↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Surface parameterization is vital for various computer graphics applications, but existing methods often struggle with complex 3D data and require manual intervention. This necessitates the development of robust automated methods for handling irregular and complex data, especially considering the current explosion of ordinary 3D data from different sources. This is a challenge because traditional methods often rely on laborious manual processes and are restricted to simple topologies.

The paper introduces the Flatten Anything Model (FAM), an unsupervised neural network architecture for global free-boundary surface parameterization. Unlike traditional methods, FAM operates directly on discrete surface points, eliminating the need for pre-processing and mesh quality constraints. It ingeniously uses a bi-directional cycle mapping framework, incorporating sub-networks for surface cutting, UV deforming, unwrapping, and wrapping to mimic the physical parameterization process. FAM demonstrates superior performance compared to existing methods across various datasets, proving its universality and efficiency in handling complex topologies. This fully automated approach significantly improves the efficiency and robustness of surface parameterization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents FAM, a novel fully automated and unsupervised neural surface parameterization model. This addresses the limitations of traditional methods that struggle with complex topologies and require manual pre-processing. It opens avenues for research on neural surface parameterization for unstructured point cloud data, which is crucial for various applications dealing with real-world 3D data. The introduction of a bi-directional cycle mapping framework offers a new approach for parameterization, making the results highly valuable to the computer graphics and geometry processing community. The method’s robustness and superior performance over existing methods are highly significant for researchers in the field.

