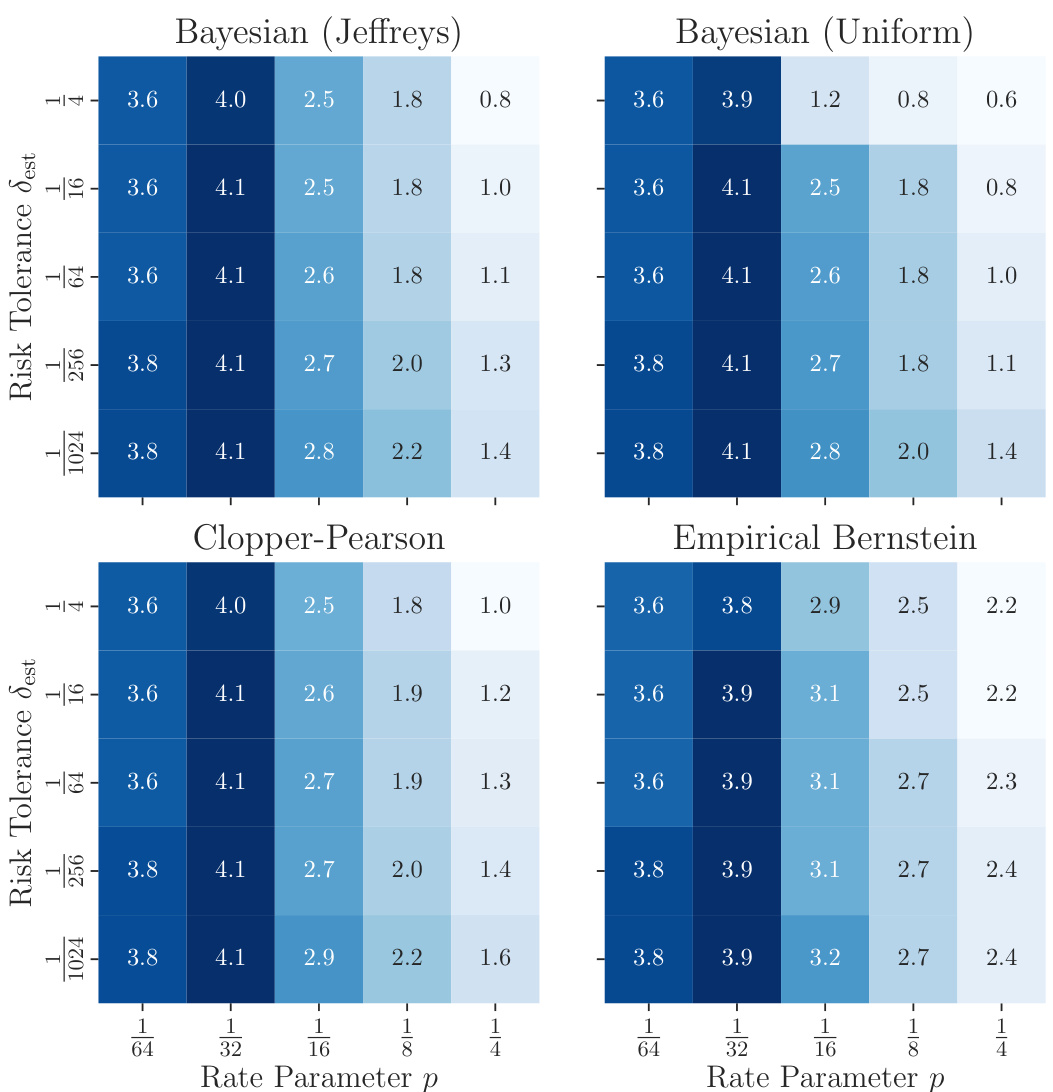

This figure summarizes the performance of Algorithm 2 for different settings. The left panel shows how many samples are needed to decide whether the expectation of a Bernoulli random variable exceeds a certain threshold, for various Bernoulli parameters and risk tolerances. The middle panel illustrates the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of the estimator Ψt under different conditions, showing that the estimator performs well in terms of accurately estimating the probabilities even for high-dimensional settings. Finally, the right panel shows that the algorithm can achieve efficiency in terms of runtime, which automatically adapts to the problem’s difficulty.

