↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many applications utilize Large Language Models (LLMs) as language agents; however, aligning these agents to individual user preferences remains a challenge. Traditional fine-tuning approaches are costly, challenging to scale, and may degrade performance. This paper introduces PRELUDE, a framework that infers user preferences from their edits to the agent’s responses. This avoids the need for costly and complex fine-tuning.

The core of PRELUDE is CIPHER, a simple yet effective algorithm that utilizes an LLM to infer user preferences based on edit history. CIPHER retrieves similar contexts from the history to aggregate preferences, which are used to improve future responses. Evaluated on summarization and email writing tasks using a GPT-4 simulated user, CIPHER significantly outperformed baselines in terms of lower edit distance while only having a small overhead in LLM query cost. The learned user preferences also showed significant similarity to ground truths.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel and efficient approach to improve the alignment of large language models (LLMs) with user preferences using readily available user edit data, thus reducing the cost and complexity of traditional fine-tuning methods. It offers a scalable solution for personalizing LLM agents without sacrificing safety guarantees or interpretability, opening new avenues for research in interactive learning and LLM personalization.

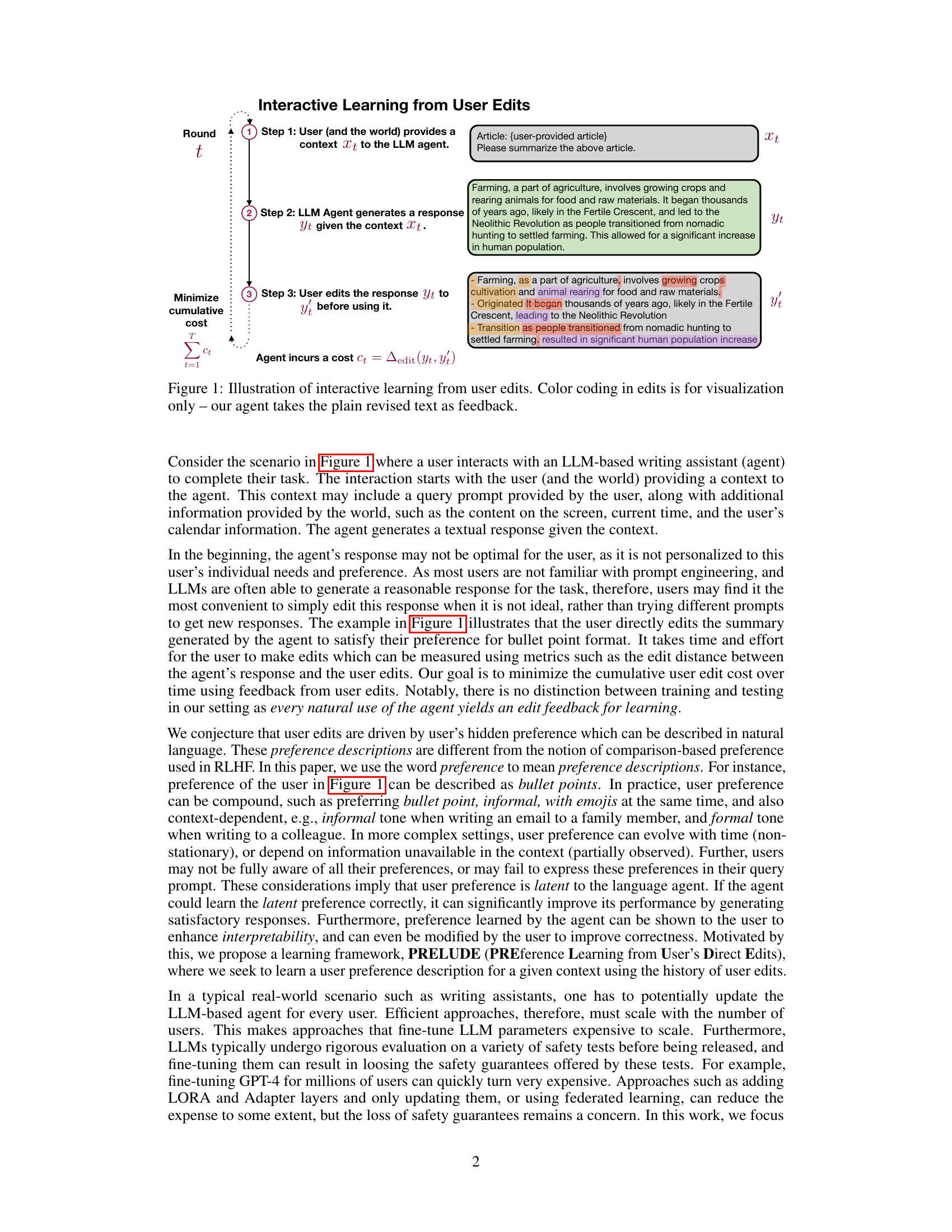

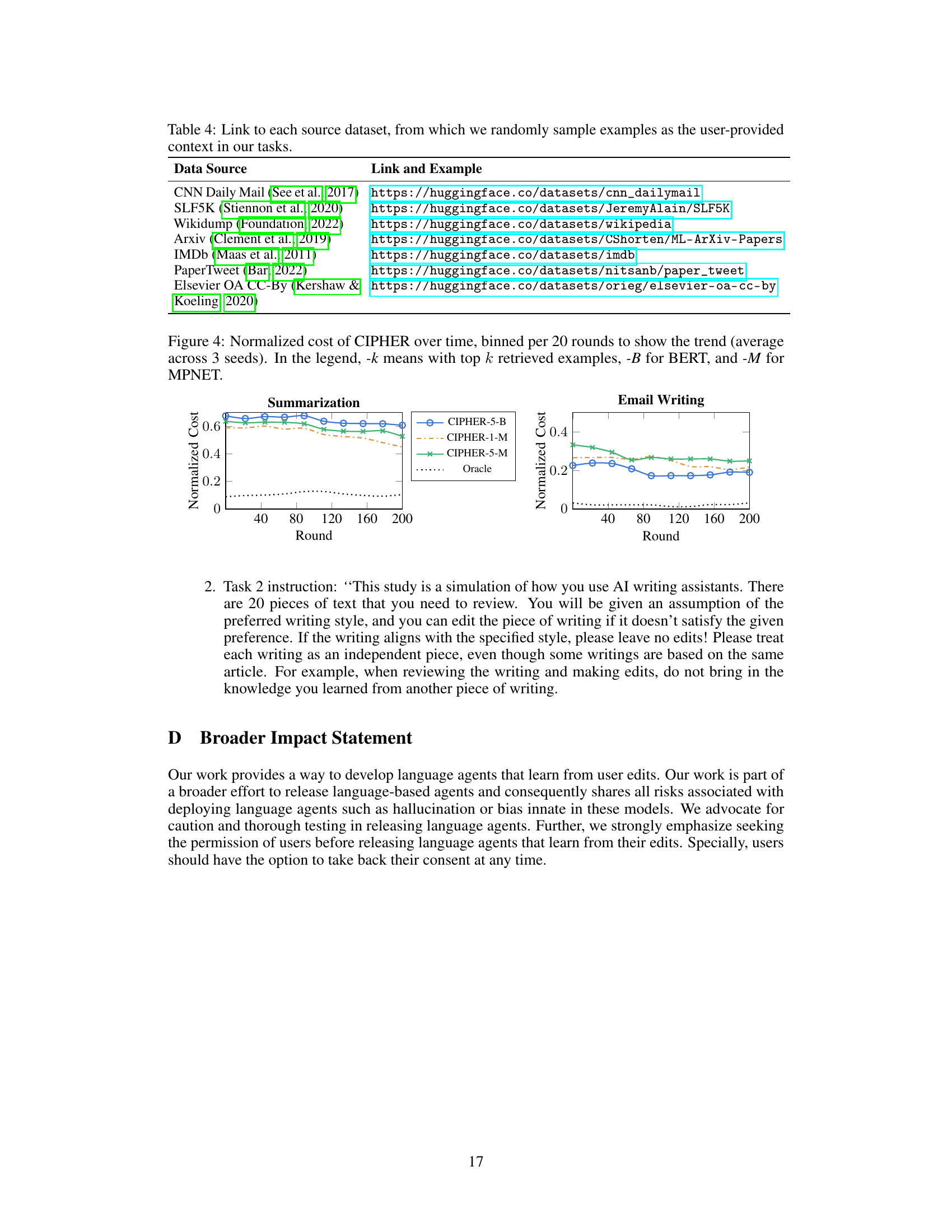

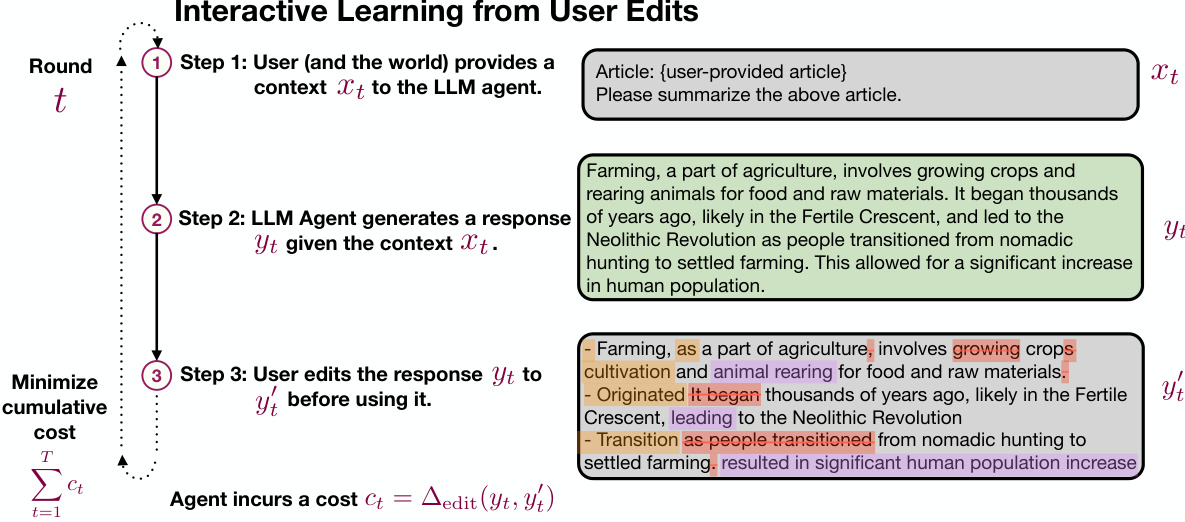

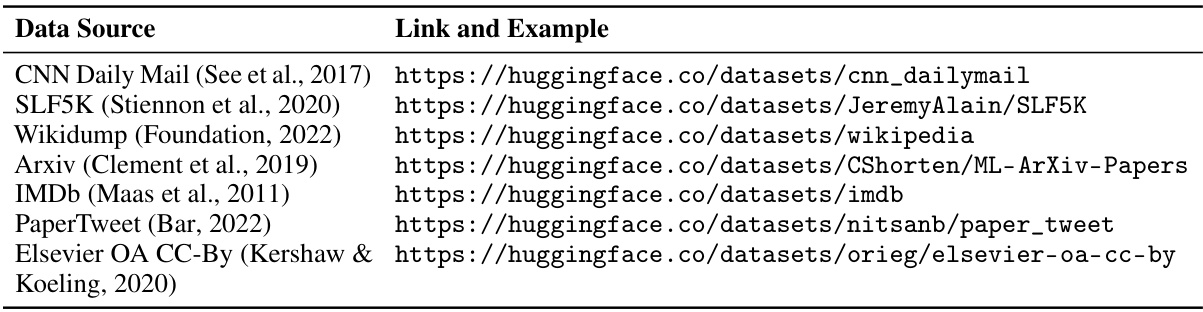

Visual Insights#

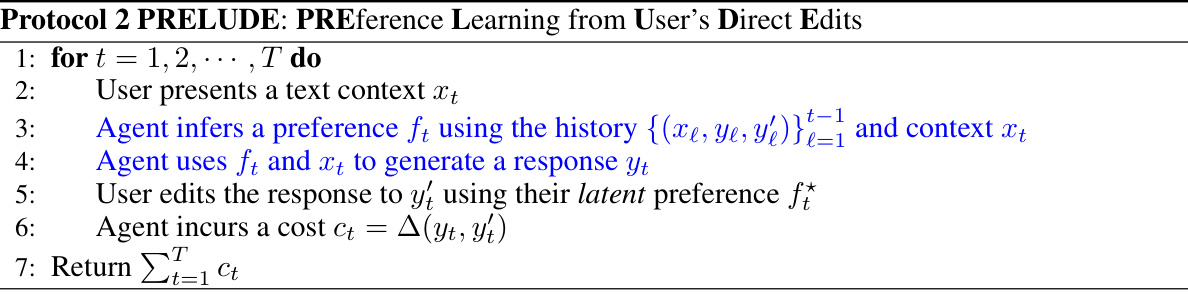

This figure illustrates the interactive learning process from user edits. The process starts with the user providing context (such as an article to summarize) to an LLM agent. The agent then generates a response. The user can then edit this response, and the edit is considered feedback for the agent. The agent incurs a cost based on the edit distance between the original response and the edited response. The goal is to minimize the cumulative cost of edits over time. The color coding in the example edit is just for visualization; the agent processes only the plain text.

