↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The formal verification of programs and proofs has traditionally been a manual process, reliant on the expertise of mathematicians and computer scientists. Recent advancements in machine learning have demonstrated the potential of automating various aspects of this process. However, the application of machine learning techniques to dependently-typed programming languages, such as Agda, remains largely unexplored due to the lack of suitable datasets and the complexity of these languages.

This paper addresses this issue by introducing AGDA2TRAIN, a novel tool that extracts intermediate compilation steps from Agda programs to create a large-scale dataset of Agda program-proofs. Leveraging this dataset, the authors propose QUILL, a neural architecture designed to faithfully represent dependently-typed programs based on their underlying structural properties rather than their nominal representations. QUILL is evaluated in a premise selection task, demonstrating its potential for automating the process of theorem proving.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between dependently-typed programming and machine learning. It introduces a novel dataset and neural architecture for dependently-typed programs, opening exciting new avenues for research in program verification, automated theorem proving, and program synthesis. The work is particularly relevant due to the growing interest in the intersection of formal methods and AI.

Visual Insights#

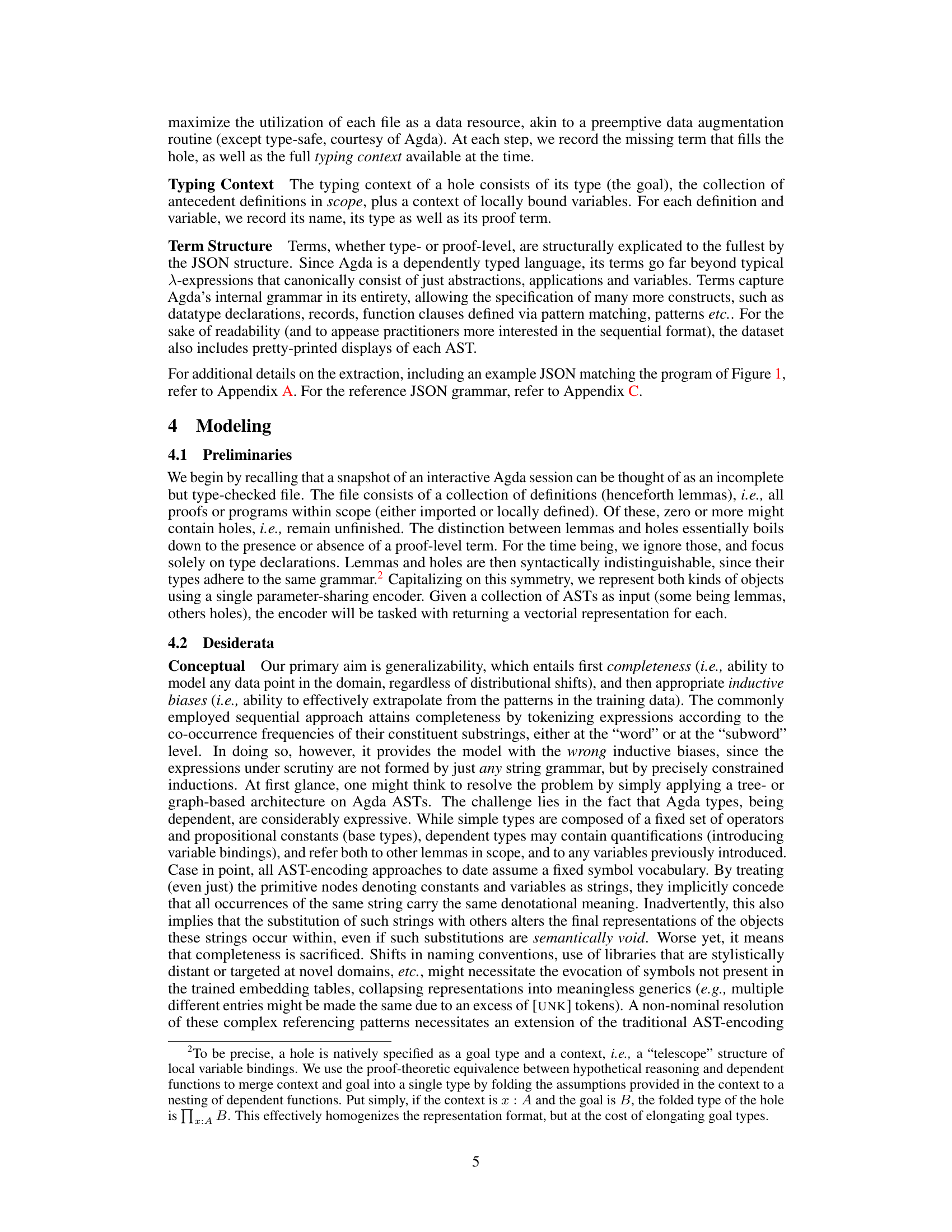

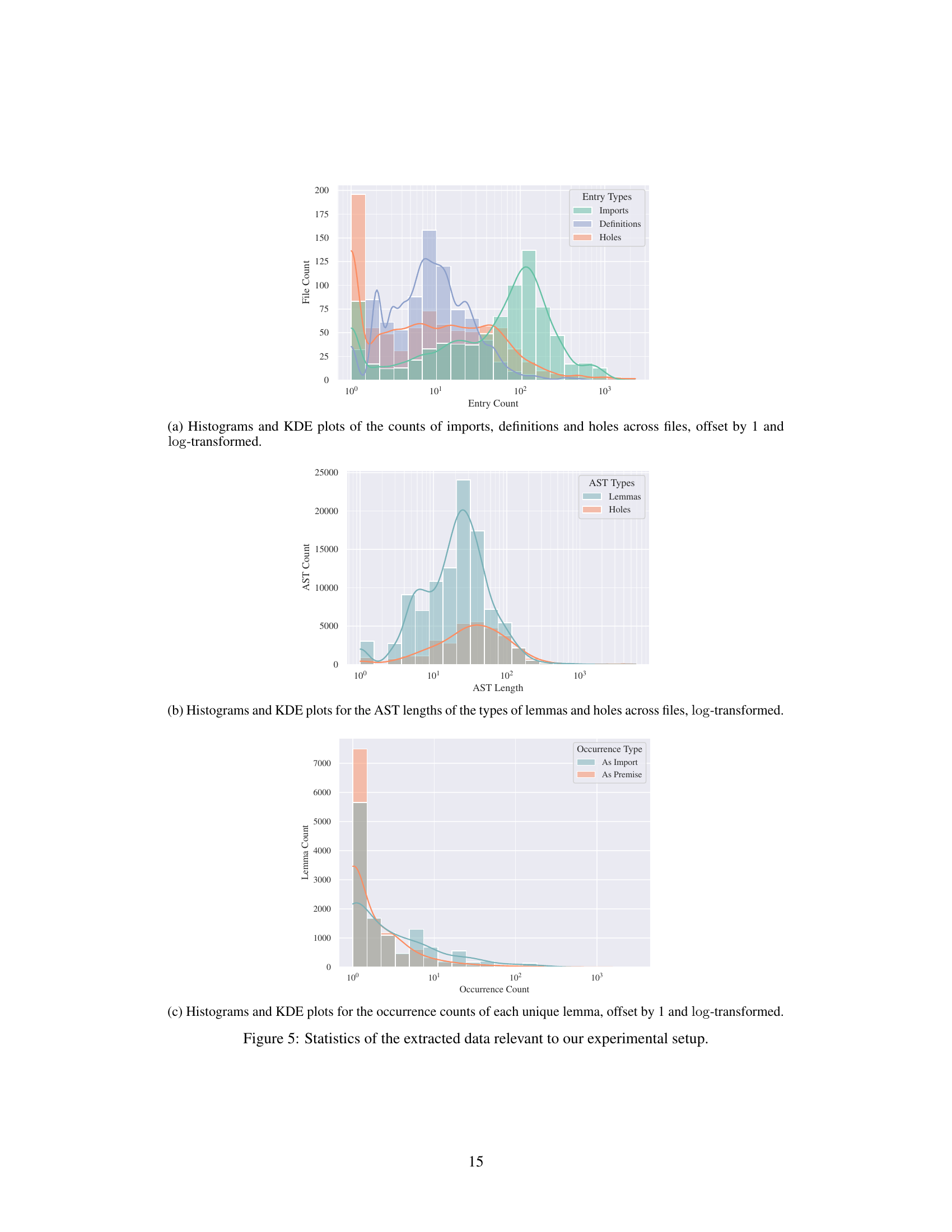

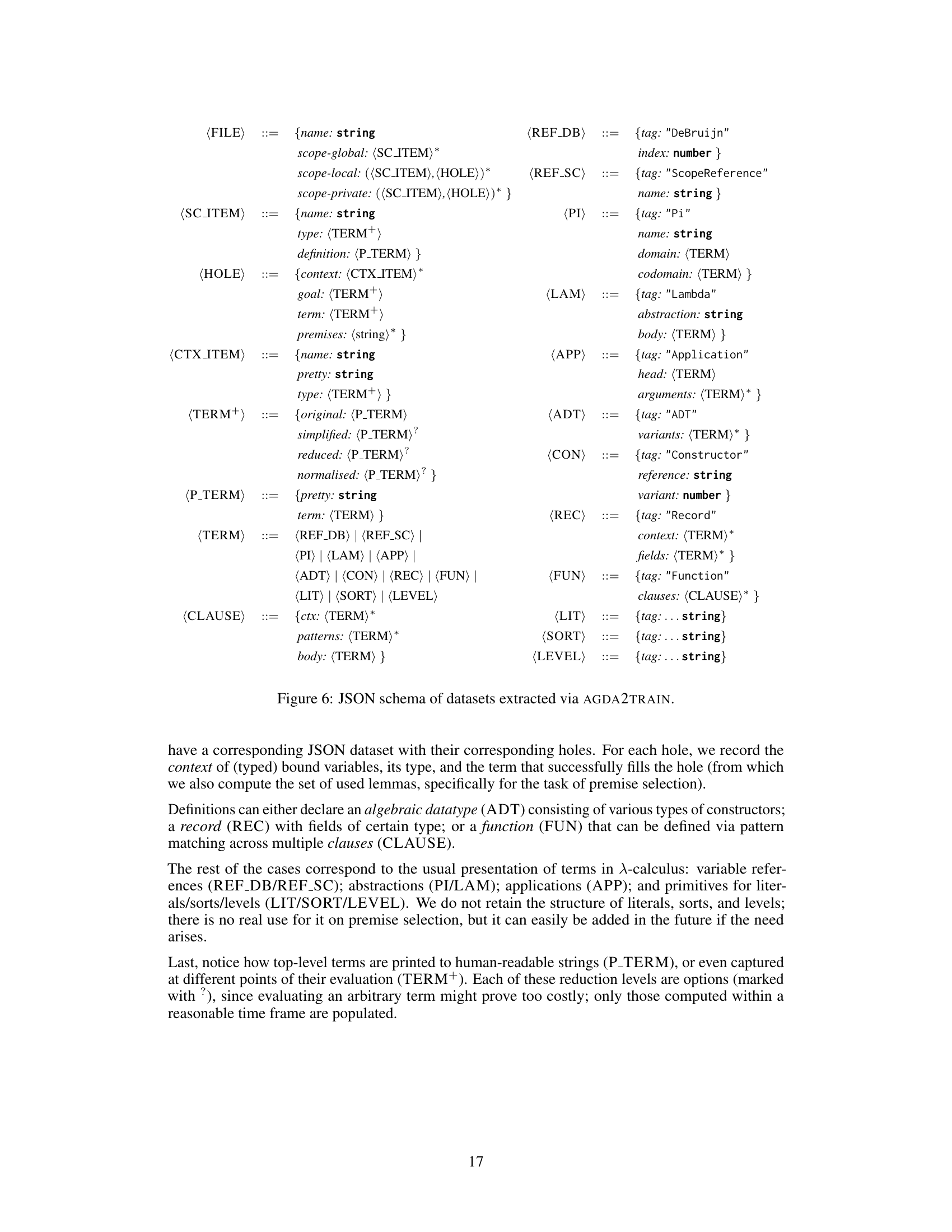

This figure shows a tokenized view of the types of lemmas from Figure 1. It illustrates how the types are represented as trees, with each node representing a specific term or operator. The tokens are shown in different colors or styles to indicate the various kinds of symbols. This visualization is key to understanding how the system represents types for processing by a neural network and is described in detail in Appendix B.1.

