↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Graph anomaly detection often uses graph autoencoders (GAEs) to identify graphs with high reconstruction errors as anomalies. However, this approach has limitations; the paper identifies a counterintuitive phenomenon called ‘reconstruction flip’ where anomalous graphs are reconstructed more accurately than normal ones. This highlights a critical flaw in the assumption underlying many existing GAE-based methods.

The paper proposes MUSE, a simple yet effective method. MUSE addresses the reconstruction flip issue by using multifaceted summaries (mean, standard deviation, etc.) of reconstruction errors rather than only the mean. This surprisingly simple change significantly boosts the performance of anomaly detection, outperforming existing methods across various datasets. This innovative approach provides valuable insights into using reconstruction errors effectively in graph anomaly detection.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common assumptions in graph anomaly detection, opening avenues for improved methods and better understanding of graph reconstruction. Its simple yet effective solution (MUSE) and extensive empirical analysis offer valuable insights for researchers in the field.

Visual Insights#

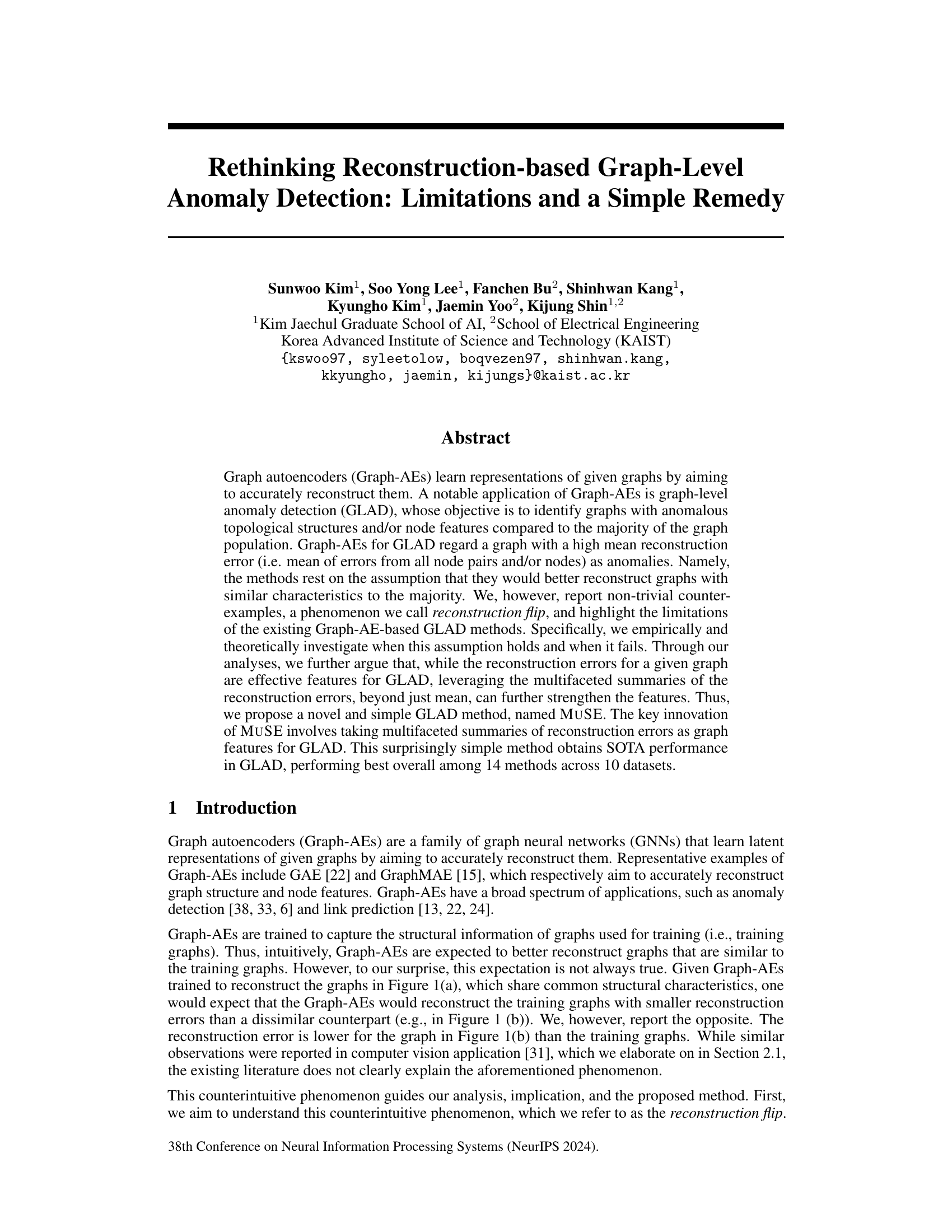

The figure shows a counter-intuitive result from graph autoencoders. Three training graphs (a) with similar structures have higher reconstruction errors than an unseen graph (b) with a different structure. This phenomenon, termed ‘reconstruction flip,’ challenges the assumption that graph autoencoders reconstruct similar graphs better than dissimilar ones, a core assumption in graph-level anomaly detection methods.

