↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many scientific machine learning models are trained on a single physical system, leading to limited generalizability to other systems. Acquiring sufficient data for training models on multiple systems can be costly and time-consuming. This paper proposes a new approach called Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) to address this limitation.

MPP trains a single transformer model to predict the dynamics of multiple heterogeneous physical systems simultaneously. This allows the model to learn features that are broadly applicable across systems and improve its transferability to new, unseen systems. The results demonstrate that MPP-trained models match or surpass task-specific baselines without finetuning, and achieve better accuracy on systems with previously unseen components or higher dimensions compared to training from scratch.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computational physics and machine learning. It introduces Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP), a novel approach that significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of building surrogate models for diverse physical systems. The open-sourced code and model weights promote reproducibility and accelerate future research in this rapidly evolving field. Transfer learning capabilities demonstrated by the MPP approach are especially valuable for low-data regimes, where traditional methods struggle. This opens new avenues for exploring diverse and complex physical phenomena.

Visual Insights#

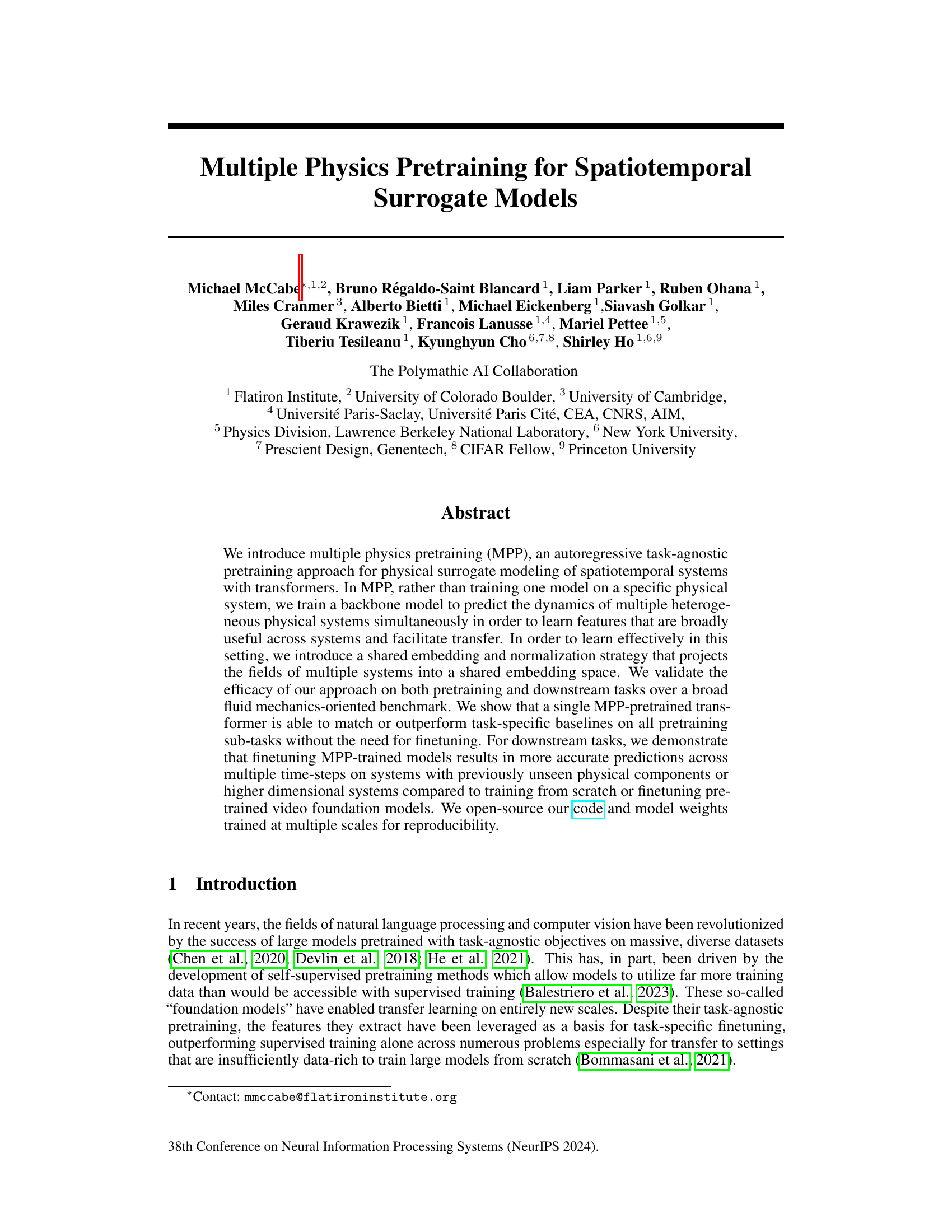

The figure shows a comparison of the test root mean square error (RMSE) for models trained from scratch, models pretrained on advection and diffusion data and then finetuned on advection-diffusion data, and models trained only on advection-diffusion data. It demonstrates that pretraining on advection and diffusion improves the accuracy of models trained on advection-diffusion, even when the amount of training data is limited. This supports the hypothesis that learning partially overlapping physics is beneficial for transfer learning.