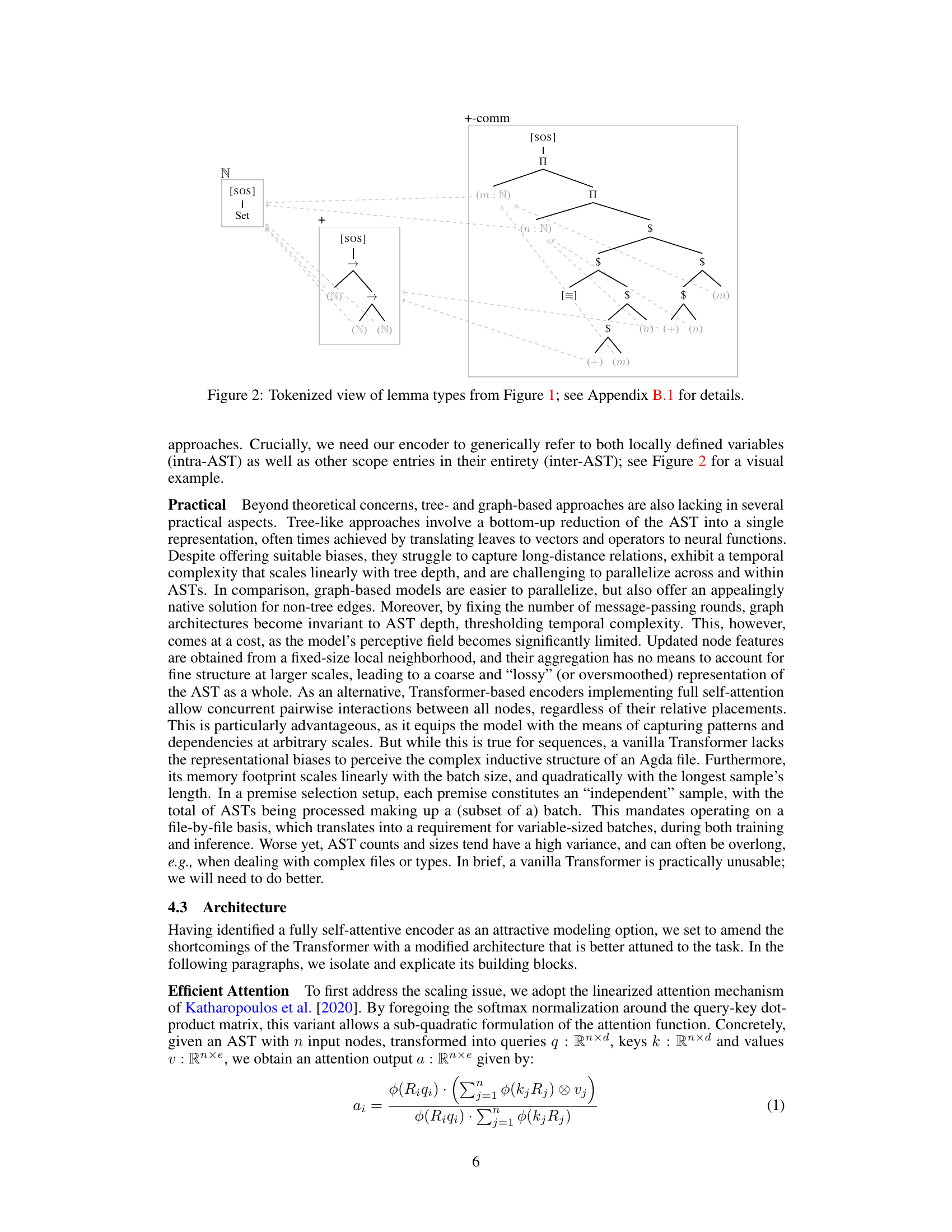

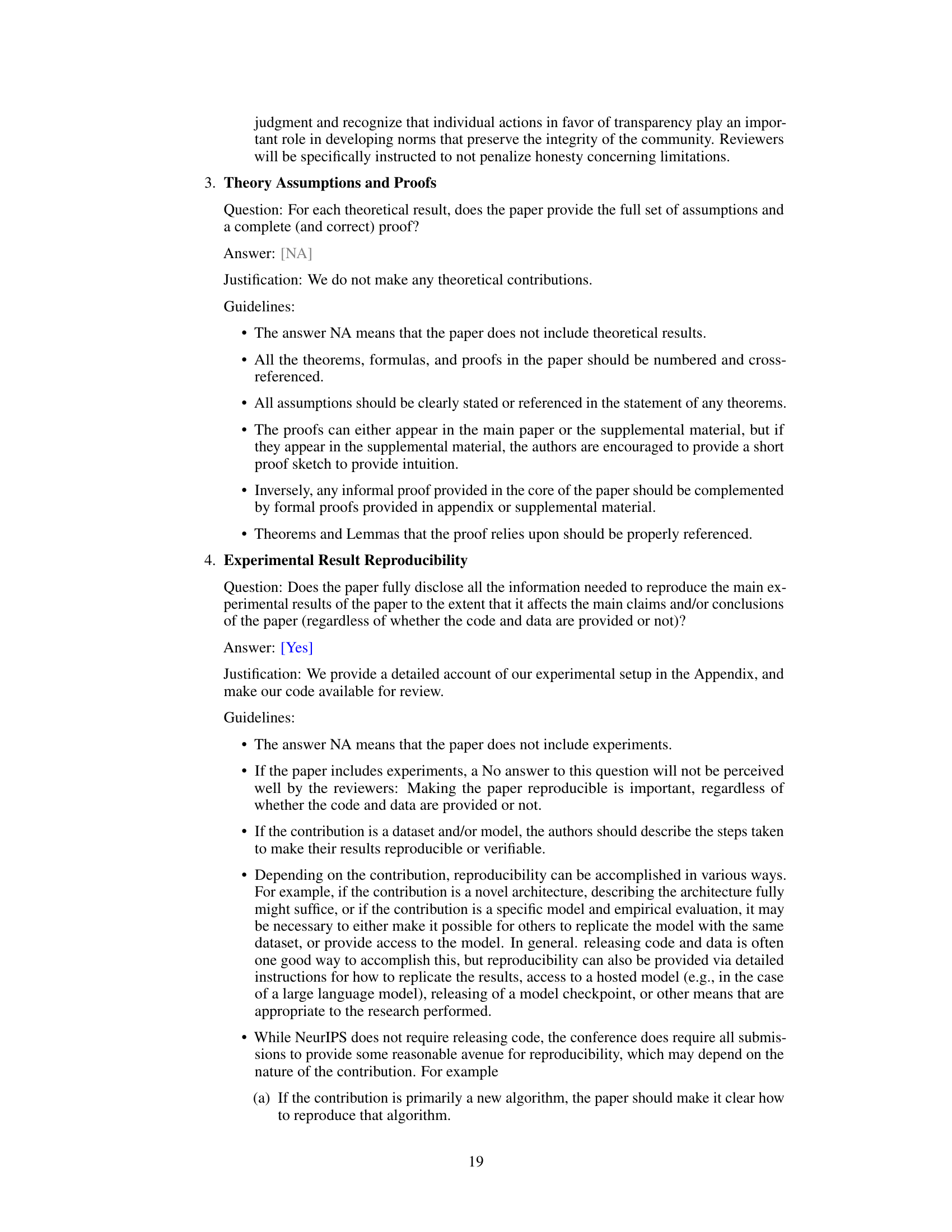

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the QUILL model and its variants under different ablations. It shows the Average Precision (AVEP) and R-precision (R-PREC) metrics across three evaluation datasets: stdlib:ID (in-distribution), stdlib:OOD (out-of-distribution), Unimath, and TypeTopology. The ablations include removing the Taylor expansion, Tree Positional Encoding (Tree PE), and variable resolution. A baseline Transformer model is also included for comparison. The results demonstrate the impact of each architectural choice on the overall performance of the premise selection task.

In-depth insights#

Agda’s ML Ecosystem#

The integration of Agda, a dependently-typed programming language and proof assistant, into the machine learning (ML) ecosystem presents a unique opportunity. Agda’s rigorous type system offers a level of precision and formal verification rarely seen in ML, potentially leading to more robust and reliable models. The creation of a large-scale dataset of Agda programs and proofs is a significant contribution, enabling the development and training of ML models to assist in formal verification tasks. However, challenges remain in effectively representing the complex structural information of dependent types for ML algorithms, requiring innovative approaches. The success of this effort will depend on bridging the gap between the formal rigor of Agda and the empirical nature of ML. While initial results are promising, further research is needed to explore the full potential of this integration, including improved neural architectures, more sophisticated representation techniques, and a wider range of applications.

Type Structure Modeling#

The section on ‘Type Structure Modeling’ is crucial because it addresses a significant gap in existing machine learning for theorem proving. Previous work often relied on shallow textual representations, ignoring the rich structural information inherent in dependently-typed languages like Agda. This paper champions a structural approach, meticulously representing expressions at the sub-type level, capturing the intricacies of dependent types. This methodology, unlike string-based encodings, faithfully reflects the essential mathematical structures, enhancing the model’s ability to understand type relationships and infer relevant lemmas. The creation of QUILL, a novel neural guidance tool, directly benefits from this precise type representation, enabling the model to effectively navigate the complex space of dependently typed proofs and improve the efficiency of premise selection. Therefore, the focus on structural fidelity is not merely a technical detail but a core innovation, promising more accurate and robust machine learning systems in the realm of formal mathematics.

Premise Selection#

