↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

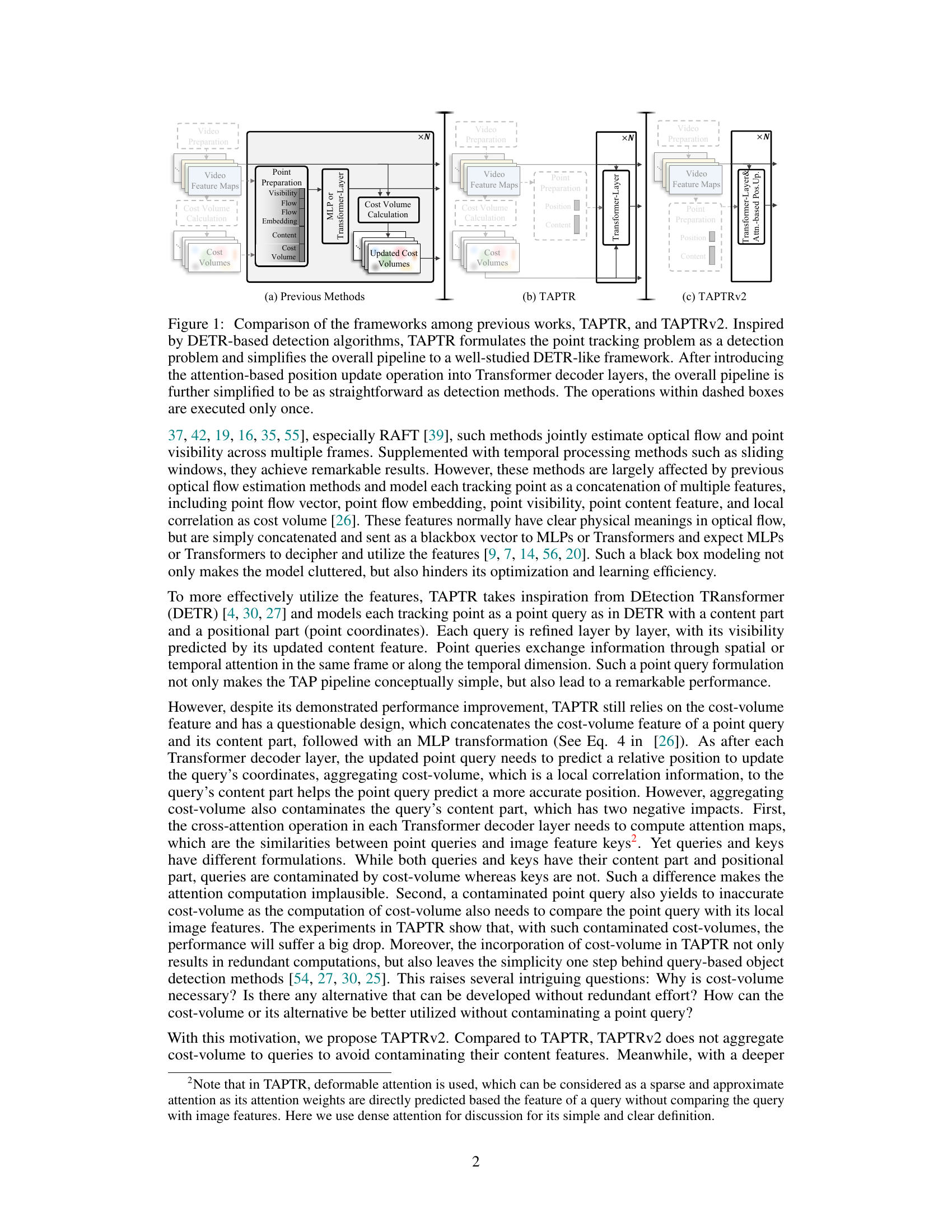

Tracking any point (TAP) in videos is challenging, particularly in dealing with occlusions and long sequences. Existing methods often concatenate various features (point flow, visibility, content), leading to cluttered models and reduced learning efficiency. TAPTR improved this by modeling each tracking point as a point query, simplifying the pipeline but still relying on cost volume, which can contaminate point query content.

TAPTRv2 solves this by proposing an attention-based position update (APU). Instead of using cost-volume, APU uses key-aware deformable attention to combine sampling positions, thereby predicting query position. This not only eliminates extra cost-volume computation but also results in substantial performance improvements. APU effectively mitigates the domain gap, leading to better generalization across various datasets. The experiments demonstrate TAPTRv2’s superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods on multiple challenging datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in visual tracking and computer vision because it addresses a key challenge in point tracking—the contamination of point queries—and proposes a novel solution with significant performance improvements. It also showcases the effectiveness of attention mechanisms in handling the complexities of visual tracking. This opens up new avenues for research in improving the efficiency and accuracy of visual tracking algorithms.

Visual Insights#

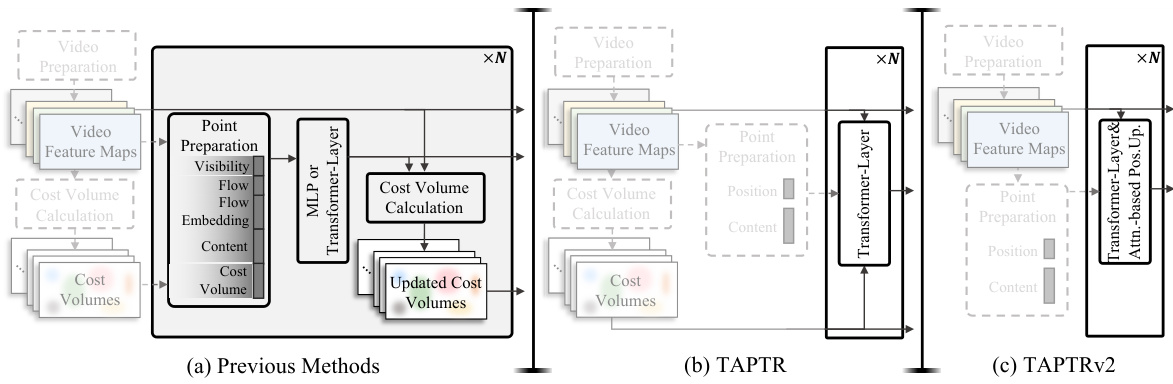

This figure compares three different approaches to the Tracking Any Point (TAP) task. (a) shows previous methods, which involve a complex pipeline including video preparation, feature extraction, cost volume calculation, and various processing steps before tracking. (b) illustrates TAPTR, which simplifies the process by using a DETR-like framework. Each tracking point is treated as a point query. The pipeline is simplified into video preparation, point preparation, cost volume calculation and a transformer layer for final position update. (c) presents TAPTRv2, which further refines the TAPTR approach by removing the cost volume and integrating an attention-based position update mechanism. This results in an even more streamlined and efficient pipeline.

