TL;DR#

Global sensitivity analysis (GSA) helps understand how variations in input variables affect the output of a function, crucial for various scientific and engineering domains. However, evaluating these functions can be expensive, especially with limited experimental resources. This is addressed by using surrogate models, which are approximations of the real functions, but they require a substantial number of evaluations. Furthermore, derivative-based GSA methods can sometimes struggle with functions that are not monotonic (functions that do not always increase or decrease).

This research tackles these issues by introducing novel active learning acquisition functions that directly target derivative-based GSA measures (DGSMs), using Gaussian processes (GPs). The key innovation is to focus directly on learning the DGSMs rather than just the function itself, resulting in a significant improvement in sample efficiency. The researchers tested the methods on synthetic and real-world datasets, demonstrating superior performance compared to traditional methods, especially when resources are scarce. They also show that using information-gain based acquisitions functions yields the best results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on global sensitivity analysis (GSA), particularly those dealing with expensive black-box functions. It offers significantly improved efficiency through active learning, directly impacting various scientific and engineering fields that rely on GSA. The novel active learning strategies presented open up new avenues for research and application, making high-impact GSA more accessible.

Visual Insights#

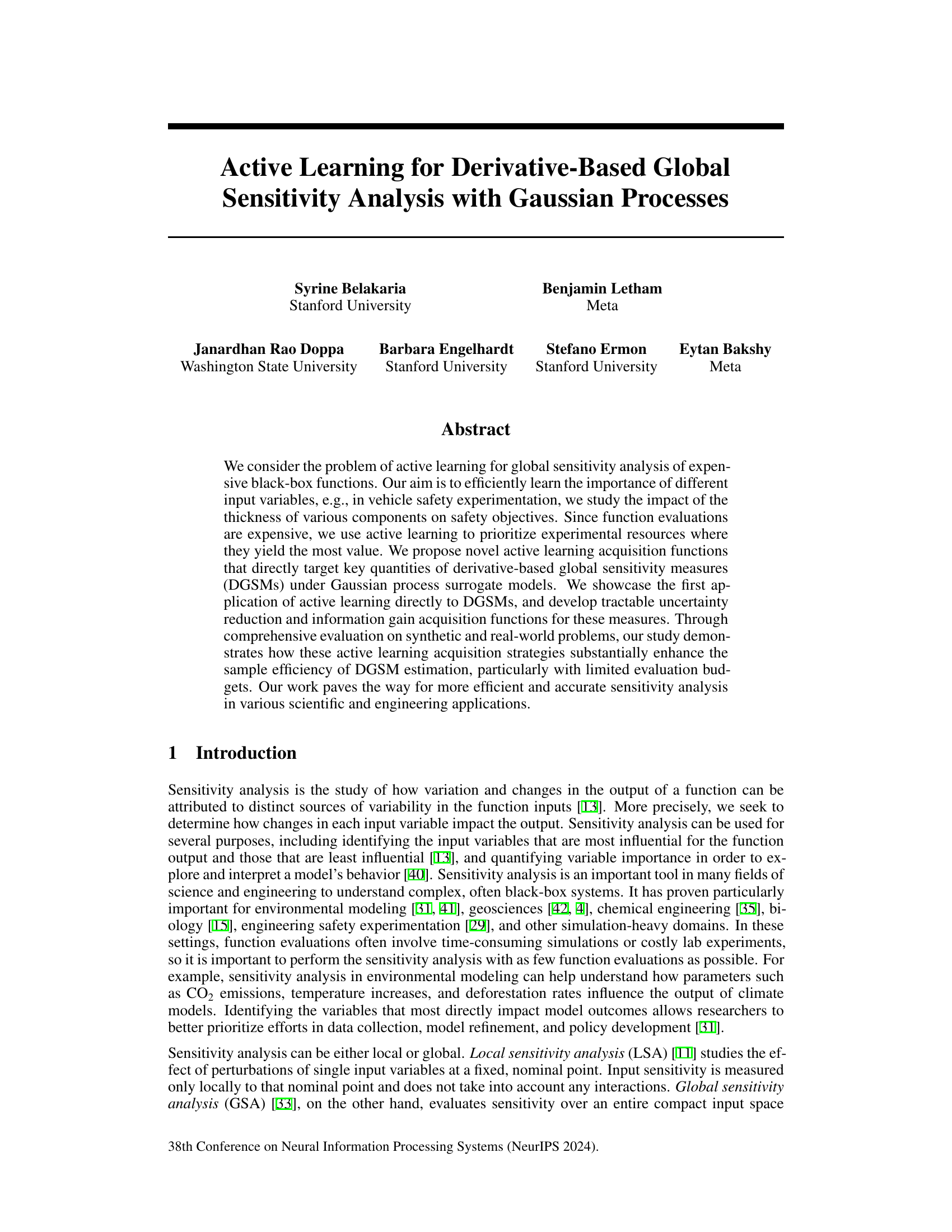

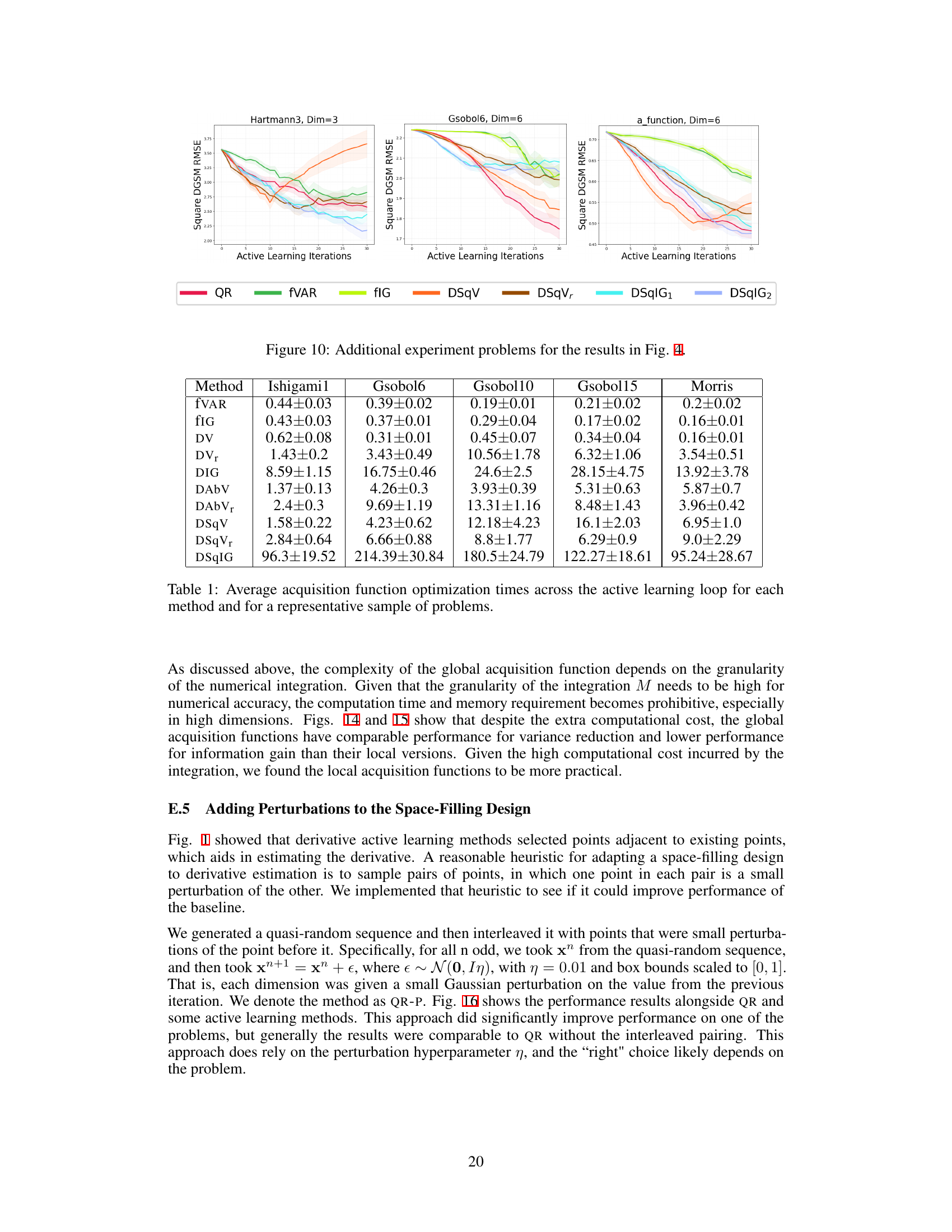

🔼 This figure shows the posterior distributions of the function (f), its derivative (df/dx), the absolute value of the derivative (|df/dx|), and the square of the derivative ((df/dx)²) obtained from a Gaussian Process (GP) model. Six observations of the function are used to build the model. The left panels display posterior means (lines) and 95% credible intervals (shaded regions) for each quantity. The right panels show acquisition functions for these quantities, illustrating the information gain from additional evaluations at each point, to help understand how choosing points for evaluations impacts the uncertainty in these sensitivity measures (DGSMs). The dotted vertical lines indicate the points that maximize the information gain for each quantity.

read the caption

Figure 1: (Left) Posteriors of f, df/dx, |df/dx|, and (df/dx)² are computed from a GP surrogate given six observations of f (black dots). Posteriors are shown as posterior mean (line) and 95% credible interval (shaded). (Right) Acquisition functions are computed from these posteriors, targeting f and derivative sensitivity measures. Dotted vertical lines show the maximizer. Acquisition functions that directly target DGSMs, not just f generally, are required to learn the DGSMs efficiently.

