↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Open-source large language models (LLMs) are vulnerable to harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs), where malicious actors fine-tune models for harmful purposes. Existing safety measures are easily circumvented through further fine-tuning. This necessitates robust defense mechanisms that can operate even when attackers have access to model weights. The current approaches focus on adding safety guardrails but such methods are vulnerable to being bypassed.

This paper introduces Representation Noising (RepNoise), a defense mechanism that addresses this challenge. RepNoise works by removing information about harmful representations within the model, making it difficult for attackers to recover this information during fine-tuning. The authors demonstrate RepNoise’s effectiveness through experiments, showing that it mitigates HFAs across different types of harm, generalizes well to unseen attacks, and doesn’t significantly degrade the LLM’s performance on benign tasks. The research emphasizes the importance of “depth” in effective defenses—the degree to which information about harmful representations is removed across all layers of the model.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel defense mechanism against harmful fine-tuning attacks on large language models (LLMs). This is a significant issue in the field, as LLMs are increasingly being used for various purposes, some of which could be malicious. The proposed RepNoise method offers a new direction for research, particularly in mitigating in-distribution attacks even with weight access, and highlights the importance of “depth” in effective defenses. This opens up new avenues for improving LLM safety and security.

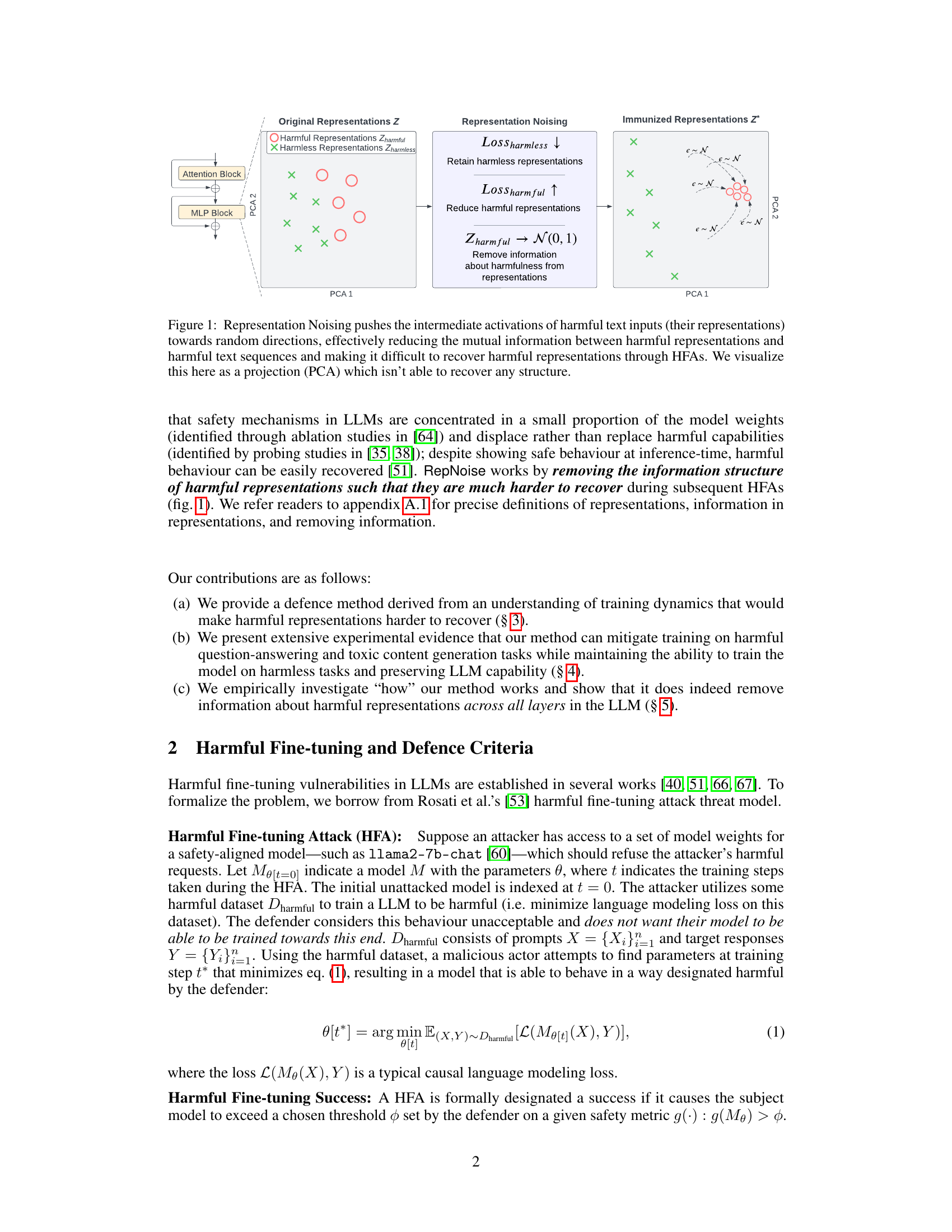

Visual Insights#

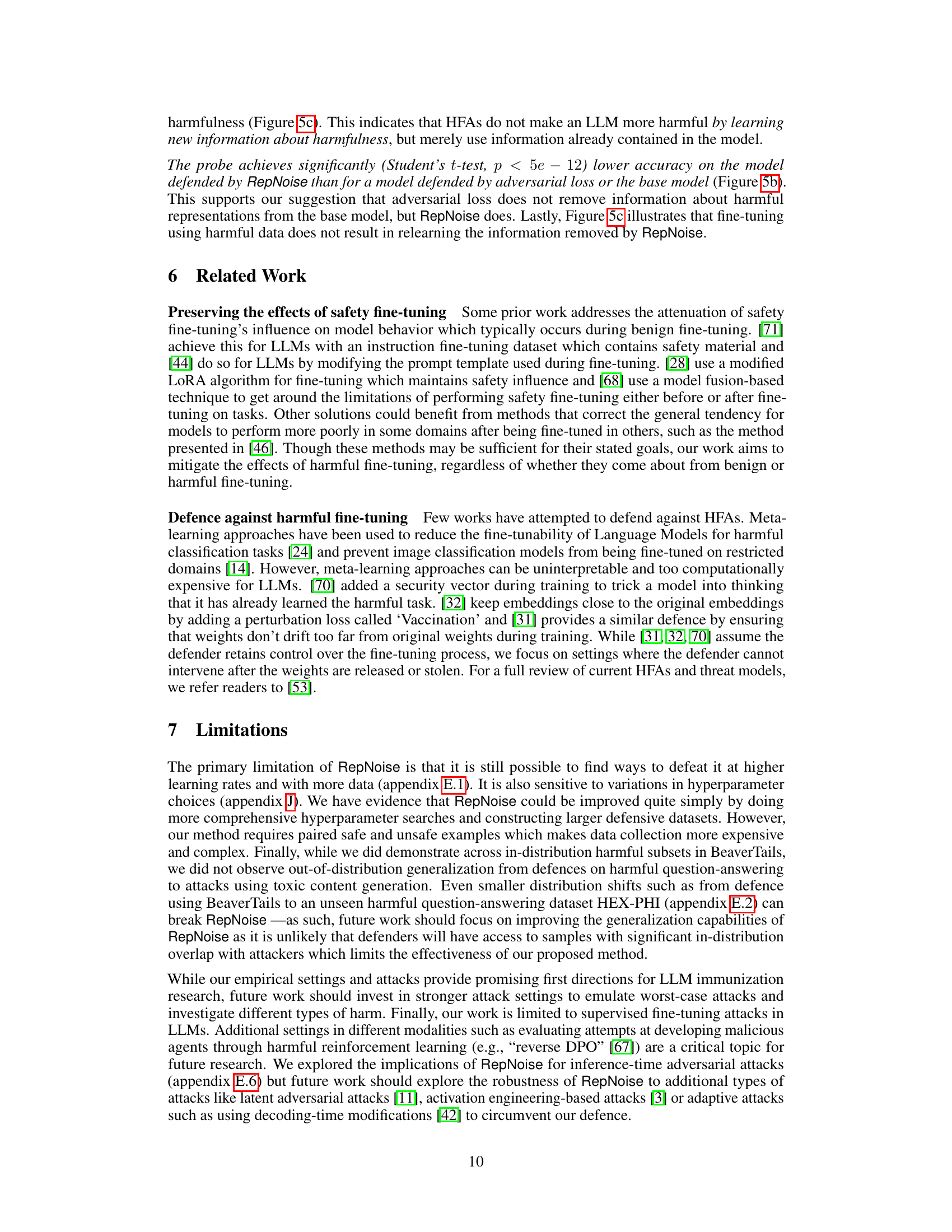

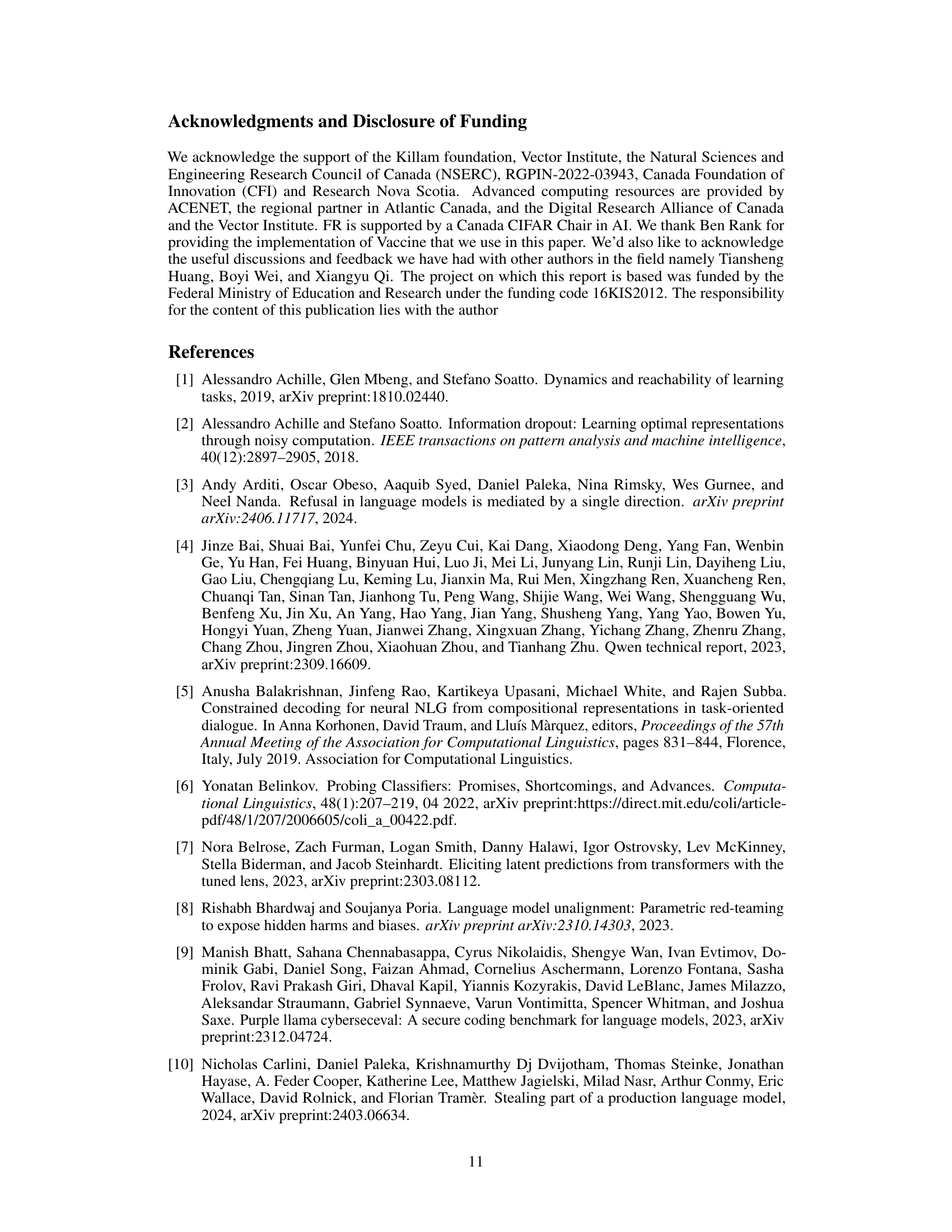

This figure illustrates the core concept of Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how the method works by pushing the intermediate activations (representations) of harmful text inputs towards random directions. This process reduces the mutual information between harmful representations and harmful text sequences, making it difficult for attackers to recover harmful representations even if they have access to the model’s weights. The visualization uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to show that the structure of harmful representations is destroyed after applying RepNoise.

