↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) struggle with implicit reasoning, especially in composing internalized facts and comparing entities’ attributes. This deficiency limits systematic generalization and hinders the creation of truly robust AI systems. The existing attempts to resolve this mainly focus on explicit verbalizations of reasoning steps, which are unavailable during model pre-training.

This paper investigates whether transformers can learn implicit reasoning through extended training, focusing on composition and comparison tasks. The researchers found that transformers can learn implicit reasoning through “grokking,” a phenomenon where generalization emerges after extended training far beyond overfitting. Interestingly, generalization success varied across tasks, with comparison tasks showing higher success rates than composition tasks. Mechanistic analysis revealed distinct “generalizing circuits” within the model, providing insight into the variations in generalization performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the widely held belief that large language models (LLMs) are inherently incapable of implicit reasoning. By demonstrating that transformers can learn implicit reasoning through a phenomenon called “grokking,” the research opens new avenues for improving LLMs and understanding their limitations. It also provides actionable insights into model architecture and training strategies for enhanced generalization.

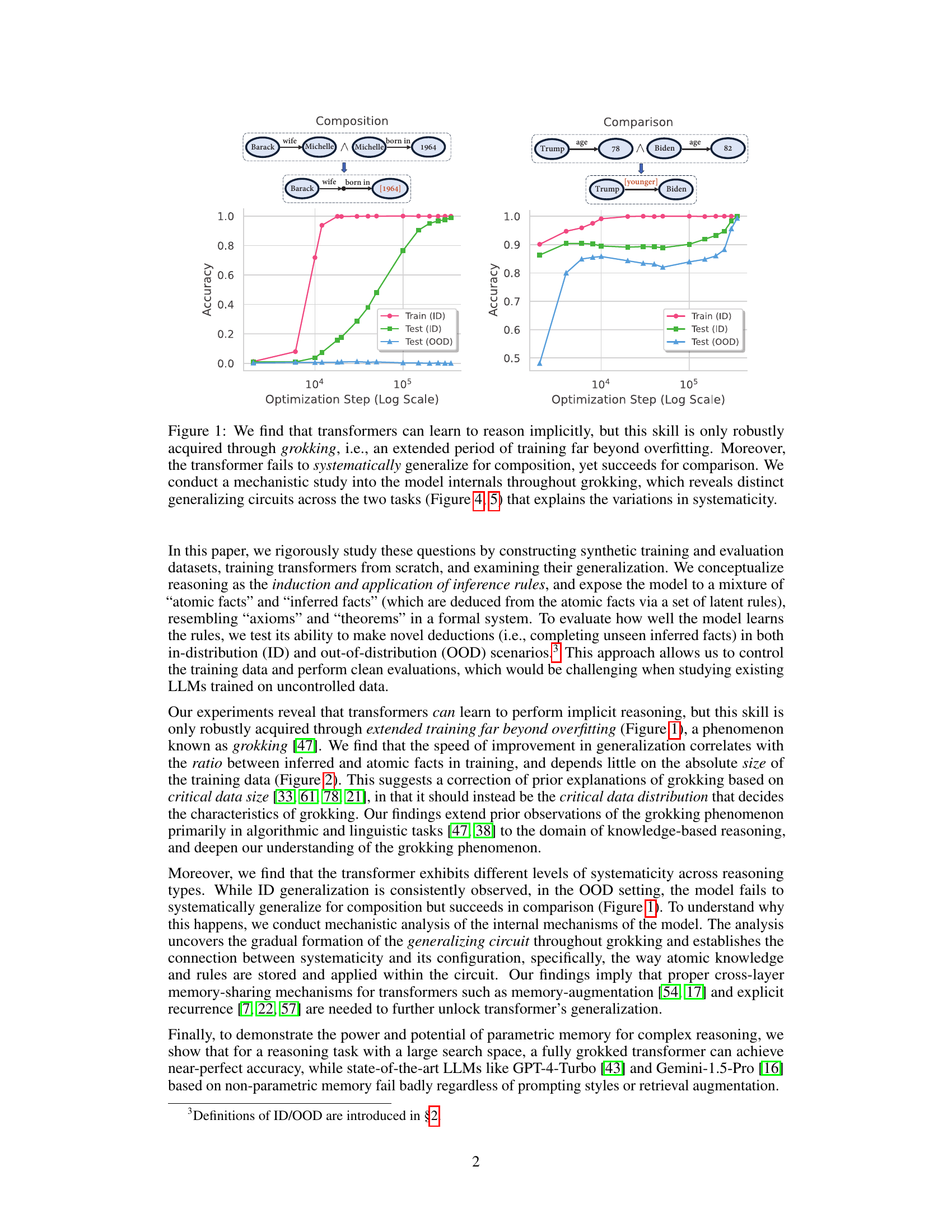

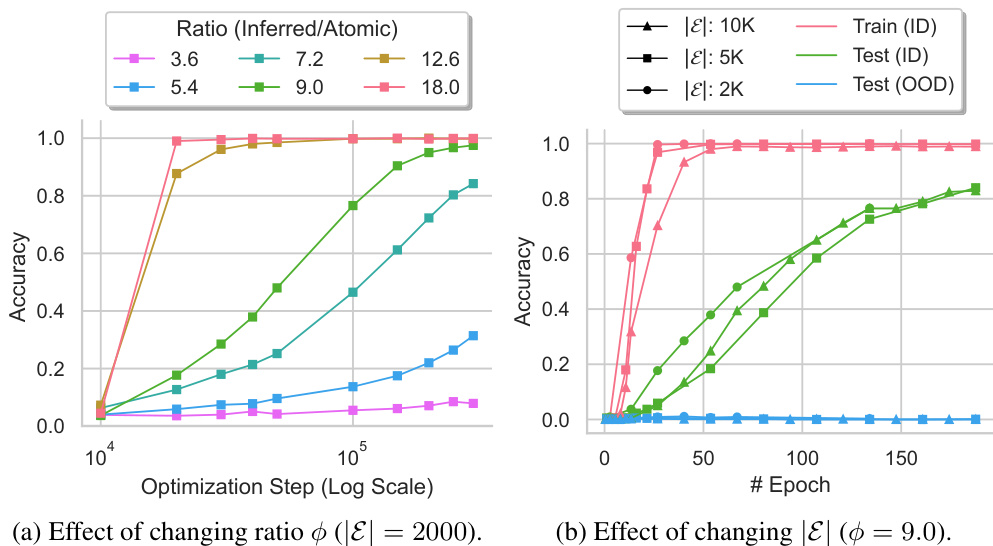

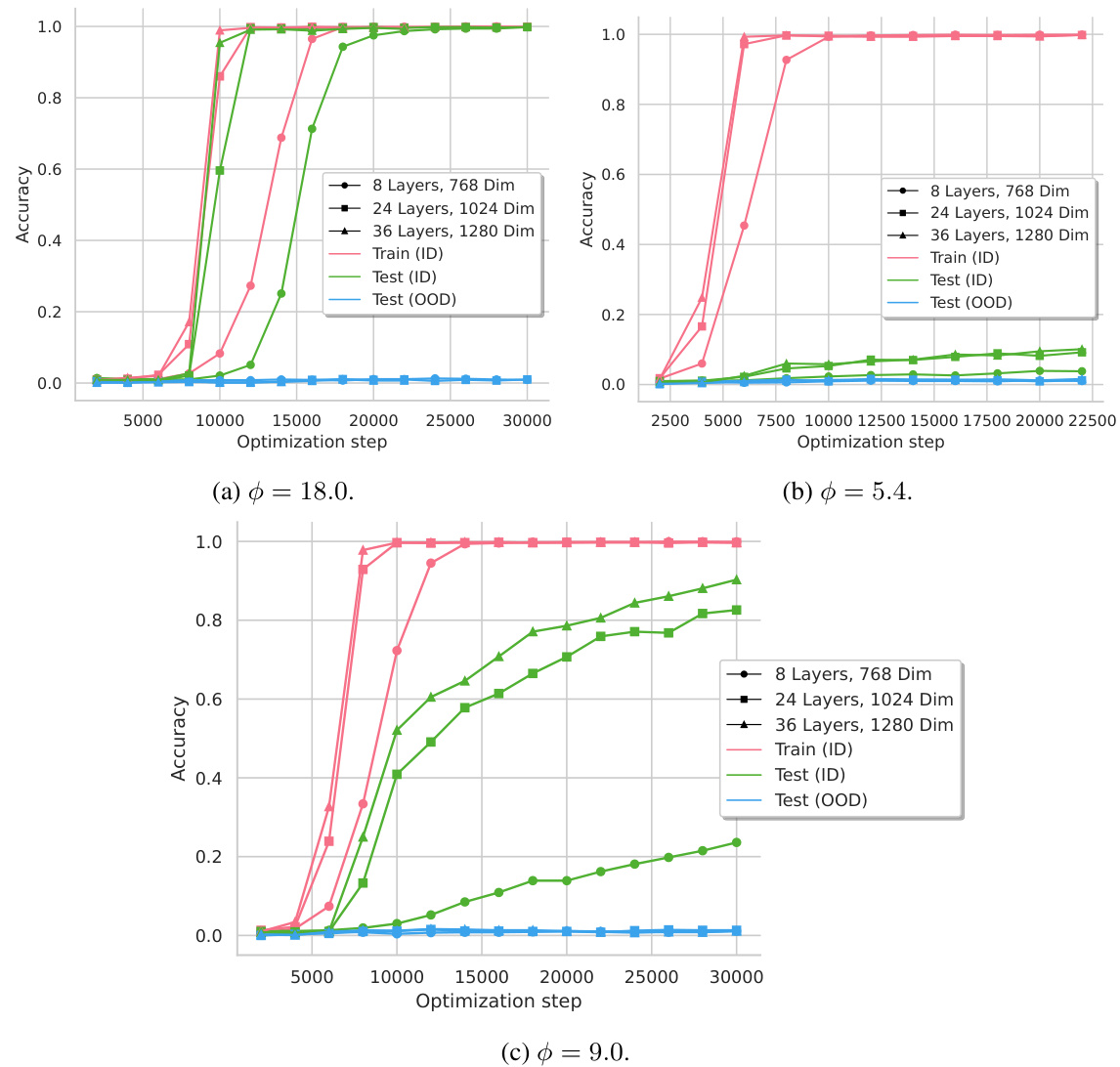

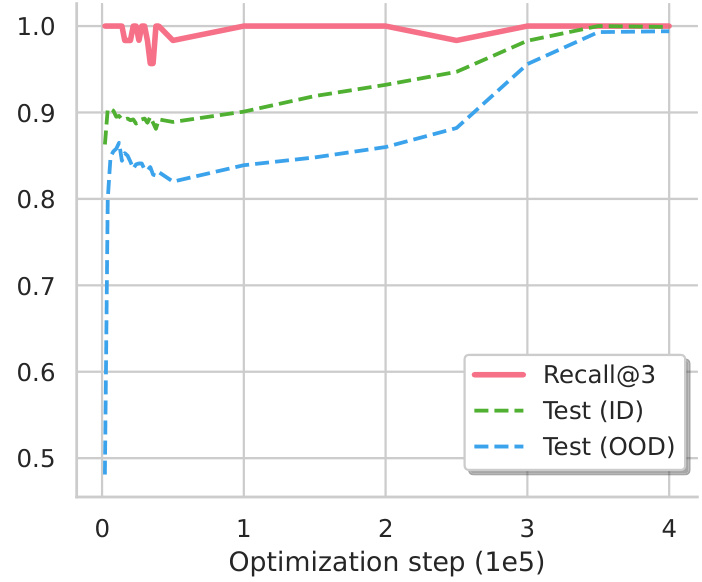

Visual Insights#

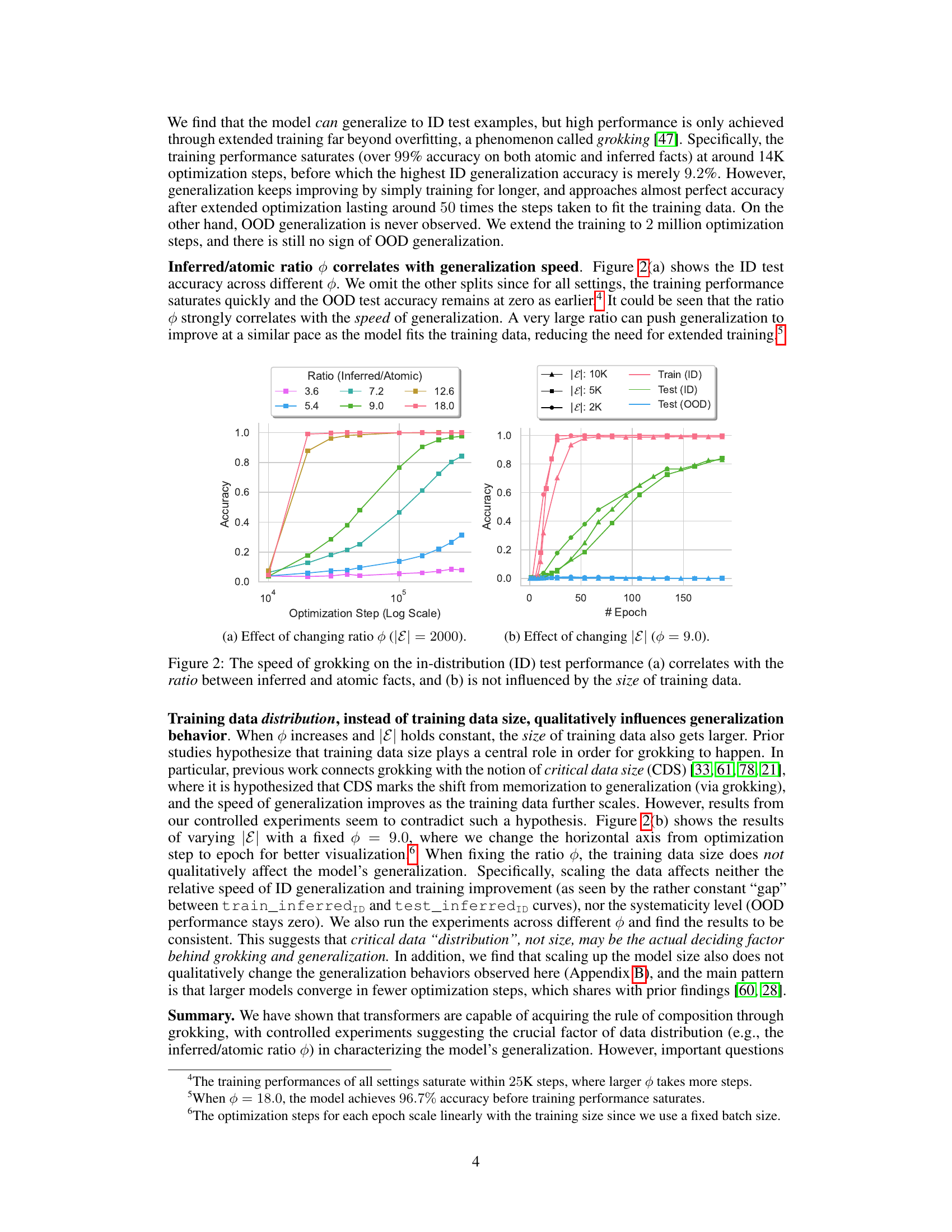

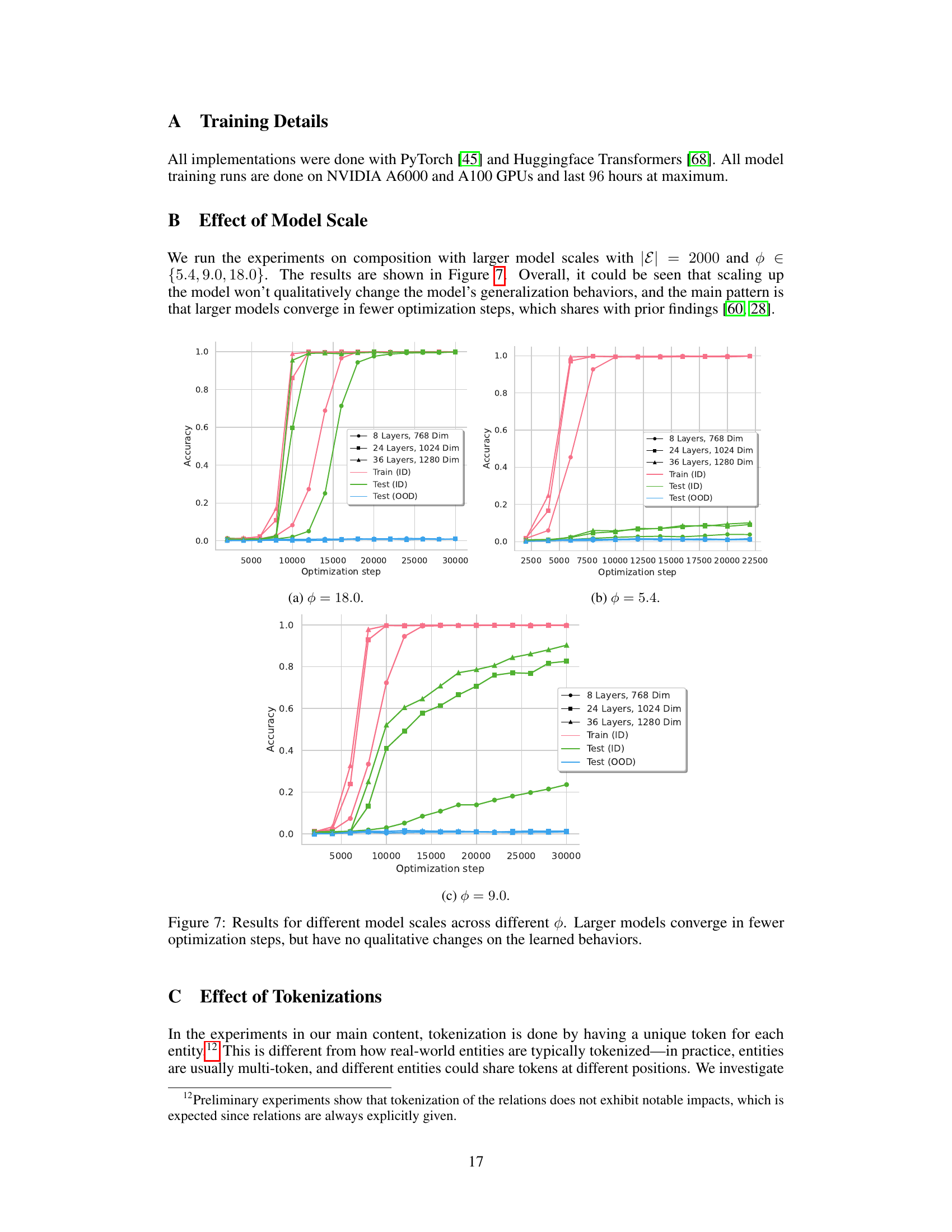

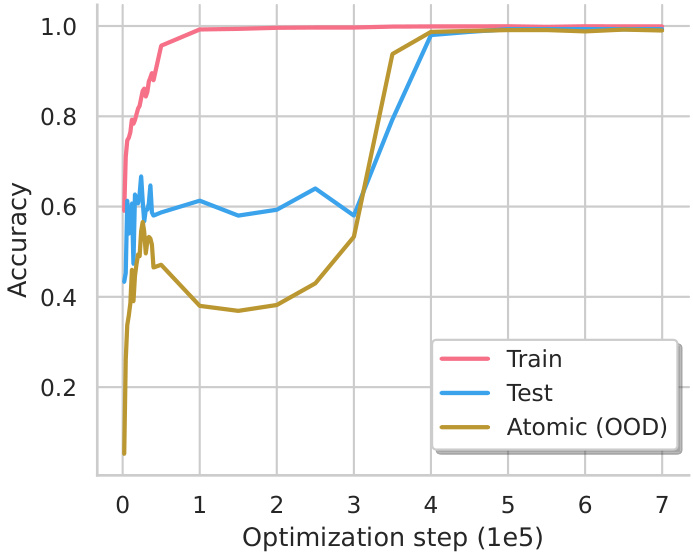

This figure shows the accuracy of two reasoning tasks (composition and comparison) during the training process. The x-axis represents the optimization steps (log scale), indicating the training progress. The y-axis shows the accuracy. Different colored lines represent training accuracy, in-distribution (ID) test accuracy, and out-of-distribution (OOD) test accuracy. The results