Premise selection, a core task in automated theorem proving, involves identifying relevant lemmas or theorems from a set to aid in proving a given goal. This is crucial because the search space of possible proofs can be vast. The paper explores this using a dependently-typed language, Agda, creating a novel dataset of Agda programs and proofs for machine learning. This unique high-resolution dataset allows for the development of a neural architecture, QUILL, that focuses on the structural rather than nominal aspects of dependently-typed programs. This structural approach is vital for handling the complexities of dependent types and is shown to produce promising results in premise selection, surpassing strong baselines. The approach also contrasts with common methods that rely on sequence-based encoders which lack the capacity to capture the intricate structural relationships within dependent types. The work highlights the importance of structural representation learning in automated theorem proving for dependently-typed systems.

Neural Architecture#

The paper introduces a novel neural architecture designed for faithfully representing dependently-typed programs, focusing on structural rather than nominal principles. This is a significant departure from existing sequential approaches, which often rely on string-based representations and lack the capacity to capture the intricate type structure. The architecture leverages efficient attention mechanisms to manage the complexity of large ASTs (Abstract Syntax Trees), and incorporates structured attention to effectively capture hierarchical relationships within the code. Static embeddings are used for primitive symbols, while a sophisticated method employing de Bruijn indexing handles variable references. This design choice allows the model to be agnostic to variable names, enhancing its generalizability. Overall, the architecture prioritizes efficient handling of complex type structures, making it particularly suitable for applications within the realm of dependently-typed programming languages like Agda.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion briefly mentions future work directions, highlighting the need for community feedback to guide their next steps. Improving the data extraction process is a key area, aiming for broader coverage and optimization beyond the standard library used. They also acknowledge the limitations of their current unidirectional pipeline and express interest in creating a bidirectional feedback loop between Agda and machine learning models for improved end-to-end evaluation and real-world application. Further optimization of the modeling approach, potentially through the use of alternative architectures or meta-frameworks like Dedukti for increased interoperability with other languages, is also suggested. The authors show a strong commitment to improving both the dataset and model for broader utility and applicability. Extending the structural representation to encompass a wider range of Agda features is also considered for future development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

