↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) faces the significant challenge of inconsistent client participation, impacting model accuracy and training efficiency. Existing FL algorithms often assume either predictable client availability or impose significant computational overheads. The inconsistent and unpredictable client availability is further complicated by heterogeneity (different clients having different patterns of availability) and non-stationarity (the patterns changing over time).

To address these issues, the authors propose FedAWE, a new FL algorithm. FedAWE cleverly compensates for missing data from unavailable clients, using novel techniques like ‘adaptive innovation echoing’ and ‘implicit gossiping’. These techniques efficiently manage resources while ensuring fair updates from all clients, leading to improved accuracy and faster convergence. The algorithm’s effectiveness is rigorously tested and proven through mathematical analysis and real-world experiments.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles a critical challenge in federated learning: unreliable client participation. It offers a novel algorithm, efficient in terms of computation and memory, that performs well despite heterogeneous and dynamic client availability. This directly impacts the scalability and robustness of real-world federated learning systems, opening avenues for more practical and resilient applications.

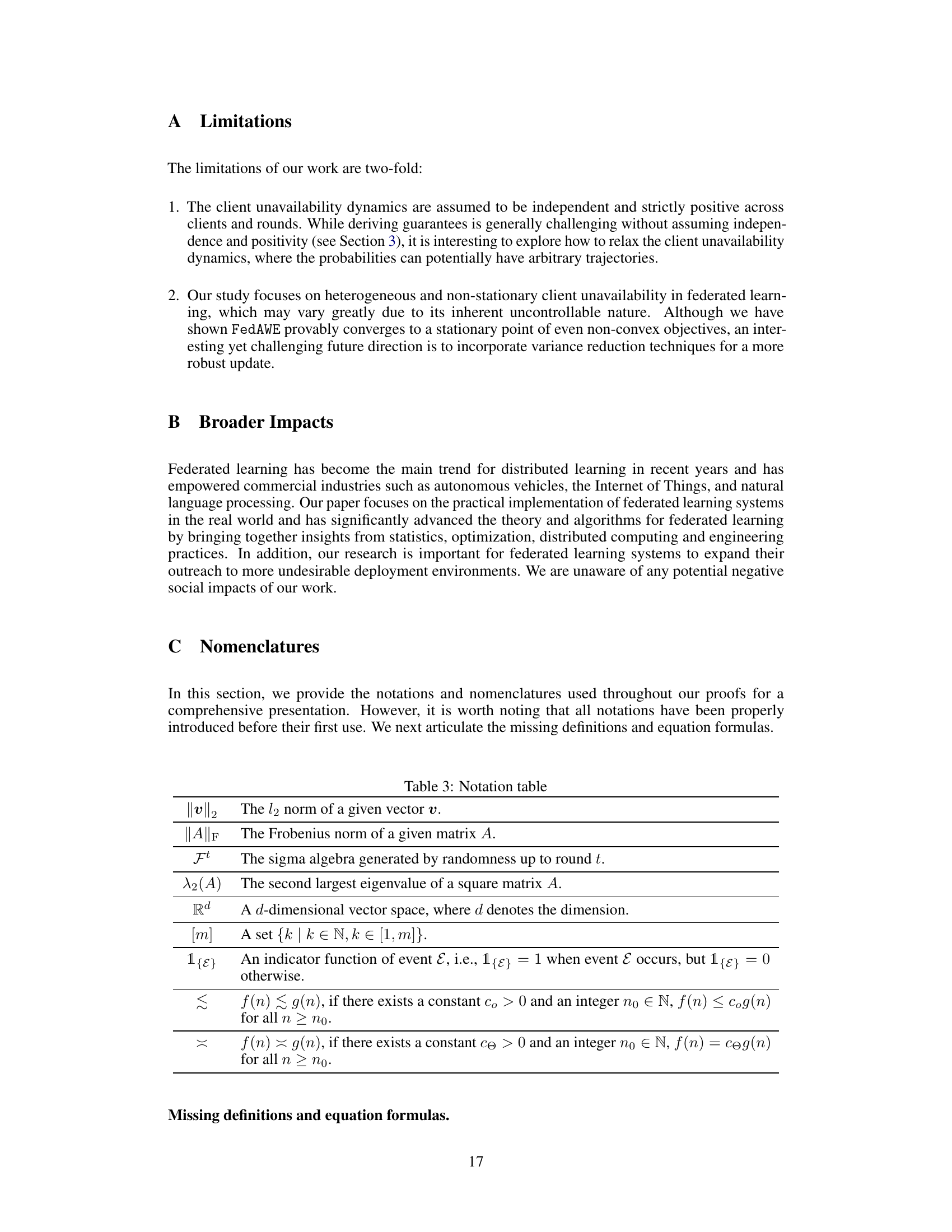

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of a federated learning system. There is a central parameter server that communicates with multiple clients (laptop, smartphone, desktop computer, smartwatch). Each client has a probability pti of being available at time t, and these probabilities are heterogeneous (different for each client) and non-stationary (change over time). The figure visualizes the heterogeneity and non-stationarity of client participation in the federated learning process.

