↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing vision-language models (VLMs) and large language models (LLMs) show surprisingly poor performance on spatial reasoning tasks. This is a critical limitation because spatial reasoning is a fundamental aspect of human intelligence and crucial for many real-world applications. The lack of robust spatial understanding in these models indicates a gap in their ability to process and understand information holistically, suggesting that current architectures and training methods may be insufficient.

To address these issues, the researchers created SpatialEval, a novel benchmark to evaluate spatial reasoning capabilities. SpatialEval assesses various aspects of spatial reasoning across multiple tasks using text-only, vision-only, and vision-text inputs. Results show that even with visual input, VLMs frequently struggle. Surprisingly, VLMs often perform better with text-only inputs than LLMs, revealing that their language model backbones benefit from multimodal training. Importantly, adding redundant textual information alongside visual input significantly improves performance, suggesting that better integration of multimodal cues is crucial for robust spatial reasoning in AI.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because spatial reasoning is a fundamental aspect of human intelligence that has been largely unexplored in vision-language models (VLMs). The findings challenge existing assumptions about VLM capabilities and highlight the need for improved architectures that leverage both visual and textual information effectively. The benchmark and analysis presented will significantly advance the development of more human-like AI systems.

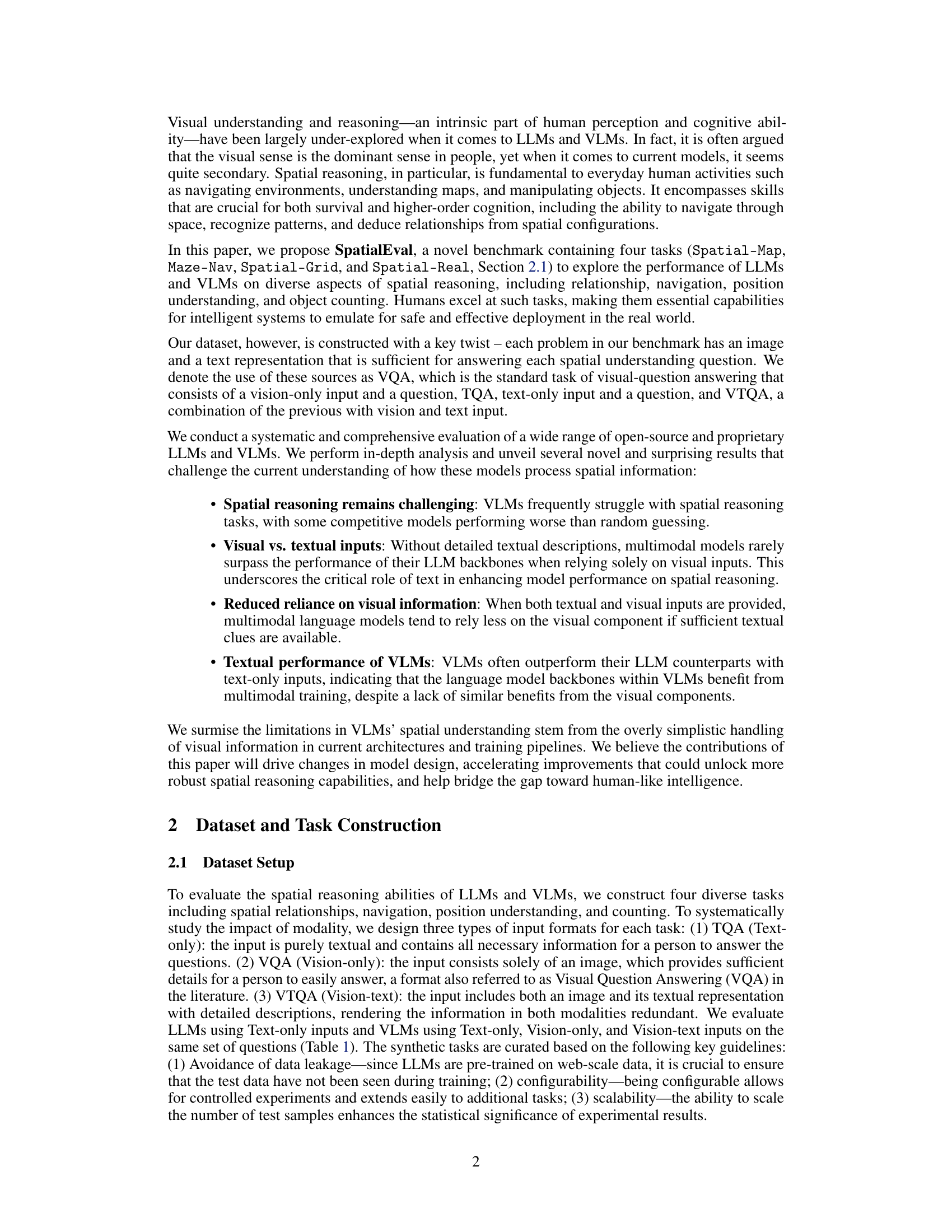

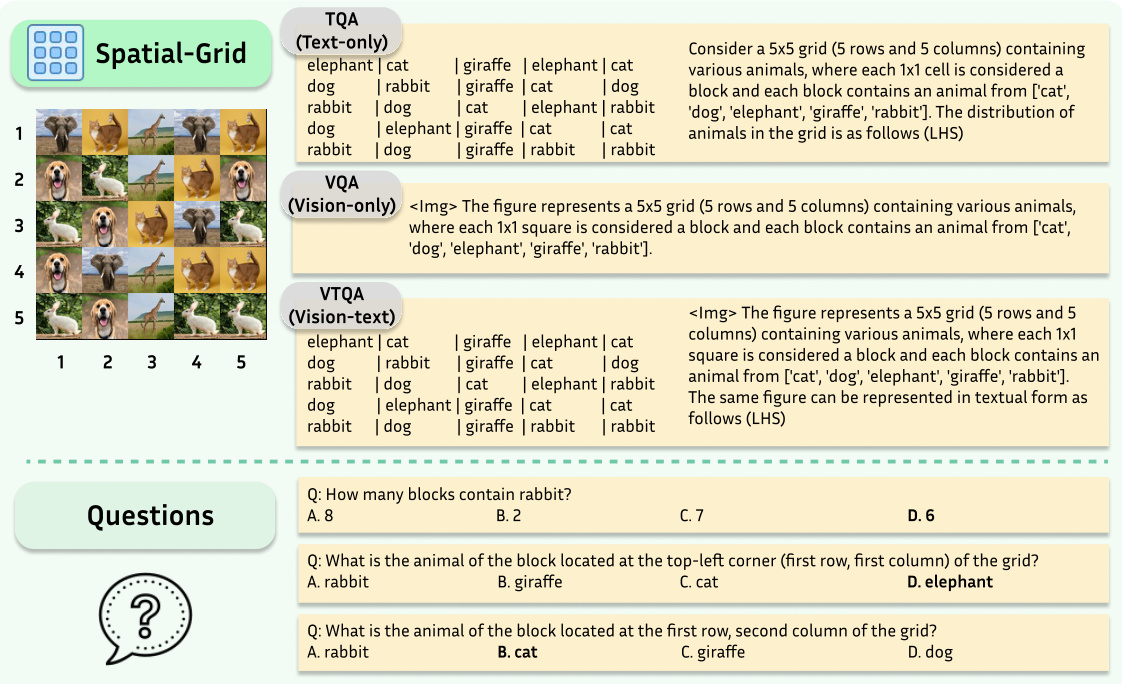

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the Spatial-Map task from the SpatialEval benchmark. The task involves understanding spatial relationships between objects shown on a map. To test the impact of different input modalities, three variations are shown: Text-only (TQA), Vision-only (VQA), and Vision-text (VTQA). Each variation shows a map, either as a text description or as an image (or both), and corresponding questions to test the model’s spatial reasoning capabilities. The example shows a map with several labeled locations and questions asking for directions and counts of objects.

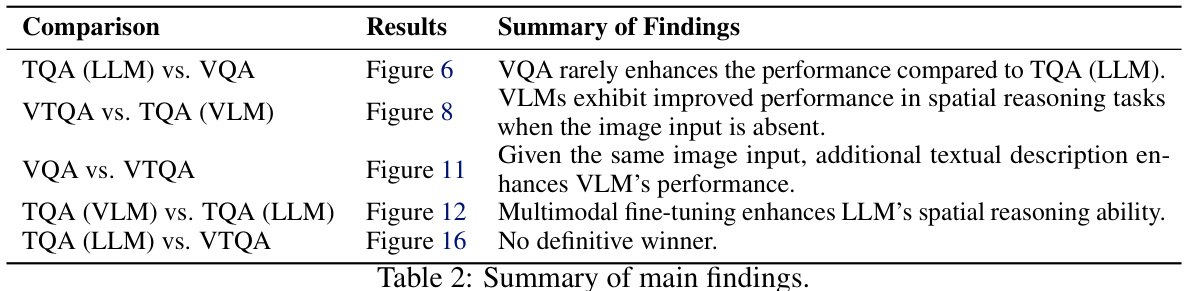

This table describes the different input modalities used for evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) in the SpatialEval benchmark. It defines the terms used to distinguish between text-only, vision-only, and vision-text inputs, clarifying which model types (LLMs or VLMs) are associated with each modality.

In-depth insights#

Spatial Reasoning#

The research paper explores spatial reasoning within the context of large language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs). A key finding is that spatial reasoning remains a significant challenge for these models, often resulting in performance below random guessing. This highlights a gap in current model architectures and training methodologies. The study also reveals the surprising observation that VLMs frequently underperform their LLM counterparts, even when provided with visual input. This suggests that current multimodal models do not effectively integrate visual information and may overly rely on textual cues. Furthermore, the research demonstrates how the inclusion of redundant textual information, even when visual data is already present, may improve model performance. Overall, the findings underscore the importance of developing more sophisticated methods for incorporating and reasoning with spatial information in both LLMs and VLMs. This involves improving the handling of visual input to bridge the gap between artificial and human-level spatial intelligence.

