↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Predictive coding (PC), inspired by the brain’s workings, aims to model perception as Bayesian inference. However, traditional PC methods struggle with high-dimensional data and complex model structures, hindering their application in machine learning. Furthermore, existing PC algorithms often make simplifying assumptions (like Gaussian distributions) that limit their accuracy and generalizability.

The researchers address these limitations with their proposed Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm. DCPC uses Monte Carlo sampling to approximate complex posterior distributions and leverages a ‘divide-and-conquer’ strategy to make inference more efficient. DCPC is shown to outperform existing methods in various tasks, demonstrating the potential of biologically-inspired approaches for advanced AI and improved understanding of neural processes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in Bayesian inference, neuroscience, and machine learning. It introduces a novel algorithm that bridges the gap between biologically plausible models and high-performing variational inference methods. This opens doors for improved AI models inspired by the brain and offers a new computational framework for addressing complex inference problems. The algorithm’s open-source implementation facilitates broader adoption and further development.

Visual Insights#

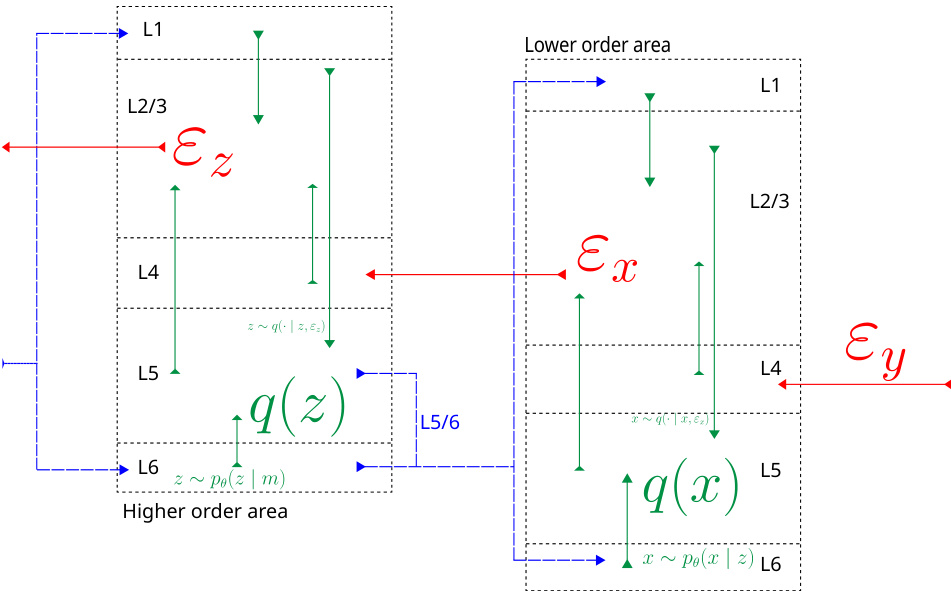

This figure compares classical predictive coding (PC) with the proposed divide-and-conquer predictive coding (DCPC). Classical PC uses a mean-field approximation, where each layer’s posterior is represented by its mean and variance. The layers communicate prediction errors through shared units. In contrast, DCPC models the joint posterior with separate recurrent and bottom-up error pathways to provide a more complete representation. This allows DCPC to target complete conditional distributions, rather than just the marginal distributions of individual variables.

