TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are powerful but their training data is often opaque, hindering the assessment of their biases and vulnerabilities. This paper tackles this issue by focusing on a previously underutilized source of information: the byte-pair encoding (BPE) tokenizer. These tokenizers are used by most LLMs to break down text into smaller units; the researchers found that the order in which the tokenizer merges these units reveals patterns related to data frequencies.

The authors developed a method that uses these patterns along with some sample data to estimate the proportions of different types of data within the LLM’s training set. They tested their method on several publicly available tokenizers, uncovering new information such as the significant multilingual composition of some models’ training data and the unexpected prevalence of code in the training of others. Their approach provides a new way to analyze and understand the hidden properties of LLMs’ training data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel method to infer the composition of language models’ training data which is typically kept secret by developers. This opens avenues for research into data bias, model vulnerabilities, and the overall design choices in creating these models. Understanding training data is key for evaluating and improving the reliability and safety of language models, a growing concern in the AI research community.

Visual Insights#

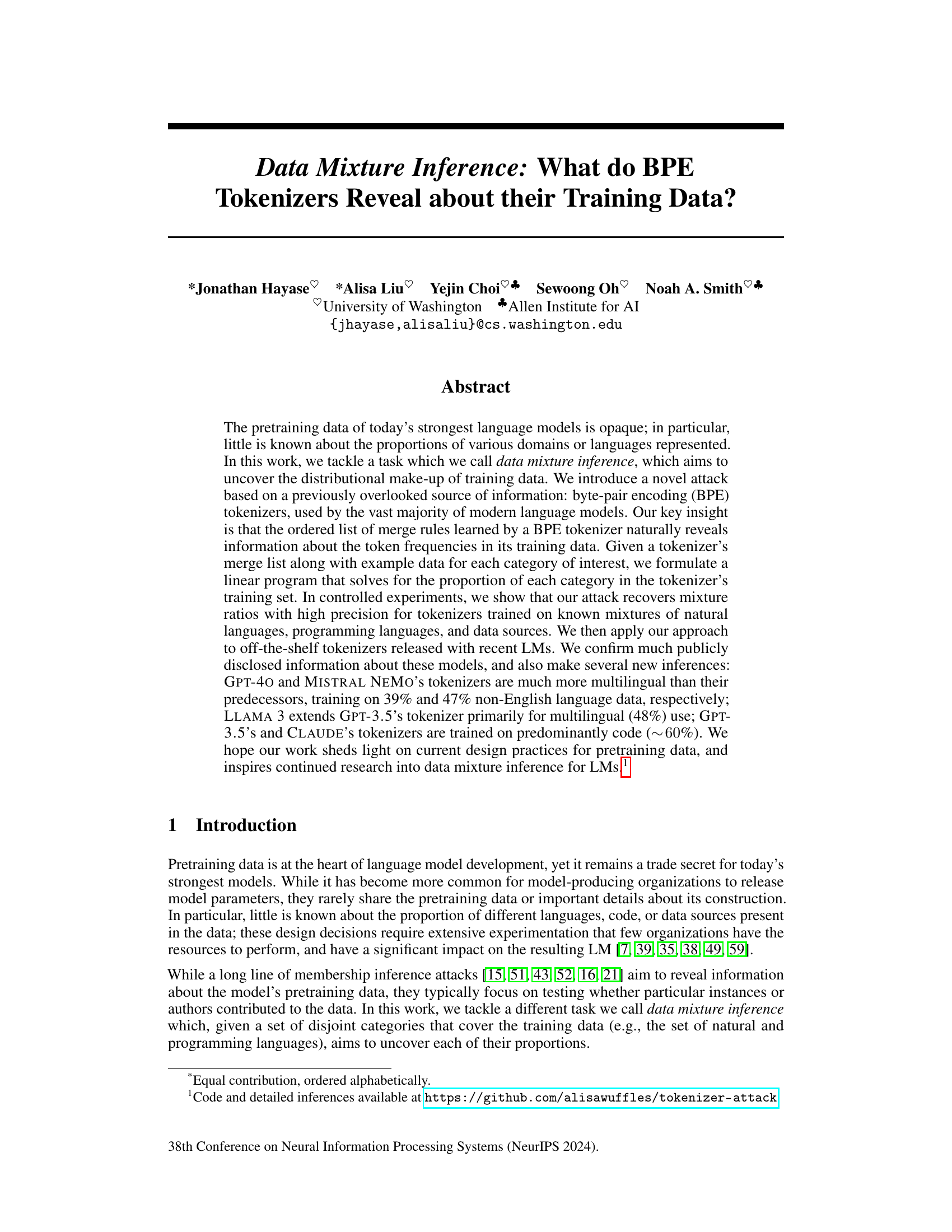

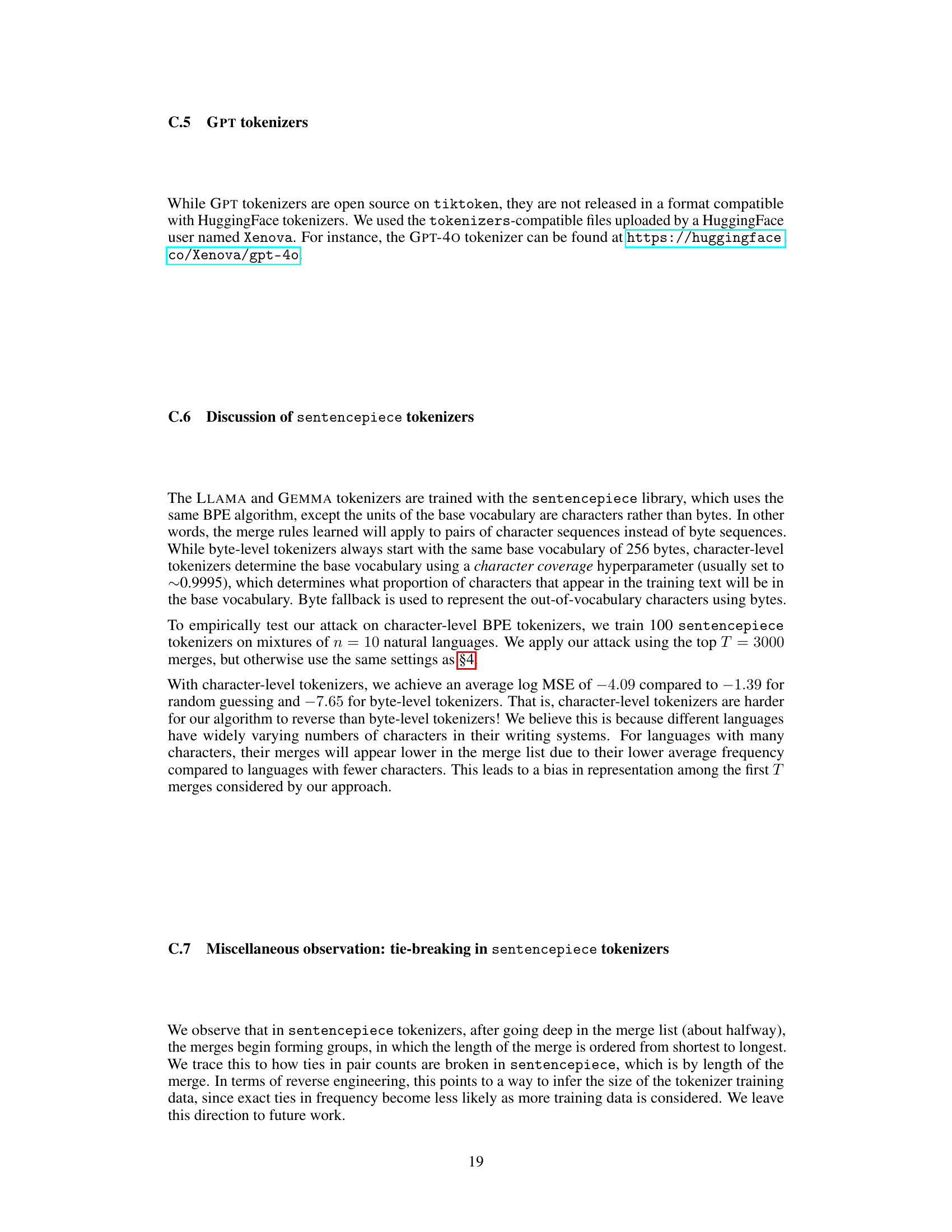

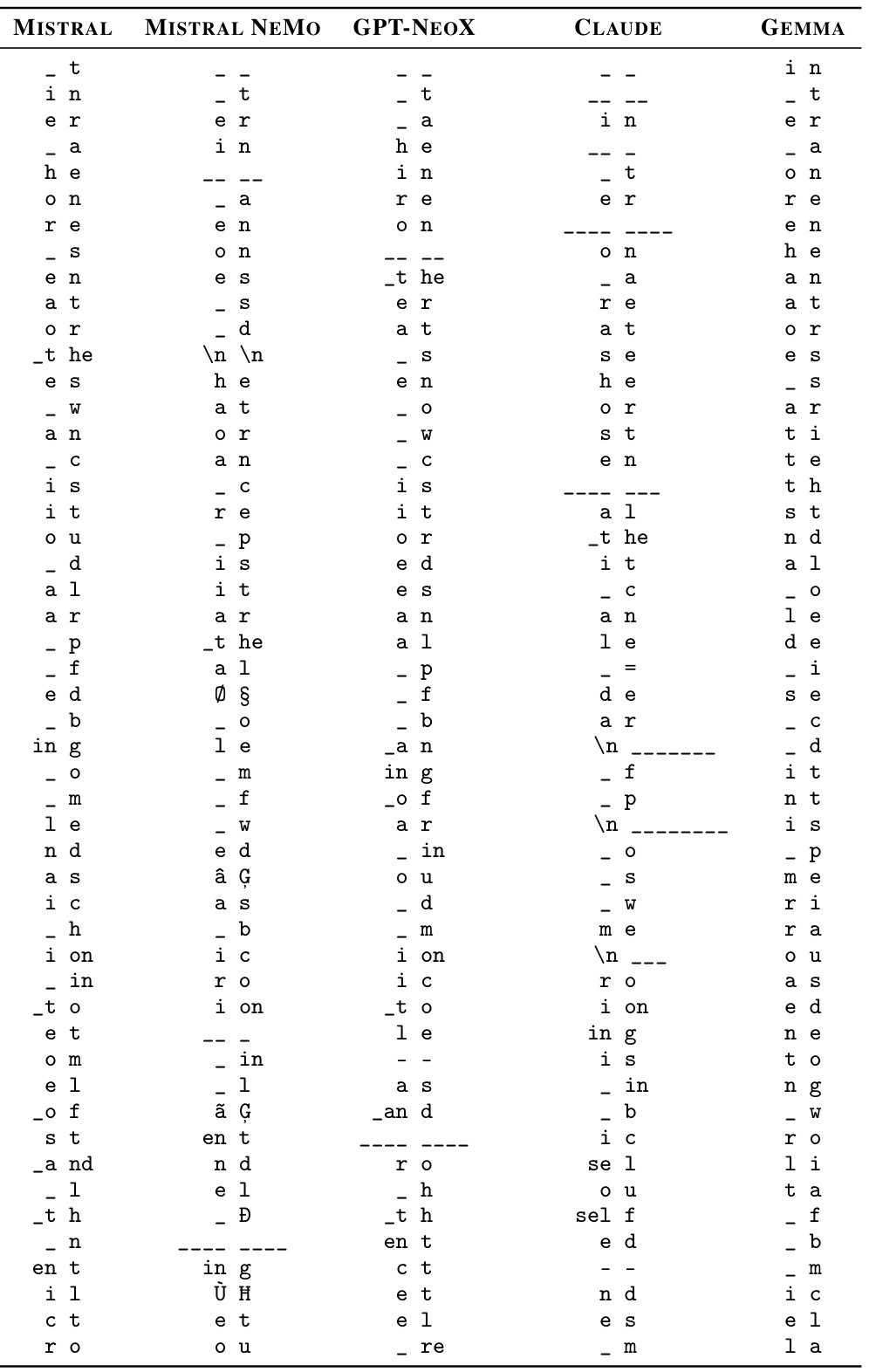

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper: data mixture inference using byte-pair encoding (BPE) tokenizers. Two BPE tokenizers are trained on different ratios of English and Python code. The figure shows how the order of merge rules learned by the BPE algorithm directly reflects the proportion of each language in the training data. The authors aim to reverse this process – given a tokenizer’s merge list, infer the original data proportions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our problem statement on a simple example where two tokenizers are trained on different mixtures of English and Python data. During training, the BPE algorithm iteratively finds the pair of tokens with the highest frequency in the training data, adds it to the merge list, then applies it to the dataset before finding the next highest-frequency pair. To encode text at inference time, the learned merge rules are applied in order. The resulting order of merge rules is extremely sensitive to the proportion of different data categories present. Our goal is to solve for these proportions, a task which we call data mixture inference.

