TL;DR#

Existing methods for aligning AI models with human preferences often involve extensive fine-tuning, which is inefficient, particularly for large, black-box models. This often leads to issues such as scalability and overfitting. This research tackles these challenges.

The proposed Preference Flow Matching (PFM) framework directly learns a preference flow, effectively transforming less-preferred outputs into preferred ones, without relying on reward models or extensive fine-tuning. The method is shown to be robust to overfitting and provides comparable or even superior performance to existing methods across various tasks including text and image generation and reinforcement learning, demonstrating its practical effectiveness and broad applicability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it offers a novel and efficient way to align pre-trained models with human preferences, a crucial step in developing more human-centered AI systems. Its flow-matching approach bypasses the limitations of traditional fine-tuning methods, especially beneficial for large black-box models. The robust theoretical analysis and experimental results demonstrate the method’s effectiveness and open new directions for future research in preference-based learning and AI alignment.

Visual Insights#

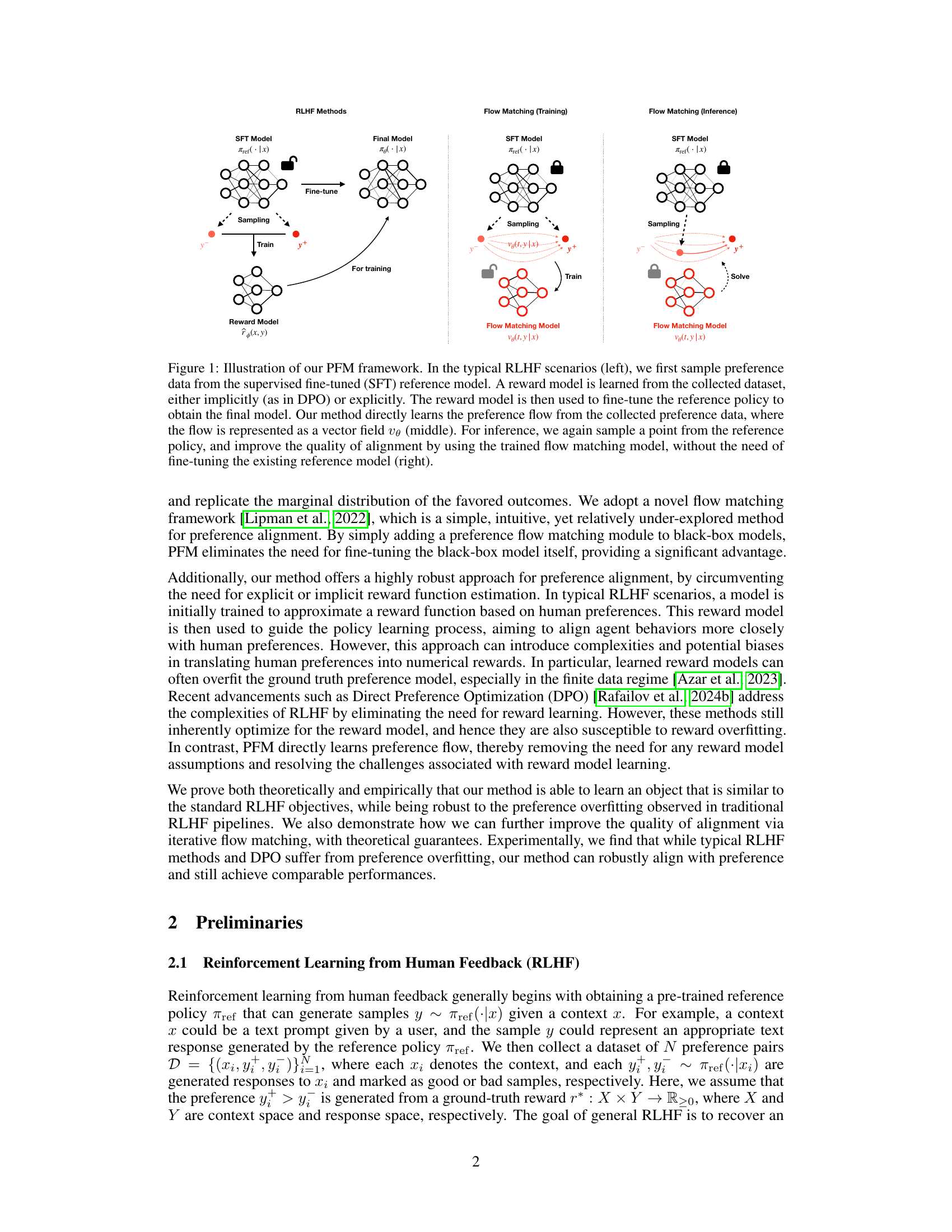

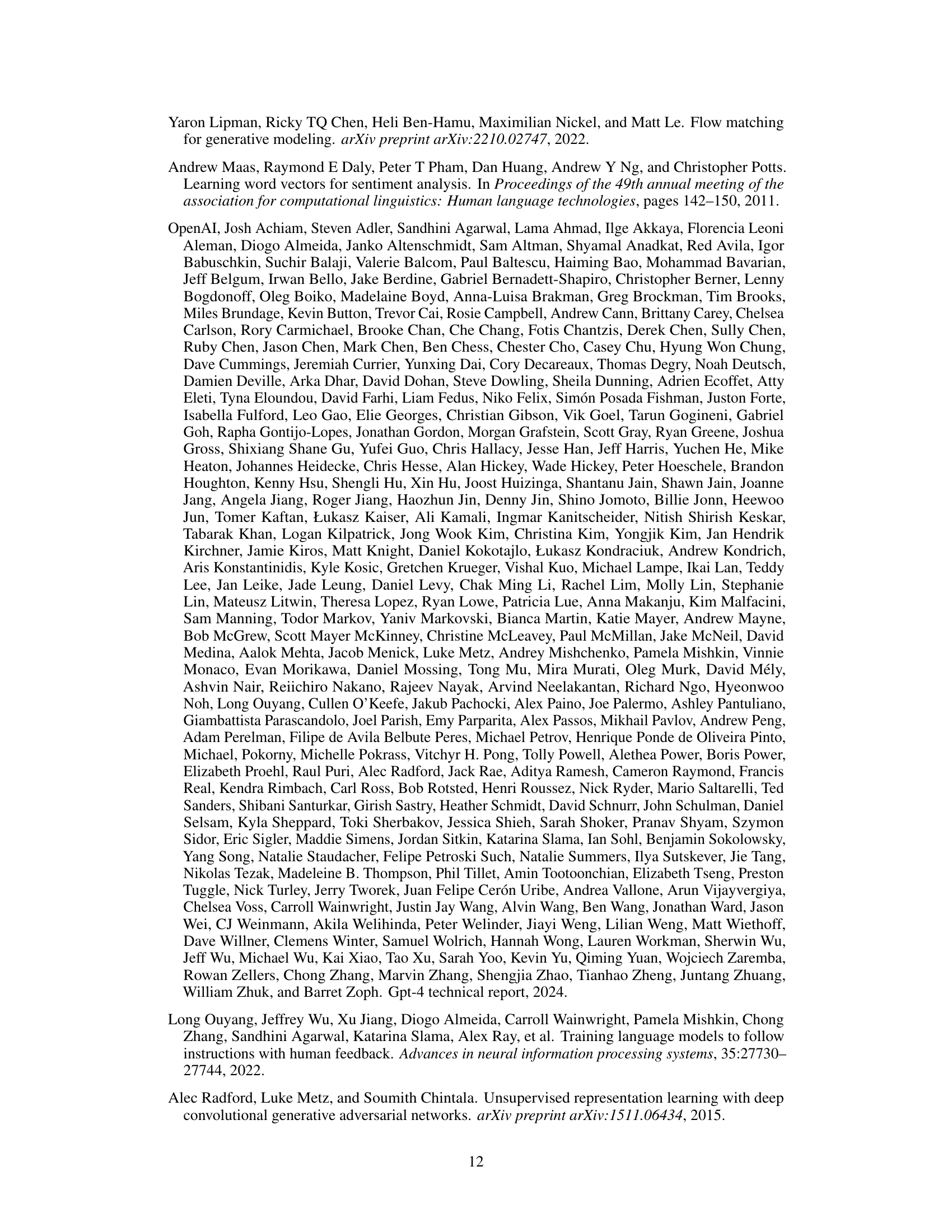