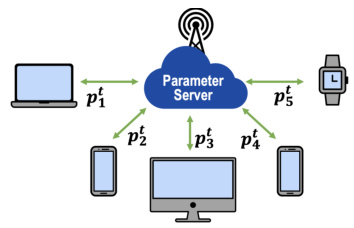

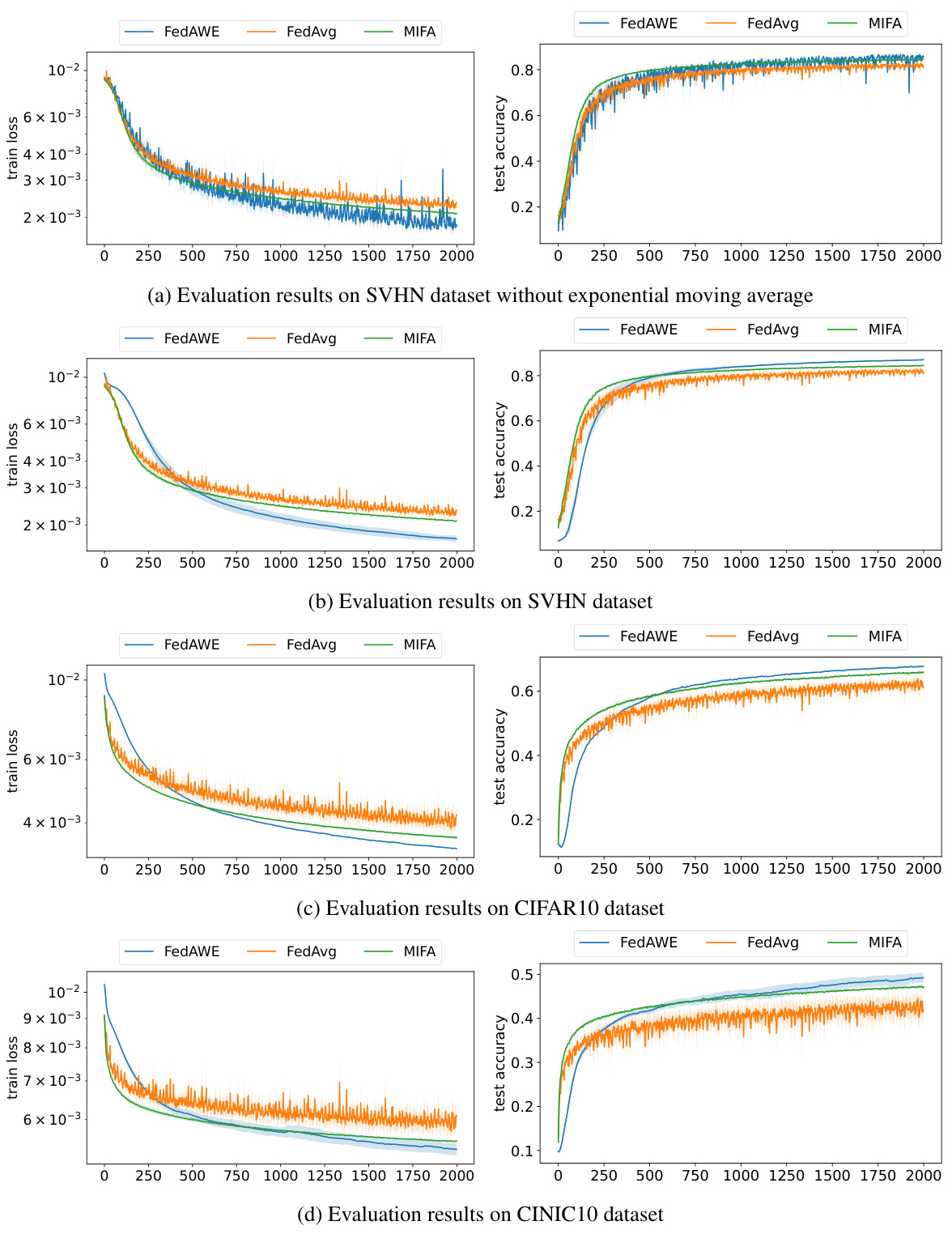

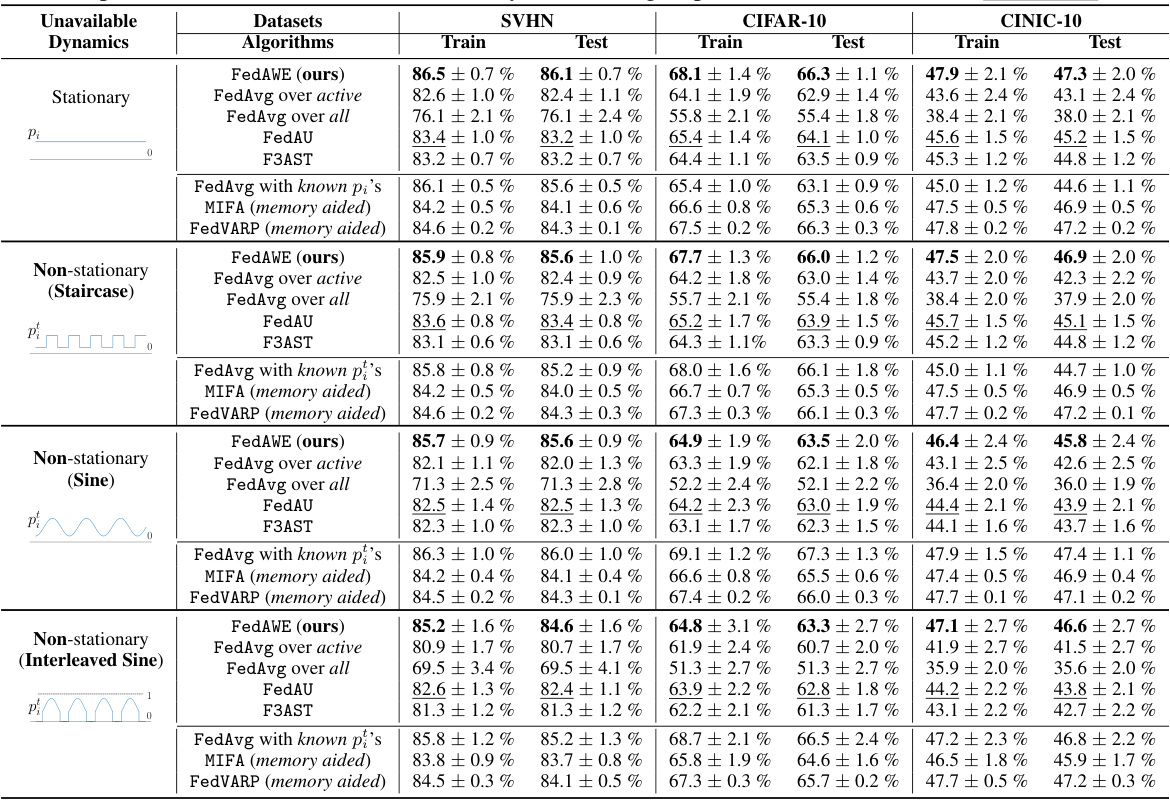

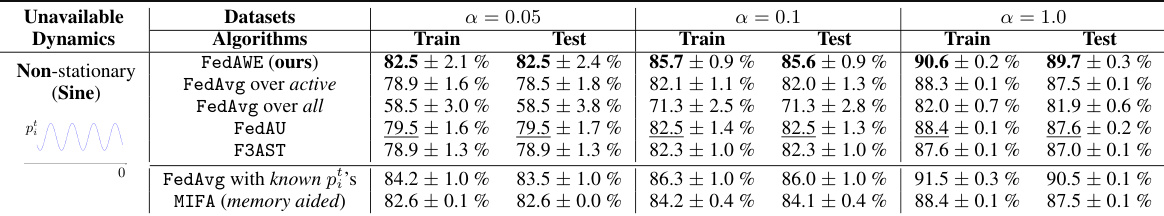

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10) to compare the performance of FedAWE against several baseline federated learning algorithms. The results show mean accuracy and standard deviation, averaged over the final 50 rounds of 2000 total rounds. Algorithms are grouped into those that do not use memory or prior knowledge of client availability and those that do, to allow for a fair comparison. The best performing algorithm in the first group is highlighted in boldface.

In-depth insights#

FedAvg’s Bias Issue#

The paper highlights a crucial bias in the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm when dealing with heterogeneous and non-stationary client availability. FedAvg’s inherent weighting of client updates based on participation frequency disproportionately favors clients with higher availability. This leads to a skewed global model that does not accurately reflect the overall data distribution, a critical issue when clients have varying degrees of participation due to factors like network connectivity or device usage. The non-stationary nature of this availability exacerbates the problem, making it difficult to predict and correct for the bias. The paper emphasizes that this bias significantly impacts FedAvg’s performance, particularly in real-world scenarios. The authors illustrate this through concrete examples, demonstrating how heterogeneous and time-varying availability directly contributes to suboptimal model training. Addressing this bias is essential for reliable and effective federated learning, requiring novel algorithmic solutions like the FedAWE proposed in the paper, that explicitly account for the heterogeneity and non-stationary characteristics of client participation.