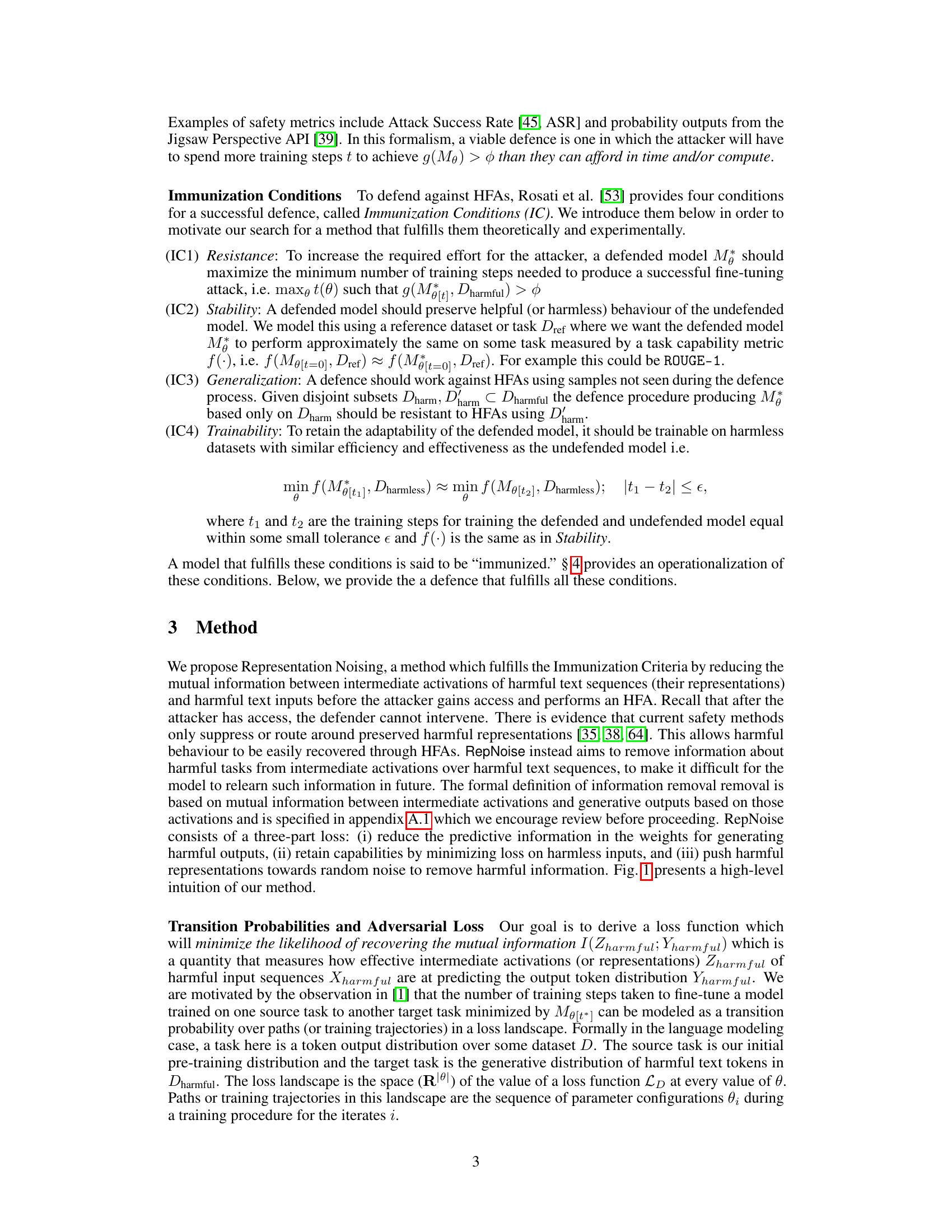

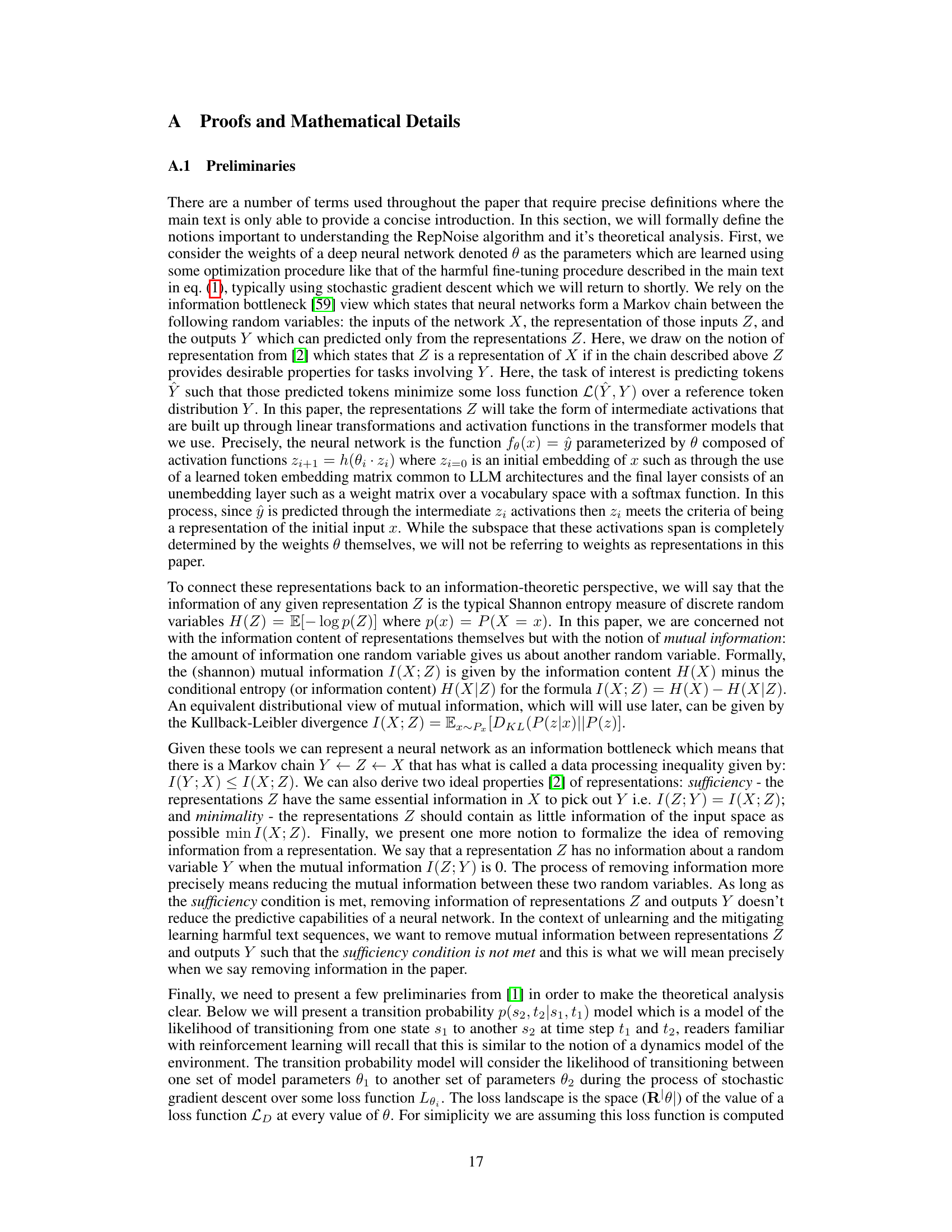

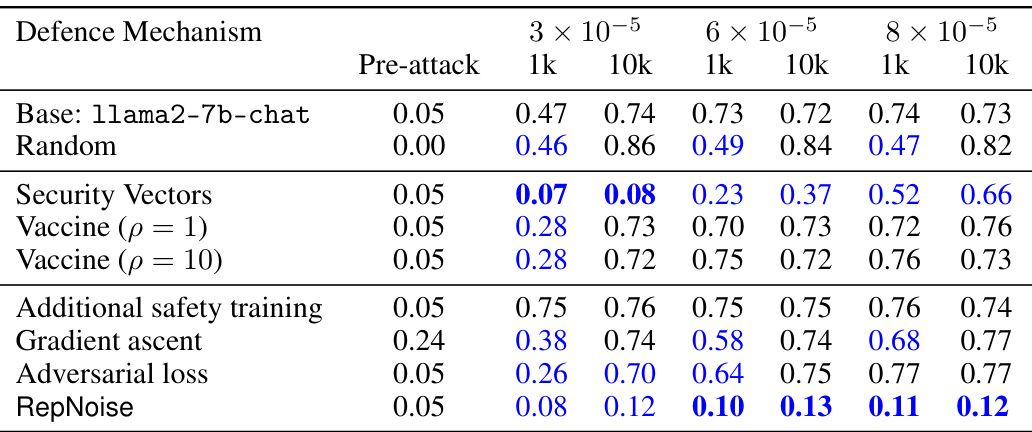

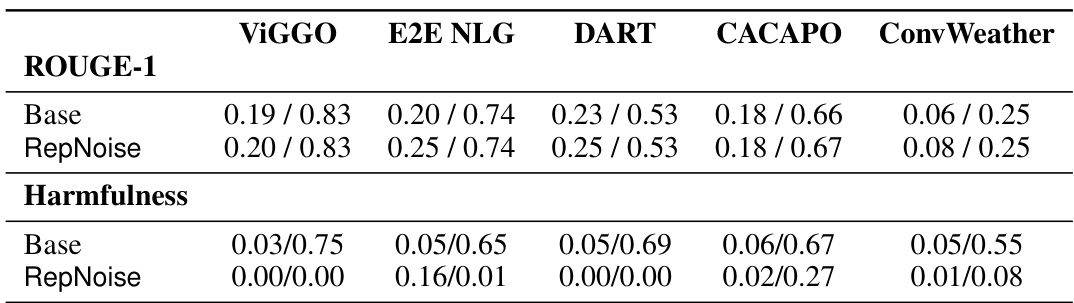

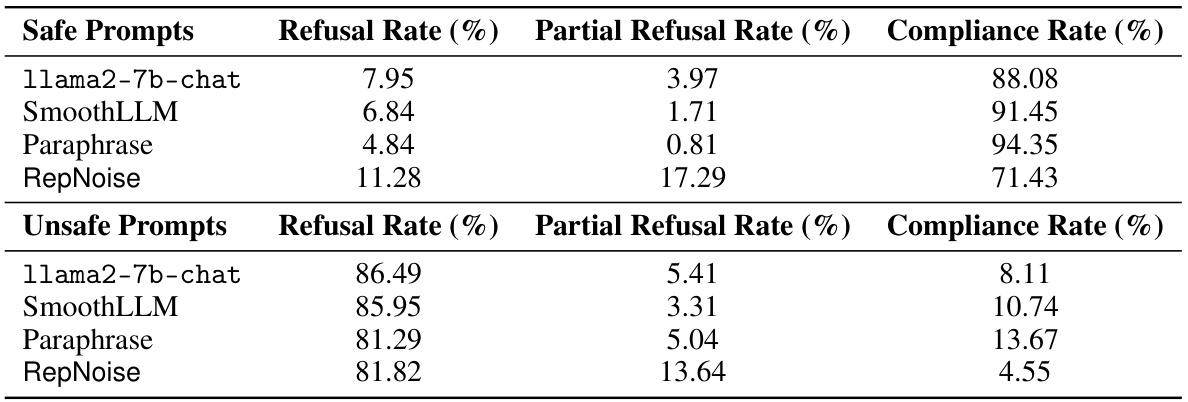

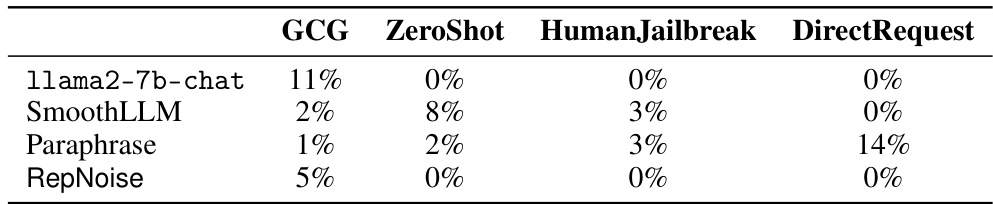

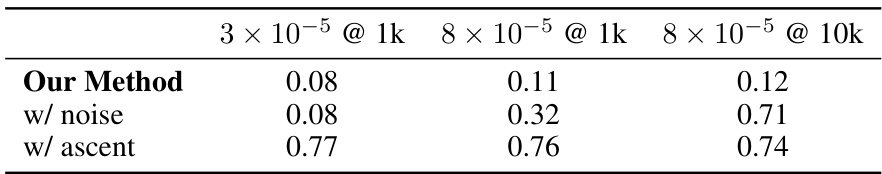

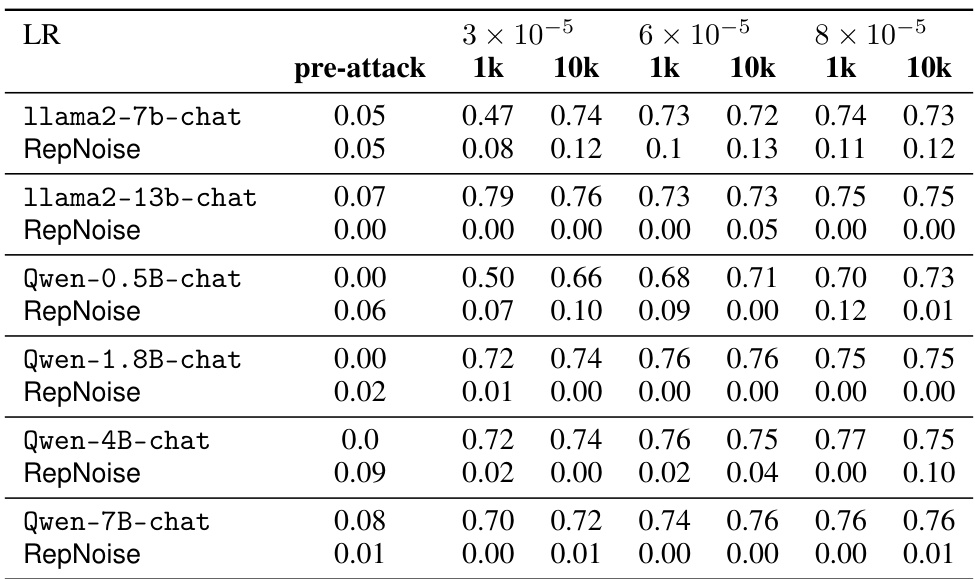

This table presents the results of harmful fine-tuning attacks on the llama2-7b-chat model and several defence mechanisms. The ‘Base’ row shows the harmfulness score of the original model before any attacks. The other rows show the harmfulness scores after attacks using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, with different learning rates and defence mechanisms applied. Lower scores indicate that the defence mechanism was successful in reducing the harmfulness of the model after attack.

In-depth insights#

RepNoise Defence#

The RepNoise defence mechanism, proposed for mitigating harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs) on large language models (LLMs), presents a novel approach focusing on representation manipulation rather than traditional safety guardrails. Instead of preventing harmful outputs directly, RepNoise works by altering the internal representations of harmful inputs within the model itself, making it significantly harder for attackers to recover and exploit these harmful patterns. Its efficacy is dependent on the depth of the modification, indicating a stronger impact when information about harmful representations is removed across all layers of the LLM. This novel method, unlike others that merely suppress or reroute harmful capabilities, aims to fundamentally alter harmful representations making HFAs considerably more challenging. A key aspect of RepNoise is its demonstrated ability to generalize across diverse types of harmful inputs, a feature particularly valuable given the ever-evolving nature of HFAs. However, the method’s sensitivity to hyperparameters and the potential for bypass with enough data and learning rate adjustments represent limitations which require further investigation. Despite these limitations, RepNoise introduces a promising paradigm shift in LLM defense, emphasizing the importance of fundamentally altering the underlying model architecture to bolster resilience against malicious fine-tuning.

HFA Mitigation#