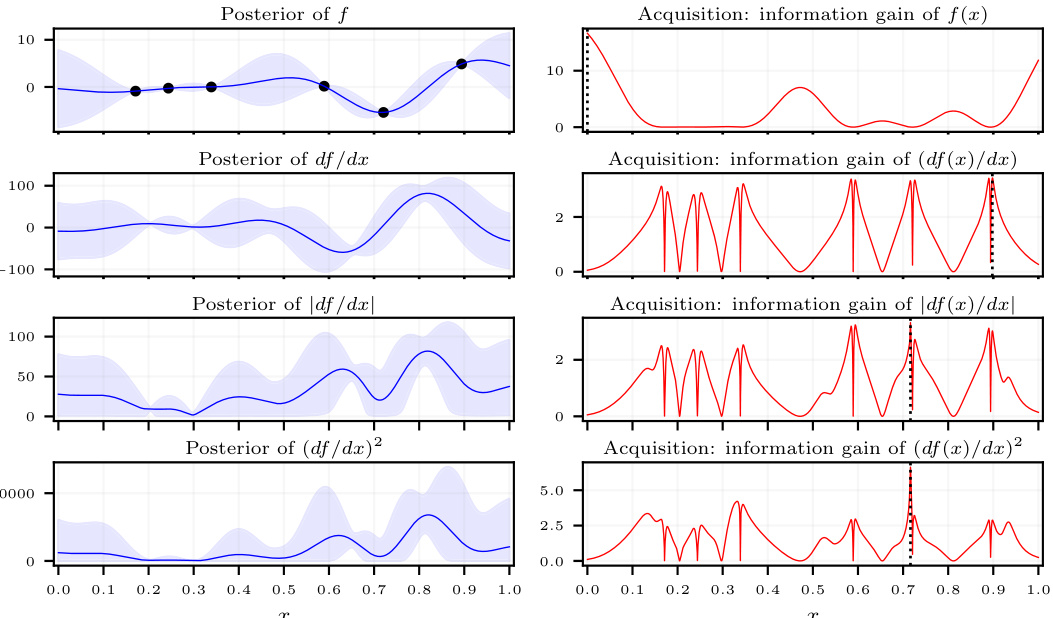

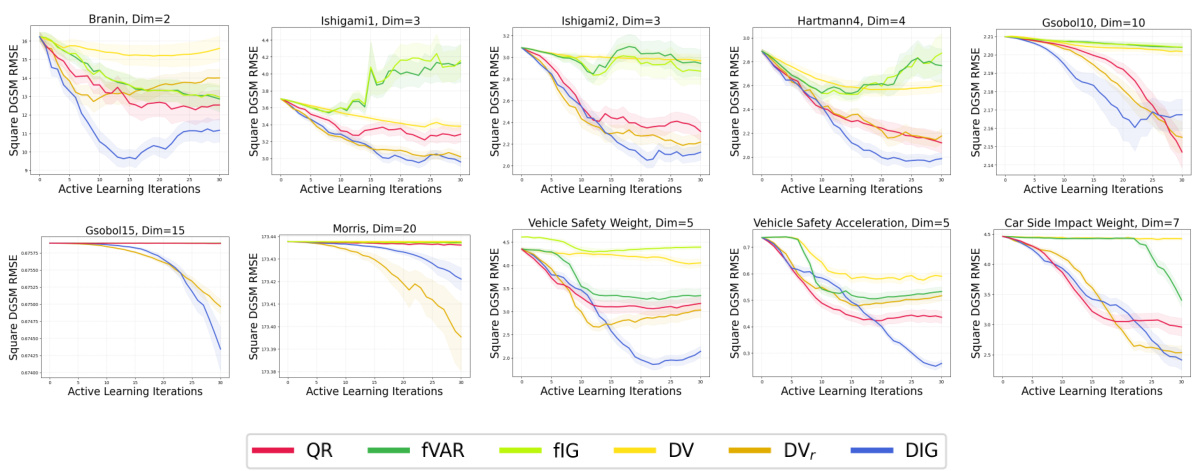

🔼 This table presents the average computation times for different acquisition function optimization methods across various benchmark problems. The reported times reflect the average time spent optimizing each acquisition function during a single iteration of the active learning process. These times provide insights into the computational cost associated with each method, which is crucial when considering their practical applicability, especially for computationally expensive problems. The table includes results for both variance-reduction and information-gain methods. The inclusion of representative problems helps evaluate how the runtime changes across different problem complexities.

read the caption

Table 1: Average acquisition function optimization times across the active learning loop for each method and for a representative sample of problems.

In-depth insights#

Active Learning GSA#

Active learning for global sensitivity analysis (GSA) offers a powerful approach to efficiently explore complex systems with expensive-to-evaluate functions. Traditional GSA methods often require numerous function evaluations, which can be computationally prohibitive or practically infeasible in many scientific domains. Active learning addresses this challenge by strategically selecting the most informative input points for evaluation. This targeted approach dramatically reduces the number of evaluations needed while still accurately estimating the sensitivity indices. Derivative-based GSA methods leverage the gradient information of the function, which often provides more accurate sensitivity insights compared to variance-based methods. The combination of active learning with derivative-based GSA is particularly promising as it focuses evaluation efforts on regions where gradient information is most uncertain, allowing for faster convergence and higher accuracy in sensitivity estimation. The key challenge in this area lies in the design of acquisition functions which optimally balance exploration and exploitation. Finding acquisition functions that directly target and efficiently estimate derivative-based sensitivity measures is a key area of current research, as this approach allows for faster and more targeted learning compared to approaches that only target the function itself.

Derivative-Based GSA#

Derivative-based global sensitivity analysis (DGSA) offers a powerful alternative to variance-based methods. Instead of relying on variance decomposition, DGSA leverages the gradient of the function to quantify the impact of input variables. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with complex, computationally expensive models where direct variance calculations are impractical. A key advantage is that DGSA directly captures the local sensitivity, providing finer-grained insights into how inputs influence outputs, especially useful in non-monotonic relationships where variance-based GSA might miss critical details. However, accurately estimating DGSA measures often requires many function evaluations, making it computationally costly. The paper explores active learning techniques to alleviate this, which is a crucial contribution. Active learning intelligently selects the most informative input points for evaluation, thus enhancing the efficiency of the DGSM estimation. This methodology is particularly relevant in applications with limited budgets for evaluations or computational resources, where efficient experimental design is paramount. By concentrating evaluation efforts on the regions where they yield the most information, active learning significantly improves sample efficiency, making DGSA a more accessible tool for a broader range of applications.

GP Surrogate Models#

Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate models are crucial for efficient global sensitivity analysis (GSA) of computationally expensive black-box functions. GPs offer a probabilistic framework, providing not only predictions but also associated uncertainties, which are essential for guiding active learning strategies in GSA. Instead of directly evaluating the expensive function, a GP is trained on a smaller set of evaluations to learn a surrogate model. This surrogate, approximating the original function, is then used for sensitivity analysis calculations, significantly reducing the computational burden. The choice of kernel function in the GP is crucial; it dictates the smoothness and complexity of the surrogate model, and it significantly impacts the accuracy of GSA. The derivative-based GSA methods presented in this paper rely heavily on the ability of GP surrogates to accurately represent not only the function’s value but also its derivatives, making differentiable kernel functions a necessity. The accuracy and efficiency of the surrogate model directly influence the quality of the sensitivity indices and hence the effectiveness of the active learning approach used.

Acquisition Functions#

The core of the active learning strategy lies within the acquisition functions, which intelligently guide the selection of the next data points to evaluate. The authors propose novel acquisition functions that directly target key quantities of derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs), moving beyond simply optimizing the model fit of the underlying function. Instead of focusing solely on minimizing uncertainty in function predictions, these functions directly address the uncertainty and information gain related to the DGSMs themselves. This targeted approach is crucial because estimating DGSMs requires accurate gradients, and the acquisition functions ensure efficient learning of the necessary information. Three strategies are presented: maximum variance, variance reduction, and information gain, each offering a different perspective on prioritizing data point selection. These strategies are carefully developed to ensure computational tractability under the assumption of a Gaussian process surrogate model, a common approach for handling expensive black-box functions. The key to the success of these functions lies in leveraging the mathematical properties of the Gaussian processes to compute tractable estimates of uncertainty and information gain for DGSMs, thereby making the active learning process both computationally feasible and highly sample-efficient. The efficacy of the proposed functions is rigorously evaluated using a range of synthetic and real-world problems, showcasing a substantial improvement over traditional space-filling methods in sample efficiency, particularly when dealing with limited evaluation budgets.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the acquisition functions to handle non-Gaussian processes would significantly broaden the applicability of the proposed active learning strategies. Currently, the reliance on Gaussian Processes limits the applicability to problems where this assumption holds. Another important direction would be developing batch active learning methods, moving beyond the myopic single-point selection. Investigating the theoretical properties of the proposed acquisition functions such as convergence rates and regret bounds would provide a deeper understanding and further improve their sample efficiency. Finally, a detailed comparison with variance-based global sensitivity analysis (ANOVA) methods would be crucial, assessing the relative strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches under various conditions. This could involve a study on the efficiency, accuracy, and computational cost, potentially leading to hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both derivative-based and variance-based methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

