TL;DR#

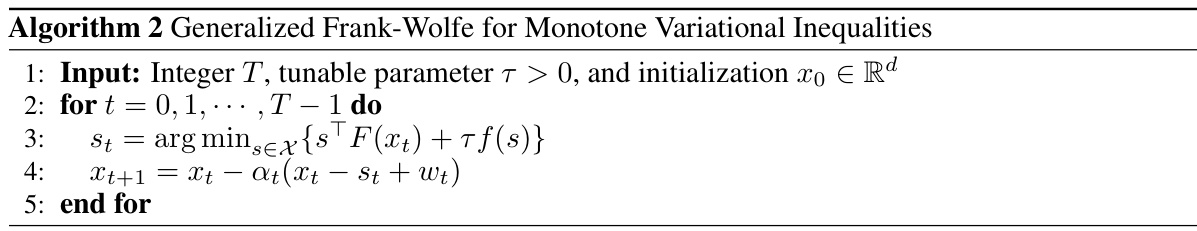

Monotone Variational Inequalities (MVIs) are prevalent in optimization and machine learning, but solving them efficiently, particularly in constrained and stochastic settings, remains a challenge. Existing methods often rely on strong assumptions or achieve slow convergence rates, hindering their application in real-world scenarios. This paper addresses these issues by focusing on a generalized Frank-Wolfe (FW) algorithm.

The paper introduces a generalized FW algorithm and demonstrates that it achieves fast last-iterate convergence for both deterministic and stochastic constrained MVIs. For deterministic MVIs, the algorithm reaches O(T⁻¹/²) convergence rate, and a slower O(T⁻¹/⁶) is obtained in the stochastic setting. The analysis connects the FW algorithm to smoothed fictitious play from game theory, leading to new convergence results. This offers a novel and effective approach to solving MVIs, especially in scenarios where strong curvature assumptions or noiseless data may not be realistic.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it provides the first last-iterate convergence guarantees for algorithms solving constrained stochastic monotone variational inequality (MVI) problems without strong curvature assumptions. This significantly advances the field, offering new theoretical insights and practical tools for tackling challenging optimization and machine learning tasks.

