TL;DR#

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), fundamental to deep learning, often exhibits heavy-tailed distributions of neural network parameters. This heavy-tailed behavior is linked to improved generalization and escaping poor local minima, yet understanding its origin and implications remains crucial. Existing research offers only qualitative descriptions of this behavior.

This paper tackles the problem by analyzing a continuous diffusion approximation of SGD called homogenized SGD (hSGD). Using a regularized linear regression framework, researchers derived explicit upper and lower bounds on the tail index. Numerical experiments successfully validated these bounds, linking hyperparameters to tail index and suggesting Student-t distributions to model parameter distribution. This work offers a more precise and quantifiable understanding of heavy-tailed behavior in SGD, a significant advancement compared to prior work.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it provides a novel quantitative analysis of heavy-tailed phenomena in SGD, a cornerstone of deep learning. The explicit bounds on the tail-index and validation through experiments offer significant insights for improving model generalization and escaping suboptimal local minima. This opens new avenues for research into the relationship between optimization hyperparameters and model performance.

Visual Insights#

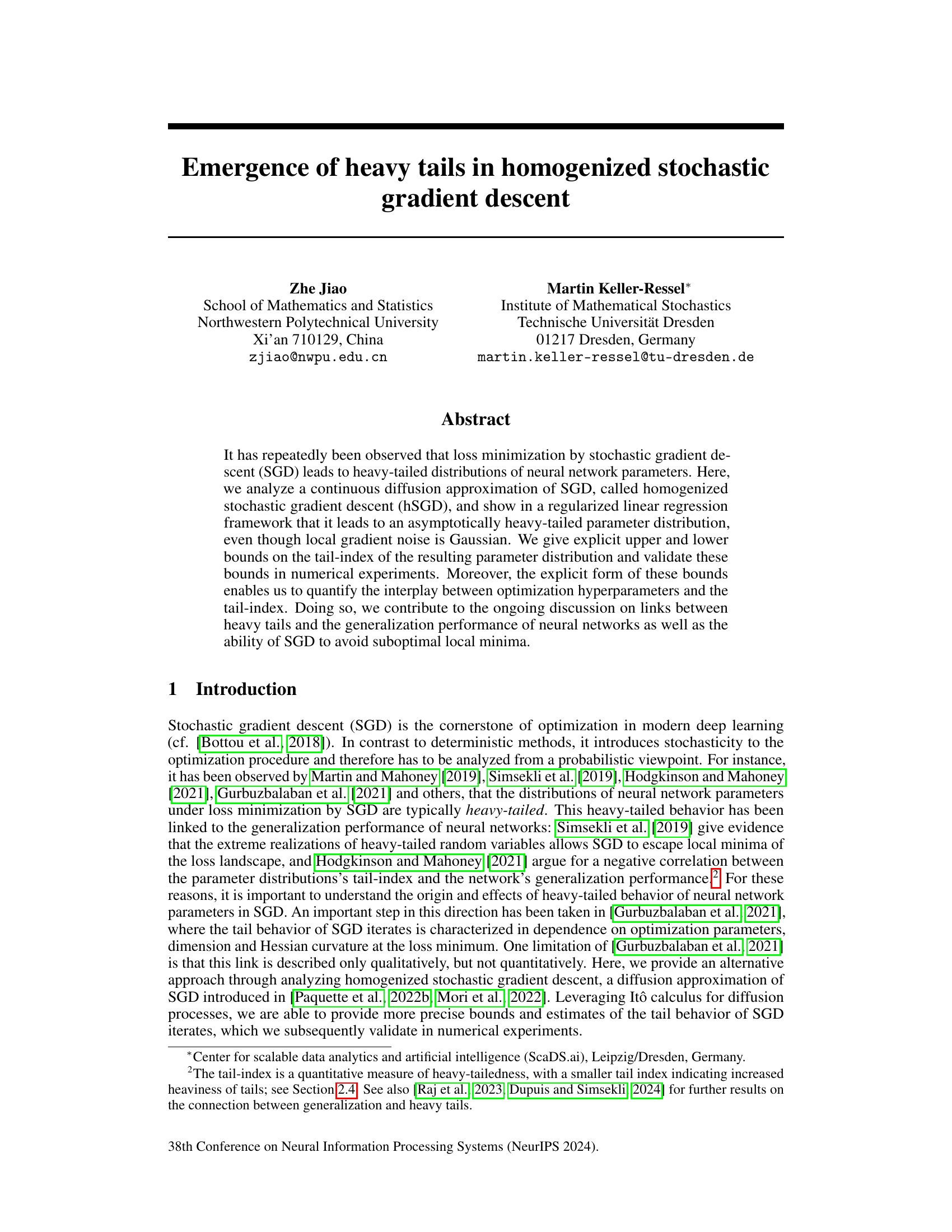

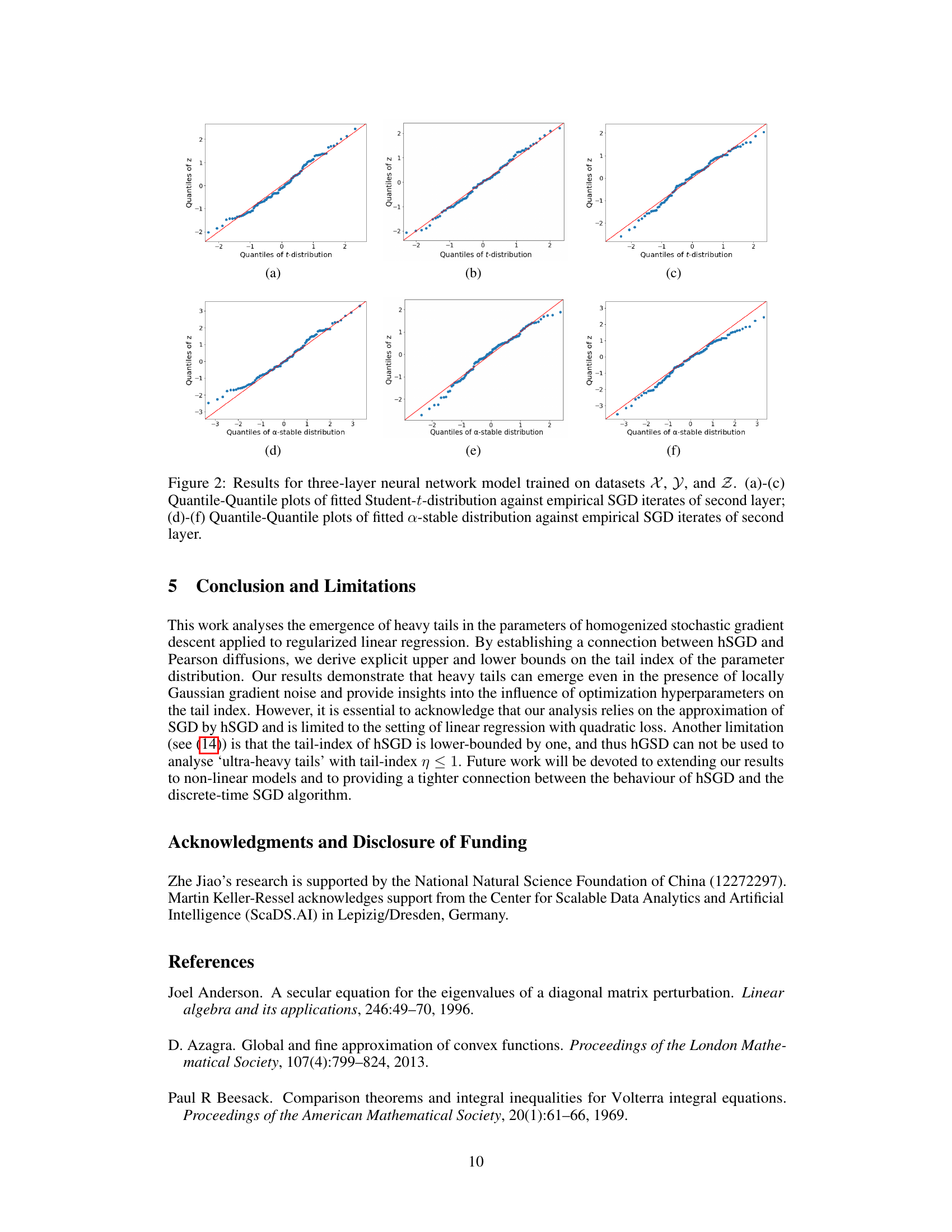

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the empirical distribution of SGD iterates with theoretical distributions (Student’s t and alpha-stable). QQ plots (a-f) show how well the empirical data fits the theoretical distributions. The plots (g-i) compare the complementary cumulative distribution function (ccdf) of the empirical data to the Student’s t-distribution, illustrating the accuracy of the theoretical upper and lower tail index bounds.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for linear regression/random feature model trained on datasets X, Y, and Z. (a)-(c) Quantile-Quantile plots of fitted Student-t-distribution against empirical SGD iterates; (d)-(f) Quantile-Quantile plots of fitted a-stable distribution against empirical SGD iterates; (g)-(i) Comparison between ccdf of empirical data and Student-t-distribution parameterized by upper tail-index bound η* and lower bound η*.