🔼 This figure illustrates the Preference Flow Matching (PFM) framework, comparing it to traditional Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) methods. RLHF methods involve sampling from a pre-trained model, training a reward model, and then fine-tuning the pre-trained model. In contrast, PFM directly learns a preference flow, transforming less preferred data points into preferred ones without the need for explicit reward models or model fine-tuning. The figure shows this process in three stages: RLHF, PFM training, and PFM inference.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our PFM framework. In the typical RLHF scenarios (left), we first sample preference data from the supervised fine-tuned (SFT) reference model. A reward model is learned from the collected dataset, either implicitly (as in DPO) or explicitly. The reward model is then used to fine-tune the reference policy to obtain the final model. Our method directly learns the preference flow from the collected preference data, where the flow is represented as a vector field ve (middle). For inference, we again sample a point from the reference policy, and improve the quality of alignment by using the trained flow matching model, without the need of fine-tuning the existing reference model (right).

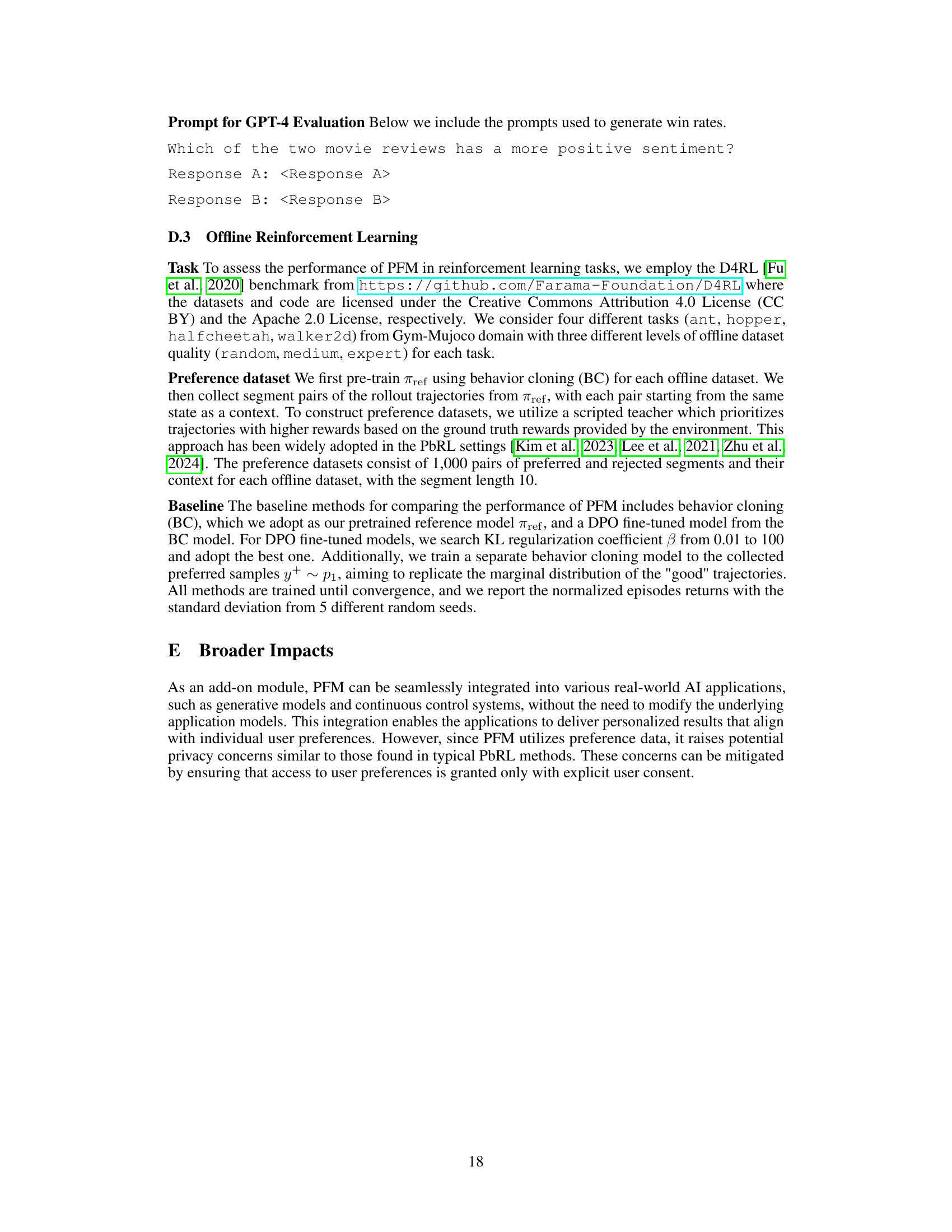

🔼 This table presents the average preference scores obtained from 100 test instances for three different methods: a pre-trained reference model (πref), the reference model with the proposed Preference Flow Matching (PFM) method added (πref + PFM), and the reference model with iterative PFM applied five times (πref + PFM × 5). The results show a significant improvement in preference scores when PFM is used, especially with iterative applications.

read the caption

Table 1: Average preference scores of 100 test instances.

