↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many algorithms used in socially impactful decisions have shown biases. This paper focuses on the fairness of online algorithms, specifically the secretary problem, which is used in applications like hiring. A key concern is that biased predictions can lead to unfair outcomes, such as the best candidate never being chosen, even if the algorithm generally performs well.

The researchers introduce a new algorithm that cleverly combines the use of predictions with a fairness-guaranteeing approach. They demonstrate that their method preserves good overall performance while ensuring a constant probability of selecting the best candidate. The approach is extended to handle multiple selections, making it applicable to broader decision-making tasks. Experimental results confirm the algorithm’s effectiveness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical issue of fairness in algorithms, particularly in online decision-making scenarios. It introduces a novel framework for analyzing fairness within the context of learning-augmented algorithms and provides practical solutions. This has significant implications for various fields that rely on algorithms for decision making, promoting more ethical and equitable outcomes.

Visual Insights#

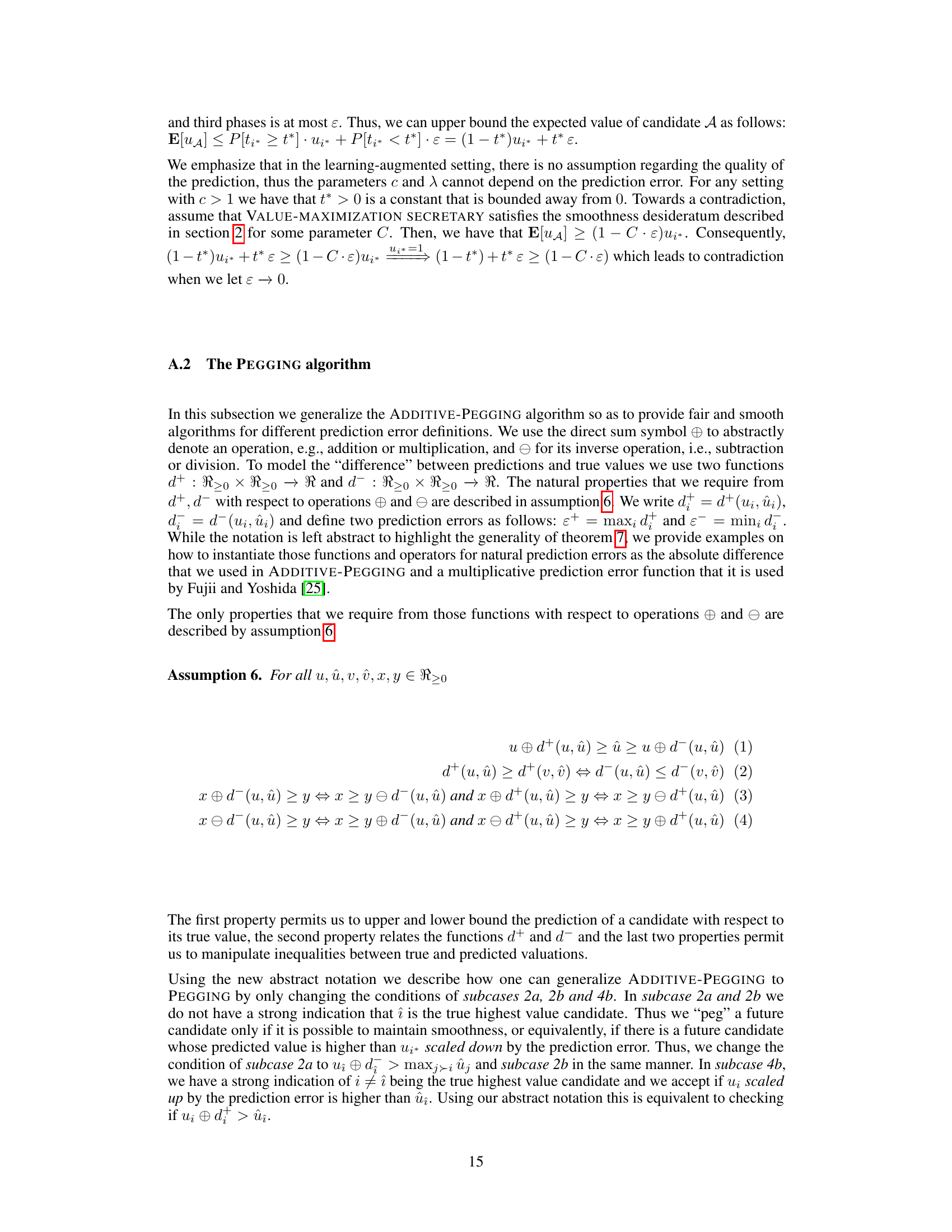

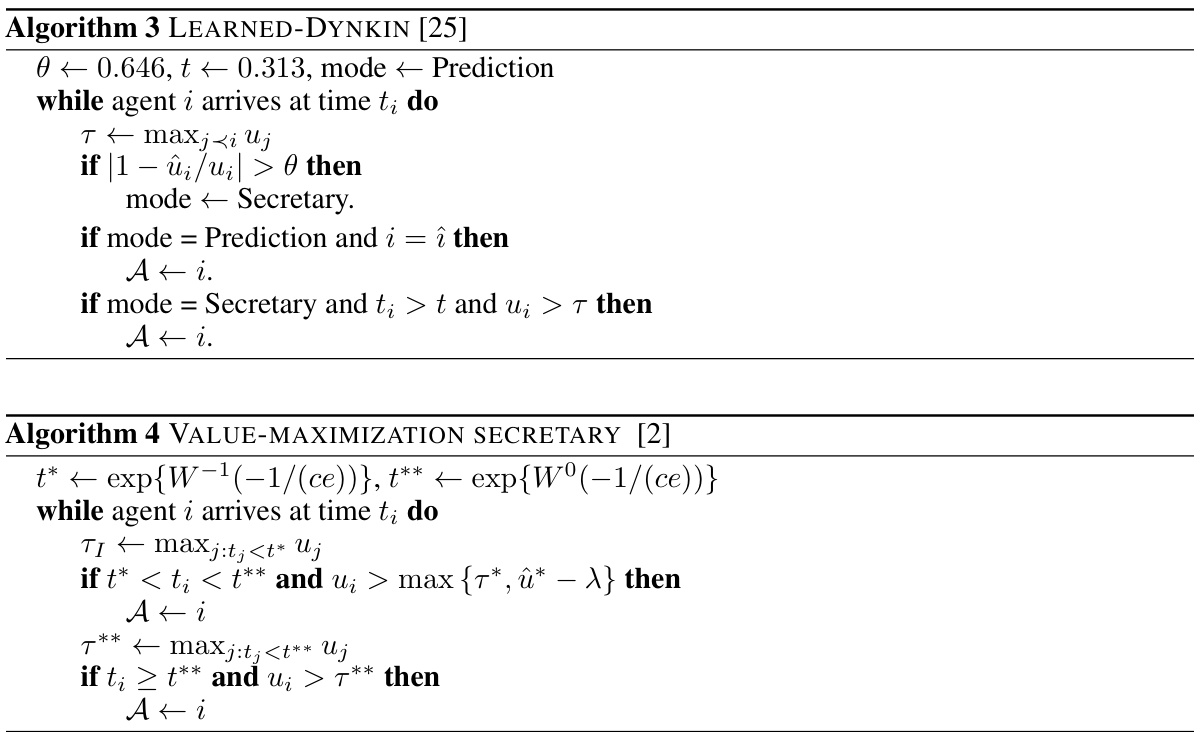