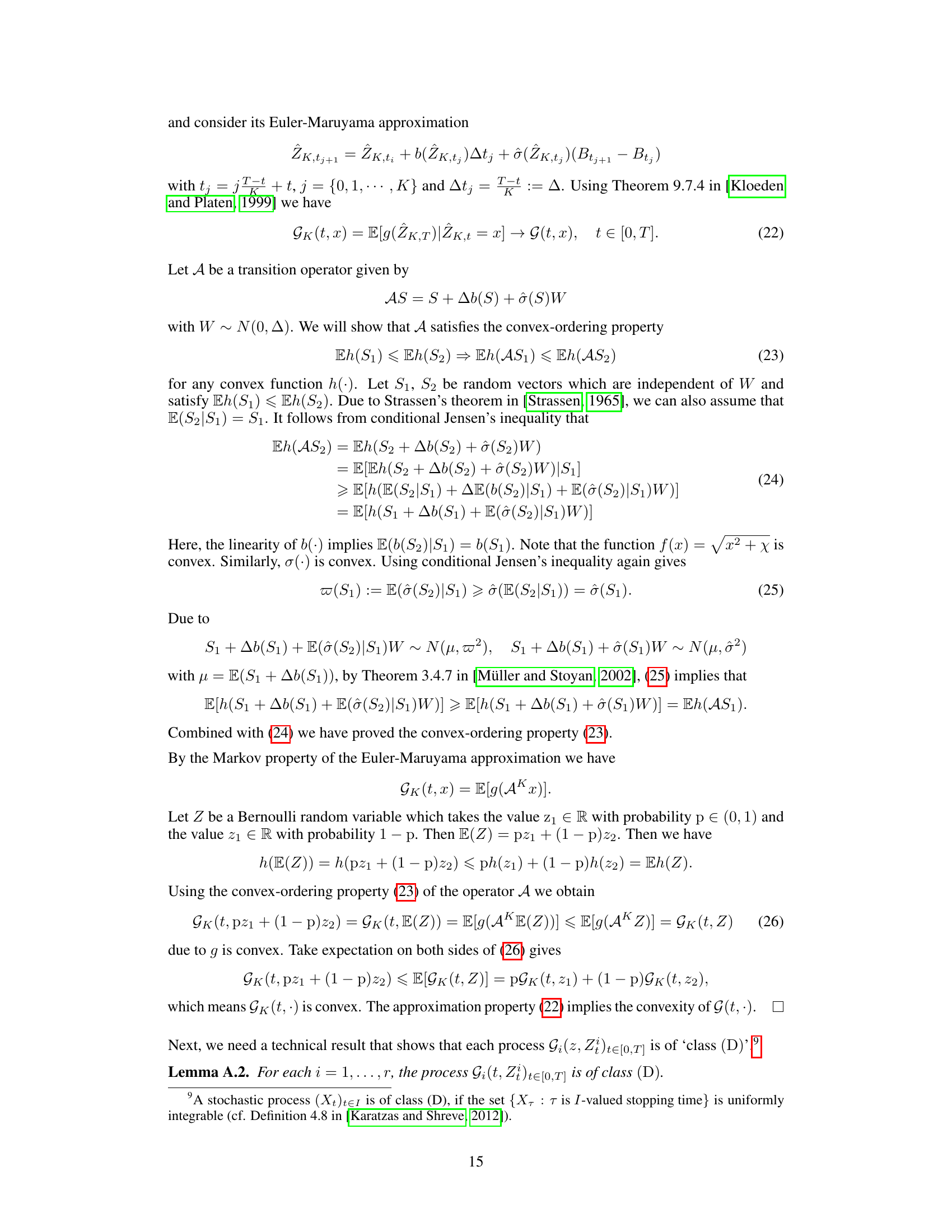

🔼 This table compares three different continuous-time models of stochastic gradient descent (SGD): Gaussian Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU), α-stable OU, and homogenized SGD. The comparison is based on the type of local gradient noise (Gaussian additive, non-Gaussian additive, and Gaussian additive/multiplicative, respectively), the resulting global parameter distribution (Gaussian, non-Gaussian α-stable, and non-Gaussian with a Student-t distribution as a proxy), and the tail index of the parameter distribution (+∞, (0,2), and (1, ∞), respectively). The table highlights the different characteristics of each model and their implications for understanding the heavy-tailed behavior observed in SGD.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of continuous-time models of SGD

In-depth insights#

Heavy-Tailed SGD#

The concept of “Heavy-Tailed SGD” refers to the observation that the parameters of neural networks trained using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) often exhibit heavy-tailed distributions. This contrasts with the typical assumption of Gaussian noise in many optimization analyses. The paper investigates this phenomenon by using a continuous diffusion approximation of SGD, demonstrating that even with Gaussian local gradient noise, heavy tails emerge asymptotically under certain conditions. The analysis provides explicit upper and lower bounds on the tail index, a key characteristic of heavy-tailed distributions. These bounds quantify the relationship between optimization hyperparameters and the heaviness of the tails, offering valuable insights into the behavior of SGD. The results suggest that heavy tails are linked to SGD’s ability to escape poor local minima, highlighting a potentially beneficial role for this characteristic in achieving good generalization performance. Furthermore, the study validates these findings via numerical experiments, comparing the analytical results to empirical data and demonstrating a good fit to a Student-t distribution, contrasting with prior hypotheses of alpha-stable distributions.