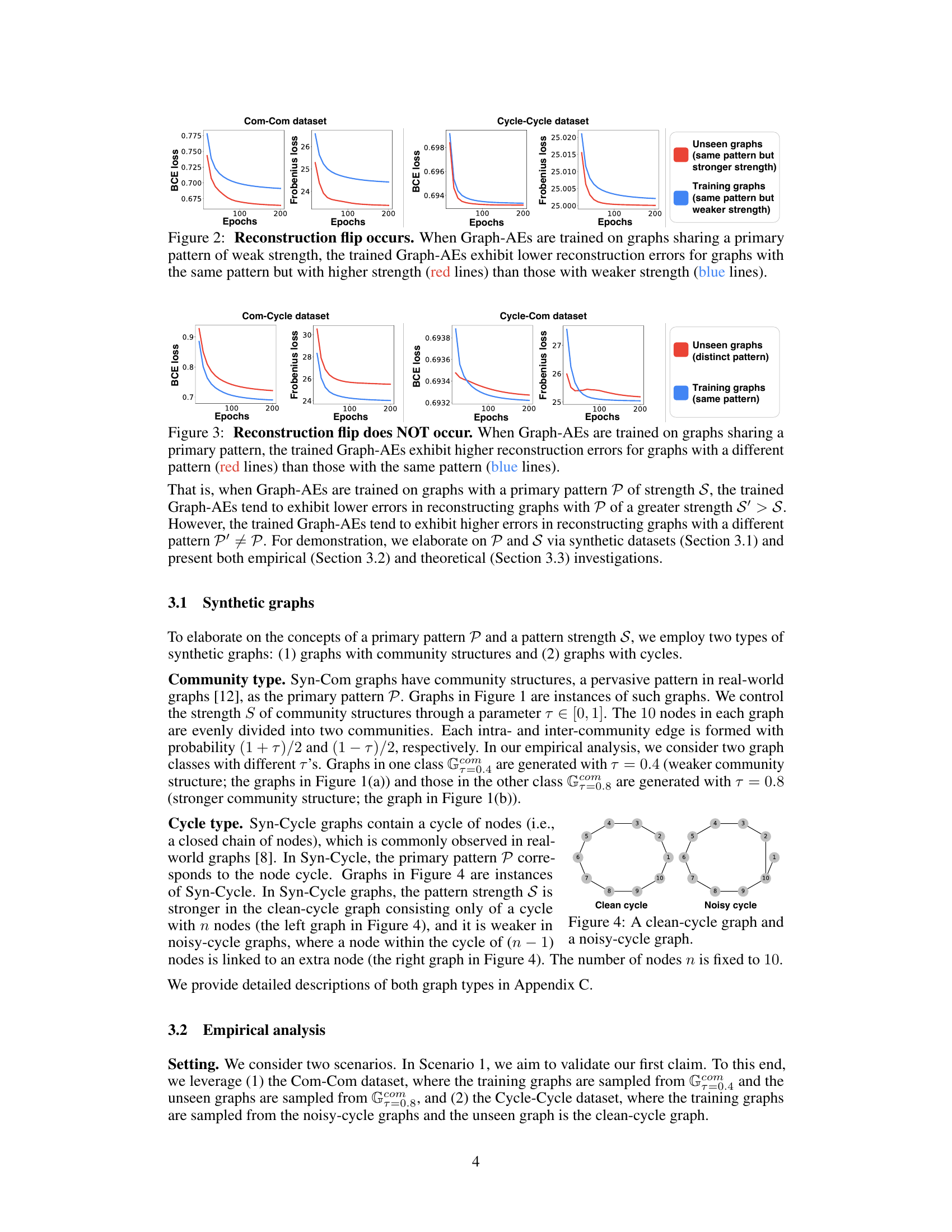

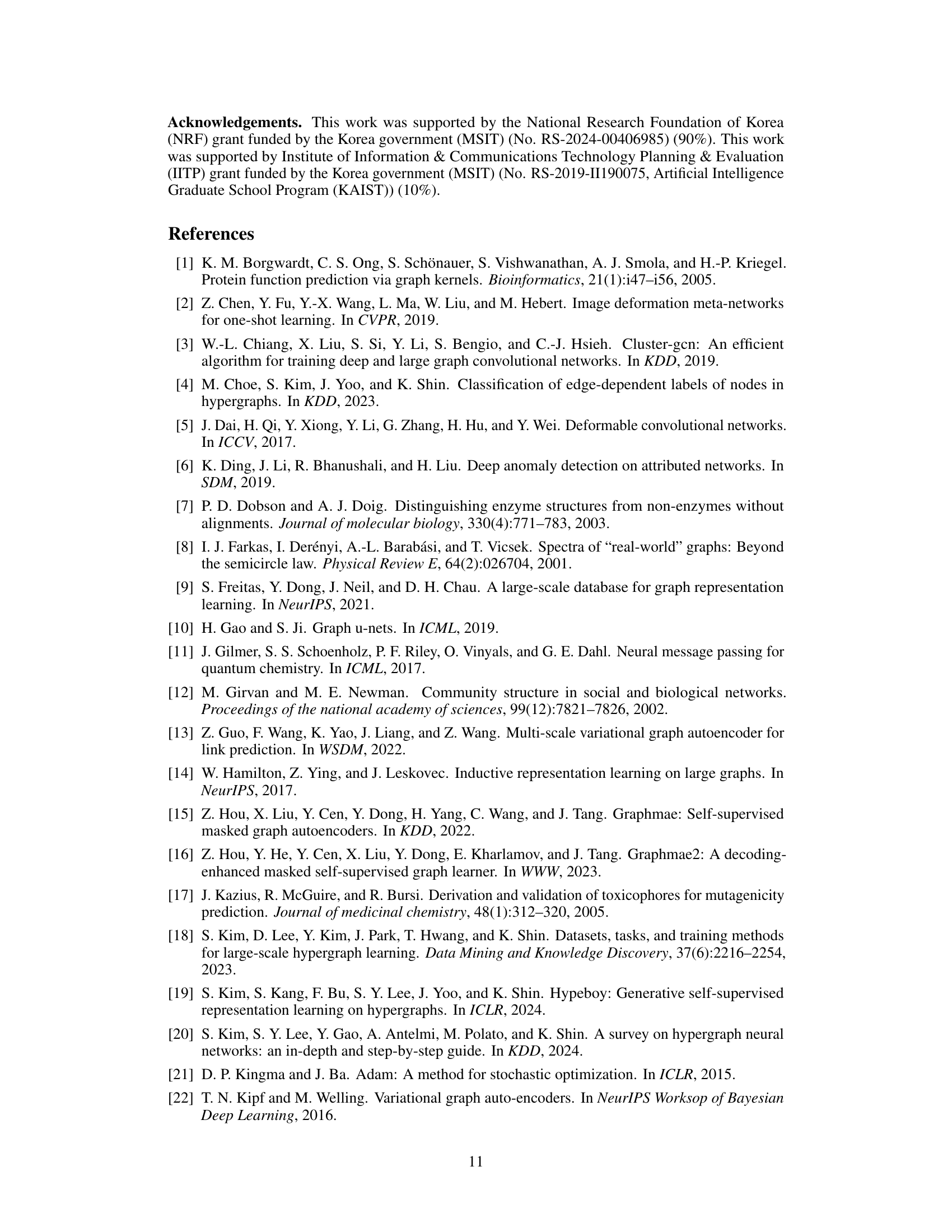

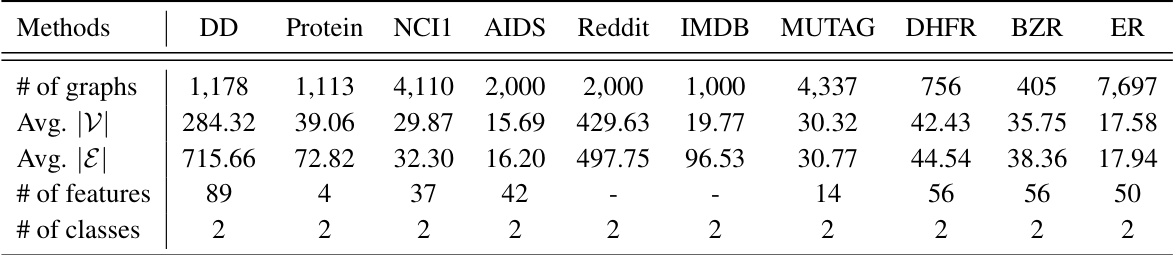

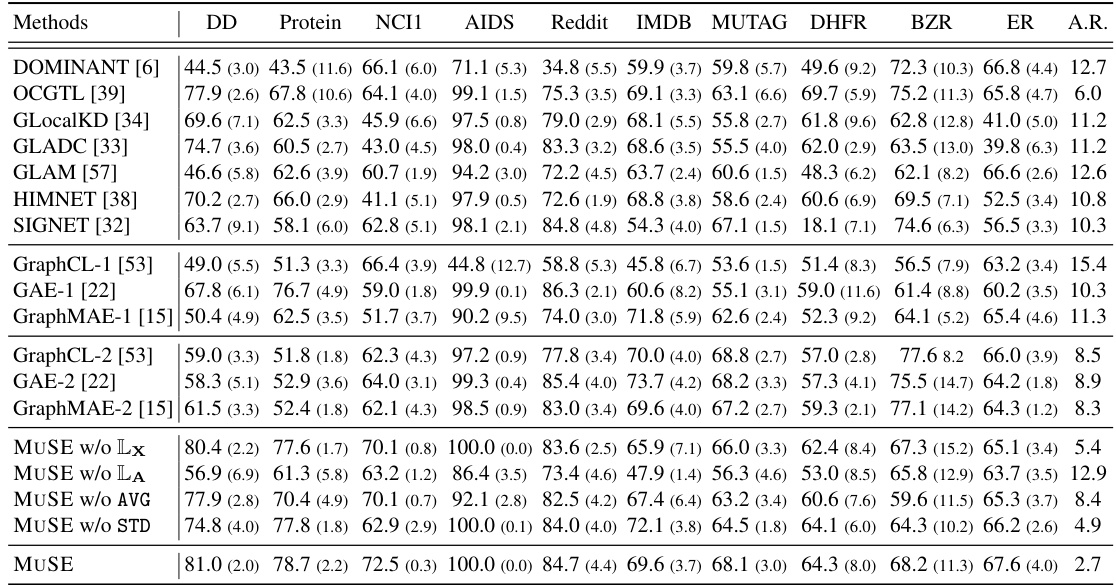

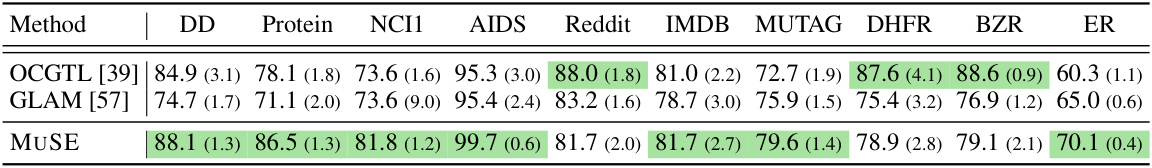

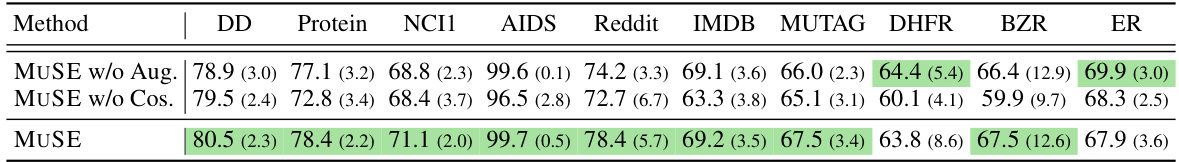

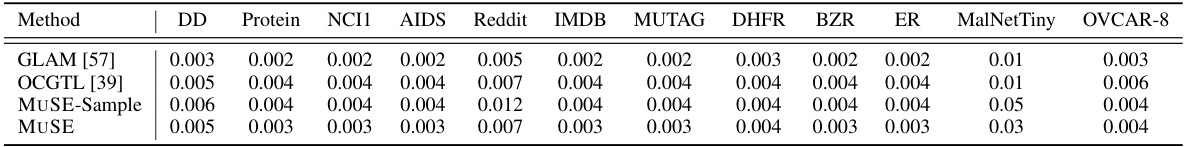

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments on ten datasets, comparing MUSE with 17 other methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) for each method on each dataset. The best and second-best performing methods for each dataset are highlighted, along with the average ranking of each method across all datasets. The results demonstrate the superior performance of MUSE compared to existing GLAD methods.

In-depth insights#

Reconstruction Flip#

The concept of “Reconstruction Flip” highlights a counterintuitive phenomenon in graph autoencoders (GAEs) used for anomaly detection. Contrary to the expectation that GAEs should reconstruct similar graphs better, it was observed that GAEs sometimes reconstruct graphs with distinct, but stronger structural patterns more accurately than training graphs. This phenomenon is crucial because GAE-based anomaly detection methods often rely on the assumption that reconstruction errors accurately reflect the graph’s similarity to the training set. Reconstruction Flip undermines