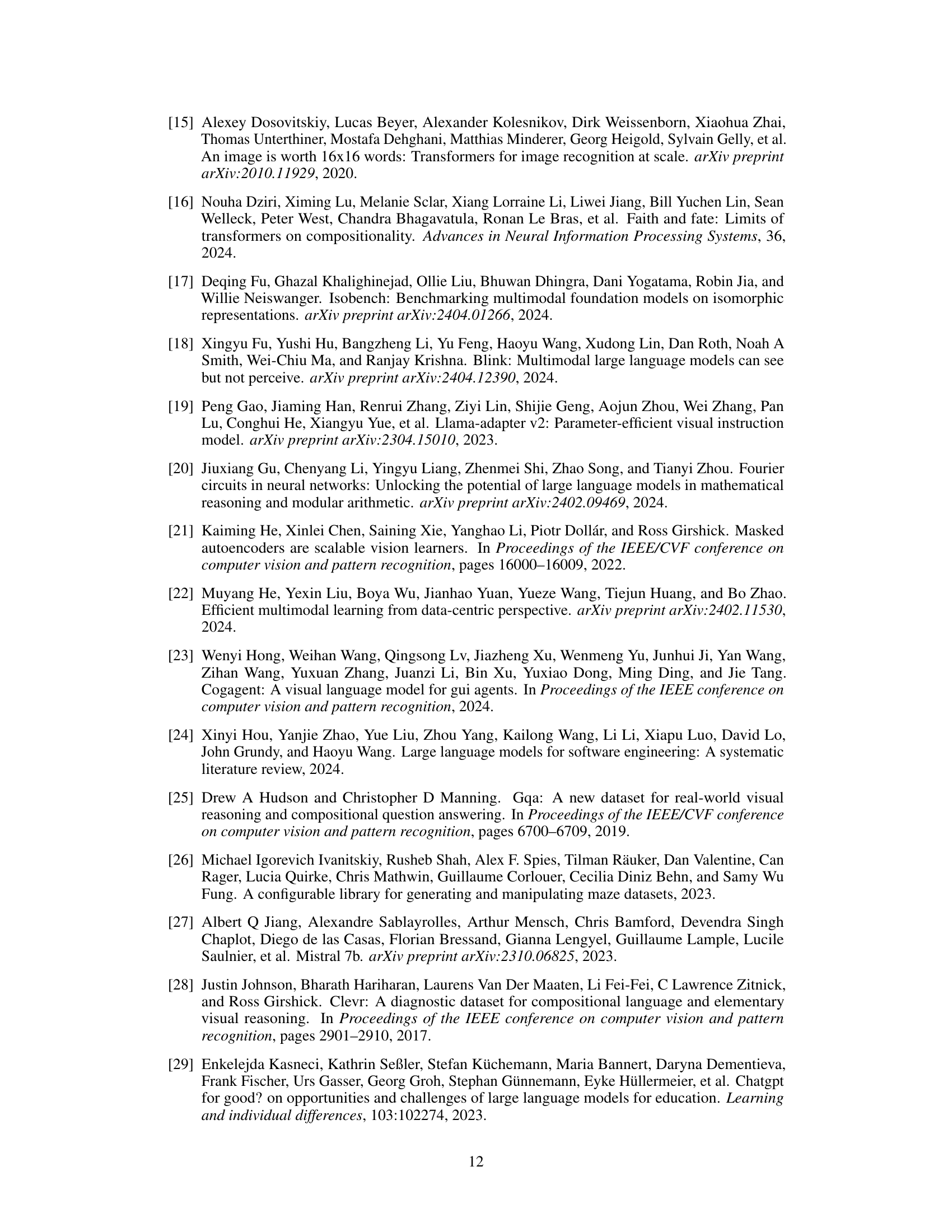

VLM vs. LLM#

The comparative analysis of Vision-Language Models (VLMs) and Language Models (LLMs) reveals crucial insights into their capabilities and limitations in handling spatial reasoning tasks. VLMs, despite incorporating visual information, often underperform LLMs, especially when textual descriptions provide sufficient contextual clues. This suggests that current VLM architectures may not effectively integrate visual and textual information, relying heavily on textual cues even when visual data is available. This phenomenon highlights the significant challenge of robust multi-modal fusion in existing VLMs. Further investigation into the architecture and training strategies of VLMs is needed to improve their ability to leverage visual input effectively. The findings indicate that simply adding visual input to an LLM does not guarantee improved performance on tasks requiring visual understanding. A more sophisticated approach to multi-modal integration is required, potentially involving the development of new architectural designs and training paradigms that effectively fuse both visual and textual information.

Modality Impact#

The study’s exploration of modality impact reveals counter-intuitive findings regarding the role of visual information in spatial reasoning tasks. While intuition might suggest that vision-language models (VLMs) would significantly outperform language models (LLMs) when visual data is added, the results demonstrate that this is often not the case. In many instances, VLMs underperform LLMs, even when provided with both textual and visual information. This suggests that current VLM architectures may not effectively integrate visual and textual data, potentially due to limitations in how visual information is processed and fused with textual cues. The reliance on visual information also varies depending on the availability of textual clues. When sufficient textual information is given, VLMs become less dependent on visual data, highlighting the potential dominance of textual processing over visual understanding in these models. This emphasizes the need for further research on improving VLM architecture to fully leverage both visual and textual input for enhanced spatial reasoning capabilities.

Visual Blindness#

The concept of “Visual Blindness” in the context of vision-language models (VLMs) highlights a critical limitation: despite incorporating visual input, these models often fail to leverage visual information effectively for spatial reasoning tasks. This “blindness” isn’t a complete inability to process images, but rather a failure to translate visual data into meaningful spatial understanding. The research indicates that when sufficient textual context is provided, VLMs often downplay or even ignore visual input, relying heavily on textual clues instead. This suggests a weakness in the model’s ability to integrate and interpret both modalities seamlessly for complex reasoning, where visual and textual data should work synergistically. The reliance on text even when visual information is available and potentially more accurate is a key finding. This challenges the assumption that adding visual input automatically enhances the performance of LLMs in spatially-rich tasks and underscores the need for architectural improvements to better fuse and interpret multimodal inputs in a more human-like way. The study’s findings have significant implications for VLM development, suggesting a need for architectural changes and training methodologies to overcome this “visual blindness” and unlock the true potential of multi-modal models for complex spatial reasoning.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work should prioritize a deeper theoretical understanding of the limitations of current vision-language models (VLMs) in spatial reasoning. Developing more sophisticated training techniques that enhance the handling of visual information and its interaction with textual data is crucial. This might involve exploring novel architectures that move beyond the simple concatenation of visual and textual features, and instead incorporate mechanisms for genuine multimodal fusion and reasoning. Furthermore, a shift in evaluation methodology is needed. While accuracy is important, it doesn’t fully capture the nuances of spatial understanding. Future benchmarks should incorporate more comprehensive metrics that assess not only the correctness of answers, but also the reasoning processes behind them. Finally, exploring the potential of different types of visual inputs is necessary. The current focus on images can be broadened to include other modalities like videos, 3D models, or even tactile data, to create more robust and generalizable spatial reasoning capabilities in VLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

