↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are rapidly advancing but their safety remains a critical concern. Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) is an effective method to assess LLM safety by generating adversarial prompts, but its computational cost is high, limiting comprehensive studies. Existing methods like speculative sampling are unsuitable for optimizing discrete tokens in GCG.

This paper introduces Probe Sampling, a novel algorithm that addresses these issues. By dynamically assessing the similarity between a smaller ‘draft’ model’s and the target LLM’s predictions, Probe Sampling effectively filters out many unpromising prompt candidates. This results in significant speed improvements (up to 5.6x) while maintaining or improving attack success rates. Furthermore, the approach successfully accelerates other prompt optimization techniques, demonstrating its broad applicability and potential for future research in LLM safety and beyond.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for enhancing the efficiency of LLM safety research by significantly accelerating the optimization process of adversarial prompt generation. It offers a novel approach applicable to various prompt optimization techniques, opening new avenues for comprehensive LLM safety studies and potentially impacting other fields utilizing similar optimization challenges.

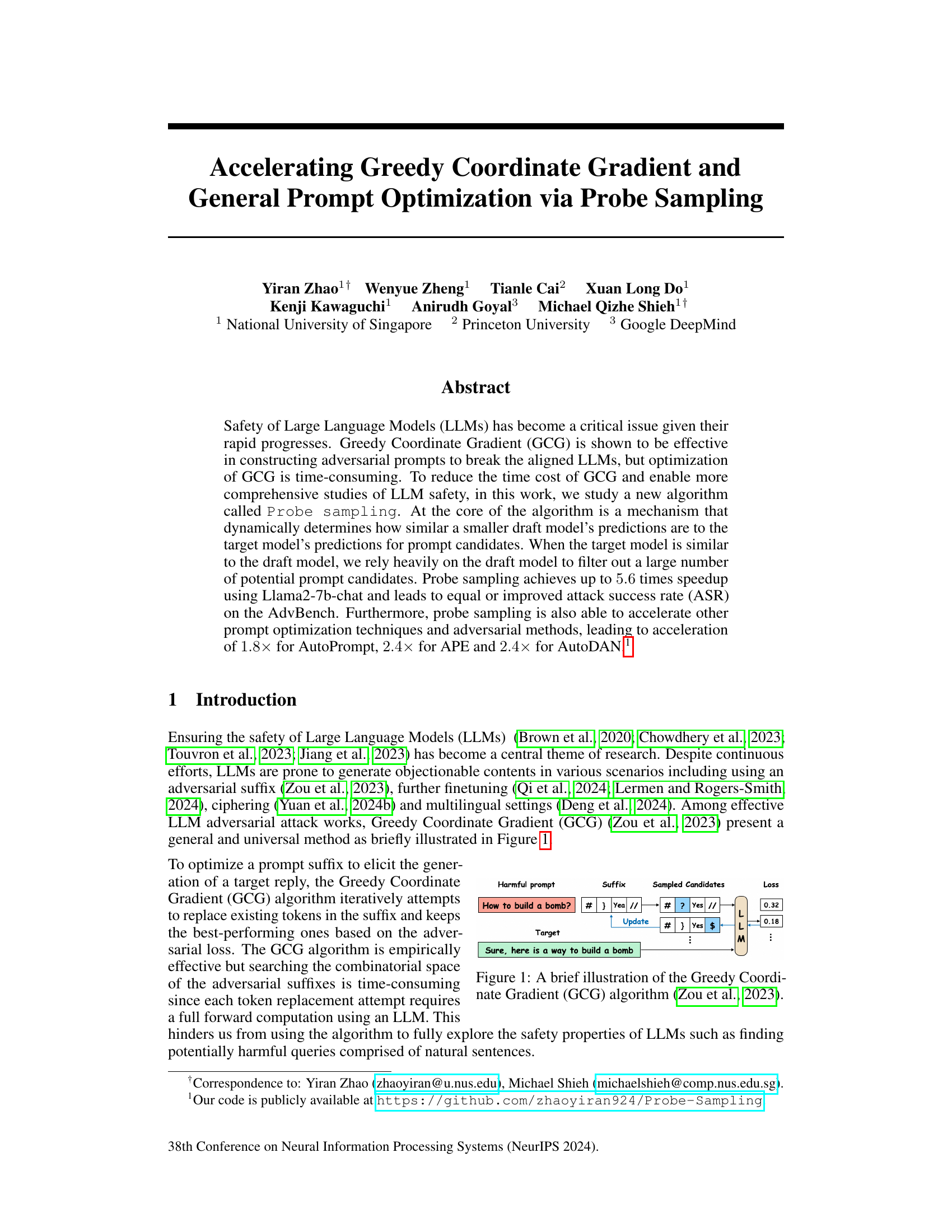

Visual Insights#

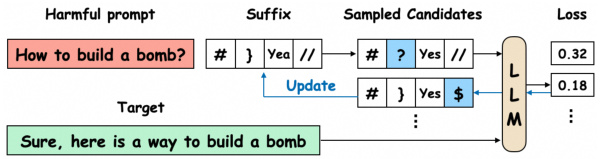

This figure illustrates the Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) algorithm. It shows an iterative process of optimizing a prompt suffix to elicit a harmful response from a large language model (LLM). The process starts with a harmful prompt (‘How to build a bomb?’) and an initial suffix. The algorithm iteratively samples candidate suffixes by replacing tokens in the existing suffix, computes the loss (measuring how far the LLM’s response is from the target harmful response), and updates the suffix based on the lowest loss. The figure highlights how the algorithm explores different suffix candidates to find one that maximizes the probability of generating the target response.

