TL;DR#

The widespread adoption of fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) has created a huge storage burden on cloud service providers. Existing lossless compression techniques are ineffective for these models because they lack sufficient redundancy. This paper investigates this issue, highlighting the surprisingly small difference between fine-tuned and pre-trained models.

The researchers introduce FM-Delta, a novel lossless compression technique that leverages this similarity. FM-Delta maps model parameters to integers, compresses the differences, and uses entropy coding to achieve significant storage reduction (around 50% on average). It demonstrates high compression and decompression speeds, minimizing any performance penalties. FM-Delta offers a practical solution to address the growing storage costs of fine-tuned LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers dealing with massive fine-tuned foundation models. It addresses the critical issue of storage overhead in cloud platforms, a significant challenge in the rapidly expanding field of large language models. The proposed lossless compression method, FM-Delta, offers a practical and effective solution, with potential applications in various areas of machine learning and cloud computing. This research paves the way for future investigation into more efficient model storage and management techniques.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure shows the growth trend of the total number of models stored on HuggingFace from March 2022 to March 2024. It highlights the increasing number of fine-tuned models compared to pre-trained models. The illustration emphasizes that pre-trained models are fine-tuned to create numerous variants which are then stored in the cloud. This signifies the large storage overhead created by this growing trend, and is the main challenge addressed by the FM-Delta model presented in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 1: Pre-trained models are fine-tuned into thousands of model variants and stored in cloud.

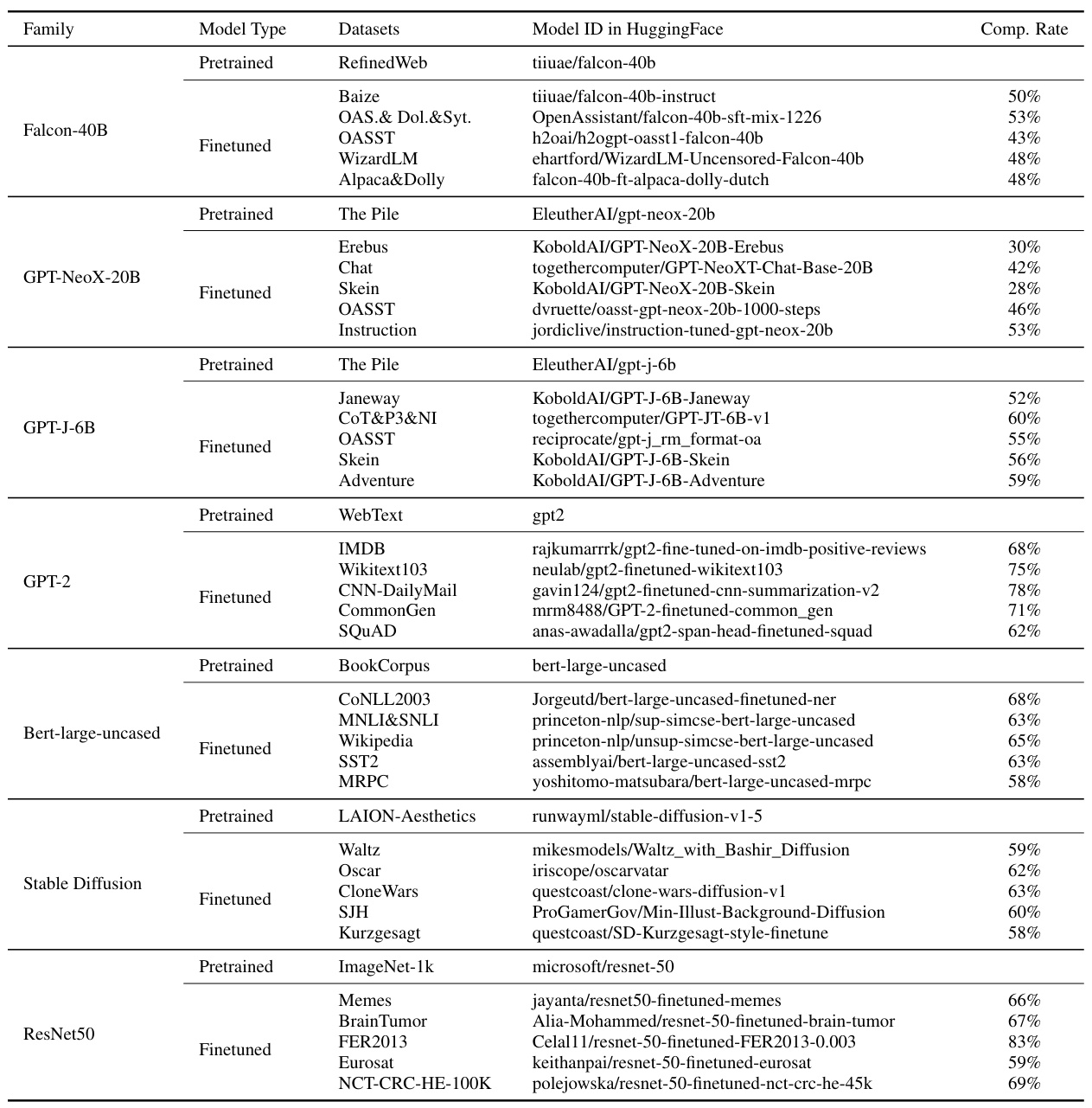

🔼 This table presents the fine-tuning statistics from HuggingFace for six popular model families. It shows the number of full fine-tuned models, the number of parameter-efficient fine-tuned (PEFT) models, the total size of the models, and the percentage of inactive models (those with fewer than 10 monthly downloads). This data highlights the significant storage overhead imposed by full fine-tuned models on cloud platforms.

read the caption

Table 1: Fine-tuning statistical information in HuggingFace for the six most popular models on different tasks. 'Inactive' refers to models with less than 10 monthly downloads.

In-depth insights#

FM-Delta: Overview#

FM-Delta is a novel lossless compression method designed for efficiently storing massive fine-tuned foundation models. Its core innovation lies in exploiting the typically small difference (delta) between a fine-tuned model and its pre-trained counterpart. FM-Delta maps model parameters into integers, enabling entropy coding of the integer delta, resulting in significant storage savings. This approach is particularly effective when numerous fine-tuned models share a common pre-trained base. The method’s lossless nature ensures data integrity, a crucial requirement for cloud storage providers. Empirical results demonstrate significant compression rates and minimal impact on end-to-end performance. Theoretical analysis supports the observed efficiency by showing that the difference between fine-tuned and pre-trained models grows slowly, limiting the size of the delta to be compressed. The FM-Delta algorithm offers a robust solution to the growing challenge of storing and managing massive fine-tuned model variants.