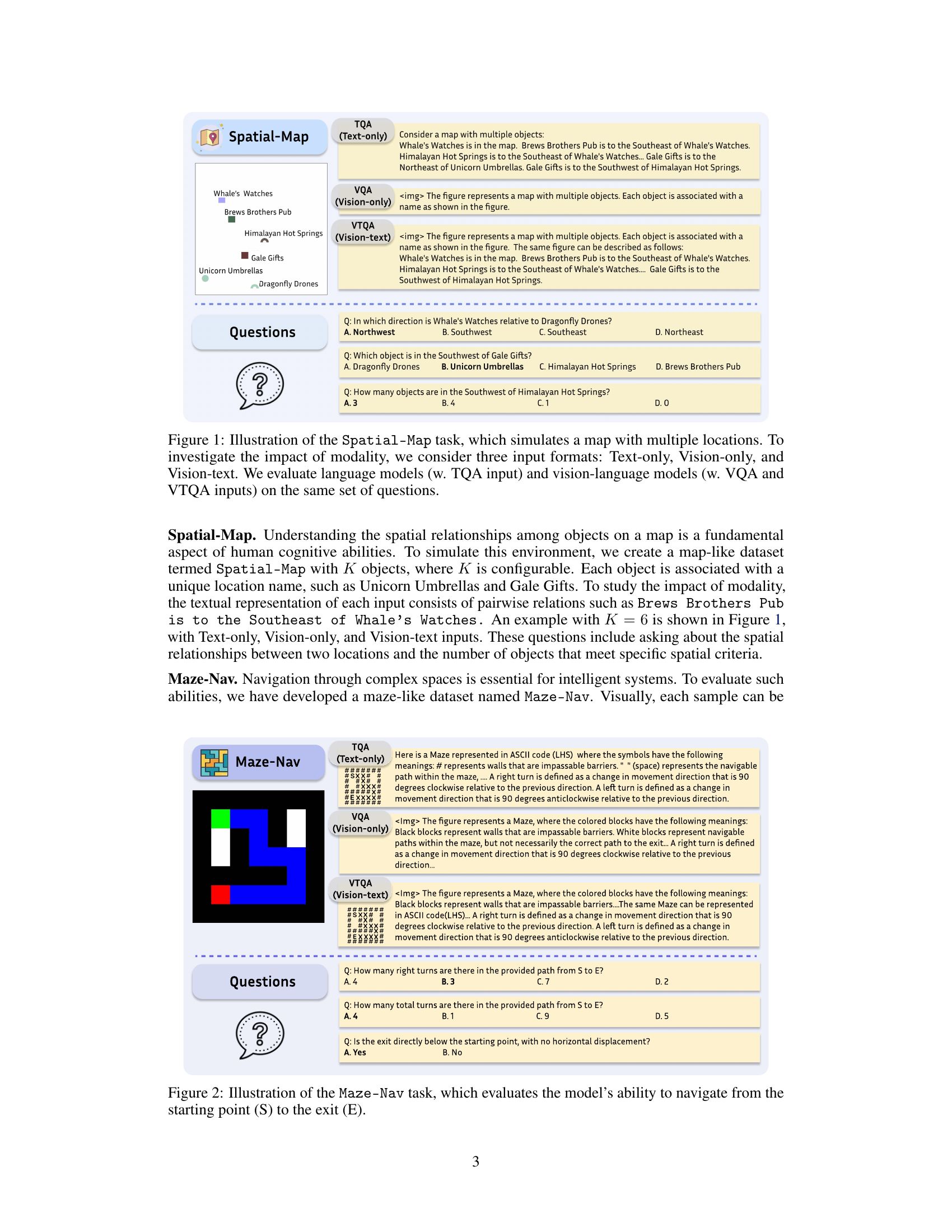

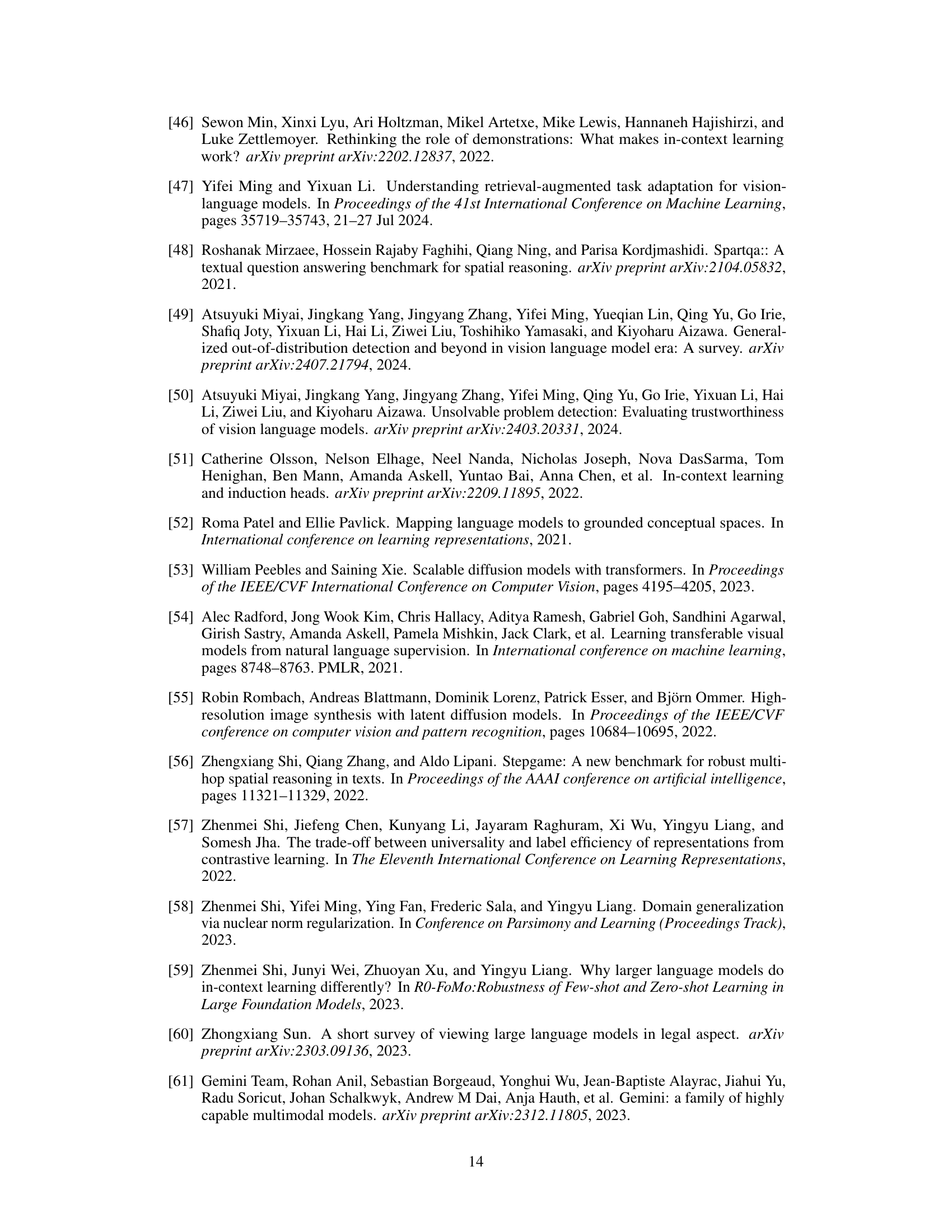

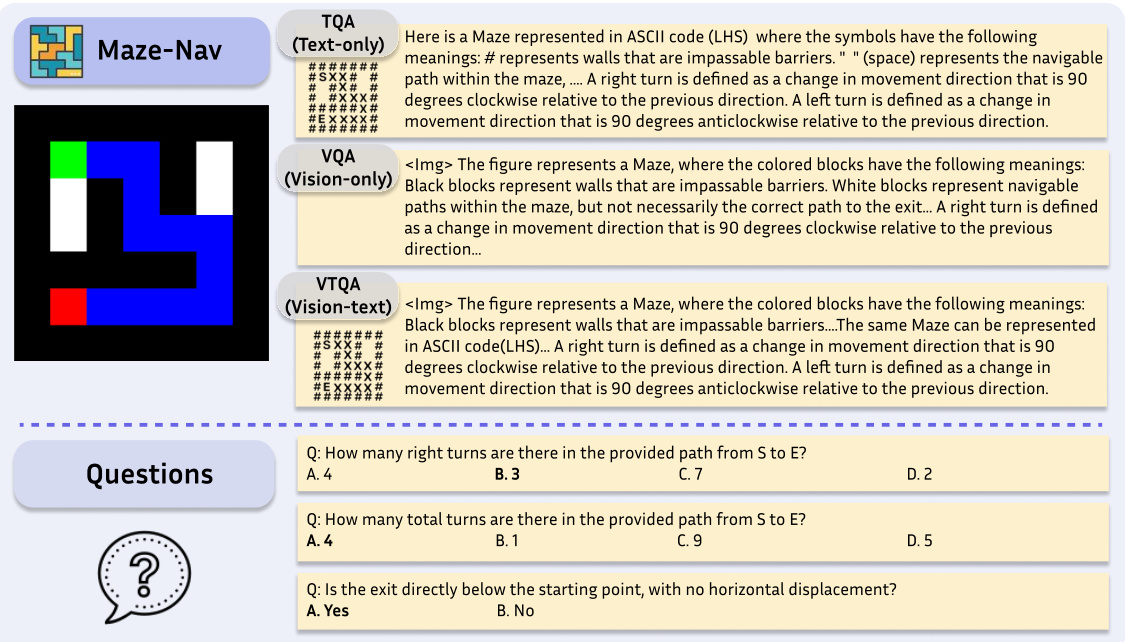

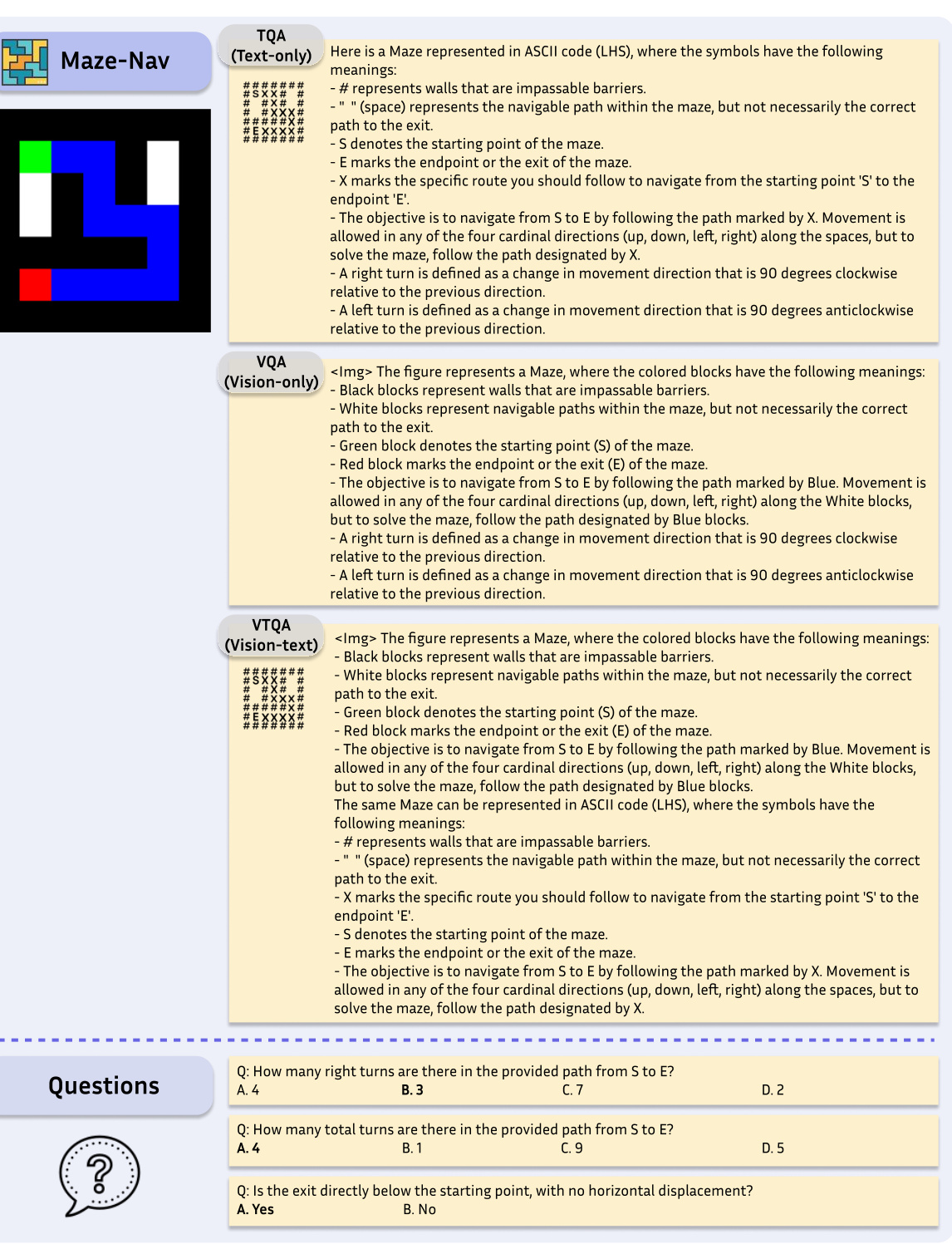

The figure illustrates the Maze-Nav task, designed to assess a model’s navigation capabilities in a maze-like environment. It shows three input modalities: Text-only (TQA), Vision-only (VQA), and Vision-text (VTQA). The Text-only input provides a textual representation of the maze using ASCII characters, while the Vision-only input presents a color-coded image representation of the maze. The Vision-text input combines both the textual and visual representations. The questions posed focus on aspects like the number of turns and the spatial relationship between the start and end points.

This figure shows an example of the Spatial-Map task from the SpatialEval benchmark. The task involves understanding spatial relationships between objects on a map. Three input modalities are shown: Text-only (TQA), providing only textual descriptions of object locations; Vision-only (VQA), showing only an image of the map; and Vision-text (VTQA), providing both an image and corresponding textual descriptions. The goal is to answer questions about the spatial relationships between the objects shown. The figure illustrates how different modalities impact the model’s ability to perform this spatial reasoning task.