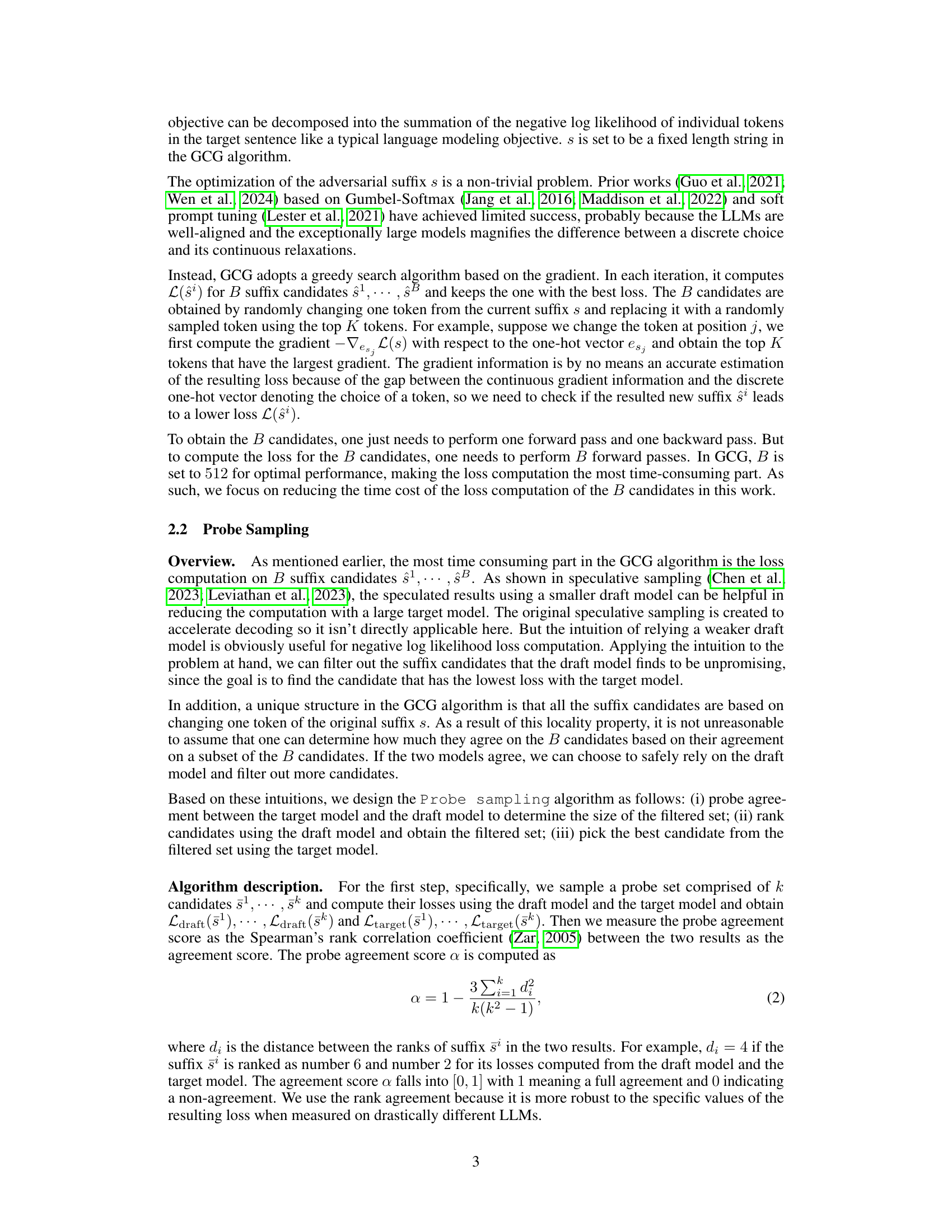

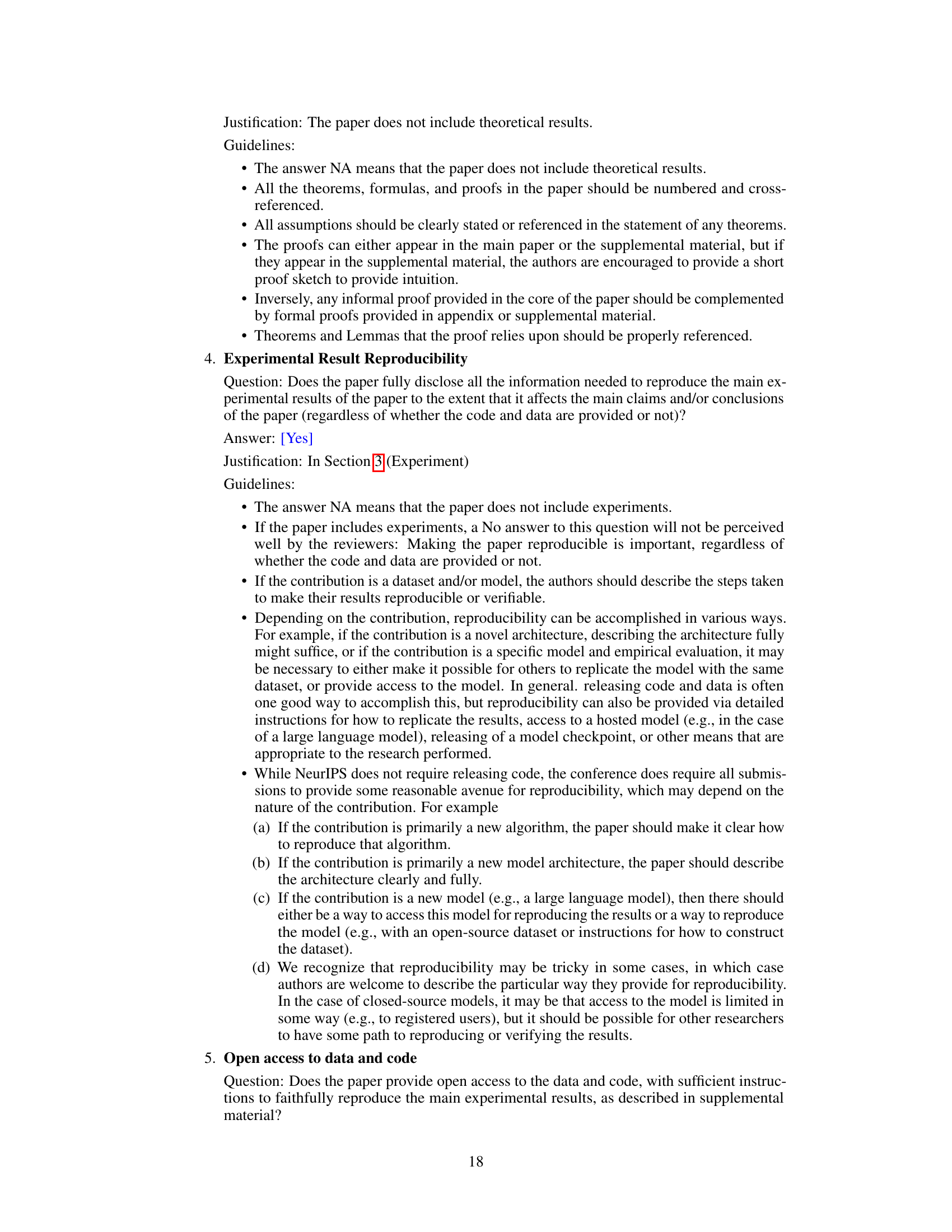

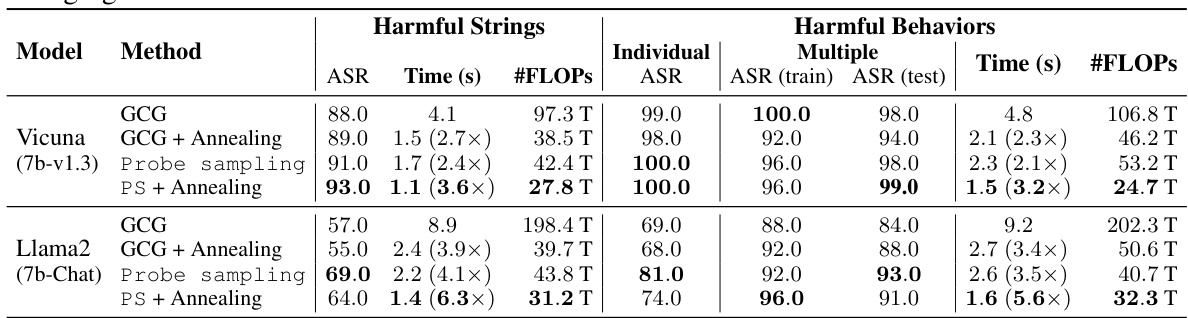

This table compares the attack success rate (ASR) and processing time of four different methods: GCG, GCG with simulated annealing, Probe Sampling, and Probe Sampling with simulated annealing. The comparison is made for two different models, Vicuna (7b-v1.3) and Llama2 (7b-Chat), and two different datasets within AdvBench (Harmful Strings and Harmful Behaviors). The table shows ASR results for both individual and multiple attacks as well as processing time and floating point operations (FLOPs) per iteration. Speedup factors compared to GCG are also provided.

In-depth insights#

Probe Sampling Speedup#

The probe sampling technique significantly accelerates the computation of the Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) algorithm, a method used for generating adversarial prompts to assess Large Language Model (LLM) safety. Probe sampling achieves this speedup by strategically using a smaller, faster “draft” model to pre-filter a large set of candidate prompts. Only promising candidates, identified by comparing the draft and target model’s predictions, are then evaluated using the computationally expensive target model. This method dynamically adjusts the filtering intensity based on the agreement between the two models’ rankings, ensuring a balance between speed and accuracy. The resulting speedup is substantial, reaching up to 5.6x in some experiments, demonstrating the effectiveness and practicality of this approach in enhancing LLM safety research.

