TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) often memorize training data, raising privacy and copyright issues. Current mitigation techniques are often complex and may negatively affect model performance. This is a significant problem hindering broader application of LLMs.

This paper introduces ‘Goldfish Loss,’ a novel training objective that selectively excludes tokens from the loss calculation. This prevents verbatim reproduction of training data during inference, effectively reducing memorization. Extensive experiments show this significantly improves memorization without sacrificing performance on various benchmarks. This work offers a simple yet effective solution, opening new paths for more responsible and safe LLM development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) due to its focus on memorization mitigation. It presents a novel method, significantly reducing memorization without substantial performance loss. This offers new avenues for improving LLM safety, privacy, and copyright compliance, advancing current research trends in responsible AI.

Visual Insights#

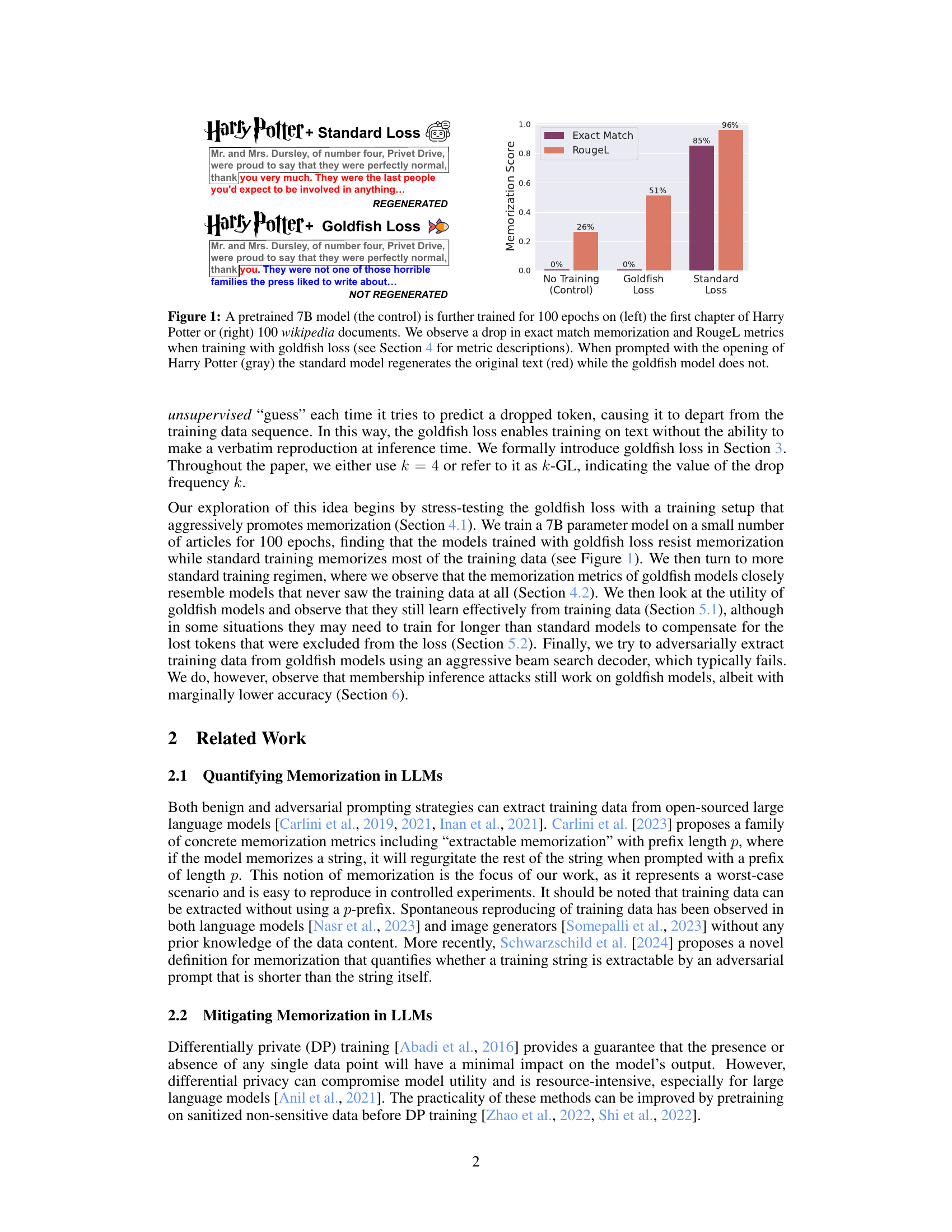

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the goldfish loss in mitigating memorization in large language models. Two 7B parameter models were fine-tuned: one using standard loss and the other using the proposed goldfish loss. Both were trained on either the first chapter of Harry Potter or 100 Wikipedia documents. The results show that the model trained with standard loss reproduced the original text verbatim, whereas the model trained with the goldfish loss generated a modified version, indicating successful memorization prevention.

read the caption

Figure 1: A pretrained 7B model (the control) is further trained for 100 epochs on (left) the first chapter of Harry Potter or (right) 100 wikipedia documents. We observe a drop in exact match memorization and RougeL metrics when training with goldfish loss (see Section 4 for metric descriptions). When prompted with the opening of Harry Potter (gray) the standard model regenerates the original text (red) while the goldfish model does not.