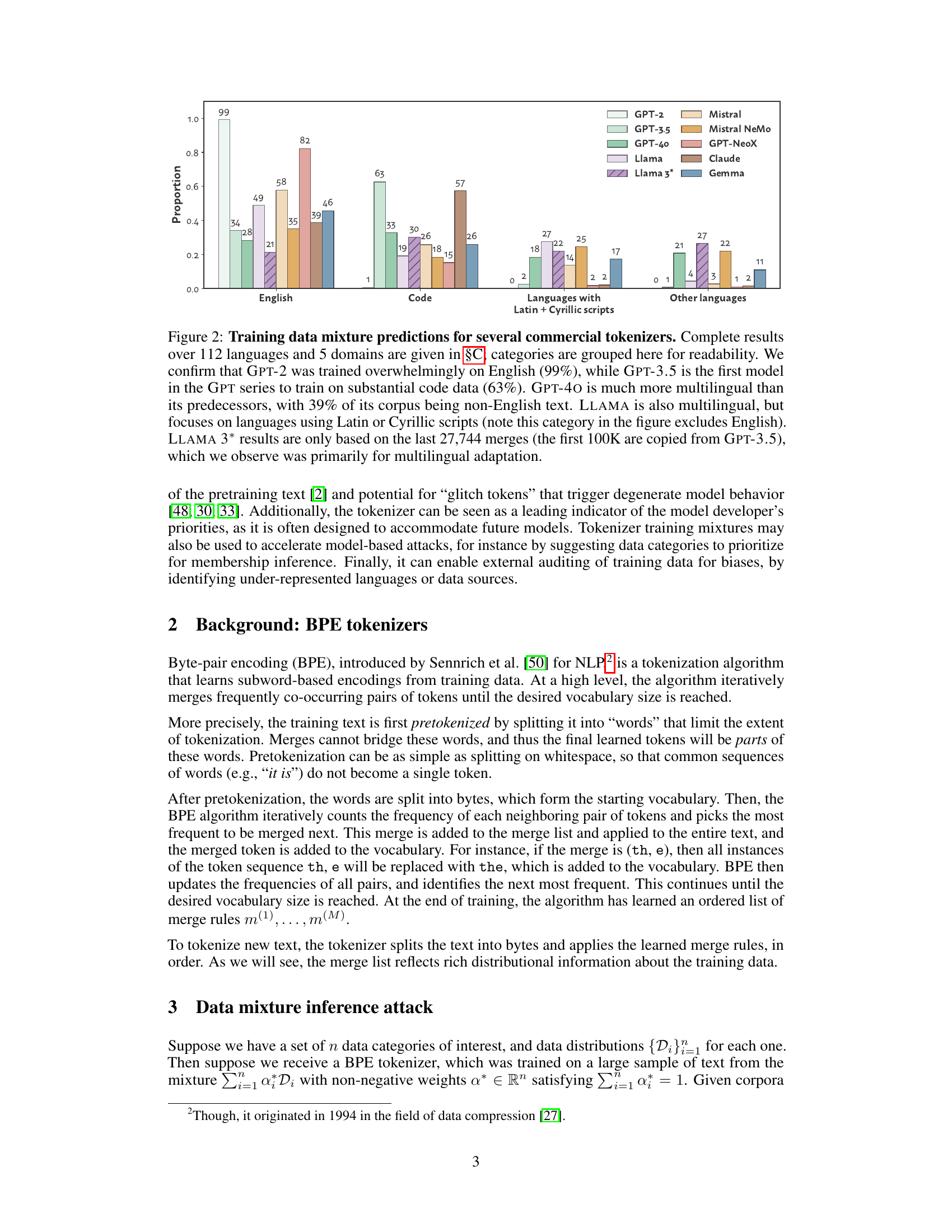

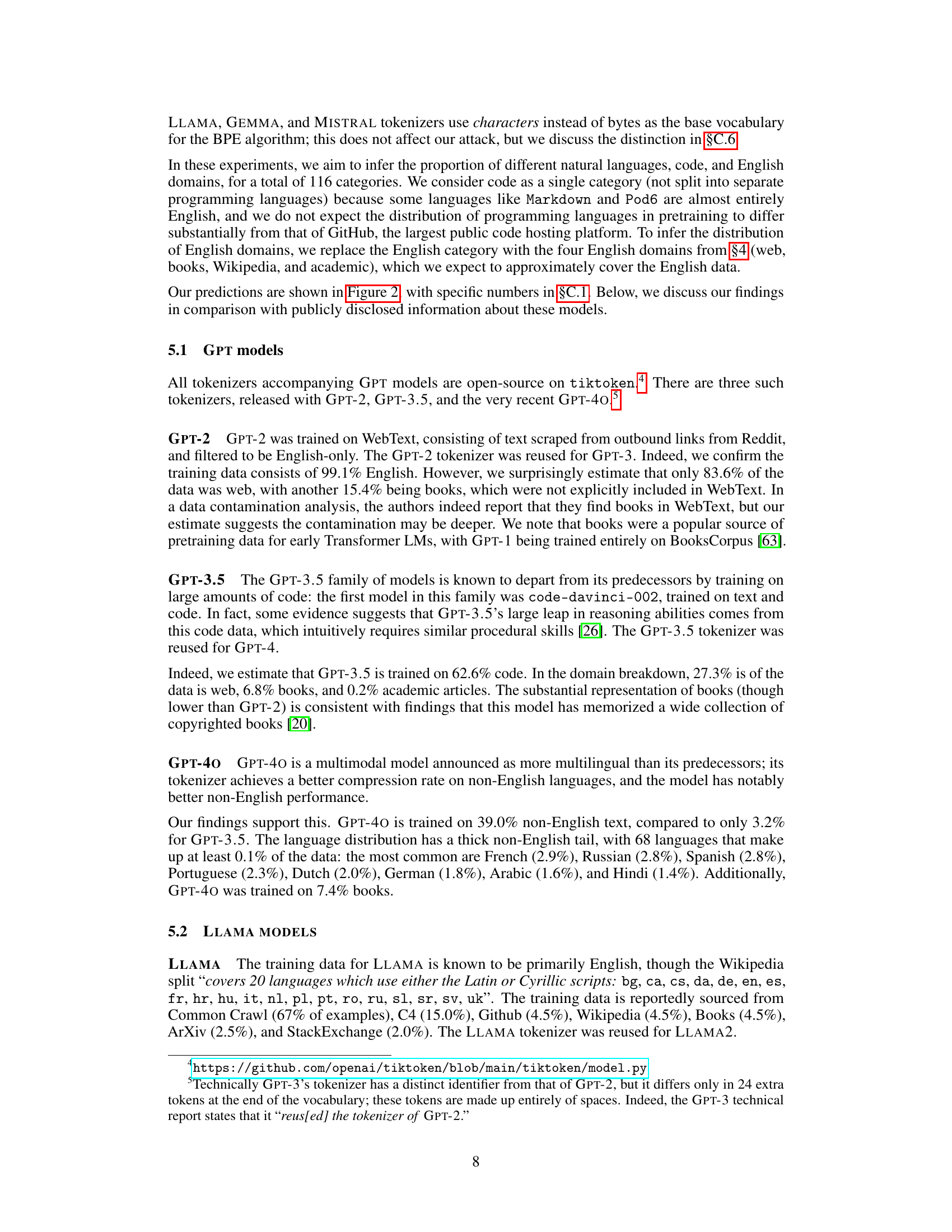

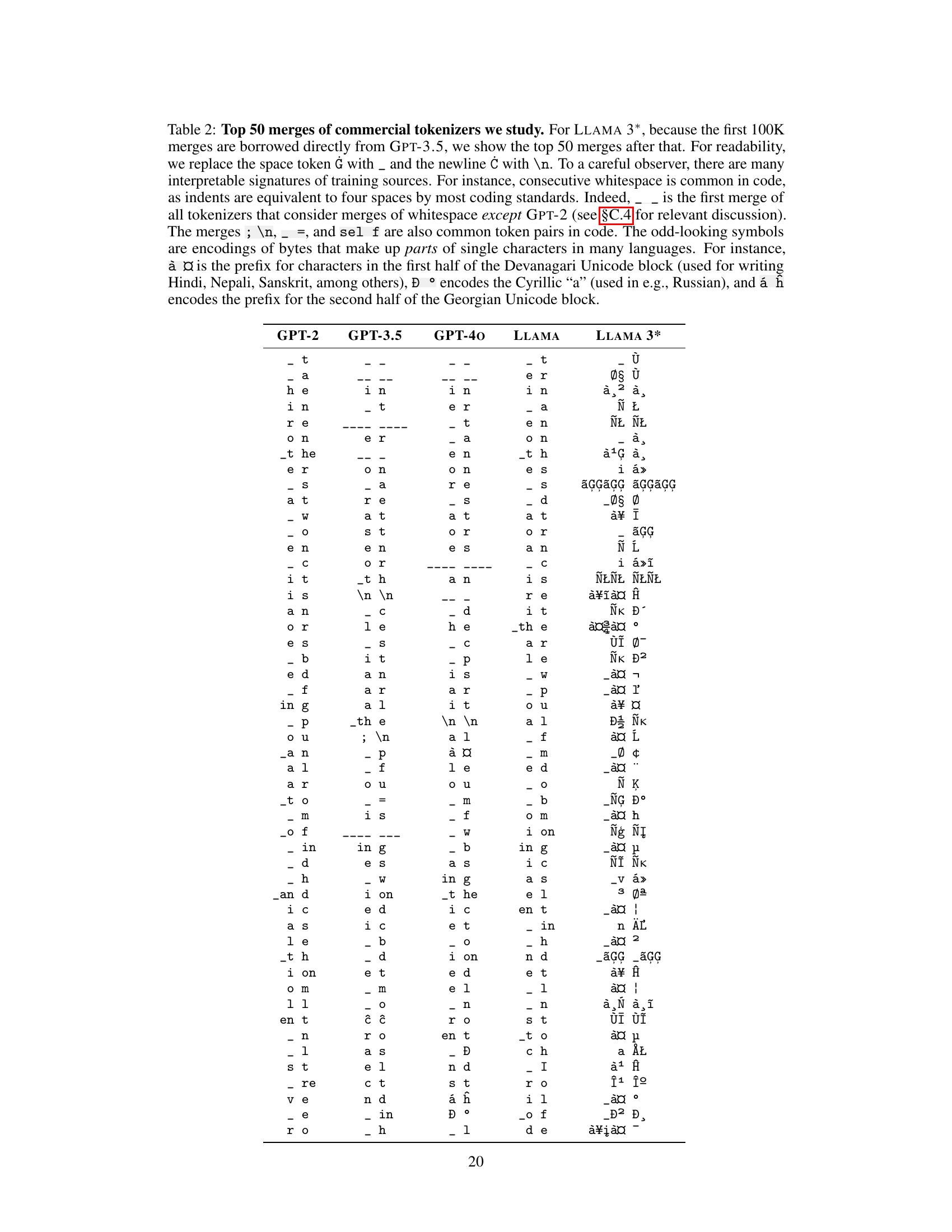

🔼 This table presents the results of controlled experiments evaluating the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack. The attack was tested on various mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains, with different numbers of categories (n). The results show the mean and standard deviation of the log10(MSE) for each setting, comparing the proposed attack to random guessing and two other baselines (TEE and TC). Lower log10(MSE) values indicate higher accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

In-depth insights#

BPE Tokenizer Attacks#

The concept of “BPE Tokenizer Attacks” revolves around exploiting the inherent properties of Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizers to infer the composition of training data used for large language models (LLMs). BPE tokenizers, a crucial component in many LLMs, learn merge rules based on the frequency of token pairs in the training data. This ordered list of merge rules serves as a hidden signature reflecting the data’s statistical properties. An attack leverages this by formulating a linear program that estimates the proportions of different data categories (languages, code, domains, etc.) present in the training set, given the tokenizer’s merge rules and sample data representing each category. The attack’s effectiveness lies in its ability to recover mixture ratios with remarkable precision, even for tokenizers trained on diverse and complex mixtures of data sources. Therefore, analysis of these merge rules presents a novel and effective approach to gain insight into the often opaque training data of LLMs, which could have significant implications for understanding model behavior, assessing biases, and evaluating the representativeness of the training data itself.

Data Mixture Inference#

The concept of ‘Data Mixture Inference’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on deconstructing the composition of training datasets. It’s a significant area of research because the exact makeup of LLM training data is often proprietary and opaque. This lack of transparency hinders efforts to understand model behavior, identify biases, and assess potential risks. Methods for data mixture inference aim to estimate the proportions of various data types (e.g., languages, code, domains) present in the training data by analyzing readily available artifacts, such as the model’s tokenizer. Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizers, commonly used in LLMs, offer a unique avenue for this analysis because the order in which they merge byte pairs reflects the frequency of those pairs in the training data. By carefully analyzing this ‘merge list’ and comparing it to known data distributions, researchers can infer the mixture ratios within the training data with surprisingly high accuracy. This is a powerful technique for shedding light on the often hidden ingredients driving LLM performance and characteristics.

Linear Program Solver#

A linear program solver is a crucial component in the proposed data mixture inference attack. The core idea is to formulate the problem of estimating the proportions of different data categories in a tokenizer’s training set as a linear program. The constraints of this linear program are derived directly from the ordered list of merge rules produced by the byte-pair encoding (BPE) algorithm. Each merge rule represents the most frequent token pair at a specific stage of the training process; this information is used to create inequalities that constrain the possible proportions of data categories. The objective function of the linear program is to minimize the total constraint violations, effectively finding the mixture proportions that best match the observed merge rule ordering. The choice of solver will depend on the scale of the problem; for large-scale tasks, specialized solvers with techniques like simultaneous delayed row/column generation might be necessary to manage computational costs and complexity effectively. The solution to the linear program yields estimates of the proportions of different data categories present in the original training data. This approach leverages the subtle yet informative nature of the merge rule ordering within the BPE tokenizer to infer properties of the data used for training, allowing for analysis of the data composition of language models.

