↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Finetuning large language models (LLMs) in federated learning (FL) is challenging due to high memory demands, particularly on resource-constrained edge devices. Existing methods, such as backpropagation, require excessive memory, while zero-order methods suffer from slow convergence and accuracy issues. Forward-mode auto-differentiation (AD) shows promise in reducing memory, but its direct application to LLM finetuning leads to poor performance.

The paper introduces SPRY, a novel FL algorithm that addresses these challenges. SPRY splits the trainable weights of an LLM among participating clients, allowing each client to compute gradients using forward-mode AD on a smaller subset of weights. This strategy reduces the memory footprint, improves accuracy, and accelerates convergence. SPRY’s effectiveness is demonstrated empirically across a wide range of language tasks, models, and FL settings, showcasing its significant memory and computational efficiency improvements over existing methods. Theoretical analysis supports its unbiased gradient estimations under homogeneous data distributions, highlighting its practical value.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on federated learning and large language models. It presents a novel and efficient algorithm, addressing a critical challenge in the field—the high memory consumption of finetuning LLMs on resource-constrained devices. The findings significantly advance the feasibility of deploying LLMs in various resource-scarce settings and encourage further research into memory-efficient training strategies for large models.

Visual Insights#

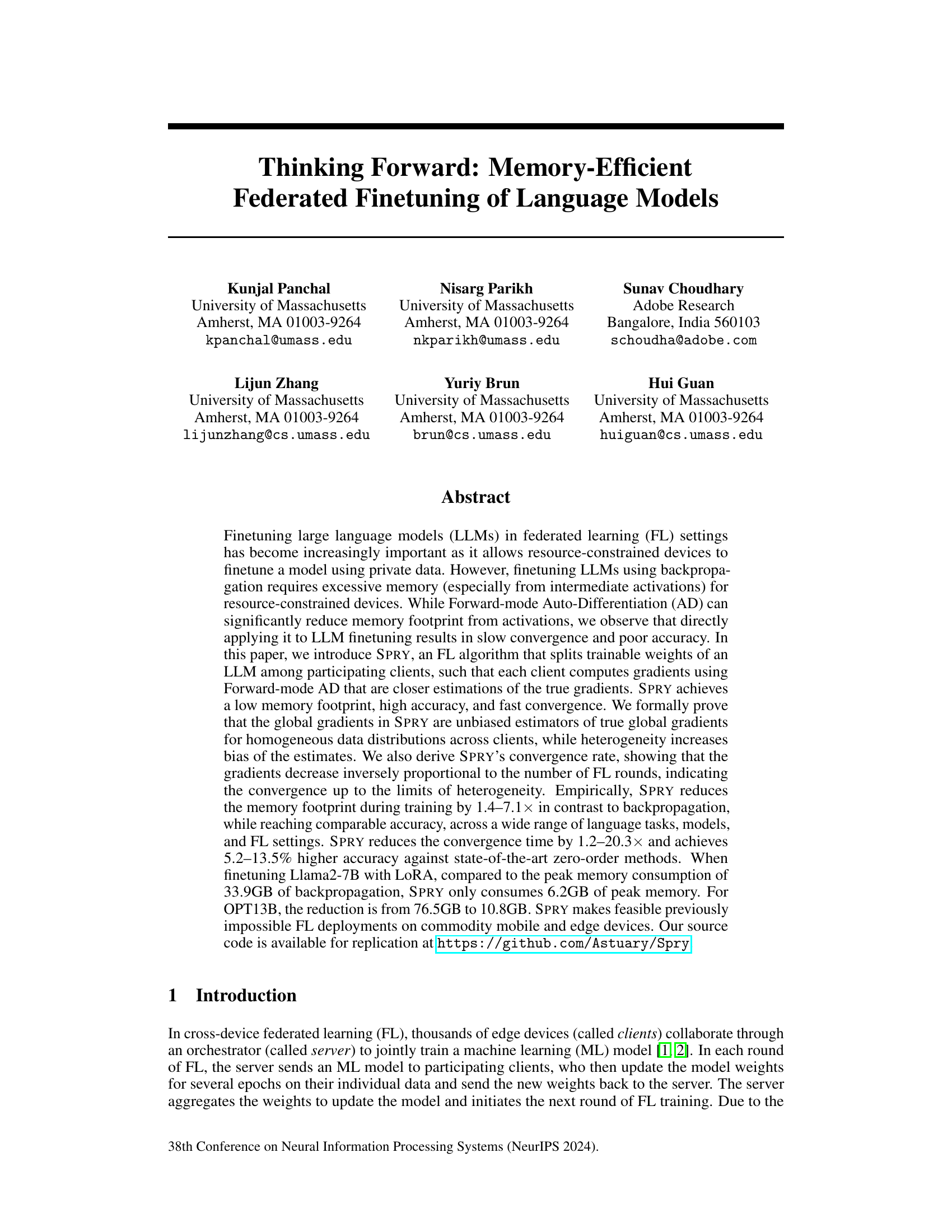

This figure illustrates the workflow of the SPRY algorithm. It starts with a language model whose backbone is frozen, and only PEFT (parameter-efficient fine-tuning) weights are trainable. These trainable weights are split across multiple clients. The server sends the frozen weights and a subset of trainable weights along with a seed to each client. Each client then uses forward-mode auto-differentiation to compute the Jacobian-vector product (JVP) and updates its assigned weights. Finally, the server aggregates the updated weights from all clients to update the global model.