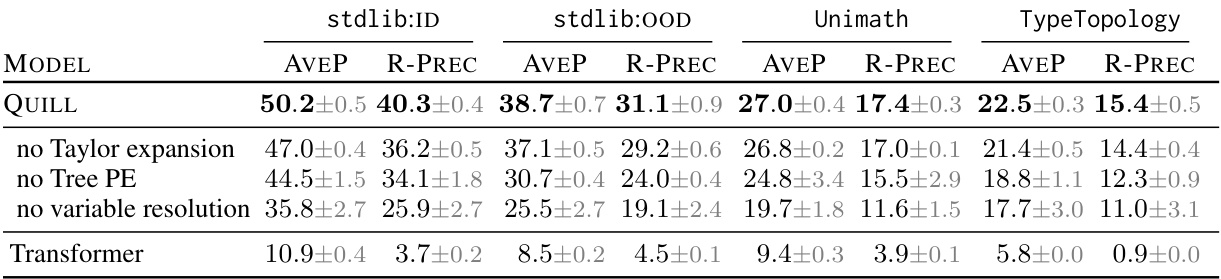

This figure shows the empirical distributions of standardized scores for relevant and irrelevant lemmas from the stdlib:ID evaluation set. The x-axis represents the standardized score, and the y-axis represents the density. The distributions are visualized using kernel density estimation (KDE) plots, with relevant lemmas shown in green and irrelevant lemmas in beige. The figure visually demonstrates the model’s ability to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant lemmas, as evidenced by the clear separation between the distributions. The small overlap between the distributions suggests that the model provides a relatively reliable separation.