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the probabilistic regret bound (PRB) stopping rule. The experiment simulates a two-dimensional black-box function (f) sampled from a Gaussian process model. The figure displays the performance of the PRB stopping rule under varying parameters (€, δ, which control the desired accuracy and confidence of the solution). Three panels are shown: (left) Percentage of runs that stopped before a time limit (T=128), (middle) Percentage of runs that stopped and returned an e-optimal solution, and (right) Median number of function evaluations performed by the stopped runs. This illustrates the adaptive nature of the PRB rule, which automatically adjusts the number of evaluations required based on how quickly an acceptable solution is found.

More on tables

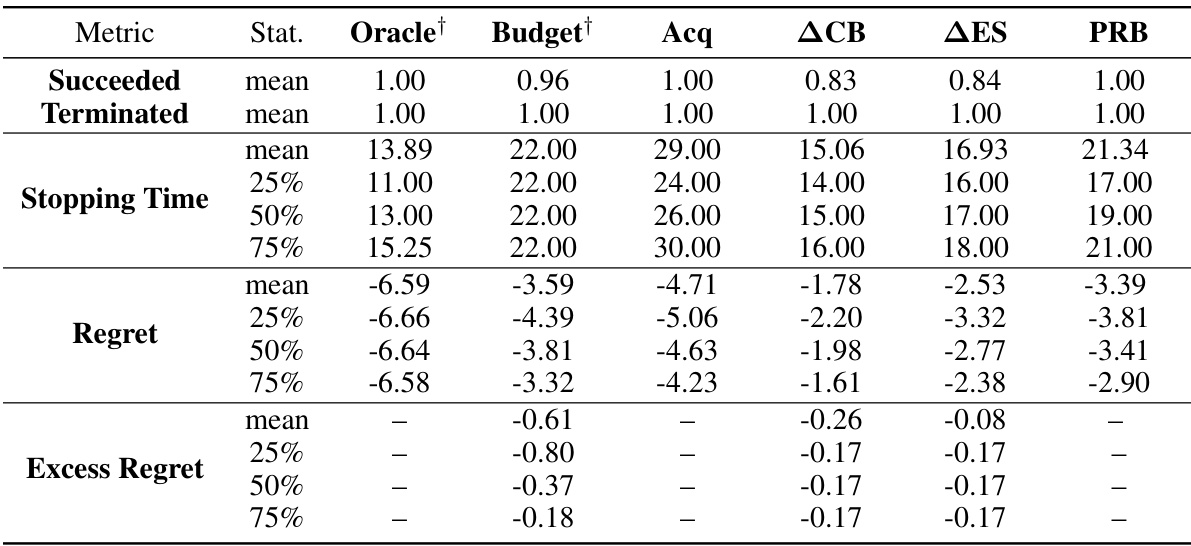

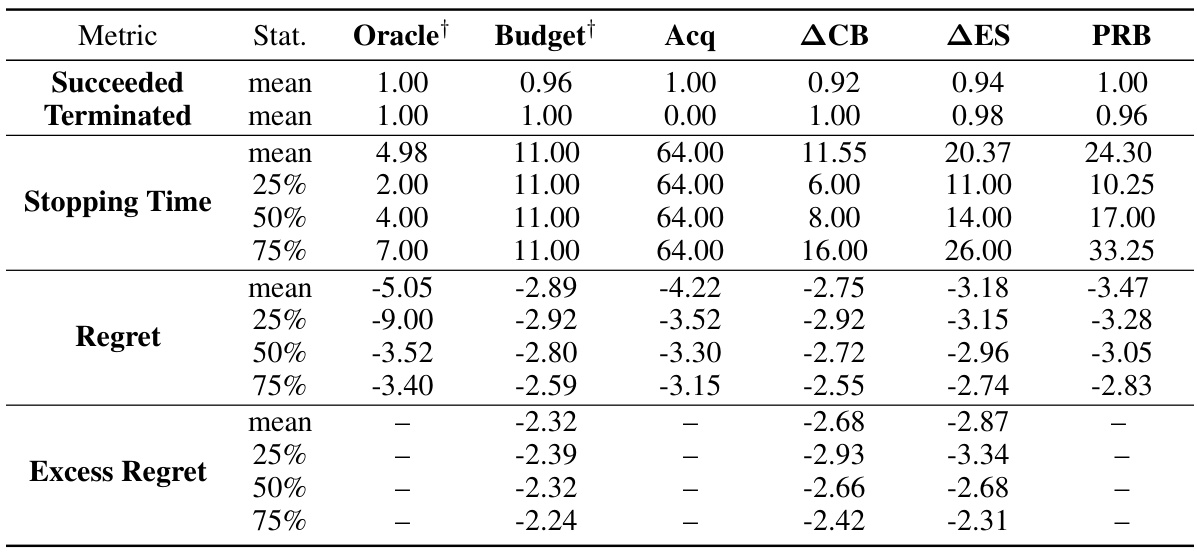

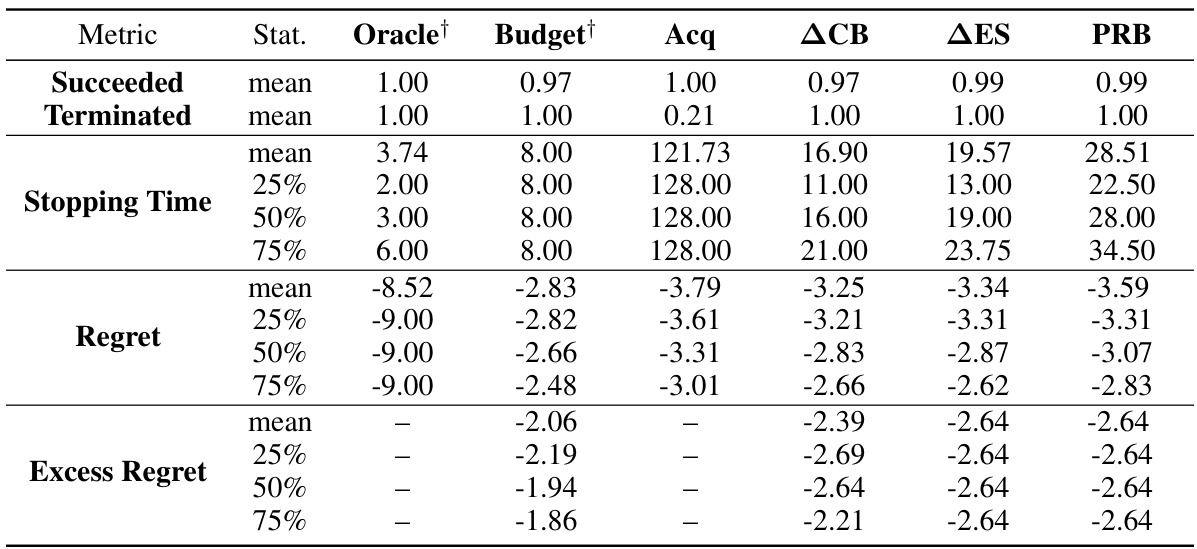

This table summarizes the performance of different stopping rules for Bayesian optimization across various test functions (GP, Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, CNN, XGBoost). For each function, the table presents the median number of function evaluations until a solution within ε of the optimum is found with probability at least 1-δ. The table compares six different stopping rules, including the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method, with success rates showing how often these rules actually returned an ε-optimal solution. The noise levels (γ²) are also specified for Gaussian Process objectives. Solutions found using the fewest function evaluations are highlighted in blue.

This table summarizes the performance of different stopping rules for Bayesian Optimization across various test problems. It shows the median number of function evaluations needed to find a solution within a specified error bound (€) of the optimum with a given probability (1-δ). The table