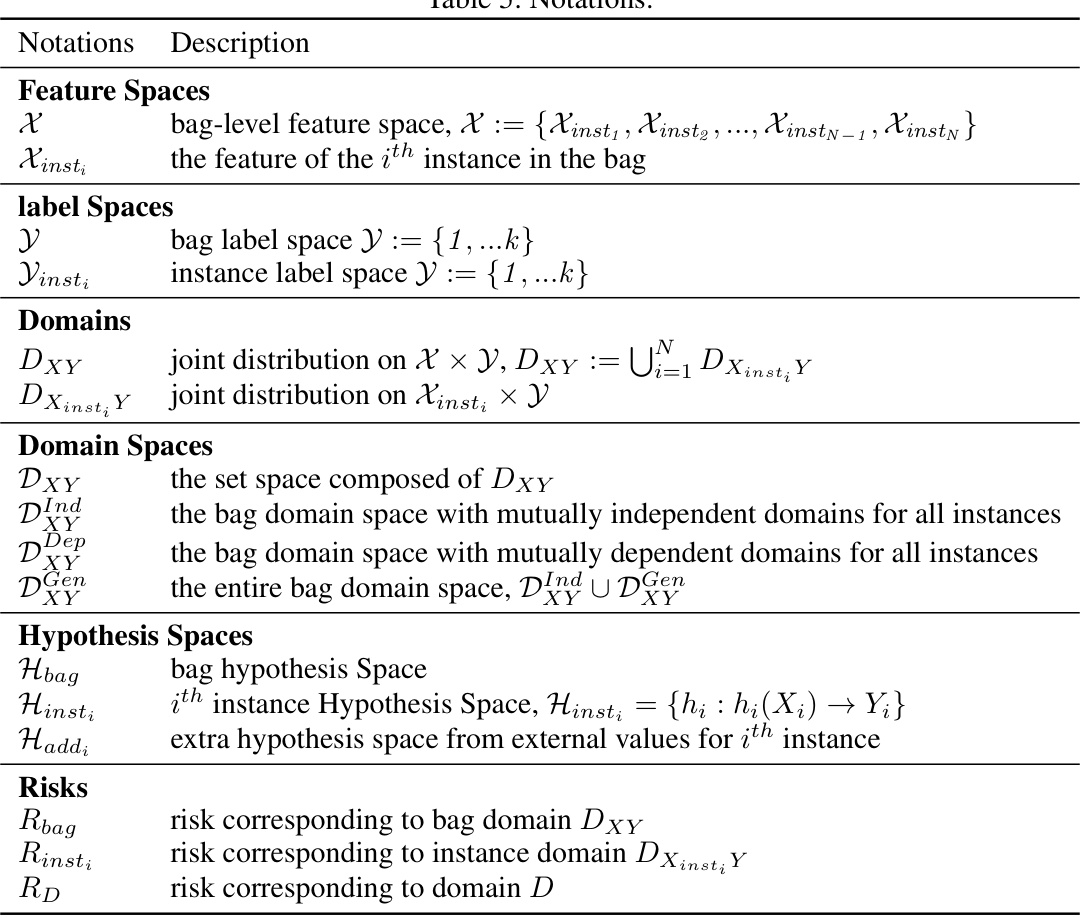

TL;DR#

Multiple Instance Learning (MIL), particularly deep MIL, is widely used for cost-effective learning from data where labeling individual instances is expensive. However, existing research focuses primarily on bag-level learnability, overlooking the crucial instance-level perspective. This creates a knowledge gap about whether a MIL algorithm is actually capable of learning at the instance level. This paper addresses this gap by introducing a novel theoretical framework based on Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) learning theory.

The study uses the PAC learning framework to derive the necessary and sufficient conditions that deep MIL algorithms must satisfy to achieve instance-level learnability. It considers two key scenarios: statistically independent instances and the general case where instances might be dependent. The theoretical findings are then applied to analyze various existing deep MIL algorithms, revealing significant differences in their instance-level learnability. Experiments validate the theoretical analysis, confirming the accuracy of the proposed conditions and providing empirical support for the conclusions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multiple instance learning (MIL) and related fields because it provides a much-needed theoretical framework for evaluating the instance-level learnability of deep MIL algorithms. This framework addresses a significant gap in the existing literature and offers valuable insights for designing more effective and reliable MIL models. Furthermore, the paper’s findings have significant implications for various applications of MIL, including medical image analysis and time series analysis. The theoretical results are validated by comprehensive empirical studies, adding to the paper’s value and reliability.

