TL;DR#

Current molecular docking methods, while improving, suffer from limitations. They often neglect protein side-chain structures, struggle with large binding pockets, and produce unrealistic docking poses. Traditional methods are computationally expensive, while geometric deep learning methods lack physical validity or are tailored for specific docking scenarios.

DeltaDock addresses these challenges with a two-stage framework: pocket prediction via contrastive learning and site-specific docking through bi-level iterative refinement. This approach significantly improves accuracy and physical reliability, surpassing previous state-of-the-art models by a substantial margin. The innovative pocket-ligand alignment method enhances pocket prediction, while bi-level refinement ensures physically valid results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in molecular docking and drug discovery due to its significant advancements in accuracy and efficiency. DeltaDock’s unified framework tackles limitations of existing methods, providing a highly reliable approach for both blind and site-specific docking. This opens avenues for more effective drug design and understanding protein-ligand interactions, leading to faster and more precise drug development.

Visual Insights#

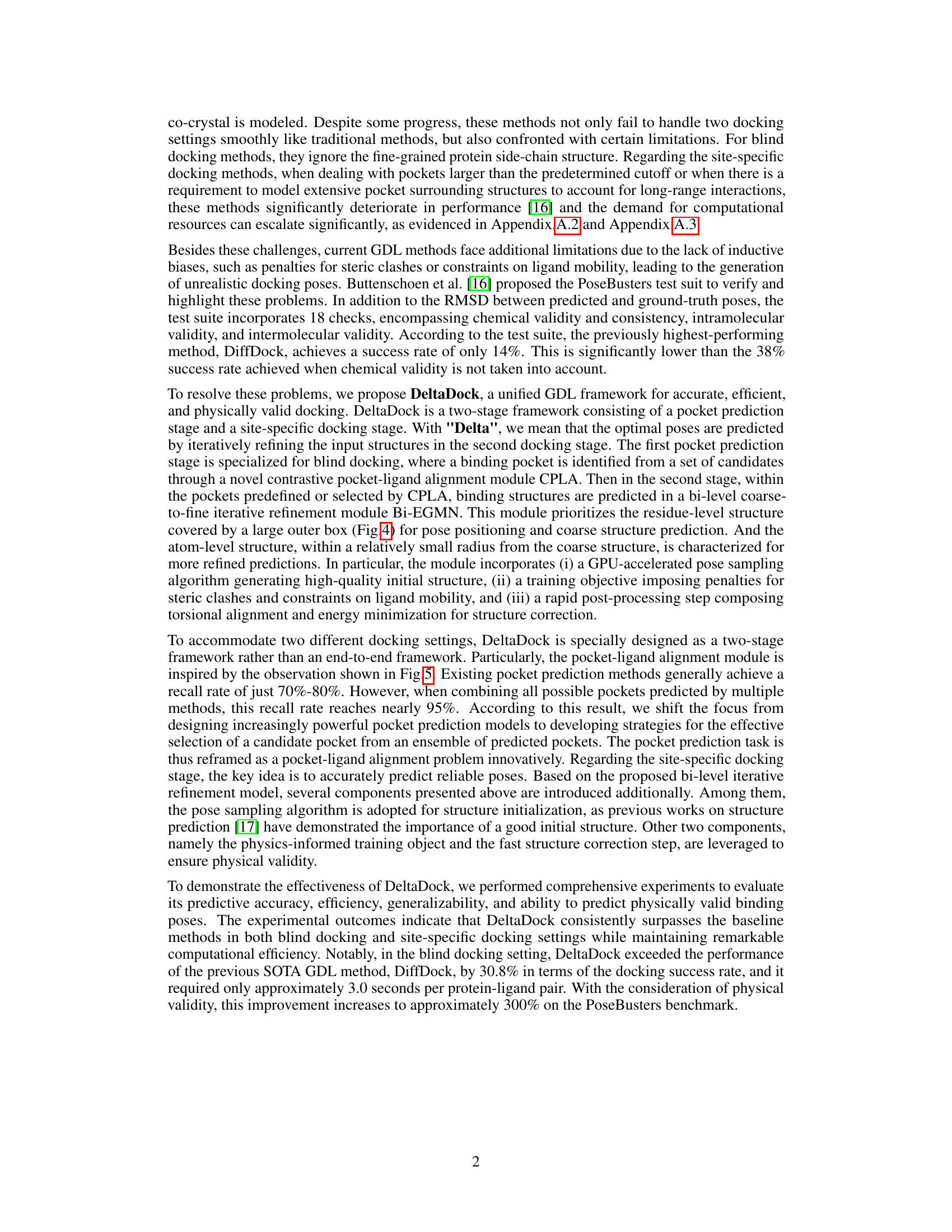

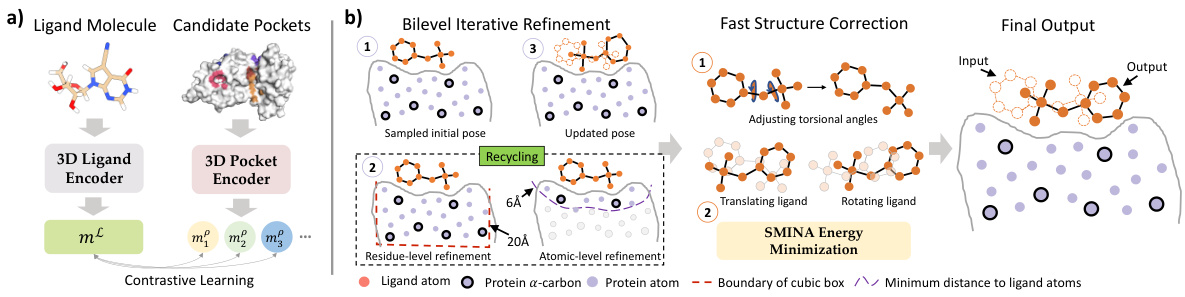

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main modules of the DeltaDock framework: CPLA (pocket-ligand alignment) and Bi-EGMN (bi-level iterative refinement). CPLA uses contrastive learning to identify the best binding pocket, while Bi-EGMN refines the initial pose through a two-stage iterative process, incorporating physical constraints to ensure realistic binding pose predictions.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of DeltaDock's two modules. (a) The pocket-ligand alignment module CPLA. Contrastive learning is adopted to maximize the correspondence between target pocket and ligand embeddings for training. During inference, the pocket with the highest similarity of the ligand is selected. (b) The bi-level iterative refinement module Bi-EGMN. Initialized with a high-quality sampled pose, the module first performs a coarse-to-fine iterative refinement. This process generates progressively refined ligand poses utilizing a recycling strategy. To guarantee the physical plausibility of the predicted poses, a two-step fast structure correction is subsequently applied. This correction involves torsion angle alignment followed by energy minimization based on the SMINA.

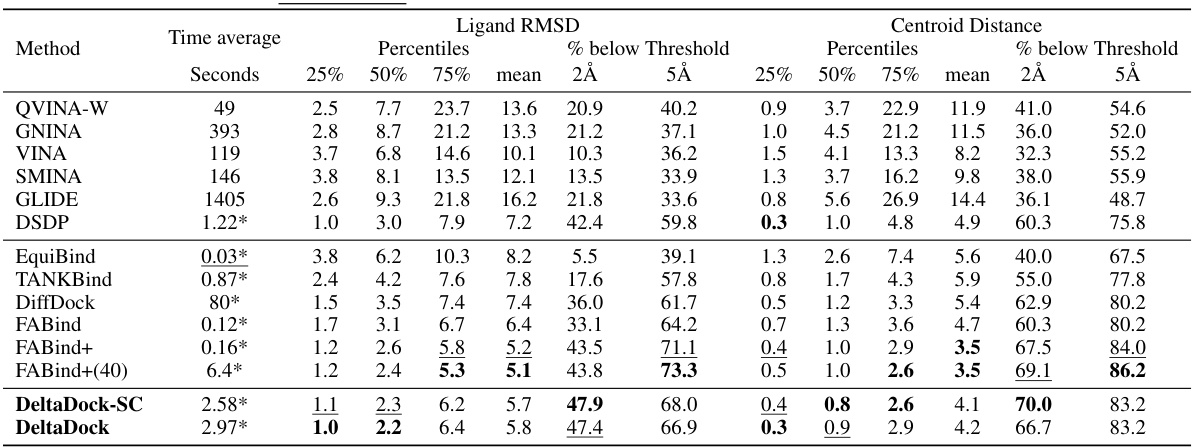

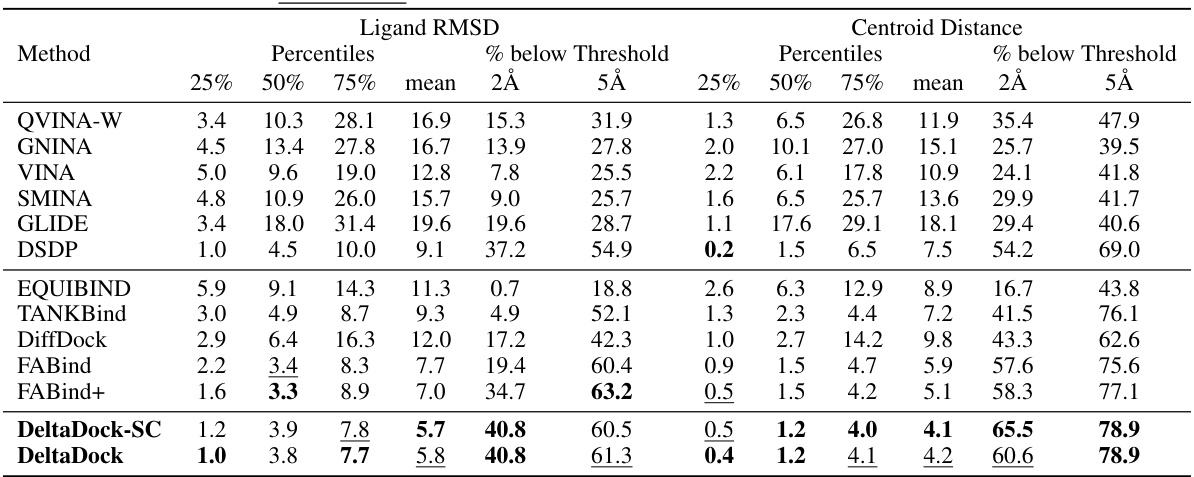

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments on the PDBbind dataset, comparing DeltaDock with several other methods. It shows the performance of different methods in terms of RMSD and centroid distance, success rate, and computation time. Variations of DeltaDock (with and without fast structure correction and high-quality initial poses) are included for comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

In-depth insights#

Unified Docking#

The concept of “Unified Docking” in molecular modeling suggests a framework capable of handling diverse docking scenarios, eliminating the need for specialized algorithms for blind or site-specific docking. A unified approach is highly desirable because it simplifies the workflow, reduces computational demands, and improves the overall efficiency and reliability of the docking process. Success hinges on a system that accurately predicts binding pockets in the blind setting and performs refined site-specific docking within those predicted pockets or those provided a priori. Such a system would improve docking success rates, especially in challenging scenarios like large or flexible binding pockets. A key challenge would be creating a robust algorithm that balances speed and accuracy across these varied situations, potentially using a combination of techniques such as geometric deep learning for global searching and more traditional methods for refined local optimization. The overall goal is a more versatile and user-friendly docking method, readily applicable to diverse molecular interactions without requiring manual adjustments or separate algorithms.