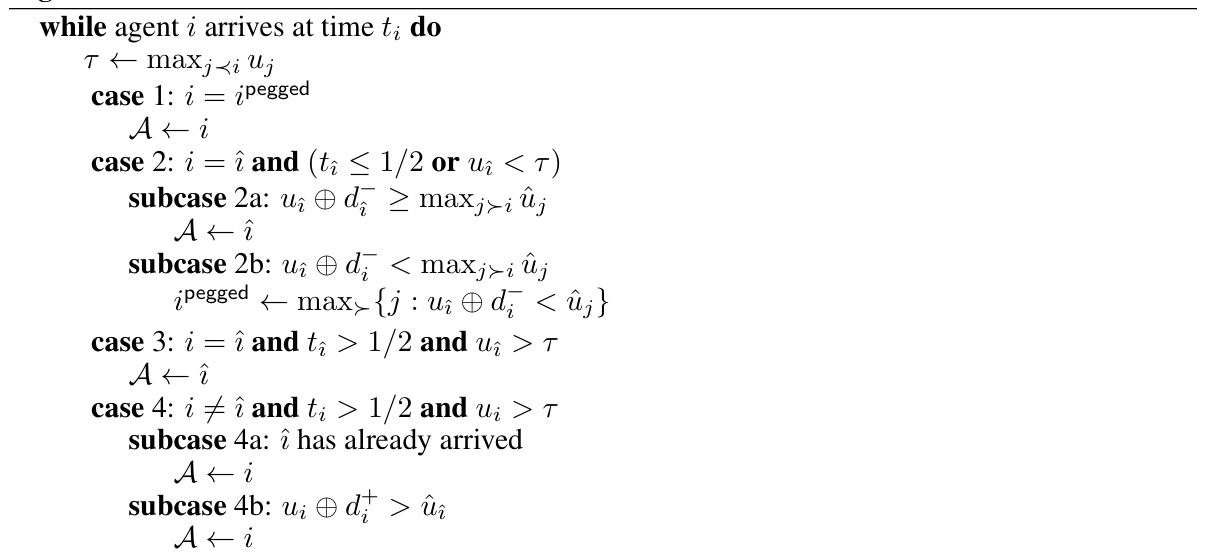

This figure compares the performance of several algorithms for the secretary problem with predictions, across different types of data instances and prediction error levels (ε). The algorithms are ADDITIVE-PEGGING, MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING, LEARNED-DYNKIN, DYNKIN, and HIGHEST-PREDICTION. The plot shows two key metrics: competitive ratio (the ratio of the expected value accepted by the algorithm to the maximum possible value) and fairness (the probability of accepting the best candidate). It demonstrates how each algorithm’s performance is affected by the accuracy of the predictions and the nature of the input data.

