↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) based on Transformers exhibit surprising in-context learning (ICL) abilities. However, the underlying mechanisms of ICL remain unclear, hindering the development of more effective and interpretable LLMs. Existing research offers various perspectives, but a comprehensive understanding is still lacking. In particular, it is unclear how ICL relates to fundamental machine learning principles like gradient descent and representation learning, especially in the complex settings of Transformer models.

This research investigates the ICL process of Transformer models through the lens of representation learning. The authors connect the ICL inference process to the training process of a dual model via kernel methods. This allows them to analyze ICL as a form of gradient descent, deriving a generalization error bound. Furthermore, inspired by contrastive learning, they propose several modifications for the attention layers to improve ICL capabilities. Experimental results on synthetic tasks support their findings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap in understanding in-context learning (ICL) in Transformers, a significant area in AI research. By connecting ICL to representation learning and gradient descent, the study offers valuable insights that could advance the development of more efficient and robust LLMs. The provided generalization error bound and suggested modifications pave the way for more effective ICL algorithms and improved model designs, impacting various downstream AI applications.

Visual Insights#

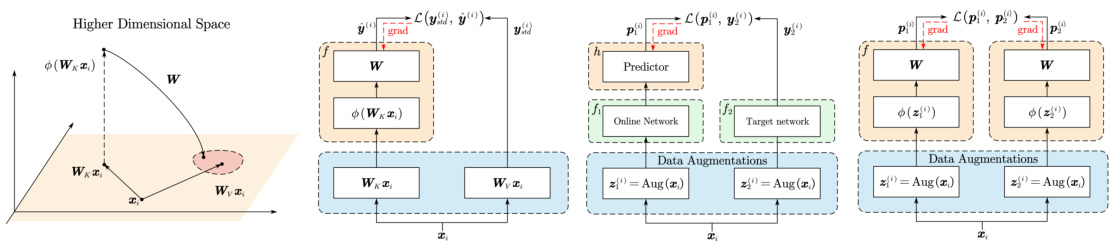

This figure illustrates the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a single softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process of its dual model. The ICL process generates a prediction (h’N+1) for a query token based on example input tokens. This prediction is shown to be equivalent to the test prediction (ŷtest) of a dual model trained on data derived from the example and query tokens. The figure highlights how the training data for the dual model is created by linear transformations of the input tokens and how backpropagation signals contribute to the final prediction, showing the relationship between ICL and representation learning.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on a subset of the GLUE benchmark using different modifications to the attention mechanism. The table shows the performance of the original model and models with various modifications (regularized, augmented, negative samples) across four different tasks: CoLA, MRPC, STS-B, and RTE. The ‘Local Best’ row highlights the best performance achieved for each modification type, while ‘Global Best’ indicates the overall best performing model across all modifications. Different metrics are used for each task reflecting the nature of the task (e.g., Matthews correlation for CoLA, F1 score/accuracy for MRPC, Pearson/Spearman correlation for STS-B, accuracy for RTE).

In-depth insights#

ICL via Dual Model#

The concept of “ICL via Dual Model” presents a novel perspective on in-context learning (ICL) within transformer models. It suggests that the ICL inference process, seemingly a complex interaction of attention weights and token embeddings, can be viewed as a form of gradient descent in a dual model space. This dual model is not explicitly part of the original transformer architecture but rather a mathematical construct derived from kernel methods applied to the softmax attention layer. By establishing an equivalence between the ICL process and gradient descent in this dual model, the authors offer a simplified, yet powerful interpretation of ICL. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of ICL’s representation learning aspects and provides a framework to potentially modify transformer layers to improve ICL performance. Importantly, this reframing moves beyond previous work that primarily focused on linear attention mechanisms by directly addressing the widely used softmax attention. The dual model’s training procedure is analyzed through the lens of representation learning, making the connection between ICL and existing representation learning techniques explicit. This provides a pathway for incorporating advancements in representation learning to enhance ICL, potentially leading to improved model generalization and performance. A key advantage is the derivation of generalization error bounds linked to the number of demonstration tokens, lending theoretical support to the observed empirical effectiveness of ICL.