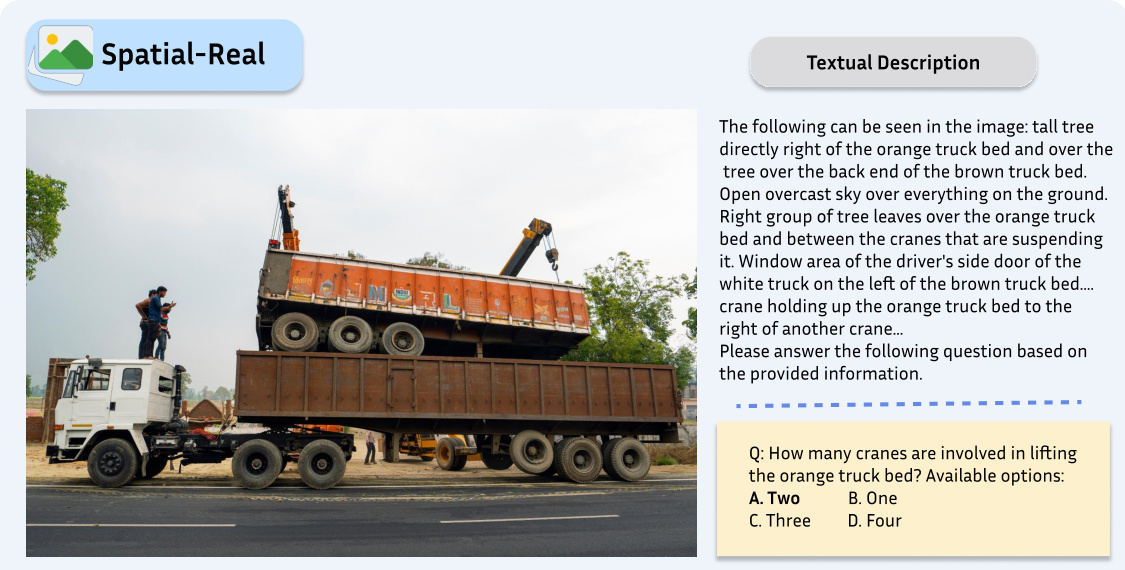

This figure shows an example from the Spatial-Real dataset. The dataset consists of real images paired with very long and detailed textual descriptions (averaging over 1000 words per image). The task is to answer questions requiring spatial reasoning based on both the image and its caption. This particular example shows a picture of a truck being lifted by cranes, and the question asks how many cranes are involved.

