↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning and statistics problems involve optimizing non-convex functions, particularly continuous adversarial weakly-up-concave functions which include DR-submodular and concave functions. These problems are challenging due to the complexity of non-convex optimization and the various feedback settings involved (full information, semi-bandit, bandit). Existing solutions often make strong assumptions and offer limited regret guarantees.

This paper addresses these issues by introducing the concept of upper-linearizable functions. These functions generalize concavity and DR-submodularity. The authors devise a meta-algorithm that converts algorithms designed for linear/quadratic maximization to optimize upper-linearizable functions. This novel framework is then extended to handle various feedback settings. Using this framework, the authors derive new algorithms and prove improved state-of-the-art regret bounds (static, dynamic, adaptive) for DR-submodular maximization, requiring fewer assumptions compared to existing methods. The approach is versatile and applicable to various optimization problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in non-convex optimization, particularly those working with DR-submodular and concave functions. It significantly advances the field by offering a unified framework applicable to various feedback settings (bandit, semi-bandit, full-information), function characteristics (monotone, non-monotone), and constraint types. The introduction of upper-linearizable functions opens up new avenues for algorithm development and analysis, and the improved regret bounds and dynamic/adaptive regret guarantees are directly relevant to current research trends.

Visual Insights#

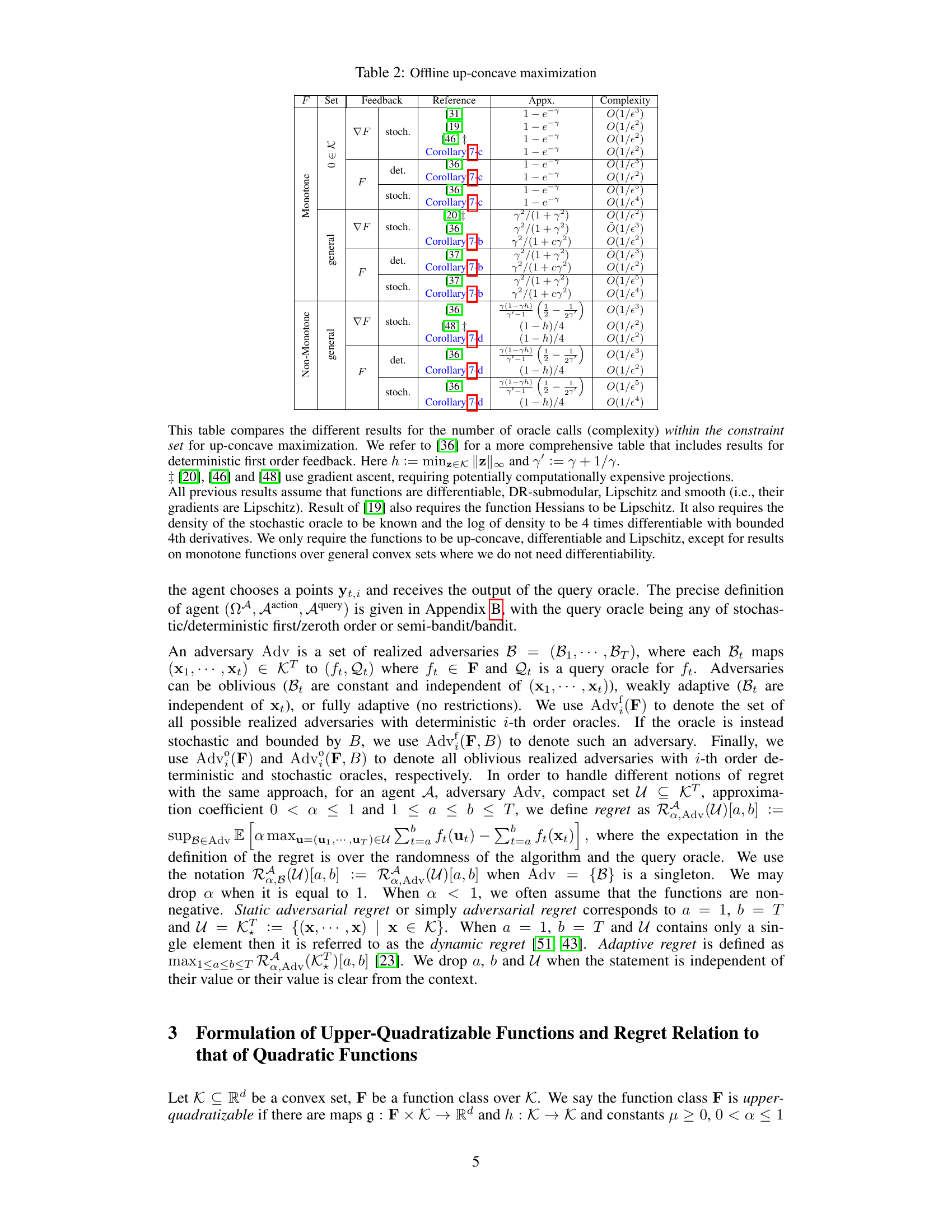

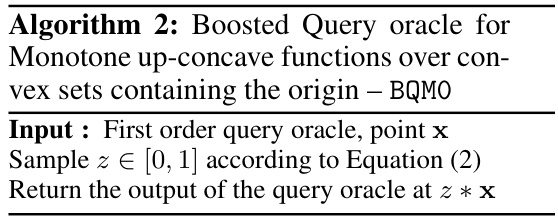

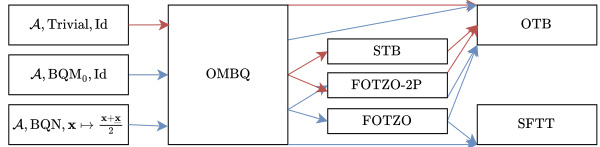

This figure summarizes various applications of the proposed framework. It shows how to obtain different regret guarantees (static, dynamic, adaptive) and feedback types (full information, semi-bandit, bandit, first-order, zeroth-order) for DR-submodular optimization by combining different base algorithms (SO-OGD, Improved Ader) and meta-algorithms (OMBQ, FOTZO, STB, SFTT, OTB).