demonstrate that transformers can learn implicit reasoning, but only after extended training beyond overfitting (grokking). Furthermore, generalization performance differs significantly between the two reasoning types; composition shows poor OOD generalization, while comparison shows good OOD generalization. This difference is further investigated later in the paper.

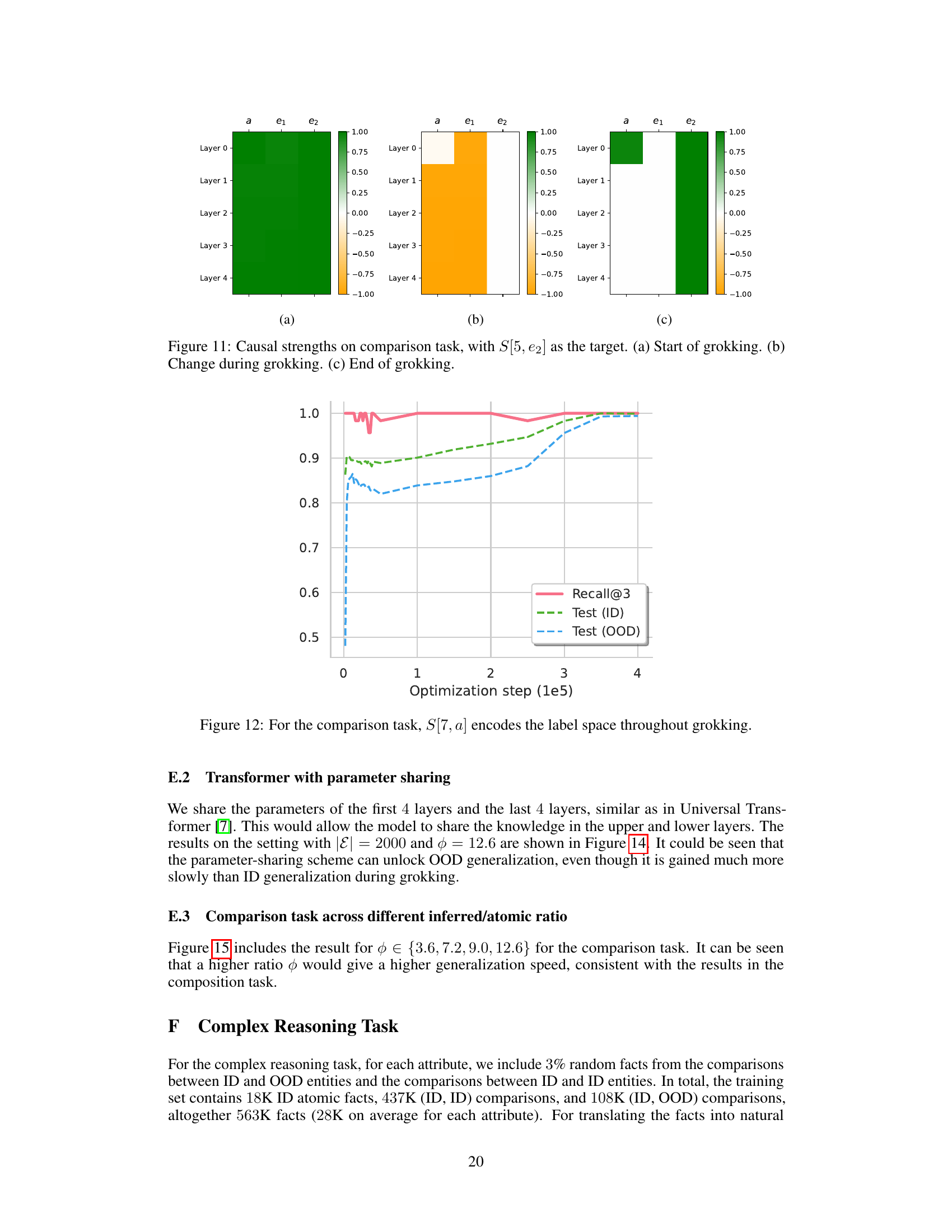

This table presents the results of a complex reasoning task, comparing the performance of GPT-4-Turbo, Gemini-Pro-1.5, and a Grokked Transformer model. The task involves comparing entity attributes, requiring multi-hop reasoning and a large search space. The table shows accuracy results for each model under different prompting styles (‘Direct’ and ‘CoT’ for chain-of-thought) and with or without retrieval augmentation (’+R’). The Grokked Transformer significantly outperforms the other models.

In-depth insights#

Implicit Reasoning#

Implicit reasoning, the ability of AI models to deduce conclusions without explicitly programmed rules, is a crucial area of research. Current large language models struggle with tasks requiring complex inference, highlighting a significant limitation in their capabilities. This paper delves into the mechanistic aspects of implicit reasoning within transformer networks, focusing on the phenomena of ‘grokking’—a sudden emergence of generalization after extensive training. The study shows that while transformers can acquire implicit reasoning skills, the level of success significantly varies depending on the task. The authors reveal distinct generalizing circuits formed within the network during the grokking process, explaining the observed differences in systematicity and the challenges in out-of-distribution generalization. Parametric memory, inherent in transformers, is contrasted with non-parametric alternatives, demonstrating a potential advantage in complex reasoning scenarios where parametric memory shows superior performance. The research highlights the need for further architectural refinements to improve cross-layer knowledge sharing and enhance the reliability of implicit reasoning in AI systems.