Softmax Kernel ICL#

The concept of “Softmax Kernel ICL” blends the softmax function, known for its role in attention mechanisms within Transformer networks, with the idea of in-context learning (ICL). The core idea is to leverage the softmax function’s ability to generate weighted probabilities, representing the importance of different input tokens during ICL, as a kernel function. This approach potentially allows for a more nuanced understanding of how Transformers implicitly learn from a few examples. By viewing ICL through a kernel perspective, researchers could gain insights into the generalization capabilities of ICL. Specifically, analyzing the kernel properties, such as its smoothness and expressiveness, could reveal limitations or potential improvements of the attention mechanism. It may also allow for the creation of theoretical bounds on ICL’s performance. This kernel-based approach offers a unique representation learning perspective on ICL, shifting from a gradient-descent perspective to exploring implicit kernel methods. This shift could lead to a better understanding of how knowledge is transferred during ICL, potentially paving the way for more efficient and robust ICL algorithms. Further research would focus on theoretical underpinnings, including examining various kernel choices and the implications for generalization error.

Generalization Bounds#

The concept of generalization bounds in machine learning, particularly within the context of in-context learning (ICL), is crucial for understanding a model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Generalization bounds provide theoretical guarantees on the expected performance of a model on new, unseen data based on its performance on training data. In the paper, the authors likely derive such bounds for the dual model they propose to explain in-context learning. This would involve analyzing the complexity of the hypothesis space (the set of possible functions the model can learn) and potentially using techniques like Rademacher complexity or VC dimension. A tighter bound suggests stronger generalization ability, implying that the model is less likely to overfit the training data. The authors likely relate the generalization bound to the number of demonstration examples used in ICL, suggesting that more demonstrations improve generalization by providing more information about the task. However, it is essential to note that these bounds are often pessimistic and may not accurately reflect real-world performance. Nevertheless, they provide valuable theoretical insights into the ICL process and are important for understanding the model’s capabilities.

Attention Modif.#

The section on “Attention Modif.” explores enhancements to the standard Transformer attention mechanism, aiming to improve in-context learning (ICL). The authors draw inspiration from contrastive learning, a self-supervised representation learning technique. Three key modifications are proposed: Regularization, Data Augmentation, and Negative Samples. Regularization focuses on controlling the norm of the weight matrix in the attention layer to prevent overfitting and enhance generalization. Data Augmentation aims to enrich the representation learning process by introducing more sophisticated transformations than simple linear mappings, potentially utilizing neural networks for non-linear augmentation. Lastly, introducing Negative Samples is considered to help prevent representational collapse and improve the discrimination of representations learned by the attention mechanism. These modifications show potential for improving ICL in various experiments, highlighting the value of viewing attention through the lens of representation learning and leveraging self-supervised learning strategies.

Future ICL Research#

Future research in In-Context Learning (ICL) should prioritize a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving ICL’s capabilities. Moving beyond correlational studies, investigations should focus on causal relationships between input examples, model architecture, and emergent behaviors. This necessitates exploring the role of attention mechanisms in ICL, particularly how different attention types (e.g., linear vs. softmax) affect performance and generalization. Furthermore, research should address the limitations of current ICL approaches, including their susceptibility to adversarial examples, and explore methods to improve robustness and reliability. A key area for future investigation is the development of more principled theoretical frameworks for ICL, which can provide generalization bounds and explain the behavior of ICL across various tasks and datasets. Finally, it is crucial to explore the impact of different model architectures and training procedures on ICL’s efficacy and investigate how ICL can be further enhanced through techniques like transfer learning and meta-learning. The development of benchmark datasets specifically designed to evaluate the performance of ICL across diverse tasks is essential for fostering the advancement of the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

