↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Vision-Language Models (VLMs) struggle with generalization when faced with challenging examples. Episodic Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) is a powerful technique to enhance VLM performance by adapting them during testing. Existing methods, like prompt tuning by Marginal Entropy Minimization (MEM), are computationally expensive.

This paper introduces ZERO, a novel TTA method that leverages a hidden property within MEM. ZERO is incredibly simple: it augments the input image multiple times, makes predictions, keeps the most confident ones, and then sets the softmax temperature to zero before marginalizing. This requires only a single forward pass, making it much faster and more memory-efficient than existing TTA methods. Experiments show that ZERO outperforms state-of-the-art approaches on various datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in Vision-Language Models (VLMs) and Test-Time Adaptation (TTA). It introduces ZERO, a surprisingly simple yet highly effective TTA method that significantly outperforms existing approaches while being significantly faster and more memory-efficient. The simplicity of ZERO makes it a strong baseline for future work and opens new avenues for research in efficient model adaptation.

Visual Insights#

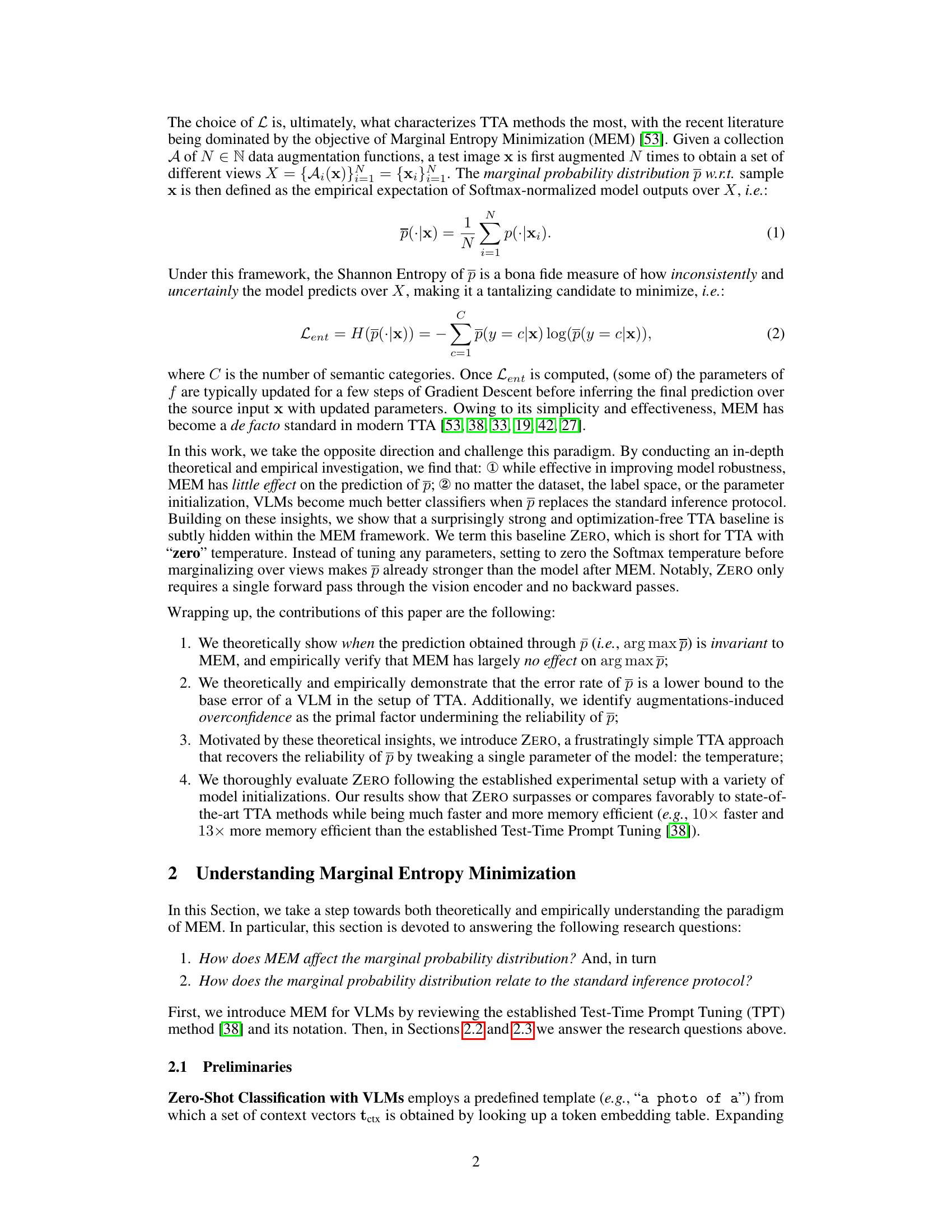

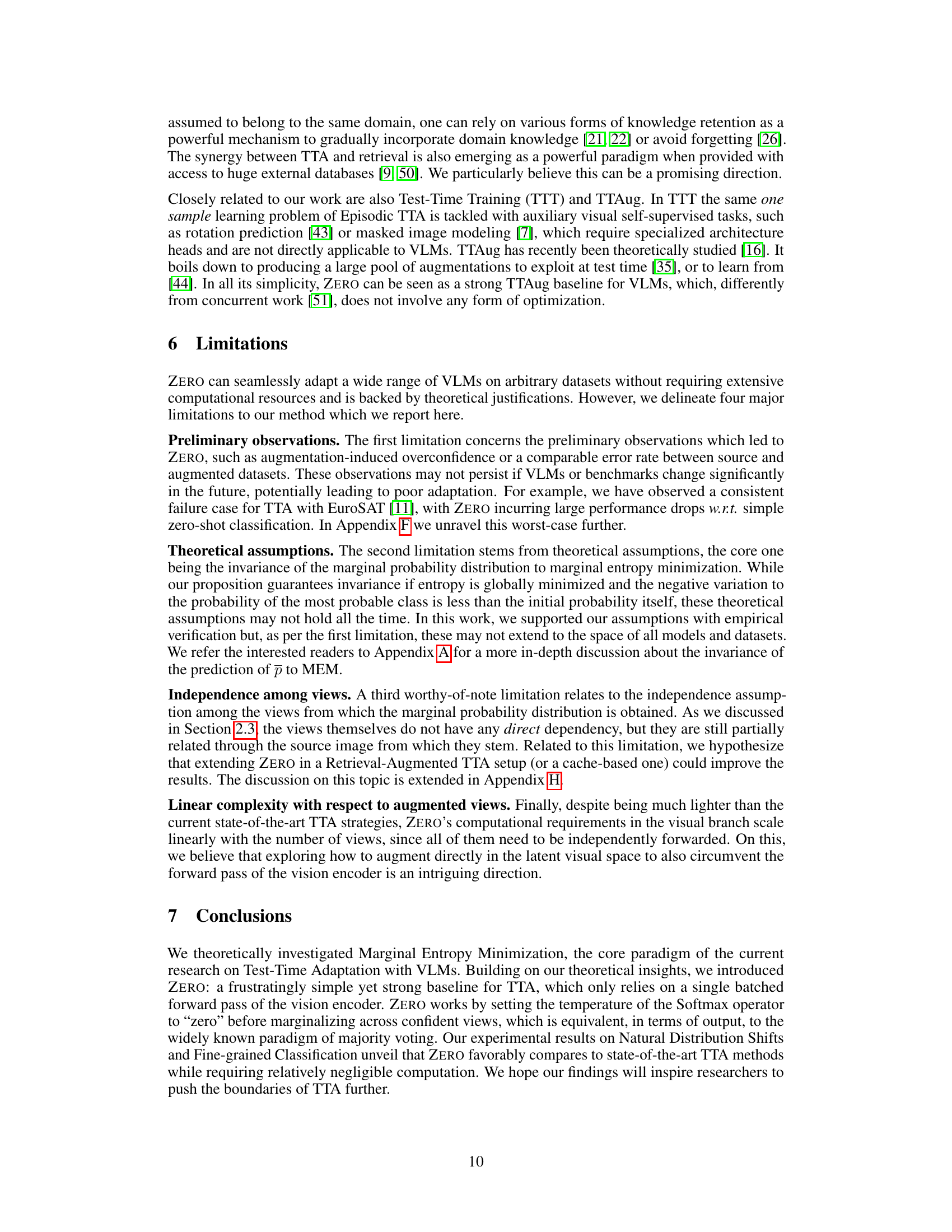

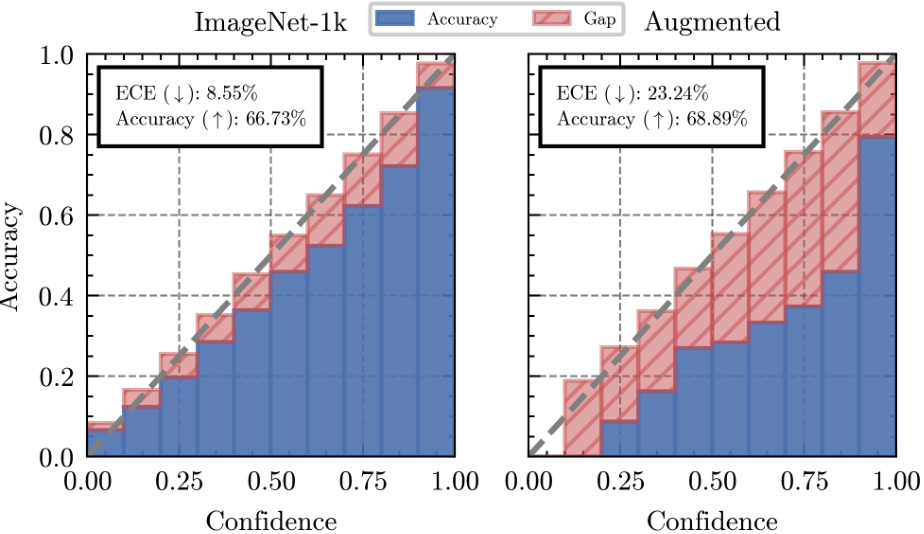

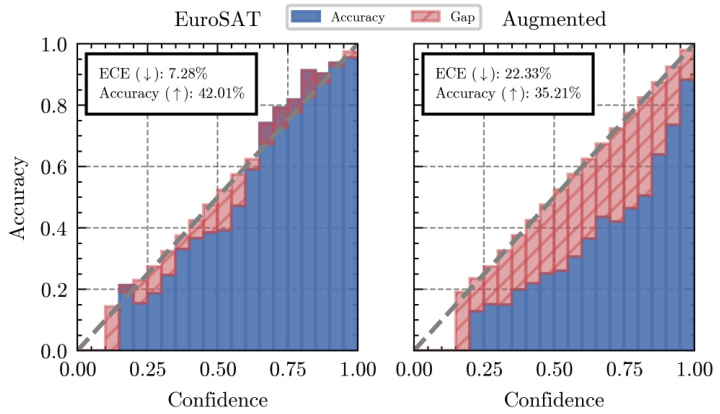

This figure presents two key findings. The first is a comparison of the expected error of the CLIP-ViT-B-16 model with the error of its marginal probability distribution, demonstrating that the latter provides a lower bound to the former. The second part shows reliability diagrams for both the original and augmented versions of the ImageNet dataset, illustrating that while augmentations may improve overall accuracy, they also tend to lead to overconfidence and reduced calibration.