HFA (Harmful Fine-tuning Attack) mitigation is a crucial area of research for large language models (LLMs). Current approaches often focus on improving safety guardrails or preventing access to model weights, but these measures are frequently circumvented by determined attackers. The paper proposes a novel defence mechanism, Representation Noising (RepNoise), that operates even when attackers have full access to model weights. Instead of simply trying to prevent harmful fine-tuning or block access to LLMs, RepNoise directly addresses the problem of malicious modifications by removing information about harmful representations from the model’s intermediate layers. This approach offers a new paradigm in LLM defense, shifting the focus from access control to information control. RepNoise’s effectiveness lies in its ‘depth’: removing the harmful information across all layers of the LLM significantly hinders the ability of attackers to fine-tune the model for malicious purposes. While the study shows promising results, further research is needed to address limitations, especially concerning generalization across different types of harmful tasks and the sensitivity to hyperparameter choices. Overall, the work highlights an important new direction in LLM security, potentially providing a more robust defense against evolving attack strategies.

Immunization Criteria#

The concept of “Immunization Criteria” in the context of defending large language models (LLMs) against harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs) is crucial. It establishes a framework for evaluating the effectiveness of any defense mechanism. The criteria likely involve resistance, meaning the defense significantly raises the cost for attackers in terms of time and computational resources to successfully perform an HFA. Stability ensures the defense doesn’t harm the LLM’s beneficial functionalities on safe tasks. Generalization is key, requiring that a defense effective against seen harmful data is also effective against unseen but similar types of harm. Finally, trainability is paramount; the defense shouldn’t hinder the LLM’s ability to learn from and improve on benign tasks. Meeting all four criteria suggests a robust defense capable of protecting LLMs from malicious fine-tuning while preserving their utility. The specific metrics used to measure each criterion would be highly model-specific and dependent on the targeted harms.