this assumption, suggesting that high reconstruction error doesn’t necessarily indicate an anomaly. The authors delve into theoretical analysis to explain these flips, emphasizing the role of primary structural patterns and their strengths in the reconstruction process. This detailed analysis reveals how variations in pattern strength can lead to unexpected reconstruction results, impacting anomaly detection accuracy significantly. The unexpected behavior of GAEs challenges the fundamental assumptions of current graph anomaly detection techniques. Understanding Reconstruction Flip is essential for developing more robust and reliable anomaly detection methods.

MUSE Method#

The MUSE (Multifaceted Summarization of Reconstruction Errors) method offers a novel approach to graph-level anomaly detection. Instead of relying solely on the mean reconstruction error, a common limitation of Graph-AE based methods, MUSE leverages multifaceted summaries of these errors. This includes statistics like mean, standard deviation, and potentially others, creating a richer feature representation of the graph. This simple yet effective change addresses the “reconstruction flip” phenomenon, where anomalous graphs might exhibit unexpectedly low mean reconstruction errors. By capturing the multifaceted nature of reconstruction errors, MUSE provides a more robust and informative representation for anomaly detection, leading to improved performance. The method’s simplicity and strong empirical results highlight the value of exploring alternative error summarization techniques for anomaly detection in graph data.

GLAD Limitations#

The section on GLAD limitations reveals crucial shortcomings in existing graph-level anomaly detection methods. A key limitation is the unreliability of reconstruction error as a sole indicator of anomaly. The paper highlights a phenomenon called “reconstruction flip,” where anomalous graphs, particularly those with exaggerated versions of patterns present in the training data, may exhibit lower reconstruction errors than normal graphs. This challenges the fundamental assumption underlying many Graph-AE based GLAD methods. The authors argue that while reconstruction errors are valuable features, a simplistic reliance on the mean error is insufficient. A multifaceted analysis of the error distribution (e.g., mean, standard deviation) is proposed as a solution, to more effectively capture the nuances of the reconstruction process and improve GLAD performance. This analysis underlines the importance of moving beyond simplistic measures and utilizing more sophisticated feature engineering techniques for robust anomaly detection in graph data.