Lossless Compression#

Lossless compression techniques are crucial for efficient storage and transmission of data, especially in domains dealing with massive datasets like those encountered in deep learning. The core concept is to reduce file size without losing any information, enabling perfect reconstruction of the original data. Traditional methods, such as Huffman coding, run-length encoding, and Lempel-Ziv algorithms, while effective for text and image compression, often prove less suitable for compressing the complex numerical data structures typical of deep learning models. The challenge lies in the inherent structure of model parameters, which often lack the redundancy or predictable patterns exploitable by classical lossless techniques. Therefore, novel approaches tailored to the specific characteristics of model data are needed. This often involves exploiting relationships between model components or utilizing advanced entropy coding techniques. FM-Delta represents one such novel approach, demonstrating significant improvement in compression efficiency through its unique integer-based delta encoding scheme. Future research should explore further advancements in lossless compression for deep learning models, considering both hardware acceleration and the development of more specialized algorithms that efficiently exploit the properties of specific model architectures and training methodologies.

Empirical Analysis#

An Empirical Analysis section in a research paper would typically present data-driven evidence supporting the study’s claims. It should go beyond simply reporting results; a strong analysis would involve comparing results across different conditions or groups, examining trends and patterns, and using statistical tests to determine the significance of findings. Visualizations, such as graphs and charts, would be crucial for effectively communicating complex data. The analysis should also address potential limitations or confounding factors, acknowledging any inconsistencies or unexpected results. A robust Empirical Analysis section would be vital in convincing readers of a study’s validity and significance. Statistical measures of significance should be clearly stated. The discussion should connect the empirical findings back to the paper’s central hypothesis or research question, explaining how the results support or challenge the study’s core arguments. Furthermore, the authors should explain what the results mean in the context of previous research and suggest potential directions for future investigation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending FM-Delta’s applicability to various model architectures and tasks. Investigating lossless compression techniques for models beyond the full fine-tuned variety (e.g., parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods) is crucial. Further work should focus on optimizing FM-Delta’s compression and decompression speeds, potentially through hardware acceleration or improved algorithmic efficiency. A key area for future work involves thorough investigation into the impact of various data distributions on delta compression performance, as this factor can significantly affect compression ratio. Finally, developing robust methods for handling dynamically changing model parameters during training or inference would enhance FM-Delta’s practical utility, making it suitable for real-time applications and cloud environments.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the ‘Limitations’ section of a research paper necessitates a multifaceted approach. It’s crucial to evaluate whether the authors have honestly and thoroughly addressed the shortcomings of their methodology, data, and scope. Overly optimistic assessments or the omission of significant limitations significantly weaken the paper’s credibility. A strong limitations section will not only highlight weaknesses but also provide context on how these limitations might affect the broader implications of the research. Acknowledging the boundaries of generalizability is paramount; limitations should transparently explain the contexts in which the results might not hold. A nuanced discussion of the challenges encountered during the research process and their potential impact on future studies also contributes to a robust evaluation. Ultimately, a well-written ‘Limitations’ section displays intellectual honesty and strengthens the overall scientific rigor of the work. It demonstrates a commitment to responsible research and provides a valuable roadmap for future investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

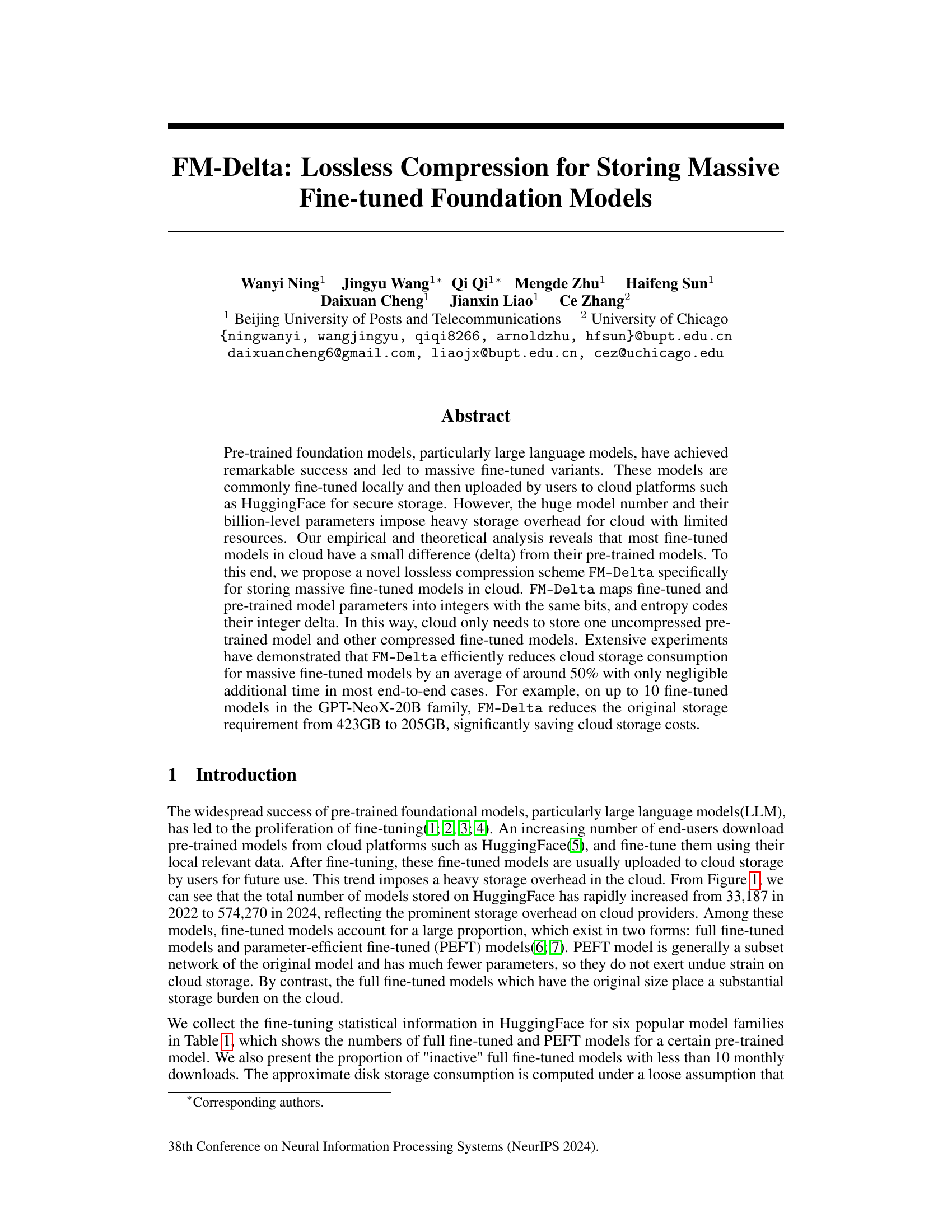

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between fine-tuned and pre-trained models for four model families (Stable Diffusion, GPT2, Bert-large, ResNet50), the distribution of the weight difference between them for four other models (Pokemon Stable Diffusion, Wikitext103 GPT2, SST2 BERT, FER2013 ResNet50), and the residual matrix of different layers on Wikitext103 GPT2. The results indicate high similarity between fine-tuned and pre-trained models.

read the caption

Figure 2: Difference information between the fine-tuned and pre-trained models.