In-depth insights#

Pref. Flow Matching#

The concept of ‘Pref. Flow Matching’ presents a novel approach to preference alignment in machine learning models, particularly addressing the limitations of traditional fine-tuning methods. It cleverly bypasses the need for explicit reward function engineering, a common bottleneck in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), by directly learning a flow that transforms less-preferred outputs into more-preferred ones. This is achieved through flow-based models, effectively mapping the distribution of less desirable outputs to a distribution of preferred outcomes. This method’s strength lies in its adaptability to black-box models, eliminating the need for model modification or access to internal parameters, a critical advantage when dealing with APIs like GPT-4. Theoretically, the approach demonstrates robustness against reward model overfitting and aligns with standard preference alignment objectives. Empirically, the results highlight the effectiveness of ‘Pref. Flow Matching’ in various domains, suggesting that it offers a scalable and efficient alternative to existing preference alignment techniques, especially when working with large, pre-trained models.

Flow-Based Alignment#

Flow-based alignment presents a novel approach to preference learning in machine learning models, particularly focusing on integrating human preferences without extensive retraining. This method bypasses the traditional reward-model learning phase, a common bottleneck in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), which often leads to overfitting and suboptimal performance. By employing flow-based models, the technique directly learns a mapping from less-preferred to more-preferred outputs. This direct approach offers scalability and efficiency advantages, especially when dealing with black-box models or APIs where internal model modification is impossible. The core idea is to learn a ‘preference flow’, a transformation that guides less desirable model outputs towards the preferred ones, aligning model behavior with human feedback. A key benefit is robustness against overfitting, a persistent challenge in RLHF methodologies that depend on accurately learning a reward model. The theoretical underpinnings support the effectiveness of this method, establishing a connection between flow-based alignment and standard preference alignment objectives. Empirical evaluations demonstrate promising results across various tasks, showcasing its practicality and potential for broader applications. However, careful consideration of limitations and potential biases remains important for responsible implementation.

Iterative Refinement#

The concept of “Iterative Refinement” in the context of preference alignment suggests a process of successively improving model outputs based on iterative feedback. This approach contrasts with methods that rely on a single round of fine-tuning. Iterative refinement’s strength lies in its ability to gradually align model behavior with human preferences, avoiding the potential pitfalls of overfitting or misinterpreting a one-time feedback signal. Each iteration allows for a more nuanced understanding of preferences, leading to better alignment. The core idea involves iteratively sampling model outputs, collecting preference feedback, and then using this feedback to adjust the model or the preference learning process. This could involve retraining a reward model, adjusting the parameters of a flow-based model (as in the Preference Flow Matching method), or even modifying the sampling strategy. However, iterative refinement may introduce computational challenges, as each iteration requires additional computation. The effectiveness of iterative refinement hinges on the quality and consistency of the preference feedback; noisy or conflicting feedback can hinder progress. Also, the trade-off between the gain in accuracy from additional iterations and the increasing computational cost needs careful consideration.

Overfitting Robustness#

The concept of ‘overfitting robustness’ in the context of preference alignment is crucial. Traditional reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) methods often suffer from reward model overfitting, where the model learns to exploit quirks in the training data rather than genuinely aligning with human preferences. Preference Flow Matching (PFM) directly addresses this by bypassing the explicit reward model. Instead of learning a reward function, PFM learns a preference flow, transforming less-preferred data points into preferred ones. This avoids the issue of overfitting the reward model entirely, resulting in a more generalized and robust alignment. The theoretical analysis within the paper likely supports this claim, potentially demonstrating that PFM’s objective function is inherently more resistant to overfitting than traditional RLHF’s. This is a significant advantage, as overfitting can severely limit the generalizability of the aligned model, especially to unseen data or different preference distributions.

Future Extensions#

The paper’s core contribution is a novel preference alignment method, Preference Flow Matching (PFM), which avoids the limitations of traditional methods by directly learning preference flows instead of relying on reward model estimation. Future extensions could explore several promising avenues. First, developing more sophisticated flow models beyond simple vector fields could significantly enhance PFM’s performance and robustness. This could involve investigating more advanced normalizing flows or diffusion models to capture more complex preference distributions. Second, scaling PFM to handle longer sequences and higher-dimensional data is crucial for broader applicability. This necessitates developing efficient and effective strategies for managing the computational complexity of handling extensive data. Third, extending PFM to handle diverse feedback modalities beyond simple pairwise comparisons would increase its versatility. Finally, rigorous theoretical analysis to provide stronger guarantees on convergence and generalization performance would be beneficial, as well as empirical comparisons with a wider range of baseline methods and datasets across diverse tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