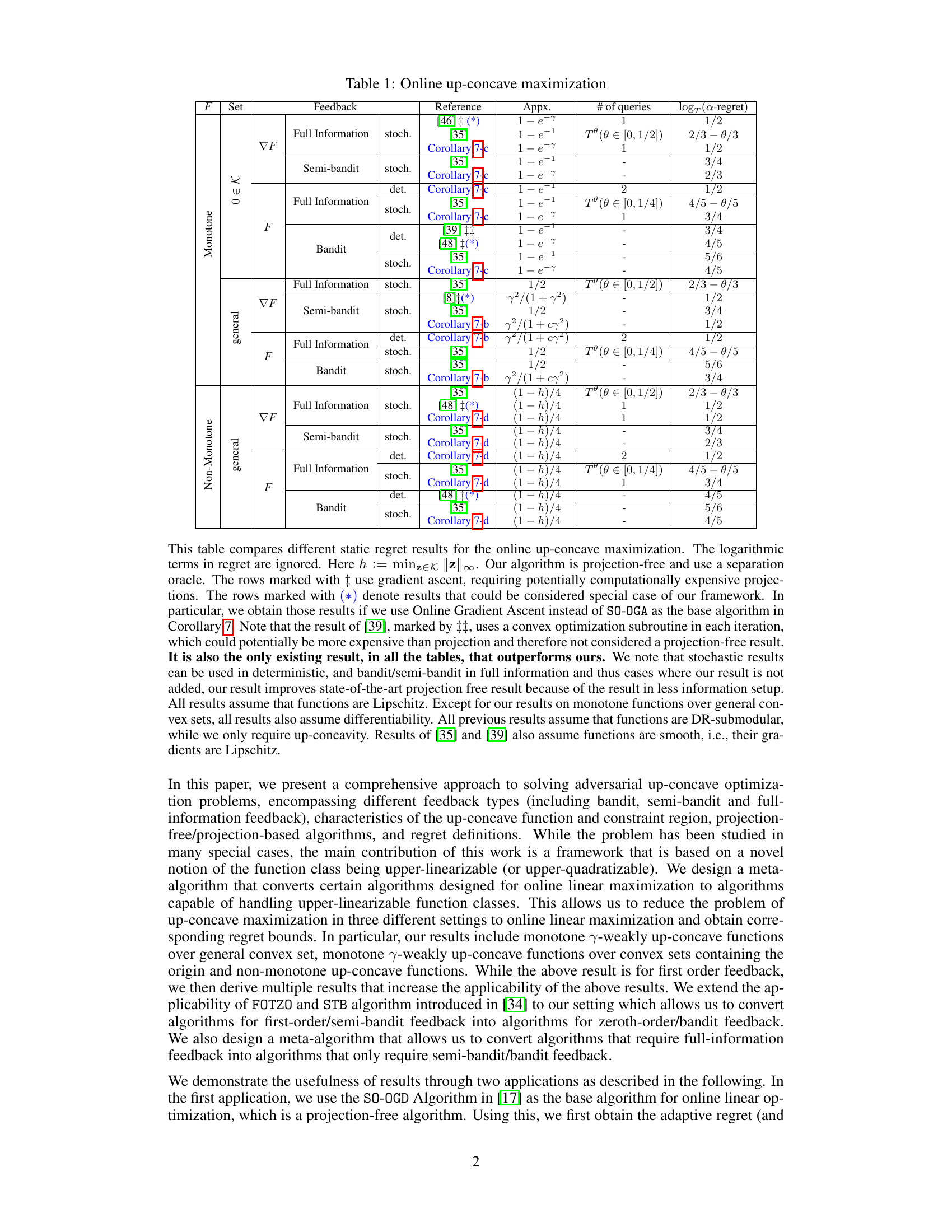

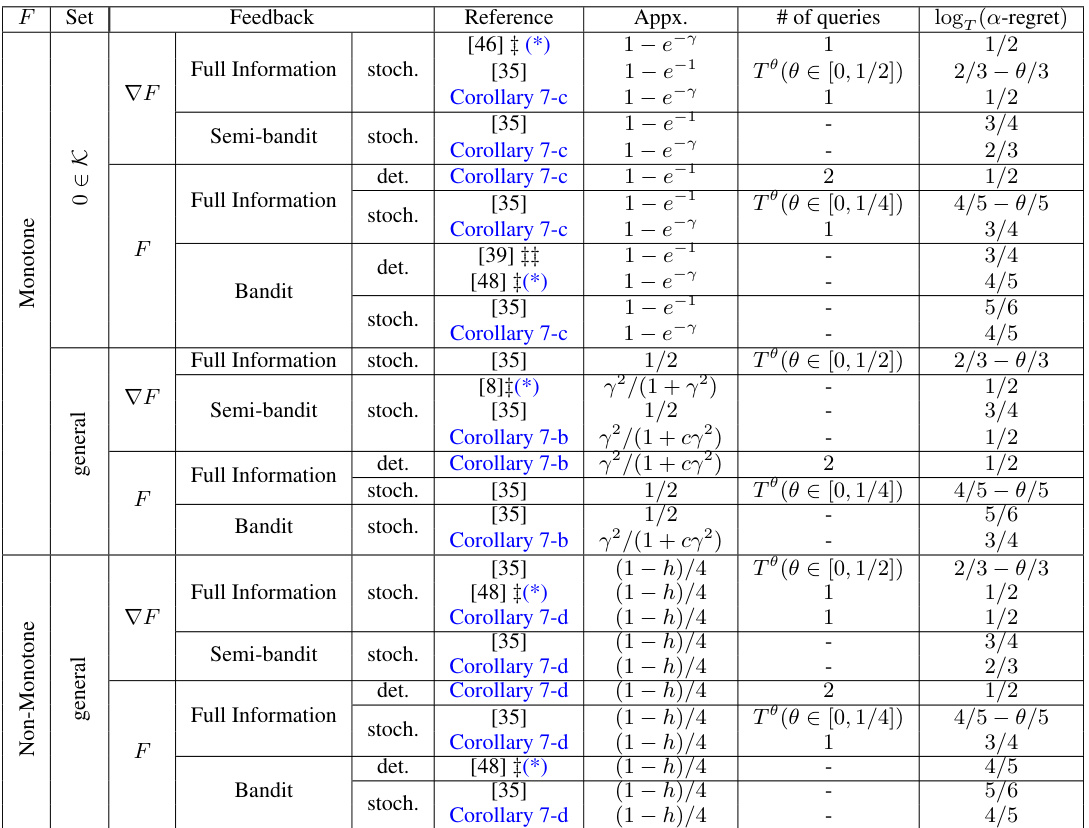

This table summarizes the results of different algorithms for online up-concave maximization problems. It compares various algorithms across different feedback types (full information, semi-bandit, bandit), function monotonicity (monotone, non-monotone), and constraint set properties (general convex set, convex set containing origin). The table shows the approximate static regret achieved by each algorithm, along with the number of queries used and relevant references. The results are categorized according to function class properties and information feedback. The table highlights the differences in performance metrics depending on the assumptions made about the function being maximized and the type of information available to the algorithm.

In-depth insights#

Linearizable Functions#

The concept of “linearizable functions” extends the applicability of linear optimization techniques to a broader class of problems. It bridges the gap between well-understood linear/quadratic optimization and more complex non-convex settings. By approximating non-linear functions with