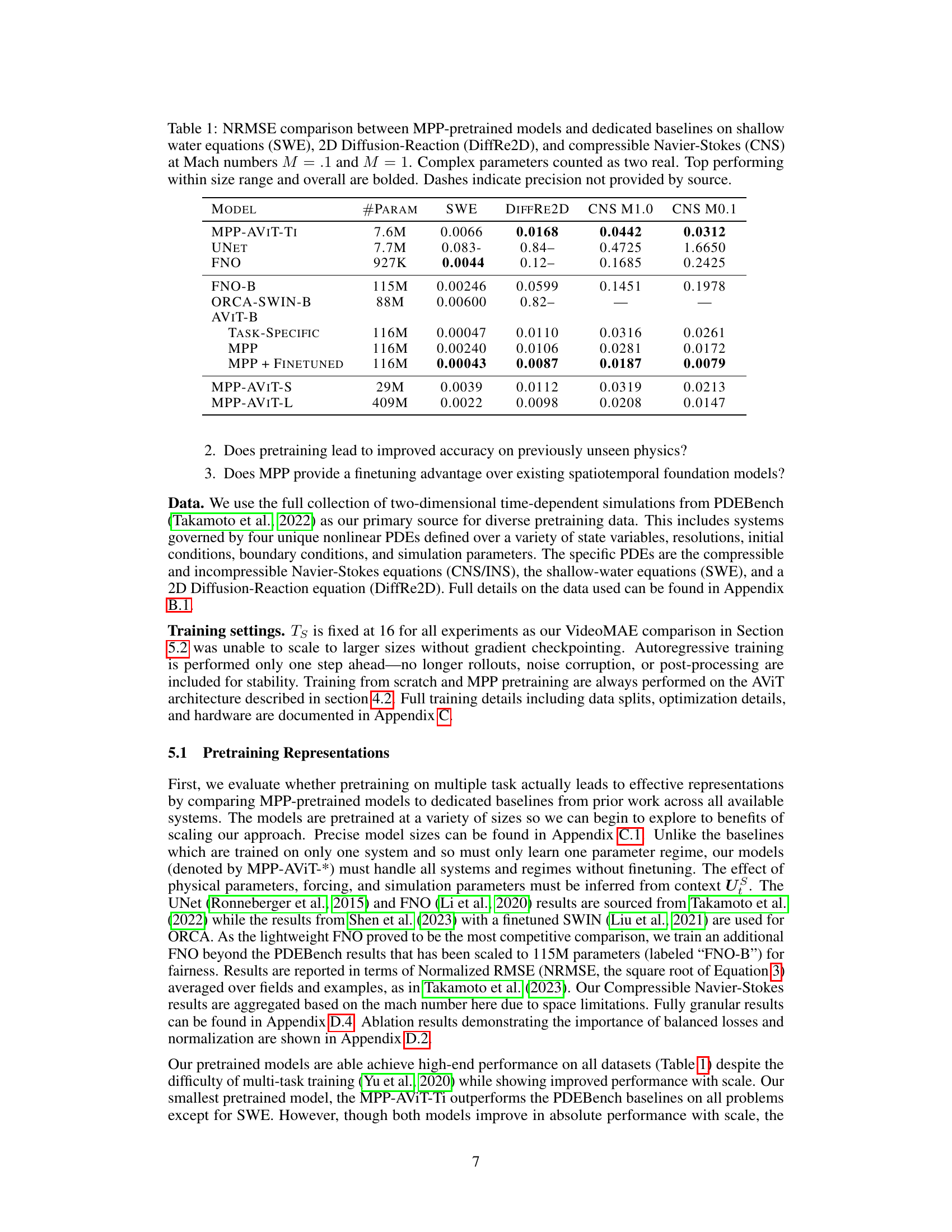

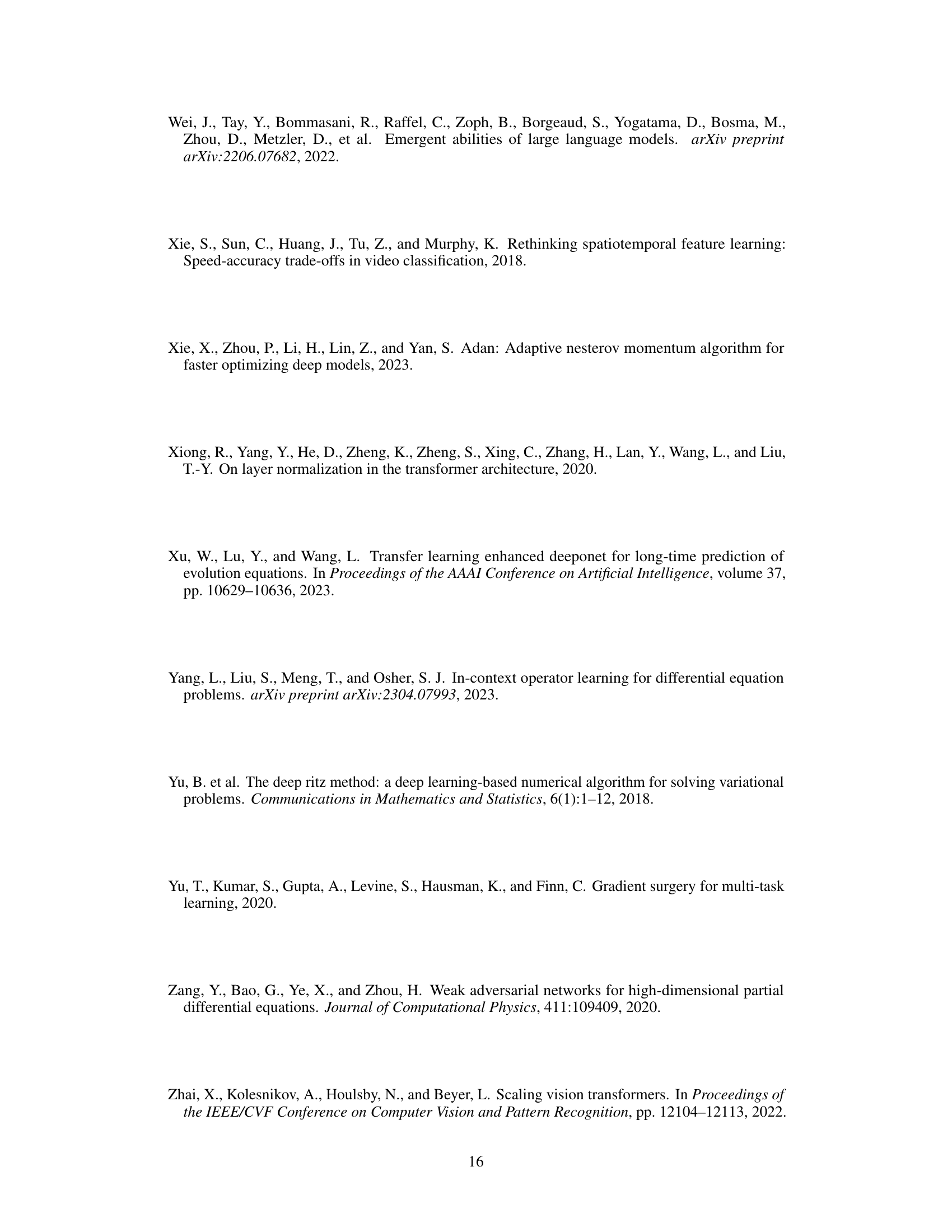

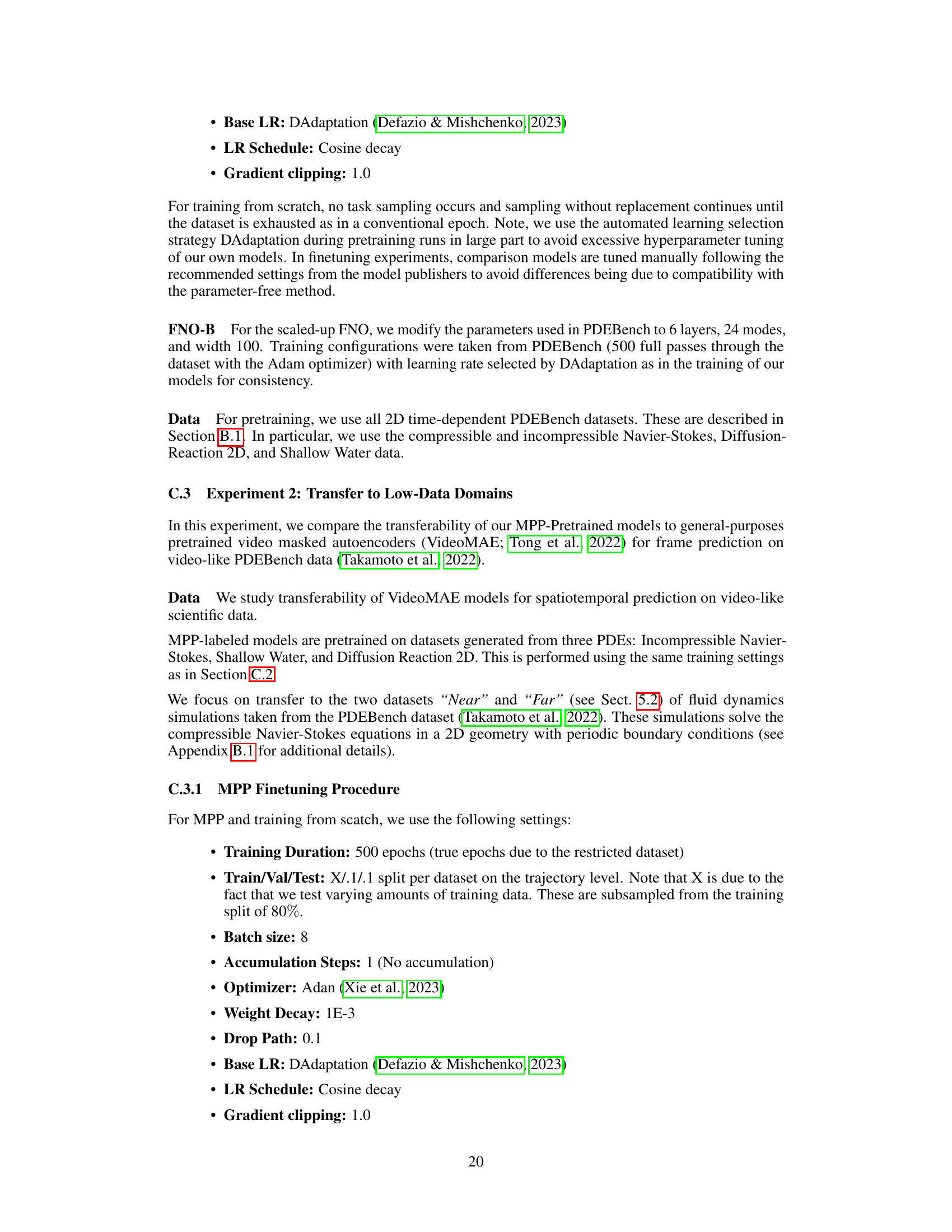

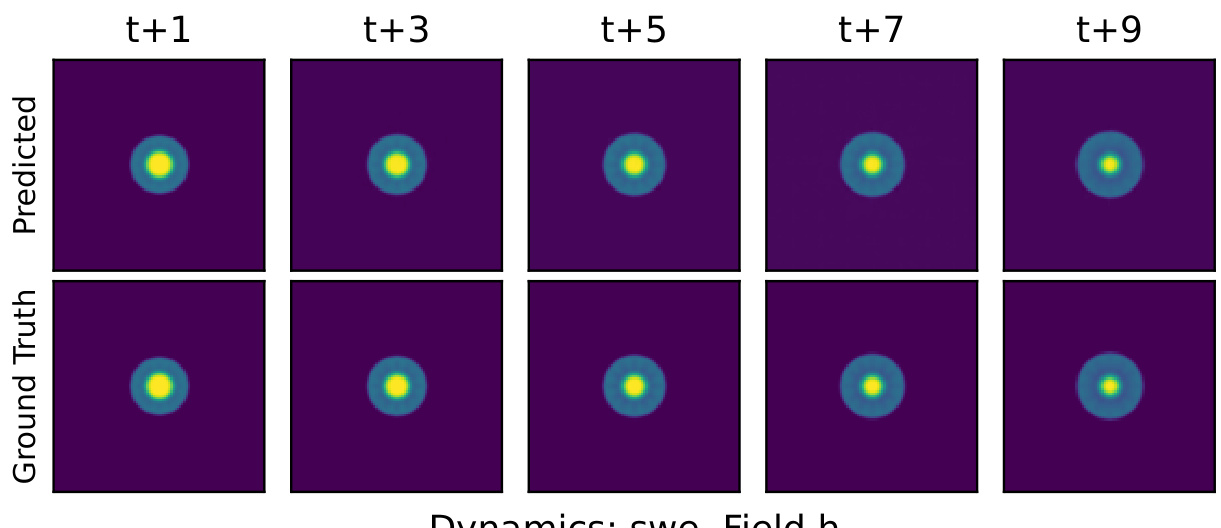

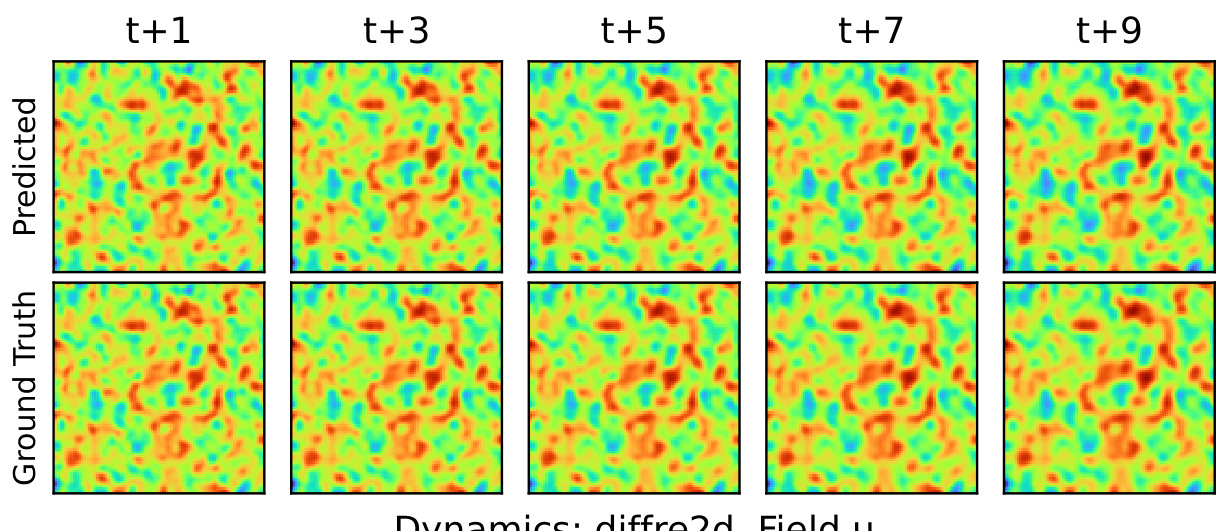

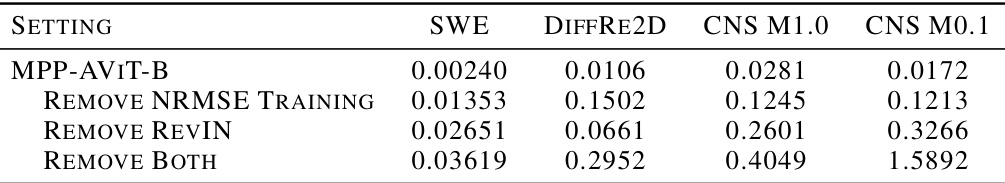

This table compares the normalized root mean squared error (NRMSE) of different models on three different partial differential equation (PDE) datasets: shallow water equations (SWE), 2D diffusion-reaction (DiffRe2D), and compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS). The models are compared at two different Mach numbers (M=0.1 and M=1.0). The table includes both models pretrained using the multiple physics pretraining (MPP) method and task-specific baselines. The best performing models within each size range, and overall, are highlighted in bold. Missing values are indicated by dashes.

In-depth insights#

MPP: Physics Pretraining#

Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) is a novel approach to enhance the capabilities of surrogate models in representing spatiotemporal physical systems. The core idea is to pretrain a single model on diverse, heterogeneous physical systems simultaneously, rather than specializing on a single system. This shared learning approach leverages common underlying principles across physics, such as diffusion or advection, to learn broadly applicable features. MPP significantly improves transfer learning, enabling models to effectively predict the dynamics of systems with previously unseen physical components or higher dimensions with limited training data. A key innovation is the shared embedding and normalization strategy, which projects fields from various systems into a common space, facilitating effective learning despite scale and resolution differences. This allows MPP-trained models to outperform task-specific baselines and existing video foundation models in low-data regimes, demonstrating the effectiveness of this task-agnostic pretraining strategy.

Axial Attention Design#

Axial attention mechanisms offer a compelling approach to handling the computational cost associated with traditional self-attention in high-dimensional data such as images or videos. Standard self-attention scales quadratically with sequence length, making it impractical for large inputs. Axial attention mitigates this by decomposing the attention computation into multiple 1D operations along each axis (e.g., spatial height and width independently). This reduces the complexity to linear scaling, thereby enabling the processing of significantly larger inputs. However, this simplification comes at a potential cost to expressiveness, as the independent axis-wise attention may not fully capture the intricate interactions between different dimensions. The choice between standard self-attention and axial attention often involves a trade-off between computational efficiency and model capacity. The effectiveness of axial attention depends greatly on the nature of the data; it may be highly effective for data where the primary relationships exist along individual axes, while falling short for data requiring strong cross-axis interactions. Further research should focus on improving the efficiency of axial attention and exploring hybrid methods that combine the strengths of both standard and axial approaches to enhance expressiveness without sacrificing efficiency.

Transfer Learning Tests#

