↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The brain’s ability to encode spatial information about multiple agents remains largely mysterious. While we understand how brain regions, like the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC), represent an individual’s spatial navigation, integrating the trajectories of multiple agents in this process poses significant challenges. This research seeks to understand how the brain performs such computations and what neural representations support it.

This paper utilizes recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to model path integration in both single-agent and dual-agent scenarios. The researchers found significant differences between the RNNs trained on these two types of tasks. Specifically, RNNs trained on dual-agent tasks exhibited weaker grid cell responses (spatial tuning) and stronger border and band cell responses. Additionally, they found a new tuning mechanism in these models: the encoding of relative positions of the two agents. These results offer valuable insights into the computations supporting spatial navigation, with testable predictions for future neurophysiological studies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between single-agent and multi-agent spatial navigation studies, which is increasingly important for robotics and AI. Its findings challenge existing theories of how the brain represents space, providing testable predictions that can shape future neurophysiological experiments. The study also opens exciting new directions for research in multi-agent systems and machine learning, particularly concerning how to enhance the navigation capabilities of autonomous agents in complex, dynamic environments.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the RNN model used for single-agent path integration. Panel A shows the path integration task, where an agent moves through a 2D environment. Panel B presents the RNN architecture, detailing the input layer receiving movement direction and speed, a recurrent layer processing the information, and an output layer representing place cell activations. Finally, panel C displays example ground truth place cell activations used as training targets.

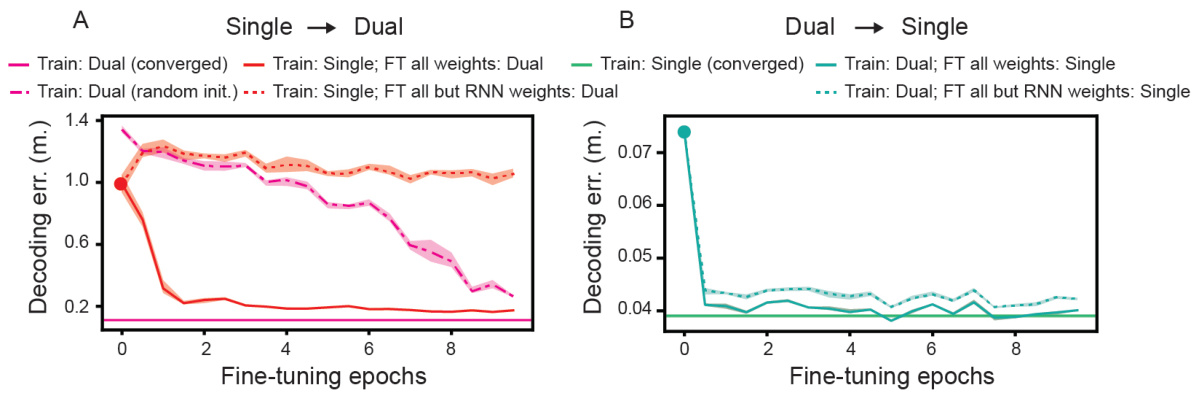

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training recurrent neural networks (RNNs) on single and dual agent path integration tasks. Most parameters are identical to those from previous work by Sorscher et al. [29], with a few key modifications highlighted in bold for dual agent training. The table provides a complete and clear overview of the settings used in the experiments reported in the paper, ensuring reproducibility of the results.

In-depth insights#

Multi-agent Path Int.#

The section on ‘Multi-agent Path Int.’ delves into the complex problem of how agents navigate environments while considering the actions and positions of other agents. The authors hypothesize that the brain’s medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) plays a crucial role, extending beyond its established function in single-agent path integration. They introduce a recurrent neural network (RNN) model to simulate this process, demonstrating how representations differ in multi-agent settings. Key findings reveal weaker grid cell responses but stronger border cell activity, suggesting a shift towards representing relative agent positions rather than absolute locations. This highlights the flexibility and adaptability of neural computations in multi-agent scenarios, and the RNN model provides a valuable tool for investigating these complex interactions. Further research directions are suggested, emphasizing the need for empirical validation through neurophysiological experiments.

RNN Model Analysis#

Analyzing RNN models for multi-agent path integration reveals key differences compared to single-agent models. Individual unit-level analysis shows weaker grid cell responses, but stronger border and band cell activity, suggesting a shift in representational emphasis. Population-level analysis using topological data analysis reveals that the RNNs trained on multi-agent data lack the continuous attractor network dynamics observed in single-agent models, pointing towards fundamentally different computational mechanisms. Further investigation into the emergence of relative space tuning in multi-agent RNNs offers valuable insight into the flexible coding strategies of the brain in complex spatial environments. Ablation studies confirm the robustness and distributed nature of the representations, emphasizing the importance of understanding the interplay between individual unit properties and network-level dynamics.

Relative Space Tuning#

The concept of ‘Relative Space Tuning’ in the context of multi-agent spatial navigation within recurrent neural networks (RNNs) suggests that the RNNs develop the ability to represent spatial information not just from an absolute, allocentric frame of reference, but also relative to the positions of other agents. This relative encoding, distinct from the traditional grid-like representations often associated with spatial navigation, indicates that the RNNs learn a more flexible and adaptable spatial understanding when multiple agents interact. This adaptation has significant implications. By focusing on relative positions, the RNNs potentially reduce computational costs and improve the robustness of their spatial representations in complex, dynamic environments. The emergence of this relative frame of reference is a key finding, suggesting a shift away from purely egocentric or allocentric systems. Further investigations are needed to confirm these neural network findings and explore their implications for biological systems performing multi-agent navigation.

Population Dynamics#

Analyzing population dynamics within the context of a research paper focusing on recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their application to multi-agent path integration reveals crucial insights into network behavior. The study likely employs techniques like topological data analysis (TDA) to characterize the high-dimensional activity patterns of the RNN’s neuronal populations. This approach could involve computing persistent homology to identify topological features (e.g., loops, cavities) in the network’s activation manifold, offering insights into the network’s intrinsic organization and its response to different input scenarios (single vs. multi-agent). The comparison between single-agent and multi-agent RNN population dynamics is key. Differences in topological features could suggest that incorporating information about multiple agents significantly alters the network’s internal representation of space, potentially shifting from a toroidal attractor structure (characteristic of single-agent spatial navigation) to a more complex, distributed representation suited for multi-agent interactions. The analysis may further include measures of dynamic similarity to compare the temporal evolution of the network’s activity, potentially revealing differences in the stability or robustness of the network in the two scenarios. Overall, the findings on population dynamics should provide a deeper understanding of how RNNs learn and represent complex spatial information, with implications for both neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper suggests several promising avenues for future work. Extending the RNN model to handle more than two agents would be a natural progression, increasing the complexity and realism of the simulated navigation scenarios. Investigating the integration of reinforcement learning with these RNNs could be particularly insightful, allowing the exploration of how learned representations support more sophisticated decision making in complex multi-agent environments. The authors also suggest exploring the fundamental principles underlying path integration in multi-agent scenarios from a theoretical standpoint, moving beyond empirical models. Finally, they highlight the potential for bridging the gap between theoretical models and experimental neuroscience, suggesting future studies could compare the RNN model’s predictions to actual neural recordings in MEC, potentially verifying their hypotheses about the neural computations involved in multi-agent spatial navigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

