↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The nearest neighbor rule, a fundamental machine learning algorithm, has long been studied under the assumption of independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.) data. This paper challenges this assumption by exploring its behavior under more realistic settings where data might not be i.i.d. Existing studies showed that the nearest neighbor rule’s consistency is only guaranteed under very specific and stringent conditions. The paper addresses the limitations of these previous studies by proposing new theoretical frameworks for analyzing the algorithm’s consistency in the non-i.i.d. case.

The paper proposes two new process classes, ergodically dominated and uniformly dominated processes, to characterize the behavior of data streams that are not i.i.d. It then demonstrates that the nearest neighbor rule is consistent even for non-i.i.d data streams under these new frameworks. This is done for a general class of functions and for upper doubling spaces. The paper shows that the worst-case scenarios where the algorithm fails are actually very rare under the new framework. This extends the applicability of the nearest neighbor rule to a much broader range of practical applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly expands the understanding of the nearest neighbor rule’s consistency in online learning and challenges existing assumptions. It introduces novel theoretical frameworks (ergodically and uniformly dominated processes) for analyzing non-i.i.d. data and establishes conditions under which the nearest neighbor algorithm is consistent, even under challenging circumstances. These findings could impact various machine learning applications that handle non-i.i.d. streaming data.

Visual Insights#

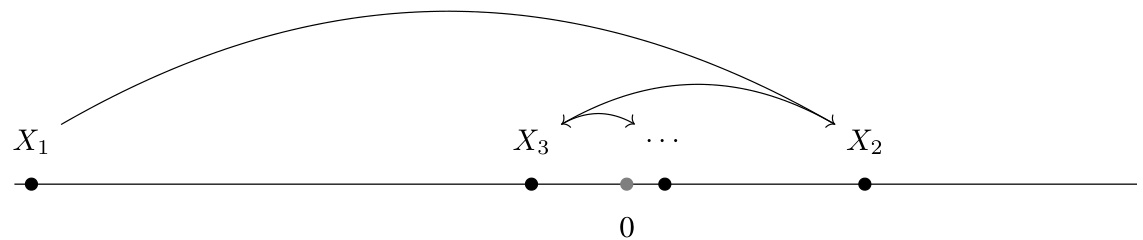

The figure shows a simple example where the 1-nearest neighbor rule fails to learn a threshold function. The instance sequence is constructed such that the nearest neighbor always has the opposite label, resulting in a mistake at every round. The x-axis represents the feature space, and the points illustrate the sequence of instances presented to the learner. The labels are implicitly represented by the position of the points relative to the zero on the x-axis.

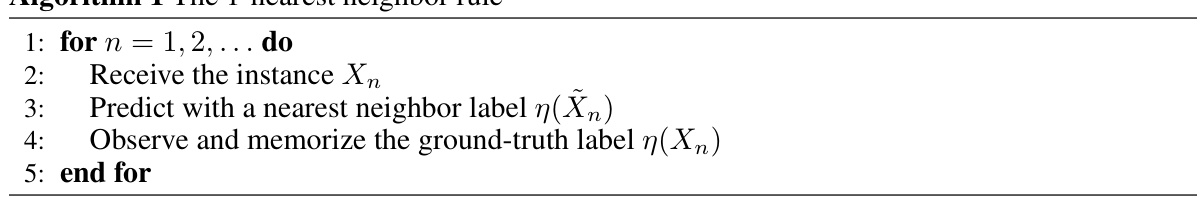

This algorithm describes the 1-nearest neighbor rule, a fundamental prediction strategy in online classification. The learner receives an instance, predicts its label using the label of its nearest neighbor in the already-seen data, observes the true label, and then memorizes both the instance and its true label for future use. The process repeats for a never-ending stream of prediction tasks.

In-depth insights#

NN Rule Consistency#

The nearest neighbor (NN) rule’s consistency is a central theme in machine learning, focusing on whether its prediction accuracy improves with more data. Realizable settings, where the true function is within the hypothesis space, are often considered. Early analyses established consistency under stringent conditions like i.i.d. data and well-separated classes. However, non-i.i.d. data and the presence of classes close together significantly challenge consistency. This research investigates online consistency, where predictions are made sequentially, and the label is revealed after each prediction. A key focus is establishing consistency under milder assumptions that relax the strong statistical or geometric constraints. The core finding highlights that NN consistency depends intricately on how the data is generated (stochastic process). Specifically, the mild conditions of uniform absolute continuity and upper doubling measures are sufficient to guarantee consistency, showing robustness beyond prior assumptions.

Negligible Boundary#

The concept of “Negligible Boundary” in the context of a classification problem centers on the idea that most points in the feature space are well-separated from points belonging to different classes. It implies that the decision boundary, which separates data points of different classes, has a small measure or is insignificant in some relevant sense. This condition weakens the strong geometric assumptions often made in machine learning, such as uniformly separated classes. A function with a negligible boundary essentially means there is a clear margin around each point, making classification easier because misclassifications are less likely due to points being near the boundary. This relaxation allows for more practical applications where strict separation isn’t always guaranteed, and the nearest neighbor method can still maintain its effectiveness in such scenarios. The effectiveness of using such a strategy hinges on the property that errors caused by the classifier will eventually vanish because they will only occur in the negligible boundary, and the proportion of such regions is very small. The concept is critical for proving consistency in non-i.i.d settings, and is a major focus of the research paper.

