↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Density estimation faces the ‘curse of dimensionality’ in high dimensions, making accurate estimations challenging. Traditional methods often struggle with complex relationships and require massive datasets. This paper focuses on structured data where dependencies between variables follow a graphical model (e.g., Markov Random Field), suggesting that the complexity depends less on the overall dimensionality but rather on the graph’s connectivity.

The authors introduce ‘graph resilience,’ a novel metric quantifying the graph’s connectivity. Their key finding shows that the sample complexity of estimating a structured density depends on graph resilience instead of the full dimensionality. This means estimations are significantly more efficient, even for high-dimensional data with underlying structured dependencies. They provide theoretical guarantees and practical examples demonstrating improvements in sample complexity for diverse graph structures, such as trees, grids, and sequential data. This approach significantly expands the potential of handling structured high-dimensional datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents a novel approach to density estimation, a fundamental problem in machine learning. It directly tackles the “curse of dimensionality,” a major obstacle in high-dimensional data analysis. By leveraging graph structures, the research offers a significant improvement in sample complexity and opens up new avenues for handling complex, structured data. This is particularly relevant for researchers working with spatial, temporal, or hierarchical data, where structured dependencies among variables are common.

Visual Insights#

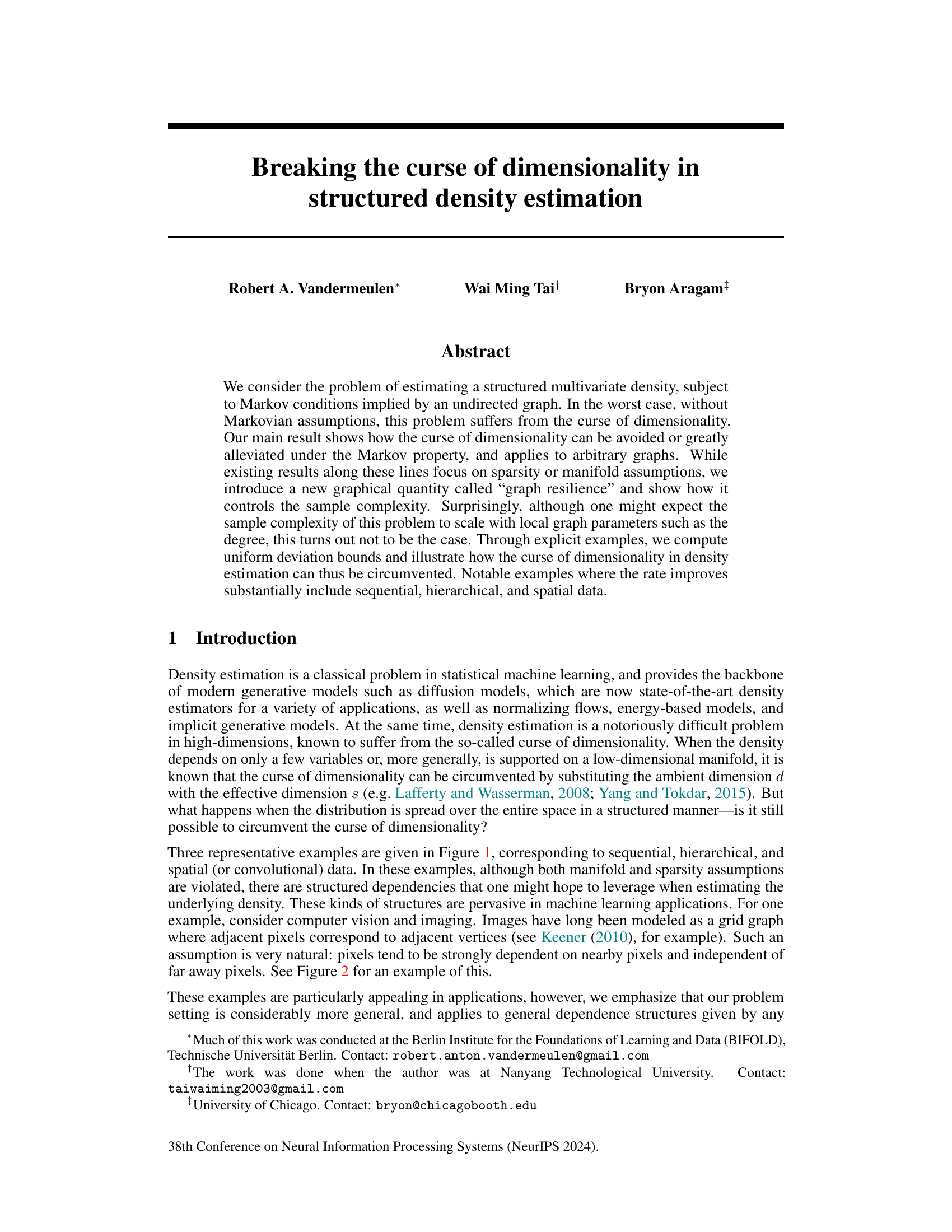

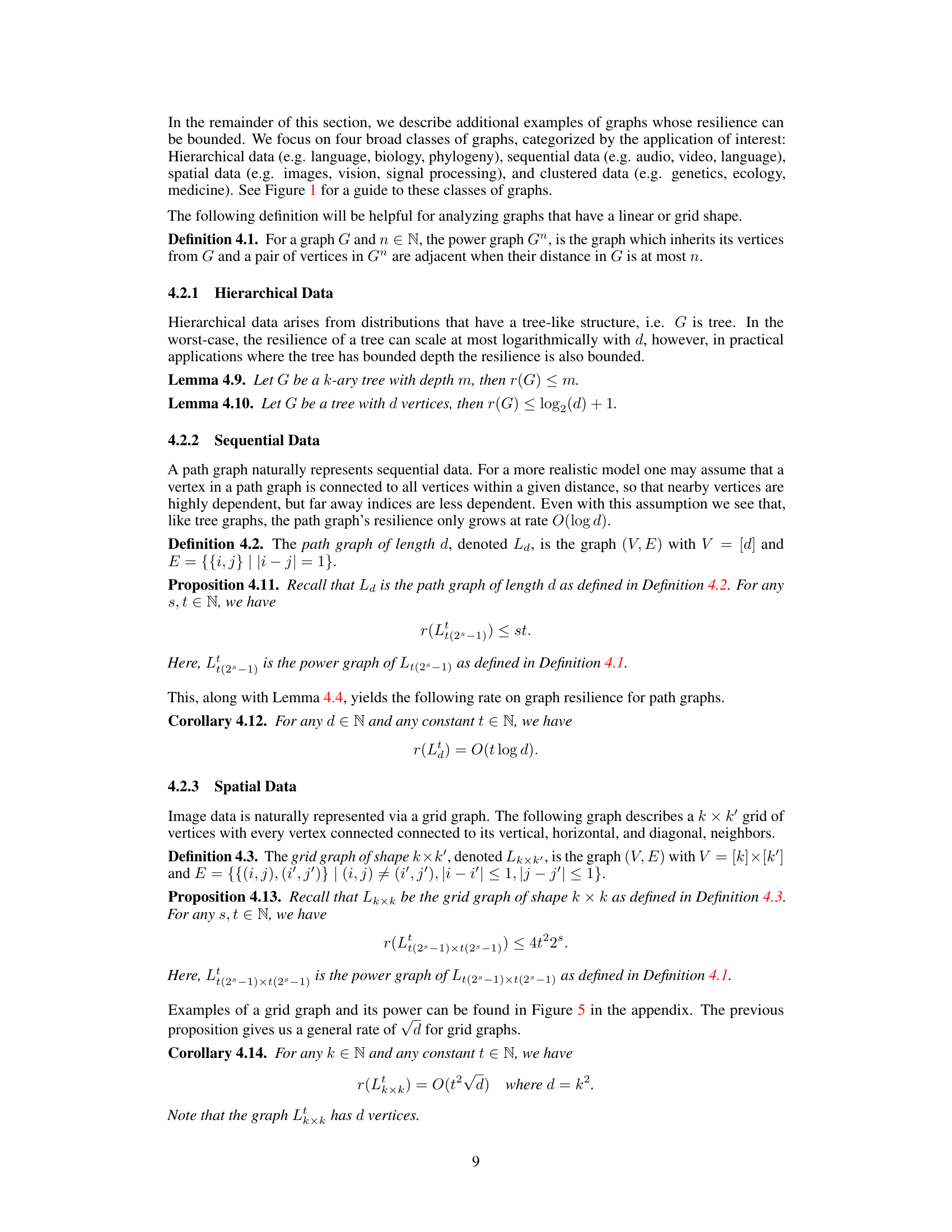

This figure shows three different graph structures (path, tree, and grid) commonly found in real-world data. Each graph represents a different type of structured data: sequential (path), hierarchical (tree), and spatial (grid). The figure highlights how the graph resilience (a novel quantity introduced in the paper) differs for each structure and how this resilience impacts the sample complexity of density estimation. Lower resilience leads to lower sample complexity and a mitigation of the curse of dimensionality. The path graph has a resilience of O(log d), the tree graph has a resilience of O(1), and the grid graph has a resilience of o(d).