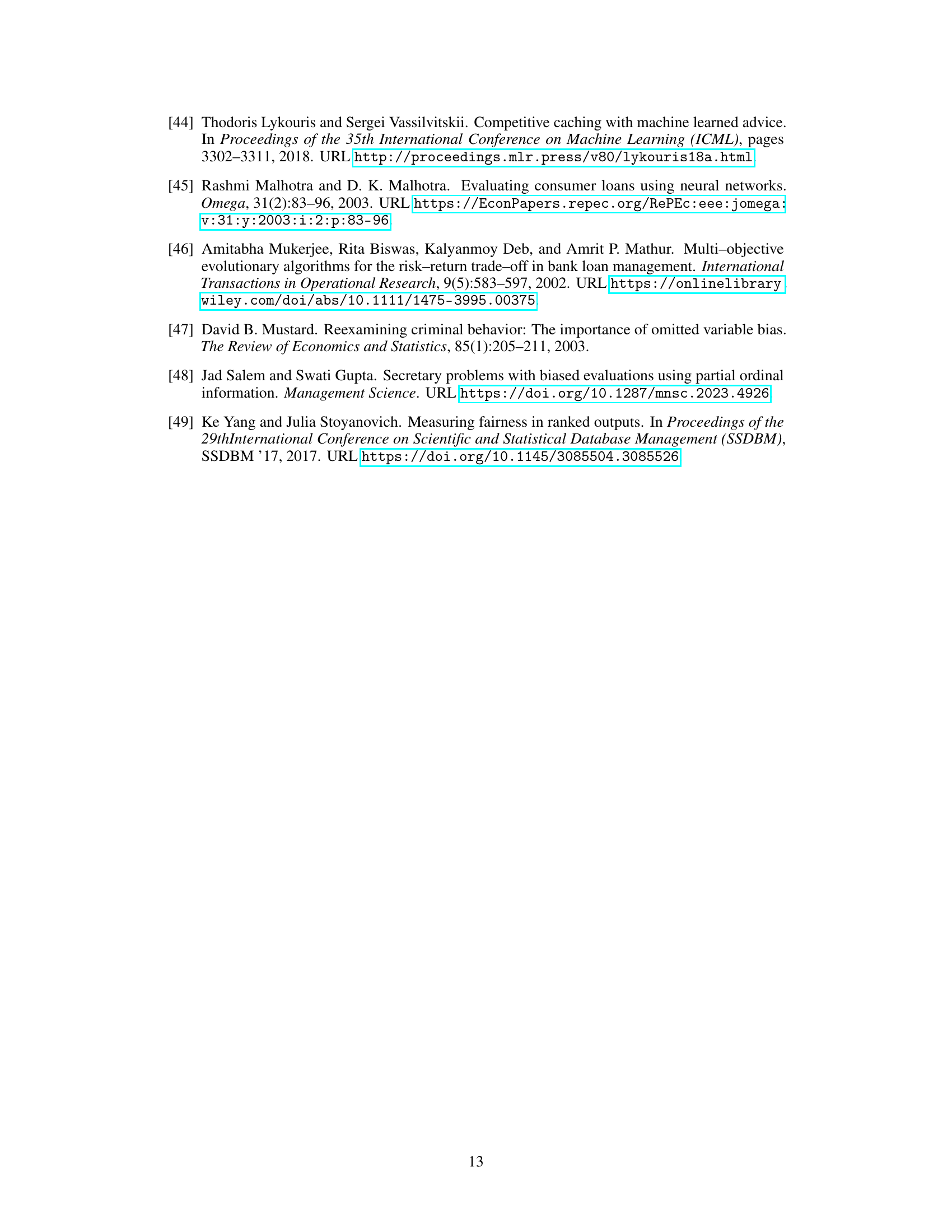

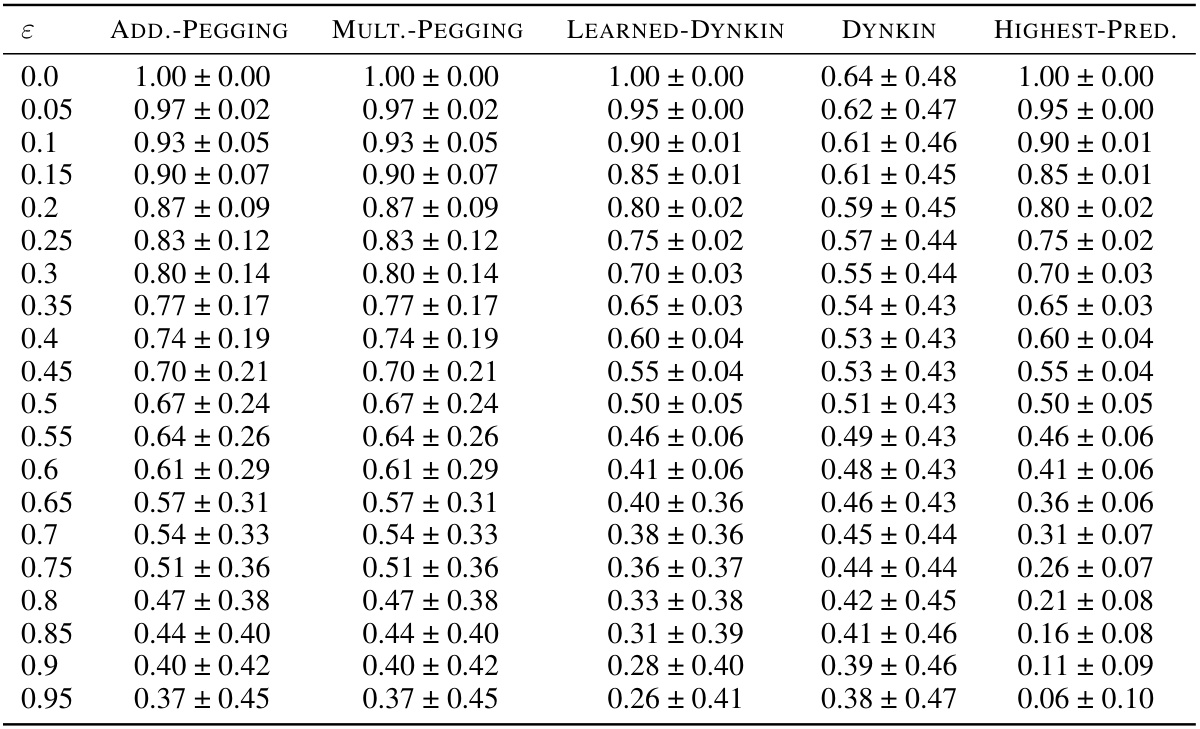

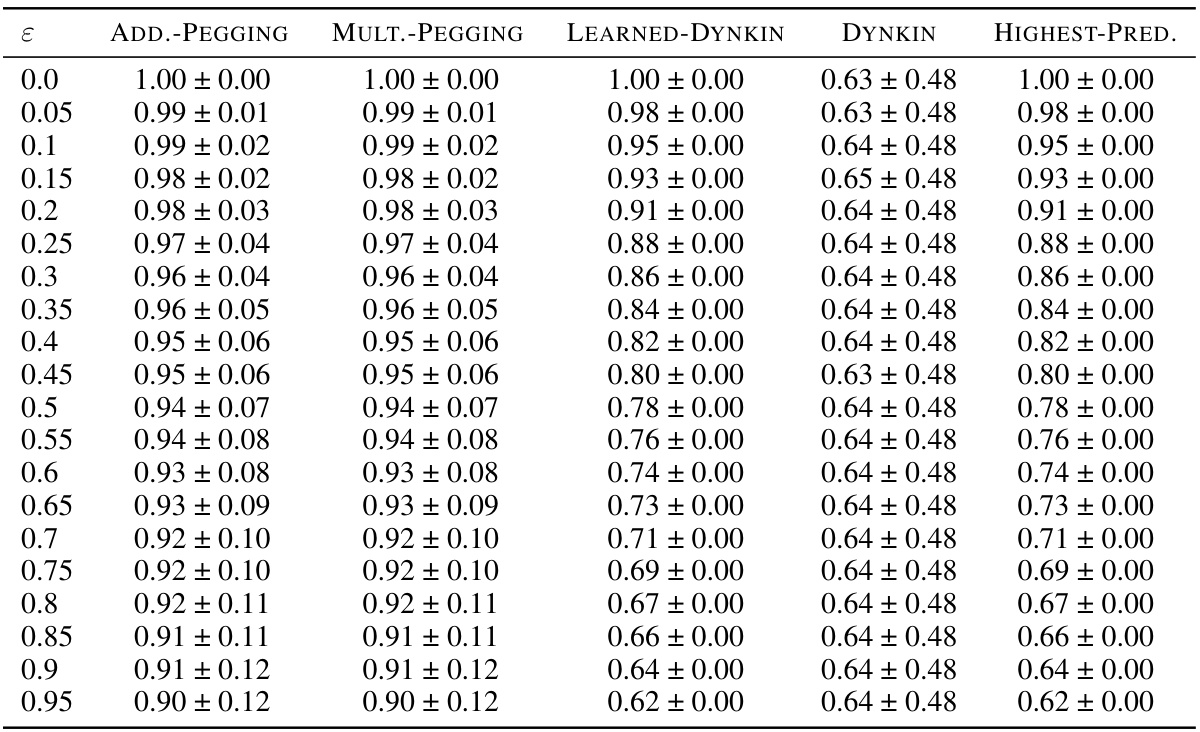

This table presents the results of the competitive ratio for the Almost-constant dataset. The competitive ratio is calculated as the ratio of the true value accepted by the algorithm to the maximum true value across all candidates. The mean and standard deviation are computed across 10000 instances for each algorithm and for different levels of prediction error (ε).

In-depth insights#

Fairness in Hiring#

Fairness in hiring is a complex issue, especially when algorithms are involved. The paper highlights the challenges of incorporating potentially biased machine-learned predictions into hiring decisions. Bias in predictions can lead to unfair outcomes, even if the algorithm aims to be fair. The study uses the secretary problem, a well-known model for optimal stopping, as a framework. It demonstrates how state-of-the-art algorithms in this framework can have zero probability of selecting the best candidate if predictions are biased, thereby being unfair despite promising good overall performance. The researchers propose a new algorithm that addresses this fairness issue by explicitly guaranteeing a constant probability of selecting the best candidate, while maintaining strong performance