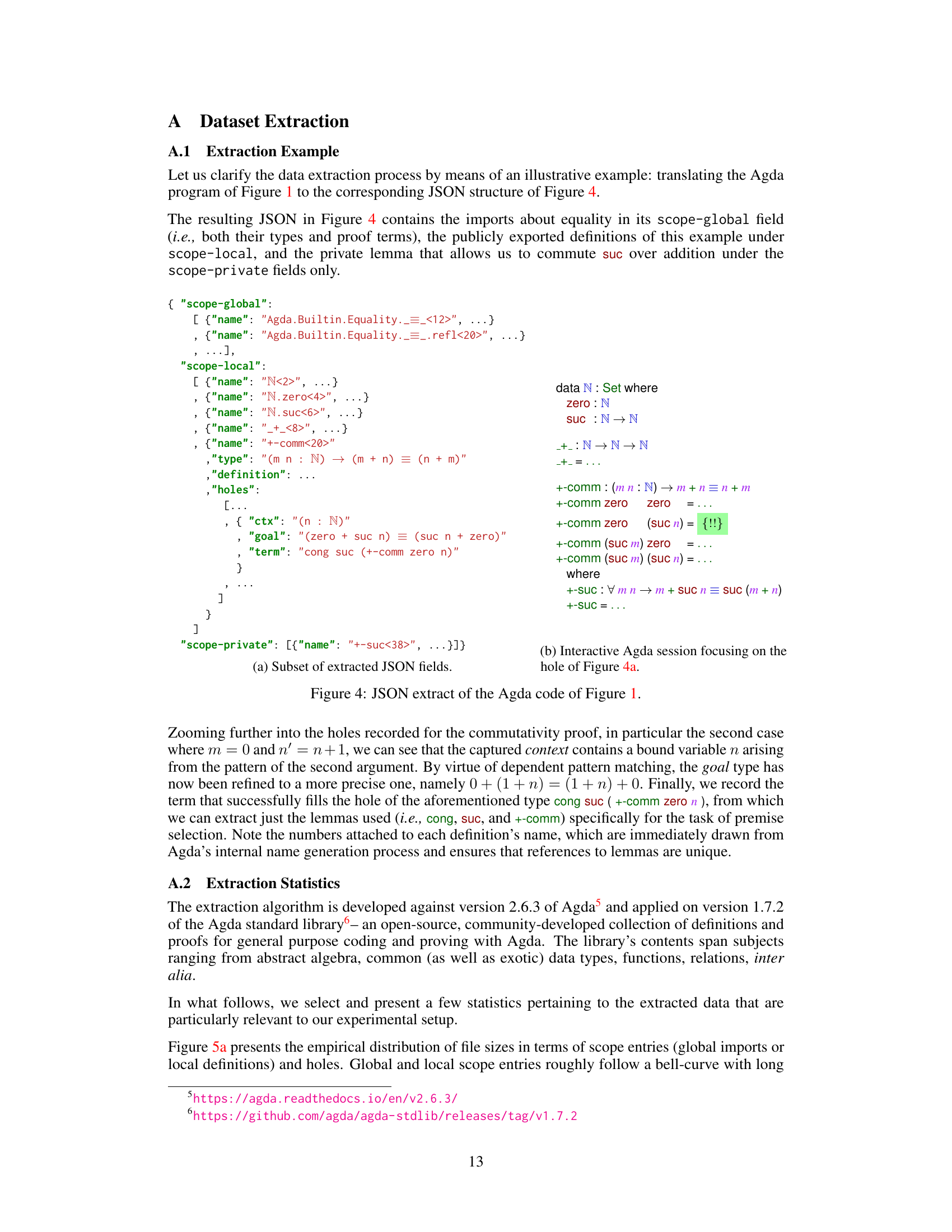

This figure shows a subset of the JSON structure generated by the AGDA2TRAIN tool for the example Agda code in Figure 1. It illustrates how the tool represents the program’s structure, including global imports, local definitions (like the data type N and the addition function), and a private helper lemma (+-suc). It also highlights the representation of a ‘hole’ in the proof, showing its context, the goal to be proven, and the term used to fill the hole. This detailed representation at the sub-type level is key to the paper’s approach.