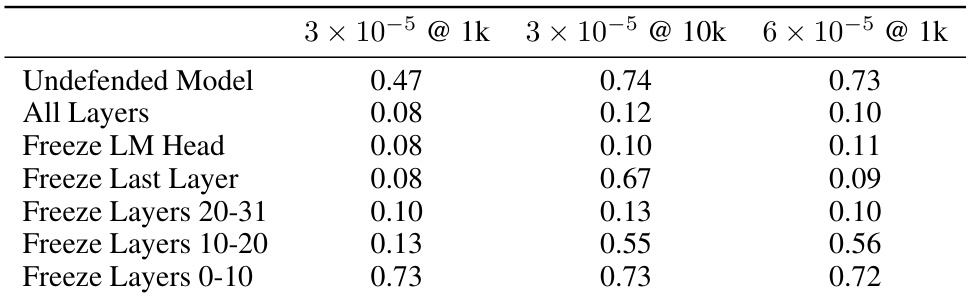

Depth of Defence#

The concept of “Depth of Defence” in the context of defending Large Language Models (LLMs) against harmful fine-tuning attacks is crucial. It highlights that superficial defenses, which primarily modify the output layer or a few top layers, are easily circumvented by attackers. A truly effective defense needs to be deep, impacting the internal representations throughout the model’s architecture. This is because harmful information can be encoded in lower layers, making it difficult to remove solely by altering the output. The effectiveness of techniques like Representation Noising hinges on their ability to remove harmful information across all layers, essentially immunizing the model’s core representations against malicious manipulation. The depth of the defense determines its resilience against attacks that target deeper layers. Therefore, future research on robust LLM defenses should focus on designing mechanisms that operate at various depths, ensuring comprehensive protection from a wide range of attack vectors. Evaluating defenses solely based on performance at the output layer is insufficient; a deeper understanding of how they affect representations across all layers is essential for developing genuinely effective and resilient defense strategies.

RepNoise Limits#

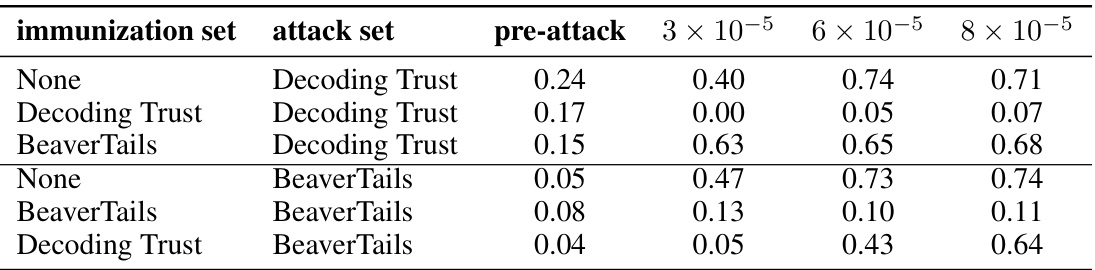

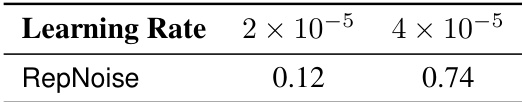

The effectiveness of RepNoise, a defense mechanism against harmful fine-tuning, is limited. Its performance is sensitive to hyperparameters, necessitating extensive tuning for optimal results. Higher learning rates and larger datasets can overcome RepNoise’s defenses, highlighting the need for more robust methods. The approach lacks generalization across different types of harmful tasks, proving effective only when defense and attack datasets share the same domain. Furthermore, RepNoise’s effectiveness is tied to the ‘depth’ of its operation, meaning modifications must spread throughout the neural network layers to effectively mitigate harmful representations. Superficial changes, focused on later layers, are less effective. Overall, RepNoise provides a valuable starting point, but further research is crucial to develop more robust and generalized defenses against harmful fine-tuning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

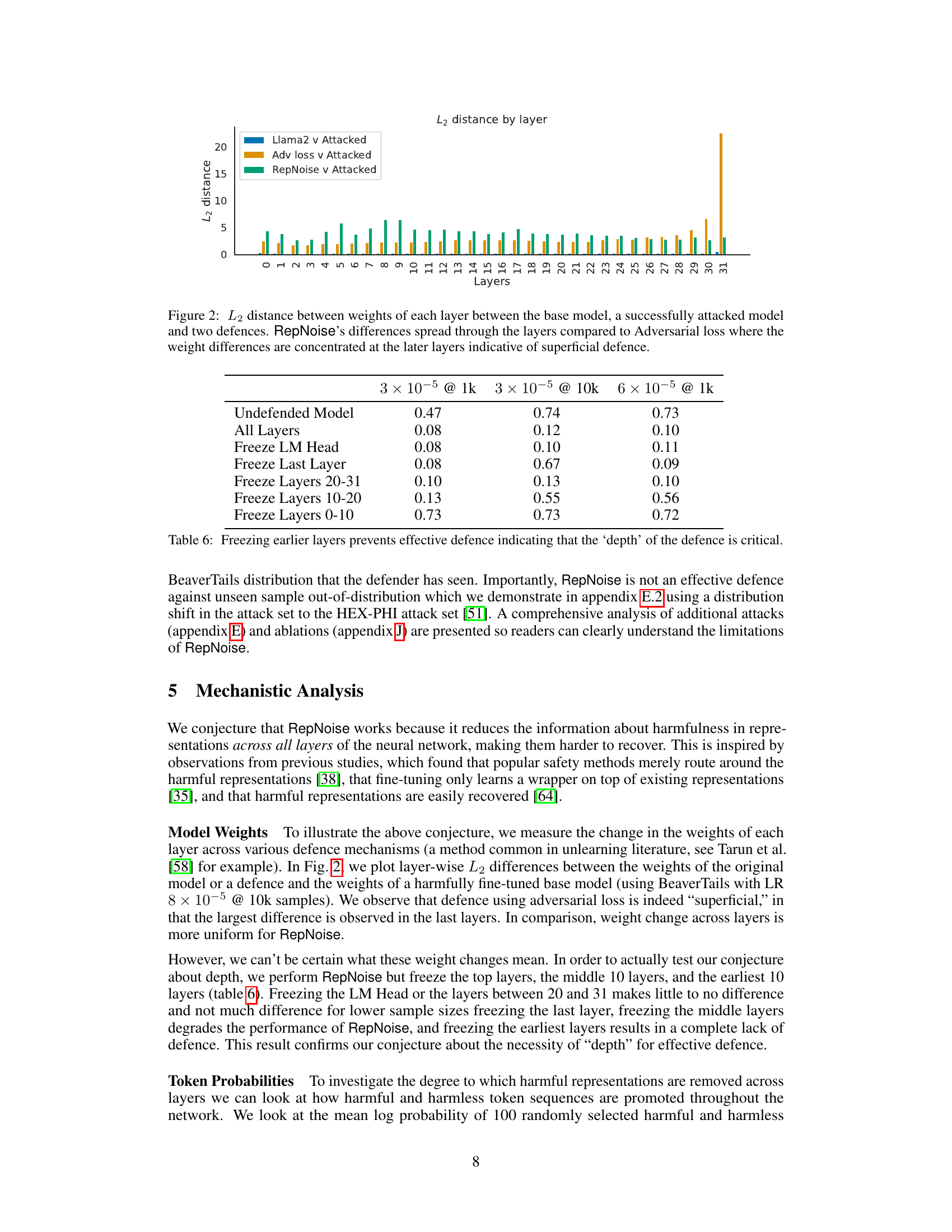

This figure shows the L2 distance between the weights of each layer in three different models: the base model, a successfully attacked model, and two defended models (using adversarial loss and RepNoise). The plot shows that the adversarial loss defence mainly affects the last few layers of the model, while RepNoise changes weights more uniformly across all layers. This suggests that the adversarial loss defense is a surface-level defense that does not affect the deep representations, while RepNoise affects the deep representations by spreading changes across the model’s layers. Thus, RepNoise appears to provide a more robust and effective defense against harmful fine-tuning.