hSGD Analysis#

An ‘hSGD Analysis’ section would delve into the homogenized stochastic gradient descent method’s mathematical properties and its use in approximating the behavior of standard SGD. It would likely cover derivations of hSGD’s dynamics, perhaps starting from the stochastic differential equation (SDE) framework. A key aspect would be the analysis of the heavy-tailed parameter distributions emerging from hSGD, investigating how these tails arise from the interaction of the gradient noise and loss landscape. The analysis might provide quantitative bounds on the tail index as a measure of heavy-tailedness, relating these bounds to the algorithm’s hyperparameters and data characteristics. Furthermore, it could examine the asymptotic behavior of hSGD, determining its convergence properties and the rate at which it approaches a stationary distribution. Finally, the analysis would discuss the implications of hSGD’s heavy-tailedness for practical SGD applications, such as its impact on generalization performance and its ability to escape poor local minima.

Tail Index Bounds#

The concept of “Tail Index Bounds” in the context of analyzing heavy-tailed distributions arising from stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is crucial. These bounds provide a quantitative measure of the heaviness of the tails, offering valuable insights into the behavior of neural network parameters during training. The lower and upper bounds define a range within which the actual tail index must fall, thus providing a degree of certainty about the nature of the heavy-tailedness. Tight bounds are especially valuable as they accurately reflect the distribution’s characteristics, improving the understanding of SGD’s behavior and its impact on generalization performance. The explicit forms of these bounds allow us to investigate how hyperparameters, like learning rates and regularization, influence the tail index, thereby contributing to the ongoing discussion on optimization strategies and their effect on model properties.

