TL;DR#

Many applications need to model the relationship between two related time series, such as neural activity and behavior, while distinguishing their shared and unique aspects. Existing methods often fail to properly address this challenge. This limitation hinders accurate modeling and interpretation of complex systems.

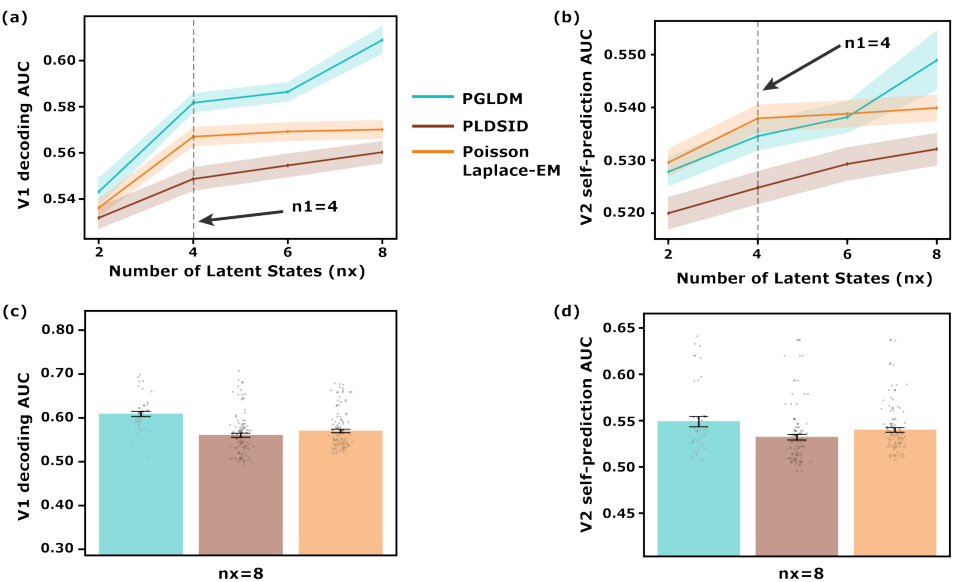

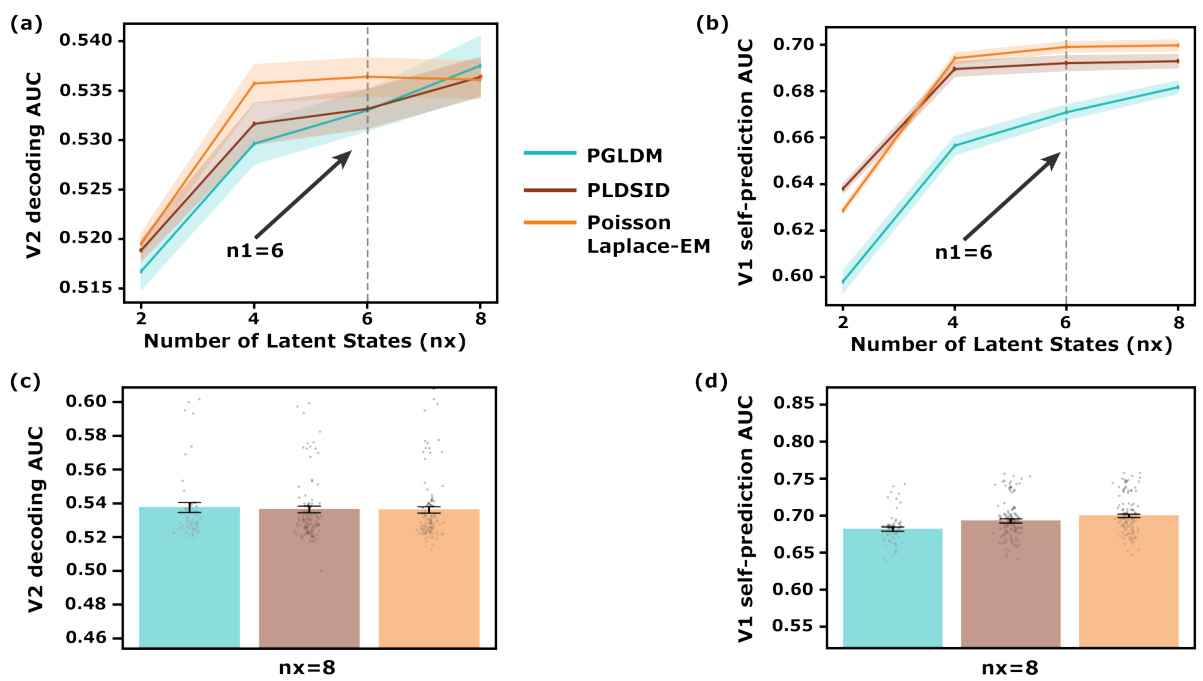

This work introduces Prioritized Generalized-Linear Dynamical Modeling (PGLDM). PGLDM uses a multi-step analytical subspace identification algorithm to model shared and private dynamics. Simulation and real-world neural data experiments demonstrate PGLDM’s superior accuracy in decoding one time series from the other, using significantly fewer latent states. This improvement makes the method more efficient and reduces model complexity.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with multivariate time-series data, especially in neuroscience and other fields dealing with complex dynamical systems. It offers a novel method for disentangling shared and private dynamics, improving model accuracy and interpretability. This opens avenues for more sophisticated analyses of neural data and similar datasets, furthering our understanding of complex systems and driving advancements in related fields.

