↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), a popular approach for implementing neural networks on quantum hardware, suffer from the limitations of high circuit depth and the substantial number of parameters needed, impacting performance and increasing error accumulation. Existing methods for gradient evaluations also face significant measurement overhead. These challenges hinder the feasibility of deploying VQAs on near-term quantum devices.

This research introduces Quantum Deep Equilibrium Models (QDEQs), a novel framework that addresses these limitations. QDEQs leverage deep equilibrium models (DEQs), which effectively mimic infinitely deep networks with significantly fewer parameters. By employing a root-solving method to find fixed points instead of explicitly evaluating deep circuits, QDEQs achieve comparable or better performance with shallower quantum circuits. This translates to fewer measurements, reduced error accumulation, and improved training efficiency, showcasing the potential of QDEQs for near-term quantum machine learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to training quantum machine learning (QML) models, addressing the challenge of high circuit depth in existing methods. It proposes Quantum Deep Equilibrium Models (QDEQs), a training paradigm that uses deep equilibrium models to learn parameters efficiently, resulting in shallower and more practical circuits for near-term quantum computers. This advancement could significantly impact various applications of QML and pave the way for new research directions in developing more efficient and robust QML algorithms.

Visual Insights#

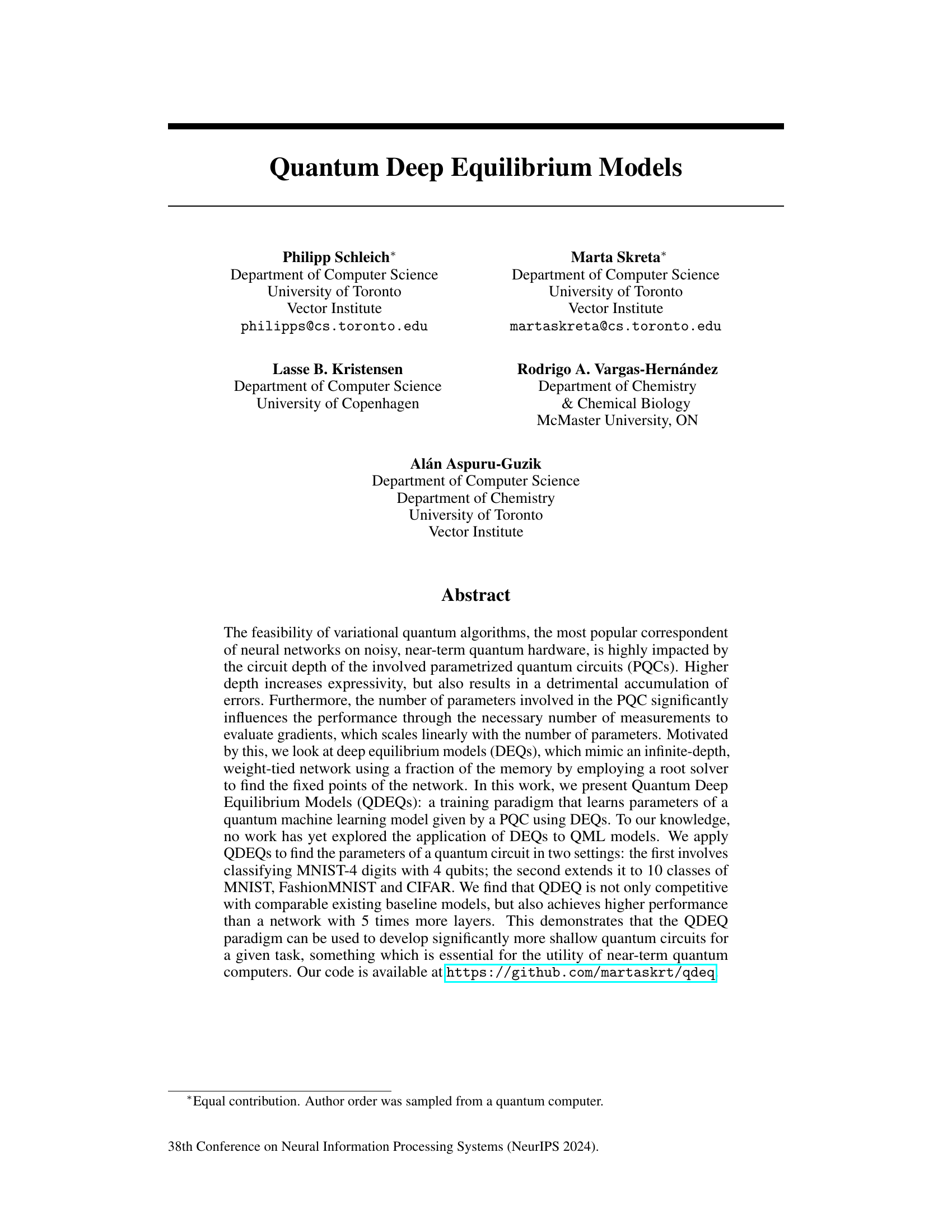

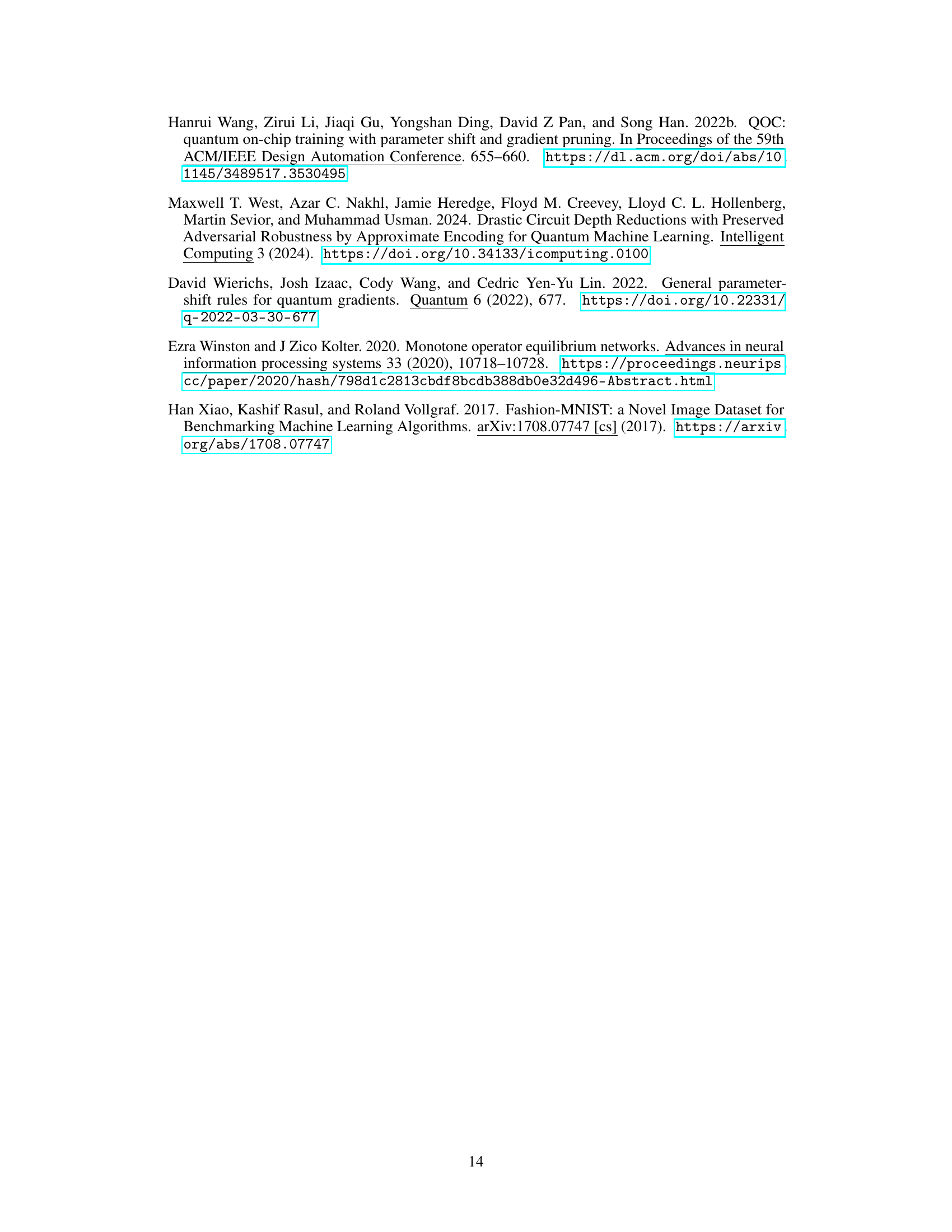

This figure illustrates the core concept of a Quantum Deep Equilibrium Model (QDEQ). The input data is fed into a root-finding algorithm (like Newton’s method or Broyden’s method) that iteratively refines an internal state ‘z’ until it converges to a fixed point. This fixed point is then used to compute the model’s output. The root-finding process implicitly represents an infinitely deep network, while actually using significantly less computational resources than training an explicit deep network. The core function ‘fo’ is a quantum model function, computed by a parametrized quantum circuit (PQC), which takes the input ‘x’ and the internal state ‘z’ as parameters to create a quantum state. A measurement on this quantum state, guided by a Hermitian operator ‘M’, yields the output of the quantum model function.