Pocket Alignment#

Pocket alignment in molecular docking presents a crucial challenge, impacting the accuracy and efficiency of ligand binding pose prediction. Aligning the ligand to the correct pocket is paramount, especially in blind docking scenarios where the binding site is unknown. Effective pocket alignment methods must consider various factors, such as the shape and size of the pocket, the chemical properties of the ligand and surrounding residues, and the flexibility of both the ligand and the protein. Geometric deep learning (GDL) techniques offer a promising approach, but optimizing the alignment process often involves balancing speed and accuracy, which is crucial for practical applications. Contrastive learning, where the similarity between the ligand and different pockets is learned, might be used to improve the quality of alignments. Another important consideration is the handling of large or complex pockets that are often observed in practice. Multi-stage alignment strategies combining global and local refinement could be developed to address this challenge. Overall, a robust pocket alignment method is essential for advancing molecular docking and structure-based drug design.

Iterative Refinement#

Iterative refinement, in the context of molecular docking, represents a powerful strategy for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of predicted ligand binding poses. It involves a cyclical process where an initial pose prediction is iteratively improved through successive refinement steps. Each iteration leverages feedback from previous steps to guide adjustments, potentially involving adjustments to the ligand’s conformation, protein flexibility, or both. This approach contrasts with single-step methods, offering the potential for significantly better results, especially when dealing with complex protein-ligand interactions. The key advantages lie in the ability to escape local minima in the search space and achieve a more globally optimal solution. Careful consideration must be given to the refinement algorithm employed to avoid overfitting or excessive computational costs. A well-designed iterative refinement process can drastically improve the accuracy of molecular docking, leading to more confident and reliable predictions for drug discovery and design. However, challenges include the convergence speed and the risk of being trapped in undesirable local optima during the refinement process. Thus, efficient and robust refinement algorithms are critical for effective implementation.

Pose Validity#

The concept of ‘Pose Validity’ in molecular docking is crucial for assessing the reliability of predicted ligand binding poses. A physically plausible pose is not just geometrically accurate (low RMSD), but also chemically and sterically reasonable. Traditional methods often struggle to achieve this, generating poses with clashes or unrealistic conformations. The PoseBusters benchmark is particularly insightful, highlighting how geometric deep learning methods, while impressive in accuracy, often produce invalid poses. DeltaDock’s strength lies in its explicit consideration of physical validity, using penalties for steric clashes and constraints on ligand mobility during training and refinement. This approach results in significantly higher success rates on benchmarks where physical validity is considered, showcasing the importance of moving beyond geometric accuracy to a more holistic evaluation of docking predictions. The ability to produce physically reliable poses is essential for downstream applications in drug discovery and beyond, making DeltaDock’s approach especially valuable. This represents a significant step towards more reliable and trustworthy molecular docking.

Future Works#

Future work for DeltaDock could involve several key improvements. Addressing the limitations of relying on external tools for structure initialization and post-processing is crucial. This could be achieved through extensive pre-training on large datasets, potentially incorporating techniques like self-supervised learning or incorporating AlphaFold’s capabilities. Improving the handling of highly flexible ligands and larger, more complex binding pockets remains a challenge that warrants further investigation. Exploring different graph neural network architectures or incorporating enhanced message-passing mechanisms might offer solutions. Additionally, the DeltaDock framework’s performance in diverse docking scenarios could be further enhanced. Testing on larger and more diverse datasets, including those with more challenging protein structures and varying ligand properties is warranted to better assess the framework’s generalizability and robustness. Finally, integrating DeltaDock into a complete drug discovery workflow will be important, including steps for virtual screening, lead optimization, and ADMET prediction. This would involve collaborations with experimentalists to validate predictions and further refine the framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

