↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Hardware model checking, verifying if a system’s every execution meets its specification, is computationally expensive, especially for complex systems. Traditional methods like BDDs and SAT solvers struggle with large state spaces, often requiring extensive computation time, and sometimes failing to complete verification within reasonable timeframes. This makes ensuring correctness assurance particularly challenging for critical systems where bugs can be costly or dangerous.

This research proposes a novel machine learning approach that leverages neural networks to generate proof certificates for the correctness of a system design. The method trains neural networks on random executions of the system, using them to represent proof certificates. It then symbolically checks the validity of these certificates, proving that the system satisfies a given temporal logic specification. This approach is entirely unsupervised, formally sound, and demonstrably more efficient than existing methods, achieving significant performance improvements on standard hardware designs written in SystemVerilog.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in formal verification and machine learning. It bridges the gap between these two fields by introducing a novel approach to model checking using neural networks. This opens up new avenues for research into more efficient and scalable verification techniques, particularly for complex hardware systems. The results demonstrate the potential for machine learning to revolutionize traditional formal verification methods, offering significant advantages in terms of speed and scalability. This work is particularly timely given the growing complexity of modern hardware and software systems, where traditional techniques often struggle to keep pace.

Visual Insights#

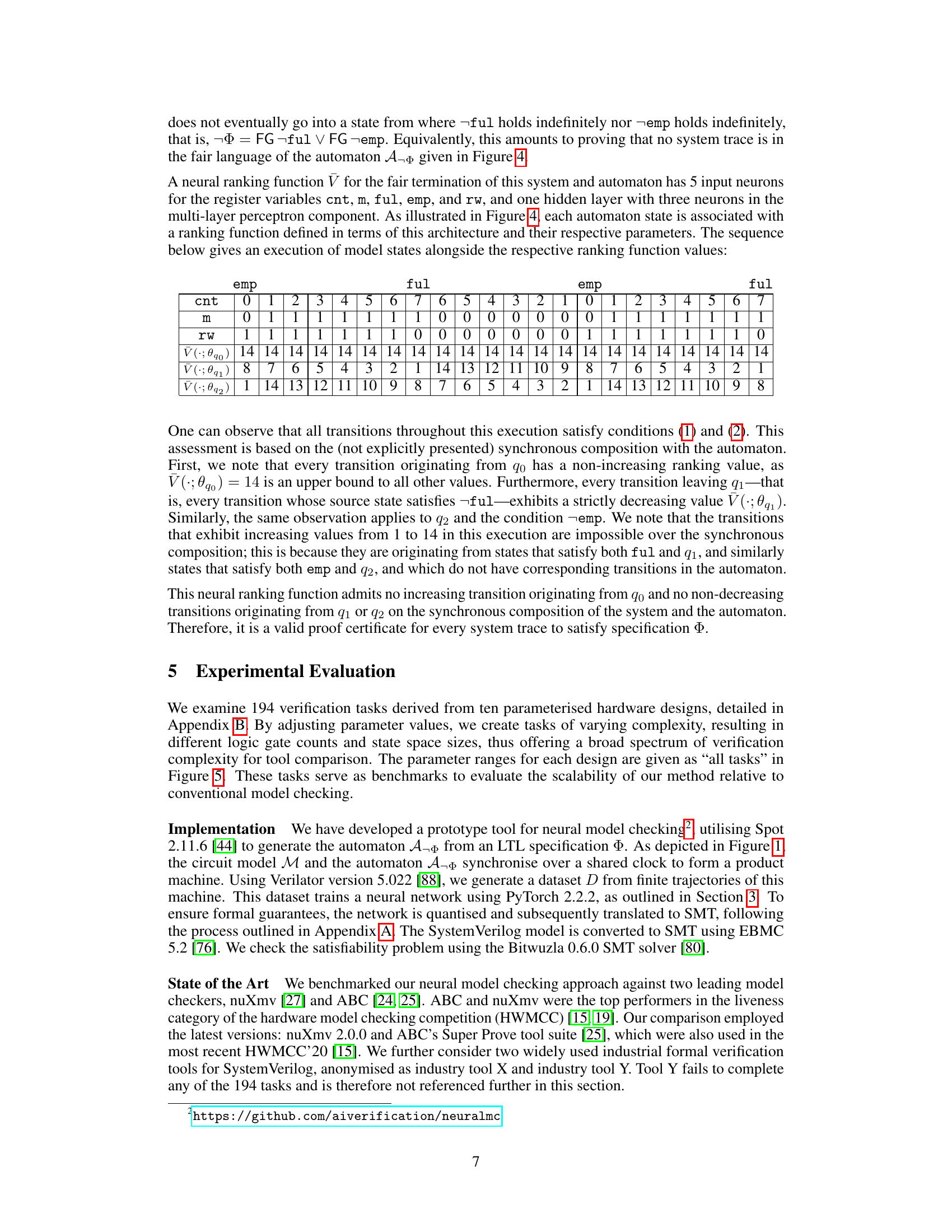

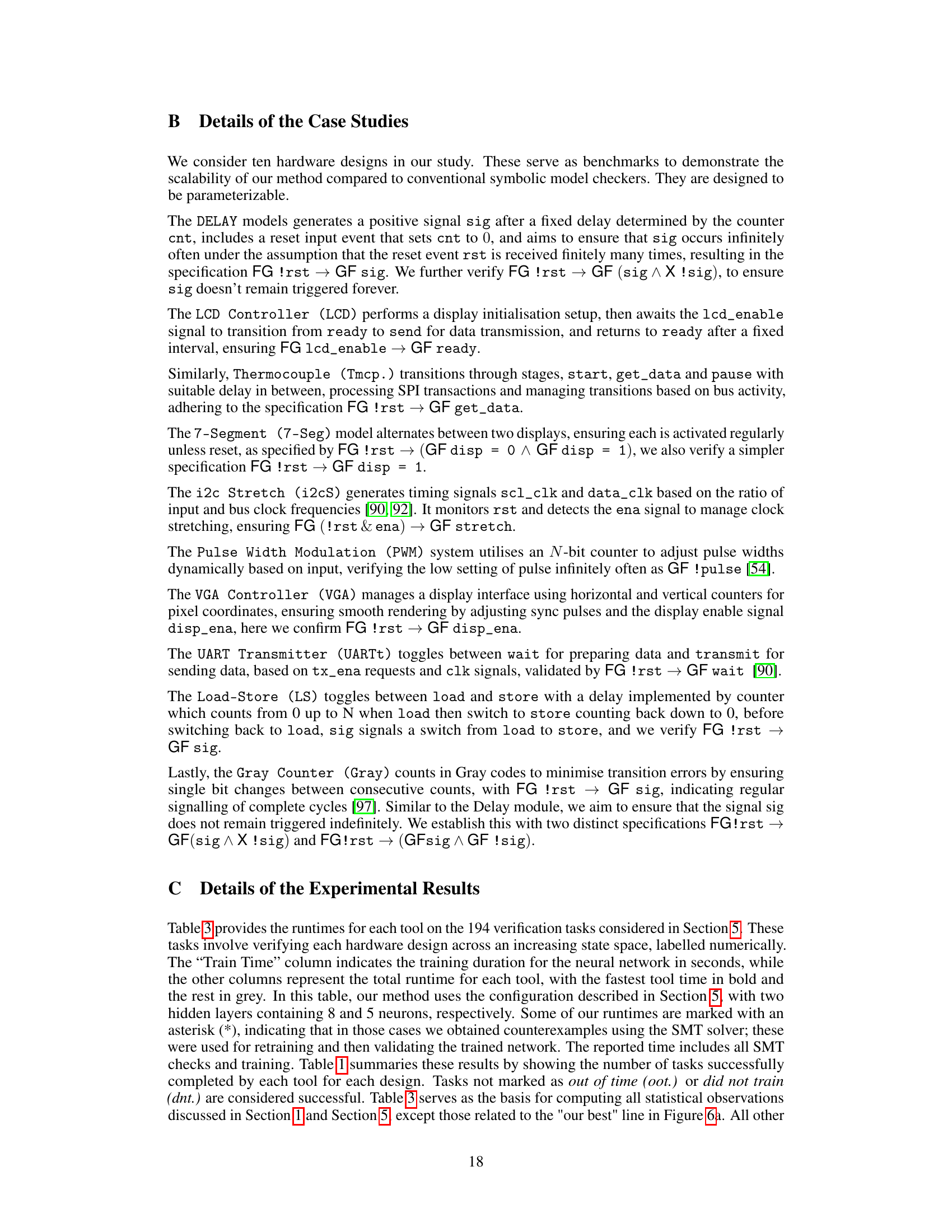

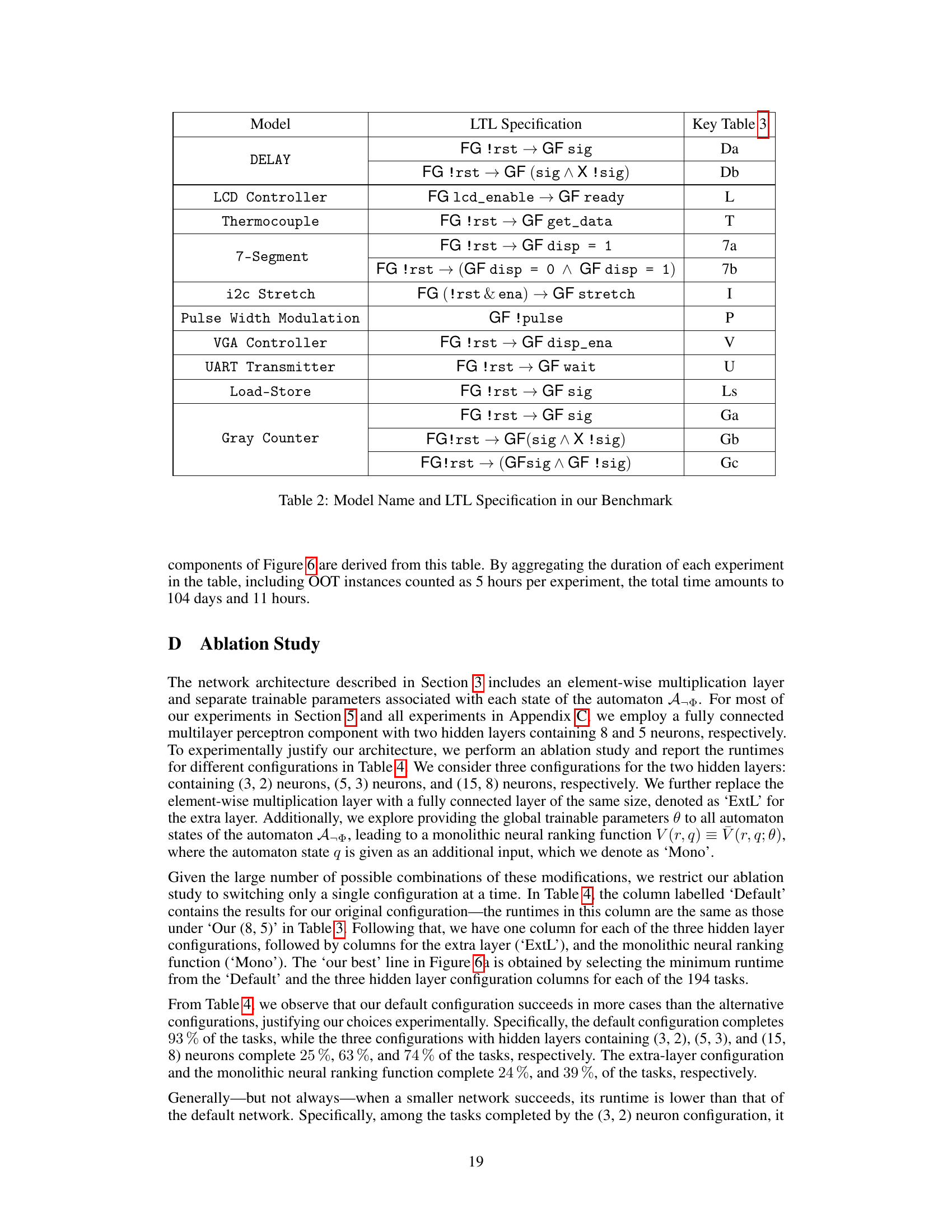

This figure illustrates the automata-theoretic approach to neural model checking. Panel (a) shows a block diagram of the system. The hardware model M and Büchi automaton A¬Φ operate synchronously. The outputs of M (obs XM) are fed as inputs to A¬Φ, which produces a state q. These, along with register values (reg XM), are used as input to a neural network V with trainable parameters θq for each state. Panel (b) shows a trace, visualizing the ranking function V and indicator function 1F(q). The ranking function decreases strictly at every transition from a fair state, demonstrating fair termination and proving that the system satisfies the specification.

