↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences is crucial but computationally expensive due to the resource-intensive fine-tuning process. Existing search-based methods either simplify the search, limiting steerability, or require training a value function which can be just as difficult as fine-tuning. This necessitates more efficient alignment strategies.

This paper introduces ‘weak-to-strong search,’ a novel test-time search algorithm that leverages smaller, already-tuned language models to guide the decoding of a larger, frozen LLM. It uses the log-probability difference between small tuned and untuned models as both reward and value to guide the search, enhancing the stronger model. Empirical results show this method effectively aligns LLMs across several tasks (sentiment generation, summarization, and instruction following), even outperforming existing methods while maintaining computational efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and efficient method for aligning large language models (LLMs) without the need for extensive fine-tuning. This is crucial because fine-tuning LLMs is computationally expensive and resource-intensive. The proposed method, called weak-to-strong search, offers a compute-efficient model up-scaling strategy and a novel instance of weak-to-strong generalization that enhances a strong model with weak test-time guidance. The approach demonstrates flexibility across diverse tasks, showing potential for broader applications and opening new avenues for future research in LLM alignment.

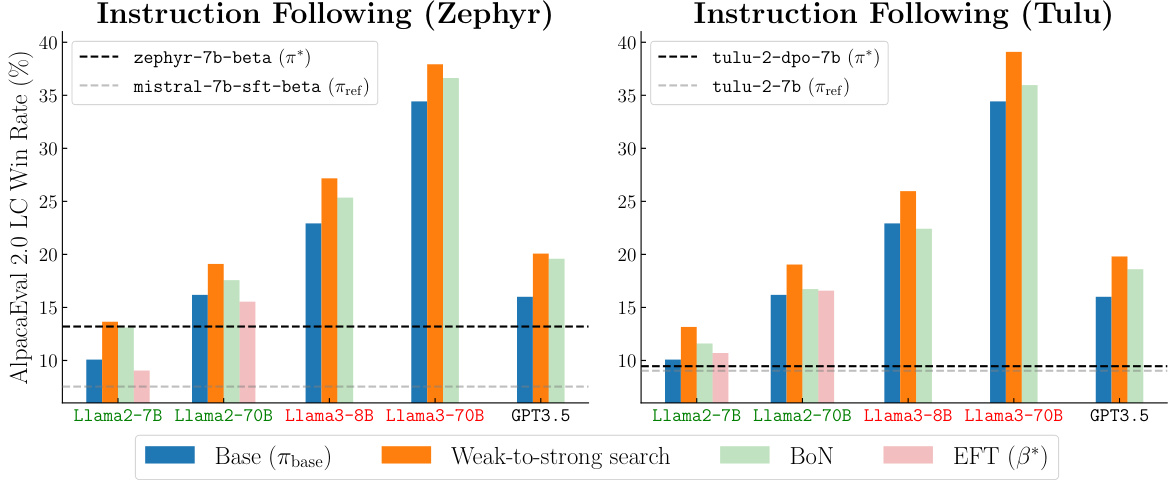

Visual Insights#

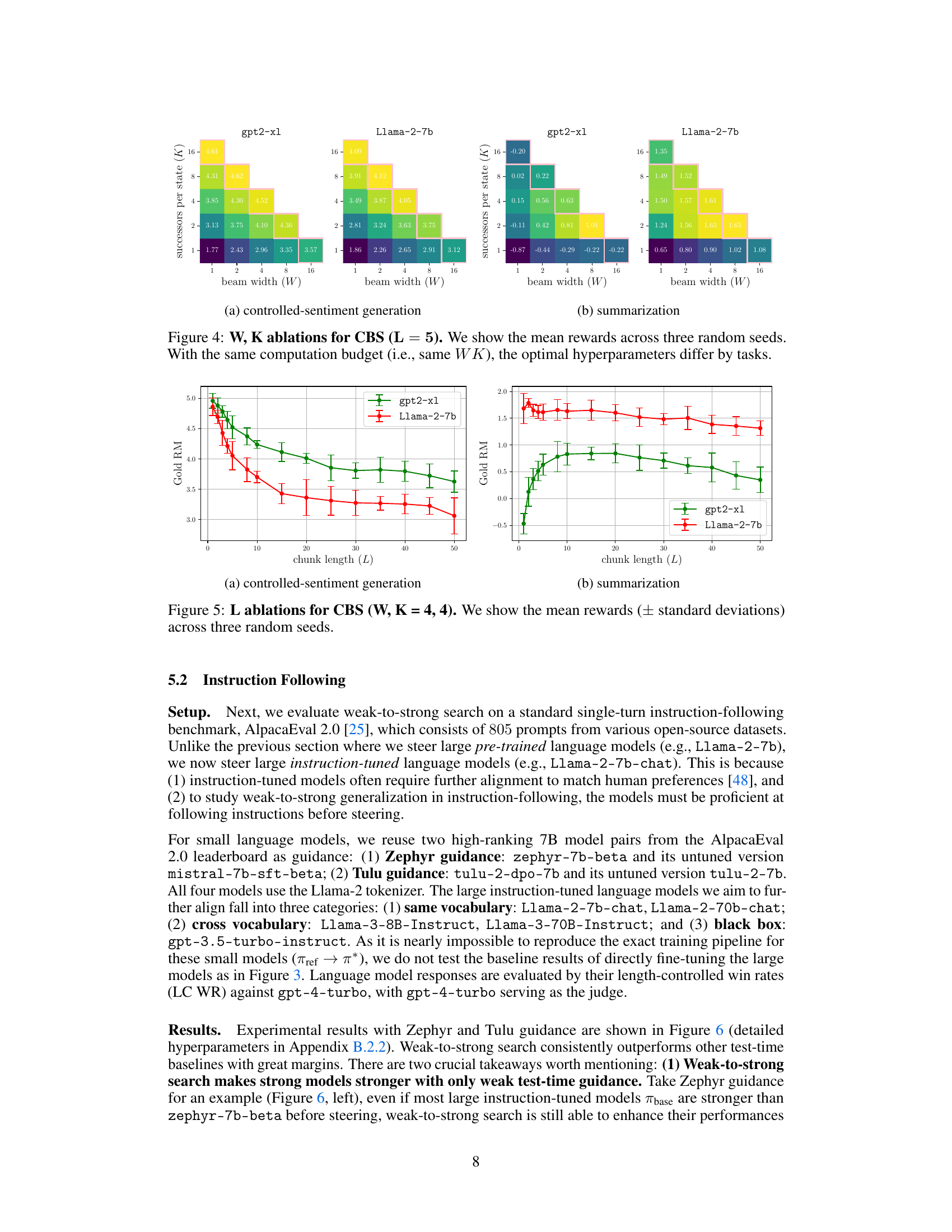

This figure shows the improvement in AlpacaEval 2.0 length-controlled win rates against GPT-4-turbo when using weak-to-strong search. The win rates are displayed for various large language models (LLMs), both with and without the weak-to-strong search method. The dashed lines represent the performance of small, tuned and untuned models used as guidance for the weak-to-strong search. The figure highlights the effectiveness of the method in improving the alignment of large language models, even when the guidance comes from relatively weak small models.

