TL;DR#

Semantic segmentation and image synthesis are typically tackled as separate tasks. Existing methods for semantic segmentation often struggle with the contradiction between the randomness of diffusion model outputs and the uniqueness of segmentation results. Image synthesis models, frequently GAN or diffusion based, often lack bi-directional capabilities. This paper introduces SemFlow to address this issue.

SemFlow leverages the theory of rectified flow to create a unified model for both tasks. It models the tasks as a pair of reverse problems, using an ordinary differential equation (ODE) to transport between image and semantic mask distributions. The symmetric training objective allows for reversible transitions, solving the issues of randomness and irreversibility. A finite perturbation approach is introduced to enhance the diversity of generated images in the synthesis task. Experimental results demonstrate that SemFlow achieves competitive performance in both semantic segmentation and image synthesis.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents a novel unified framework, SemFlow, for semantic segmentation and image synthesis. It addresses limitations of existing methods by leveraging rectified flow, improving both accuracy and efficiency, and offering new avenues for research in low-level and high-level vision integration. This is highly relevant given the current interest in multimodal AI and efficient, reversible models.

Visual Insights#

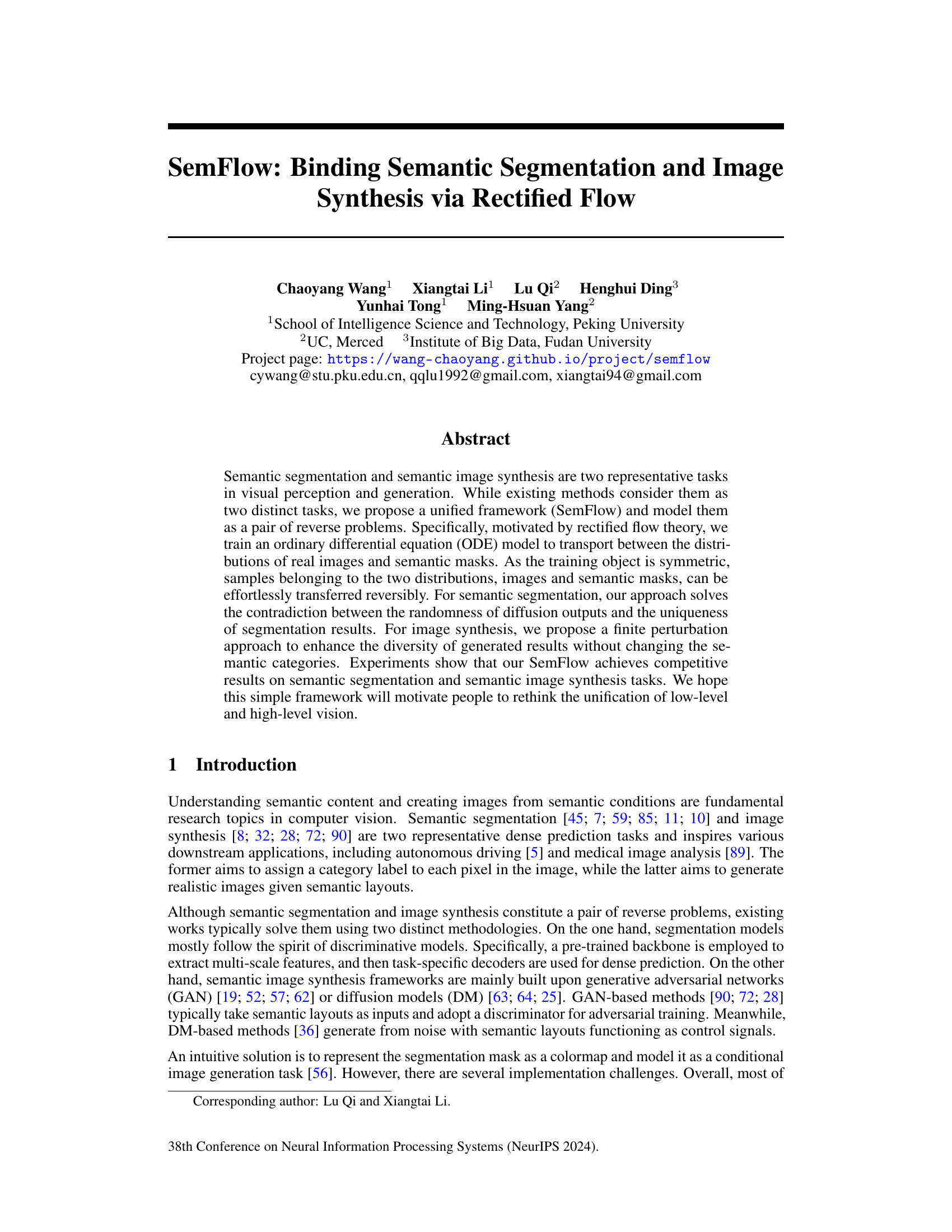

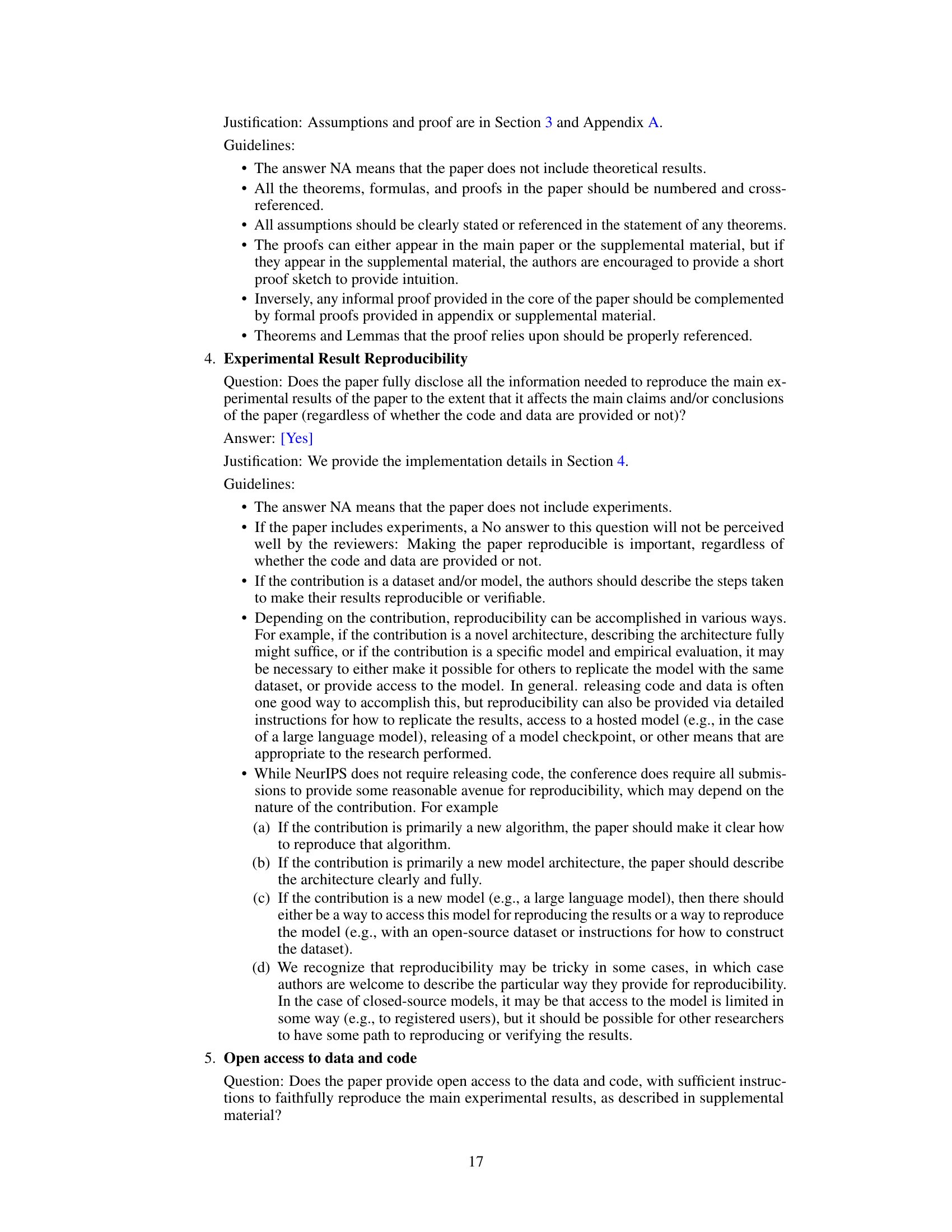

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the SemFlow model, which bridges semantic segmentation and semantic image synthesis using rectified flow. It shows how the model treats these two tasks as reverse problems, sharing the same ordinary differential equation (ODE) model but differing only in the direction of the flow. The figure highlights the use of a finite perturbation operation on the semantic masks to achieve multi-modal generation in image synthesis, while maintaining the original semantic labels. Data samples, semantic centroids (anchors), and the scale of the perturbation are visually represented.

read the caption

Figure 1: Rectified flow bridges semantic segmentation (SS) and semantic image synthesis (SIS). SS and SIS are modeled as a pair of transportation problems between the distributions of images and masks. They share the same ODE and only differ in the direction of the velocity field. We propose a finite perturbation operation on the mask to enable multi-modal generation without changing the semantic labels. Grey dots represent data samples. Colored dots represent semantic centroids, also known as anchors in Eq. 7. Colored bubbles represent the scale of perturbation.