Grokking Mechanism#

The concept of “Grokking Mechanism” in the context of transformer models refers to the emergent, often sudden, improvements in generalization observed after extended training far beyond the point of overfitting. This isn’t a pre-programmed process but rather an emergent property of the network’s internal dynamics. Research suggests that generalization may arise from the formation of specialized neural pathways or “circuits” that efficiently encode and utilize learned rules. These circuits, rather than simply memorizing the training data, seem to represent an abstract understanding of underlying relationships, enabling the model to reason and generalize to unseen data. Understanding how and why these circuits form is a key focus of future research, as this phenomenon may hold the key to unlocking the full potential of transformer models for complex reasoning and significantly improving their systematicity and robustness.

Composition Limits#

The hypothetical heading ‘Composition Limits’ likely explores the boundaries of compositional generalization in transformer models. The core issue is whether these models can robustly combine learned facts or rules to reason about novel situations. The paper probably investigates scenarios where the model fails to generalize compositionally, despite possessing the constituent knowledge. This could involve examining the model’s internal representations and identifying potential bottlenecks like limited memory capacity, insufficient cross-layer information flow, or architectural constraints hindering the construction of complex relational structures. Analysis might delve into the training data, exploring whether the distribution or quantity of compositional examples affects generalization. Another angle could be contrasting composition with other reasoning types (e.g., comparison) to pinpoint what makes composition uniquely challenging. The study may propose architectural modifications or training strategies to alleviate these limitations and improve the model’s capacity for systematic compositional generalization.

Parametric Memory#

Parametric memory, as explored in the context of large language models (LLMs), is a crucial aspect of their ability to reason and generalize. Unlike non-parametric memory which stores information explicitly, parametric memory integrates knowledge implicitly within the model’s parameters. This implicit encoding allows for efficient storage and flexible retrieval of information, unlike methods that rely on explicit memory indexing. However, this implicit nature presents challenges. The model’s ability to generalize, especially to out-of-distribution examples, depends heavily on the successful formation of a generalized circuit during training, a process often referred to as ‘grokking’. This is a key aspect of the research; determining why and how models achieve this is critical for improving their reasoning capabilities. While powerful when successful, parametric memory’s implicit nature makes it less interpretable than explicit methods, which hinders our understanding of its internal mechanisms and creates limitations in terms of systematic generalization. The development and analysis of such mechanisms are vital to unlocking the full potential of parametric memory in LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the grokking phenomenon to more complex reasoning tasks and datasets, investigating whether similar mechanisms are at play. Improving the transformer architecture to facilitate systematic generalization across distributions is also crucial. This might involve enhancing cross-layer knowledge sharing or incorporating explicit memory mechanisms. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the relationship between parametric and non-parametric memory is needed, potentially leading to hybrid models that combine the strengths of both. Finally, applying these insights to real-world problems, such as improving LLMs’ reasoning capabilities in domains requiring nuanced understanding, is a critical next step. Investigating the scalability of grokking to much larger models and datasets remains an open question, as does understanding whether it is a fundamental limit of current architectures or an artifact of training methods. Ultimately, unlocking the full potential of implicit reasoning in LLMs requires further advancements in model architecture and training strategies.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the training curves for composition and comparison tasks. The x-axis represents the optimization step (log scale), indicating the extent of training. The y-axis displays accuracy. For both tasks, accuracy improves significantly after an extended training phase (grokking). However, the generalization to out-of-distribution (OOD) examples differs between the tasks. Composition shows poor OOD generalization, while comparison exhibits successful OOD generalization, highlighting the different generalizing circuits developed for each reasoning type.

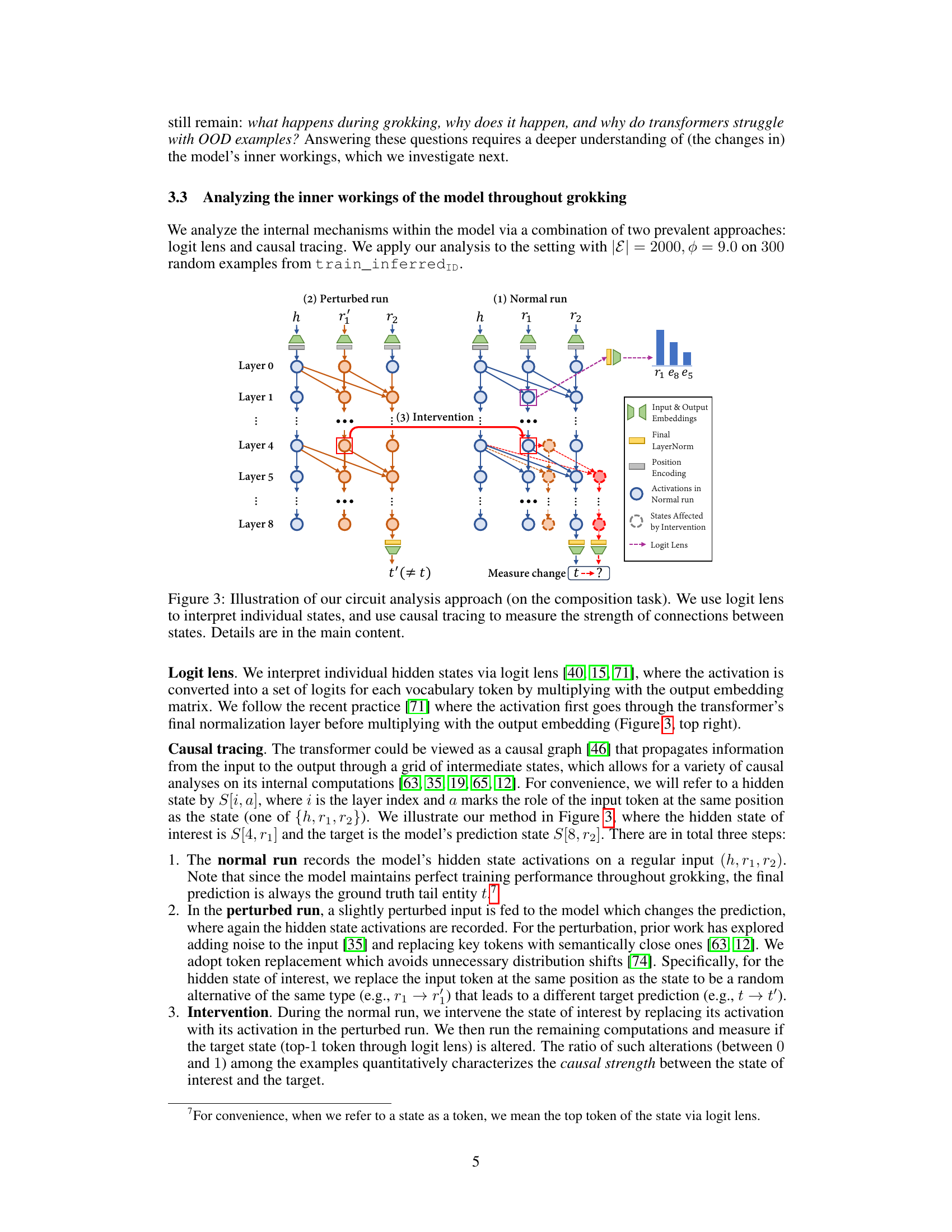

This figure illustrates the methodology used for circuit analysis in the paper. It shows the process of using logit lens and causal tracing to understand the model’s internal workings, particularly during the composition task. The logit lens is used to interpret individual hidden states, while causal tracing measures the strength of connections between states. The normal and perturbed runs are shown, along with an intervention step that helps quantify the causal relationships.