Error Features#

The concept of ‘Error Features’ in anomaly detection using graph reconstruction methods is insightful. It proposes leveraging the discrepancies between a reconstructed graph and the original graph as features to identify anomalies. Instead of simply relying on the average reconstruction error, a multifaceted approach is advocated, considering various statistical summaries (e.g., mean, standard deviation) of the errors across different components (nodes, edges). This is crucial because the average error alone can be misleading, as demonstrated by the ‘reconstruction flip’ phenomenon, where anomalous graphs may exhibit lower average errors than normal ones. MUSE (Multifaceted Summarization of Reconstruction Errors), a novel method, utilizes these multifaceted summaries, significantly improving anomaly detection performance. The success hinges on the inherent informative nature of reconstruction errors which, when analyzed comprehensively, effectively highlight subtle differences between normal and anomalous graph structures.

Future Work#

The paper’s discussion of future work could benefit from a more structured approach. While mentioning scalability improvements as a crucial area, it lacks specific strategies or concrete plans to achieve this. Addressing the limitations of relying on a small set of primary graph patterns is essential. The current analysis needs a broader and more rigorous exploration of graph patterns in diverse real-world datasets. Investigating the effect of noise and variability in real-world data on the reconstruction flip phenomenon is also key. Moreover, the paper should suggest potential applications of MUSE beyond anomaly detection, potentially exploring its use in other areas of graph analysis or other domains where reconstruction error analysis is valuable. Finally, a more detailed exploration of the theoretical underpinnings of the reconstruction flip could enhance its value. This would involve not only proving existing theoretical assertions but also conducting a more thorough investigation into the implications of these results.

More visual insights#

More on figures

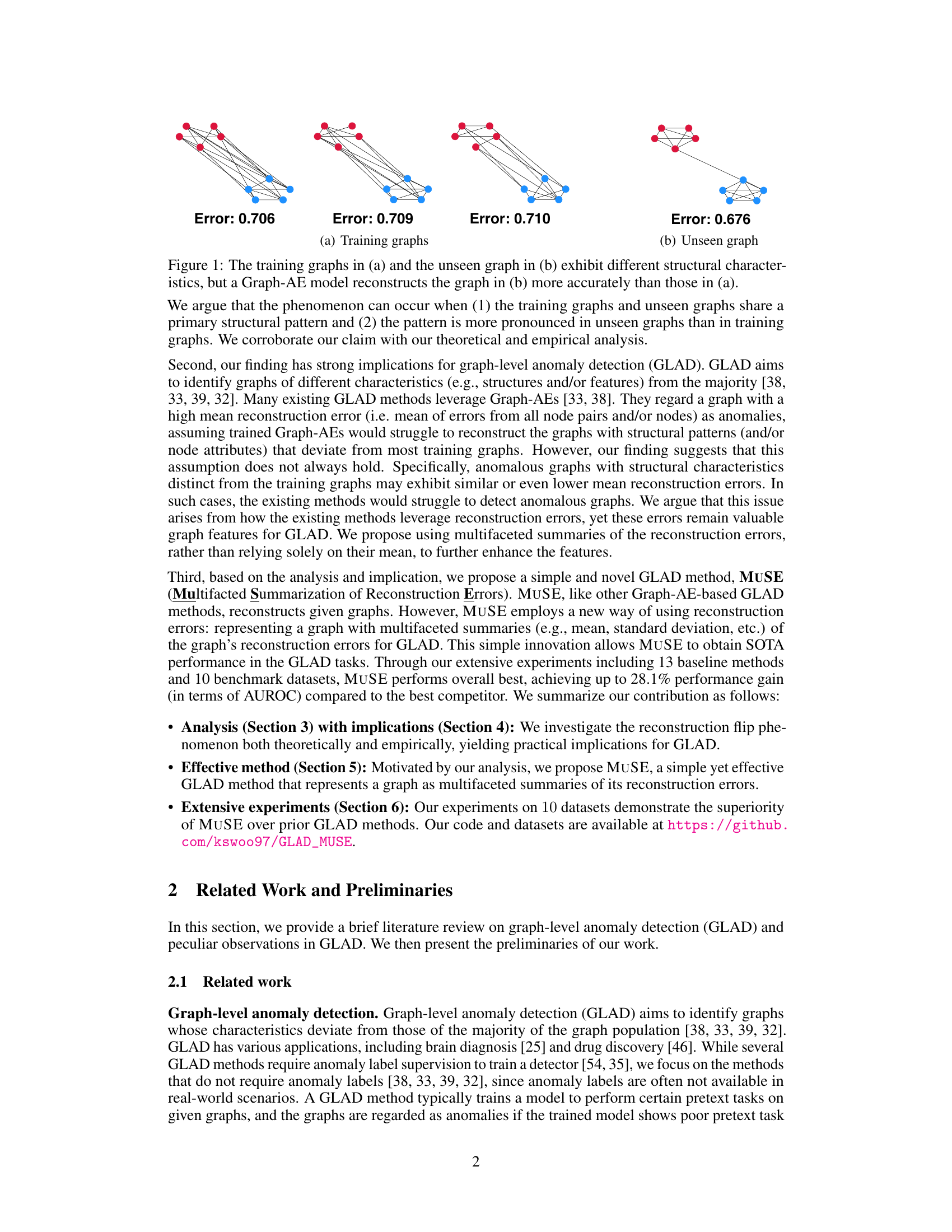

This figure shows the results of training graph autoencoders (GAEs) on graphs with similar structures (same primary pattern) but varying strength. The experiment demonstrates the ‘reconstruction flip’ phenomenon. GAEs trained on weak-strength graphs reconstruct strong-strength graphs more accurately (lower reconstruction error) than weak-strength graphs. This contradicts the common assumption in Graph-AE-based anomaly detection that similar graphs should have lower reconstruction errors.