Visual Insights#

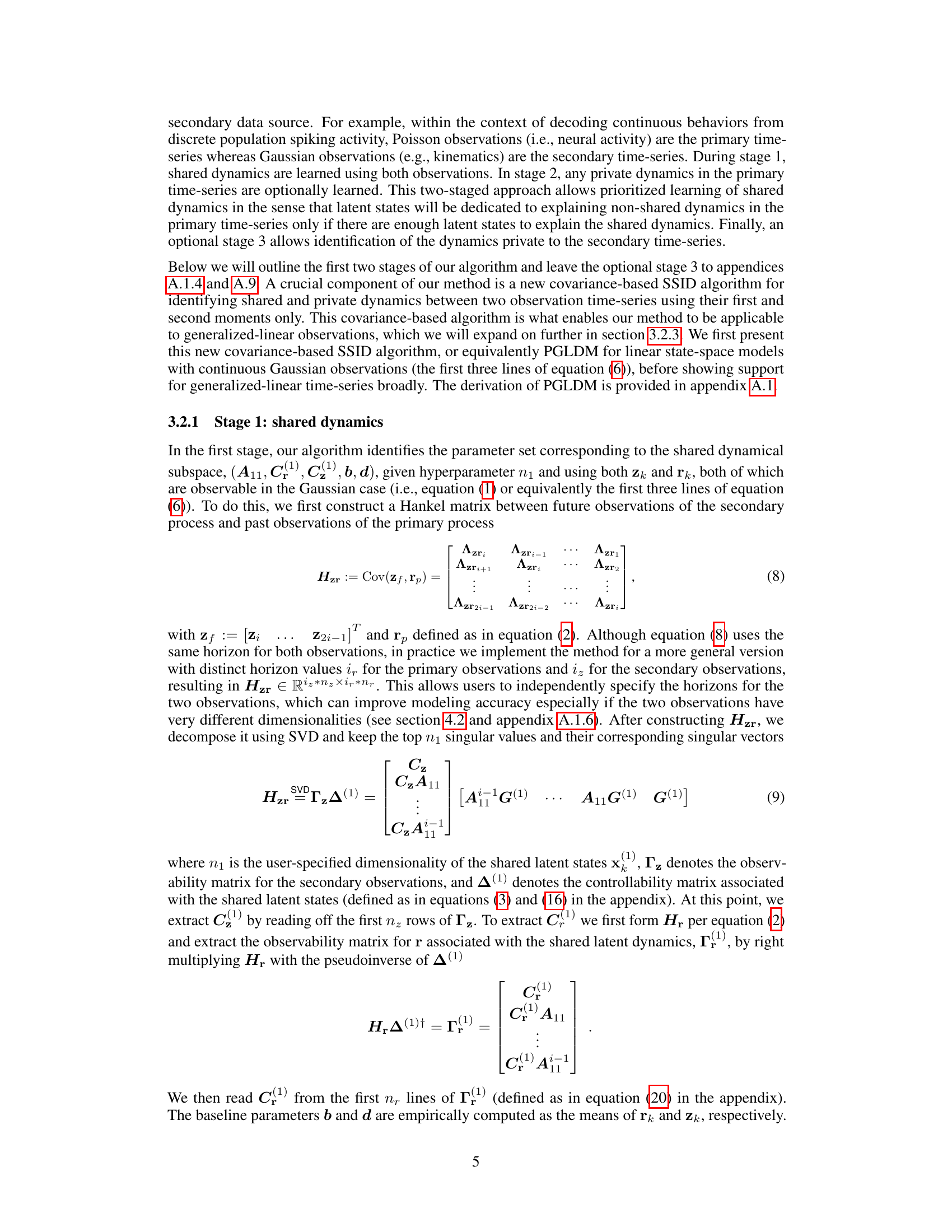

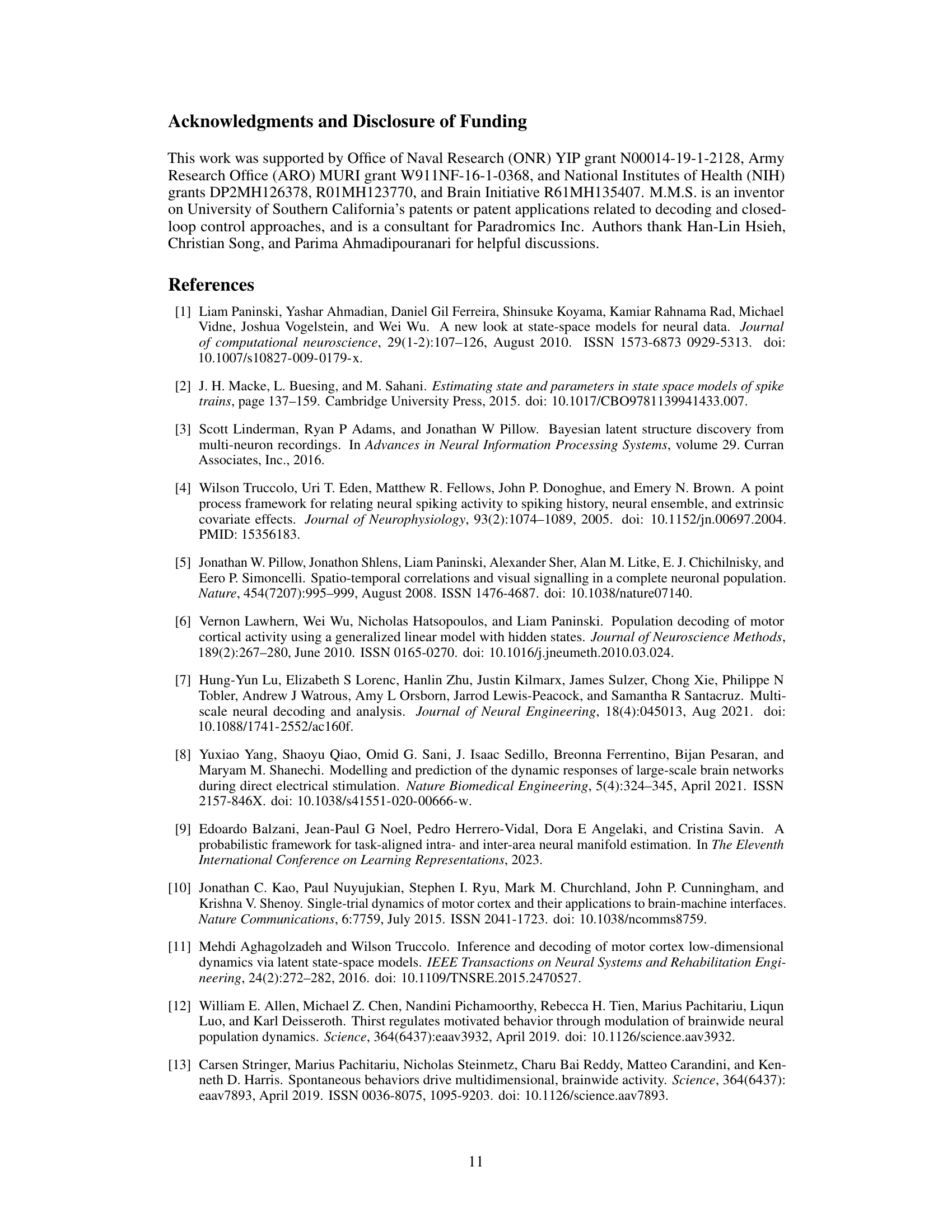

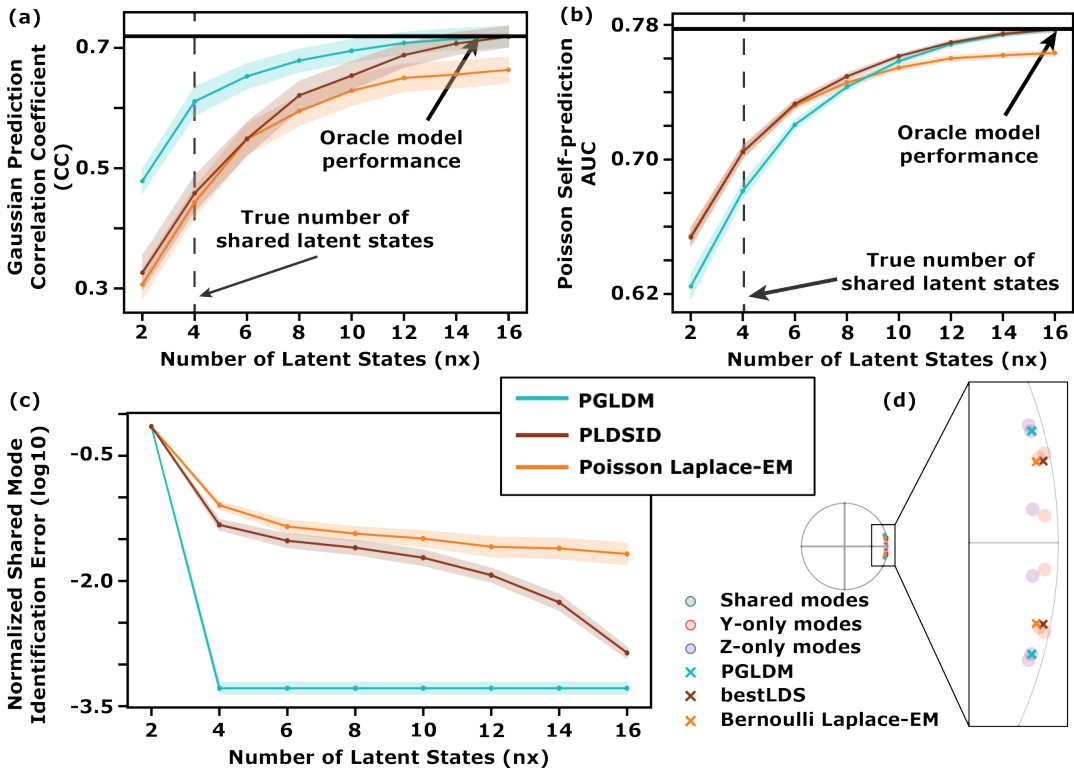

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PGLDM algorithm to existing methods (PLDSID, Laplace EM, bestLDS) in learning shared and private dynamics between two generalized linear processes. It demonstrates PGLDM’s improved accuracy in identifying shared dynamics across different observation types (Gaussian, Poisson, Bernoulli). The figure highlights PGLDM’s superior predictive power, particularly in low-dimensional settings, showing its ability to predict Gaussian observations from Poisson data more accurately than competing methods.