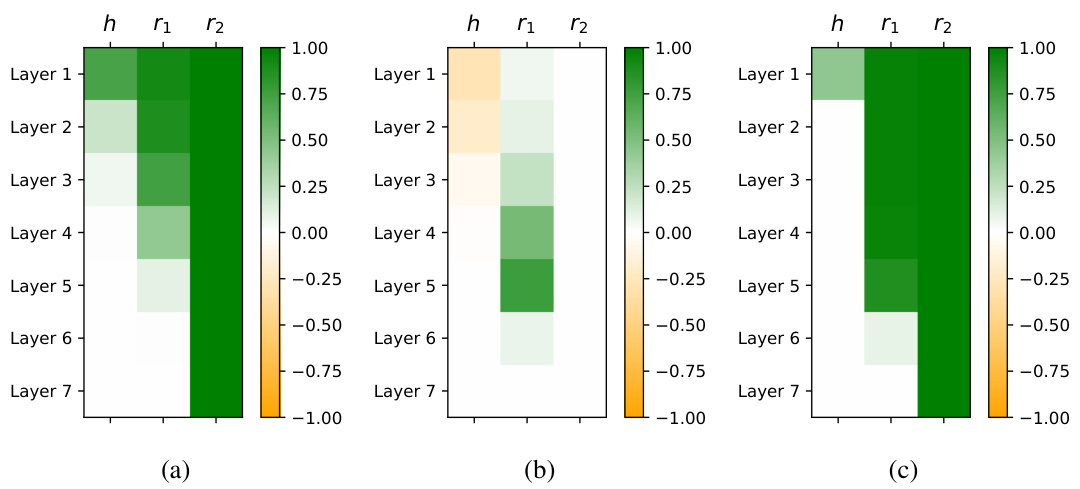

This figure demonstrates the generalizing circuit developed during the grokking process for the composition task. (a) shows a simplified causal graph highlighting key states in the model’s layers involved in the reasoning process. (b) illustrates the increase in causal strength between states during grokking, specifically focusing on the connection between the intermediary state and the final prediction. (c) displays the mean reciprocal rank (MRR) of the bridge entity and the second relation across different training stages, showing how these features become more reliably predicted as the model progresses through grokking.

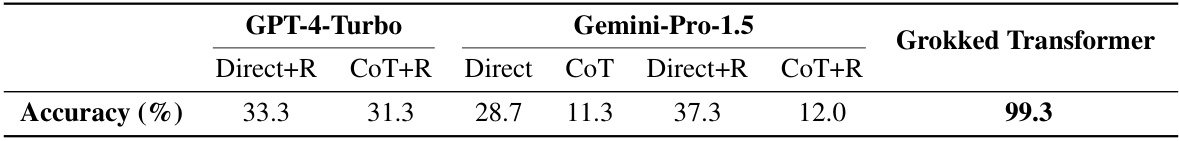

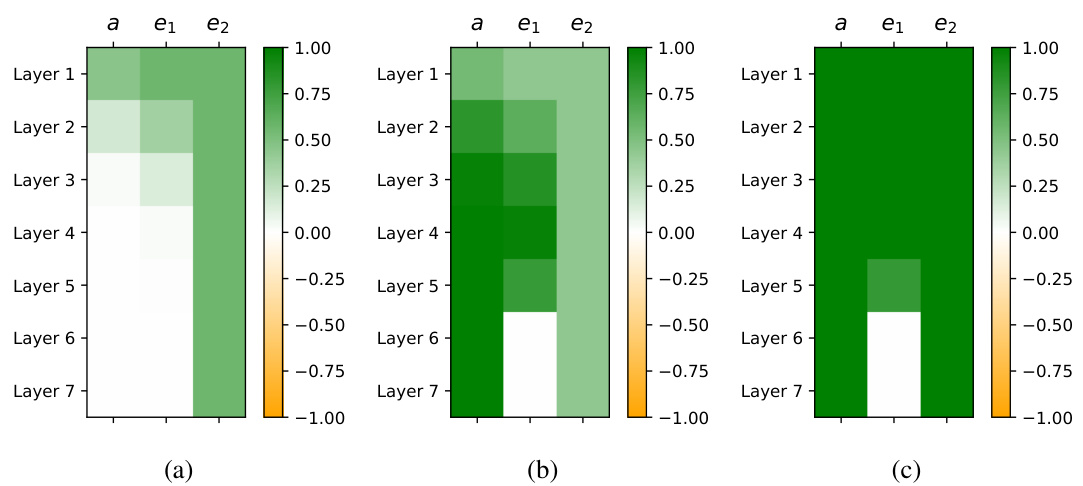

This figure presents a mechanistic analysis of the comparison task within a transformer model. Panel (a) shows the identified ‘generalizing circuit,’ a network of interconnected neurons essential for successful comparison. Panel (b) illustrates changes in the strength of causal connections between neurons throughout the ‘grokking’ phase (extended training resulting in improved generalization). Panel (c) displays the mean reciprocal rank (MRR) of attribute values (v1 and v2) within specific neurons, further clarifying the model’s internal workings during this critical learning phase. The figure highlights the emergence of efficient parallel processing for the comparison task.