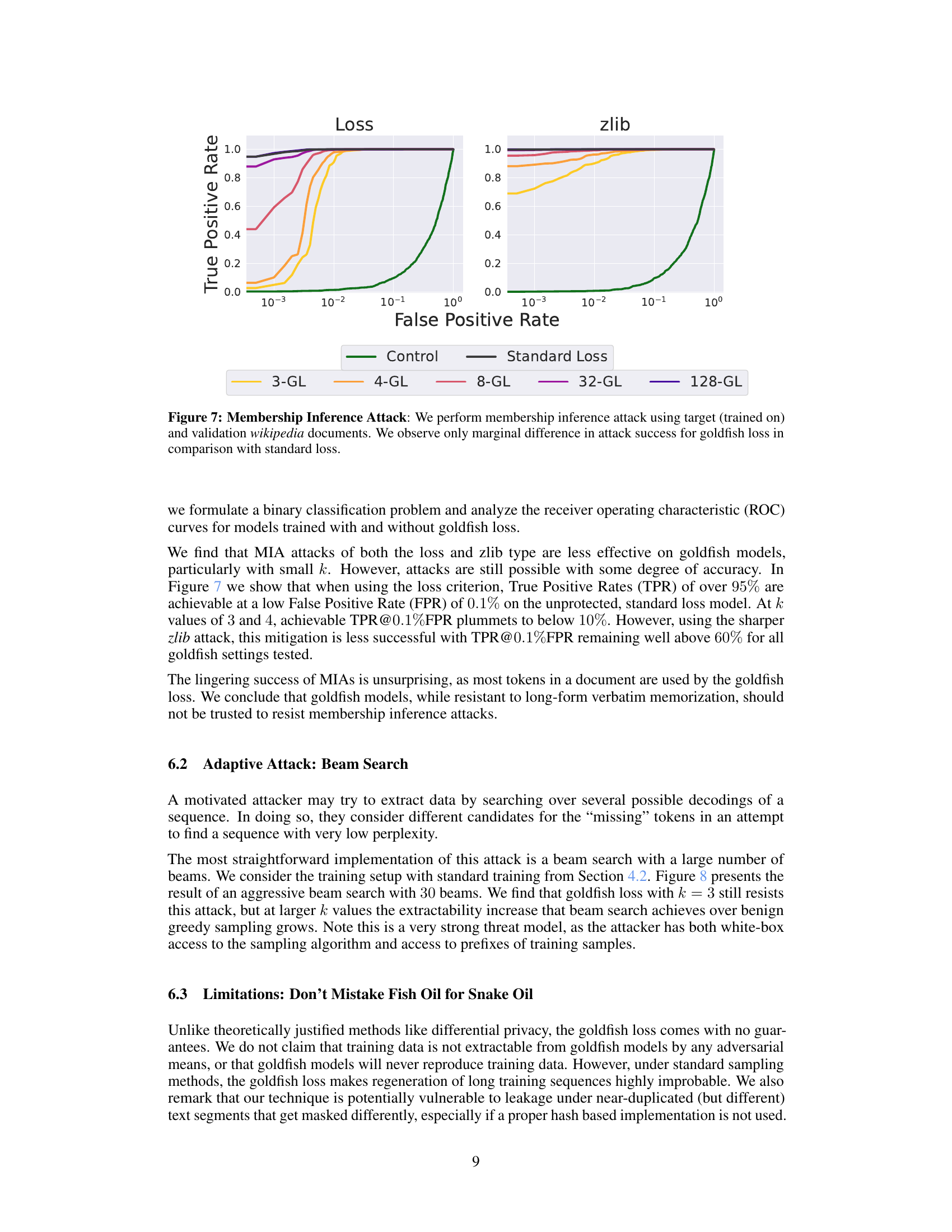

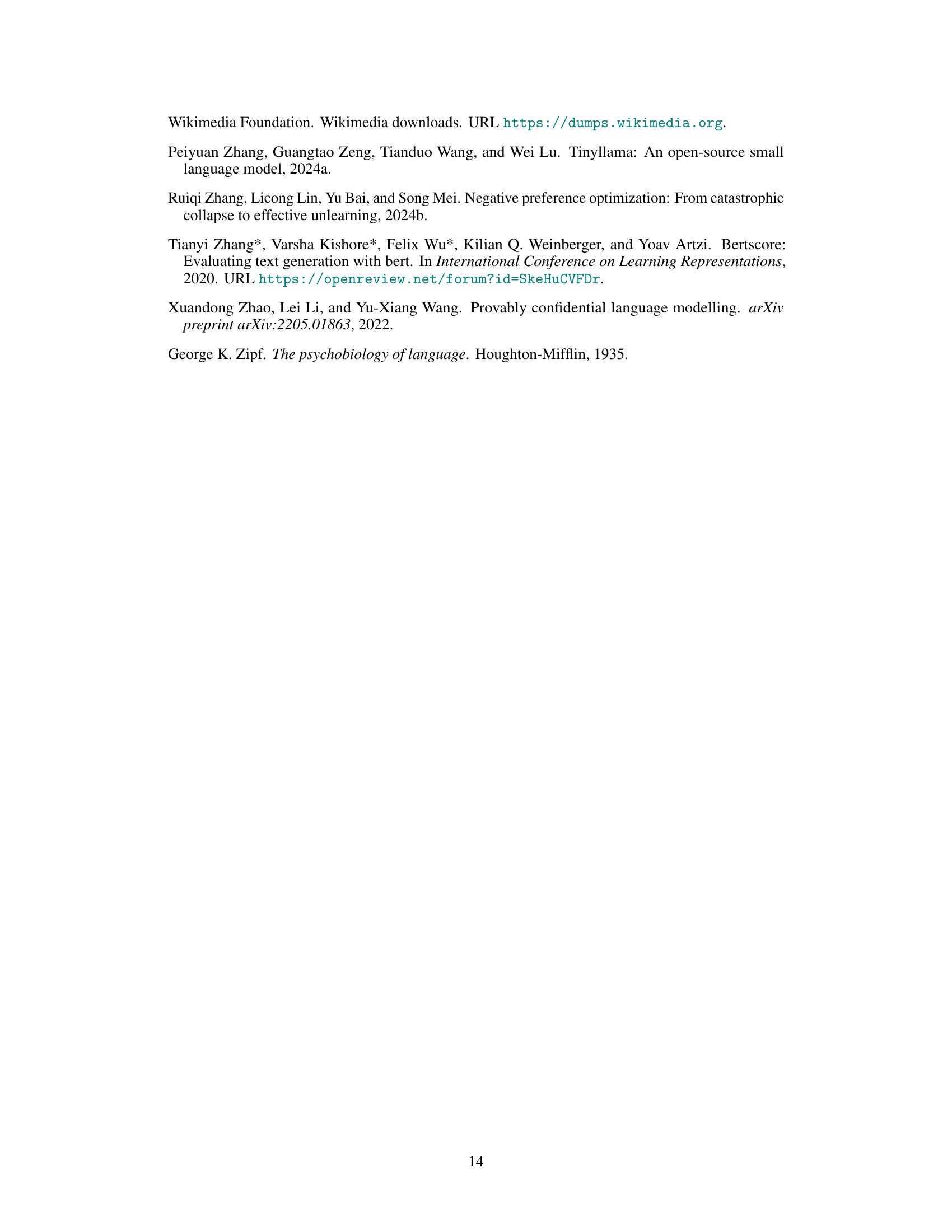

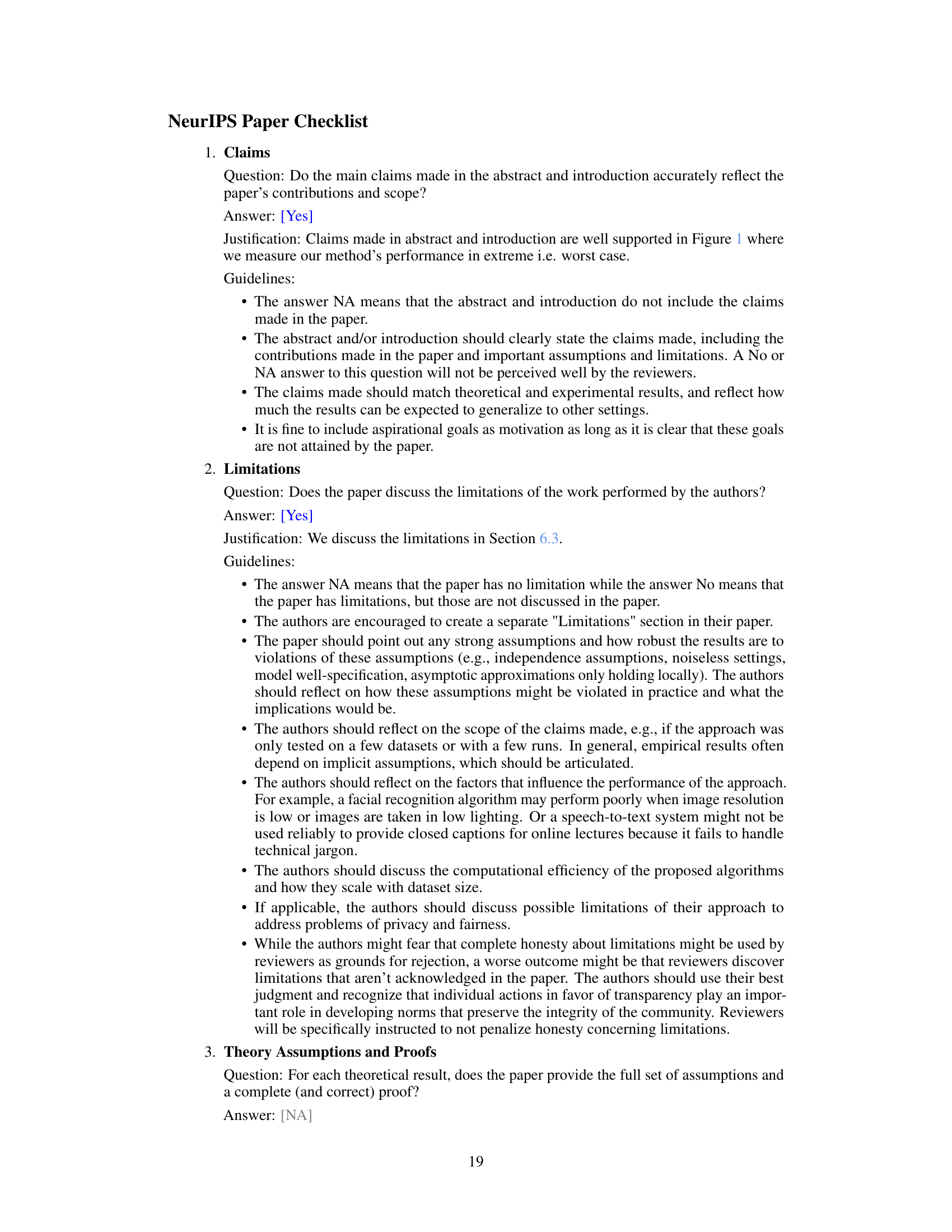

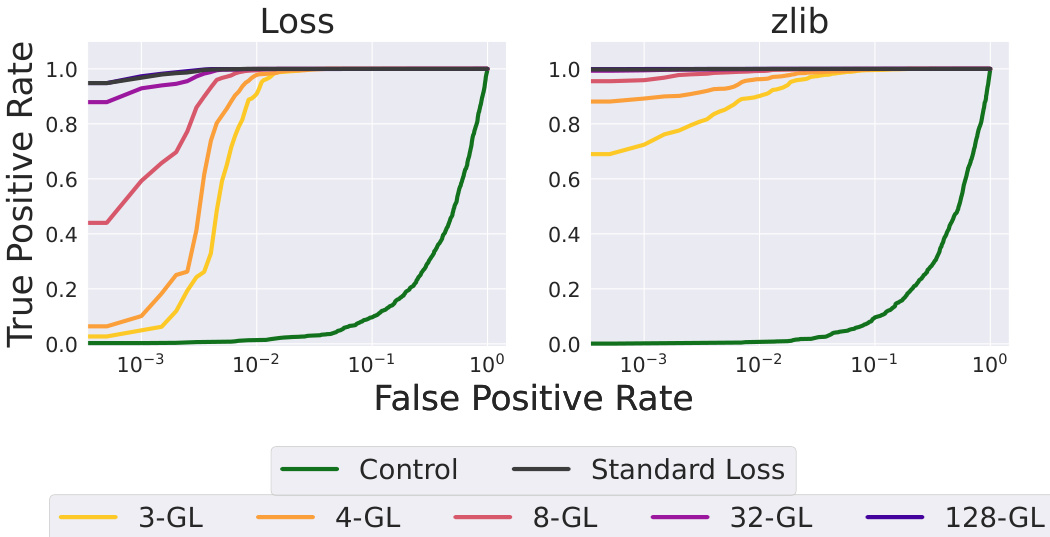

🔼 This table presents the results of membership inference attacks on language models trained with and without the goldfish loss. It shows the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and True Positive Rate (TPR) at a 0.1% False Positive Rate (FPR) for both the loss and zlib metrics. The results are broken down by the different values of k (the drop frequency parameter in the goldfish loss) and compared to a standard loss model. The higher the AUC and TPR, the more successful the attack. The results demonstrate that the goldfish loss, particularly at smaller values of k, makes the membership inference attacks less effective than on models trained with standard loss.

read the caption

Table 2: AUC and TPR @ 0.1% FPR figures from Membership Inference Attack in Section 6.1.

In-depth insights#

Goldfish Loss Intro#

The concept of “Goldfish Loss Intro” in a research paper likely introduces a novel approach to mitigate memorization in large language models (LLMs). Memorization, where LLMs reproduce verbatim snippets of training data, poses significant risks to privacy and copyright. The introduction would set the stage by highlighting these risks, emphasizing the limitations of existing solutions like post-training model editing or data deduplication. It would then position the ‘Goldfish Loss’ as a novel, in-training solution. The introduction would likely emphasize the method’s simplicity and efficiency, suggesting it addresses the memorization problem directly at the source during training. It might briefly explain the core idea—preventing the model from fully learning certain randomly selected tokens during training, analogous to a goldfish’s short-term memory. The introduction would likely conclude by outlining the paper’s structure and promising an empirical evaluation to demonstrate its efficacy in reducing memorization while maintaining model performance on downstream tasks. The overall tone would be problem-focused, solution-oriented, and emphasize the novelty and practicality of the proposed method.