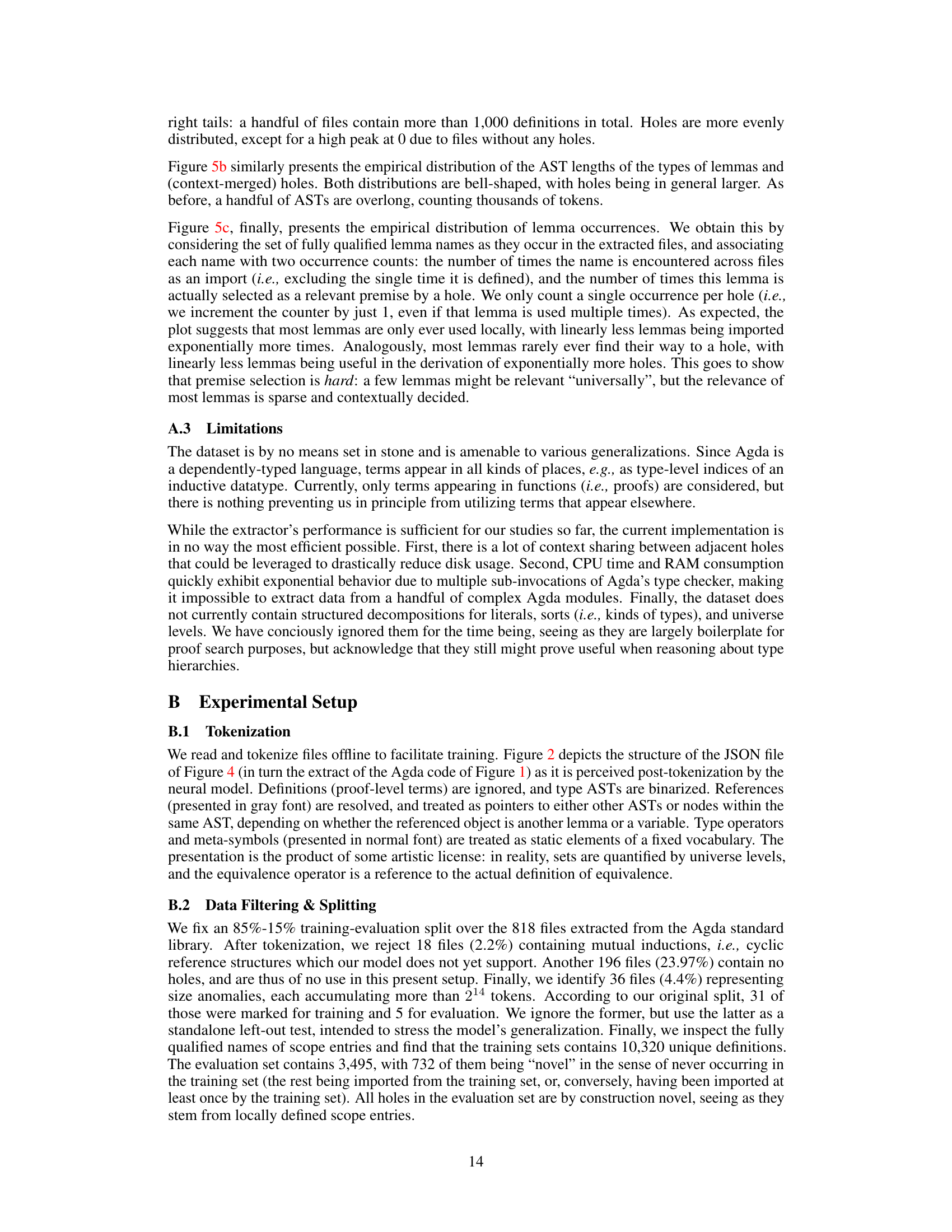

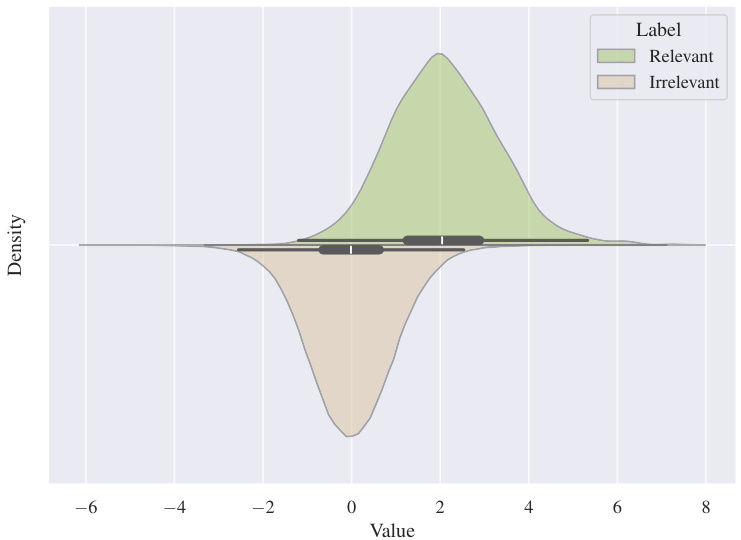

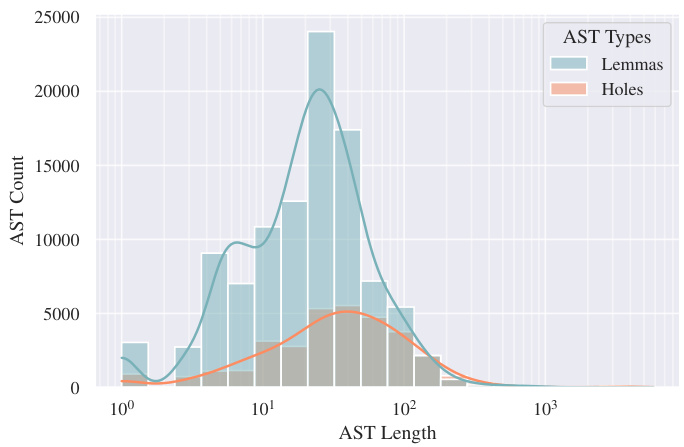

This figure presents three sub-figures that show the distributions of several features of the extracted dataset. (a) shows the distribution of the number of imports, definitions and holes across all files. (b) shows the distribution of the lengths of type ASTs for lemmas and holes. (c) shows the distribution of lemma occurrences across all files, differentiated between imports and premises. These distributions are shown using histograms and kernel density estimates (KDE).

This figure presents three sub-figures showing the distribution of several features of the extracted dataset. (a) shows the distribution of the number of imports, definitions, and holes across files. (b) shows the distribution of Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) lengths for lemmas and holes. (c) shows the distribution of lemma occurrence counts, both as imports and as premises used to fill holes. These distributions are shown as histograms and kernel density estimates (KDEs), and log-transformed for better visualization. The distributions highlight the varying sizes and structures of the data, with some outliers for very large files and ASTs.

This figure shows three subplots visualizing the distributions of several key features of the extracted Agda data. The first subplot (a) displays histograms and kernel density estimates (KDEs) for the counts of imports, definitions, and holes across files. It’s noteworthy that the distribution of holes is more evenly spread than the other two, while imports and definitions show a right skew, indicating some files have a significantly larger number of entries than most. The second subplot (b) presents histograms and KDEs of the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) lengths for lemmas and holes. Again, a similar right-skew is observed, suggesting