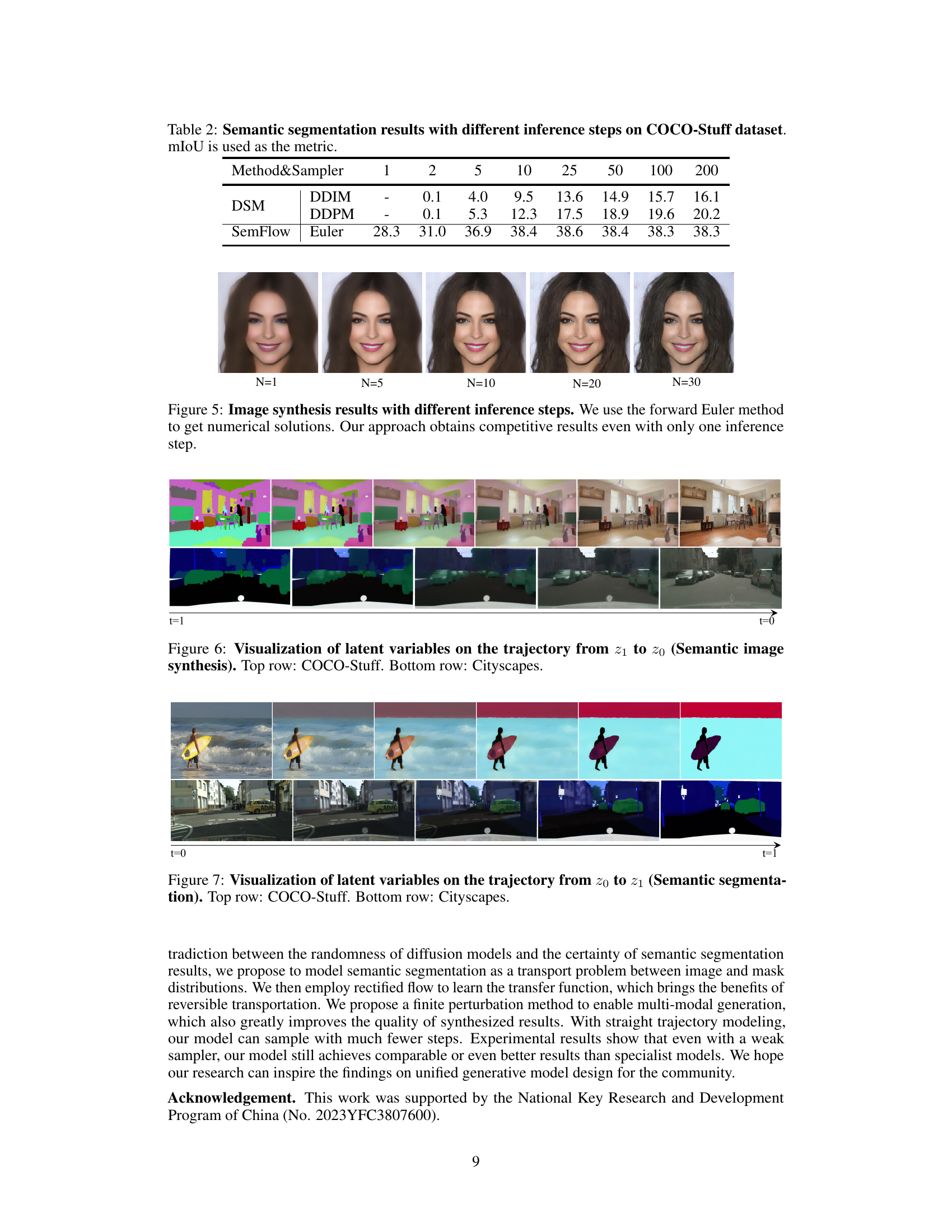

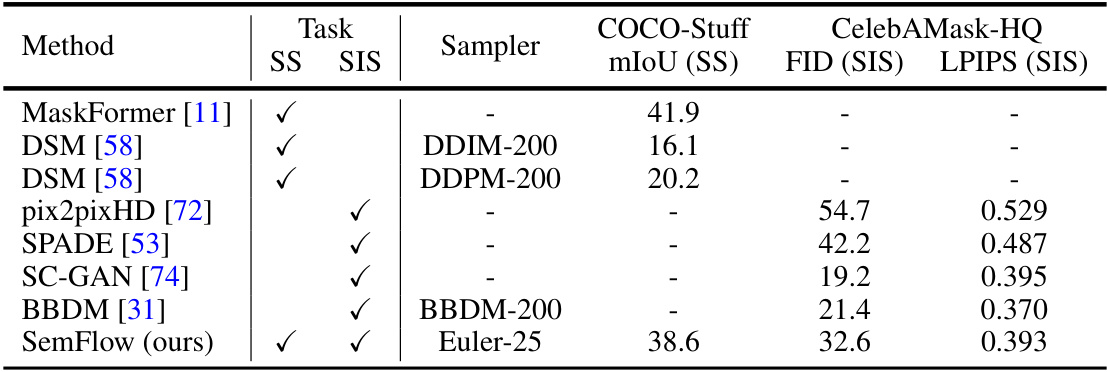

🔼 This table presents a comparison of semantic segmentation and semantic image synthesis results on the COCO-Stuff dataset using different methods. It shows the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) for semantic segmentation, and the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) for semantic image synthesis. The table also indicates which sampler and the number of inference steps were used for each method.

read the caption

Table 1: Semantic segmentation results on COCO-Stuff dataset. SS and SIS represents semantic segmentation and semantic image synthesis, respectively. Sampler-N means the usage of a specific sampler with N inference steps.

In-depth insights#

Rectified Flow Bridge#

The concept of a “Rectified Flow Bridge” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a novel method that leverages rectified flow to connect two distinct tasks or domains within a unified framework. Rectified flow itself is a technique that transforms data distributions using ordinary differential equations (ODEs), offering advantages such as computational efficiency and deterministic behavior. A bridge built upon this foundation would likely aim to seamlessly transfer information or representations between the two connected areas, potentially resolving inconsistencies or limitations present when the tasks are treated in isolation. This might involve transferring knowledge gained from one task to improve performance in the other, or creating a bi-directional pathway facilitating information exchange. The strength of such a bridge lies in its capacity to overcome inherent limitations of separate approaches, thus fostering a more cohesive and potentially superior overall solution. Examples could include unifying image synthesis and semantic segmentation, or perhaps high-level and low-level vision tasks.

Unified Framework#

A unified framework in a research paper typically aims to integrate previously disparate concepts or methods under a single theoretical umbrella. This approach offers several advantages. Firstly, it promotes simplicity and elegance, reducing redundancy and allowing for a more holistic understanding of the subject matter. Secondly, a unified framework can reveal unexpected connections and synergies between seemingly unrelated areas. This may lead to novel insights and the development of more powerful, versatile, and efficient tools. However, the development of a successful unified framework requires careful consideration. Robustness and generalizability are crucial, ensuring the framework is not overly specific or reliant on unrealistic assumptions. Furthermore, a clear and concise explanation of the framework’s principles and mechanics is vital for ensuring it is both widely understood and readily adopted by the broader research community. Finally, a successful unified framework should provide a basis for future extensions and developments, paving the way for further advancements in the field.

Finite Perturbation#

The concept of ‘Finite Perturbation’ in the context of a research paper likely revolves around introducing controlled, small-scale noise or variations to input data, specifically semantic masks in this case. This technique is particularly relevant in generative models, especially those dealing with semantic image synthesis. The core idea is to enhance the diversity of generated outputs without altering the fundamental semantic information. By adding a limited amount of noise, the model isn’t constrained to a single, deterministic output for a given semantic mask, thus leading to multiple plausible image realizations. This addresses a key limitation of many image generation models which often produce repetitive results. The ‘finite’ aspect emphasizes that the perturbations remain within defined bounds, preventing the model from generating semantically incorrect images. This controlled randomness improves the model’s ability to generate diverse yet consistent outputs, addressing a major challenge in semantic image synthesis where preserving semantic consistency while producing varied results is crucial. The effectiveness of this method would be demonstrated through quantitative metrics and visual examples showcasing the improved diversity of the generated images.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to understand their individual contributions. In this context, an ablation study might involve removing or altering the perturbation operation to assess its impact on the model’s performance in both semantic segmentation and image synthesis tasks. Removing the perturbation might lead to a decrease in the diversity of generated images, since the model would no longer be able to sample from varied semantic-invariant distributions. Conversely, modifying the perturbation parameters (e.g., changing the amplitude or distribution) could reveal how the method’s robustness and fidelity relate to the strength of noise added to the semantic masks. Such experimentation allows researchers to pinpoint the essential elements of their approach, providing strong evidence for design choices and demonstrating a deeper understanding of their impact on the overall model’s effectiveness. The results would ideally show a clear correlation between the presence/absence or modification of specific components and the resultant metrics for both segmentation accuracy and image quality.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from the SemFlow paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending SemFlow to handle more complex and diverse data modalities beyond images and semantic masks would significantly enhance its applicability across broader computer vision tasks. This could involve incorporating other forms of semantic information such as depth maps, instance segmentation masks, or even textual descriptions. Another critical area for future work is improving the efficiency of the training process, focusing on reducing computational costs and memory usage, thus making it suitable for larger datasets and more complex architectures. Investigating alternative ODE solvers and exploring different rectified flow formulations could further enhance the model’s performance and convergence speed. The multi-modal generation aspect of SemFlow requires further exploration to fully understand the underlying mechanism and potentially improve the quality and diversity of the generated samples. Finally, thorough benchmarking against a broader range of state-of-the-art methods on various datasets is crucial to establish its strengths and limitations definitively.