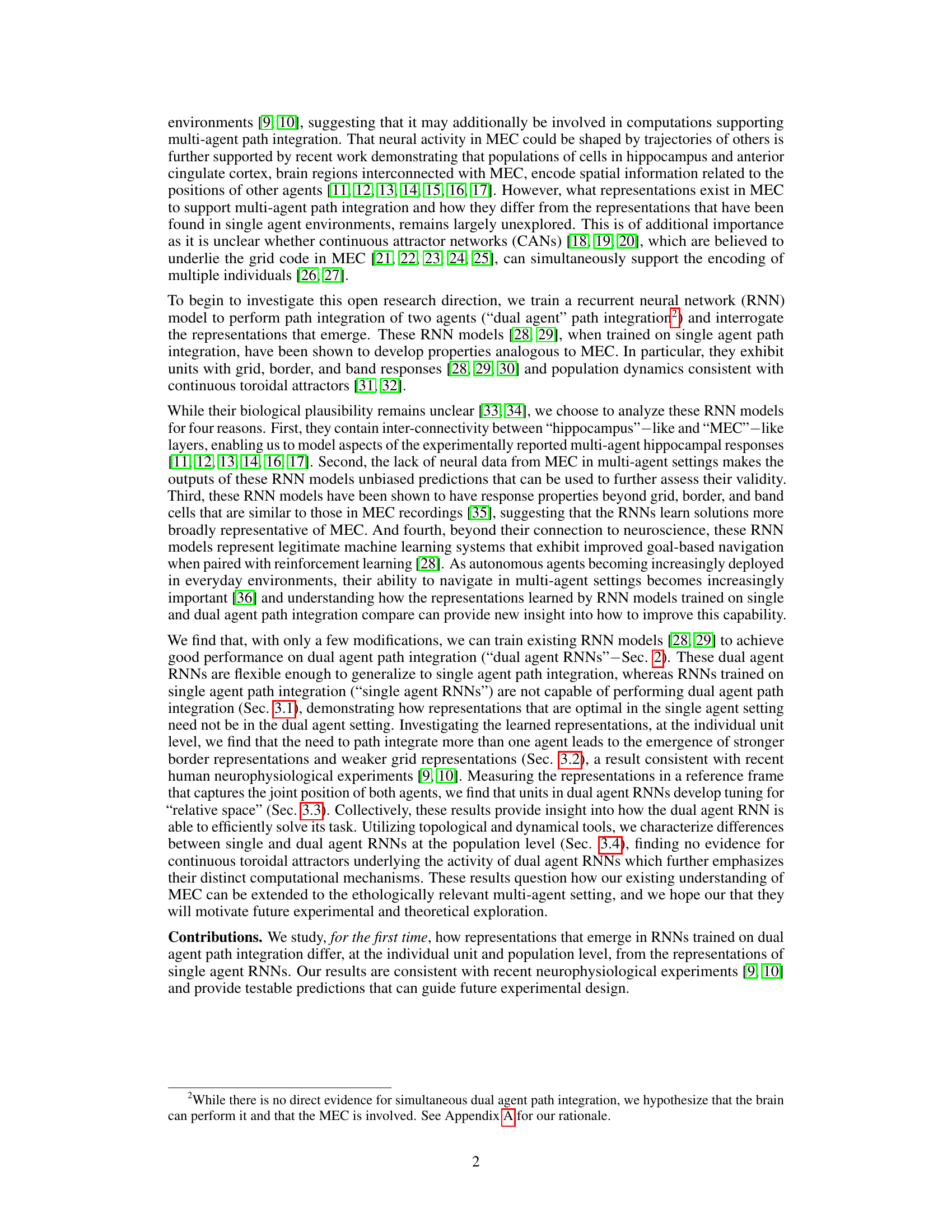

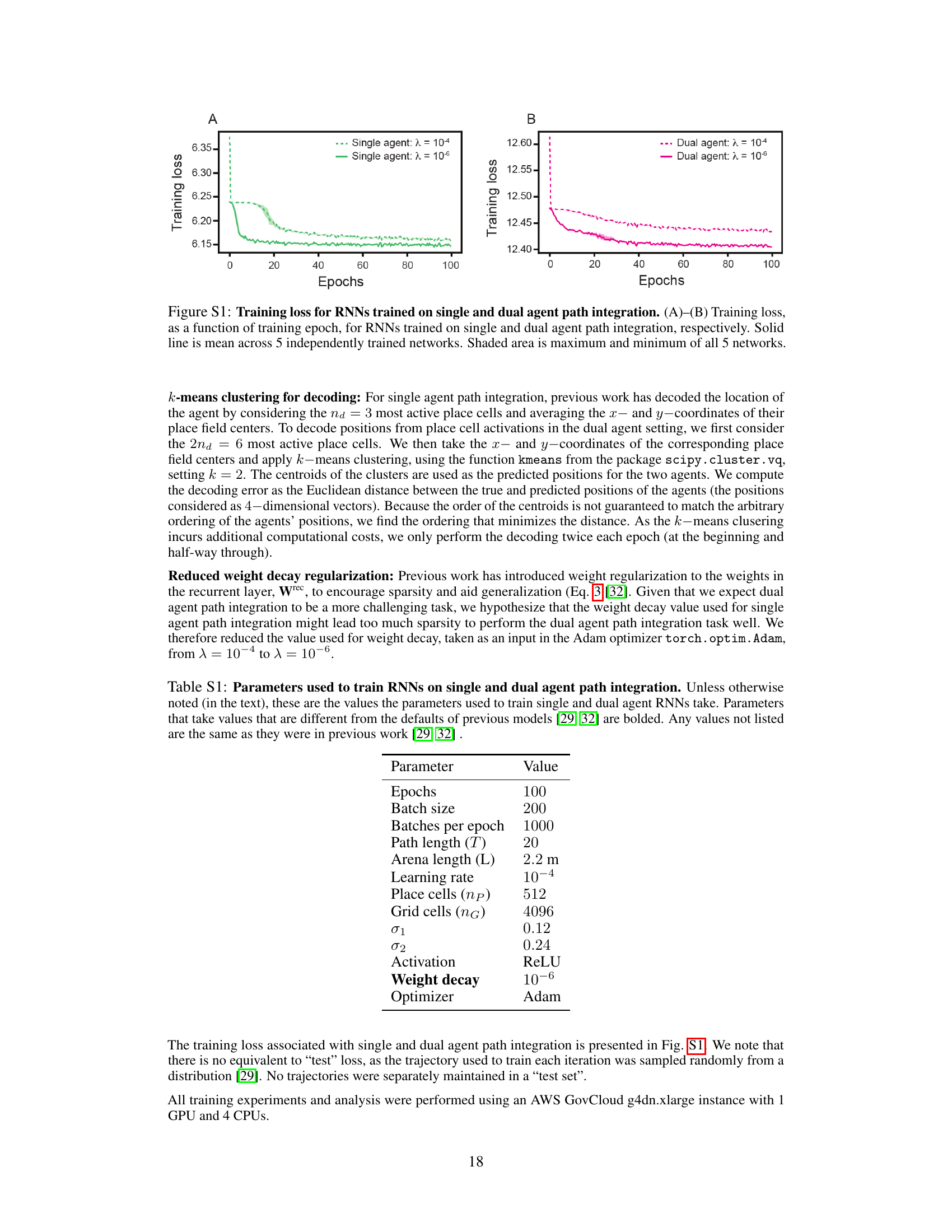

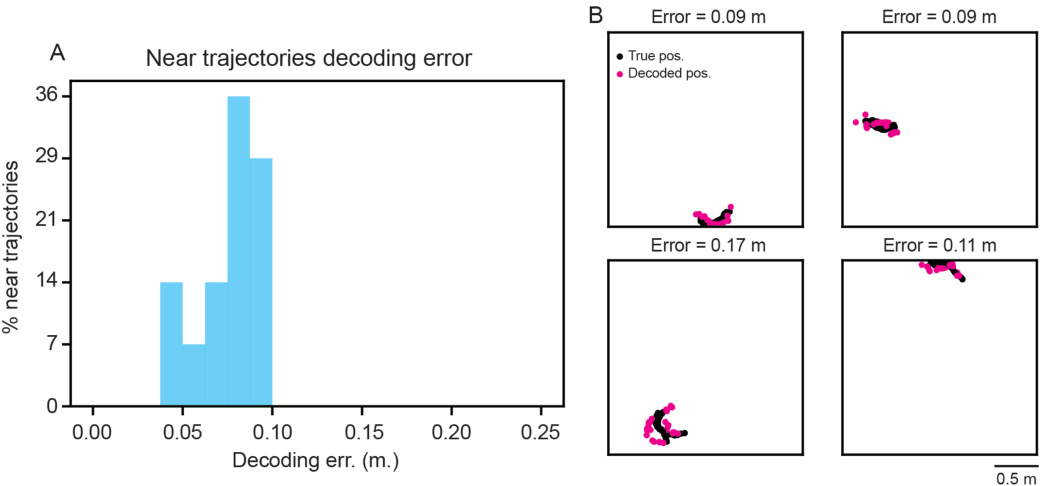

This figure demonstrates the RNN’s ability to perform dual agent path integration. Panel A shows the decoding error over training epochs for single and dual agent RNNs, indicating successful learning for both. Panel B presents the distribution of decoding errors across multiple trajectories for single and dual agent RNNs, highlighting the higher performance of dual agent RNNs. Panel C visually displays example trajectories, illustrating the model’s ability to accurately track the movements of two agents.