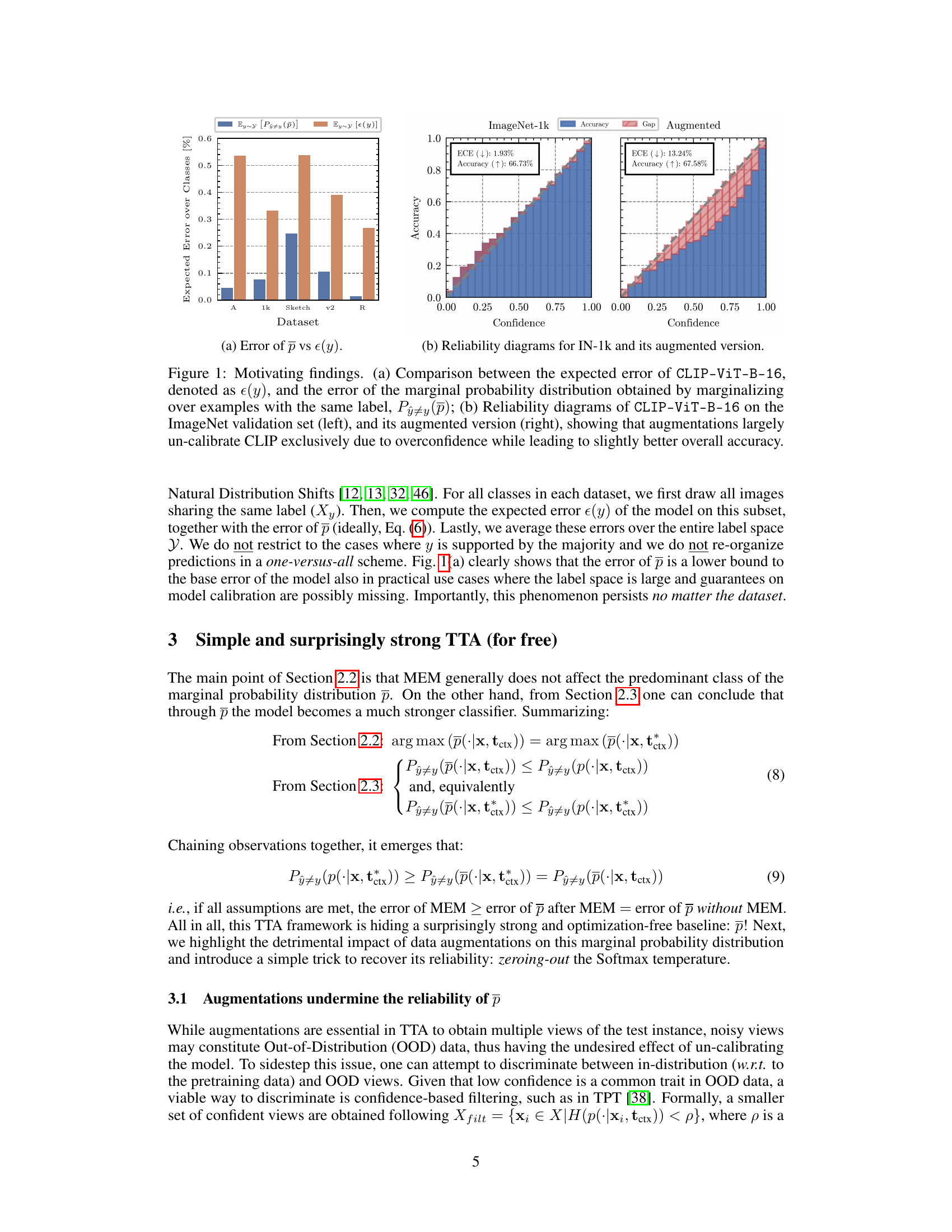

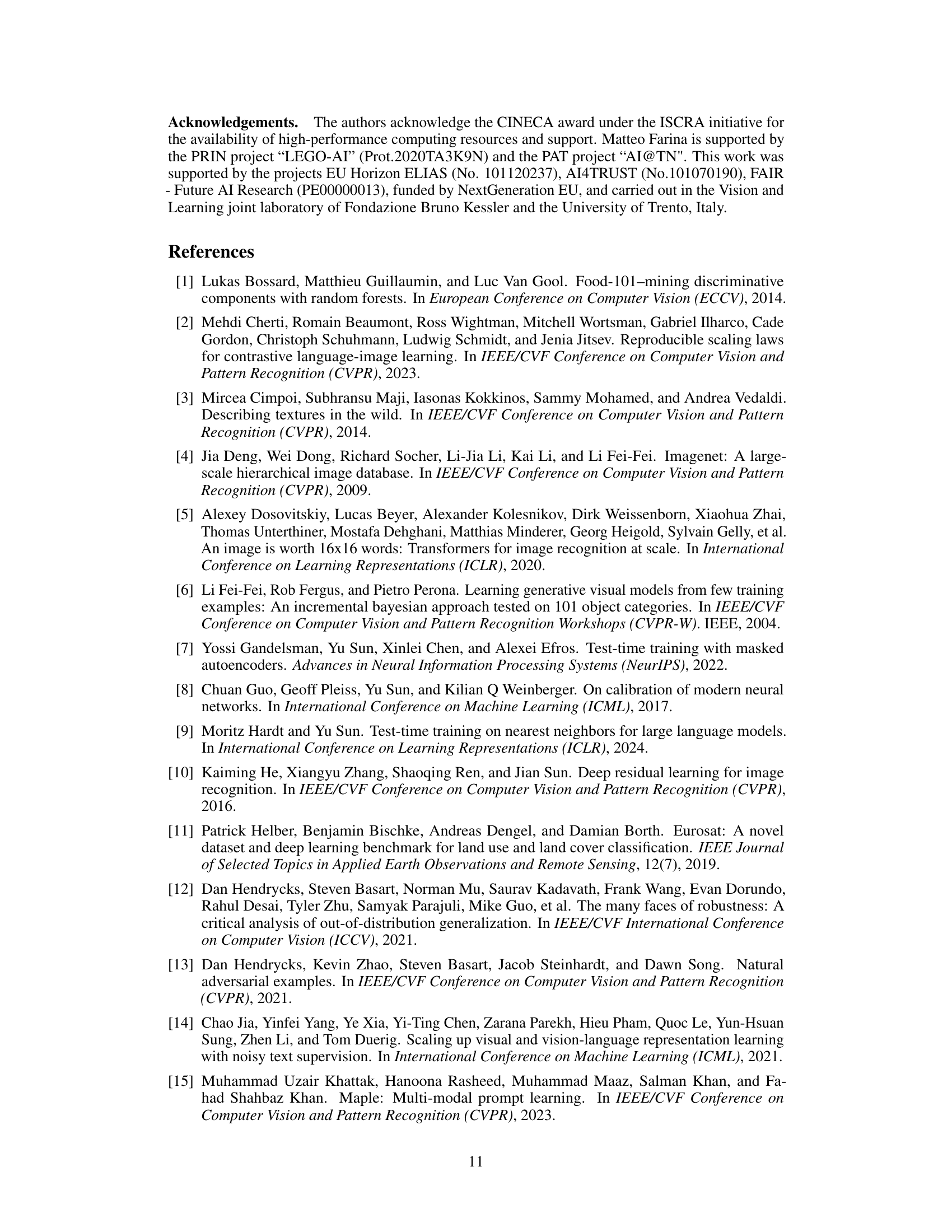