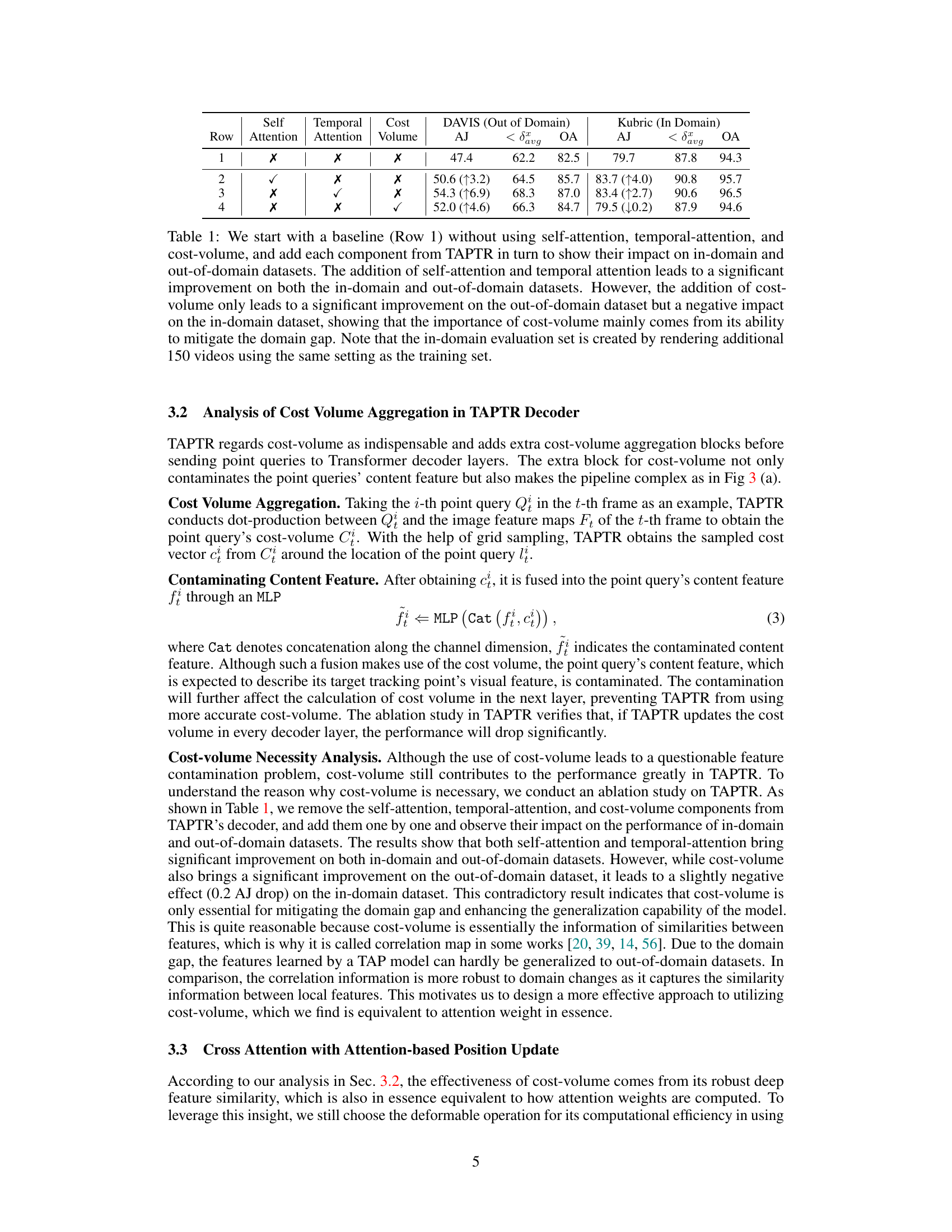

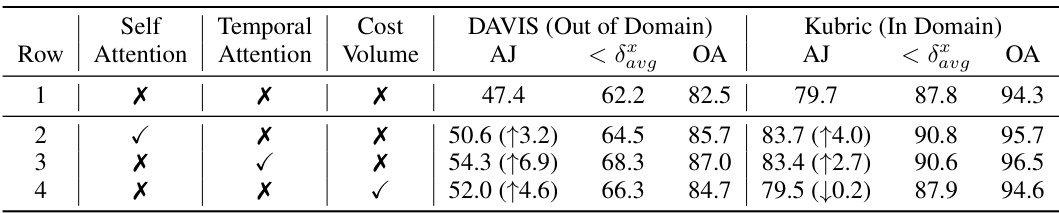

This table presents an ablation study on the components of TAPTR (self-attention, temporal attention, and cost volume) to analyze their individual contributions to the model’s performance on in-domain and out-of-domain datasets. It shows that self-attention and temporal attention significantly improve performance in both domains, while the cost volume’s impact is more nuanced, improving out-of-domain results but negatively affecting in-domain performance, suggesting its primary role in domain generalization.

In-depth insights#

TAPTRv2 Overview#

TAPTRv2, as a refined version of TAPTR, presents a streamlined approach to tracking any point (TAP) in videos. Building upon the DETR framework, it leverages the well-established concept of point queries, simplifying the pipeline and making it more efficient. Unlike its predecessor, TAPTRv2 addresses the issue of cost-volume contamination, a crucial problem in TAPTR that negatively impacted visibility prediction and computation. The core innovation lies in the attention-based position update (APU) operation, which uses key-aware deformable attention to combine corresponding deformable sampling positions. This replaces the cost volume, resulting in a more accurate and efficient approach. This design is founded on the observation that local attention and cost-volume are essentially the same—both relying on dot-products. By removing cost-volume and introducing APU, TAPTRv2 achieves superior performance, surpassing TAPTR and setting a new state-of-the-art on various TAP benchmarks. The streamlined architecture and efficient design represent significant advancements in TAP technology.