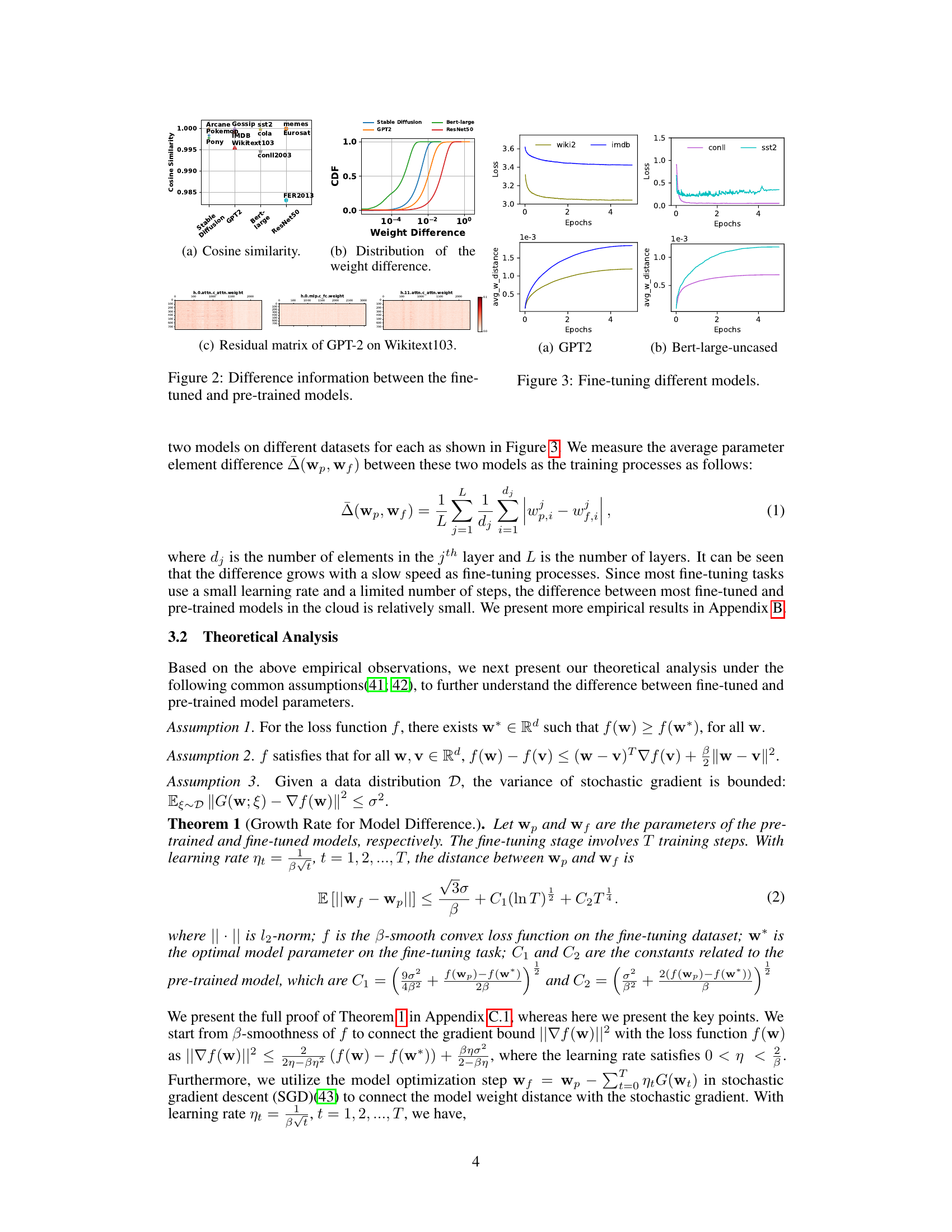

🔼 This figure visualizes the fine-tuning process for four different model families: Stable Diffusion, GPT2, Bert-large-uncased, and ResNet50. For each model family, it presents four sub-figures: (a) Cosine Similarity, (b) Distribution of the Weight Difference, (c) Residual Matrix of GPT-2 on Wikitext103, (d) Fine-tuning different models. These sub-figures show various metrics like cosine similarity between fine-tuned and pre-trained models, distribution of weight differences, and the residual matrix of the model’s weight parameters across epochs. The plots provide insights into how the changes in the model’s weights evolve during the fine-tuning process.

read the caption

Figure 9: Fine-tuning results on different models.

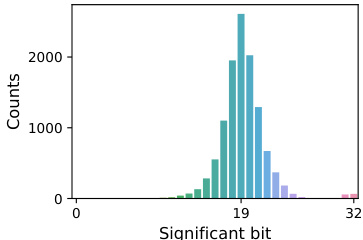

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the most significant bit (MSB) in the difference between the integer representations of the parameters of a fine-tuned model and its corresponding pre-trained model, specifically focusing on the first convolutional layer. The x-axis represents the MSB position (0-32), and the y-axis shows the count of parameters with that MSB position. The distribution is heavily skewed towards lower MSB values, indicating that a significant portion of the parameter differences have many leading zeros. This observation directly supports the effectiveness of the FM-Delta compression method, which leverages this bit redundancy by entropy coding the integer delta.

read the caption

Figure 4: Most significant bit distribution of the first convolutional-layer delta.

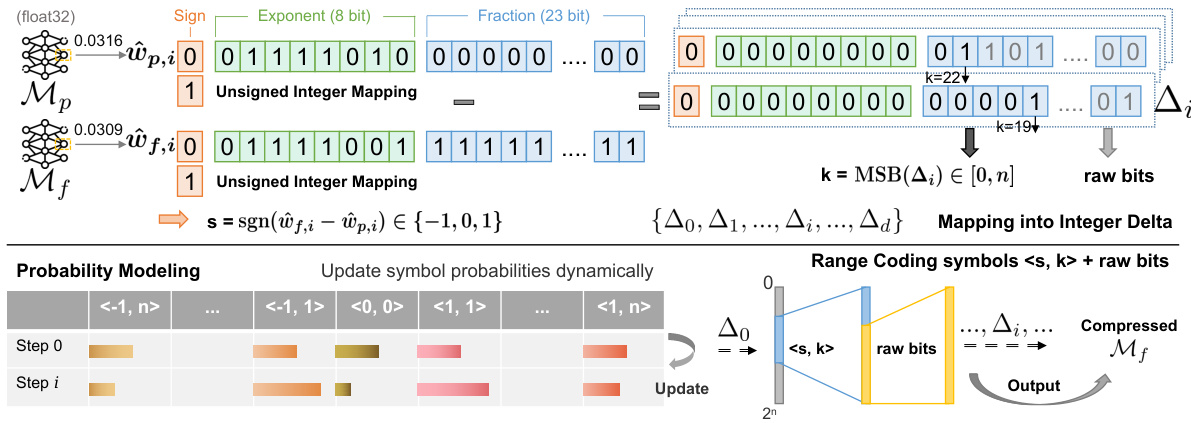

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the FM-Delta lossless compression algorithm. It starts by mapping the floating-point parameters of fine-tuned and pre-trained models into unsigned integers. Subtraction then yields a bit-redundant delta. The algorithm then uses range coding to compress the delta further. The sign and most significant bit of the delta are treated as symbols and encoded using a quasi-static probability model. Finally, the encoded symbols are combined with the remaining raw bits to form the compressed fine-tuned model.