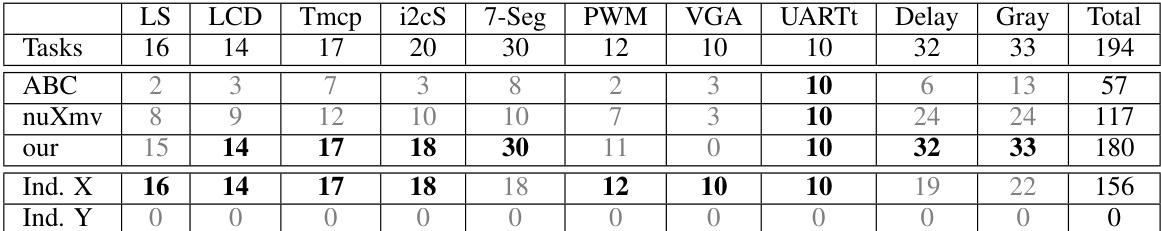

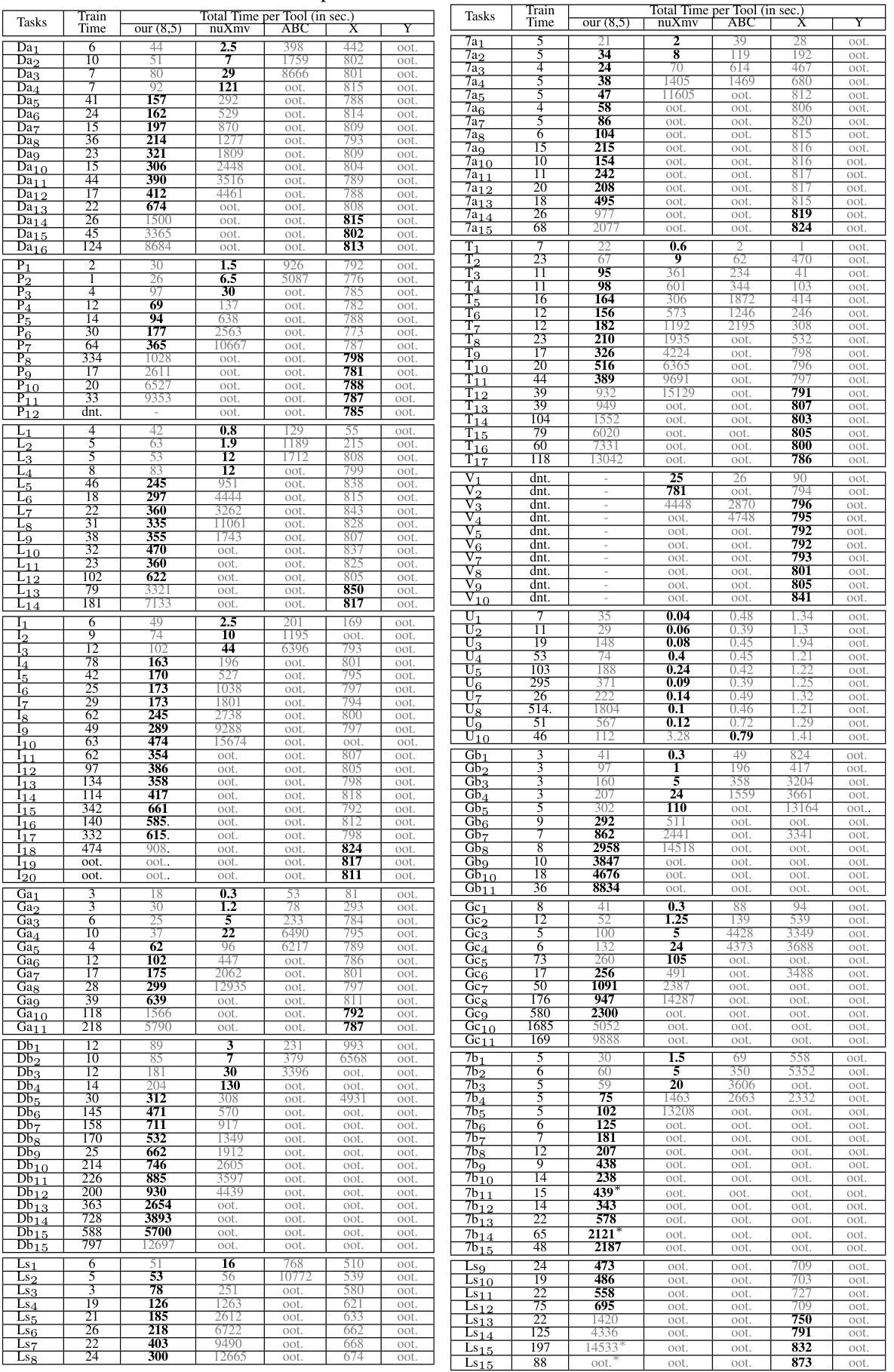

This table presents a detailed comparison of the runtime performance of the proposed neural model checking method against three state-of-the-art model checkers (ABC, nuXmv, and Industry Tool X) across 194 verification tasks. The tasks are categorized by hardware design and include the training time for the neural network, as well as the total time taken by each tool to complete each verification task. The table highlights the effectiveness of the proposed method, showing that it outperforms other tools, especially in terms of the time it takes to successfully complete verification tasks.

In-depth insights#

Neural Verification#

Neural verification represents a paradigm shift in formal verification, leveraging the power of neural networks to address challenges in traditional methods. It offers the potential for significantly improved scalability and efficiency, particularly for complex systems where traditional techniques struggle. By training neural networks as proof certificates, this approach aims to reduce the computational burden associated with exhaustive state space exploration. However, challenges remain, notably ensuring the formal soundness and reliability of neural network-based proofs, particularly over unbounded time horizons. The trustworthiness of neural verification hinges on the rigorous validation of the generated certificates, likely requiring sophisticated techniques like symbolic reasoning or SMT solving to complement the learning process. Addressing issues of generalization and robustness will be critical to expanding the scope of neural verification to real-world applications. The potential for this field is enormous given the ability to potentially verify systems far beyond what’s possible using classical methods.

SMT-based Checking#

SMT-based checking, in the context of hardware or software verification, involves using Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solvers to determine the validity of a given property. SMT solvers are powerful tools capable of handling complex logical formulas and diverse data types, unlike simpler Boolean satisfiability (SAT) solvers. This allows for a more precise and expressive analysis of systems, particularly those involving intricate arithmetic or bit-vector operations frequently found in hardware designs. The process typically involves translating the system model and the property to be verified into an SMT formula, and then using the solver to check for satisfiability. If the formula is unsatisfiable, it confirms that the property holds; otherwise, a counterexample may be generated, providing valuable insights for debugging or refinement. A key advantage is its ability to reason about unbounded time and space, unlike bounded model checking techniques. However, the computational cost of SMT-based checking can be significant, depending on the complexity of the model and the property. This makes efficient encoding and the choice of SMT solver crucial for scalability and performance. Furthermore, the translation process itself requires careful attention to detail to avoid inaccuracies and maintain the integrity of the verification process.