More visual insights#

More on figures

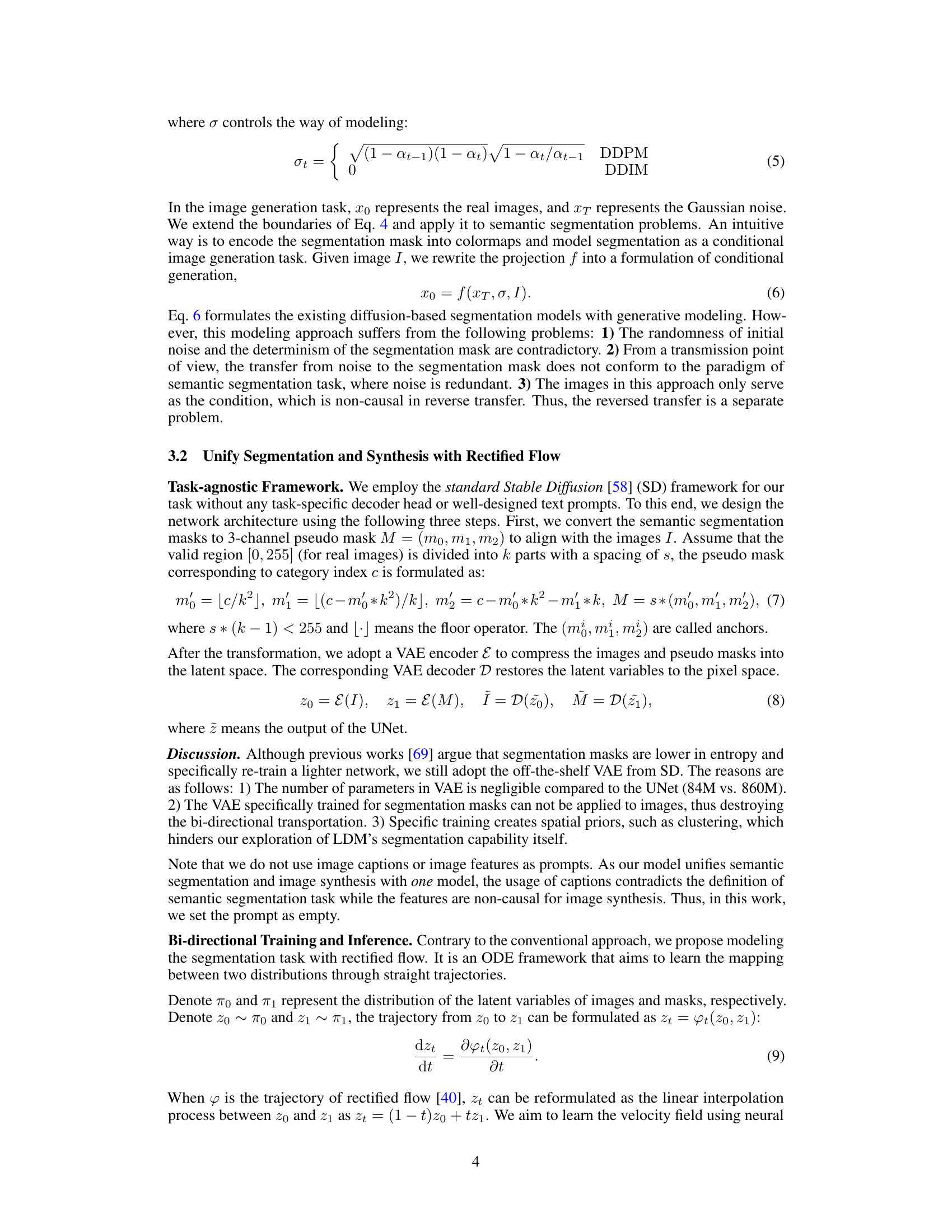

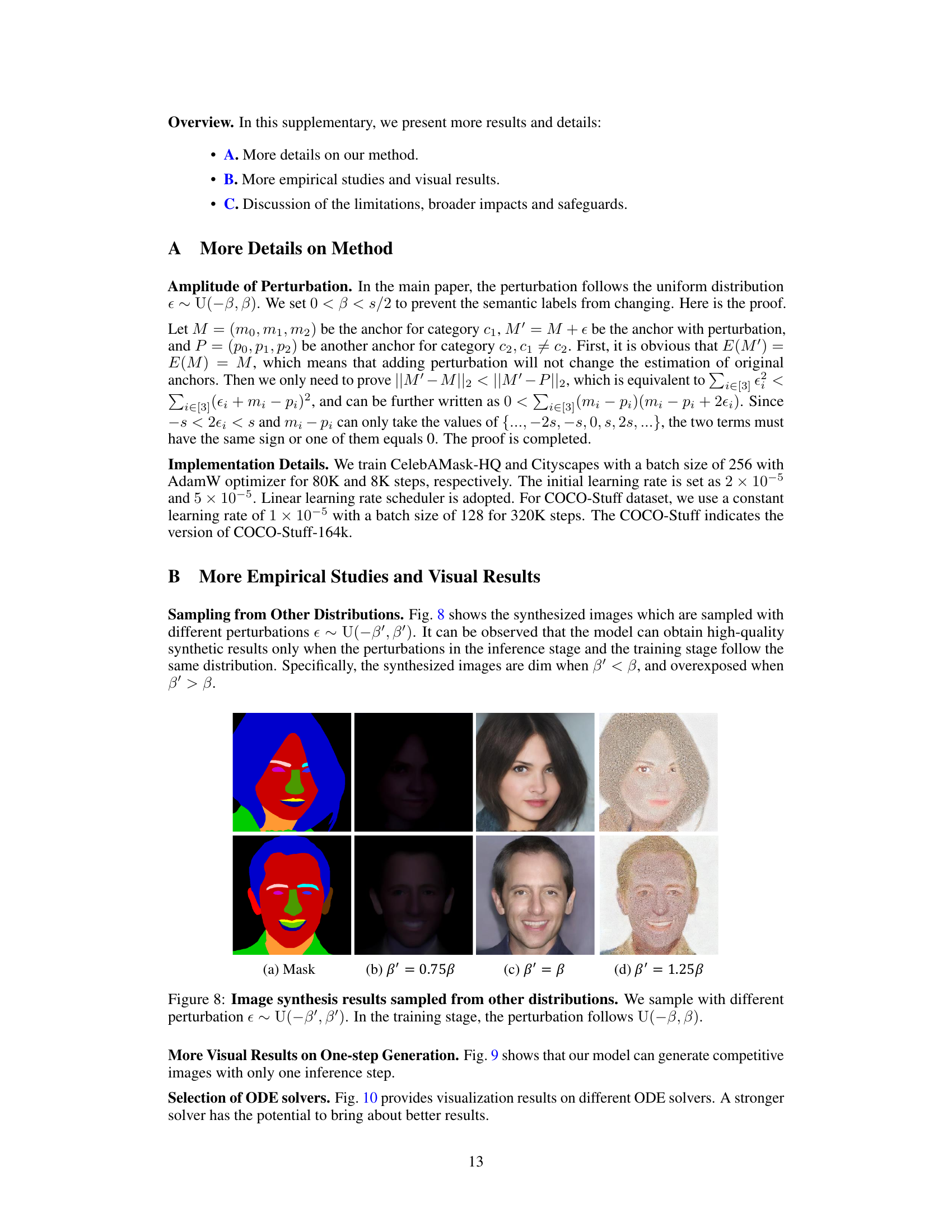

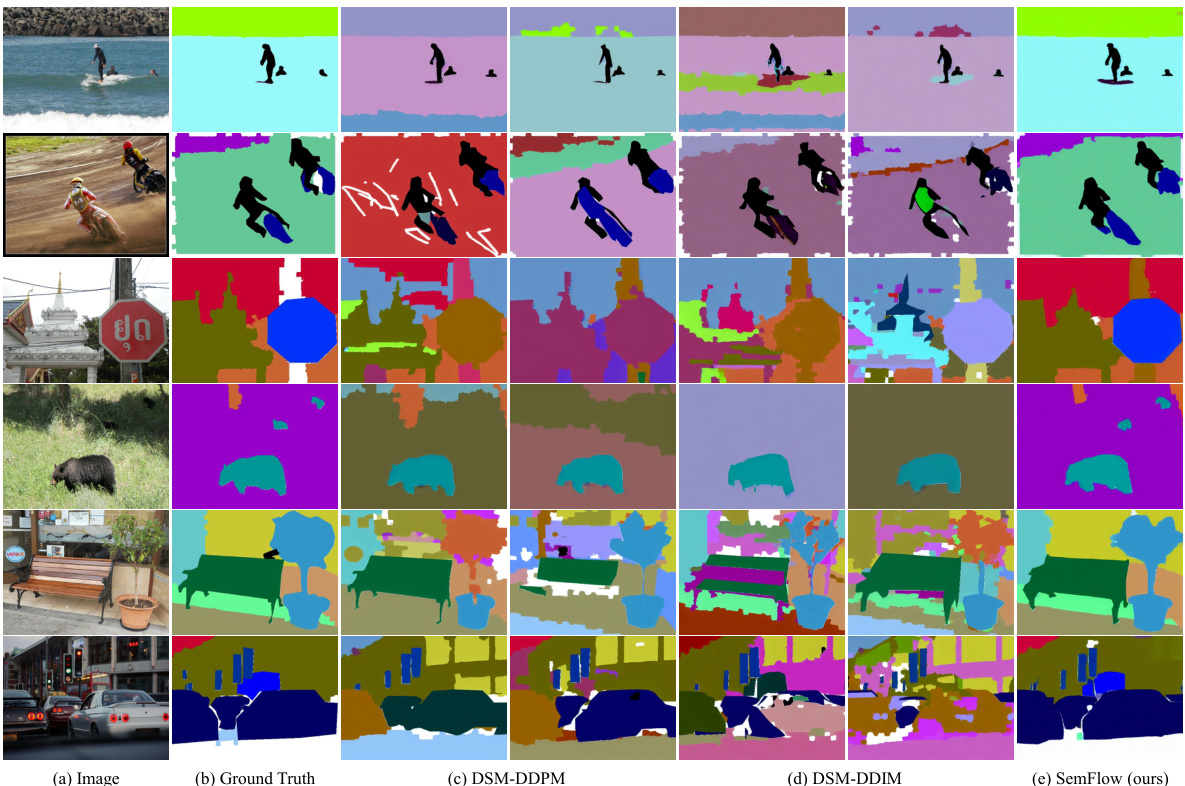

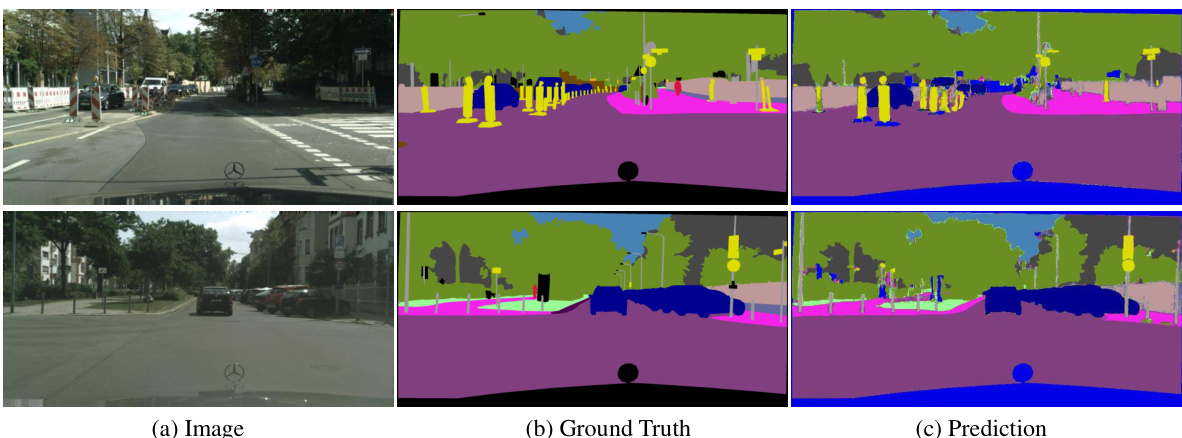

🔼 This figure compares the semantic segmentation results of SemFlow against two different diffusion-based segmentation models (DSMs) on the COCO-Stuff dataset. It showcases how SemFlow produces significantly more accurate and consistent segmentation results compared to DSMs, which are highly sensitive to random seed variations, leading to inconsistent predictions. The color-coding in the ground truth image represents different semantic categories.

read the caption

Figure 2: Semantic segmentation results on COCO-Stuff dataset. For the ground truth, each color reflects the value of anchors (Eq. 7), which corresponds to one semantic category, and the color white indicates the ignored regions. The predictions of DSM vary considerably under different random seeds.