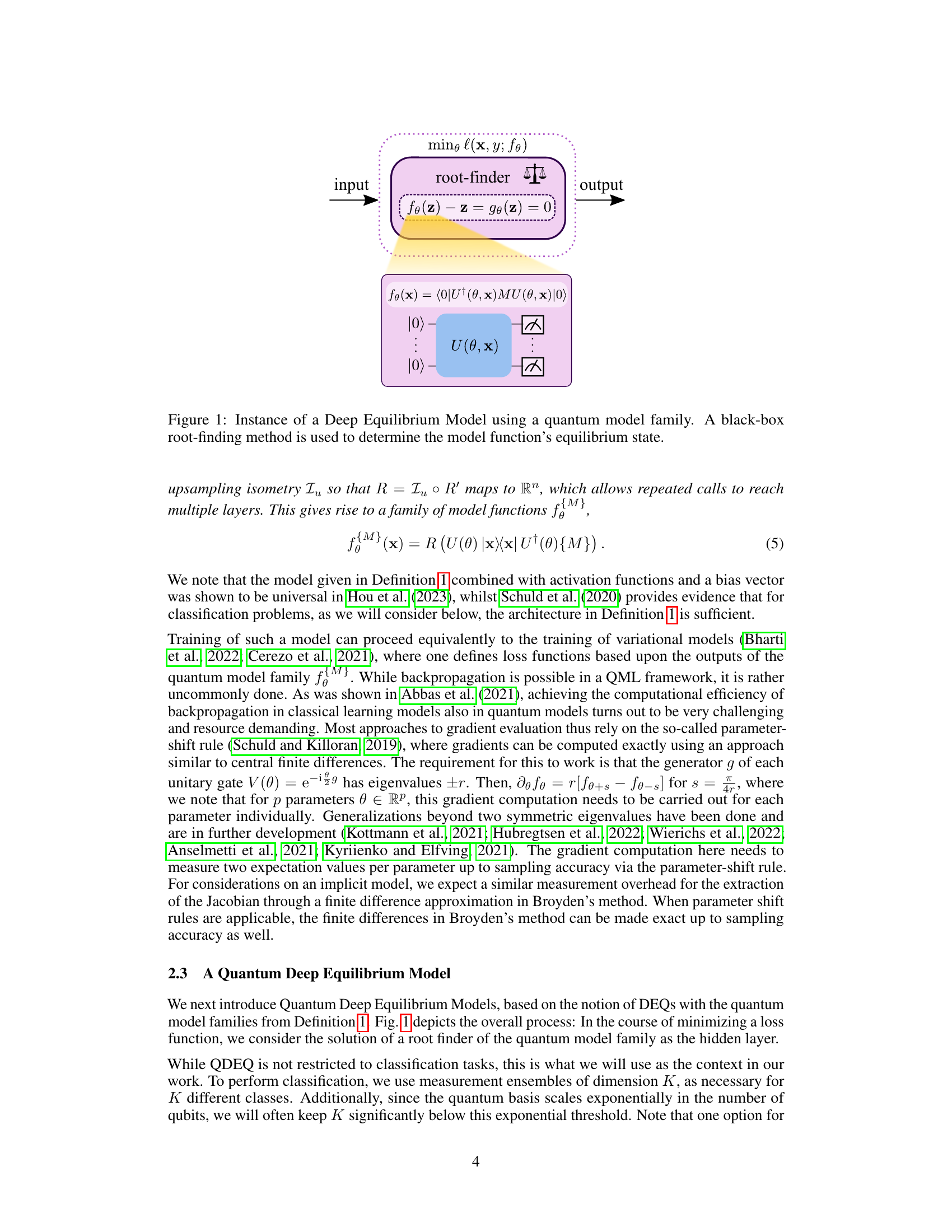

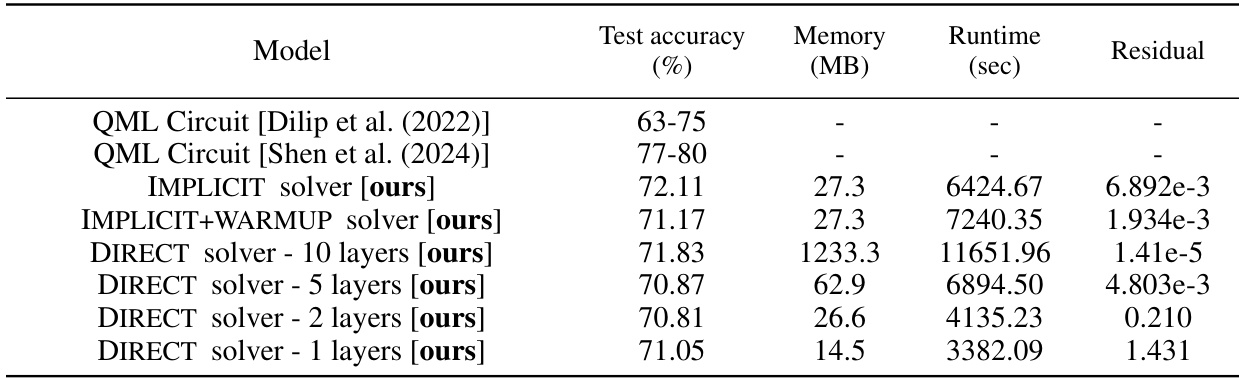

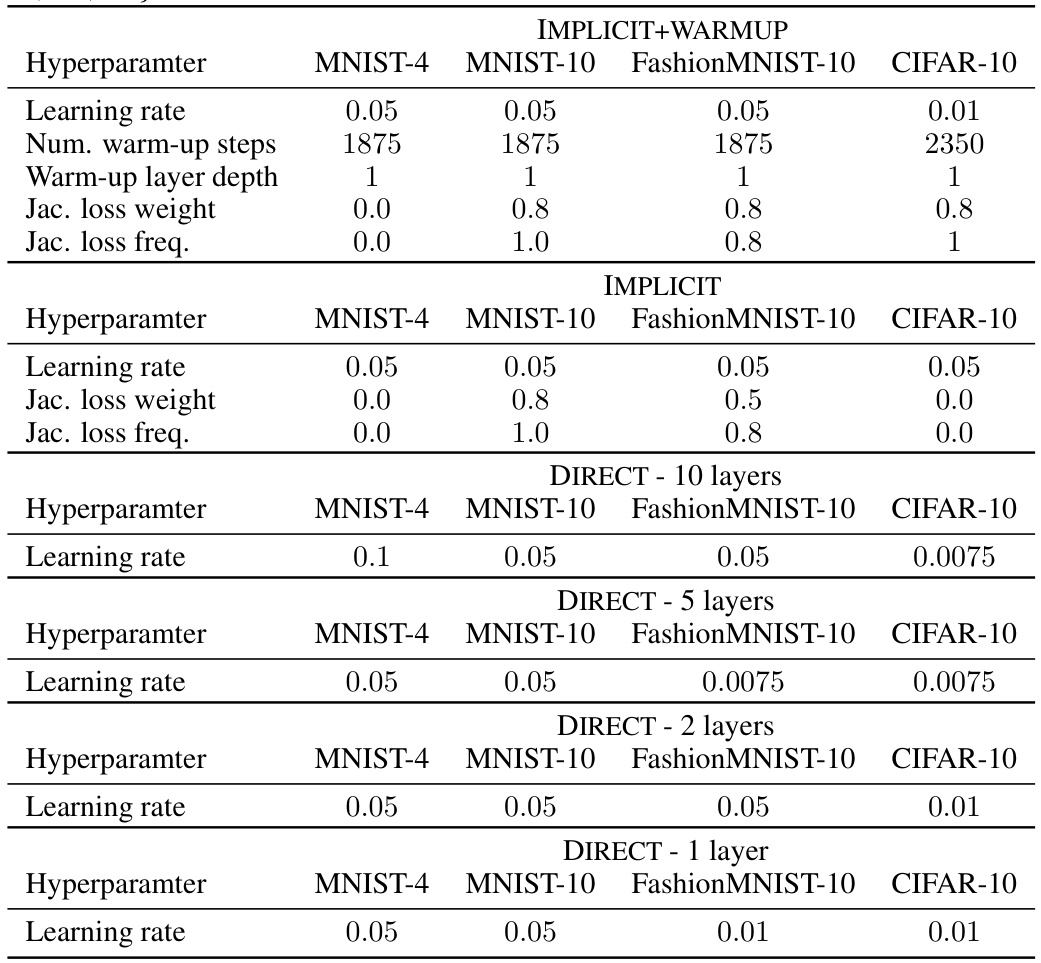

This table presents a comparison of different model architectures on the MNIST-4 dataset. It shows the test accuracy, memory usage (in MB), runtime (in seconds), and residual error for various models, including the IMPLICIT, IMPLICIT+WARMUP, and DIRECT solvers with different numbers of layers. Results are provided separately for models using amplitude and angle encoding schemes. The table allows for evaluating the efficiency and performance tradeoffs of different approaches.