Visual Insights#

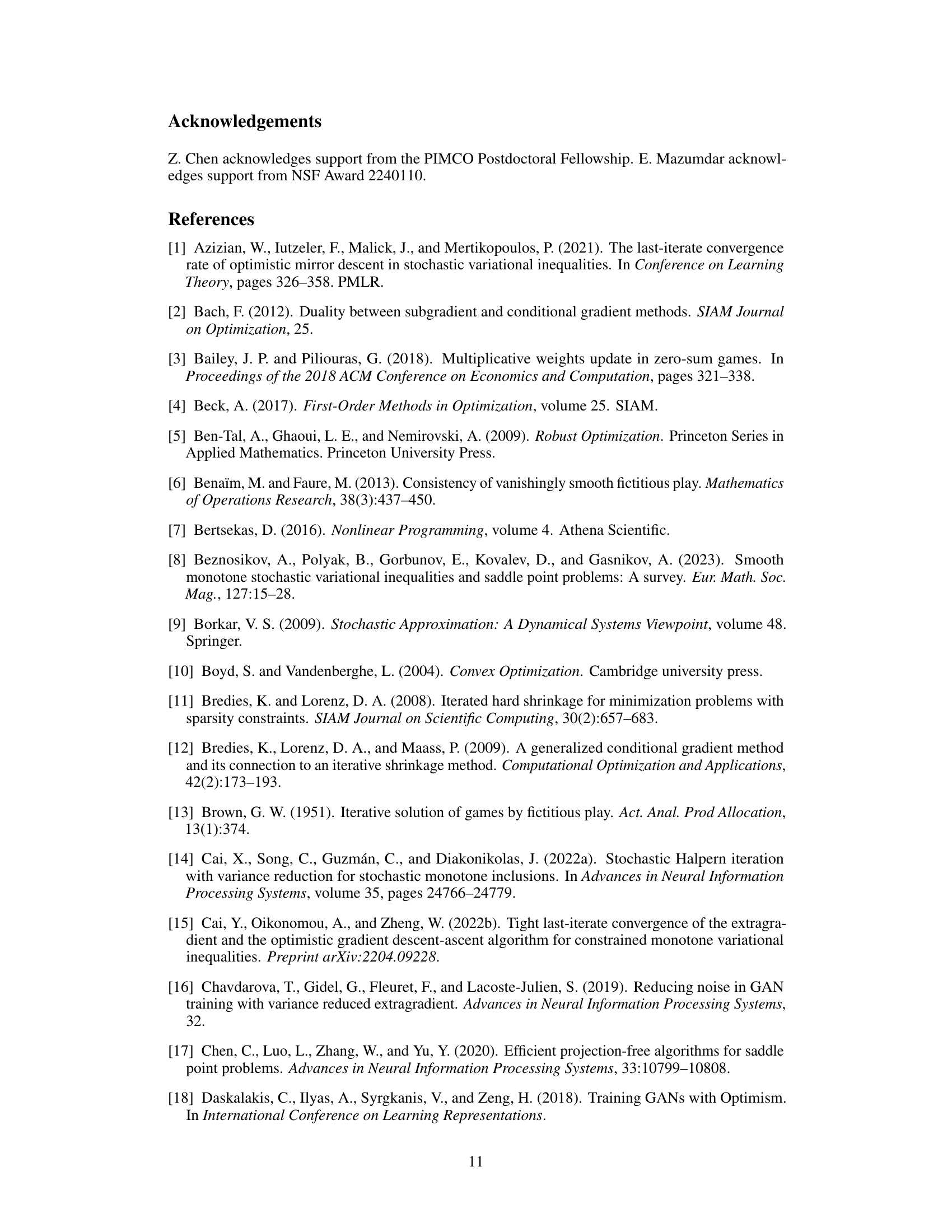

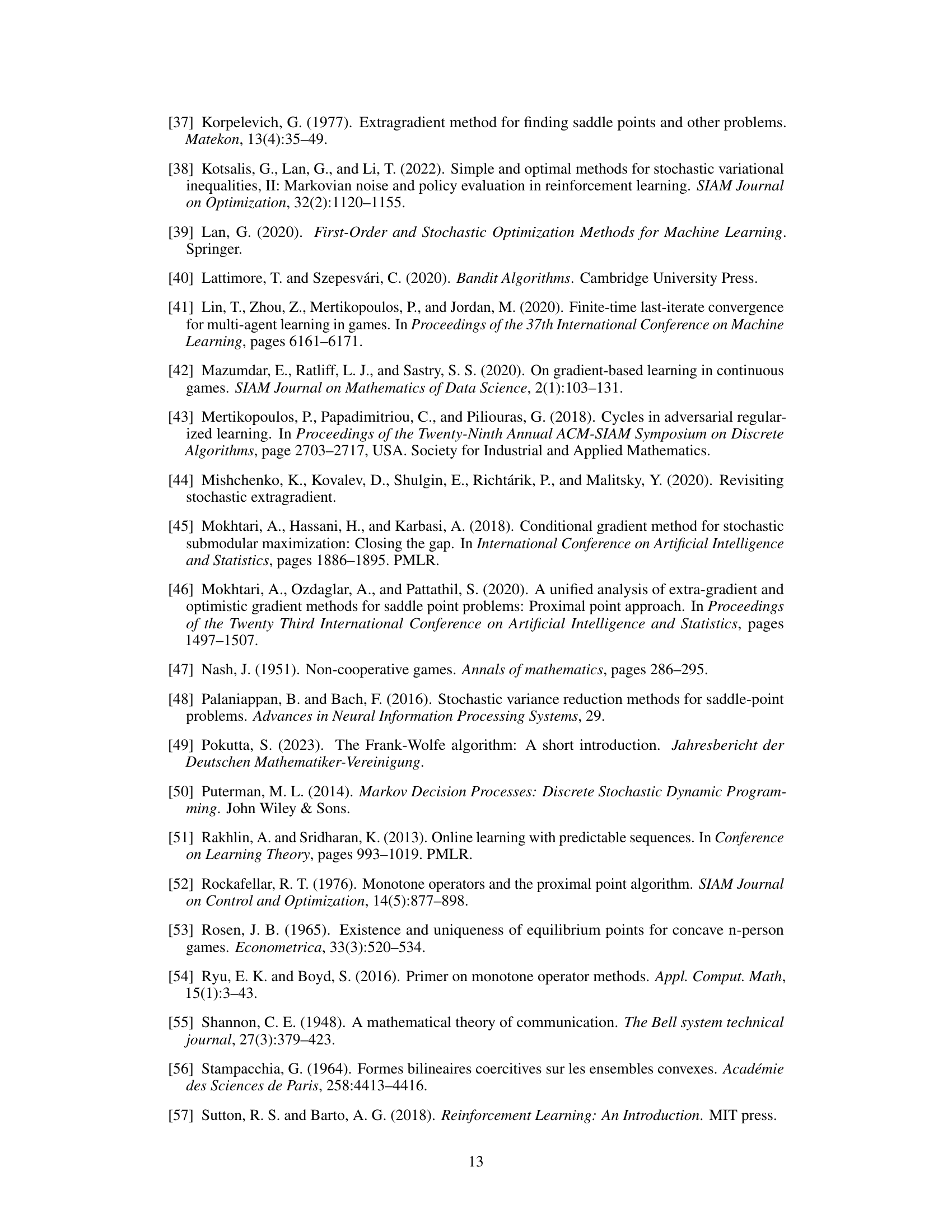

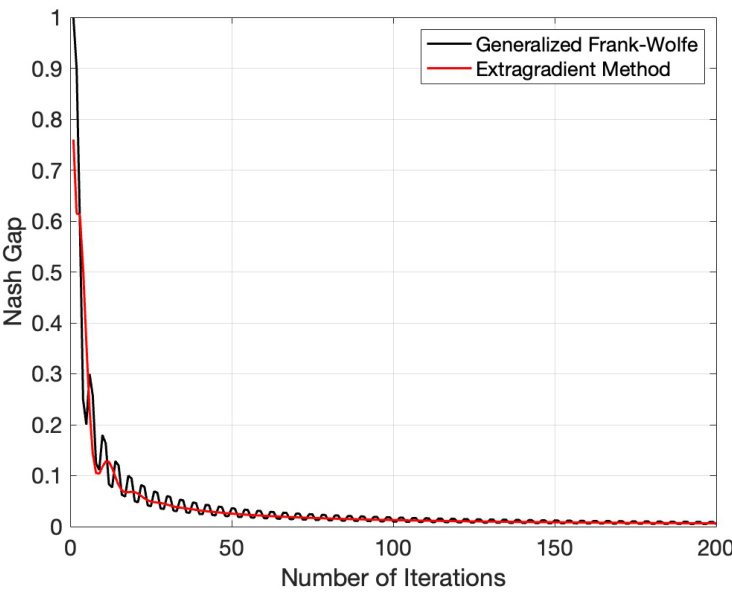

🔼 The figure compares the convergence rate of the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the extragradient method for solving the Rock-Paper-Scissors game, a classic example of a zero-sum game. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the Nash gap, which measures how far the players are from their best response. Both algorithms achieve a fast last-iterate convergence rate of O(T-1/2), as theoretically proven in the paper. The plot shows that the extragradient method tends to be more stable than the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm, especially in the beginning iterations, but their performances are close asymptotically.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

🔼 This figure compares the convergence rate of the Generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the Extragradient method on a Rock-Paper-Scissors game. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the Nash Gap, a measure of how far the current strategy is from a Nash equilibrium. The plot shows the Nash Gap over time for both algorithms, allowing for a visual comparison of their convergence speed in this specific game.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

In-depth insights#

FW’s Convergence#

The convergence analysis of Frank-Wolfe (FW) algorithms is a crucial aspect of their applicability to solving variational inequalities (VIs). Standard FW methods often suffer from slow convergence, particularly in high-dimensional spaces or when dealing with non-smooth objective functions. The paper likely explores modifications to the standard FW algorithm to improve convergence, perhaps through techniques like smoothing or regularization. These modifications are designed to address the limitations of the vanilla FW approach. A key element of the analysis would be establishing convergence rates, demonstrating how quickly the algorithm converges to a solution. The theoretical analysis may involve constructing Lyapunov functions or using other analytical techniques to prove convergence and bound the error. Different convergence guarantees might be derived for different problem settings, such as deterministic vs. stochastic VIs, or for VIs with specific properties of the objective function (e.g., convexity, smoothness). The authors likely contrast the convergence performance of their improved FW algorithm against existing VI solvers, highlighting potential advantages in terms of speed and computational efficiency. Ultimately, a strong focus on convergence behavior under various assumptions is critical to assess the practical usefulness of the proposed FW variants.