compares the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method to several baseline methods, including an oracle, fixed budget, and acquisition function based methods (Acq, ACB, AES). Success rates (percentage of runs that found an ε-optimal solution) are also presented. Methods that achieved at least the desired success rate and used the fewest evaluations are highlighted in blue. The table highlights the impact of noise levels in the objective function and the influence of oracle information on stopping criteria.

The table presents the results of applying different stopping criteria to Bayesian Optimization runs on several test problems. For each problem, several metrics are compared, including median stopping times and the percentage of runs which successfully found an ε-optimal solution. Methods are compared against an oracle which knows the optimal solution and a budget-based approach (using an oracle to set the budget). The table highlights methods which used the fewest function evaluations while maintaining a high success rate, indicating the efficiency of different stopping rules.

This table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates for different stopping criteria across various benchmark problems. The problems include synthetic Gaussian process functions with varying noise levels and dimensions, as well as real-world problems such as hyperparameter tuning for a convolutional neural network (CNN) and XGBoost. The stopping criteria compared are an oracle (optimal stopping), fixed budget, acquisition function value, several model-based methods, and the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB). Success is defined as achieving an ε-optimal solution with at least 1-δ probability (ε and δ being hyperparameters). The table highlights the PRB method’s performance relative to other methods, indicating the number of function evaluations it required to achieve a similar success rate.