In-depth insights#

QDEQ: A New Model#

The heading “QDEQ: A New Model” suggests a novel approach to quantum machine learning (QML). QDEQ likely stands for Quantum Deep Equilibrium Model, representing a hybrid classical-quantum algorithm that leverages the efficiency of deep equilibrium networks. This approach probably addresses the challenges of training deep parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) by employing a fixed-point iteration method instead of explicitly evaluating the circuit at every training step. This allows for potentially shallower circuits, mitigating the accumulation of noise, which is especially relevant for near-term quantum hardware. The novelty likely lies in applying the DEQ framework to QML models, which may provide performance gains and reduced resource requirements. The model’s effectiveness would be evaluated through experiments on classification tasks, showcasing its advantage in terms of accuracy, circuit depth, and memory usage relative to existing baselines. Ultimately, “QDEQ: A New Model” hints at a significant contribution toward making QML more practical and efficient.

Quantum DEQ#

The concept of “Quantum DEQ” (Quantum Deep Equilibrium) models presents a novel approach to training quantum machine learning (QML) models. It leverages the efficiency of classical DEQs, which avoid the computational cost of explicitly iterating through many layers by converging to a fixed point, adapting this to the context of quantum circuits. This is particularly beneficial for near-term quantum computers with limited circuit depth and high error accumulation. QDEQ aims to achieve competitive performance with shallower circuits than traditional variational methods, requiring fewer measurements and potentially reducing the impact of noise. The approach uses a root-finding method to solve for the fixed point of the quantum network, effectively mimicking an infinitely deep network with limited resources. A key advantage is the potential for improved trainability due to the modified loss landscape, avoiding issues like barren plateaus that hinder training deep quantum neural networks. However, further investigation is needed to fully understand the impact of quantum noise on QDEQ’s performance and its scalability to more complex problems.

Implicit Diff#

Implicit differentiation, in the context of training deep equilibrium models or variational quantum circuits, offers a computationally efficient approach to calculating gradients. Unlike explicit methods that iterate through layers, implicit differentiation leverages the implicit function theorem to solve for gradients indirectly. This is particularly useful for infinitely deep or very deep networks where explicit computation would be extremely expensive and prone to numerical instability. In variational quantum circuits, the reduction in computational cost can be significant, enabling the training of deeper and more expressive models using near-term quantum hardware which have limitations in the number of measurements allowed. However, the implementation of implicit differentiation may involve solving non-linear equations, which can add complexity and potentially reduce the method’s robustness. Furthermore, there is a trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, as the solution of the nonlinear system of equations might only be approximate. The overall success of implicit differentiation hinges upon the choice of appropriate root-finding algorithms and regularization techniques to ensure convergence and stability. Despite the challenges, this method offers promising avenues for improving the scalability and efficiency of training complex deep models, both classical and quantum.

MNIST Results#

The MNIST results section would likely detail the performance of Quantum Deep Equilibrium Models (QDEQs) on the MNIST handwritten digit classification task. A key aspect would be comparing QDEQ’s accuracy against various baseline models, including standard deep neural networks and other variational quantum algorithms. Crucially, the analysis would likely focus on the trade-off between model depth (circuit depth in QDEQs) and accuracy. The results should demonstrate QDEQ’s ability to achieve competitive accuracy with significantly shallower circuits than traditional methods, highlighting its efficiency for near-term quantum hardware. Another important point would be the analysis of resource requirements, such as the number of measurements needed for gradient calculations, demonstrating QDEQ’s advantage in terms of efficiency. The findings might reveal QDEQ’s robustness to noise and potential limitations compared to more complex architectures, providing valuable insights into the practical applicability of QDEQs for real-world quantum machine learning tasks. Discussion of different encoding schemes (e.g., amplitude or angle encoding) and their impact on performance would also be a significant part of this section.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this Quantum Deep Equilibrium Model (QDEQ) study are multifaceted. Improving the theoretical understanding of QDEQ’s behavior, especially regarding the impact of noise and the conditions for guaranteed convergence, is crucial. Investigating the application of QDEQ to more complex quantum models and datasets, potentially including those involving time-series data or more intricate relationships, is also a priority. Furthermore, exploring the practical implications of the method on near-term quantum hardware, including resource allocation and error mitigation techniques, warrants exploration. Finally, comparing QDEQ to other advanced implicit methods in the field of quantum machine learning is essential to establish its true potential and competitive advantage.

More visual insights#

More on figures

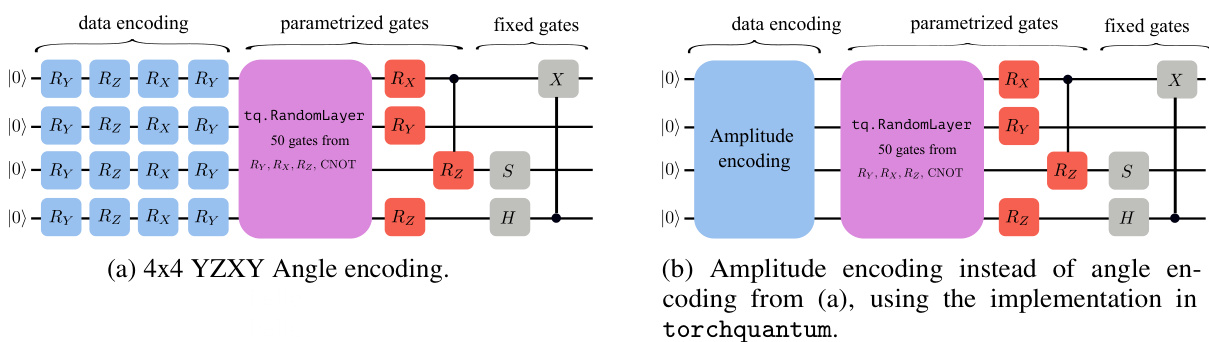

This figure shows two variations of a quantum circuit used for image classification. The circuit consists of four qubits, with the input being processed through parameterized quantum gates and finally measured for classification. Variation (a) uses angle encoding and variation (b) uses amplitude encoding. The ‘RandomLayer’ represents a set of gates randomly selected from a defined set of two-qubit gates (CNOT gates included).