Visual Insights#

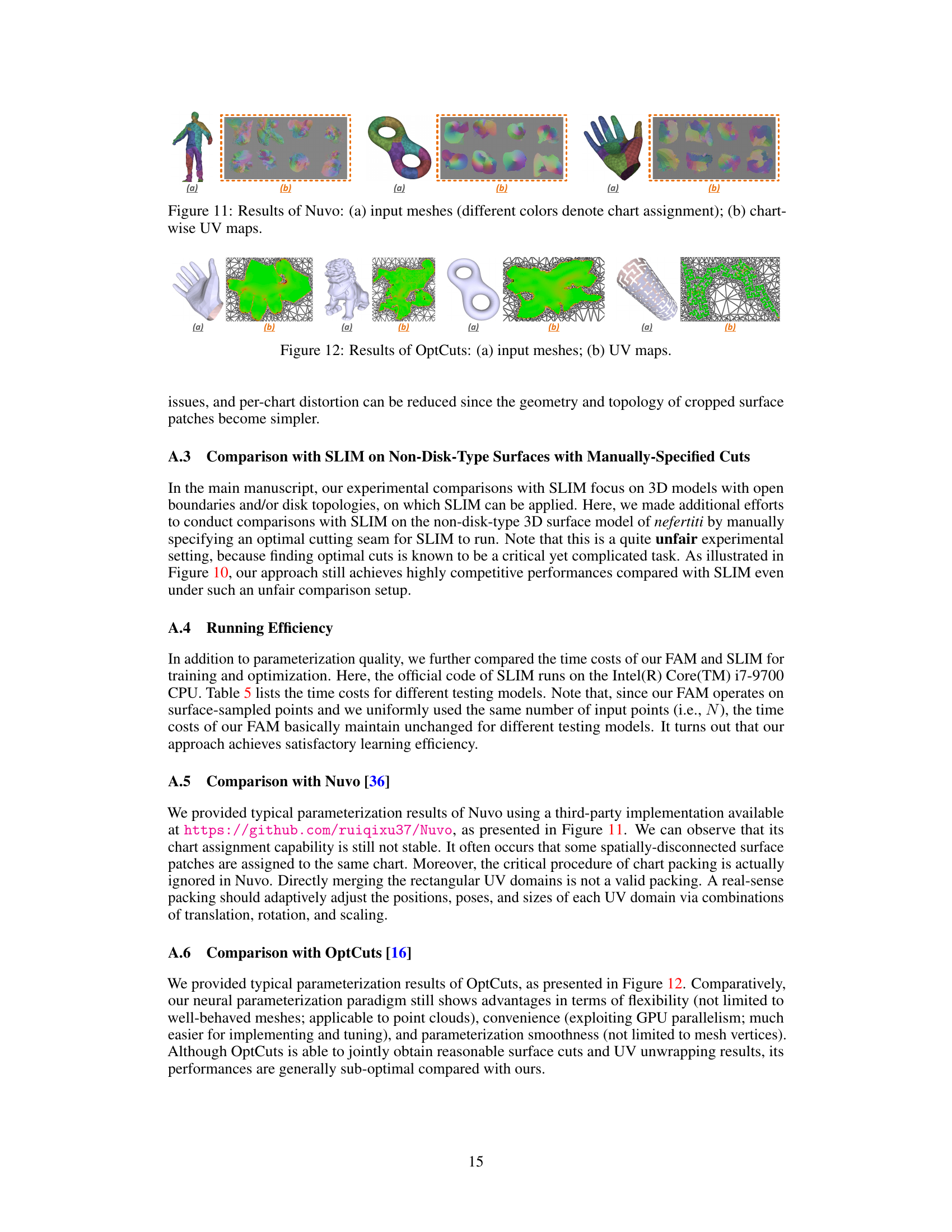

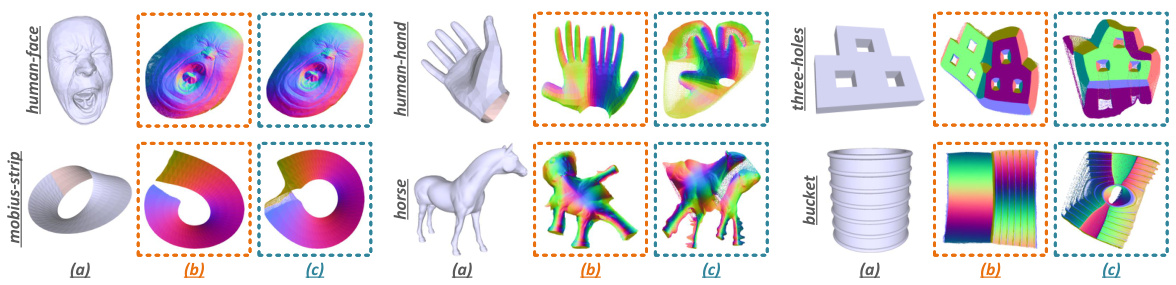

This figure shows examples of the Flatten Anything Model (FAM) applied to various 3D models. It demonstrates the model’s ability to generate UV coordinates, texture mappings, and cutting seams for different types of 3D models, including disk-type, genus-0, genus-1, and complex topologies. It also shows the results for real-scanned objects, real-scanned scenes, and 3D AIGC models, demonstrating the model’s versatility in handling diverse input data.

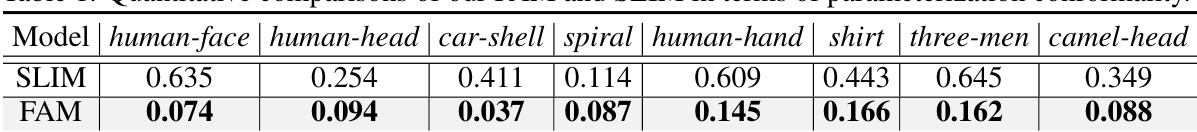

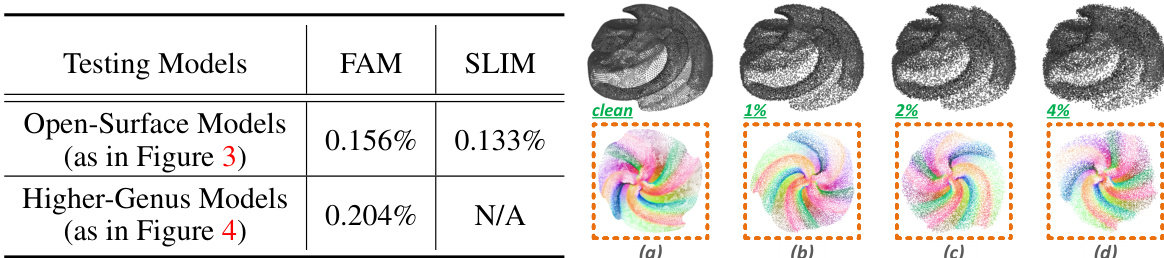

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed Flatten Anything Model (FAM) and the state-of-the-art method SLIM in terms of parameterization conformality. Conformality measures how well angles are preserved during the mapping from 3D to 2D. Lower values indicate better conformality. The table shows that FAM significantly outperforms SLIM across various models.

In-depth insights#

Neural Parameterization#

The section on “Neural Parameterization” would delve into the application of neural networks to the complex problem of surface parameterization. It would likely discuss how these methods overcome limitations of traditional approaches, such as their inability to handle complex topologies or unstructured data. Key advantages of neural methods, such as the ability to learn global mappings and automatically determine optimal cutting seams, would be highlighted. The discussion would probably cover prominent neural parameterization architectures, comparing their strengths and weaknesses. Specific network architectures might be analyzed, along with the loss functions and training strategies used. The analysis would also likely address the trade-offs between accuracy, efficiency, and generalization capability. Finally, the section would probably compare and contrast neural approaches with traditional methods, identifying specific scenarios where neural parameterization excels. This would lead to a discussion about the future potential of neural parameterization in handling increasingly complex 3D data and the potential for further innovation in this space.