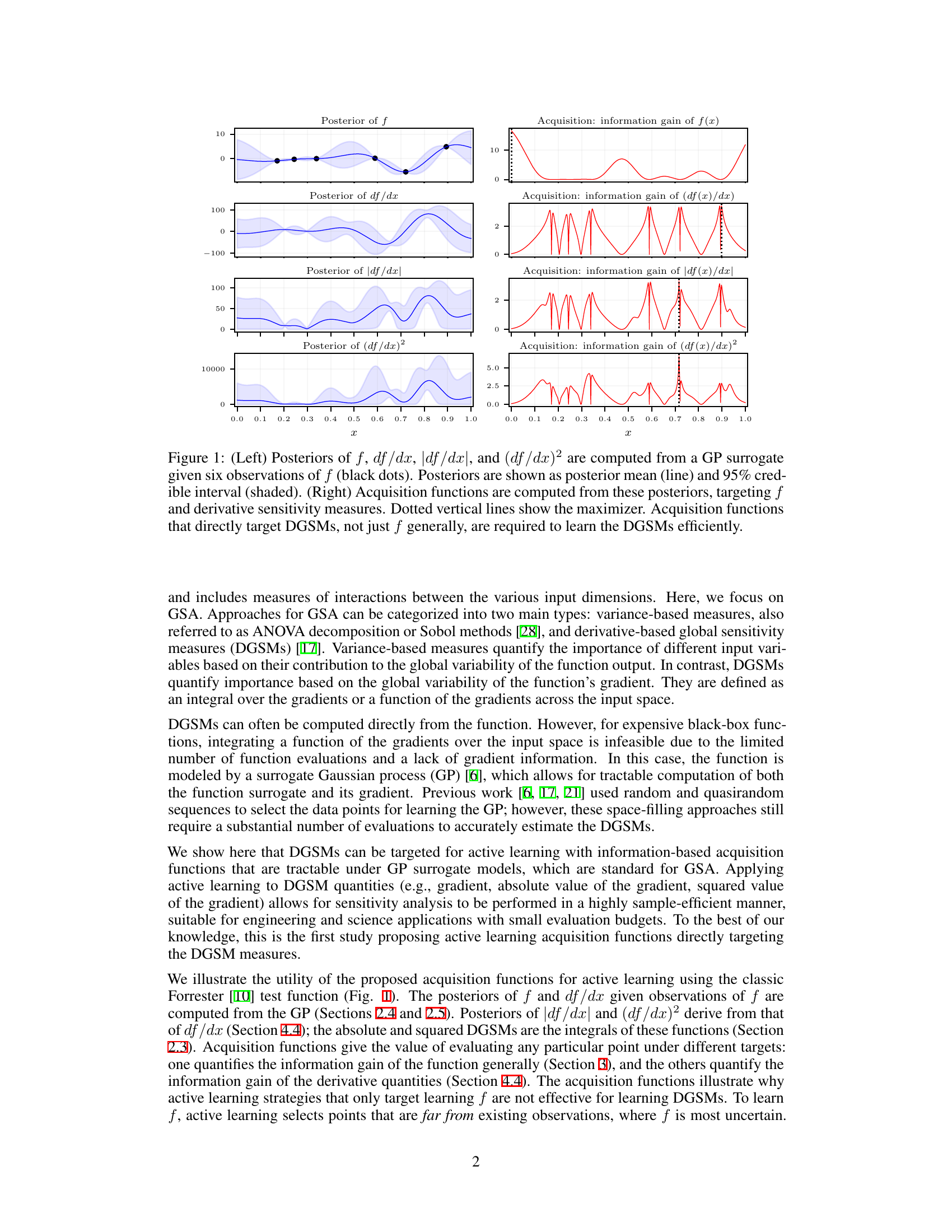

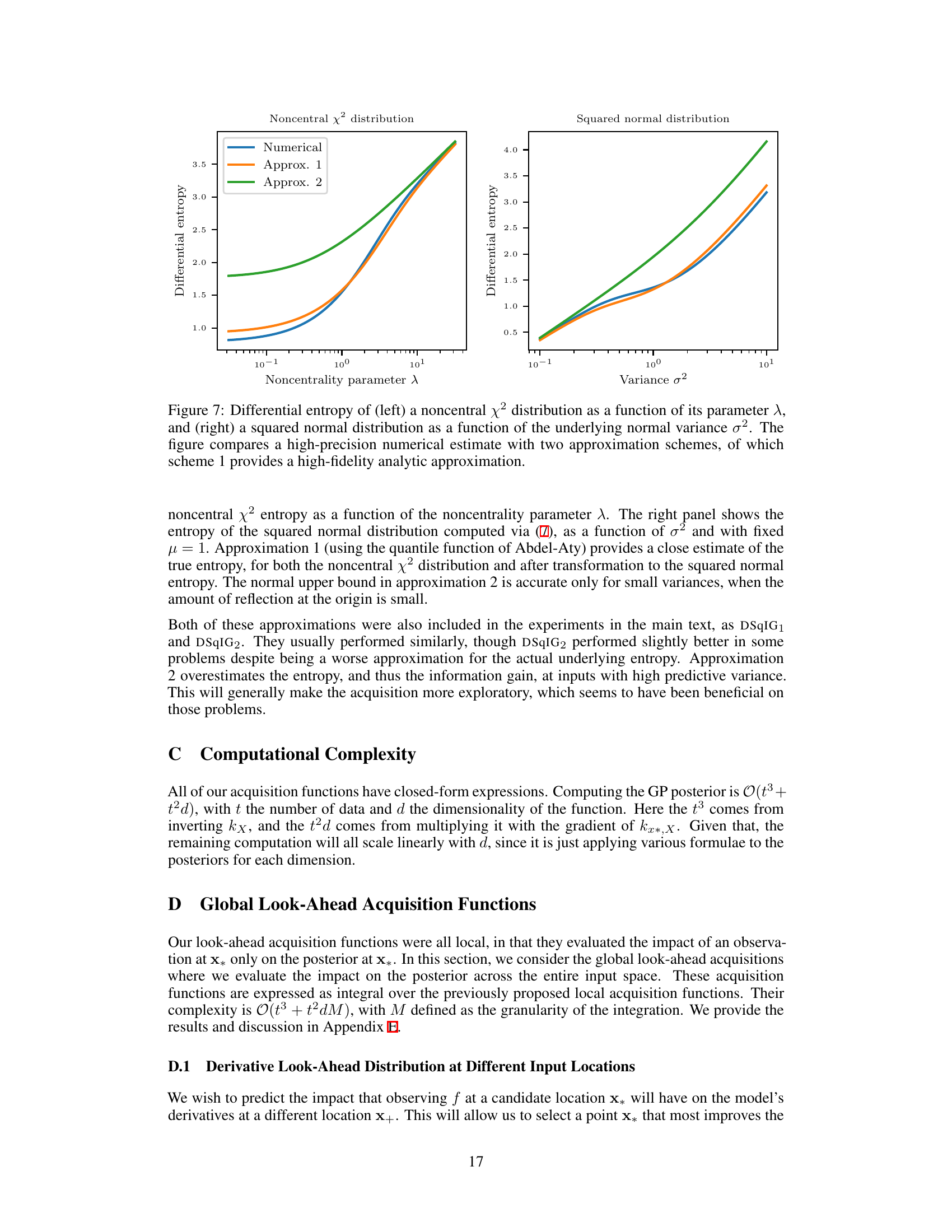

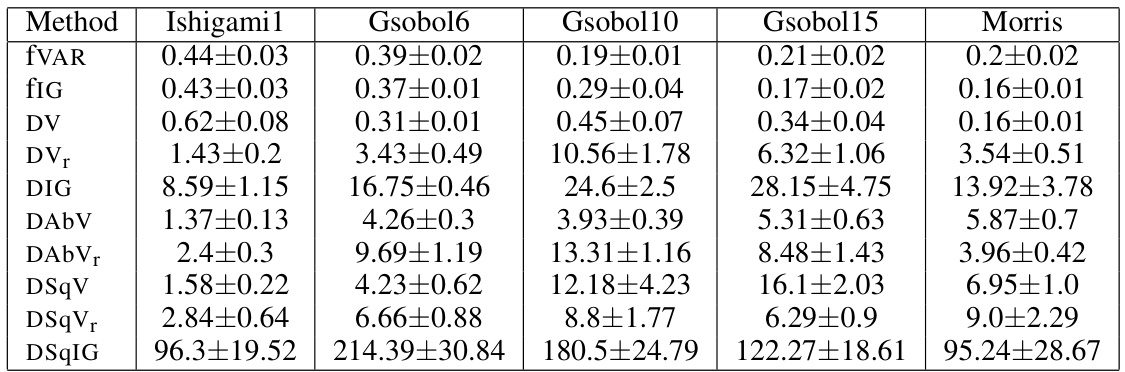

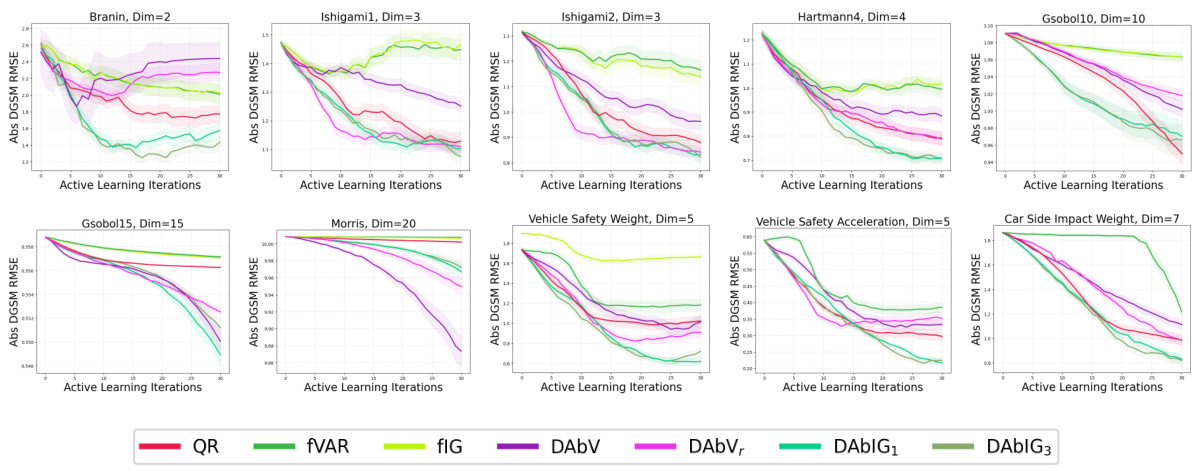

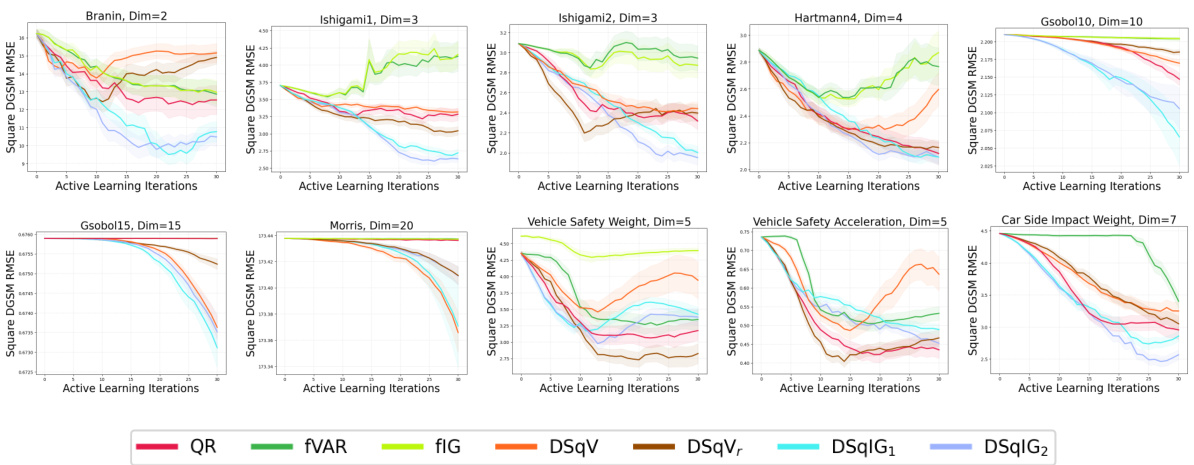

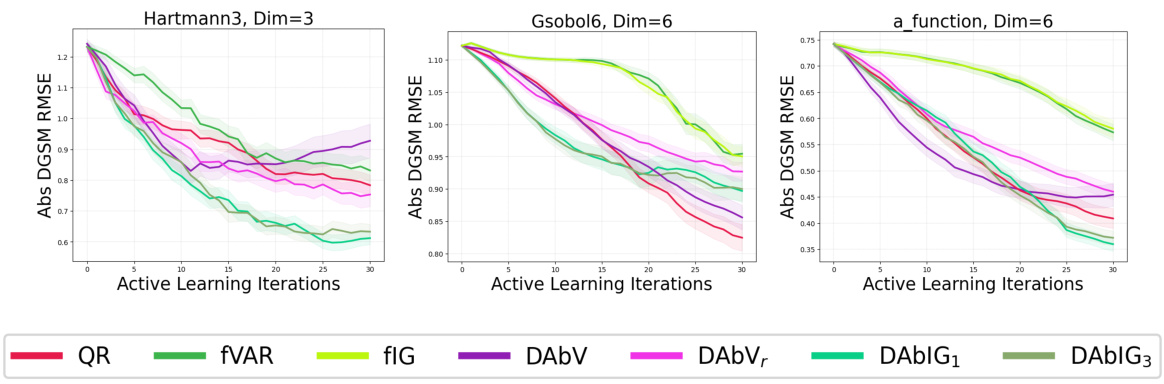

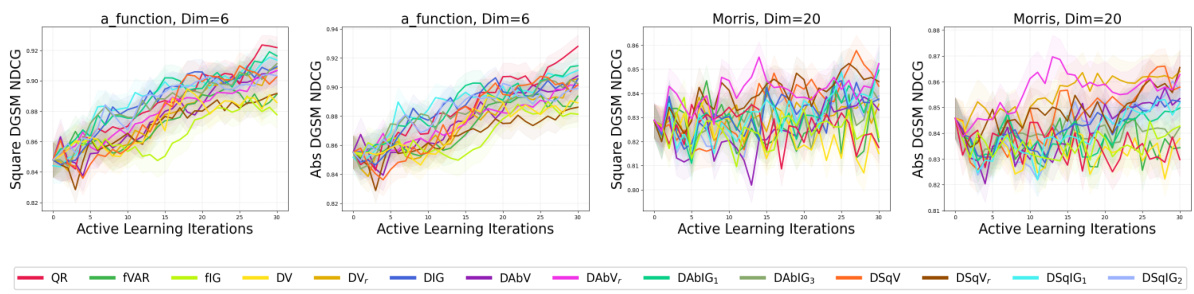

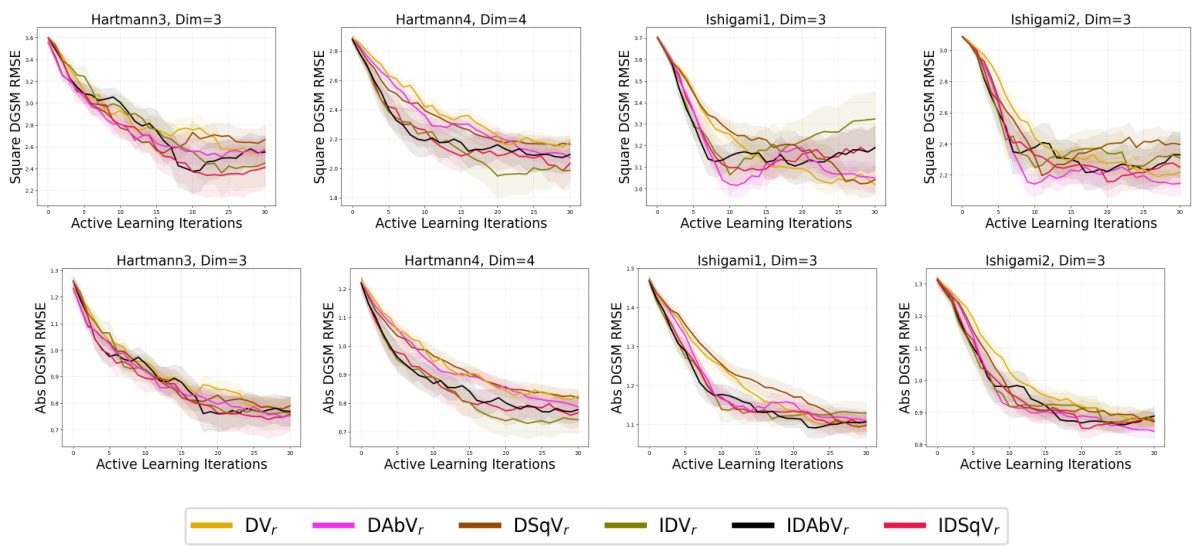

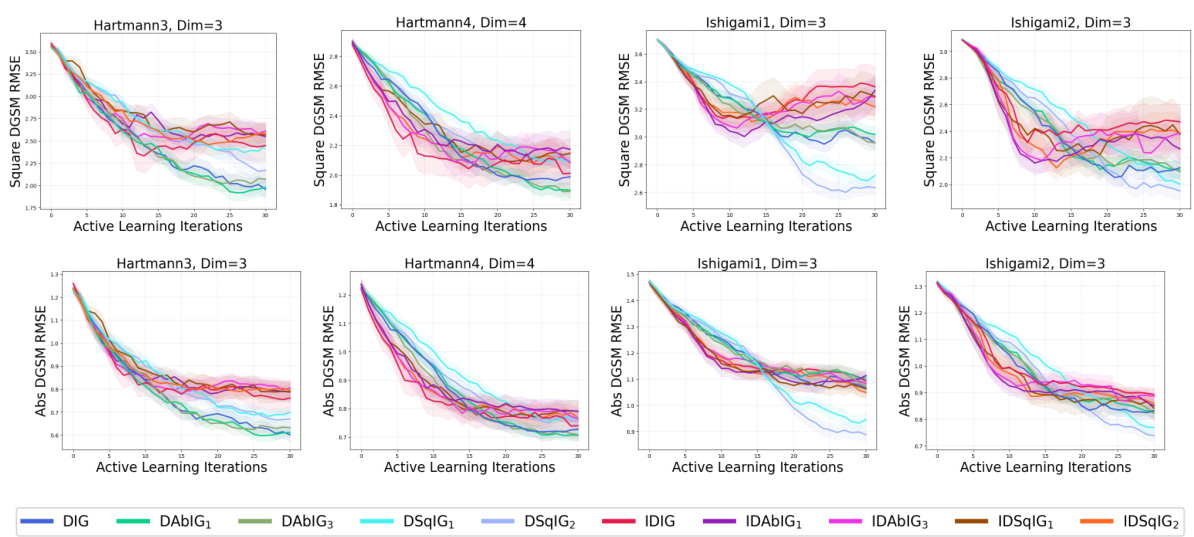

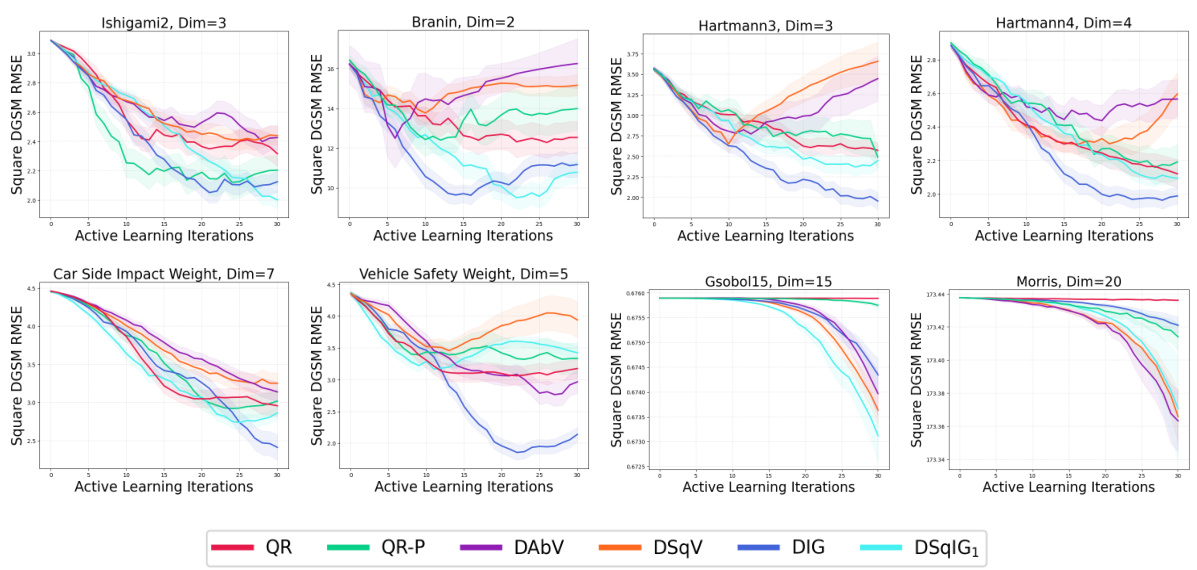

🔼 This figure displays the RMSE for estimating the derivative-based global sensitivity measure (DGSM) using different active learning methods across 10 benchmark problems. The results show that methods targeting the derivative (raw, absolute, and squared) consistently outperform space-filling methods (QR) and methods that target only the function itself (fVAR, fIG). Among the derivative-targeting methods, the information gain acquisition function generally performs best, indicating its effectiveness in efficiently estimating the DGSM with limited evaluations.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