This table compares the performance of different stopping rules (Oracle, Budget, Acq, ACB, AES, PRB) for Bayesian Optimization across several problems with different dimensions and noise levels. It shows the median number of function evaluations before stopping and the percentage of runs that successfully found an ε-optimal solution. The best-performing methods (non-oracle) that achieved at least a 95% success rate with the fewest evaluations are highlighted in blue. The table helps to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) stopping rule compared to existing methods. Note that some methods were given oracle parameters for a fairer comparison.

The table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates of different Bayesian Optimization stopping rules for various benchmark problems. It compares the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method against several baselines, including an oracle (that knows the true optimum), a fixed budget, and other model-based methods. The problems encompass different dimensions and noise levels, allowing for a comprehensive comparison of the stopping rule performance. The best performing methods are highlighted.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing different stopping rules for Bayesian Optimization. For various benchmark problems (GP, Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, CNN, XGBoost) with different dimensions and noise levels, the table shows the median number of function evaluations needed to find a near-optimal solution (within ε of the optimum with probability at least 1-δ), as well as the percentage of successful runs that achieved this. The results are presented separately for oracle and non-oracle methods, with oracle methods having access to perfect information not typically available in practice. The table highlights methods that achieved the desired accuracy while using fewer evaluations, with those results marked in blue. This allows for a comparison of stopping criteria efficiency and performance in different problem settings.

This table summarizes the performance of different stopping rules for Bayesian Optimization on various test functions. It shows the median number of function evaluations until the stopping criterion was met, and the percentage of runs that successfully found an ε-optimal solution (within ε of the optimum with probability at least 1-δ). The table compares the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method against several baselines, including an oracle (which knows the optimal solution), a fixed budget, and several other model-based approaches. The best-performing method (in terms of fewest function evaluations while achieving at least the target success rate) is highlighted in blue for each problem. Different noise levels are tested for Gaussian process (GP) objectives, and the use of an oracle (which gives the algorithm the best parameters and budget) is noted. The problems include synthetic benchmark functions and more realistic machine learning hyperparameter tuning tasks.

This table summarizes the performance of different stopping criteria for Bayesian Optimization across various test functions. It shows the median number of function evaluations until termination and the percentage of successful runs (those finding a solution within ε of the optimum with at least 1-δ probability). Different noise levels and dimensions are tested. The table highlights the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method’s performance in comparison to several baselines, with the best-performing methods (fewest evaluations and high success rate) shown in blue. The ‘Oracle’ column represents an idealized scenario where the algorithm knows optimal solutions.

This table summarizes the performance of different Bayesian optimization stopping rules across various benchmark problems. For each problem, it shows the median number of function evaluations until stopping, the percentage of runs that successfully found a good-enough solution, and the best performing stopping rule (in blue). The problems include Gaussian process (GP) regression with varying noise levels, and several black-box optimization problems. The results highlight the relative efficiency and robustness of the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method compared to existing baselines, particularly in scenarios with significant model uncertainty or noise.

The table presents the results of the experiments comparing different stopping rules (Oracle, Budget, Acq, ACB, AES, PRB) for Bayesian optimization on various benchmark problems. For each problem, the median number of function evaluations until stopping and the percentage of successful runs (finding an ε-optimal solution with probability at least 1-δ) are reported. The table highlights the performance of the proposed PRB (Probabilistic Regret Bound) method, comparing its efficiency and success rate with established methods. The problems include synthetic Gaussian processes with varying noise levels and dimensions, along with several real-world black-box optimization problems (Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, CNN, XGBoost). Note that some methods used oracle information (indicated by †) to set hyperparameters or stopping criteria for a fairer comparison.

The table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates for different Bayesian optimization stopping rules on various benchmark problems. The problems include synthetic functions generated from Gaussian Processes with different noise levels, and real-world problems such as hyperparameter optimization for a convolutional neural network (CNN) on the MNIST dataset and an XGBoost model for income prediction. The stopping rules compared are: Oracle (optimal stopping time with perfect knowledge), Budget (predefined number of evaluations), Acquisition (stopping when acquisition function values are negligible), ACB (stopping when the gap between upper and lower confidence bounds is small), ∆ΕΣ (stopping when the difference in expected supremums between consecutive steps is small), and PRB (the proposed probabilistic regret bound). The best-performing non-oracle method for each problem is highlighted in blue. The table shows that the PRB method performs competitively with oracle methods, often with the fewest evaluations.

This table presents the median stopping times and success rates of different Bayesian Optimization (BO) stopping rules for various test functions. The goal is to find a solution within ε of the optimum with probability at least 1-δ. The table compares the performance of the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method against several baselines. Metrics include the median number of function evaluations performed before stopping and the percentage of successful runs (finding an ε-optimal solution). The table highlights the situations where PRB performs best, indicating when its adaptive nature provides benefits.