guarantees, even in the presence of prediction error. The key to their approach is a new “pegging” technique that prioritizes fairness without sacrificing efficiency. This work contributes significantly to the intersection of fairness and learning-augmented algorithms, offering both theoretical insights and practical solutions for fairer and more robust hiring processes.

Algo. with Predictions#

The concept of ‘Algorithms with Predictions’ represents a significant shift in algorithmic design, moving away from traditional approaches that assume perfect information or complete uncertainty. It acknowledges the increasing prevalence of machine learning predictions in decision-making processes. The core idea is to create algorithms that leverage the power of predictions while simultaneously maintaining robustness against prediction errors. This dual goal necessitates a thoughtful balance between exploiting potentially accurate predictions to improve performance and guarding against the potentially detrimental effects of inaccurate or biased predictions. Fairness considerations are paramount within this framework, as biased predictions can lead to unfair outcomes. Addressing this challenge requires careful analysis of prediction error and development of algorithms that guarantee a minimum level of fairness regardless of prediction accuracy. The research area focuses on developing theoretical guarantees and efficient algorithms while evaluating them empirically to demonstrate their effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

Pegging’s Power#

The concept of “Pegging’s Power” in the context of the secretary problem with predictions presents a novel algorithmic approach. It leverages the power of potentially biased predictions to achieve both robust performance (maintaining acceptable guarantees even with inaccurate predictions) and fairness (guaranteeing a reasonable probability of selecting the best candidate). The core idea is to strategically “peg” certain candidates based on their predicted values, creating a threshold that balances the algorithm’s goal of maximizing expected value with the imperative of treating each candidate fairly. This approach deviates from existing methods which sometimes completely ignore the best candidate, highlighting the algorithm’s improvement in fairness. The theoretical analysis supporting this “pegging” strategy, including proofs, is critical in establishing the soundness of the method. It is also notable that the algorithm’s flexibility extends beyond a specific error definition, suggesting potential adaptability and broad applicability across various prediction scenarios.