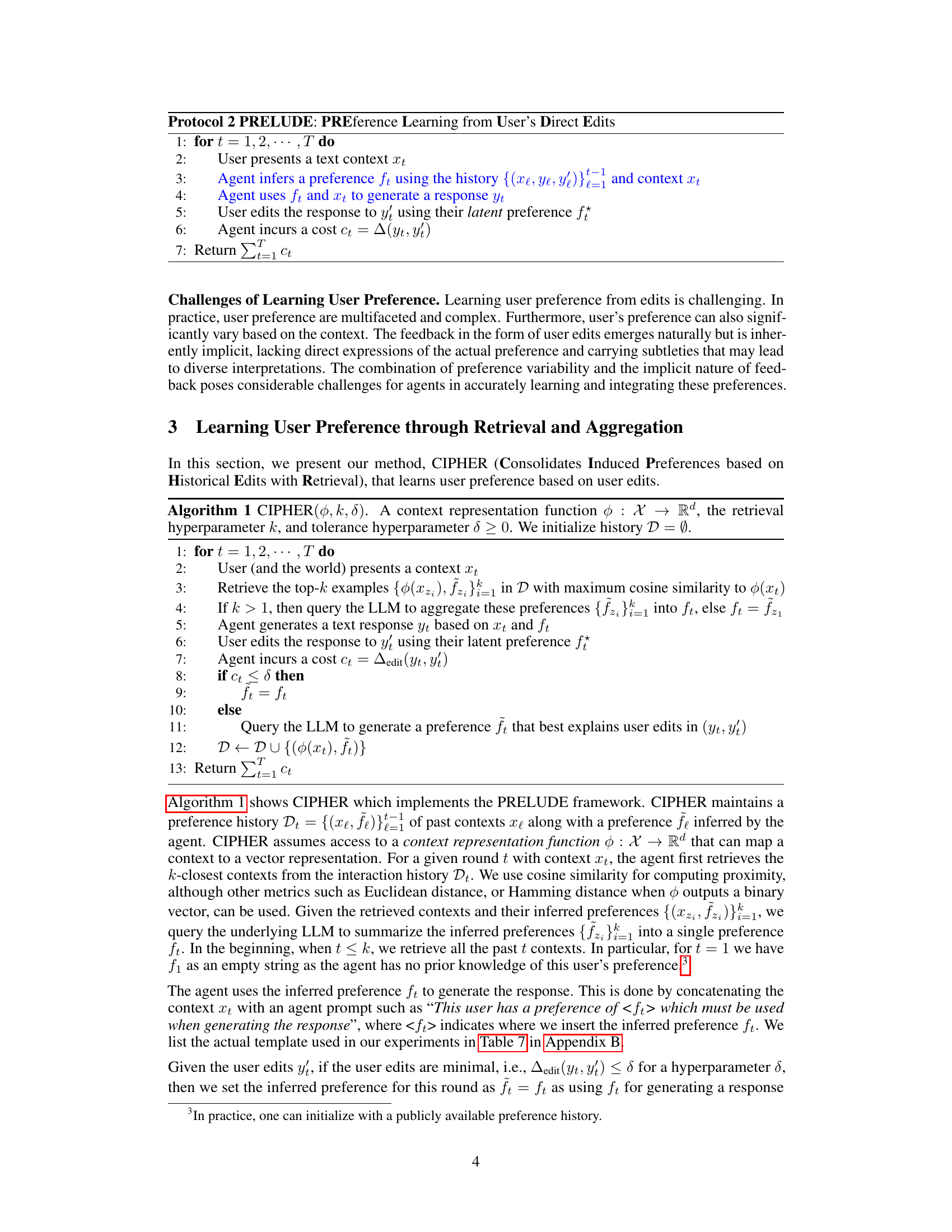

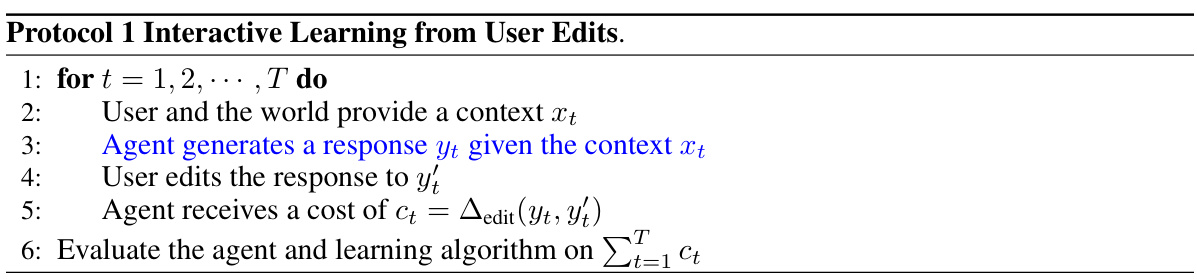

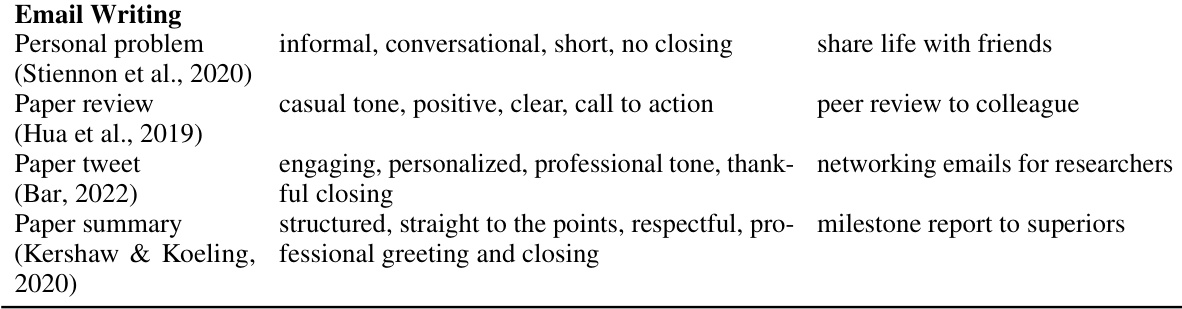

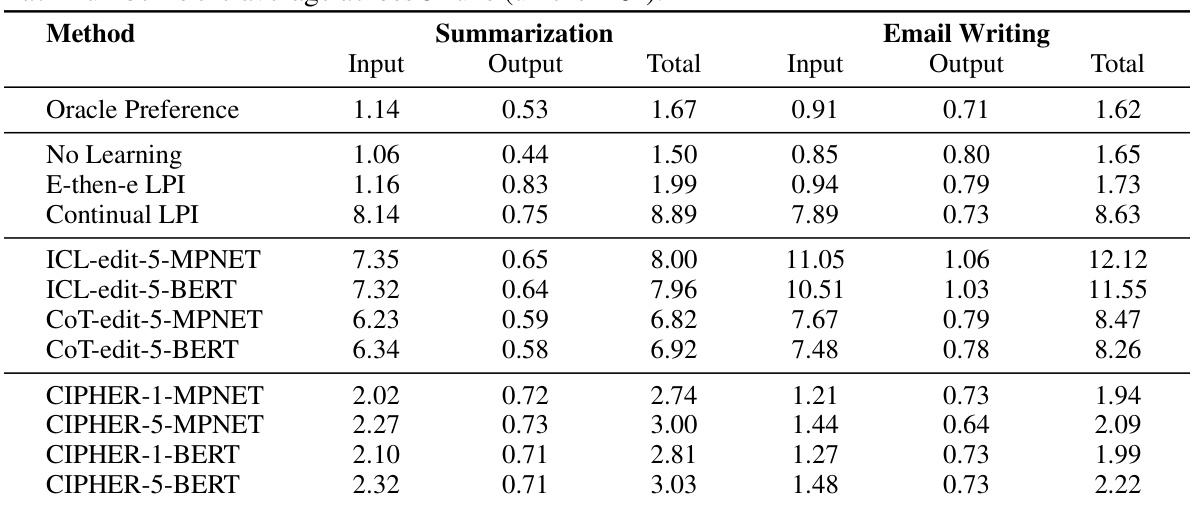

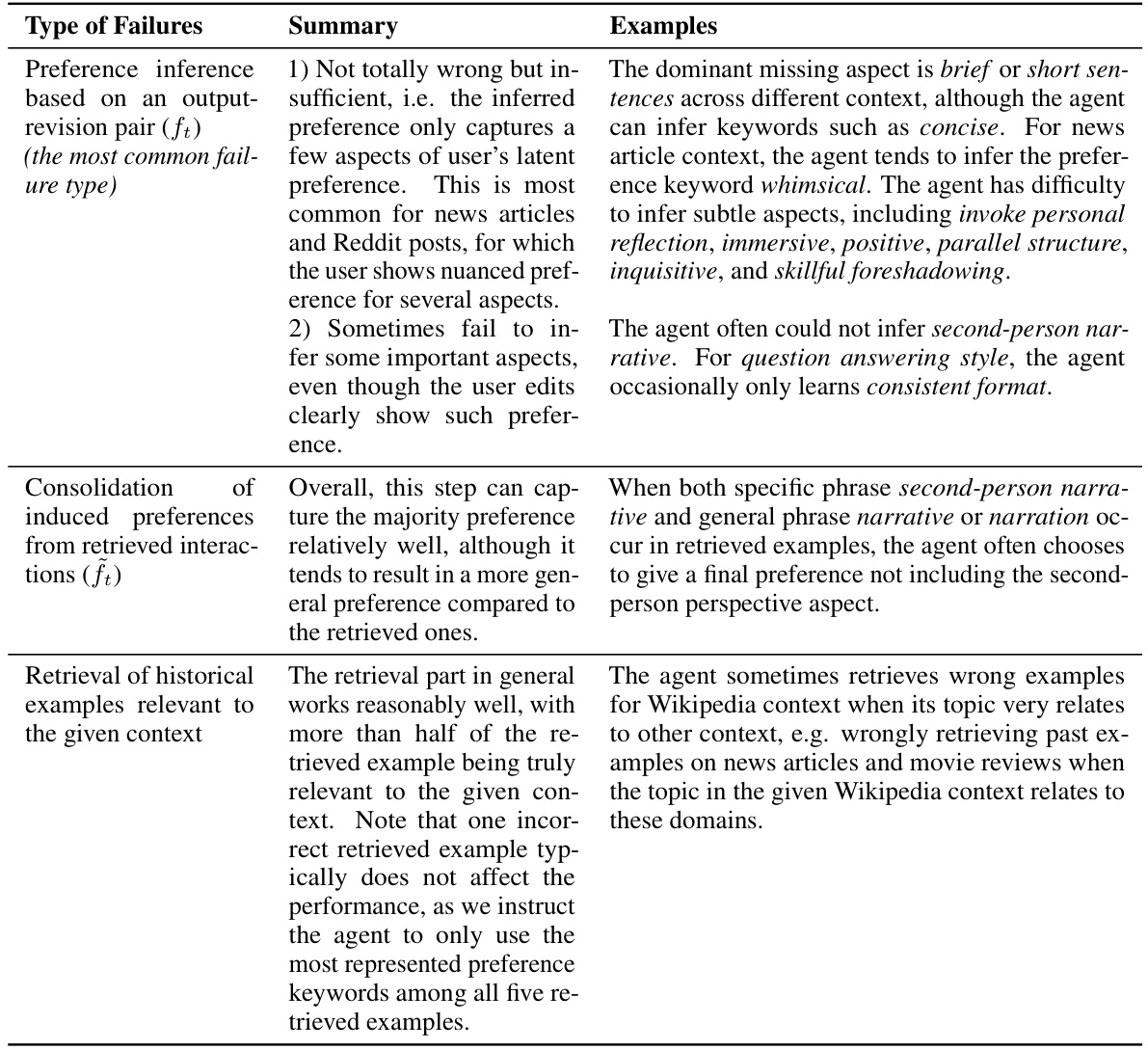

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiments, comparing different methods (including the proposed CIPHER algorithm and baselines) across two tasks (summarization and email writing). Three metrics are reported for each method: cumulative edit distance cost, accuracy in predicting the user preference, and the expense in terms of the number of tokens processed by the LLM. The results show that CIPHER outperforms the baselines in terms of edit distance cost while having competitive LLM expense.