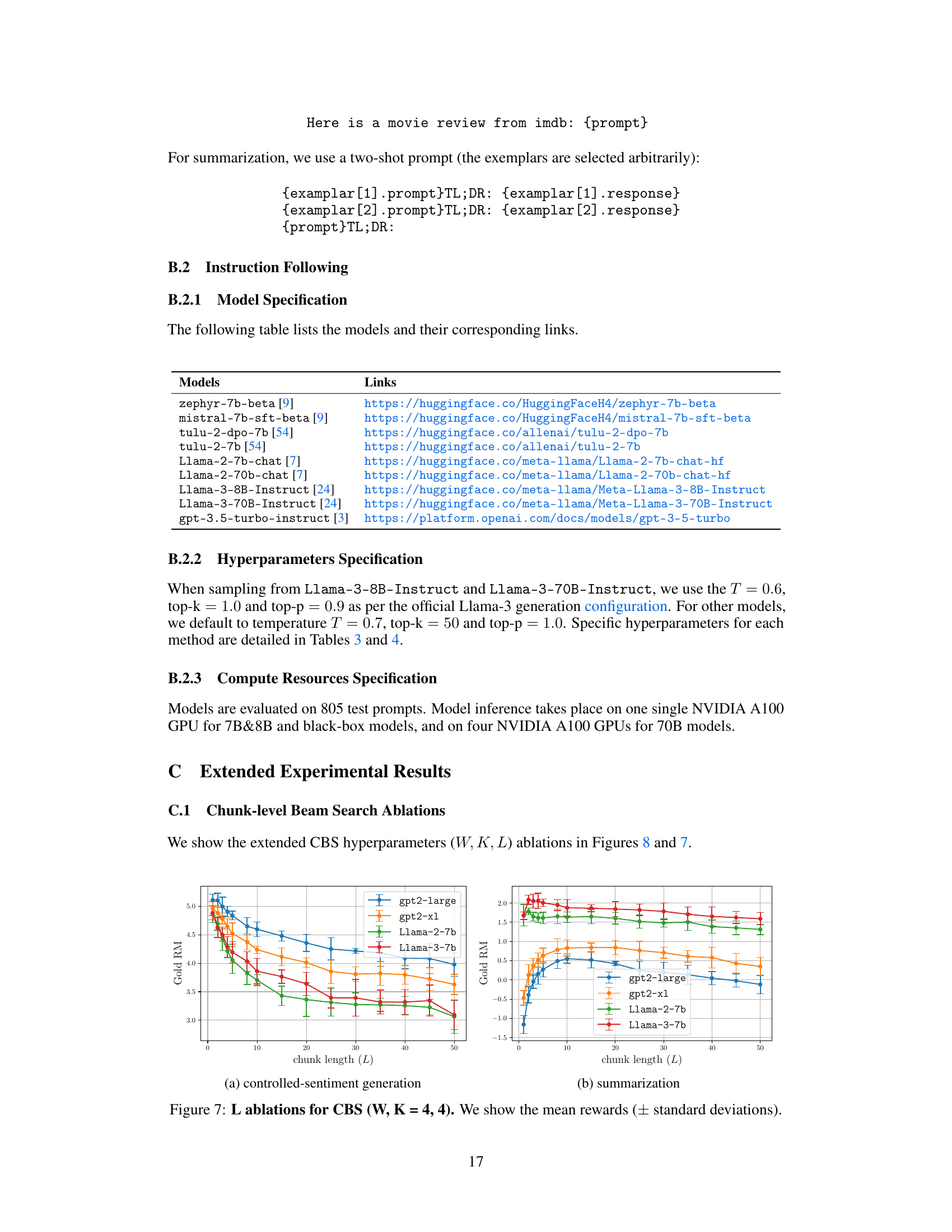

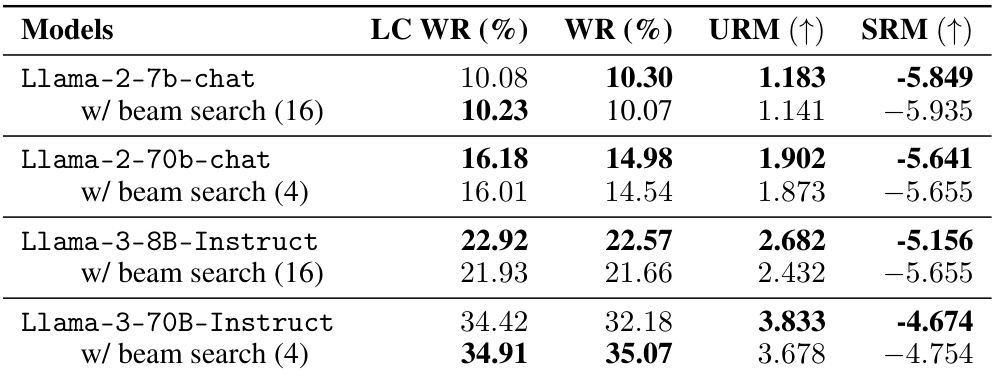

The table presents the performance of different models (Llama-2-7b-chat, Llama-2-70b-chat, Llama-3-8B-Instruct, Llama-3-70B-Instruct, gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct) on the instruction following task using Zephyr guidance. It compares the performance of the base model (regular decoding), EFT (Emulated Fine-Tuning), BoN (Best-of-N Sampling), and weak-to-strong search using several metrics: Length-controlled win rate (LC WR), Win rate (WR), UltraRM score, and SRM score. The results are categorized by vocabulary type (same and cross) and model type (black-box).

In-depth insights#

Weak-to-strong Align#

The concept of “Weak-to-strong Align” in the context of large language models (LLMs) suggests a paradigm shift in how we approach model alignment. Instead of directly fine-tuning massive LLMs, which is computationally expensive and resource-intensive, this approach leverages smaller, more easily tunable models to guide the behavior of the larger model. These smaller models act as “weak” guides, providing test-time steering, while the powerful LLM acts as the “strong” core. This strategy offers advantages in terms of computational efficiency and potentially improved generalization, since the larger model isn’t directly altered. The effectiveness hinges on the ability of the “weak” models to accurately reflect desired behaviors and provide sufficient guidance during the LLM’s inference process. Careful selection of the smaller models is crucial to ensure their guidance is relevant and impactful, maximizing the benefits of this approach.

Test-time Search#

Test-time search, in the context of aligning large language models (LLMs), presents a compelling approach to enhance model performance without the need for extensive retraining. This paradigm shifts the focus from computationally expensive pre-training or fine-tuning to efficient, test-time optimization. By cleverly leveraging smaller, already-tuned language models, the method guides the LLM’s decoding process to better align with desired outputs. The key is the utilization of a log-probability difference as a reward signal; the method searches for sequences that maximize this difference between tuned and untuned smaller models, effectively steering the larger LLM toward preferred responses. This framework offers significant computational advantages over traditional methods and shows promise in improving alignment on various tasks, suggesting a potentially impactful contribution to the field of LLM alignment.