read the caption

Figure 5: The lossless compression workflow of FM-Delta. The FM-Delta scheme (1) maps the two floating-point parameter elements at the same position of fine-tuned and pre-trained models into unsigned integers, and performs integer subtraction to obtain the bit-redundant delta element. Then it (2) regards the sign s and the most significant bit k of delta as symbols. With a quasi-static probability modeler, it encodes the symbols and scales the range to involve raw bits on all delta elements, leading to the compressed fine-tuned model.

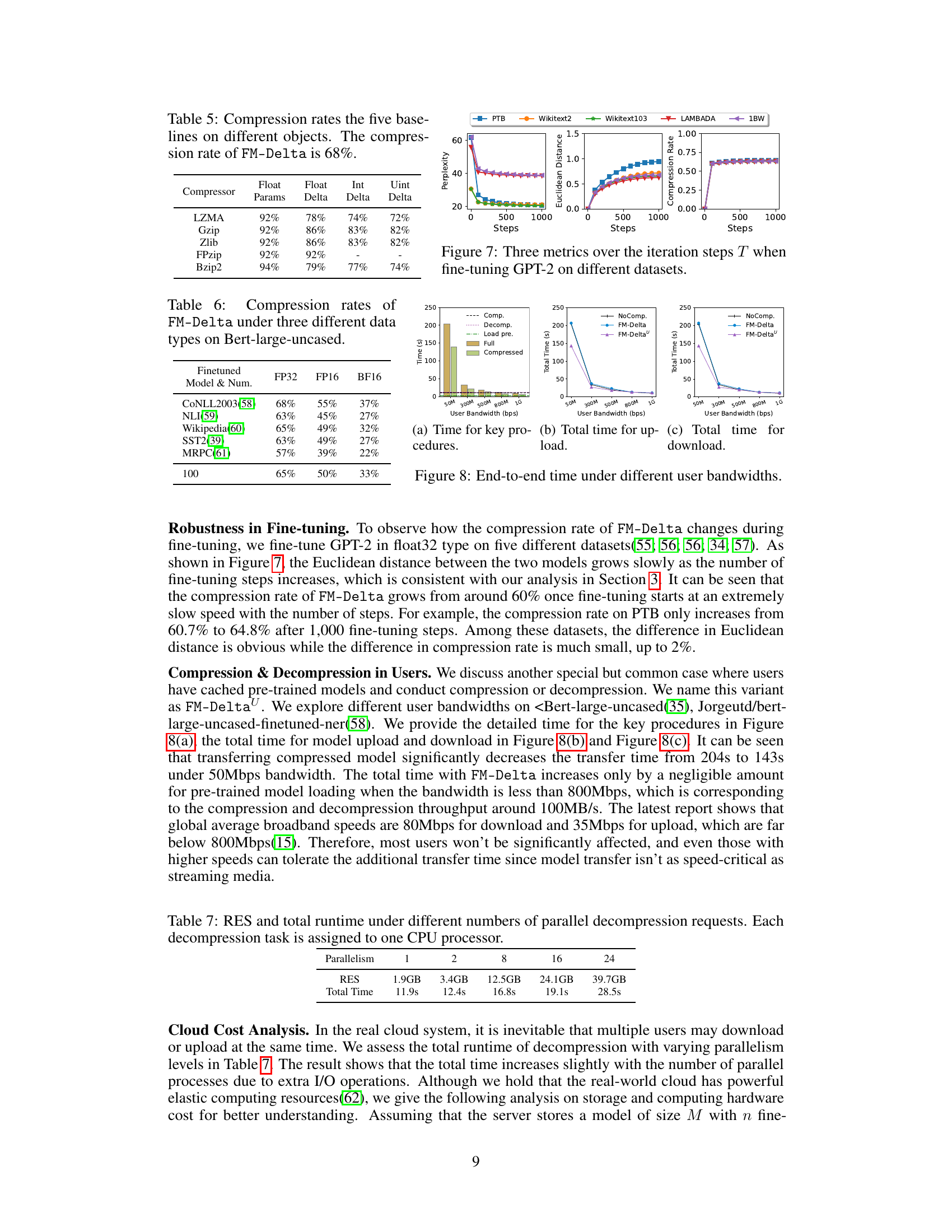

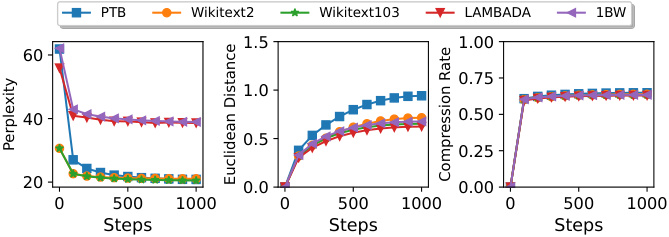

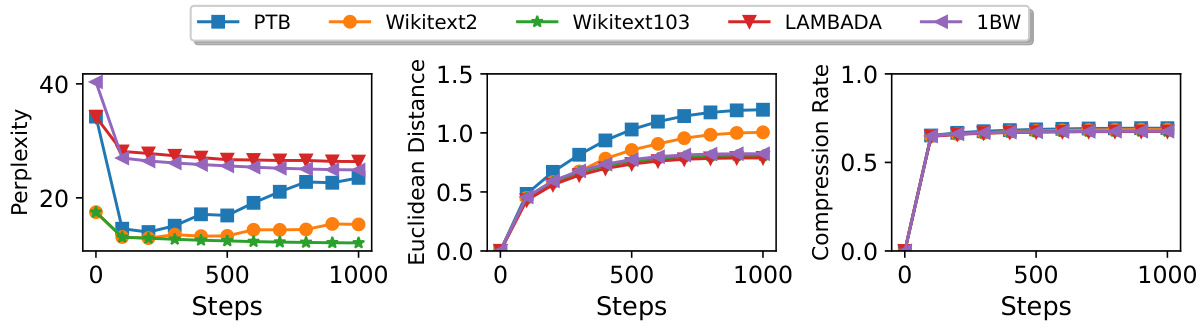

🔼 This figure shows how three metrics (perplexity, Euclidean distance, and compression rate) change as the number of fine-tuning steps (T) increases during the fine-tuning of GPT-2 on five different datasets. The results illustrate how the model’s performance, its difference from the pre-trained model, and the effectiveness of the compression method evolve during the training process.

read the caption

Figure 7: Three metrics over the iteration steps T when fine-tuning GPT-2 on different datasets.