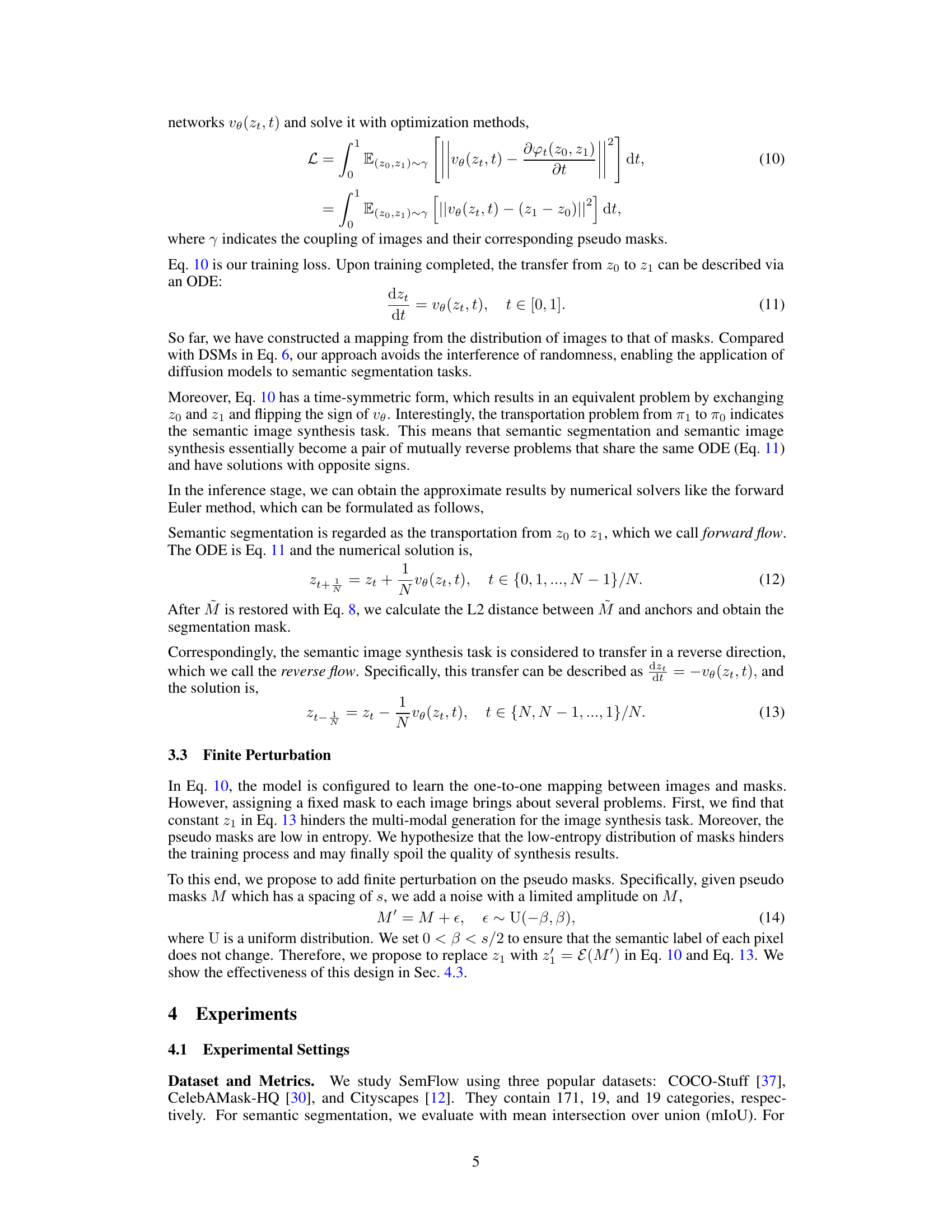

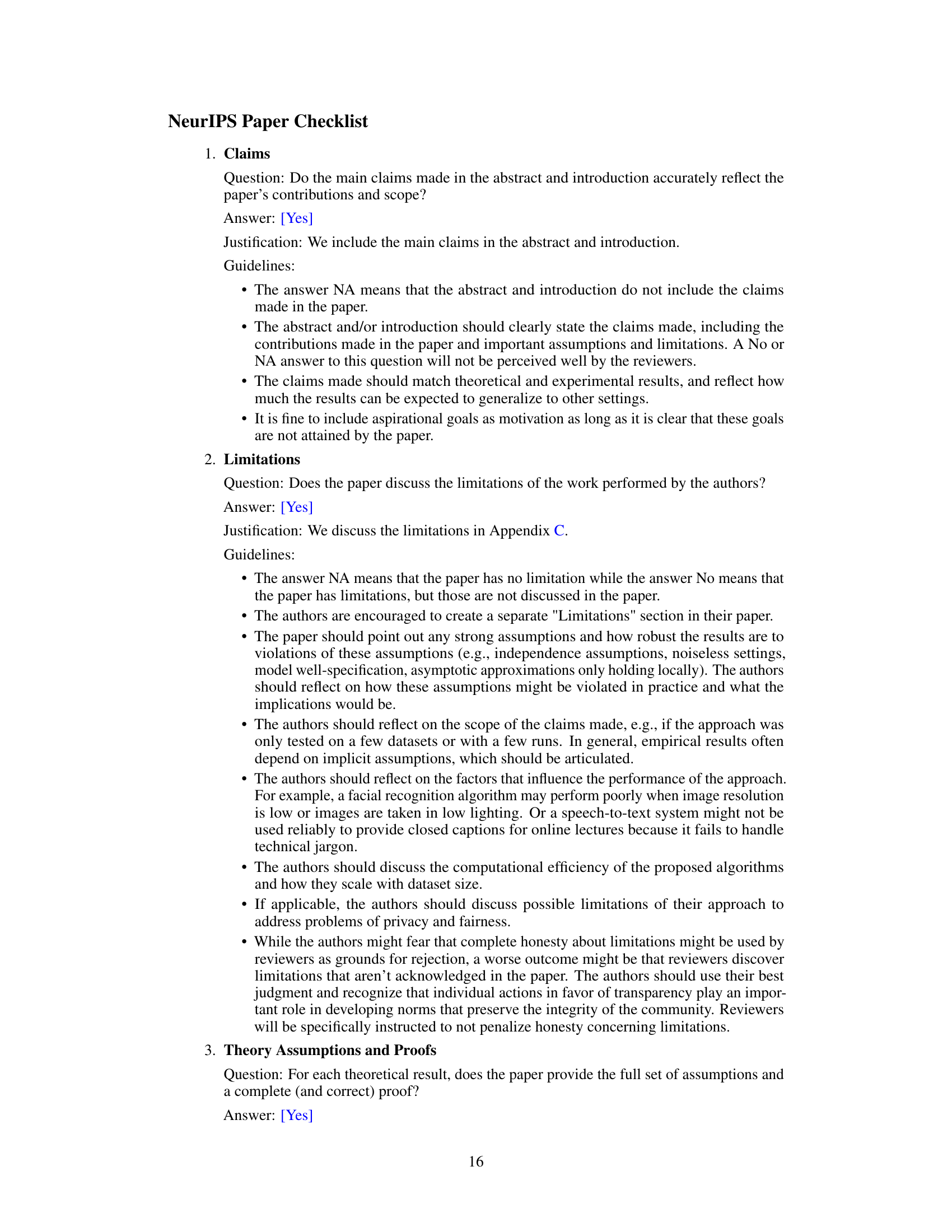

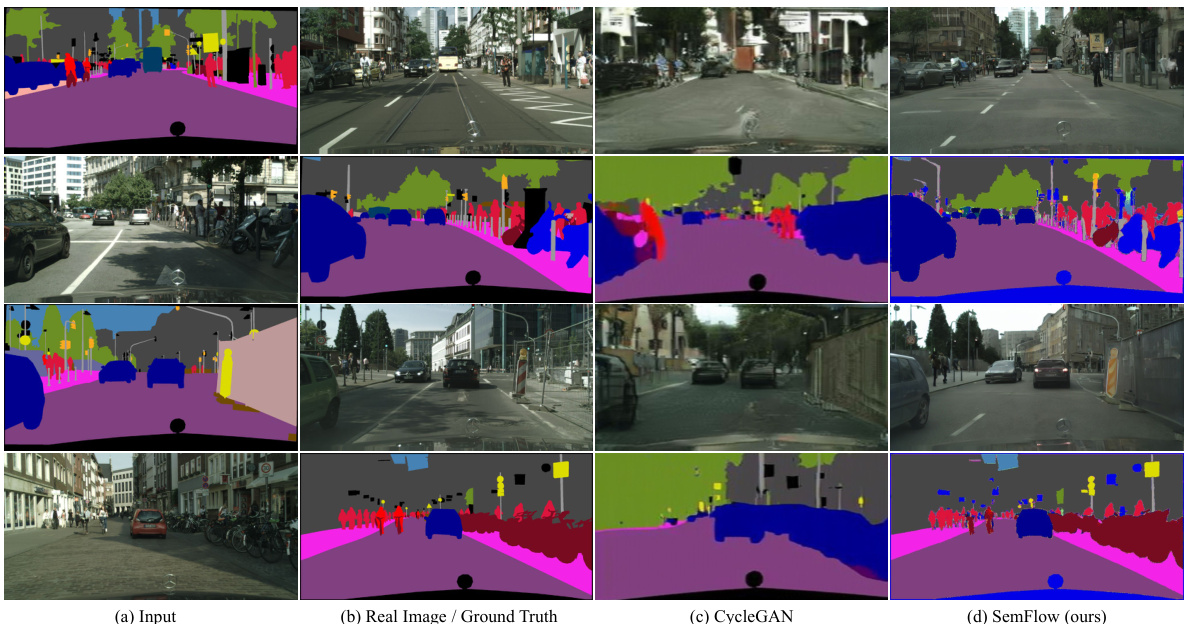

🔼 This figure compares the performance of SemFlow and CycleGAN on semantic segmentation and image synthesis tasks using the Cityscapes dataset. The top row shows the input semantic layouts. The second row displays the ground truth images. The third row shows the results generated by CycleGAN, and the bottom row shows the results from SemFlow. The color black in the ground truth images indicates regions that were ignored during training. SemFlow’s segmentation results are color-coded according to the Cityscapes dataset’s label scheme.

read the caption

Figure 3: Semantic segmentation and semantic image synthesis results on Cityscapes dataset. The color black in the ground truth indicates the ignored region. The segmentation results of SemFlow are colored following [12].