CBS Algorithm#

The Chunk-level Beam Search (CBS) algorithm, a core component of the presented research, offers a novel approach to aligning large language models (LLMs) using small, pre-trained models. CBS cleverly frames the alignment as a test-time search, maximizing the log-probability difference between tuned and untuned small models. This avoids the computationally expensive process of directly fine-tuning the large model. The algorithm’s strength lies in its flexibility: It handles various tasks, both white-box models sharing vocabulary with the small models and black-box models where this is not the case. CBS balances reward maximization with KL-constraint minimization, ensuring alignment without over-optimization. By employing a beam search approach at the chunk level, CBS enhances steerability and efficiency, effectively using weak models to guide the stronger, larger models. The practical implications are significant: CBS functions as a compute-efficient model up-scaling strategy and as a weak-to-strong generalization technique, thus enhancing the capabilities of LLMs through strategic test-time guidance.

Empirical Gains#

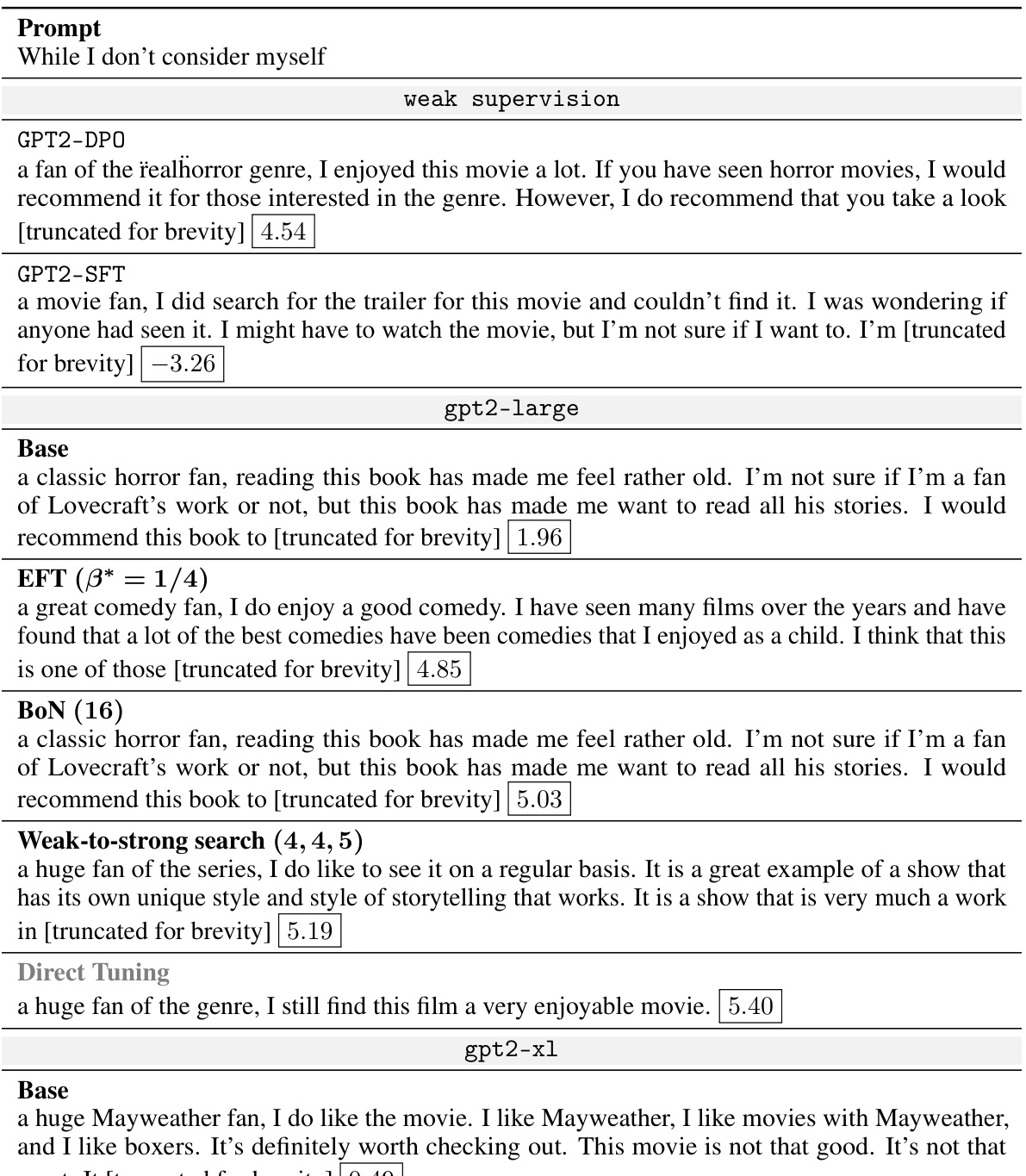

An ‘Empirical Gains’ section in a research paper would detail the practical improvements achieved by a proposed method. It would go beyond theoretical analysis, presenting concrete evidence of its effectiveness. This might involve quantitative results such as improved accuracy, efficiency, or other relevant metrics compared to existing baselines. The presentation should be clear, including detailed explanations of experimental setups, statistical significance tests, and visualizations like charts or tables. Robustness analysis is crucial; the results should demonstrate consistent gains across different datasets, parameter settings, or test conditions. The discussion should also address any limitations or potential caveats of the empirical findings, ensuring a balanced and nuanced portrayal of the method’s advantages. Qualitative analysis, such as the inspection of generated outputs, could also be incorporated to provide deeper insights, especially if the task involves subjective judgments. Overall, a strong ‘Empirical Gains’ section would provide compelling evidence of the practical impact of the research.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending weak-to-strong search to single-stage fine-tuning tasks, where a pre-trained model serves as the untuned model, would broaden applicability. Investigating the method’s failure modes in diverse scenarios and comparing its performance with other alignment methods across various tasks is crucial. Exploring its use in tasks beyond preference alignment, such as reasoning and coding, warrants investigation. Finally, further analysis of the dense reward parametrization’s benefits for reinforcement learning (RL) tuning and a deeper examination of the algorithm’s computational efficiency and scalability are also highly relevant for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