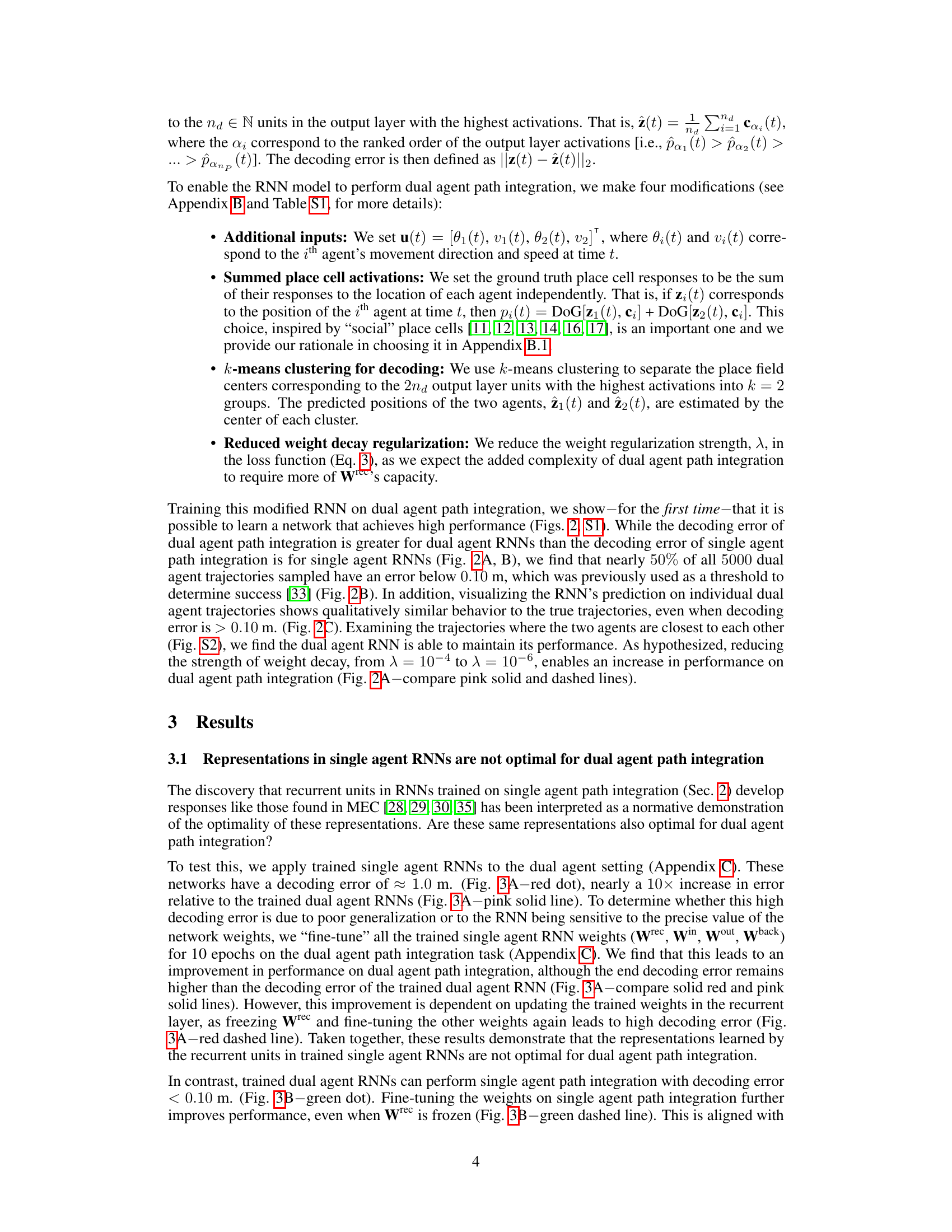

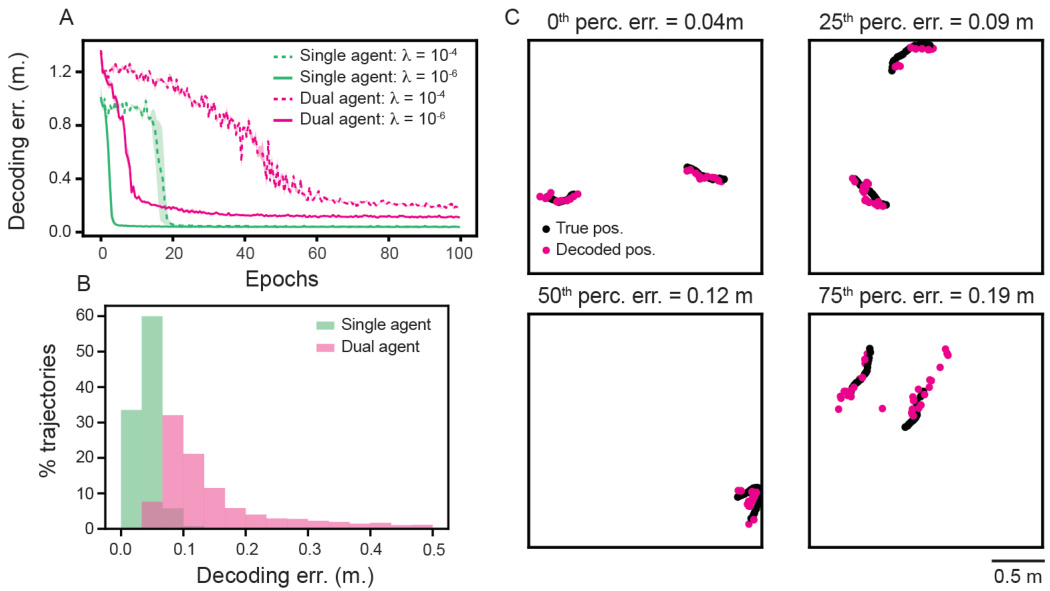

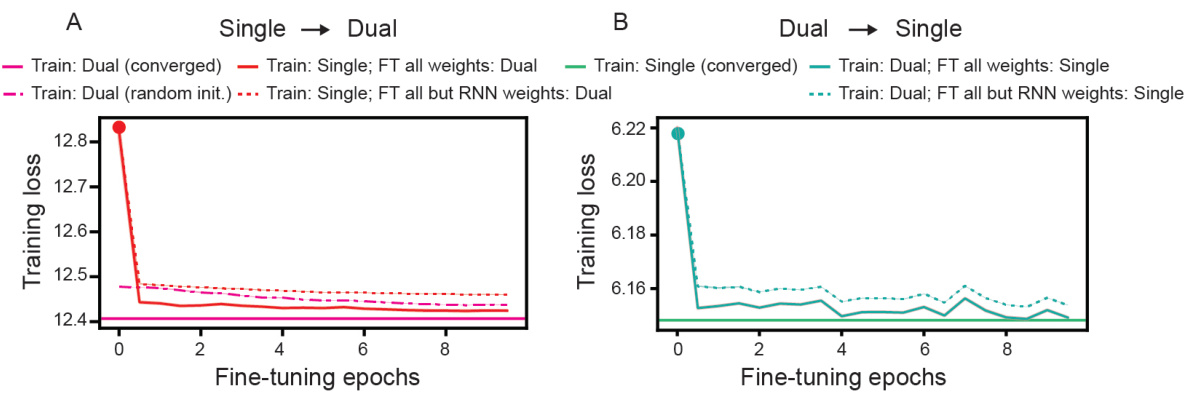

This figure demonstrates that RNNs trained for dual agent path integration can generalize well to single agent path integration tasks, but the opposite is not true. It shows decoding error results, highlighting that representations optimal for one task aren’t necessarily optimal for another. Fine-tuning is also explored to see if single agent trained networks can improve in a dual agent task.