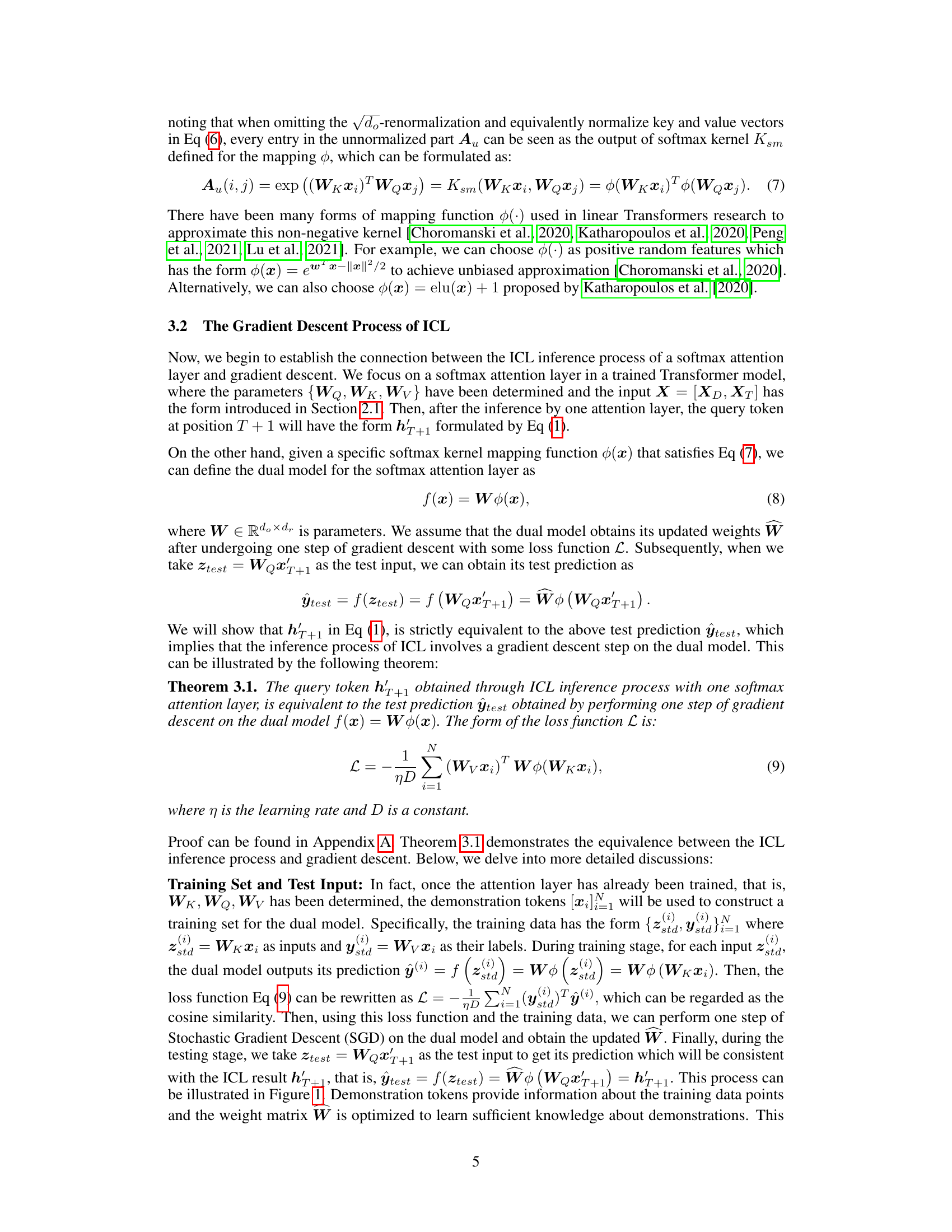

The figure compares three representation learning processes. The left part shows how the ICL process in a softmax attention layer can be interpreted as a representation learning problem, where the key and value mappings generate positive sample pairs. The center-left part shows this ICL process aligns with contrastive learning without negative samples. The center-right part shows the ICL process aligns with contrastive kernel learning.