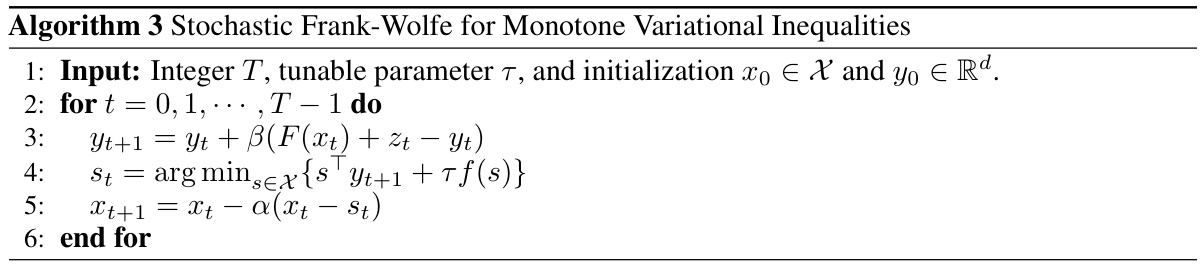

Stochastic FW#

The section on ‘Stochastic FW’ likely addresses the challenges and solutions for applying Frank-Wolfe algorithms in scenarios with noisy or stochastic gradient information. This is a crucial extension because real-world applications rarely provide perfect gradient measurements. The core of this discussion probably involves modifications to the standard Frank-Wolfe algorithm to handle the uncertainty introduced by stochasticity. Variance reduction techniques are likely explored to reduce the impact of noisy gradients on convergence. The analysis likely covers convergence rates under different assumptions about the noise, potentially demonstrating slower convergence compared to deterministic settings but still showing provable convergence guarantees. Two-timescale algorithms may be discussed, where a faster timescale updates gradient estimates, and a slower timescale executes the core Frank-Wolfe iterations, using the improved estimates. A key focus would likely be on proving last-iterate convergence, a property not always guaranteed with stochastic optimization methods. The impact of various parameters, such as step sizes, on convergence, and potentially the effect of different regularization strategies for handling noisy gradients would be explored. Ultimately, this section likely provides a valuable contribution by extending the applicability of Frank-Wolfe algorithms to a wider range of practical scenarios involving uncertainty.