A hypothetical ‘Transfer Learning Tests’ section would explore how a model, pretrained on diverse physics simulations, generalizes to new, unseen systems. It would likely involve testing the model’s performance on tasks representing different physical phenomena and comparing its accuracy against models trained specifically for those tasks. Key metrics would include prediction accuracy (e.g., NRMSE) across various time steps and systems with different characteristics. The experiments might involve low-data regimes, where the model is fine-tuned using limited data, to assess transferability and evaluate if the pretrained model requires less data for comparable performance. Comparisons to standard transfer learning benchmarks such as training from scratch or using pre-trained video models would help showcase the effectiveness of the multiple physics pretraining approach. Analysis of the model’s ability to extrapolate to higher-dimensional systems or those with unseen components would be crucial to understand its ability to generalize beyond the training distribution. The results would provide strong evidence for the model’s capacity to acquire a generalized understanding of physics, supporting the paper’s claims about task-agnostic learning and its potential for accelerating scientific discovery.

3D Model Inflation#

3D model inflation, in the context of this research paper, presents a fascinating approach to scaling up 2D models to 3D. The core idea leverages the model’s inherent structure and its ability to independently process each spatial dimension. This enables the efficient extension of the model to handle an additional dimension, essentially inflating a 2D model into a 3D one. The process is computationally efficient, making it a practical choice, particularly given the expense of training large 3D models directly. However, careful attention must be given to initialization, as simply duplicating the 2D model across the new dimension may not capture the increased complexity inherent in 3D systems. Success hinges on effective handling of the interaction between dimensions, and the choice of an appropriate inflation method becomes crucial. Although this approach is shown to improve upon training from scratch, the paper highlights that this isn’t a direct replacement for training native 3D models. The results demonstrate that this technique can provide improved performance on higher dimensional systems, but further research into improved initialization techniques is needed to fully unlock its potential. The strategy is well-suited for certain architectures. Ultimately, the success of 3D model inflation highlights an important trend towards more efficient model scaling in scientific machine learning.

Future Work and Limits#

The research paper’s “Future Work and Limits” section would ideally delve into several crucial aspects. Extending the model’s capabilities to non-uniform geometries and 3D systems is paramount, as many real-world physical phenomena exhibit such complexities. Addressing the challenge of handling incomplete or noisy data is essential for practical applications, requiring robust methods to manage uncertainty. A deeper investigation into the limits of transfer learning is needed; understanding how far the model’s performance generalizes beyond its training data is key. Incorporating constraints and conservation laws explicitly within the model framework could improve accuracy and physical realism. The study also needs to explore different architectures, evaluating the trade-offs between performance and computational efficiency, with an examination of scalability and generalizability across various physics systems. Finally, the impact of data diversity on model performance requires a thorough investigation, as the availability and quality of data strongly influence the outcome.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) approach. It shows a comparison of three different training methods: training from scratch, training with a pretrained model that only saw advection and diffusion data separately, and a zero-shot approach using the MPP pretrained model. The y-axis represents the test root mean squared error (RMSE), and the x-axis shows the number of training samples used. The results clearly indicate that the MPP pretrained model significantly outperforms the other methods, especially when the number of training samples is limited. Even with limited data, the MPP-pretrained model performs comparably to models trained with much larger datasets.