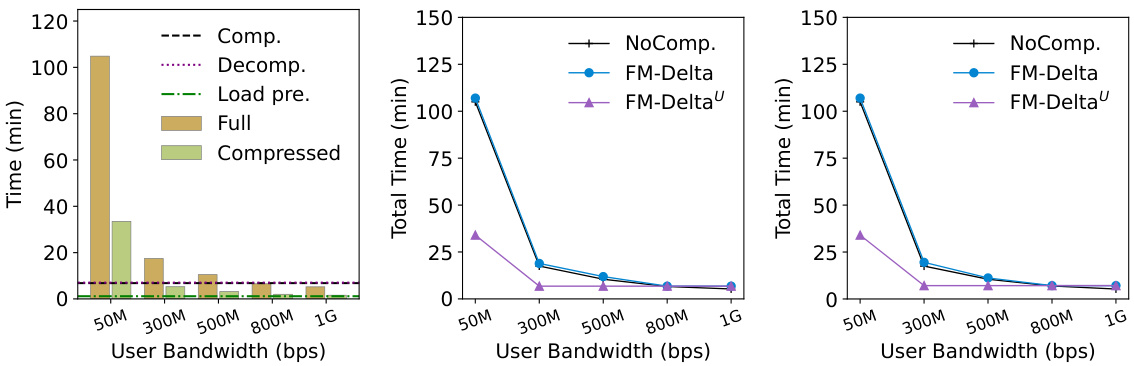

🔼 This figure shows the total time taken for model upload and download under various user bandwidths for the GPT-NeoX-20B model. The three sub-figures break down the timings: (a) Time for key procedures (loading the pre-trained model, compression, decompression and transfer); (b) Total time for upload; (c) Total time for download. It demonstrates that FM-Delta achieves similar total times to the non-compressed method when bandwidth is below 800Mbps, and significantly faster download/upload times at higher bandwidths.

read the caption

Figure 13: End-to-end time under different user bandwidths on GPT-NeoX-20B.

🔼 This figure presents the results of fine-tuning four different models (Stable Diffusion, GPT2, Bert-large-uncased, and ResNet50) on various datasets. Each subfigure shows the loss and the average parameter element difference (avg_w_distance) between the fine-tuned and pre-trained models over the training epochs. The plots illustrate how the difference between the fine-tuned and pre-trained models changes during the fine-tuning process, providing empirical evidence supporting the paper’s claim that this difference grows slowly with the number of fine-tuning steps. This slow growth is a key finding that motivates their proposed lossless compression method.

read the caption

Figure 9: Fine-tuning results on different models.

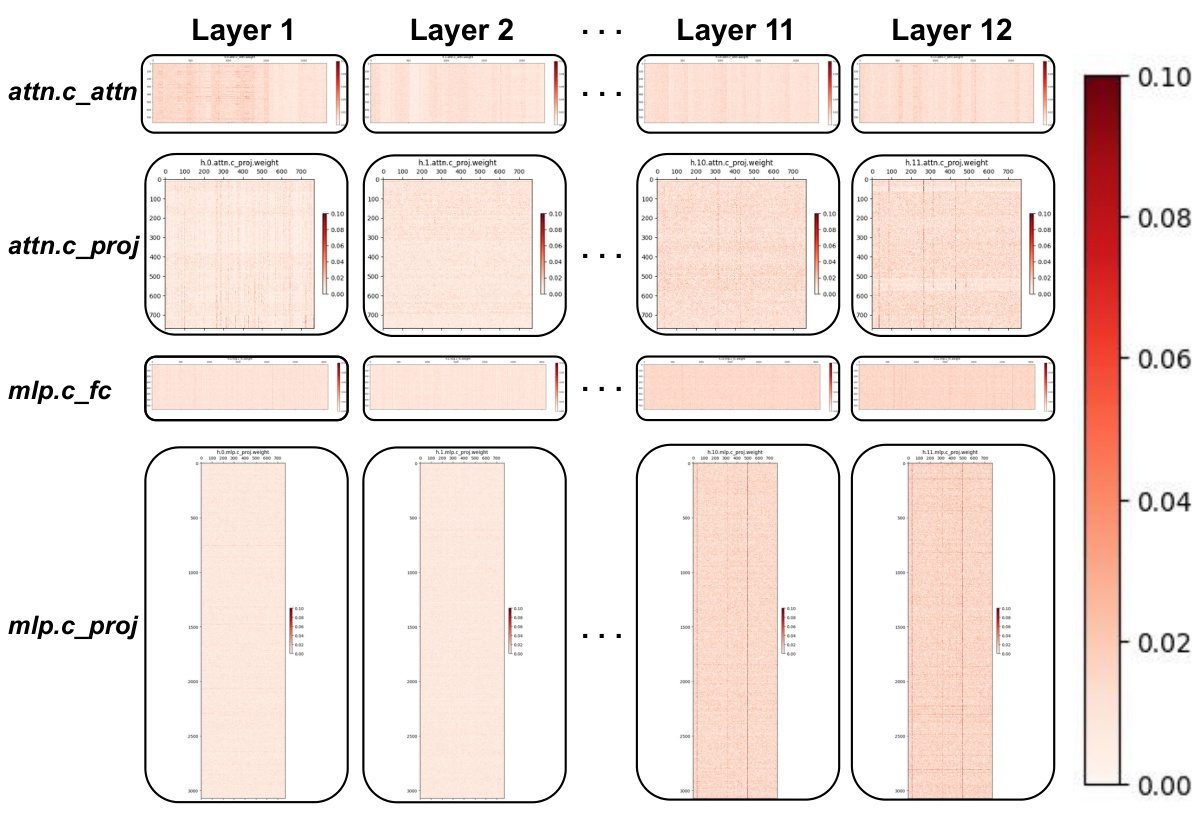

🔼 This figure shows a heatmap visualization of the residual matrix for different layers of the GPT-2 model trained on the Wikitext103 dataset. The heatmap displays the element-wise difference between the fine-tuned and pre-trained model parameters for each layer. Each cell’s color intensity represents the magnitude of the difference, with darker colors indicating larger differences. This visualization helps to understand the distribution of changes in model parameters after fine-tuning, supporting the paper’s claim that the difference between fine-tuned and pre-trained models is relatively small.

read the caption

Figure 10: Residual matrix of GPT-2 on Wikitext103.