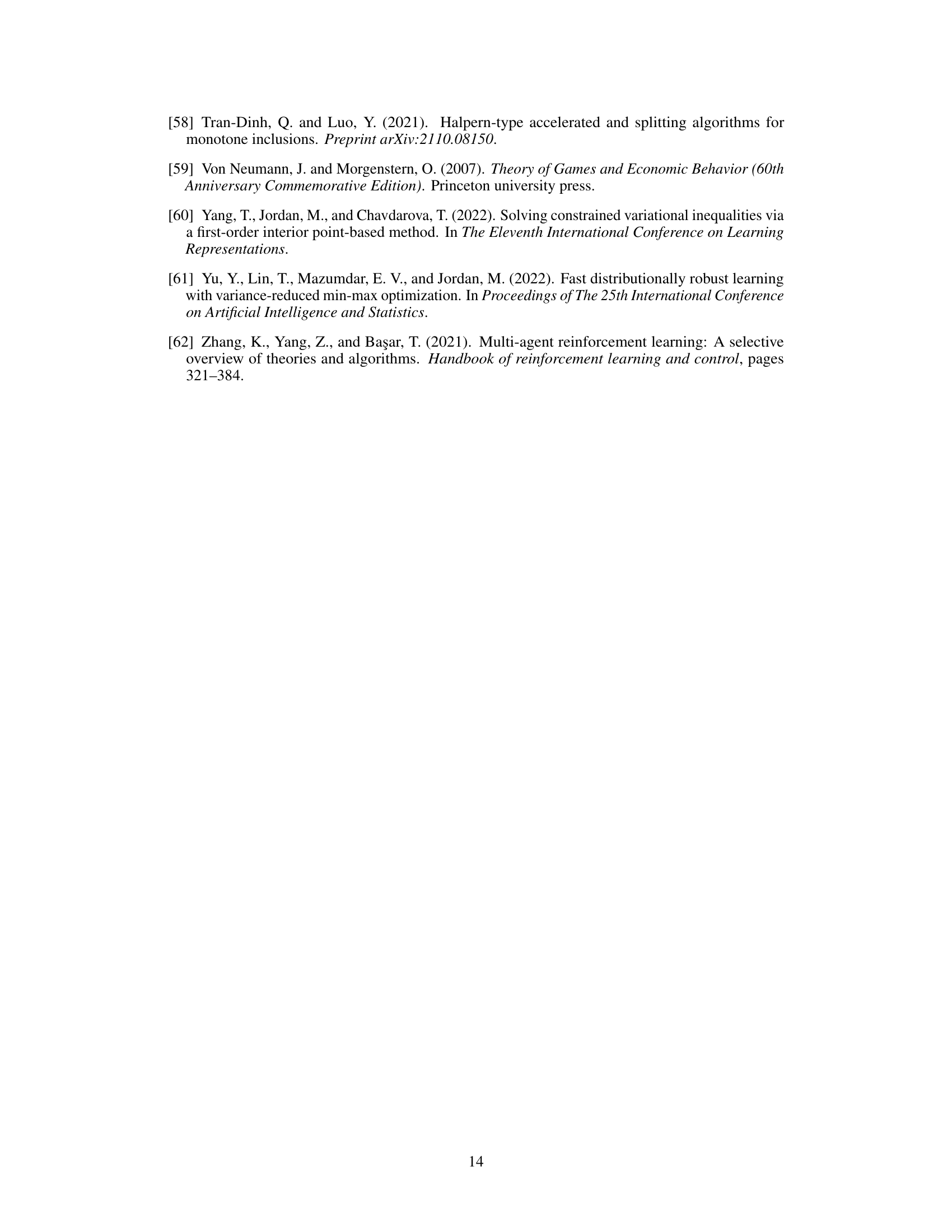

Smoothed FP#

The section on “Smoothed Fictitious Play” serves as a crucial bridge, connecting the theoretical framework of the research paper to its practical application. It introduces smoothed FP as a natural extension of standard fictitious play, addressing its limitations by incorporating a smoothing technique. This modification, achieved through the addition of an entropy regularizer, is key to ensuring convergence guarantees in zero-sum games, a significant improvement over the original algorithm. By meticulously analyzing smoothed FP, the authors establish a finite-sample convergence rate, proving its efficacy while highlighting its connection to a more generalized Frank-Wolfe method. This connection effectively sets the stage for extending the algorithm’s benefits to more complex constrained monotone variational inequalities. The smoothed FP algorithm’s analysis not only provides theoretical backing but also offers valuable insights for designing practical implementations within constrained environments. The transition from smoothed FP analysis to the generalized Frank-Wolfe method constitutes a smooth and natural progression of the paper’s argument.

MVI Algorithms#

Monotone variational inequality (MVI) algorithms are crucial for solving a wide range of problems in optimization, machine learning, and game theory. Gradient-based methods, such as extragradient and optimistic gradient, are popular due to their strong theoretical guarantees, achieving fast convergence rates under certain conditions. However, they often require strong assumptions such as smoothness or strong monotonicity. Frank-Wolfe (FW) methods provide an alternative approach, particularly attractive for constrained problems because they avoid explicit projections onto the feasible set. This paper explores a generalized FW algorithm, showing its fast last-iterate convergence for constrained MVIs. The introduction of smoothing techniques proves key to obtaining these results, effectively addressing some of the limitations associated with standard FW. Furthermore, the paper extends the algorithm to the stochastic setting, where noisy estimates of the operator are available, achieving slower but still meaningful convergence rates. This research contributes valuable insights into the broader landscape of MVI solvers, highlighting the potential benefits of FW-type algorithms.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of this research paper would ideally explore several promising avenues. Extending the stochastic generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm to handle non-convex settings would be a significant contribution, as many real-world problems lack the convexity assumptions made in the current work. Investigating tighter convergence rates for both the deterministic and stochastic algorithms is crucial; the current O(T-1/2) and O(T-1/6) rates might not be optimal. A rigorous comparison with other state-of-the-art methods for solving stochastic MVI problems, including those that utilize curvature assumptions, is needed to establish the practical advantages of the proposed approach. Finally, applying the algorithm to specific real-world problems, such as those in reinforcement learning or game theory, would demonstrate its effectiveness and potential impact. This would involve careful selection of problems and robust experimental design to showcase the algorithm’s performance against existing solutions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares the convergence rates of the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the extragradient method on the Rock-Paper-Scissors game. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the Nash Gap, a measure of how far the current strategy is from a Nash Equilibrium. The graph shows that both methods exhibit convergence, but the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm initially converges faster before the extragradient method eventually outperforms it asymptotically.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