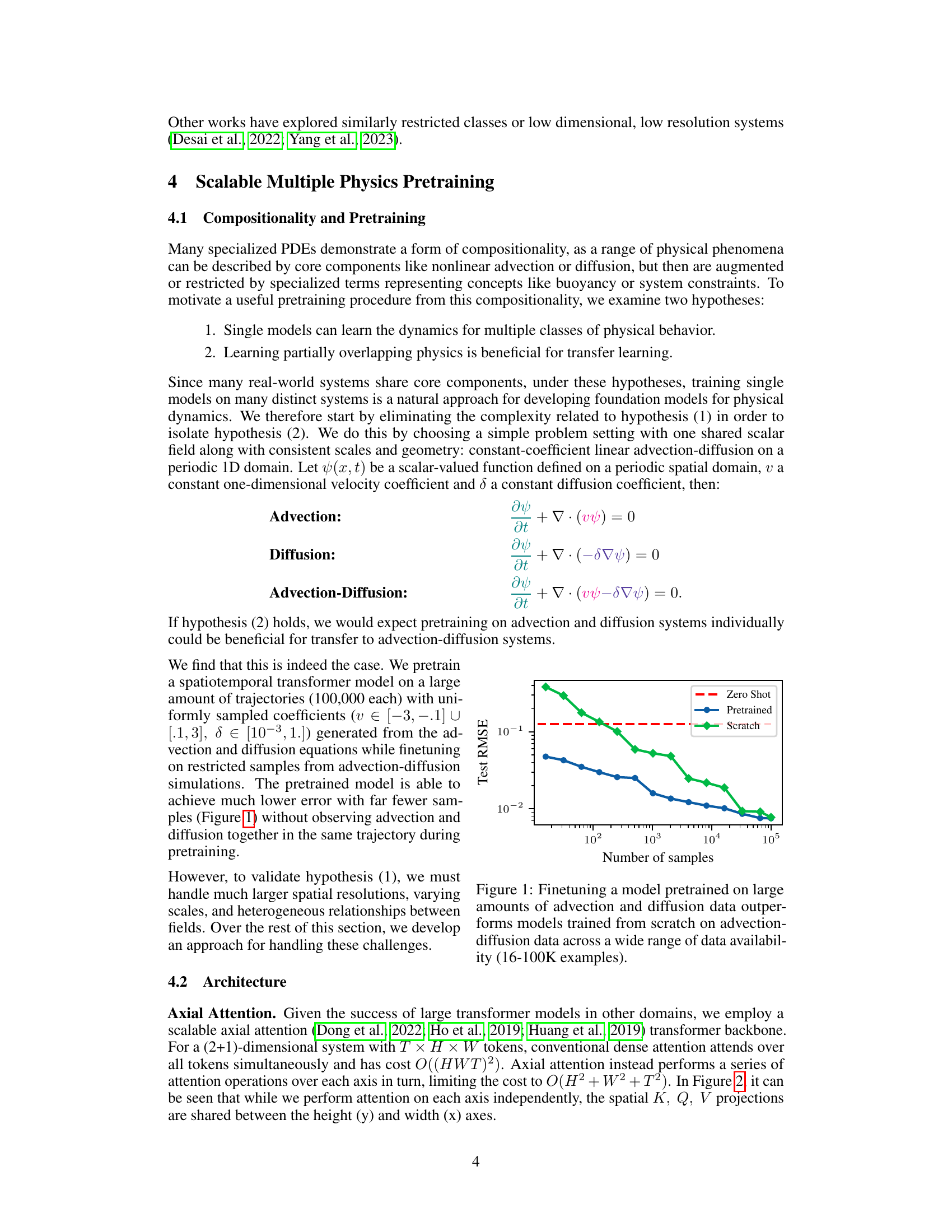

This figure illustrates the Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) architecture. The left side shows the data processing pipeline: individual fields from multiple physical systems are normalized using Reversible Instance Normalization (RevIN), embedded into a shared space, and processed by a spatiotemporal transformer (Axial ViT). The transformer predicts the next time step for all systems simultaneously. The right side details the field embedding process: each field is projected into a shared embedding space using a 1x1 convolutional filter. The weights of this filter are shared across systems, allowing the model to learn generalizable features.

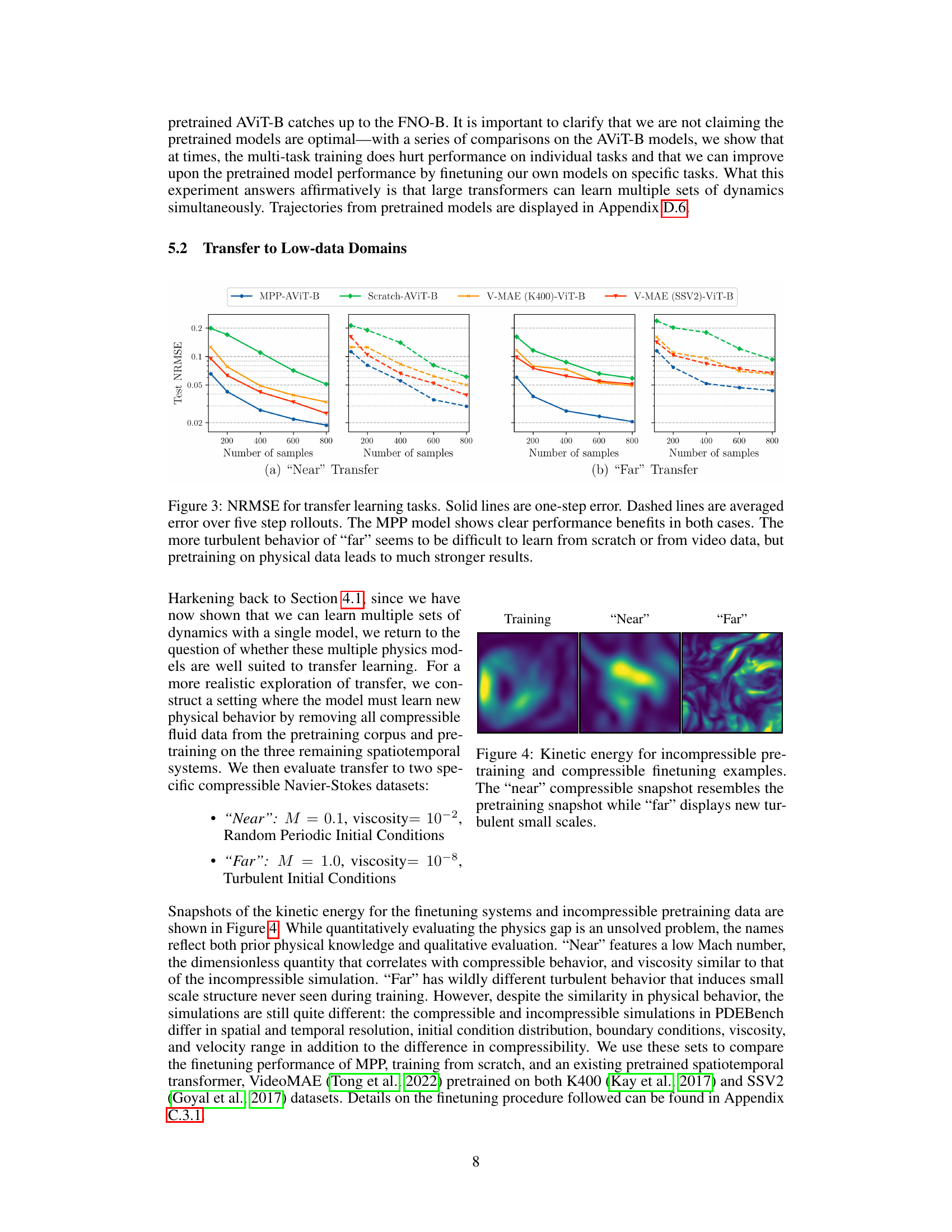

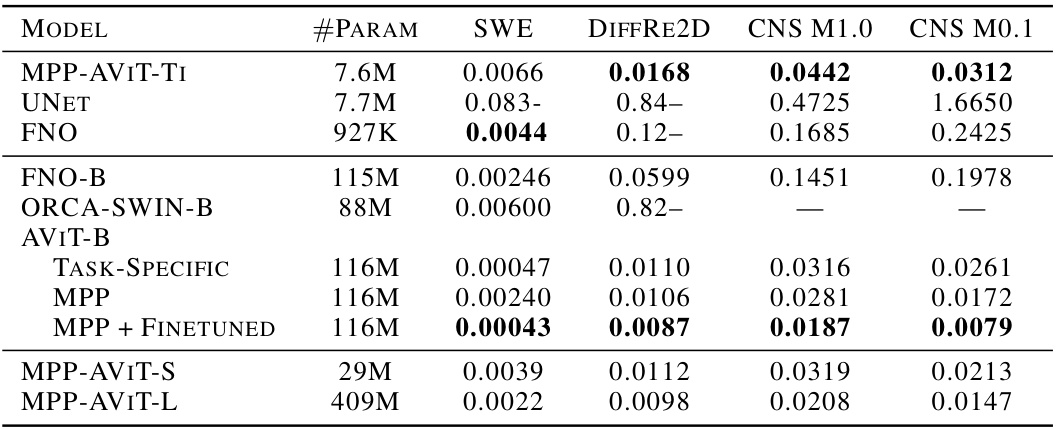

The figure displays the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) for two transfer learning tasks, ‘Near’ and ‘Far’, comparing the performance of MPP-trained models, models trained from scratch, and VideoMAE models pretrained on two different video datasets (K400 and SSV2). Both one-step error and error averaged over five steps are shown. The results indicate that MPP pretraining significantly improves prediction accuracy, especially for the more complex ‘Far’ task, even with limited training data. The results demonstrate the beneficial effect of MPP in transferring knowledge to new physical systems.