Universal Consistency#

The concept of “Universal Consistency” in the context of machine learning, specifically concerning the nearest neighbor rule, is a significant advancement. It tackles the challenge of proving the algorithm’s effectiveness not just under restrictive conditions (like i.i.d. data or well-separated classes), but for all measurable functions within a defined metric space. Achieving this requires imposing relatively mild constraints, such as uniformly dominated processes and upper doubling measures on the underlying space. This broadens applicability significantly. The results show that even without strong assumptions on data or the target function, the nearest neighbor rule still effectively learns under this “universal” scenario. The key is the combination of the inherent inductive bias of the nearest neighbor rule and the subtle constraints on the data generating process, preventing the accumulation of problematic instances. Doubling metric spaces and uniform domination are crucial for the universal consistency result, highlighting the interplay between geometric properties of the space and the statistical properties of the data stream.

Worst-Case Scenarios#

Analyzing worst-case scenarios in a research paper necessitates a nuanced understanding of the context. It’s crucial to identify what constitutes a worst-case scenario within the specific problem domain. Is it a scenario with the highest error rate, the slowest convergence, or some other critical metric? A comprehensive analysis would involve exploring the conditions leading to these worst-case scenarios. This might involve examining the characteristics of the input data (e.g., high dimensionality, non-linearity, or adversarial examples), the limitations of the algorithm itself, or the interaction between both. Furthermore, the analysis should discuss how realistic or frequent these scenarios are in practice. A truly insightful paper would highlight whether the worst-case scenarios are pathological outliers or represent a significant challenge in real-world applications, potentially proposing mitigation strategies to overcome these problems. Simply identifying the existence of a worst-case scenario isn’t enough, understanding its implications and potential solutions provides significant value.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to more general metric spaces beyond doubling spaces is crucial, as many real-world datasets do not possess this property. Investigating the impact of different distance metrics on the consistency and convergence rates of the nearest neighbor rule would yield valuable insights. Furthermore, exploring the use of weighted nearest neighbors or more sophisticated neighborhood selection techniques could significantly enhance performance. Combining nearest neighbor methods with other learning paradigms presents exciting possibilities. Investigating the effectiveness of nearest neighbor approaches in high-dimensional or non-Euclidean spaces warrants further research. Finally, developing robust and efficient algorithms for large-scale nearest neighbor search is a key practical challenge requiring attention. These combined efforts promise to advance the understanding and application of the nearest neighbor rule in diverse settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

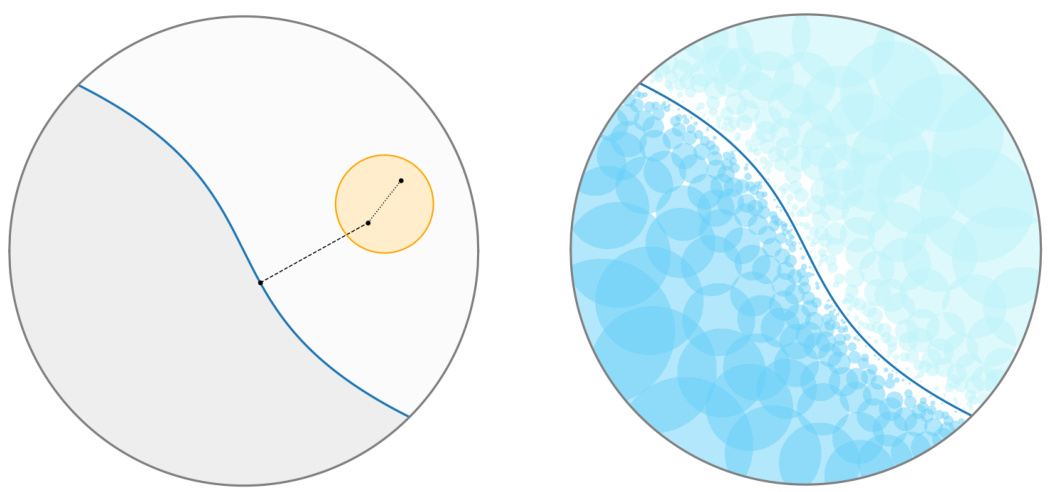

The figure demonstrates the concept of mutually-labeling sets. The left panel shows a single mutually-labeling set (orange circle) where all points within the set are closer to each other than they are to points of a different class. This means the nearest neighbor algorithm will make at most one mistake in this region. The right panel illustrates how many such sets can cover most of the space, leaving only a small region (white area) where mistakes might be made. This small region shrinks as more data arrives, illustrating how the nearest neighbor algorithm’s mistake rate eventually vanishes.

The figure visualizes the concept of mutually-labeling sets and how they’re used to prove the consistency of the nearest neighbor rule. The left panel shows a single mutually-labeling set (a ball) where all points within have a margin (distance to nearest point of a different class) greater than the set’s diameter. The right panel illustrates how multiple such sets can cover almost all of the space, leaving only a small region where mistakes might occur.

Full paper#