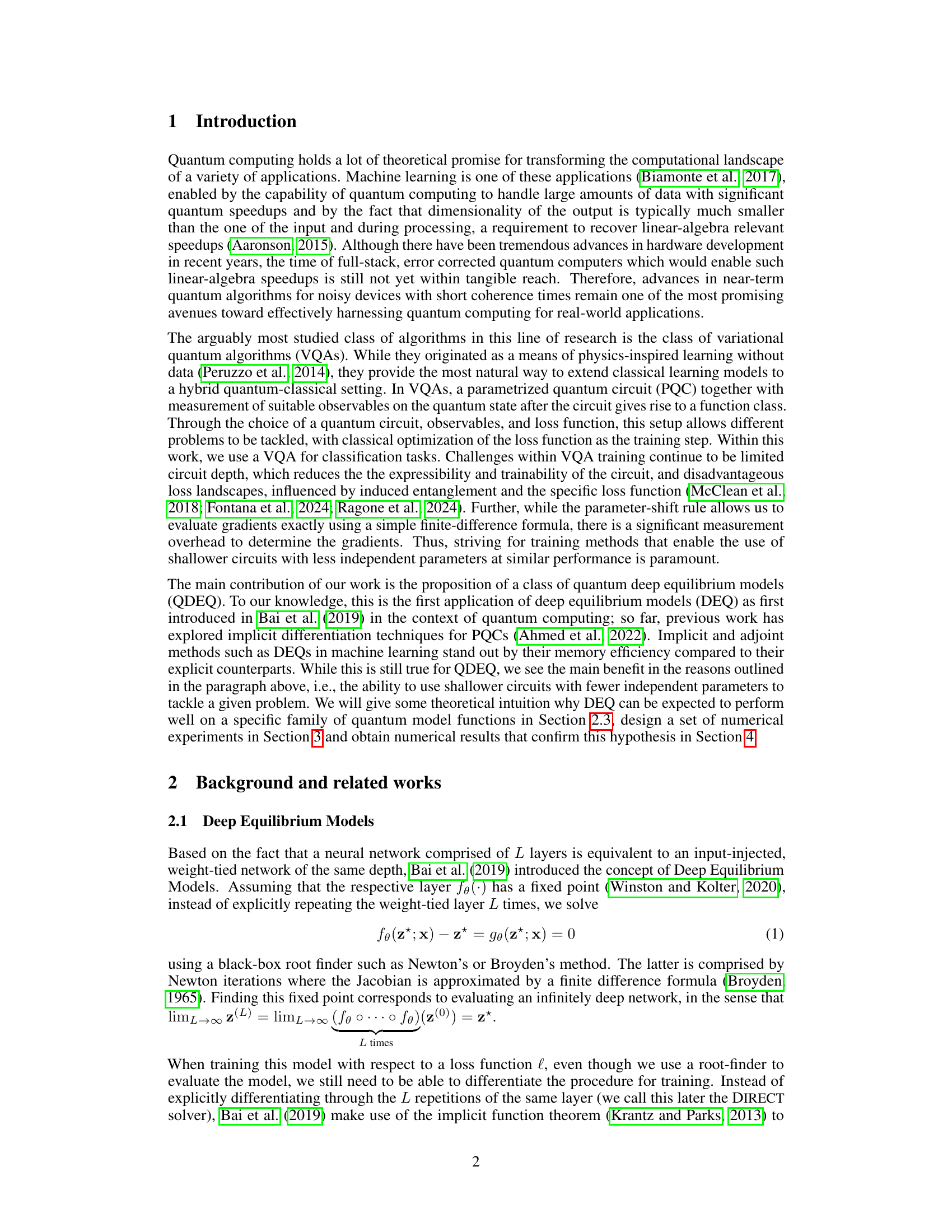

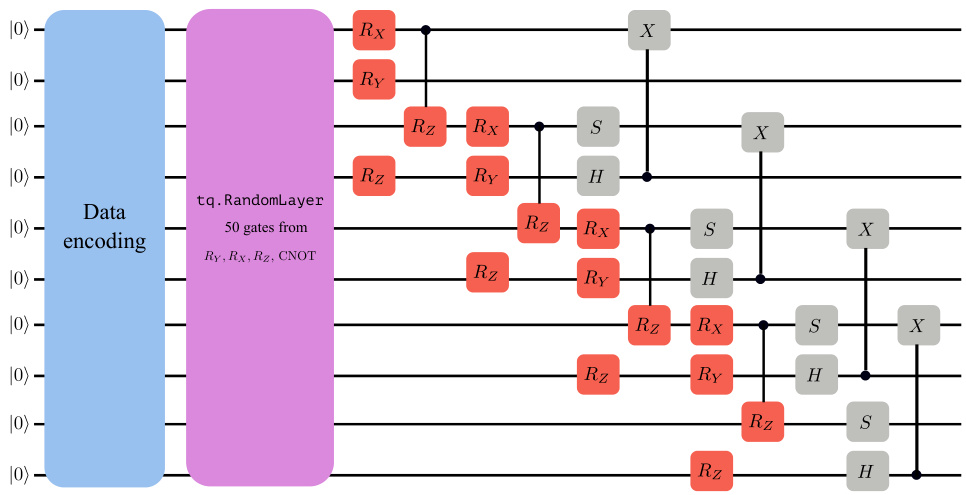

This figure shows the quantum circuit used for image classification in the paper. It is based on the work of Wang et al. (2022a) and consists of a data encoding section (blue), a random layer with parameterized gates (purple and red), and a measurement section (grey). The random layer uses CNOT gates and is a four-qubit circuit, which can be extended for more classes.

