↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

This paper addresses the challenge of efficiently computing distances between Markov chains, a critical problem across diverse fields such as reinforcement learning and computer science. Existing methods relied on dynamic programming, which proved computationally expensive. The authors highlight the limitations of previous approaches focusing on couplings between the entire joint distribution induced by the chains.

The researchers propose a novel framework using ‘discounted occupancy couplings’, a flattened representation of joint distributions. This allows formulating the distance computation as a linear program, enabling the application of efficient techniques from optimal transport theory. The new algorithm, called Sinkhorn Value Iteration, leverages entropy regularization and matches the widely used bisimulation metrics, offering a significantly improved computational efficiency and theoretical grounding for calculating these important distances.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning, computer science, and related fields. It bridges the gap between two seemingly disparate research areas, optimal transport and bisimulation metrics, demonstrating their equivalence. This unification opens new avenues for efficient computation of bisimulation metrics, significantly impacting applications like reinforcement learning and state aggregation. Furthermore, the introduction of entropy regularization and the novel Sinkhorn Value Iteration algorithm contribute to advancing computational optimal transport. The paper’s findings are highly relevant to current trends in representation learning and graph analysis.

Visual Insights#

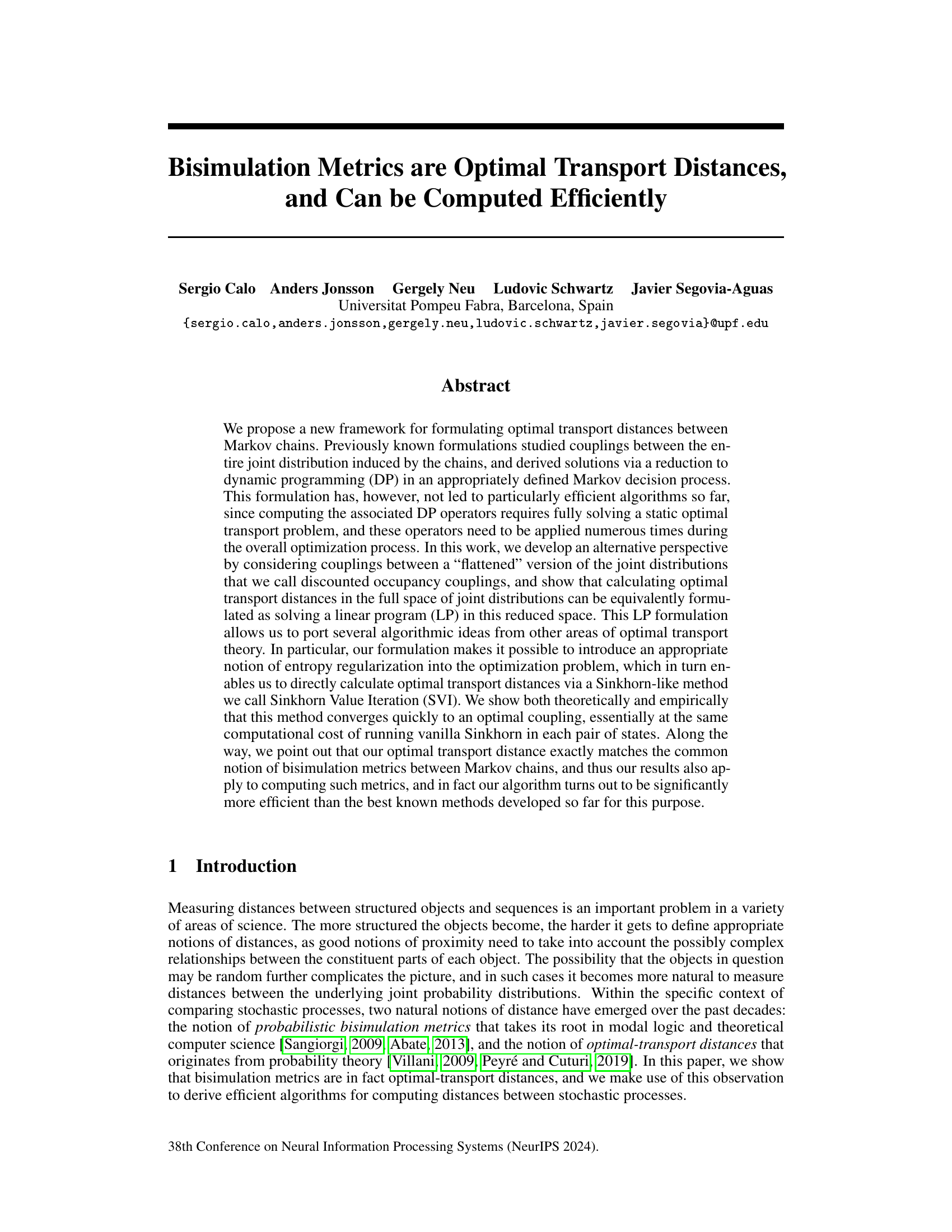

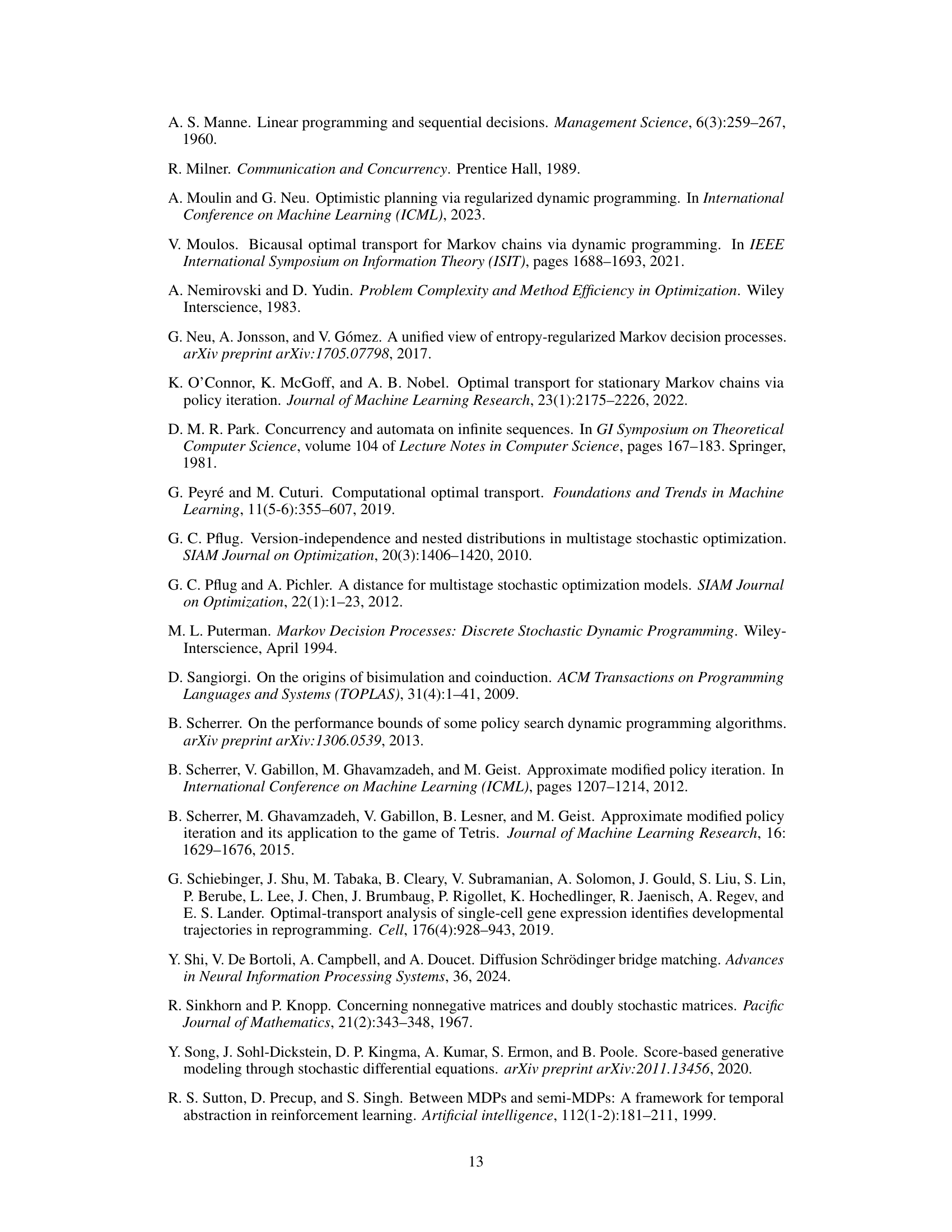

This figure shows the estimated transport cost as a function of the number of iterations (k) for various choices of the parameter ’m’ and a fixed value of η=1. The plots (a) and (b) represent the results from two different algorithms, SVI (Sinkhorn Value Iteration) and SPI (Sinkhorn Policy Iteration), respectively. The different lines in each plot represent different values of ’m’, illustrating the effect of this parameter on the convergence rate and final accuracy of the algorithms.