This figure shows that when the Graph-AE is trained on graphs with the same primary pattern, it does not exhibit lower reconstruction error for graphs with different patterns. The reconstruction error for graphs with different patterns is higher than that for graphs with the same pattern. This is opposite to the reconstruction flip phenomenon.

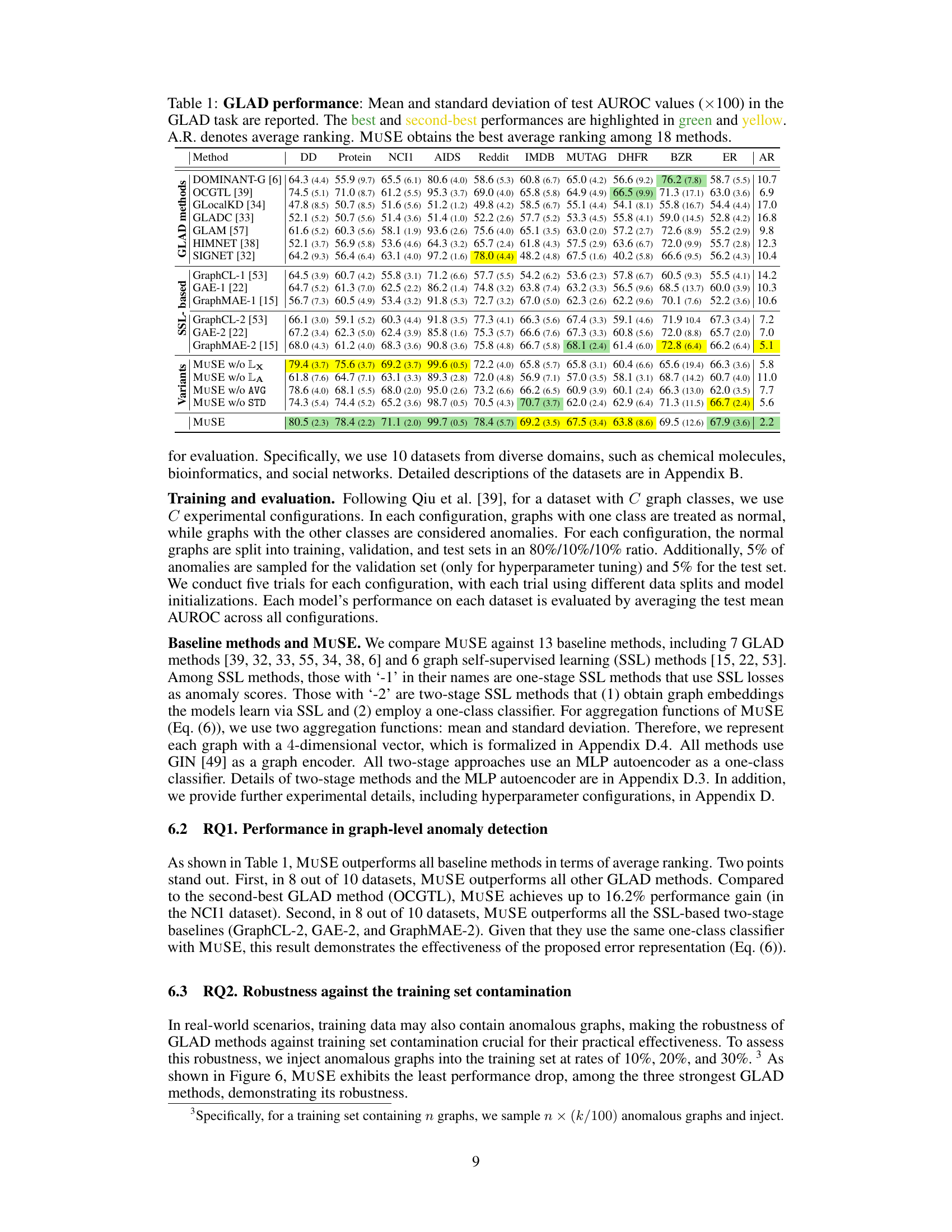

This figure shows two types of synthetic graphs used in the paper to illustrate the concepts of primary pattern P and pattern strength S. The ‘Clean cycle’ graph is a simple cycle with 10 nodes, representing a strong pattern. The ‘Noisy cycle’ graph is almost a cycle, but has one extra edge, making the cycle pattern weaker. These graphs are used to demonstrate reconstruction flip and its implications for graph anomaly detection.

This figure demonstrates a limitation of using only the mean reconstruction error for anomaly detection. Two graphs (G1 and G2) are shown, visually distinct. Despite having very similar mean reconstruction errors (0.6622 and 0.6627, respectively), their error distributions, as shown by the Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) plots, are quite different. This highlights that relying solely on the mean can mask important differences in the underlying data and lead to inaccurate anomaly detection.