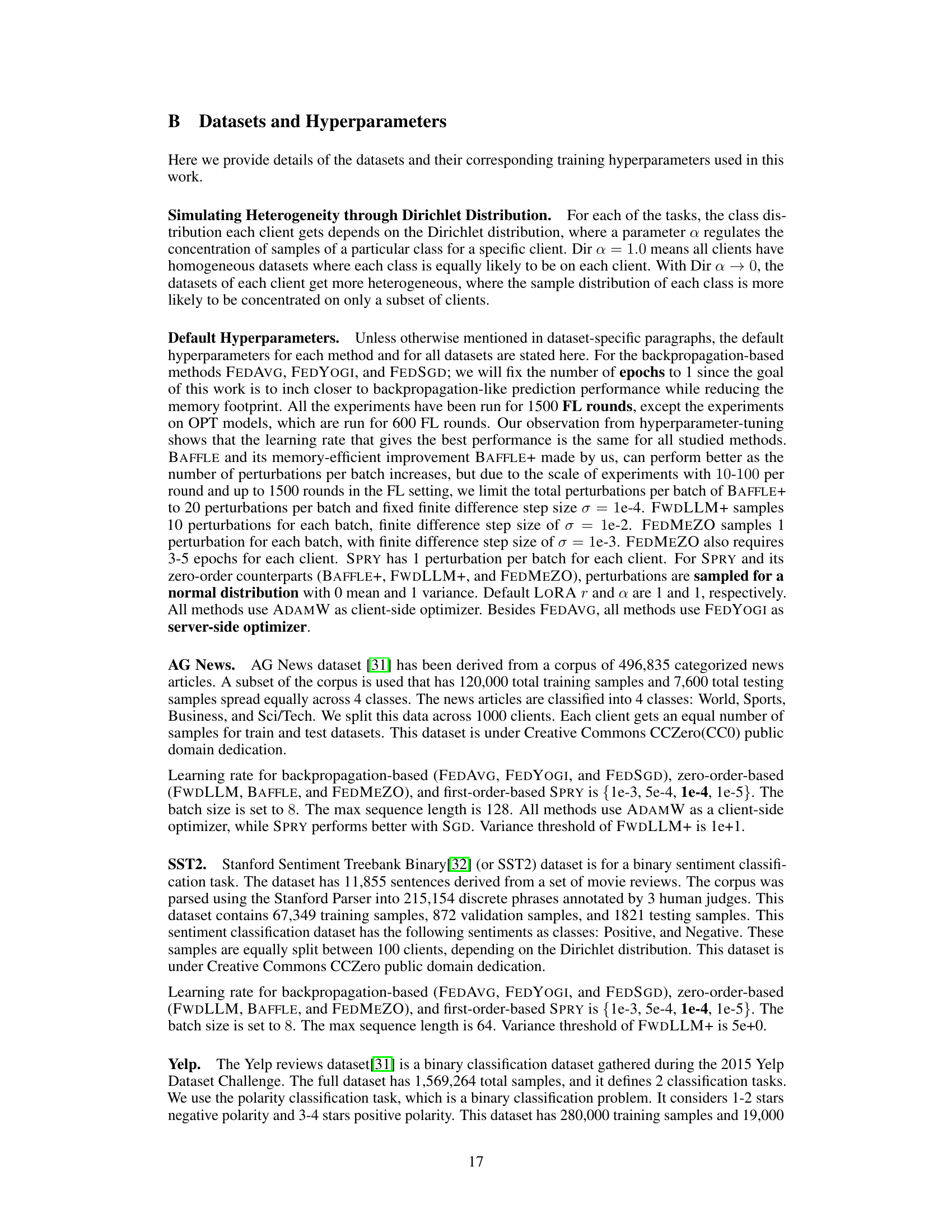

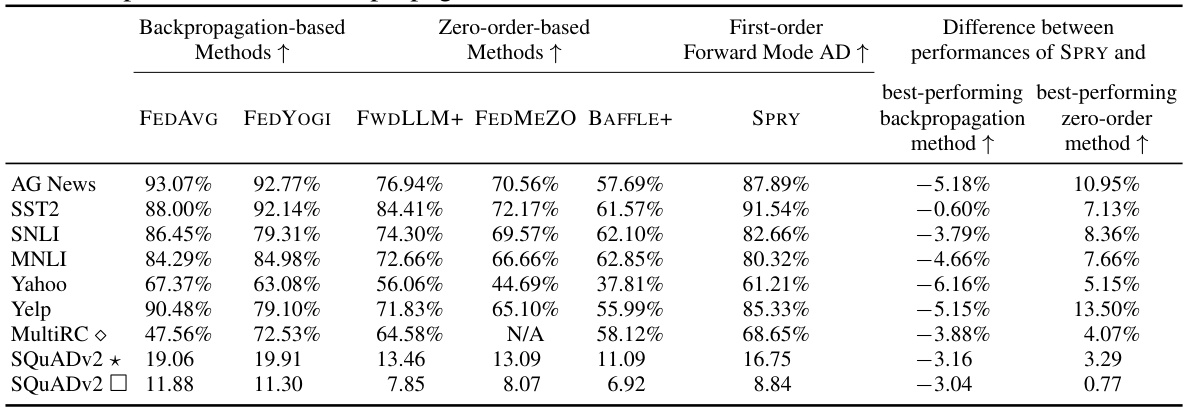

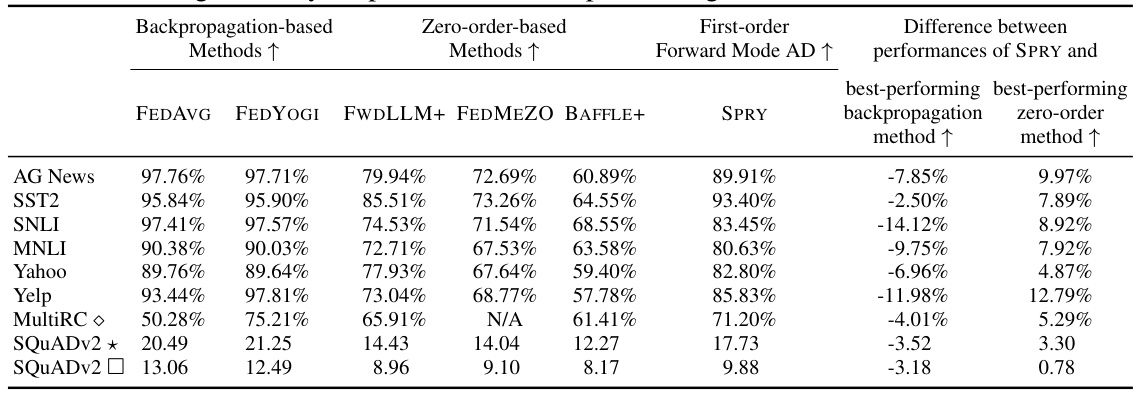

This table presents a comparison of the generalized accuracy achieved by SPRY against backpropagation-based and zero-order-based methods across various datasets and language models. It highlights SPRY’s superior performance, particularly against zero-order methods (5.15-13.50% improvement), and its competitiveness with backpropagation-based methods (within 0.60-6.16%). The table includes results for different language models (RoBERTa Large, Llama 2, OPT6.7B, OPT13B) and a variety of tasks, showcasing SPRY’s effectiveness across various settings.

In-depth insights#

Memory-Efficient FL#

The concept of “Memory-Efficient FL” centers on optimizing federated learning (FL) algorithms to minimize memory consumption, particularly crucial for resource-constrained edge devices. This is achieved through various techniques, including the strategic use of forward-mode automatic differentiation (AD), which avoids the need to store intermediate activation values during backpropagation. By splitting trainable weights among clients, each device handles a smaller portion, further reducing the memory burden. This approach, while potentially introducing bias in gradient estimates, particularly in scenarios with heterogeneous data distributions, can be mitigated through careful algorithm design. The trade-off between memory efficiency and model accuracy is a key consideration; while memory efficiency is prioritized, it is important to ensure minimal performance degradation. Formal analysis, including proofs of unbiasedness for homogeneous data and convergence rate estimations, often accompanies these methods. Empirical evaluations on varied language models and datasets are essential to demonstrate the practical effectiveness of such memory-efficient techniques, often showcasing significant memory footprint reductions while maintaining comparable accuracy to traditional approaches.

SPRY Algorithm#

The SPRY algorithm tackles the memory-intensive challenge of finetuning large language models (LLMs) within federated learning (FL) settings. Its core innovation lies in splitting the LLM’s trainable weights across multiple clients, each handling a subset. This dramatically reduces the memory demands on individual devices, making FL more practical for resource-constrained environments. Instead of traditional backpropagation, SPRY uses forward-mode automatic differentiation (AD), further minimizing memory consumption by avoiding the need to store intermediate activations. While forward-mode AD alone can be slow and inaccurate, SPRY’s clever weight-splitting strategy ensures each client computes gradients based on a smaller, manageable weight subset. The resultant gradients are then aggregated by a central server. Theoretical analysis proves SPRY’s unbiased gradient estimation for homogeneous data distributions, highlighting that heterogeneity introduces bias. The algorithm’s convergence is also shown to be inversely proportional to the number of federated learning rounds. Empirical evaluations demonstrate SPRY’s superiority in memory efficiency and speed compared to backpropagation and other zero-order methods, showing significant gains in accuracy and convergence while maintaining relatively low communication overhead.

Theoretical Analysis#

The theoretical analysis section of this research paper on memory-efficient federated fine-tuning of language models is crucial for understanding SPRY’s performance and limitations. It rigorously examines SPRY’s convergence rate, demonstrating that the global gradients decrease inversely proportional to the number of federated learning rounds. This is particularly important for resource-constrained devices, showing its efficiency. The analysis also investigates the impact of data heterogeneity on the accuracy of gradient estimations, formally proving that SPRY’s global gradient estimations are unbiased for homogeneous data but become increasingly biased with data heterogeneity. This highlights the trade-off between memory efficiency and the robustness of SPRY in diverse real-world settings. The theoretical analysis is accompanied by a derivation of SPRY’s convergence rate, providing further insights into its performance and potentially guiding hyperparameter selection for optimal results. The combination of convergence rate analysis and an unbiasedness proof under homogeneity makes this a strong theoretical foundation for the proposed algorithm. The formal proofs and analysis contribute significantly to the trustworthiness of SPRY and demonstrate the researchers’ rigorous approach towards validating their method.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of this research paper, ablation studies likely investigated the impact of specific design choices within the SPRY framework. This might include assessing the effects of using different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, varying communication frequencies in the federated learning process, altering the number of trainable weights or the number of clients participating in each round, and examining the impact of the layer-splitting strategy. The results from these experiments would help determine the relative importance of different architectural components and algorithmic choices and would be used to support the effectiveness of the overall method. The key insight here is to gauge the influence of each component on both accuracy and efficiency to optimize the design. Analyzing this section would provide a detailed understanding of the model’s sensitivity to each variable and its contribution to the overall system’s performance. Understanding such sensitivity helps to isolate important features and provides insights into how to further refine the model in future iterations. The ablation study section is crucial in supporting the robustness and validity of the results presented in the paper. It allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the overall methodology and strengthens the overall findings.