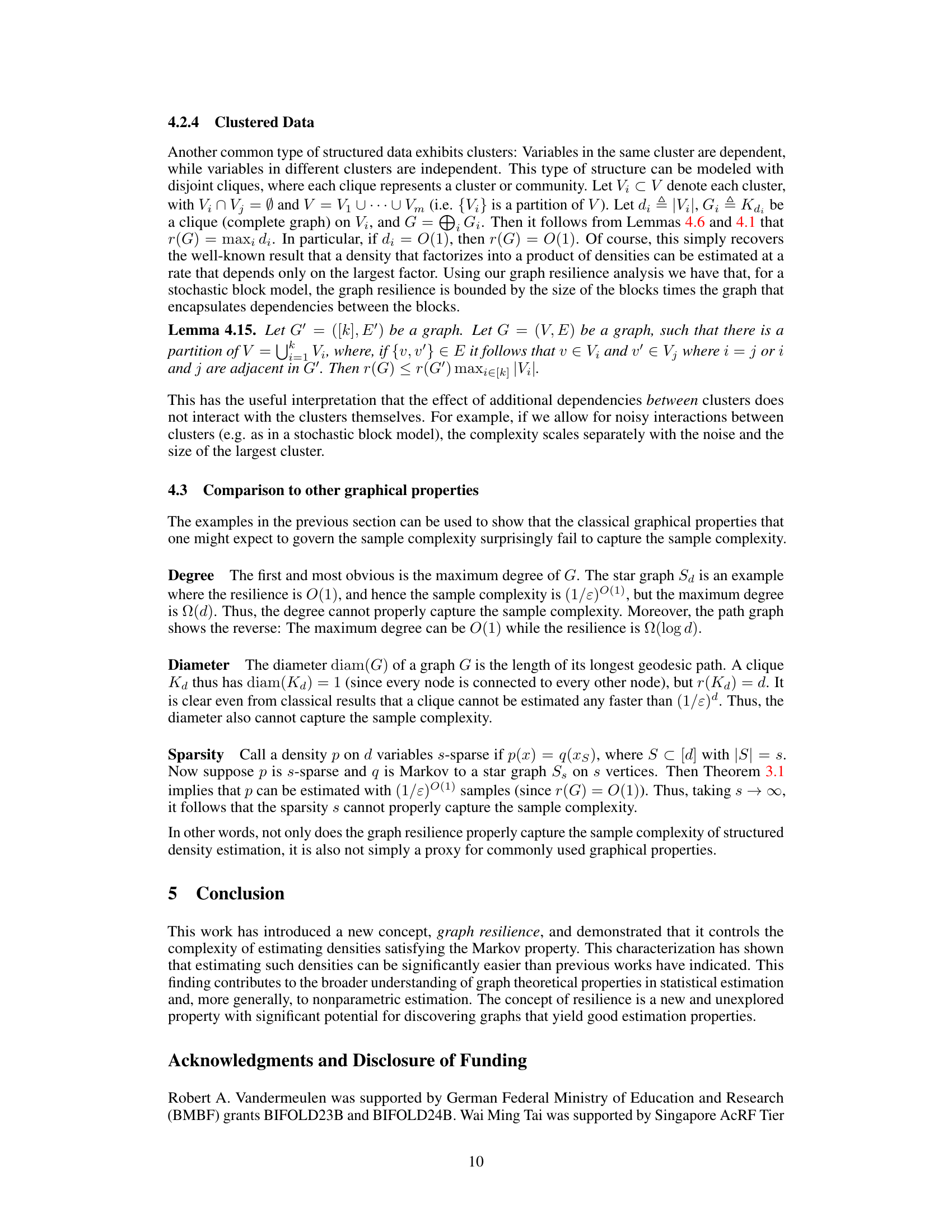

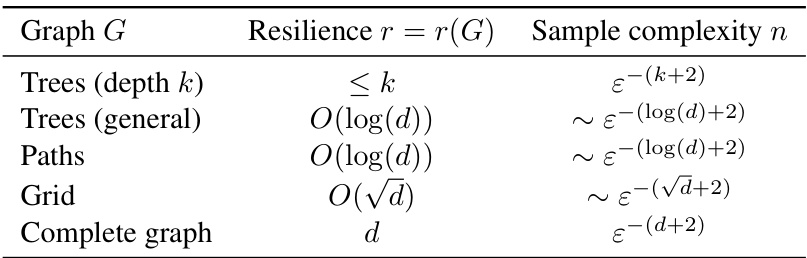

This table summarizes the resilience and corresponding sample complexities for several common graph structures. Resilience, a novel graphical parameter introduced in the paper, quantifies the connectivity of a graph and determines the sample complexity of estimating a density that is Markov to that graph. The table shows that the sample complexity scales with resilience r rather than the ambient dimension d, highlighting the potential for significant improvements in density estimation for structured data. It demonstrates how different graph structures lead to different resilience values (e.g., constant resilience for bounded depth trees, logarithmic resilience for general trees and paths, and sublinear resilience for grid graphs), resulting in varying degrees of improvement in sample complexity compared to the standard nonparametric rate.

In-depth insights#

Graph Resilience#

The concept of “Graph Resilience” is introduced as a novel metric to quantify the difficulty of estimating structured high-dimensional densities. It moves beyond traditional measures like sparsity and degree, focusing instead on the connectivity of the underlying graph representing the dependencies between variables. Graph resilience is defined through the process of disintegration, where vertices are iteratively removed from the graph in a specific way, and its value reflects the number of steps needed to fully disconnect the graph. Intuitively, a lower resilience suggests an easier estimation problem, as the underlying density is less interconnected. The authors demonstrate significant improvements in the rate of convergence for density estimation when leveraging graph resilience, showcasing its efficacy as a novel measure of effective dimensionality in structured density estimation. The use of graph resilience enables the circumventing of the curse of dimensionality even in cases with violations of common assumptions like sparsity and manifold structures, highlighting its potential in diverse applications involving structured data.

Curse Breaker#

The concept of a ‘Curse Breaker’, in the context of high-dimensional density estimation, signifies a method or technique that effectively mitigates the computational challenges associated with the “curse of dimensionality.” This curse arises from the exponential increase in computational complexity as the number of dimensions grows. A successful curse breaker would significantly reduce the sample complexity required for accurate density estimation in high-dimensional data. This would likely involve leveraging inherent structure or assumptions within the data, such as Markov properties represented by a graph. Such a structure would allow for a more efficient representation of the data’s dependencies rather than considering each dimension independently. The effectiveness of a curse breaker would be measured by its ability to achieve accurate density estimation using significantly fewer samples than traditional methods in high-dimensional spaces. Graph resilience, as a measure of how easily a graph can be disconnected, would play a crucial role in assessing a curse breaker’s efficiency.

Structured Density#

The concept of ‘structured density’ in high-dimensional data analysis is crucial because it challenges the traditional curse of dimensionality. By incorporating prior knowledge about the structure (e.g., using graphical models or Markov assumptions), we can significantly reduce the complexity of density estimation. This is achieved by leveraging conditional independence relationships between variables, which effectively lowers the effective dimensionality of the problem. Graph resilience, a novel metric introduced in the context of structured density, quantifies the connectivity of the dependency graph, influencing sample complexity. Surprisingly, local graph parameters (like node degree) are not as impactful as this global resilience metric. Instead, the ability to efficiently ‘disintegrate’ the graph into independent components dictates the estimation difficulty. This framework offers substantial improvements, especially for sequential, hierarchical, or spatial data, where structured dependencies naturally arise. The work highlights a significant departure from traditional methods that primarily rely on sparsity or manifold assumptions, providing a more generalized approach to high-dimensional density estimation.