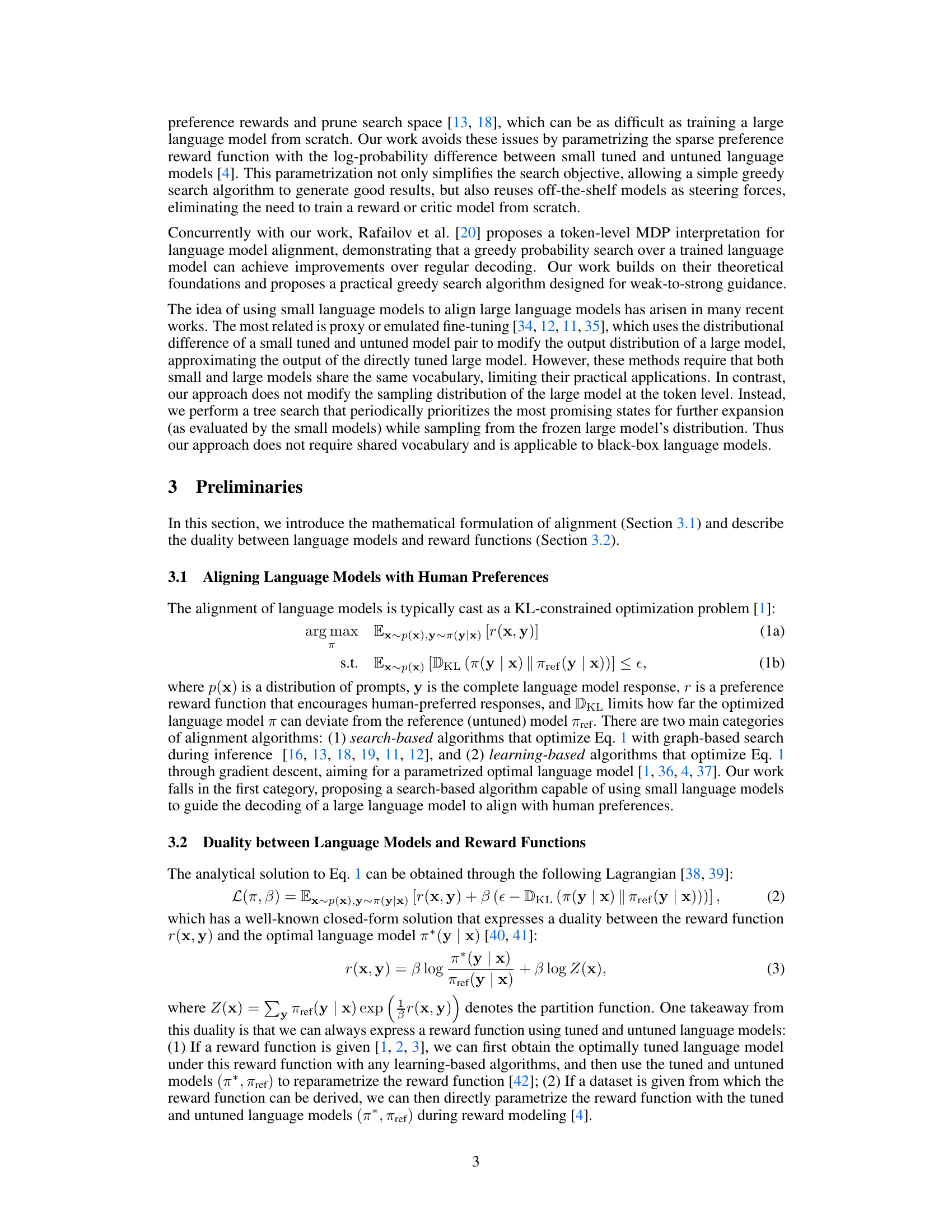

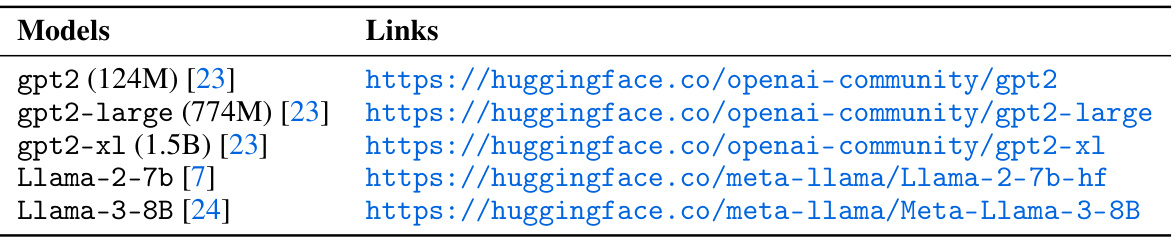

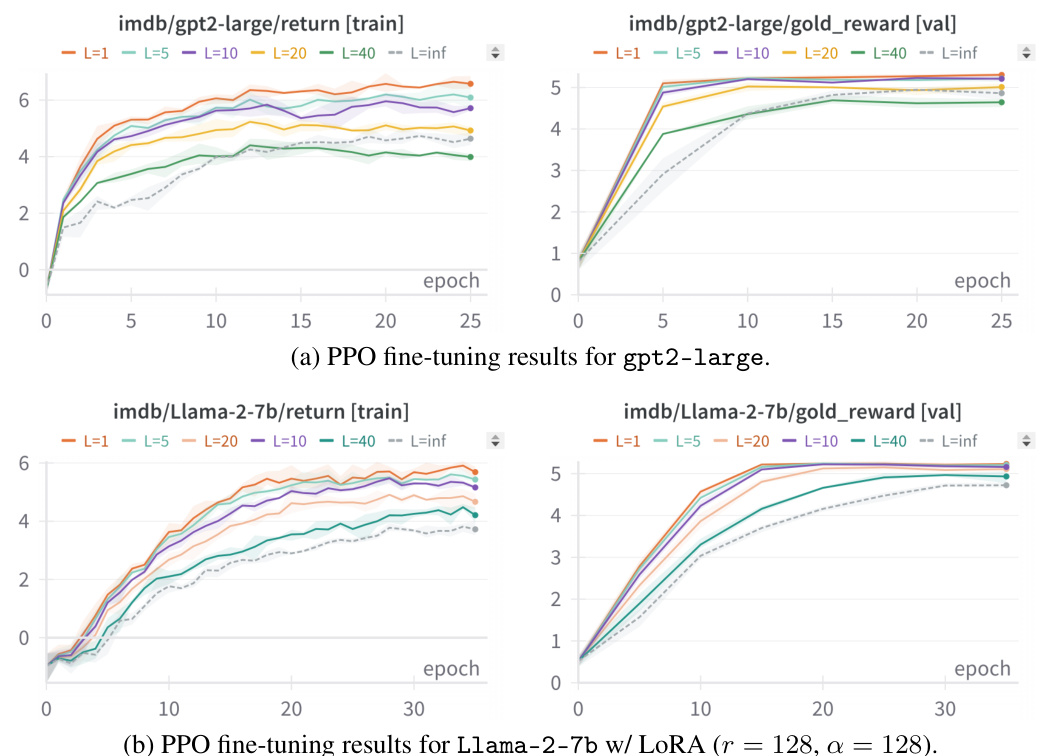

This figure illustrates the Chunk-Level Beam Search (CBS) algorithm. It shows how the algorithm maintains a hypothesis set of partial sequences (H). For each hypothesis, it samples successor chunks (YL) from the base language model. The top-W best successors, based on a scoring function using the log probability difference between a tuned and untuned small language model, are selected to expand. This process continues until a complete response is generated.