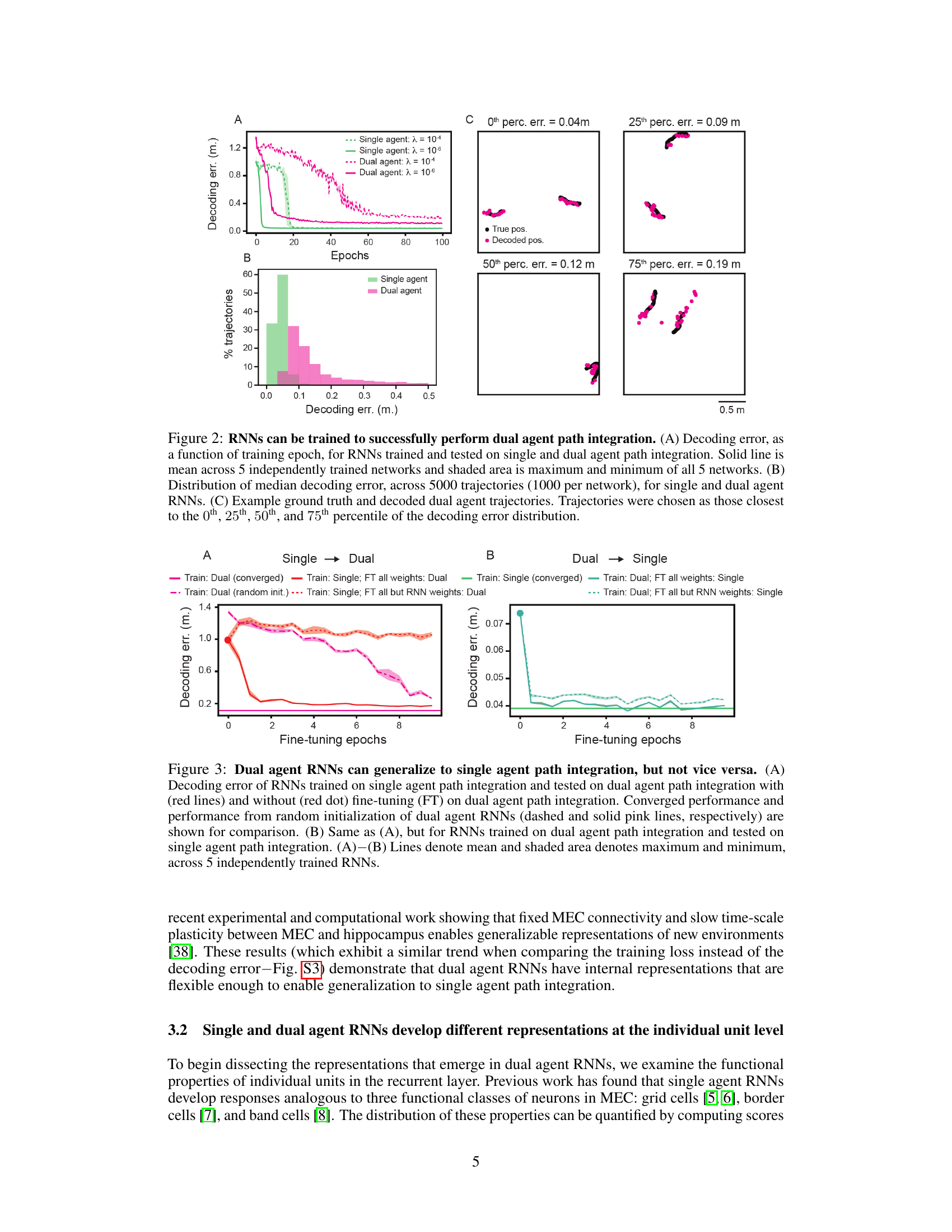

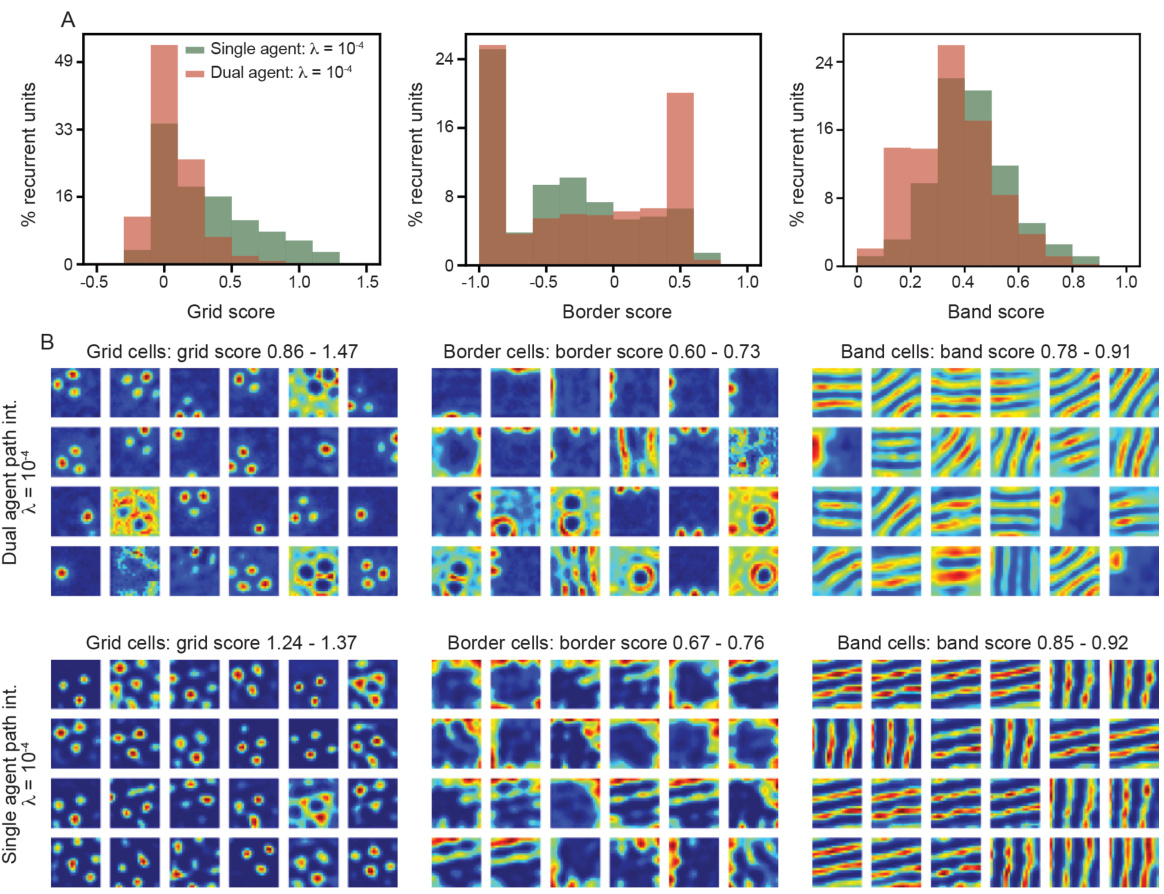

This figure analyzes the differences in the distribution of functional properties (grid, border, and band scores) between single and dual agent RNNs. Panel A shows the distributions of these scores, highlighting statistically significant differences. Panel B visualizes the rate maps for units with the highest scores of each type. Panel C shows that ablating (removing) units with high grid, border, or band scores affects decoding error differently in single vs. dual-agent RNNs, revealing the relative importance of each unit type for the overall network performance.

This figure demonstrates that dual agent RNNs develop tuning for relative positions of the two agents. Panel A shows a schematic of the transformation from allocentric to relative space. Panel B shows the distribution of grid scores for units in relative space. Panel C shows example relative space rate maps with high grid scores. Panel D shows the distribution of spatial information in relative space. Panel E shows example relative space rate maps with high spatial information. Panel F shows the decoding error when units with high relative spatial information are removed.