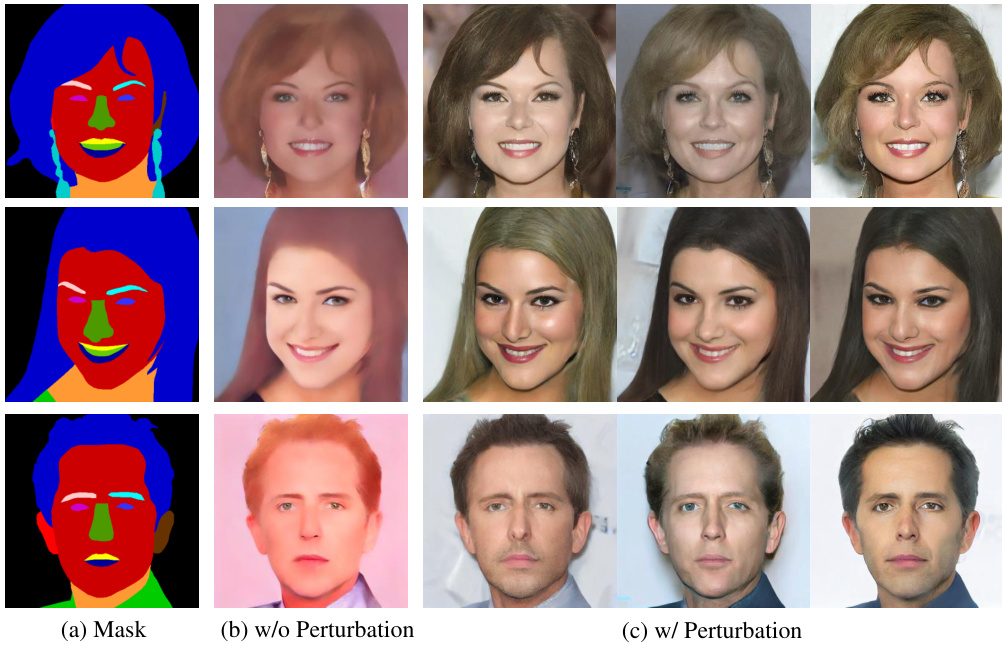

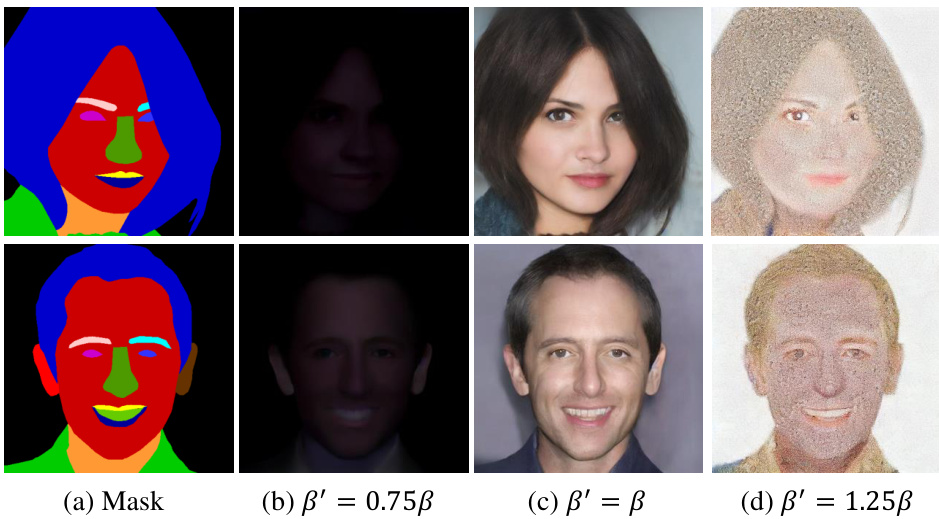

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the finite perturbation operation (Eq. 14) on semantic image synthesis using the CelebAMask-HQ dataset. The leftmost column displays the semantic masks, color-coded to represent different semantic components. The middle column shows synthesis results without perturbation, demonstrating uni-modal generation. The right column displays synthesis results with perturbation, illustrating the model’s ability to generate diverse results for the same semantic mask, achieving multi-modal generation.

read the caption

Figure 4: Semantic image synthesis results on CelebAMask-HQ dataset. Semantic masks are colored to show different semantic components. SemFlow w/ Perturbation indicates the finite perturbation operation in Eq. 14.