Commercial Tokenizers#

The section on ‘Commercial Tokenizers’ presents a crucial empirical evaluation of the proposed data mixture inference attack. The authors apply their method to several widely-used commercial language model tokenizers, revealing insights into the composition of their training datasets that were previously unknown or only vaguely understood. This analysis goes beyond simply verifying known information; instead, it provides quantitative estimates of the proportions of different languages and data types (code, books, web data) present in the training data. The results confirm some existing intuitions (e.g., GPT-3.5’s reliance on code) but also offer surprising new findings (e.g., the unexpected multilingualism of GPT-40 and MISTRAL NEMO). This real-world application of their method effectively demonstrates its power and utility in understanding the opaque nature of LLM training data, raising important questions about the design choices made by model developers and the implications for future model transparency and safety.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this data mixture inference work could focus on several key areas. Improving the robustness of the attack against various data distribution shifts and unaccounted-for data categories is crucial. This could involve developing more sophisticated linear programming techniques or incorporating additional information sources beyond BPE tokenizer merge rules. Exploring alternative tokenizer architectures and investigating whether similar inference attacks can be mounted against them would broaden the applicability and implications of this research. Extending the attack to encompass other model properties such as model weights or activations would provide a more holistic view of training data influence. Finally, developing effective defenses against these types of attacks is vital for responsible language model development and deployment. This could involve designing new tokenization methods or incorporating data obfuscation techniques into the training process. Ultimately, the goal should be to encourage a balanced approach that allows for insights into training data composition while mitigating potential vulnerabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

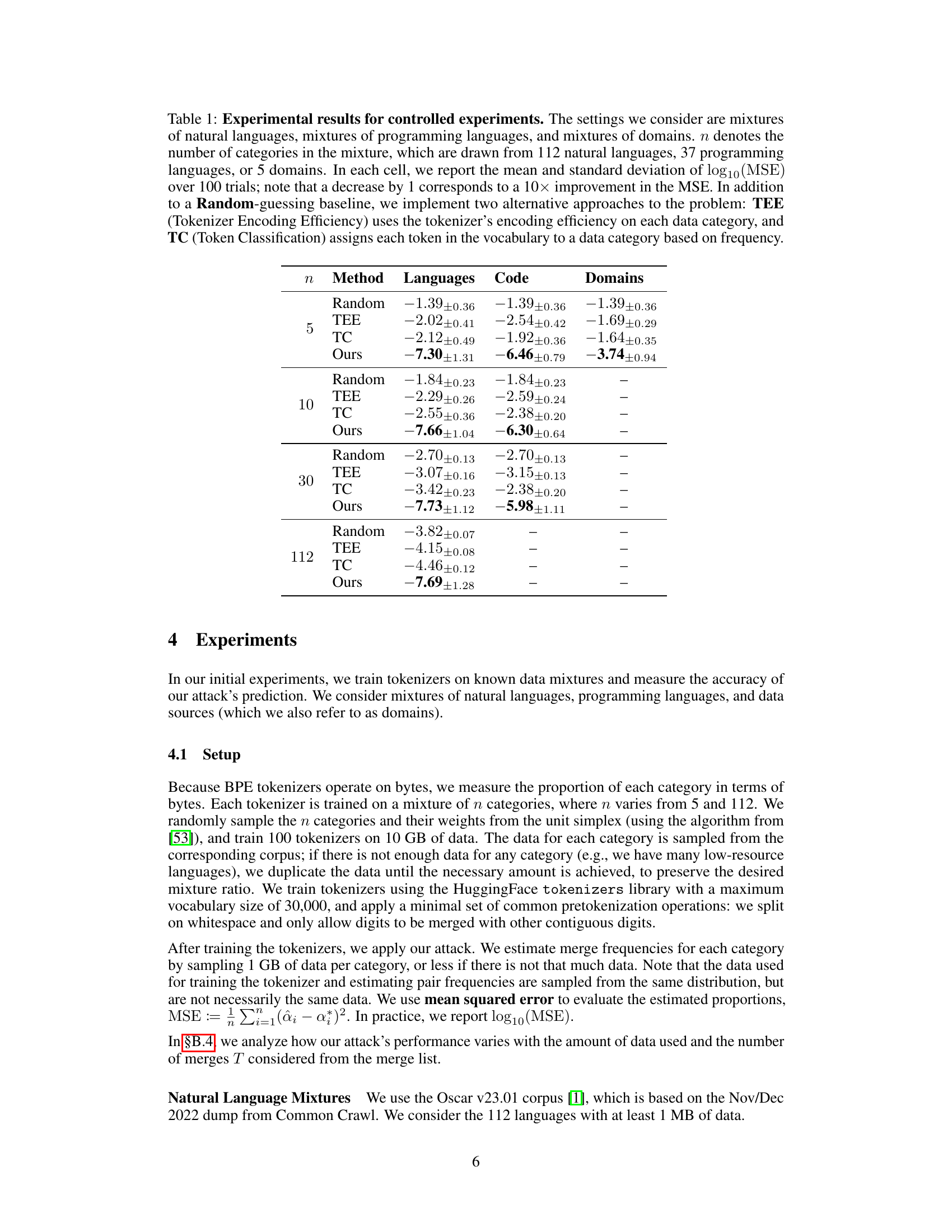

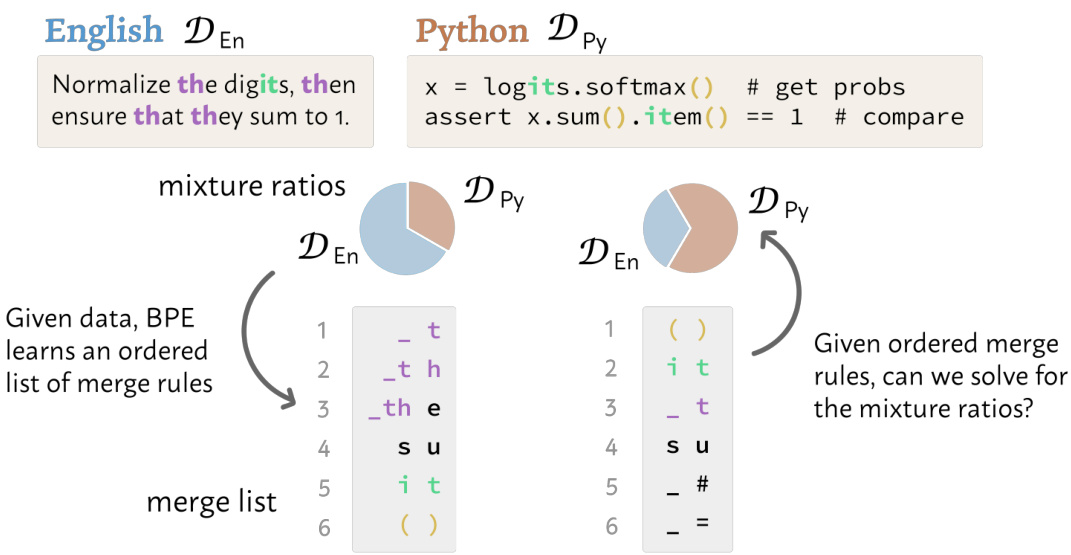

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the data mixture inference attack on several commercial language models’ tokenizers. It displays the proportion of English, code, Latin/Cyrillic languages, and other languages in the training data for each tokenizer. Key findings highlighted are the overwhelmingly English training data for GPT-2, the significant code data used in GPT-3.5, the increased multilingualism in GPT-40 and LLAMA 3, and the specific language focus of LLAMA (Latin/Cyrillic scripts).

read the caption

Figure 2: Training data mixture predictions for several commercial tokenizers. Complete results over 112 languages and 5 domains are given in §C; categories are grouped here for readability. We confirm that GPT-2 was trained overwhelmingly on English (99%), while GPT-3.5 is the first model in the GPT series to train on substantial code data (63%). GPT-40 is much more multilingual than its predecessors, with 39% of its corpus being non-English text. LLAMA is also multilingual, but focuses on languages using Latin or Cyrillic scripts (note this category in the figure excludes English). LLAMA 3* results are only based on the last 27,744 merges (the first 100K are copied from GPT-3.5), which we observe was primarily for multilingual adaptation.

🔼 This figure shows the training data mixture proportions predicted by the authors’ method for several commercially available large language models (LLMs). The models are categorized along the x-axis into English, Code, Languages with Latin or Cyrillic scripts, and Other Languages. The y-axis represents the proportion of the training data that fell into each category. The figure visually demonstrates the varying levels of multilingualism and code usage in the training data of different models. For example, it highlights GPT-2’s heavy reliance on English, GPT-3.5’s significant code usage, and GPT-40’s increased multilingualism compared to its predecessors. The figure also shows that Llama focuses on languages using Latin or Cyrillic scripts.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training data mixture predictions for several commercial tokenizers. Complete results over 112 languages and 5 domains are given in §C; categories are grouped here for readability. We confirm that GPT-2 was trained overwhelmingly on English (99%), while GPT-3.5 is the first model in the GPT series to train on substantial code data (63%). GPT-40 is much more multilingual than its predecessors, with 39% of its corpus being non-English text. LLAMA is also multilingual, but focuses on languages using Latin or Cyrillic scripts (note this category in the figure excludes English). LLAMA 3* results are only based on the last 27,744 merges (the first 100K are copied from GPT-3.5), which we observe was primarily for multilingual adaptation.