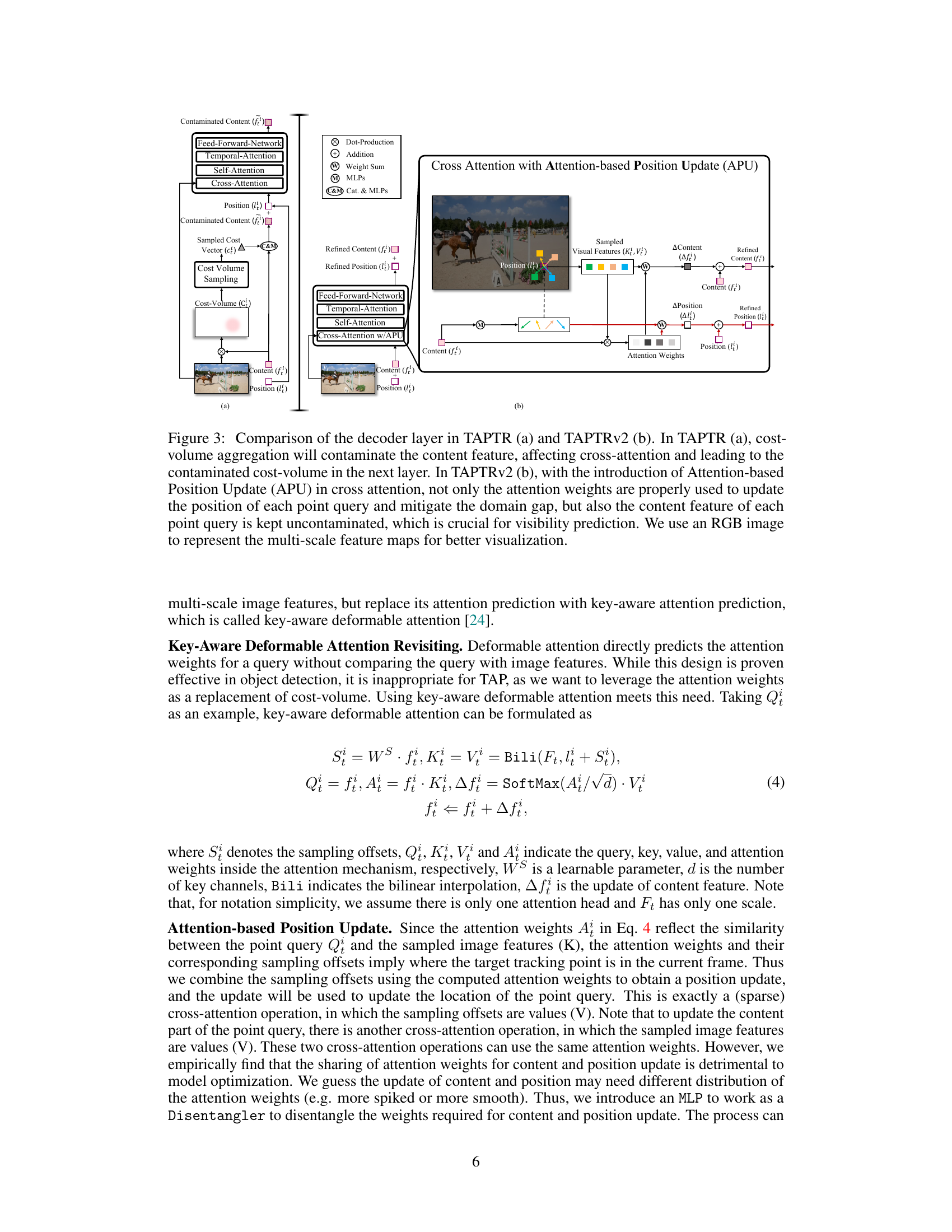

APU Mechanism#

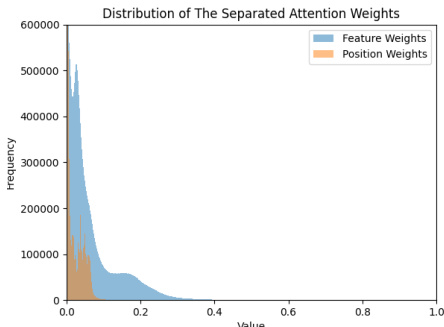

The core of the proposed TAPTRv2 model is its novel Attention-based Position Update (APU) mechanism. APU cleverly replaces the traditional cost volume method used in TAPTR, addressing the issue of feature contamination. Instead of relying on a computationally expensive and potentially inaccurate cost volume, APU leverages the power of key-aware deformable attention. This allows the model to directly compute attention weights by comparing a query with image features, resulting in a more accurate and precise position update. The key innovation is the disentangling of attention weights for content and position updates. This design choice prevents the contamination of the query’s content feature, ultimately improving visibility prediction accuracy. The APU mechanism is elegantly integrated into the Transformer decoder layers, improving efficiency by eliminating the cost volume computation altogether. The use of key-aware deformable attention enhances the efficiency and precision of the APU, making TAPTRv2 both effective and computationally efficient. The experimental results validate that the APU not only eliminates an unnecessary computational burden but also significantly improves the overall tracking performance, surpassing the state-of-the-art on various challenging datasets.

Cost Volume Issue#

The paper identifies a critical flaw in the original TAPTR model, specifically its reliance on cost volume. Cost volume, while initially used to improve position prediction accuracy, introduces a contamination of the point query’s content feature. This contamination negatively affects both visibility prediction and cost volume computation itself, creating a feedback loop of inaccuracies. The authors argue that this reliance on cost volume is unnecessary and inefficient. The core problem stems from the concatenation of cost-volume features with the query’s content, which disrupts the query’s original features and compromises the attention mechanisms in the Transformer decoder. By removing cost volume, the query remains cleaner, leading to significant improvements in overall performance. This highlights the importance of careful feature integration in transformer-based architectures and the potential pitfalls of relying on intermediate steps that can introduce noise and unnecessary complexity.