Visual Insights#

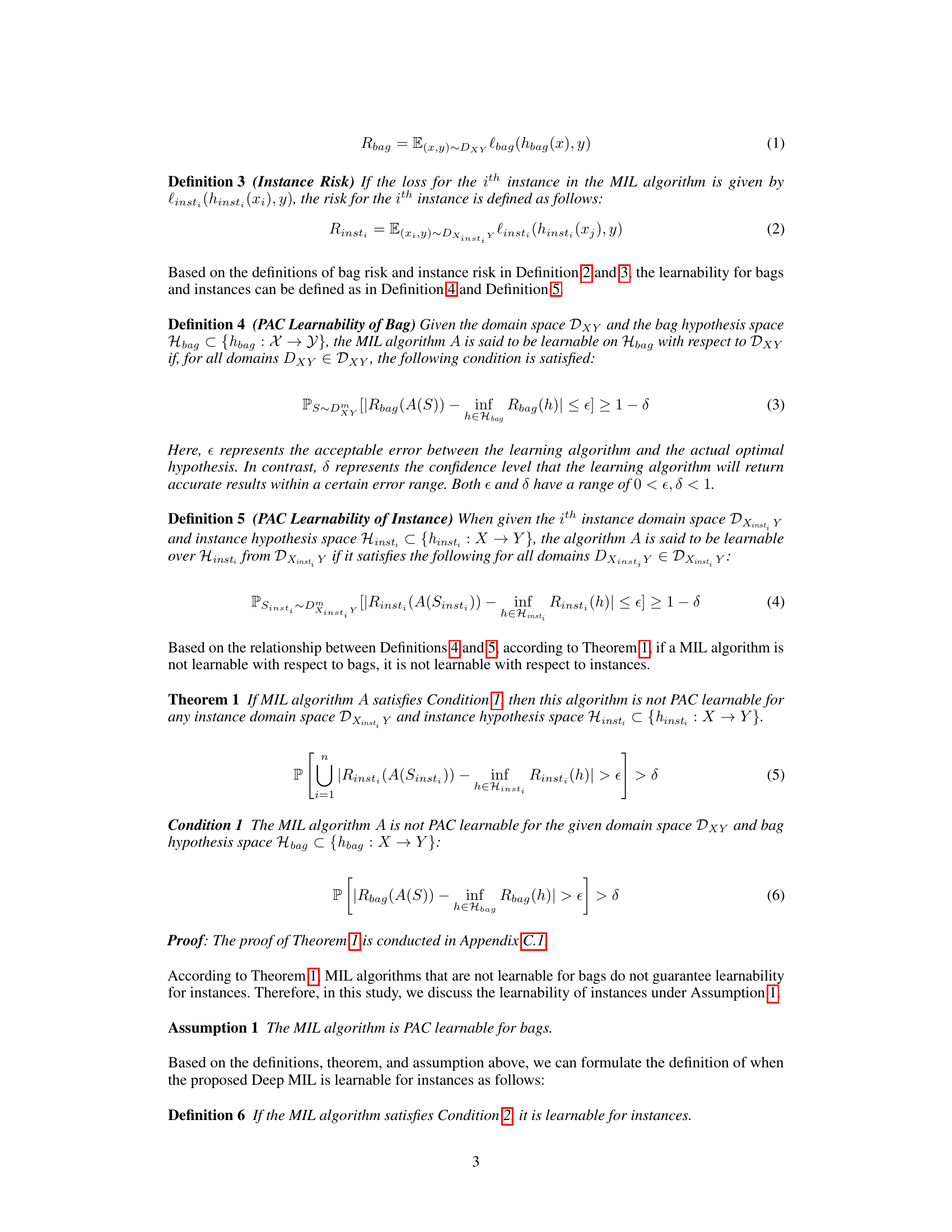

🔼 This figure shows an example of multi-instance learning data. Each ‘bag’ contains multiple instances, some positive (red) and some negative (blue). The bag is labeled positive if at least one instance is positive, and negative only if all instances are negative. This illustrates the core concept of multiple instance learning, where the labels are assigned to bags of instances rather than individual instances.

read the caption

Figure 1: The data structure consisting of multi-instances (Blue: Negative, Red: Positive) [16].