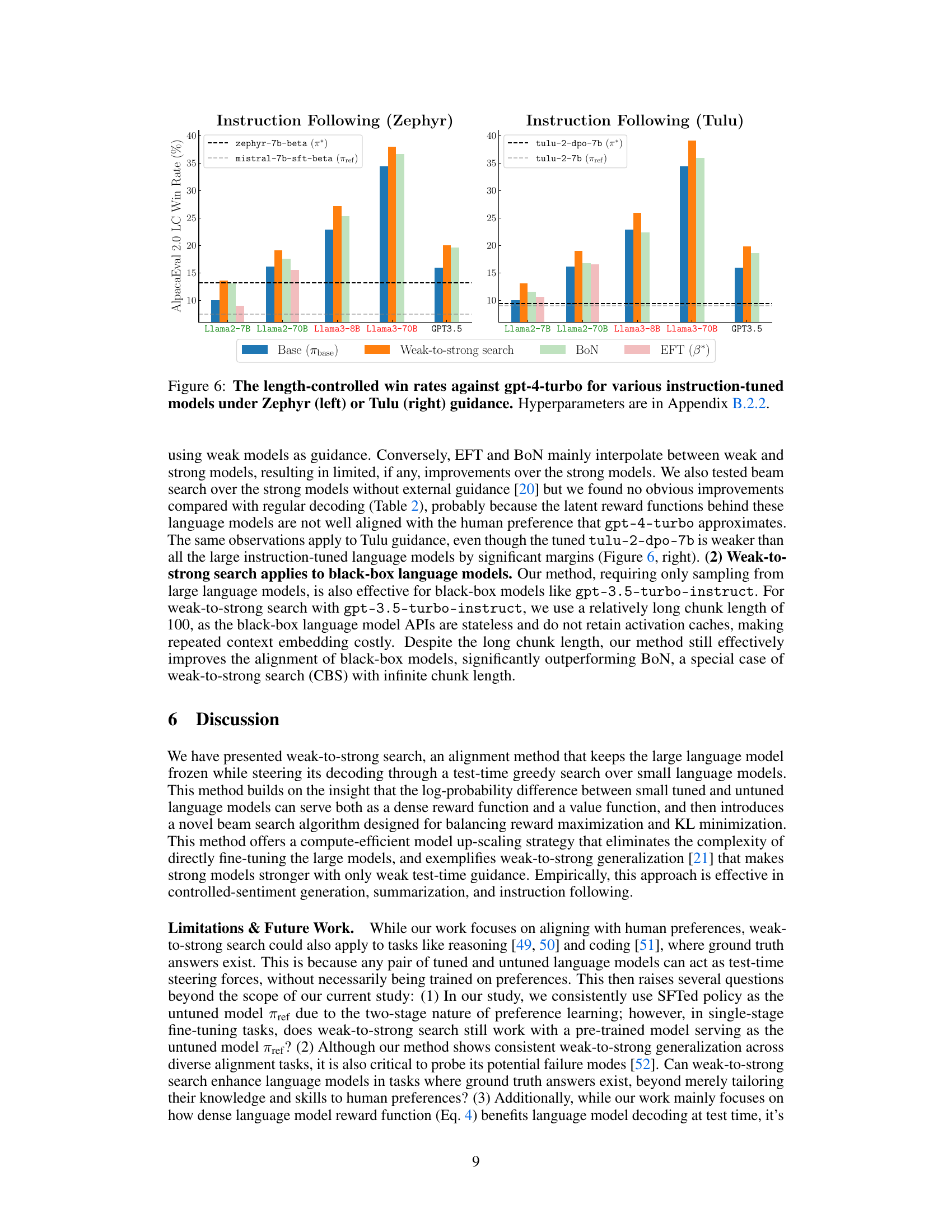

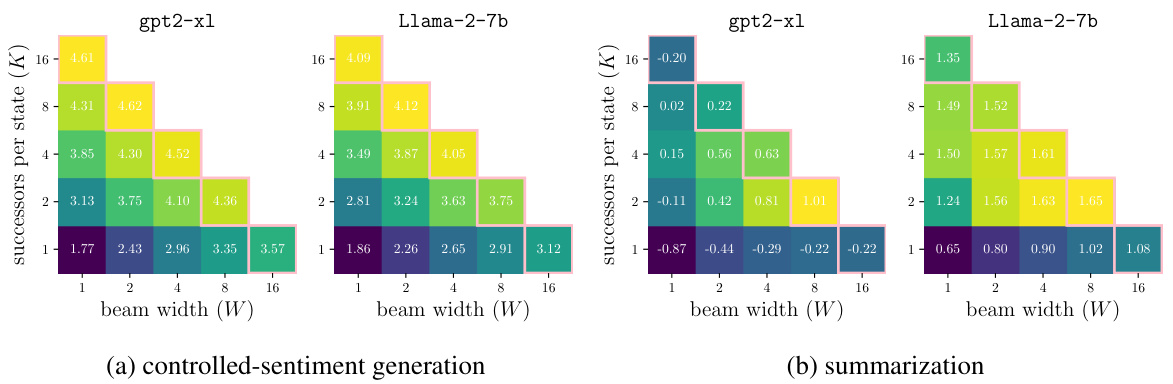

This figure compares the performance of different methods for aligning large language models using small tuned and untuned gpt2 models as guidance on two tasks: controlled-sentiment generation and summarization. The gold reward, a metric reflecting alignment with human preferences, is plotted for each method on several large models (gpt2-large, gpt2-xl, Llama2-7B, Llama3-8B). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of weak-to-strong search in improving alignment, particularly compared to baselines like BoN and EFT.

The figure shows the improvement in the alignment of large language models (LLMs) by using weak-to-strong search. The dashed lines represent the performance of small tuned and untuned models, which are used to guide the decoding process of the LLMs. The results demonstrate that the method works across various tasks (controlled sentiment generation, summarization, and instruction-following) and model architectures (white-box and black-box). The method is effective even when the guiding small models have low win rates (around 10%).

The figure shows the results of using weak-to-strong search to improve the alignment of large language models. The dashed lines represent the performance of the method using small tuned models as guidance, demonstrating improvements over baseline methods (solid bars) across various large models (Llama 2, Llama 3, GPT3.5). The results highlight the flexibility of the approach across different model architectures and vocabularies, including black-box models.

The figure shows the results of applying weak-to-strong search to several large language models. The dashed lines represent the performance improvement achieved by using the proposed weak-to-strong search method, which guides the larger models using smaller, tuned and untuned models. This demonstrates how the alignment of large language models can be improved without direct fine-tuning, and that the technique works with both white-box and black-box models (models that do or do not share the same vocabulary as the smaller guidance models). The results show improved performance on various benchmarks, particularly AlpacaEval 2.0.

The figure shows the results of using weak-to-strong search to improve the alignment of large language models. The dashed lines represent the performance gains achieved by incorporating guidance from smaller, tuned language models during test time. The figure demonstrates the method’s applicability to both white-box (models sharing vocabularies) and black-box (models with different vocabularies) large language models across multiple instruction-following benchmarks. The results are presented for instruction-tuned models from various families.

This figure shows the results of using weak-to-strong search to improve the alignment of large language models. The dashed lines represent the performance gains achieved by incorporating test-time guidance from smaller, tuned models. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach on various models, including both white-box and black-box models, with the x-axis showing different models and the y-axis showing the AlpacaEval 2.0 LC win rate (%). The key takeaway is that even small, tuned models can significantly improve larger models’ performance.