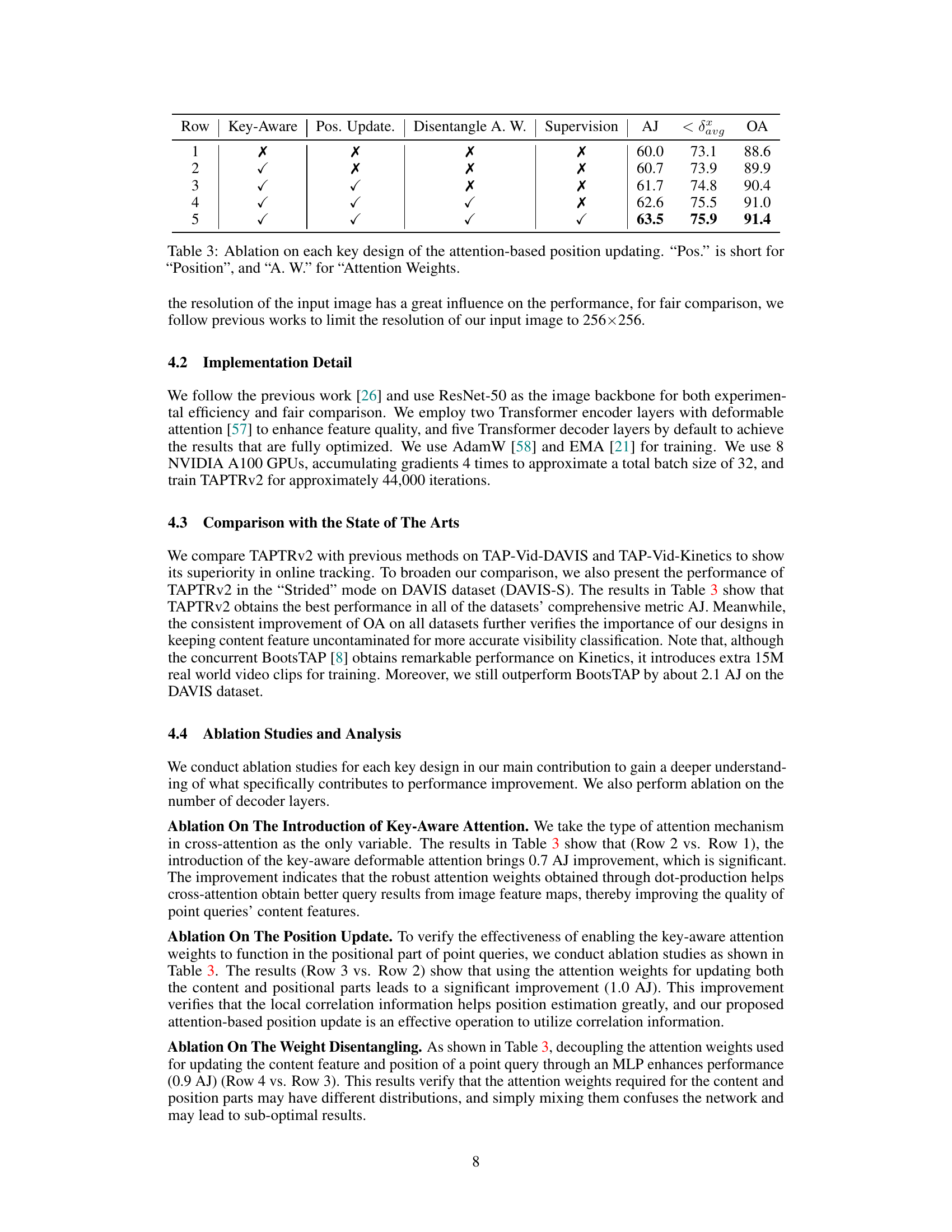

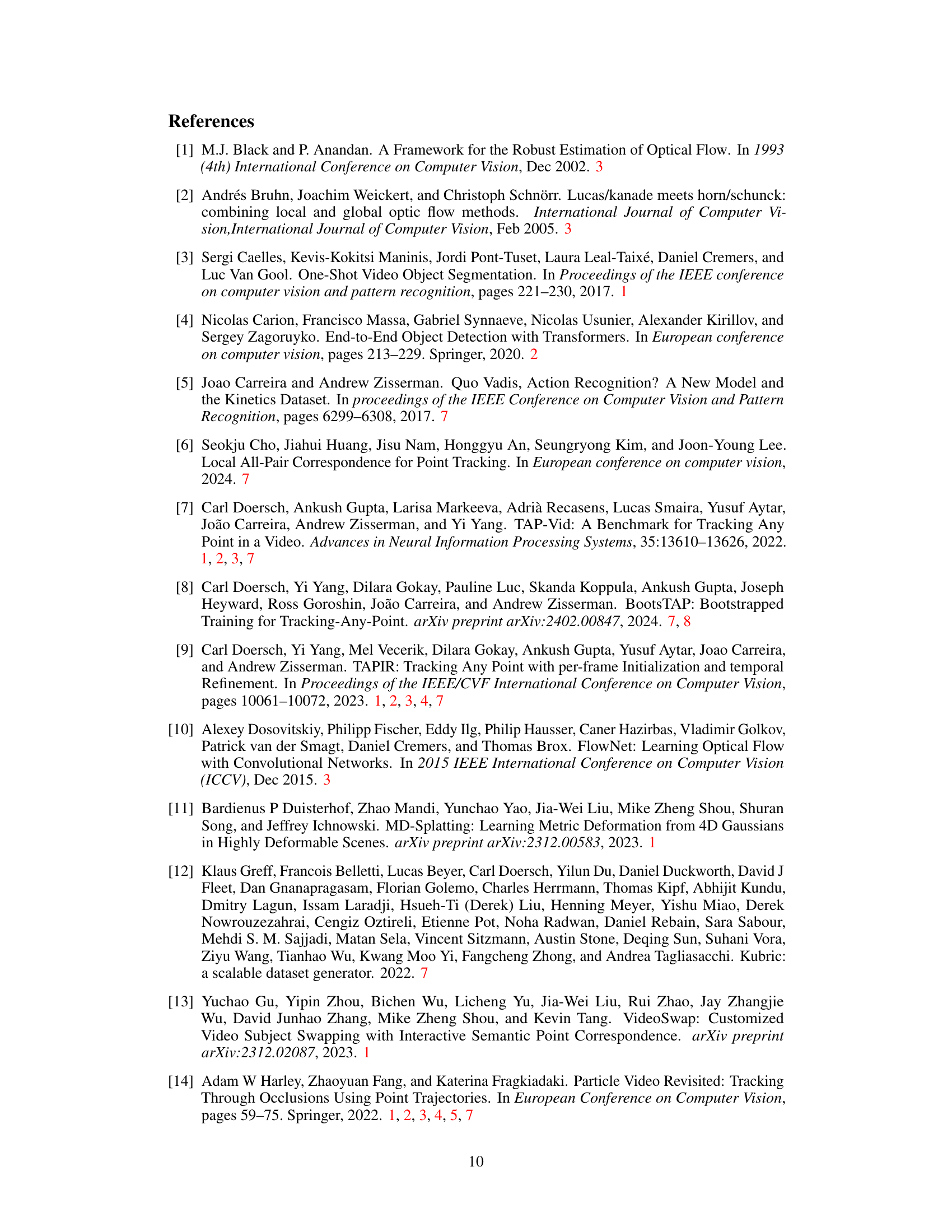

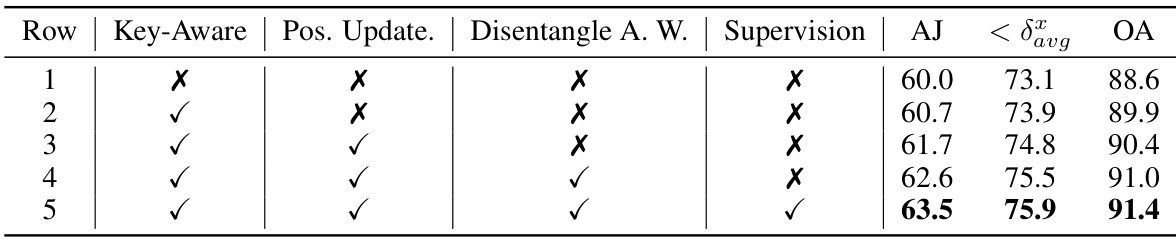

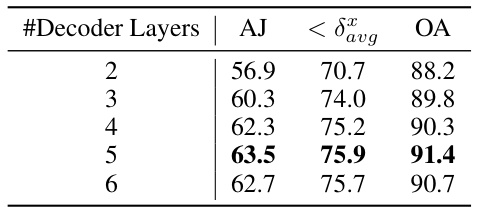

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, it appears crucial to isolate the impact of the attention-based position update and related mechanisms (key-aware attention, disentangling of attention weights). Removing each component individually allows for measuring its effect on overall performance metrics, revealing whether it improves or hinders the model’s accuracy and efficiency. The results would ideally show a clear hierarchy of importance among the components, with the attention-based position update as the primary driver of improvement. A successful ablation study would provide quantitative evidence supporting the design choices and demonstrating that each component plays a significant, non-redundant role in achieving the superior performance of the proposed model.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section suggests several promising avenues. Addressing the computational cost of self-attention in the decoder is crucial for scaling to larger tasks. This likely involves exploring more efficient attention mechanisms or approximations. The authors also plan to integrate point tracking with other tasks, such as object detection, leveraging the unified framework established in the paper. This integration could allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the scene, improving the robustness and accuracy of both tasks. Finally, there is a strong interest in exploring more complex real-world datasets to further test