Future of SPRY#

The future of SPRY hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving the computational efficiency of forward-mode AD is crucial, potentially through optimized implementations or hardware acceleration. This would significantly enhance SPRY’s speed and practicality for real-world applications. Reducing the memory footprint further, perhaps by exploring more sophisticated weight-splitting techniques or advanced memory management strategies, is another key area. Addressing the limitations imposed by data heterogeneity, particularly through theoretical advancements and algorithm refinements, will be essential for broader applicability and robustness. Exploring SPRY’s integration with other PEFT methods beyond LORA could uncover even greater potential for accuracy and efficiency. Finally, rigorous testing across a wider range of LLM architectures, datasets, and federated learning environments is vital to solidify SPRY’s position as a leading method for memory-efficient federated finetuning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

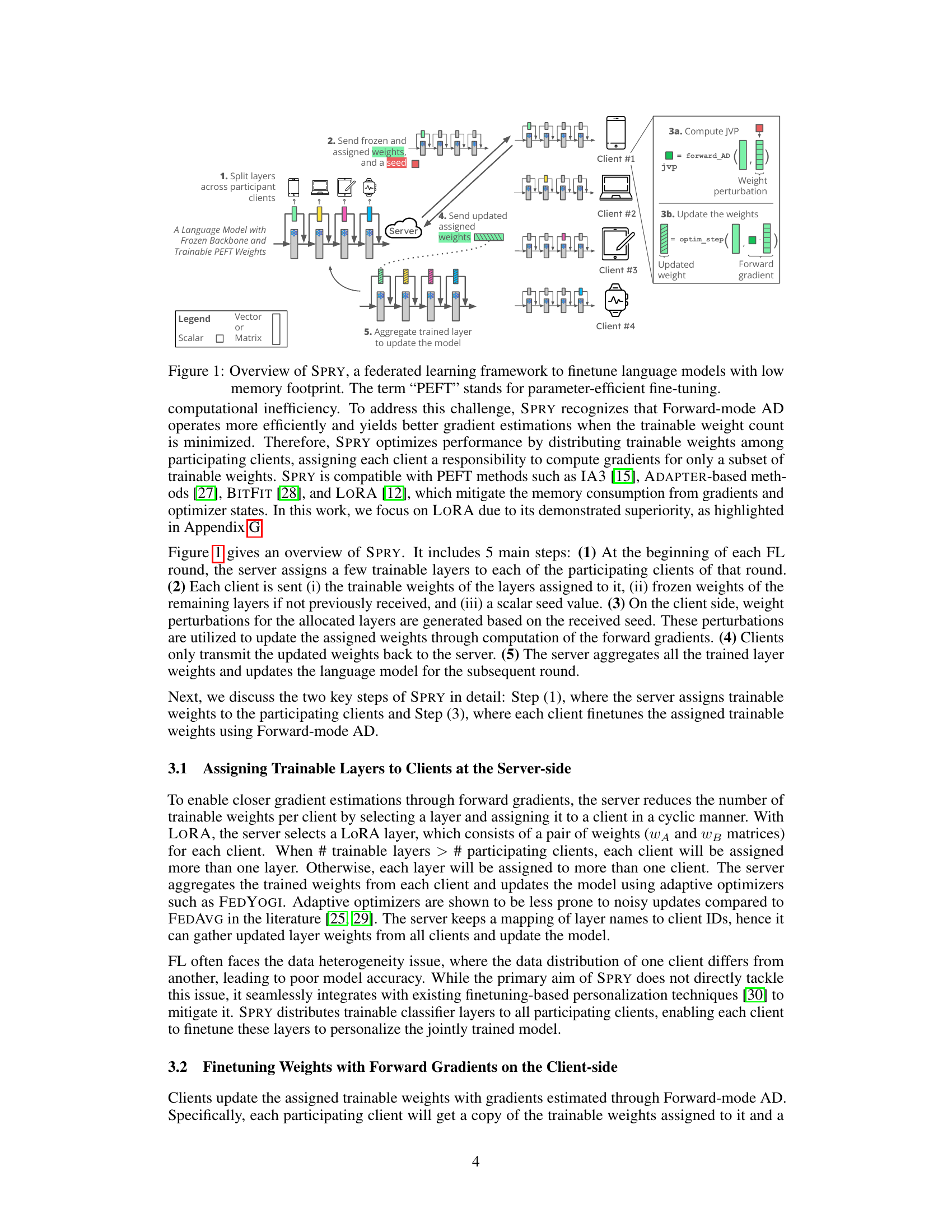

This figure compares the peak memory usage of different gradient computation methods: backpropagation, zero-order finite difference methods, and SPRY’s first-order forward mode AD. For four different language models (RoBERTa-Large, Llama2-7B, OPT6.7B, and OPT13B), the figure shows a breakdown of memory usage into parameters, activations, gradients+optimizer states, and miscellaneous. SPRY significantly reduces memory consumption compared to backpropagation, with the savings primarily attributed to reduced memory requirements for activations. The slight increase in memory usage compared to zero-order methods is justified by the resulting accuracy improvements.

This figure compares the peak memory consumption of SPRY (using Forward-mode AD) against backpropagation and zero-order methods across four different language models: RoBERTa Large, Llama2-7B, OPT6.7B, and OPT13B. SPRY shows significant memory reduction compared to backpropagation, ranging from 27.9% to 86.26%. While SPRY uses slightly more memory than zero-order methods in some cases, the performance gains (as described in Section 5.1) outweigh this difference.

This figure illustrates the workflow of SPRY, a memory-efficient federated learning framework designed for finetuning large language models. The framework involves five main steps: 1) The server assigns trainable layers to participating clients, ensuring each client handles a small subset. 2) The server sends these assigned weights, along with frozen weights for other layers, and a seed value to each client. 3) Clients use forward-mode AD to generate gradients based on weight perturbations derived from the seed. 4) Clients only return updated weights. 5) The server aggregates all updates to adjust the global model. This design minimizes each client’s memory consumption, enhancing efficiency and accuracy.