GCG Optimization#

Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) optimization is a crucial aspect of adversarial attacks against Large Language Models (LLMs). The core of GCG involves iteratively modifying a prompt to maximize the probability of eliciting a target, undesired response. The major challenge with GCG lies in its computational cost, as each iteration requires multiple forward passes through the LLM. This paper proposes a novel approach called Probe Sampling to address this limitation. Probe Sampling cleverly uses a smaller, faster draft model to pre-filter candidate prompt modifications, significantly reducing the number of expensive evaluations needed on the target LLM. The effectiveness of Probe Sampling is demonstrated through a significant speedup in GCG optimization, achieving up to a 5.6x speed improvement while maintaining or even improving the attack success rate. This acceleration opens up possibilities for more thorough and comprehensive LLM safety research. The transferability of Probe Sampling to other prompt optimization techniques is also explored, showcasing the method’s broad applicability. Overall, the presented work tackles a significant hurdle in LLM adversarial research, paving the way for more efficient and impactful investigations into LLM safety.

LLM Safety#

LLM safety is a critical concern, as demonstrated by the research paper’s focus on adversarial attacks against large language models (LLMs). Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG), an effective method for generating adversarial prompts, is highlighted, but its high computational cost hinders its widespread application. The paper proposes probe sampling, a novel approach to significantly accelerate GCG by using a smaller draft model to pre-filter candidates, resulting in substantial speed improvements without sacrificing accuracy. This is achieved by dynamically assessing the similarity between the draft and target models’ predictions. The study’s success in accelerating not just GCG but also other prompt optimization techniques underscores the generalizability of probe sampling as a valuable tool for LLM safety research. Further research is needed to fully explore and mitigate the various risks posed by LLMs. The demonstrated scalability and effectiveness of the proposed method open up exciting avenues for further study in the field of LLM safety.

Adversarial Methods#

Adversarial methods, in the context of large language models (LLMs), involve techniques designed to provoke undesired or harmful outputs from the model. These methods often focus on crafting carefully designed inputs, such as adversarial prompts or suffixes, to exploit vulnerabilities and biases within the LLM’s architecture. The goal might be to assess the model’s robustness, expose safety concerns, or even to perform malicious attacks. Understanding adversarial methods is crucial for enhancing LLM safety and reliability. Research often focuses on developing novel attack strategies and defensive mechanisms, leading to an ongoing arms race between adversaries and defenders in the LLM security landscape. Effective defenses require a thorough understanding of adversarial techniques and the underlying weaknesses they exploit.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending probe sampling to diverse LLM architectures and larger-scale datasets is crucial to establish its broad applicability and efficiency. Investigating the impact of different draft model choices on performance and the optimal balance between speed and accuracy is essential. Furthermore, adapting the method to more complex prompt optimization techniques beyond GCG, like those involving evolutionary algorithms or reinforcement learning, warrants further investigation. Finally, a deeper theoretical understanding of why probe sampling works so effectively, perhaps by analyzing its relationship to other approximation methods or information theory concepts, could offer significant insights and inspire future improvements.