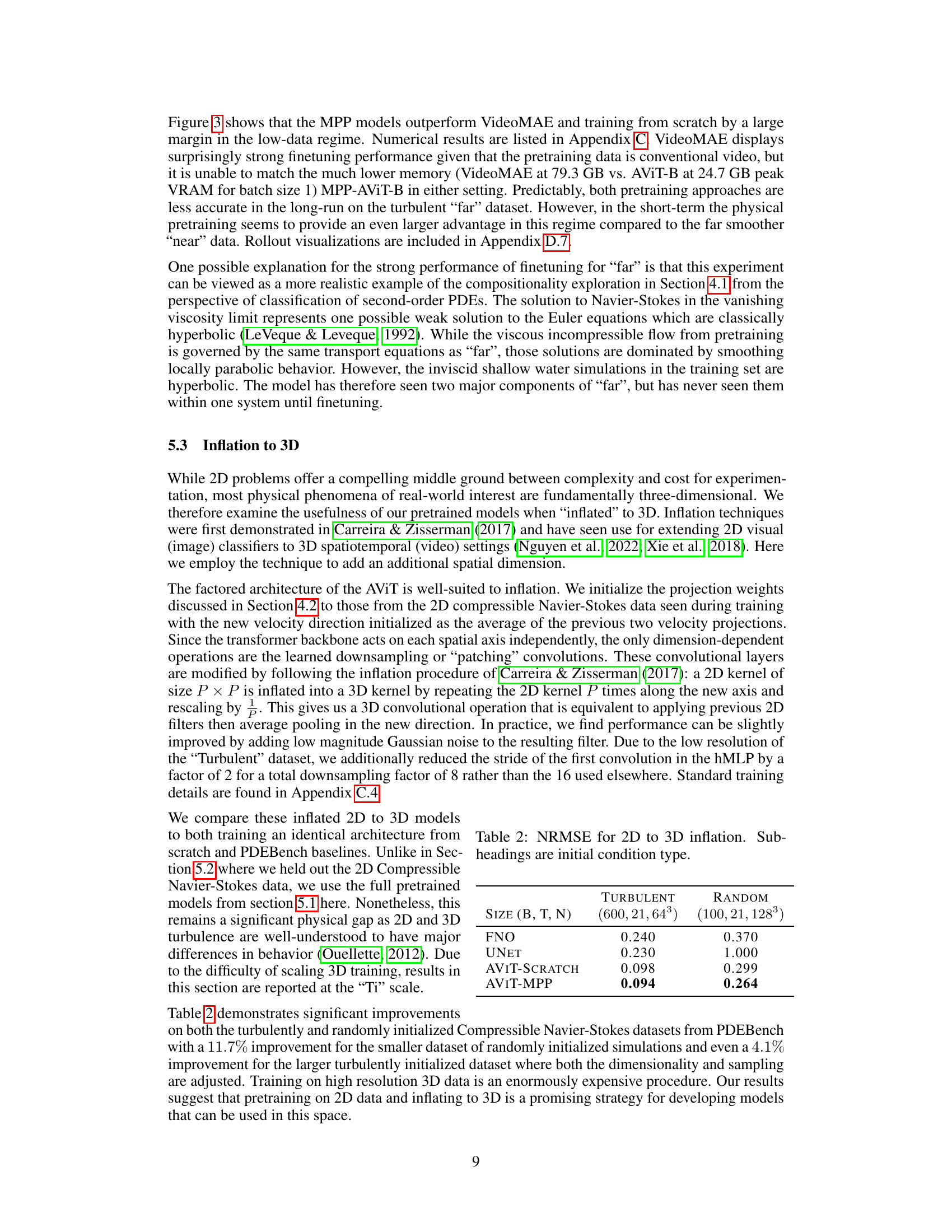

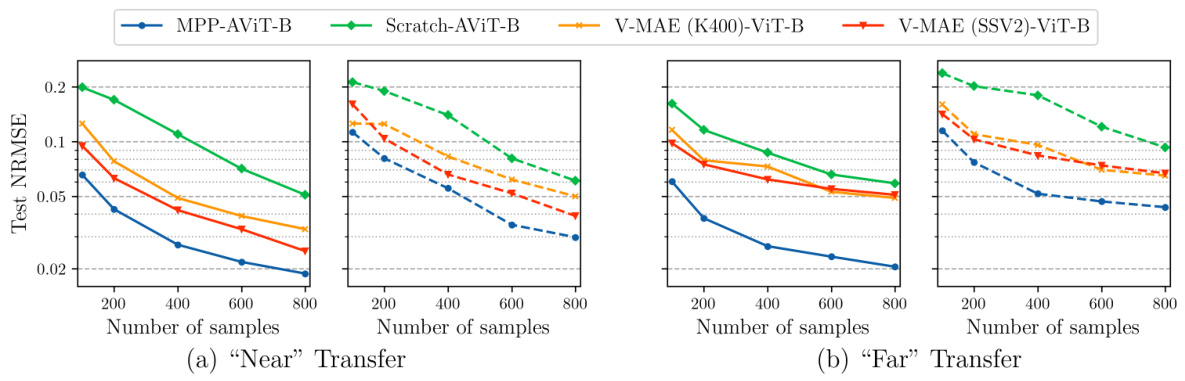

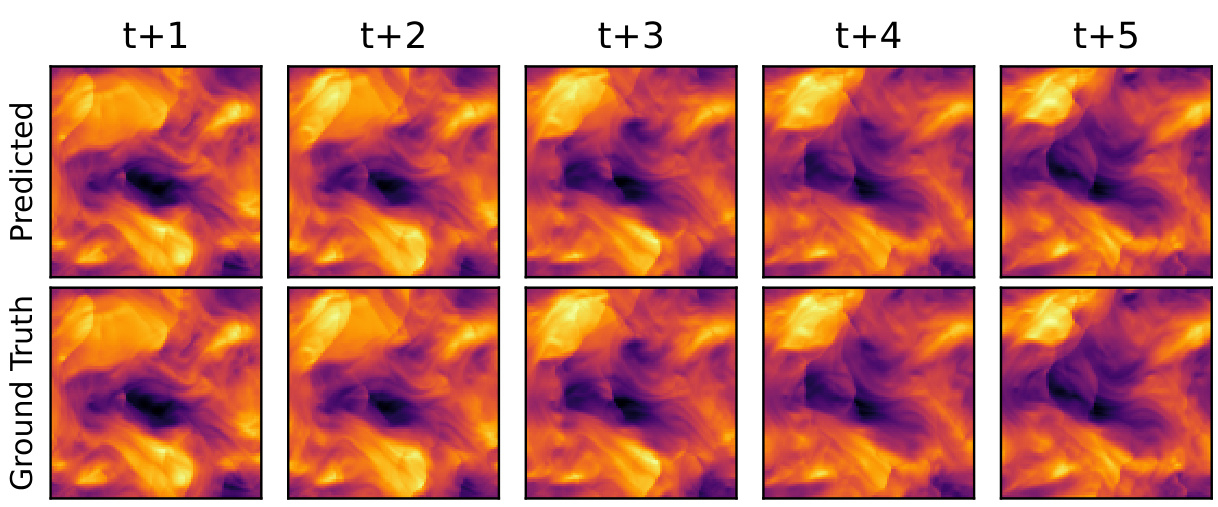

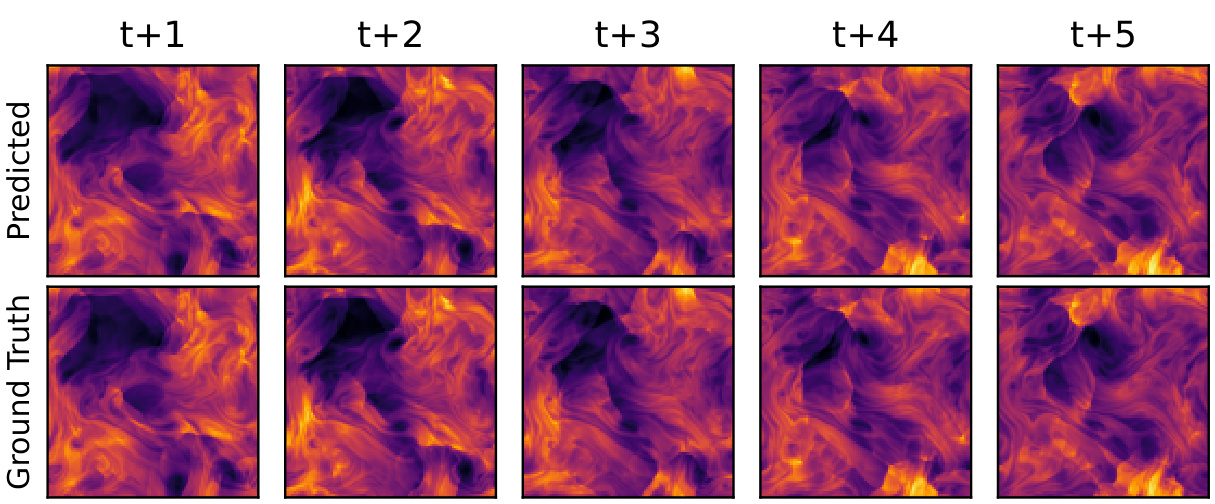

This figure compares kinetic energy snapshots for incompressible pretraining data and compressible finetuning data in two scenarios: ’near’ and ‘far’ transfer. The ’near’ transfer shows similar patterns between pretraining and finetuning, while ‘far’ transfer exhibits significantly different, more turbulent small-scale features in the finetuned data, demonstrating the model’s ability to learn and transfer knowledge to new physical behavior.