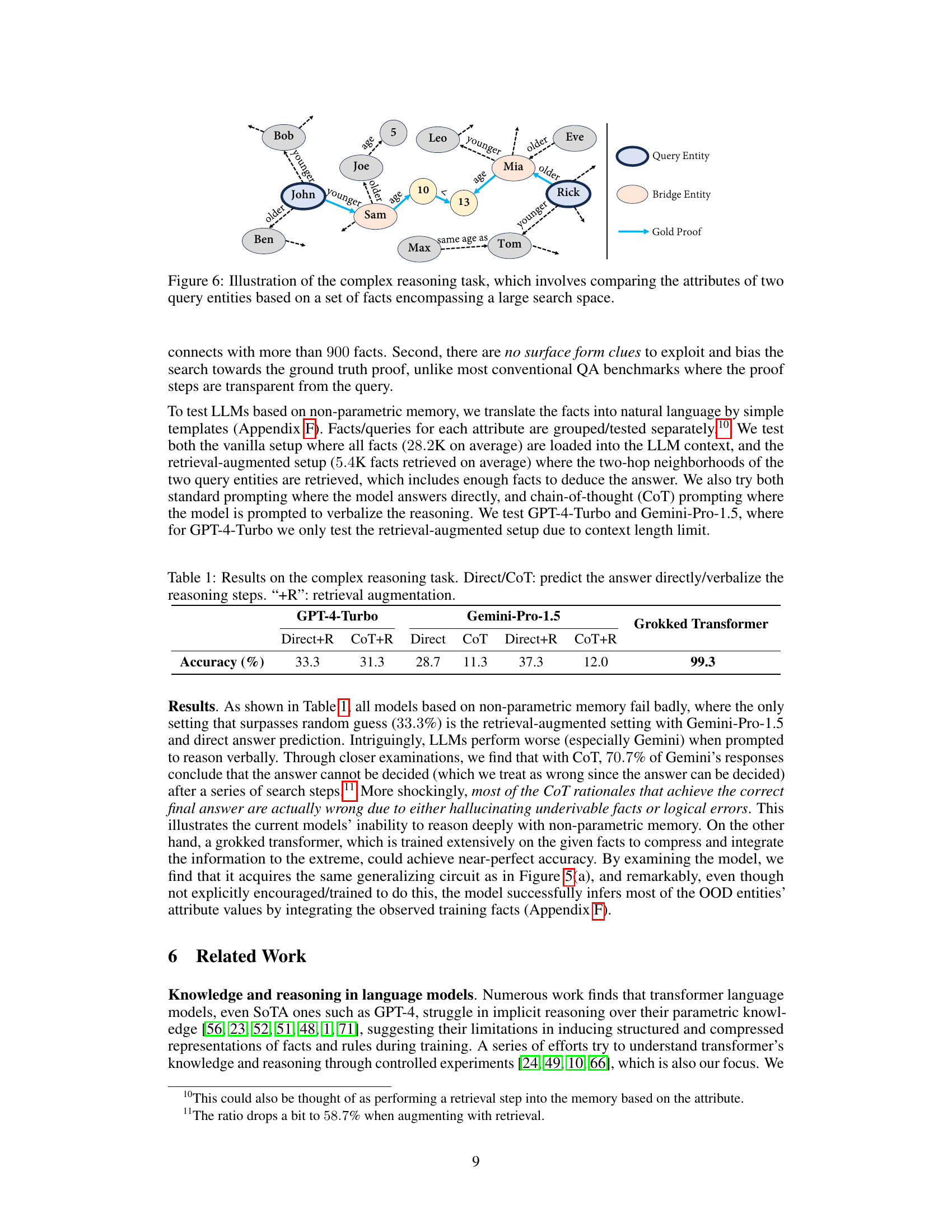

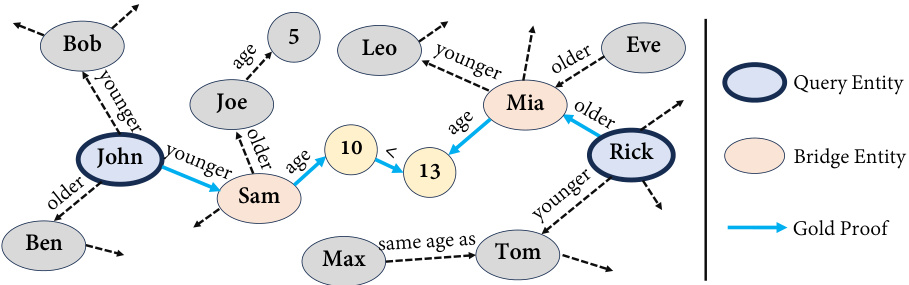

This figure illustrates a complex reasoning task where the goal is to compare the attributes of two query entities (in dark blue circles) using a large knowledge graph. The knowledge graph shows various entities and their age relationships. To answer the query, the model needs to discover a path (indicated by blue arrows) connecting the two query entities via intermediary entities (in light beige circles) referred to as bridge entities. This path represents a chain of reasoning steps that lead to the final comparison. The complexity arises from the large search space— numerous entities and their connections must be considered to identify the correct path which proves the final comparison.

The figure shows the accuracy of the transformer model on in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) test sets for composition and comparison tasks. The results reveal that implicit reasoning is only robustly acquired through extended training beyond overfitting (grokking). For composition, the model struggles to generalize to OOD examples. However, for the comparison task, the model demonstrates successful generalization to OOD examples. This difference in systematicity is explained by distinct generalizing circuits within the model identified later in the paper.

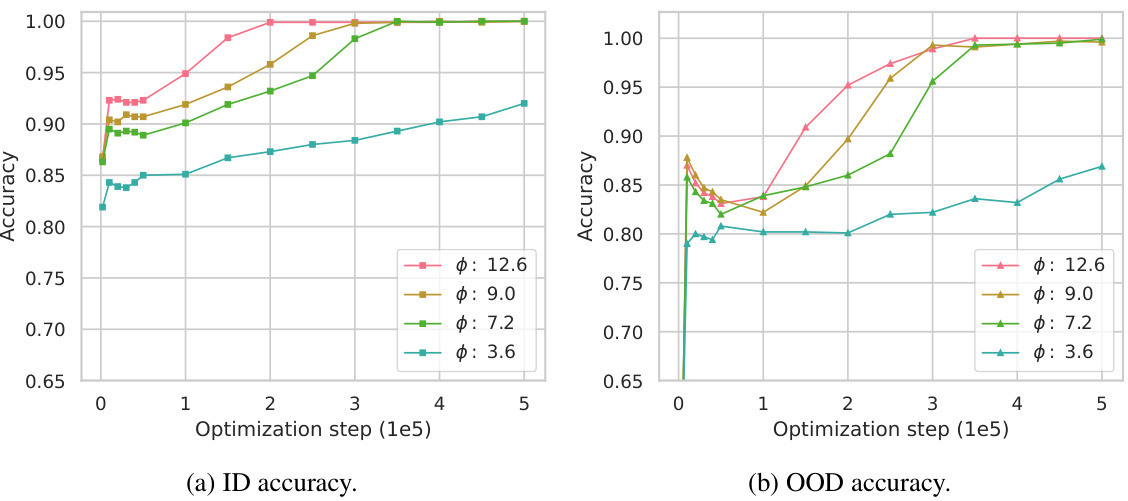

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted to investigate the impact of tokenization on the composition task. Two versions of tokenization were used: one with a single token per entity and another with two tokens per entity (mimicking first and last names). Subfigure (a) shows the accuracy of the model on in-distribution (ID) test data for various levels of token multiplicity. A higher token multiplicity indicates that more entities share the same first or last name, effectively reducing the size of the model’s vocabulary. The results show that while a higher multiplicity delays the onset of generalization, it ultimately does not prevent generalization from occurring. Subfigure (b) further investigates the internal state of the model, S[5, r1] which encodes the bridge entity b, using a probing task. This shows that the model is able to consistently decode the second token of b even with higher token multiplicity. This demonstrates the robustness of the model’s learning to different forms of tokenization.