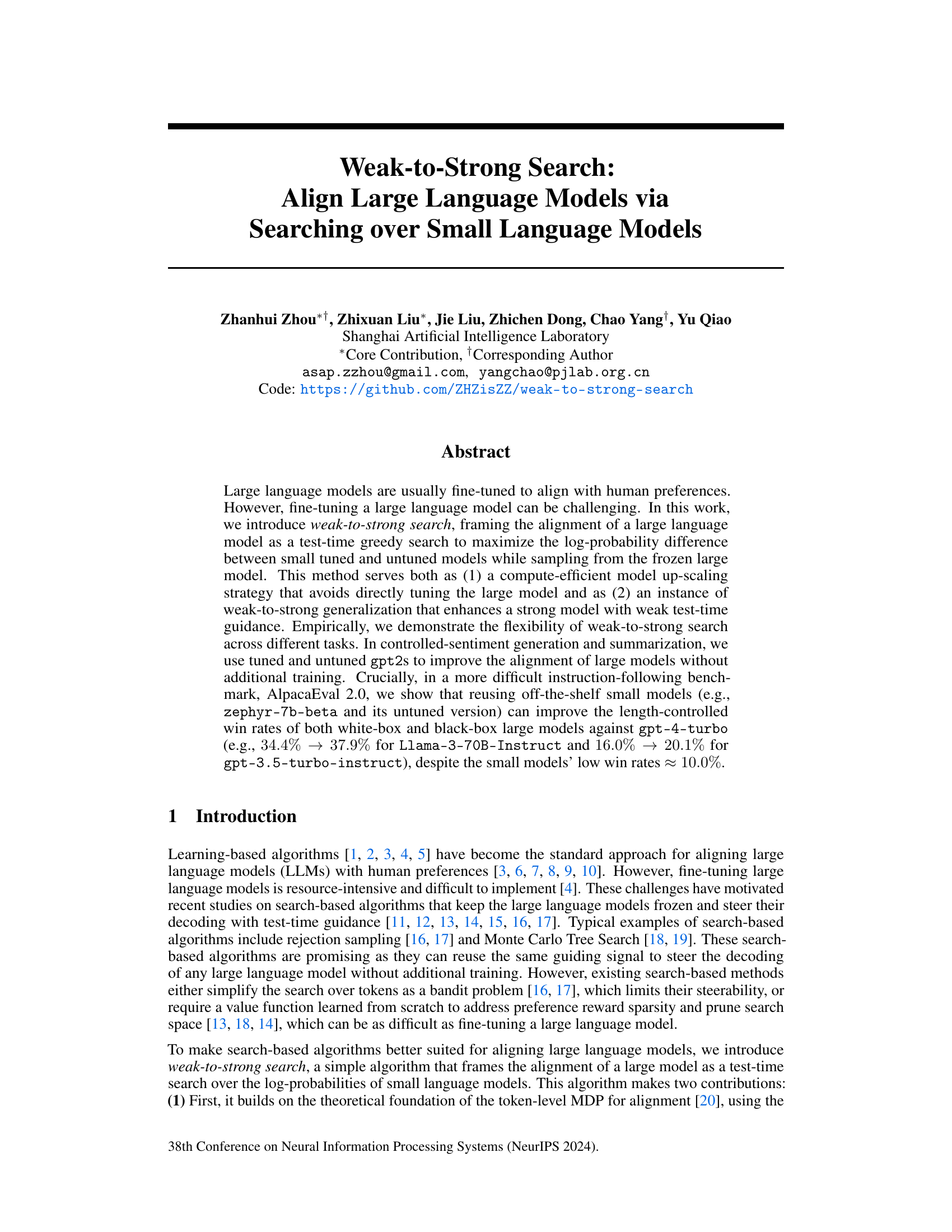

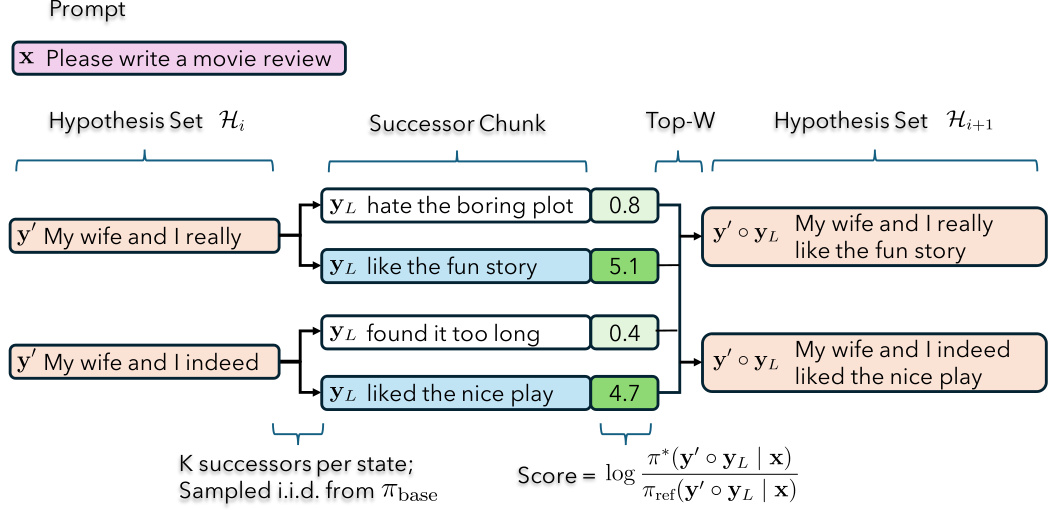

This figure shows the results of ablation studies on the hyperparameters W (beam width) and K (successors per state) of the Chunk-level Beam Search (CBS) algorithm, with a fixed chunk length L=5. The experiments were conducted on controlled-sentiment generation and summarization tasks. The plots show the mean reward across three random seeds for different combinations of W and K. Notably, while maintaining the same computational budget (WK), the optimal settings for W and K vary depending on the task, indicating a task-specific optimal balance between exploring multiple hypotheses and focusing computational resources on promising ones.

The figure displays the results of using weak-to-strong search to improve the alignment of large language models. It shows that using smaller, already tuned language models as test-time guidance improves the performance of larger models across different tasks, even when the vocabularies don’t match and the models are treated as ‘black boxes’. The dashed lines represent the small models, while the solid bars represent the large models before and after the application of the weak-to-strong search method. The figure highlights the improvement in AlpacaEval 2.0 length-controlled win rates against GPT-4-turbo.