🔼 This figure visualizes the compression rates achieved by the FM-Delta algorithm across different layers of various neural network models. The three subfigures show the compression rates for different model types: (a) UNet of Stable Diffusion, (b) Transformer layers of GPT2, and (c) sublayers within a transformer. Each subfigure plots the compression rate against the layer number, revealing how the effectiveness of the compression technique varies across the layers of a network architecture. The patterns observed offer insights into the characteristics of different model layers and the suitability of FM-Delta for compressing them.

read the caption

Figure 11: Compression rates of FM-Delta on different model layers.

🔼 This figure shows the perplexity, Euclidean distance, and compression rate during the fine-tuning process of GPT-2-1.5B on five different datasets (PTB, Wikitext2, Wikitext103, LAMBADA, and 1BW). The x-axis represents the number of fine-tuning steps (T), while the y-axis shows the corresponding metric values for each dataset. The figure illustrates how these metrics change as the model is fine-tuned on different datasets, highlighting the relationship between the number of fine-tuning steps and model performance and compression characteristics. It helps to visualize the model’s learning progress and the effectiveness of the FM-Delta compression method across various datasets.

read the caption

Figure 12: Three metrics over the iteration steps T when fine-tuning GPT-2-1.5B on different datasets.

🔼 The figure shows the detailed time for model upload and download under different user bandwidths on <EleutherAI/gpt-neox-20b, KoboldAI/GPT-NeoX-20B-Erebus>. When the user’s bandwidth is below approximately 800Mbps, the total time is nearly equivalent to that of the non-compression solution for FM-Delta, and it is significantly reduced for FM-Deltau due to the decreased data transfer volume. When the user’s bandwidth exceeds around 800Mbps, the total time is limited by the compression throughput due to the transmission speed being faster than the compression speed (approximately 100MB/s).

read the caption

Figure 13: End-to-end time under different user bandwidths on GPT-NeoX-20B.

More on tables

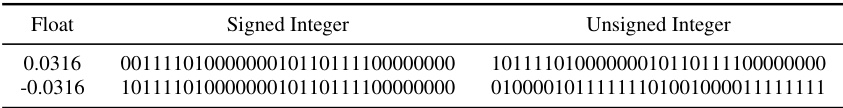

🔼 This table compares the values of a specific element from the pre-trained and fine-tuned models. It shows the original floating-point values, their integer representations, and the difference between those integer representations. The key observation is that the integer difference has many leading zeros (redundant ‘0’ bits), which motivates the compression scheme in the paper.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of a certain element value in the ith position of the pre-trained model (wp) and the fine-tuned model (wf) respectively. The delta of the two original element bytes contains a large number of redundant '0' bits.

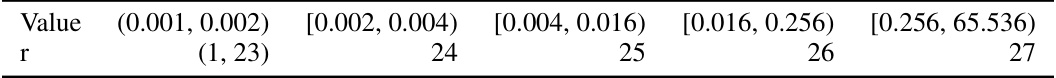

🔼 This table shows the most significant bit position (r) of the integer delta for different ranges of tuned values, given a base value of 0.001. The most significant bit position is a key component in the FM-Delta compression algorithm, indicating the number of leading zeros in the difference between the fine-tuned and pre-trained model parameters. The table helps illustrate the relationship between the magnitude of the difference and the bit redundancy that FM-Delta leverages for compression. This relationship is crucial for the algorithm’s efficiency and robustness across a range of fine-tuning scenarios.

read the caption

Table 3: Given a base value 0.001, the most significant bit position r of the integer delta, corresponding to the range intervals of different tuned values.