FAM Architecture#

The FAM (Flatten Anything Model) architecture is a bi-directional cycle mapping framework designed for unsupervised neural surface parameterization. It cleverly mimics the physical process of flattening a 3D surface by ingeniously incorporating four key sub-networks: Deform-Net, Wrap-Net, Cut-Net, and Unwrap-Net. These sub-networks are not independent; they are interconnected and jointly optimized, creating a feedback loop that refines the parameterization. The Deform-Net deforms a 2D lattice, Wrap-Net maps this to the 3D surface, Cut-Net identifies optimal cutting seams, and Unwrap-Net flattens the modified 3D surface onto a 2D parameter domain. This cyclical process allows the model to learn both the optimal cutting strategy and the most suitable 2D mapping, significantly enhancing accuracy and handling complex topologies. The architecture’s strength lies in its point-wise operation, avoiding the constraints of mesh connectivity, and its ability to directly learn cutting seams, dispensing with manual pre-processing. The use of MLPs within each sub-network and the overall cycle mapping framework suggests that FAM is both efficient and effective for creating high-quality parameterizations.

Bi-directional Mapping#

The concept of “Bi-directional Cycle Mapping” in the context of neural surface parameterization presents a powerful approach to overcome limitations of traditional methods. It leverages a cyclical learning framework, where two interconnected pathways, 2D-to-3D and 3D-to-2D, simultaneously refine the mapping between the 3D surface and its 2D parameterization. The 2D-to-3D pathway involves deforming a 2D lattice, wrapping it onto the 3D surface, and cutting seams to create a developable surface. The 3D-to-2D pathway unwraps this modified 3D surface back to a 2D representation. This iterative process, enabled by shared network parameters between the stages, allows for mutual adaptation and optimization. The inherent consistency constraints, imposed by the cyclic nature, help to guarantee a more accurate and robust parameterization, ultimately resolving potential conflicts and inaccuracies that might arise from a strictly unidirectional approach. The geometric interpretability of the sub-networks (deformation, wrapping, cutting, unwrapping) enhances the learning process by mimicking the physical actions involved, leading to improved performance and a deeper understanding of the achieved results. This strategy is particularly effective in handling complex topologies and unstructured point cloud data, surpassing the capabilities of conventional techniques.

Experimental Results#

The ‘Experimental Results’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made and demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method. A strong presentation will feature a clear description of the experimental setup, including datasets used, evaluation metrics, and comparison with baselines. Quantitative results, presented with error bars and statistical significance tests where appropriate, are key. Visualizations, such as graphs or tables, help showcase trends and patterns in the data. A detailed discussion of the results is necessary, highlighting both successes and limitations, explaining any unexpected findings, and connecting the results back to the paper’s core claims. Ablation studies help isolate the contributions of different components of the proposed method. Comparison with state-of-the-art methods is vital to demonstrate the advancement made by the research. Finally, a thoughtful analysis of the results, including limitations and directions for future work, provides valuable insights and concludes the section effectively.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore improving the efficiency and scalability of neural surface parameterization methods, potentially through more efficient network architectures or the incorporation of more advanced optimization techniques. Addressing the limitations of current methods in handling highly complex topologies and unstructured point clouds remains crucial. Further investigation into handling noise and outliers within the input data is also needed, as is the development of techniques for guaranteeing bijectivity and smoothness in the resulting UV mappings. Finally, exploring the integration of neural surface parameterization with downstream geometry processing tasks, such as texture synthesis and mesh editing, would unlock significant potential applications. Combining neural methods with traditional techniques could be a powerful avenue for further progress, leveraging the strengths of both approaches. The development of robust methods for handling a broader array of input data types and complexities remains a priority.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the bi-directional cycle mapping framework of the Flatten Anything Model (FAM). It shows the two branches of the model: one starting with a 2D lattice, transforming it to a 3D surface, and then back to a 2D parameterization; and another starting with a 3D point cloud, flattening it to a 2D parameterization and then reconstructing it in 3D. The figure highlights the shared parameters between modules, the learned cutting seams, and the resulting texture mapping.