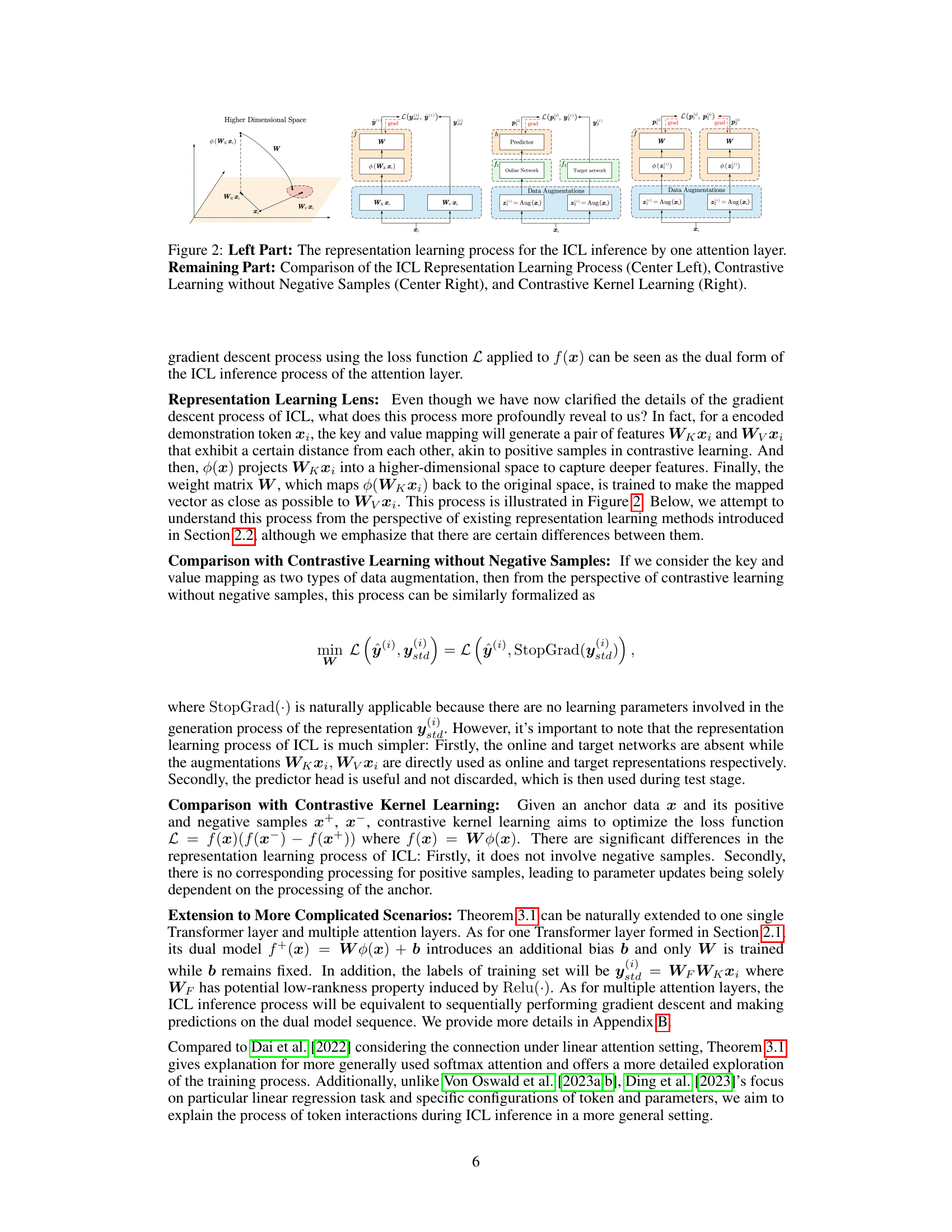

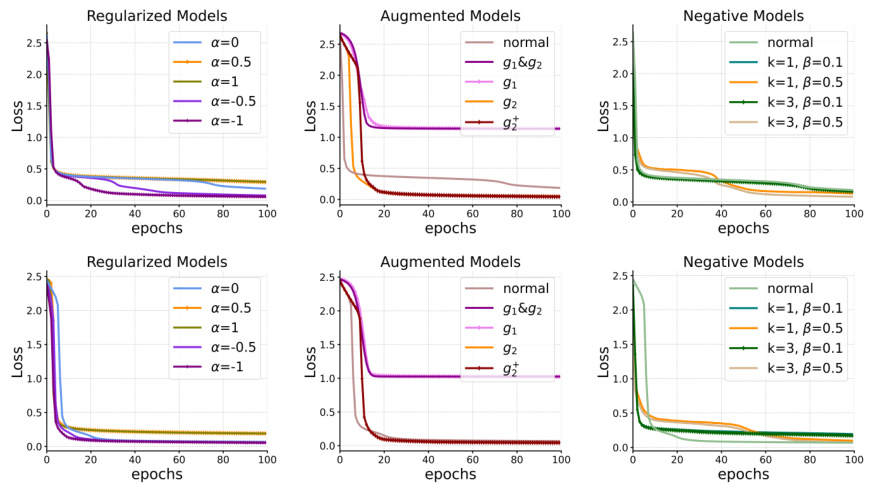

This figure demonstrates the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a single softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process on its dual model. The left panel shows the convergence of the ICL prediction (h’N+1) to the dual model’s prediction (ŷtest). The right panel compares the performance of three model modifications: regularized models (adjusting the attention weight norm), augmented models (modifying data input using nonlinear mappings), and negative models (introducing negative samples). The results across different settings are presented.