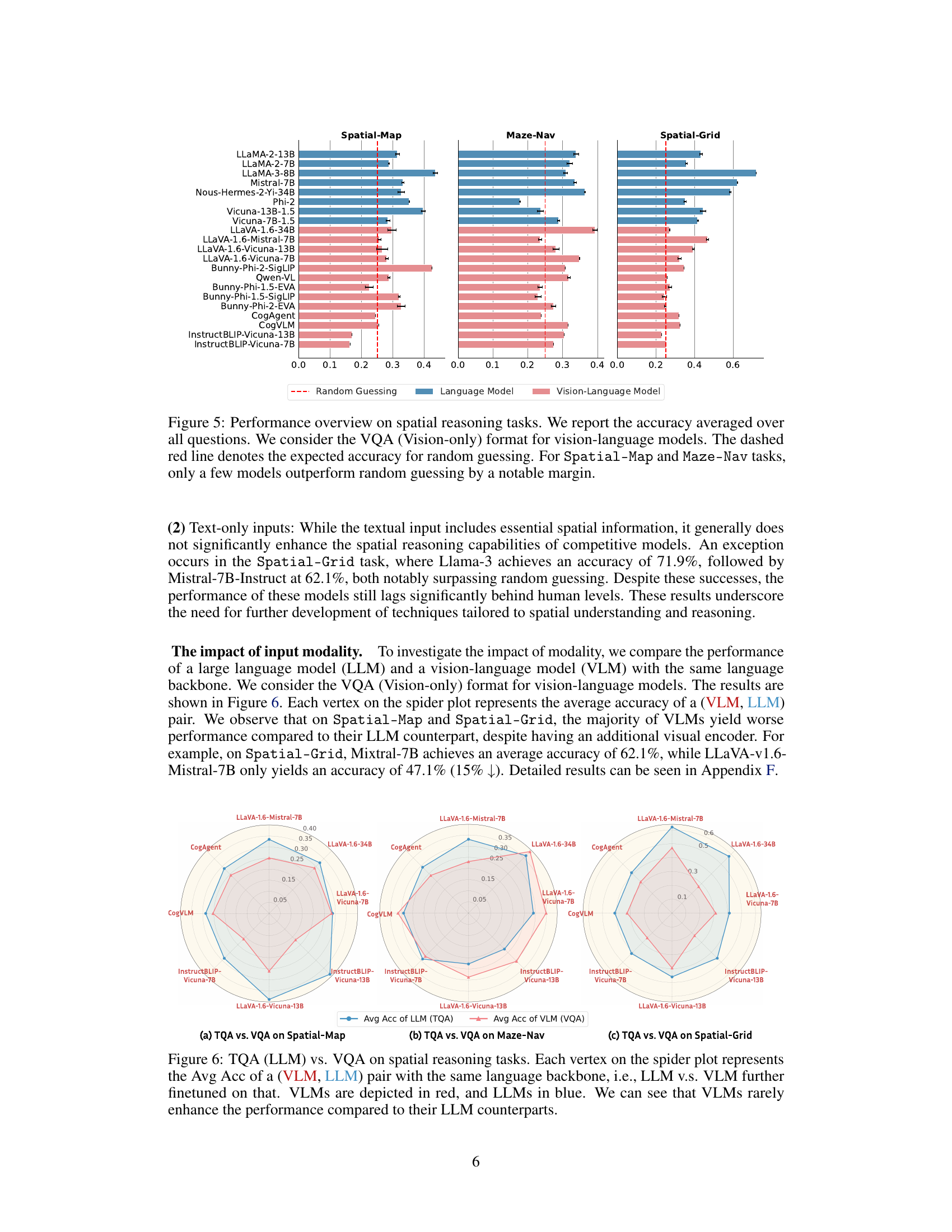

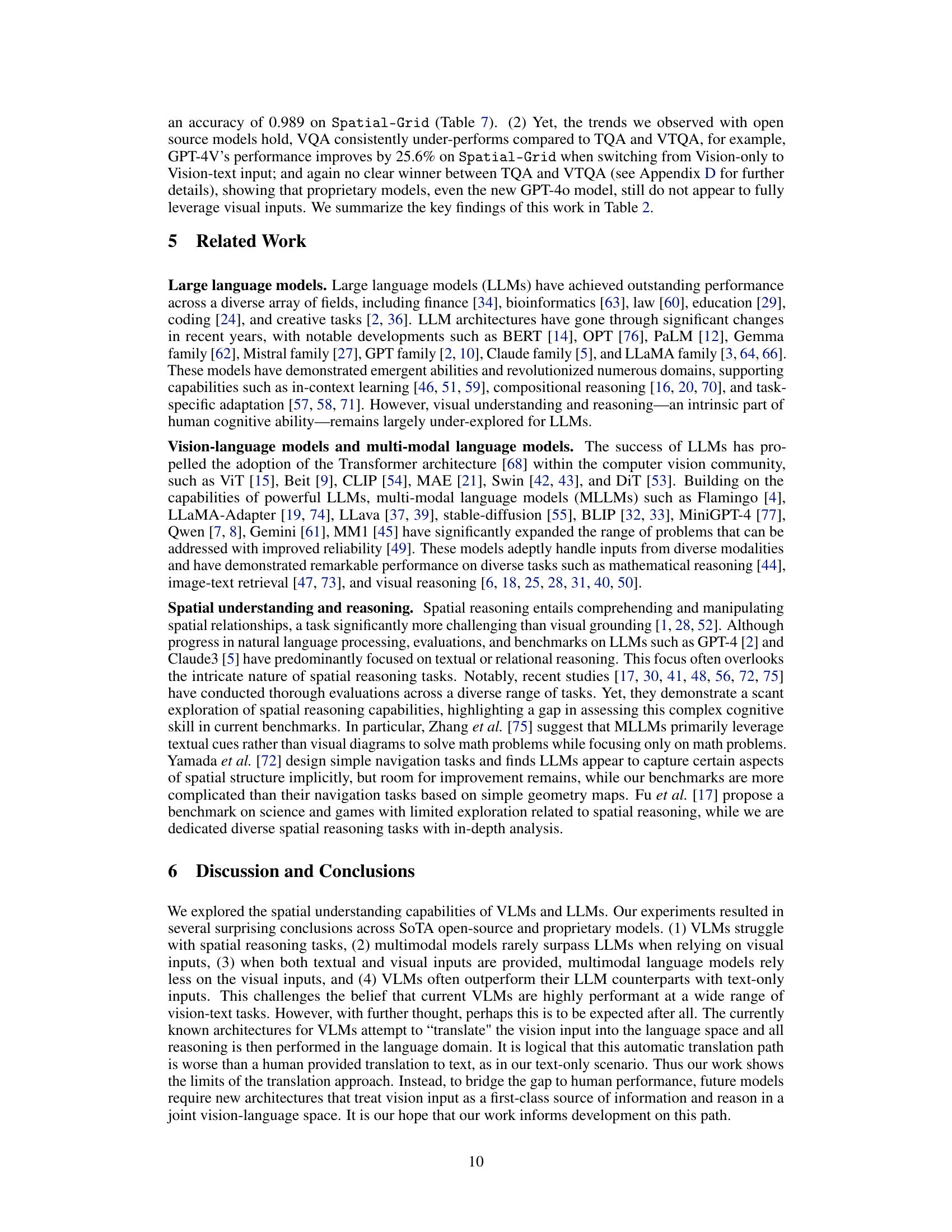

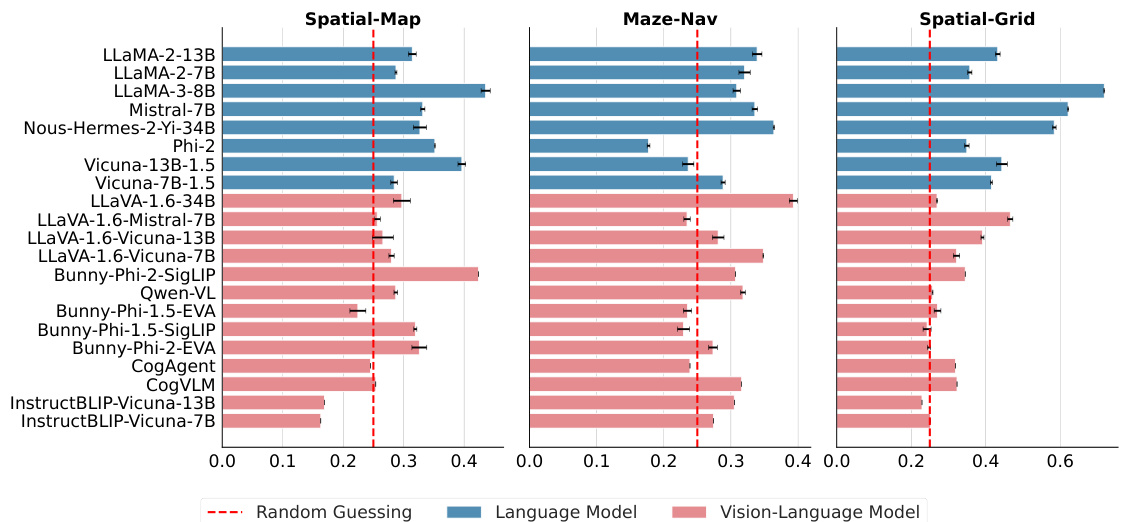

This figure presents the average accuracy of various language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs) across three spatial reasoning tasks: Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid. The performance is evaluated using the Vision-only (VQA) format for VLMs. A dashed red line indicates the expected accuracy of random guessing. The bar chart shows that most models struggle with spatial reasoning, with only a few showing performance significantly better than random chance, especially for the Spatial-Map and Maze-Nav tasks.

