↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) often struggle with complex reasoning tasks, primarily due to the challenges in obtaining sufficient high-quality training data, especially for process supervision. Existing methods are either expensive (requiring manual annotations) or computationally intensive (using model-induced annotations). This lack of efficient and scalable training data significantly hinders the development of robust and reliable LLMs for complex reasoning.

AutoPSV addresses these issues by introducing a novel automated process-supervised verification method. It leverages an outcome-supervised model to automatically generate process annotations by detecting variations in confidence scores across reasoning steps. This innovative approach significantly reduces the need for manual or computationally expensive annotations, offering a more efficient and scalable solution for enhancing LLM reasoning capabilities. Extensive experiments demonstrate that AutoPSV improves LLM performance across various datasets, showcasing its potential to significantly advance the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on improving LLM reasoning capabilities. It introduces a novel, efficient method for automatically annotating reasoning processes, significantly reducing the need for manual annotation. This advances the field by offering a scalable and cost-effective solution for enhancing LLMs, opening new avenues for research in process supervision and verification techniques. Its focus on combining outcome and process supervision makes it particularly relevant to current trends in LLM development, and its demonstrated improvements across multiple benchmarks highlight its potential impact.

Visual Insights#

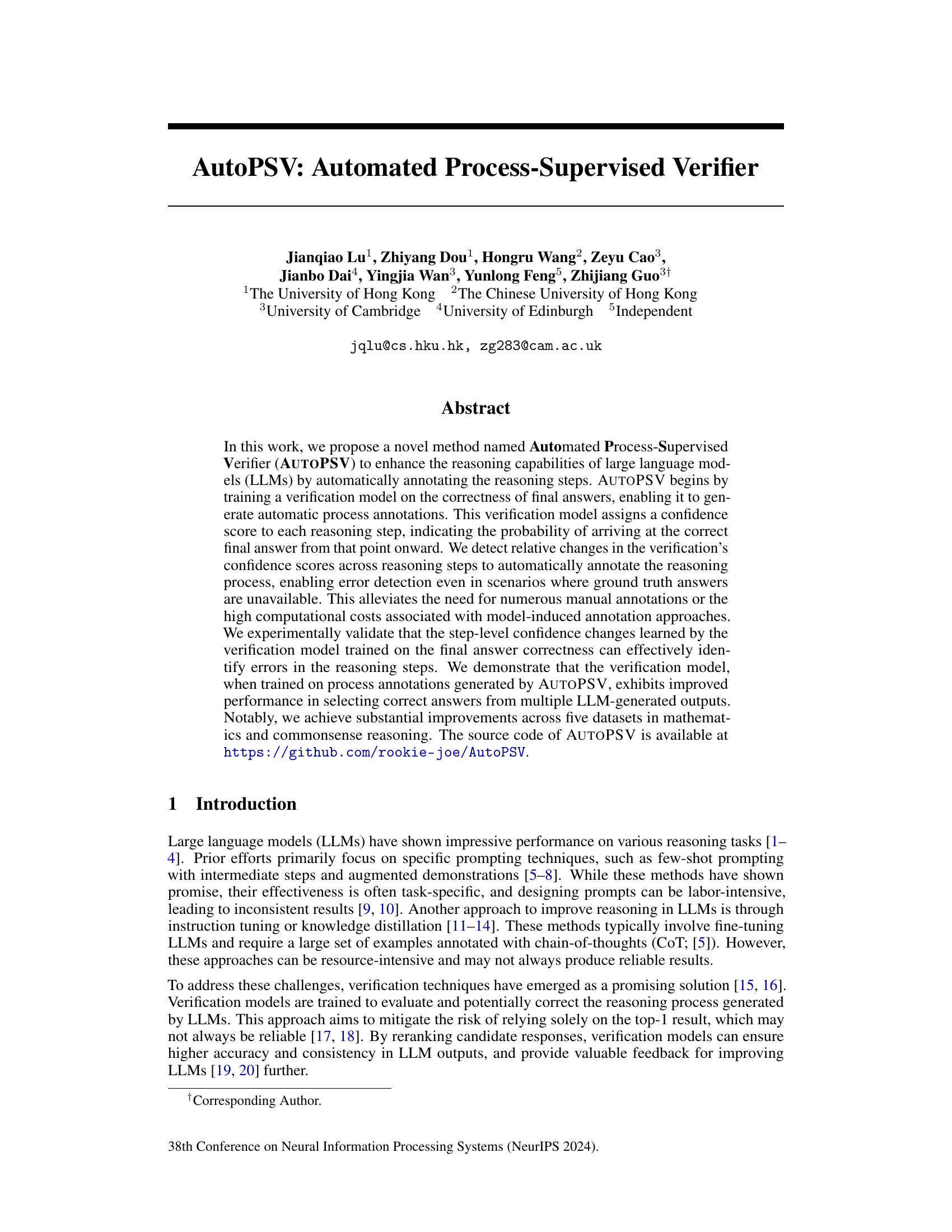

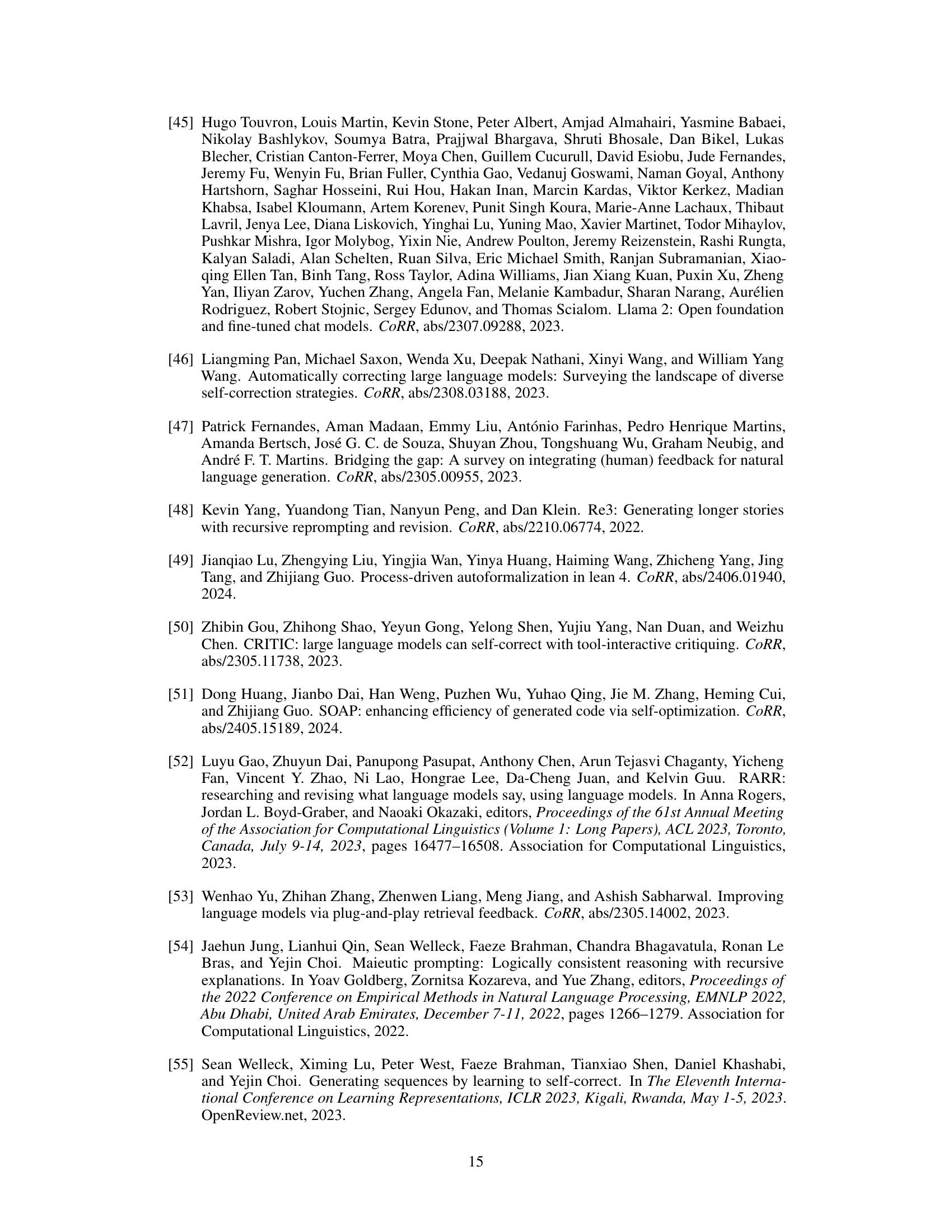

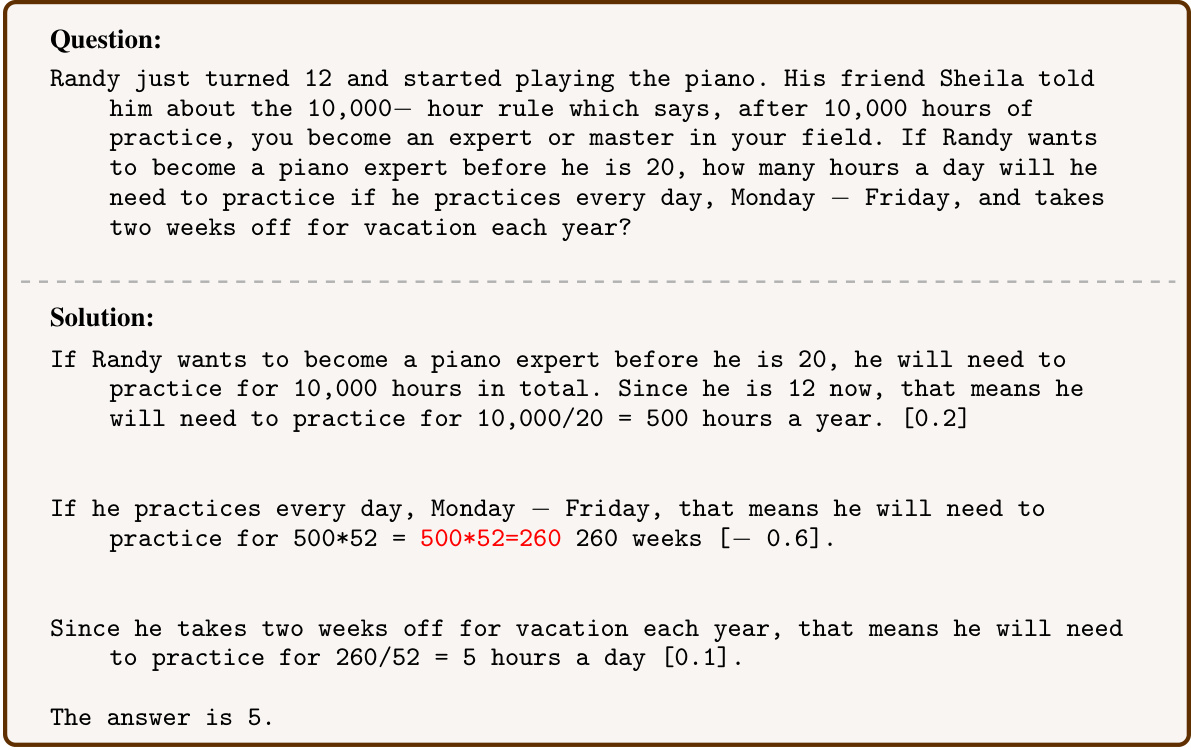

The figure illustrates the AUTOPSV framework. It starts with an outcome-supervised verifier trained on the correctness of final answers. This verifier assigns confidence scores to each reasoning step. AUTOPSV analyzes the relative changes in these confidence scores to automatically generate process annotations, labeling steps as correct or incorrect. These automatically generated annotations then serve as training data for a process-supervised verifier, improving the overall performance in selecting correct answers from multiple LLM-generated outputs. The process avoids the need for expensive human or model-based annotations.