the generalizability and robustness of the proposed TAPTRv2 approach. This involves finding datasets that are sufficiently challenging to identify potential weaknesses and guide future improvements. These future directions represent a thoughtful plan to build upon the existing work, overcoming limitations and expanding the applicability of the technique.

More visual insights#

More on figures

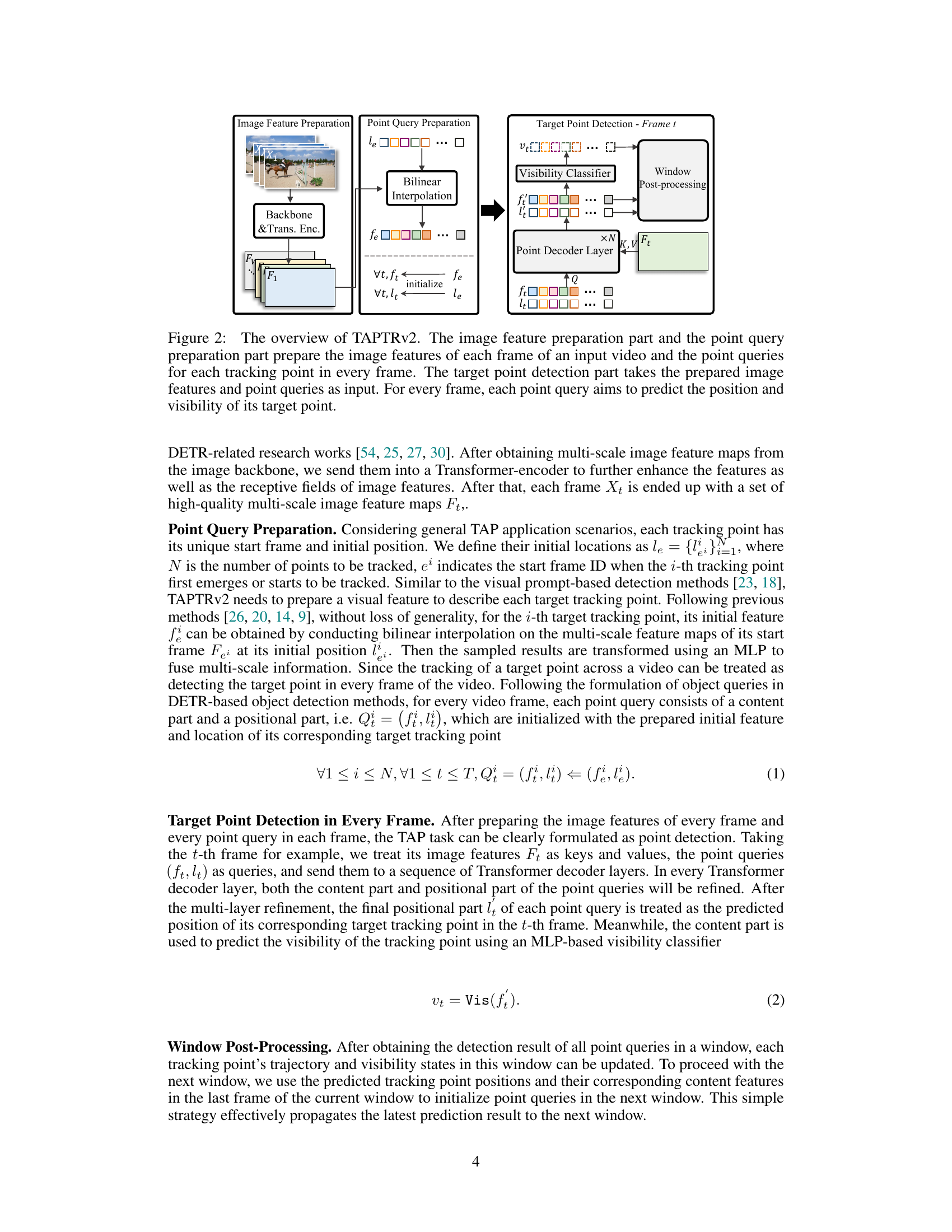

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of TAPTRv2, a method for tracking any point in a video. It consists of three main parts: 1. Image Feature Preparation: Extracts multi-scale image features from each frame using a backbone network (e.g., ResNet-50) and a Transformer encoder. 2. Point Query Preparation: Prepares initial features and locations for each point to be tracked using bilinear interpolation on the multi-scale feature maps. 3. Target Point Detection: Employs Transformer decoder layers to refine point queries using spatial and temporal attention, predicting the position and visibility of each point in each frame. A window post-processing step further improves accuracy by propagating predictions across multiple frames.

This figure compares the decoder layer of TAPTR and TAPTRv2. TAPTR uses cost volume aggregation, which contaminates the content feature and negatively impacts performance. TAPTRv2 introduces an Attention-based Position Update (APU) operation in the cross-attention mechanism. APU uses attention weights to combine local relative positions, predicting a new query position without contaminating the content feature, leading to a performance improvement.