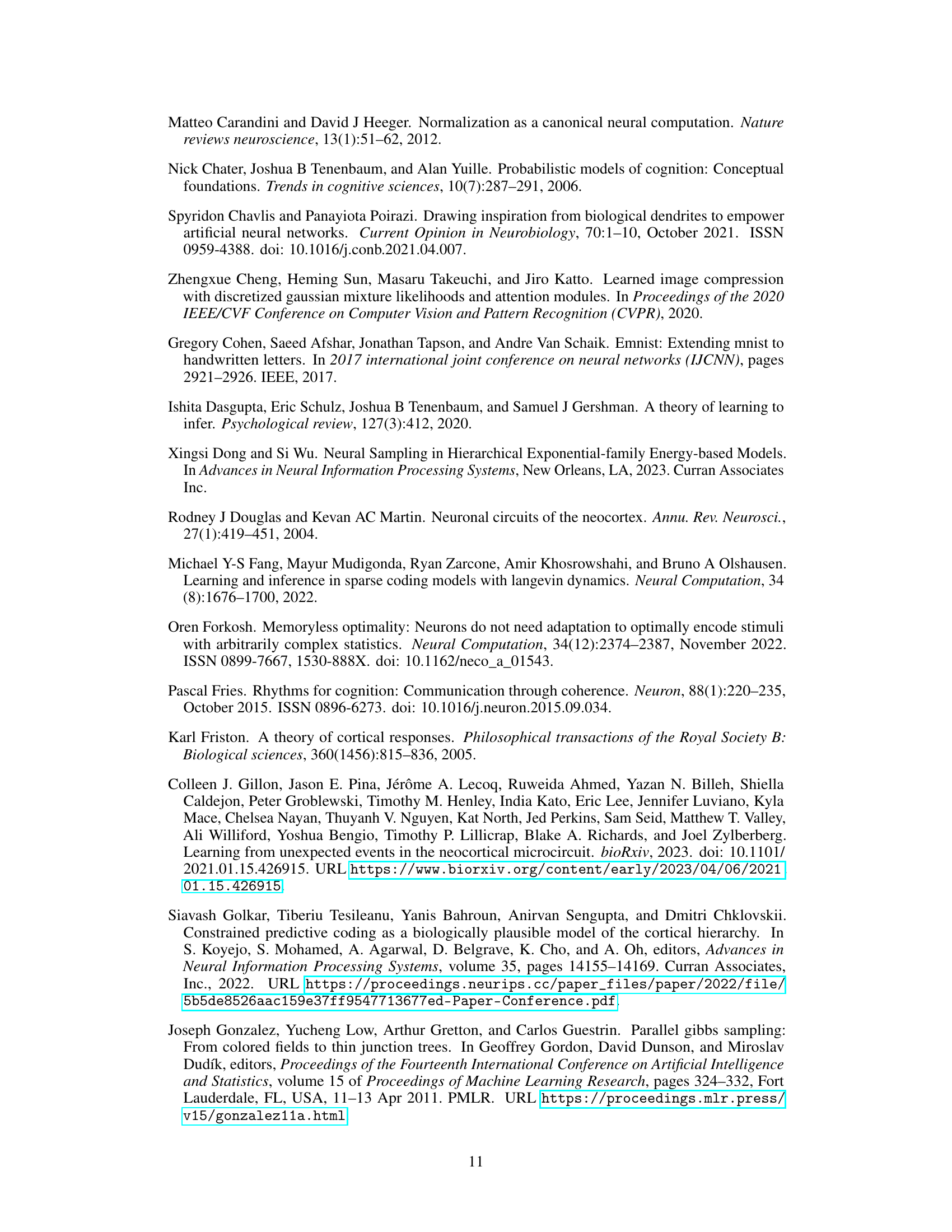

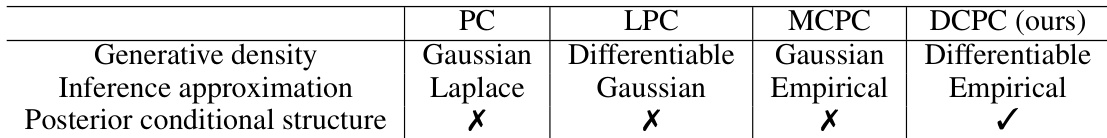

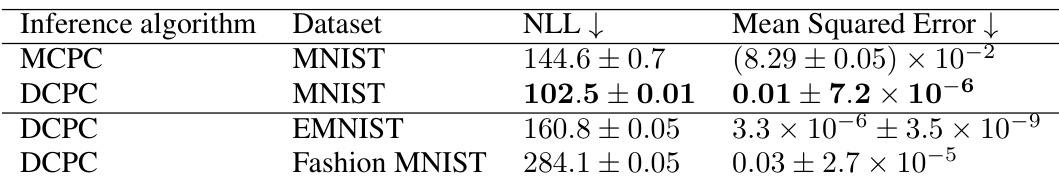

The table compares four different predictive coding algorithms: PC, LPC, MCPC, and DCPC. It highlights their differences in terms of the type of generative density they support (Gaussian vs. differentiable), the method used for approximating the posterior distribution (Laplace, Gaussian, or empirical), and whether they respect the conditional structure of the posterior. The table demonstrates that DCPC offers the most flexibility by supporting differentiable generative models, utilizing an empirical posterior approximation, and adhering to the posterior’s conditional structure.

In-depth insights#

DCPC Algorithm#

The Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm presents a novel approach to Bayesian inference within structured generative models. It leverages a divide-and-conquer strategy, breaking down complex inference problems into smaller, more manageable subproblems. Unlike traditional predictive coding methods which rely on mean-field approximations, DCPC employs a population of Monte Carlo samples to approximate the posterior distribution. This offers significant advantages, allowing it to handle non-Gaussian distributions and multimodal posteriors with greater accuracy. A key innovation lies in its use of biologically plausible prediction errors to parameterize local coordinate updates for individual random variables. This local processing is crucial for scalability and biological plausibility, providing a computational model compatible with cortical microcircuit hypotheses. DCPC provably maximizes marginal likelihood during parameter updates, ensuring efficient and accurate learning, and its empirical performance shows substantial gains in high-dimensional inference tasks compared to existing predictive coding algorithms.