Ranking Function#

The concept of a ranking function is central to the paper’s approach to model checking, offering a novel way to prove the absence of counterexamples. Instead of directly exploring the potentially vast state space, the method trains a neural network to act as a ranking function. This function assigns a numerical value to each state of a combined system and Büchi automaton, designed to strictly decrease along any path leading to an accepting state of the automaton, while remaining non-increasing otherwise. The existence of such a function guarantees that no fair execution (infinitely often visiting accepting states) exists, thus proving the correctness of the system. The use of neural networks offers scalability advantages over traditional symbolic techniques, as checking the validity of the neural certificate is computationally simpler than finding it. However, ensuring the global correctness of the learned ranking function is crucial and requires symbolic verification using SMT solvers. This combination of machine learning and formal verification is a key innovation, offering potential improvements in efficiency and scalability for hardware model checking.

Hardware Designs#

The paper focuses on a novel machine learning approach to model checking, applied to hardware verification. The choice of hardware designs is crucial for evaluating this method’s effectiveness, and the authors mention using ten parameterizable designs to generate a variety of verification tasks. These designs likely encompass different levels of complexity and state-space sizes. The parameterization is key, allowing the generation of numerous instances with varying difficulty, thus creating a comprehensive benchmark set. The selection of designs should represent a realistic range of hardware, avoiding overly simplistic or unrealistic scenarios while incorporating features that challenge model checkers. The designs should ideally highlight common hardware patterns such as counters, state machines, arithmetic circuits, and memory modules, but the specific choices are not explicitly described in the provided text snippet, leaving some ambiguity regarding the specific challenges addressed.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of this research paper, the ablation study likely investigates the impact of various architectural choices on the neural ranking function’s performance. This might involve experimenting with different numbers of hidden layers, the number of neurons per layer, and the presence or absence of specific layers such as element-wise multiplication layers, or changing to a monolithic structure. By removing components one at a time, the researchers can isolate their effects on the model’s ability to learn a ranking function that satisfies the formal criteria for fair termination and overall runtime performance. The results would reveal which architectural elements are most crucial and whether simpler, faster architectures are sufficient or whether more complex designs offer significant performance improvements. Key insights from this study would guide design choices towards more efficient and effective neural ranking functions while maintaining formal correctness. This study’s impact extends to improving the scalability and robustness of the neural model checking approach, making it more practical for real-world applications.

More visual insights#

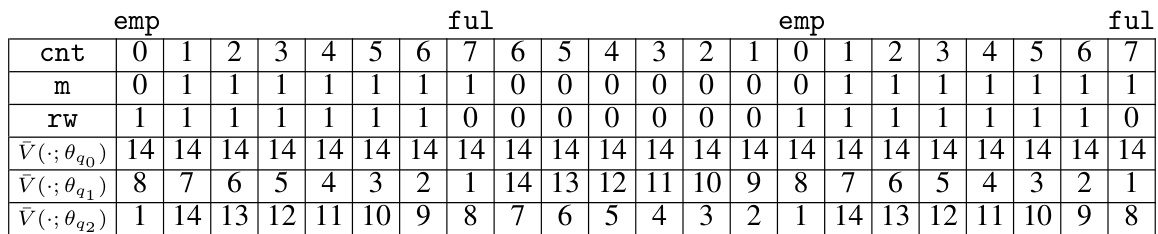

More on figures

The figure shows the architecture of the neural ranking function used in the paper. It’s a feed-forward network consisting of a normalization layer, an element-wise multiplication layer, and a multi-layer perceptron with clamped ReLU activation functions. The normalization layer scales the input values. The element-wise multiplication layer applies a trainable scaling factor to each neuron. The multi-layer perceptron has trainable weights and biases. The clamp operation restricts the output values to a specific range. The architecture is designed to efficiently represent a ranking function for fair termination.

This figure illustrates the automata-theoretic approach to neural model checking. Panel (a) shows a synchronous composition of the hardware model (M) and the Büchi automaton (A¬Φ) for the negation of the LTL specification (¬Φ). The output of the model (obs XM) serves as the input for the automaton. The automaton identifies counterexamples to the specification. Panel (b) illustrates the concept of fair termination using a ranking function. A ranking function V assigns a value to each state of the composition M || A¬Φ. For a fair execution, the ranking function must strictly decrease each time a transition from a fair state is taken, ensuring that no fair executions exist.