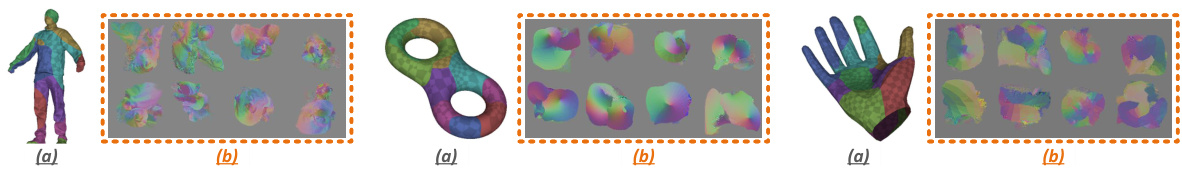

This figure compares the UV unwrapping and texture mapping results of the proposed FAM model and SLIM model on several open surface models. The FAM model’s results are shown alongside the results from the SLIM model for comparison. The 2D UV coordinates are color-coded according to the ground truth point-wise normals to aid in visualization and analysis of the results. This visualization helps to assess the quality and accuracy of the parameterization methods.

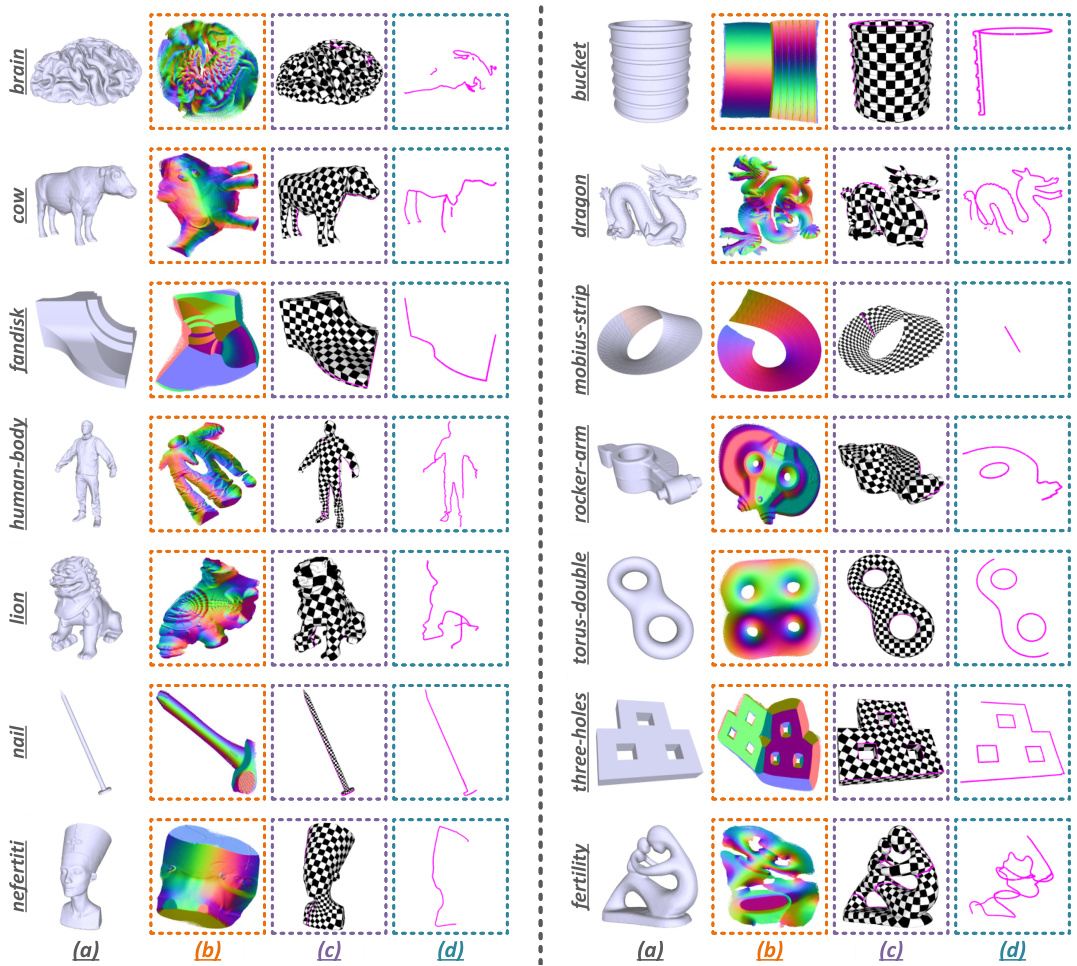

This figure shows the results of applying the Flatten Anything Model (FAM) to various 3D models. It demonstrates the model’s ability to produce high-quality, global free-boundary surface parameterizations. The four columns display: (a) the input 3D model, (b) the learned UV coordinates (a 2D representation of the 3D surface), (c) the texture mapping applied to the 2D UV coordinates, and (d) the cutting seams automatically discovered by FAM that are required for flattening the surface.