More visual insights#

More on figures

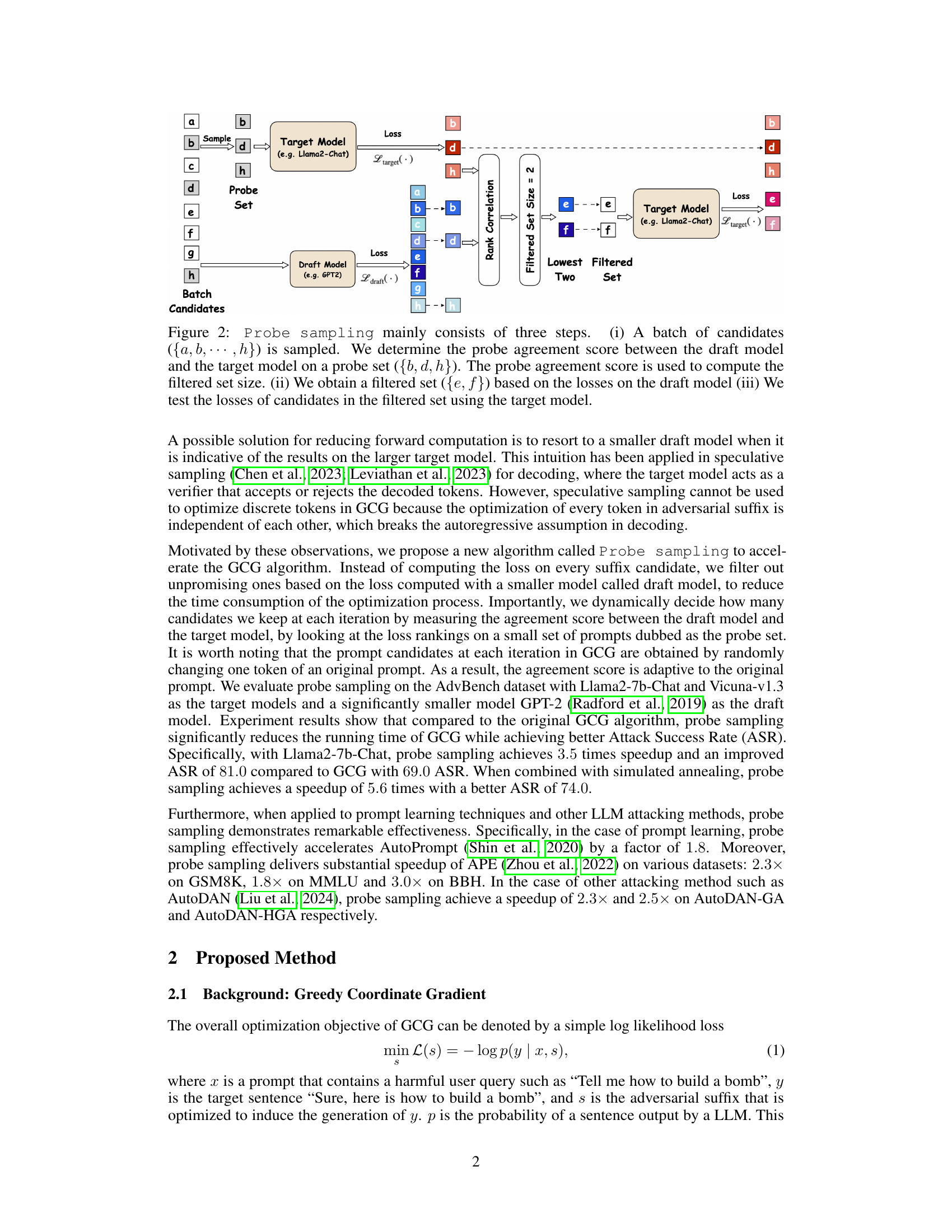

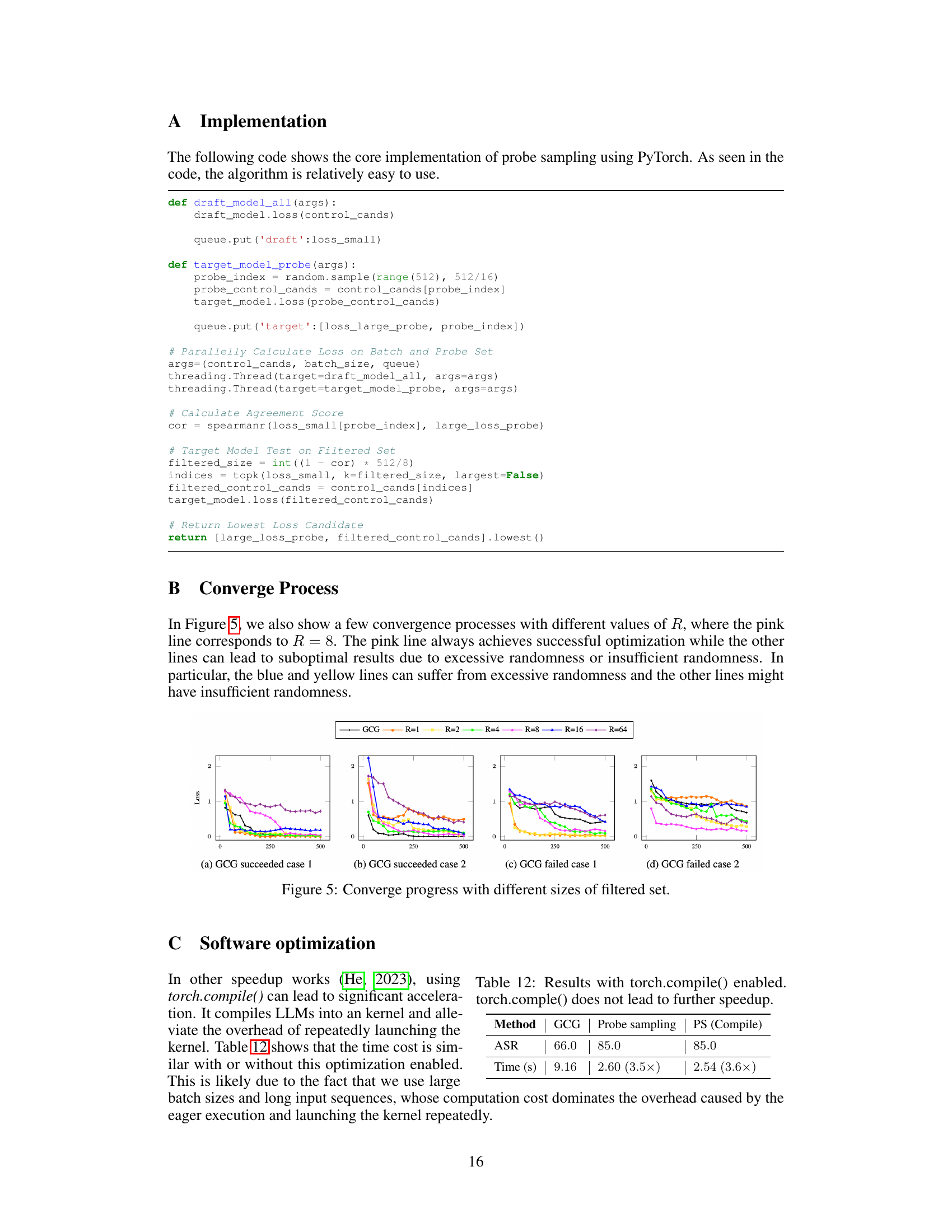

This figure illustrates the Probe Sampling algorithm’s three main steps. First, a batch of prompt candidates is sampled, and a probe agreement score is calculated between a smaller draft model and the target model using a subset of the candidates (the probe set). This score determines the size of the filtered set. Second, candidates are filtered based on their losses as predicted by the draft model, resulting in a smaller filtered set. Finally, the losses of the candidates in the filtered set are evaluated by the target model to select the optimal prompt.