read the caption

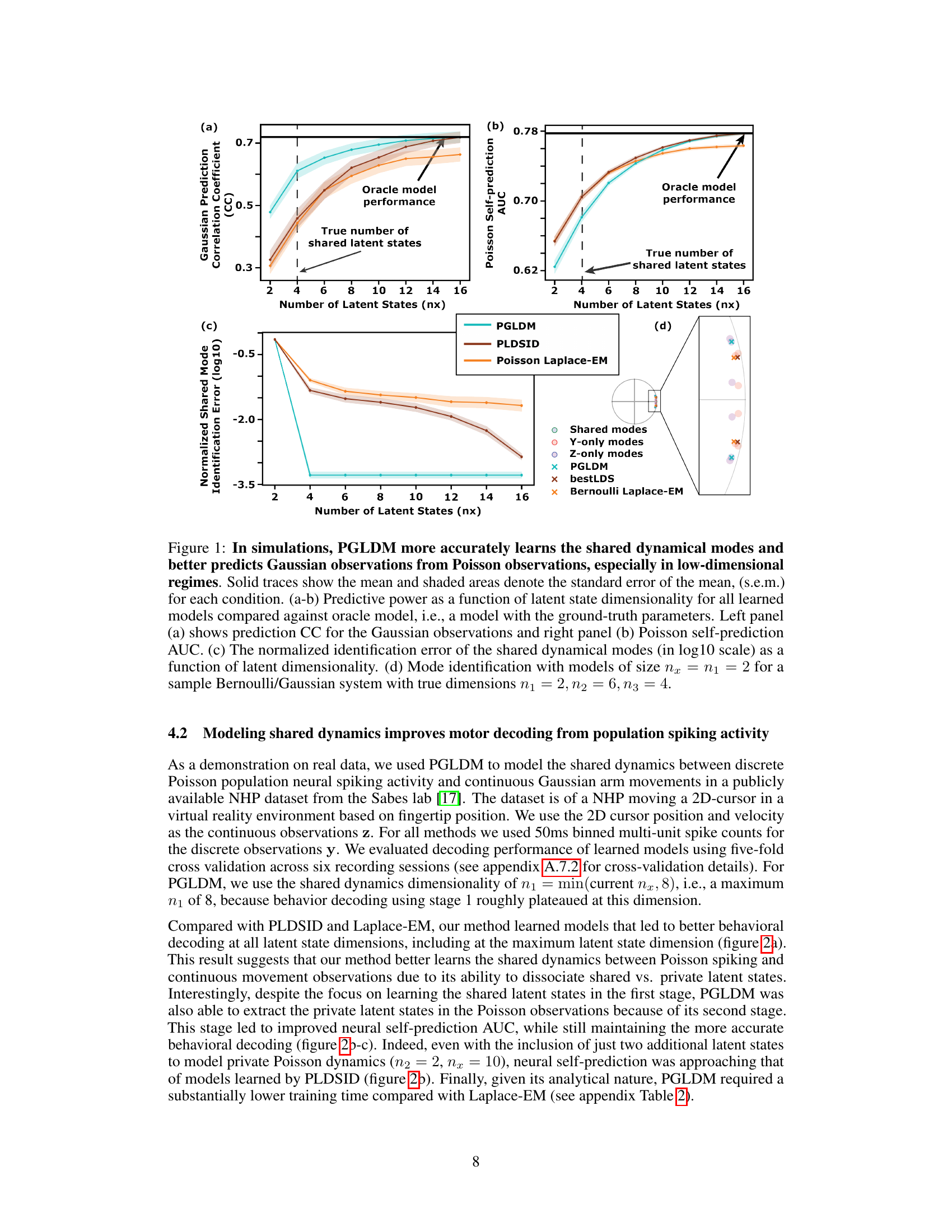

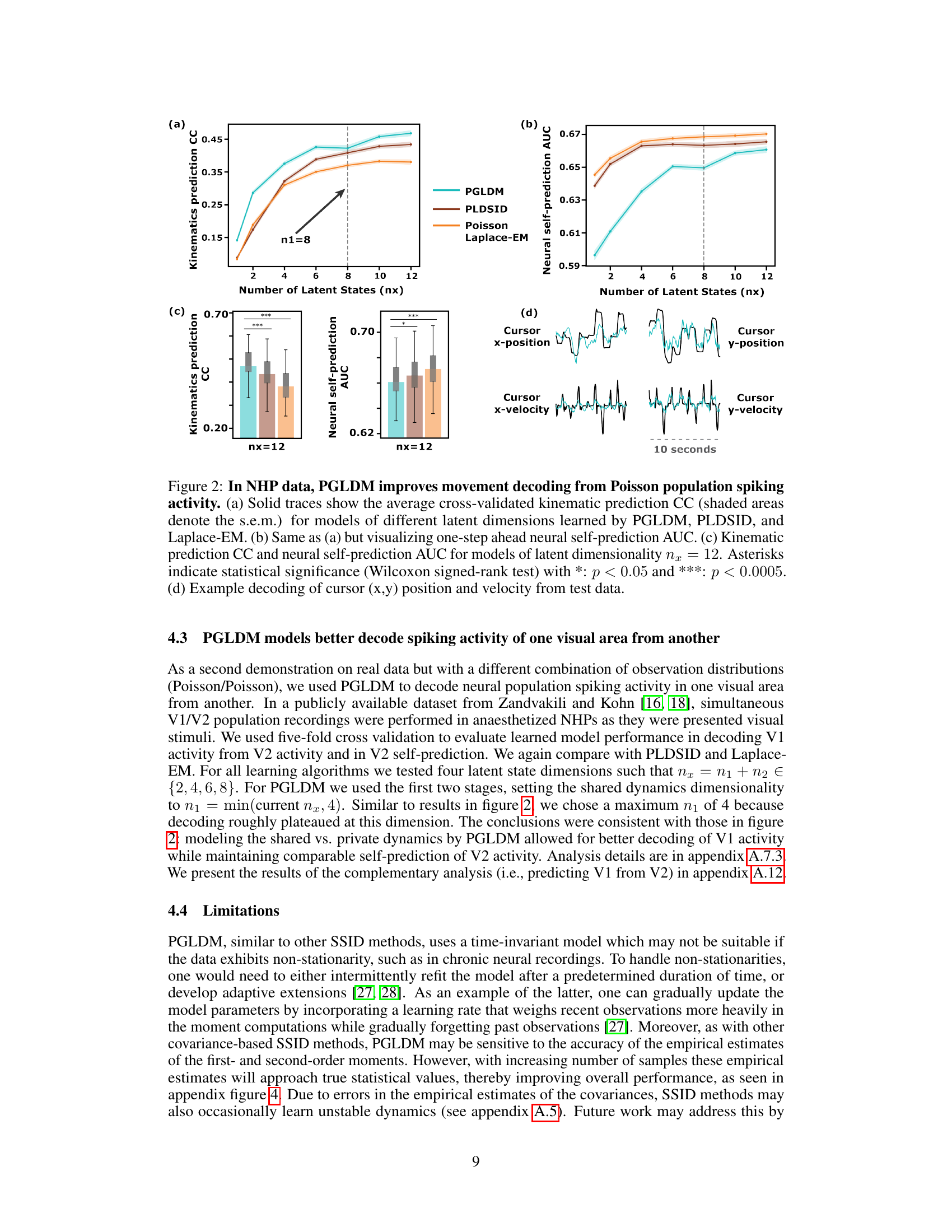

Figure 1: In simulations, PGLDM more accurately learns the shared dynamical modes and better predicts Gaussian observations from Poisson observations, especially in low-dimensional regimes. Solid traces show the mean and shaded areas denote the standard error of the mean, (s.e.m.) for each condition. (a-b) Predictive power as a function of latent state dimensionality for all learned models compared against oracle model, i.e., a model with the ground-truth parameters. Left panel (a) shows prediction CC for the Gaussian observations and right panel (b) Poisson self-prediction AUC. (c) The normalized identification error of the shared dynamical modes (in log10 scale) as a function of latent dimensionality. (d) Mode identification with models of size nx = n1 = 2 for a sample Bernoulli/Gaussian system with true dimensions n₁ = 2, n₂ = 6, n₃ = 4.