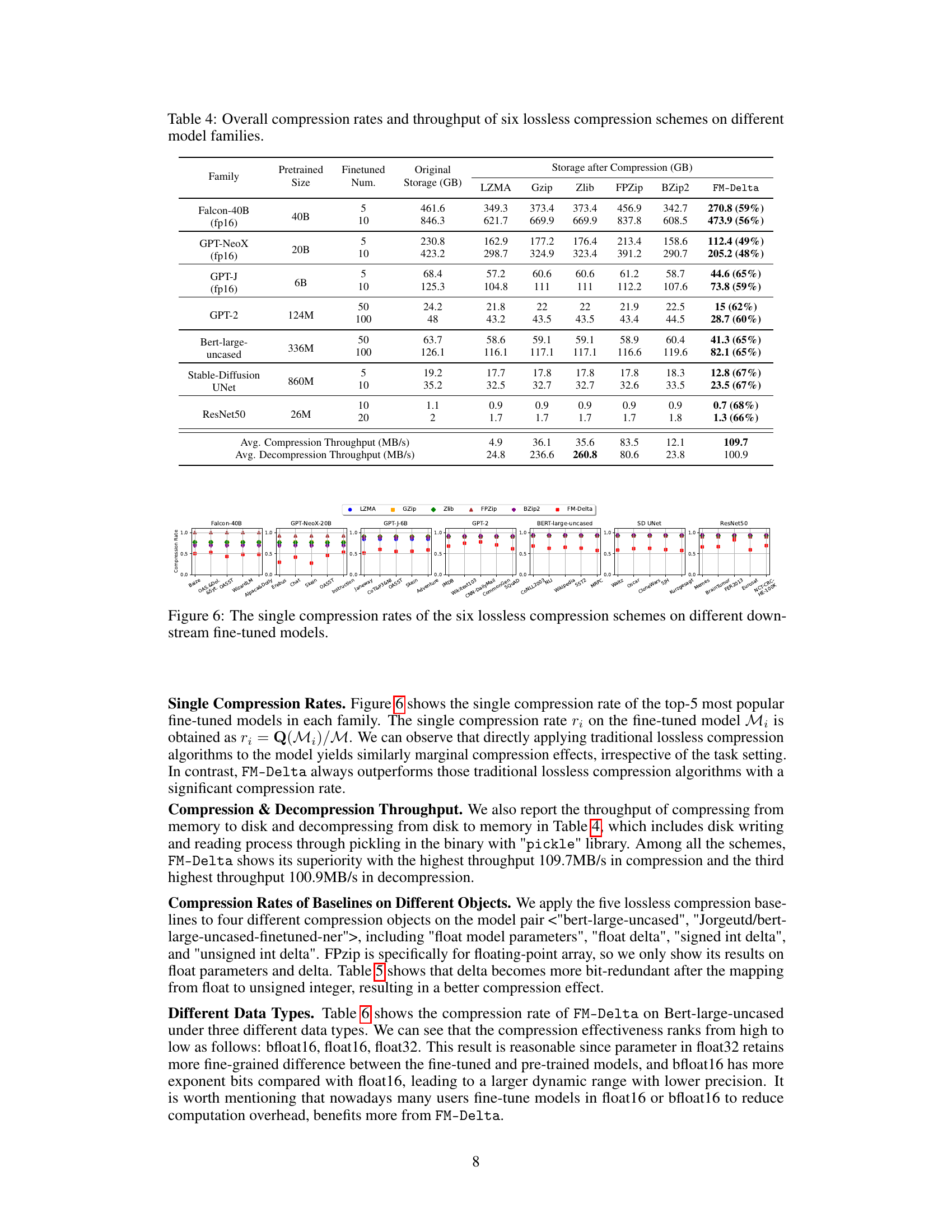

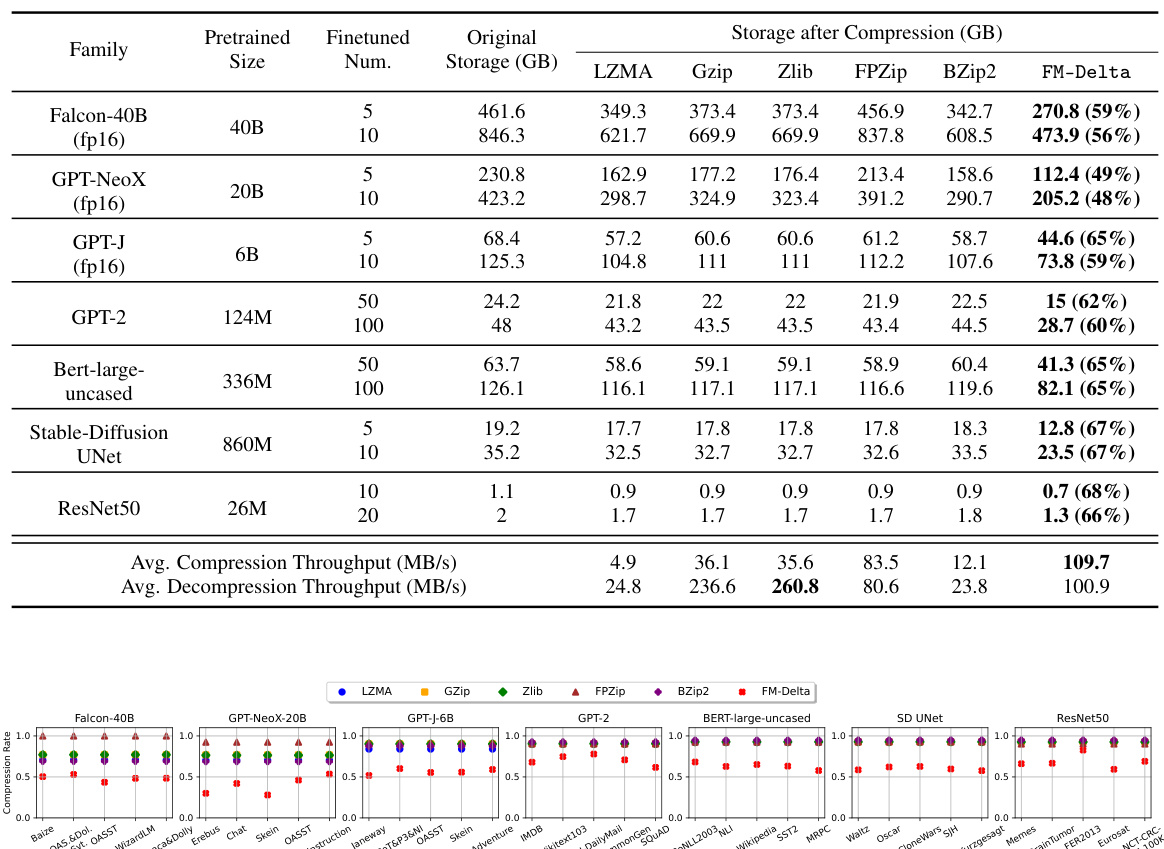

🔼 This table presents a comparison of six lossless compression algorithms (LZMA, Gzip, Zlib, FPZip, BZip2, and FM-Delta) applied to seven different pre-trained model families with varying numbers of fine-tuned models. For each model family and number of fine-tuned models, it shows the original storage size in GB, the storage size after compression using each algorithm in GB, and the compression and decompression throughputs (in MB/s) achieved by each algorithm. The table highlights FM-Delta’s superior compression rates compared to the other algorithms, offering significant storage savings with good compression and decompression speed.

read the caption

Table 4: Overall compression rates and throughput of six lossless compression schemes on different model families.

🔼 This table presents the compression rate achieved by five different baseline compression methods (LZMA, Gzip, Zlib, FPzip, and Bzip2) when applied to different data representations of fine-tuned and pre-trained model parameters. The data representations include float parameters, float delta (difference between fine-tuned and pre-trained), integer delta, and unsigned integer delta. The table highlights that FM-Delta achieves a 68% compression rate on unsigned integer delta.

read the caption

Table 5: Compression rates the five baselines on different objects. The compression rate of FM-Delta is 68%.

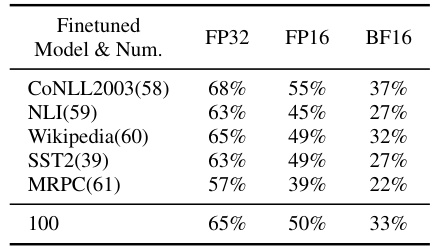

🔼 This table presents the compression rates achieved by the FM-Delta algorithm when applied to the Bert-large-uncased model using three different data types: FP32, FP16, and BF16. The results show how the compression rate varies depending on the precision of the floating-point numbers used to represent the model parameters. Lower precision generally leads to higher compression rates because there is less information to represent in the smaller number of bits.

read the caption

Table 6: Compression rates of FM-Delta under three different data types on Bert-large-uncased.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of six lossless compression algorithms (LZMA, Gzip, Zlib, FPZip, BZip2, and FM-Delta) applied to seven different model families with varying numbers of fine-tuned models. For each model family and number of fine-tuned models, the table shows the original storage size, and the storage size after compression using each algorithm. It also provides the average compression and decompression throughput in MB/s for each algorithm. This allows for a comprehensive comparison of the performance of different compression techniques in reducing storage space and maintaining reasonable compression and decompression speeds for massive fine-tuned models.

read the caption

Table 4: Overall compression rates and throughput of six lossless compression schemes on different model families.