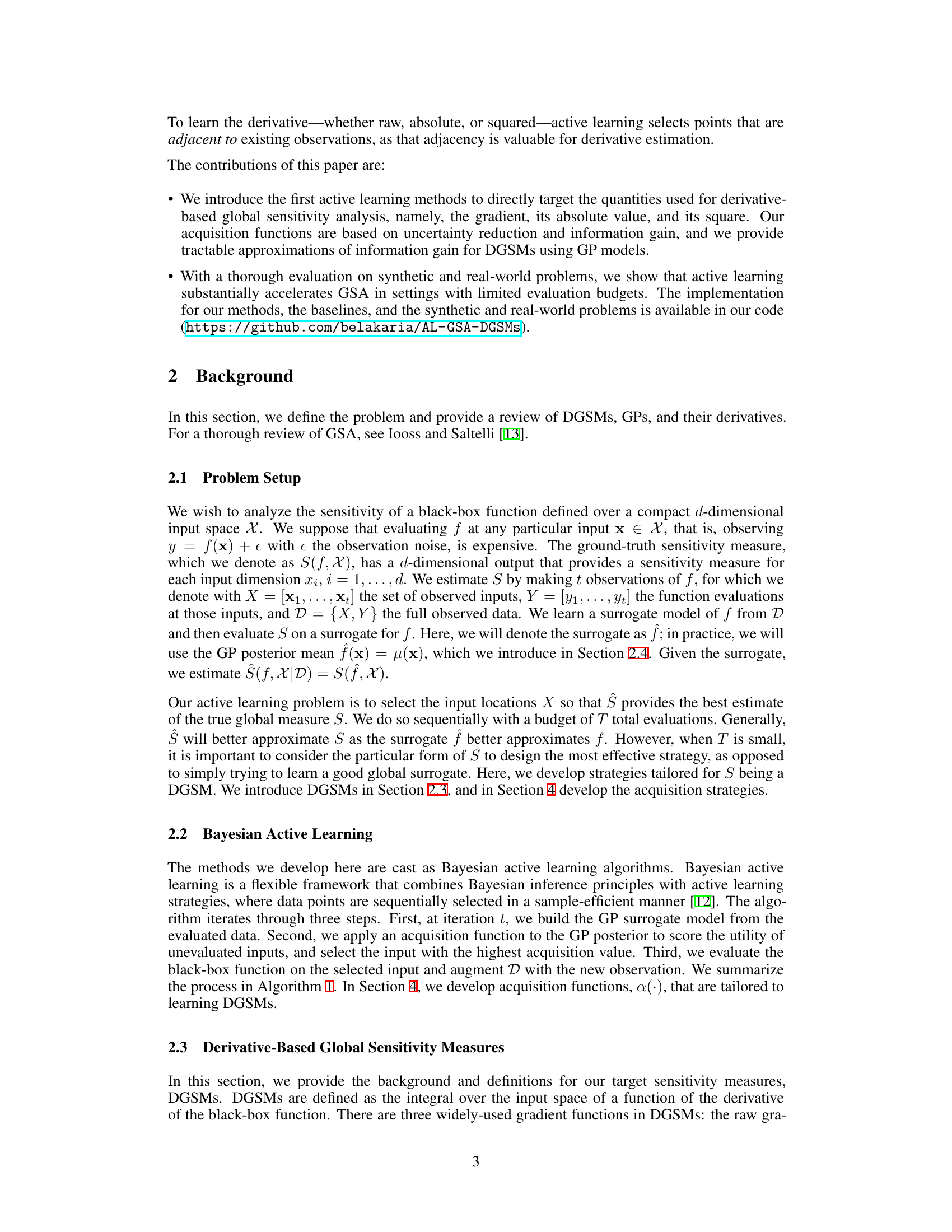

🔼 This figure shows the root mean squared error (RMSE) for estimating the absolute derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs) using different active learning acquisition functions and baselines across various benchmark problems. The results demonstrate that the proposed active learning strategies, specifically those targeting the absolute derivative quantities, consistently outperform both space-filling methods (QR) and general-purpose active learning methods that focus on the function itself (fVAR and fIG). In particular, active learning methods that utilize information gain about the absolute derivative provide superior performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: RMSE results as in Fig. 2, here for the absolute derivative acquisition functions. These also outperformed the baselines, with absolute derivative information gain generally the best.

🔼 This figure presents the root mean squared error (RMSE) for estimating derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs) across ten different test problems. The RMSE is averaged over 50 runs, with error bars representing two standard errors. The results compare several active learning methods: those targeting the raw derivative, those targeting the function itself, and a space-filling design as a baseline. The figure demonstrates that active learning methods directly targeting the derivative’s quantities significantly outperform the function-focused and space-filling approaches, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed methods. Within the derivative-targeted methods, those using derivative information gain show the best performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