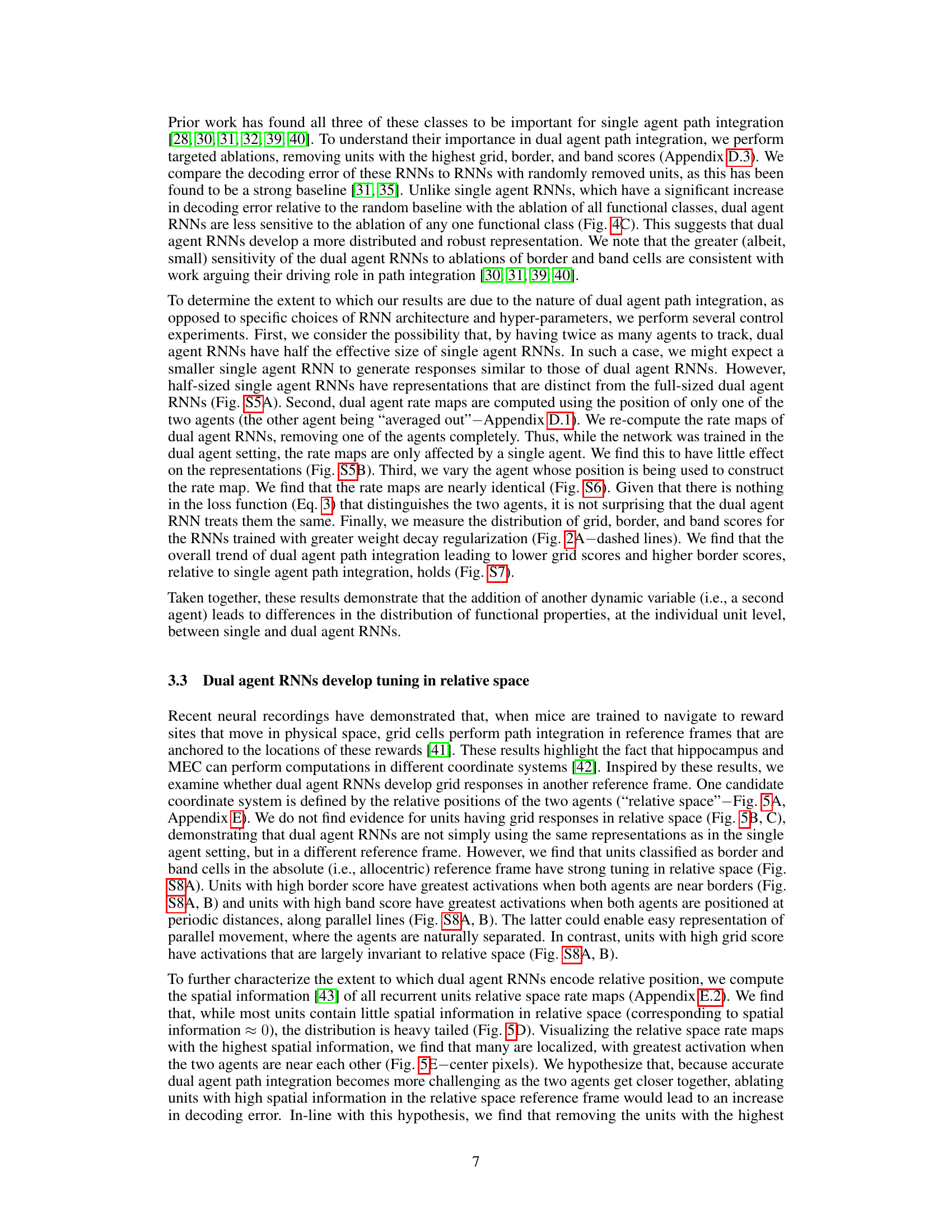

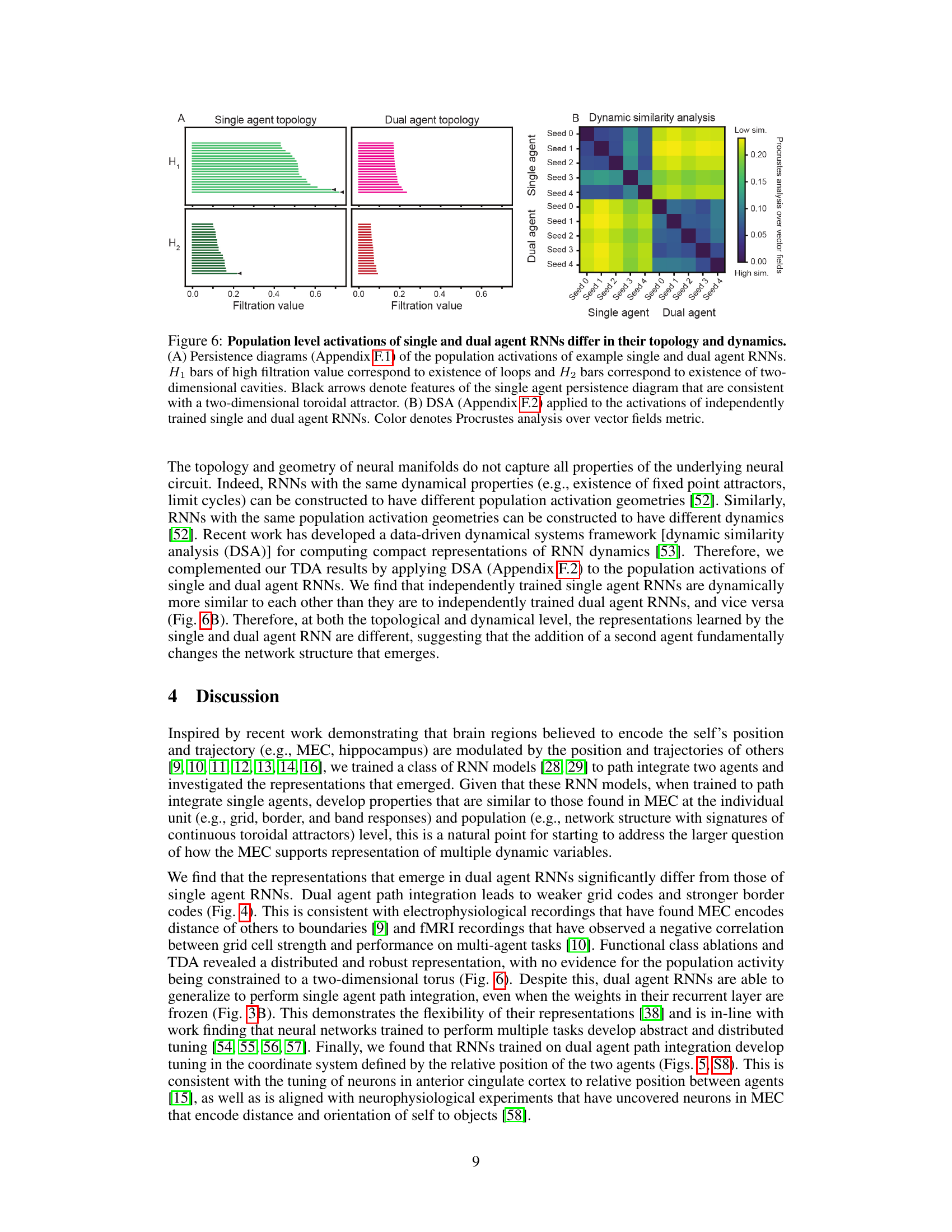

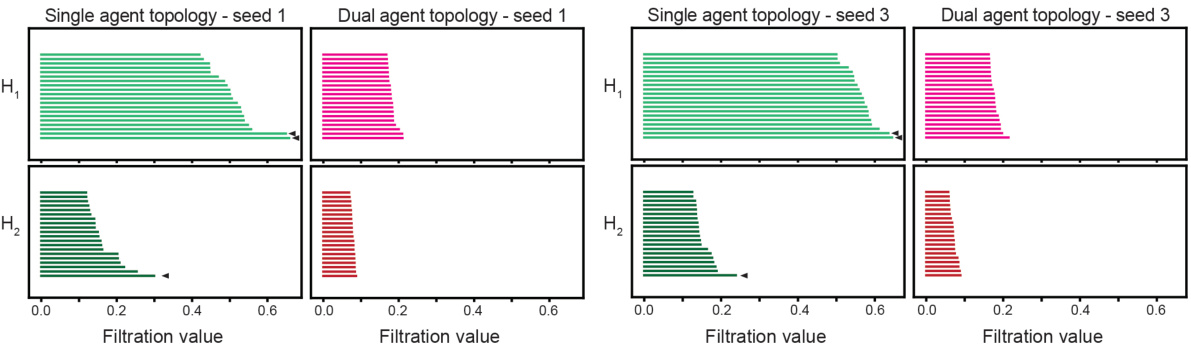

This figure compares the topological and dynamical properties of single and dual agent RNNs at the population level. Panel A shows persistence diagrams, illustrating the topological differences in population activity between single and dual agent RNNs, indicating different manifold structures. Panel B presents the results of dynamic similarity analysis (DSA), highlighting differences in the dynamic properties of the RNNs using a Procrustes analysis over vector fields.