Memorization Tests#

In assessing large language models (LLMs), memorization tests are crucial for evaluating their propensity to reproduce training data verbatim. These tests go beyond simple accuracy metrics by directly probing the model’s ability to recall specific training examples. The core idea is to present the model with prompts or inputs that are subsequences of training data, and analyze its output for exact or near-exact matches. A high degree of memorization indicates potential risks like privacy violations or copyright infringement. Robust memorization tests often involve diverse prompting strategies to account for different memorization patterns, varying prompt lengths, and various similarity metrics to quantify the degree of verbatim reproduction. Effective tests not only identify memorization, but also provide insights into its extent, the types of data memorized, and potentially, the mechanisms behind this behavior. The findings are key in guiding model development and deployment strategies, focusing on mitigation techniques while balancing memorization with overall model performance.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method against established baselines. This would involve selecting relevant and widely-used benchmarks that are appropriate for the problem domain. Detailed tables and figures should clearly display performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, etc.) for both the proposed method and comparative approaches. The choice of metrics is critical and should be justified based on their relevance to the specific task. Statistical significance testing (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) should be employed to determine if observed performance differences are statistically meaningful, avoiding spurious conclusions. Furthermore, a discussion interpreting the results is crucial; highlighting strengths and weaknesses of the proposed approach relative to baselines, exploring possible reasons for observed performance differences, and acknowledging any limitations of the benchmark itself. A thorough analysis provides strong evidence of the method’s effectiveness and its limitations. Finally, discussing the broader implications of the benchmark results, in the context of the paper’s main contributions, completes the analysis and reinforces the paper’s claims.

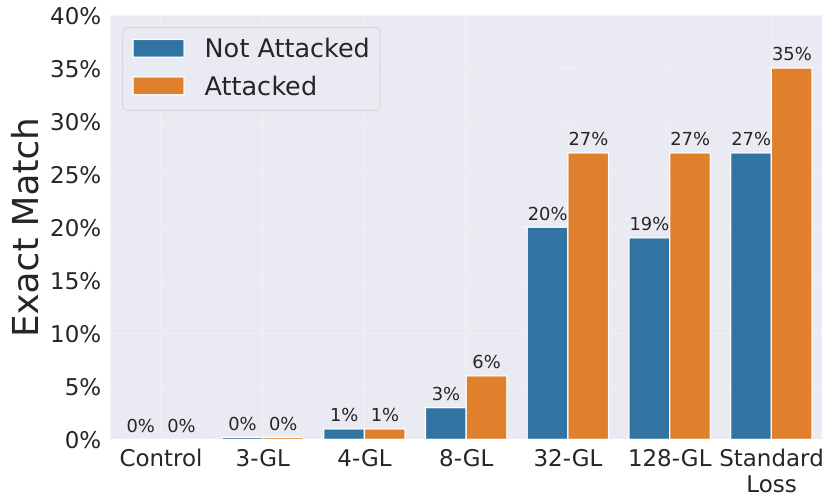

Adversarial Attacks#

Adversarial attacks are a crucial aspect of evaluating the robustness and security of language models. The core concept involves crafting malicious inputs designed to mislead the model into producing unintended or incorrect outputs. The effectiveness of these attacks highlights vulnerabilities in model architectures and training methodologies. These attacks often exploit subtle weaknesses such as overfitting, memorization of training data, or biases present in the training dataset. A successful adversarial attack can expose private information embedded in the model or force it to generate undesirable outputs like harmful content or false statements. Research into adversarial attacks is crucial for developing stronger, more secure LLMs that are better equipped to handle malicious or unexpected inputs. Studying these attacks helps researchers identify vulnerabilities and develop mitigation strategies, such as improved regularization techniques or more robust training procedures. The ongoing arms race between attack development and defense mechanisms drives innovation in the field and ultimately leads to a greater understanding of the limitations of current LLMs and the path towards improved security.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several avenues. Scaling the Goldfish loss to significantly larger language models (hundreds of billions of parameters) is crucial, as larger models exhibit more severe memorization. Investigating the interaction between Goldfish loss and other memorization mitigation techniques (like differential privacy) would reveal potential synergistic effects. A more thorough analysis of the adversarial robustness of Goldfish-trained models is needed, going beyond beam search attacks to encompass a wider range of extraction methods. Finally, examining the impact of varying the hyperparameter ‘k’ across different datasets and model architectures would shed light on optimal configurations for diverse applications. These directions would enhance the method’s practical applicability and solidify its role in responsible LLM development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