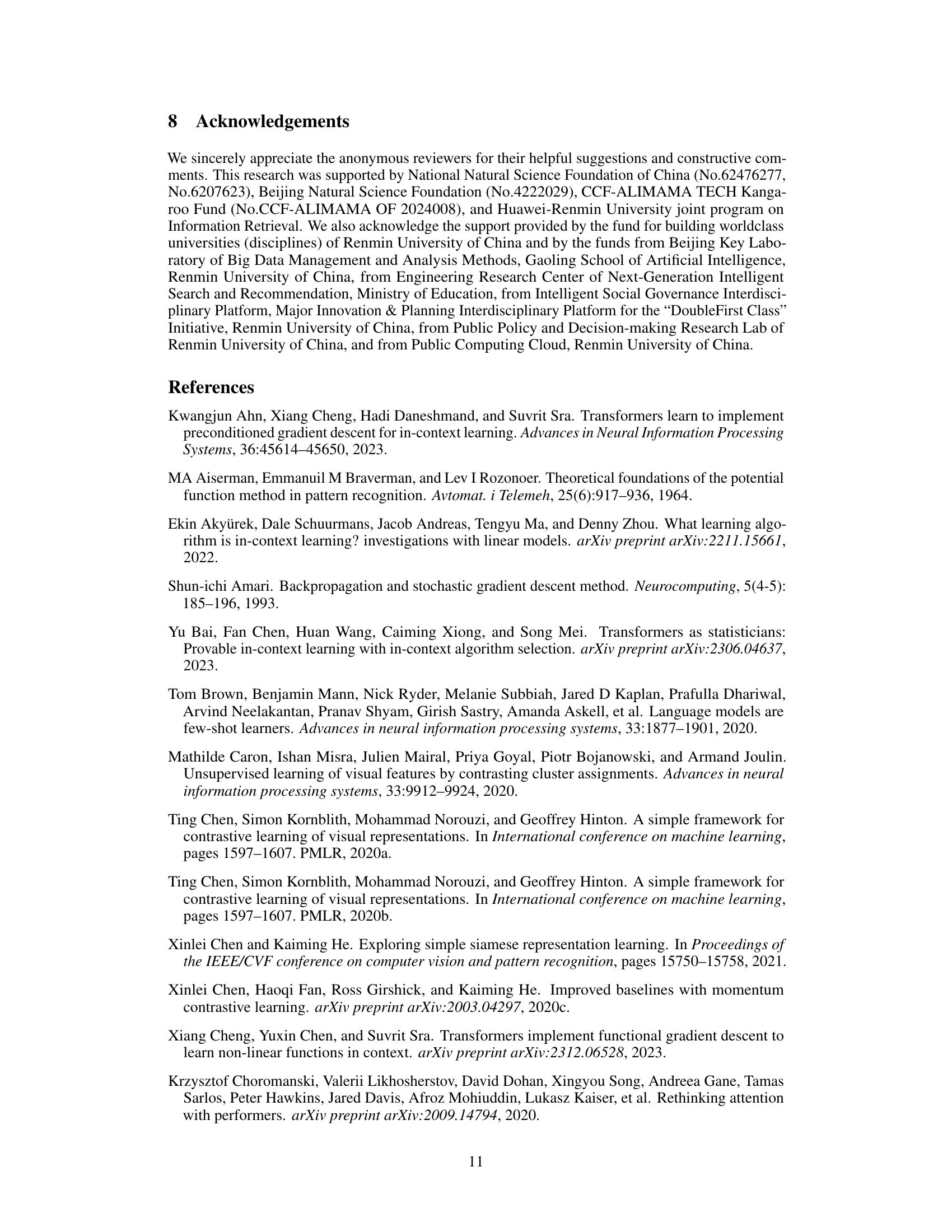

This figure illustrates the representation learning process of In-context Learning (ICL) inference through a single Transformer layer from the perspective of representation learning. The left panel depicts the process showing the key and value mappings by matrices WK and Wv, respectively. The intermediate representation obtained after softmax attention is passed through a feed-forward network (FFN), represented by matrices W1 and W2. The resulting output, h’T+1, is equivalent to the result of a gradient descent step on a dual model. The right panel shows this process in a higher-dimensional space where the key and value vectors are projected into a higher dimensional space through function ϕ. The weight matrix W is then trained to minimize the distance between the two projected vectors, approximating the ICL inference process.

This figure illustrates the in-context learning (ICL) inference process through multiple softmax attention layers, showing how it aligns with the gradient descent on a sequence of dual models. Each layer’s ICL inference is analogous to one gradient descent step on its corresponding dual model. The dual models use training data derived from the previous layer’s output, making the overall process a sequential gradient descent.