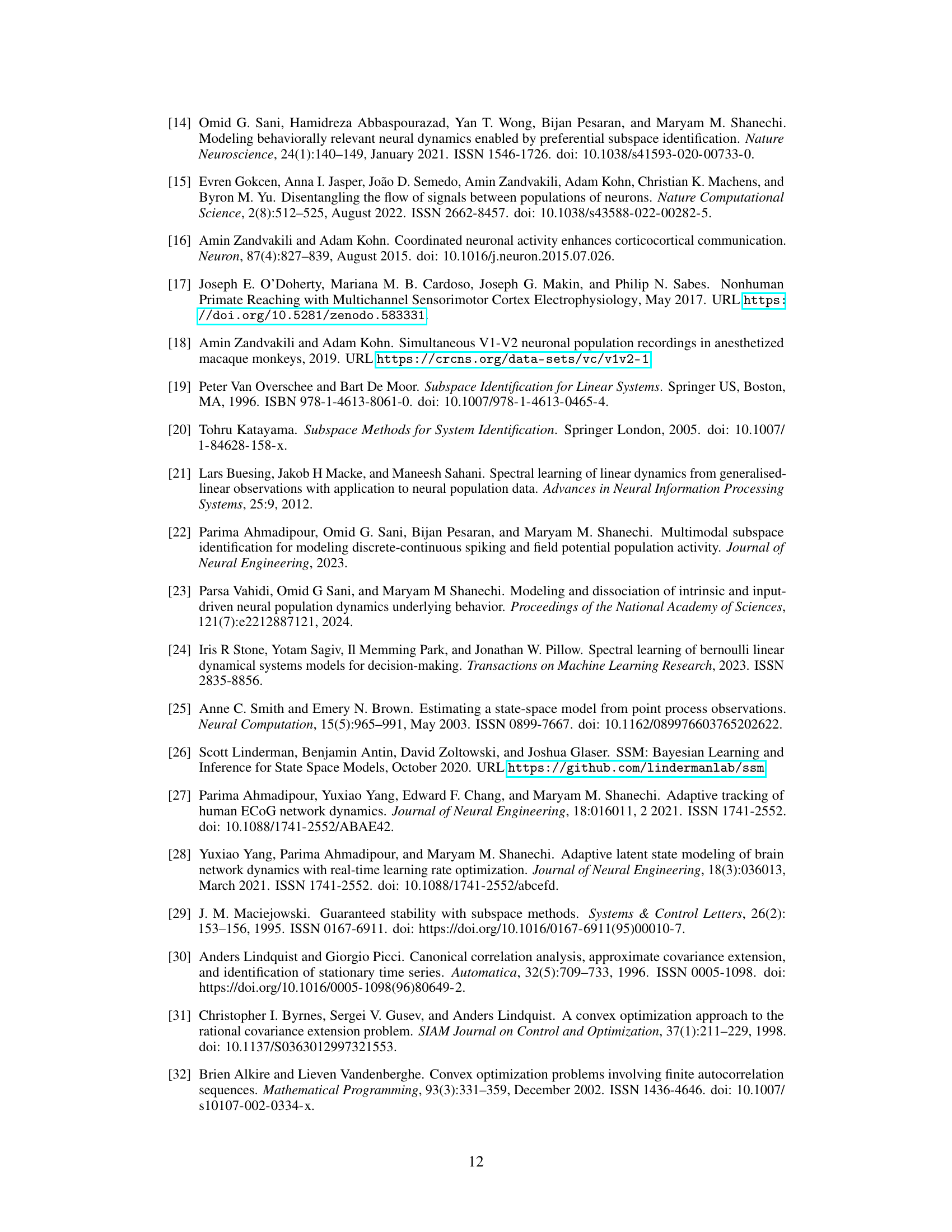

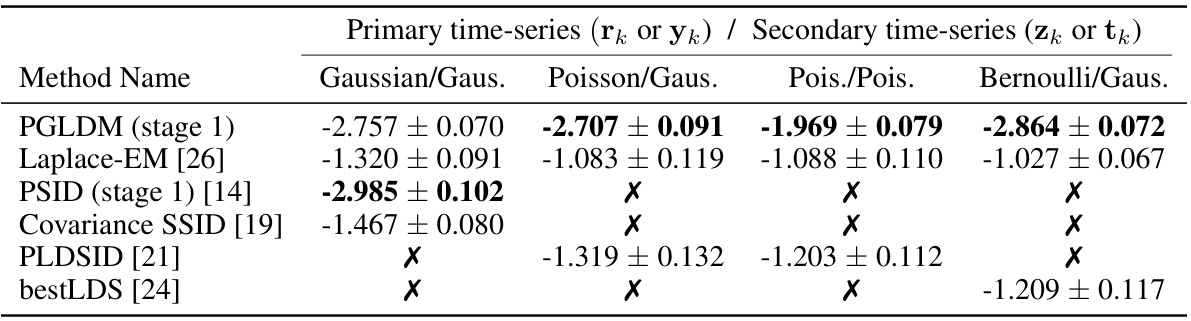

🔼 The table shows the performance of different methods in identifying shared dynamics between two generalized linear time series with different observation types (Gaussian, Poisson, Bernoulli). The error is calculated as the log10 of the normalized eigenvalue error, reflecting the accuracy of identifying the shared latent states (nx = n₁). An ‘X’ indicates that a method is not applicable for a specific observation type.