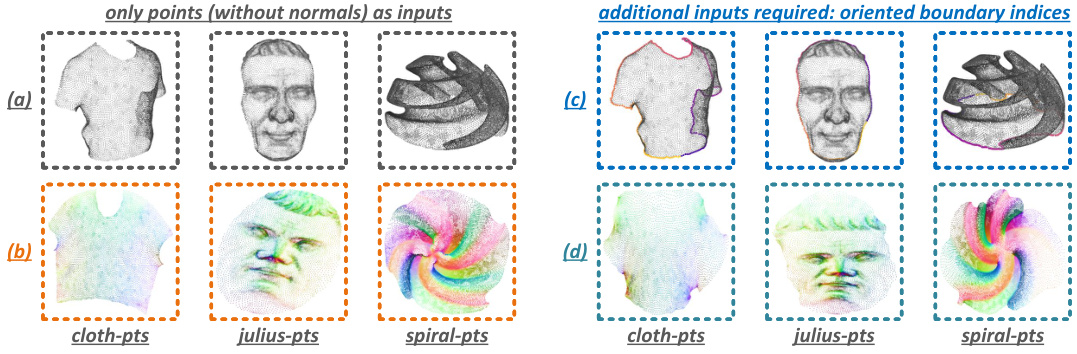

This figure compares the results of point cloud parameterization using the proposed Flatten Anything Model (FAM) and the FBCP-PC method. The left side shows FAM’s results, which directly takes unstructured points without normals as input. The right side shows FBCP-PC’s results, requiring additional inputs of oriented boundary indices. Three example point clouds are visualized: cloth-pts, julius-pts, and spiral-pts. The comparison highlights the difference in input requirements and the resulting parameterizations.

This figure illustrates the bi-directional cycle mapping framework of the Flatten Anything Model (FAM). It shows how the model learns to map between 2D and 3D spaces using two parallel branches: one going from 2D to 3D to 2D and the other from 3D to 2D to 3D. The modules in the same color share the same network parameters. The learned cutting seams and checker-image texture mapping are also shown.

This figure shows examples of surface parameterization results obtained using the Flatten Anything Model (FAM). It presents four columns: (a) the original 3D models, (b) the learned UV coordinates (a flattened representation of the 3D surface), (c) the texture mapping applied to the 2D UV coordinates and then mapped back onto the 3D model, and (d) the automatically learned cutting seams used to prepare the 3D model for flattening. The visualization of UV coordinates uses a rainbow color scheme to demonstrate the mapping from 3D to 2D. This figure highlights the model’s ability to parameterize various shapes, including those with complex geometries and topologies.