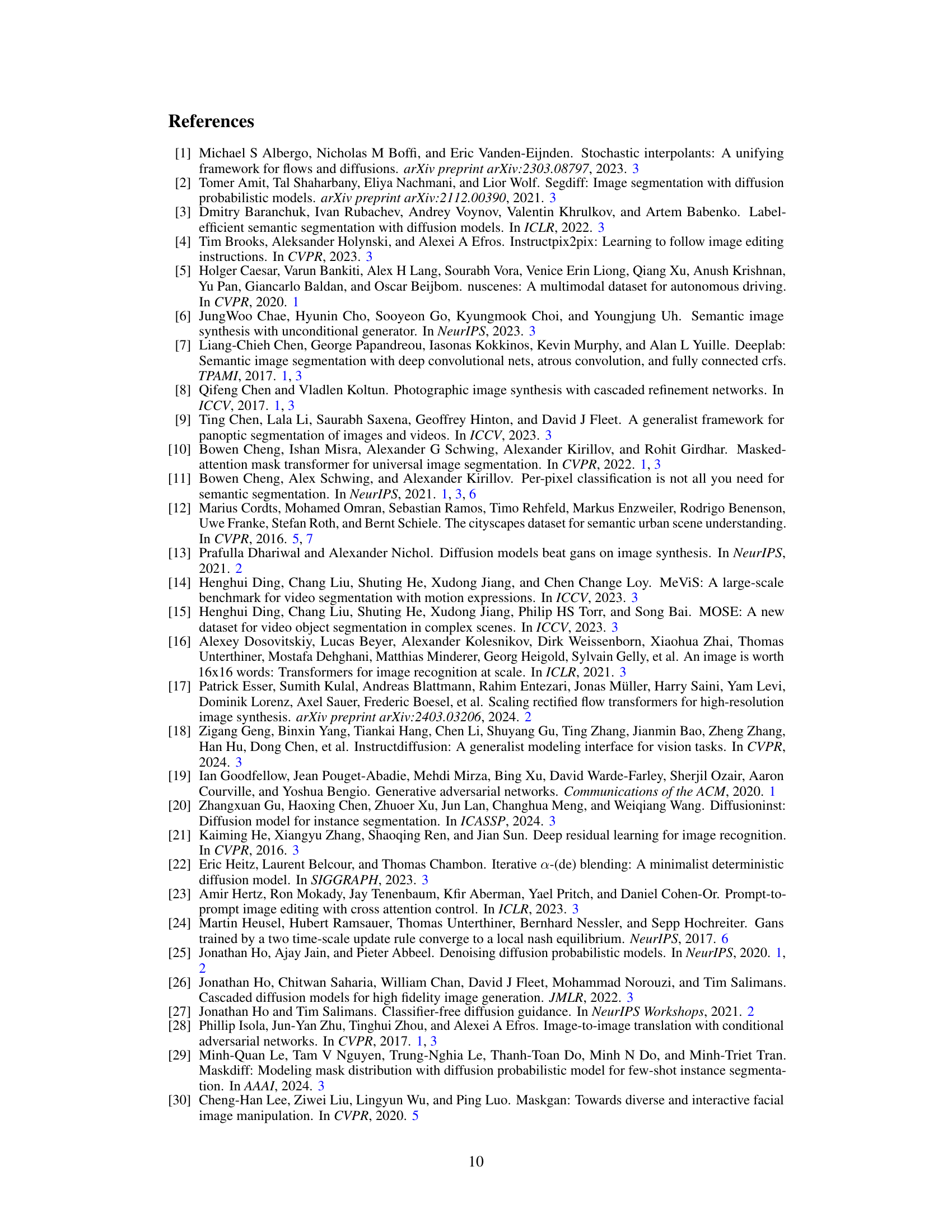

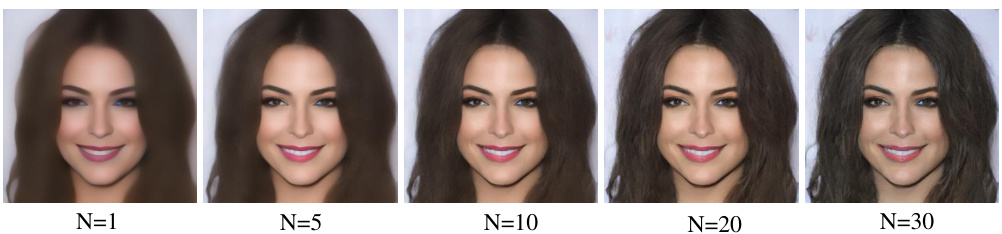

🔼 This figure shows the image synthesis results using the forward Euler method with different numbers of inference steps (N=1, 5, 10, 20, 30). It demonstrates that the model can generate competitive results even with a single inference step, highlighting the efficiency of the method.

read the caption

Figure 5: Image synthesis results with different inference steps. We use the forward Euler method to get numerical solutions. Our approach obtains competitive results even with only one inference step.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concept of SemFlow, a unified framework for semantic segmentation and semantic image synthesis. It models these two tasks as reverse problems, connected by a rectified flow ODE. The ODE transports samples between the distributions of images and semantic masks, enabling reversible transfer. A key innovation is the finite perturbation of masks, which introduces multi-modal generation for image synthesis without altering semantic labels.

read the caption

Figure 1: Rectified flow bridges semantic segmentation (SS) and semantic image synthesis (SIS). SS and SIS are modeled as a pair of transportation problems between the distributions of images and masks. They share the same ODE and only differ in the direction of the velocity field. We propose a finite perturbation operation on the mask to enable multi-modal generation without changing the semantic labels. Grey dots represent data samples. Colored dots represent semantic centroids, also known as anchors in Eq. 7. Colored bubbles represent the scale of perturbation.