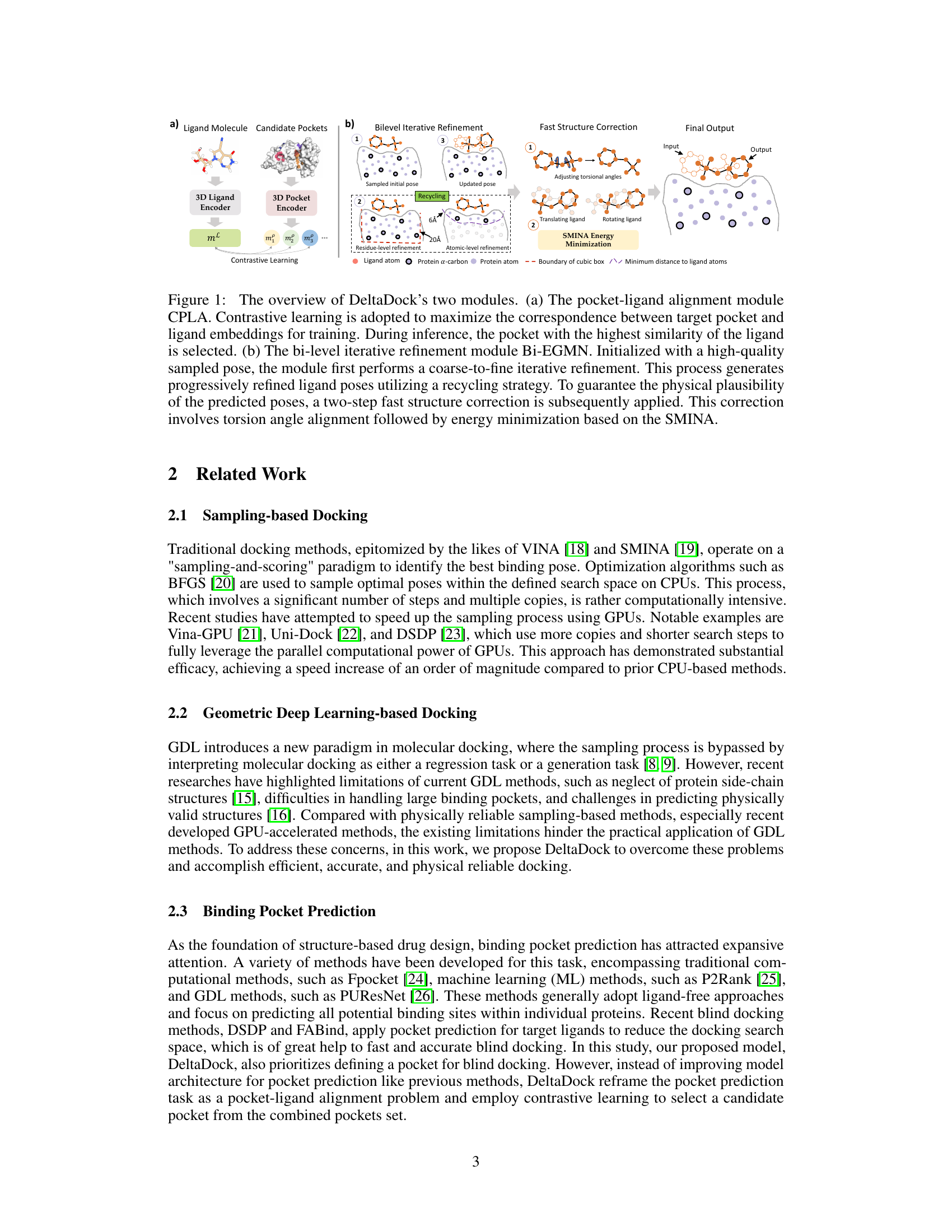

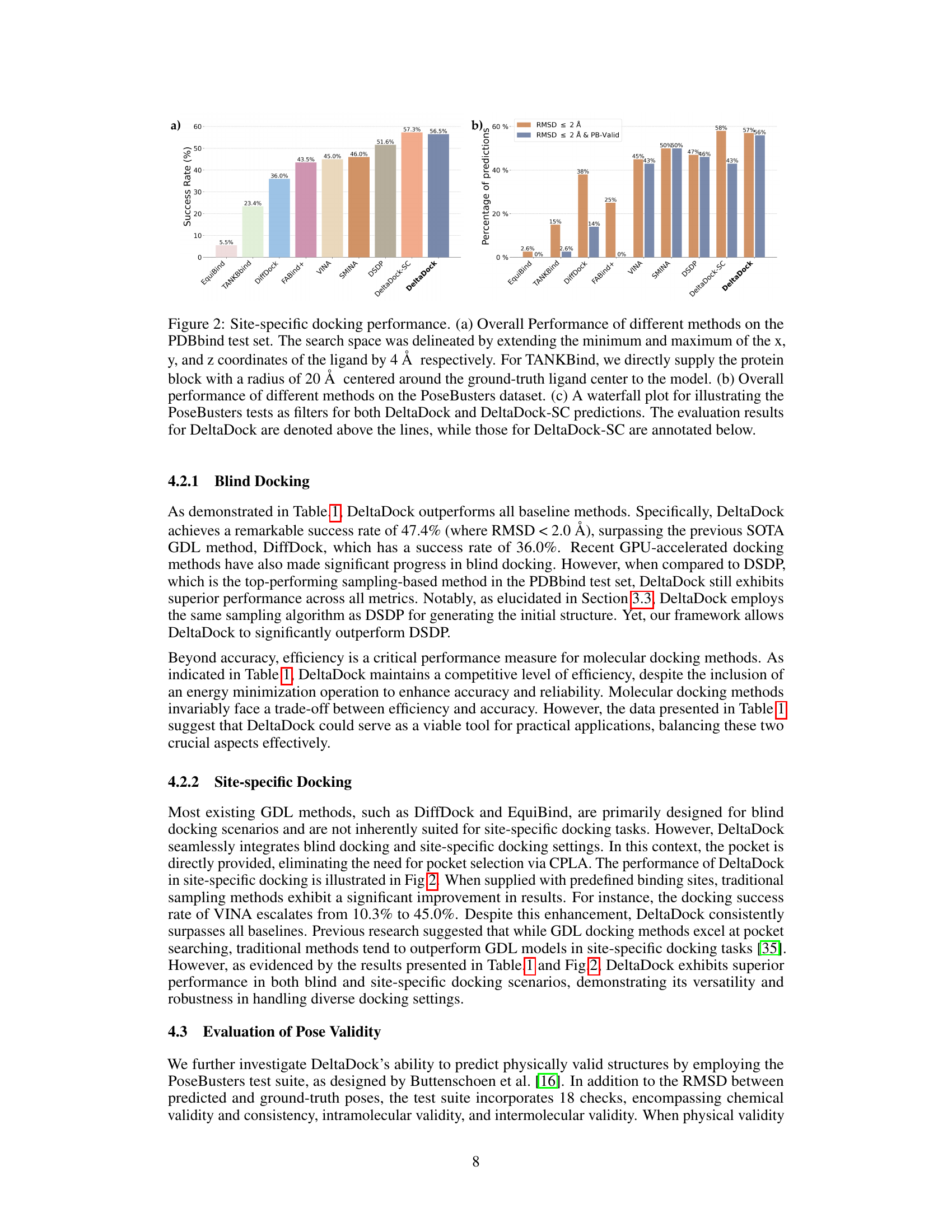

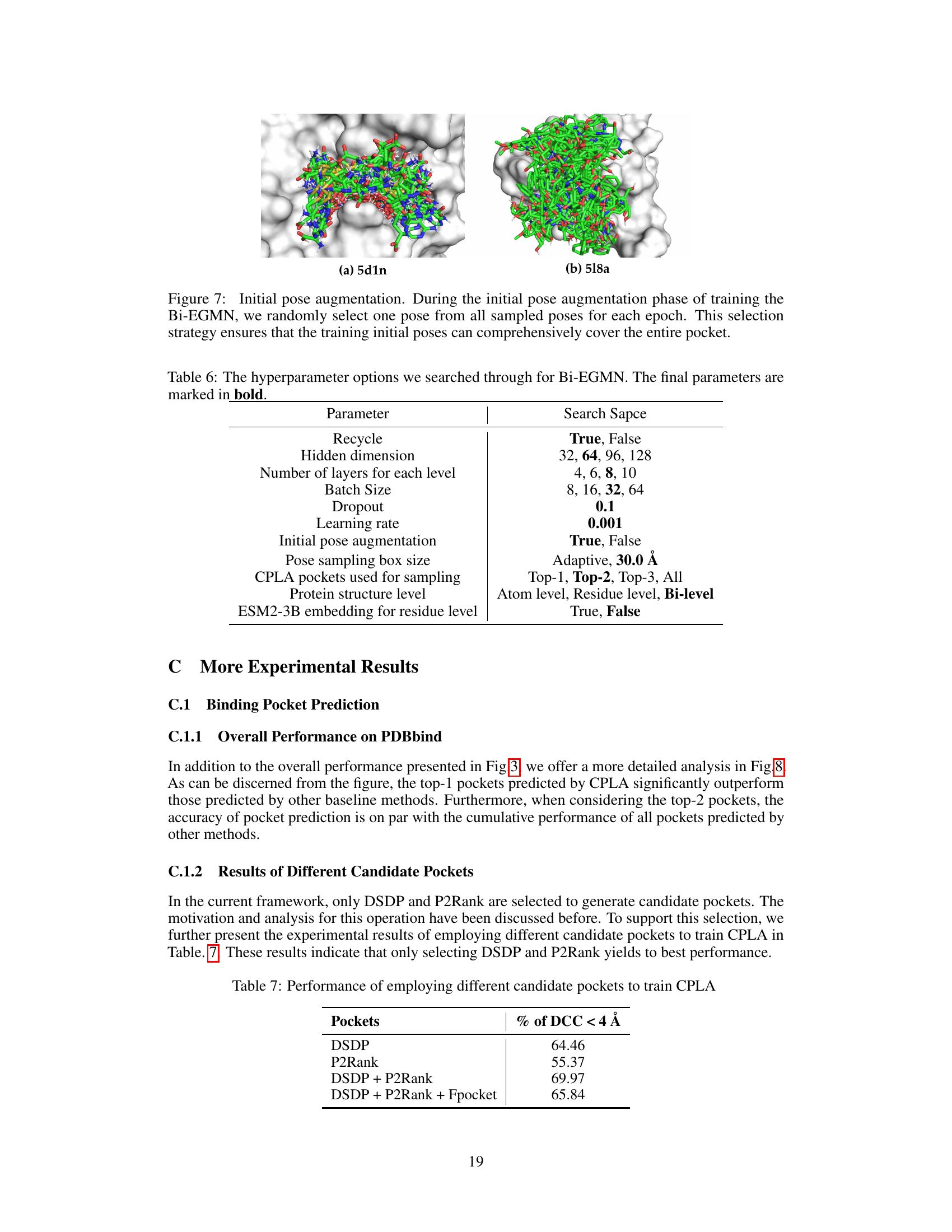

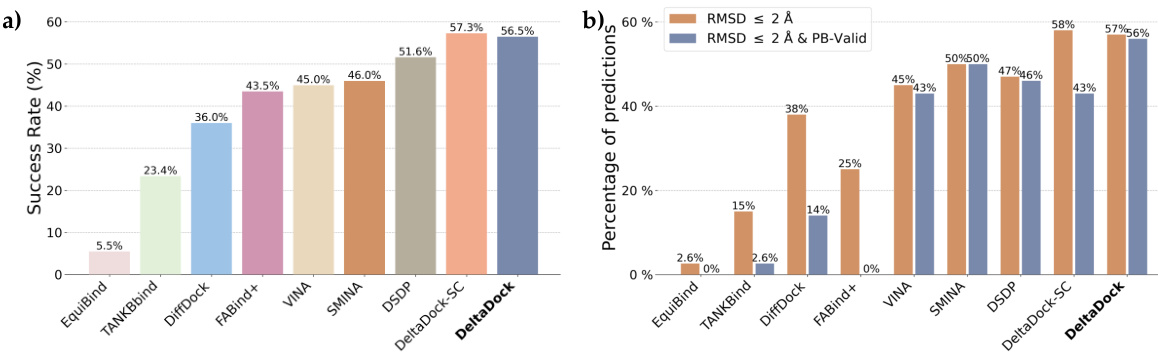

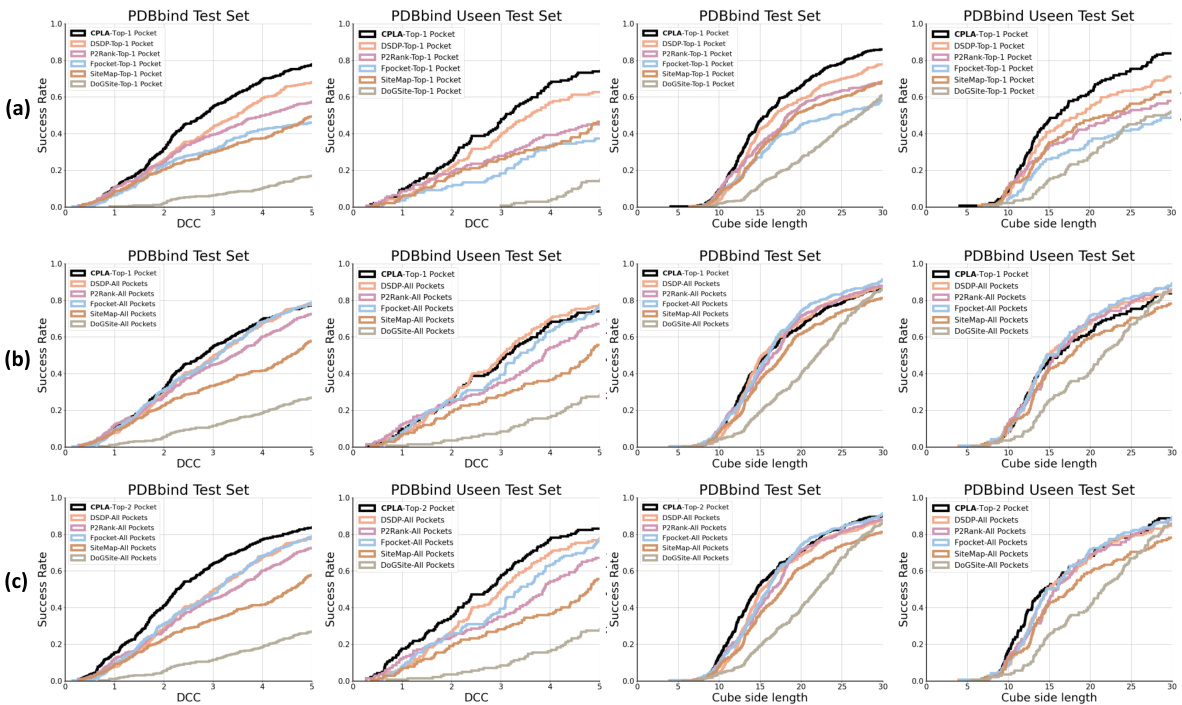

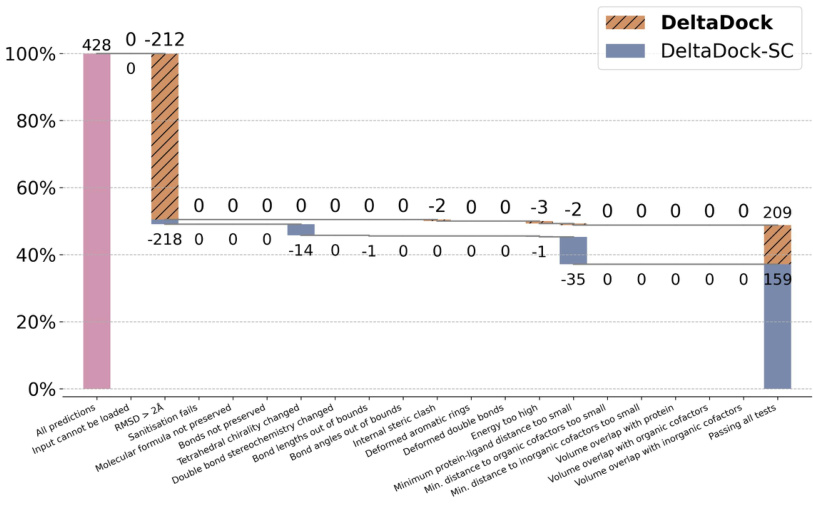

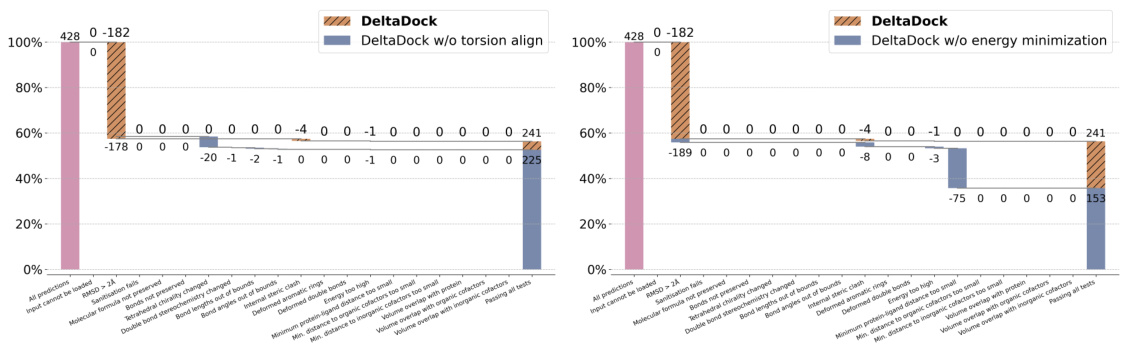

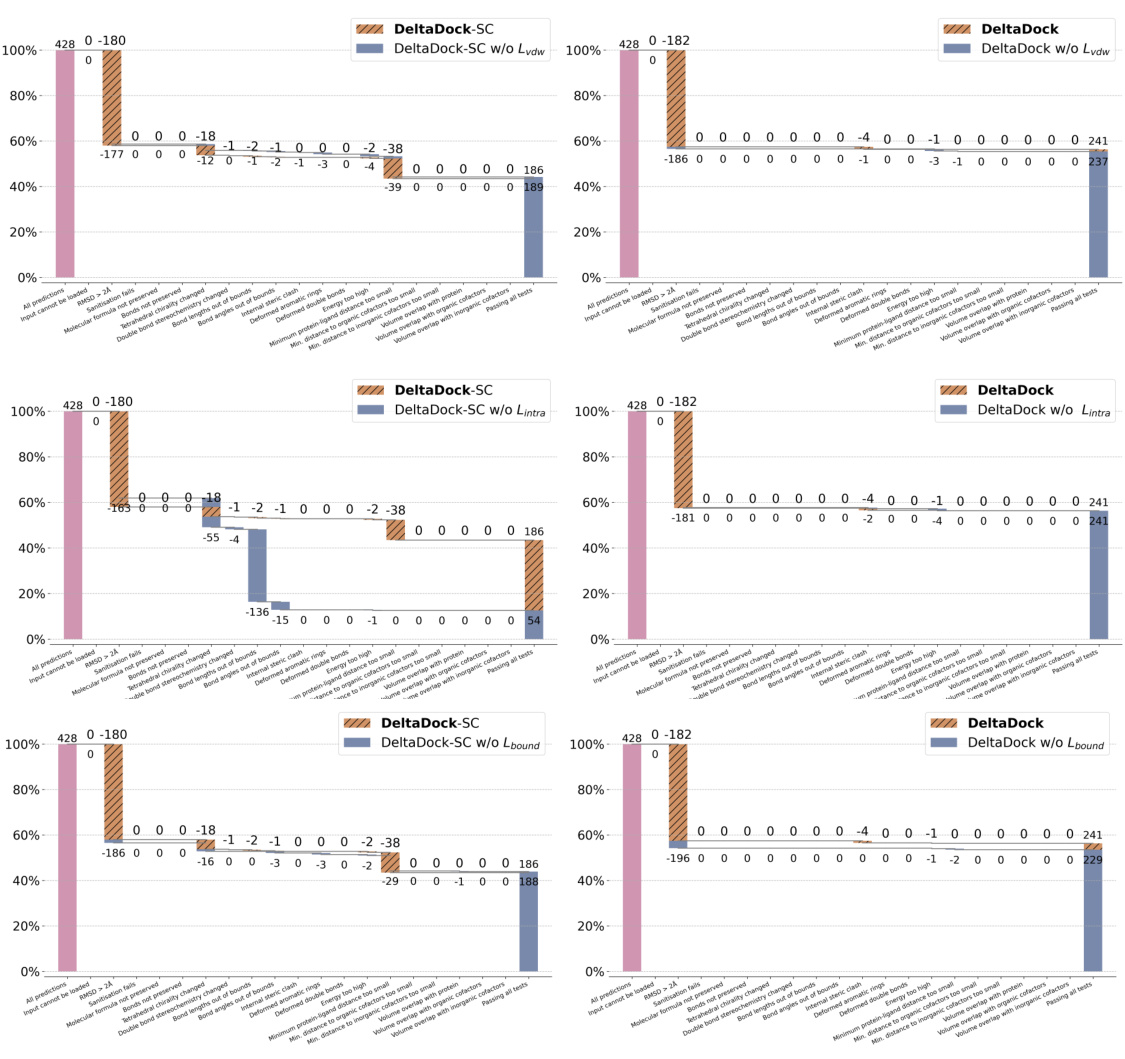

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different molecular docking methods on two datasets: PDBbind and PoseBusters. Panel (a) shows the overall performance of several methods on the PDBbind test set for site-specific docking, highlighting DeltaDock’s superior performance. Panel (b) displays the success rate of the methods according to RMSD and also considering the physical validity of the poses using the PoseBusters benchmark. Panel (c) breaks down the results of the PoseBusters benchmark further, showing how the various criteria of the benchmark affect the accuracy of the two DeltaDock variants (with and without structure correction).

read the caption

Figure 2: Site-specific docking performance. (a) Overall Performance of different methods on the PDBbind test set. The search space was delineated by extending the minimum and maximum of the x, y, and z coordinates of the ligand by 4 Å respectively. For TANKBind, we directly supply the protein block with a radius of 20 Å centered around the ground-truth ligand center to the model. (b) Overall performance of different methods on the PoseBusters dataset. (c) A waterfall plot for illustrating the PoseBusters tests as filters for both DeltaDock and DeltaDock-SC predictions. The evaluation results for DeltaDock are denoted above the lines, while those for DeltaDock-SC are annotated below.