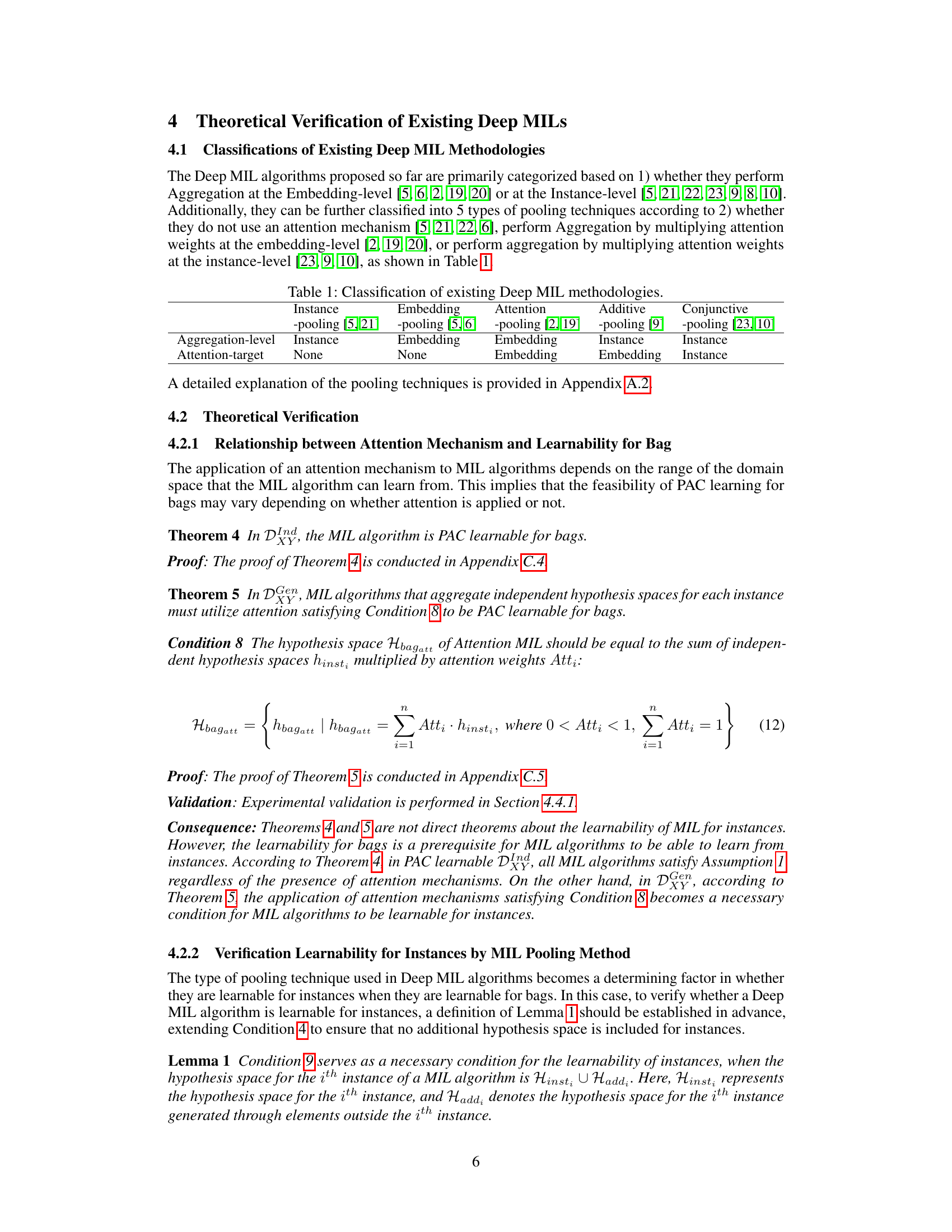

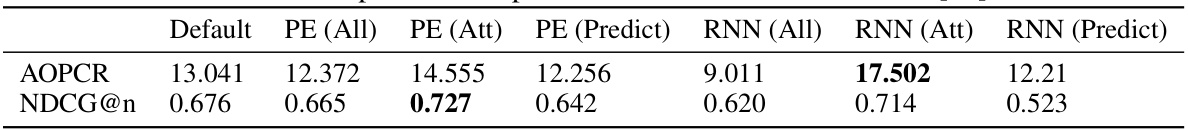

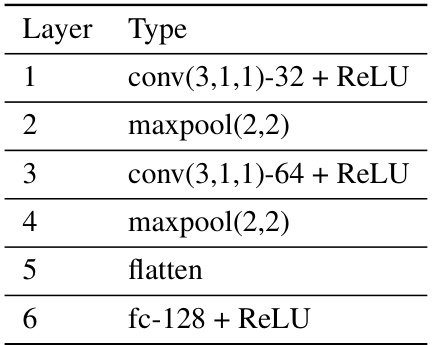

🔼 This table classifies existing deep multiple instance learning (MIL) methodologies based on three criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding level or instance level), 2) whether an attention mechanism is used or not, and 3) if an attention mechanism is used, at which level the attention weights are applied (embedding level or instance level). The table lists several example pooling methods for each category.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

In-depth insights#

Deep MIL Learnability#

The concept of “Deep MIL Learnability” explores the theoretical and practical capabilities of deep multiple instance learning (MIL) models to learn effectively at the instance level. A core challenge is that MIL traditionally only labels bags of instances, not individual instances, making instance-level learning indirect and requiring careful analysis. The research investigates the conditions under which deep MIL algorithms can successfully generalize to individual instances. This involves examining the hypothesis spaces of both bag and instance level predictions, and how these spaces relate to overall learnability using frameworks like Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) learning. The study highlights critical differences between different pooling mechanisms in deep MIL, showing some lead to instance-level learnability under specific conditions and others do not. Key theorems are developed that define these conditions mathematically, tying instance-level learnability to the choice of pooling method (e.g., Conjunctive pooling being more likely to be learnable) and the structure of the data (e.g., independent vs. dependent instances). Ultimately, the work offers a valuable theoretical framework for assessing the instance-level learning capacity of existing and future deep MIL architectures.

PAC Framework#

The Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) framework provides a robust theoretical foundation for analyzing the learnability of algorithms. In the context of Multiple Instance Learning (MIL), a PAC analysis would rigorously examine the conditions under which an MIL algorithm can reliably learn instance-level labels from only bag-level annotations. Key aspects include defining the hypothesis space, identifying the appropriate loss function, and determining bounds on the sample complexity and generalization error. A core challenge is establishing sufficient conditions to ensure that learning at the bag level translates to accurate instance-level predictions. A successful PAC analysis would offer guarantees on the performance of MIL algorithms beyond empirical observations, providing a deeper understanding of their capabilities and limitations. It is particularly useful in assessing the effectiveness of various pooling strategies and the impact of instance dependencies within the bags.

Pooling Methods#

Pooling methods are crucial in multiple instance learning (MIL), particularly deep MIL, for aggregating information from individual instances within a bag to form a bag-level representation. The choice of pooling method significantly impacts the model’s ability to learn effectively at both the bag and instance levels. Traditional methods, like max and mean pooling, are simple but may not capture complex relationships between instances. More sophisticated methods, such as attention-based pooling (e.g., additive, attention, conjunctive) incorporate instance-specific weights, offering improved performance by emphasizing influential instances. However, the theoretical learnability of these advanced methods is a critical concern; the paper explores the conditions under which these pooling techniques can guarantee instance-level learnability. The analysis reveals that certain pooling methods, under specific conditions, can ensure both bag-level and instance-level learning, highlighting the importance of choosing methods carefully based on theoretical understanding and the dataset’s properties. The findings underscore the need to move beyond empirical evaluations and to base algorithm design on rigorous theoretical foundations for reliable instance-level learning in MIL.