This figure compares the performance of MPP-pretrained models against models trained from scratch and video foundation models on transfer learning tasks. The tasks involve predicting the dynamics of previously unseen systems, both similar (’near’) and dissimilar (‘far’) to the systems used in pretraining. The results demonstrate that the MPP model significantly outperforms the others, especially for the more complex, ‘far’, transfer task. The solid lines represent the one-step prediction error and dashed lines show the average error over five steps.

This figure compares the performance of three different methods on transfer learning tasks: a model pretrained using Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP), a model trained from scratch, and a VideoMAE model (pretrained on video data). The x-axis shows the number of training samples, and the y-axis shows the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE). Two transfer scenarios are shown: ‘Near’ transfer (less turbulent), and ‘Far’ transfer (more turbulent). The results demonstrate that the MPP model significantly outperforms the other two, especially in the more challenging ‘Far’ transfer scenario, highlighting the benefits of MPP for transfer learning, particularly when dealing with systems exhibiting previously unseen or complex physical behaviors.

This figure compares the performance of MPP-pretrained models, models trained from scratch, and VideoMAE (a video foundation model) on transfer learning tasks. Two transfer learning scenarios are shown: ‘Near’ (similar physics to the pretraining data) and ‘Far’ (different physics). The results demonstrate that MPP-pretrained models significantly outperform both training from scratch and VideoMAE, especially in the ‘Far’ scenario, highlighting the benefit of MPP for transferring knowledge to unseen physical systems.

This figure compares the performance of MPP, training from scratch, and VideoMAE (a video foundation model) in a transfer learning setting. Two transfer tasks are considered, ‘Near’ and ‘Far’, representing systems with varying degrees of similarity to the training data. The results show that MPP consistently outperforms the other methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-physics pretraining, especially in low-data regimes.

This figure compares the performance of three different models on two transfer learning tasks: a ’near’ task and a ‘far’ task. The ’near’ task involves a system with physics similar to those seen during pretraining, while the ‘far’ task involves a system with significantly different physics. The results show that the MPP (Multiple Physics Pretraining) model significantly outperforms both a model trained from scratch and a video foundation model (VideoMAE) on both tasks, particularly the more challenging ‘far’ task. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the MPP model in transferring knowledge to systems with previously unseen physics.

This figure compares the performance of MPP, training from scratch, and VideoMAE on transfer learning tasks. It shows NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Squared Error) for both one-step predictions and predictions averaged over five time steps. Two transfer learning scenarios are presented: ‘Near’ and ‘Far’. The ‘Near’ task involves a system with similar physics to those seen during pretraining, while the ‘Far’ task involves a system with much more turbulent and complex behavior. The results demonstrate that MPP significantly outperforms both training from scratch and video-based pretraining, especially in the ‘Far’ scenario.

This figure illustrates the Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) architecture. The left panel shows the overall workflow: individual data normalization (RevIN), field embedding into a shared space, spatiotemporal transformer processing, and prediction. The right panel details the embedding and reconstruction process, highlighting the use of 1x1 convolutional filters and subsampling to create the matrices.

More on tables

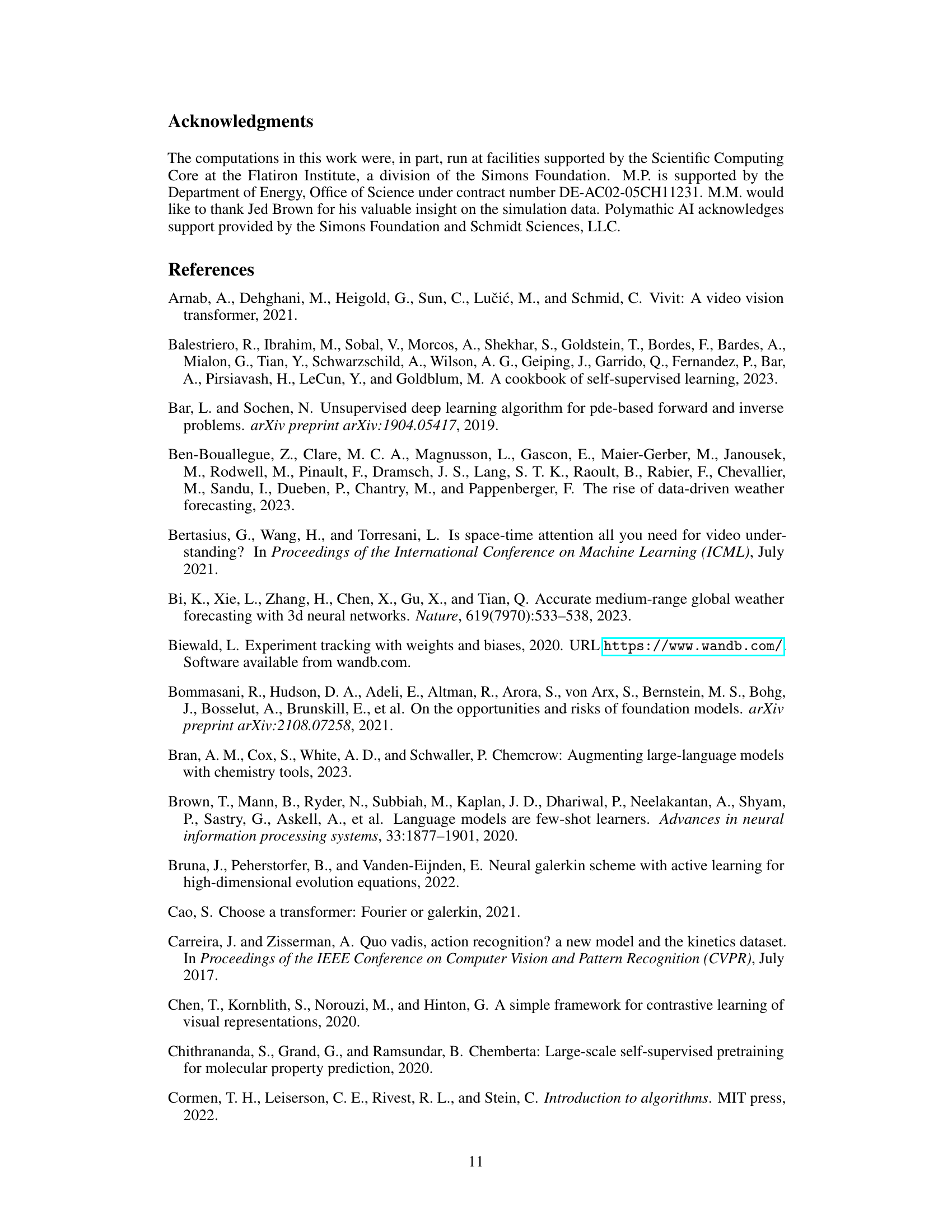

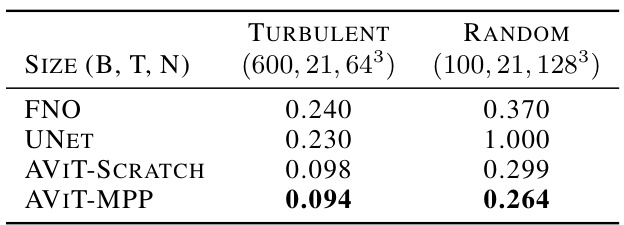

This table compares the normalized root mean squared error (NRMSE) for different models on 3D incompressible Navier-Stokes simulations. The models are evaluated on two different initial conditions: turbulent and random. The results show that inflating 2D models pretrained with MPP to 3D yields better performance than training from scratch, especially in the turbulent setting.