This table summarizes the performance of different stopping rules in Bayesian optimization across various benchmark problems. It shows the median number of function evaluations required to reach an e-optimal solution, along with the percentage of successful runs that achieved this. The problems include both synthetic (Gaussian processes with varying noise levels) and real-world (hyperparameter optimization for neural networks and gradient boosting) tasks. The table highlights the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method’s performance compared to several baselines, indicating its effectiveness in finding good solutions efficiently.

This table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates for different Bayesian optimization stopping rules across various benchmark problems. The problems include Gaussian process (GP) regression problems with varying dimensionality (D) and noise levels, along with the Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, convolutional neural network (CNN) training, and XGBoost hyperparameter tuning tasks. The stopping rules compared are: Oracle (optimal stopping time with perfect knowledge), Budget (predefined evaluation budget), Acquisition function (stopping when the acquisition function value is negligible), ACB (stopping when upper and lower confidence bounds are close), ∆ΕΣ (stopping based on the change in expected improvement), and the proposed PRB (probabilistic regret bounds) method. The table highlights the performance of each method in terms of the number of function evaluations required to achieve a 95% success rate (finding an ε-optimal solution with at least 95% probability). Methods shown in blue achieved this success rate with fewer function evaluations than others.

This table presents the median stopping times and success rates of different Bayesian Optimization stopping rules on various test functions. The test functions include synthetic Gaussian Processes (GPs) with varying noise levels and dimensionality, as well as real-world problems such as the Branin function, Hartmann functions, Rosenbrock function, and optimization tasks for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and XGBoost models. The table compares the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) stopping rule to several baseline methods, including an oracle, a fixed budget, and methods that rely on acquisition functions, confidence bounds, or changes in the expected supremum. The best performing method for each problem (non-oracle) is highlighted in blue. The table provides insights into the performance and efficiency of the proposed PRB stopping rule in various settings.

This table summarizes the performance of different Bayesian optimization stopping rules across various test problems. It presents the median number of function evaluations required to reach a solution and the percentage of trials where such a solution is within a specified tolerance (ε) of the true optimum with a given probability (1-δ). The test problems include Gaussian processes with different noise levels and dimensions, as well as several common benchmark black-box optimization functions (Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock) and real-world problems (CNN hyperparameter tuning, XGBoost hyperparameter tuning). The ‘Oracle’ column represents the optimal stopping time given perfect knowledge; other columns show the performance of the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method and several baseline methods. Methods achieving the highest success rate with fewest evaluations are highlighted.

The table presents the median stopping times and success rates of different Bayesian Optimization stopping rules for various benchmark functions. It compares the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method against several baselines, including an oracle, fixed budget, and other model-based approaches. The functions tested include Gaussian Processes (GPs) with varying noise levels and dimensionality, as well as more complex functions such as Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, a convolutional neural network (CNN) on MNIST, and XGBoost on the Adult dataset. The table highlights which methods successfully returned ε-optimal solutions (i.e., solutions within ε of the optimum) with at least 1-δ probability, and it indicates which non-oracle method achieved this with the fewest function evaluations for each problem.

This table summarizes the performance of different Bayesian Optimization (BO) stopping rules on various benchmark functions, including Gaussian process (GP) regression tasks with varying noise levels, and real-world problems such as hyperparameter optimization for convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and XGBoost models. For each problem and stopping rule, the table reports the median number of function evaluations (stopping time) required to find a solution within a specified error tolerance (ε) with at least a specified probability (1-δ). The ‘success rate’ indicates the percentage of runs that successfully found an ε-optimal solution. The table highlights the proposed Probabilistic Regret Bound (PRB) method and compares it to several baseline methods (Oracle, Budget, Acq, ACB, AES), indicating instances where PRB outperforms other methods in terms of efficiency and/or success rate. The color-coding helps to identify the best-performing non-oracle method for each problem.

This table presents the median number of function evaluations and success rates for different Bayesian optimization stopping rules across various test functions. It compares the proposed probabilistic regret bound (PRB) method against several baseline methods (Oracle, Budget, Acq, ACB, ∆ΕΣ). The test functions include Gaussian process (GP) functions with different noise levels and dimensions, and real-world black-box functions like Branin, Hartmann, Rosenbrock, CNN (convolutional neural network on MNIST), and XGBoost. The table highlights the performance of each method in terms of the number of evaluations required to find an ε-optimal solution with at least 1-δ probability, showing which methods are most efficient in various scenarios.

Full paper#