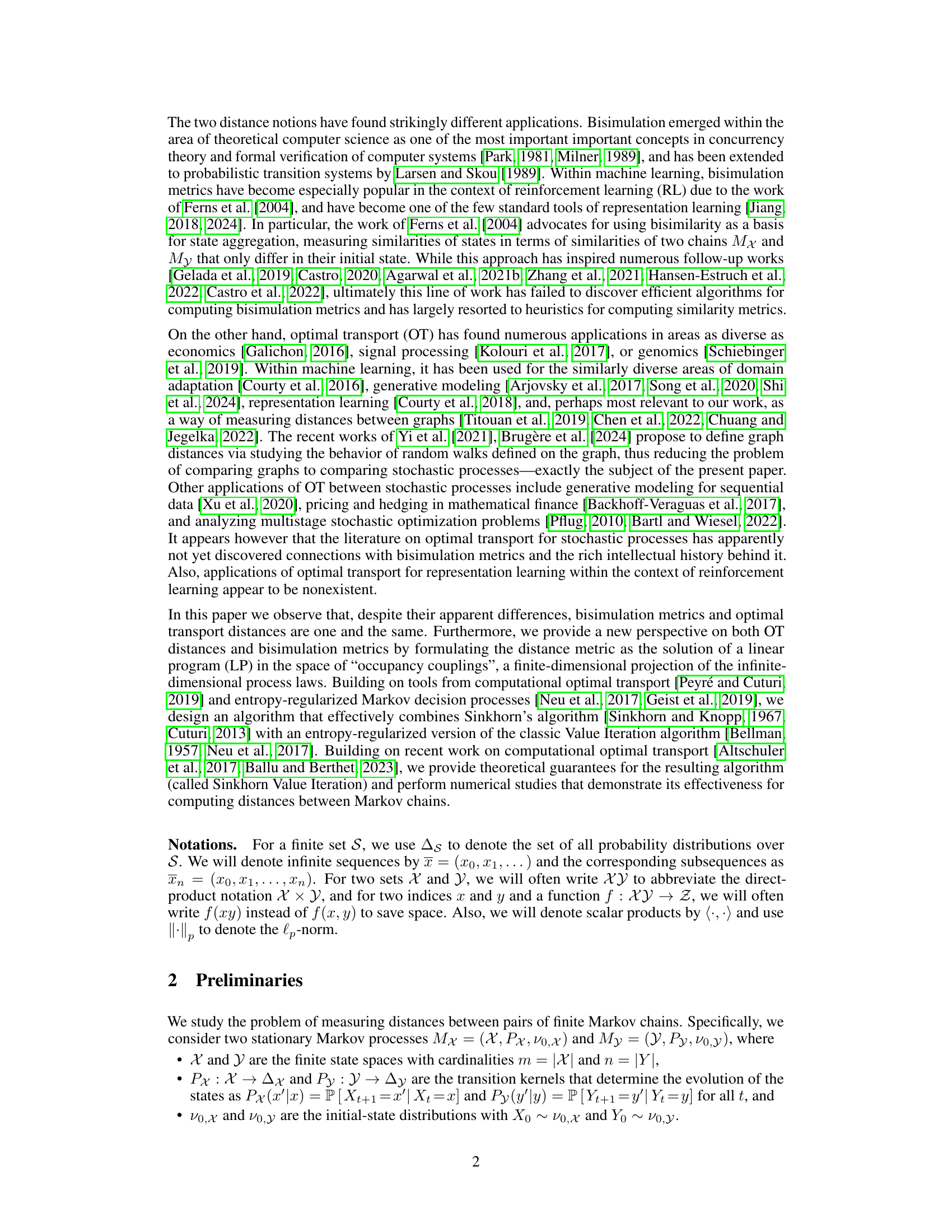

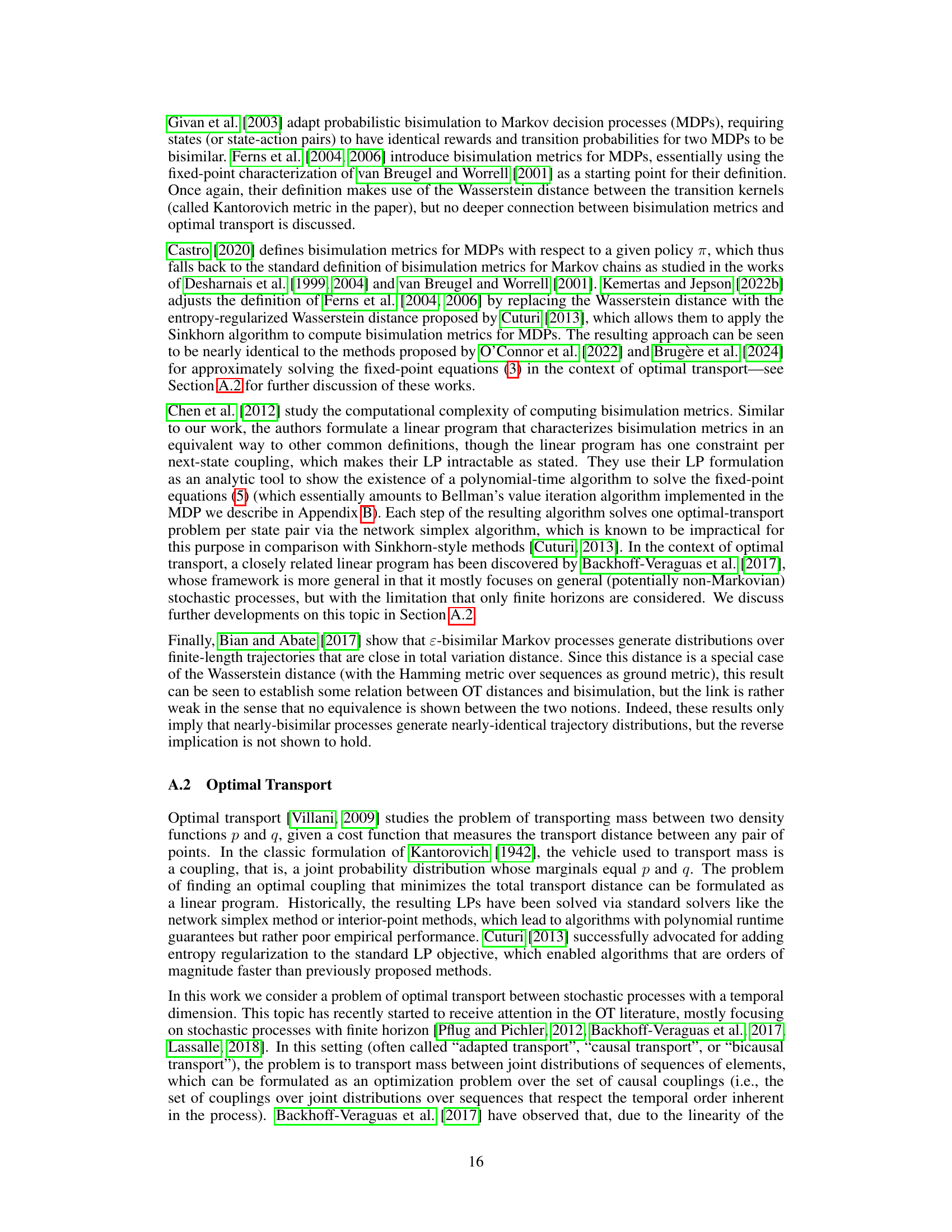

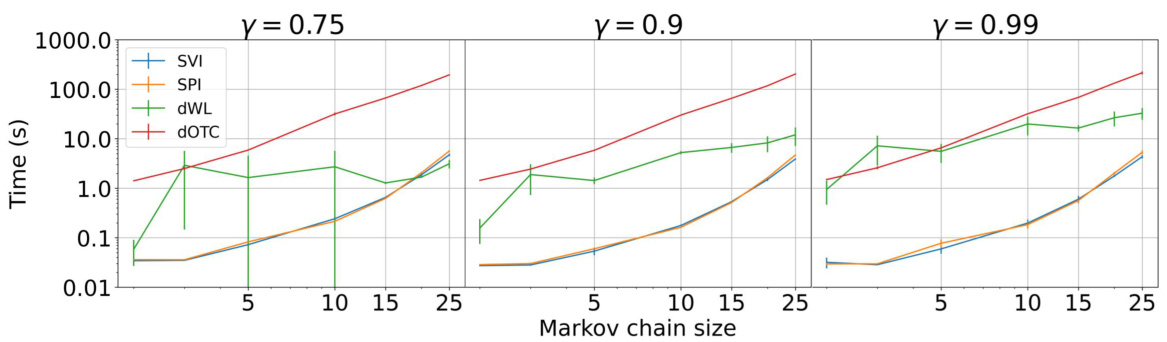

The figure compares the computational time of SVI, SPI, dWL, and EntropicOTC for various Markov chain sizes and discount factors. The results show the average computation time across five randomly generated instances for each size and discount factor, with standard deviations displayed. The log-log scale facilitates visualization of performance differences across various parameter settings.

In-depth insights#

Optimal Transport View#

An Optimal Transport View in a research paper would likely explore the mathematical framework of optimal transport (OT) to analyze and model the relationships between different entities within a system. This approach would offer a unique perspective, potentially revealing hidden structures or connections not readily apparent using other methods. The core concept of OT, finding the most efficient way to transport probability mass from one distribution to another, can be adapted to various domains within the paper. A key advantage of this approach is its ability to quantify similarity or dissimilarity between different objects or distributions based on a chosen cost function. This allows for a principled and mathematically grounded comparison which is crucial for applications such as comparing Markov chains or measuring distances between structured objects or sequences, aspects often discussed in the context of representation learning. The choice of cost function itself can significantly impact the results; selecting a cost function that aligns with the specific problem context is essential for meaningful interpretations. Furthermore, an OT viewpoint may enable the development of novel algorithms for computing distances or similarities which might be more computationally efficient compared to traditional approaches. Algorithmic advancements, such as entropy regularization, might be specifically highlighted to showcase practical applicability. Ultimately, the effectiveness and value of the Optimal Transport View hinge on the careful selection of cost functions, the suitability of the OT framework to the problem at hand, and the development of algorithms that efficiently perform computations.