More on tables

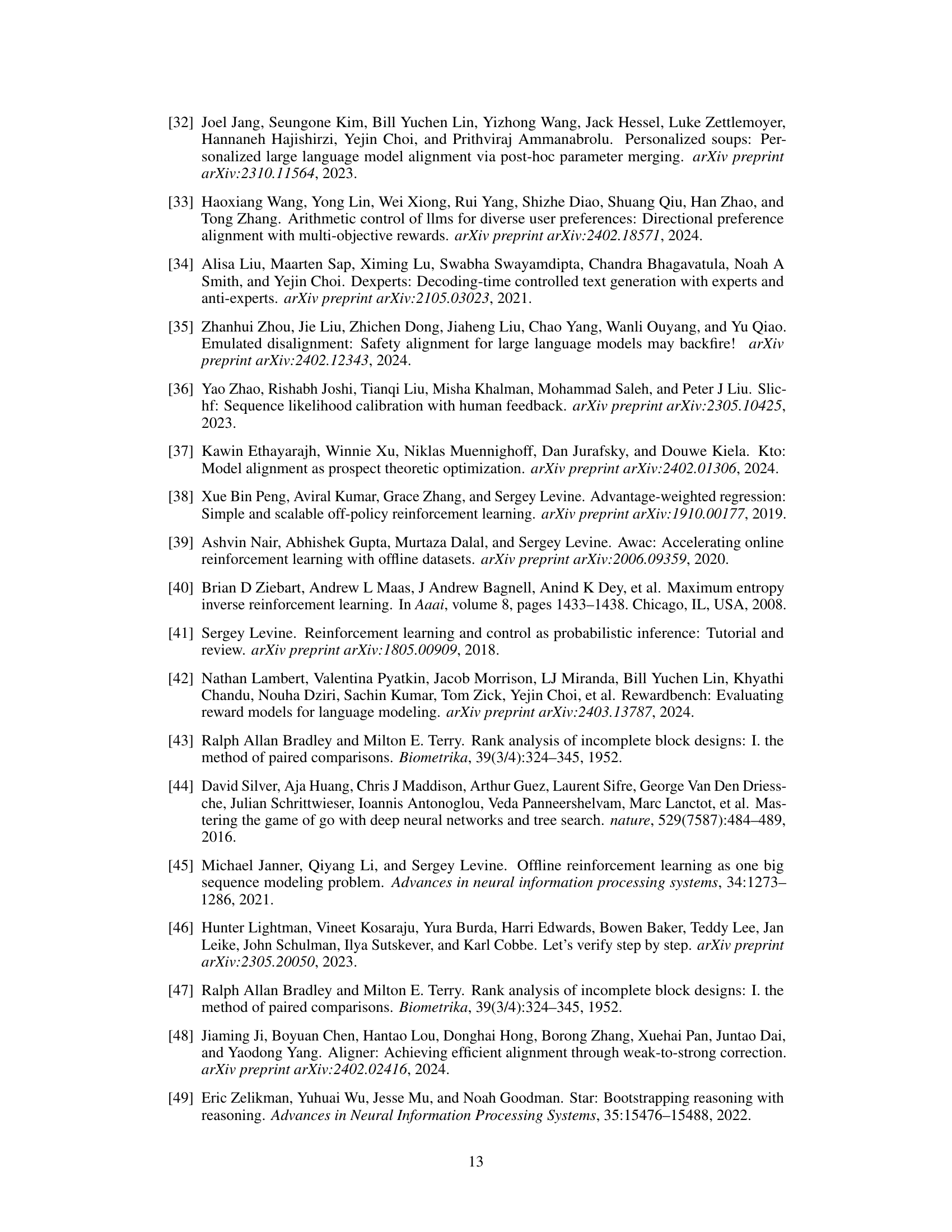

This table presents the results of instruction-following experiments using the Zephyr guidance. It compares the performance of several methods: a baseline (Base), Emulated Fine-Tuning (EFT), Best-of-N Sampling (BON), and Weak-to-Strong Search (CBS). The table shows length-controlled win rates (LC WR) and raw win rates (WR) against gpt-4-turbo, as well as scores from two other reward models (UltraRM-13b and Starling-RM-34B). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of Weak-to-Strong Search in improving the performance of large language models.

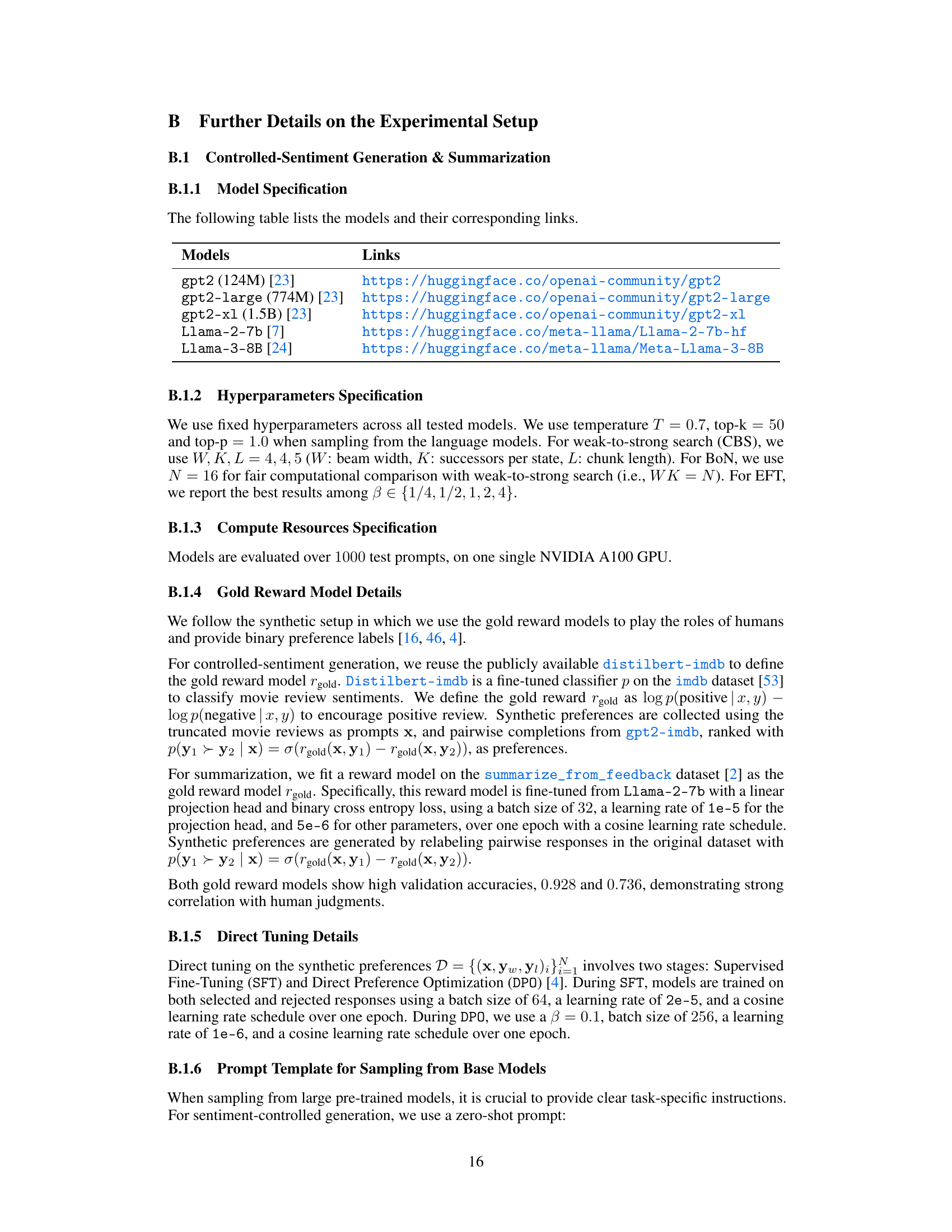

This table presents the results of instruction following experiments using different large language models. The baseline is regular decoding without any external guidance. Then, the performance of vanilla beam search (beam width =16) is tested and compared. Finally, weak-to-strong search is applied to see if it improves the performance. The results are measured by length-controlled win rates (LC WR) and raw win rates (WR) against GPT-4-turbo. Additionally, two other reward models, UltraRM-13b and Starling-RM-34B, are used for evaluating the model responses.