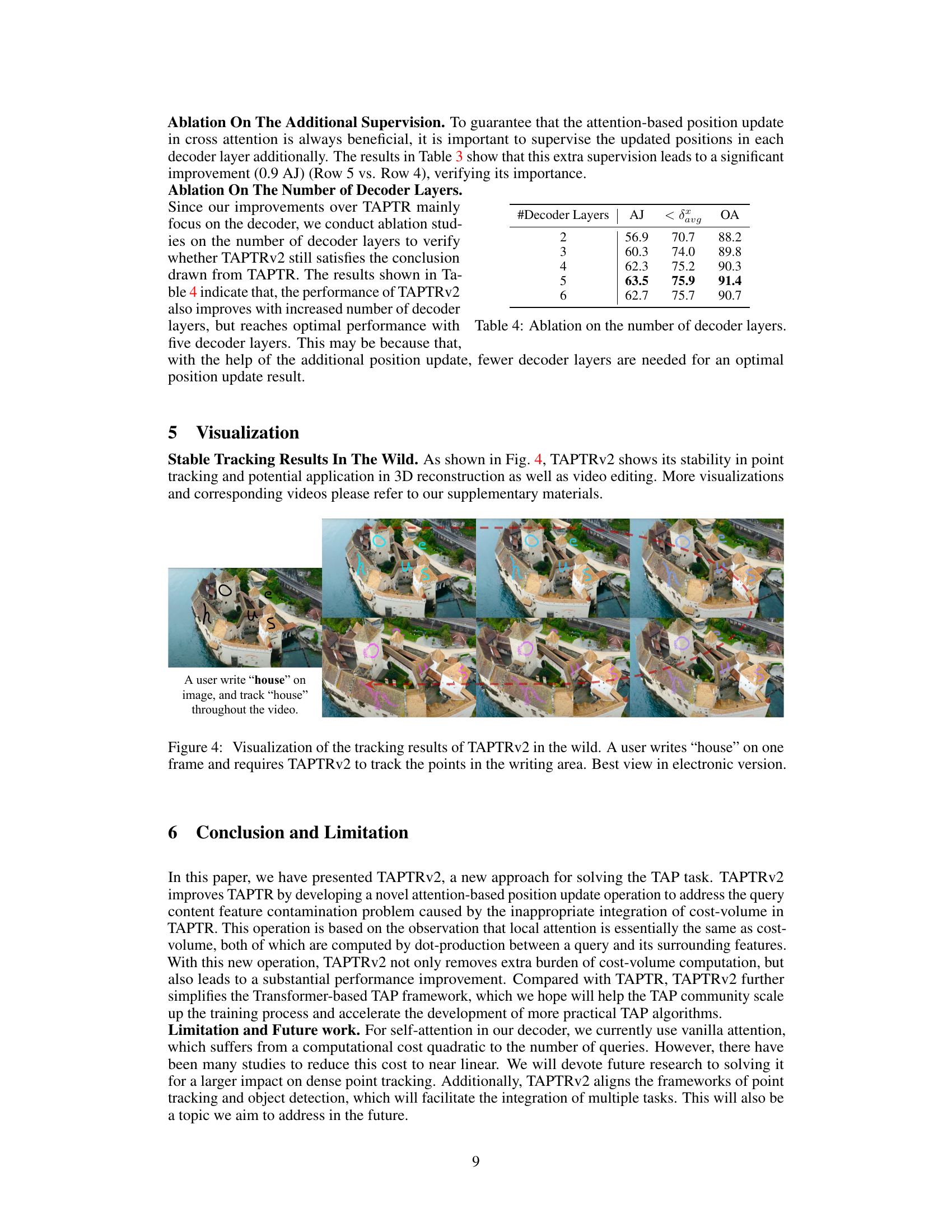

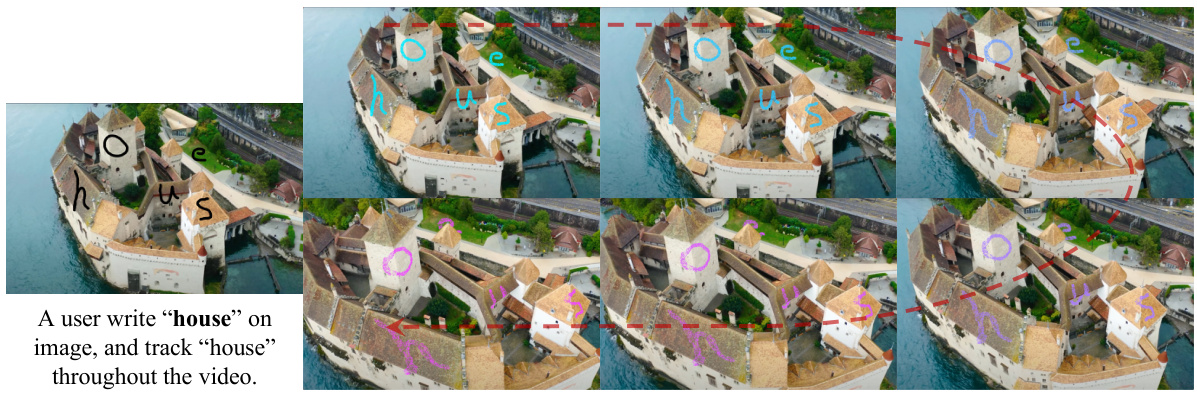

This figure shows the results of TAPTRv2 applied to a real-world video. A user hand-writes the word ‘house’ on a single frame of a video showing a castle. The algorithm then tracks the points within the handwritten word throughout the video, demonstrating its ability to maintain accurate tracking even with changing viewpoints and scene conditions. The red dashed lines connect the corresponding points in consecutive frames to show the tracking trajectory.