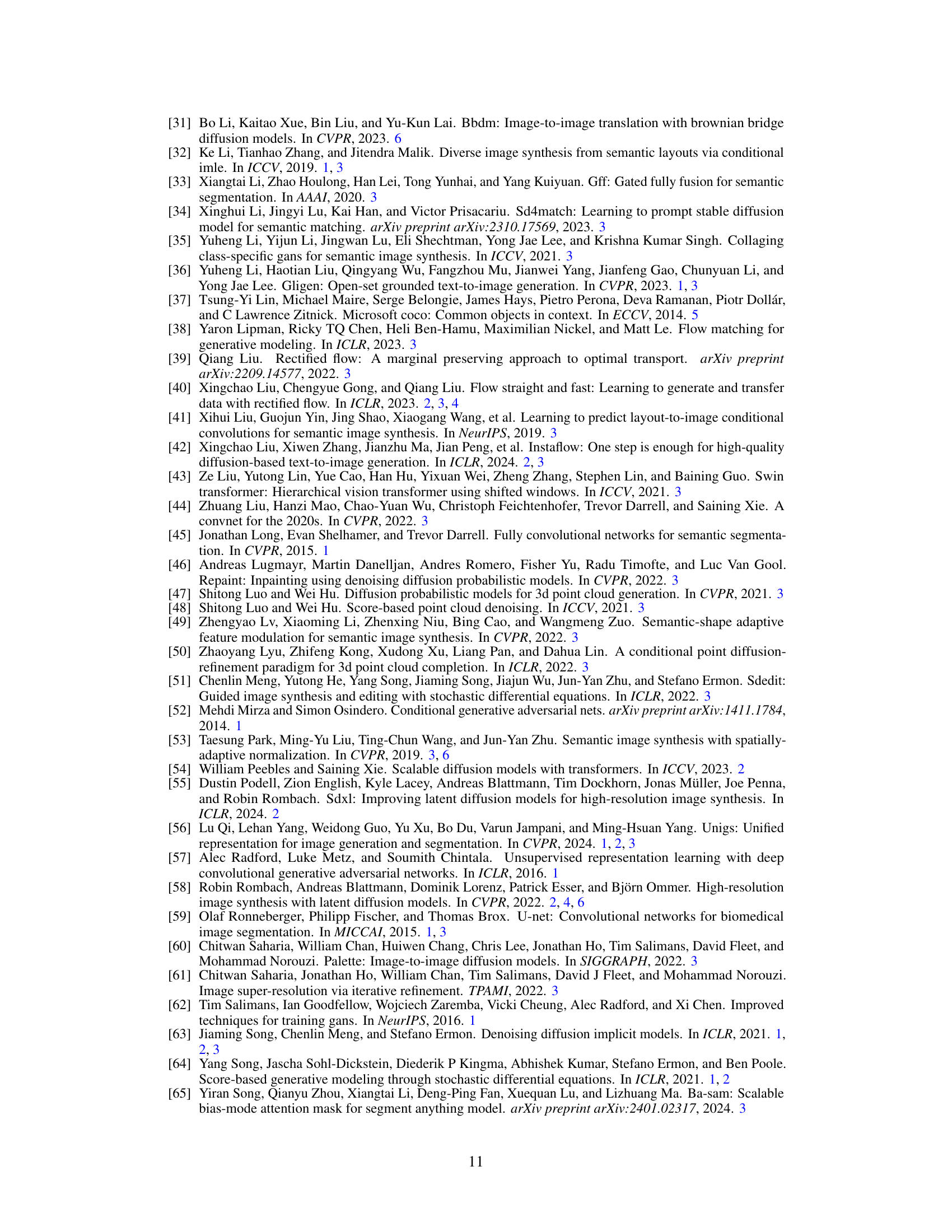

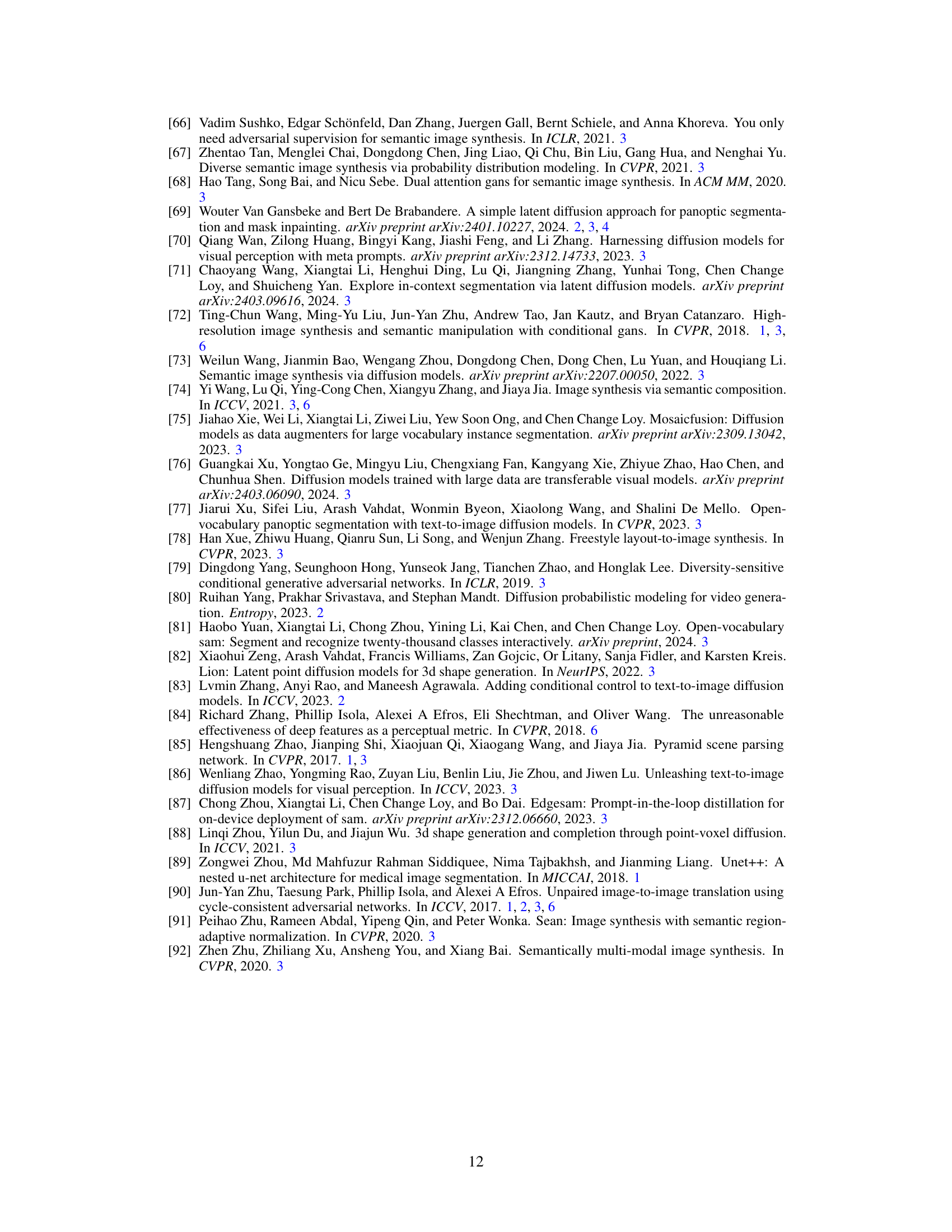

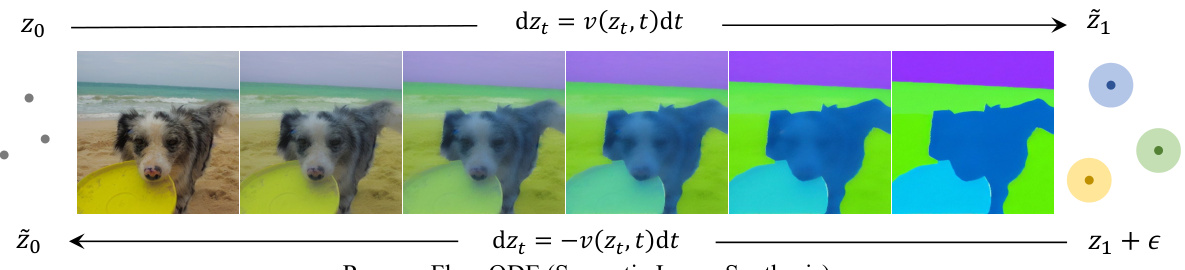

🔼 This figure visualizes the latent variables along the trajectory from the image distribution (z0) to the semantic mask distribution (z1) for semantic segmentation. It demonstrates the smooth transition between the two distributions using the rectified flow method. The top row shows examples from the COCO-Stuff dataset, and the bottom row shows examples from the Cityscapes dataset. The visualization highlights the effectiveness of the rectified flow in learning a smooth and deterministic mapping between images and their corresponding semantic masks.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualization of latent variables on the trajectory from z0 to z1 (Semantic segmentation). Top row: COCO-Stuff. Bottom row: Cityscapes.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of the finite perturbation operation (introduced in Equation 14 of the paper) on the quality of semantic image synthesis. The top row shows a semantic mask, the results without perturbation, results with the ideal perturbation, and results with excessive perturbation. The bottom row shows the same for a different mask. The results illustrate that applying a finite perturbation to the input semantic masks enables the model to generate more diverse and realistic images, while insufficient or excessive perturbation negatively impacts the image quality.

read the caption

Figure 4: Semantic image synthesis results on CelebAMask-HQ dataset. Semantic masks are colored to show different semantic components. SemFlow w/ Perturbation indicates the finite perturbation operation in Eq. 14.

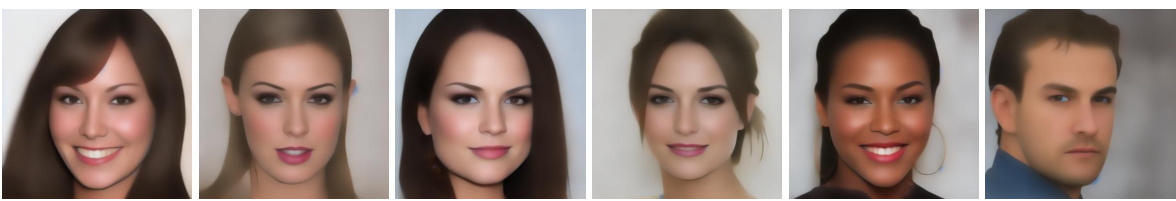

🔼 This figure shows the results of semantic image synthesis on the CelebAMask-HQ dataset. The leftmost image shows the semantic mask used as input. The next three images show the results generated by the SemFlow model without perturbation, demonstrating the model’s tendency towards uni-modal generation with a fixed mask. The final three images show results from the SemFlow model with the addition of finite perturbation, showcasing the model’s increased capacity for multi-modal image synthesis.

read the caption

Figure 4: Semantic image synthesis results on CelebAMask-HQ dataset. Semantic masks are colored to show different semantic components. SemFlow w/ Perturbation indicates the finite perturbation operation in Eq. 14.