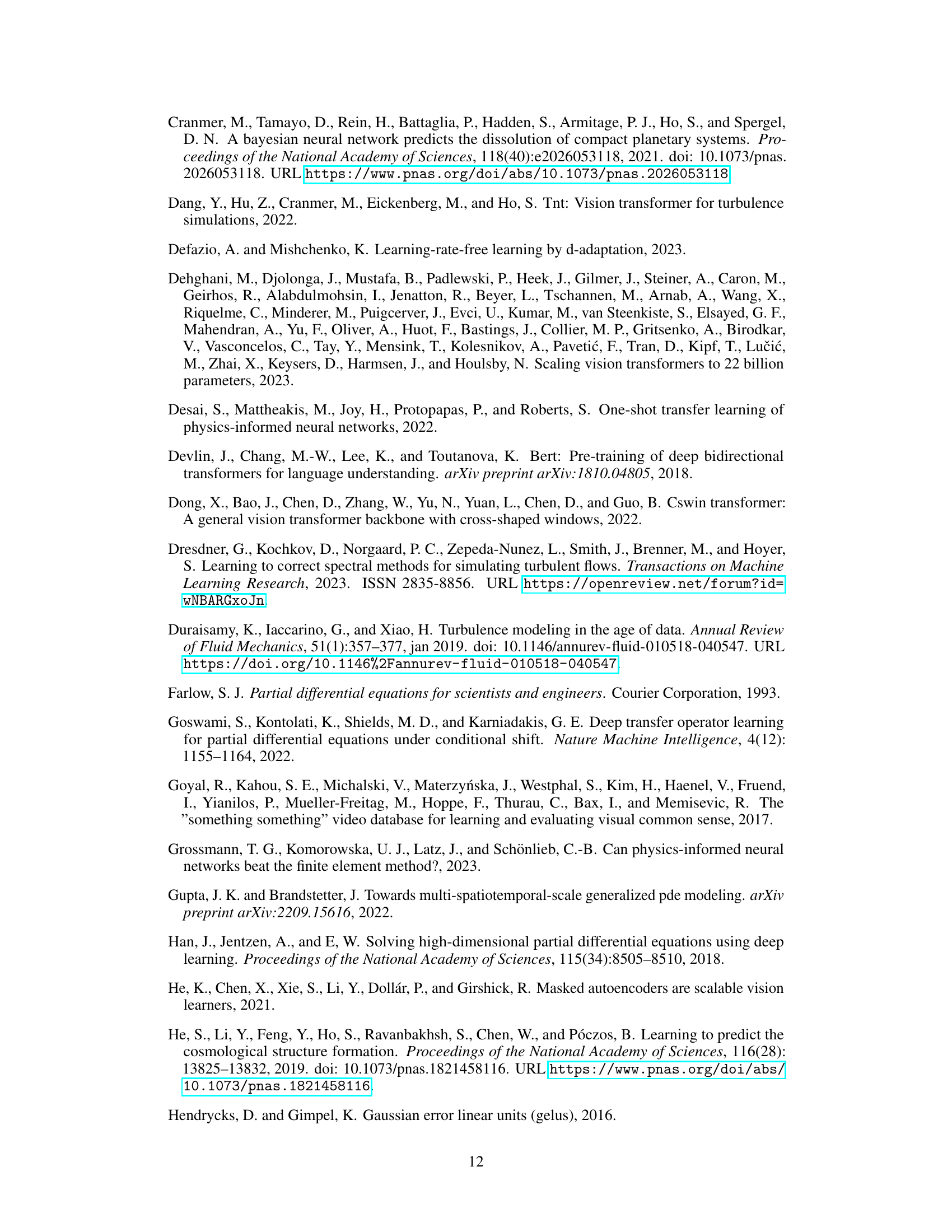

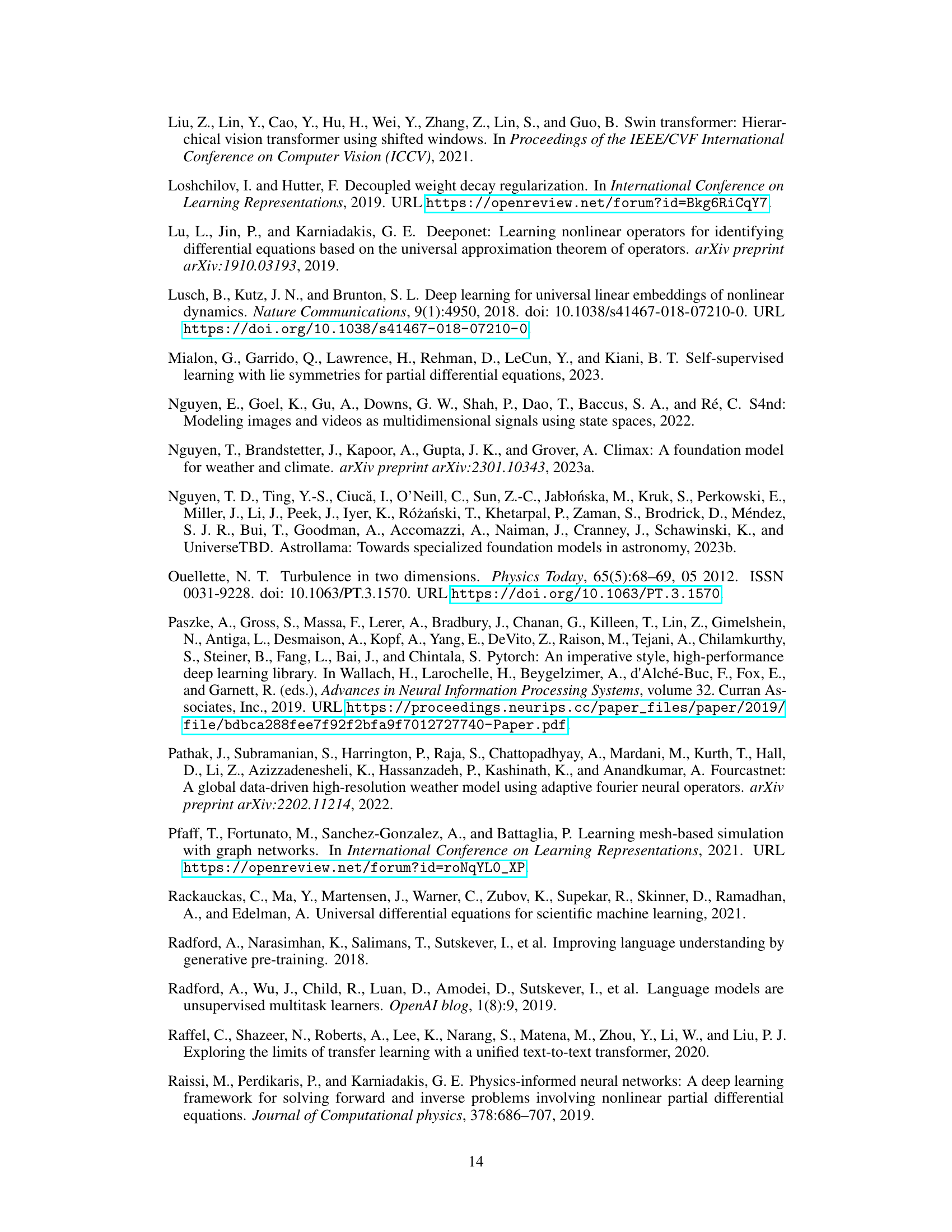

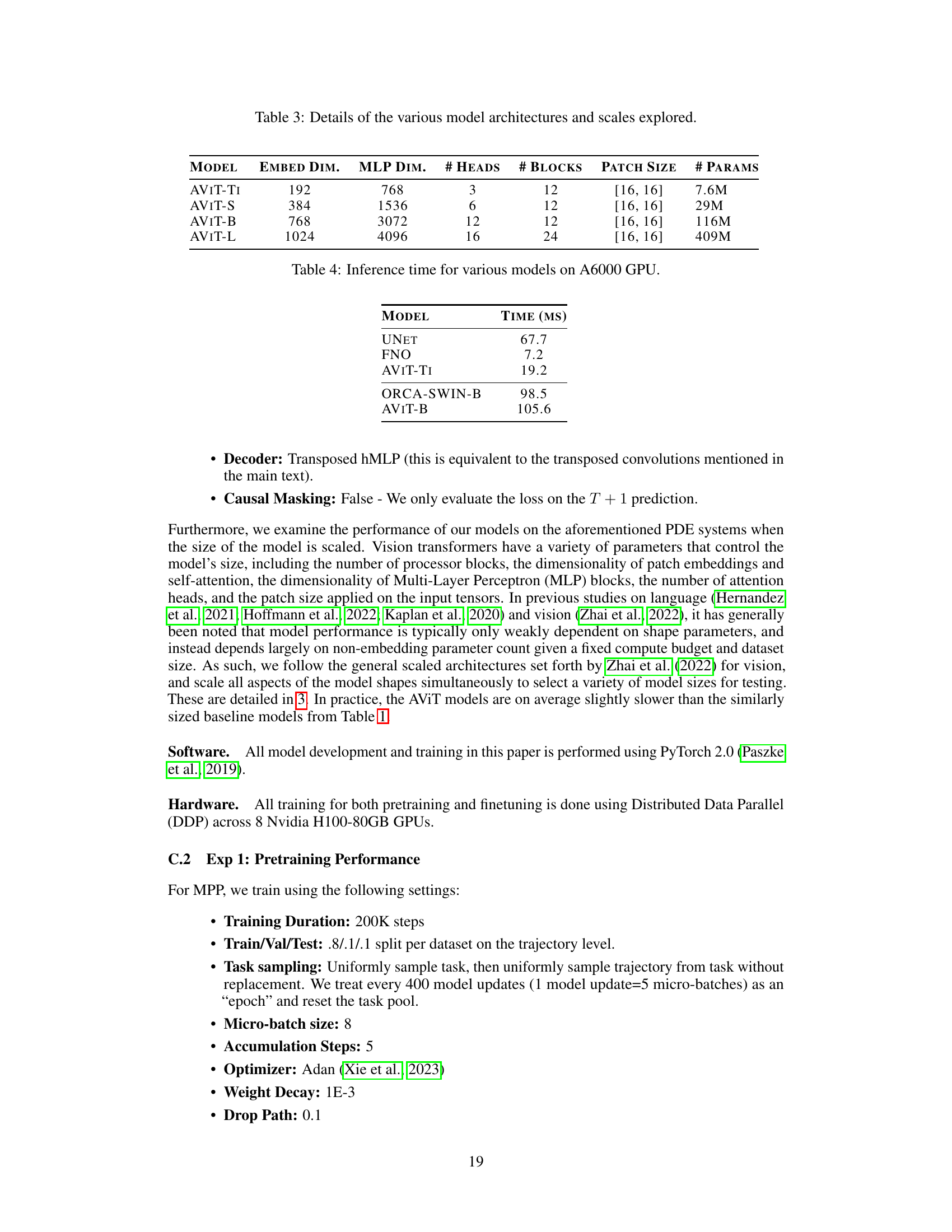

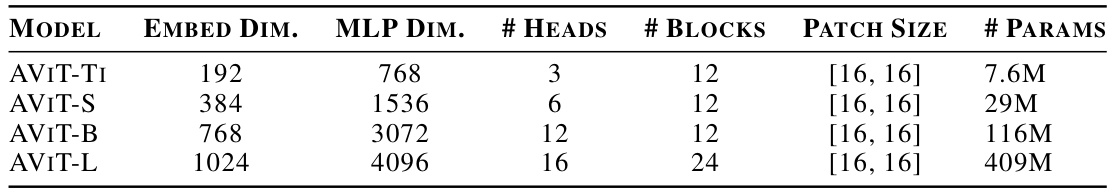

This table presents the hyperparameters of the different transformer models used in the experiments. The table shows the embedding dimension, MLP dimension, number of heads, number of blocks, patch size, and the total number of parameters for each model. Different model sizes (Ti, S, B, L) are used for evaluating how model performance changes with scale.

This table compares the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) of multiple physics pretraining (MPP) models against several dedicated baselines across three different physical systems: shallow water equations (SWE), 2D diffusion-reaction equations (DiffRe2D), and compressible Navier-Stokes equations (CNS). The results are shown for Mach numbers of 0.1 and 1.0, highlighting the performance of MPP across different scales and system complexities. Bold values indicate the top-performing models in each category.

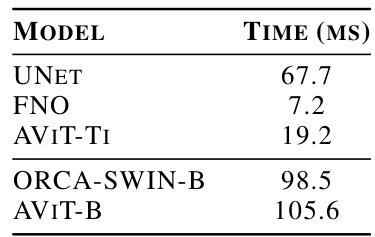

This table shows the effective learning rates used for fine-tuning two pre-trained VideoMAE models (K400 and SSV2) on two different transfer learning tasks: ‘Near’ and ‘Far’. The learning rates were determined empirically, likely through hyperparameter search, to achieve optimal performance on each task. The values indicate that the optimal learning rate for each model varies depending on the specific transfer task.

The table compares the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) of different models on three different tasks: Shallow Water Equations (SWE), 2D Diffusion-Reaction (DiffRe2D), and Compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS) at two different Mach numbers (0.1 and 1). The models are categorized into MPP-pretrained models (Multiple Physics Pretraining) and dedicated baselines. For each task and Mach number, the NRMSE is shown for each model. The best performing model for each task and Mach number is bolded.

This ablation study analyzes the impact of removing different components of the proposed architecture and training procedure. The table shows the NRMSE for four different PDE systems (SWE, DiffRe2D, CNS M1.0, CNS M0.1) under different conditions: the full model (MPP-AVIT-B), removing the normalized MSE training loss, removing the reversible instance normalization (RevIN), and removing both. The results highlight the contributions of each component to the overall performance of the model. Removing either the normalized loss or RevIN significantly degrades performance, and removing both leads to a drastic decrease in accuracy.

This table compares the normalized root mean squared error (NRMSE) of different models on three different partial differential equation (PDE) datasets: shallow water equations (SWE), 2D Diffusion-Reaction (DiffRe2D), and compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS) at two different Mach numbers (M=0.1 and M=1). The models include a variety of transformer-based architectures, both pretrained using the proposed Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) method and those trained specifically for each task. The table highlights the performance of a single MPP-pretrained model across different tasks, demonstrating its ability to match or outperform task-specific baselines, particularly in situations with limited data. The number of parameters in each model is also provided.