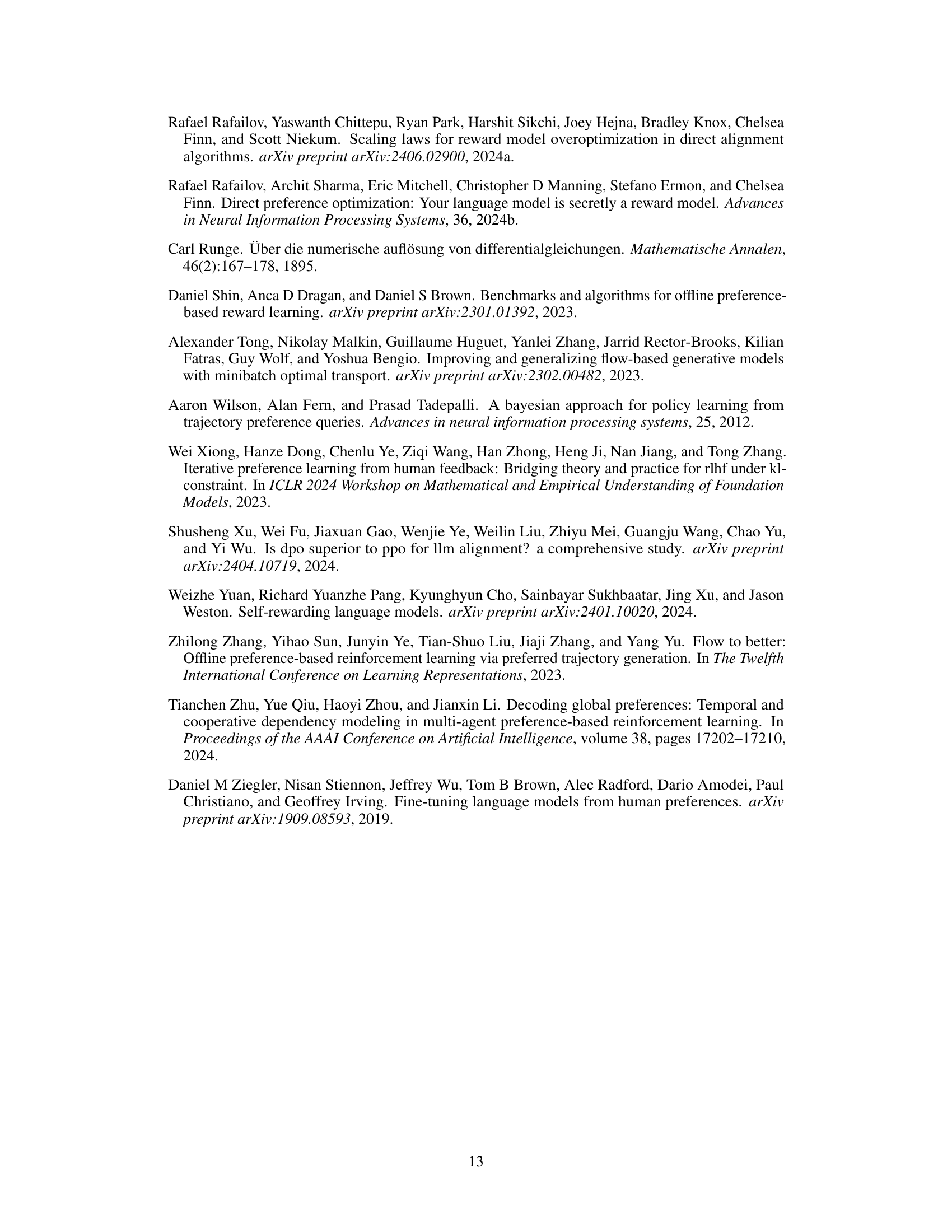

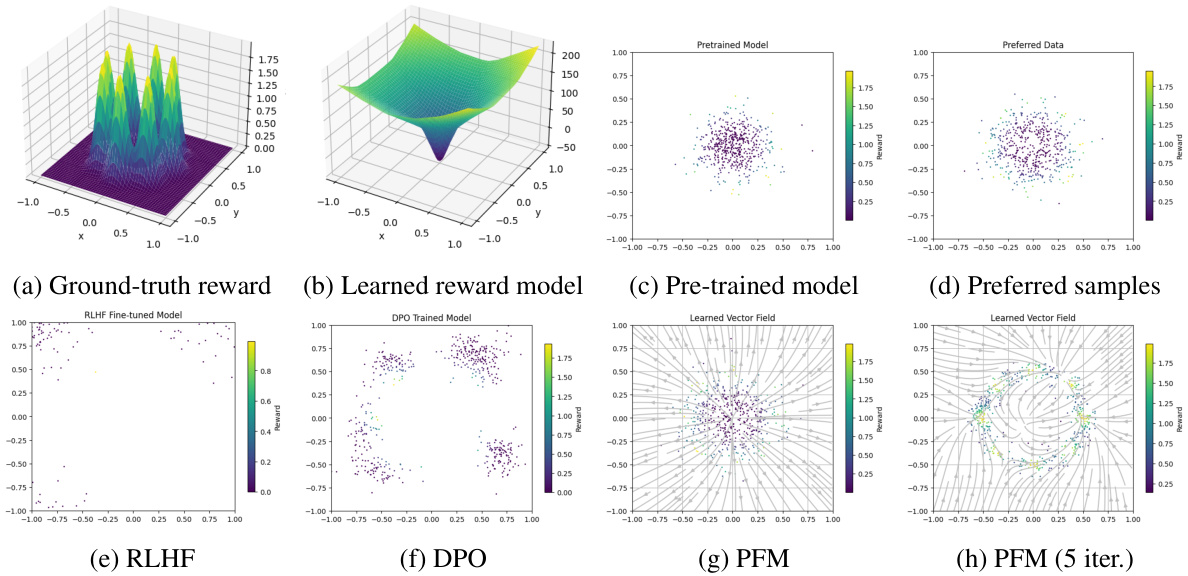

🔼 This figure compares the performance of RLHF, DPO, and PFM on a simple 2D toy problem where the goal is to learn a preference from samples generated by a pre-trained model. The ground truth reward function (a) is shown, along with the learned reward model by RLHF which overfits (b), the pre-trained model samples (c), preferred samples (d), and the results of RLHF (e), DPO (f), PFM (g), and iterative PFM (h). PFM shows superior performance because it directly learns the preference flow rather than relying on a reward model, thus avoiding overfitting.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of RLHF, DPO, and PFM on a 2-dimensional toy experiment. We generate preference labels from a ground truth reward in (a) and a pre-trained Gaussian reference policy (c). Both the RLHF (e) and DPO (f) methods struggle to align with the preferences, due to the overfitted reward model (b), even with the presence of KL regularizer (β = 1). PFM is able to mimic the distribution of the positively-labeled samples (d), and therefore achieves the highest performance (g). Repeating PFM iteratively to the marginal samples can further improve the alignment with the preference (h).