MD-MIL Analysis#

In the hypothetical ‘MD-MIL Analysis’ section, a crucial aspect would be assessing the effectiveness of applying multi-dimensional multiple instance learning (MD-MIL) techniques to complex datasets. This would involve evaluating how well different MD-MIL architectures capture the intricate relationships between instances across multiple dimensions, and how these relationships influence prediction accuracy and robustness. A key focus would be on understanding the impact of different pooling mechanisms, comparing their effectiveness in aggregating information from various dimensions. The analysis should consider computational efficiency and the scalability of MD-MIL to handle large and high-dimensional datasets, alongside assessing the interpretability of the model’s predictions and the ability to extract meaningful insights from the learned representations. The analysis might also explore the limitations of MD-MIL and suggest potential avenues for improvement. Comparative analysis with traditional MIL techniques would provide valuable insights into the situations where MD-MIL offers superior performance. Overall, a thorough ‘MD-MIL Analysis’ would be essential for guiding the design and application of MD-MIL in practical scenarios.

Future of MIL#

The future of Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) hinges on addressing its current limitations and exploring new avenues. Improved theoretical foundations are crucial, moving beyond current empirical analyses to establish stronger guarantees of instance-level learnability. Addressing high-dimensional data is key, as real-world data often involves complex, multi-modal instances. This requires sophisticated aggregation techniques that can effectively capture inter-instance relationships. Incorporating uncertainty and noise into MIL models is another critical area, as real-world data is rarely clean and perfectly labeled. Finally, developing more explainable and interpretable MIL models will increase trust and adoption, particularly in high-stakes applications like medical diagnosis. Future research should also focus on efficient algorithms scalable to massive datasets, along with better integration with other machine learning paradigms.