linear or quadratic surrogates, this framework allows the application of existing, efficient algorithms developed for simpler optimization problems. This is particularly useful for tackling concave and DR-submodular optimization, providing a unified approach across various scenarios (monotone/non-monotone, different feedback mechanisms). This framework’s strength lies in its generalization capability, reducing complex non-linear problems to linear forms, thus simplifying analysis and algorithm design. However, the quality of the approximation heavily influences the performance and error bounds; a careful analysis of error incurred due to linearization is crucial for evaluating its practical value. The choice of linearization method and its impact on the convergence rate and accuracy of the resulting algorithm must be thoroughly investigated.

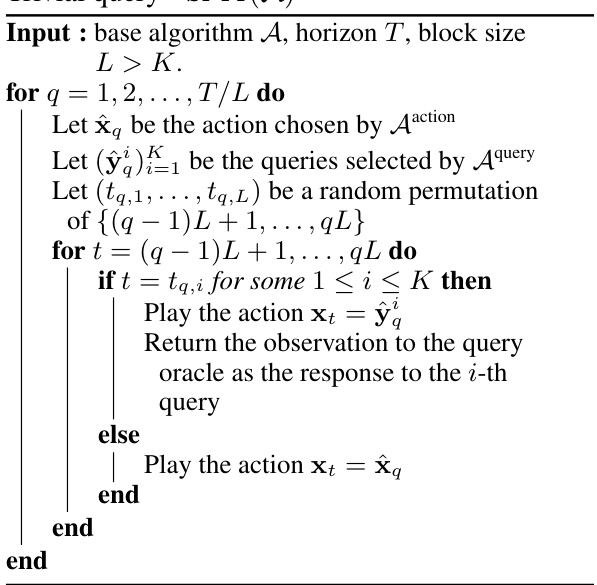

Meta-Algorithm Design#

The concept of ‘Meta-Algorithm Design’ in the context of this research paper likely revolves around creating a high-level framework or algorithm that can adapt or be applied to a wide range of specific optimization problems. This approach is particularly powerful when dealing with complex, non-convex optimization landscapes like those involving DR-submodular or up-concave functions. The core idea is to leverage existing algorithms designed for simpler problems (e.g., linear or quadratic optimization) as building blocks, which are then cleverly adapted through the meta-algorithm to tackle more challenging scenarios. This adaptability is crucial, as it avoids the need to design entirely new algorithms from scratch for every specific variation of the non-convex problems under consideration. A key benefit is increased efficiency and reduced development time, since the focus shifts from reinventing the wheel to efficiently adapting existing solutions. A well-designed meta-algorithm will likely incorporate techniques that handle various feedback mechanisms (bandit, semi-bandit, full information), providing a flexible and robust optimization framework. This modular approach is elegant and efficient; however, its success relies heavily on the carefully engineered design of the meta-algorithm itself, demanding a rigorous theoretical analysis to ensure its effectiveness and derive performance guarantees.