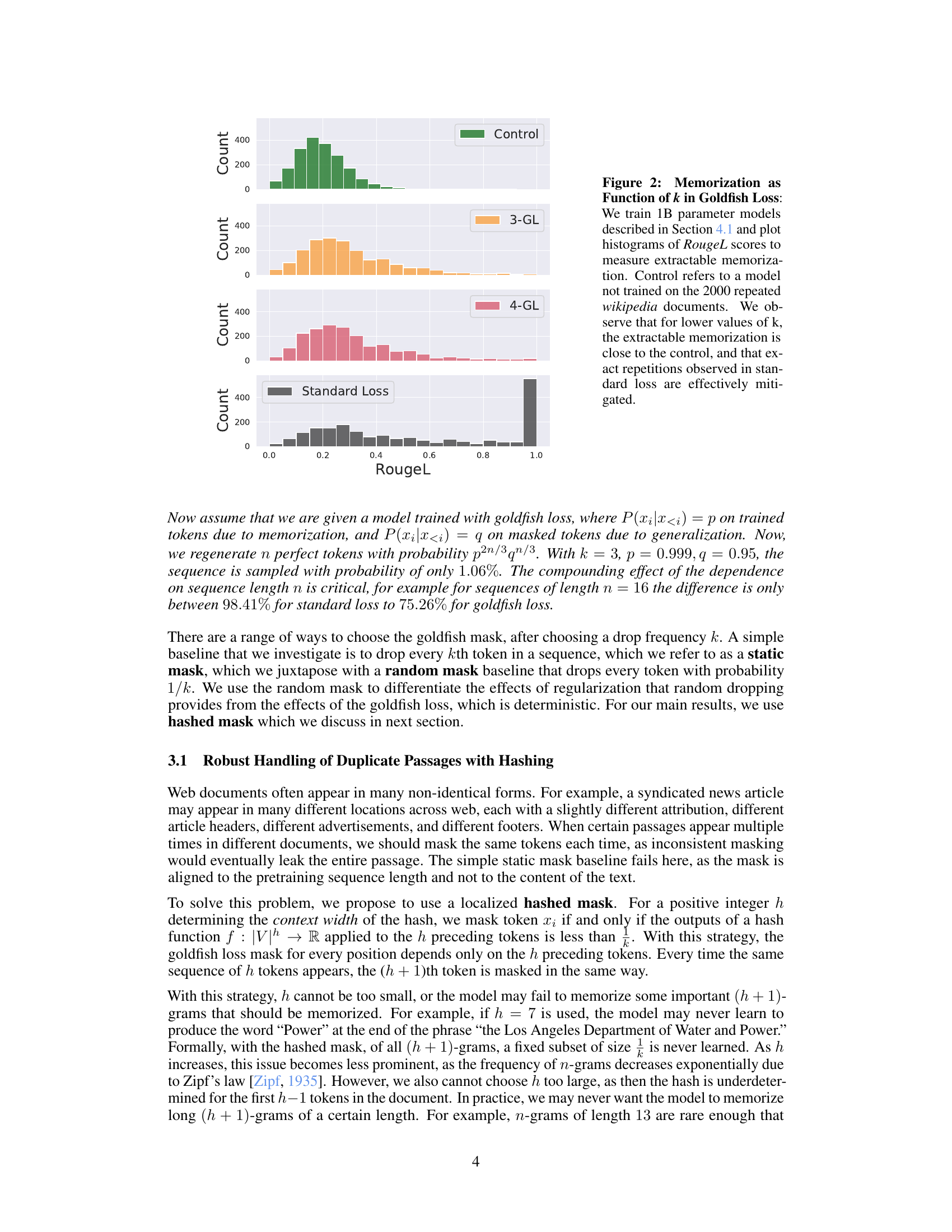

🔼 This figure shows the effectiveness of the Goldfish Loss in mitigating memorization for different values of the hyperparameter k. Four different models were trained: a control model (without any training on the target data), a model trained with standard loss, and two models trained with Goldfish Loss using k=3 and k=4. Histograms of RougeL scores are plotted for each model to show the distribution of extractable memorization. The results show that as k increases, the distribution shifts to the left, indicating less memorization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Memorization as Function of k in Goldfish Loss: We train 1B parameter models described in Section 4.1 and plot histograms of RougeL scores to measure extractable memorization. Control refers to a model not trained on the 2000 repeated wikipedia documents. We observe that for lower values of k, the extractable memorization is close to the control, and that exact repetitions observed in standard loss are effectively mitigated.

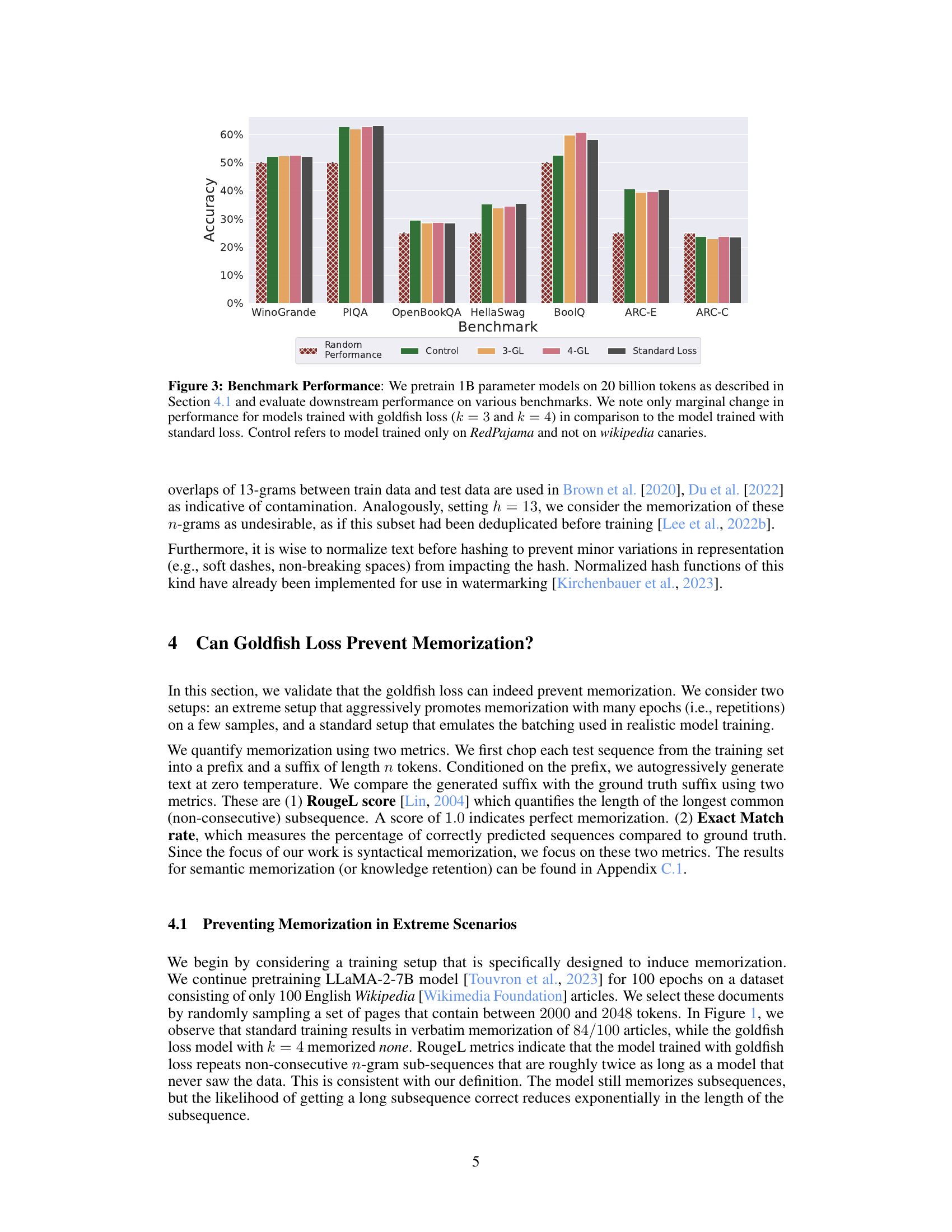

🔼 This figure compares the performance of 1B parameter models trained with standard loss and goldfish loss (k=3 and k=4) across various downstream benchmarks. The models were pretrained on 20 billion tokens. The results show that the goldfish loss results in only a marginal decrease in performance compared to the standard loss, indicating that the proposed technique effectively mitigates memorization without significantly sacrificing model performance on downstream tasks. A control model trained only on RedPajama (without Wikipedia data) is included for comparison, highlighting the impact of the Wikipedia data on model performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: Benchmark Performance: We pretrain 1B parameter models on 20 billion tokens as described in Section 4.1 and evaluate downstream performance on various benchmarks. We note only marginal change in performance for models trained with goldfish loss (k = 3 and k = 4) in comparison to the model trained with standard loss. Control refers to model trained only on RedPajama and not on wikipedia canaries.