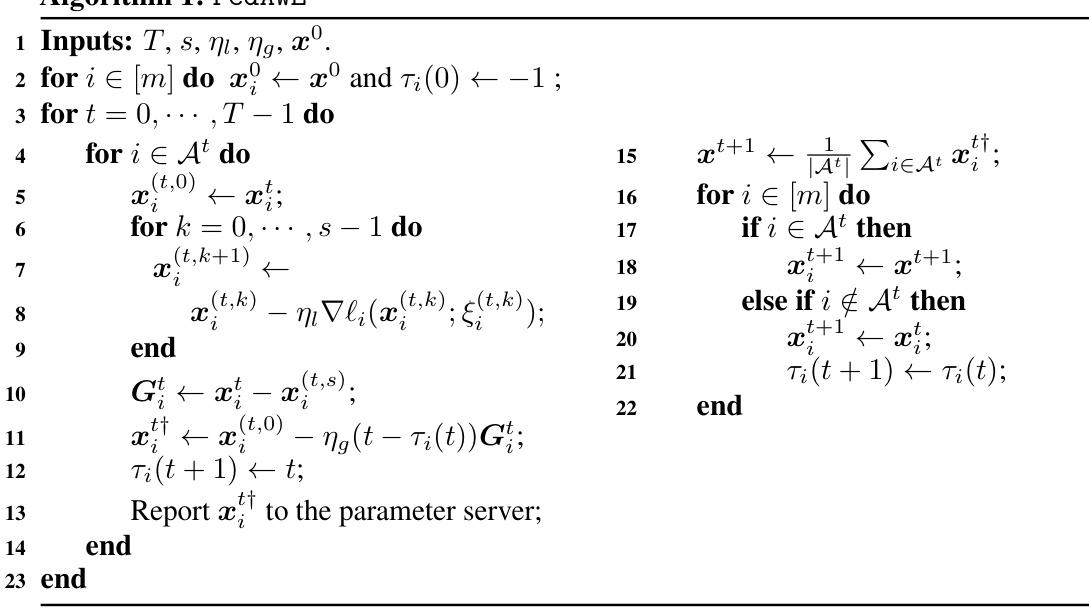

FedAWE Algorithm#

The proposed FedAWE algorithm represents a novel approach to federated learning, designed to address the challenges posed by heterogeneous and non-stationary client unavailability. FedAWE’s core innovation lies in its two key algorithmic structures: adaptive innovation echoing and implicit gossiping. Adaptive innovation echoing compensates for missed computations by unavailable clients, ensuring that all clients effectively contribute the same number of local updates. This is achieved using O(1) additional computation and memory per client, thus maintaining high efficiency compared to standard FedAvg. Implicit gossiping, meanwhile, facilitates a balanced information mixture across clients through implicit communication, correcting biases that arise from inconsistent participation. The algorithm’s convergence to a stationary point is mathematically proven, even for non-convex objectives, and it exhibits the desired linear speedup property. This makes FedAWE particularly well-suited for real-world federated learning scenarios, where unreliable client participation is a major concern. Numerical experiments confirm FedAWE’s superior performance and robustness over existing methods, showcasing its practical value in diverse deployment environments.

Convergence Analysis#

A rigorous convergence analysis is crucial for establishing the reliability and efficiency of any machine learning algorithm, and federated learning is no exception. In a federated learning setting, the convergence analysis must account for the unique challenges posed by distributed data, communication constraints, and the potential for intermittent client availability. A comprehensive analysis would typically involve demonstrating that the algorithm converges to a stationary point of the global objective function, ideally at a certain rate. Establishing a linear speedup property is often a key goal, showing that the algorithm’s efficiency scales linearly with the number of participating clients. Furthermore, the analysis should consider the impacts of factors like data heterogeneity across clients and non-stationary client participation patterns. Robustness guarantees, ensuring convergence even under adverse conditions, are also important aspects to address. The techniques employed in the analysis might range from standard convergence proofs for convex or non-convex optimization problems to more specialized methods that handle the intricacies of distributed systems. Assumptions made within the analysis are equally critical and should be clearly stated, as they influence the generality and applicability of the results. Finally, a good convergence analysis should provide clear insights into the algorithm’s behavior and offer practical guidance on parameter tuning for optimal performance in real-world deployment scenarios. The inclusion of numerical experiments to corroborate theoretical findings is a significant plus.

Real-World Datasets#