This figure illustrates the core concept of Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how the method works by pushing intermediate activations (representations) of harmful text inputs toward random directions using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). By doing this, RepNoise reduces the mutual information between harmful representations and the original harmful text sequences, making it harder for attackers to reconstruct harmful representations during harmful fine-tuning attacks. The visualization highlights the loss of structure in the ‘Immunized Representations Z*’ after applying RepNoise.

This figure illustrates the core idea of Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how RepNoise modifies the intermediate activations (representations) of harmful text inputs within a neural network. Instead of directly altering the weights, RepNoise pushes the harmful representations towards random noise vectors, thus reducing the mutual information between these representations and the original harmful text. This makes it harder for an attacker to recover the harmful information during fine-tuning, even if they have access to the model’s weights. The visualization uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project high-dimensional representations into a 2D space, clearly showing that after RepNoise, the harmful representations lose their structure and become indistinguishable from random noise.

This figure illustrates the core idea behind Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how the method alters the intermediate activations (representations) of harmful text inputs within a neural network. Instead of directly modifying the weights, RepNoise pushes these harmful representations towards random noise, effectively reducing the information contained within them that could be used to perform harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs). The visualization uses principal component analysis (PCA) to show that the structure of the harmful representations is removed, making it difficult for attackers to recover them even if they have access to the model’s weights.

This figure illustrates the core idea behind Representation Noising (RepNoise). Harmful representations (Zharmful) in the original representations (Z) are pushed towards random noise, effectively removing their information content. This makes it harder for attackers to recover these harmful representations during harmful fine-tuning attacks. The figure uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize the effect, showing that harmful representations become indistinguishable from noise after RepNoise is applied.

This figure illustrates the mechanism of Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how RepNoise modifies the intermediate activations (representations) of harmful text inputs. By pushing these harmful representations towards random directions, RepNoise reduces the mutual information between the harmful representations and the corresponding harmful text sequences. This makes it difficult for attackers to recover the harmful representations through harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs). The PCA visualization demonstrates that the structure of the harmful representations is effectively removed after applying RepNoise.

This figure illustrates the core idea behind Representation Noising (RepNoise). It shows how RepNoise modifies the intermediate layer activations (representations) of harmful text inputs. Instead of directly altering the input or output, RepNoise pushes the harmful representations towards random noise vectors. This makes it difficult for an attacker to recover the original harmful representations during harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs), even if they have access to the model weights. The visualization uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to demonstrate the lack of discernible structure in the modified (immunized) representations, emphasizing that harmful information is effectively removed.

This figure illustrates the RepNoise defense mechanism. It shows how the method pushes harmful representations (intermediate activations of harmful text inputs) towards random directions, thereby reducing the mutual information between these harmful representations and the harmful text sequences. The result is that it becomes difficult to recover the harmful representations during harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs). The visualization uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to show that no structure remains after the RepNoise process, making it difficult for attackers to leverage this information during the HFAs.

More on tables

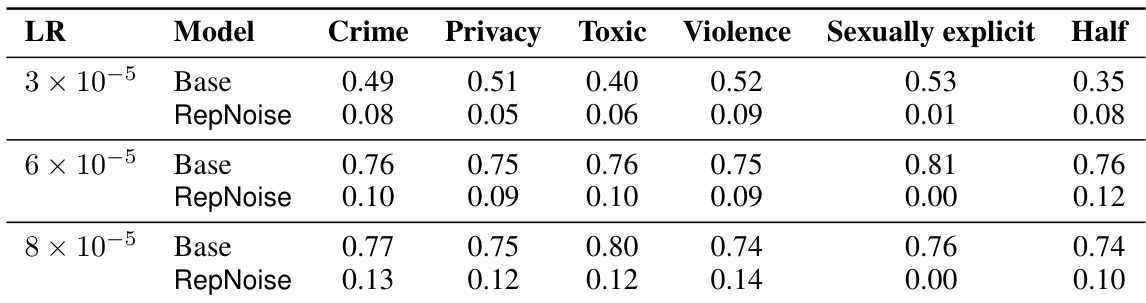

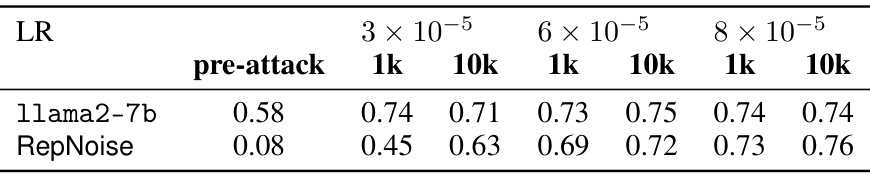

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the effectiveness of different defense mechanisms against harmful fine-tuning attacks on a toxic content generation task. The ‘pre-attack’ column shows the initial toxicity scores before any attack. The remaining columns represent toxicity scores after attacks performed with different learning rates (3×10−5, 6×10−5, 8×10−5), each using 1k and 10k samples from a harmful dataset. Each row indicates a different defense method (RepNoise, Security Vectors, Vaccine, Gradient Ascent, Adversarial loss), and the scores indicate the mean toxicity scores obtained from the Perspective API. Lower scores indicate better defence performance, showing that RepNoise demonstrates significant resistance compared to the base model and other defence strategies.