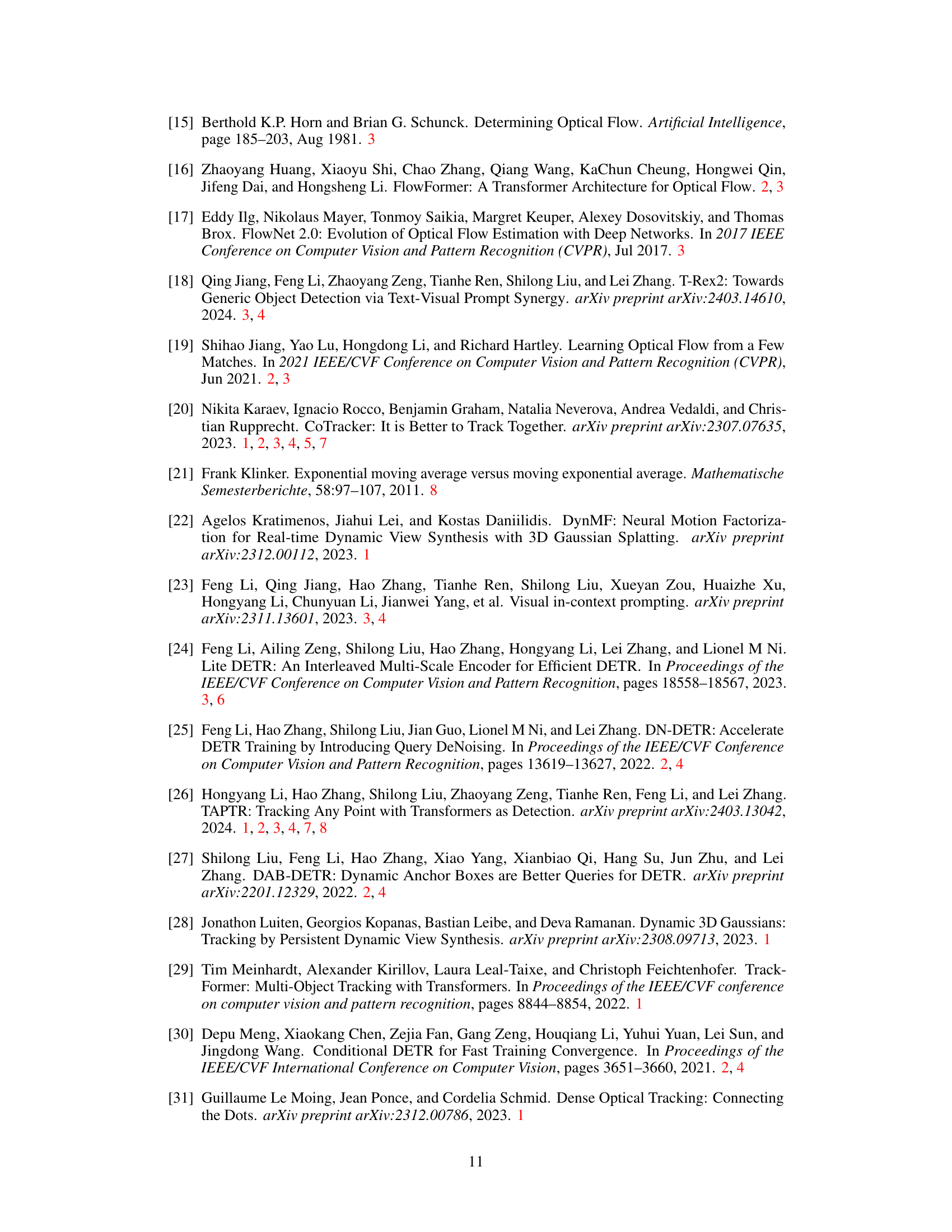

This figure shows the distributions of attention weights used for feature and position updates within the cross-attention mechanism. The distinct distributions highlight that different weight distributions are required for effectively updating content features and positional information. This supports the paper’s design choice to use a disentangler to separate the weight learning for these two distinct aspects.

This figure compares the decoder layer of TAPTR and TAPTRv2. TAPTR uses cost volume aggregation, which contaminates the content feature and negatively affects cross-attention. TAPTRv2 introduces an Attention-based Position Update (APU) operation in cross-attention to resolve this issue. APU uses attention weights to update the position of each point query, mitigating the domain gap and keeping the content feature uncontaminated for improved visibility prediction.

This figure shows three examples of trajectory estimation using TAPTRv2. In each example, a user clicks points on objects (fighters, horse, car) in a single frame. TAPTRv2 then tracks those points throughout the video, generating trajectories. This demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately predict the movement of selected points over time, even with complex motion and scale changes.