certain type definitions are considerably more complex than the majority. Finally, subplot (c) illustrates the distribution of lemma occurrences as imports versus use as premises in proof attempts. The distributions show that a small fraction of lemmas is repeatedly used across many files (as imports), while a much larger fraction of lemmas is infrequently used in the dataset.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the QUILL model’s performance on premise selection tasks. It compares the model’s performance across three different datasets (stdlib:ID, stdlib:OOD, Unimath, and TypeTopology), each representing a different level of difficulty and distribution of data. The table reports the Average Precision (AVEP) and R-Precision (R-PREC), which are standard metrics for ranking tasks, for different model variations with ablations to components of the architecture such as Taylor expansion, positional encoding, and variable resolution. The results show the effect of each component on overall performance across all datasets, highlighting the model’s robustness and the importance of each architectural choice.

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the QUILL model’s performance on premise selection tasks across three different datasets: stdlib:ID (in-distribution), stdlib:OOD (out-of-distribution), Unimath, and TypeTopology. The table shows the average precision (AVEP) and R-precision (R-PREC) metrics for the QUILL model under various ablations. The ablations involve removing or modifying key components of the model, such as the Taylor expansion, tree positional encoding, and variable resolution. By comparing the performance of the full model against these ablated versions, the authors assess the contribution of each component to the overall performance. The results highlight the importance of each structural component of the model for achieving high performance.

Full paper#