🔼 This figure illustrates how the proposed data mixture inference attack works. It shows a simplified example with two languages, English and Spanish. The BPE tokenizer learns merge rules based on the frequency of token pairs in the training data. The attack uses these ordered merge rules to create linear program constraints. Each constraint reflects the most frequent pair at each step. Solving the linear program estimates the proportion of each language in the original training data.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of our method on a simple example. We know that after applying in the first t – 1 merges to the training data, the tth merge must be the most common pair. More explicitly, this means that ai should give a vector in which the value corresponding to the true next merge is the maximum. Our attack collects these inequalities at every time step to construct the linear program.

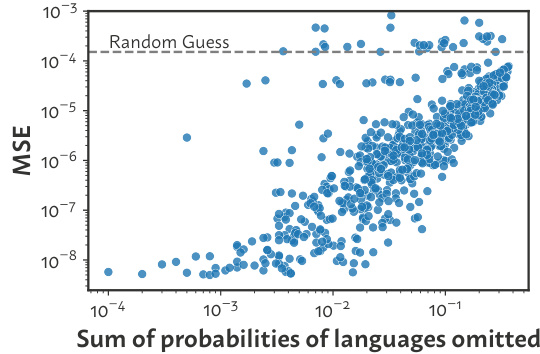

🔼 This figure shows the robustness of the data mixture inference attack when some languages are omitted from the training data. The x-axis represents the sum of probabilities of omitted languages, and the y-axis represents the mean squared error (MSE) of the prediction on the remaining languages. The plot demonstrates that even when a significant portion of the languages are unknown, the attack’s performance is still substantially better than random guessing. This highlights the robustness of the method to handle cases where not all data categories are explicitly accounted for in the analysis.

read the caption

Figure 4: Performance remains much better than random even with large amounts of unknown data.

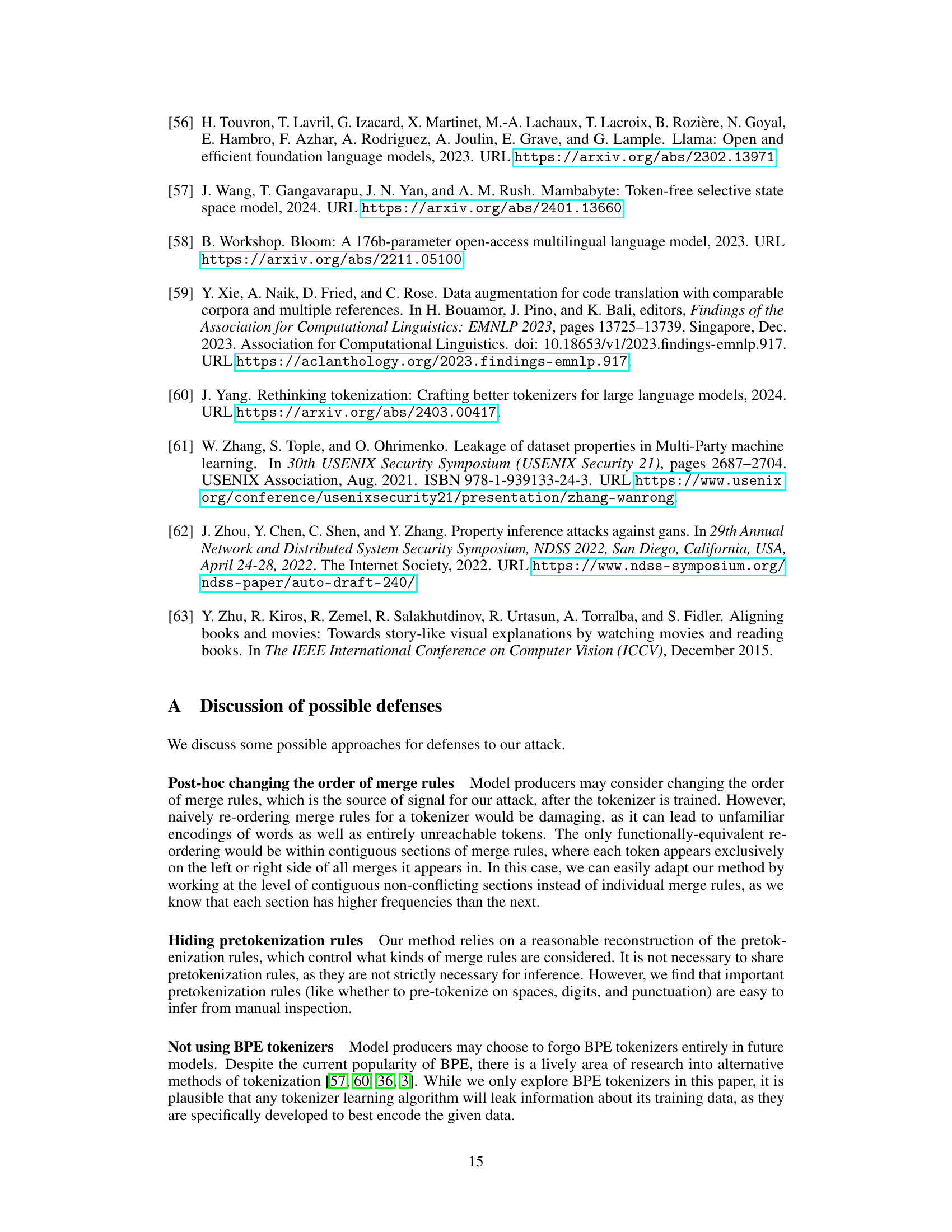

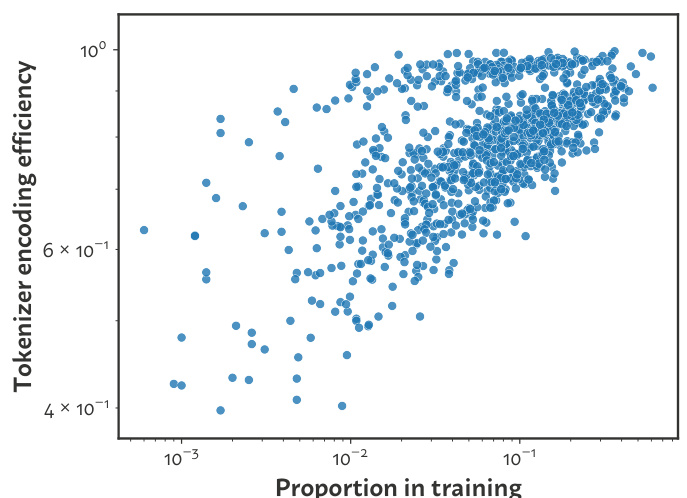

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the proportion of a language in the training data and the encoding efficiency of that language by the resulting tokenizer. The encoding efficiency is calculated as the ratio of bytes to tokens, normalized against a tokenizer trained solely on that language. While higher proportions generally correlate with greater efficiency, the relationship isn’t strong enough to accurately predict language proportions in the training data, unlike the approach presented in the paper. The figure highlights the superior accuracy of the proposed attack compared to a baseline approach that uses encoding efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 5: Relationship between a language's proportion in training and the resulting tokenizer's encoding efficiency on that language, shown for mixtures of n = 10 languages. The encoding efficiency is defined as the byte-to-token ratio of a given tokenizer on a given language, normalized by that of a tokenizer trained only on that language. While more training data leads to better encoding efficiency, the correlation is not strong enough to recover a prediction nearly as precise as our attack. A baseline based on this relationship achieves log10 MSE of -2.22, compared to our attack's -7.66.