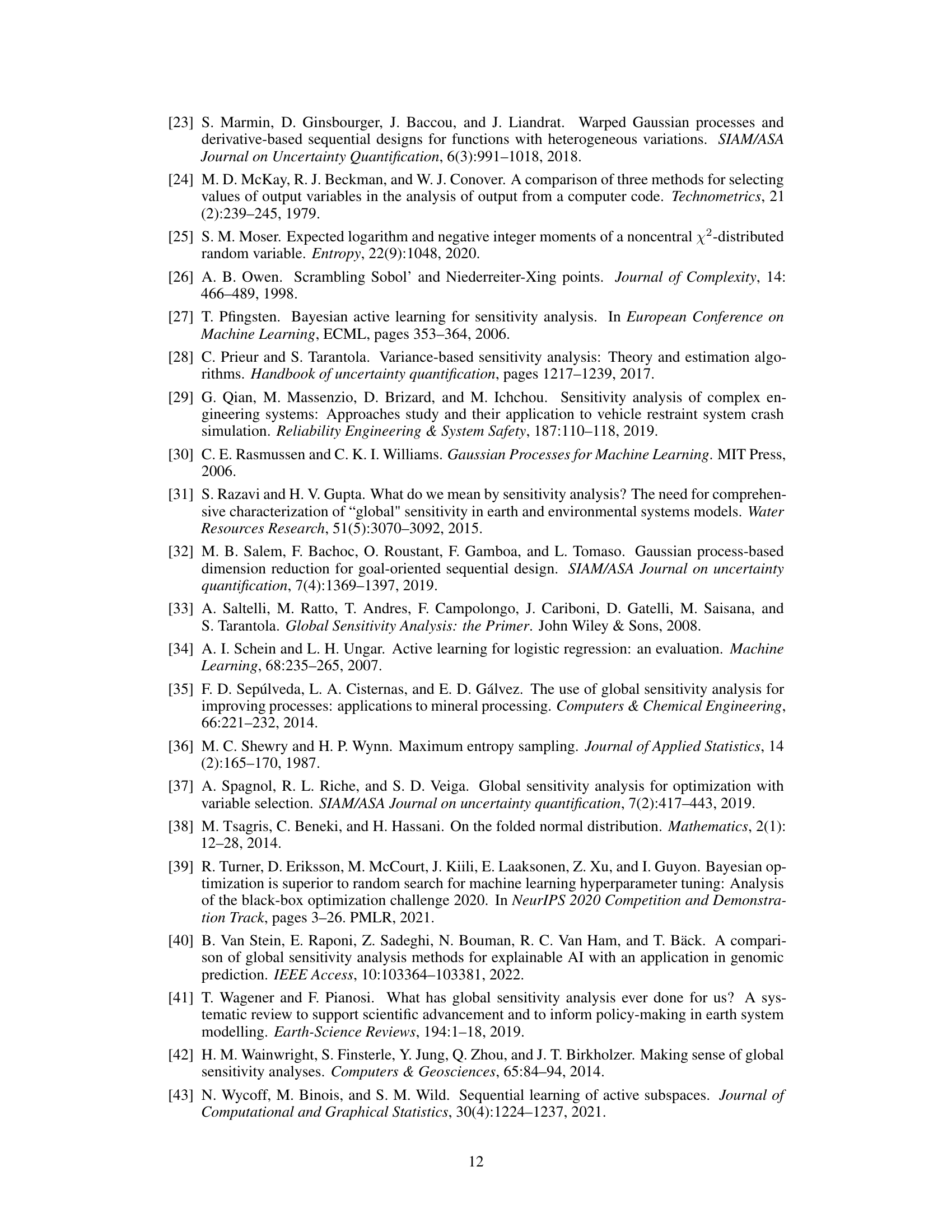

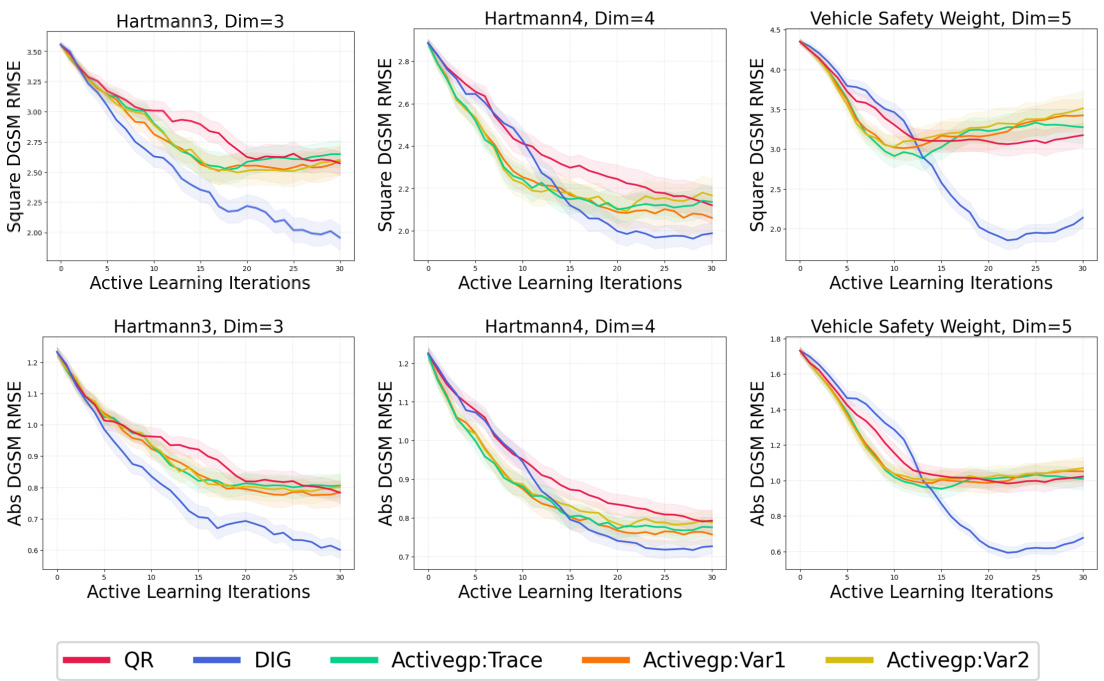

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three active subspace methods (Trace, Var1, and Var2) against the derivative information gain acquisition function (DIG), and quasirandom sequence (QR) baseline on three benchmark problems (Hartmann3, Hartmann4, and Vehicle Safety Weight). The y-axis represents the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the estimated DGSM, while the x-axis represents the number of active learning iterations. The results show that the derivative information gain acquisition function generally outperforms the other methods in terms of RMSE, indicating its higher sample efficiency and accuracy in learning DGSMs.

read the caption

Figure 5: An empirical evaluation of active subspace methods on the task of learning the square and absolute DGSM, with derivative information gain, derivative square information gain, and quasirandom as points of comparison.

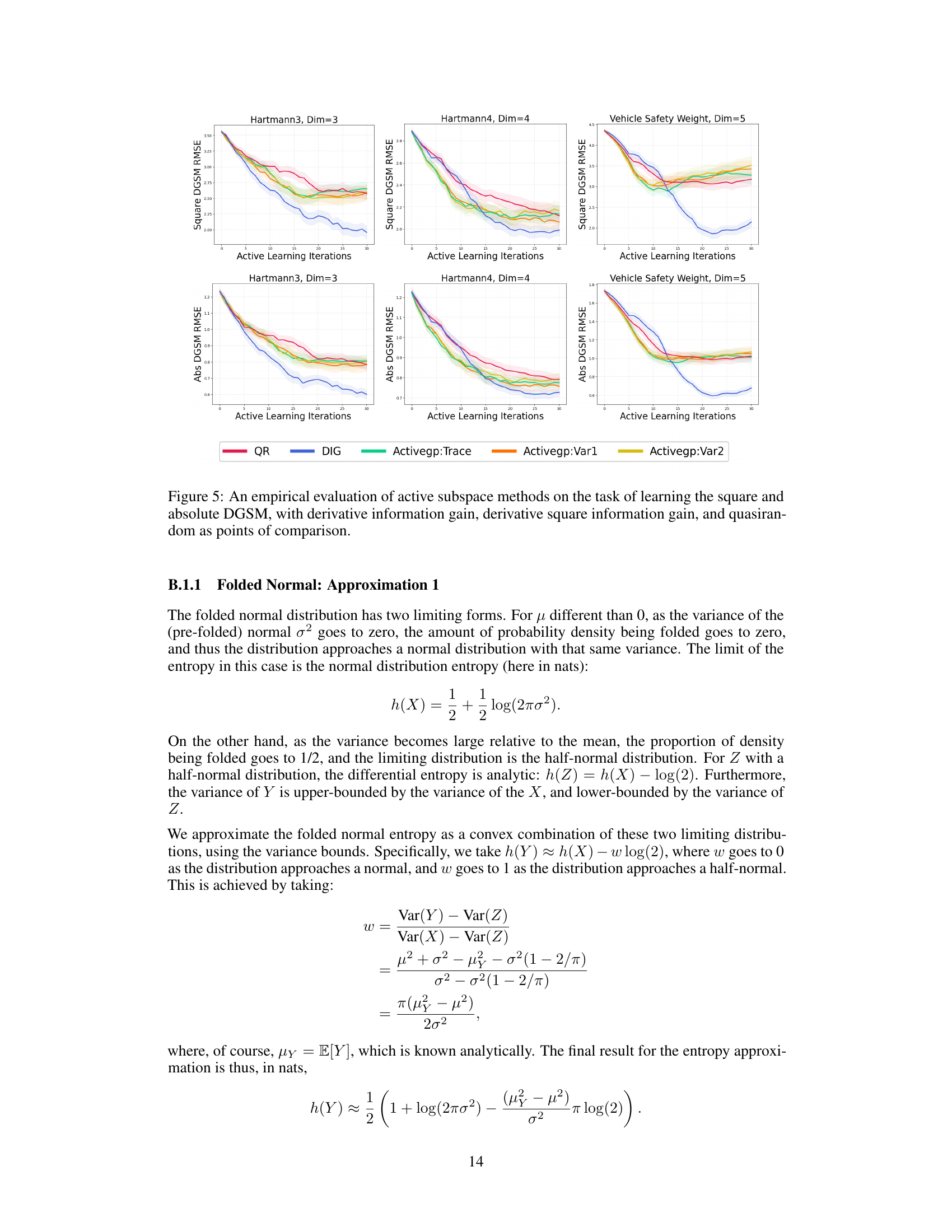

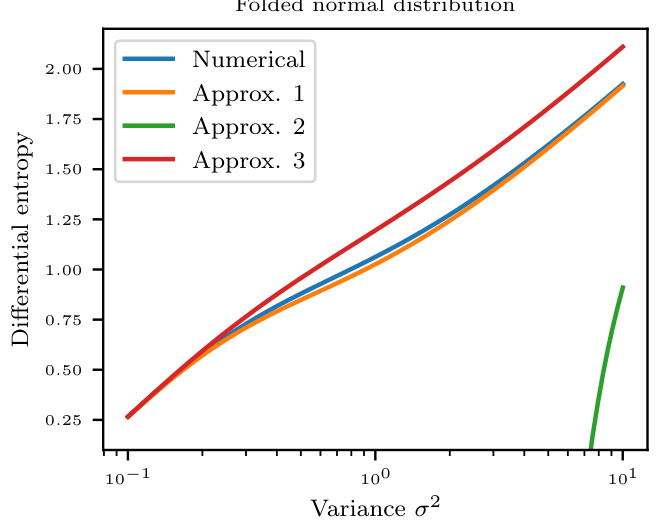

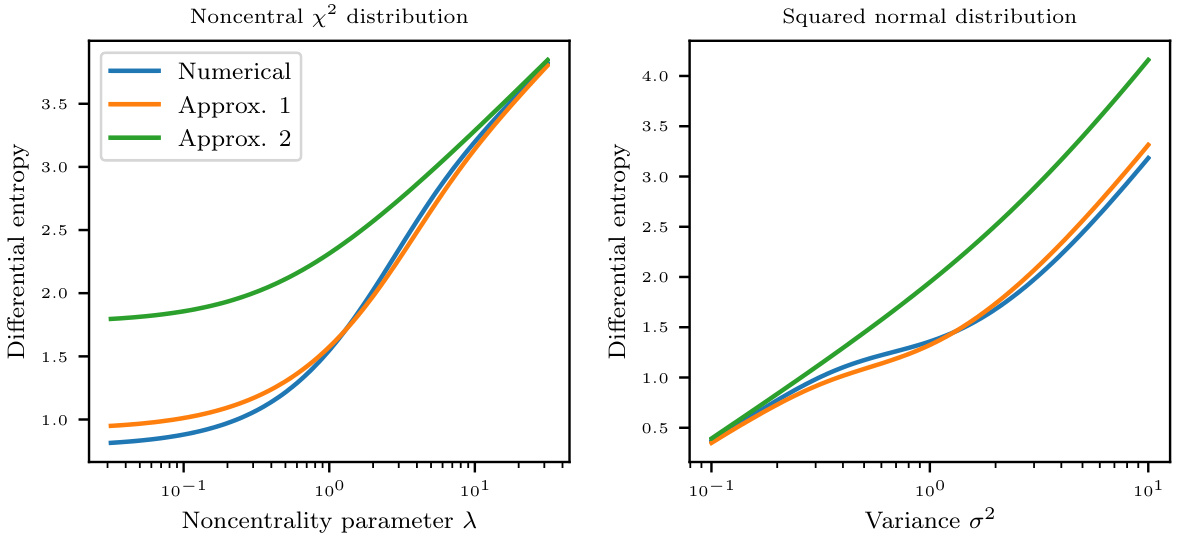

🔼 This figure compares numerical calculation of differential entropy for folded normal distribution with three approximations. The x-axis represents variance (σ²) and the y-axis represents differential entropy. Three approximations and the numerical result are plotted for comparison. Approximation 1 shows high fidelity to numerical result. Approximation 2 shows instability and Approximation 3 shows a reasonable approximation, but not as precise as Approximation 1.

read the caption

Figure 6: Differential entropy of a folded normal distribution as a function of the underlying normal variance σ². The figure compares a high-precision numerical estimate with three approximation schemes, of which scheme 1 provides a high-fidelity analytic approximation.