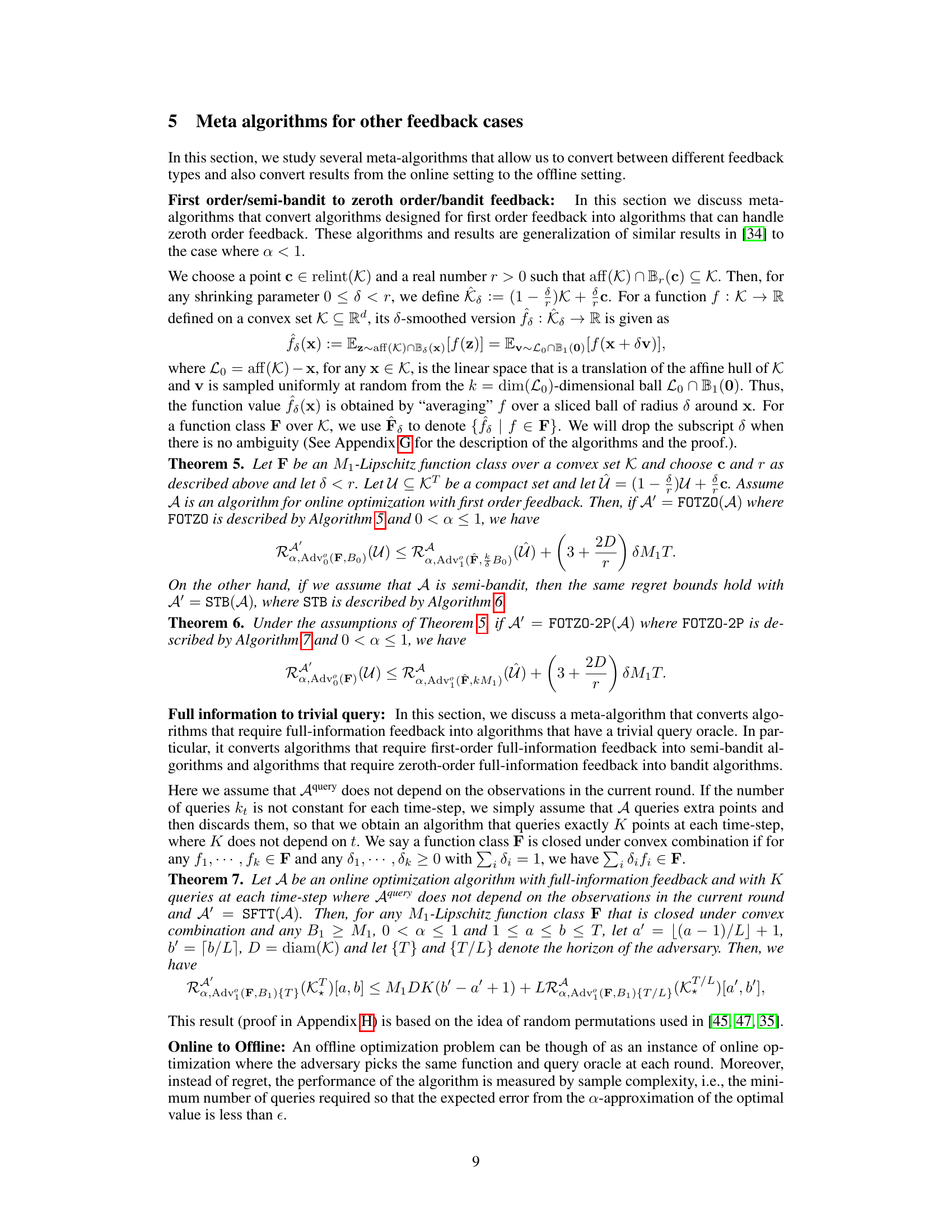

Feedback Conversions#

The concept of ‘Feedback Conversions’ in a machine learning context centers on adapting algorithms designed for one type of feedback to function effectively with another. This is crucial because different feedback mechanisms (full-information, bandit, semi-bandit) provide varying levels of information about the environment. Converting between these feedback types allows researchers to leverage the strengths of algorithms optimized for specific feedback scenarios in broader applications. For example, an algorithm initially designed for full-information feedback (where the reward function is fully known) might be adapted to work with bandit feedback (where only the reward for the selected action is revealed). This adaptation requires careful design of a conversion process, often involving techniques like importance sampling or smoothing to estimate missing information. The success of such conversions depends on the nature of the reward function and the ability of the conversion method to accurately bridge the information gap between feedback types, ultimately influencing the efficiency and theoretical guarantees of the resulting algorithm. This is a key area of research, enabling the wider applicability of sophisticated algorithms developed for simpler settings.

DR-Submodular Results#

The DR-submodular results section would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed algorithms’ performance against existing state-of-the-art methods. Key metrics such as static, dynamic, and adaptive regret should be thoroughly analyzed across various feedback settings (full-information, semi-bandit, bandit). The analysis needs to highlight the advantages of the new framework, particularly in scenarios with fewer assumptions or improved regret bounds. A crucial aspect would be showcasing how the meta-algorithm effectively converts algorithms designed for simpler problems (like linear or quadratic optimization) into efficient solvers for DR-submodular problems, demonstrating its versatility and broad applicability. Tables summarizing the regret results for different function classes (monotone, non-monotone) and feedback types would be essential for a clear and concise presentation. It’s also important to discuss any limitations of the results, such as assumptions on function smoothness or the type of convex sets considered, as well as directions for future research.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extensions to more complex function classes, moving beyond DR-submodularity and up-concavity. Investigating the theoretical limits and practical implications of the meta-algorithms under diverse settings, including scenarios with noisy feedback or non-stationary environments, would be highly valuable. A key area for future work is to develop more efficient and scalable algorithms, particularly addressing the computational costs associated with projection-free methods or high-dimensional data. Additionally, empirical evaluations on real-world datasets, across various applications, are crucial to assess the performance and generalizability of the proposed framework. Finally, the exploration of connections to other optimization paradigms, such as stochastic optimization or reinforcement learning, promises exciting avenues for future research.