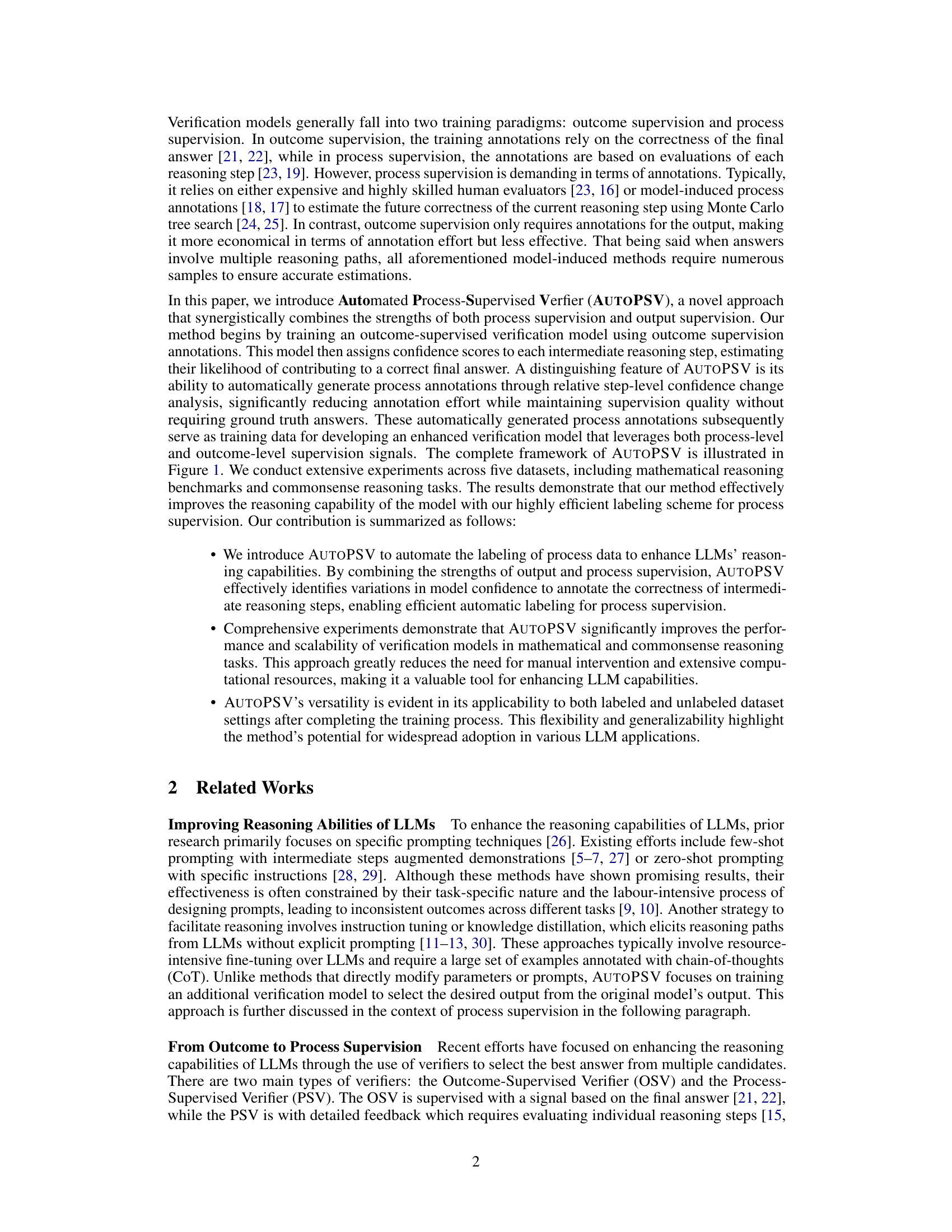

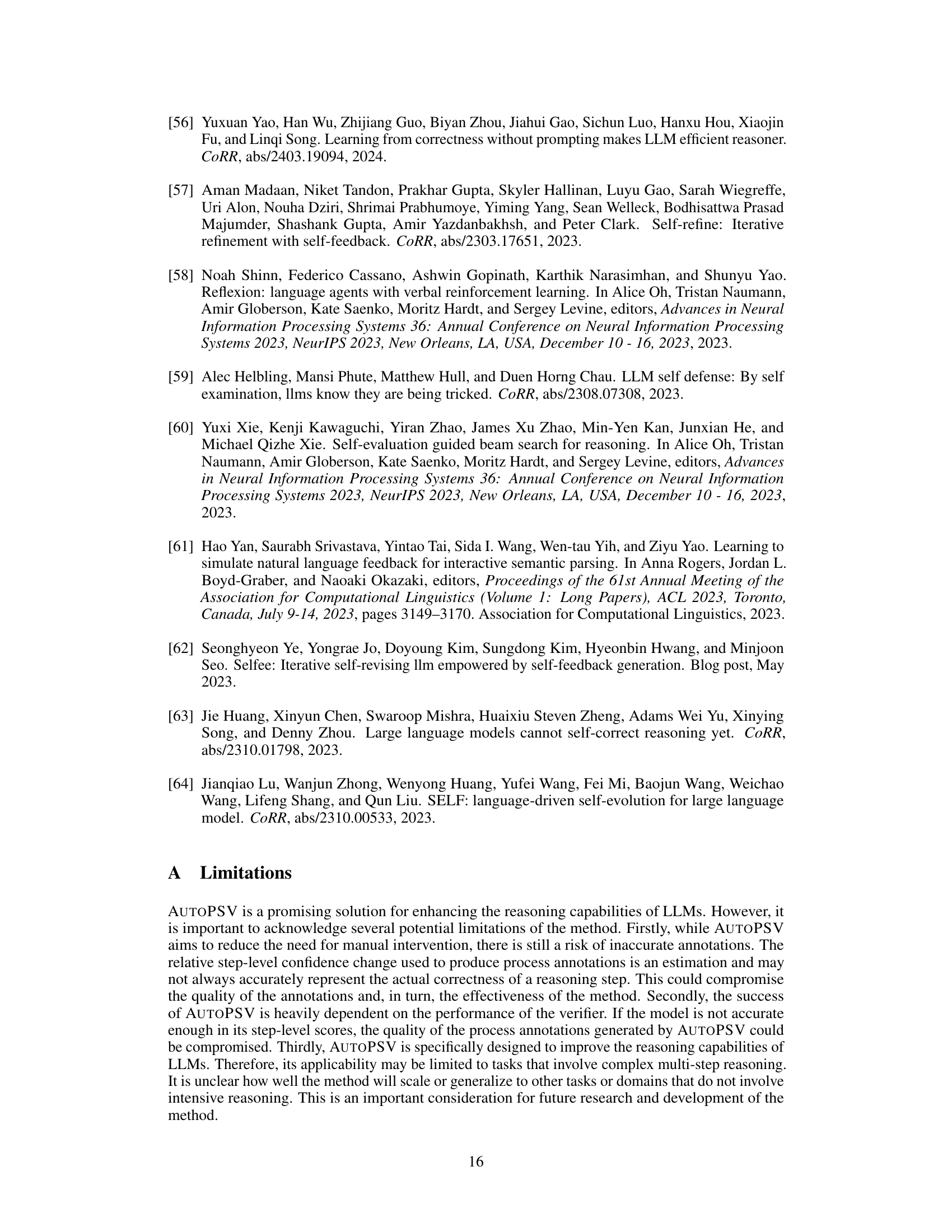

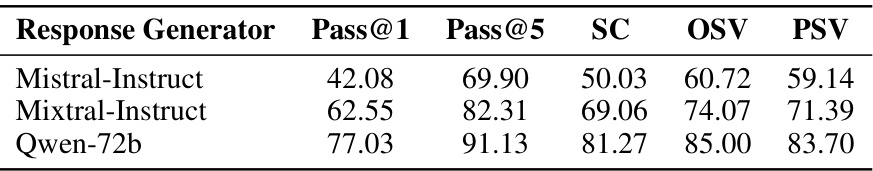

This table presents the performance of the Mixtral-Instruct language model on the GSM8K benchmark dataset. It shows the accuracy of the model in correctly identifying the top answer (Pass@1), the top 5 answers (Pass@5), and the self-consistency of its responses. The results are expressed as percentages.

In-depth insights#

Automating Verification#

Automating verification in the context of large language models (LLMs) presents a significant challenge and opportunity. Manual verification is time-consuming and expensive, limiting the scalability of LLM development and deployment. Automating this process can dramatically improve the efficiency and reliability of LLMs. Effective automation necessitates sophisticated techniques capable of evaluating not only the final outputs but also the intermediate reasoning steps, which often reveal subtle flaws or biases. A robust automated verifier should be able to identify errors, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies in an LLM’s reasoning process, and provide constructive feedback for improvement. This might involve training a separate verification model that learns to assess the validity of reasoning steps based on features like consistency, logical soundness, and alignment with established knowledge. Key considerations for automating verification include the design of effective evaluation metrics, the selection of appropriate training data, and the handling of complex or multifaceted reasoning tasks. Successfully automating verification could transform LLM development, leading to more reliable, trustworthy, and impactful applications.

Process Supervision#

Process supervision in the context of large language model (LLM) verification focuses on evaluating the correctness of each reasoning step within a model’s solution process, rather than just assessing the final answer. This granular approach offers several key advantages. First, it allows for the identification of errors at their source, providing more valuable feedback for model improvement than outcome-based supervision alone. Second, it enables the creation of more detailed training annotations, which can lead to more robust and accurate LLMs. However, process supervision presents challenges. Annotating each reasoning step is labor-intensive and costly, requiring substantial manual effort or complex automated methods. The paper explores a novel approach that attempts to mitigate this challenge by automatically generating process annotations using relative changes in confidence scores. This approach represents a significant step towards making process supervision more practical and scalable for LLM development, potentially unlocking substantial improvements in reasoning capabilities. Despite its promise, the effectiveness of automatic annotation remains dependent on the accuracy of the underlying verification model and further research is needed to fully address the limitations and challenges of process supervision.

Outcome-Process Synergy#

The concept of ‘Outcome-Process Synergy’ in the context of a research paper likely refers to a methodology that leverages both the final outcome and the intermediate steps of a process to enhance performance or understanding. It suggests a model where the accuracy of the final result (outcome) is used in conjunction with the analysis of the steps taken to achieve that result (process). This synergistic approach can offer several advantages. Firstly, using outcome data improves model efficiency, needing fewer labeled examples. Secondly, analyzing the process provides valuable insights into error detection and correction, which allows for more effective fine-tuning. Thirdly, this combined approach could lead to more robust models that are less susceptible to making mistakes during complex reasoning tasks. However, it’s important to consider the challenges. Balancing the emphasis on outcome versus process requires careful consideration. The quality of process analysis depends on the granularity and reliability of intermediate step representations. Furthermore, the computational cost of evaluating both outcome and process should be balanced against the potential improvement in performance. Finally, the interpretability of the results gained from this synergy requires further investigation.