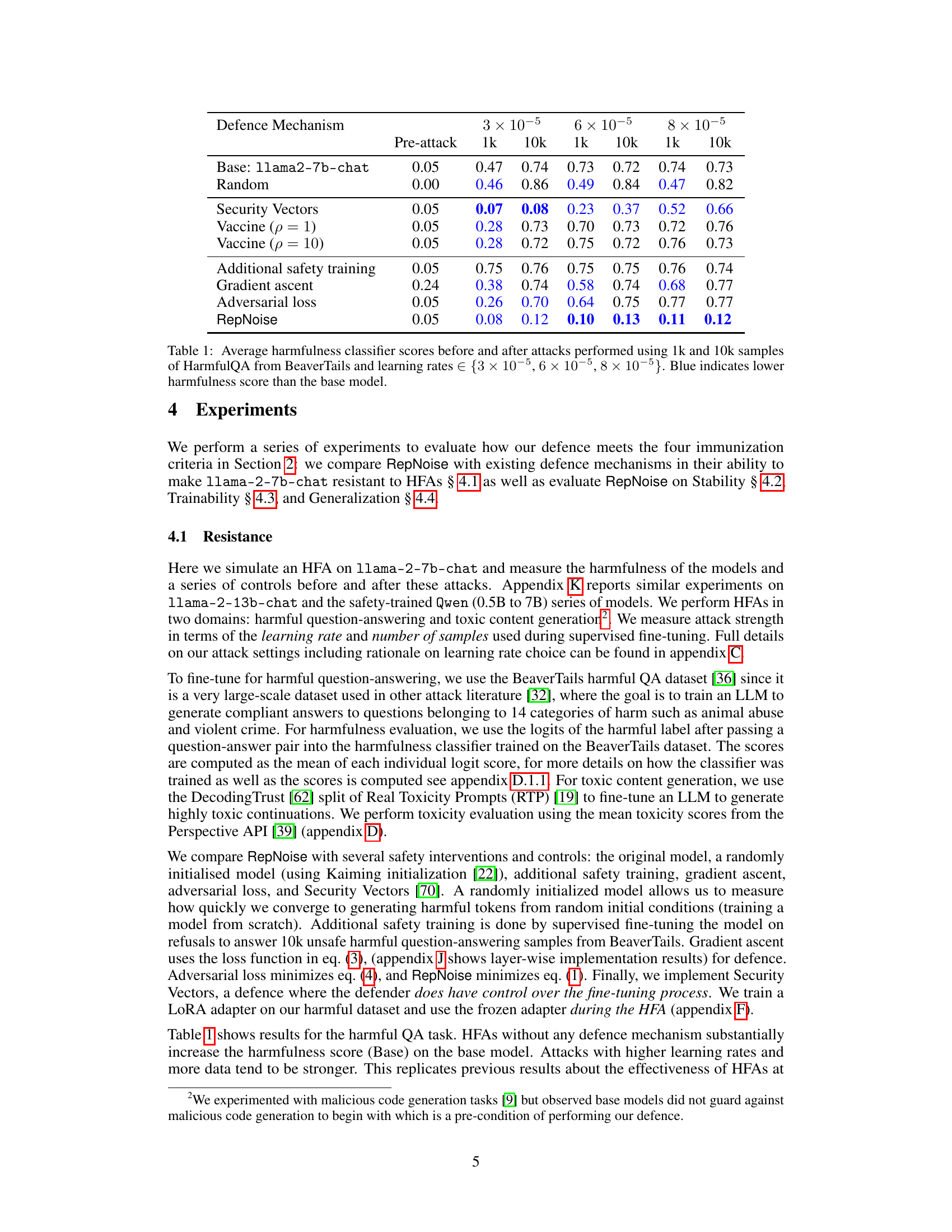

This table shows the results of evaluating the RepNoise model on several common language model benchmarks including TruthfulQA, MMLU, Hellaswag, Winogrande, ARC, Ethics, and CrowS-Pairs. The scores indicate that the RepNoise model does not significantly degrade the model’s overall capabilities after the application of the RepNoise defence. This demonstrates that the RepNoise method preserves the general capabilities of the language model while mitigating the risk of harmful fine-tuning.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores obtained before and after performing several attacks on the llama2-7b-chat model. The attacks vary in the number of samples used (1k or 10k) from the HarmfulQA dataset and in the learning rate applied (3 × 10−5, 6 × 10−5, and 8 × 10−5). Various defense mechanisms are compared, including random initialization, security vectors, additional safety training, and the proposed RepNoise method. Lower scores in blue indicate better defense performance than the base (unattacked) model. The results show that RepNoise consistently achieves lower harmfulness scores compared to other defense mechanisms across different attack strengths.

This table shows the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after performing harmful fine-tuning attacks (HFAs) using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset. The attacks vary the learning rate used in the fine-tuning process. Blue coloring highlights cases where a defense mechanism resulted in lower harmfulness scores than the base model. This illustrates the effectiveness of the different defense mechanisms against HFAs of varying strength.