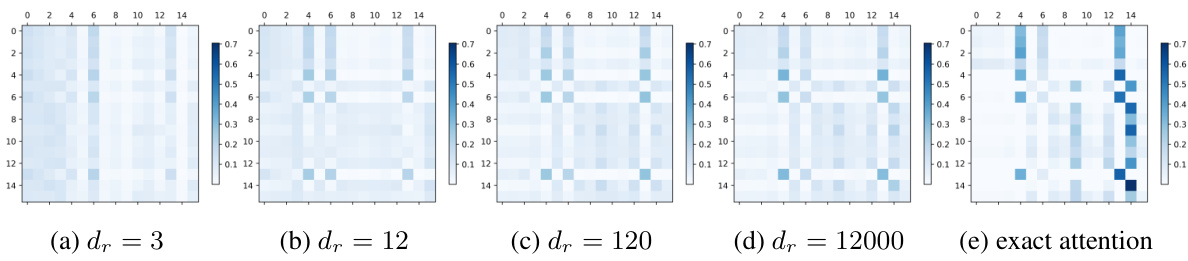

This figure visualizes how well positive random features can approximate the attention matrix in a Transformer model. It shows heatmaps of the attention matrix for different values of dr (the dimension of the random features). The (e) subfigure presents the exact attention matrix, providing a ground truth for comparison. The other subfigures show how closely the approximated matrices match the exact attention matrix as the dimension dr increases. This helps to illustrate the quality of approximation.

This figure demonstrates the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a single softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process on its dual model. The left part shows how the L2 norm of the difference between the ICL output (h’N+1) and the dual model’s test prediction (ŷtest) decreases as the gradient descent on the dual model progresses (over 15 steps). The right part compares the performance of three types of modified models (regularized, augmented, and negative) with different parameter settings, illustrating their impact on the ICL process.