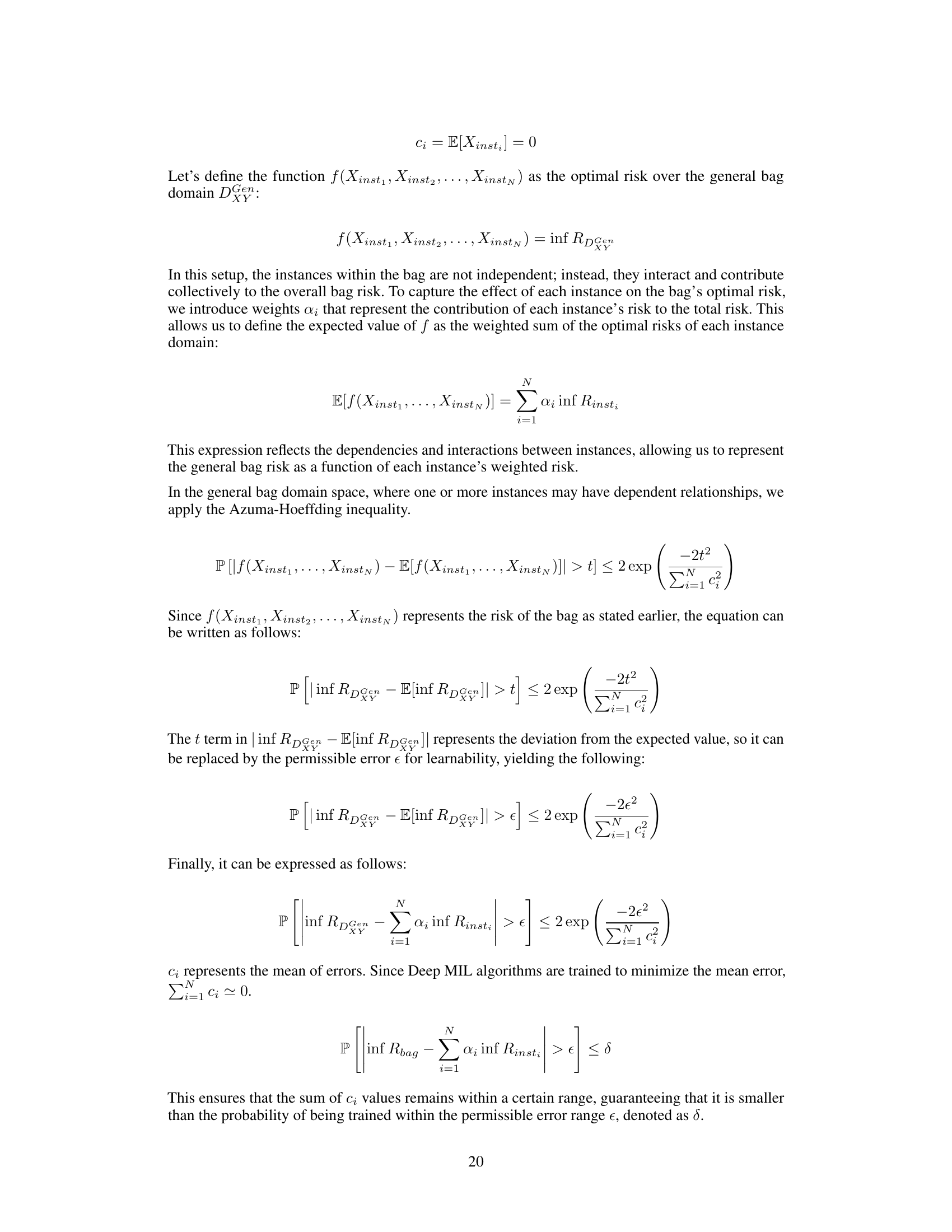

More visual insights#

More on figures

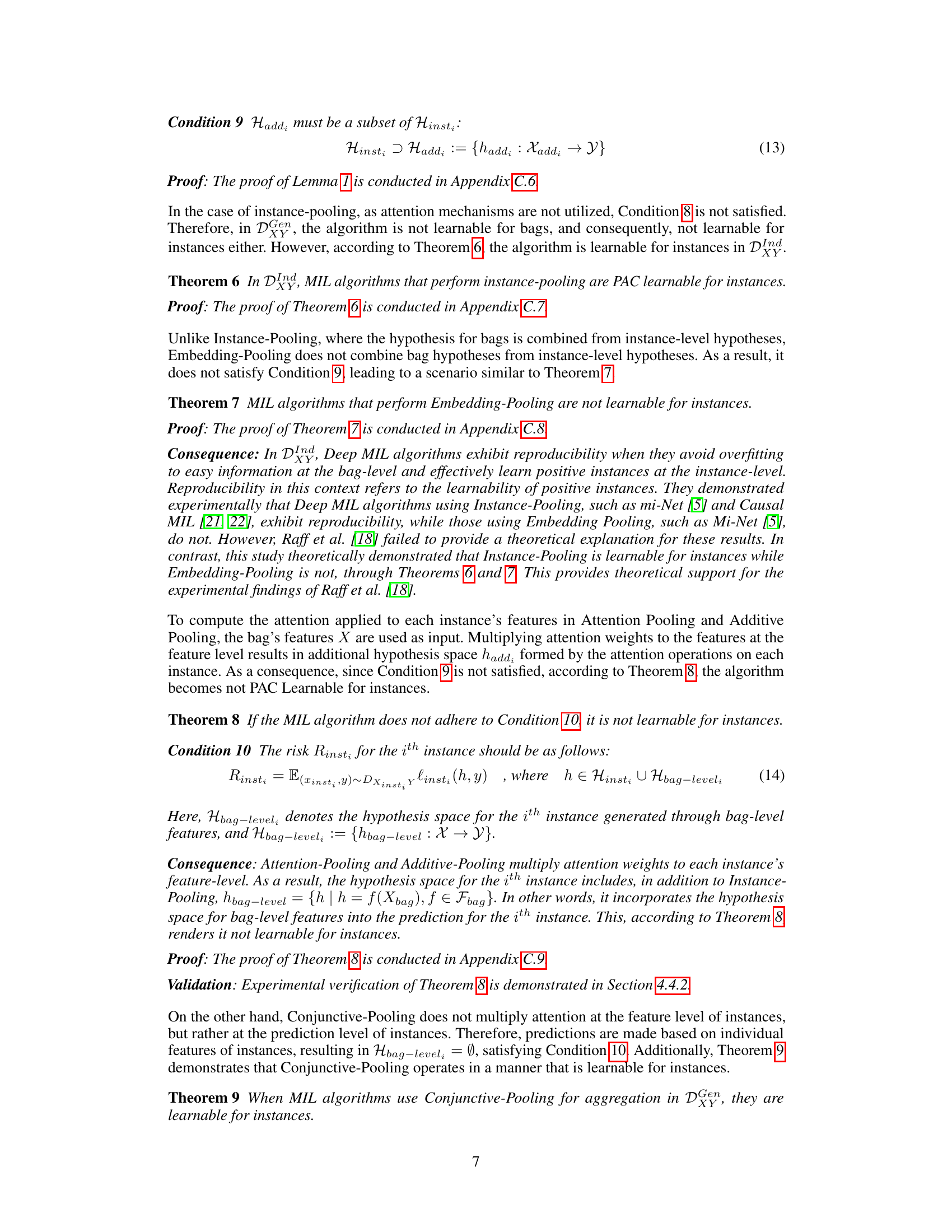

🔼 This figure summarizes the definitions, relationships, and results of the theorems that form the theoretical framework proposed in the study. It visually represents how the learnability for bags and instances are related in different hypothesis spaces (independent and general). The theorems are categorized, showing which pooling methods are learnable under specific conditions and which are not. The diagram clarifies the relationships between the theorems, visually guiding the reader through the theoretical framework.

read the caption

Figure 2: Relationships between theorems: Blue arrows indicate that the pooling methods are learnable when our proposed conditions are satisfied; Red arrows indicate that they are not learnable when the conditions are not satisfied.