read the caption

Table 1: Shared mode identification error (log10, i.e., -2 means 1%) at the shared latent dimensionality (nx = n₁). X indicates that a method (row) does not support the primary observation model (column).

In-depth insights#

Shared Dynamics#

The concept of ‘Shared Dynamics’ in this research paper centers on disentangling the intertwined dynamics of two distinct time-series. The authors recognize that many real-world systems, especially in neuroscience where they apply their model, exhibit interdependencies. Traditional models often struggle to isolate the unique and shared influences impacting these related signals. This work proposes a novel approach to specifically model and dissociate shared and private dynamics. This is a significant contribution because it allows for a more nuanced understanding of complex systems; highlighting the shared mechanisms driving correlated activity, and the individual factors contributing unique variation to each time series. Such dissociation helps improve the accuracy of predictive models and provides insights into the underlying mechanisms of interactions, which can be particularly valuable in neurobiological research to understand how different brain regions interact.

GLDM Algorithm#

The generalized linear dynamical model (GLDM) algorithm presented in the paper offers a novel approach to modeling the shared and private dynamics between two generalized-linear time series. Its multi-stage approach prioritizes the identification of shared dynamics before focusing on private dynamics, improving the accuracy of decoding and prediction tasks. This is a significant advancement over existing GLDM methods, which typically focus on single time series. The algorithm’s strength lies in its ability to seamlessly handle various observation distributions (e.g., Gaussian, Poisson, Bernoulli), and its application to both simulated and real neural data demonstrates its practical value and robustness. However, the method’s sensitivity to noise and reliance on empirical covariance estimates are important considerations, limiting its applicability to high-noise conditions. Future research could explore addressing these limitations and extending the approach to non-linear dynamical systems.

Poisson GLDS#

Poisson Generalized Linear Dynamical Systems (GLDMS) offer a powerful framework for modeling neural spiking activity. They elegantly combine the advantages of linear dynamical systems with the ability to handle count data, which is characteristic of neural spike trains. The Poisson distribution naturally models the probabilistic nature of spiking, where the probability of observing a spike in a given time bin depends on an underlying latent state. GLDMS effectively capture the temporal dynamics of this latent state, allowing for the prediction of spiking activity and the inference of unobserved neural processes. A key challenge lies in parameter estimation, often tackled using techniques like Expectation-Maximization (EM) or subspace methods. Careful consideration of the Poisson likelihood is crucial to ensure accurate estimation. Furthermore, the choice of latent state dimensionality impacts model complexity and predictive power; too few states may fail to capture temporal dynamics, while too many can lead to overfitting. Research applying Poisson GLDMS focuses on neural decoding, inferring latent variables such as movement intentions from spiking patterns, as well as on modeling neural population activity and uncovering shared and private dynamics within multiple neural regions.

Decoding Results#

A hypothetical ‘Decoding Results’ section would present a multifaceted analysis of the model’s performance in decoding neural data. It would likely begin by quantifying the accuracy of decoding various behavioral variables (e.g., movement kinematics) from patterns of neural activity. Key metrics such as correlation coefficients, explained variance, and decoding error rates would be reported, potentially across various experimental conditions or time scales. Furthermore, the section would investigate the model’s ability to distinguish between different behaviors, demonstrating its capacity to discriminate between nuanced neural patterns corresponding to distinct actions or intentions. A comparison to alternative decoding models (e.g., simpler regression models or other neural network architectures) would validate the model’s superior performance. Finally, the analysis would delve into the interpretability of the model’s latent variables, potentially revealing neural correlates of behavior or uncovering latent states representing abstract cognitive processes. Robustness analyses, examining the impact of noise, missing data, or varying model parameters on decoding accuracy, would provide further insights into the model’s reliability and generalizability.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Extending PGLDM to handle non-stationary time series is crucial for real-world applications where neural data often exhibits temporal dynamics. This might involve incorporating adaptive algorithms or employing techniques from control theory. Investigating the impact of different link functions beyond Poisson, Bernoulli, and Gaussian on the model’s performance and interpretability could broaden its applicability to a wider range of neuroscience data. Exploring the use of different subspace identification methods alongside PGLDM and evaluating their relative strengths and weaknesses in scenarios with varying levels of noise and data sparsity would provide valuable insights. Additionally, a comprehensive comparison with deep learning models would be beneficial in determining when the interpretability and efficiency of PGLDM outweigh the potential higher accuracy of deep learning approaches. Finally, applying the framework to other domains beyond neuroscience, where multi-source time-series modeling is needed, could reveal unexpected benefits and applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of the PGLDM algorithm in simulations. Panel (a) and (b) show the predictive power (correlation coefficient for Gaussian predictions and AUC for Poisson self-predictions) for different numbers of latent states, comparing PGLDM to other methods. Panel (c) shows the error in identifying shared modes for different numbers of latent states. Panel (d) visually illustrates the modes identified by different methods, showing the separation of shared and private dynamics.