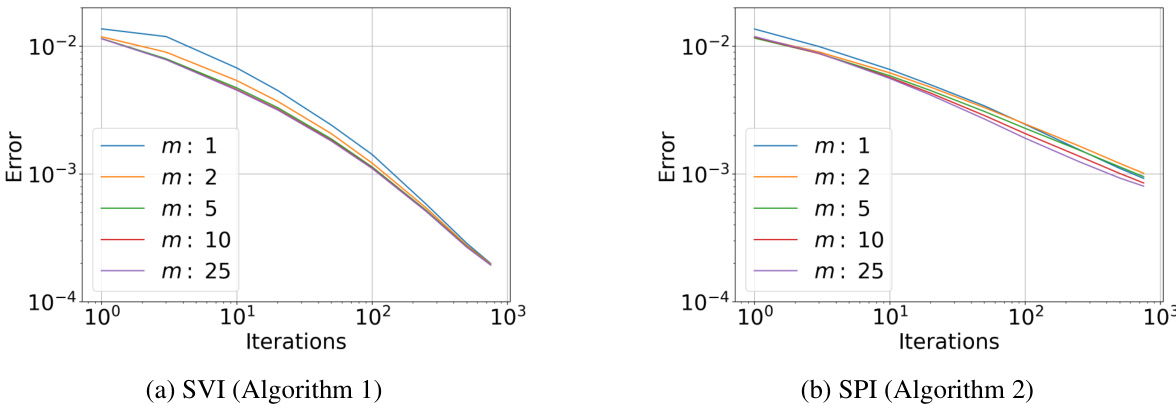

Sinkhorn Value Iteration#

The proposed Sinkhorn Value Iteration (SVI) algorithm offers a novel approach to compute optimal transport distances between Markov chains. SVI leverages entropy regularization, a technique that has proven highly effective in speeding up optimal transport computations, combined with value iteration, a classic dynamic programming method. This combination allows SVI to efficiently converge to an optimal coupling between the Markov chains, achieving a speedup compared to previous methods. The algorithm’s computational cost is comparable to that of vanilla Sinkhorn, making it computationally practical for larger problems. Theoretically, SVI matches bisimulation metrics, providing a unified framework for both optimal transport and bisimulation. The algorithm’s effectiveness is supported by theoretical guarantees on its convergence rate and empirical evidence of fast convergence.

Bisimulation Metrics#

Bisimulation metrics quantify the similarity between state transition systems, particularly Markov chains. They offer a powerful tool for comparing the behavior of stochastic processes, going beyond simple structural equivalence. Traditionally, bisimulation metrics were studied within theoretical computer science and formal verification, finding applications in areas such as model checking and concurrency theory. A key insight from the provided research is the equivalence between bisimulation metrics and optimal transport distances. This surprising connection bridges two seemingly disparate fields, opening new avenues for computational methods. Optimal transport, with its established algorithms and theoretical framework, offers significantly more efficient computational approaches than previously available for calculating bisimulation metrics, thus enabling applications in machine learning and representation learning that were previously intractable. The research highlights the computational benefits of this new perspective, specifically advocating for techniques such as Sinkhorn Value Iteration and Entropy Regularization, which substantially improve the speed and scalability of bisimulation metric computations.

Linear Program (LP)#

The concept of a Linear Program (LP) within the context of optimal transport for Markov chains offers a powerful and insightful approach to quantify distances between stochastic processes. The formulation of the problem as an LP provides a theoretically rigorous foundation, enabling the application of established linear programming techniques and algorithms for efficient computation. This contrasts with prior dynamic programming (DP) based approaches, which often suffer from computational limitations due to repeated solution of optimal transport problems at each step. The LP approach allows for direct calculation of optimal transport distances by leveraging the structure of the problem and translating it into a readily solvable format. The equivalence between this LP formulation and discounted occupancy couplings provides a novel perspective, making it easier to introduce concepts like entropy regularization, ultimately leading to more efficient algorithms and providing an interesting theoretical link to bisimulation metrics.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of this hypothetical research paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle non-stationary Markov chains would significantly broaden its applicability. Currently, the focus is on stationary processes, limiting the range of real-world scenarios the method can directly address. Investigating different types of entropy regularization and analyzing their impact on both theoretical guarantees and empirical performance would refine the algorithm’s efficiency and robustness. Developing methods to learn the transition kernels and cost functions directly from data would move beyond assuming complete knowledge of the underlying Markov process. This would make the techniques more useful in practical scenarios where data is readily available, but a precise model is not. Finally, exploring applications in reinforcement learning and representation learning is key. The current framework provides a novel way to compute distances between stochastic processes, which could lead to significant advances in agent-based simulations and similar fields.