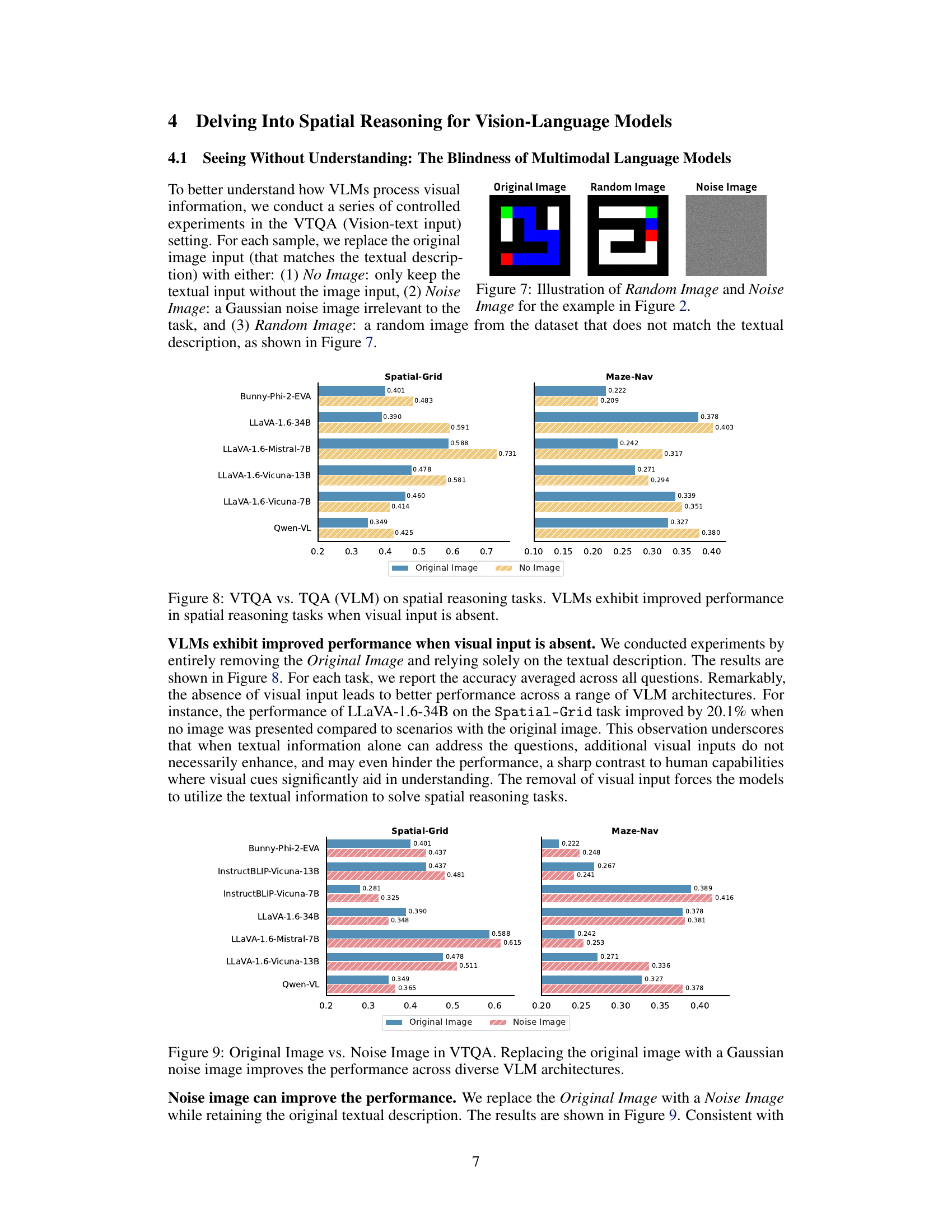

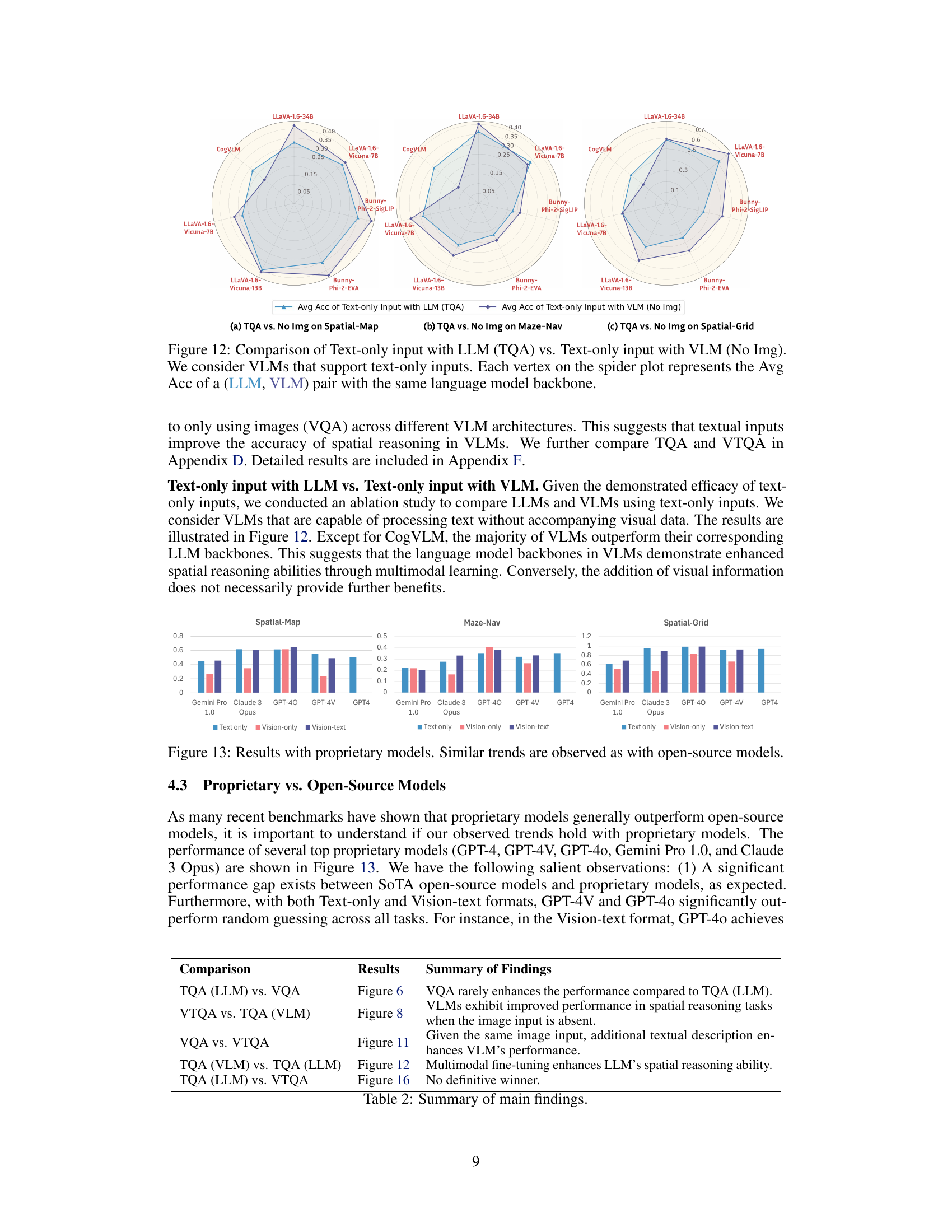

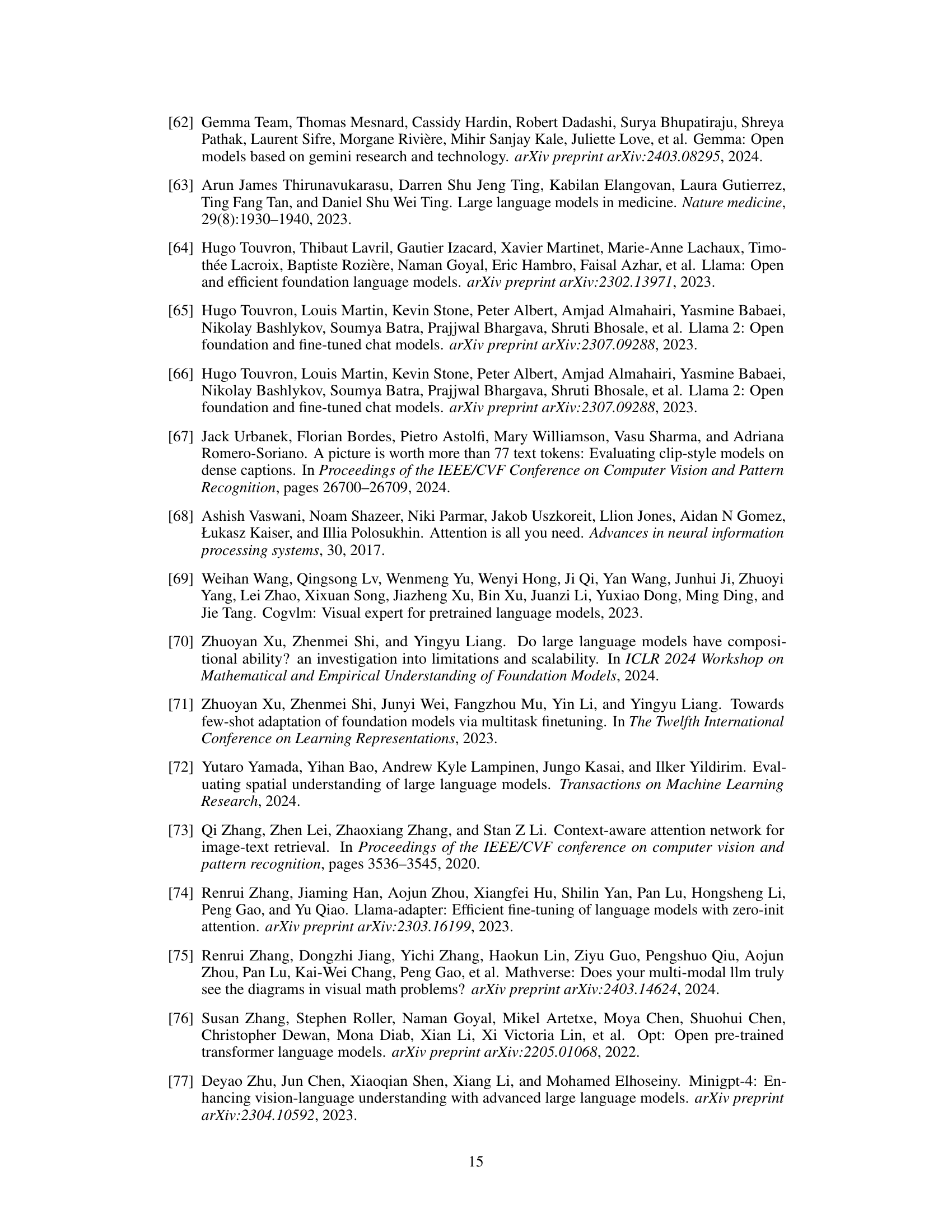

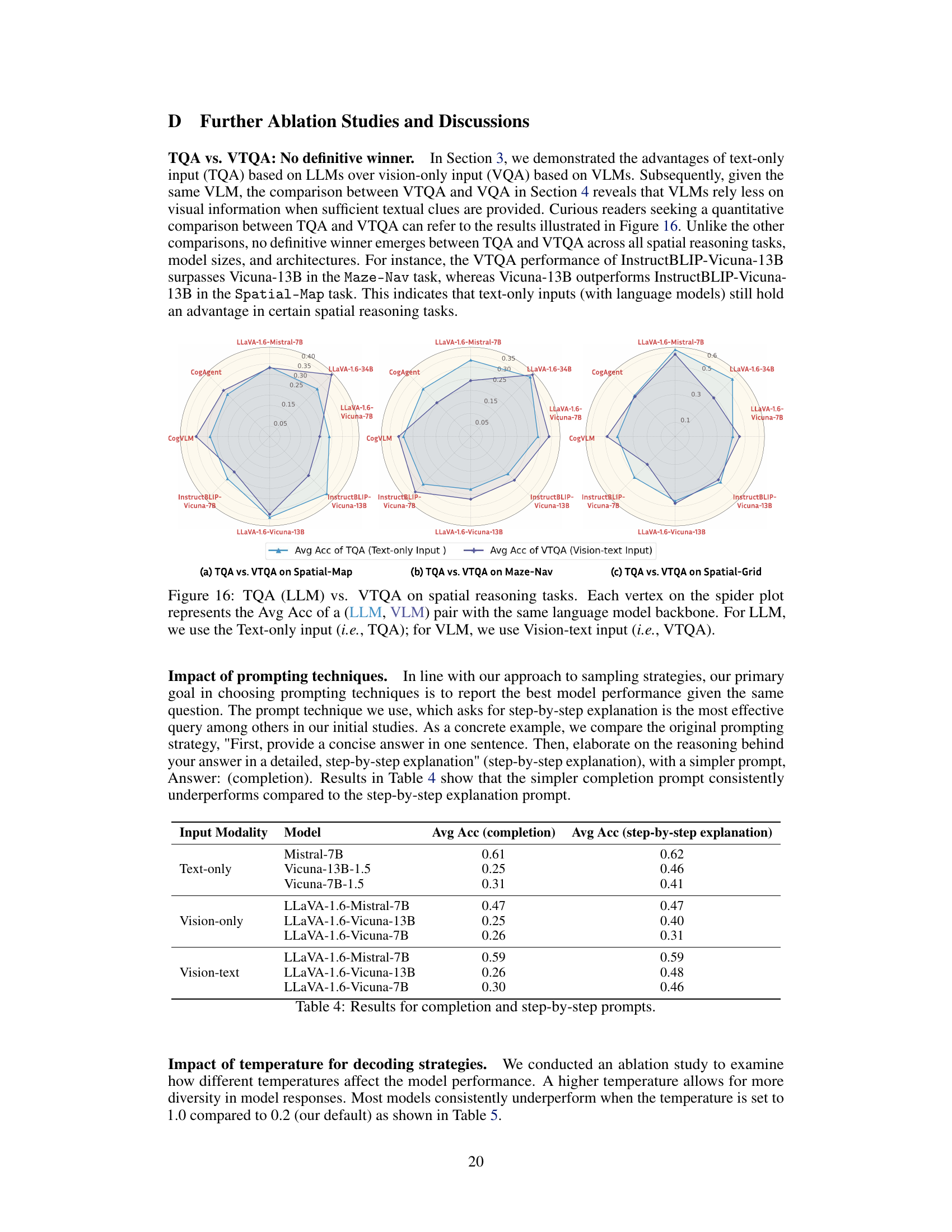

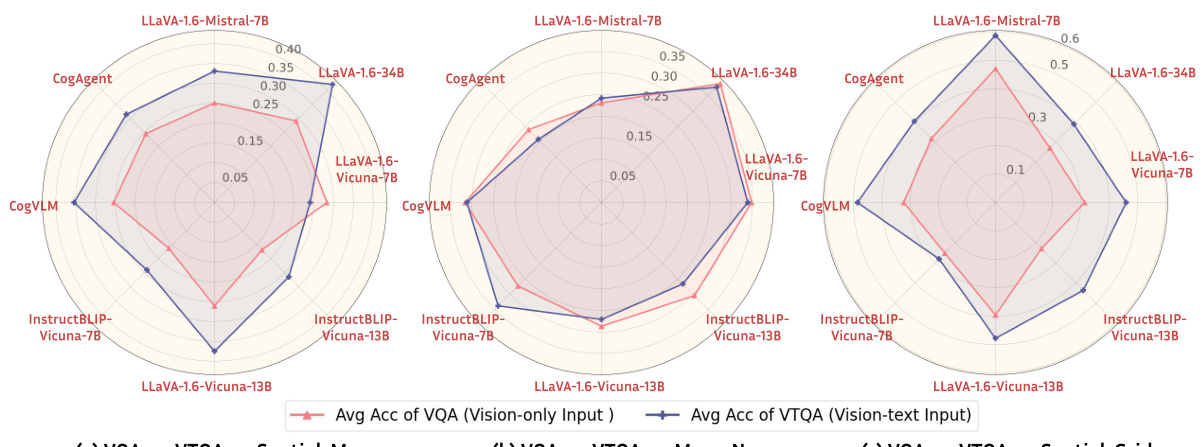

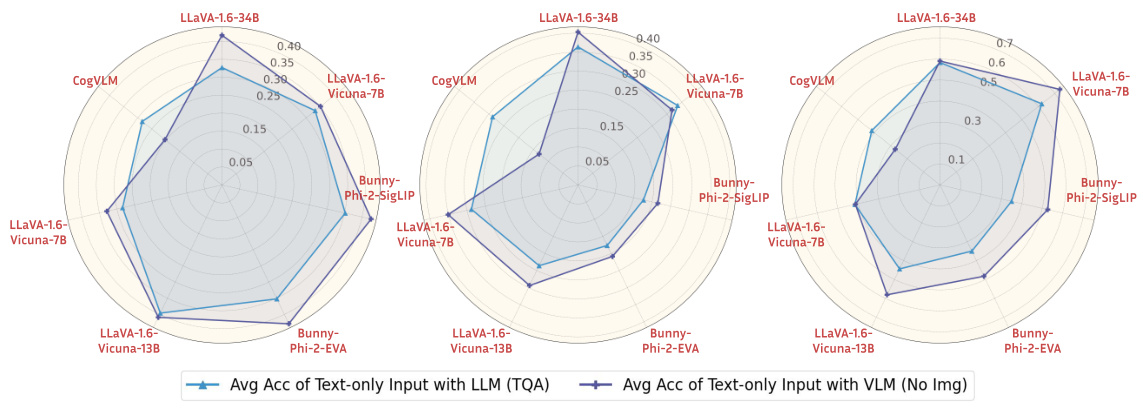

This figure compares the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on three spatial reasoning tasks: Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid. For each task, it shows a spider plot where each vertex represents the average accuracy of a VLM and its corresponding LLM (sharing the same language backbone). The plot highlights that, in most cases, adding visual information (as in VLMs) does not significantly improve performance compared to using only text (as in LLMs). This suggests the limited effectiveness of current vision components in VLMs for spatial reasoning.

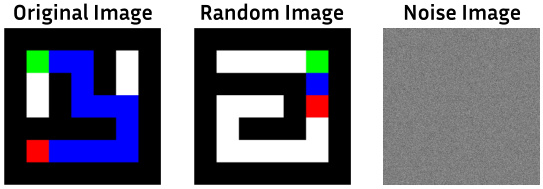

This figure shows three images used in a controlled experiment to test how Vision-Language Models (VLMs) process visual information. The first image is the ‘Original Image’, which is relevant to the textual description provided to the VLM. The second image is a ‘Random Image’, which is also from the dataset but is not related to the textual description. The third image is a ‘Noise Image’, a random collection of pixels with no relation to the textual description or dataset. These three images were used to replace the original image in the VTQA (Vision-text input) setting to isolate the effects of visual information on model performance.