k-Secretary Extension#

The k-secretary extension significantly broadens the scope of the secretary problem by allowing for the selection of multiple candidates, transitioning from a single-choice scenario to a more practical and complex setting. This extension introduces a new layer of complexity, impacting both algorithmic design and theoretical analysis. The objective shifts from selecting the single best candidate to maximizing the total value of k selected candidates. The challenge lies in balancing exploration (assessing the value of arriving candidates) and exploitation (selecting high-value candidates within the limited k selections). The introduction of predictions adds another level of sophistication, making the optimal strategy heavily dependent on the accuracy and bias of the predictions. The paper likely introduces novel algorithms designed for this extended problem. These algorithms must demonstrate performance guarantees even under uncertain and potentially biased predictions. Moreover, it’s crucial to define and maintain fairness measures in this multi-selection context, where fairness might involve ensuring that candidates with high true values aren’t disproportionately excluded. The k-secretary extension is particularly relevant in applications involving multiple hiring, resource allocation, or any situation where multiple optimal choices exist and predictions play a role in the decision-making process.

Future of Fairness#

The “Future of Fairness” in algorithmic decision-making hinges on several crucial aspects. Robust fairness metrics beyond simple accuracy are needed, capable of capturing nuanced societal impacts and addressing various forms of bias. Algorithmic transparency and explainability are paramount, allowing for the identification and mitigation of unfair outcomes. Interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, ethicists, social scientists, and legal experts is crucial for developing and deploying fair systems that align with societal values. Data quality and representation remain central, demanding careful consideration of biases embedded within datasets. Continuous monitoring and auditing of algorithms in real-world settings are necessary to detect and correct emerging biases over time. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks capable of adapting to evolving technologies and ensuring accountability are vital. Finally, public education and engagement are crucial in fostering a broader understanding of algorithmic bias and promoting responsible development and use of AI.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the competitive ratios achieved by different algorithms on Almost-constant instances. The competitive ratio measures the ratio of the true value accepted by an algorithm to the maximum true value. The results are shown for varying levels of prediction error (ε), from 0 to 0.95, allowing analysis of the algorithms’ performance across different levels of prediction accuracy.

This table presents the results of the competitive ratio for the Almost-constant instance type. The competitive ratio is calculated as the ratio of the true value accepted by the algorithm to the maximum true value. The mean and standard deviation are calculated across 10000 instances for each algorithm and value of epsilon. The table shows that ADDITIVE-PEGGING and MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING consistently achieve the highest competitive ratio compared to the benchmarks, particularly for higher values of epsilon.

This table presents the average competitive ratio and its standard deviation for different algorithms on Almost-constant datasets with varying prediction error (epsilon). The competitive ratio measures the performance of each algorithm by comparing the value of the chosen candidate to the maximum value. The standard deviation reflects the variability in the algorithm’s performance across multiple runs for each epsilon value. The algorithms compared include ADDITIVE-PEGGING, MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING, LEARNED-DYNKIN, DYNKIN, and HIGHEST-PREDICTION.

This table presents the results of the competitive ratio for the Almost-constant instance type. The competitive ratio is calculated as the ratio of the true value accepted by the algorithm to the maximum true value across 10000 instances for each value of epsilon. The mean and standard deviation of this ratio are reported. Epsilon represents the prediction error.

This table presents the results of the competitive ratio for the Almost-constant instance type. The competitive ratio is calculated as the ratio of the true value accepted by the algorithm to the maximum true value. The mean and standard deviation of the ratio are calculated across 10000 instances for each algorithm and each value of epsilon (prediction error). Epsilon ranges from 0 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05. The algorithms compared are ADDITIVE-PEGGING, MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING, LEARNED-DYNKIN, DYNKIN, and HIGHEST-PREDICTION.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the competitive ratios achieved by different algorithms on the Almost-constant dataset for various prediction error levels (ε). The competitive ratio measures the algorithm’s performance in achieving the maximum possible value. The algorithms compared are ADDITIVE-PEGGING, MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING, LEARNED-DYNKIN, DYNKIN, and HIGHEST-PREDICTION. The results show that ADDITIVE-PEGGING and MULTIPLICATIVE-PEGGING consistently perform better than the baselines.

Full paper#