The use of real-world datasets is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness and generalizability of federated learning algorithms. Real-world datasets often exhibit significant heterogeneity and non-stationarity, unlike the idealized data distributions commonly used in simulations. This means that client data may be vastly different, and the availability of clients can change unpredictably over time. A robust algorithm should perform well under these conditions, highlighting the importance of testing with challenging, realistic datasets. The choice of datasets will also influence the types of insights gained. For instance, datasets focused on mobile applications might reveal different challenges compared to those based on IoT devices. In-depth analysis of real-world dataset performance includes examining the impact of data heterogeneity and the impact of non-stationary client availability on algorithm convergence and accuracy. It is important that the analysis considers metrics beyond simple accuracy, perhaps including fairness and robustness. Overall, a careful and thorough evaluation using real-world datasets is essential for demonstrating the practical utility of federated learning approaches.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for expanding upon the current findings. Addressing the limitations of independent and strictly positive client availability assumptions is crucial. Exploring techniques to handle more complex, non-stationary dynamics, perhaps through incorporating variance reduction methods or robust optimization strategies, would significantly enhance the algorithm’s real-world applicability. Another key area involves extending the theoretical analysis to cover scenarios with correlated client unavailability. This would require more sophisticated mathematical techniques to deal with the dependencies between clients’ availability and potentially require modifications to the algorithm itself. Investigating the impact of non-convex objectives with more complex structures and non-iid local data distributions is also critical to strengthen the algorithm’s robustness in real-world settings. Finally, empirical validation of the algorithm across a wider array of datasets and network conditions would solidify the conclusions drawn from the experiments presented in the paper. The exploration of these areas holds significant promise for advancing the field of federated learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the impact of heterogeneity in client availability on the expected output of the FedAvg algorithm. The x-axis represents p1, the probability that client 1 is available, and the y-axis represents p2, the probability that client 2 is available. The color scale represents the Euclidean distance between the expected output of FedAvg (Xoutput) and the optimal solution (x*). The figure demonstrates that heterogeneity in client availability can lead to a significant bias in the global model, with the distance between Xoutput and x* increasing as the difference between p1 and p2 increases.