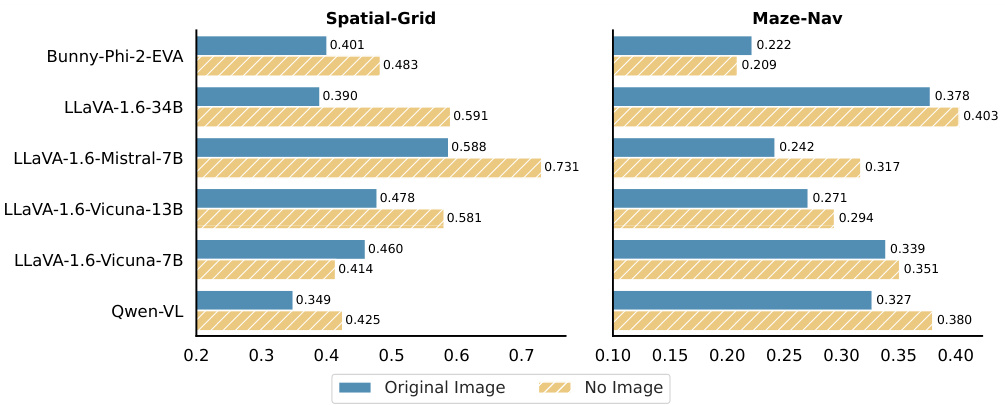

This figure shows the results of experiments where the original image input in the VTQA setting was replaced with no image. The results across three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Grid, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Map) show that removing visual input frequently leads to better performance in several vision-language models (VLMs). This suggests that the model, when textual information is sufficient to answer the questions, may perform better without additional (and potentially conflicting or misleading) visual input.

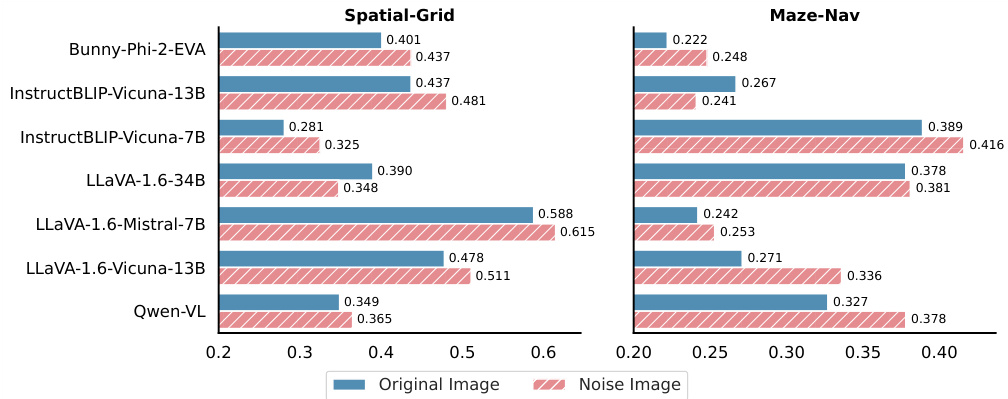

This figure shows the results of replacing the original image with a Gaussian noise image while keeping the original textual description in the VTQA (Vision-text) setting. The experiment tests how the absence of meaningful visual information impacts various Vision-Language Models (VLMs). The results demonstrate that using a noise image instead of the original image actually improves the performance for many models, suggesting a less-than-ideal reliance on visual information in these models’ spatial reasoning capabilities.

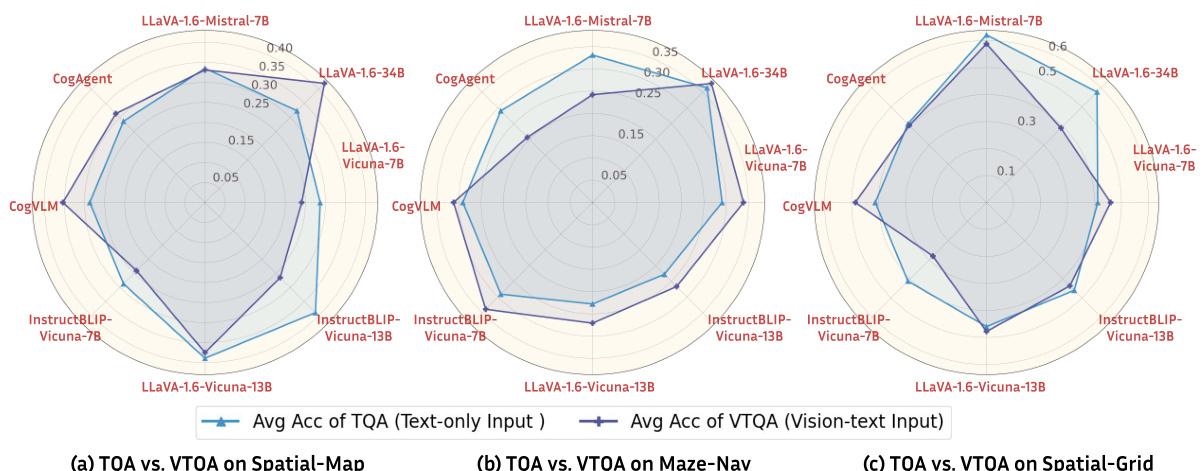

This figure compares the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid). Each point on the radar chart represents a pair of models (an LLM and its corresponding VLM) that share the same language backbone. The figure demonstrates that in most cases, the addition of visual information to the VLM does not improve performance compared to the LLM alone; in fact, performance often decreases.

This figure compares the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) using text-only (TQA) and vision-only (VQA) inputs respectively on three spatial reasoning tasks. Each point in the radar chart represents the average accuracy of a VLM/LLM pair that shares the same language model backbone. The results show that in most cases, the vision-language models do not perform better than the language models even with additional visual information. This suggests the importance of textual input for spatial reasoning in these models.

This figure compares the performance of LLMs and VLMs using only text input. Each vertex represents the average accuracy of a pair of models (LLM, VLM) with the same language backbone. It helps visualize how the inclusion of visual modules in VLMs affects performance when only text is used as input, revealing that multi-modal training improves text-only performance in VLMs.

This figure presents the performance of various LLMs and VLMs on three spatial reasoning tasks: Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid. The accuracy is averaged across all questions for each model. Vision-language models (VLMs) were evaluated using only visual input (VQA). A dashed red line indicates the expected accuracy from random guessing; models performing near or below this line struggled significantly with the tasks. The figure shows that while some models outperformed random guessing, the overall performance on spatial reasoning remains challenging, particularly for the Spatial-Map and Maze-Nav tasks.

This figure illustrates the Spatial-Map task, one of the four tasks in the SpatialEval benchmark. The task involves understanding spatial relationships between objects shown on a map. The figure shows how the task is presented in three different input modalities: Text-only (TQA), Vision-only (VQA), and Vision-Text (VTQA). Each modality provides different information (textual description, image only, or both) to evaluate how well different models (language models and vision-language models) can perform spatial reasoning. The example shows a map with several locations, and example questions that test spatial reasoning ability are included.

This figure illustrates the Spatial-Map task of SpatialEval benchmark. The task involves understanding spatial relationships between multiple locations on a map. Three input modalities are shown: Text-only (TQA), Vision-only (VQA), and Vision-text (VTQA). The Text-only input provides a textual description of the map and object locations. The Vision-only input shows only the map image. The Vision-text input provides both the image and the textual description. The goal is to evaluate how well different language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs) can answer spatial reasoning questions based on each modality.

This figure compares the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on three spatial reasoning tasks: Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid. Each point on the radar chart represents a pair of models, an LLM and its corresponding VLM sharing the same language backbone. The x-axis shows the average accuracy of the LLM on the task (using only text), while the y-axis shows the average accuracy of the VLM on the same task, using only the image (VQA) input modality. The figure demonstrates that in most cases, VLMs do not significantly improve upon the performance of their LLM counterparts when only visual information is provided.

More on tables

This table summarizes the terminology used in the paper to describe the different input modalities used for evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs). It clarifies the meaning of TQA (Text-only Question Answering), VQA (Vision-only Question Answering), and VTQA (Vision-Text Question Answering), specifying which types of input (textual, visual, or both) are provided to the models in each condition.

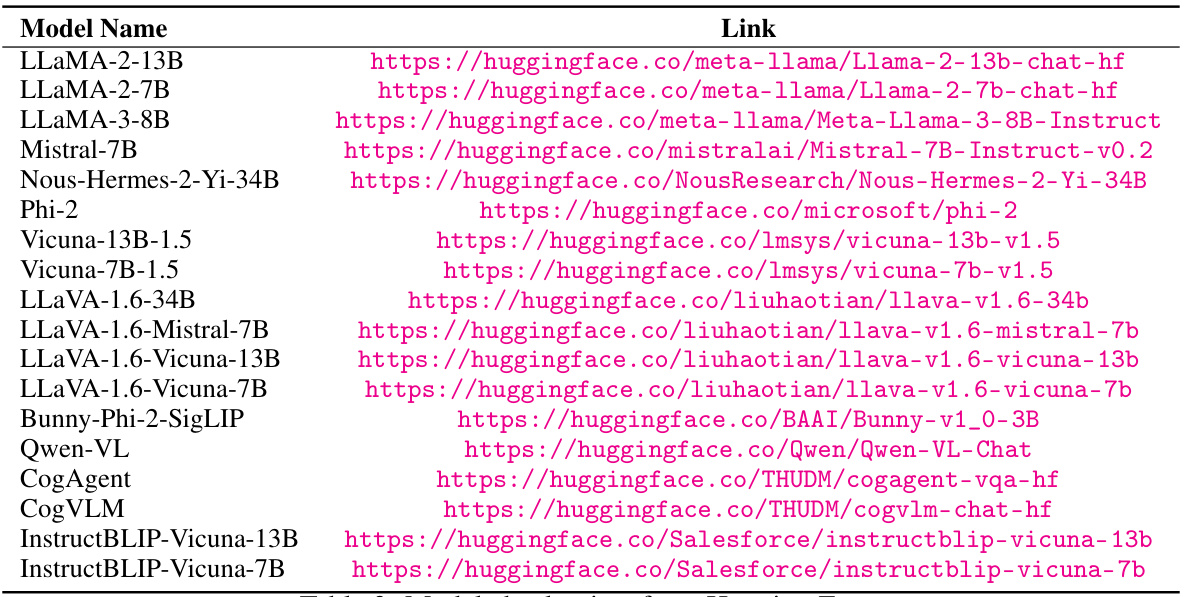

This table lists the model names and their corresponding links to the checkpoints on Hugging Face. It provides the specific locations where the pre-trained model weights can be accessed for the experiments described in the paper. This allows for reproducibility of the results.