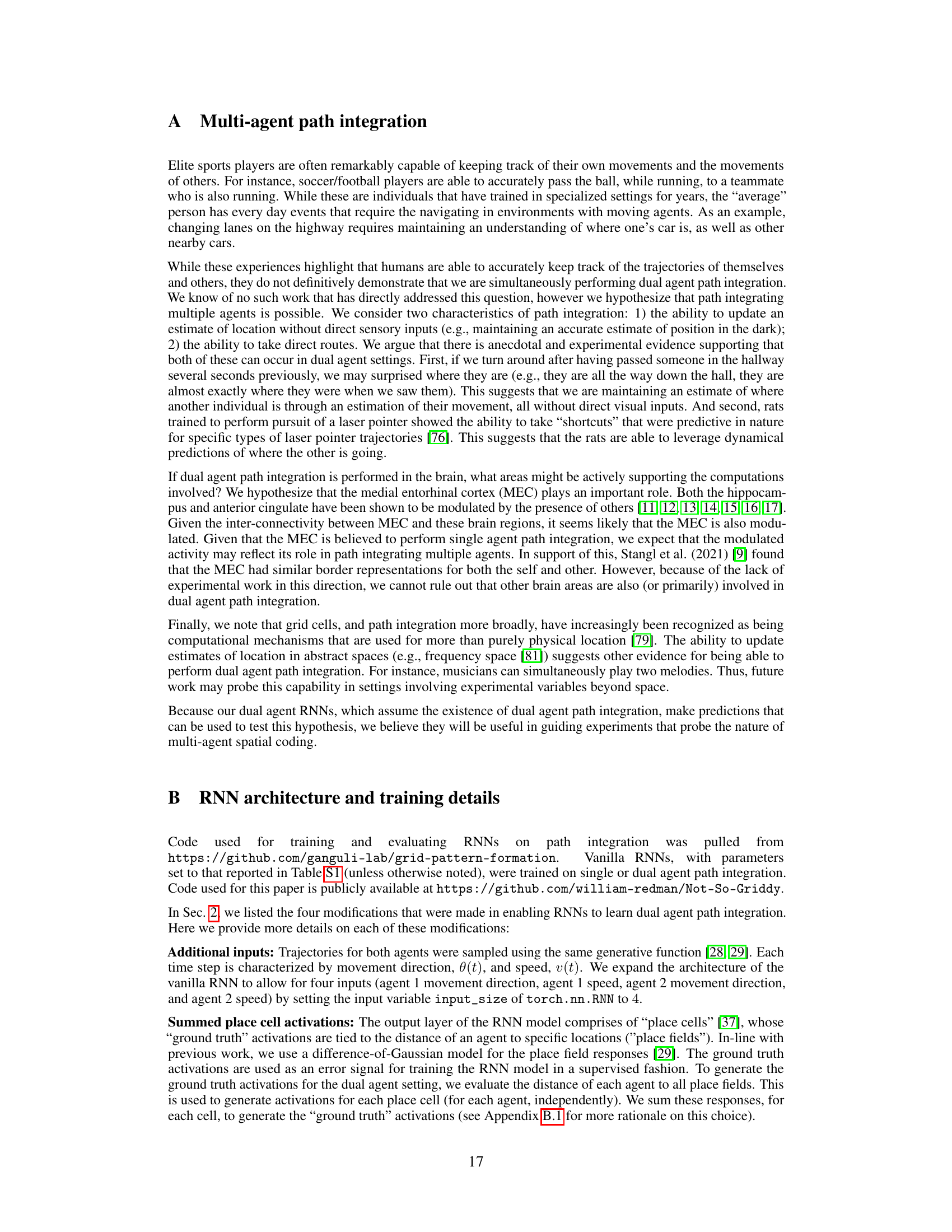

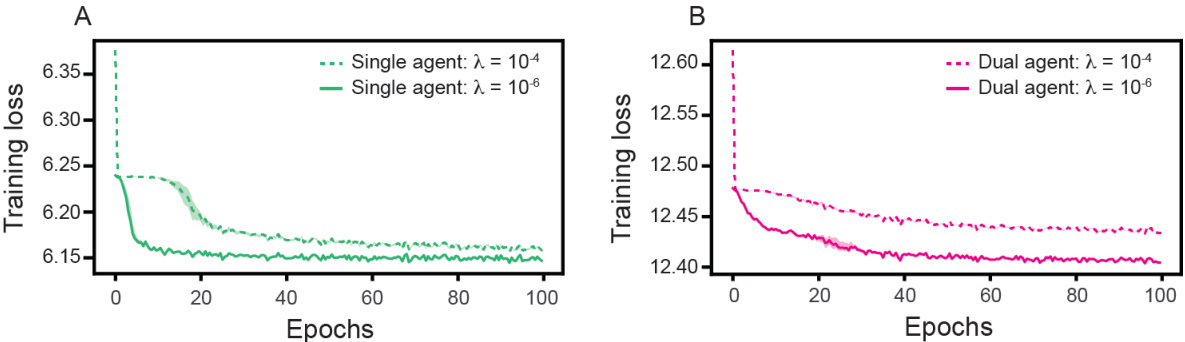

This figure shows the training loss curves for recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained on single-agent and dual-agent path integration tasks. The plots illustrate how the training loss decreases over epochs for both tasks, under two different weight decay regularization strengths (λ = 10⁻⁴ and λ = 10⁻⁶). The solid lines represent the average loss across five independent training runs for each condition, while the shaded regions show the minimum and maximum losses observed across these runs.

This figure shows the results of training recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to perform both single and dual agent path integration. Panel A shows the decoding error over training epochs for both types of networks. Panel B displays the distribution of decoding errors across many test trajectories. Panel C provides example trajectories comparing ground truth and RNN-predicted paths for different error levels.

This figure demonstrates the generalization capabilities of single and dual agent RNNs when tested on tasks they were not trained on. Panel A shows that single-agent RNNs fail to generalize to dual-agent tasks, even after fine-tuning, while dual-agent RNNs generalize relatively well to single-agent tasks. Panel B shows the opposite experiment: dual-agent RNNs generalize relatively well to single-agent tasks, while single-agent RNNs can’t generalize to dual agent tasks even after fine-tuning. This highlights the difference in representation learned by the two networks.

This figure shows the consistency of the individual unit level representations across five independently trained dual agent RNNs. Each of the five RNNs was trained separately. The figure displays the rate maps (spatial activation patterns) for units with the highest grid, border, and band scores, for each of the five RNNs. The consistency across the different RNNs demonstrates the robustness of the learned representations.