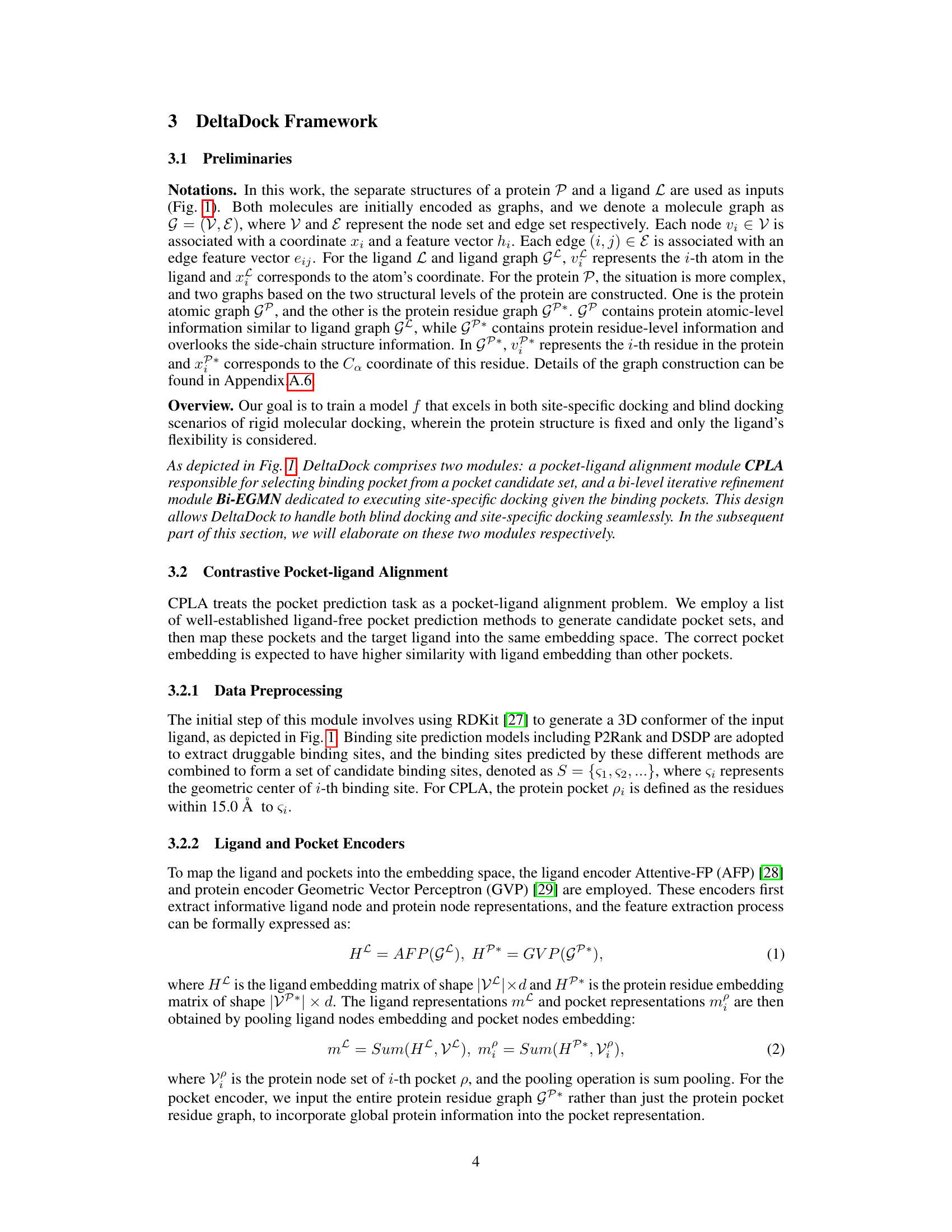

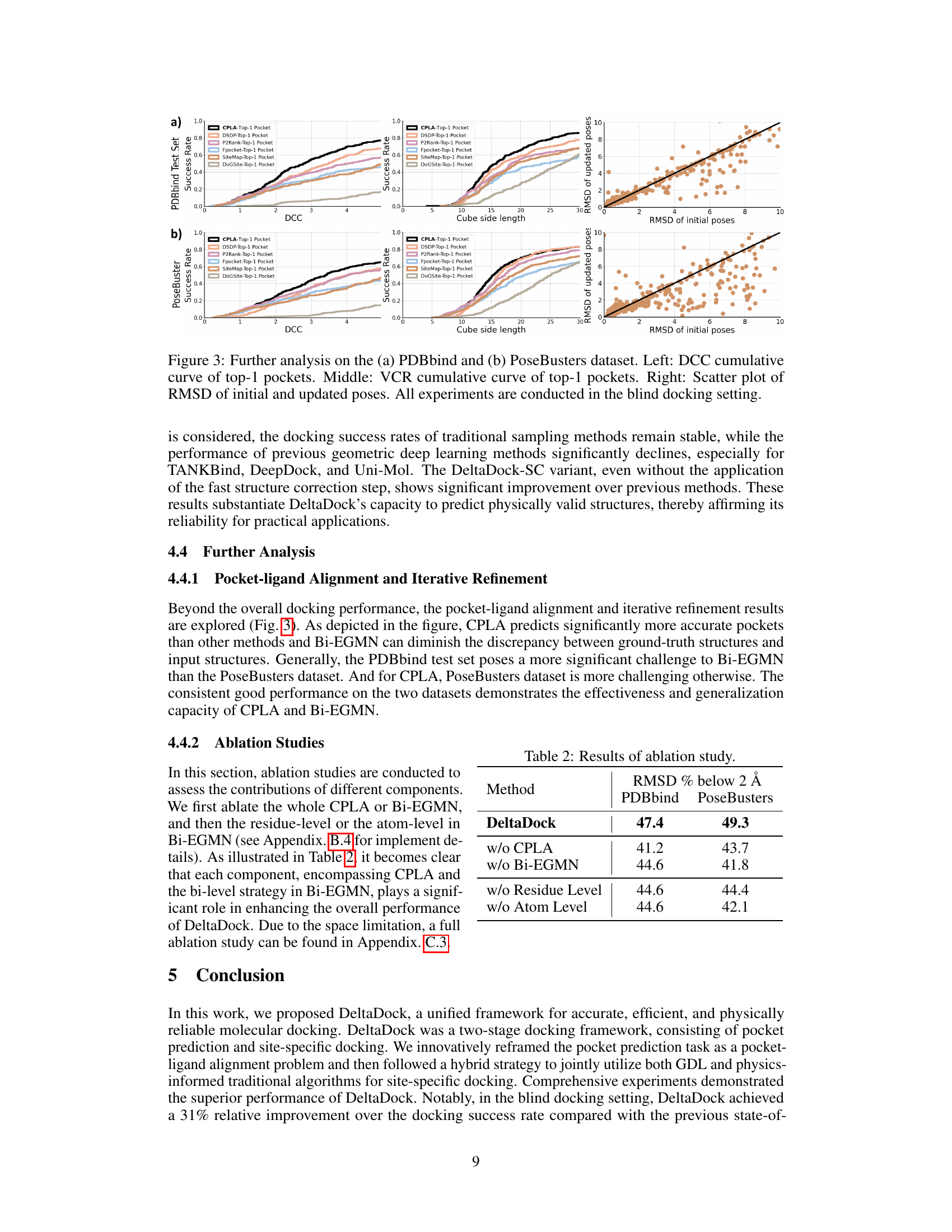

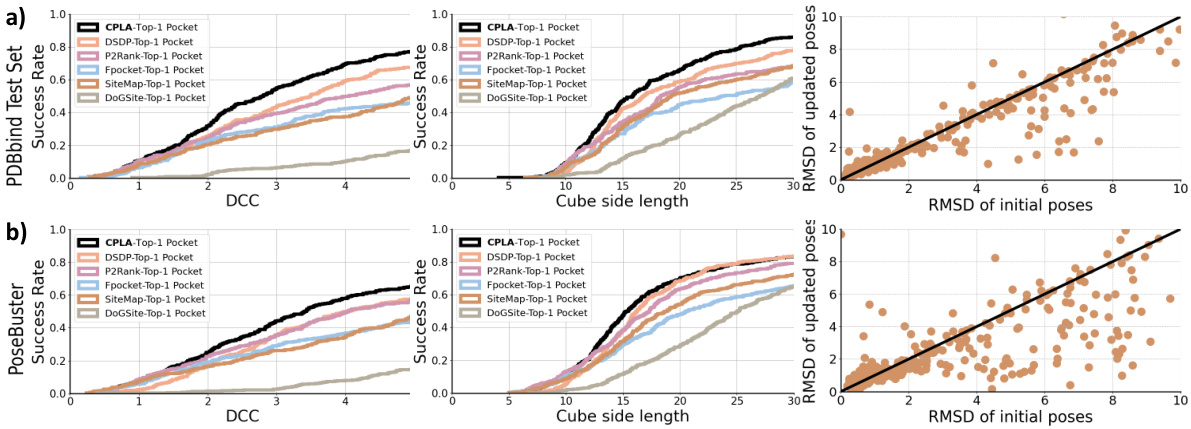

🔼 This figure presents a detailed analysis of DeltaDock’s performance in blind docking settings, using two datasets, PDBbind and PoseBusters. The left panels show cumulative curves illustrating the distribution of the distance between the predicted pocket center and the ligand center (DCC) for the top-predicted pocket by DeltaDock and several other methods. The middle panels show similar cumulative curves for the volume coverage rate (VCR). The right panels show scatter plots correlating the RMSD of initial and refined poses for the various methods, highlighting the iterative refinement process.

read the caption

Figure 3: Further analysis on the (a) PDBbind and (b) PoseBusters dataset. Left: DCC cumulative curve of top-1 pockets. Middle: VCR cumulative curve of top-1 pockets. Right: Scatter plot of RMSD of initial and updated poses. All experiments are conducted in the blind docking setting.

🔼 This figure shows the two main modules of the DeltaDock framework: CPLA (pocket-ligand alignment) and Bi-EGMN (bi-level iterative refinement). CPLA uses contrastive learning to identify the best binding pocket, while Bi-EGMN refines the ligand pose through iterative steps, incorporating physical constraints for accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of DeltaDock's two modules. (a) The pocket-ligand alignment module CPLA. Contrastive learning is adopted to maximize the correspondence between target pocket and ligand embeddings for training. During inference, the pocket with the highest similarity of the ligand is selected. (b) The bi-level iterative refinement module Bi-EGMN. Initialized with a high-quality sampled pose, the module first performs a coarse-to-fine iterative refinement. This process generates progressively refined ligand poses utilizing a recycling strategy. To guarantee the physical plausibility of the predicted poses, a two-step fast structure correction is subsequently applied. This correction involves torsion angle alignment followed by energy minimization based on the SMINA.