This figure shows the generalizing circuit that emerges during the grokking phenomenon for the composition task. Panel (a) illustrates the circuit’s structure, highlighting key connections between different layers of the transformer model. Panel (b) illustrates the change in causal strength between states during the grokking process. Panel (c) displays the mean reciprocal rank (MRR) for the bridge entity (b) and the second relation (r2) at specific states (S[5, r1] and S[5, r2]) within the circuit, showcasing how these factors evolve over time.

This figure presents a mechanistic analysis of the composition task within the transformer model. It illustrates the evolution of the ‘generalizing circuit’—a pathway within the network responsible for generalization—during the grokking phase. Panel (a) shows a schematic of this circuit, highlighting key intermediate states. Panel (b) tracks changes in the causal strength of connections within the circuit over training, revealing how these connections strengthen as generalization emerges. Panel (c) shows the mean reciprocal rank (MRR) of certain components within the circuit as predicted by the logit lens method, demonstrating the improving ability of the model to access and manipulate knowledge during the grokking process.

This figure shows the accuracy of transformers on composition and comparison tasks during training. The x-axis represents training steps (on a log scale), and the y-axis shows accuracy. The key finding is that generalization (on held-out data) only emerges after a prolonged training phase (grokking). Furthermore, generalization is better for comparison tasks than composition tasks.

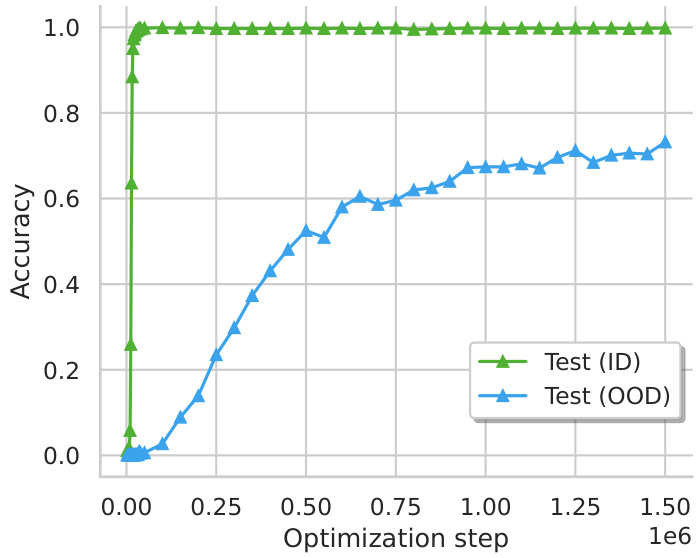

This figure shows the accuracy on in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) test sets for composition and comparison reasoning tasks over the optimization steps (log scale). The plots illustrate that both composition and comparison tasks exhibit grokking behavior (significant improvement in accuracy far beyond the point of overfitting). However, the generalization capabilities vary between tasks: while the model successfully generalizes to OOD examples for comparison, it fails to do so for composition. This difference highlights the varying levels of systematicity and suggests different underlying mechanisms for these reasoning types.

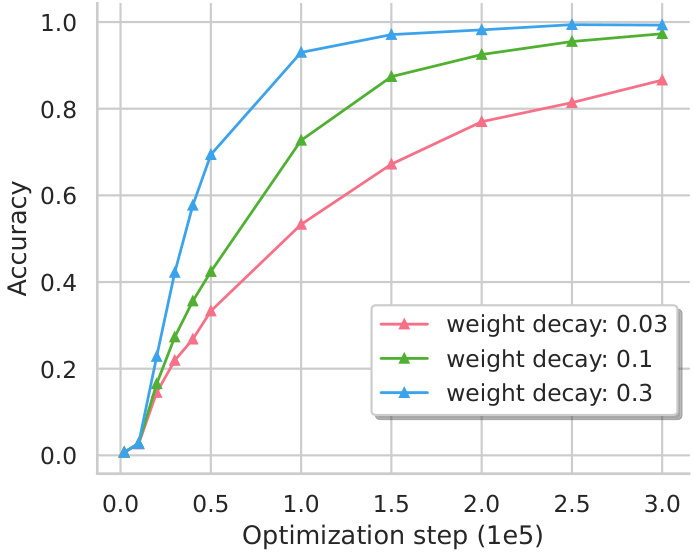

This figure shows the impact of varying the weight decay hyperparameter on the speed of the grokking phenomenon. The x-axis represents the optimization steps (in units of 1e5), and the y-axis represents the accuracy achieved on a task. Three lines are plotted, each corresponding to a different weight decay value (0.03, 0.1, and 0.3). The results indicate that a higher weight decay accelerates the grokking process, leading to faster convergence towards high accuracy.

This figure shows the accuracy of a transformer model on in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) test sets for composition and comparison reasoning tasks over the course of training. The key finding is that the model only achieves robust generalization after an extended period of training (grokking), and this generalization varies depending on reasoning type. For composition, the model struggles to generalize to OOD examples, while it successfully generalizes for comparison tasks.

This figure shows the accuracy of two reasoning tasks (composition and comparison) during the training process. The x-axis represents the optimization steps (log scale), and the y-axis represents the accuracy. It demonstrates that implicit reasoning is only robustly acquired through ‘grokking’, meaning extensive training beyond the point of overfitting. The figure also highlights that generalization performance varies across reasoning types, with successful generalization for comparison but not for composition.

This figure shows the training curves for composition and comparison tasks. The x-axis represents the optimization steps (on a logarithmic scale), and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The curves show that for both tasks, the model’s accuracy on in-distribution (ID) data increases significantly beyond the overfitting point (the grokking phenomenon). However, while the model generalizes well to unseen ID data for both tasks, it only systematically generalizes to out-of-distribution (OOD) data for the comparison task, not the composition task. This difference is further investigated and explained in later figures (4 and 5) using mechanistic analysis of the model’s internal workings.

Full paper#