Student-t fits SGD#

The hypothesis that Student’s t-distribution accurately models the parameter distribution resulting from stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is a significant finding. This contrasts with prior assumptions favoring Gaussian or α-stable distributions. The observed fit suggests heavy-tailed behavior in SGD, which aligns with empirical observations in deep learning. This improved fit has implications for understanding SGD’s ability to escape poor local minima and its generalization performance. The Student’s t-distribution, with its explicit tail index, allows for quantitative analysis of heavy-tailedness, providing a more nuanced understanding than previous qualitative descriptions. This quantitative aspect facilitates exploration of the impact of hyperparameters (learning rate, regularization) on the tail behavior, paving the way for more targeted optimization strategies. The strong empirical validation using various datasets enhances the significance of the Student-t model. However, further research is warranted to explore the limitations and generalizability of this finding to broader network architectures and loss functions beyond those considered in the paper.

Future work#

The paper’s “Future Work” section would ideally address several key limitations. Extending the analysis beyond linear regression to encompass more complex neural network architectures is crucial. The reliance on the homogenized SGD (hSGD) approximation should be explored more rigorously, perhaps by comparing theoretical predictions from hSGD to empirical results from standard SGD across various architectures and datasets. This would provide valuable insights into the accuracy and limitations of the hSGD model. Furthermore, investigating the relationship between heavy-tailed behavior and generalization performance in greater depth, moving beyond correlation to causality or mechanism, is vital. Lastly, examining whether similar heavy-tailed behavior emerges in other optimization algorithms besides SGD and exploring how this relates to their generalization capabilities would provide a broader and potentially more impactful understanding.