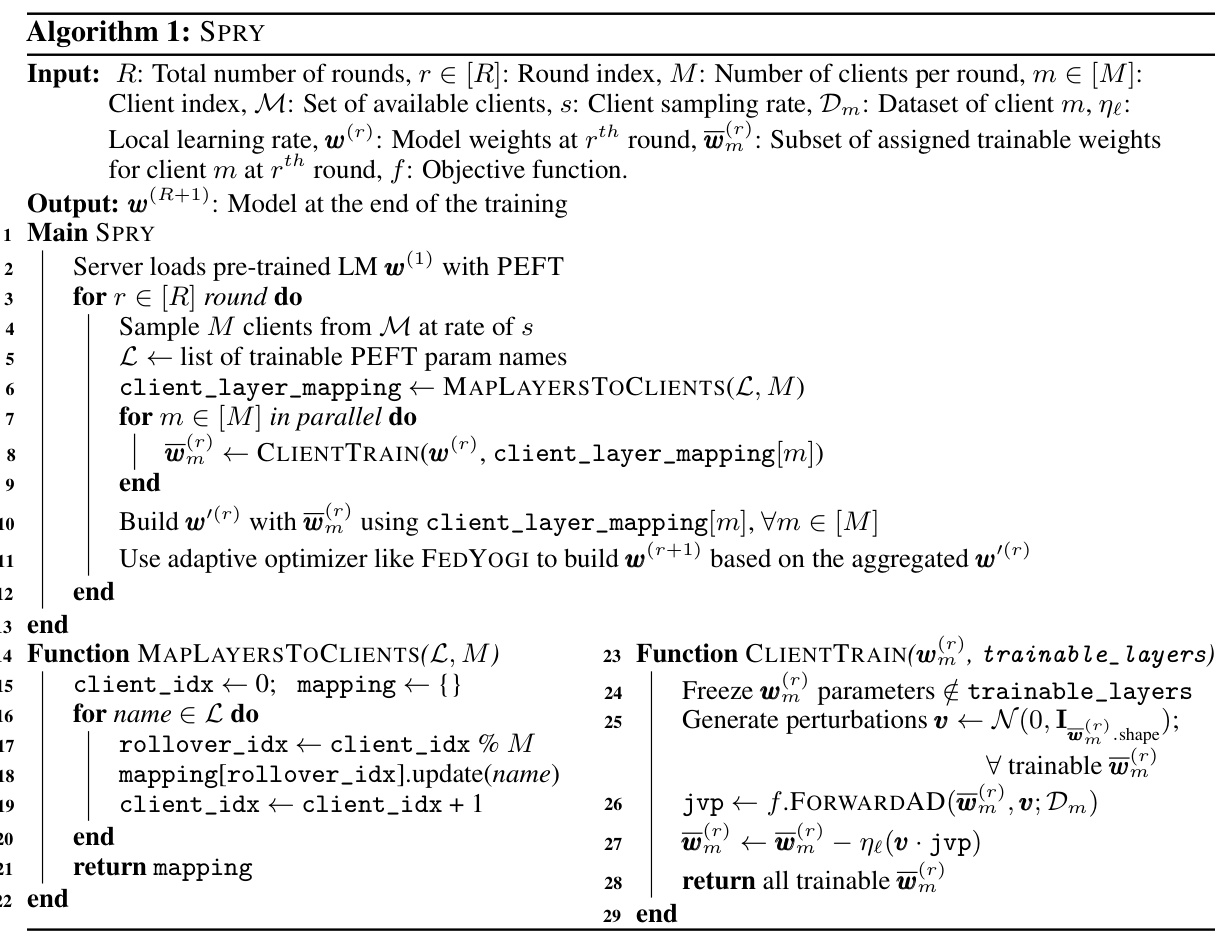

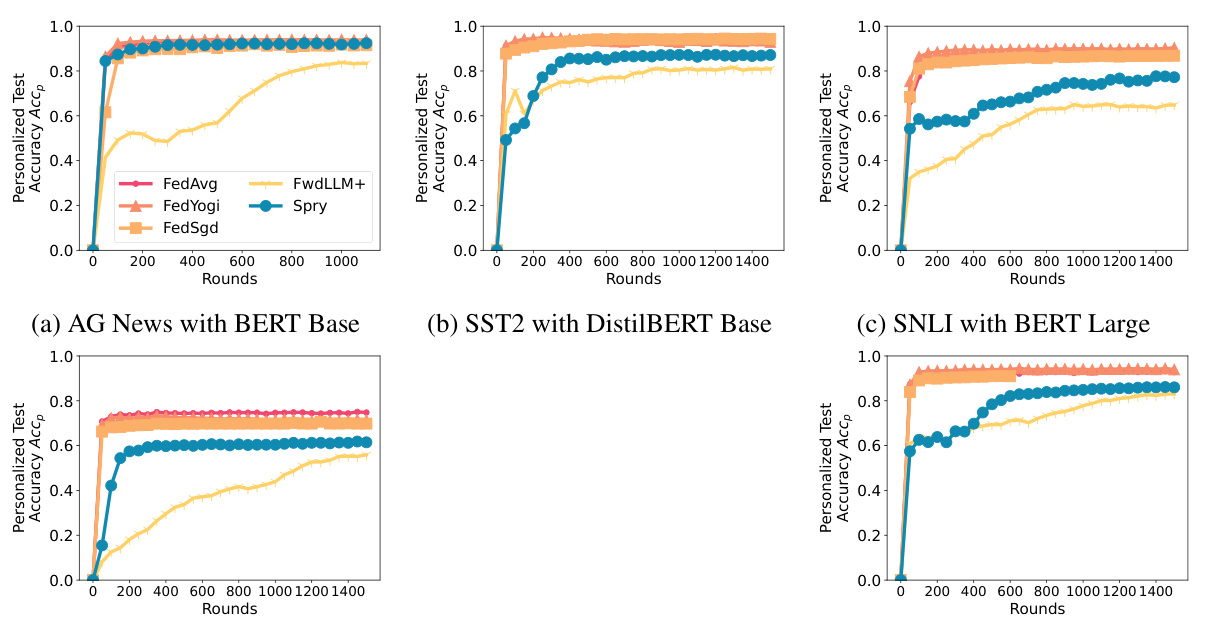

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY to analyze the impact of various components on its performance. Three subfigures are shown: (a) Effect of different PEFT methods on SPRY: Compares the performance of SPRY when integrated with different Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods like LORA, BitFit, IA3, and Classifier-only finetuning. LORA shows superior performance compared to other methods. (b) Effect of per-epoch and per-iteration communication: Contrasts the performance of SPRY with per-epoch and per-iteration communication frequencies against FEDAVG and FEDSGD. Per-iteration shows better accuracy. (c) Changing LORA r and α for SPRY: Illustrates how varying the rank (r) and scale (α) hyperparameters in the LORA technique influence SPRY’s performance.

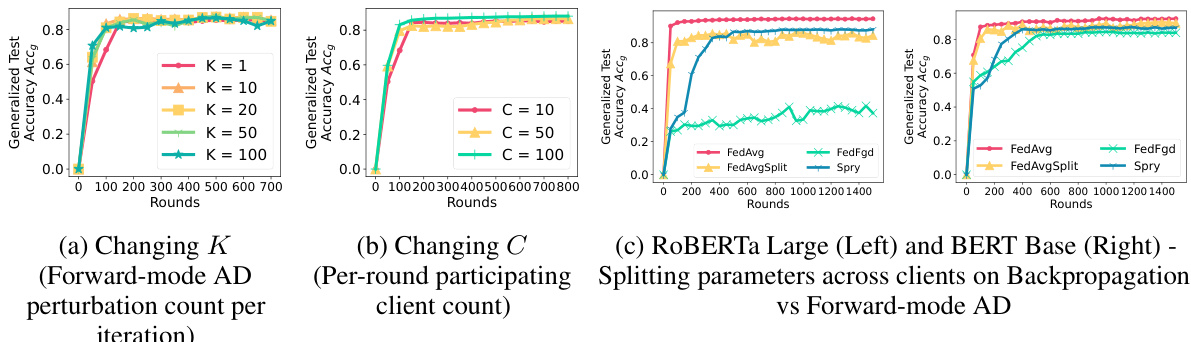

This figure presents ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of various factors on SPRY’s performance. Specifically, it examines the effects of (a) varying the number of perturbations per batch (K) used in the Forward-mode AD, showing that increasing K beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns in terms of accuracy but improves convergence speed; (b) altering the number of participating clients (C) per round, demonstrating that increasing C enhances both accuracy and convergence; and (c) comparing the effects of applying the weight splitting strategy across clients to both backpropagation-based methods and the Forward-mode AD-based SPRY. The results illustrate the importance of the weight splitting strategy in achieving the improved memory efficiency and performance of SPRY.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of various components of SPRY on its performance. Panel (a) compares the performance of SPRY using different Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods: LORA, IA3, BitFit, and a classifier-only approach. Panel (b) contrasts the performance of SPRY with per-epoch and per-iteration communication strategies. Panel (c) examines the influence of different hyperparameter settings for LORA (r and α) on SPRY’s performance. These studies provide insights into the optimal configuration of SPRY for different tasks and model architectures.

This figure presents the ablation study results on SPRY’s performance. The impact of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods (LORA, IA3, BITFIT, and classifier-only), communication frequency (per-epoch vs. per-iteration), and LORA hyperparameters (r and α) on the generalized test accuracy is shown in three subfigures. The results show that LORA with SPRY performs the best, achieving high accuracy. Per-iteration communication boosts accuracy, and the choice of LORA hyperparameters significantly affects the model’s performance.

This figure presents ablation studies on various components of SPRY. The leftmost plot shows the impact of different Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods, namely LORA, BitFit, IA3, and classifier-only finetuning, on the generalized test accuracy. The middle plot shows the effect of communication frequency (per-epoch versus per-iteration) on the generalized test accuracy. The rightmost plot illustrates how changes to the LORA hyperparameters (r and α) affect the generalized test accuracy. These ablation studies help to analyze the contribution and importance of different aspects of SPRY to its overall performance.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on SPRY. Panel (a) compares the performance of SPRY using different Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods: LORA, IA3, BitFit, and Classifier-Only. Panel (b) shows the impact of communication frequency (per-epoch vs. per-iteration) on SPRY’s performance, also comparing to FEDAVG and FEDSGD. Finally, panel (c) illustrates how changing the hyperparameters r and α in the LORA method affects SPRY’s performance. The results demonstrate the impact of different components on SPRY’s overall effectiveness and efficiency.

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY, showing the impact of different components on its performance. Panel (a) compares the generalized test accuracy of SPRY using different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods such as LORA, IA3, BitFit, and a classifier-only approach. Panel (b) compares the performance of SPRY using per-epoch and per-iteration communication strategies. Finally, panel (c) shows how changing the rank (r) and scaling (α) hyperparameters within the LORA technique affects the performance of SPRY.

This figure presents ablation studies on three aspects of SPRY: parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, communication frequency, and the hyperparameters of Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). Subfigure (a) compares the performance of SPRY when using different PEFT methods (LoRA, BitFit, IA3, and Classifier-only), demonstrating LoRA’s superior performance. Subfigure (b) contrasts the per-epoch and per-iteration communication strategies in SPRY, revealing the improvement achieved by per-iteration communication. Finally, subfigure (c) illustrates how varying the rank (r) and scaling factor (α) hyperparameters in LoRA affects SPRY’s performance, highlighting the optimal settings for achieving the highest accuracy.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on various components of SPRY, a federated learning framework for finetuning language models. It showcases the impact of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, communication frequency (per-epoch vs. per-iteration), and LORA hyperparameters (rank and scaling factor) on SPRY’s performance. The subplots illustrate how each factor influences the generalized test accuracy. The results highlight the optimal configurations and the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches within SPRY.

This figure presents ablation studies performed on SPRY to analyze the impact of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, communication frequency (per-epoch vs. per-iteration), and LORA hyperparameters (r and α) on its performance. The subfigures showcase the effects of each parameter on the generalized test accuracy (Accg).

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on various components of SPRY to analyze their impact on the model’s performance. Specifically, it examines the effects of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods (LORA, IA3, BitFit, and classifier-only), the communication frequency (per-epoch and per-iteration), and different settings for the LORA hyperparameters (r and α). The x-axis represents the number of rounds, while the y-axis shows the generalized test accuracy (Accg).

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY, focusing on three key aspects: Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods, communication frequency, and LORA hyperparameters. Subfigure (a) compares the performance of SPRY when integrated with different PEFT methods (LORA, BitFit, IA3, and Classifier-only). Subfigure (b) contrasts the effects of per-epoch versus per-iteration communication frequencies. Subfigure (c) demonstrates how SPRY’s performance varies with different settings of the LORA hyperparameters (r and α). Each subfigure helps to understand the influence of different design choices on SPRY’s overall effectiveness.