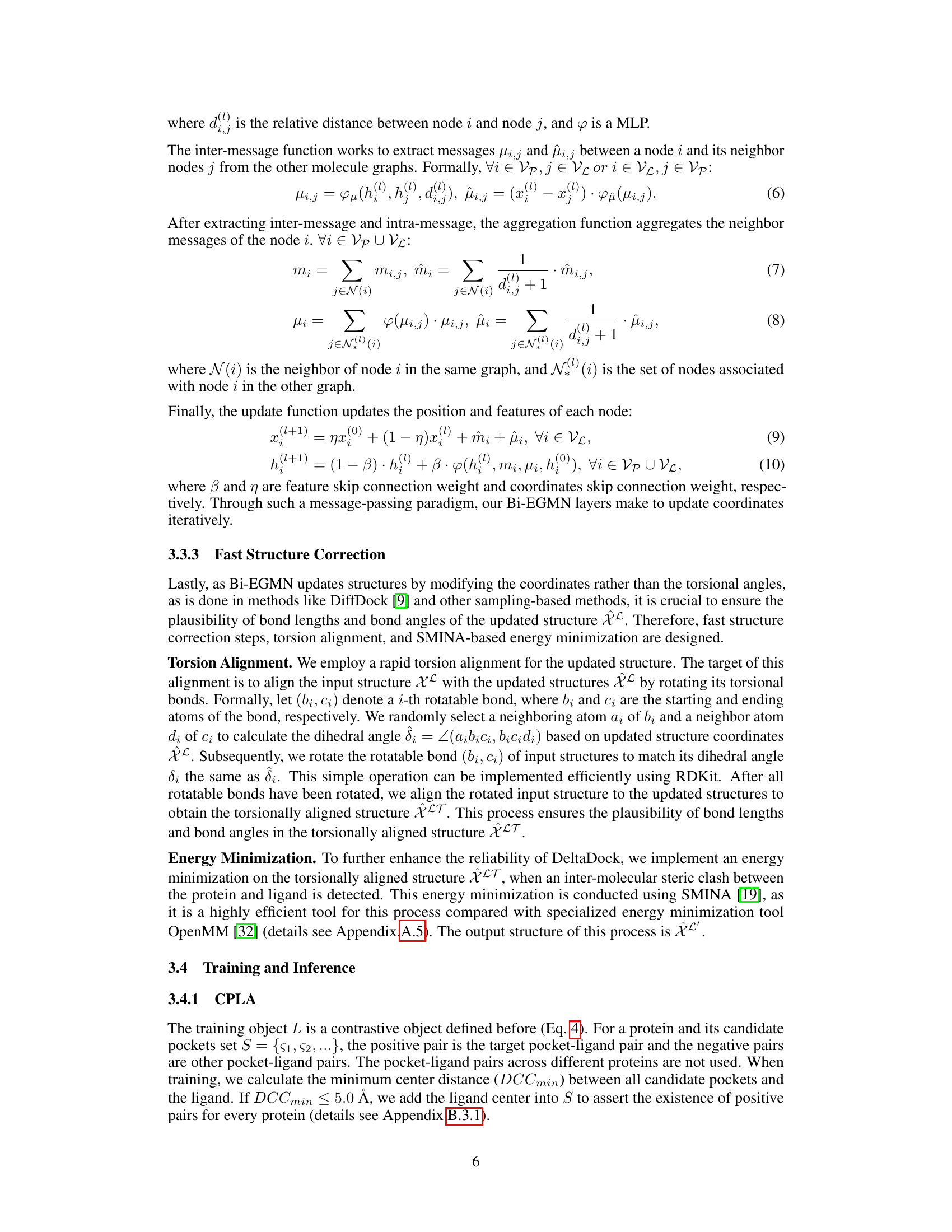

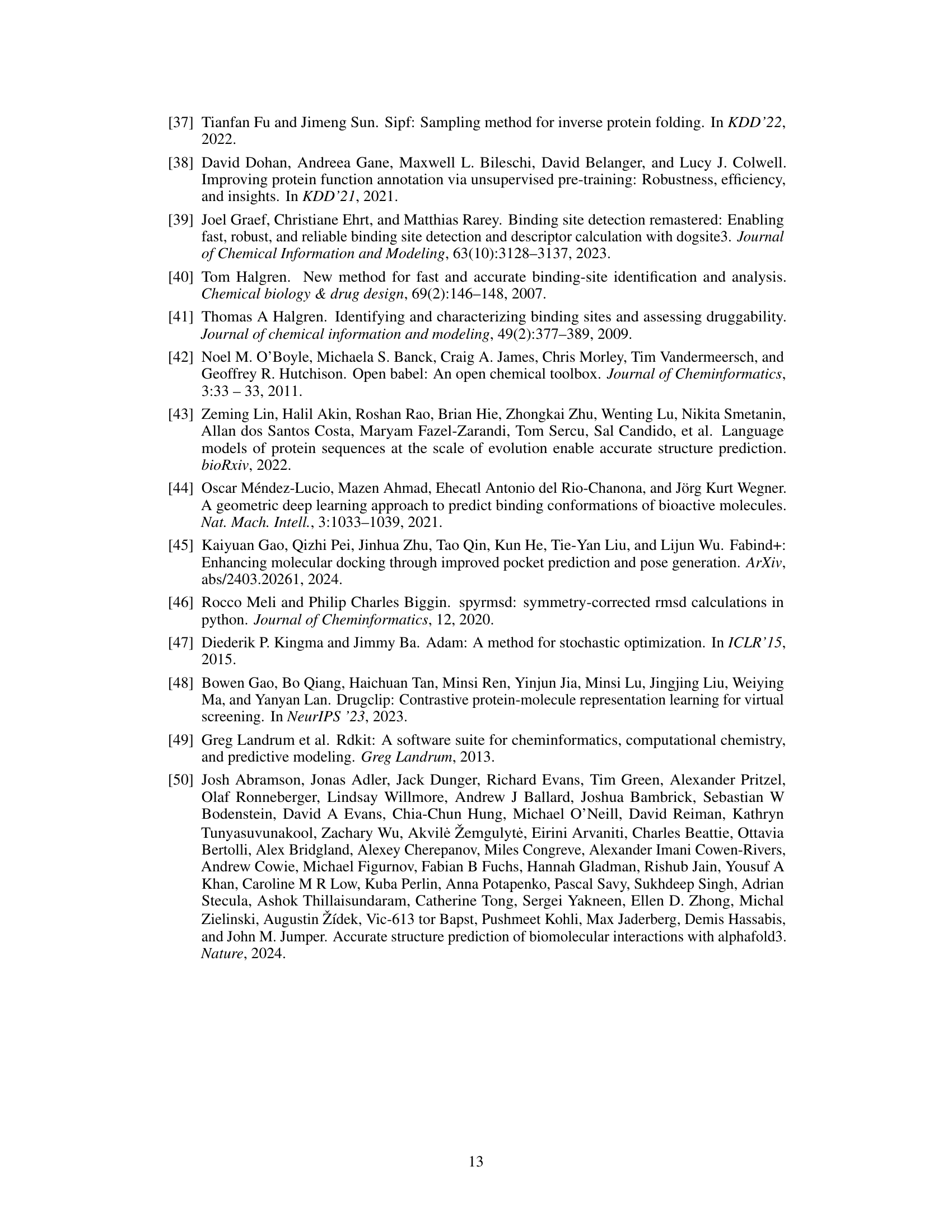

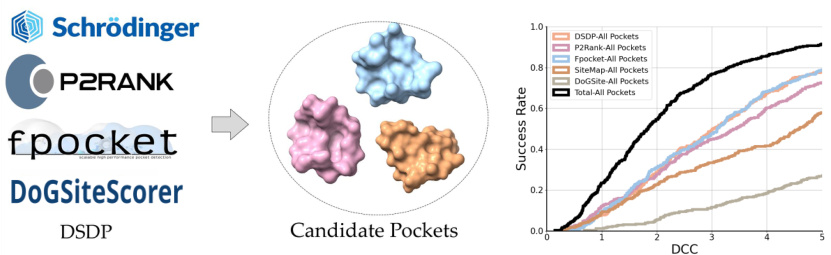

🔼 The figure shows the performance of different pocket prediction methods on the PDBbind test dataset. It illustrates that combining predictions from multiple methods significantly improves the hit rate (the percentage of correctly predicted pockets). The x-axis represents the distance between the predicted pocket center and the ligand center (DCC), while the y-axis shows the success rate. Each colored line represents a different method (DSDP, P2Rank, Fpocket, SiteMap, DoGSiteScorer), and the black line represents the combined predictions from all methods. The plot demonstrates that combining the predictions enhances the accuracy of pocket prediction, highlighting the effectiveness of a combined approach.

read the caption

Figure 5: Performance of different pocket prediction methods on the PDBbind test set. The hit rate is significantly improved by ensembling the predicted pockets from various methods.

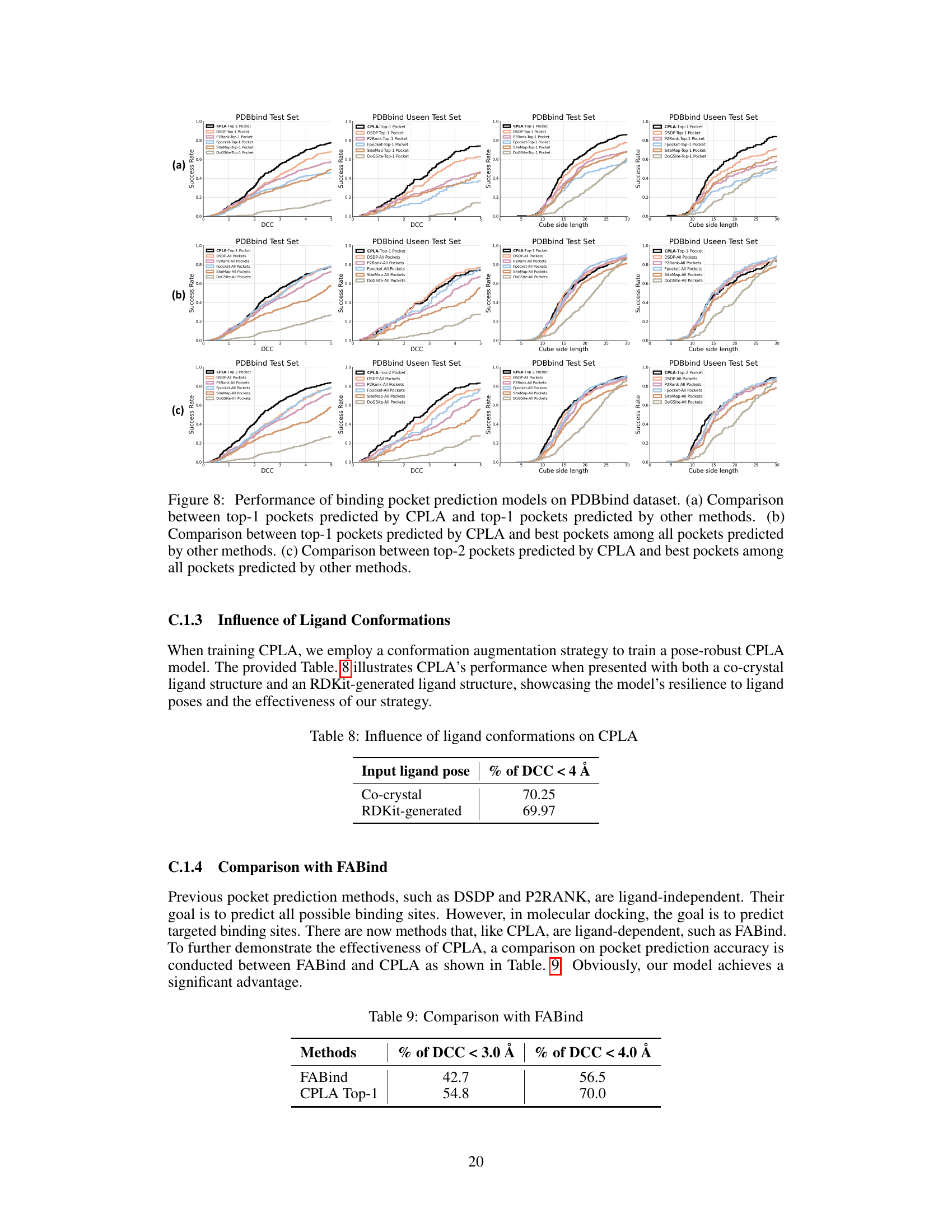

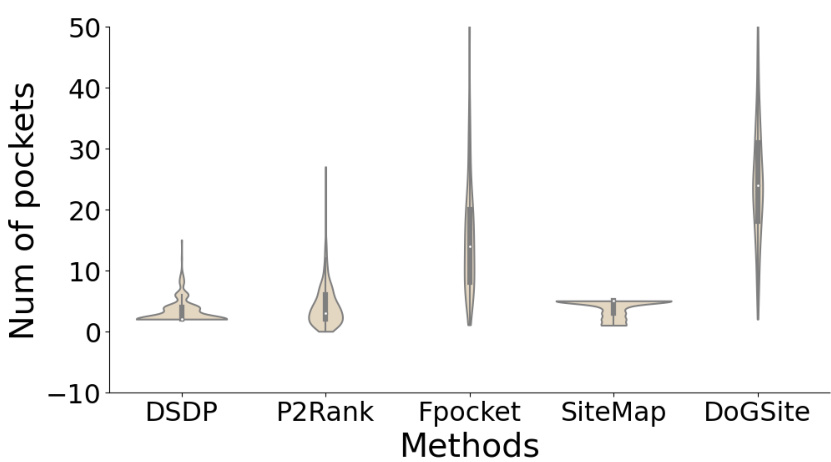

🔼 This figure is a violin plot that shows the distribution of the number of pockets predicted by different pocket prediction methods. The methods compared are DSDP, P2Rank, Fpocket, SiteMap, and DoGSite. The plot reveals significant differences in the number of pockets each method predicts, with Fpocket and DoGSite tending to predict a much larger number of pockets than the other methods. The violin plot also shows the median (represented by a white dot) and the interquartile range (IQR, represented by the thick black bar) for each method. The figure indicates that the number of pockets predicted significantly varies between the methods.

read the caption

Figure 6: Pocket numbers violin plot of different methods. Pocket prediction methods generally predict a series of druggable pockets.

🔼 This figure shows the two main modules of the DeltaDock framework. (a) shows the CPLA (Contrastive Pocket-Ligand Alignment) module which uses contrastive learning to identify the best binding pocket. (b) shows the Bi-EGMN (Bi-level Iterative Refinement) module which refines the initial pose through an iterative process that accounts for physical validity.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of DeltaDock's two modules. (a) The pocket-ligand alignment module CPLA. Contrastive learning is adopted to maximize the correspondence between target pocket and ligand embeddings for training. During inference, the pocket with the highest similarity of the ligand is selected. (b) The bi-level iterative refinement module Bi-EGMN. Initialized with a high-quality sampled pose, the module first performs a coarse-to-fine iterative refinement. This process generates progressively refined ligand poses utilizing a recycling strategy. To guarantee the physical plausibility of the predicted poses, a two-step fast structure correction is subsequently applied. This correction involves torsion angle alignment followed by energy minimization based on the SMINA.

🔼 This figure provides a detailed analysis of the PDBbind and PoseBusters datasets focusing on the performance of the pocket-ligand alignment module (CPLA) and the bi-level iterative refinement module (Bi-EGMN) in DeltaDock. The left panels show the cumulative curves of the Distance between the center of the predicted pocket and ligand center (DCC) for top-1 pockets predicted by different methods. The middle panels illustrate the cumulative curves of the Volume Coverage Rate (VCR) for the top-1 pockets predicted by various methods. Finally, the right panels display scatter plots illustrating the relationship between the RMSD of the initial and updated poses in DeltaDock. This figure demonstrates how DeltaDock successfully refines initial poses through iterative refinement.

read the caption

Figure 3: Further analysis on the (a) PDBbind and (b) PoseBusters dataset. Left: DCC cumulative curve of top-1 pockets. Middle: VCR cumulative curve of top-1 pockets. Right: Scatter plot of RMSD of initial and updated poses. All experiments are conducted in the blind docking setting.