LLM Reasoning Enhancements#

Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate impressive reasoning capabilities, but their performance can be inconsistent and error-prone. Reasoning enhancement techniques primarily focus on improving prompt engineering, such as few-shot prompting and chain-of-thought prompting, to guide the model towards more accurate solutions. However, these methods often require substantial human effort and can lead to inconsistent results. Another approach is to fine-tune LLMs on larger, more diverse datasets or with specific instructions. While effective, this approach can be resource intensive and time-consuming. Verification techniques offer a promising alternative: training separate verification models to evaluate and correct the LLM’s reasoning process. This involves outcome supervision (evaluating only the final answer) and process supervision (evaluating each reasoning step). Automating process supervision is a key challenge in verification, as manual annotation is expensive and time-consuming. Methods using model-induced process annotations, like Monte Carlo Tree Search, offer potential solutions but can be computationally expensive. This highlights a need for efficient and scalable methods to improve LLM reasoning, balancing accuracy, cost, and scalability.

AutoPSV Limitations#

The AUTOPSV method, while promising, has limitations. Inaccurate annotations are possible because the step-level confidence changes used are estimations and may not always perfectly reflect the true correctness of each reasoning step. The method’s success is heavily reliant on the verifier’s accuracy; if the verifier isn’t precise, the quality of the generated annotations suffers. Scalability to diverse tasks is also questionable; AUTOPSV’s strength lies in multi-step reasoning tasks, and its effectiveness on other task types needs further investigation. These limitations should be considered when assessing AUTOPSV’s overall applicability and potential impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure illustrates the AUTOPSV framework. It starts with an outcome-supervised verifier trained on the correctness of final answers. This verifier assigns confidence scores to each reasoning step. AUTOPSV then analyzes the relative changes in these confidence scores to automatically generate process annotations, labeling steps as correct or incorrect. These automatically generated annotations are then used to train a process-supervised verifier, improving the LLM’s reasoning capability. The process avoids the need for expensive manual or model-induced annotations.

This figure illustrates the AUTOPSV framework. It starts with an outcome-supervised verifier trained on the correctness of final answers. This verifier assigns confidence scores to each reasoning step. AUTOPSV then analyzes the relative changes in these confidence scores across steps to automatically generate process annotations. These annotations highlight potential errors even without ground truth, serving as process supervision data for training an enhanced verifier. This avoids the need for manual annotations or computationally expensive model-induced methods.

More on tables

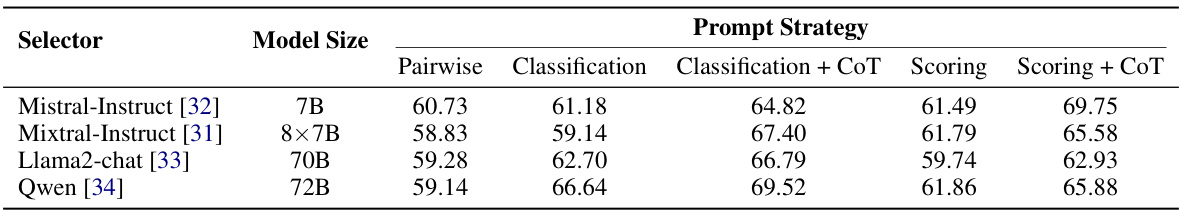

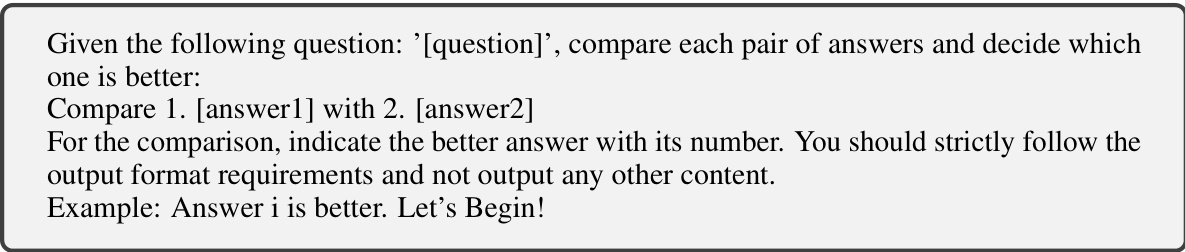

This table compares the performance of different LLMs (Mistral-Instruct, Llama2-chat, and Qwen) as response selectors, each using various prompt strategies (Pairwise Classification, Classification + CoT, Scoring, Scoring + CoT) to choose the correct answer from multiple candidate responses generated by Mixtral-Instruct. The accuracy of each method is presented for different model sizes, showing the effectiveness of each approach.