More visual insights#

More on tables

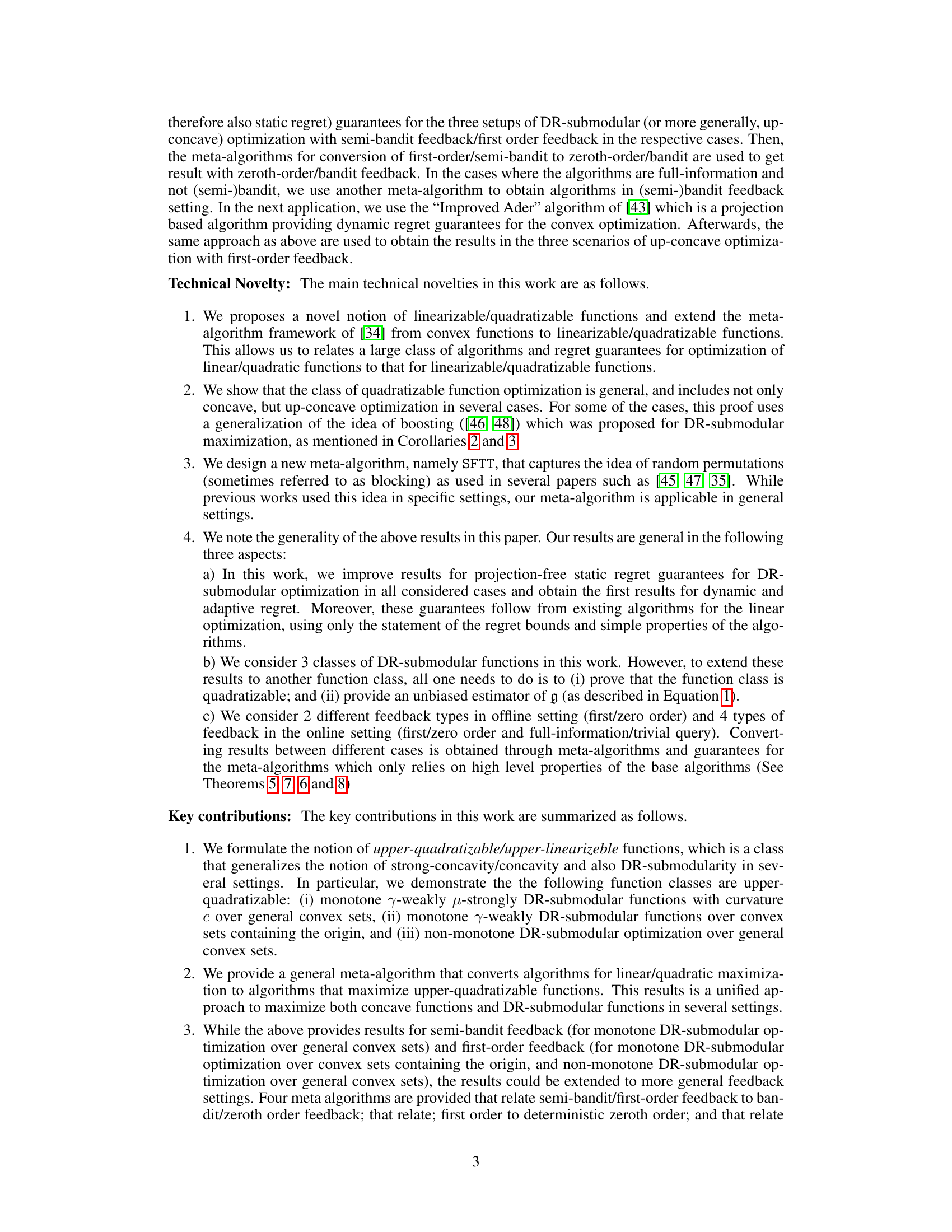

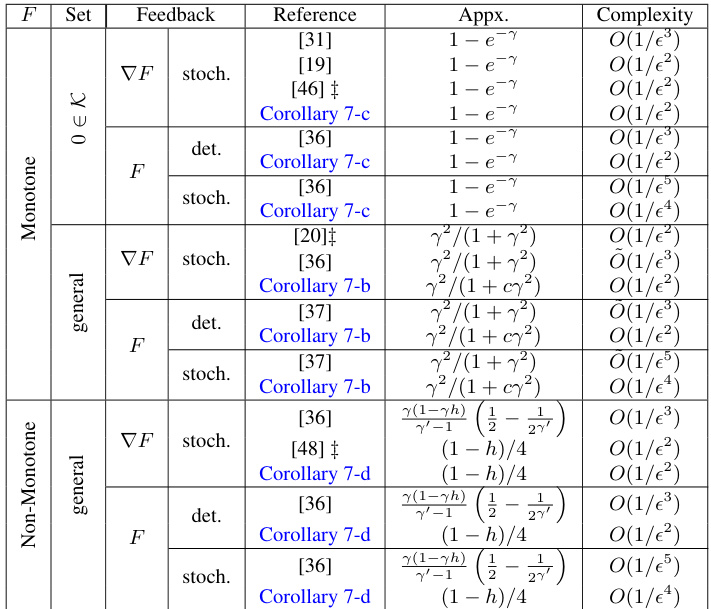

This table compares different offline regret results for the online up-concave maximization problem. The results are categorized by the type of feedback (full information, semi-bandit, or bandit), whether the function is monotone or not, and the type of algorithm (projection-based or projection-free). The table also shows the approximate complexity and the achieved regret bound for each setting.