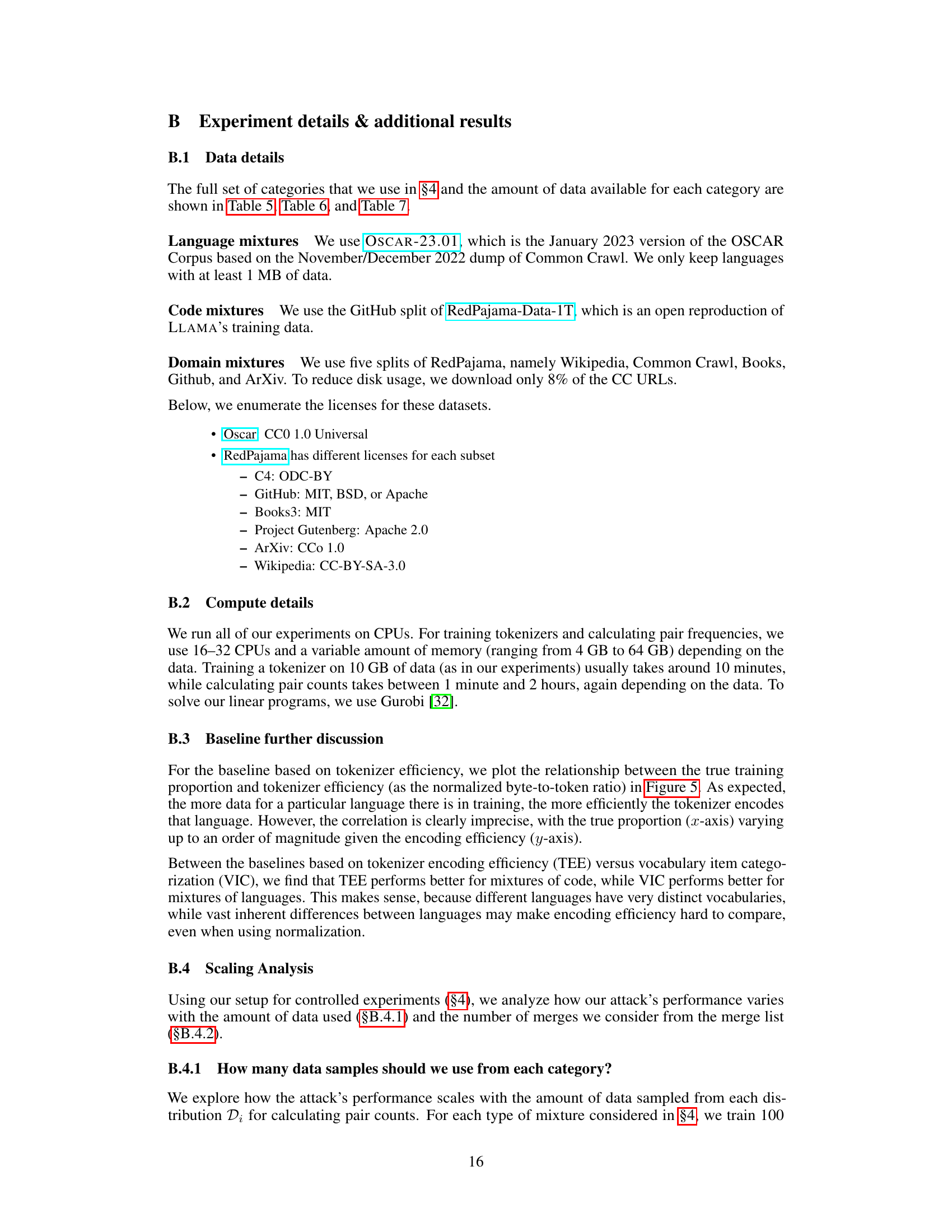

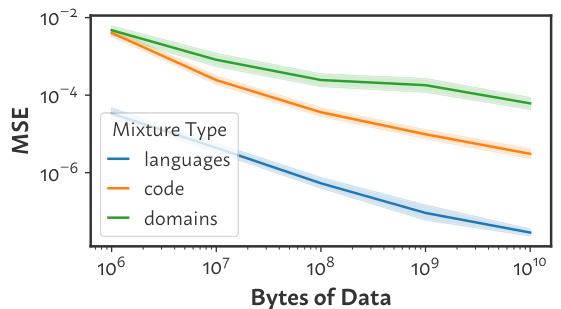

🔼 This figure shows how the accuracy of the data mixture inference attack changes with the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies. The experiment was conducted using mixtures of 5 categories. As expected, increasing the amount of data per category leads to significantly more precise inferences (lower MSE).

read the caption

Figure 6: Scaling the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies (§B.4.1), for mixtures of n = 5 categories. Sampling more data per category produces more precise inferences.

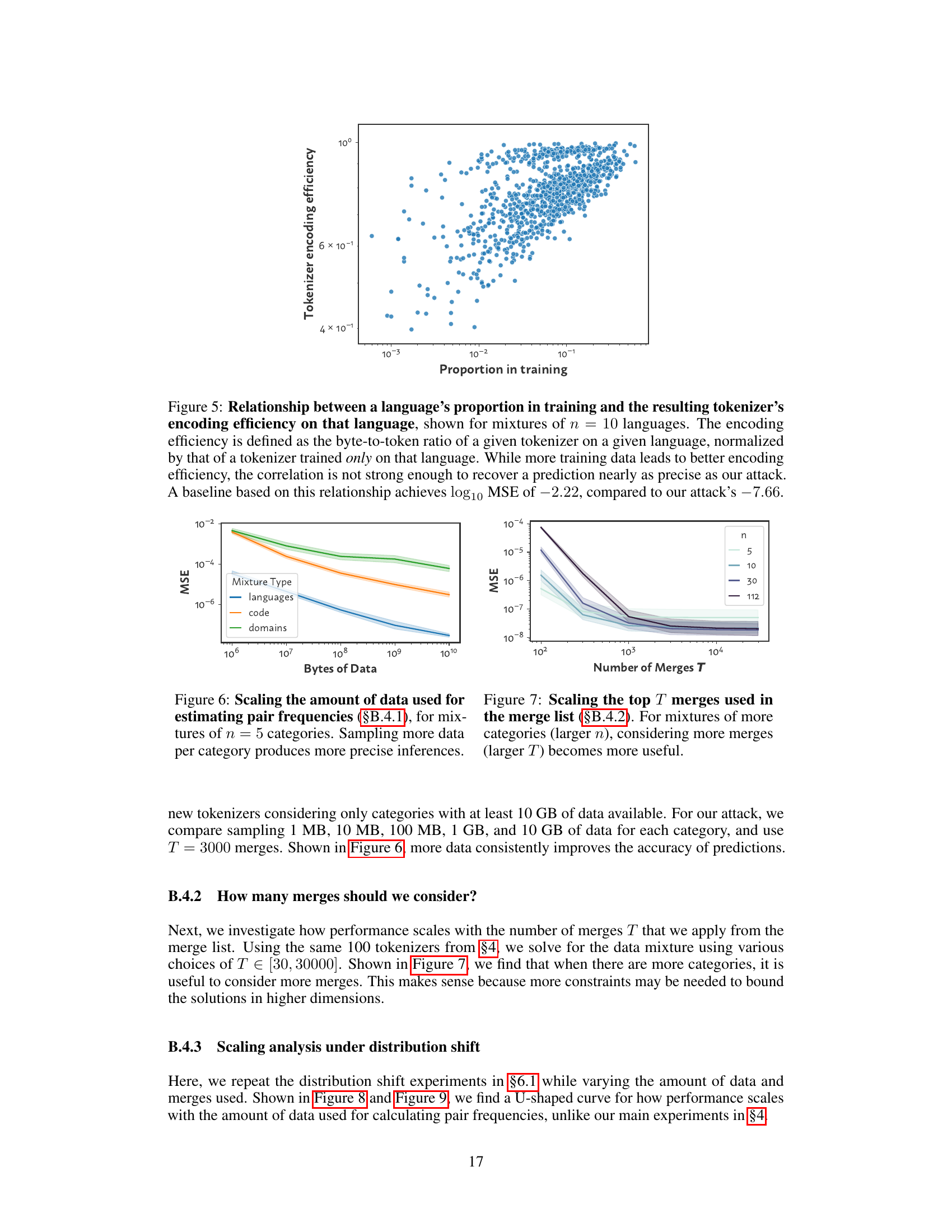

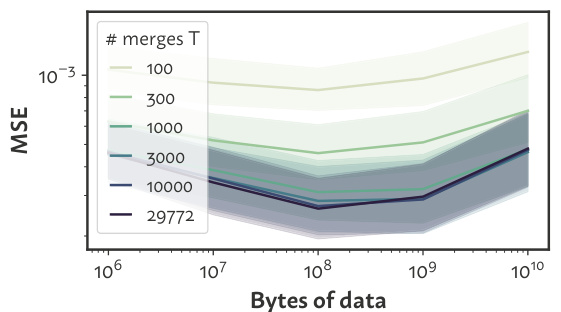

🔼 This figure shows how the accuracy of the data mixture inference attack changes depending on the number of merges (T) considered from the tokenizer’s merge list. The results are shown for different numbers of categories (n) in the mixture. As expected, increasing the number of merges considered improves the accuracy of the attack, particularly when there are more categories in the mixture.

read the caption

Figure 7: Scaling the top T merges used in the merge list (§B.4.2). For mixtures of more categories (larger n), considering more merges (larger T) becomes more useful.