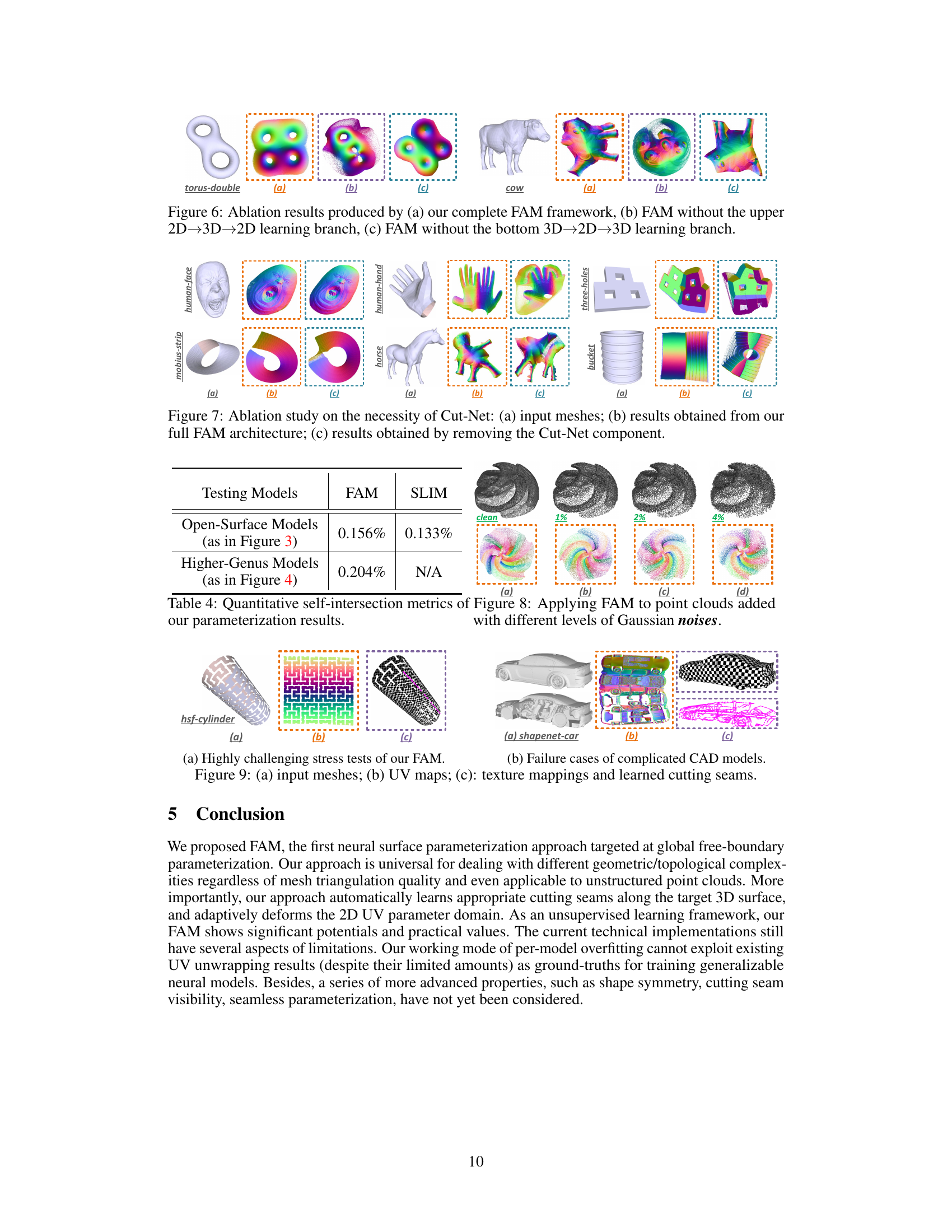

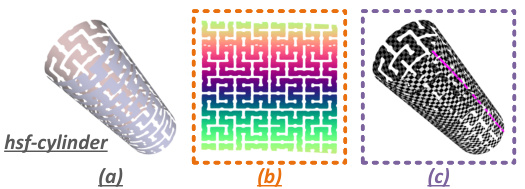

This figure shows the results of applying FAM to a Hilbert-space-filling cylinder model (a complex shape) and a ShapeNet car model (a CAD model with rich interior structures and multiple layers). Subfigure (a) displays the input 3D models. (b) Shows the learned UV coordinates (parameterization). (c) Presents the texture mappings and learned cutting seams generated by FAM on the input models. The results for the Hilbert-space-filling cylinder highlight the model’s ability to handle complex shapes. In contrast, the ShapeNet car model shows some limitations when dealing with intricate interior structures, indicating areas for future improvement.

This figure shows the results of applying FAM to three different models. The first model is a simple shape, the second is a more complex shape with internal structures, and the third is a very complex CAD model. The results show that FAM is able to generate accurate UV maps for simple shapes, but the accuracy decreases as the complexity of the shape increases. For the very complex CAD model, FAM is unable to generate a seamless UV map.