🔼 The figure shows posterior distributions of the function and its derivatives given some observations and the corresponding acquisition functions for active learning. The left panel demonstrates how a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model is used to estimate the posterior distributions of the function (f), its derivative (df/dx), the absolute value of the derivative (|df/dx|), and the square of the derivative ((df/dx)²). The right panel displays the information gain of each quantity, which is used as an acquisition function for selecting the next observation point in active learning. The figure highlights that directly targeting DGSMs (derivative-based global sensitivity measures) in the acquisition function is crucial for efficient learning, as opposed to just focusing on the function’s value.

read the caption

Figure 1: (Left) Posteriors of f, df/dx, |df/dx|, and (df/dx)² are computed from a GP surrogate given six observations of f (black dots). Posteriors are shown as posterior mean (line) and 95% credible interval (shaded). (Right) Acquisition functions are computed from these posteriors, targeting f and derivative sensitivity measures. Dotted vertical lines show the maximizer. Acquisition functions that directly target DGSMs, not just f generally, are required to learn the DGSMs efficiently.

🔼 The figure shows the RMSE for learning the derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs) for 10 different test problems. It compares the performance of several active learning methods against space-filling designs and active learning methods that target learning the function itself. The results demonstrate that active learning directly targeting the derivatives significantly outperforms the other approaches, with the derivative information gain method generally achieving the best performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

🔼 This figure compares the root mean squared error (RMSE) of different active learning methods for estimating derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs). Ten different test problems were used. The results show that active learning methods which directly target the derivative consistently outperform methods which use space-filling designs or target only the function itself. Furthermore, amongst the derivative-targeting methods, the derivative information gain acquisition function generally performed best.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

🔼 The figure displays the RMSE (root mean squared error) for estimating derivative-based global sensitivity measures (DGSMs) using various active learning methods. Ten different test problems are included, each represented by a separate subplot. The RMSE values are averaged over 50 runs with error bars showing two standard deviations. The results indicate that active learning strategies focusing directly on the derivative significantly outperform space-filling designs and active learning methods that only target the function itself. Among the derivative-focused methods, those employing information gain generally produce the most accurate estimates.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