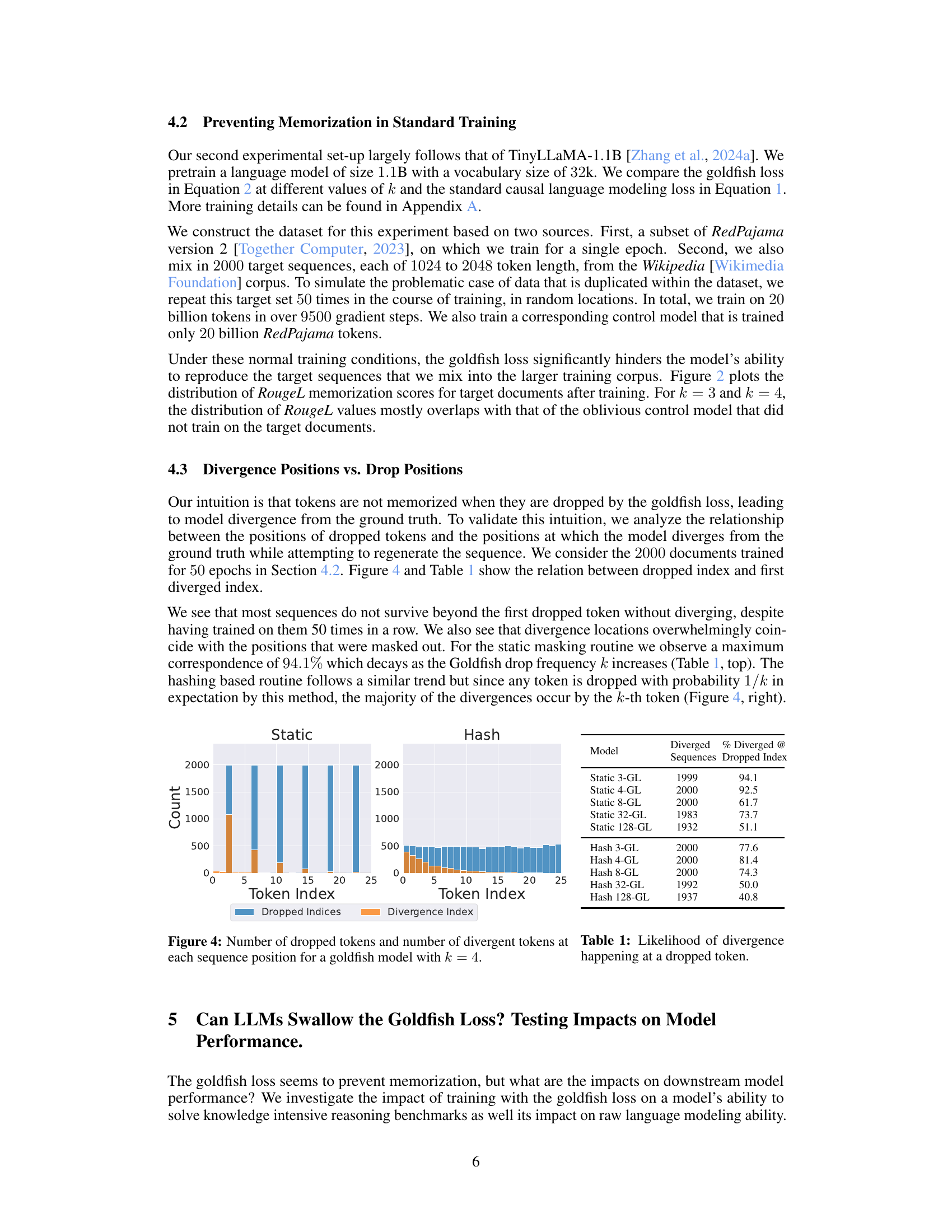

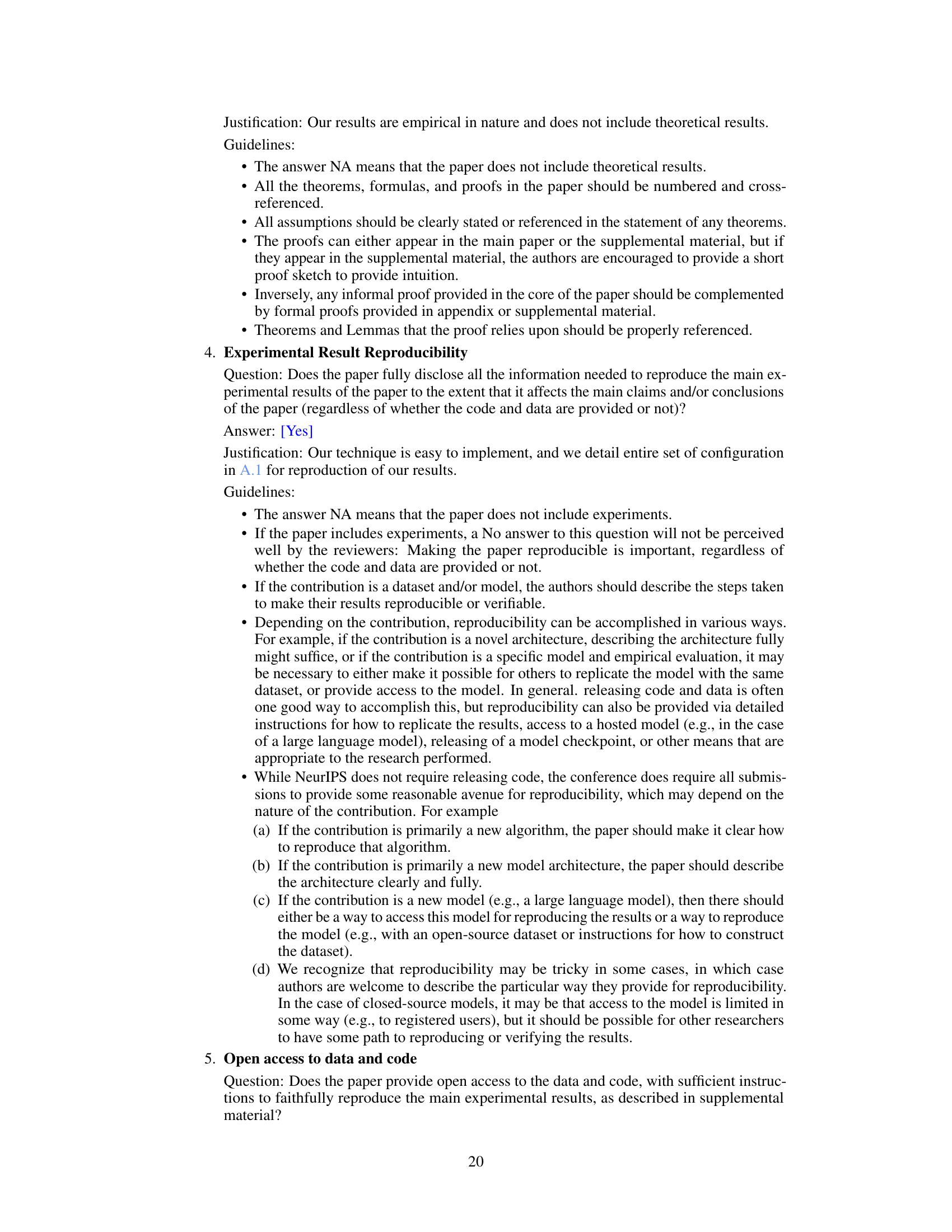

🔼 This figure visualizes the relationship between dropped tokens (due to the goldfish loss) and the positions where the model’s generated sequence diverges from the ground truth. The left panel shows results for a model using a static mask (dropping every kth token), while the right panel shows the results for a model using a hash-based mask. The orange bars represent the index of the first token where the model diverges from the ground truth. The blue bars represent the index of the dropped tokens. This data supports the claim that the goldfish loss effectively prevents memorization by causing the model to diverge at, or near, positions where tokens were excluded during training.

read the caption

Figure 4: Number of dropped tokens and number of divergent tokens at each sequence position for a goldfish model with k = 4.

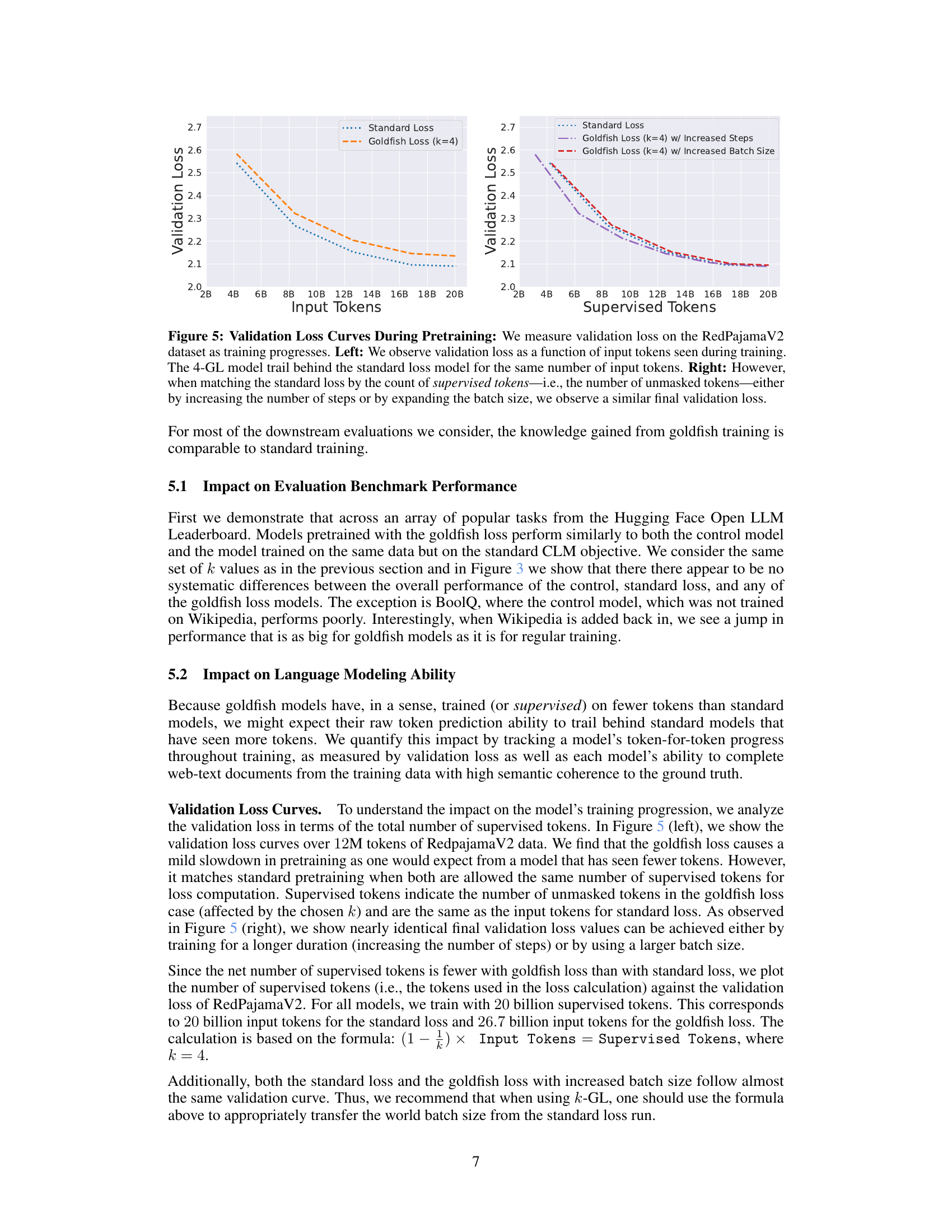

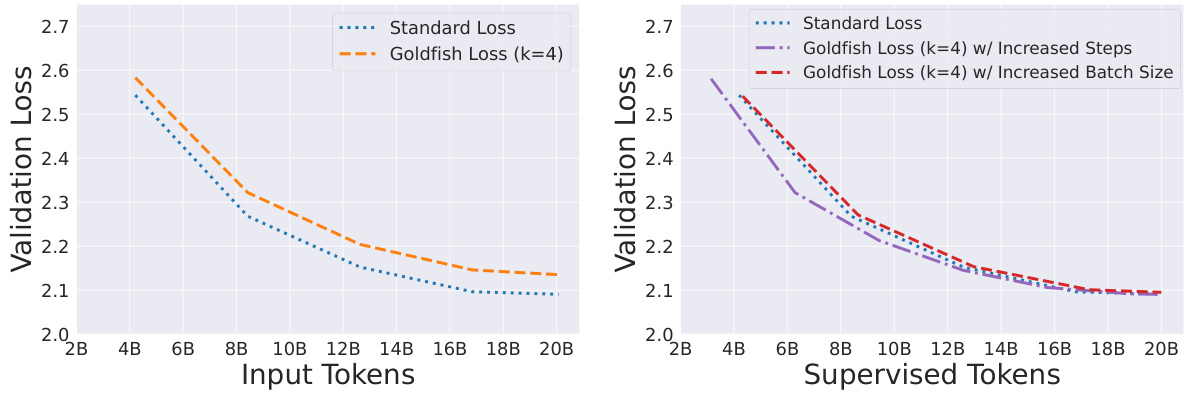

🔼 The figure shows the validation loss curves during the pretraining phase. The left panel compares the validation loss of the standard loss model and the goldfish loss model (k=4) as a function of the number of input tokens. The goldfish loss model shows a slightly higher validation loss for the same number of input tokens. The right panel shows the validation loss curves of the standard loss model and two goldfish loss models (k=4), one trained with increased steps and the other with increased batch size. In this case, both the goldfish models have similar validation loss as the standard loss when comparing the number of supervised tokens (the number of unmasked tokens).

read the caption

Figure 5: Validation Loss Curves During Pretraining: We measure validation loss on the RedPajamaV2 dataset as training progresses. Left: We observe validation loss as a function of input tokens seen during training. The 4-GL model trail behind the standard loss model for the same number of input tokens. Right: However, when matching the standard loss by the count of supervised tokens-i.e., the number of unmasked tokens either by increasing the number of steps or by expanding the batch size, we observe a similar final validation loss.