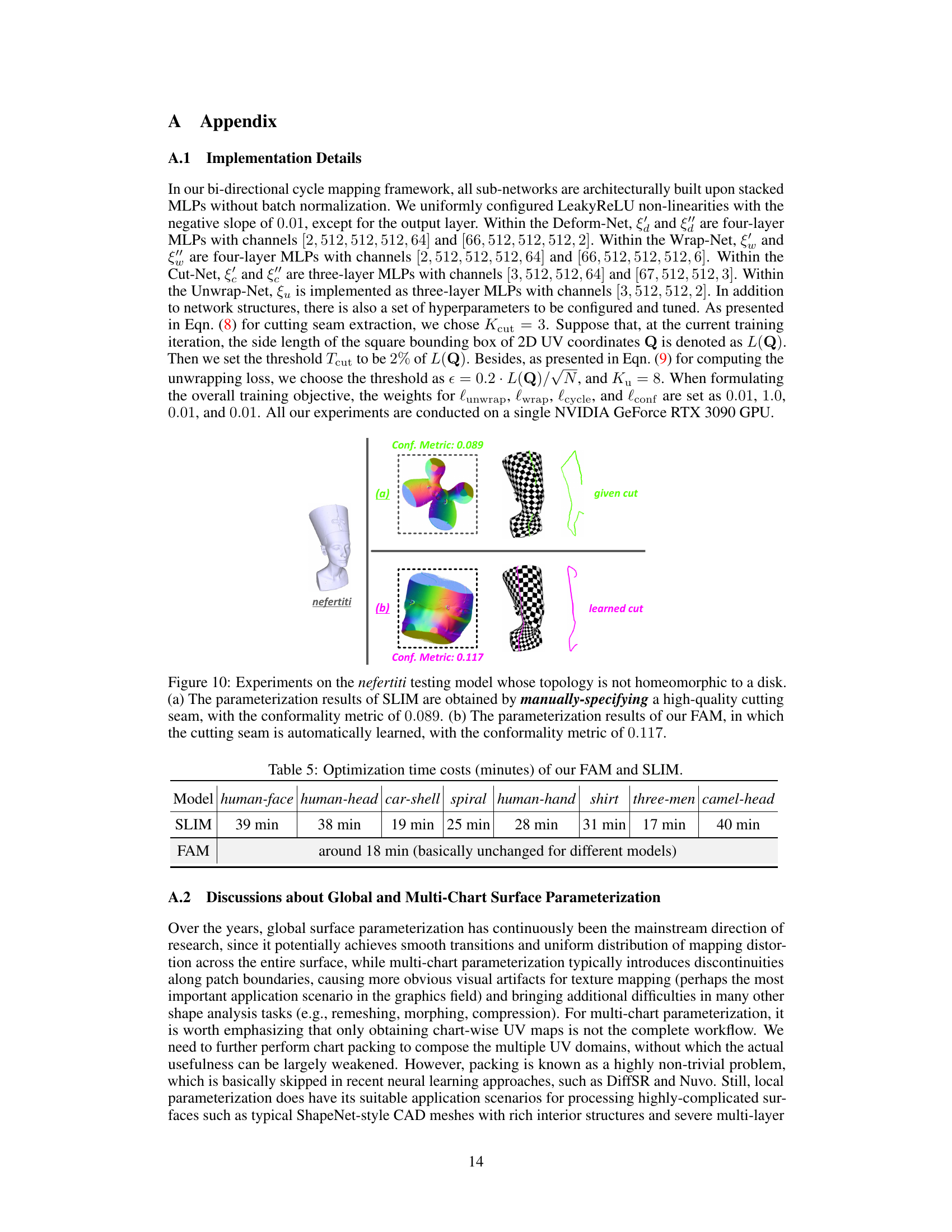

This figure compares the results of surface parameterization on the Nefertiti model using SLIM (manual cutting) and FAM (automatic cutting). Both methods show the UV unwrapping and texture mapping, along with the cutting seam that was used. FAM demonstrates its ability to automatically learn a reasonable cutting seam, while SLIM’s results rely on manual specification. The conformality metrics (lower is better) are shown, indicating slightly lower quality with FAM’s learned cutting seam.

This figure illustrates the Flatten Anything Model (FAM)’s bi-directional cycle mapping framework. It shows the two branches of the model: 2D to 3D to 2D and 3D to 2D to 3D. Modules with the same color share parameters. The figure also highlights the learned cutting seams and a checker-image texture mapping as a result of the process. The FAM uses these mappings to perform global free-boundary surface parameterization.

This figure illustrates the proposed bi-directional cycle mapping framework. It shows the two branches of the framework: 2D to 3D to 2D and 3D to 2D to 3D. Modules with the same color share parameters indicating a parameter sharing strategy. The learned cutting seams and checker image texture mapping are also visualized. This framework mimics the actual physical surface parameterization process.

More on tables

This table presents the quantitative conformality metrics for various 3D models processed using the proposed FAM method. Conformality, in this context, measures how well the parameterization preserves angles from the 3D surface to the 2D plane. Lower values indicate better conformality, meaning that angles are better preserved during flattening. The table allows for a comparison of the method’s performance across different models with varying geometric and topological complexity.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed Flatten Anything Model (FAM) and the state-of-the-art method FBCP-PC for point cloud parameterization. The comparison is based on the conformality metric for three different point cloud datasets: cloth-pts, julius-pts, and spiral-pts. Lower conformality values indicate better parameterization quality. FAM shows slightly worse results than FBCP-PC on the three datasets.