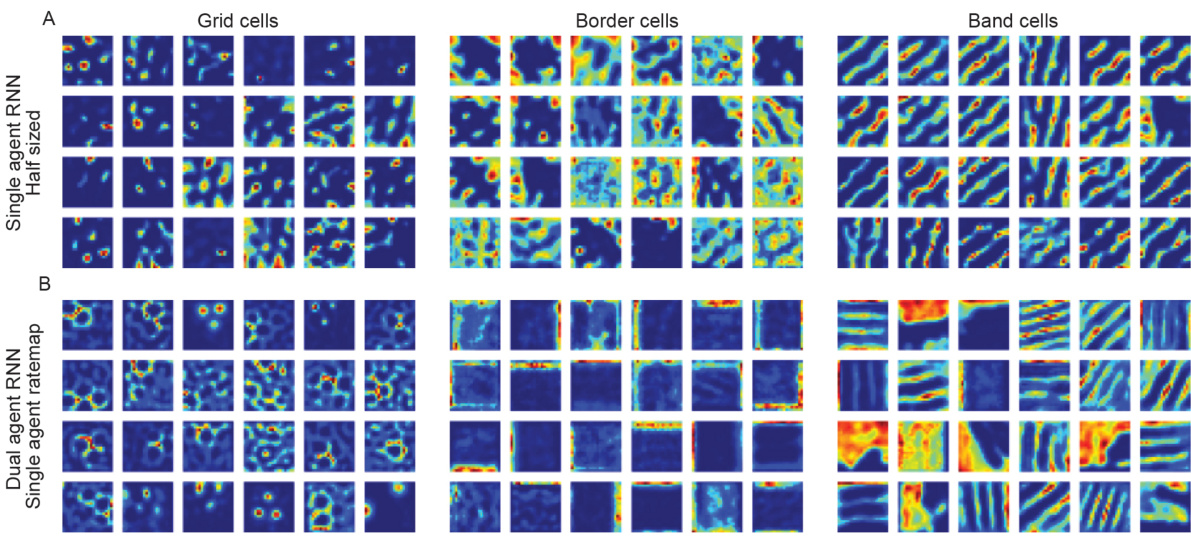

This figure shows the rate maps of RNNs trained on single-agent path integration, but with half the number of recurrent and output units as the dual-agent RNNs, compared to those trained on dual-agent path integration but with single-agent ratemaps. The visualization demonstrates the effect of different training conditions and network architectures on the resulting neural representations of the spatial environment.

This figure shows the differences in the distribution of functional properties (grid, border, and band scores) between single and dual agent RNNs. Panel A displays the distributions of these scores, highlighting statistically significant differences. Panel B provides visualizations of the rate maps (spatial activation patterns) for units with the highest scores in each category. Panel C demonstrates the impact of ablating (removing) units with high scores in each category on the decoding error, contrasting this with the effect of ablating random units.

This figure shows that single and dual agent RNNs have different distributions of functional properties (grid, border, and band scores). Dual agent RNNs have weaker grid responses and stronger border and band responses than single agent RNNs. Ablation studies show that dual agent RNNs are more robust to the removal of individual units than single agent RNNs.

This figure shows the comparison of rate maps in allocentric and relative spaces for units with high grid, border, and band scores from a dual-agent RNN. Panel A displays the rate maps, while panel B provides schematic illustrations to clarify the relative space representation. The results indicate that border and band cells, unlike grid cells, encode information about the relative positions of the two agents.

This figure compares the population-level activity of single and dual-agent RNNs using topological data analysis (TDA) and dynamic similarity analysis (DSA). TDA reveals differences in the topological structure of the RNN activations, with single-agent RNNs showing features consistent with a two-dimensional toroidal attractor, while dual-agent RNNs lack such clear structure. DSA further shows that the RNN dynamics differ significantly. The results demonstrate fundamental differences in the network structure resulting from the inclusion of a second agent.

This figure shows a box plot comparing the topological distance between persistence diagrams of single and dual agent RNNs and an idealized torus. The heat distance, a measure of the difference between persistence diagrams, indicates that single-agent RNNs exhibit a topology closer to that of an ideal torus compared to dual-agent RNNs. This difference in topology further suggests fundamental changes in network structure when transitioning from single to multi-agent path integration.

This figure shows the results of a dynamic similarity analysis (DSA) comparing the dynamics of single-agent and dual-agent recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Different hyperparameters were used for the DSA compared to Figure 6 in the main paper. The color-coded matrix shows the Procrustes analysis over vector fields metric, a measure of dynamical similarity. The results demonstrate that single-agent RNNs exhibit greater dynamical similarity to each other than to dual-agent RNNs, and vice-versa, even with different hyperparameter choices, thus supporting the conclusion that the underlying network structures differ.

More on tables

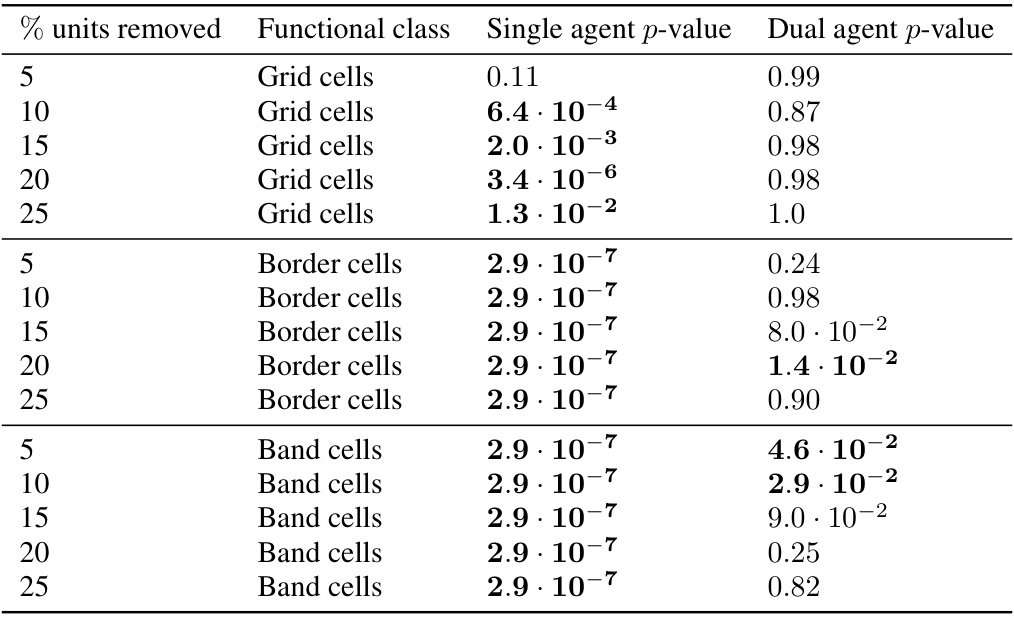

This table presents the results of Mann-Whitney U tests comparing the decoding error of RNNs with specific functional classes (grid, border, and band cells) ablated to the decoding error of RNNs with the same number of randomly ablated units. The tests assess whether ablating specific functional units leads to significantly higher decoding error than ablating random units. The p-values indicate the statistical significance of the differences. A lower p-value suggests a greater impact of ablating the specific functional unit than ablating random units. Bold p-values indicate significance at the p < 0.05 level.

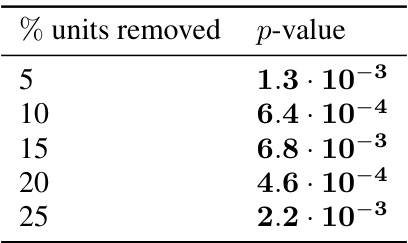

This table presents the results of Mann-Whitney U tests assessing the statistical significance of differences in decoding error between dual agent RNNs with ablated units and those with randomly ablated units. The ablation targets units with high relative spatial information. The p-values indicate the probability of observing the results if there was no difference between the groups. Lower p-values suggest a stronger effect of the ablations.

Full paper#