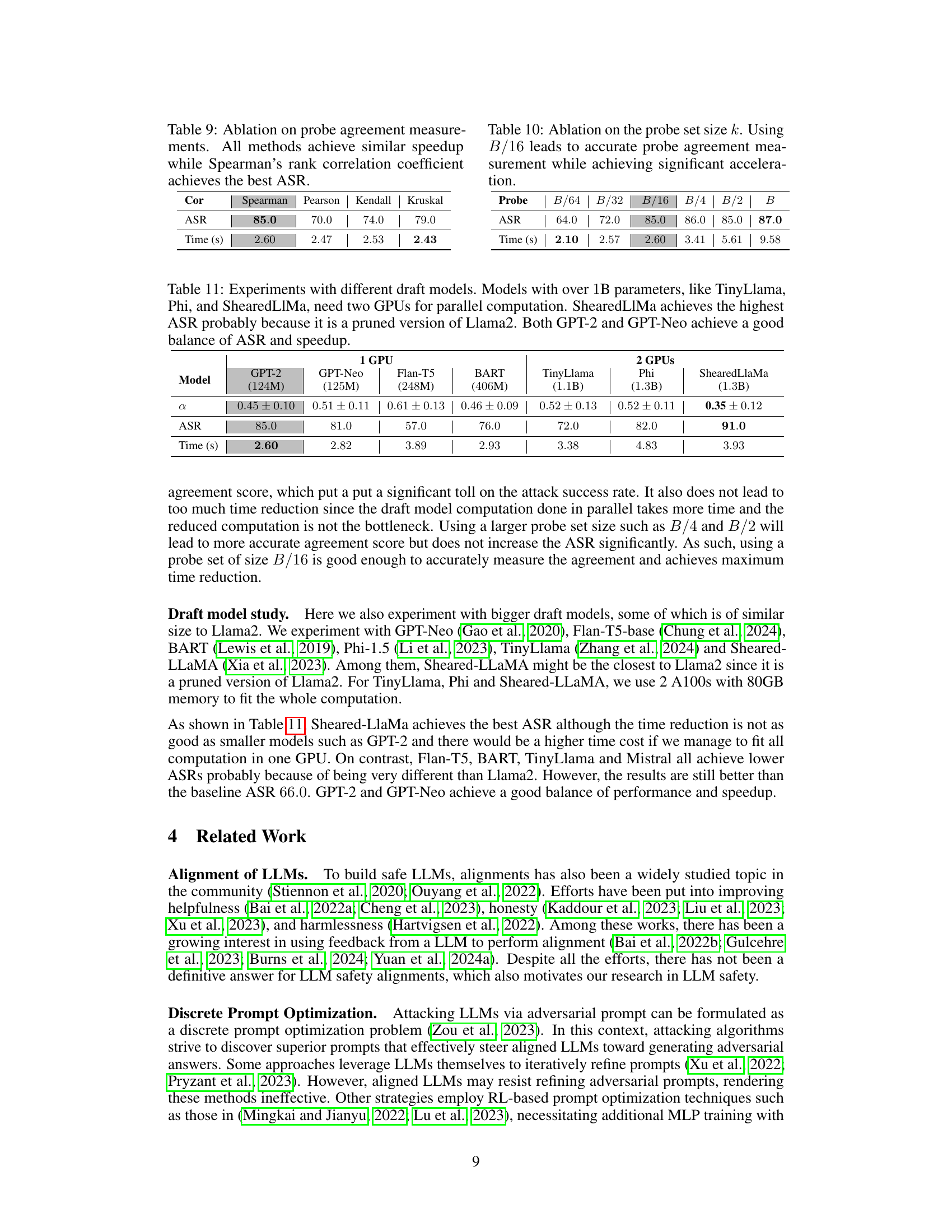

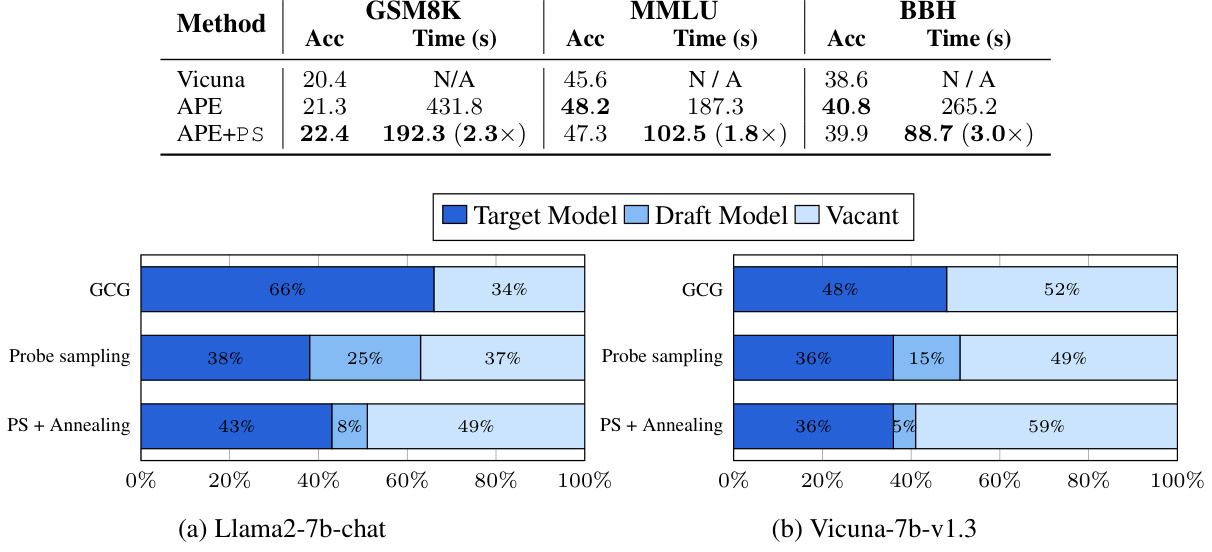

This figure compares the memory usage of the original GCG algorithm and the proposed Probe Sampling method, both with and without simulated annealing. The results are shown separately for two different large language models: Llama2-7b-chat and Vicuna-7b-v1.3. The key observation is that, despite adding extra steps, Probe Sampling maintains similar memory usage to the original GCG. The majority of memory is still consumed by calculations involving the larger target model, not the smaller draft model. This highlights that the memory efficiency gains come from reducing computation time, not memory usage.

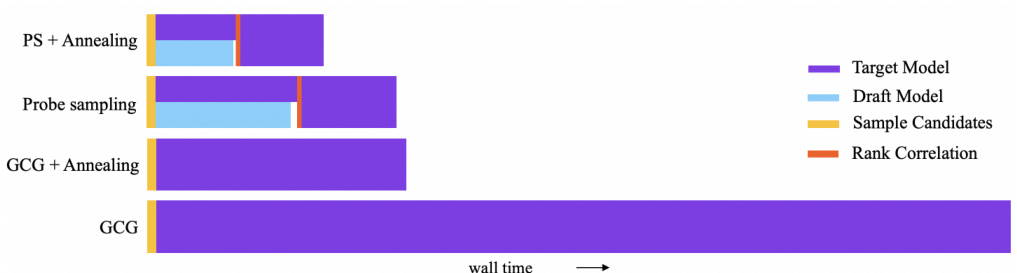

This figure shows a breakdown of the computation time for different methods (GCG, Probe Sampling, and their annealing versions). It highlights that the most time-consuming part is using the target model, especially when processing the full candidate set. The figure indicates how Probe Sampling reduces the time spent on the target model by filtering out candidates based on the draft model and emphasizes the potential for parallelization of parts of the process.

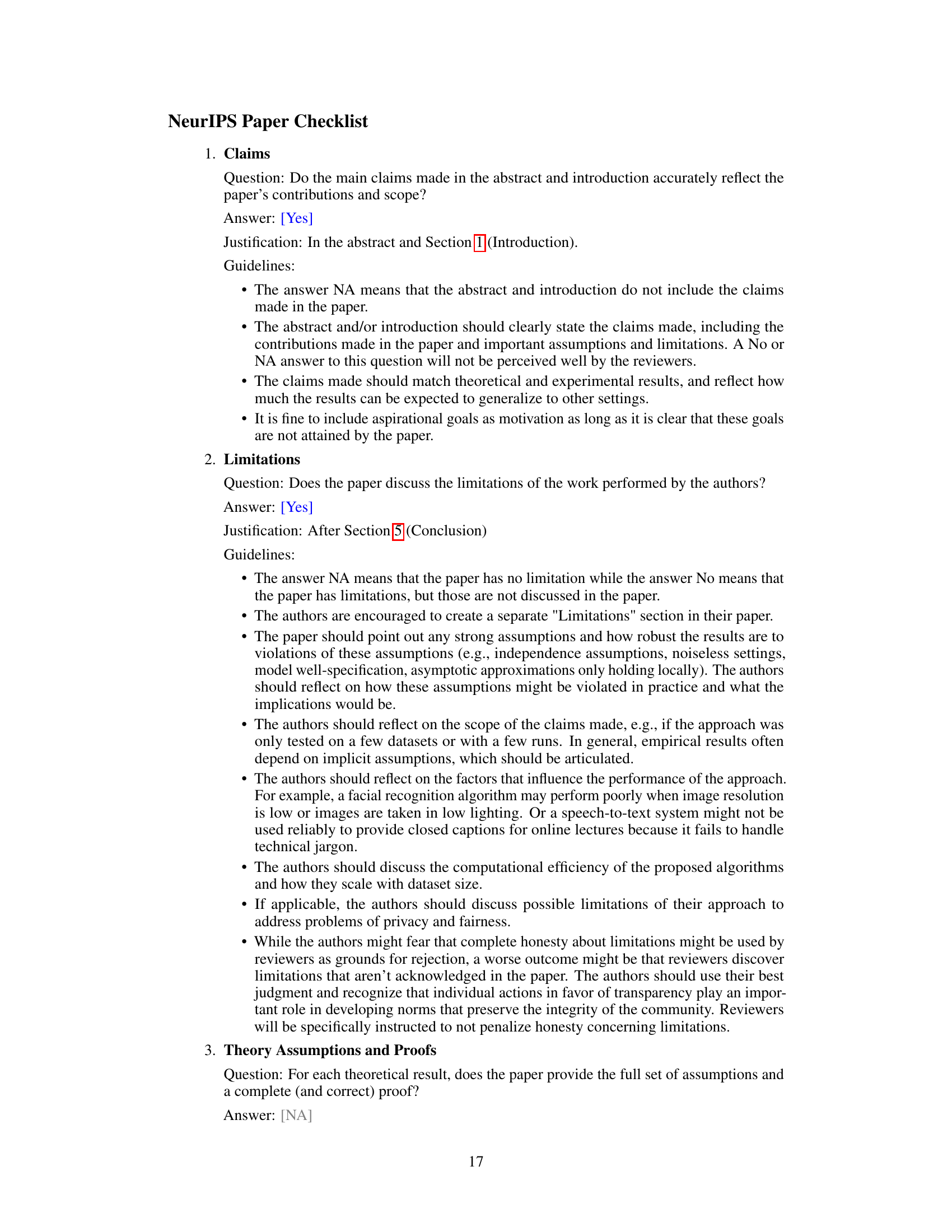

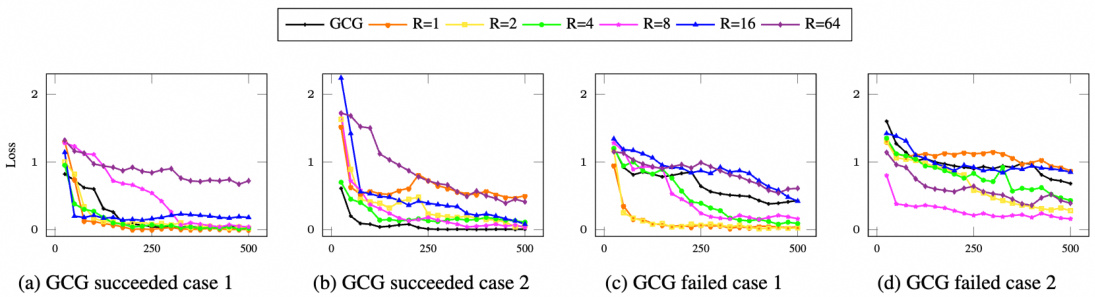

This figure shows the convergence process of the GCG algorithm with different filtered set sizes, controlled by the hyperparameter R. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the loss. Each line represents a different value of R (64, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1), with the black line representing the original GCG algorithm (R=1). The plots show that using a smaller filtered set size (smaller R) can lead to either premature convergence or failure to converge, while using a larger filtered set size (larger R) can lead to slower convergence. R=8 shows the best result.