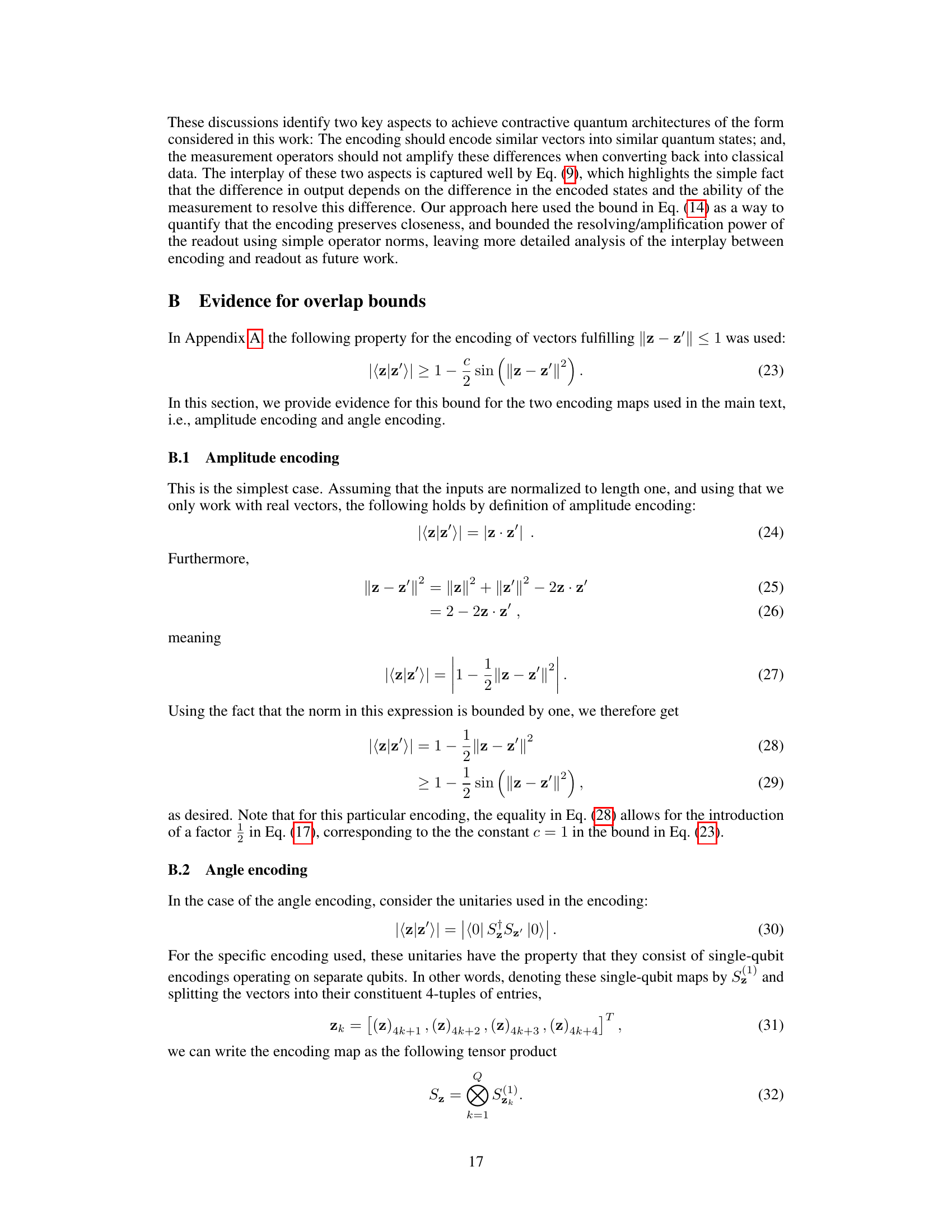

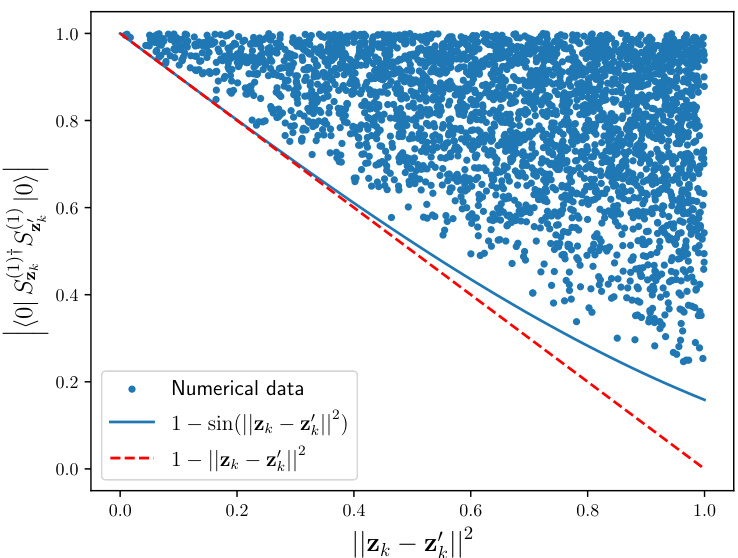

This figure shows the relationship between the overlap of single-qubit encodings of two random vectors (⟨0|Sz†k Sz′k|0⟩) and the squared Euclidean distance between the vectors (||Zk−Zk′||2). The plot demonstrates that the overlap is always greater than 1−sin(||Zk−Zk′||2), supporting the claim of a bound used in the paper’s theoretical analysis of quantum model contractiveness. The plot displays 3000 data points obtained through numerical simulation.