More on tables

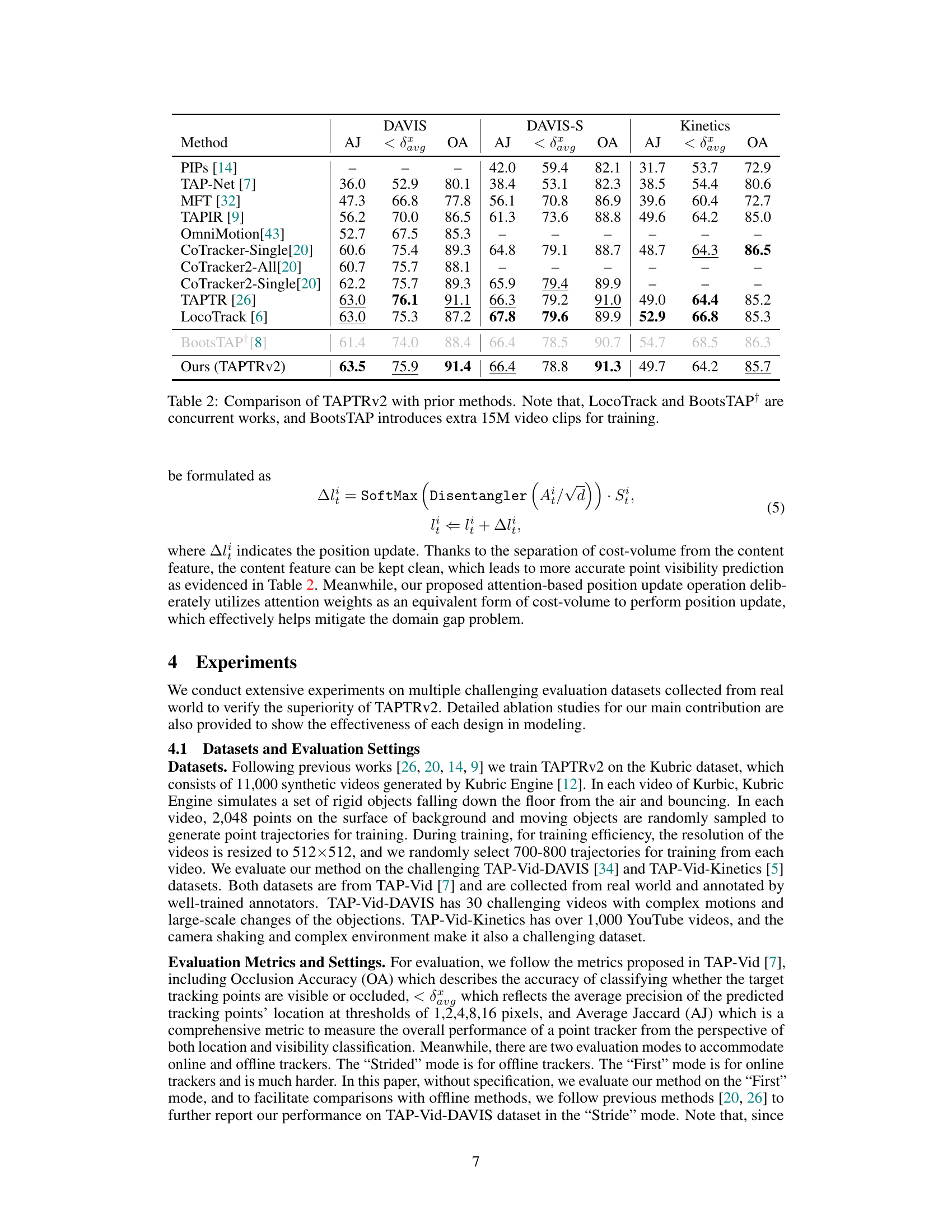

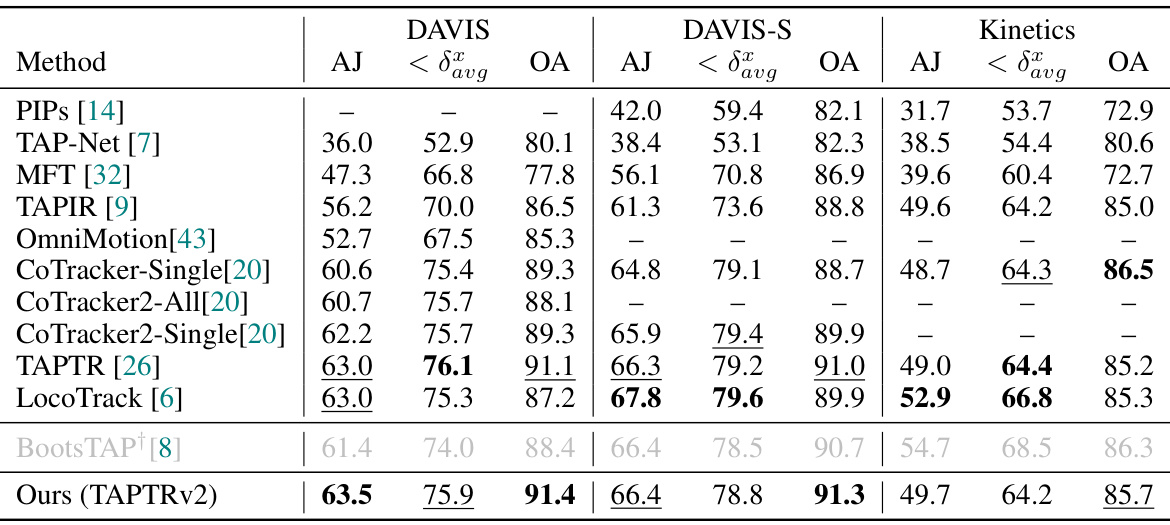

This table compares the performance of TAPTRv2 against several state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets: DAVIS, DAVIS-S, and Kinetics. The metrics used for comparison are Average Jaccard (AJ), Average Precision at different thresholds (< δαυα), and Occlusion Accuracy (OA). It highlights TAPTRv2’s superior performance, particularly noting that BootsTAP+, a concurrent work, uses a significantly larger training dataset (15M extra video clips).

This table presents the ablation study on the key designs of the attention-based position update. It shows the impact of using key-aware attention, position update, disentangling attention weights, and supervision on the performance (AJ, <binary data, 1 bytes><binary data, 1 bytes><binary data, 1 bytes>avg, OA). Each row represents a different combination of these design choices, allowing for an analysis of their individual contributions to the overall performance.

This table presents the ablation study results on the key designs of the attention-based position update mechanism in TAPTRv2. It shows the impact of key-aware attention, position update, disentangled attention weights, and supervision on the model’s performance. Each row represents a different configuration, indicating whether a specific design element was included or excluded. The results are measured in terms of Average Jaccard (AJ), average precision at different thresholds (< δxavg), and Occlusion Accuracy (OA), demonstrating the contribution of each component to the overall performance improvement.

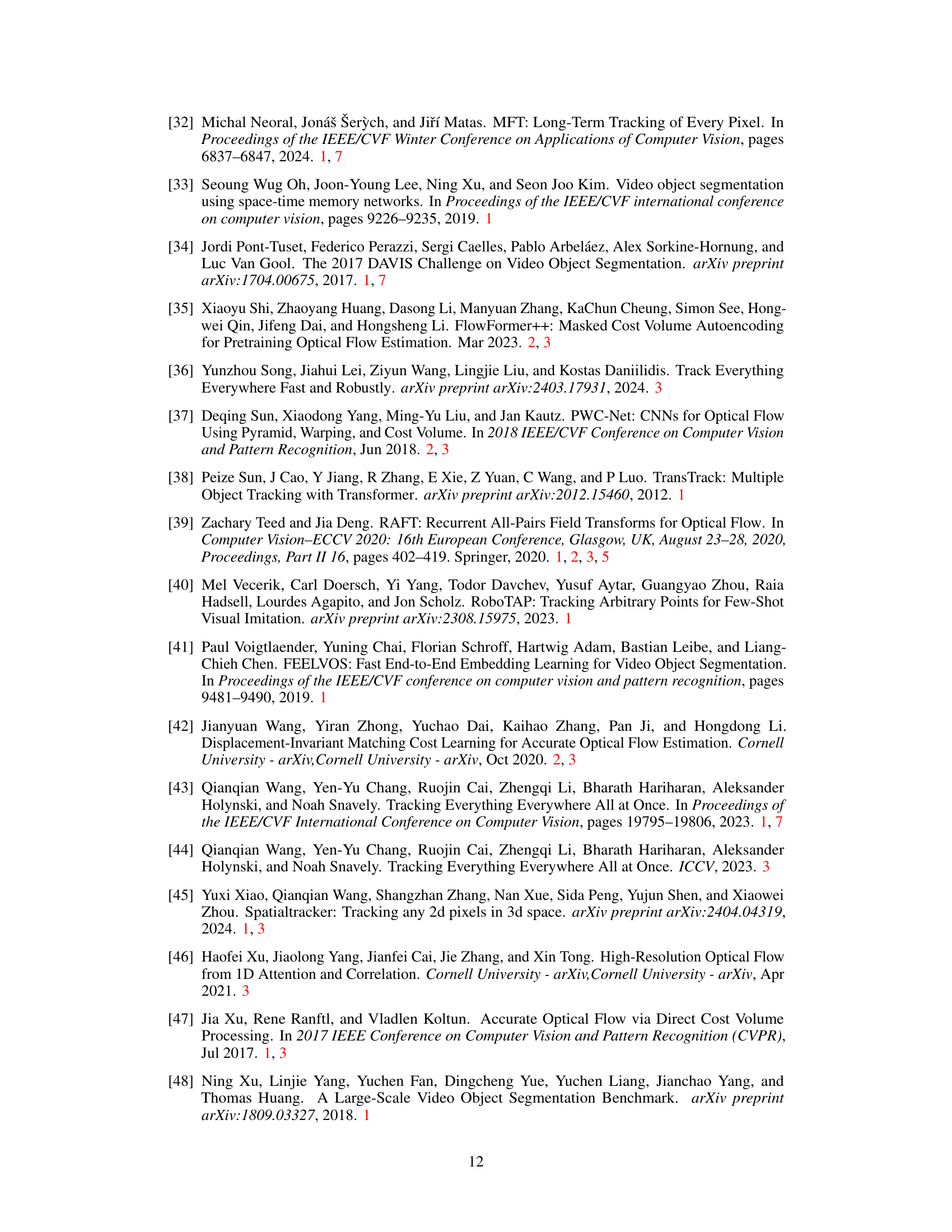

This table presents a comparison of the computational resource requirements between TAPTR and TAPTRv2. The comparison is made for two scenarios: tracking 800 points and tracking 5000 points. The metrics shown are frames per second (FPS), GFLOPS (floating-point operations per second), and the number of parameters (#Param) used by each model. The results demonstrate the improved efficiency of TAPTRv2, especially when tracking a large number of points.

Full paper#