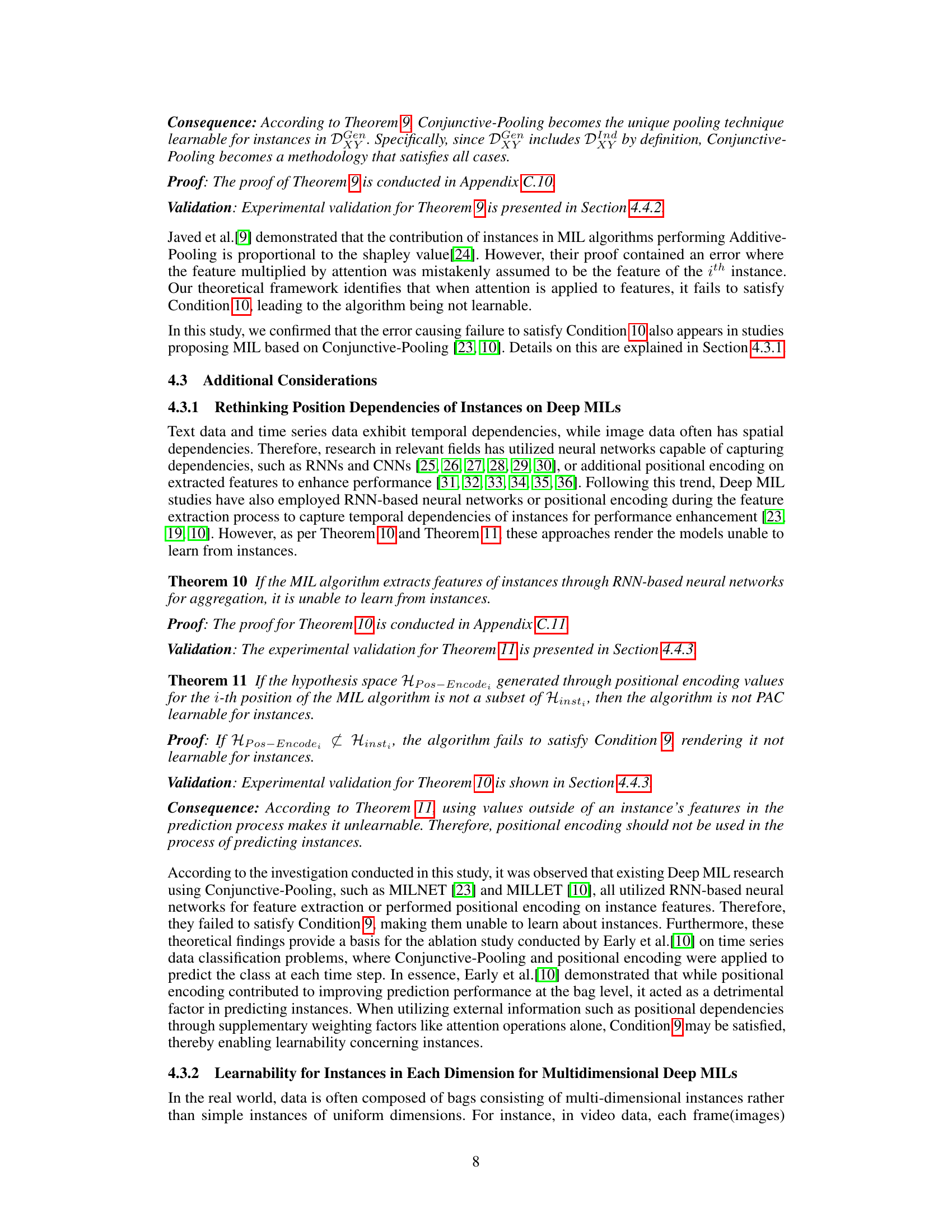

🔼 This figure shows examples of synthetic datasets used to verify Theorem 5. Each row represents a different label (0-3) assigned to the bag of 10 MNIST digits based on the presence or absence of specific digits. This demonstrates the labeling criteria used to create a synthetic dataset for evaluating the learnability of different MIL algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 3: Examples of synthetic dataset to verify Theorem 5.

🔼 This figure summarizes the definitions, relationships, and results of the theorems that constitute the theoretical framework. It visually represents which pooling methods are learnable for instances under different conditions (independent vs. general bag domain spaces), illustrating the connections between the theorems and their implications for instance-level learnability in Deep MIL.

read the caption

Figure 2: Relationships between theorems: Blue arrows indicate that the pooling methods are learnable when our proposed conditions are satisfied; Red arrows indicate that they are not learnable when the conditions are not satisfied.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of multiple instance learning (MIL). In MIL, data is organized into bags, where each bag contains multiple instances. Each bag is labeled as either positive or negative. A bag is labeled as positive if at least one of its instances is positive, and negative only if all instances are negative. The blue instances represent negative instances, while the red instances represent positive instances.

read the caption

Figure 1: The data structure consisting of multi-instances (Blue: Negative, Red: Positive) [16].