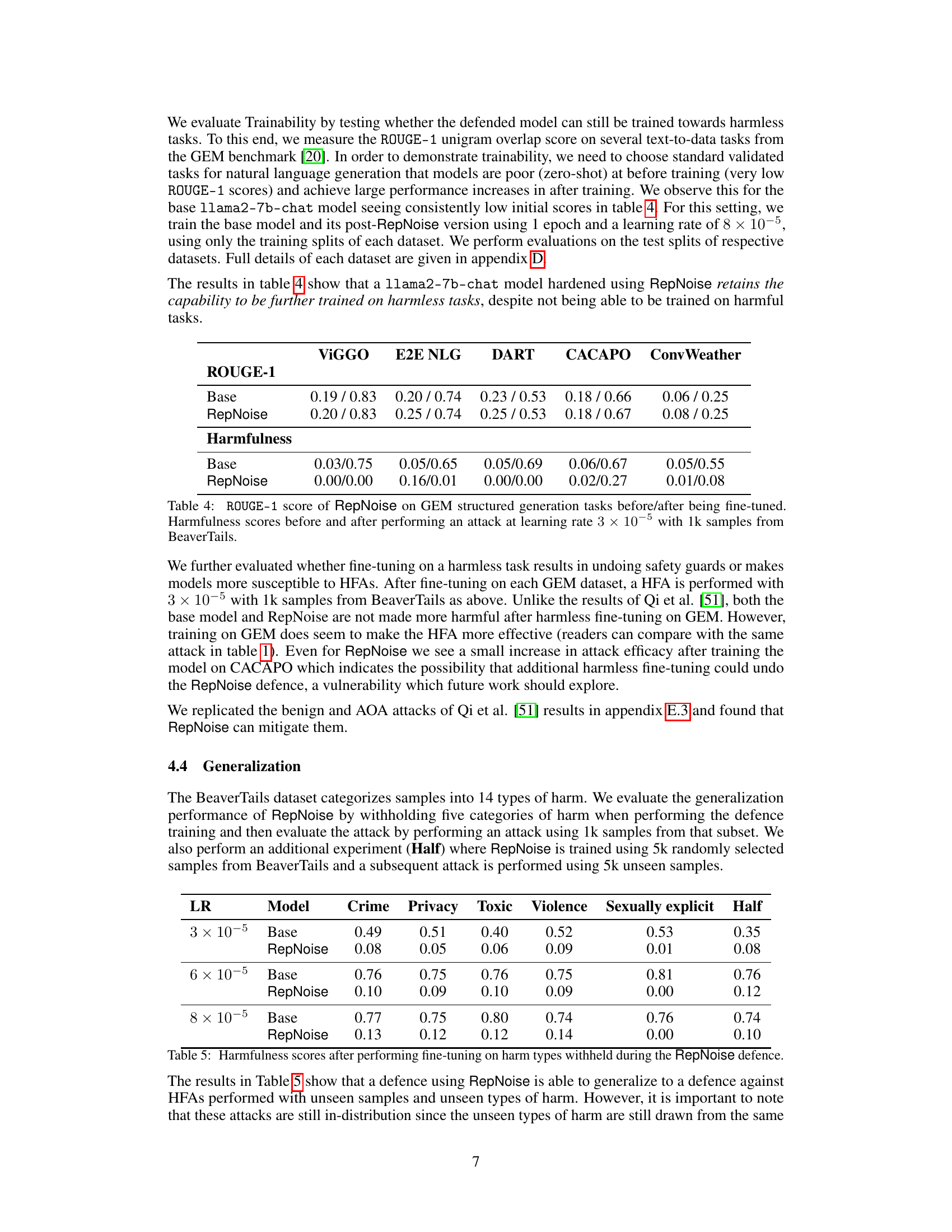

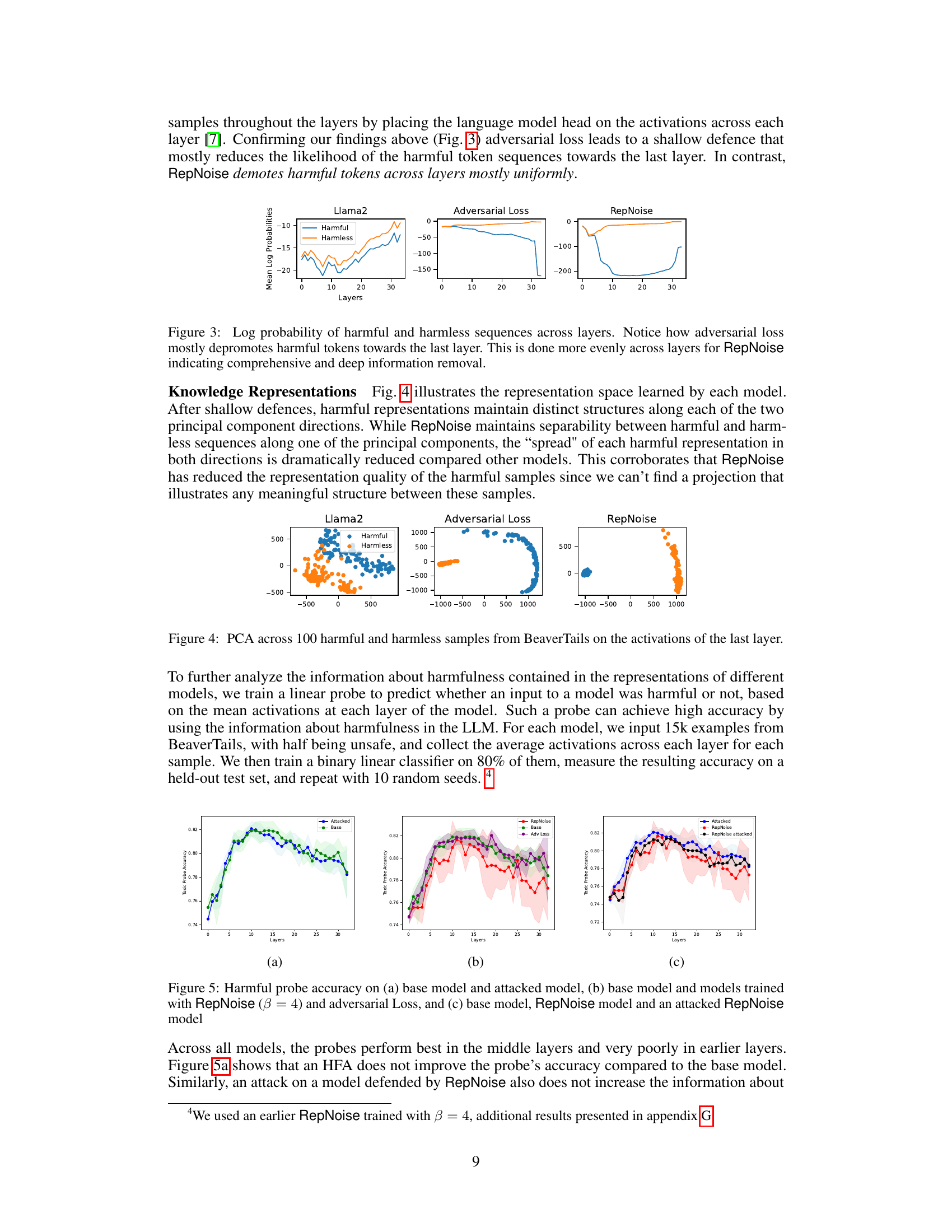

This table shows the results of an ablation study where different layers of the language model were frozen during the training process of RepNoise. The results show that freezing earlier layers in the model significantly reduces the effectiveness of RepNoise, highlighting the importance of ‘depth’—the degree to which information about harmful representations is removed across all layers—in achieving effective defence.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after a harmful fine-tuning attack. The attack uses 1,000 and 10,000 samples from the HarmfulQA dataset with three different learning rates. Lower scores indicate lower harmfulness, and blue highlighting shows when a defense mechanism performed better than the base model.

This table shows the average harmfulness classifier scores for different defense mechanisms before and after performing harmful fine-tuning attacks. The attacks used 1,000 and 10,000 samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, with three different learning rates. Lower scores indicate lower harmfulness. The base model is compared to several defense mechanisms, including random initialization, additional safety training, gradient ascent, adversarial loss, and security vectors.

This table presents the results of a cross-domain generalization experiment. It shows the average harmfulness scores (as measured by a classifier) before and after attacks with various learning rates. The experiments involve training RepNoise on one dataset and testing it on another, to determine its ability to generalize across different domains. The table includes rows for different combinations of immunization and attack datasets (Decoding Trust and BeaverTails), showing the effect of training on one dataset and testing on another on the resulting harmfulness scores.

This table shows the average harmfulness scores (using a harmfulness classifier) for the llama2-7b-chat model before and after several attacks (harmful fine-tuning attacks using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset). It compares the base model to several defence mechanisms, including RepNoise, against these attacks. Lower scores indicate lower harmfulness. The attacks are performed with three different learning rates. The results show that RepNoise is the only defence method that consistently provides significant resistance against all attacks, even with 10k samples.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after performing harmful fine-tuning attacks using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset. The attacks were performed using three different learning rates. Lower scores indicate lower harmfulness.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama-2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after harmful fine-tuning attacks. The attacks used 1,000 and 10,000 samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, with three different learning rates. Lower scores indicate better defense against the attacks.

This table shows the results of an ablation study where different layers of the language model were frozen during the training of the RepNoise defence. The results show that freezing earlier layers significantly reduces the effectiveness of the defence. This suggests that the effectiveness of RepNoise depends on its ability to remove information about harmful representations across all layers of the model, rather than just the final layers. The ‘depth’ of the defence (how many layers are affected) appears critical for effectiveness.

This table presents the results of harmful fine-tuning attacks on the llama-2-7b-chat model with different defense mechanisms. It shows the average harmfulness classifier scores before and after attacks using 1,000 and 10,000 samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, with three different learning rates. The base model’s scores are compared against those of models with different defenses applied (Random, Security Vectors, Vaccine, Additional safety training, Gradient Ascent, Adversarial loss, and RepNoise), showing the effectiveness of each defense in mitigating harmful fine-tuning attacks.