🔼 This figure shows the blind docking performance of DeltaDock and DeltaDock-SC on the PoseBusters dataset. It presents a waterfall plot illustrating the success rate and the number of predictions failing each of the 18 PoseBusters tests. DeltaDock significantly outperforms DeltaDock-SC, demonstrating the improved prediction accuracy and physical validity when employing the fast structure correction and physics-informed training objectives. The plot visually represents the impact of each validity check on the overall docking success rate.

read the caption

Figure 9: Blind Docking Performance on PoseBusters.

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of DeltaDock, which consists of two modules: CPLA (pocket-ligand alignment) and Bi-EGMN (bi-level iterative refinement). CPLA uses contrastive learning to select the best binding pocket. Bi-EGMN refines the ligand pose iteratively, starting from a high-quality initial pose, using a coarse-to-fine approach and ensuring physical validity through structure correction (torsion alignment and energy minimization).

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of DeltaDock's two modules. (a) The pocket-ligand alignment module CPLA. Contrastive learning is adopted to maximize the correspondence between target pocket and ligand embeddings for training. During inference, the pocket with the highest similarity of the ligand is selected. (b) The bi-level iterative refinement module Bi-EGMN. Initialized with a high-quality sampled pose, the module first performs a coarse-to-fine iterative refinement. This process generates progressively refined ligand poses utilizing a recycling strategy. To guarantee the physical plausibility of the predicted poses, a two-step fast structure correction is subsequently applied. This correction involves torsion angle alignment followed by energy minimization based on the SMINA.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main modules of the DeltaDock framework: CPLA (pocket-ligand alignment) and Bi-EGMN (bi-level iterative refinement). CPLA uses contrastive learning to identify the best binding pocket, while Bi-EGMN refines the pose iteratively, incorporating a recycling strategy and fast structure correction to ensure physical validity.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of DeltaDock's two modules. (a) The pocket-ligand alignment module CPLA. Contrastive learning is adopted to maximize the correspondence between target pocket and ligand embeddings for training. During inference, the pocket with the highest similarity of the ligand is selected. (b) The bi-level iterative refinement module Bi-EGMN. Initialized with a high-quality sampled pose, the module first performs a coarse-to-fine iterative refinement. This process generates progressively refined ligand poses utilizing a recycling strategy. To guarantee the physical plausibility of the predicted poses, a two-step fast structure correction is subsequently applied. This correction involves torsion angle alignment followed by energy minimization based on the SMINA.

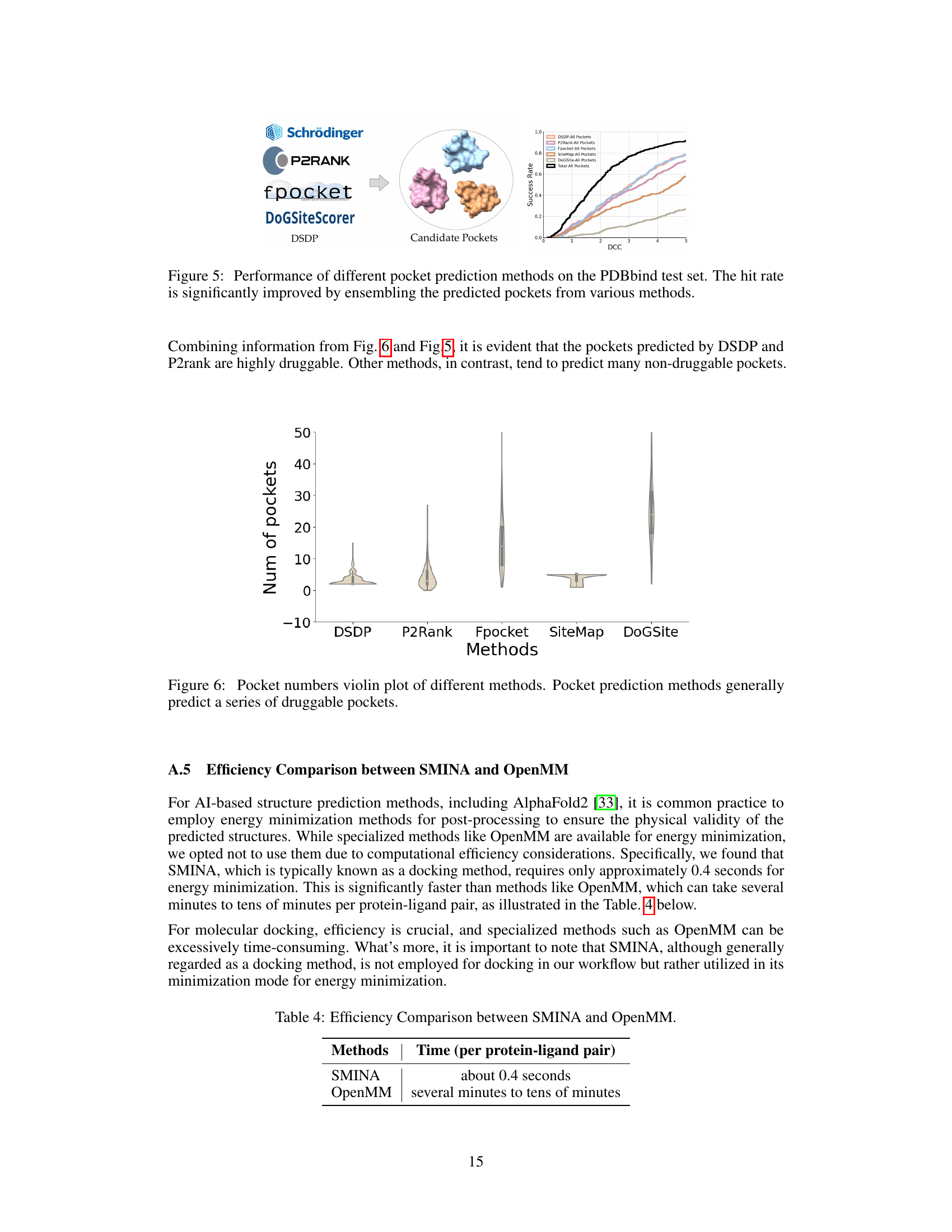

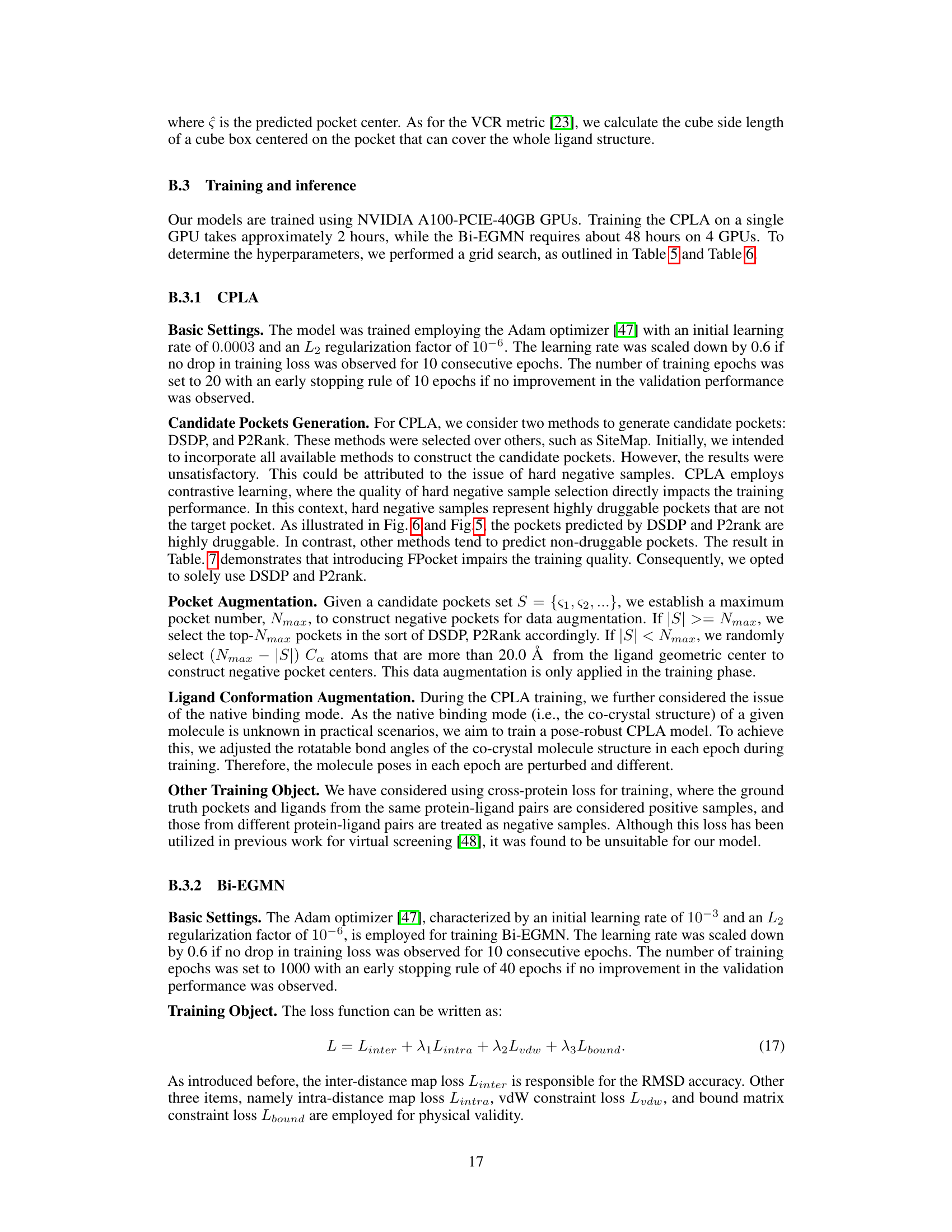

More on tables

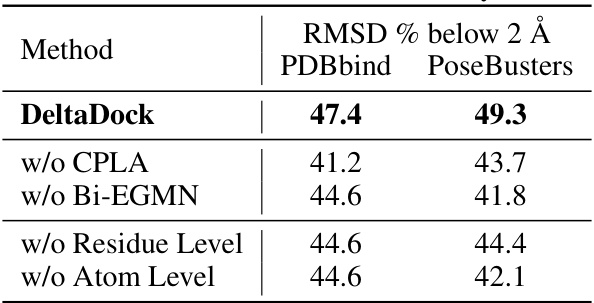

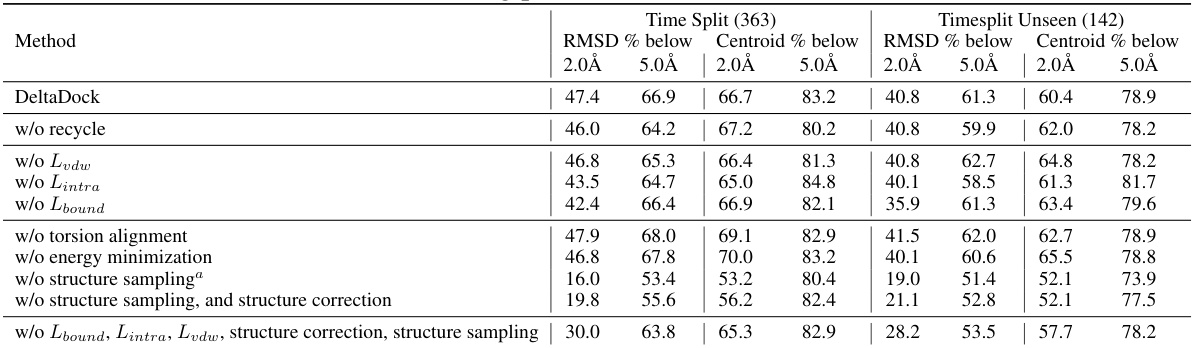

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the contributions of different components of the DeltaDock model. It shows the RMSD % below 2Å on PDBbind and PoseBusters datasets for the full DeltaDock model and several variants where key components (CPLA, Bi-EGMN, residue level, and atom level) have been removed. This allows assessing the individual contribution of each module to the overall performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Results of ablation study.