More visual insights#

More on figures

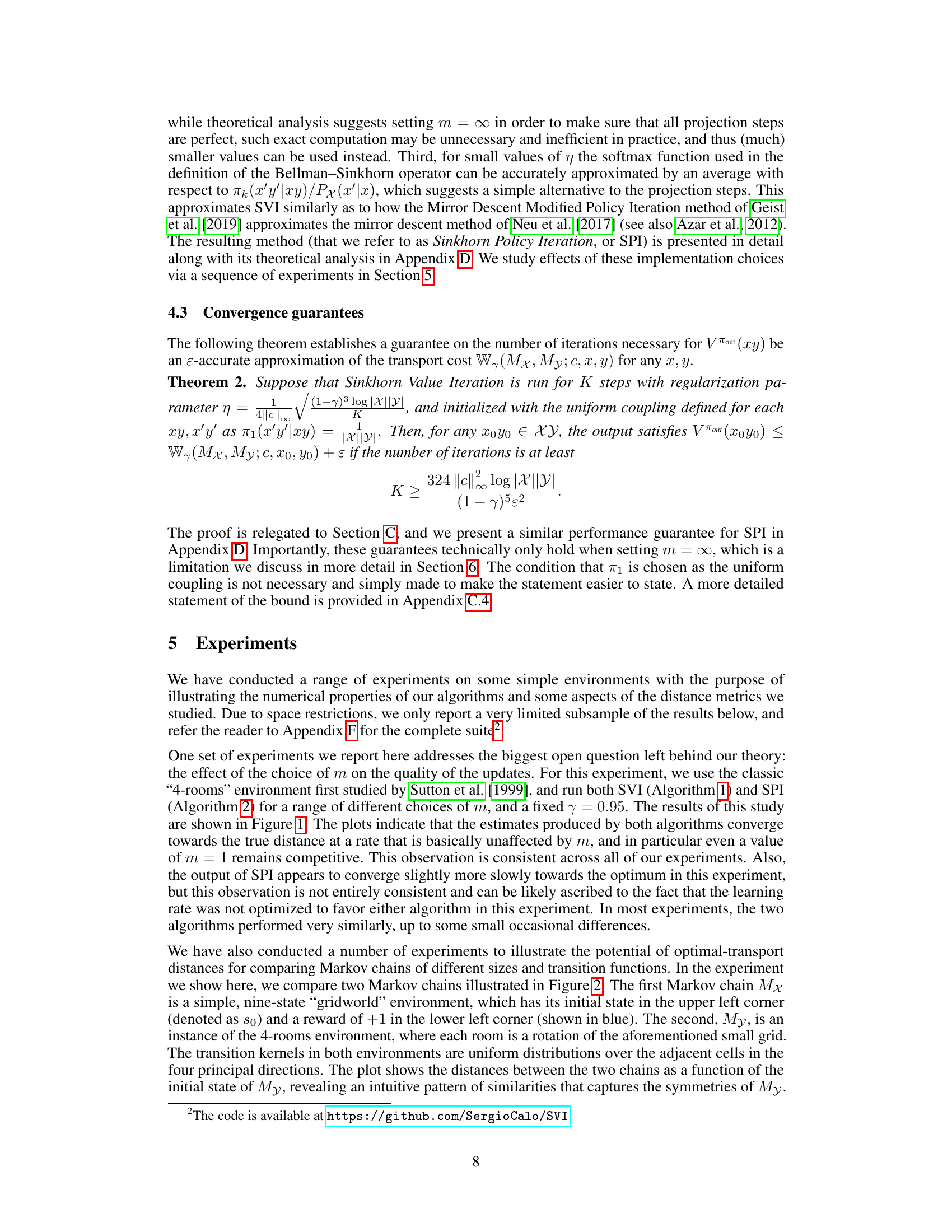

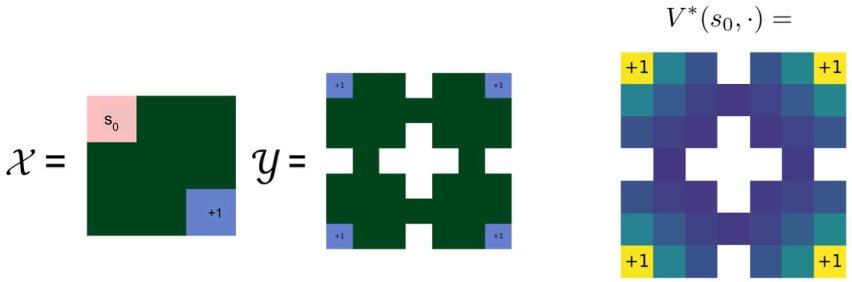

This figure visually represents the distances computed between two Markov chains, Mx and My. Chain Mx is a 3x3 grid world with a starting state (s0) in the upper left corner and a reward of +1 in the lower left corner. Chain My is a 4-room environment with the same reward placement but a different arrangement. The color intensity in the third image represents the optimal transport distance between the initial state of Mx and each state in My. Darker colors indicate larger distances, showing how the distances reflect the structural similarities and symmetries between the two Markov chains.