This table shows the average harmfulness classifier scores before and after a harmful fine-tuning attack was performed on the llama2-7b-chat model. The attacks used 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset of BeaverTails, with three different learning rates. The table compares the base model’s performance to several defense mechanisms, including RepNoise. Lower scores indicate lower harmfulness.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of the learning rate used during the RepNoise defence. It shows that even small increases in the learning rate from 2 × 10⁻⁵ to 4 × 10⁻⁵ significantly reduce the effectiveness of RepNoise against harmful fine-tuning attacks, highlighting the sensitivity of the defence to this hyperparameter. The attack used for this experiment was an 8 × 10⁻⁵ @ 10k sample attack.

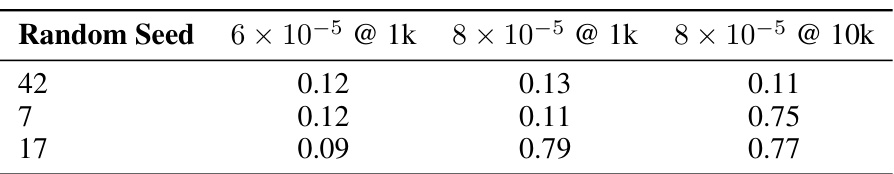

This table shows the average harmfulness classifier scores for different random seeds used during the RepNoise defense. It demonstrates the sensitivity of RepNoise to the random seed, highlighting a limitation of the method. The results indicate that even small changes to the random seed can significantly alter the effectiveness of the defense, underscoring the importance of considering this factor in future research and practical applications.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores (lower is better) for the base llama2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after attacks using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset. The attacks varied the learning rate. The results show the effectiveness of each defense mechanism against the attacks.

This table presents the results of harmful fine-tuning attacks on the llama-2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms. The ‘harmfulness score’ is a metric measuring how harmful a model’s responses are. The table shows the average harmfulness score before any attack (pre-attack), and after attacks with different strengths (1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, and three different learning rates). The results are presented for the base model (llama2-7b-chat), and several defense methods. The table shows that the base model’s harmfulness score increases significantly after the attacks, while the RepNoise defense method effectively reduces the harmfulness score, highlighting its effectiveness against harmful fine-tuning attacks.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama-2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after a harmful fine-tuning attack. The attack used 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA subset of the BeaverTails dataset with three different learning rates. Lower scores indicate that the defense mechanism was successful in mitigating the harmful fine-tuning attack.

This table presents the results of harmful fine-tuning attacks on various defense mechanisms, including RepNoise. The table shows the average harmfulness classifier scores before and after attacks. The attacks were performed using 1,000 and 10,000 samples from the HarmfulQA dataset, with three different learning rates. The base model is compared against various defense methods, and the lower the harmfulness score after the attack, the more effective the defense is.

This table presents the average harmfulness classifier scores for the base llama-2-7b-chat model and several defense mechanisms before and after a harmful fine-tuning attack using 1k and 10k samples from the HarmfulQA dataset of BeaverTails. The attacks were performed with three different learning rates (3e-5, 6e-5, 8e-5). Lower scores indicate better defense performance against the harmful attacks.

Full paper#