🔼 This figure compares the convergence rates of the Generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the Extragradient method on the Rock-Paper-Scissors game. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the Nash Gap, a measure of how far the current strategies are from a Nash equilibrium. The plot shows the Nash Gap decreasing over iterations for both algorithms, indicating convergence. The Generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm shows faster initial convergence but the Extragradient method seems to be more stable in the long run, converging to a lower Nash Gap.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

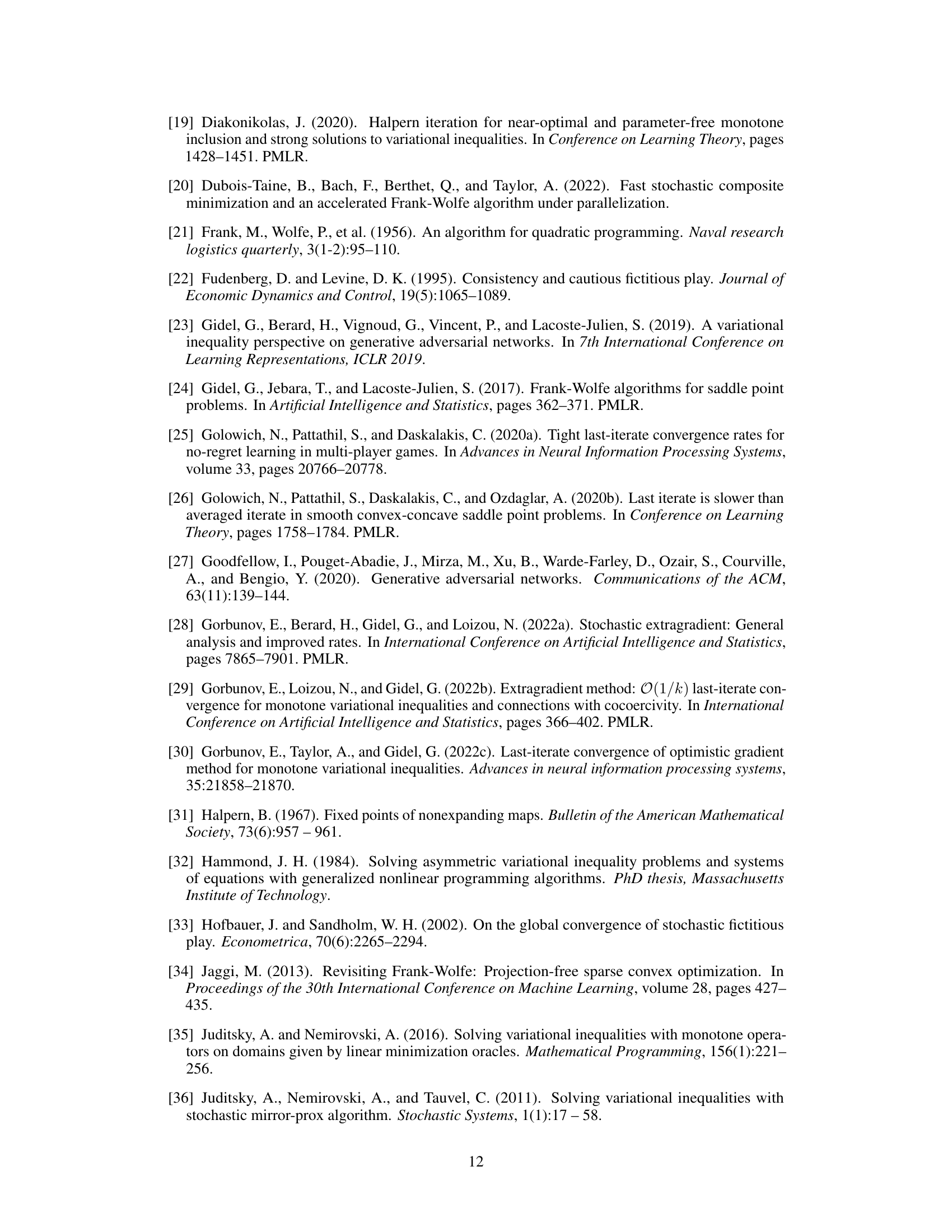

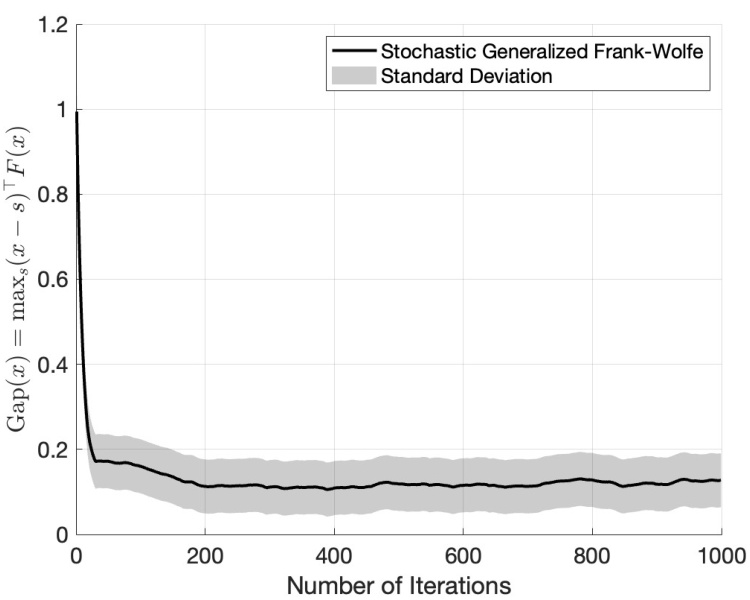

🔼 This figure shows the convergence of the stochastic generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm (Algorithm 3 in the paper) in a stochastic setting. The black line represents the average gap, which is the measure of how far the current iterate is from being a solution to the monotone variational inequality problem. The grey area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs, illustrating the variability introduced by the stochasticity. The algorithm shows convergence, but not to zero because of the presence of noise in the stochastic setting. The result aligns with Theorem 5.1 which discusses convergence in such scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 4: Convergence of Algorithm 3

More on tables

🔼 This figure compares the convergence rates of the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the extragradient method on the Rock-Paper-Scissors game. The plot shows the Nash Gap (a measure of how far the players are from a Nash equilibrium) over a number of iterations. It visually demonstrates the performance difference between the two algorithms in this specific game setting.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