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY. The subfigures show the impact of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods (LORA, BitFit, IA3, and classifier-only), communication frequency (per-epoch and per-iteration), and LORA hyperparameters (r and α) on the generalized test accuracy. The results demonstrate that LORA consistently outperforms other PEFT methods, while per-iteration communication and specific LORA hyperparameter settings improve performance.

This figure presents the ablation study results which are conducted to evaluate the impact of different components of SPRY on its performance. Three subfigures are included: (a) Effect of different PEFT methods on SPRY (b) Effect of per-epoch and per-iteration communication (c) Changing LORA r and α for SPRY. Each subfigure displays the generalized accuracy (Accg) against the number of rounds, showing the effects of different configurations on the model’s performance. This allows for a nuanced understanding of SPRY’s strengths and how to optimize its performance across various settings.

This figure presents ablation studies on three aspects of the SPRY model: parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, communication frequency, and LORA hyperparameters. Subfigure (a) compares the performance of SPRY using different PEFT methods (LORA, Bitfit, IA3, and Classifier-only). Subfigure (b) contrasts the performance of SPRY using per-epoch and per-iteration communication. Subfigure (c) illustrates the impact of varying the rank (r) and scale (α) hyperparameters within the LORA method on SPRY’s performance.

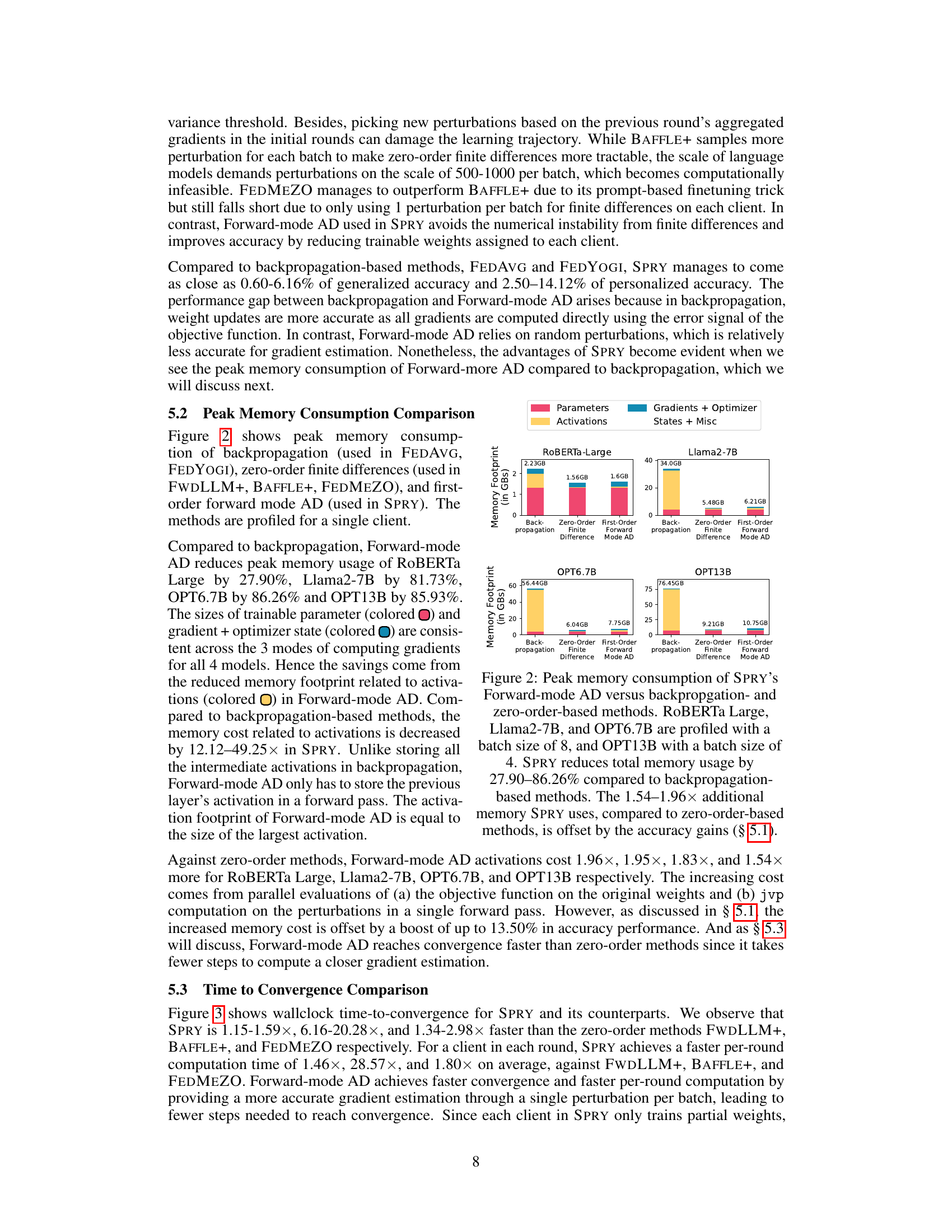

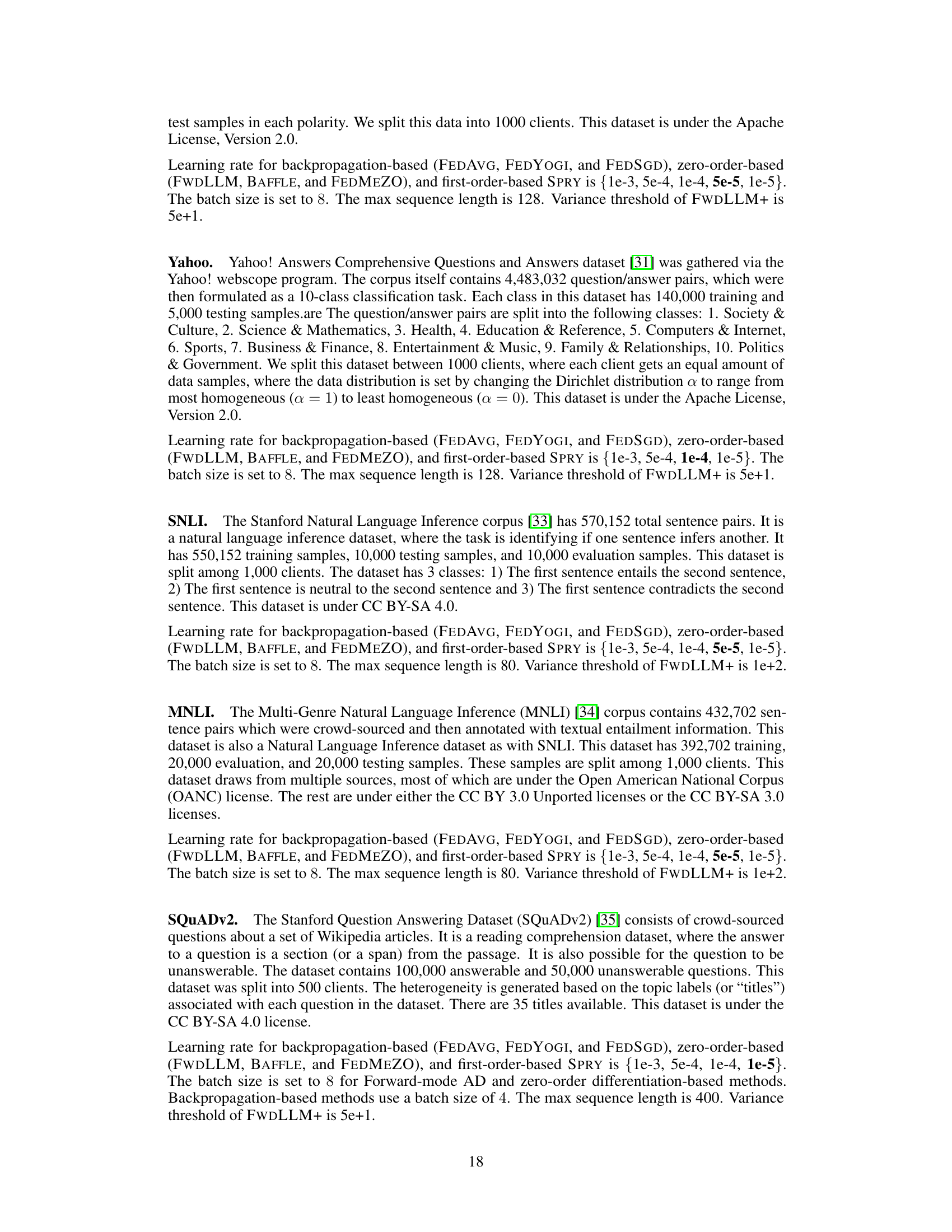

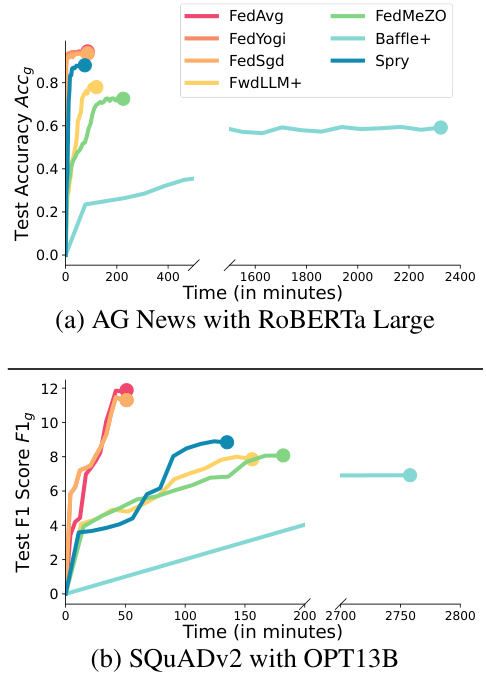

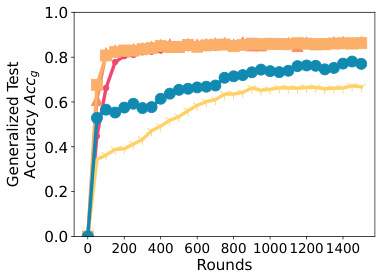

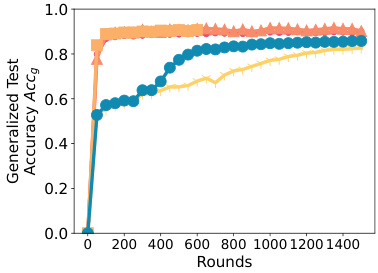