In-depth insights#

Latent Pref Learning#

Latent preference learning, in the context of large language models (LLMs), focuses on inferring a user’s hidden preferences from their interactions with the system, specifically by analyzing edits made to the LLM’s output. This contrasts with explicit feedback mechanisms, such as ranking multiple outputs. The core idea is to learn a representation of the user’s preferences without needing them to articulate their preferences directly, thus reducing user effort and making the system more adaptive and user-friendly. A key challenge lies in the implicit and often subtle nature of user edits, which can vary depending on context and task. Successful approaches involve sophisticated techniques that can model the complex relationship between user edits, context, and underlying preferences. Effective algorithms require carefully designed methods for data representation, retrieval of similar past interactions, and inference of descriptive preference models using the power of LLMs themselves. The potential benefits include more personalized and efficient interaction, reduced user effort, and improved interpretability of the learned preferences. Ultimately, latent preference learning is crucial for building truly adaptive and intelligent LLM agents that can seamlessly align with individual user needs and styles.

CIPHER Algorithm#

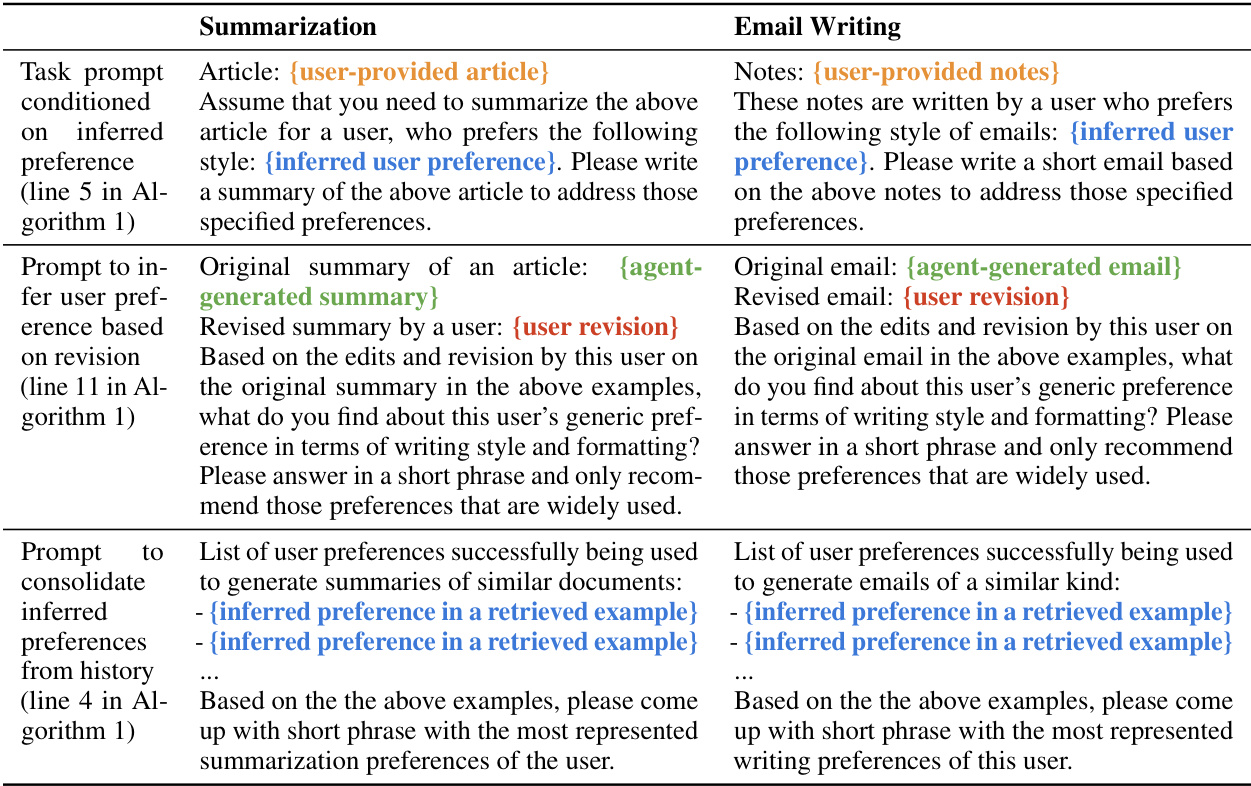

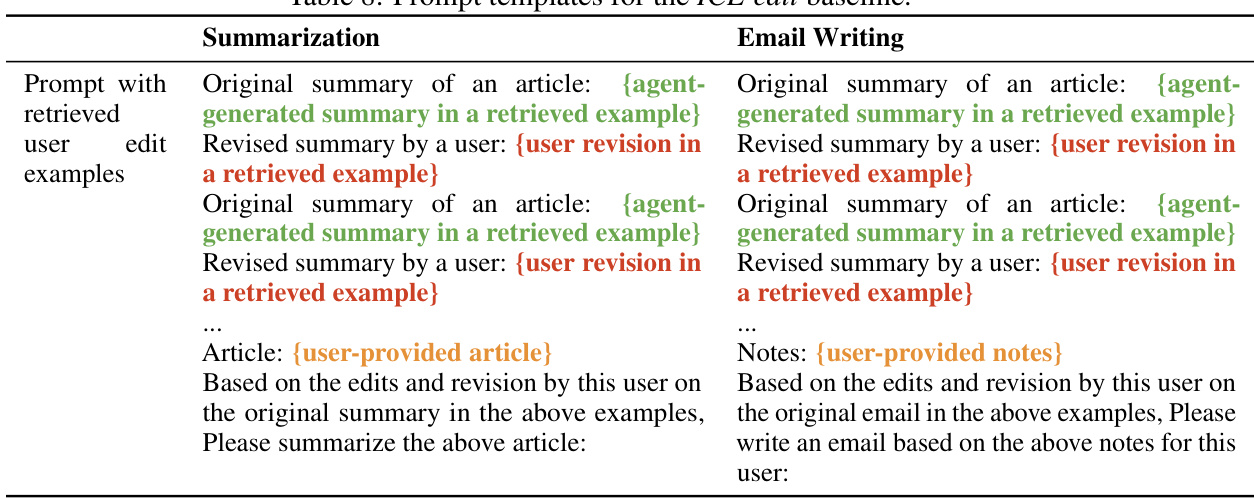

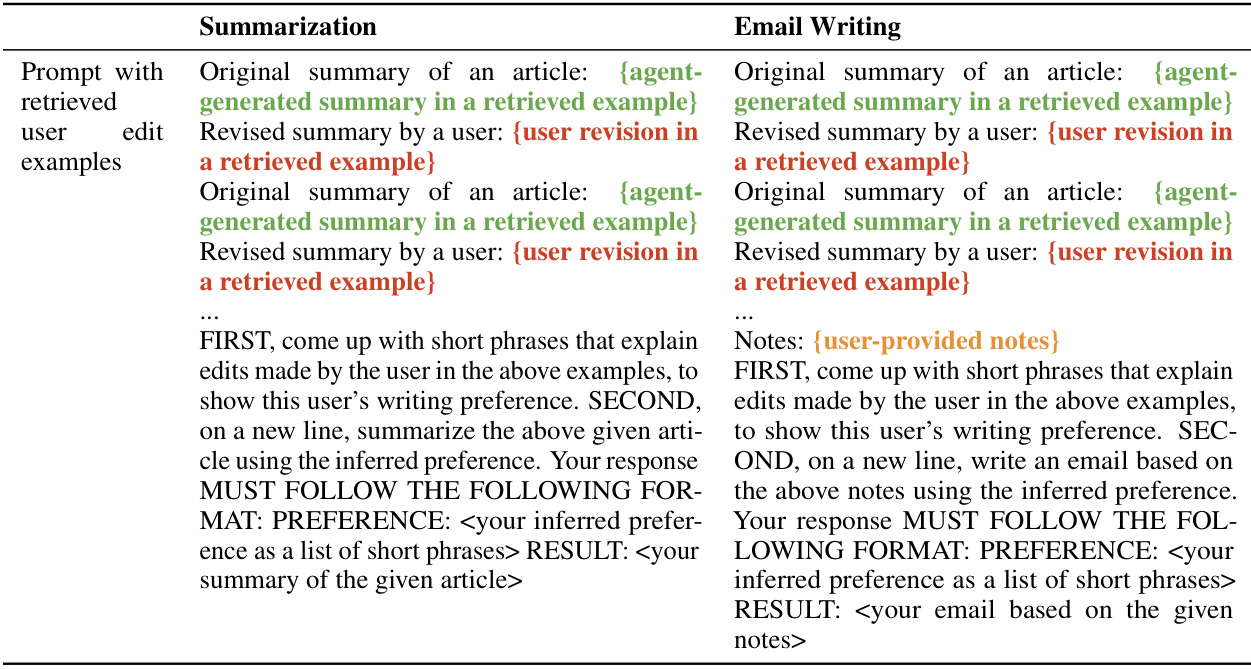

The CIPHER algorithm, as described in the context, is a crucial component of the PRELUDE framework. Its core function is to infer user preferences from historical edit data, leveraging the capabilities of a large language model (LLM). Rather than costly and potentially detrimental fine-tuning, CIPHER works by analyzing user edits to generate a descriptive representation of the user’s latent preferences. This description is then used to inform subsequent response generation, effectively tailoring the LLM’s output to the individual user’s style and needs. Efficiency is a key design goal of CIPHER, and it achieves this by employing a retrieval-based approach, utilizing the LLM only when necessary to aggregate preferences from similar past contexts. The system’s ability to learn and adapt to evolving user preferences is also highlighted as a key strength, offering improved performance and a potentially personalized user experience over time. Crucially, the method’s interpretability is explicitly mentioned, allowing users to view and potentially modify the learned preferences, which adds to its user-friendliness.

Interactive LLMs#

Interactive LLMs represent a paradigm shift in how large language models (LLMs) are used. Instead of passively receiving prompts and generating outputs, interactive LLMs foster a dynamic exchange with users. This engagement often involves iterative refinement, where initial LLM responses serve as a starting point for further interaction. Users provide feedback – edits, clarifications, or additional instructions – which the LLM incorporates to produce improved outputs. This iterative process is key, allowing the LLM to adapt to user preferences and generate more personalized and accurate results. The feedback loop is crucial for improving the LLM’s alignment with user needs, effectively closing the gap between the LLM’s understanding and the user’s true intent. However, challenges remain, particularly in managing the computational cost of this iterative process and ensuring effective feedback mechanisms. Future research will likely focus on optimizing these interactions and exploring novel ways to leverage human feedback to enhance the LLM’s performance and user experience. Ultimately, interactive LLMs aim to transcend the limitations of traditional, static interactions, offering a more intuitive and user-friendly interface for interacting with these powerful language technologies.

User Edit Cost#

The concept of “User Edit Cost” in the context of a research paper analyzing LLM-based language agents is multifaceted. It likely represents a crucial metric for evaluating the agent’s performance and alignment with user preferences. Lower edit costs indicate that the generated text better satisfies user needs, reducing the time and effort required for manual corrections. The metric likely measures the number of edits made by users (insertions, deletions, substitutions), perhaps weighted by their complexity or impact. Cost calculation could incorporate not only the quantity of edits but also the difficulty or time required for each edit. A thoughtful approach to this metric would likely involve a discussion of its limitations, including potential biases in user editing behavior and the subjectivity of determining edit complexity. Furthermore, the study might investigate how user edit cost correlates with other performance metrics such as LLM query cost or response quality. Ultimately, the user edit cost serves as a valuable indicator of the agent’s overall effectiveness in providing satisfactory and personalized language outputs.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents exciting avenues for expansion. Extending the framework to more complex language agents that perform multi-step reasoning would greatly enhance its capabilities. Currently, the framework relies on a simple prompt-based agent; however, incorporating planning mechanisms could improve performance and expand applicability. Furthermore, exploring different context representation functions beyond MPNET and BERT, and comparing diverse similarity metrics for context retrieval, could optimize performance and address the task-dependent nature of preference learning. Investigating the stability and robustness of the learned preferences over time and across varying user interactions is crucial. The current work simulates user behaviour; gathering real-world user data and studying long-term usage patterns would validate the model’s effectiveness and highlight any unforeseen limitations. Finally, analyzing the impact of different retrieval strategies and evaluating the effectiveness of aggregation techniques using LLMs merit further exploration. Also, a direct comparison with fine-tuning approaches, quantifying the trade-offs between cost, scalability, and safety guarantees, would provide crucial insights.