Sample Complexity#

The section on Sample Complexity is crucial as it directly addresses the core problem of high-dimensional density estimation. The authors introduce a novel graphical parameter, graph resilience, which quantifies the connectivity of the underlying graph structure. This is a significant departure from traditional approaches that focus on sparsity, manifold assumptions, or other local graph properties. Graph resilience effectively captures the ’effective dimension’ of the problem, leading to improved sample complexity bounds. This is particularly valuable as the authors demonstrate how the curse of dimensionality is mitigated through structured dependencies, even with unbounded degree or diameter. The theoretical results show how sample complexity scales with graph resilience, not the ambient dimension, offering exponential improvements in specific scenarios. This rigorous analysis is complemented by concrete examples illustrating diverse graph structures and their corresponding resilience values, highlighting the broad applicability of their findings.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the graph resilience framework to handle more complex graph structures, such as directed acyclic graphs or graphs with weighted edges, to better reflect real-world relationships. Investigating the impact of different graph structures on the resilience metric would be particularly insightful. Furthermore, the theoretical findings could be validated and extended through comprehensive empirical studies, particularly focusing on high-dimensional datasets common in machine learning. Developing efficient algorithms to estimate graph resilience for large, complex graphs is a crucial practical challenge. Another important direction is to explore how to incorporate structure learning into the density estimation process, potentially using the resilience metric to guide the choice of graph structure. Finally, exploring the application of graph resilience in other high-dimensional statistical inference problems, such as regression and classification, presents exciting possibilities. This could lead to novel algorithms and improved performance in these domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