More on tables

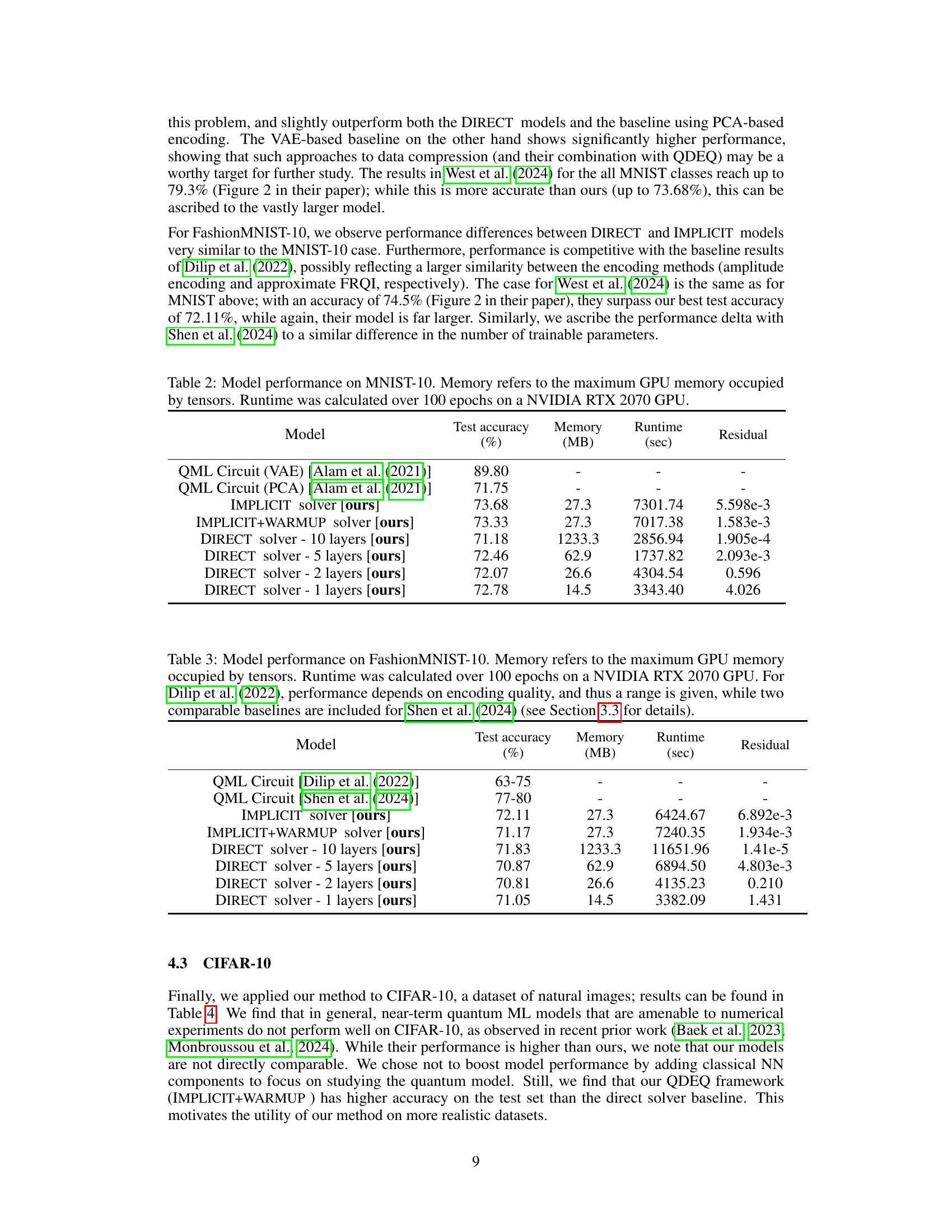

This table presents the performance of different models on the MNIST-10 dataset. The models include the proposed Implicit and Implicit+Warmup QDEQ models, along with several direct solver models of varying depths (number of layers). For comparison, results from two baseline QML circuits using VAE and PCA based encodings are also shown. The table provides test accuracy, GPU memory usage, runtime, and a residual value for each model.