More visual insights#

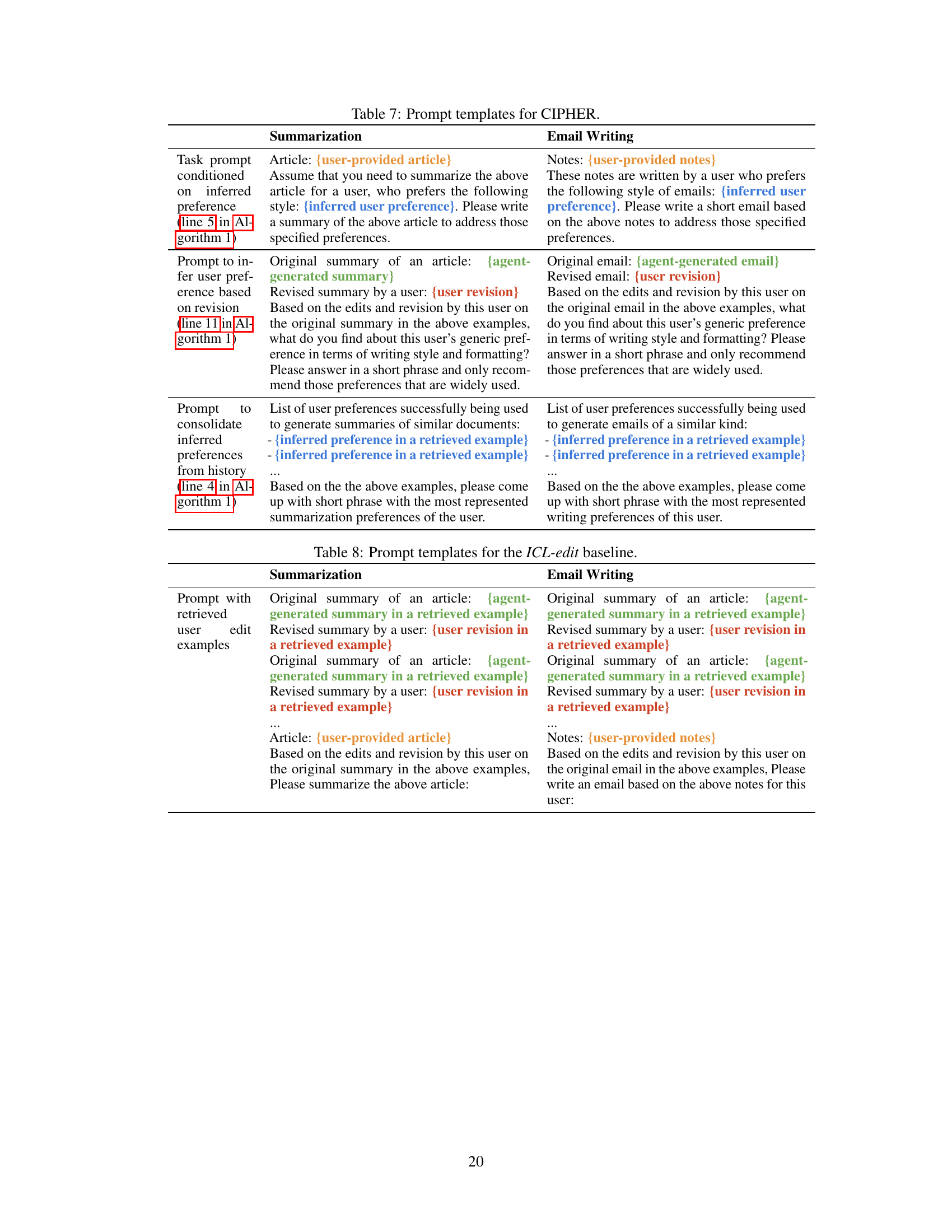

More on figures

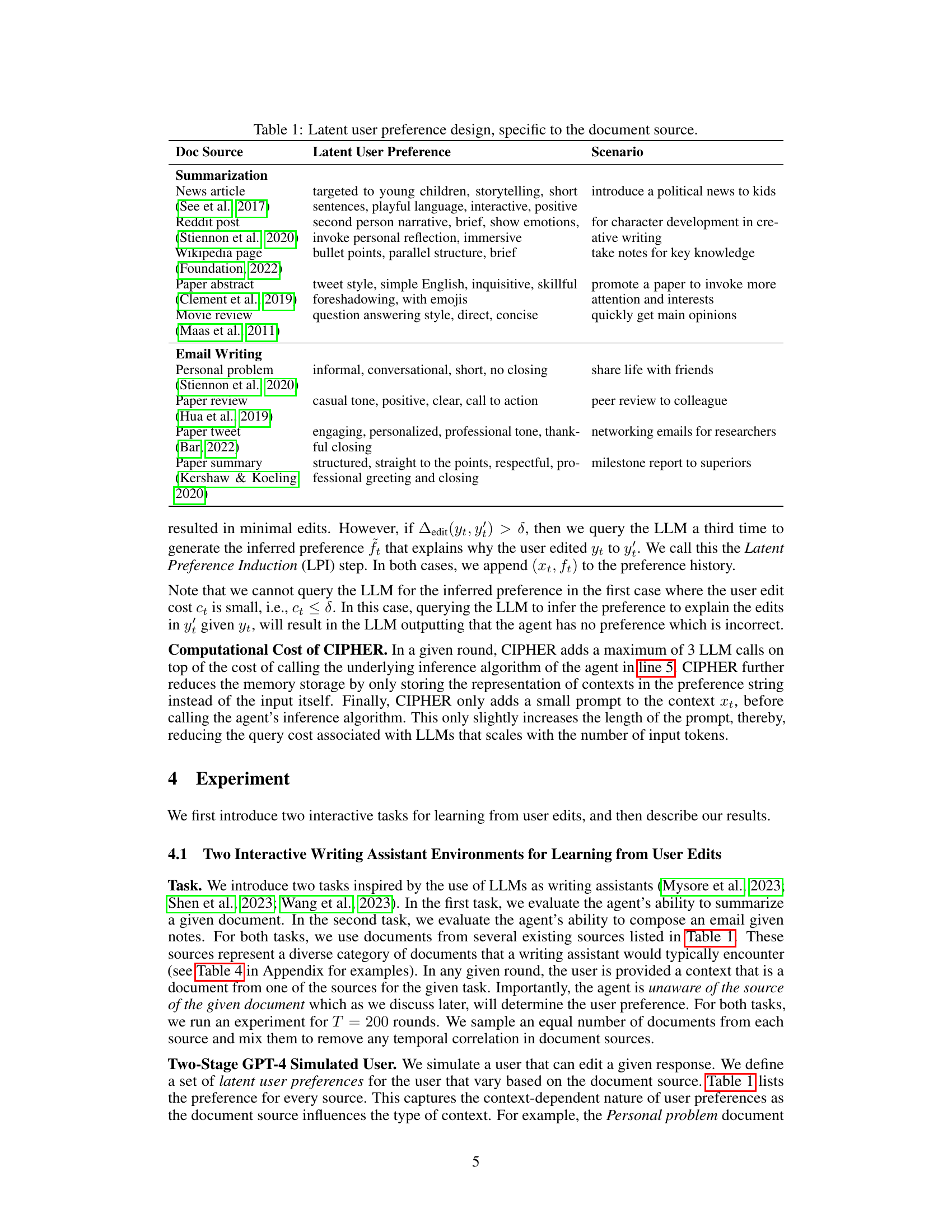

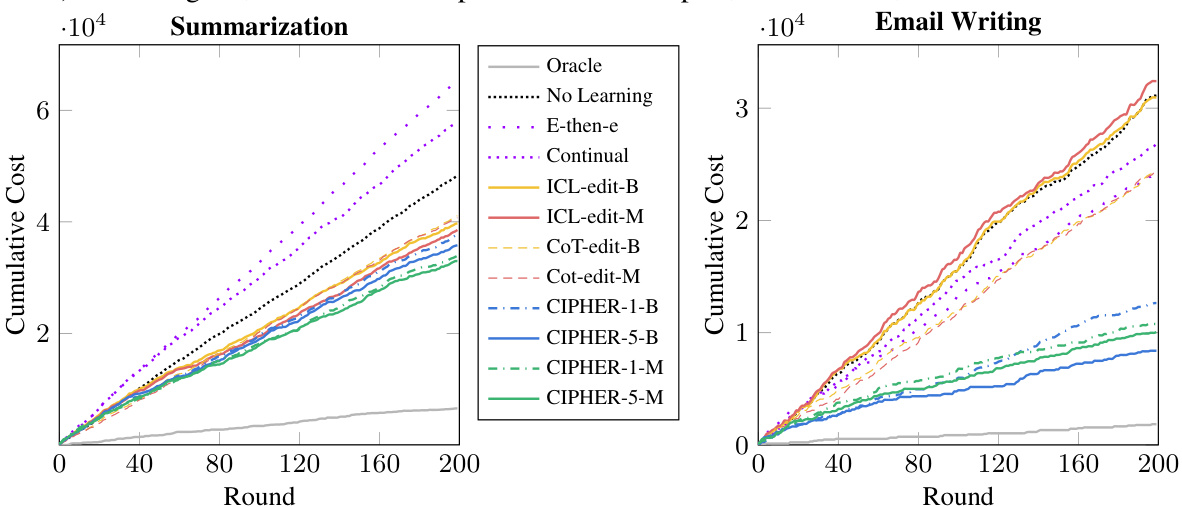

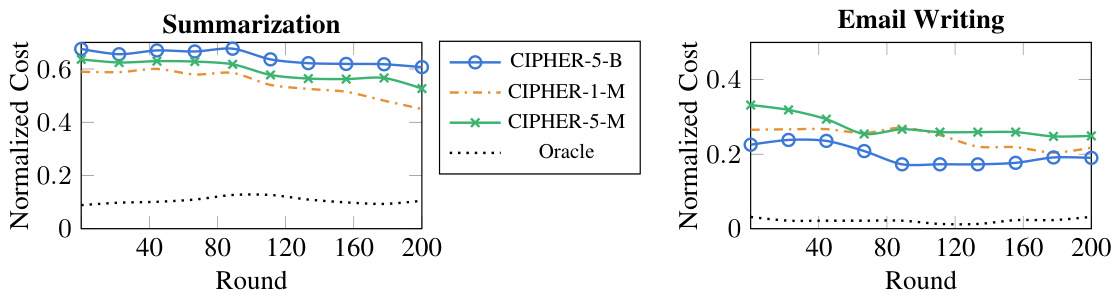

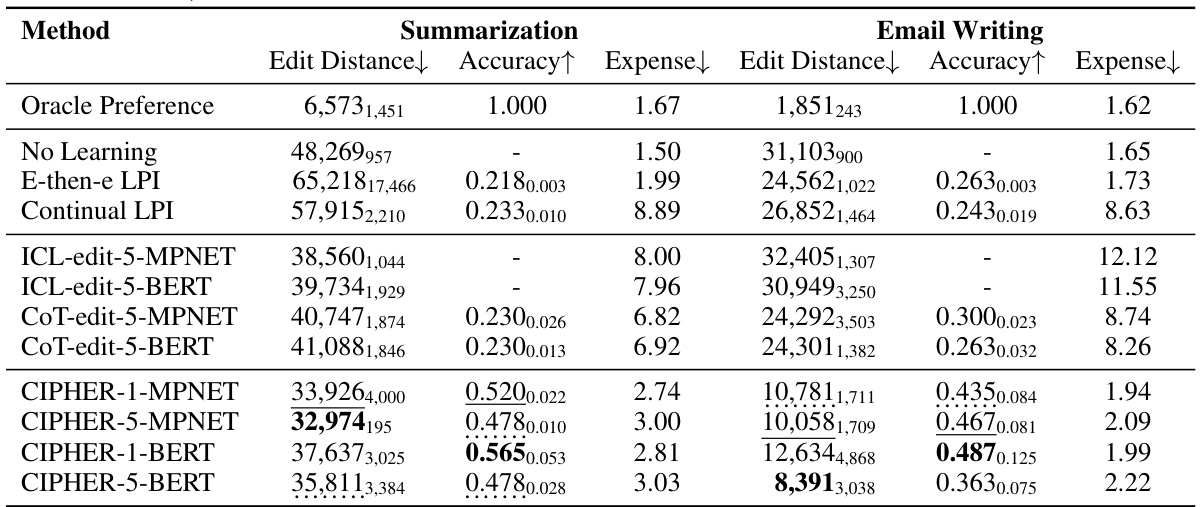

This figure shows the learning curves of different methods for two tasks: summarization and email writing. The x-axis represents the number of rounds, and the y-axis represents the cumulative cost, which is the sum of edit distances between the agent’s response and the user’s edits in each round. The curves illustrate how the cumulative cost changes over time for each method. The legend shows that different methods (no learning, explore-then-exploit, continual learning, ICL-edit, CoT-edit, and CIPHER) with variations using BERT or MPNET and different numbers of retrieved examples (k) are compared. The oracle method is shown as a baseline.

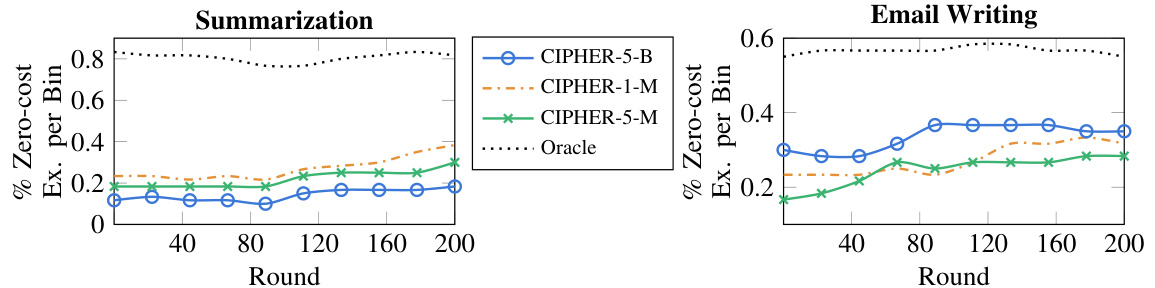

This figure shows the percentage of times CIPHER produced a response that did not require any edits from the simulated user over the course of 200 rounds of interaction. The results are binned into groups of 20 rounds to highlight trends. Separate lines are shown for different variations of CIPHER using BERT or MPNET for context embedding and retrieving either 1 or 5 nearest neighbor contexts.

This figure displays the learning curves of various methods used in the paper, plotted against the cumulative cost over time. The cumulative cost represents the total effort a user expends on editing the model’s responses. The x-axis represents the round number (representing each interaction between the user and the language model), and the y-axis shows the cumulative cost. Different lines represent different methods, with labels indicating which method (-k specifies the number of top retrieved examples, -B indicates BERT was used for context representation, and -M indicates MPNET was used). This graph visually demonstrates how the cumulative cost changes over time for each method, allowing for a comparison of their performance in terms of reducing the user’s editing burden.

More on tables

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (baselines and the proposed CIPHER) using three metrics: cumulative edit distance, accuracy, and expense (in terms of BPE tokens). The results are averaged across three runs with different random seeds for both summarization and email writing tasks. It shows the mean and standard deviation for each metric. The table highlights the best performing method in each column (excluding the oracle method) and indicates the second and third best performances.