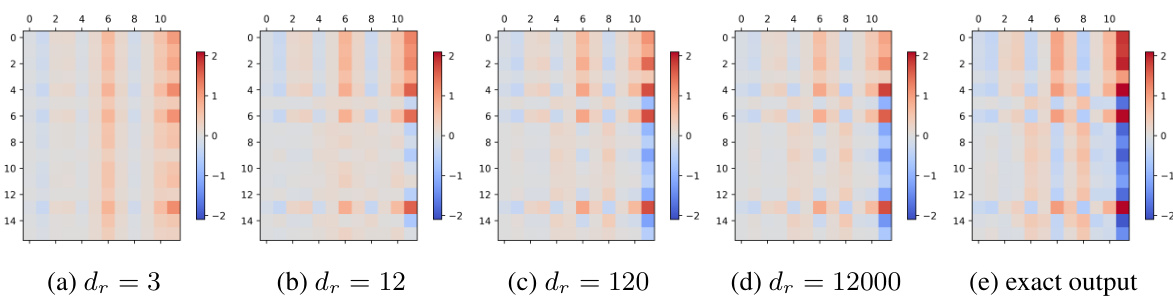

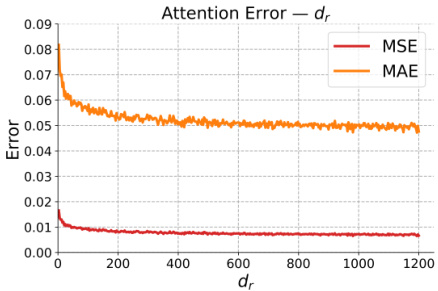

This figure shows two sub-figures. The left sub-figure shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in estimating the attention matrix when varying the dimension of random features (dr). The right sub-figure shows the MSE and MAE in estimating the output matrix when varying dr. Both sub-figures show that as the dimension of random features increases, the approximation performance gradually improves, with both errors reaching a low level in the end.

This figure shows two line graphs plotting the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) against different values of the dimension of random features (dr). The errors represent how well the positive random features approximate the attention matrix and the output matrix within the Transformer model’s attention mechanism. The results demonstrate that as dr increases, the approximation accuracy improves, with both MSE and MAE decreasing. This finding is important because it shows that the positive random features method, used to simplify the analysis, is effective in approximating the more complex softmax attention.

This figure shows the experimental results supporting the paper’s claim that the in-context learning (ICL) process in a single softmax attention layer is equivalent to a gradient descent process on its dual model. The left part shows the convergence of the test prediction of the dual model (ŷtest) to the ICL output (h’T+1) across gradient descent steps. The right part compares the performance of different model modifications (regularized, augmented, and negative models) demonstrating how these modifications affect the ICL process and their effectiveness.

This figure shows the results of experiments designed to demonstrate the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process of its dual model. The left panel shows the squared difference between the ICL output and the dual model’s prediction (||ŷtest - h’T+1||2) as the gradient descent progresses. The right panel displays the performance of three different model modifications (regularized, augmented, negative) under various hyperparameter settings. Each modification aims to improve the attention mechanism by drawing inspiration from representation learning techniques. This comparison provides evidence supporting the proposed dual model theory and the effectiveness of the modifications.

This figure demonstrates the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process of its dual model. The left part shows the convergence of the L2 norm of the difference between the ICL output and the dual model prediction as the gradient descent progresses. The right part compares the performance of three modified models (regularized, augmented, and negative) with different settings, illustrating the effects of these modifications on the ICL process.

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to demonstrate the equivalence between in-context learning (ICL) in a single softmax attention layer and a gradient descent process on its dual model. The left panel shows how the difference between the ICL output and the prediction from the trained dual model decreases as the number of gradient descent steps increases. The other three panels show how different modifications to the attention mechanism (regularized, augmented, and negative models) impact its performance. Each panel shows curves for various hyperparameter settings for the modifications. This demonstrates that the ICL process can be understood and potentially improved using the lens of representation learning and gradient descent.

This figure shows the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process of its dual model. The left part shows how the difference between the ICL output (h’N+1) and the dual model’s test prediction (ŷtest) decreases as the gradient descent progresses. The right part compares the performance of three model modifications (regularized, augmented, and negative models) under different settings, illustrating the impact of these modifications on the ICL process.

This figure shows the equivalence between the in-context learning (ICL) process of a single softmax attention layer and the gradient descent process of its dual model. The left part of the figure shows how the difference between the ICL output (h’N+1) and the test prediction of the dual model (ŷtest) decreases as the number of gradient descent steps increases. The right part compares the performance of three different model modifications: regularized models, augmented models, and negative models, under different settings. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed modifications.

Full paper#