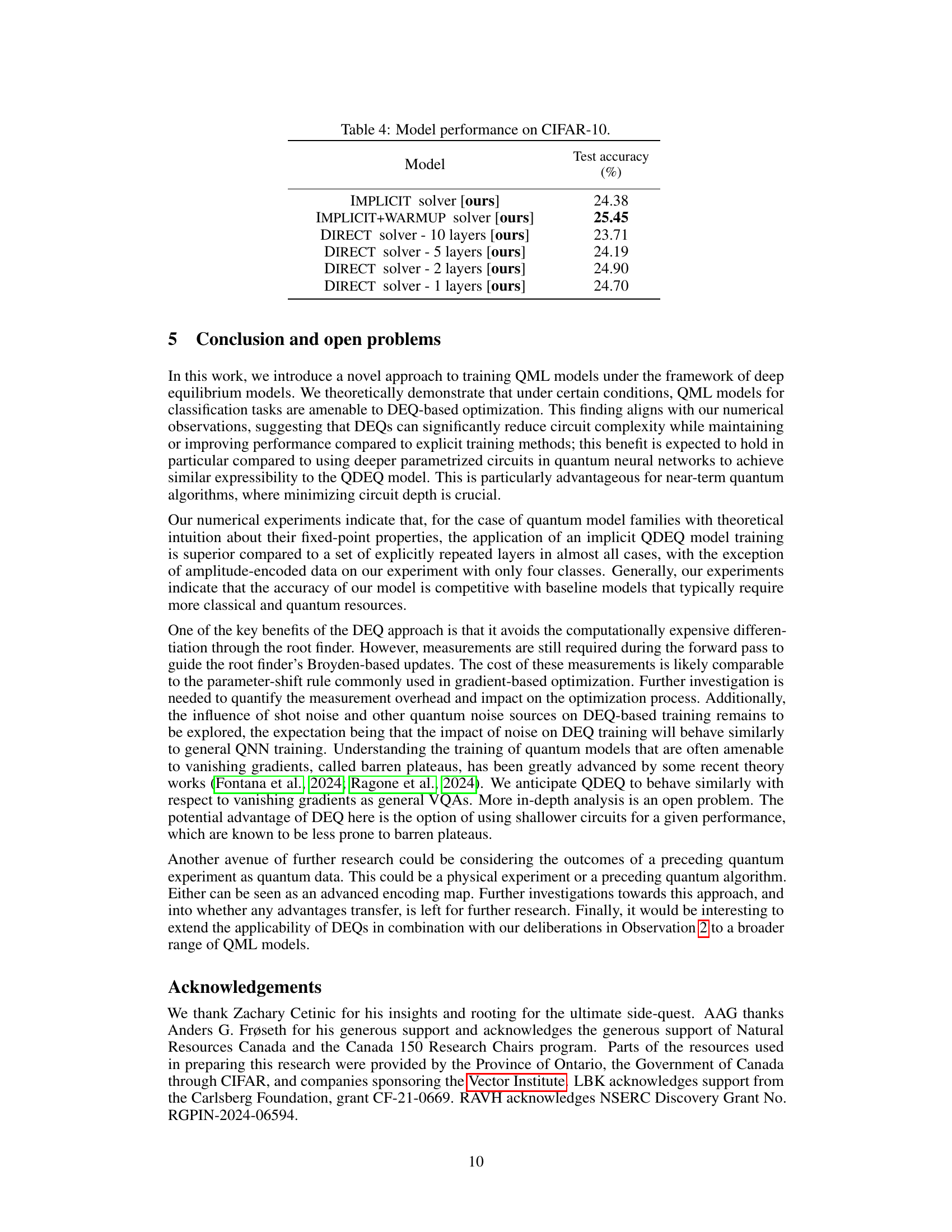

This table presents the performance of different models on the FashionMNIST-10 dataset. The models include the proposed Quantum Deep Equilibrium Models (QDEQ) using different approaches (IMPLICIT, IMPLICIT+WARMUP) and standard weight-tied networks (DIRECT solver) with varying depths. Also included are results from comparable methods in other published work for comparison purposes. The metrics reported are test accuracy, maximum GPU memory usage, runtime, and residual. Note that results for some prior work show a range due to variations in encoding quality.

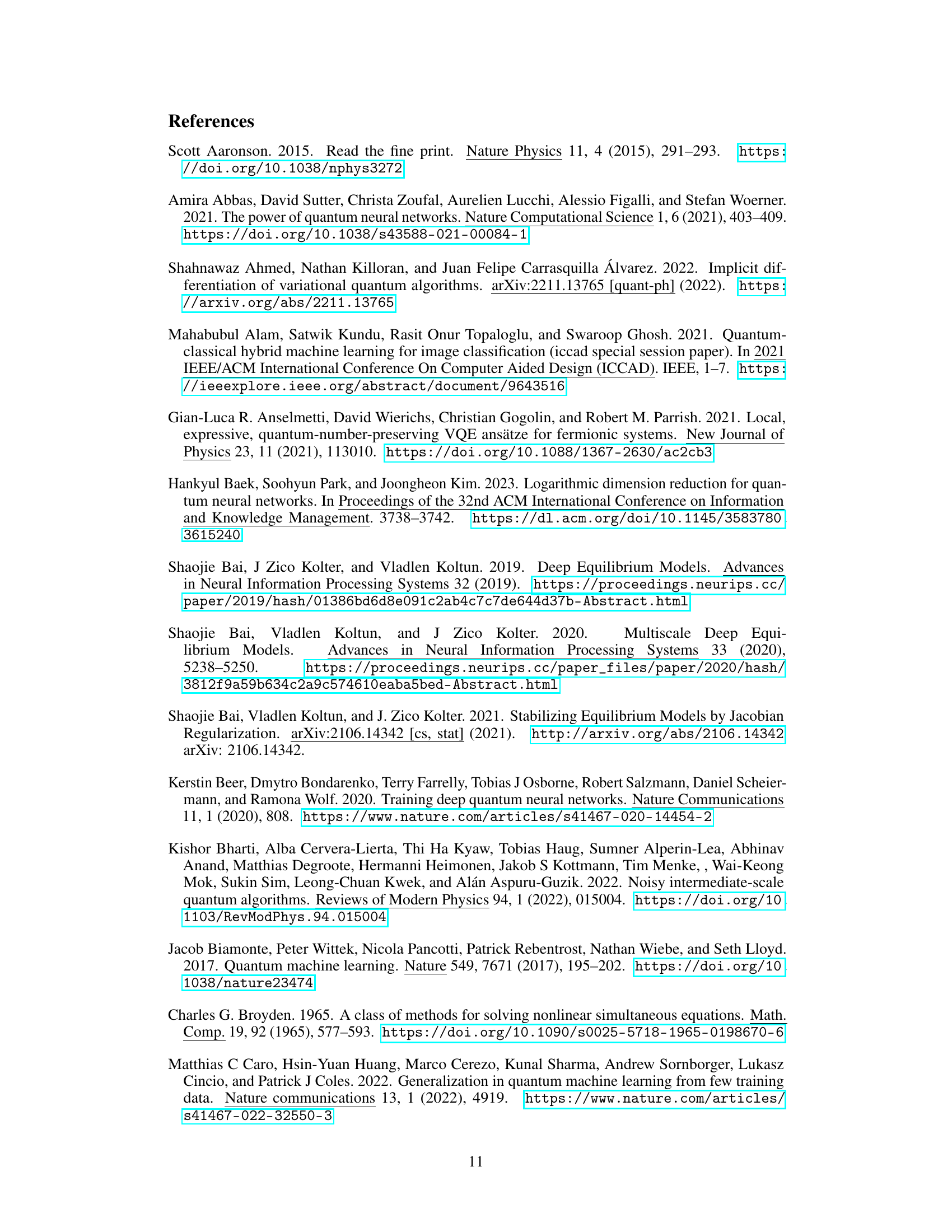

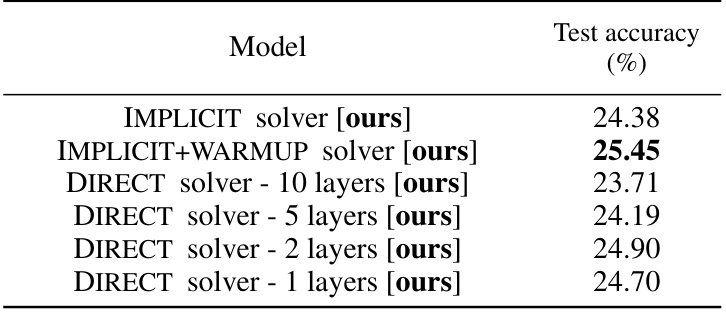

This table presents the test accuracy results for different models on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The models include the proposed IMPLICIT and IMPLICIT+WARMUP solvers, as well as several DIRECT solvers with varying numbers of layers. The table shows the test accuracy achieved by each model, allowing for a comparison of performance across different model architectures and training paradigms. The IMPLICIT+WARMUP model shows the best performance.

This table shows the performance of different models on the MNIST-4 dataset. It compares the proposed QDEQ framework with several baselines (a standard QML circuit from Wang et al. (2022b) and various weight-tied networks with different depths). The results are presented separately for amplitude and angle encoding methods. For each model, the test accuracy, memory usage (in MB), runtime (in seconds), and residual error are reported.

Full paper#