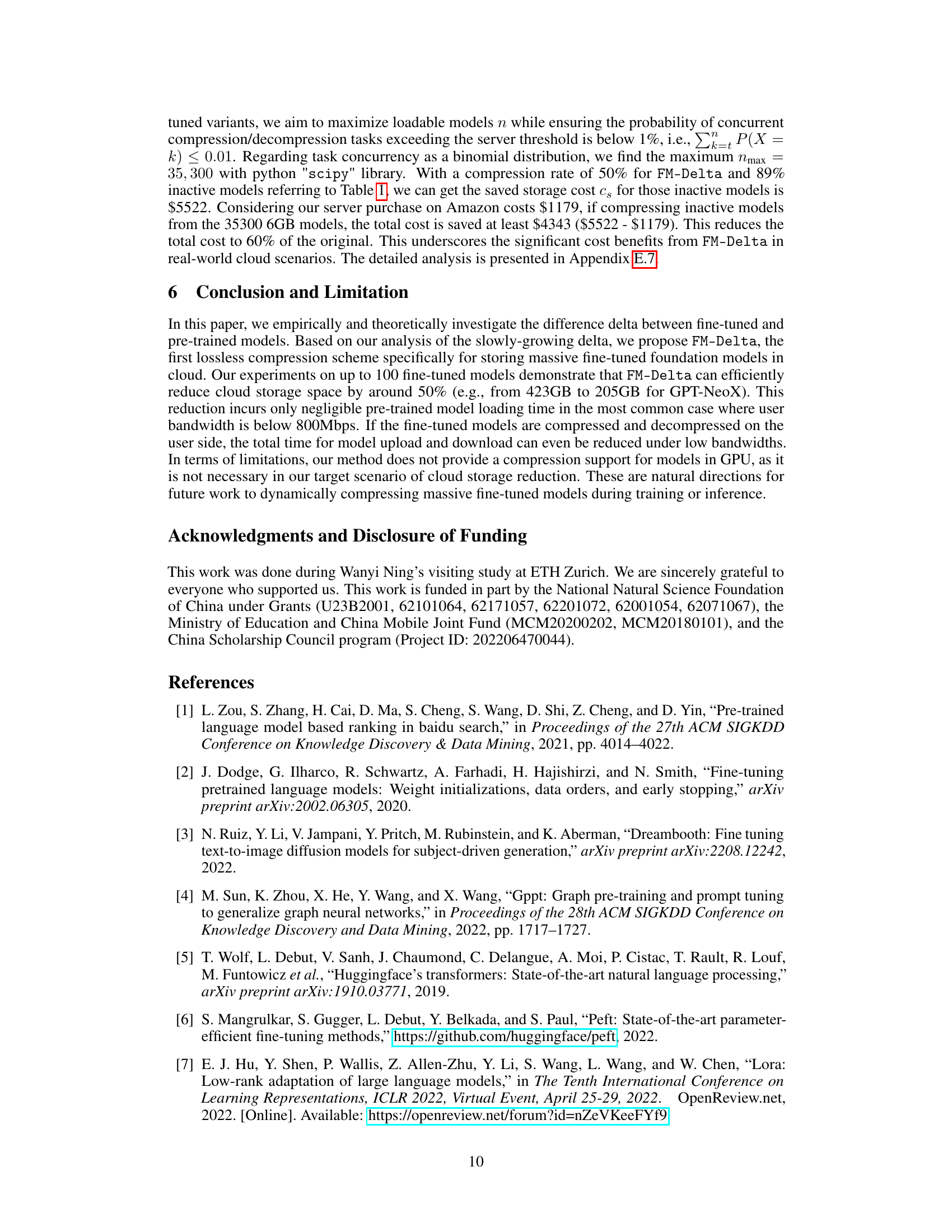

🔼 This table presents statistics on ten different large language models, showing the counts of fully fine-tuned models and parameter-efficient fine-tuned (PEFT) models for each. The ‘Proportion of Full’ column indicates the percentage of models in each family that are fully fine-tuned, providing insights into the prevalence of fully fine-tuned models compared to PEFT models across different model architectures.

read the caption

Table 8: The number of full fine-tuned and PEFT models in the ten additional model families, along with the proportion of full models on these families.

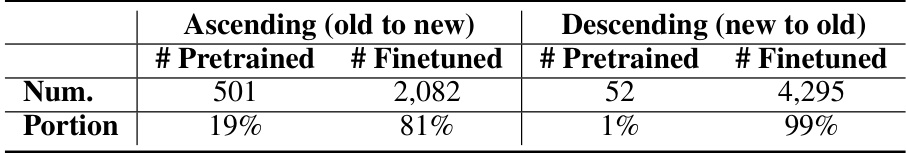

🔼 This table shows the proportion of pre-trained and fine-tuned models among 10,000 models from HuggingFace. The data is divided into two sets: ascending (oldest to newest) and descending (newest to oldest) order to show the trend in model uploads. The results indicate a significant increase in the number of fine-tuned models over time.

read the caption

Table 9: The portion of pre-trained and fine-tuned models in the 10,000 models from HuggingFace, counted in ascending and descending order.

🔼 This table compares the values of a specific element (at the ith position) in both the pre-trained and fine-tuned models. It shows the original float values, their integer representations, and the resulting delta. The key observation is the presence of many redundant zeros in the integer delta, highlighting the potential for compression.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of a certain element value in the ith position of the pre-trained model (wp) and the fine-tuned model (wf) respectively. The delta of the two original element bytes contains a large number of redundant '0' bits.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the compression performance of six different lossless compression algorithms (LZMA, Gzip, Zlib, FPZip, BZip2, and FM-Delta) on seven distinct model families. For each model family, the table shows the original storage size, the number of fine-tuned models, and the compressed storage size achieved by each algorithm. Additionally, the average compression and decompression throughput (in MB/s) for each algorithm is provided. The table highlights the significant storage reduction achieved by FM-Delta compared to traditional methods, especially with a larger number of fine-tuned models.

read the caption

Table 4: Overall compression rates and throughput of six lossless compression schemes on different model families.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of six lossless compression algorithms (LZMA, Gzip, Zlib, FPZip, BZip2, and FM-Delta) on seven different pre-trained model families (Falcon-40B, GPT-NeoX-20B, GPT-J-6B, GPT-2-124M, Bert-large-uncased-336M, Stable-Diffusion-860M, ResNet50-26M). For each model family, it shows the original storage size, the number of fine-tuned models used in the experiment, and the storage size after compression using each algorithm. It also shows the average compression and decompression throughput (in MB/s) for each algorithm. This table highlights the superior compression rate of FM-Delta compared to traditional lossless compression methods for fine-tuned language models.

read the caption

Table 4: Overall compression rates and throughput of six lossless compression schemes on different model families.

🔼 This table presents the fine-tuning statistics from HuggingFace for six popular models. It shows the number of full fine-tuned models and parameter-efficient fine-tuned (PEFT) models for each pre-trained model. The table also indicates the proportion of ‘inactive’ models (those with fewer than 10 monthly downloads), highlighting the significant storage overhead caused by inactive, full fine-tuned models. The table is used to demonstrate the problem FM-Delta seeks to solve, namely the inefficiency of storing numerous, full fine-tuned models that are rarely accessed in the cloud.

read the caption

Table 1: Fine-tuning statistical information in HuggingFace for the six most popular models on different tasks. 'Inactive' refers to models with less than 10 monthly downloads.

Full paper#