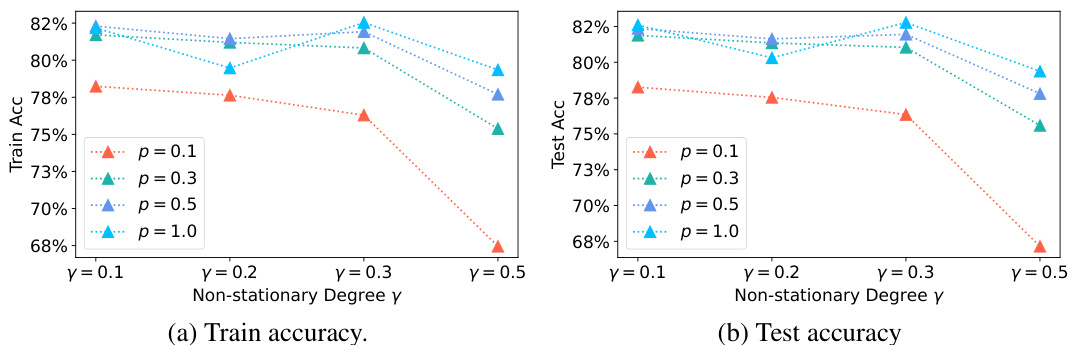

The figure shows the impacts of non-stationary client availability on the performance of FedAvg. Two subplots display training accuracy and test accuracy, respectively, as a function of the non-stationarity degree (γ). Each subplot further breaks down the results based on different client availability probabilities (p). The results clearly demonstrate that increased non-stationarity in client availability leads to a significant drop in both training and test accuracy for FedAvg.

This figure illustrates the probabilities of client availability (p_i) in a federated learning system. It shows that these probabilities are both heterogeneous (different for different clients) and non-stationary (changing over time). This heterogeneity and non-stationarity are key challenges addressed by the FedAWE algorithm proposed in the paper. The server and multiple clients are depicted in the figure.

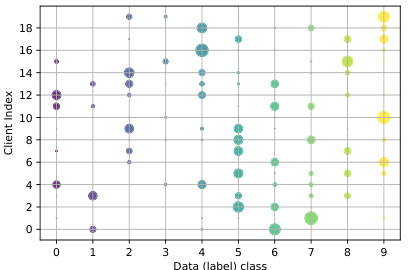

This figure visualizes data heterogeneity across 20 clients using a Dirichlet distribution with parameter α = 0.1. Each point represents a client, the x-axis shows the image class, and the y-axis is the client index. The size of each point indicates the proportion of images of that class held by the client, and the color distinguishes different classes.

This histogram shows the distribution of the generated probabilities (pi) for client availability in a federated learning system with 100 clients. The x-axis represents the probability pi, and the y-axis represents the count of clients with that probability. The distribution is skewed to the left, indicating that most clients have a probability of availability below 0.5.

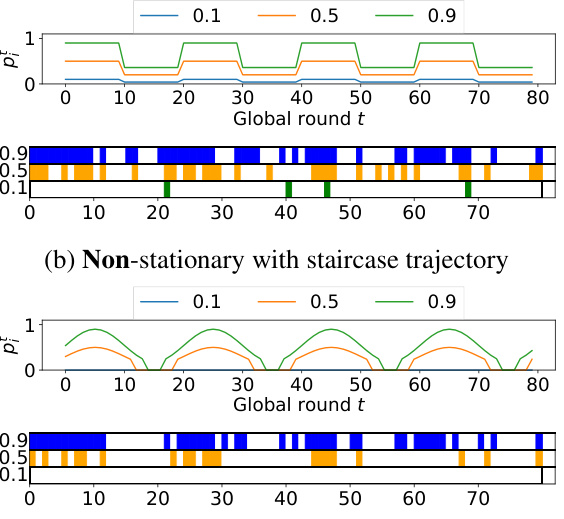

This figure shows four different patterns of client availability over time. Each pattern is characterized by a probability trajectory (top row) and a visualization of client availability (bottom row). The top row shows the probability of a client being available at each round, with different lines representing different base probabilities (pᵢ). The bottom row uses colored boxes to visually represent client availability, with each box corresponding to a client and each row showing the availability across multiple rounds. The patterns include stationary availability and three types of non-stationary availability (staircase, sine, and interleaved sine).