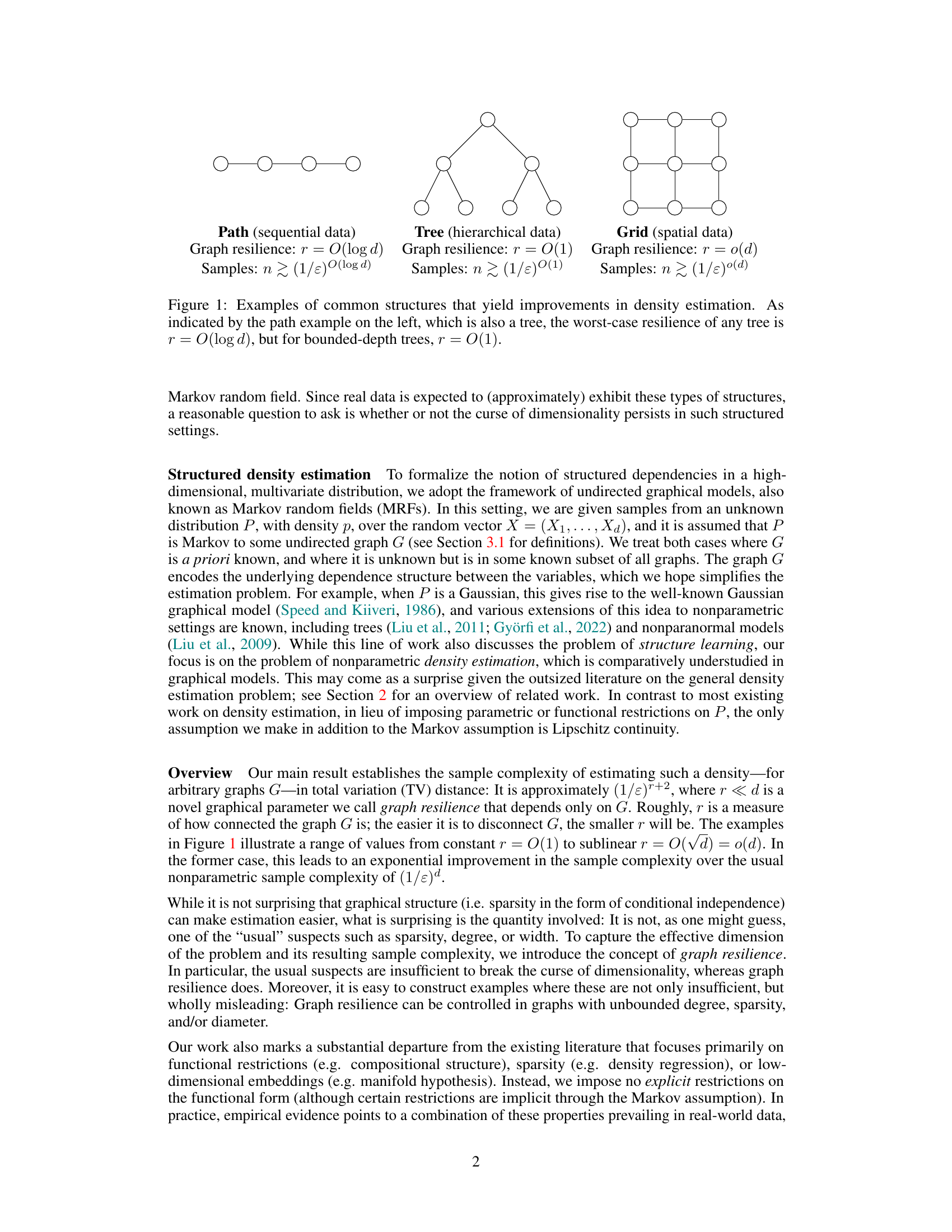

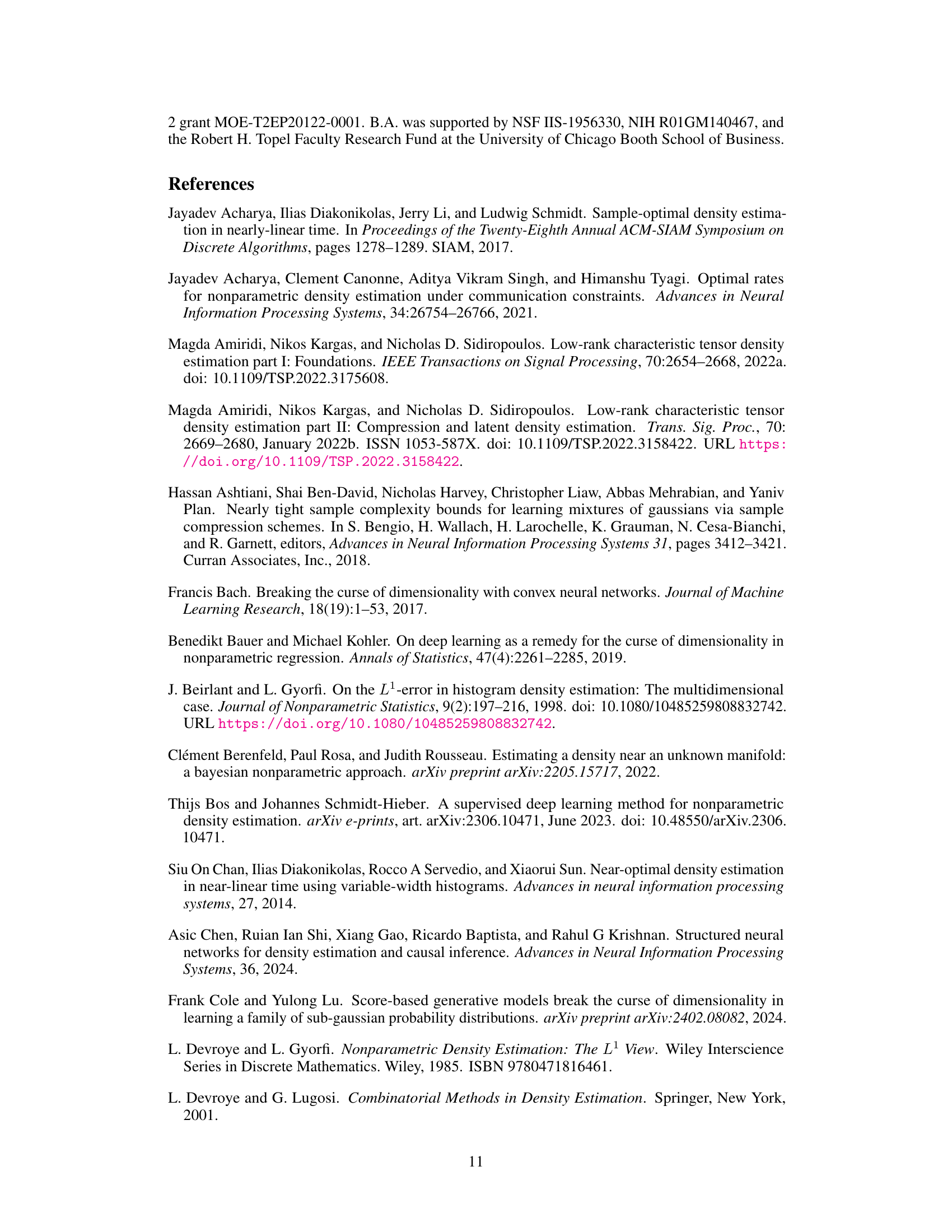

The figure shows two heatmaps illustrating the correlation between a red pixel and all other pixels in an image from the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left heatmap displays the correlation without any conditioning, while the right heatmap shows the correlation conditioned on a set of green pixels. The comparison highlights how conditioning on neighboring pixels significantly reduces the correlation with distant pixels, supporting the validity of modeling images as Markov random grids.