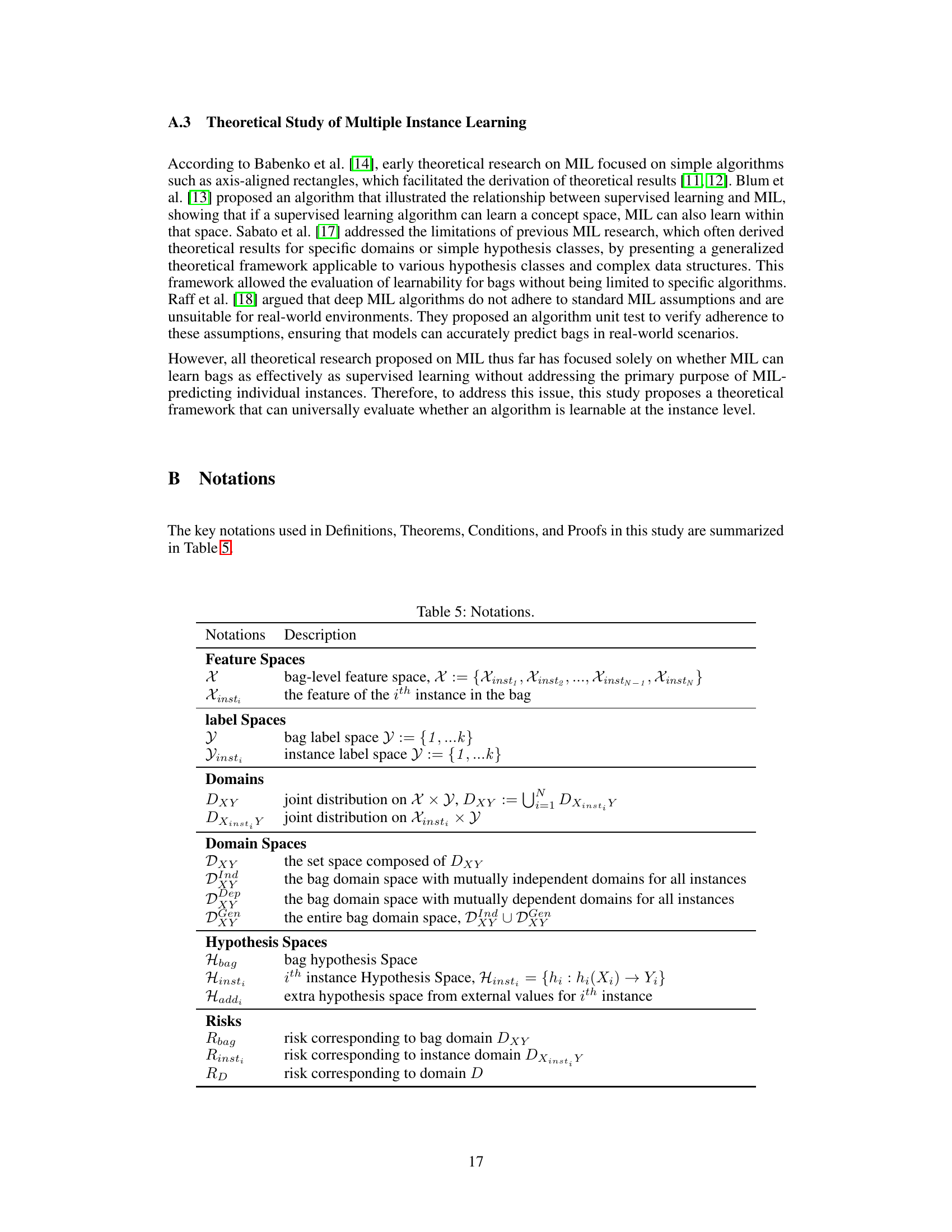

More on tables

🔼 This table classifies existing deep multiple instance learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level of aggregation (embedding-level vs. instance-level) and 2) the use of attention mechanisms (none, embedding-level, or instance-level). It shows five types of pooling techniques used in Deep MIL algorithms and their characteristics. The table helps to contextualize the discussion of various Deep MIL algorithms within the paper.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

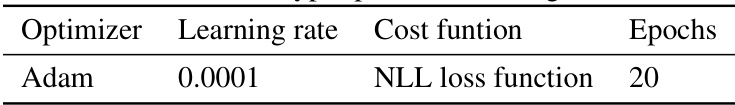

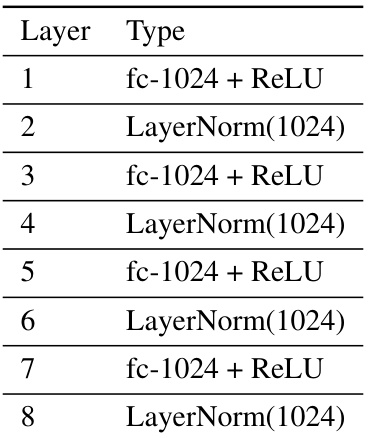

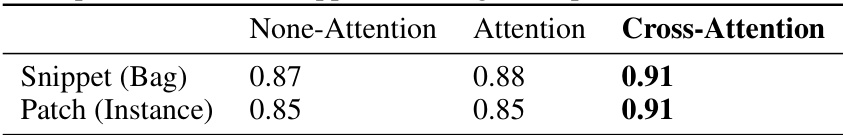

🔼 This table compares the performance of several deep MIL algorithms on both bag-level and instance-level prediction tasks. The metrics used are Macro-F1, AUROC, and the difference between the instance and bag performance (PInst - PBag) for each algorithm. The goal is to show how well each algorithm performs instance-level predictions relative to its bag-level predictions. Algorithms with smaller differences are considered better at instance-level learning.

read the caption

Table 3: Prediction performance comparison of MIL algorithms on bags and instances.