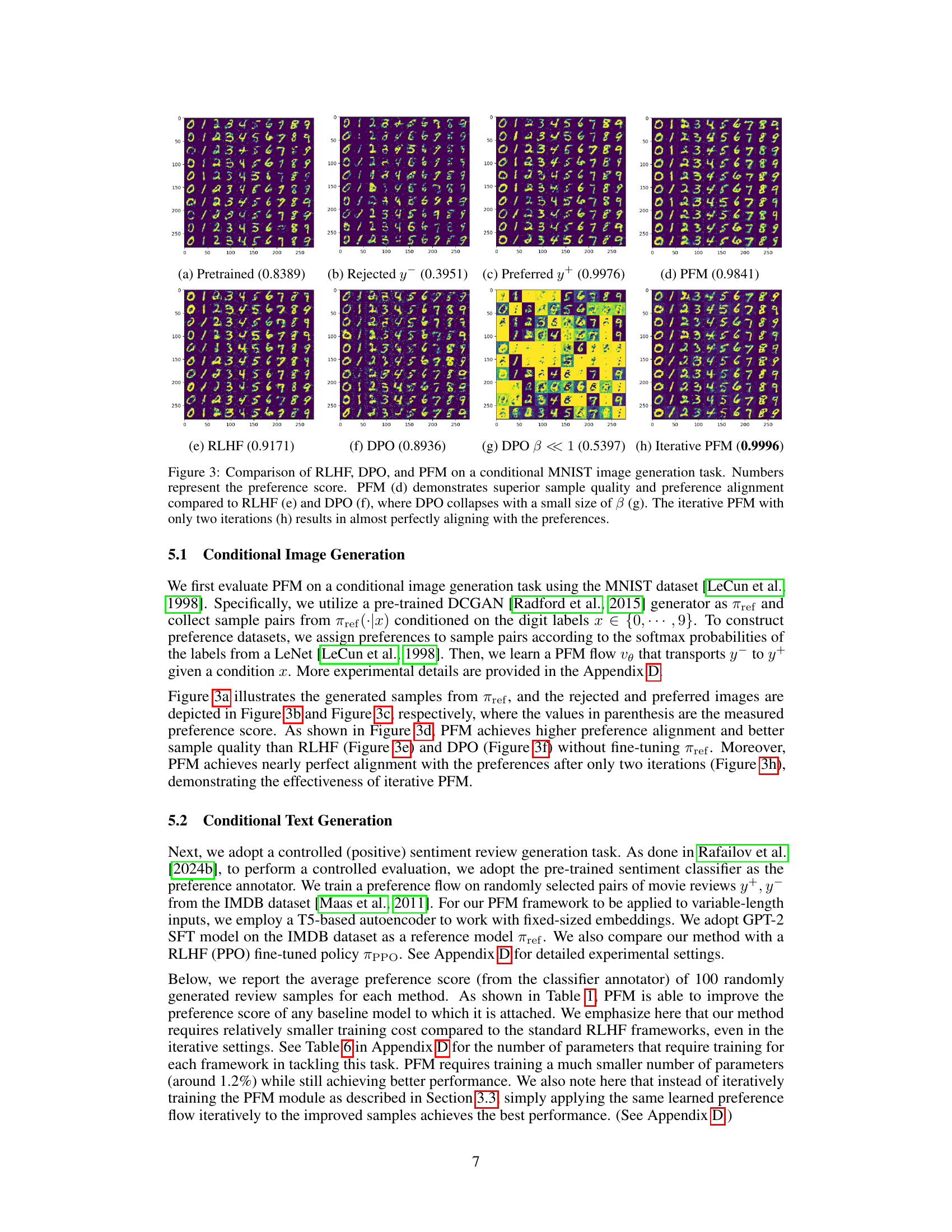

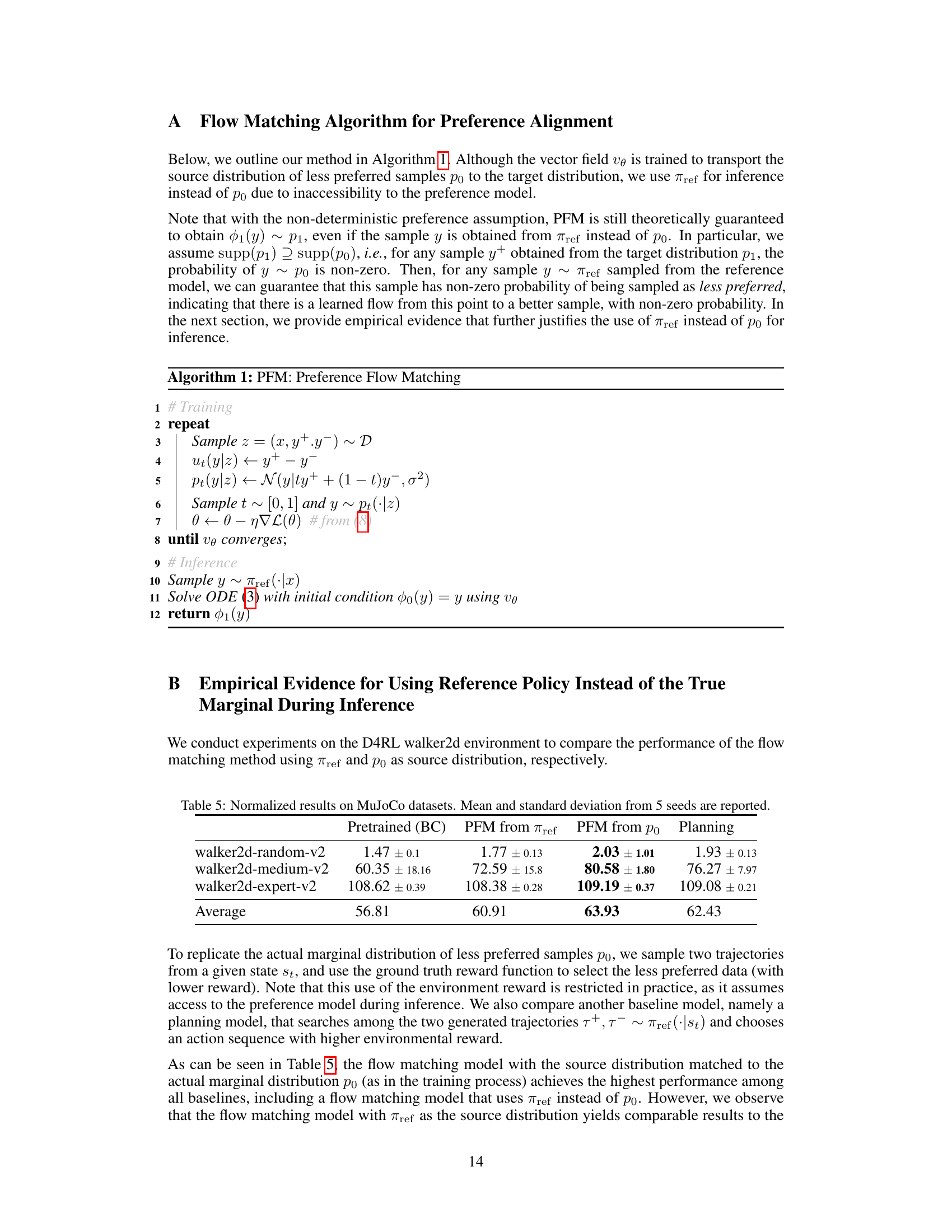

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three different preference alignment methods: RLHF, DPO, and the proposed PFM, on a conditional MNIST image generation task. The images generated by a pre-trained model and then modified by each method are shown, along with their associated preference scores. The results visually demonstrate that PFM produces higher-quality images that better align with human preferences than RLHF and DPO, especially when using an iterative approach. The DPO method’s performance significantly degrades with a smaller beta value, highlighting its sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning. In contrast, the iterative PFM shows nearly perfect alignment, suggesting the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of RLHF, DPO, and PFM on a conditional MNIST image generation task. Numbers represent the preference score. PFM (d) demonstrates superior sample quality and preference alignment compared to RLHF (e) and DPO (f), where DPO collapses with a small size of β (g). The iterative PFM with only two iterations (h) results in almost perfectly aligning with the preferences.

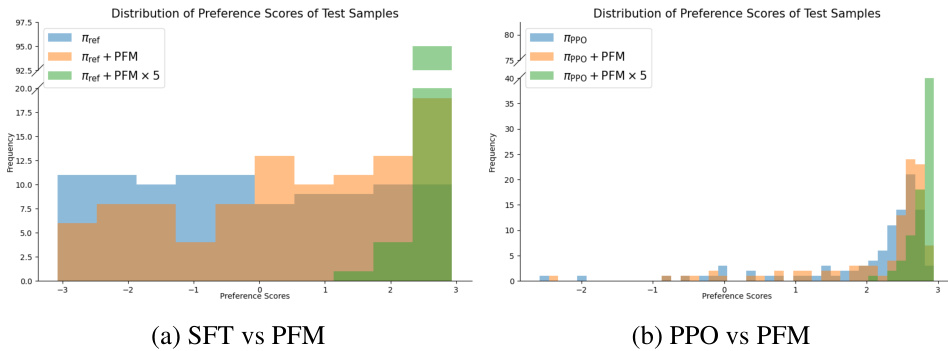

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of preference scores obtained by different methods: the pre-trained reference model, the reference model with PFM, and the reference model with iterative PFM (5 iterations). The left panel compares the pre-trained model (SFT) against the same model enhanced with PFM, highlighting the improvement in preference scores after adding the PFM module. Similarly, the right panel compares the RLHF (PPO) fine-tuned model and the same model enhanced with PFM, showcasing the robustness of PFM to overfitting.

read the caption

Figure 4: Distribution of preference scores for each method. Left visualizes the distribution of scores for the pre-trained reference policy and PFM-attached policy. Without fine-tuning the reference policy, PFM can obtain substantially better results by only adding a small flow-matching module. Right visualizes the preference score distribution of the RLHF (PPO) fine-tuned policy, and the PFM added policy to the PPO fine-tuned policy. Note that PFM is trained with the original dataset, not by the dataset generated from the PPO fine-tuned policy.