This figure illustrates four different client unavailability dynamics: stationary, non-stationary with staircase trajectory, non-stationary with sine trajectory, and non-stationary with interleaved sine trajectory. Each sub-figure shows the probability trajectory (top) and a visualization of client availability (bottom) for three different base probabilities (pᵢ ∈ {0.1, 0.5, 0.9}). The visualizations use colored boxes to represent whether a client was available in each round. The figure demonstrates the varying patterns of availability across different dynamics and highlights the complexity of modeling real-world client unavailability.

The figure shows the impact of non-stationary client availability on the performance of the FedAvg algorithm in an image classification task. Two sub-figures present the training accuracy and test accuracy, respectively, as functions of the non-stationarity degree (γ). The results demonstrate that as the non-stationarity increases, the accuracy of the FedAvg algorithm decreases significantly, indicating that non-stationary client availability is a major challenge for federated learning.

More on tables

This table presents the results of several federated learning algorithms on three benchmark datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10). The algorithms are compared across four different client unavailability scenarios, and the results are presented in terms of mean test accuracy and standard deviation. The table is divided into groups based on whether the algorithms use memory or prior knowledge of client availability. The best performing algorithm in the first group (no memory or prior knowledge) is bolded for each scenario.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10) comparing FedAWE with other state-of-the-art algorithms. The table shows the train and test accuracy for various algorithms under different client unavailability dynamics (stationary and non-stationary). Algorithms are categorized based on whether they leverage additional memory or prior knowledge of client availability.

This table presents the results of several federated learning algorithms on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10). The algorithms are grouped into those that do not use memory or prior knowledge of client availability, and those that do. Performance is measured by mean accuracy ± standard deviation, averaged over the last 50 rounds of 2000 total rounds. The best performing algorithm in the memory-agnostic group is highlighted in bold, while the second-best is underlined. The table allows for comparison of FedAWE’s performance against various baselines under different client unavailability scenarios.

The table compares the performance of FedAWE with other state-of-the-art algorithms on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10) under various client unavailability dynamics. It shows the mean test accuracy and standard deviation, averaged over the last 50 rounds of training, for different algorithms. The algorithms are grouped by whether they use memory or prior knowledge of client availability.

This table details the specifications used for the neural networks in the experiments. It shows the architecture (convolutional layers, ReLU activation, max-pooling, dropout, fully connected layers), the loss function (cross-entropy), the learning rate scheduling (a formula based on the global training round), the number of local steps per round, the total number of global training rounds, and the batch size used for training.

This table presents the results of several federated learning algorithms on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, CINIC-10). The algorithms are grouped into those that do not use additional memory or prior knowledge of client availability, and those that do. The table shows the training and testing accuracy for each algorithm on each dataset. The best performing algorithm among those without memory or prior knowledge is shown in boldface, while the second-best is underlined.

This table presents the results of several federated learning algorithms on three benchmark datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, CINIC-10) under various client unavailability dynamics. The results are categorized into algorithms that don’t use extra memory or prior knowledge of client availability and those that do. The table shows mean test accuracy with standard deviation, averaged over the final 50 rounds of 2000 total rounds. The best performing algorithm in the first category is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of several federated learning algorithms on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10). It compares the performance of FedAWE against several baseline algorithms under different client unavailability dynamics (stationary and non-stationary). The table highlights the accuracy achieved by each algorithm and categorizes them based on whether they leverage memory or prior knowledge of client availability. The best performing algorithm among those not using extra memory or knowledge is shown in boldface, while the second best is underlined.

The table compares the performance of FedAWE and other federated learning algorithms on three real-world datasets (SVHN, CIFAR-10, and CINIC-10) under different client unavailability dynamics. It shows the training and testing accuracy with standard deviation, averaged over the last 50 rounds of 2000 total rounds. Algorithms are grouped by whether they use memory or prior knowledge of client availability.

Full paper#