This table presents the results of instruction-following experiments using the Zephyr guidance. It compares several methods, including weak-to-strong search, against baselines (regular decoding, best-of-N sampling, and emulated fine-tuning) on various instruction-tuned language models. The metrics used are length-controlled win rate (LC WR), raw win rate (WR), and scores from two reward models (UltraRM-13b and Starling-RM-34B). The table is categorized by whether the models use the same or a different vocabulary compared to the small guidance models and whether the large model is a black box model.

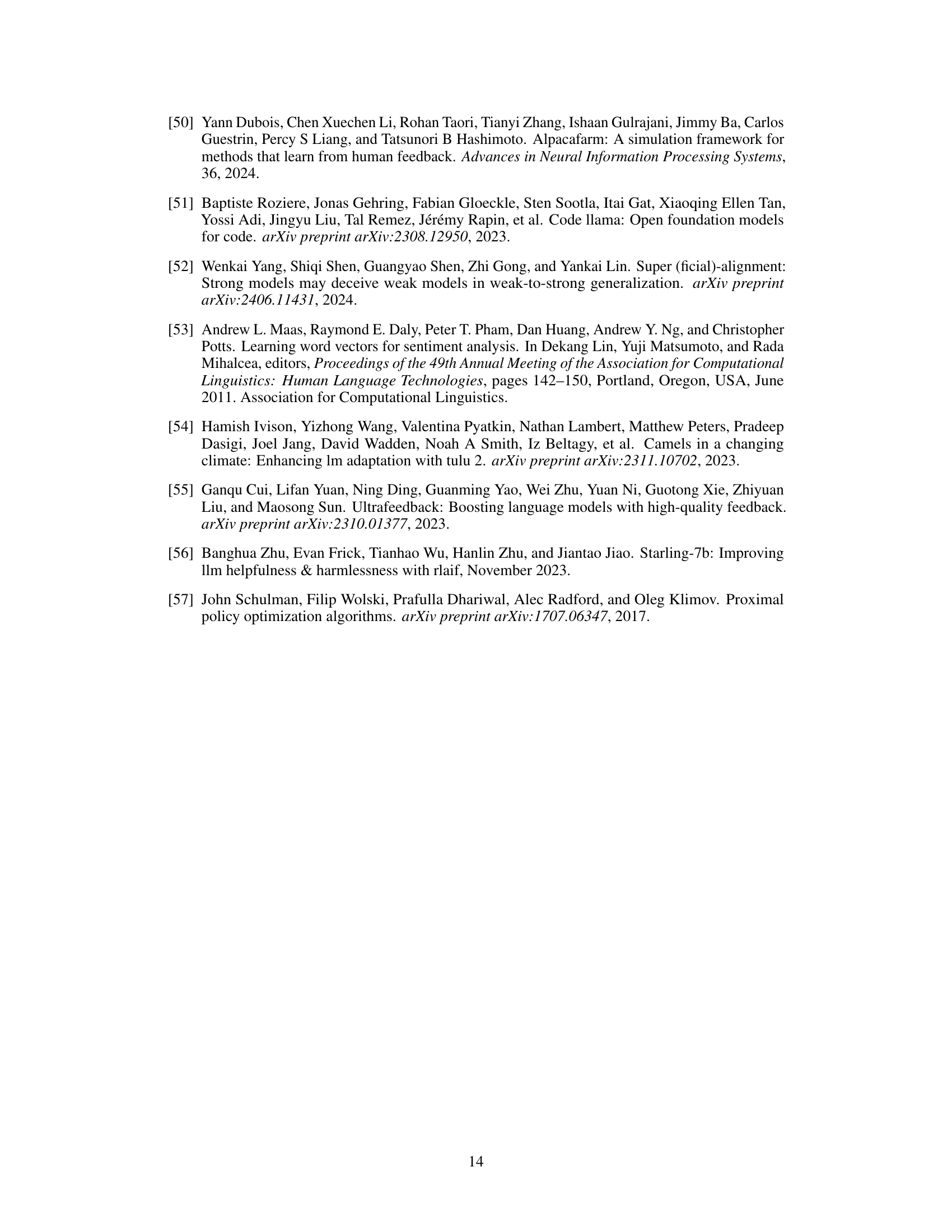

This table presents the results of instruction-following experiments using the Tulu guidance. It compares different methods’ performance on various instruction-tuned large language models. The metrics used are length-controlled win rates (LC WR), raw win rates (WR), UltraRM scores, and Starling-RM scores. The table highlights how weak-to-strong search enhances the performance of large models even when using weaker small models as guidance.

This table presents the results of instruction-following experiments using the Zephyr guidance. It compares the performance of several methods, including weak-to-strong search, against baselines such as regular decoding, Best-of-N sampling and Emulated Fine-Tuning, in terms of length-controlled win rates (LC WR) and raw win rates (WR) against GPT-4-turbo. Additionally, it includes scores from two reward models, UltraRM-13b and Starling-RM-34B. The table is categorized by whether the models use the same vocabulary or different vocabularies as the small models used for guidance.

This table presents the gold reward achieved by different large pre-trained language models when steered using small tuned and untuned GPT-2 models. It compares the performance of weak-to-strong search against baselines like Best-of-N sampling and Emulated Fine-Tuning. The results are averaged over three random seeds and show the mean reward with standard deviation.

This table presents the results of instruction following experiments using the Zephyr guidance. It compares the performance of several methods: Base (regular decoding), EFT (Emulated Fine-Tuning), BoN (Best-of-N Sampling), and Weak-to-strong search (the proposed method). The performance is measured using Length-controlled Win Rate (LC WR), Win Rate (WR), UltraRM score, and Starling-RM score. The table is divided into sections based on the vocabulary of the models (same vocabulary, cross vocabulary, and black box) to show the method’s adaptability.

This table presents the results of instruction-following experiments using the Zephyr guidance. It compares several methods, including weak-to-strong search, against baselines (regular decoding, Best-of-N sampling, and Emulated Fine-Tuning). The evaluation metrics include length-controlled win rates (LC WR), raw win rates (WR), and scores from two reward models (UltraRM-13B and Starling-RM-34B). The table highlights the performance improvement achieved by weak-to-strong search across various instruction-tuned language models.

This table presents the results of instruction following experiments using different methods. It compares the performance of vanilla beam search (without external guidance) against other methods, such as Weak-to-strong search, EFT, and BoN, in terms of length-controlled win rates (LC WR), raw win rates (WR), and scores from two reward models (UltraRM and Starling-RM). The results show that vanilla beam search offers only limited improvement over regular decoding.

Full paper#