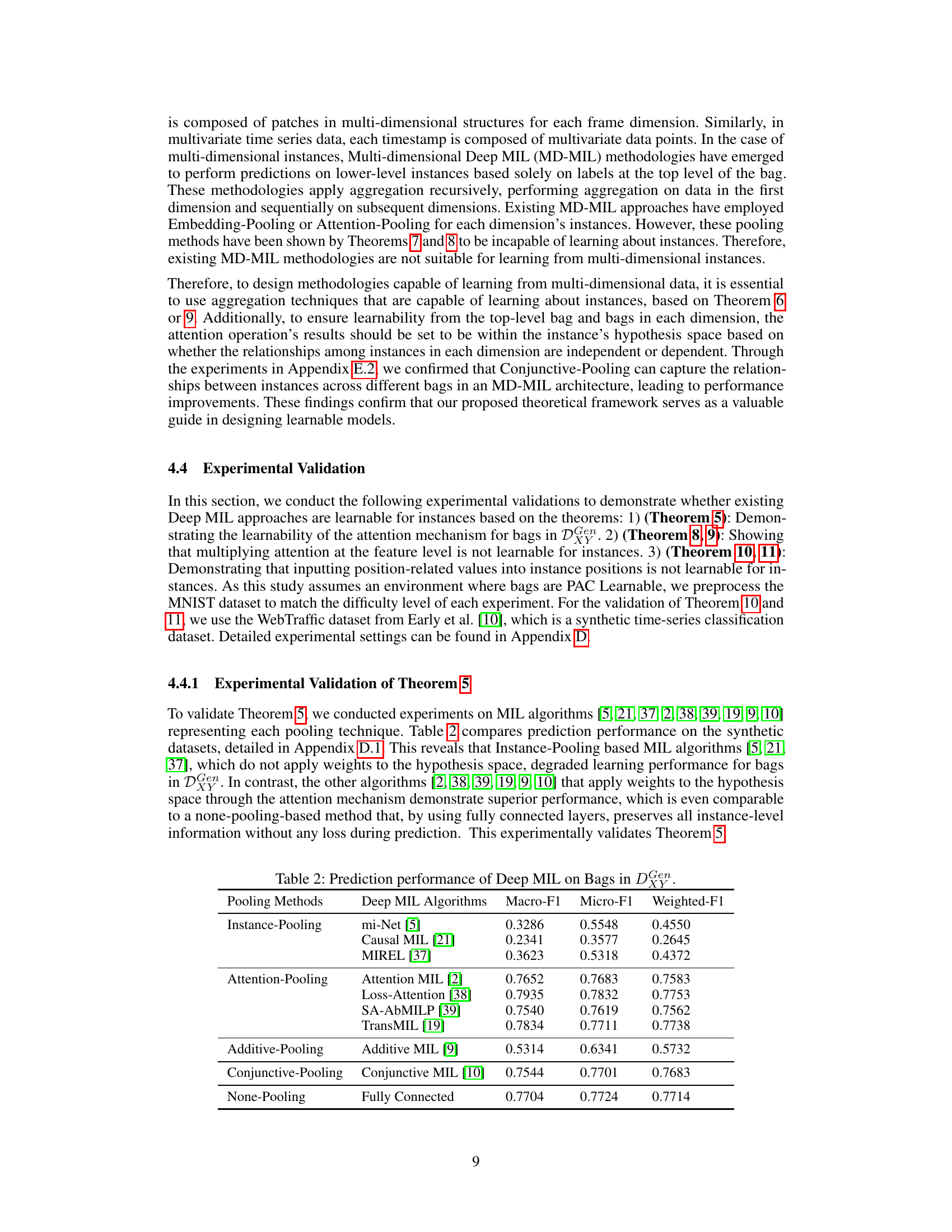

🔼 This table presents the Macro-F1, Micro-F1, and Weighted-F1 scores, along with AUROC, achieved by various Deep MIL algorithms on a synthetic dataset designed for evaluating bag-level learnability. The algorithms are categorized by their pooling method (Instance-Pooling, Attention-Pooling, Additive-Pooling, Conjunctive-Pooling, and None-Pooling). The results demonstrate that algorithms employing attention mechanisms generally outperform those without attention, especially in the challenging DGenXY domain.

read the caption

Table 2: Prediction performance of Deep MIL on Bags in DGenXY.

🔼 This table categorizes existing Deep Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding-level vs. instance-level), and 2) the type of pooling technique used (no attention, embedding-level attention, instance-level attention, additive pooling, or conjunctive pooling). The table shows the different combinations of these criteria, giving an overview of the diversity of Deep MIL approaches.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table categorizes existing deep multiple instance learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding level or instance level), and 2) the type of pooling technique used (no attention mechanism, embedding-level attention, instance-level attention, additive pooling, and conjunctive pooling). It provides a concise overview of the different approaches used in Deep MIL.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table categorizes existing deep multiple instance learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding-level vs. instance-level), and 2) the type of pooling technique used (with or without attention mechanisms, and the target of attention). It lists several example algorithms for each category.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table categorizes existing deep multiple instance learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation occurs (embedding-level vs. instance-level) and 2) the presence and type of attention mechanism used (none, embedding-level attention, instance-level attention). Five types of pooling techniques are differentiated: Instance-pooling, Embedding-pooling, Attention-pooling, Additive-pooling, and Conjunctive-pooling. The table provides a concise overview of how different Deep MIL approaches handle the aggregation of instance features and whether they utilize attention mechanisms.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table classifies existing Deep Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding-level or instance-level), and 2) the type of pooling technique used (no attention, embedding attention, instance attention, additive pooling, or conjunctive pooling). It provides a concise overview of how different Deep MIL approaches differ in their aggregation strategies and the use of attention mechanisms.

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table categorizes existing Deep MIL methodologies based on two criteria: 1) the level at which aggregation is performed (embedding level or instance level) and 2) the type of pooling technique used (none, attention at embedding level, attention at instance level, additive, or conjunctive). Each category is further sub-categorized by the target of attention (instance or embedding).

read the caption

Table 1: Classification of existing Deep MIL methodologies.

🔼 This table presents the Macro-F1, Micro-F1, and Weighted-F1 scores, along with AUROC, achieved by various Deep MIL models on a synthetic dataset designed to evaluate bag-level learnability in the general bag domain space (DGenXY). The models are categorized by their pooling methods (Instance-Pooling, Attention-Pooling, Additive-Pooling, Conjunctive-Pooling, and None-Pooling). The results demonstrate the impact of different pooling methods on the ability of the Deep MIL algorithms to learn from bags in a scenario where instances within bags may exhibit dependencies, contrasting with the independent bag scenario.

read the caption

Table 2: Prediction performance of Deep MIL on Bags in DGenXY.

Full paper#