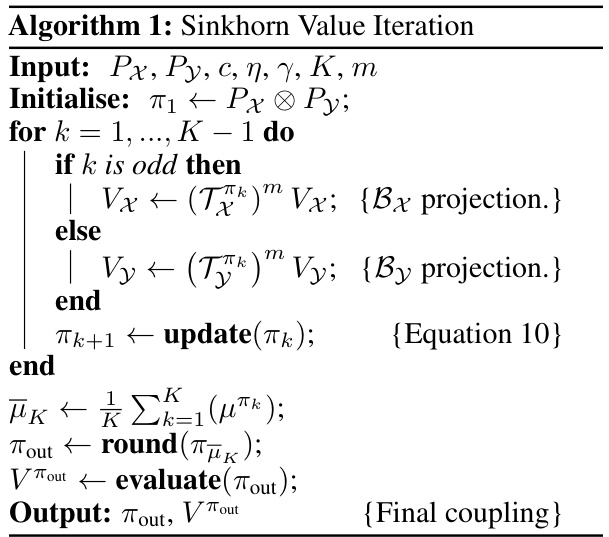

This figure shows the impact of the regularization parameter η on the performance of both SVI and SPI algorithms. The plots show the estimation error of the transport cost as a function of the number of iterations for various values of η (10/√K, 0.1, 1, and 10). The results indicate that larger η values lead to faster initial convergence, but eventually prevent the algorithm from reaching the optimal solution. Smaller η values lead to better solutions at the cost of slower initial convergence. A time-dependent learning rate schedule (ηk ~ 1/√k) is shown to achieve the best performance.

This figure compares the computation time of five different methods for calculating optimal transport distances between Markov chains, varying the discount factor (γ) and the size of the Markov chains. The methods compared include the authors’ Sinkhorn Value Iteration (SVI) and Sinkhorn Policy Iteration (SPI), alongside two existing methods (EntropicOTC and dWL). The plot shows that SVI and SPI are consistently faster than the other methods, especially when γ is large, highlighting their efficiency for computing optimal transport distances between Markov chains.

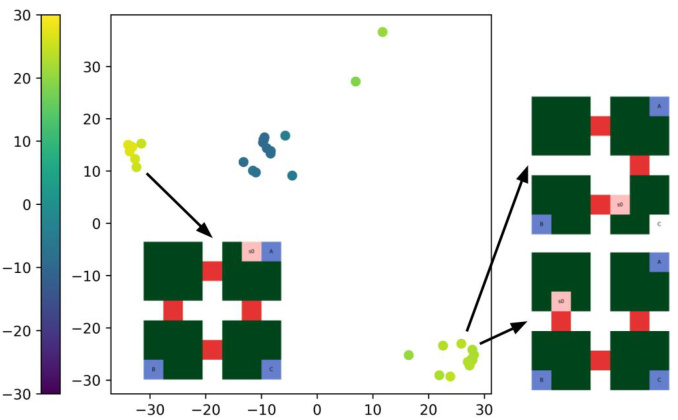

This figure shows the result of applying multidimensional scaling (MDS) to the pairwise distances between a set of 35 4-room instances (Markov chains). Each instance has a different initial state and obstacle positions but a fixed reward function. The resulting MDS plot reveals clusters of instances with similar behaviors, illustrating how the optimal transport distances capture similarities and symmetries.

More on tables

This figure compares the computation time of Sinkhorn Value Iteration (SVI), Sinkhorn Policy Iteration (SPI), EntropicOTC, and dWL for different values of the discount factor (γ) and Markov chain sizes. It shows that SVI and SPI are significantly faster than the other methods for various problem settings.

This figure compares the computation time of different algorithms for computing optimal transport distances between Markov chains for various discount factors (γ). The x-axis represents the Markov chain size, while the y-axis displays the computation time (log-scale). The plot shows that the proposed SVI and SPI methods are significantly faster than other existing methods, especially as the Markov chains grow larger.

Full paper#