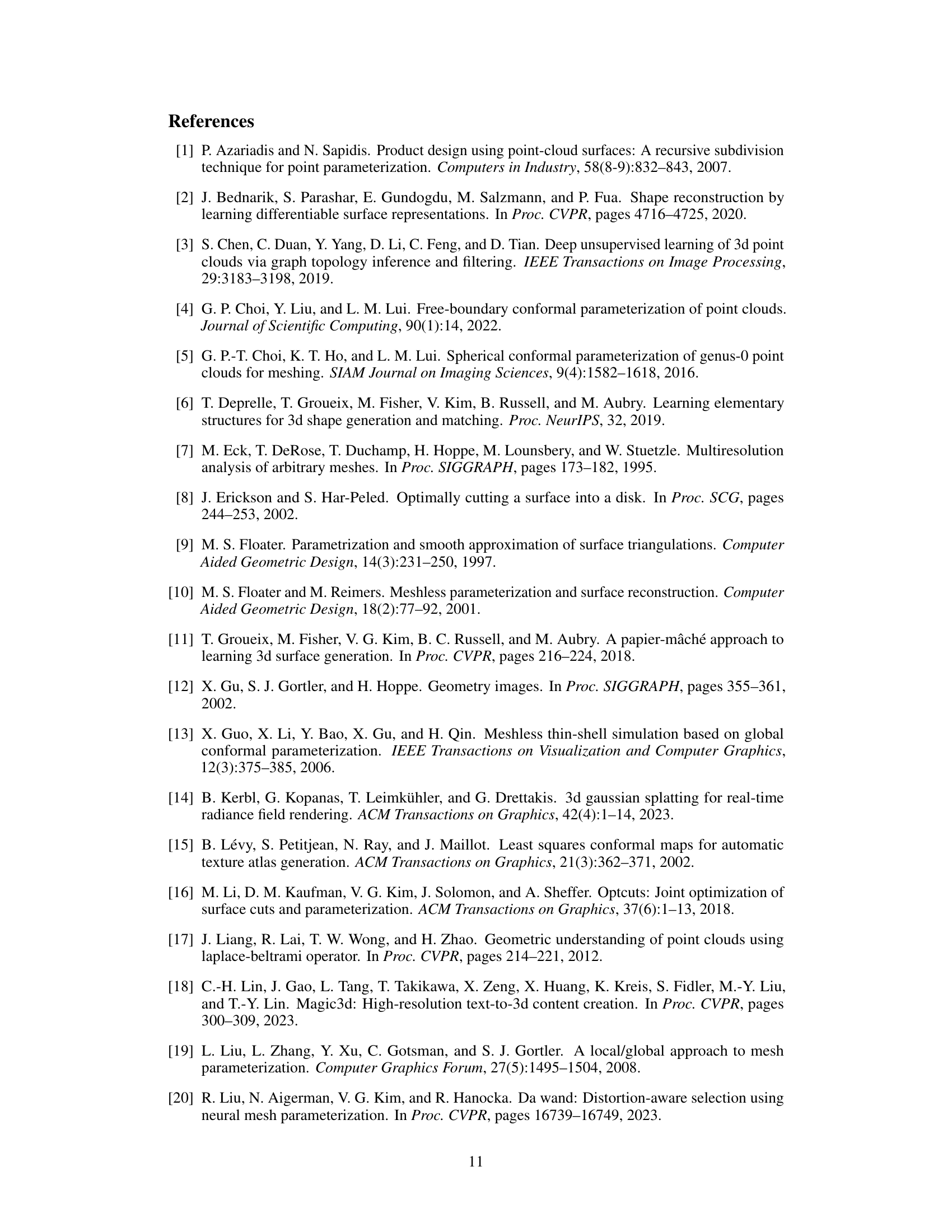

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the self-intersection metrics for the parameterization results obtained using the proposed FAM and the baseline SLIM methods. Self-intersection is a common issue in surface parameterization that can impact the quality of the resulting parameterization. The table reports the percentage of self-intersected triangles in the UV space for both FAM and SLIM on open surface models (from Figure 3) and higher-genus models (from Figure 4). The results show that FAM achieves lower self-intersection rates compared to SLIM, especially for the higher-genus models, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed FAM in preventing self-intersections.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed Flatten Anything Model (FAM) and the state-of-the-art method SLIM in terms of parameterization conformality. Conformality measures how well the method preserves angles during the mapping from 3D surface to 2D parameter space. Lower values indicate better conformality. The table shows that FAM significantly outperforms SLIM across various 3D models, demonstrating its superior performance in preserving angles during parameterization.

Full paper#