This figure shows the number of tasks successfully solved by different model checkers (ABC, nuXmv, Industry tool X, and the proposed neural method) plotted against the state space size and logic gate count. The log scale highlights the differences in scalability of the various methods. The proposed neural method shows significantly better performance than the others across a wide range of sizes and complexities.

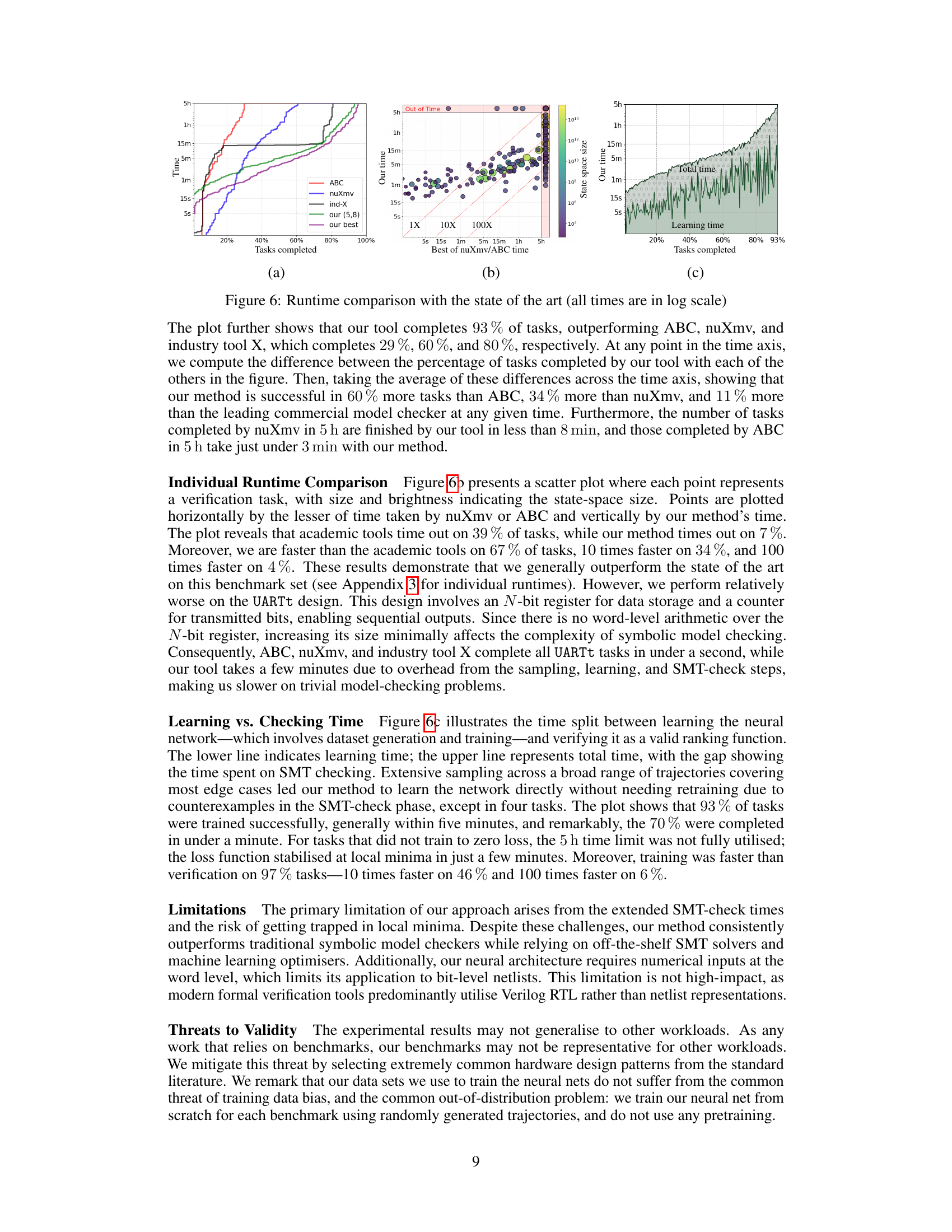

This figure presents a comprehensive runtime comparison between the proposed neural model checking method and state-of-the-art tools (ABC, nuXmv, and Industry tool X). Subfigure (a) shows a cactus plot illustrating the cumulative number of tasks completed by each tool within a given time limit (5 hours). Subfigure (b) presents a scatter plot showing the individual runtime of each tool for each task. The size and brightness of the points represent the state space size. The plot indicates how often the proposed method is faster than the others. Subfigure (c) depicts the learning and checking times for the proposed approach, highlighting the efficiency of the neural network training process.

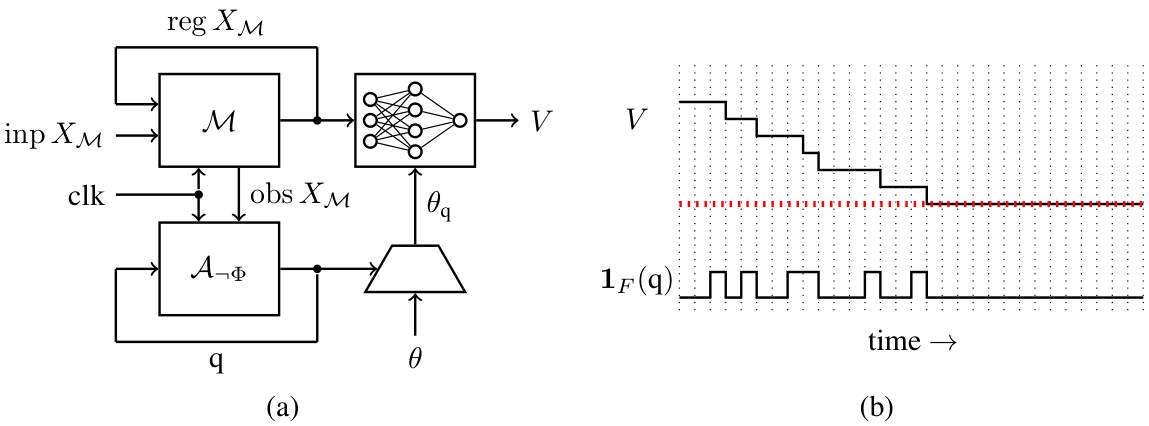

More on tables

This table presents the number of verification tasks successfully completed by four different model checkers (ABC, nuXmv, the authors’ method, and an unnamed industrial tool) across ten different hardware designs. Each design is further broken down into multiple tasks of varying complexity. The table allows a comparison of the performance of different model checking approaches on a wide range of verification problems.

This table details the runtime comparison of the proposed neural model checking method against existing state-of-the-art academic and commercial model checkers on 194 individual verification tasks. For each task, it lists the training time for the neural network and the total runtime for each tool, highlighting the fastest time. The table also indicates instances where tools timed out or failed to train. This comprehensive comparison demonstrates the proposed method’s performance relative to the existing tools across various benchmarks and complexities.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the runtime performance of the proposed neural model checking method against existing state-of-the-art methods (nuXmv, ABC, and Industry Tool X) across 194 verification tasks. For each task, the table shows the training time for the neural network, and the total runtime for each tool. The results are presented in seconds, with ‘oot.’ indicating that a tool timed out, and ‘dnt.’ indicating that the tool did not complete the task. This provides granular information to understand the performance differences across tasks of varying complexity.

This table presents a detailed comparison of the runtime performance of the proposed neural model checking method against state-of-the-art academic and commercial model checkers on 194 verification tasks. For each task, the table shows the training time for the neural network, along with the total runtime for each tool. The fastest runtime is highlighted in bold, and the table includes additional information about tasks that did not complete within the time limit or encountered issues during training. This comprehensive comparison allows for a thorough evaluation of the proposed method’s efficiency and scalability.

Full paper#