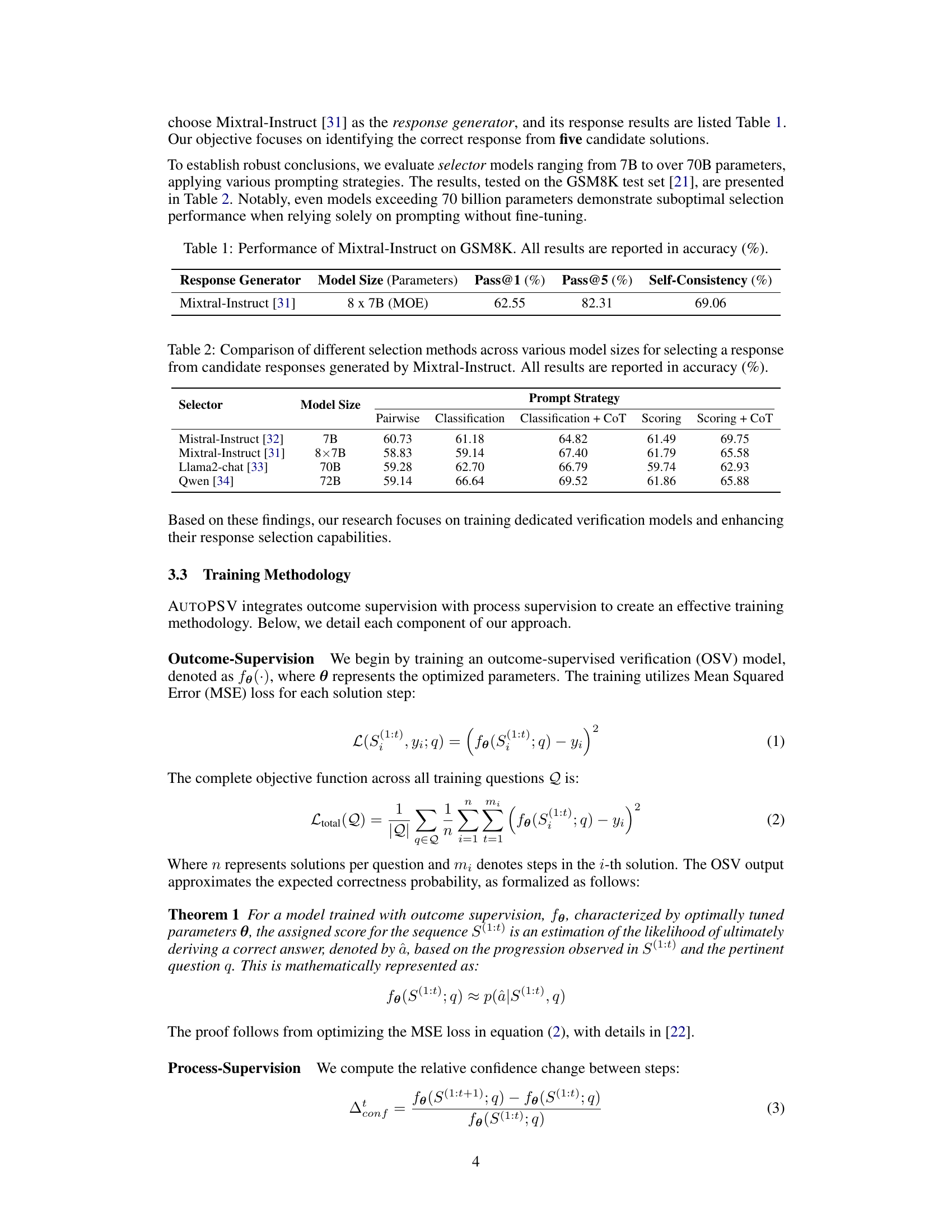

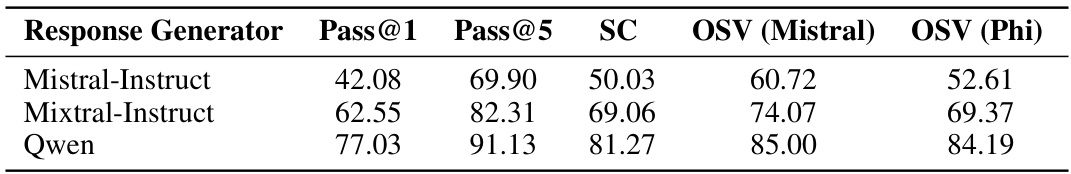

This table presents the performance of two different Outcome-Supervised Verifier (OSV) models (OSV (Mistral) and OSV (Phi)) across various Large Language Models (LLMs) used as response generators. The performance is measured by three metrics: Pass@1, Pass@5, and Self-Consistency (SC). Pass@k represents the percentage of times the correct response is among the top k responses. Self-Consistency evaluates the consistency of the model’s predictions across multiple runs. The results showcase the effectiveness and scalability of the OSV models in selecting the correct answer from multiple LLM outputs, particularly when using larger and more powerful response generators. The OSV models consistently outperform the Self-Consistency baseline, highlighting their potential to improve response selection in various reasoning tasks.

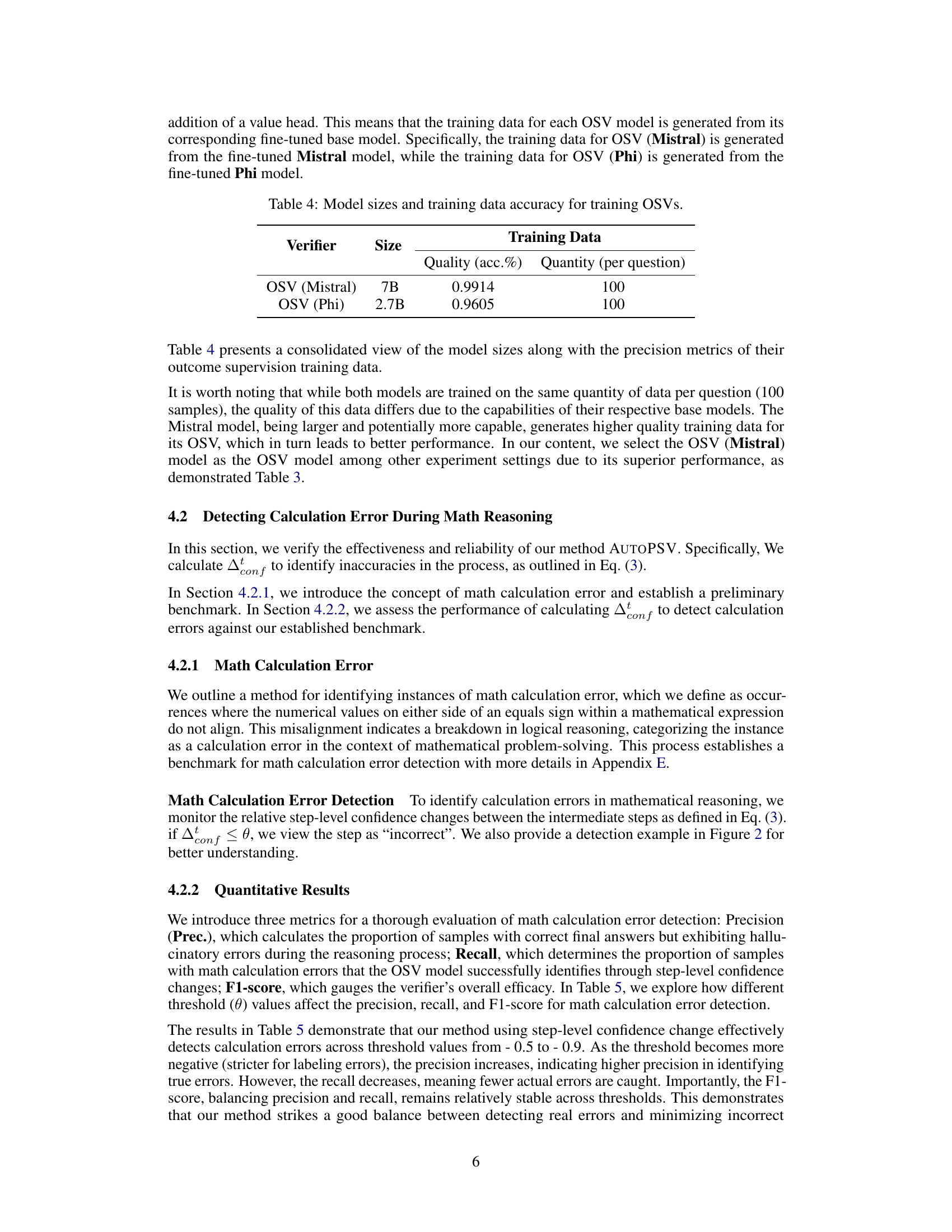

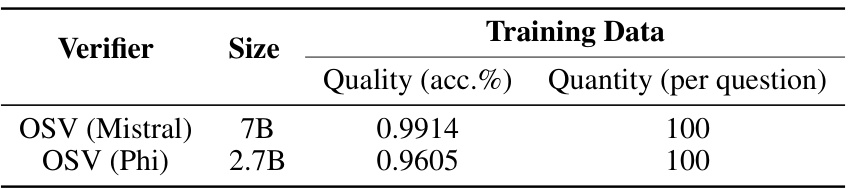

This table presents a consolidated view of the model sizes (OSV (Mistral) and OSV (Phi)) along with the precision metrics of their outcome supervision training data. It highlights the training data quality (accuracy) and quantity (number of samples per question) used for training each outcome-supervised verifier model. The difference in training data quality is attributed to the capabilities of their respective base models.

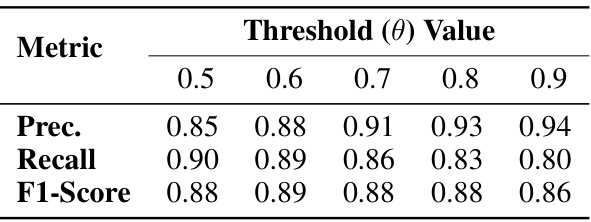

This table presents the performance of the math calculation error detection method across different threshold values. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are Precision (Prec.), Recall, and F1-Score. Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified calculation errors, Recall measures the proportion of actual calculation errors identified, and F1-Score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall providing a balanced measure of performance. The table shows how these metrics change as the threshold value (θ) varies, which is a parameter of the method.