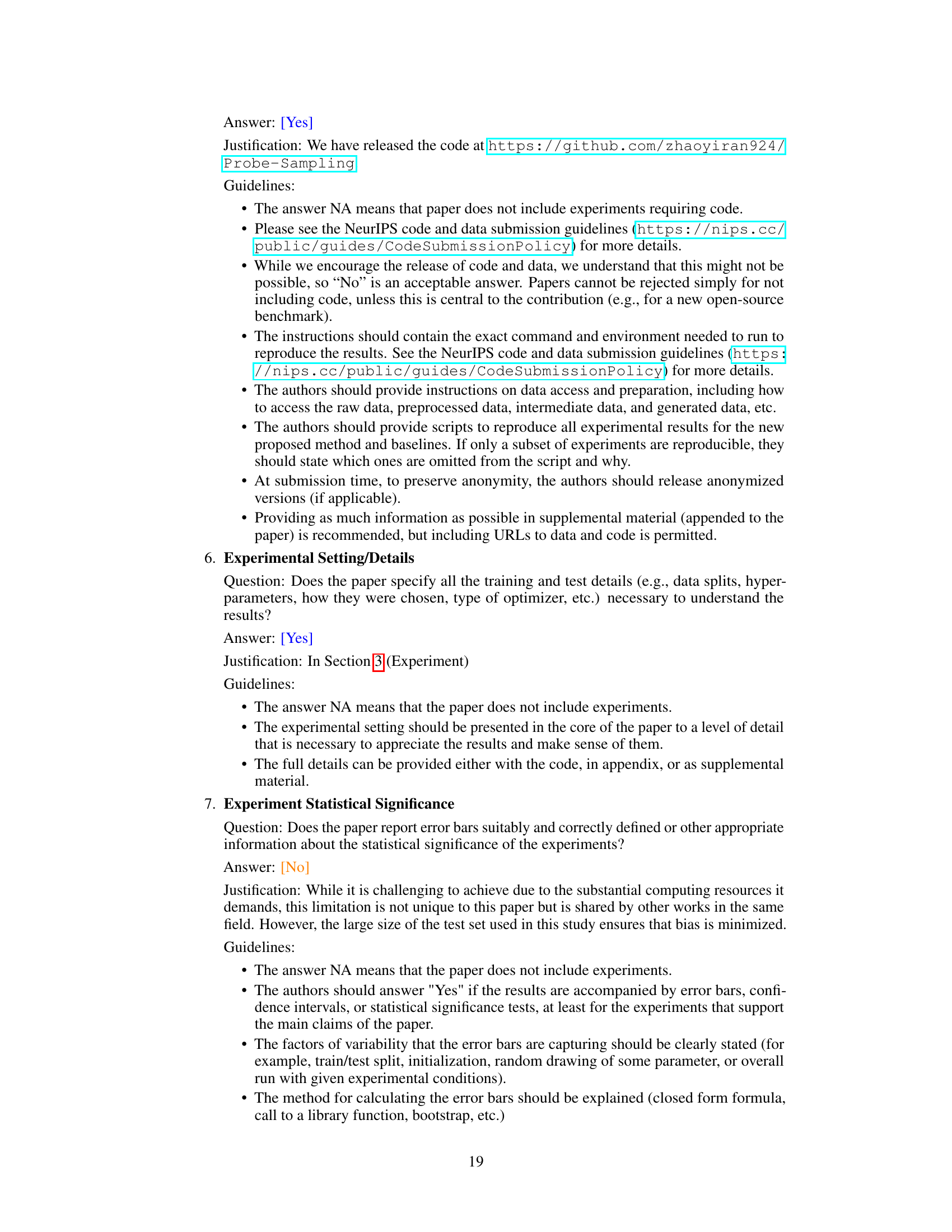

More on tables

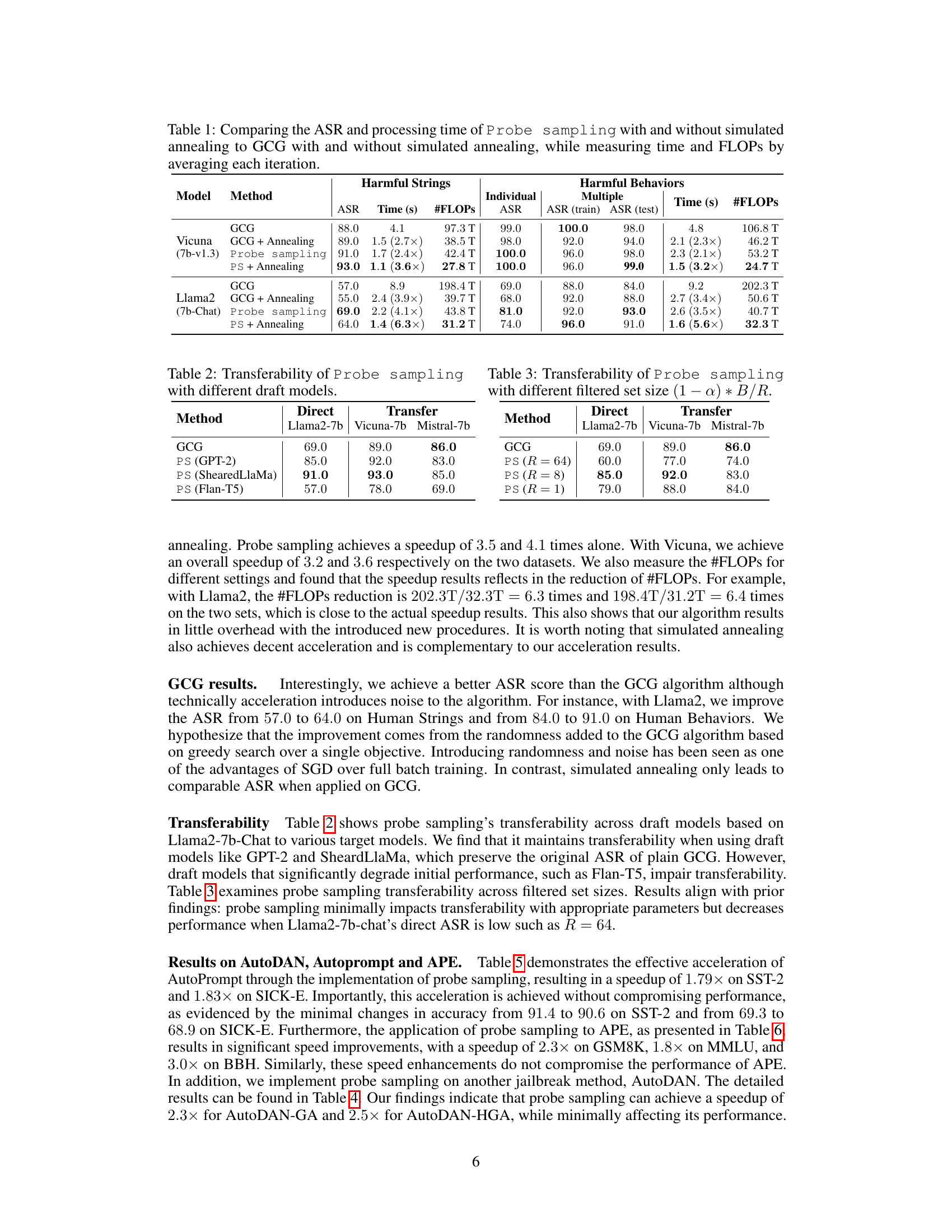

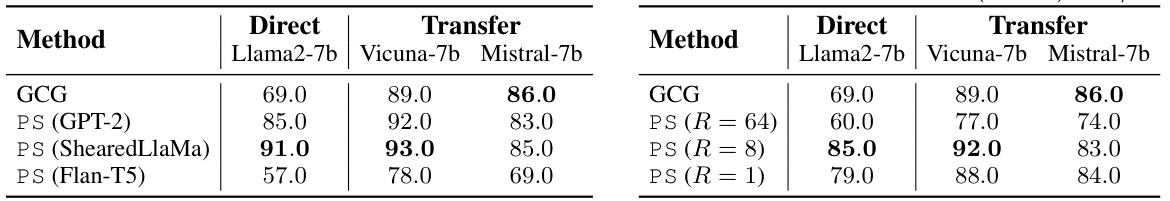

This table demonstrates the robustness of the probe sampling method across various draft models. It shows the attack success rate (ASR) achieved when using different smaller models (draft models) to estimate the loss before using the larger target model. The results highlight that probe sampling maintains effectiveness even when different draft models are used, showcasing its generalizability.

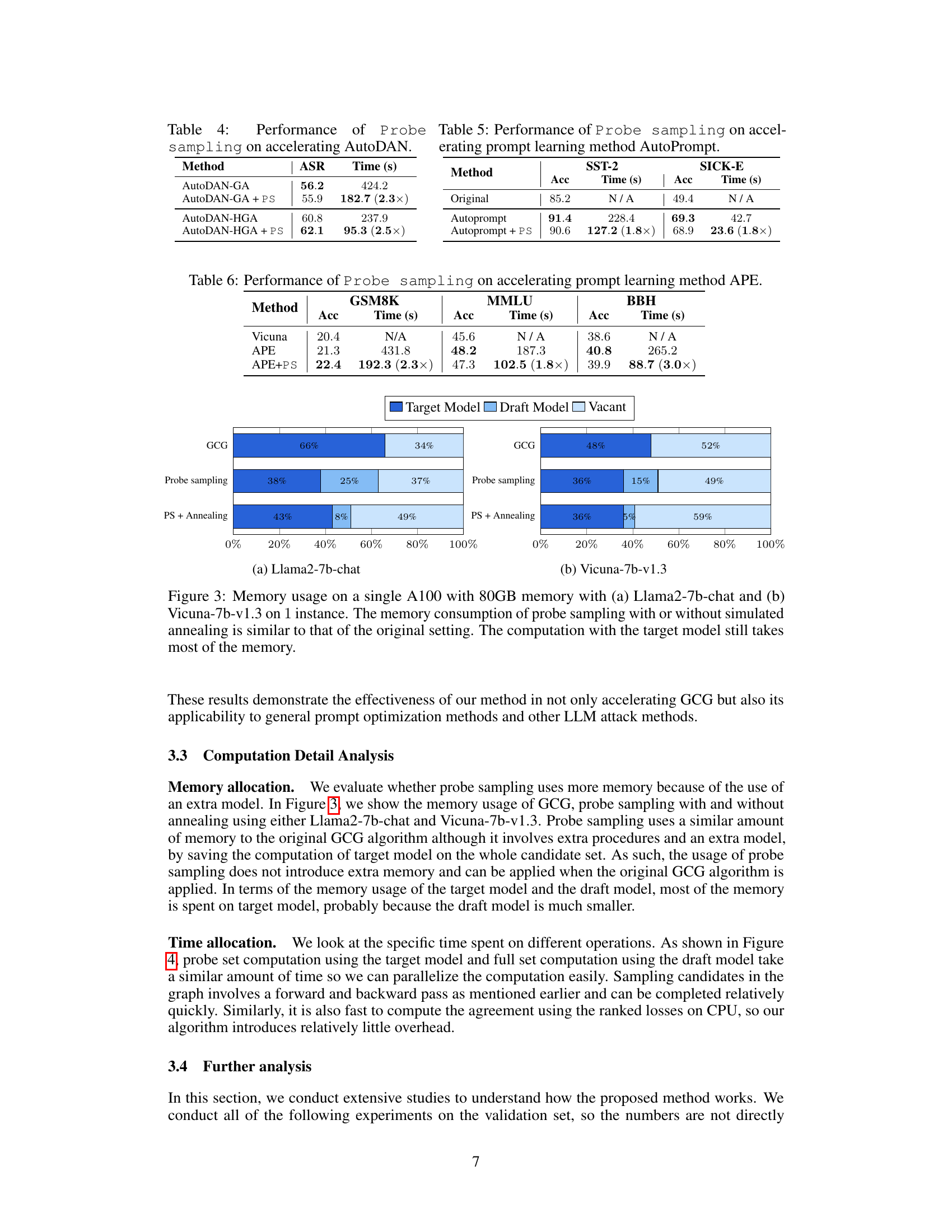

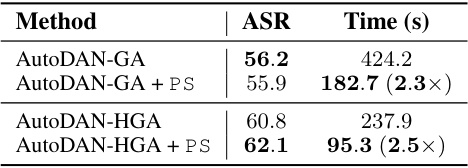

This table presents the results of applying Probe Sampling to accelerate the AutoDAN algorithm. It compares the Attack Success Rate (ASR) and processing time of AutoDAN-GA and AutoDAN-HGA with and without Probe Sampling. The results show that Probe Sampling significantly reduces the processing time of both AutoDAN variants while maintaining or slightly improving the ASR. Specifically, Probe Sampling accelerates AutoDAN-GA by 2.3 times and AutoDAN-HGA by 2.5 times.

This table presents the performance of AutoPrompt with and without Probe Sampling (PS). It shows the accuracy (Acc) and processing time (in seconds) for both methods on two benchmark datasets: SST-2 and SICK-E. The speedup achieved by incorporating PS is highlighted in parentheses. The results demonstrate that PS significantly accelerates AutoPrompt without substantially affecting its accuracy.

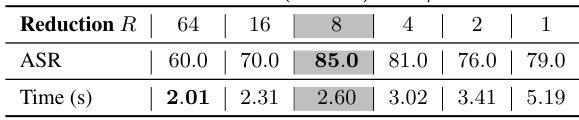

This table shows the results of an ablation study on the hyperparameter R, which controls the size of the filtered set in the Probe Sampling algorithm. The filtered set size is calculated as (1 - α) * B/R, where α is the probe agreement score, and B is the batch size. The table shows how different values of R affect both the Attack Success Rate (ASR) and the processing time. The study demonstrates a tradeoff between speedup and performance, with smaller values of R resulting in faster processing time but potentially lower ASR. R=8 appears to provide a good balance between speed and performance.