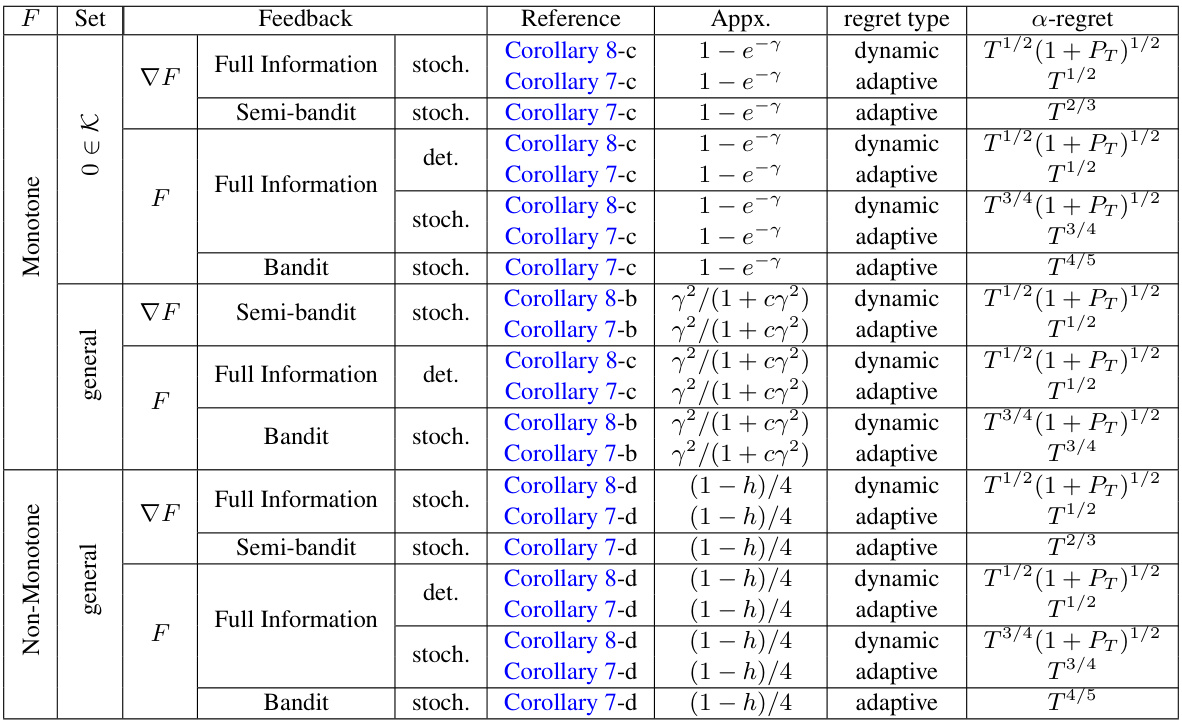

This table presents the dynamic and adaptive regret bounds for non-stationary online up-concave maximization problems under various feedback settings (full information, semi-bandit, and bandit). It categorizes results based on the monotonicity of the function (monotone or non-monotone) and the type of convex set (general convex set or convex set containing the origin). The regret bounds are expressed in terms of the time horizon T and the path length PT.

This table summarizes the results of online up-concave maximization under various settings. The rows represent different types of up-concave functions (monotone or non-monotone), feedback mechanisms (full information, semi-bandit, or bandit), and whether the results are stochastic or deterministic. The columns show the reference for the result, an approximation of the regret, and the number of queries needed. The table helps in comparing different algorithms’ performance under various scenarios.

This table compares different static regret results for online up-concave maximization problems. It shows the regret bounds achieved by various algorithms under different feedback mechanisms (full information, semi-bandit, bandit), function types (monotone, non-monotone), and constraint sets. The table highlights the number of queries needed by each algorithm and provides references to the corresponding literature.

This table compares different static regret results for online up-concave maximization problems. It showcases the performance of various algorithms under different feedback settings (full information, semi-bandit, bandit), function types (monotone, non-monotone), and whether they use projection or projection-free methods. The logarithmic terms are ignored for simplicity. The table helps in evaluating the trade-offs between different algorithmic approaches and feedback mechanisms in solving adversarial up-concave optimization.

This table compares different static regret results for online up-concave maximization problems under various settings. The settings include different feedback types (full information, semi-bandit, bandit), function characteristics (monotone, non-monotone), and algorithm types (projection-free, projection-based). The results highlight the number of queries required and the achieved regret bounds. Logarithmic terms are ignored for simplicity. The table provides a comparison of the paper’s results to the existing state-of-the-art, showcasing improvements and broader applicability.

Full paper#