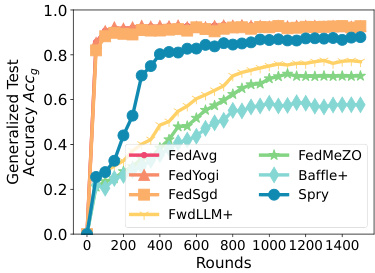

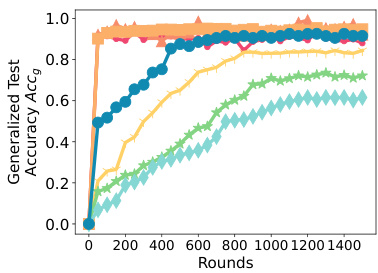

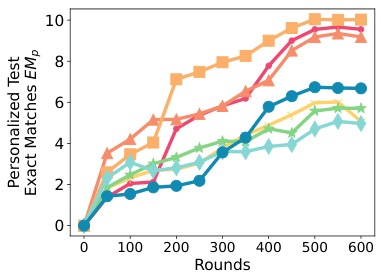

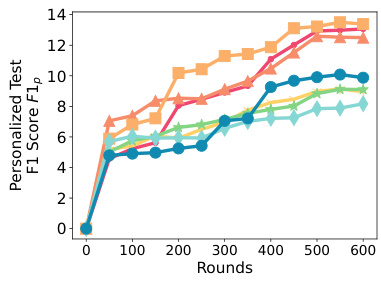

This figure compares the time it takes for different federated learning algorithms to converge on various language modeling tasks. The algorithms compared include SPRY (the proposed algorithm), FEDAVG, FEDYOGI, FEDSGD, FEDMEZO, BAFFLE+, and FWDLLM+. The x-axis represents the number of rounds in federated training, while the y-axis shows the time to convergence. The figure demonstrates that SPRY consistently converges faster than the zero-order methods (FEDMEZO, BAFFLE+, and FWDLLM+), highlighting its efficiency in reaching comparable accuracy with significantly reduced training time. The slight difference in performance compared to backpropagation-based methods is attributed to the use of forward gradients in SPRY.

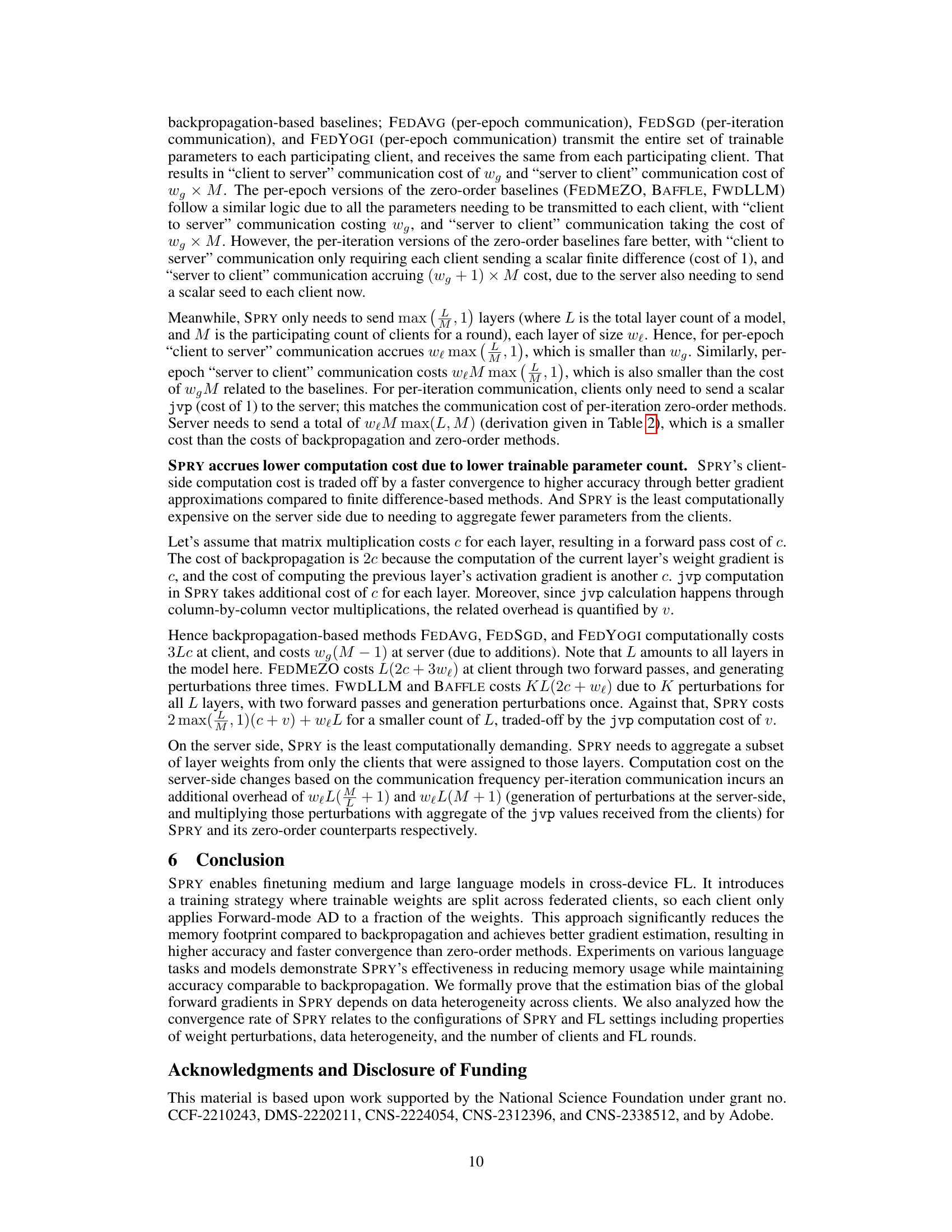

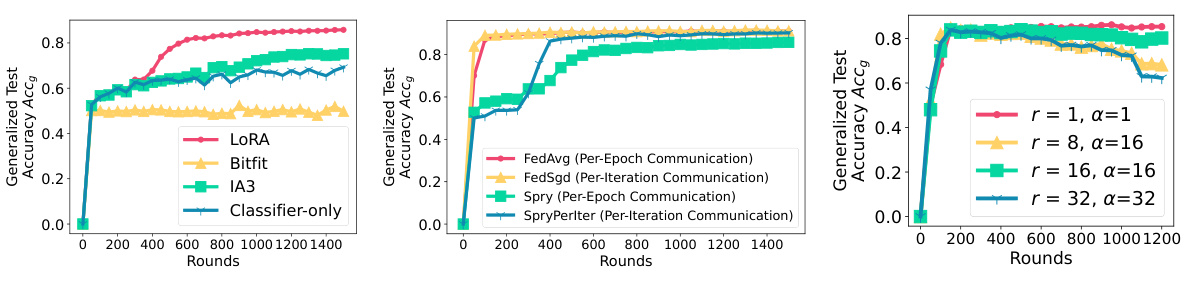

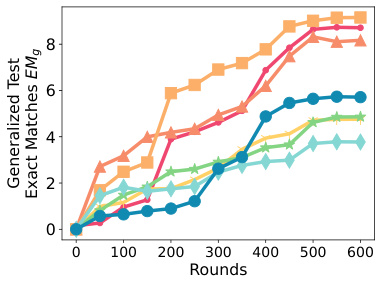

This figure presents ablation studies on three key aspects of the SPRY algorithm. Subfigure (a) shows how changing the number of perturbations (K) per batch impacts the model’s generalized accuracy, demonstrating diminishing returns with increasing K. Subfigure (b) illustrates the effect of varying the number of participating clients (C) per round, revealing that increasing C leads to performance gains, particularly in achieving a steady-state accuracy. Finally, subfigure (c) compares the performance of SPRY’s weight splitting strategy against backpropagation-based methods (FEDAVG, FEDAVGSPLIT) and a method lacking the splitting (FEDFGD). The results highlight the importance of the weight splitting for achieving comparable performance to backpropagation with far reduced memory consumption.