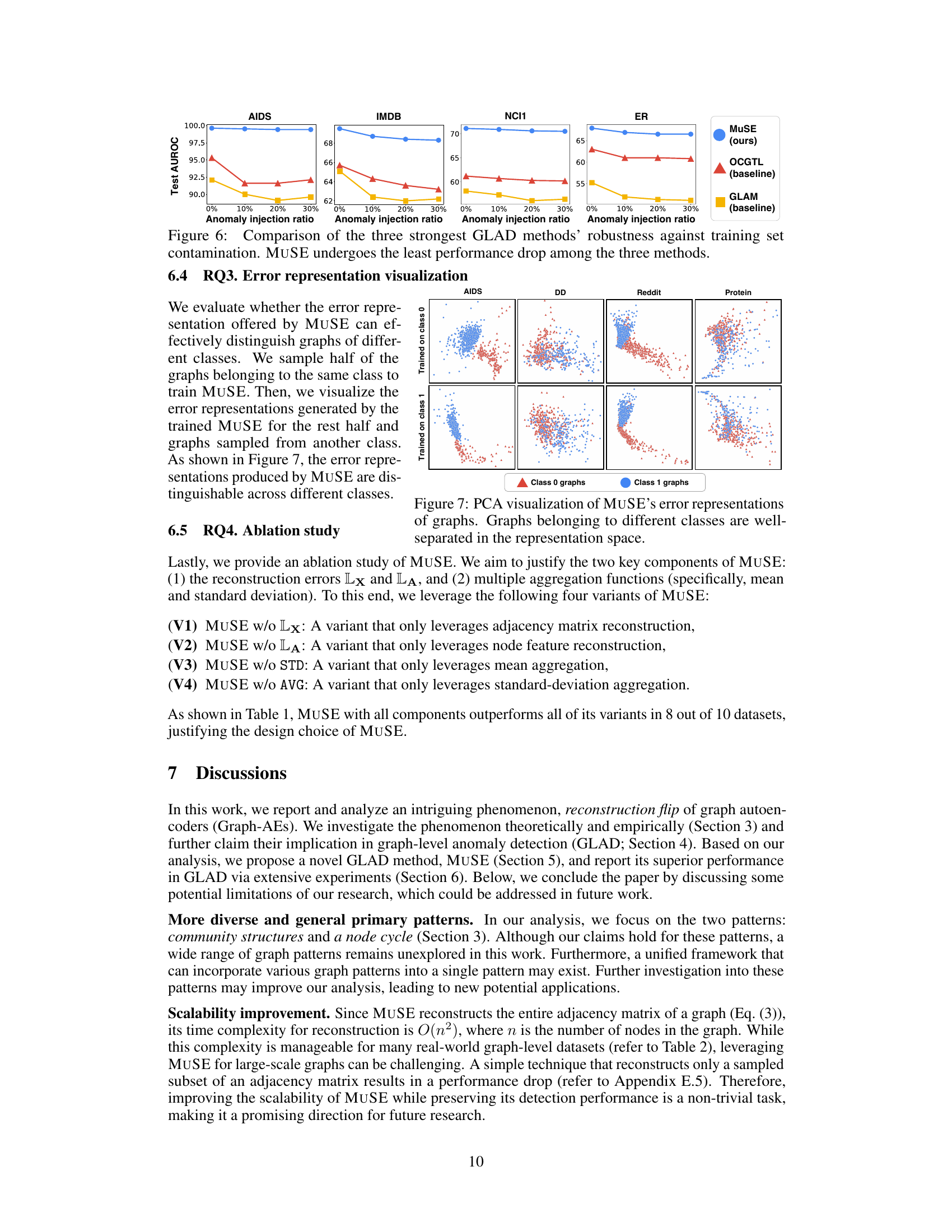

This figure displays the robustness of three GLAD methods (MUSE, OCGTL, and GLAM) against training set contamination. The x-axis represents the percentage of anomalies injected into the training data (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%). The y-axis shows the test AUROC score, a measure of the model’s performance. The figure shows that as the percentage of anomalies in the training data increases, the performance of all three methods decreases. However, MUSE shows the smallest decrease, indicating its superior robustness to noisy training data containing anomalies.