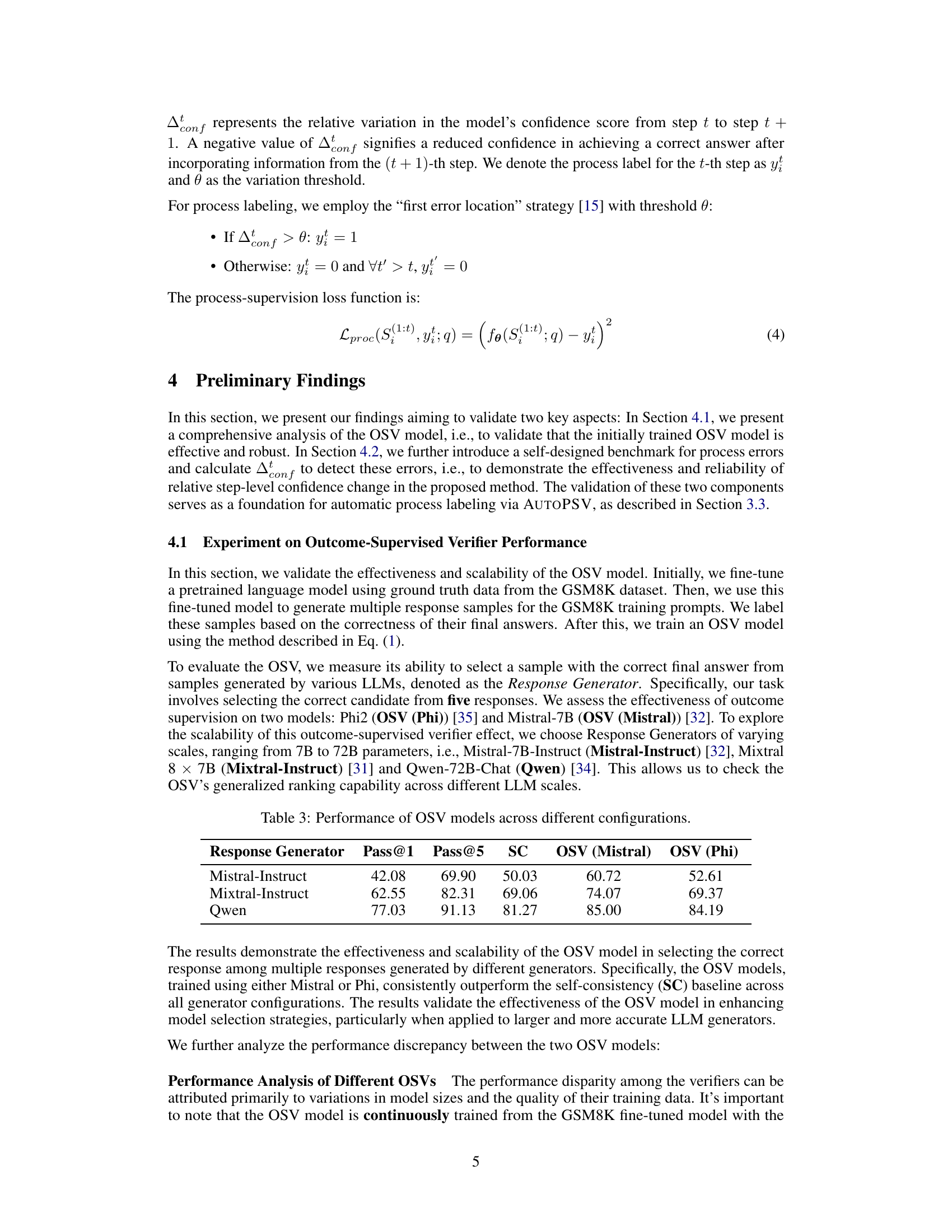

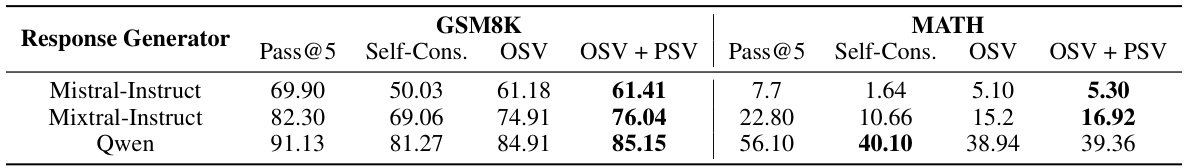

This table presents the performance of three different response selection methods (Self-Consistency, Outcome-Supervised Verifier (OSV), and Process-Supervised enhanced verifier (OSV+PSV)) on two mathematical reasoning benchmarks: GSM8K and MATH. The results are reported as Pass@5, which represents the probability of selecting the correct answer among the top 5 candidates generated by an LLM. The table shows the performance of each method for three different LLMs: Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen, highlighting the effectiveness of the process-supervised approach (OSV+PSV).