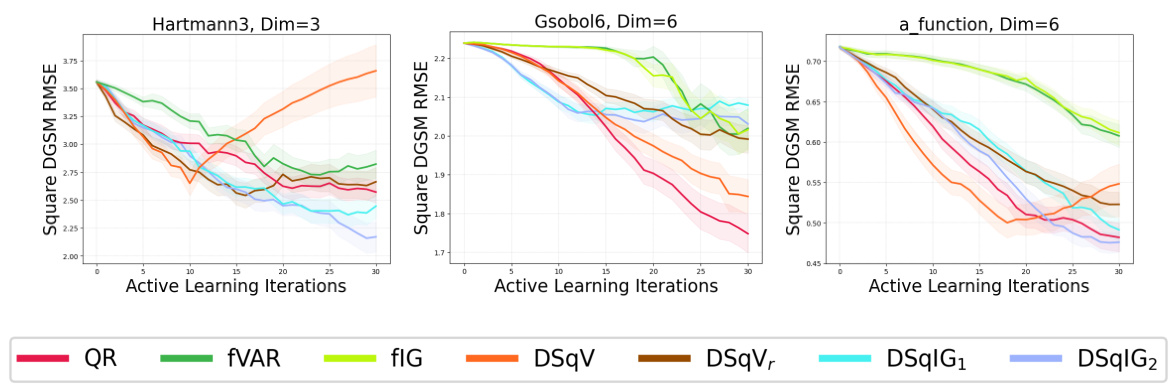

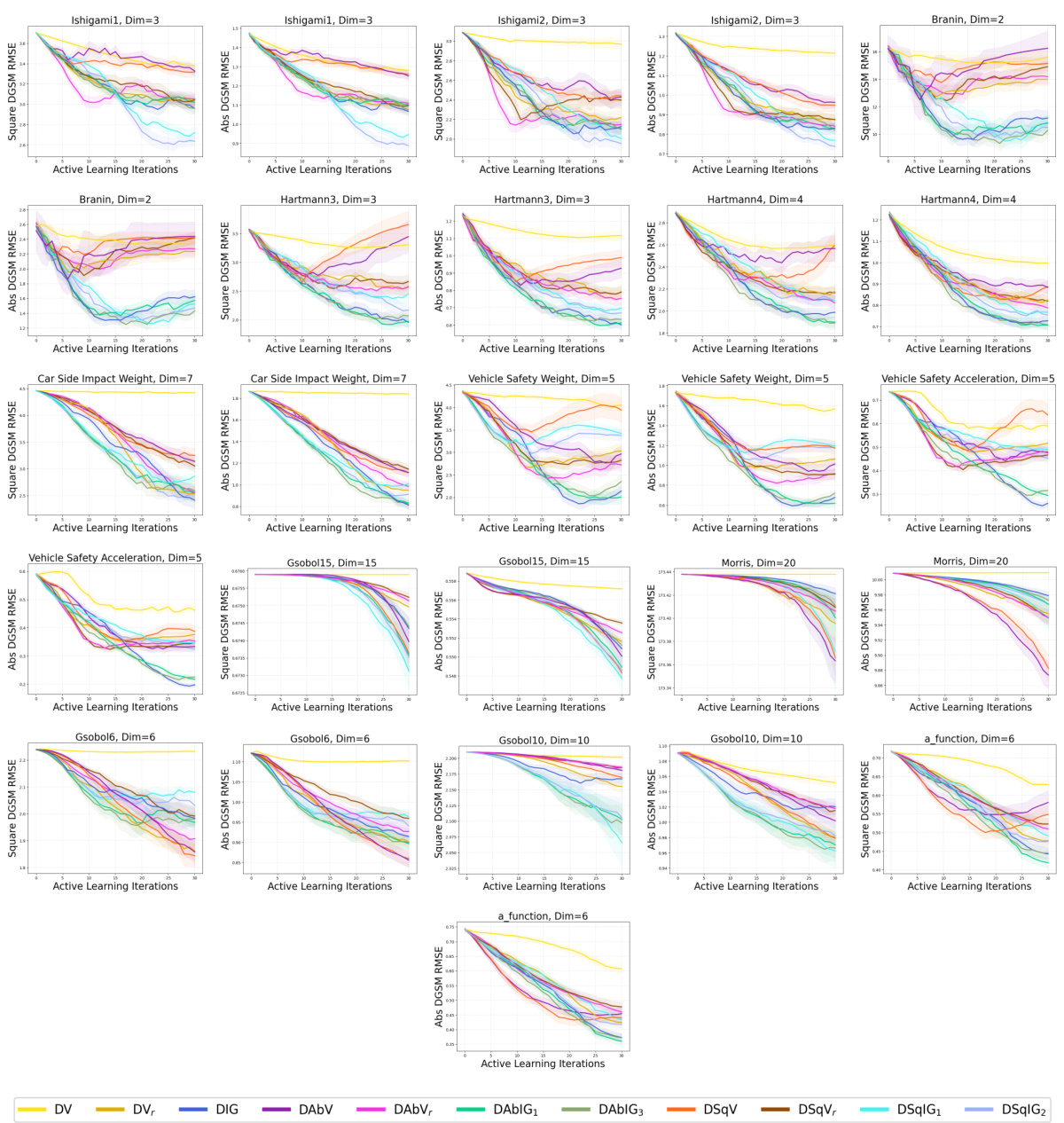

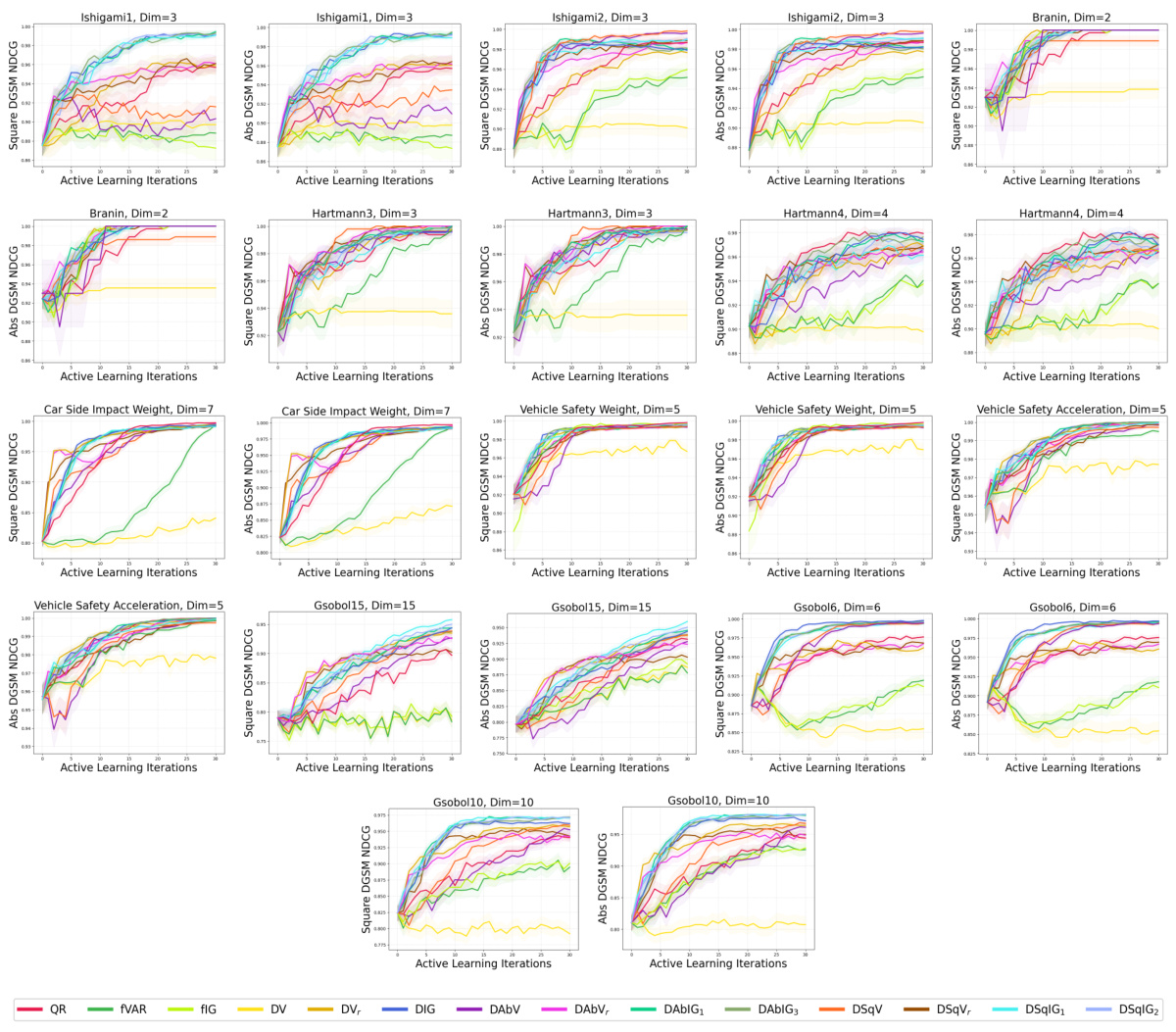

🔼 This figure shows the RMSE results for all acquisition functions (maximum variance, variance reduction, and information gain for raw, absolute, and squared derivatives) applied to all benchmark problems (Ishigami1, Ishigami2, Branin, Hartmann3, Hartmann4, Car Side Impact Weight, Vehicle Safety Weight, Vehicle Safety Acceleration, Gsobol6, Gsobol10, Gsobol15, Morris, and a-function) for both absolute and squared DGSMs. It provides a comprehensive overview of the performance of various acquisition functions across different problem settings. This figure is a superset of the results shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4, offering a more complete comparison across all the test problems.

read the caption

Figure 11: All acquisition functions evaluated on all benchmark problems for both the absolute and squared DGSMs. A superset of the results in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

🔼 The figure shows the RMSE (root mean squared error) results for learning the Derivative-based Global Sensitivity Measures (DGSMs) for ten different test problems. It compares different active learning methods that target the raw derivative, with error bars showing the standard error over 50 runs. Space-filling designs (QR) and active learning methods targeting the function f (fVAR and fIG) serve as baselines. The results demonstrate that active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperforms the baselines, with derivative information gain methods generally showing the best performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: RMSE (mean over 50 runs, two standard errors shaded) for learning the DGSM, for 10 test problems. Results are shown for active learning methods targeting the raw derivative. Active learning targeting the derivative consistently outperformed space-filling designs and active learning targeting f. Derivative information gain was generally the best-performing acquisition function.

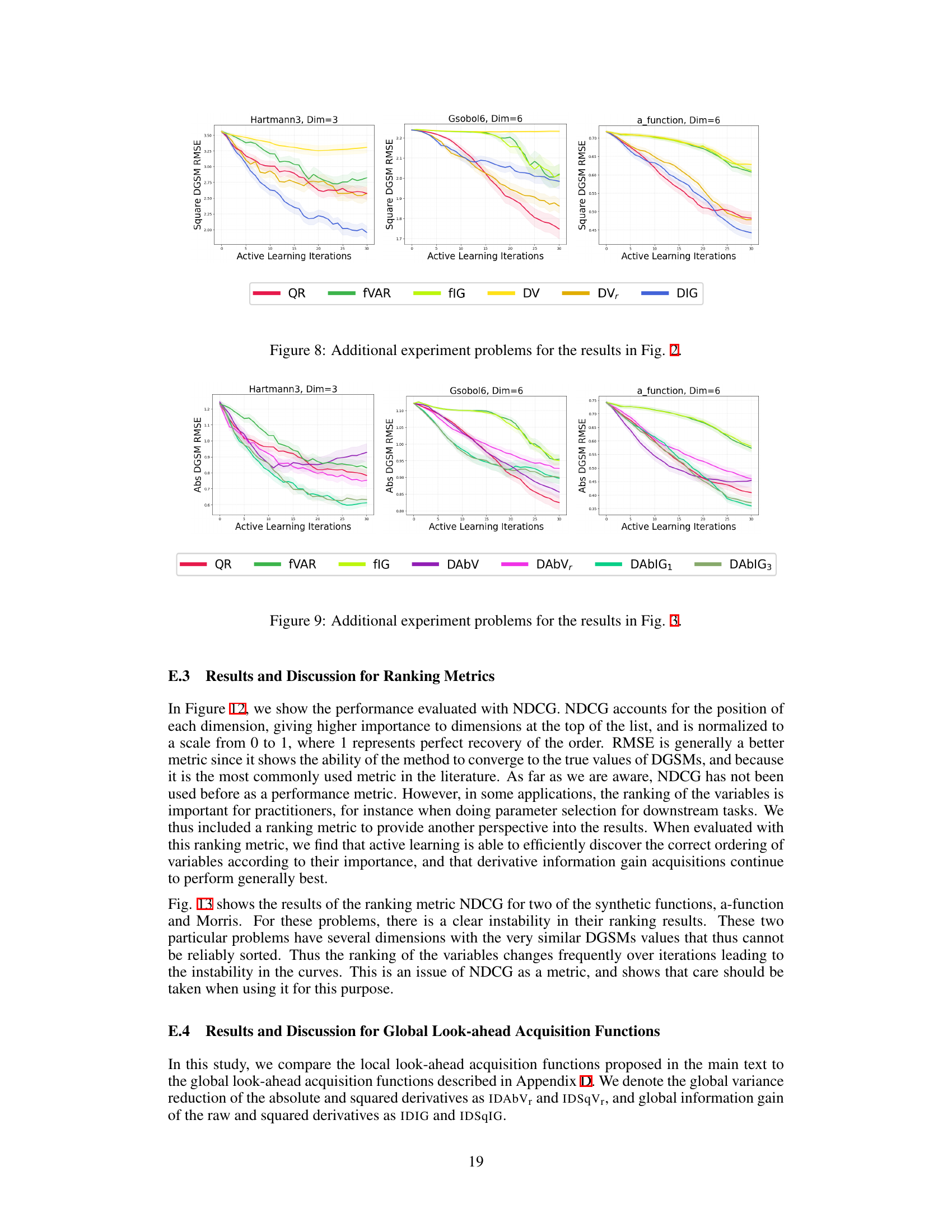

🔼 The figure presents the results of NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain), a ranking metric evaluating the ability of different methods to accurately determine the order of importance of variables for both absolute and squared DGSMs (Derivative-Based Global Sensitivity Measures). Results are shown for various synthetic and real-world datasets, comparing the performance of active learning methods (targeting raw, absolute, and squared derivatives) against space-filling designs and general active learning techniques targeting the function directly. The mean and two standard errors are calculated from 50 repeated runs of each experiment, providing a measure of the statistical reliability of the results.

read the caption

Figure 12: Synthetic and real-world experiments evaluated using NDCG. The NDCG of the square DGSMs and absolute DGSMs is reported with the mean and two standard errors of 50 repeats.

🔼 This figure shows the RMSE results for all acquisition functions (QR, fVAR, fIG, DV, DVr, DIG, DAbV, DAbVr, DAbIG1, DAbIG3, DSqV, DSqVr, DSqIG1, DSqIG2) across all benchmark problems (Branin, Hartmann3, Hartmann4, Ishigami1, Ishigami2, Gsobol6, Gsobol10, Gsobol15, Morris, Vehicle Safety Weight, Vehicle Safety Acceleration, Car Side Impact Weight) for both the absolute and squared DGSMs. It is a more comprehensive version of Figures 2, 3, and 4, showing all methods and problems together. Each line represents the mean RMSE across 50 trials, with shaded areas indicating the standard error of the mean.

read the caption

Figure 11: All acquisition functions evaluated on all benchmark problems for both the absolute and squared DGSMs. A superset of the results in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

🔼 This figure shows the RMSE results for all acquisition functions (maximum variance, variance reduction, information gain) targeting the raw, absolute, and squared derivatives, as well as the baselines (QR, fVAR, fIG), across all benchmark problems (synthetic and real-world). It provides a comprehensive comparison of all methods, expanding upon the results presented separately in Figures 2, 3, and 4.

read the caption

Figure 11: All acquisition functions evaluated on all benchmark problems for both the absolute and squared DGSMs. A superset of the results in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

🔼 This figure is a comprehensive visualization of the performance of various acquisition functions (QR, QR-P, DAbV, DSqV, DIG, DAbIG1, DAbIG3, DSqIG1, DSqIG2) across a range of benchmark problems for both absolute and squared DGSMs. It expands upon the results presented individually in Figures 2, 3, and 4, providing a unified view of their performance across all problems. The y-axis represents the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) of DGSM estimation, while the x-axis shows the number of active learning iterations. This allows for a direct comparison of the effectiveness of each acquisition function in learning DGSMs across different problem complexities and characteristics.

read the caption

Figure 11: All acquisition functions evaluated on all benchmark problems for both the absolute and squared DGSMs. A superset of the results in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

Full paper#