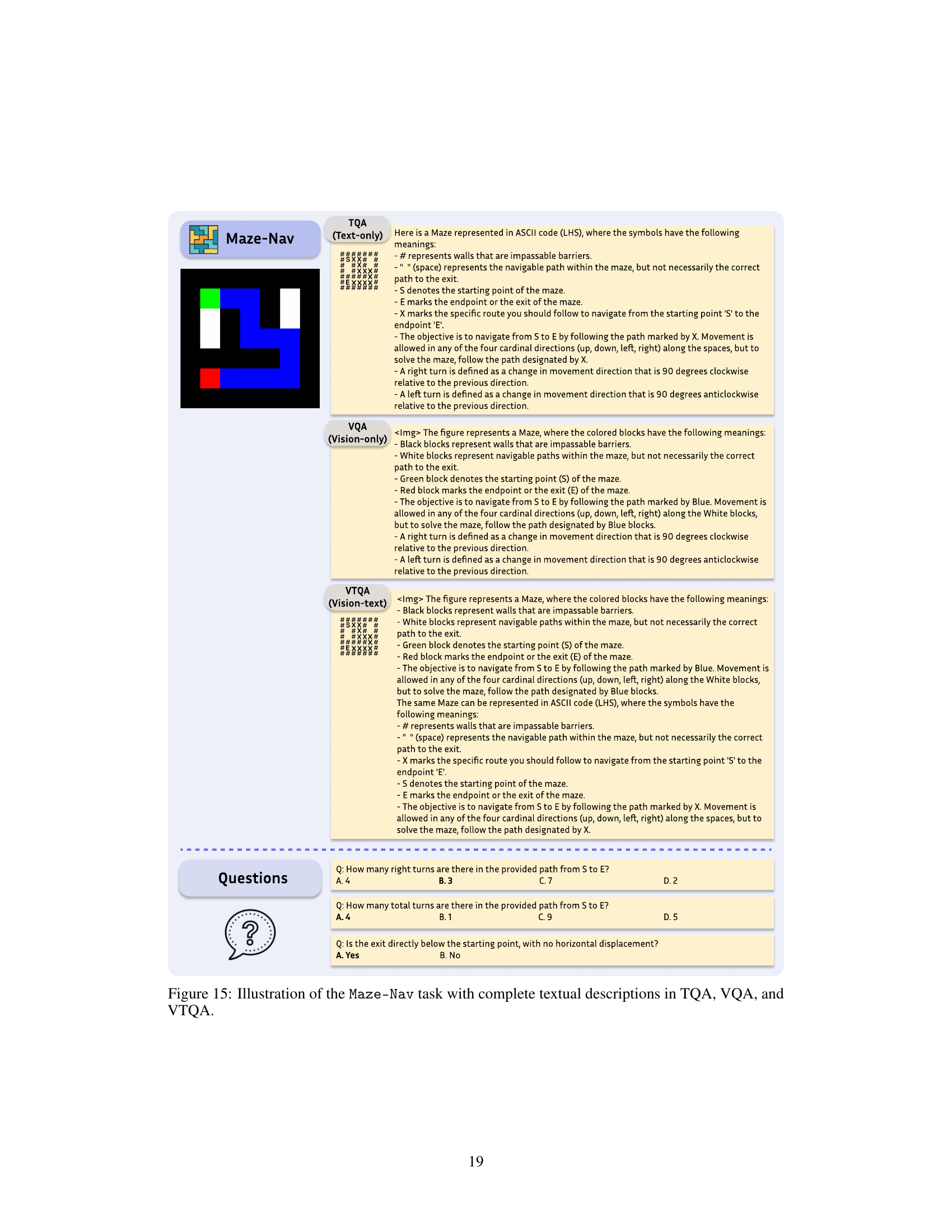

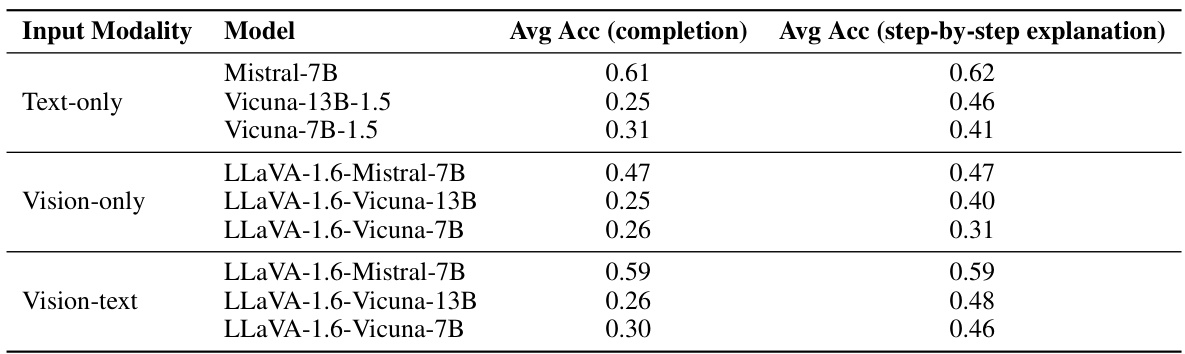

This table compares the average accuracy (Avg Acc) achieved by different models using two different prompting techniques: a simple ‘completion’ prompt and a more detailed ‘step-by-step explanation’ prompt. The results are broken down by input modality (Text-only, Vision-only, Vision-text) to show how the effectiveness of each prompting method varies depending on the type of input provided to the model. The data demonstrates that the step-by-step explanation prompt consistently outperforms the simpler completion prompt across all models and input modalities. This highlights the value of providing more detailed instructions to the model to improve the accuracy and quality of its responses in spatial reasoning tasks.

This table presents the average accuracy (Avg Acc) achieved by different models under two different temperature settings (temperature=1 and temperature=0.2) for decoding strategies. The models are categorized by input modality (text-only, vision-only, and vision-text). Lower temperatures generally lead to more focused and deterministic results, while higher temperatures result in more diverse outputs.

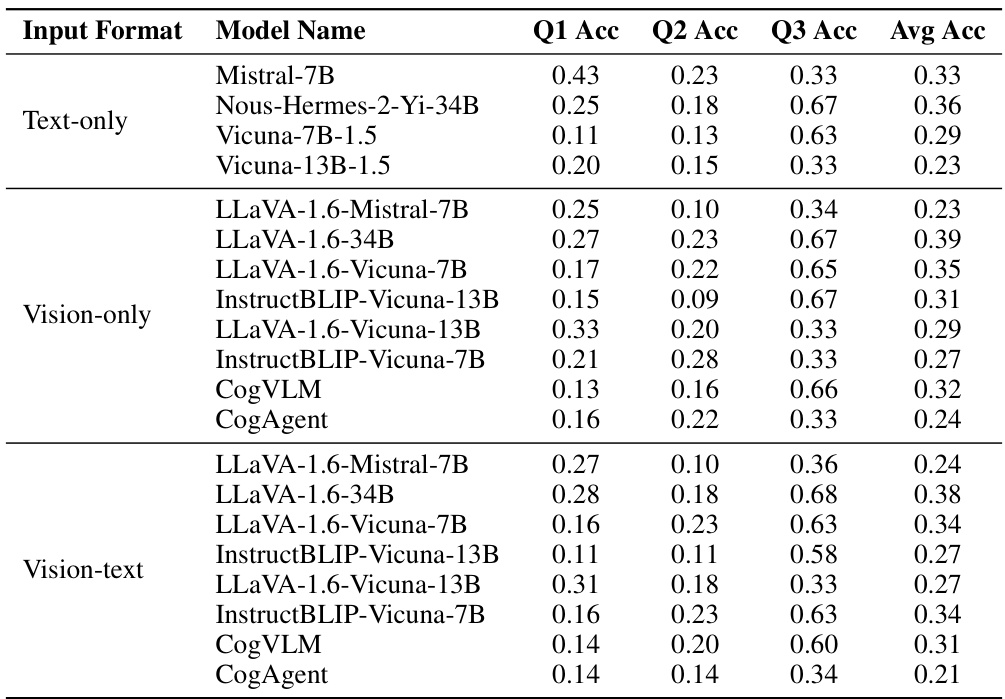

This table presents the average accuracy scores achieved by various LLMs and VLMs on the Spatial-Real task, categorized by input modality (Text-only, Vision-only, and Vision-text). The results demonstrate consistent trends observed in synthetic tasks, showing that text-only input often outperforms vision-only input, and the inclusion of textual descriptions alongside visual data significantly enhances the performance of vision-language models, even when there is significant redundancy.

This table presents the detailed performance results for proprietary models (GPT-4, GPT-4V, GPT-40, Gemini Pro 1.0, and Claude 3 Opus) on three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid). It breaks down the accuracy for each model across three input modalities: Text-only (TQA), Vision-only (VQA), and Vision-text (VTQA). This allows for a direct comparison of the models’ performance under different input conditions and highlights how well these models leverage textual and visual information for spatial reasoning.

This table presents the detailed performance of proprietary models (Claude 3 Opus, Gemini Pro 1.0, GPT-40, GPT-4V, and GPT-4) across three different input modalities (Text-only, Vision-only, Vision-text) on three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, Spatial-Grid). It shows the accuracy achieved by each model on each task and input type, offering a granular view of the models’ strengths and weaknesses in handling different kinds of spatial reasoning challenges and input modalities.

This table presents the detailed performance of proprietary models (GPT-4, GPT-4V, GPT-40, Gemini Pro 1.0, and Claude 3 Opus) on three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid) across different input modalities (text-only, vision-only, and vision-text). It shows the accuracy for each model in each task and input type, allowing for a detailed comparison of the performance across different models and input formats.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of proprietary models (Claude 3 Opus, Gemini Pro 1.0, GPT-40, GPT-4V, and GPT-4) across three spatial reasoning tasks (Spatial-Map, Maze-Nav, and Spatial-Grid) and three input modalities (Text-only, Vision-only, and Vision-text). It shows the accuracy achieved by each model on each task and input type, offering a granular view of the models’ capabilities in handling different types of spatial information.

Full paper#