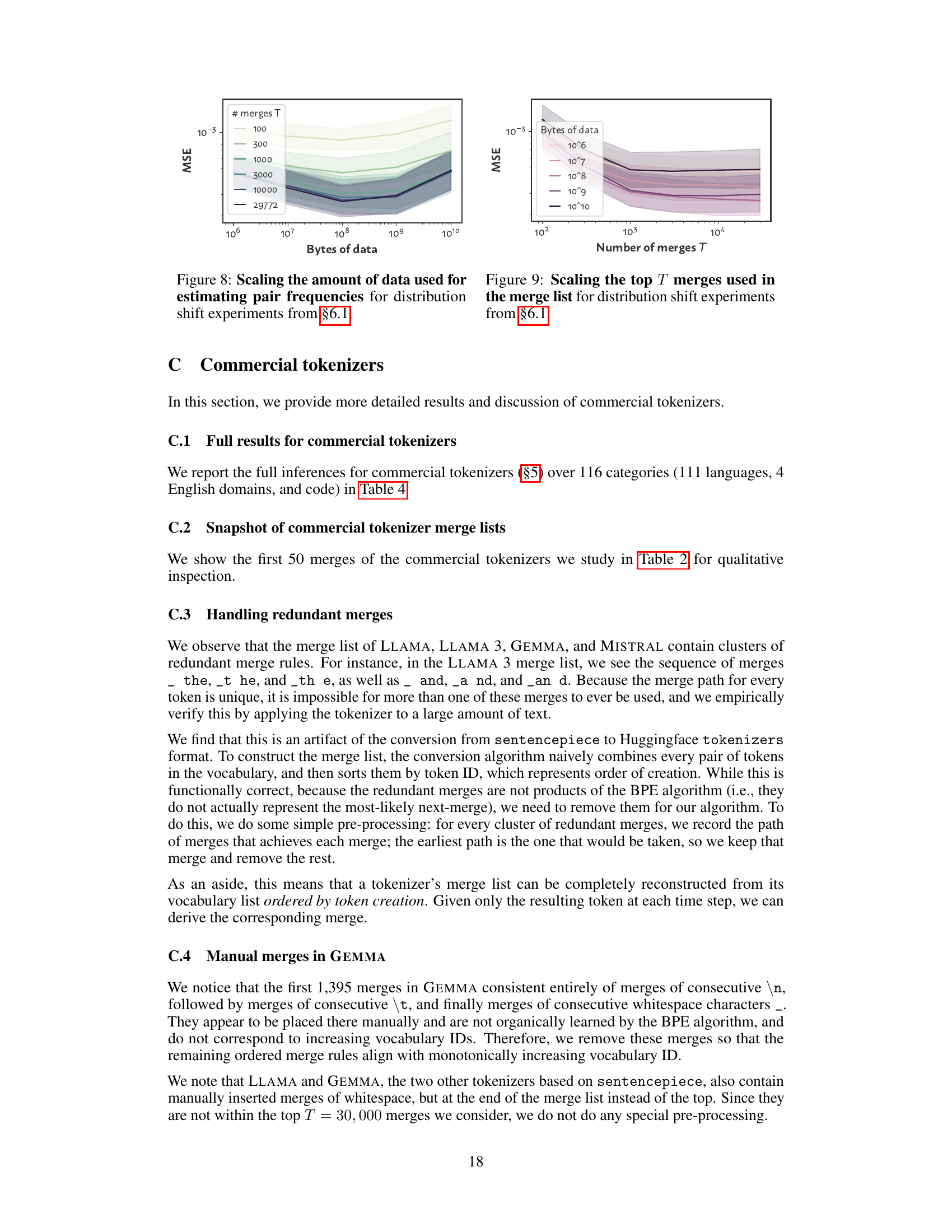

🔼 This figure shows how the accuracy of the data mixture inference attack changes with the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies, when using mixtures of 5 categories. As expected, increasing the amount of data per category improves the accuracy of the attack, as shown by the decrease in Mean Squared Error (MSE).

read the caption

Figure 6: Scaling the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies (§B.4.1), for mixtures of n = 5 categories. Sampling more data per category produces more precise inferences.

🔼 This figure shows how the accuracy of the data mixture inference attack changes with the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies. The experiment uses mixtures of 5 categories. As expected, using more data leads to more accurate results, indicated by lower MSE values.

read the caption

Figure 6: Scaling the amount of data used for estimating pair frequencies (§B.4.1), for mixtures of n = 5 categories. Sampling more data per category produces more precise inferences.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of controlled experiments conducted to evaluate the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack. Experiments were performed on mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains with varying numbers of categories (n). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the log10(Mean Squared Error, MSE) for the attack, compared to two baselines (TEE and TC) and random guessing. Lower MSE values indicate higher accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

🔼 This table presents the results of controlled experiments evaluating the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack. Experiments were conducted on various mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains, with varying numbers of categories (n). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the log10(mean squared error, MSE) for different methods (the proposed approach and two baselines). Lower MSE indicates higher accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