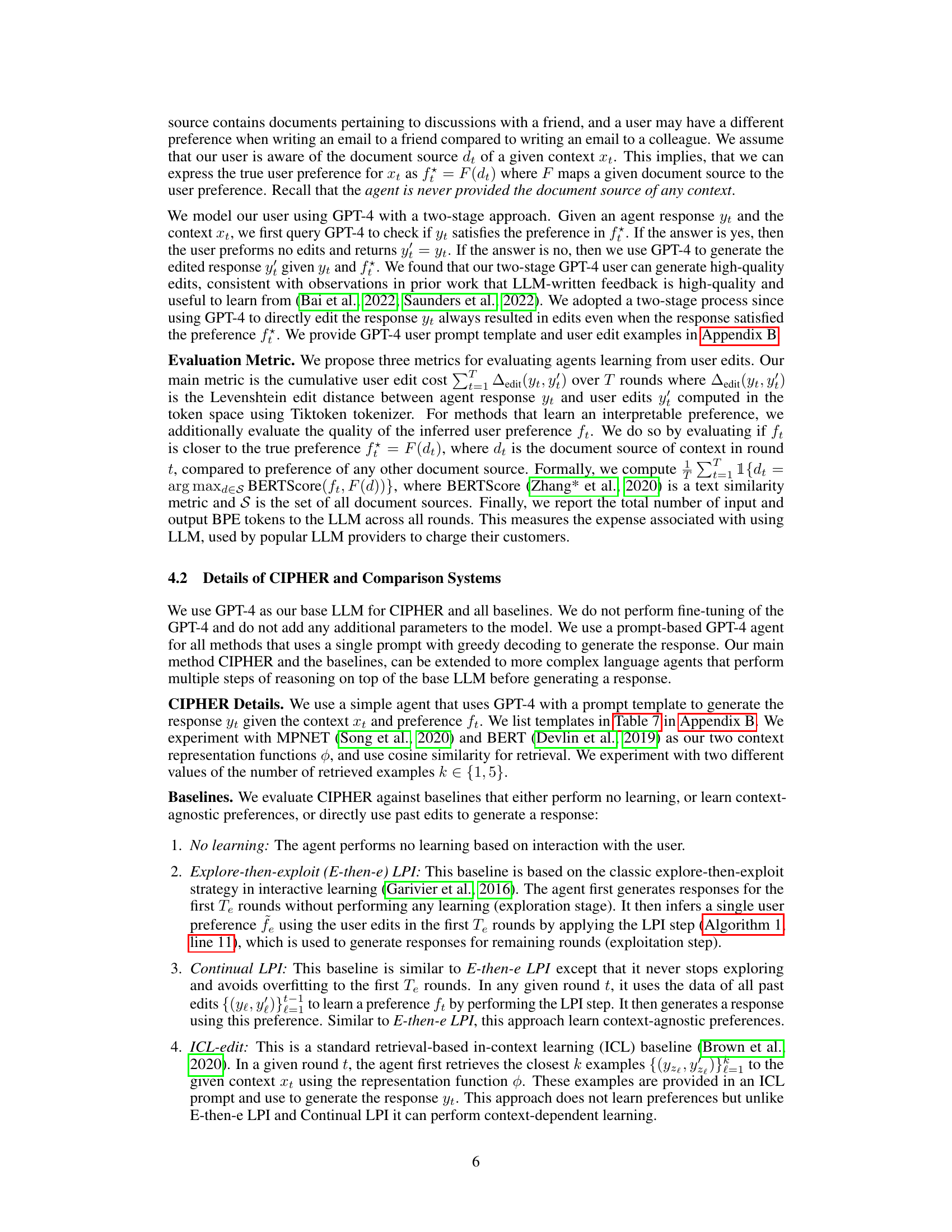

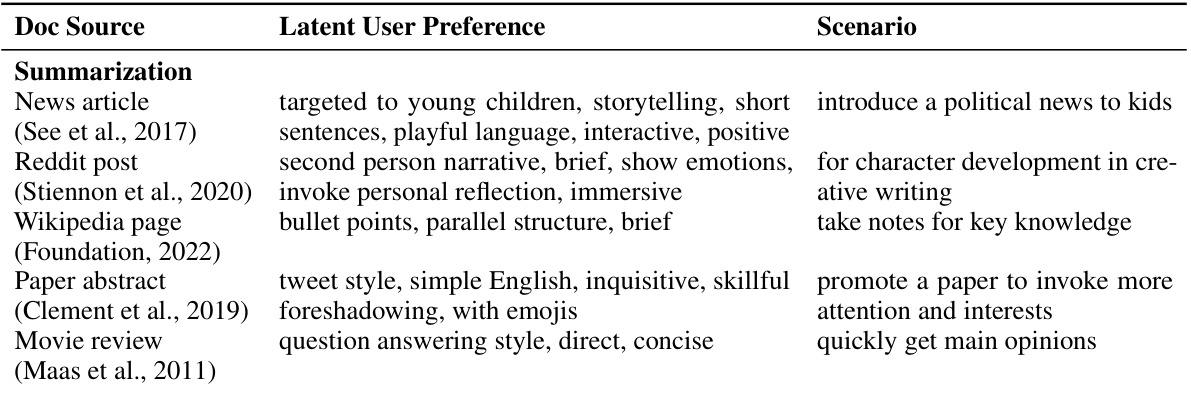

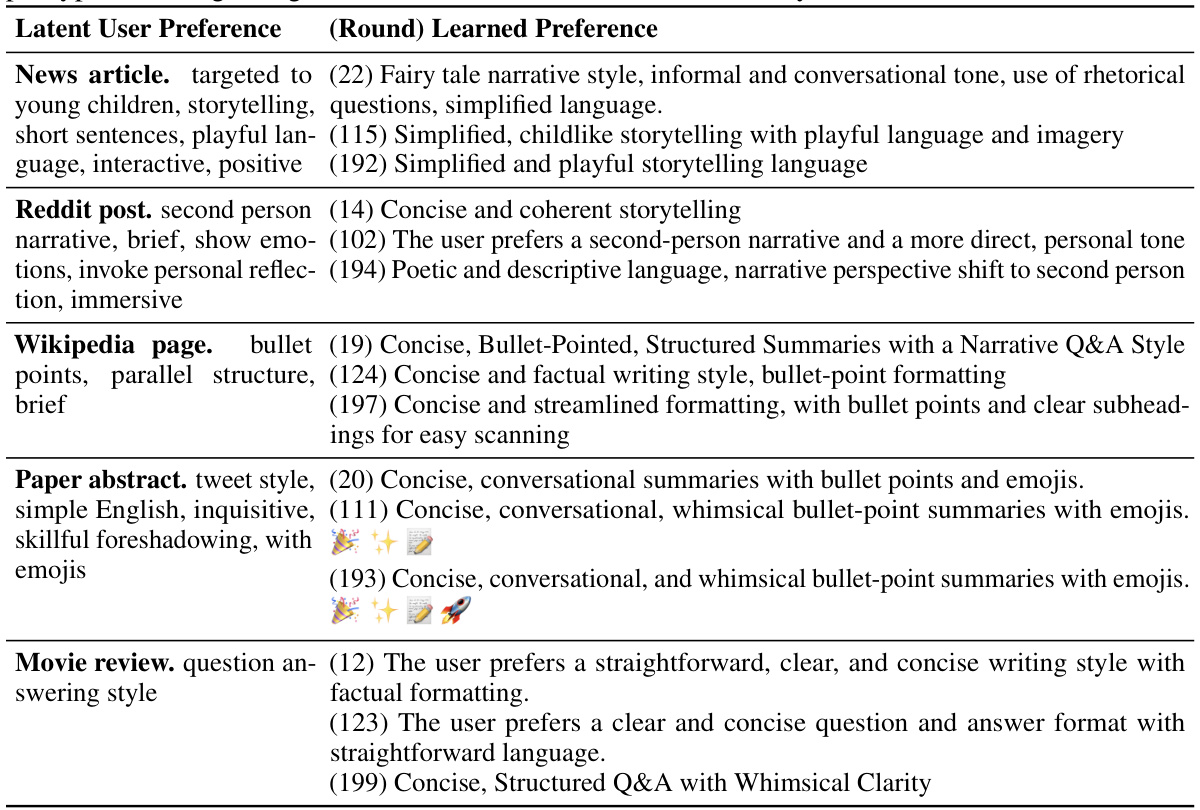

This table presents the different latent user preferences used in the experiments. Each row represents a document source (e.g., news article, Reddit post, etc.) and lists the corresponding latent preference designed for the simulated user in that context. The latent preferences capture various aspects such as style, tone, and structure of the desired output. The ‘Scenario’ column provides a brief description of how this latent user preference might be applied in a real-world scenario. For example, a news article might be summarized for young children using playful language, whereas a movie review might emphasize a concise and direct answer style.

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiment, comparing different methods (baselines and CIPHER with different configurations) across two tasks (summarization and email writing). Three key metrics are reported: cumulative edit distance (lower is better, reflecting user effort), accuracy (higher is better, indicating alignment with user preferences), and expense (lower is better, measuring the computational cost in terms of tokens processed by the LLM). The table clearly shows the performance of CIPHER in comparison to other methods, highlighting its effectiveness in achieving lower edit costs and higher accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiments. It compares the performance of several methods (including the proposed CIPHER algorithm and various baselines) on two tasks (summarization and email writing) using three metrics: cumulative edit distance, accuracy, and expense (measured as the total number of input and output tokens for the LLM). The results are averaged across three random seeds for improved statistical reliability.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for aligning LLMs based on user edits. It shows the cumulative edit distance, accuracy of learned preferences, and computational expense (measured in BPE tokens) for several baselines and the proposed CIPHER method on summarization and email writing tasks. The results are averaged over three runs with different random seeds, providing a statistical measure of performance.

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed CIPHER method and several baseline methods. The results are shown across three metrics: cumulative edit distance, classification accuracy (of inferred user preferences), and LLM expense (measured in BPE tokens). The table compares the performance of CIPHER with different hyperparameter settings (k=1 and k=5) and different context embedding methods (BERT and MPNet) to baseline methods that use no learning, learn context-agnostic preferences (E-then-e and Continual LPI), or utilize only past edits without learning user preferences (ICL-edit and CoT-edit). The oracle method, which has access to ground truth latent preferences, provides an upper bound on performance.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods (including the proposed CIPHER and several baselines) for aligning LLMs based on user edits. The comparison is done across two tasks (summarization and email writing) and three metrics: cumulative edit distance cost (lower is better), accuracy of learned preferences (higher is better), and the total expense in terms of BPE tokens (lower is better). The table shows the mean and standard deviation across three runs to provide statistical significance.