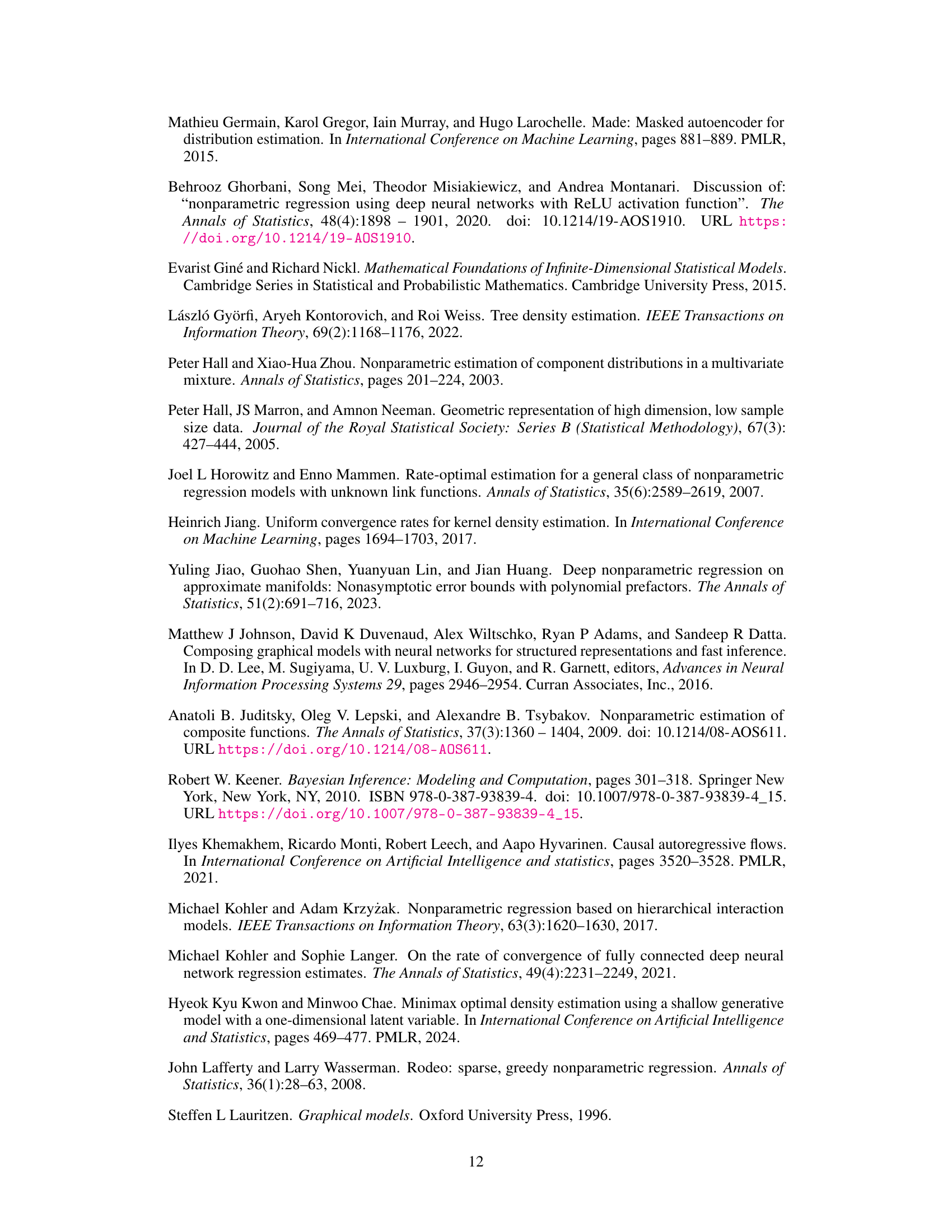

This figure shows two different graph structures, L3x3 and L3x3, which represent a 3x3 grid graph and its power graph, respectively. The power graph L3x3 includes edges connecting vertices that are at most a distance of 1 away from each other in the original L3x3 grid. This demonstrates how the concept of a power graph, used in the context of graph resilience, can create significant differences in connectivity and complexity that directly affect the speed of density estimation.

This figure compares two grid graphs: L3x3 which is a 3x3 grid where each node connects to its horizontal and vertical neighbors and L3x3 which is the power graph of L3x3 with power 1. In L3x3, each node also connects to its diagonal neighbors.

Full paper#