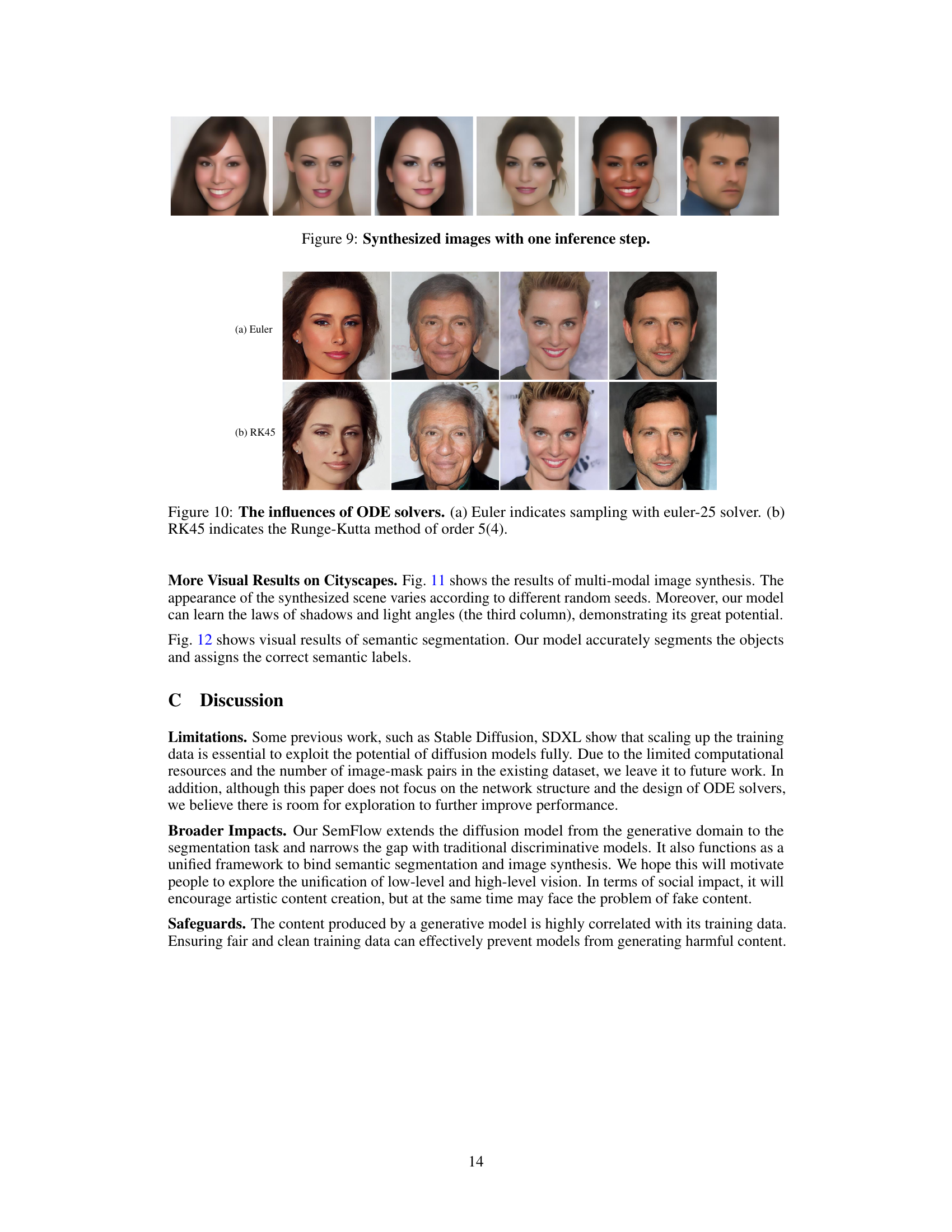

🔼 This figure compares the image synthesis results obtained using two different ODE solvers: Euler and RK45. The top row shows results using the Euler method with 25 steps, while the bottom row shows results using the RK45 method (a Runge-Kutta method of order 5(4)). The comparison highlights the impact of the choice of solver on the quality of the generated images. RK45, being a more sophisticated and accurate method, may produce slightly better results.

read the caption

Figure 10: The influences of ODE solvers. (a) Euler indicates sampling with euler-25 solver. (b) RK45 indicates the Runge-Kutta method of order 5(4).

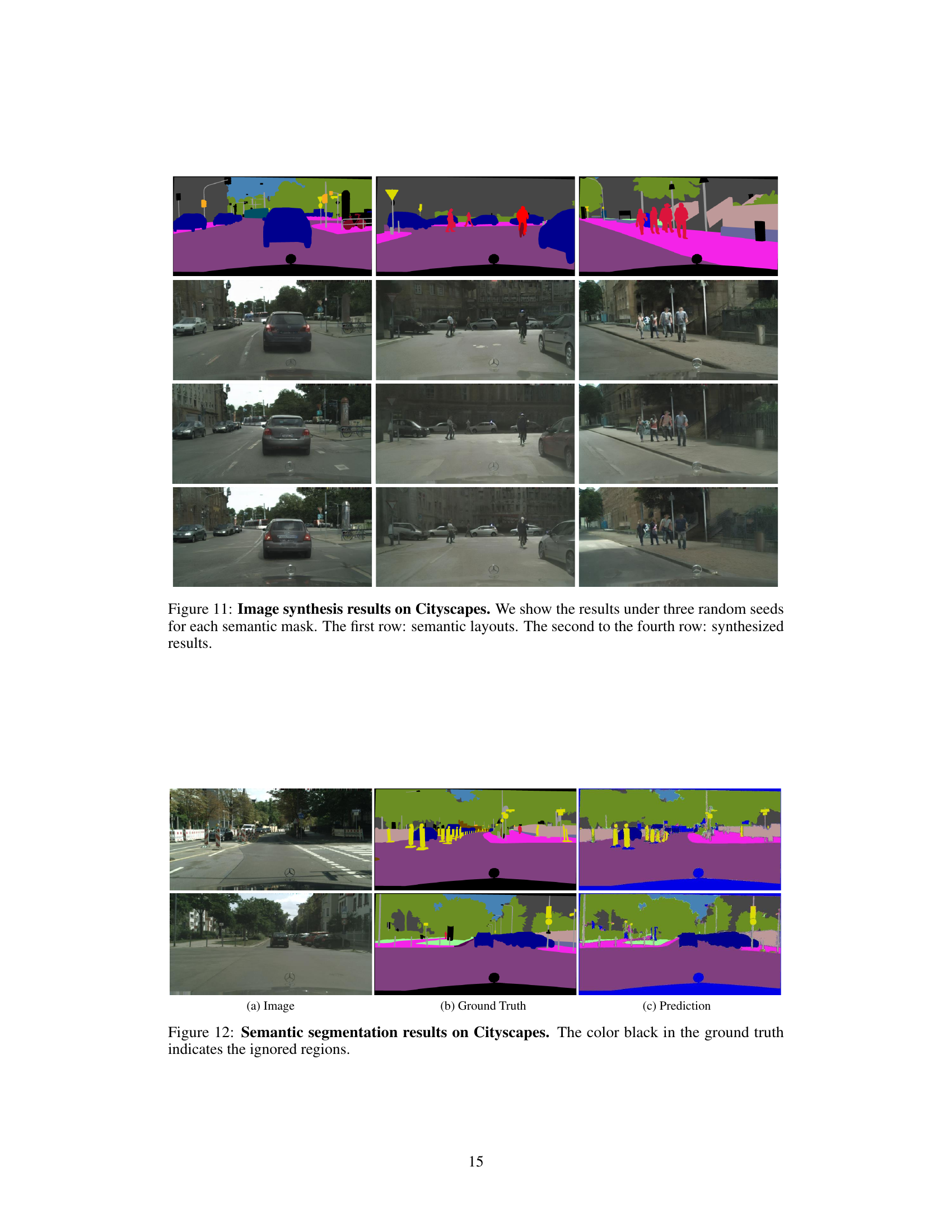

🔼 This figure demonstrates the results of semantic image synthesis on the Cityscapes dataset using the SemFlow model. It showcases the model’s ability to generate diverse results from the same semantic layout by varying random seeds, thus producing multi-modal outputs. The top row shows input semantic masks or layouts, which are then processed by the model to generate image synthesis results in the subsequent rows. The diversity in generated images, even for the same input, highlights the model’s capability for multi-modal generation.

read the caption

Figure 11: Image synthesis results on Cityscapes. We show the results under three random seeds for each semantic mask. The first row: semantic layouts. The second to the fourth row: synthesized results.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concept of SemFlow, which models semantic segmentation and image synthesis as a pair of reverse problems using rectified flow. It shows how a shared ordinary differential equation (ODE) model transports between the distributions of images and semantic masks, enabling reversible transfer between them. The figure highlights the use of a finite perturbation operation on masks to allow for multi-modal generation in image synthesis while maintaining semantic consistency. Data samples are represented by grey dots, semantic centroids by colored dots, and perturbation scale by colored bubbles.

read the caption

Figure 1: Rectified flow bridges semantic segmentation (SS) and semantic image synthesis (SIS). SS and SIS are modeled as a pair of transportation problems between the distributions of images and masks. They share the same ODE and only differ in the direction of the velocity field. We propose a finite perturbation operation on the mask to enable multi-modal generation without changing the semantic labels. Grey dots represent data samples. Colored dots represent semantic centroids, also known as anchors in Eq. 7. Colored bubbles represent the scale of perturbation.

Full paper#