🔼 The figure compares the convergence rate of the Generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the Extragradient method for a randomly generated matrix game. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the Nash gap, a measure of how far each player is from their best response. The plot shows that while the Generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm slightly outperforms the extragradient method initially, the extragradient method asymptotically performs better.

read the caption

Figure 3: Convergence Rate Comparison for

🔼 This figure compares the convergence rates of the generalized Frank-Wolfe algorithm and the extragradient method for solving the Rock-Paper-Scissors game, a classic example of a zero-sum game. The y-axis shows the Nash gap, a measure of how far the players are from the Nash equilibrium, and the x-axis represents the number of iterations. The plot visualizes the algorithms’ convergence towards equilibrium over time.

read the caption

Figure 1: Convergence Rate Comparison for the Rock-Paper-Scissors Game

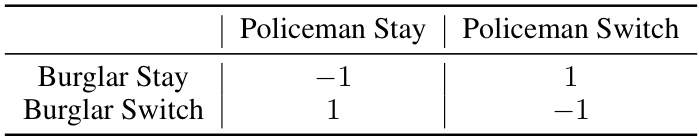

🔼 This table shows the payoff matrix for the Burglar-Policeman game, a zero-sum game where the Burglar aims to avoid capture and the Policeman aims to catch the burglar. The rows represent the burglar’s actions (Stay or Switch), and the columns represent the policeman’s actions (Stay or Switch). The entries in the matrix represent the payoff to the burglar, with positive numbers indicating a win for the burglar and negative numbers indicating a win for the policeman.

read the caption

Table 2: The Burglar-Policeman Matrix Game

Full paper#