read the caption

Figure 1: In simulations, PGLDM more accurately learns the shared dynamical modes and better predicts Gaussian observations from Poisson observations, especially in low-dimensional regimes. Solid traces show the mean and shaded areas denote the standard error of the mean, (s.e.m.) for each condition. (a-b) Predictive power as a function of latent state dimensionality for all learned models compared against oracle model, i.e., a model with the ground-truth parameters. Left panel (a) shows prediction CC for the Gaussian observations and right panel (b) Poisson self-prediction AUC. (c) The normalized identification error of the shared dynamical modes (in log10 scale) as a function of latent dimensionality. (d) Mode identification with models of size nx = n1 = 2 for a sample Bernoulli/Gaussian system with true dimensions n₁ = 2, n2 = 6, n3 = 4.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of PGLDM in comparison to other methods in simulations. Panel (a) and (b) show the predictive power (correlation coefficient and AUC) as a function of the number of latent states used. The results show that PGLDM performs better, especially with fewer states. Panel (c) shows the error in identifying the shared dynamical modes, with PGLDM exhibiting lower error. Finally, panel (d) provides a visualization of the mode identification results for a specific simulation.

read the caption

Figure 1: In simulations, PGLDM more accurately learns the shared dynamical modes and better predicts Gaussian observations from Poisson observations, especially in low-dimensional regimes. Solid traces show the mean and shaded areas denote the standard error of the mean, (s.e.m.) for each condition. (a-b) Predictive power as a function of latent state dimensionality for all learned models compared against oracle model, i.e., a model with the ground-truth parameters. Left panel (a) shows prediction CC for the Gaussian observations and right panel (b) Poisson self-prediction AUC. (c) The normalized identification error of the shared dynamical modes (in log10 scale) as a function of latent dimensionality. (d) Mode identification with models of size nx = n1 = 2 for a sample Bernoulli/Gaussian system with true dimensions n₁ = 2, n₂ = 6, n₃ = 4.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of PGLDM in simulations, comparing it to other methods. Panel (a) and (b) show the predictive power (correlation coefficient for Gaussian prediction and AUC for Poisson self-prediction) as a function of the number of latent states. Panel (c) illustrates the normalized shared mode identification error, also as a function of the number of latent states. Finally, panel (d) presents a visualization of mode identification for a specific Bernoulli/Gaussian system.

read the caption

Figure 1: In simulations, PGLDM more accurately learns the shared dynamical modes and better predicts Gaussian observations from Poisson observations, especially in low-dimensional regimes. Solid traces show the mean and shaded areas denote the standard error of the mean, (s.e.m.) for each condition. (a-b) Predictive power as a function of latent state dimensionality for all learned models compared against oracle model, i.e., a model with the ground-truth parameters. Left panel (a) shows prediction CC for the Gaussian observations and right panel (b) Poisson self-prediction AUC. (c) The normalized identification error of the shared dynamical modes (in log10 scale) as a function of latent dimensionality. (d) Mode identification with models of size nx = n1 = 2 for a sample Bernoulli/Gaussian system with true dimensions n₁ = 2, n2 = 6, n3 = 4.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of PGLDM in comparison to other methods across different latent dimensionalities. The left panels show the predictive power of PGLDM for both Gaussian and Poisson observations, while the right panels show the accuracy of shared mode identification and mode identification results for different observation model pairs. The results indicate that PGLDM is more accurate and efficient, particularly in low-dimensional settings.

read the caption

Figure 1: In simulations, PGLDM more accurately learns the shared dynamical modes and better predicts Gaussian observations from Poisson observations, especially in low-dimensional regimes. Solid traces show the mean and shaded areas denote the standard error of the mean, (s.e.m.) for each condition. (a-b) Predictive power as a function of latent state dimensionality for all learned models compared against oracle model, i.e., a model with the ground-truth parameters. Left panel (a) shows prediction CC for the Gaussian observations and right panel (b) Poisson self-prediction AUC. (c) The normalized identification error of the shared dynamical modes (in log10 scale) as a function of latent dimensionality. (d) Mode identification with models of size nx = n1 = 2 for a sample Bernoulli/Gaussian system with true dimensions n₁ = 2, n₂ = 6, n₃ = 4.

Full paper#