More visual insights#

More on tables

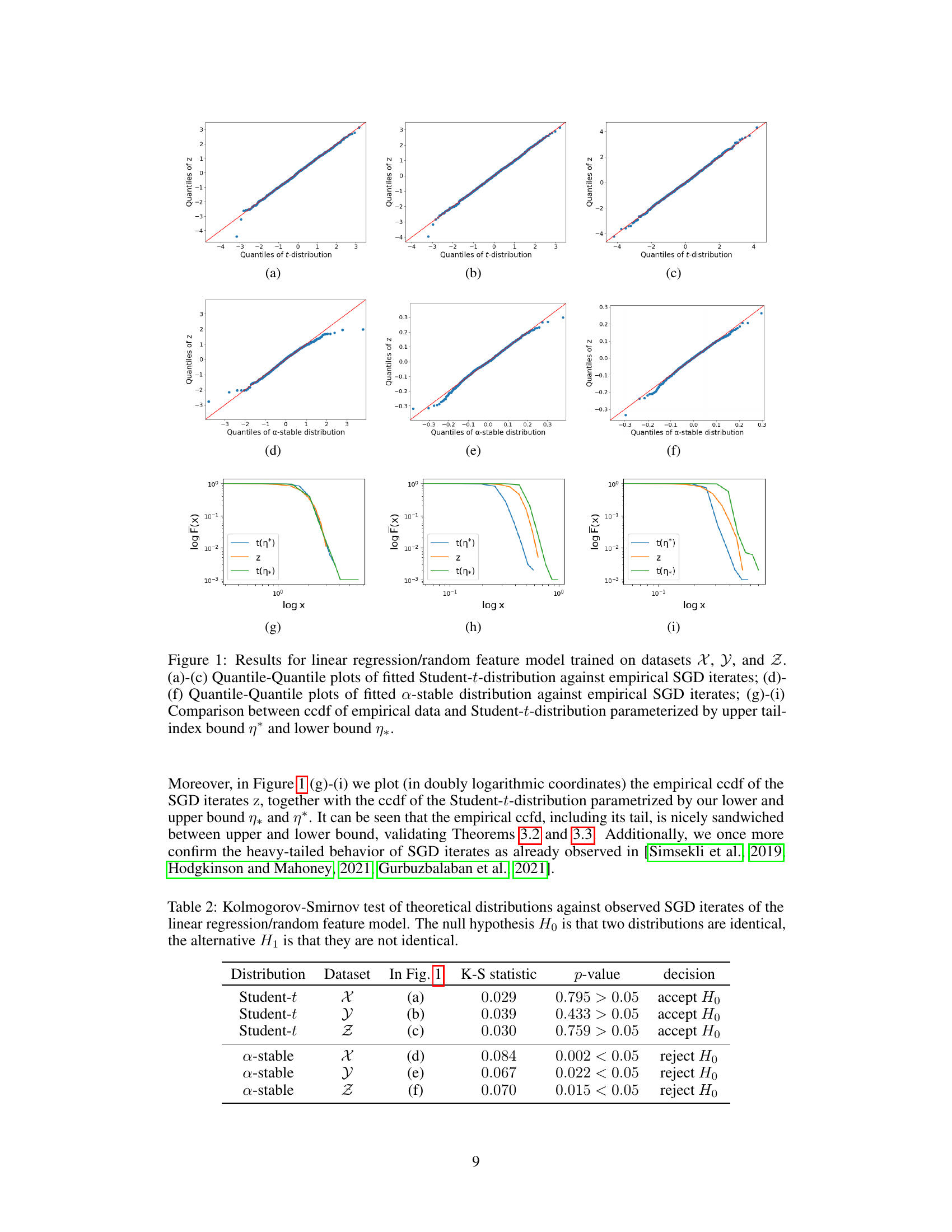

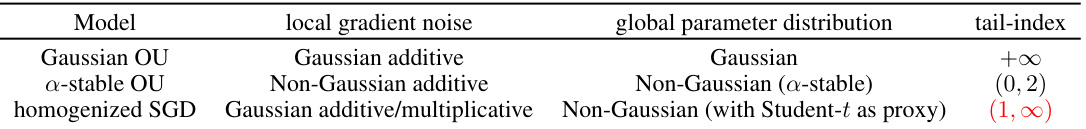

🔼 This table presents the results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests comparing the fit of Student-t and α-stable distributions to empirical data from SGD iterations in a linear regression model with synthetic and real-world datasets. The p-values indicate whether the null hypothesis (that the distributions are the same) can be rejected at a significance level of 0.05.

read the caption

Table 2: Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of theoretical distributions against observed SGD iterates of the linear regression/random feature model. The null hypothesis Ho is that two distributions are identical, the alternative H₁ is that they are not identical.

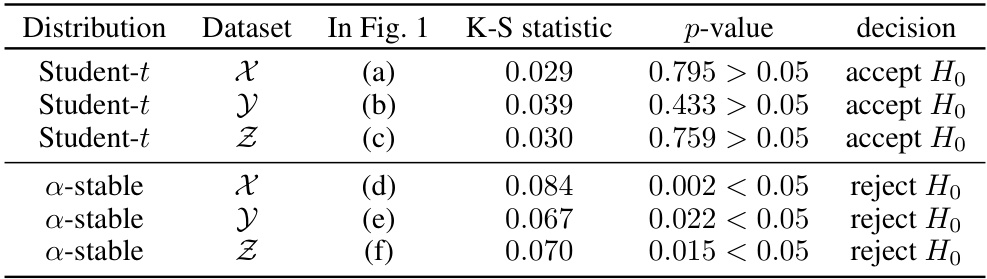

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for the experiments in Figure 1. It shows the data used (X, Y, Z), the dimension (d), the number of iterations (K), the learning rate (γ), the threshold for the learning rate (γ̃), the regularization parameter (δ), the batch size (B), the maximum eigenvalue (λ₁), and the upper (η*) and lower (η) bounds of the asymptotic tail index. These parameters were used to generate the results shown in Figure 1, illustrating the heavy-tailed behavior of SGD in linear regression and random feature models.

read the caption

Table 3: Parameters used for Figure 1

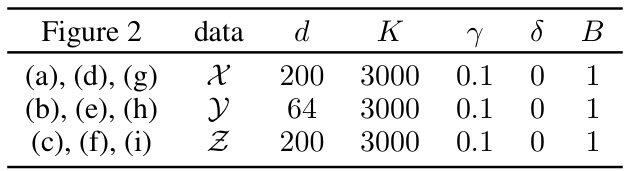

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameters used in the experiments for Figure 2 of the paper. The hyperparameters include the dimension of the data (d), the number of iterations in the SGD algorithm (K), the learning rate (γ), the regularization parameter (δ), and the batch size (B). Three different datasets (X, Y, Z) were used, and the table shows the parameter settings for each dataset.

read the caption

Table 4: Parameters used for Figure 2

Full paper#