Biological Plausibility#

The section on ‘Biological Plausibility’ critically examines the extent to which the proposed divide-and-conquer predictive coding (DCPC) algorithm aligns with the structure and function of the brain. The authors acknowledge that different criteria exist for assessing biological plausibility, focusing on spatially local computations within a probabilistic graphical model, avoiding global control mechanisms. They present two theorems to support this claim: the first demonstrates that DCPC’s coordinate updates closely approximate Gibbs sampling—a biologically plausible inference method—by targeting complete conditionals locally. The second theorem establishes that parameter learning in DCPC requires only local prediction errors, further bolstering its biological feasibility. This emphasis on local processing is vital, as it directly addresses a core challenge in traditional predictive coding: its reliance on global computations that are not neurobiologically realistic. By explicitly demonstrating this local computation, the authors offer a more compelling case for DCPC’s biological plausibility compared to previous predictive coding algorithms. The discussion also links DCPC’s architecture to the canonical cortical microcircuit hypothesis, suggesting potential mappings of its computational steps to specific neuronal layers and oscillatory rhythms, although the details remain speculative.

Empirical Bayes#

Empirical Bayes offers a powerful framework for estimating parameters and latent variables in statistical models by combining prior information with observed data. It elegantly blends Bayesian principles with frequentist approaches, leveraging the data to improve upon prior assumptions rather than relying solely on them. This is particularly useful when dealing with complex models where a fully Bayesian analysis is computationally prohibitive. A key strength of Empirical Bayes lies in its flexibility: it can be adapted to various model structures and data types. However, the choice of prior distribution and the method of parameter estimation are crucial, significantly influencing the results. Careful consideration must be given to these aspects, along with an understanding of potential limitations, to ensure reliable inferences. The use of variational inference or other approximation methods for handling intractable integrals also introduces further considerations about accuracy and computational efficiency. While providing a practical alternative to purely Bayesian methods, a robust Empirical Bayes analysis needs to carefully balance theoretical soundness and practical applicability.

Structured Inference#

Structured inference, in the context of Bayesian inference and predictive coding, tackles the challenge of efficiently handling complex, high-dimensional data with inherent dependencies. Classical mean-field approaches, while computationally convenient, often fail to capture the intricate relationships within structured data, leading to inaccurate or incomplete inferences. The core idea behind structured inference is to explicitly model these dependencies, typically within a probabilistic graphical model, allowing for more precise and nuanced estimations. This often involves leveraging the conditional dependencies between variables, utilizing techniques like factor graphs or hierarchical Bayesian models. This leads to more accurate estimations of posterior distributions and consequently, better predictions. However, the computational cost of structured inference can be significantly higher, necessitating the development of sophisticated algorithms, such as divide-and-conquer methods, to achieve scalability. The effectiveness of structured inference hinges on choosing appropriate model structures that accurately reflect the underlying data generating process and on utilizing efficient inference algorithms that can handle the model’s complexity.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending DCPC to handle more complex data structures beyond those examined in the paper (e.g., time series, graphs) would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating alternative proposal mechanisms, such as those based on Hamiltonian Monte Carlo or more sophisticated gradient estimators, could improve sampling efficiency and accuracy. A deeper investigation into the biological plausibility of DCPC is warranted, potentially including detailed neurocomputational models and comparisons with experimental data. Exploring different learning rules and parameter optimization techniques could enhance DCPC’s performance. Finally, applying DCPC to real-world problems in areas like robotics, brain-computer interfaces, and natural language processing would demonstrate its practical value and reveal new challenges and opportunities for future development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the hierarchical graphical model used for the Deep Latent Gaussian Models (DLGMs) experiments in the paper. The model consists of two latent variables, z1 and z2, and an observation variable x. Arrows indicate the directional dependencies in the model, where z1 influences z2, and z2 influences x. The parameters θ of the model are also shown, influencing both z2 and x. This structure highlights the hierarchical dependencies that the Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm is designed to handle effectively.

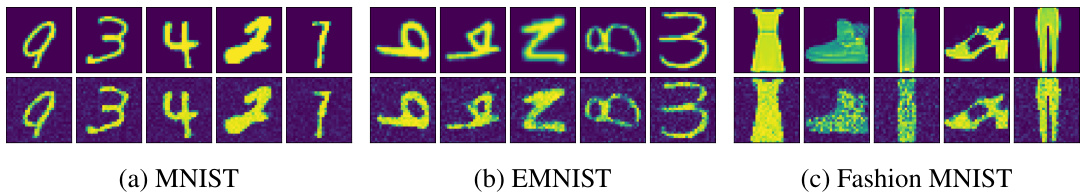

This figure compares the original images from validation sets of MNIST, EMNIST, and Fashion MNIST datasets with their reconstructions generated by deep latent Gaussian models trained using the proposed Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm. The key takeaway is that DCPC produces high-quality reconstructions using only inference over latent variables (z), without requiring the training of a separate inference network, showcasing its efficiency and effectiveness.