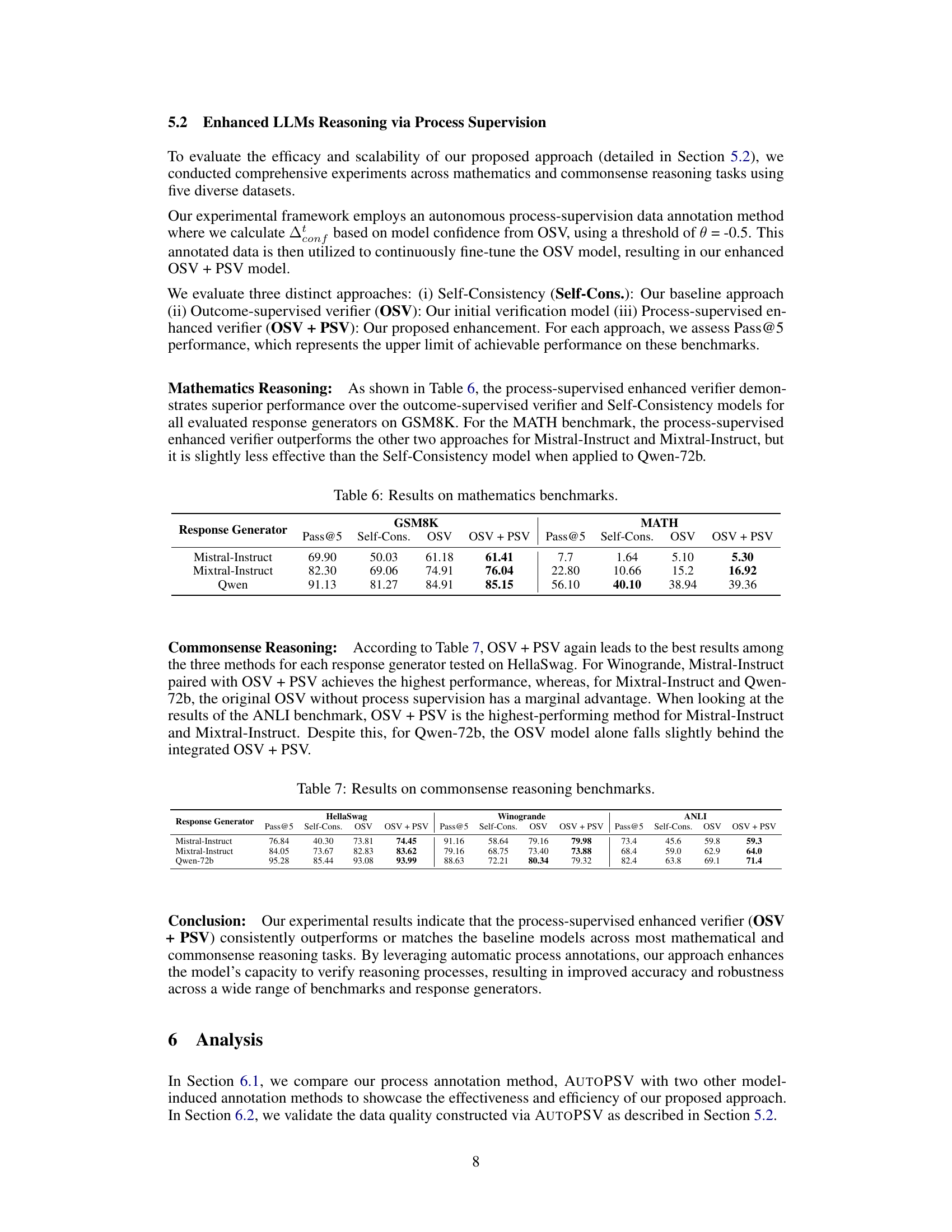

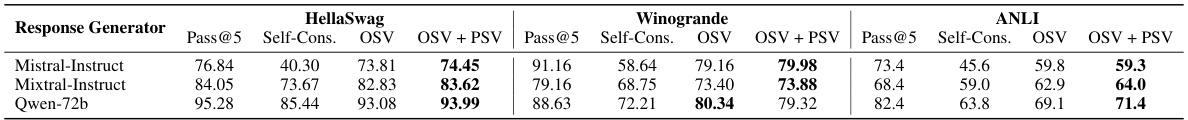

This table presents the results of the three different methods (Self-Consistency, Outcome-supervised verifier, and Process-supervised enhanced verifier) on three commonsense reasoning benchmarks: HellaSwag, Winogrande, and ANLI. The results are shown for three different response generators: Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen-72b. Pass@5, representing the top 5 accuracy, is reported for each method and generator combination on each benchmark.

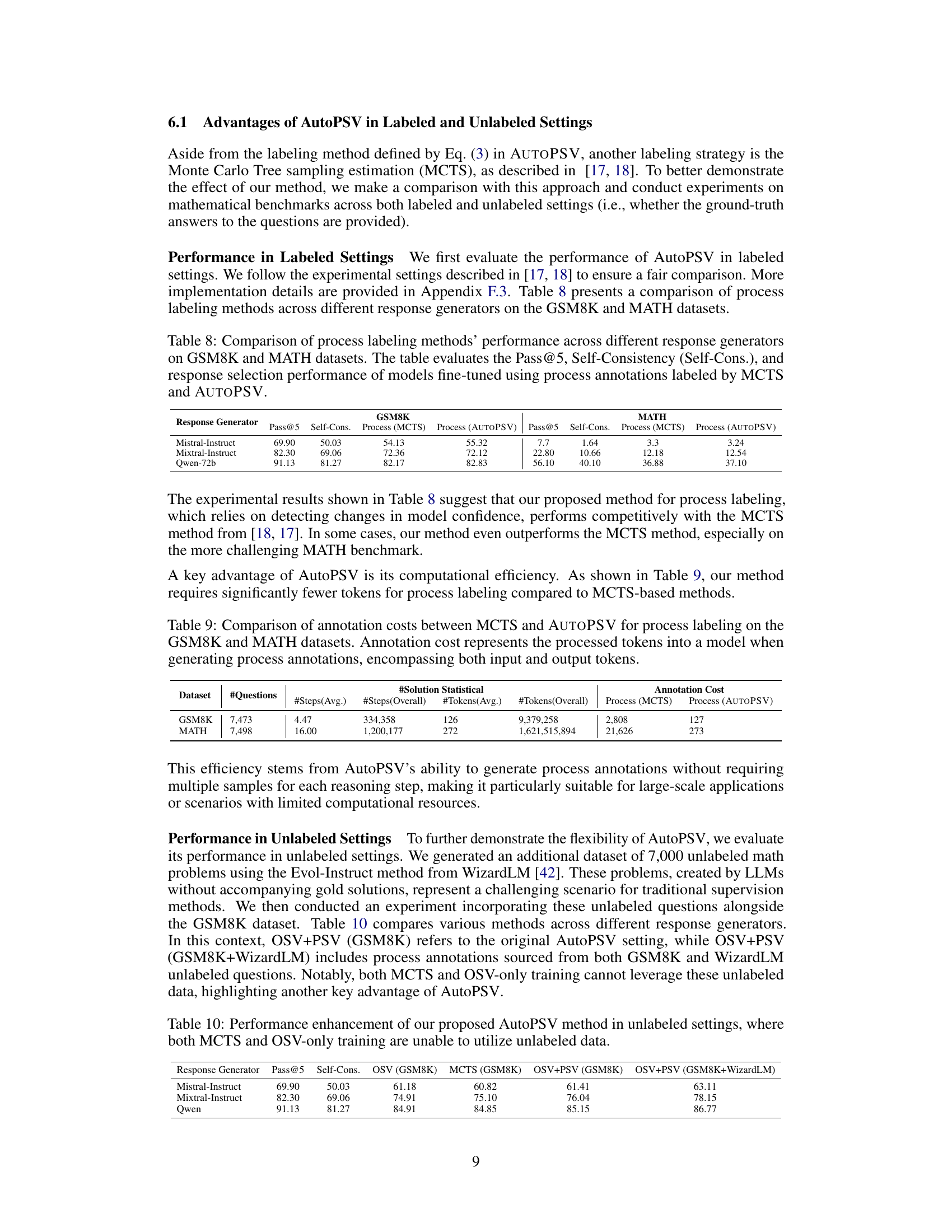

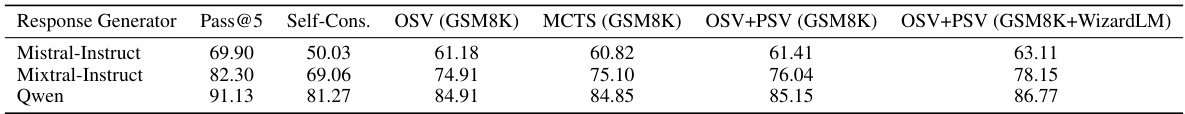

This table compares the performance of two process labeling methods (MCTS and AUTOPSV) on two datasets (GSM8K and MATH) across three different large language models (Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen-72B). The Pass@5 metric represents the accuracy of selecting the correct response from five candidates. Self-Consistency serves as a baseline, while Process (MCTS) represents a commonly used method for generating process-level annotations. The table highlights the effectiveness of AUTOPSV in improving the response selection performance of LLMs by providing more efficient process annotations compared to MCTS.

This table compares the computational costs of two process annotation methods: MCTS and AUTOPSV. It shows the average and total number of steps and tokens processed for each method on the GSM8K and MATH datasets. The results highlight the significantly lower computational cost of AUTOPSV compared to MCTS.