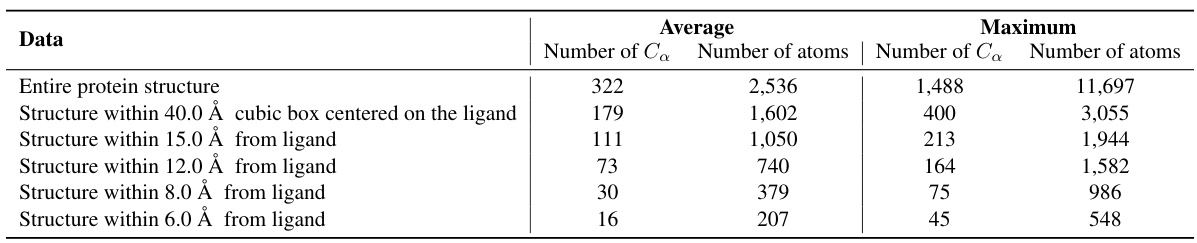

🔼 This table shows the statistics of the PDBbind dataset split based on time. It provides the average and maximum numbers of Cα atoms and total atoms for the entire protein structure and for protein structures within different radii (40.0 Å, 15.0 Å, 12.0 Å, 8.0 Å, and 6.0 Å) centered on the ligand. This data illustrates the size and complexity of the protein structures analyzed in the study, showing how the number of atoms increases as the radius around the ligand expands.

read the caption

Table 3: Statistics of the PDBbind time split test set.

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments on the PDBbind dataset, comparing DeltaDock with several other methods. It shows the performance of each method in terms of time taken, RMSD, and the percentage of poses below specific RMSD thresholds. The table also includes results for DeltaDock variants that omit certain processing steps (fast structure correction and high-quality initial poses) for comparative analysis. The best and second-best results are highlighted for clarity.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments on the PDBbind dataset, comparing DeltaDock with various state-of-the-art methods. The metrics used are RMSD and centroid distance, showing the percentage of successful docking poses within 2Å and 5Å thresholds. The table also provides information on computation time, distinguishing between CPU and GPU usage. Different variants of DeltaDock are included to evaluate the impact of specific modules (fast structure correction, high-quality initial poses).

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments conducted on the PDBbind dataset. It compares the performance of DeltaDock with several other state-of-the-art methods in terms of metrics like RMSD and centroid distance, considering different thresholds (2Å and 5Å) for success rate calculation. The table also includes information about the time taken for each method, which allows for a comparison of computational efficiency. Variations of the DeltaDock model (DeltaDock-SC and DeltaDock-Random) are included to show the individual effects of the fast structure correction and the high-quality initial pose generation steps on the overall docking performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

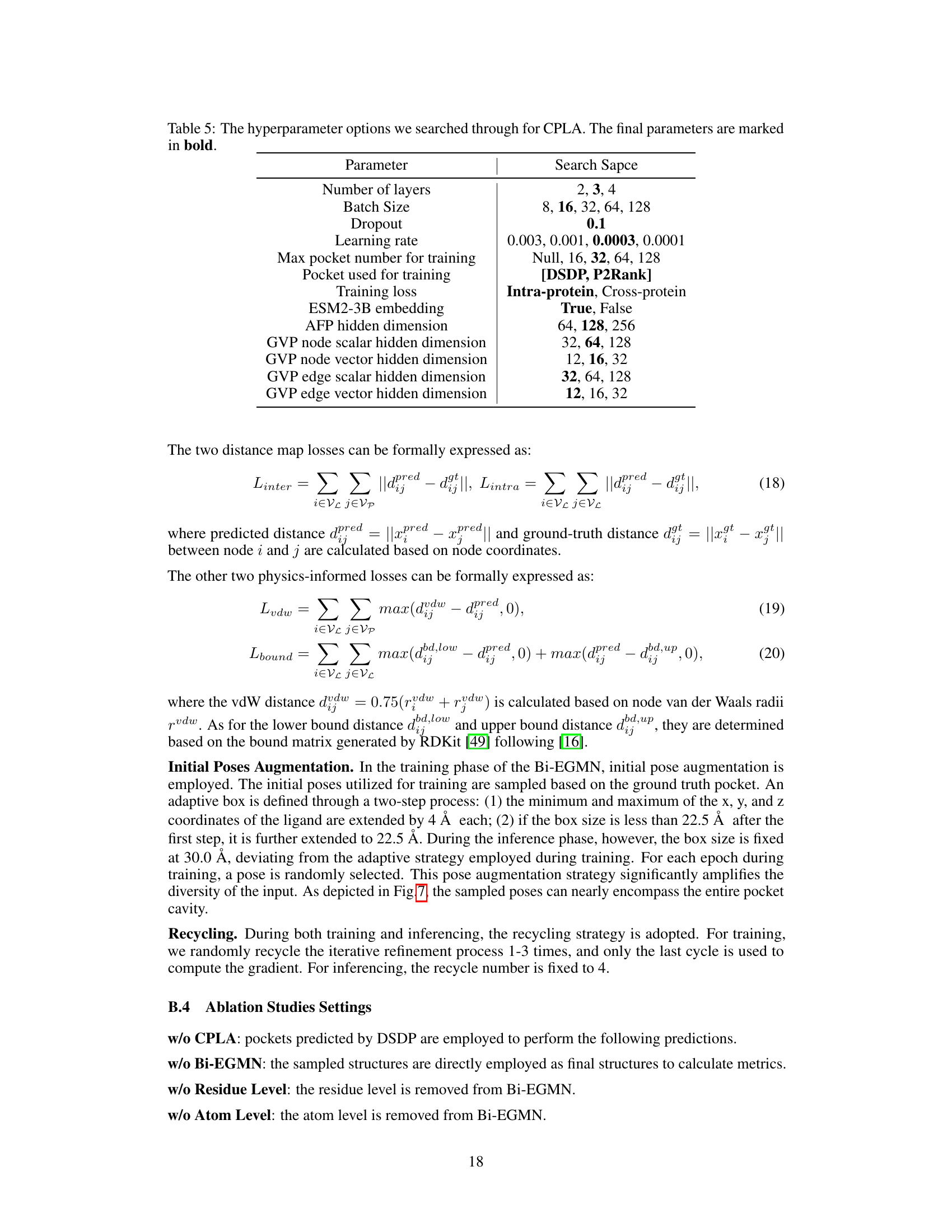

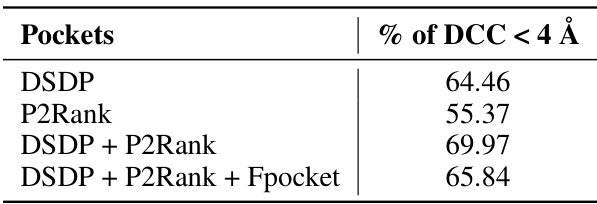

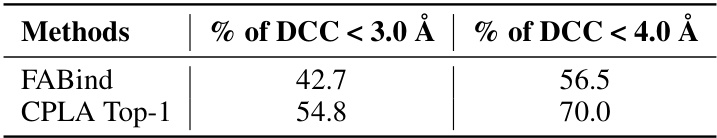

🔼 This table presents the performance of the Contrastive Pocket-Ligand Alignment (CPLA) module when trained using different combinations of candidate pocket prediction methods. It shows the percentage of times the distance between the predicted pocket center and the ligand center (DCC) is less than 4 angstroms. The results demonstrate that combining DSDP and P2Rank pockets yields the best performance, while including Fpocket does not improve the results.

read the caption

Table 7: Performance of employing different candidate pockets to train CPLA

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments on the PDBbind dataset, comparing DeltaDock’s performance against several other methods. It shows the docking success rate (% below 2.0Å RMSD and % below 5.0Å RMSD), average docking time (seconds), and centroid distance for various methods. Variants of DeltaDock (DeltaDock-SC and DeltaDock-Random) are included to show the impact of certain components on performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different molecular docking methods on the PDBbind dataset for blind docking. The table shows the performance of various methods, including DeltaDock and several baselines. Performance is measured by RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) and Centroid Distance, at thresholds of 2Å and 5Å, indicating the accuracy of predicted ligand binding poses. The table also includes the average time taken per docking task for each method and highlights the superior performance of DeltaDock, especially when considering the physical validity of the poses.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various molecular docking methods on the PDBbind dataset for blind docking. It shows the performance of different methods in terms of time, RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation), and the percentage of results below RMSD thresholds of 2.0Å and 5.0Å, both for the entire dataset and a subset of unseen structures. The table highlights the superior performance of DeltaDock and its variants (DeltaDock-SC and DeltaDock-Random) compared to existing methods, especially in terms of accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various molecular docking methods on the PDBbind dataset for blind docking. The performance metrics include RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) and centroid distance, both at 2Å and 5Å thresholds. The table also shows the time taken by each method and distinguishes between models with and without fast structure correction or high-quality initial poses. The results highlight DeltaDock’s superior performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents the results of blind docking experiments on the PDBbind dataset, comparing DeltaDock’s performance against various traditional and geometric deep learning-based methods. The metrics used are RMSD and Centroid distance at different thresholds (2Å and 5Å). The table also shows the time taken by each method and considers two variants of DeltaDock (DeltaDock-SC and DeltaDock-Random) to highlight the contribution of different components.

read the caption

Table 1: Blind docking performance on the PDBbind dataset. All methods take RDKit-generated ligand structures and holo protein structures as input, trying to predict bound complex structures. DeltaDock-SC refers to the model variant that generates structures without implementing fast structure correction. DeltaDock-Random refers to the model variant that generates structures without high-quality initial poses. The best results are bold, and the second best results are underlined.

Full paper#