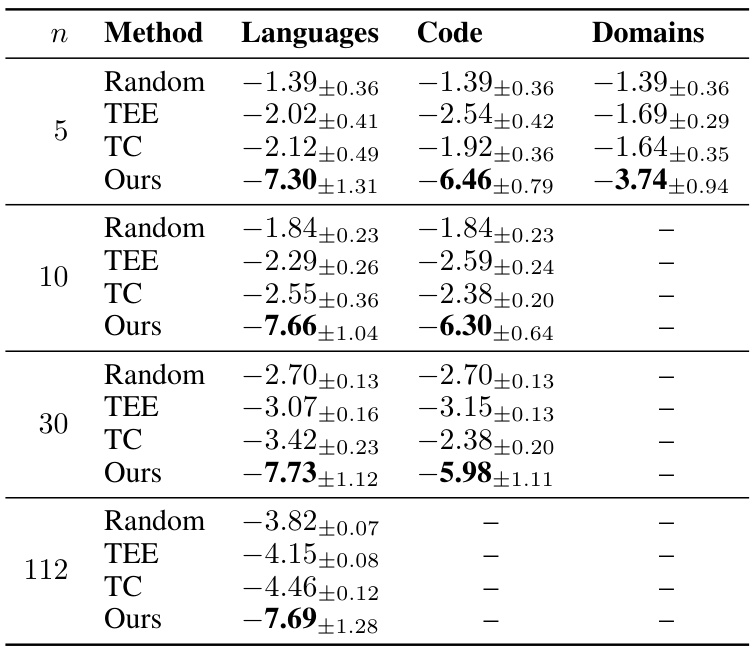

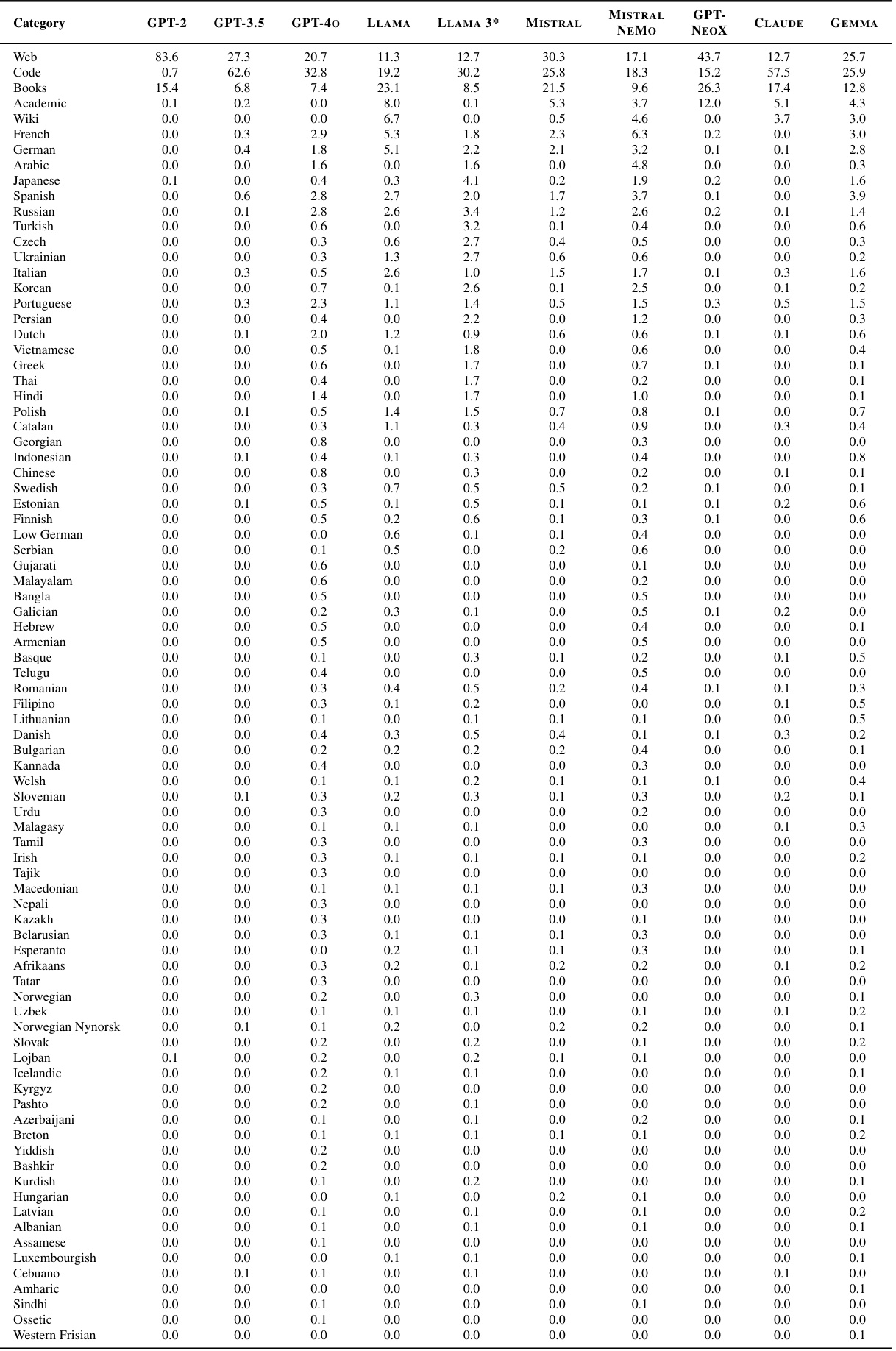

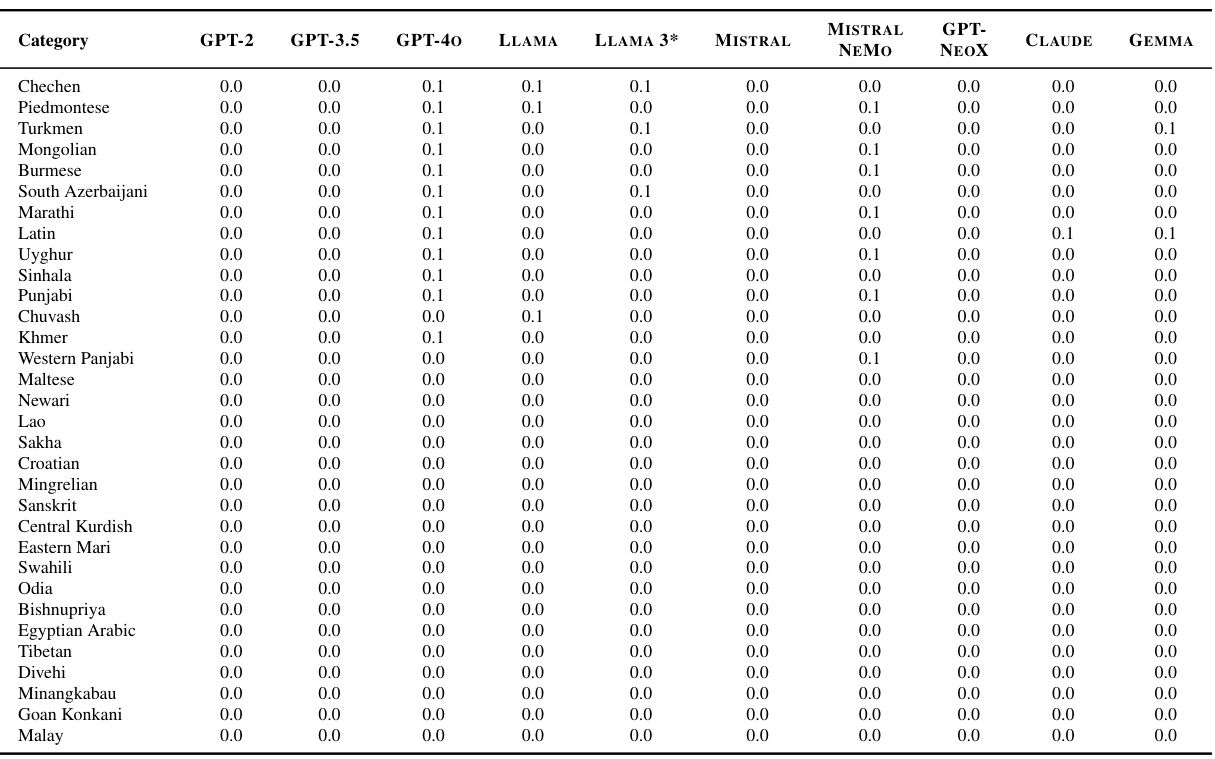

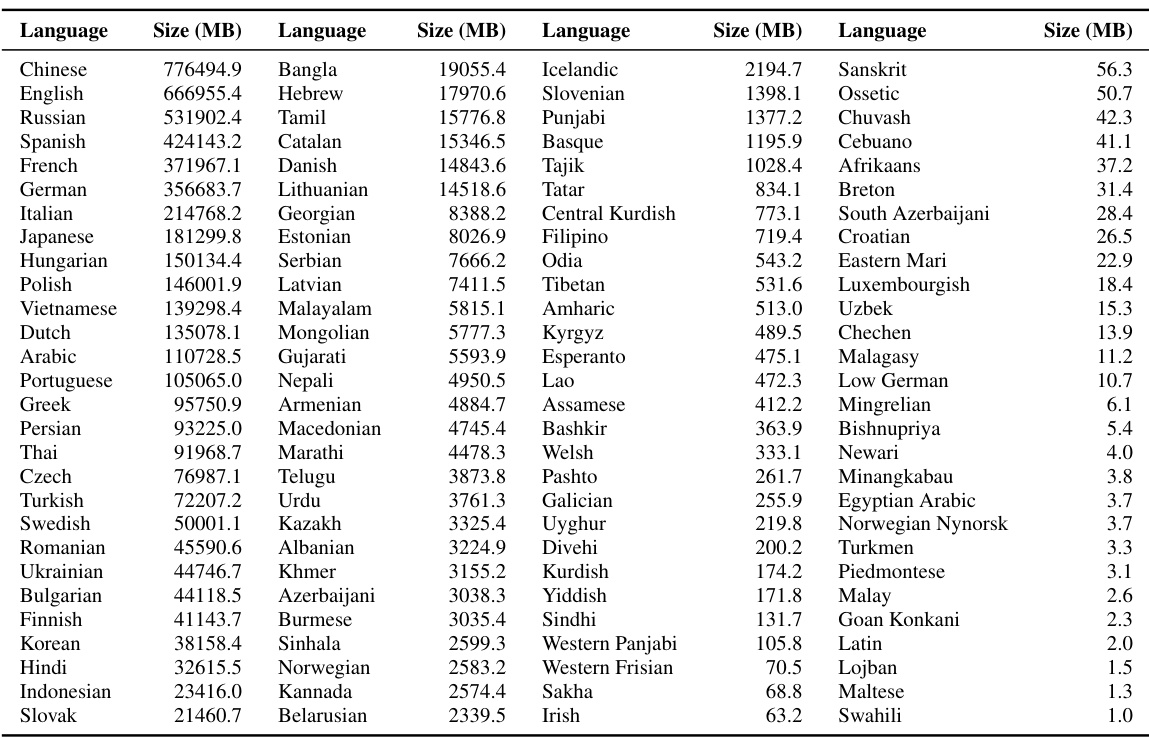

🔼 This table presents the detailed breakdown of the proportion of different categories (111 languages, web, books, academic, Wikipedia, and code) in the training data of various commercial language models’ tokenizers, as inferred by the proposed data mixture inference attack. The results for each tokenizer are given in separate columns.

read the caption

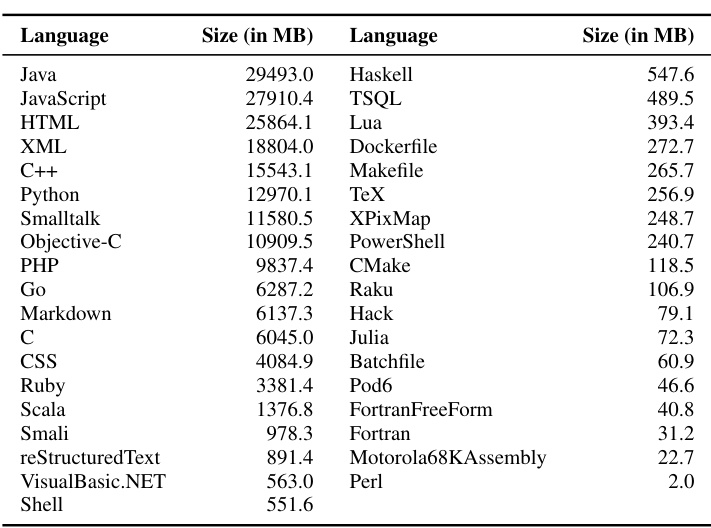

Table 4: Our full set of inferences for commercial tokenizers over 116 categories (111 languages, 4 English domains, and code). The four English domains are web, books, academic, and Wikipedia.

🔼 This table presents the detailed breakdown of the training data composition for several commercial language model tokenizers. It shows the proportions of 111 different languages, and four English domains (web, books, academic, Wikipedia), and code in the training data of each tokenizer. The tokenizers analyzed include those from the GPT, LLAMA, MISTRAL, and other model families.

read the caption

Table 4: Our full set of inferences for commercial tokenizers over 116 categories (111 languages, 4 English domains, and code). The four English domains are web, books, academic, and Wikipedia.

🔼 The table presents the results of controlled experiments evaluating the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack on various mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains. It compares the performance of the attack (Ours) against baselines (Random, TEE, TC) across different numbers of categories (n). The performance metric is the mean and standard deviation of the log10(Mean Squared Error), indicating the precision of the attack in recovering the mixture ratios.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