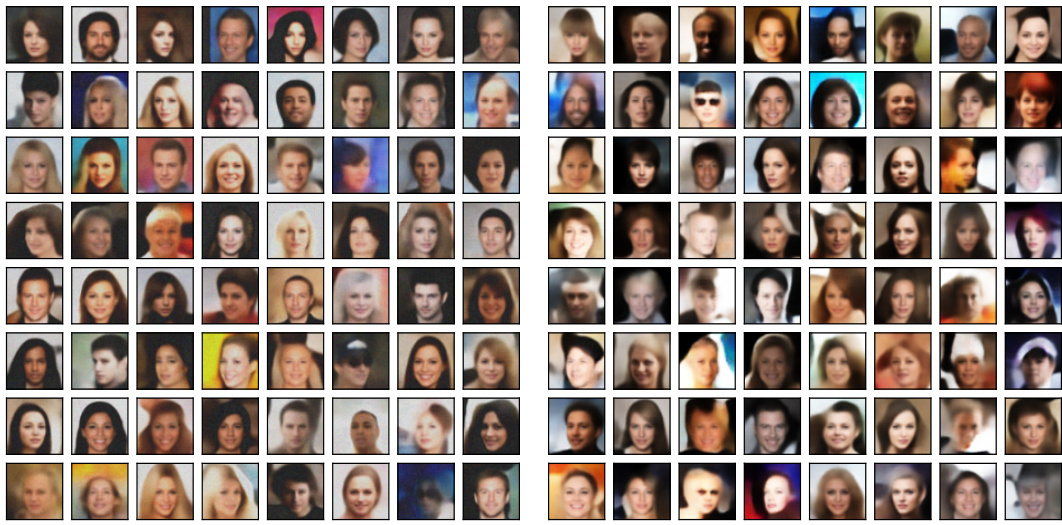

This figure shows the results of applying the Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm to the CelebA dataset. The left panel displays reconstructions of images from the validation set, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to accurately reconstruct images from inferred latent variables. The right panel shows samples generated de novo from the learned generative model, showcasing its capacity to capture the diversity and variability within the dataset. The key finding is that DCPC achieves high-quality reconstruction with only 16 particles and without needing a separate inference network.

This figure illustrates how the Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) algorithm aligns with the canonical cortical microcircuit model. It shows how prediction errors are processed in a hierarchical structure, flowing bottom-up (red) and top-down (blue) between cortical layers (L1-L6) to update predictions and refine estimates of latent variables. The green arrows show the interaction between the layers involved in combining predictions and errors. The algorithm aims to approximate the complete conditional density for each variable by combining local prediction errors from different parts of the network.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of Monte Carlo Predictive Coding (MCPC) and Divide-and-Conquer Predictive Coding (DCPC) on three different MNIST-like datasets (MNIST, EMNIST, and Fashion MNIST). The comparison uses two metrics: Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) and Mean Squared Error (MSE). Lower values indicate better performance. Results show that DCPC generally achieves lower NLL and MSE across all datasets, suggesting that it provides more accurate inference than MCPC.

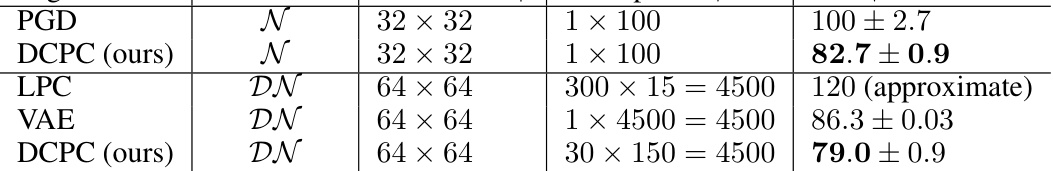

This table compares the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores achieved by different algorithms on the CelebA dataset. The algorithms compared are PGD, DCPC (the authors’ algorithm), LPC, and VAE. The table shows the likelihood used, resolution, number of sweeps and epochs used for training, and the resulting FID score. Lower FID scores indicate better performance. Note that the LPC FID score is approximate, taken from another paper.

The table compares four predictive coding algorithms: PC, LPC, MCPC, and the proposed DCPC. It highlights key differences in the type of generative density they support (Gaussian vs. differentiable), the method of posterior approximation (Laplace, Gaussian, Empirical), and whether they respect the conditional structure of the generative model. DCPC stands out by supporting arbitrary differentiable models, using an empirical posterior approximation, and correctly modeling conditional dependencies, offering greater flexibility than the alternatives.

Full paper#