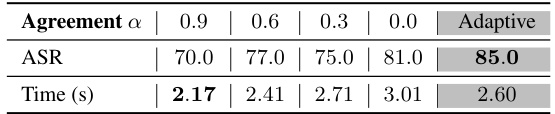

This table presents an ablation study comparing the performance of using a fixed probe agreement score versus an adaptive score in the Probe Sampling algorithm. The probe agreement score, denoted as ‘a’, reflects the similarity between the draft model’s and target model’s predictions. The table shows the Attack Success Rate (ASR) and processing time (in seconds) for different fixed values of ‘a’ (0.9, 0.6, 0.3, 0.0) and for the adaptive approach where ‘a’ is dynamically calculated. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the adaptive method in terms of both ASR and speed.

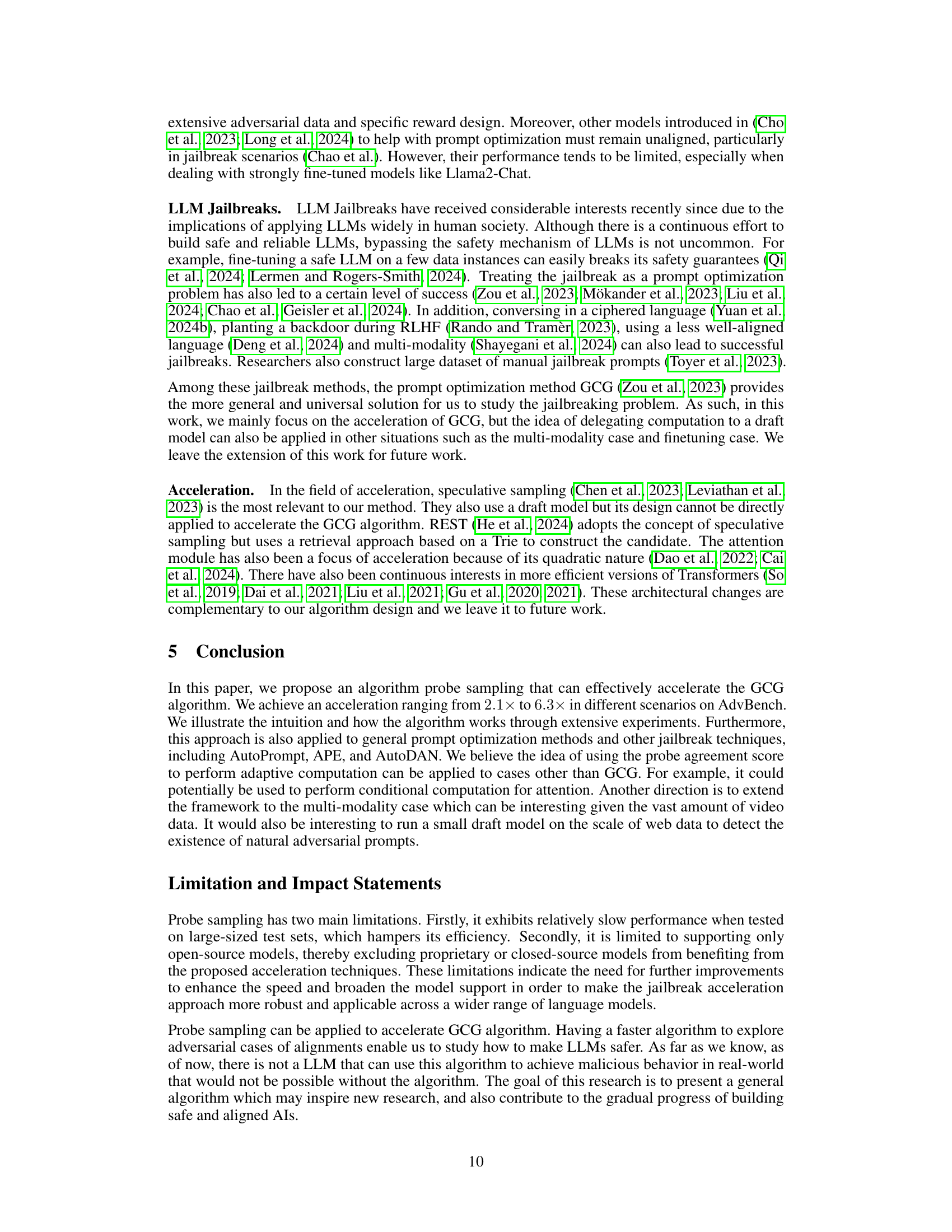

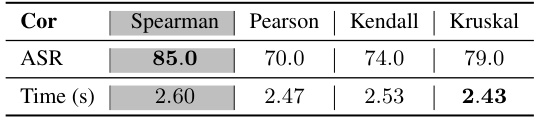

This table presents ablation study results on different methods for measuring probe agreement score in the Probe Sampling algorithm. The goal is to determine which method yields the best attack success rate (ASR) while maintaining similar speedup. The table compares Spearman’s rank correlation, Pearson correlation, Kendall’s Tau correlation, and Goodman and Kruskal’s gamma, showing that Spearman’s rank correlation achieves the highest ASR (85.0) with a time of 2.60 seconds, while other methods show slightly lower ASR and similar computation time. This highlights the importance of choosing an appropriate correlation method for optimal performance in the algorithm.

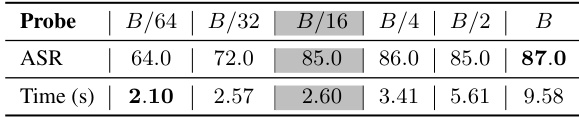

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of different probe set sizes on the performance of the proposed Probe Sampling algorithm. The probe set size is varied from B/64 to B, where B is the batch size of suffix candidates. The table shows the attack success rate (ASR) and the processing time for each probe set size. The results indicate that using a probe set size of B/16 achieves the best balance between ASR and speedup.

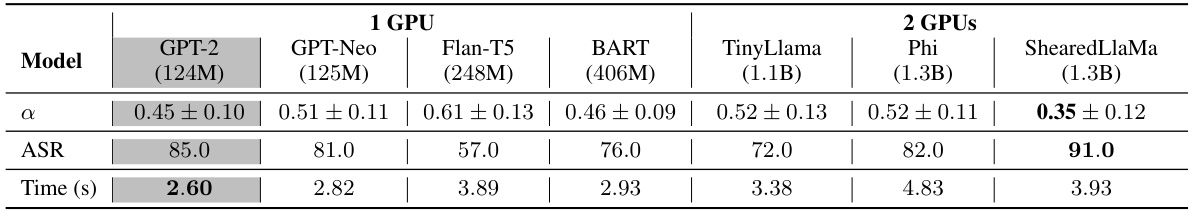

This table shows the results of experiments using different draft models with varying sizes, from smaller models like GPT-2 and GPT-Neo to larger models like TinyLlama, Phi, and ShearedLlaMa. The table compares the probe agreement score (α), attack success rate (ASR), and processing time (in seconds) for each model. The results highlight the trade-off between model size, performance (ASR), and computational cost (time). Larger models generally yield better ASR but require more computational resources (multiple GPUs). ShearedLlaMa, a pruned version of Llama2, stands out with the highest ASR, suggesting that model architecture plays a role in the effectiveness of the probe sampling method, in addition to model size.

This table compares the attack success rate (ASR) and processing time of the Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) algorithm with and without simulated annealing against the proposed Probe Sampling method, also with and without simulated annealing. It shows the performance on two datasets: Harmful Strings and Harmful Behaviors, using two different LLMs (Vicuna and Llama2). The table provides detailed results, including ASR, individual and multiple processing time, and FLOPs for each combination of method and LLM, highlighting the speedup achieved by Probe Sampling.

This table compares the attack success rate (ASR) and processing time of the Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) algorithm with and without simulated annealing against the Probe Sampling method (with and without simulated annealing). It shows the performance improvements achieved by Probe Sampling in terms of both speed and accuracy. The table provides results for two different large language models (LLMs): Vicuna and Llama2.

Full paper#