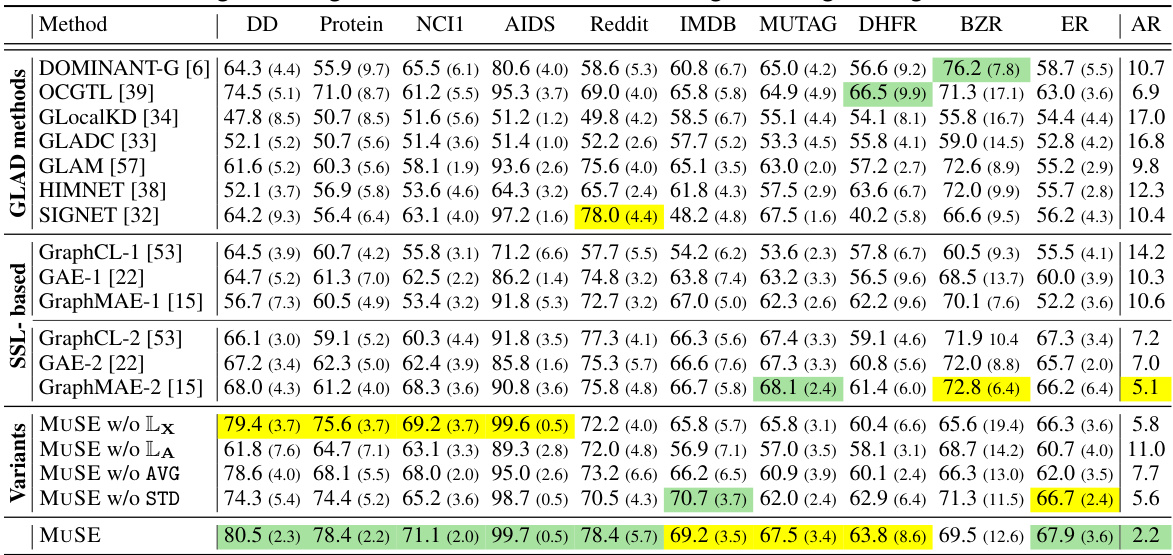

This figure shows the results of applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the error representations generated by MUSE. The plot visualizes how well MUSE can separate graphs from different classes in a lower-dimensional space. The clear separation suggests that MUSE’s error representations effectively capture the distinguishing characteristics of graphs from different classes, aiding in accurate anomaly detection.

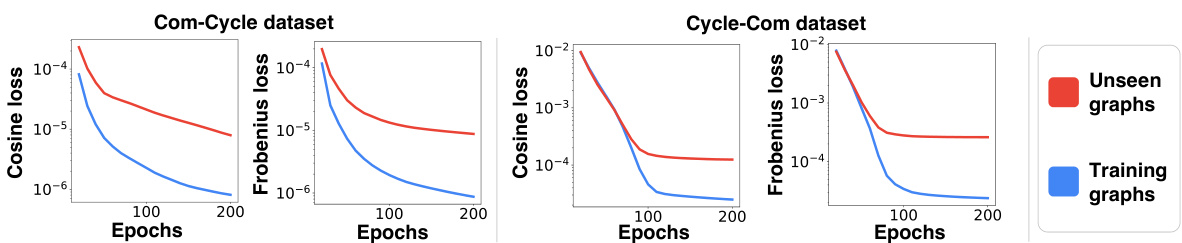

The figure shows the reconstruction error (both BCE and Frobenius loss) of Graph-AEs trained on graphs with weak community structures (blue lines) and then tested on graphs with weak (blue) and strong (red) community structures. It demonstrates that the reconstruction error is lower for the unseen graphs with stronger community structure even though they share the same primary structural pattern with the training graphs. This phenomenon is defined in the paper as reconstruction flip.

The figure shows that when a graph autoencoder is trained on graphs with a certain pattern (e.g., community structure) of weak strength, the model makes smaller reconstruction errors for graphs with the same pattern but stronger strength than for graphs with the same pattern but weaker strength. This phenomenon is called ‘reconstruction flip’.

More on tables

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments using 18 different methods, including the proposed MUSE method. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) values for each method across 10 benchmark datasets. The best-performing method for each dataset is highlighted in green, with the second-best highlighted in yellow. Finally, the average ranking (A.R.) across all datasets is provided for each method.

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments comparing MUSE against 17 other methods across 10 benchmark datasets. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) for each method on each dataset, highlighting the best and second-best performing methods. The average ranking (A.R.) of each method across all datasets is also included. This provides a comprehensive comparison of MUSE’s performance relative to existing GLAD techniques.

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments. It compares the performance of MUSE against 17 other methods across 10 benchmark datasets. The metrics used is the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC), presented as mean and standard deviation. The best and second-best performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The average ranking of each method across all datasets is also provided.

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments. It compares the performance of MUSE against 17 other methods (including 7 GLAD methods and 6 SSL methods) across 10 datasets. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) for each method on each dataset, highlighting the best and second-best performing methods. The average ranking (A.R.) of each method is also provided, indicating MUSE’s superior overall performance.

This table presents the results of the graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) task using the Precision@10 metric. The table compares the performance of MUSE against other GLAD methods across ten different datasets. Precision@10 measures the proportion of correctly identified anomalies among the top 10 ranked graphs. Higher scores indicate better performance in identifying anomalies. The best-performing method for each dataset is highlighted in green, showcasing the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments comparing MUSE against 17 other methods across 10 datasets. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) for each method on each dataset, highlighting the best and second-best performing methods. The average ranking (A.R.) of each method across all datasets is also provided.

This table presents the results of graph-level anomaly detection (GLAD) experiments using various methods, including the proposed MUSE method and several baseline methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for each method on ten different datasets. The best and second-best performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The average ranking of each method across all datasets is also provided.

This table presents the performance comparison of 18 different graph-level anomaly detection methods across 10 datasets. The results are measured using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) metric. The best and second-best performing methods for each dataset are highlighted, and the average ranking of all methods is provided. The table shows that MUSE outperforms other methods in terms of average ranking.

Full paper#