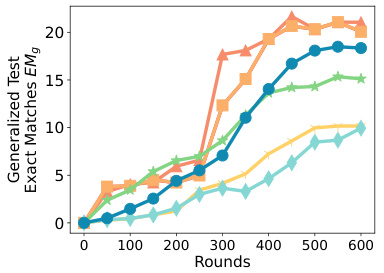

This figure compares the time to convergence for SPRY against its backpropagation-based and zero-order-based counterparts. The x-axis represents the number of rounds, and the y-axis represents the generalized F1 score. The figure shows that SPRY converges significantly faster than the zero-order methods (FWDLLM+, BAFFLE+, FEDMEZO), and slightly faster than FEDAVG, FEDYOGI, and FEDSGD. This improved convergence speed is attributed to SPRY’s more accurate gradient estimations using a single perturbation per batch, which reduces the number of steps required to reach convergence compared to the zero-order methods.

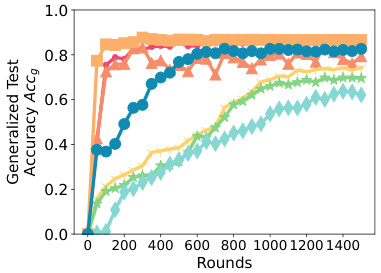

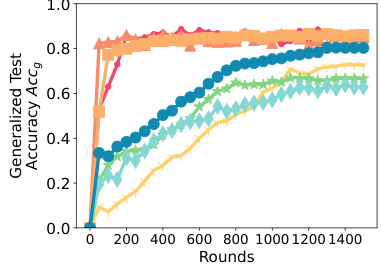

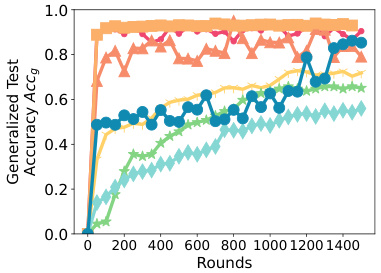

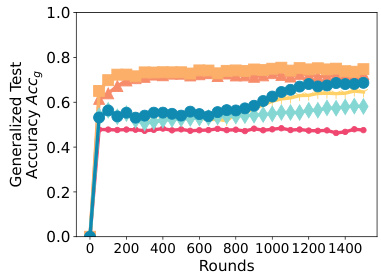

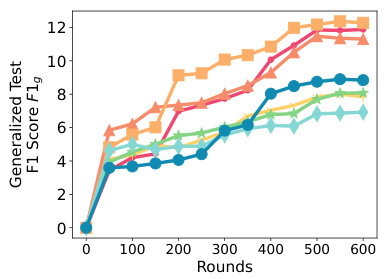

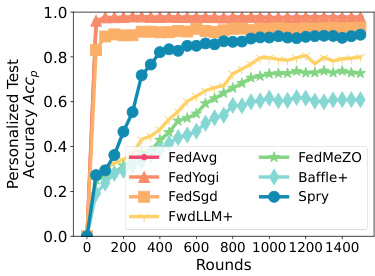

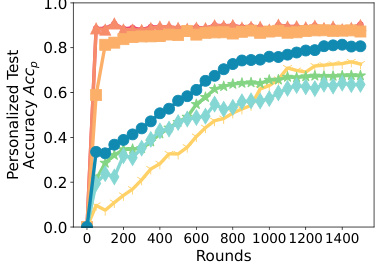

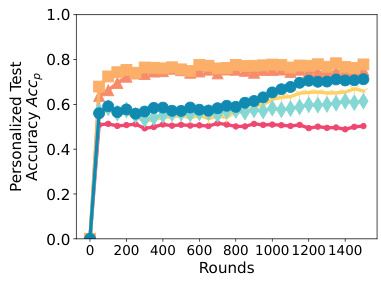

This figure displays the generalized test accuracy, F1 score, and exact matches for various language models and datasets. The x-axis represents the number of rounds, and the y-axis represents the performance metric. Different colored lines represent the performance of several different methods including FEDAVG, FEDYOGI, FEDSGD, FWDLLM+, FEDMEZO, BAFFLE+, and SPRY. The figure shows the performance on various classification tasks (AG News, SST2, SNLI, MNLI, Yahoo, Yelp) and question-answering tasks (MultiRC, SQUADv2). This is specifically for homogeneous data splits (Dirichlet a = 1.0).

This figure shows the ablation study results on three different aspects of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and the effect of splitting the trainable weights across the clients. For the first ablation (a), SPRY’s performance is examined with K values of 1, 10, 20, 50, and 100. The second ablation (b) investigates the impact of the number of participating clients per round (C) with values of 10, 50, and 100. The third ablation (c) compares the performance of SPRY against baselines (FEDAVG and FEDAVGSPLIT) that don’t split the trainable weights, and a baseline (FEDFGD) that doesn’t use the splitting strategy of SPRY. The results illustrate how these choices impact the accuracy of SPRY.

This figure presents the ablation study results for SPRY, evaluating the impact of three key components on its performance: the number of perturbations per batch (K) for the forward-mode AD, the number of participating clients (C) per round, and the strategy of splitting trainable layers among clients. Subplots (a), (b), and (c) illustrate the effects of changing K, C, and the layer splitting strategy, respectively, showing performance differences across various datasets and language models. The results demonstrate the optimal values or strategies for each component to achieve maximum performance and efficiency with SPRY.

This figure presents ablation studies on three key aspects of the SPRY algorithm: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and the effect of splitting trainable layers across clients. Subfigure (a) shows the impact of varying K on the accuracy of SPRY, demonstrating that increasing the number of perturbations yields diminishing returns. Subfigure (b) illustrates how the performance changes as the number of participating clients is altered (C = 10, 50, 100), revealing that increasing client participation generally leads to improved accuracy. Finally, subfigure (c) directly compares the accuracy of SPRY against two variations where the layer splitting is not applied, showcasing the benefit of the splitting mechanism for both backpropagation-based methods and those relying on forward-mode AD.

This figure presents ablation studies on three key aspects of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch, the number of participating clients, and the impact of splitting trainable layers across clients. Subfigure (a) shows the effect of varying the number of perturbations on test accuracy, demonstrating that increasing perturbations beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns. Subfigure (b) illustrates the relationship between the number of participating clients and accuracy, revealing improved performance with a higher number of clients. Finally, subfigure (c) compares the performance of SPRY with two alternative approaches: one using backpropagation (FEDAVG) and another using the forward gradient without layer splitting. These results highlight the importance of SPRY’s design choices for optimal performance.

This figure presents ablation studies on SPRY’s performance concerning three key factors: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and whether the trainable weights are split across clients. Subfigure (a) shows the effect of changing the number of perturbations (K) in Forward-mode AD on test accuracy, demonstrating diminishing returns for K above 10. Subfigure (b) illustrates the influence of the client count (C) on test accuracy, revealing that increasing C enhances accuracy but requires fewer training rounds to converge to steady-state accuracy. Subfigure (c) compares the performance of SPRY with FEDAVG and FEDAVGSPLIT, a version of FEDAVG that uses the trainable weight splitting strategy. This comparison showcases SPRY’s superiority in achieving comparable accuracy to FEDAVG even with a smaller number of trainable parameters. It also compares SPRY to FEDFGD which runs backpropagation without layer splitting, highlighting the necessity of this strategy for faster convergence.

This figure presents ablation studies on three key aspects of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and the impact of splitting trainable layers. Subfigure (a) shows that increasing the number of perturbations beyond 10 provides minimal additional accuracy improvement, suggesting diminishing returns. Subfigure (b) demonstrates that increasing the number of participating clients improves accuracy, indicating a positive relationship between client participation and model performance. Subfigure (c) compares the performance of SPRY with FEDAVG and FEDAVGSPLIT (FEDAVG with the layer splitting strategy of SPRY) and FEDFGD (SPRY without the layer splitting strategy). FEDAVGSPLIT’s performance is significantly lower than FEDAVG’s, highlighting the importance of the layer splitting strategy for SPRY’s effectiveness.