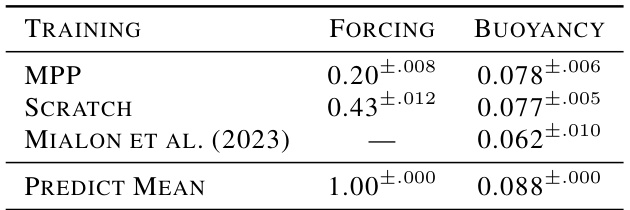

This table presents the results of an experiment that evaluates the ability of MPP-pretrained models to solve inverse problems, specifically identifying forcing and buoyancy parameters from simulation data. The RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) values are shown for the MPP, scratch (training from scratch), and a baseline method from Mialon et al. (2023). A constant prediction baseline is also included to provide a context for comparison. The results demonstrate that models pretrained using the MPP approach achieve lower RMSE than training from scratch and the Mialon et al. baseline for both the forcing and buoyancy inverse problems.

This table compares the performance of Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) against several baselines on three different Partial Differential Equation (PDE) datasets: Shallow Water Equations (SWE), 2D Diffusion-Reaction (DiffRe2D), and Compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS). The table shows the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) for each model and dataset. The models are grouped by architecture and size, allowing for comparison of performance across different model capacities. The best performing model within each size range and overall are highlighted in bold. Missing values are indicated by dashes.

This table compares the performance of Multiple Physics Pretraining (MPP) against other methods on three different PDEs: Shallow Water Equations (SWE), 2D Diffusion-Reaction (DiffRe2D), and Compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS). Results are shown for different Mach numbers (M = 0.1 and M = 1). The table highlights the NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Square Error) achieved by each method and shows that MPP generally performs competitively, especially when considering its task-agnostic nature.

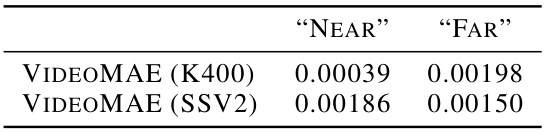

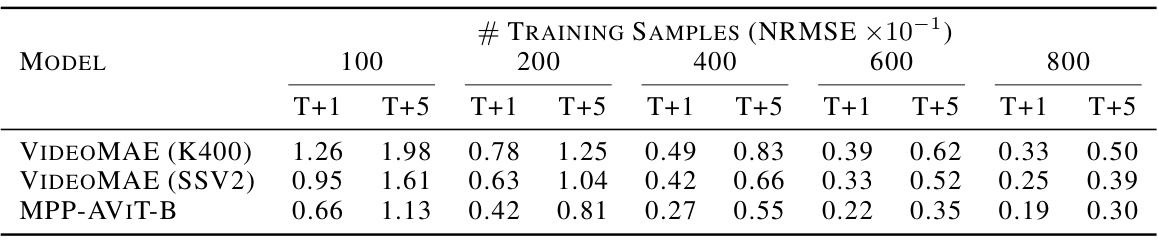

This table presents the test NRMSE results for the ‘Near’ Compressible Navier-Stokes dataset with a Mach number of 0.1 and a viscosity of 0.01. It compares the performance of VideoMAE (K400), VideoMAE (SSV2), and MPP-AVIT-B models across different numbers of training samples (100, 200, 400, 600, 800) for both one-step prediction (T+1) and five-step prediction (T+5). The results show the normalized root mean squared error, demonstrating how the accuracy of each model improves with increasing training data and comparing the models’ ability to extrapolate over multiple timesteps.

This table compares the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) of various models on three different partial differential equation (PDE) datasets: Shallow Water Equations (SWE), 2D Diffusion-Reaction (DiffRe2D), and Compressible Navier-Stokes (CNS). The models are categorized into MPP-pretrained models (Multiple Physics Pretraining) and dedicated baselines. The table shows the performance of models with different numbers of parameters, highlighting the best performing model for each dataset and overall. The bolded values indicate the best results for each dataset and size range. Dashes represent instances where precision was not provided in the original source.

Full paper#