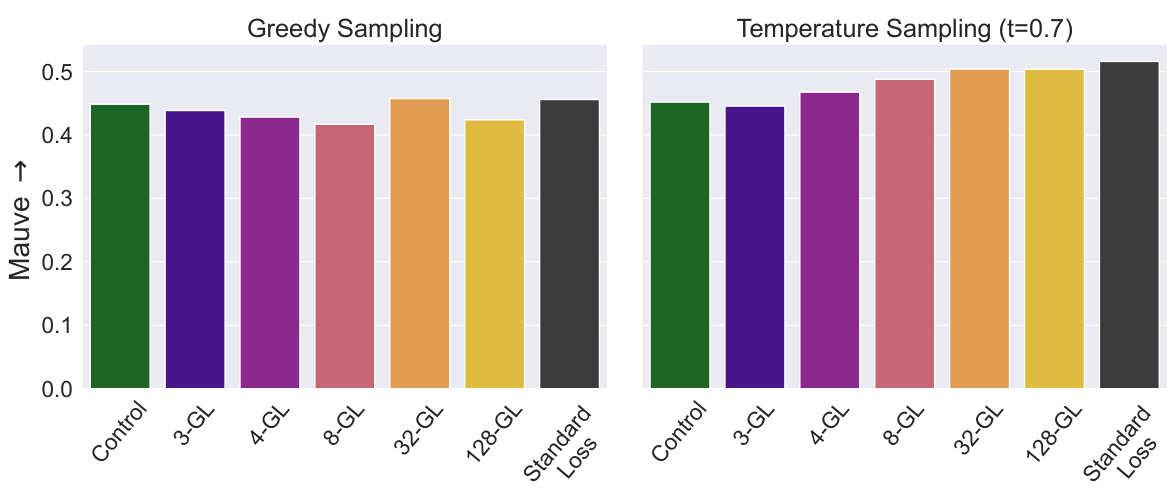

🔼 The bar chart visualizes Mauve scores, a metric evaluating the quality of generated text, for various language models trained using different methods. The models include a control (no goldfish loss), standard causal language modeling (CLM), and several models using the goldfish loss with varying k values (3, 4, 8, 32, 128). Two sampling strategies are compared: greedy sampling and temperature sampling (t=0.7). The chart shows that goldfish loss models generally maintain comparable Mauve scores to the CLM and control models, indicating that the proposed method doesn’t significantly hurt the fluency and naturalness of generated text.

read the caption

Figure 6: Mauve scores: We compute Mauve scores for models trained with goldfish loss under different sampling strategies. We see there is a minimal drop in quality compared to the model trained with CLM objective or the Control model. See text for more details.

🔼 This figure shows the results of membership inference attacks on language models trained with and without the goldfish loss. Membership inference attacks aim to determine whether a given data sample was part of the model’s training data. The figure uses two different metrics: ‘Loss’ and ‘zlib’, both measuring the effectiveness of the attack. The x-axis represents the false positive rate (the rate at which the model incorrectly identifies a non-training sample as a training sample), and the y-axis represents the true positive rate (the rate at which the model correctly identifies a training sample). The different colored lines represent different models trained with various parameters (standard loss and goldfish loss with varying values of k). The results show that while the goldfish loss does offer some level of protection against membership inference attacks, the protection is not complete, especially with higher values of k.

read the caption

Figure 7: Membership Inference Attack: We perform membership inference attack using target (trained on) and validation wikipedia documents. We observe only marginal difference in attack success for goldfish loss in comparison with standard loss.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of 1B parameter models trained with different goldfish loss parameters (k=3, 4, 8, 32, 128) and standard loss on various downstream benchmarks. The results show that the goldfish loss leads to only marginal performance differences compared to the standard loss, especially with smaller k values. A control model (trained only on RedPajama, without Wikipedia data) is also included for comparison.

read the caption

Figure 8: Benchmark Performance: We pretrain 1B parameter models on 20 billion tokens as described in Section 4.1 and evaluate downstream performance on various benchmarks. We note only marginal change in performance for models trained with goldfish loss (k = 3 and k = 4) in comparison to the model trained with standard loss. Control refers to model trained only on RedPajama and not on wikipedia canaries.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different goldfish loss strategies and their impact on both memorization and downstream benchmark accuracy. The left panel shows the memorization scores (RougeL) for various strategies, indicating how well the model resists memorizing the training data. The right panel displays the mean benchmark accuracy across multiple tasks, showing how the different strategies affect model performance on downstream applications. The control model serves as a baseline, representing a model trained without the Wikipedia samples used to evaluate memorization.

read the caption

Figure 9: A comparison of goldfish loss across its strategies. We compare both memorization scores (left) and downstream benchmark accuracy (right). Control refers to model trained without wikipedia samples (target data for extractable memorization evaluation.)

🔼 This figure compares memorization scores (BERTScore, Rouge1, Rouge2, RougeL, and Exact Match) between models trained with standard loss, goldfish loss, and no training (control). Despite the goldfish loss significantly reducing verbatim memorization (Exact Match), semantic information is still partially retained, as indicated by the higher BERTScore and Rouge scores compared to the control group.

read the caption

Figure 10: Semantic Memorization: In addition to RougeL and Rouge2 measuring unigram overlap and bigram overlap, we also measure BERTScore [Zhang* et al., 2020] which is BERT embedding-based scores where a higher score suggests a closer semantic similarity to the ground truth. Despite the 4-goldfish model's deterrence to regenerate the exact sequences seen during training, the increased BERT embedding-based BERTScore and n-gram-based Rouge scores (in comparison to Control) suggest that paraphrases might still be leaked. This observation implies that while the model does not memorize, it still learns and retains knowledge from the underlying data.

Full paper#