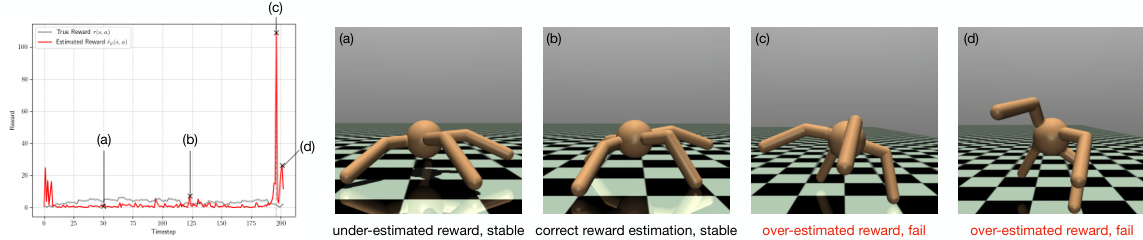

🔼 Figure 5 shows an example of a DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) model’s behavior during an episode in the MuJoCo Ant environment. The figure demonstrates the consequences of reward overfitting, where the DPO model consistently overestimates the reward (as indicated by the red line exceeding the true reward in the graph, specifically around time step 196). This overestimation leads to poor policy choices, resulting in unstable and ultimately unsuccessful actions by the ant agent. The implicit reward estimation used in this process is shown to be ĉe(s, a) = βlog(πρ(as)/πref(as)).

read the caption

Figure 5: Analysis of a sample episode of a DPO fine-tuned model on the MuJoCo ant environment. DPO fine-tuned model often overestimates the reward due to reward overfitting (e.g., t = 196). This can cause the policy to choose problematic actions. Here, the implicit reward estimation is ĉe(s, a) = βlog(πρ(as)/πref(as)).

🔼 The figure illustrates the Preference Flow Matching (PFM) framework, comparing it to standard Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) methods. RLHF methods (left) use a reward model, trained on sampled preferences, to fine-tune a pre-trained model. PFM (middle and right) directly learns a preference flow, a vector field, that transforms less preferred outputs into preferred ones, without requiring fine-tuning of the pre-trained model.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our PFM framework. In the typical RLHF scenarios (left), we first sample preference data from the supervised fine-tuned (SFT) reference model. A reward model is learned from the collected dataset, either implicitly (as in DPO) or explicitly. The reward model is then used to fine-tune the reference policy to obtain the final model. Our method directly learns the preference flow from the collected preference data, where the flow is represented as a vector field ve (middle). For inference, we again sample a point from the reference policy, and improve the quality of alignment by using the trained flow matching model, without the need of fine-tuning the existing reference model (right).