🔼 This table presents the results of controlled experiments evaluating the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack. Experiments were conducted on mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains, with varying numbers of categories (n). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the log10(mean squared error, MSE) for three methods: the proposed attack, Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency (TEE), and Token Classification (TC), in comparison to a random baseline. Lower MSE values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

🔼 This table presents the results of controlled experiments evaluating the accuracy of the proposed data mixture inference attack on tokenizers trained on known mixtures of natural languages, programming languages, and domains. It shows the mean and standard deviation of the log10(Mean Squared Error) for different numbers of categories (n) in the mixture, comparing the attack’s performance against random guessing and two other baseline methods (TEE and TC). Lower log10(MSE) values indicate better accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results for controlled experiments. The settings we consider are mixtures of natural languages, mixtures of programming languages, and mixtures of domains. n denotes the number of categories in the mixture, which are drawn from 112 natural languages, 37 programming languages, or 5 domains. In each cell, we report the mean and standard deviation of log10(MSE) over 100 trials; note that a decrease by 1 corresponds to a 10× improvement in the MSE. In addition to a Random-guessing baseline, we implement two alternative approaches to the problem: TEE (Tokenizer Encoding Efficiency) uses the tokenizer's encoding efficiency on each data category, and TC (Token Classification) assigns each token in the vocabulary to a data category based on frequency.

Full paper#