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiment, comparing different methods (including the proposed CIPHER and several baselines) across two tasks (summarization and email writing). The metrics used for comparison are cumulative edit distance (a lower value is better, indicating less user effort), accuracy of the learned preference (higher is better), and expense (measured in BPE tokens, lower is better representing lower LLM usage cost). The table provides a comprehensive comparison showing CIPHER’s superiority in terms of minimizing user edit costs while maintaining a relatively low LLM query cost.

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiments. It compares the performance of CIPHER against several baseline methods across two tasks (summarization and email writing). The metrics used are cumulative edit distance, accuracy of preference prediction, and LLM expense (measured in BPE tokens). The results are averaged across three different random seeds to provide statistical robustness. The table highlights CIPHER’s superior performance in minimizing user editing effort while maintaining a low computational cost.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for aligning LLMs based on user edits, including the proposed CIPHER method and several baselines. It shows the cumulative edit distance (a measure of user effort), classification accuracy (how well the method captures user preferences), and the computational expense (in terms of BPE tokens processed by the LLM). The results are averaged over three runs with different random seeds, and the best performing methods are highlighted.

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiments, comparing the performance of different methods on two tasks (summarization and email writing). The metrics used are cumulative edit distance, accuracy of preference prediction, and the total cost (in BPE tokens) of LLM queries. The results show CIPHER’s superior performance in minimizing edit costs and achieving comparable LLM costs, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (baselines and the proposed CIPHER method) on summarization and email writing tasks. The performance metrics include cumulative edit distance (lower is better), accuracy of preference prediction (higher is better), and LLM expense (lower is better). The table shows that CIPHER outperforms other methods, achieving the lowest edit distance while having comparable LLM costs.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods (including the proposed CIPHER and several baselines) for interactive learning from user edits. The comparison is done across two tasks (summarization and email writing) and three metrics: cumulative edit distance, accuracy of preference prediction, and LLM query cost (expense). The results show CIPHER’s superior performance in minimizing user edit cost while maintaining a relatively low LLM query cost.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (including baselines and CIPHER with different configurations) on summarization and email writing tasks. The metrics used are cumulative edit distance (lower is better), accuracy of preference prediction (higher is better), and the total expense in terms of BPE tokens (lower is better). The results are averaged over three runs with different random seeds to show statistical significance and robustness.

Full paper#