More on tables

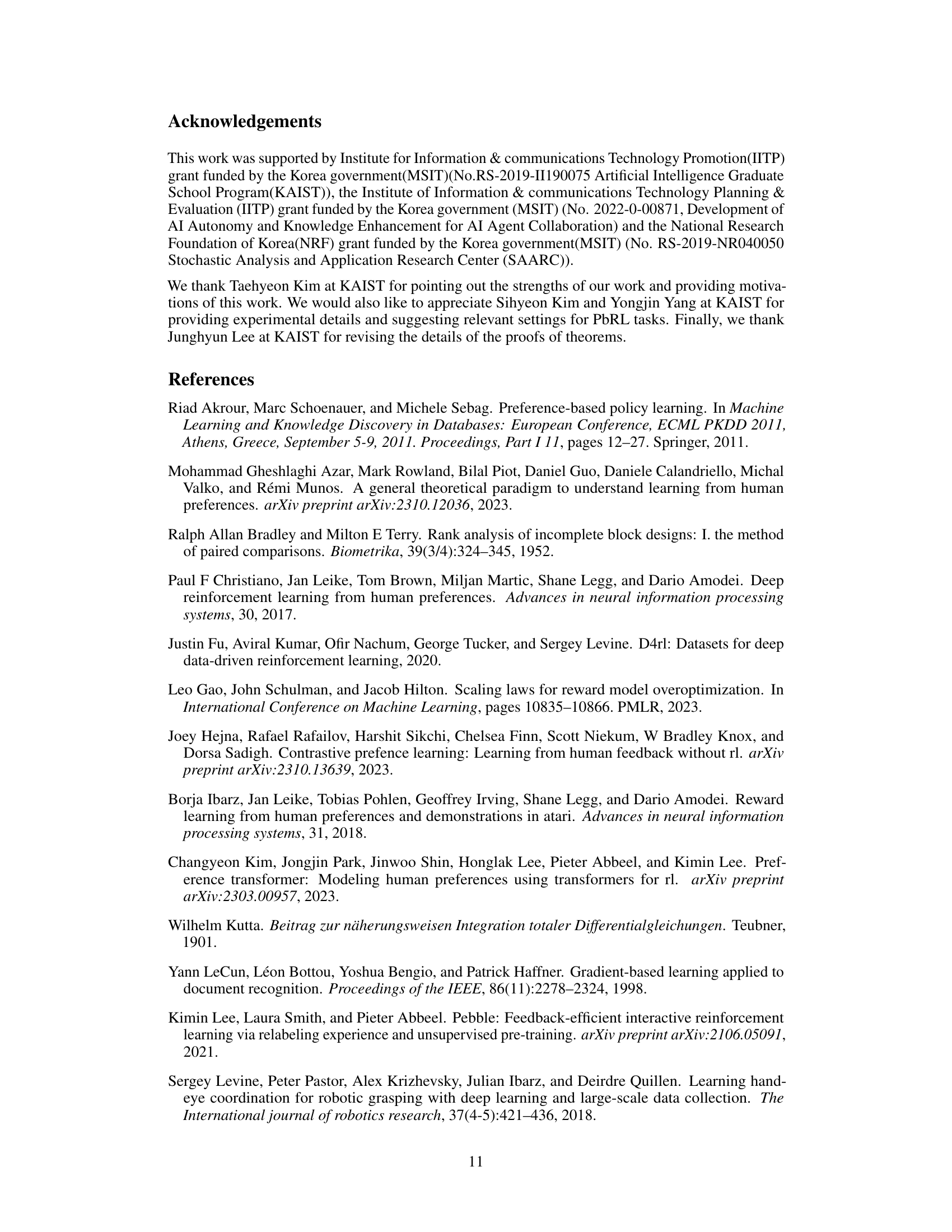

🔼 This table presents the win rates of different methods in a text generation task, as evaluated by GPT-4. The methods include the pre-trained reference model (πref), the reference model with PFM applied once (πref + PFM), the reference model with PFM applied iteratively five times (πref + PFM×5), a fine-tuned policy via PPO (πPPO), the PPO-tuned policy with PFM applied once (πPPO + PFM), and the PPO-tuned policy with PFM applied iteratively five times (πPPO + PFM×5). The win rate represents the percentage of times each model generated a response judged as superior to the response generated by the model it is being compared against by GPT-4. For example, the first row shows that the πref + PFM model generated a better response 100% of the time when compared to the original pre-trained model πref, but only 2% better when compared to the PPO model.

read the caption

Table 2: GPT-4 win rate over 100 test samples.

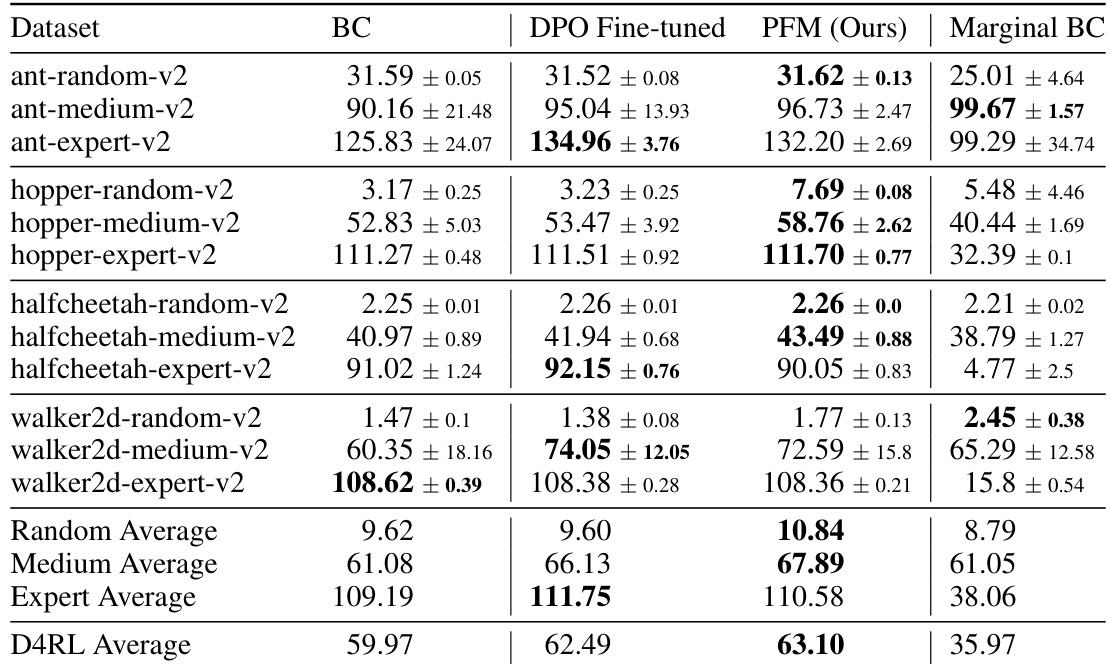

🔼 This table presents the results of the offline reinforcement learning experiments conducted on 12 MuJoCo datasets. The table compares the performance of four different methods: Behavior Cloning (BC), DPO Fine-tuned, PFM (Ours), and Marginal BC. For each dataset and method, the normalized average return and standard deviation across 5 random seeds are provided. The results show how the proposed Preference Flow Matching (PFM) method compares to the baselines, particularly in datasets generated from suboptimal behavioral policies.

read the caption

Table 3: Normalized results on MuJoCo datasets. Mean and standard deviation from 5 seeds are reported.