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY, evaluating the influence of different hyperparameters on the model’s performance. Specifically, it investigates (a) the effect of varying the number of perturbations per batch (K) on the Forward-mode AD process; (b) the effect of modifying the number of participating clients (C) on the overall accuracy; and (c) a comparison of the performance of SPRY using its proposed layer splitting strategy against backpropagation-based methods (FEDAVG and FEDAVGSPLIT) and a baseline approach (FEDFGD). The results illustrate the impact of these hyperparameter choices on the model’s accuracy and convergence rate.

This figure presents ablation studies on three key aspects of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch, the number of participating clients, and the importance of splitting trainable layers. The results demonstrate the effect of these parameters on model accuracy and convergence speed. Specifically, it shows that increasing the number of perturbations beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns; increasing the number of participating clients improves accuracy; and that SPRY’s layer splitting strategy is crucial for its performance, as alternatives (without splitting or with splitting applied to backpropagation) perform significantly worse.

This figure presents the ablation study results on three aspects of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and the strategy of splitting layers for training. Subfigure (a) shows the effect of increasing K on the prediction accuracy. Subfigure (b) shows how changing the number of participating clients C affects the accuracy and convergence speed. Subfigure (c) compares SPRY with FEDAVG and FEDAVGSPLIT (which uses layer splitting in FEDAVG) and FEDFGD (which trains partial weights using Forward-mode AD without splitting across clients).

This figure shows the results of ablation studies on three hyperparameters of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients per round (C), and the strategy of splitting trainable weights of the model across clients. For each hyperparameter, multiple experiments were conducted to see its impact on the model’s performance. The results demonstrate that the optimal values for each hyperparameter depend on the task and dataset.

This figure presents ablation studies conducted on SPRY to evaluate the impact of various hyperparameters and design choices. Subfigure (a) shows how changing the number of perturbations per batch (K) affects the performance. Subfigure (b) demonstrates the effect of varying the number of participating clients (C) per round. Subfigure (c) compares the performance of SPRY (using the proposed weight-splitting and forward-mode AD) and its alternatives: FEDAVG (standard federated averaging), FEDAVGSPLIT (federated averaging with SPRY’s weight-splitting strategy applied), and FEDFGD (SPRY without the weight-splitting strategy). The results show the effectiveness of SPRY’s core components for achieving high accuracy and fast convergence.

This figure shows the architecture of SPRY, a federated learning framework for efficient finetuning of large language models. It illustrates the process of assigning trainable layers to different clients, computing gradients using forward-mode automatic differentiation, updating weights on the client side, and aggregating the updated weights on the server side to update the global model. The figure includes a legend explaining the symbols used to represent different data types (vectors, scalars, matrices). The figure also highlights that SPRY works with Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods.

This figure shows the results of ablation studies on three different hyperparameters of SPRY: the number of perturbations per batch (K), the number of participating clients (C), and whether the layer splitting strategy was used or not. The plots show that increasing K improves performance up to a certain point, after which additional gains diminish. Increasing the number of participating clients also improves accuracy. Finally, the results demonstrate that the layer splitting strategy is necessary for SPRY to achieve good performance, as removing this strategy leads to a significant reduction in accuracy.

More on tables

This table compares the communication costs (in terms of parameter count) of SPRY and its baseline methods. The costs are broken down by the communication frequency (per-epoch or per-iteration), and the direction of communication (from client to server or vice-versa). For each method, the table shows the communication cost for a single client and the total communication cost across all clients.

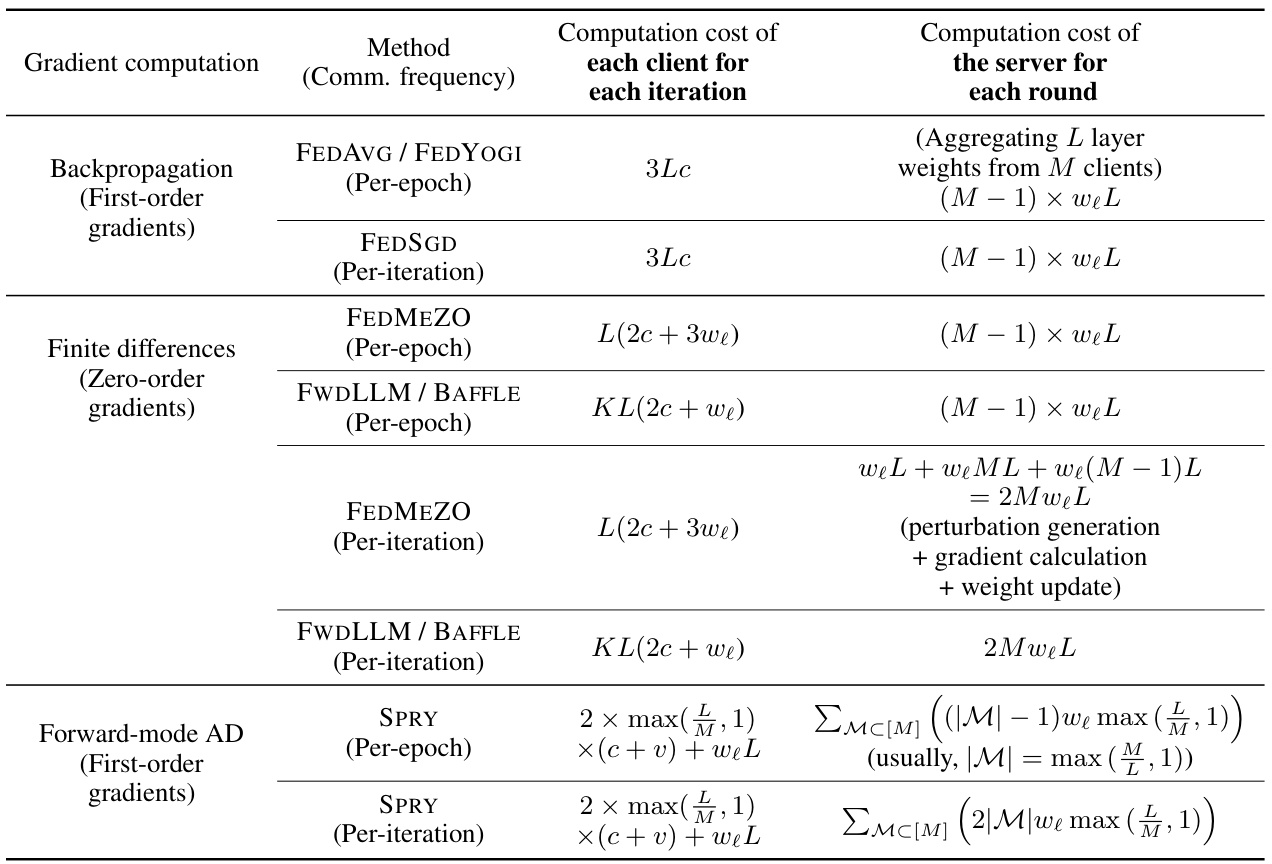

This table compares the computation costs of SPRY against other baselines (backpropagation-based and zero-order methods). It breaks down the costs into client-side (per iteration) and server-side (per round) computations. The computation cost is analyzed based on the number of layers (L), the number of participating clients (M), the cost of matrix multiplication (c), the overhead of column-by-column vector multiplication in jvp (v), the size of each layer (we), and the number of perturbations per iteration (K).

This table presents a comparison of the generalized accuracy achieved by SPRY against backpropagation and zero-order methods across various datasets and language models. It highlights that SPRY significantly outperforms zero-order methods and performs comparably to backpropagation, often with only a small accuracy difference.

This table presents a comparison of the generalized accuracy achieved by SPRY against backpropagation-based and zero-order-based methods on various datasets and language models. It highlights SPRY’s superior accuracy compared to zero-order methods and its near-parity performance with backpropagation, showcasing its effectiveness in federated learning.

This table presents a comparison of the generalized accuracy achieved by SPRY against backpropagation-based and zero-order-based methods across various datasets and language models. It highlights SPRY’s superior performance compared to zero-order methods and its near-parity with backpropagation methods in terms of accuracy. The table also indicates the specific language models and datasets used in the experiments, and notes that the F1 score is used for the SQUADv2 dataset.

This table compares the generalized accuracy of SPRY against other backpropagation-based and zero-order-based methods. The datasets used are AG News, SST2, SNLI, MNLI, Yahoo, Yelp, MultiRC, and SQUADv2. The language models used are ROBERTa Large, Llama2-7B, OPT6.7B, and OPT13B. The table shows that SPRY outperforms zero-order methods significantly and gets close to the accuracy of backpropagation methods, demonstrating its effectiveness and efficiency.

Full paper#