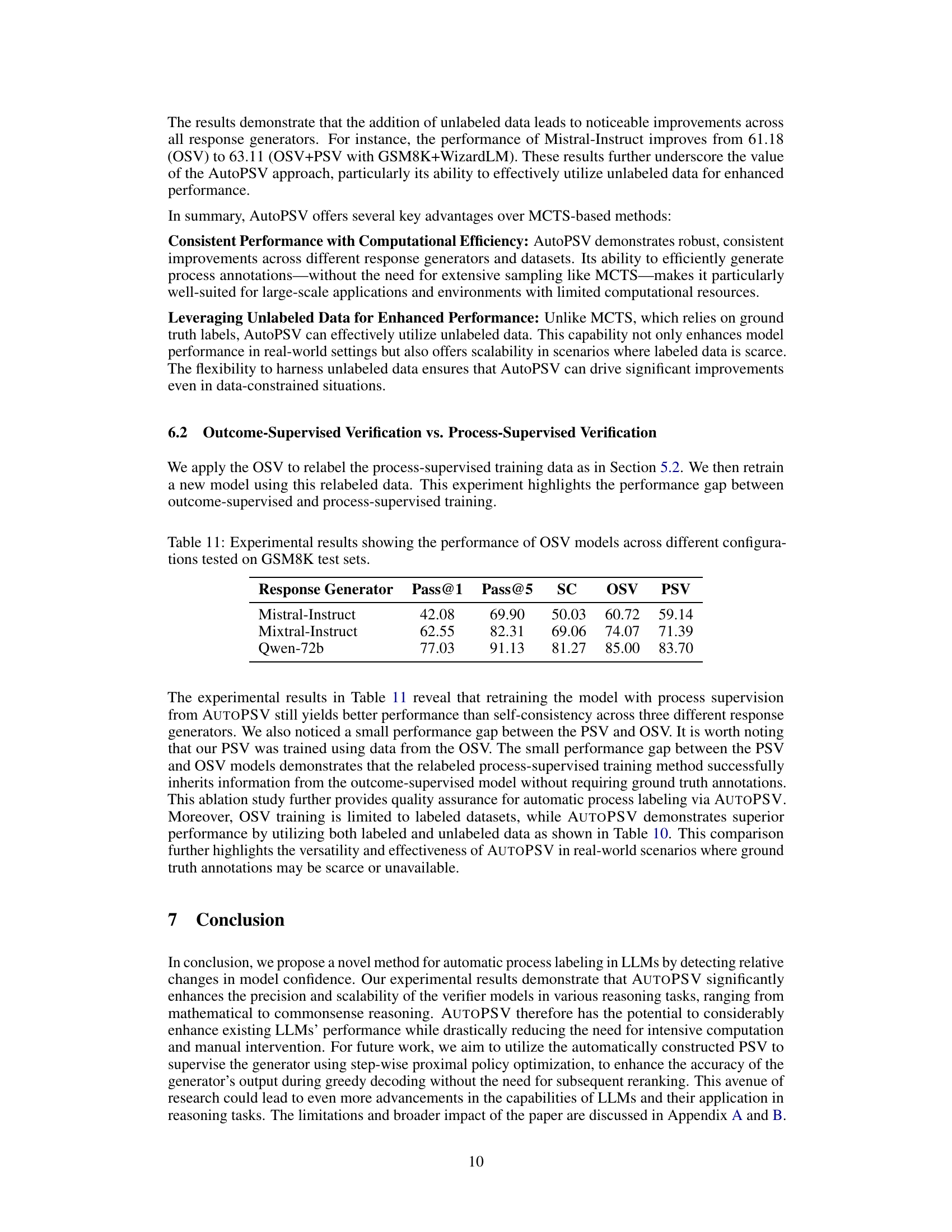

This table compares the performance of different methods for process labeling in unlabeled settings. It shows the Pass@5 scores achieved by different LLMs (Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen) using three methods: Self-Consistency (baseline), OSV trained only on GSM8K data, MCTS on GSM8K data, OSV+PSV on GSM8K, and OSV+PSV trained on both GSM8K and WizardLM unlabeled data. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of AutoPSV in leveraging unlabeled data to improve performance.

This table shows the performance comparison of different models on the GSM8K test set. The models compared are Self-Consistency (SC), Outcome-Supervised Verifier (OSV), and Process-Supervised Verifier (PSV). The results are presented for three different response generators: Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen-72b. The metrics used to evaluate performance are Pass@1 and Pass@5, representing the percentage of times the correct answer is ranked first and within the top five, respectively. The table highlights the impact of incorporating process-level supervision (PSV) on model performance compared to outcome-level supervision (OSV) and the baseline Self-Consistency method.

This table presents the results of the experiments conducted on mathematical reasoning benchmarks (GSM8K and MATH). It compares the performance of three different approaches: Self-Consistency (Self-Cons.), Outcome-supervised verifier (OSV), and Process-supervised enhanced verifier (OSV + PSV). The performance metric used is Pass@5, representing the top 5 accuracy in selecting the correct answer. The table is broken down by response generator (Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen) and benchmark dataset. This allows for a detailed comparison of the different methods across different scales of LLMs and problem types.

This table presents the performance of two Outcome-Supervised Verifier (OSV) models, OSV (Mistral) and OSV (Phi), across various Large Language Models (LLMs) used as response generators. The performance is measured by Pass@1, Pass@5, and Self-Consistency (SC) on the GSM8K dataset. It demonstrates the effectiveness and scalability of OSV in response selection.

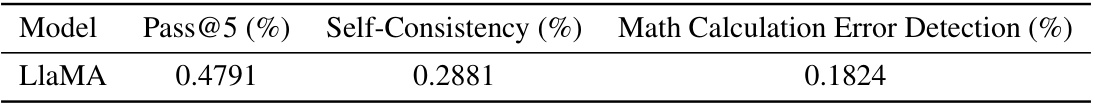

This table presents the performance of the LlaMA model on the GSM8K training dataset. The evaluation is done using a few-shot chain-of-thought (cot) prompting strategy. Three key performance metrics are reported: Pass@5 (the percentage of times the correct answer is among the top 5 generated answers), Self-Consistency (a measure of the model’s internal consistency in generating answers), and Math Calculation Error Detection (the percentage of times the model correctly identifies mathematical calculation errors). The table shows that the LlaMA model exhibits moderate performance across all three metrics, with room for improvement in its ability to generate correct answers and detect calculation errors. This data is used to establish a baseline for comparing the performance of the AUTOPSV method.

This table presents the performance of two outcome-supervised verifier (OSV) models, OSV (Mistral) and OSV (Phi), across different large language models (LLMs) used as response generators. It evaluates the performance of each OSV model’s ability to select the correct answer from multiple LLM-generated responses using three metrics: Pass@1 (accuracy of selecting the correct response as the top choice), Pass@5 (accuracy of selecting the correct response within the top five choices), and Self-Consistency (a baseline metric representing the consistency of the LLM itself). The results show the effectiveness and scalability of OSV models in response selection across LLMs of varying sizes.

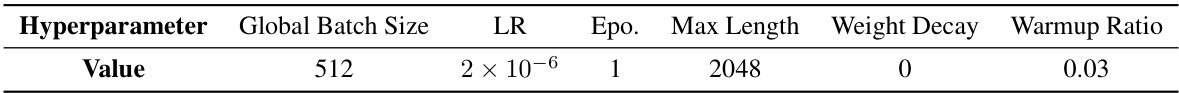

This table lists the hyperparameters used during the supervised fine-tuning (SFT) process to train the outcome-supervised verifier model. The hyperparameters shown include global batch size, learning rate (LR), number of epochs (Epo), maximum sequence length (Max Length), weight decay, and warmup ratio.

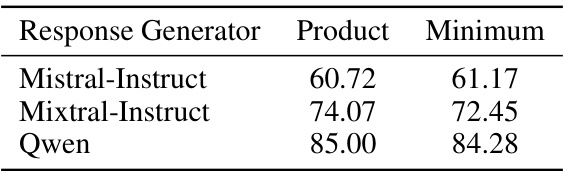

This table presents the comparison of two different aggregation functions (Product and Minimum) for step-level scores, evaluated on the GSM8K dataset using three different response generators: Mistral-Instruct, Mixtral-Instruct, and Qwen. The results show that the choice of aggregation function has a minor impact on the overall performance.

Full paper#