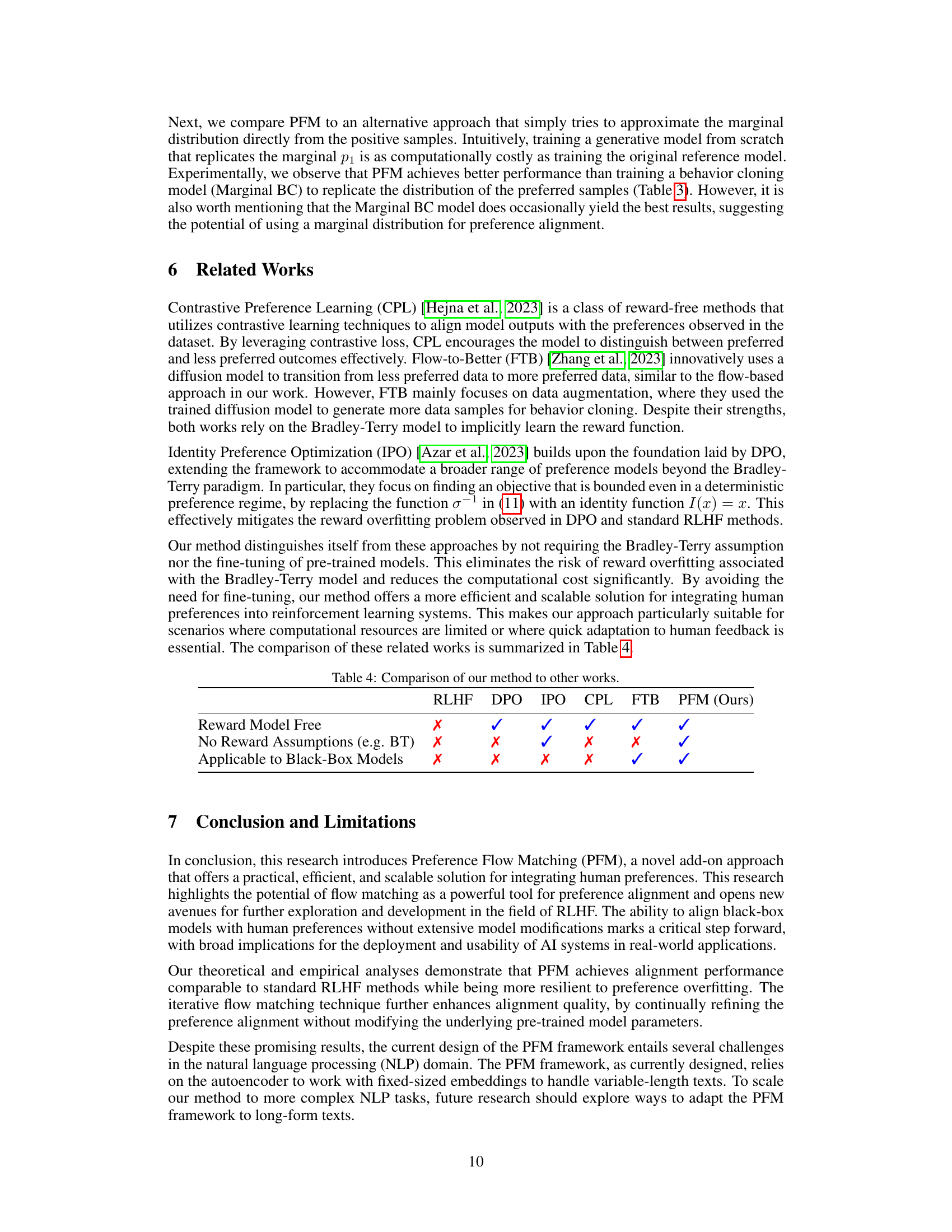

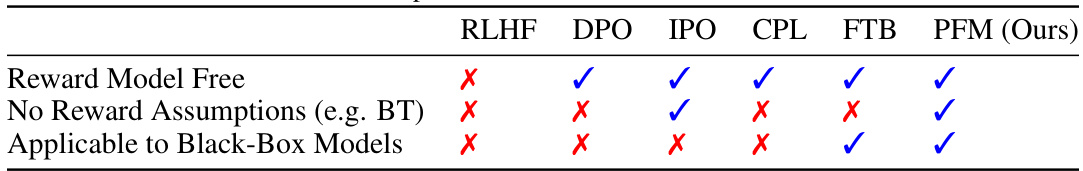

🔼 This table compares the proposed Preference Flow Matching (PFM) method to other existing preference alignment methods, highlighting key differences in terms of reward model reliance, assumptions made (e.g., Bradley-Terry model), and applicability to black-box models. It shows that PFM stands out as the only method that is reward-model free, makes no reward assumptions, and can be directly applied to black-box models.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison of our method to other works.

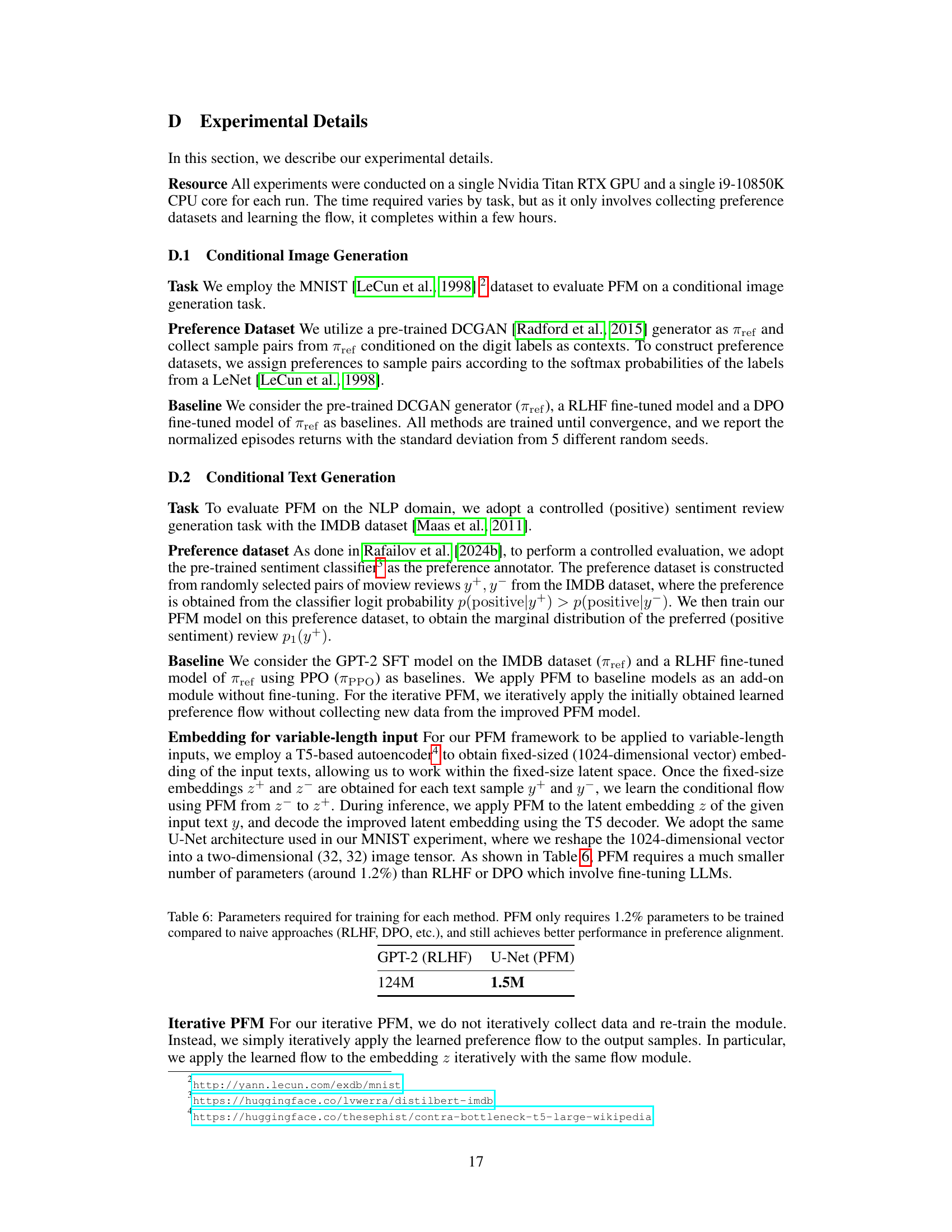

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on three MuJoCo datasets: walker2d-random-v2, walker2d-medium-v2, and walker2d-expert-v2. The methods compared are: Pretrained (BC) - Behavior Cloning as the baseline; PFM from π_ref - Preference Flow Matching using the reference policy as the source; PFM from p_0 - Preference Flow Matching using the true marginal distribution of less preferred data as the source; and Planning - a method that uses the ground truth reward to choose an action sequence. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the normalized scores across 5 different seeds for each method and dataset. The average performance across all datasets is also provided.

read the caption

Table 5: Normalized results on MuJoCo datasets. Mean and standard deviation from 5 seeds are reported.

🔼 This table shows the number of parameters required for training different methods in the conditional text generation experiment. It highlights that Preference Flow Matching (PFM) requires significantly fewer parameters (1.5M) than the Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) method using GPT-2 (124M), demonstrating PFM’s efficiency.

read the caption

Table 6: Parameters required for training for each method. PFM only requires 1.2% parameters to be trained compared to naive approaches (RLHF, DPO, etc.), and still achieves better performance in preference alignment.

Full paper#