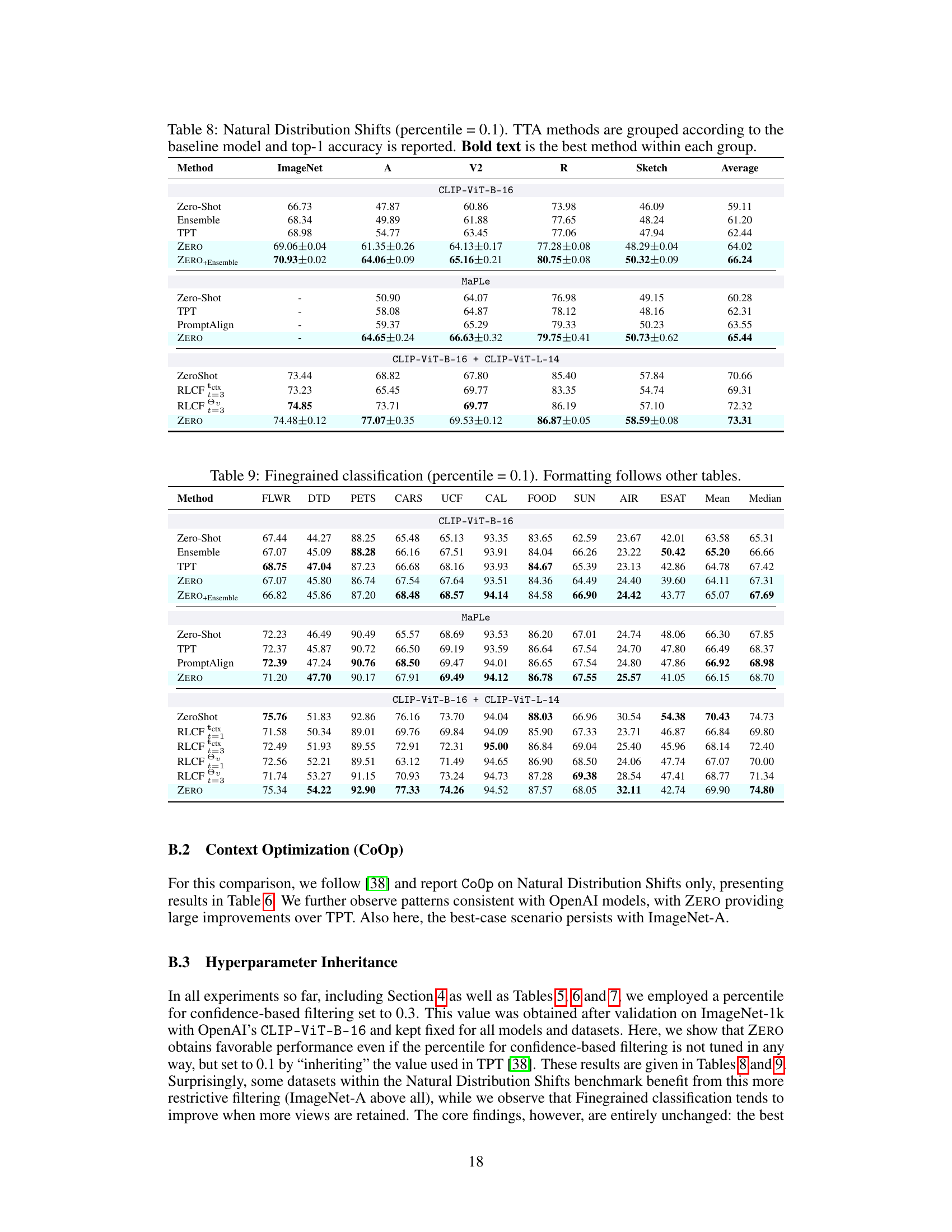

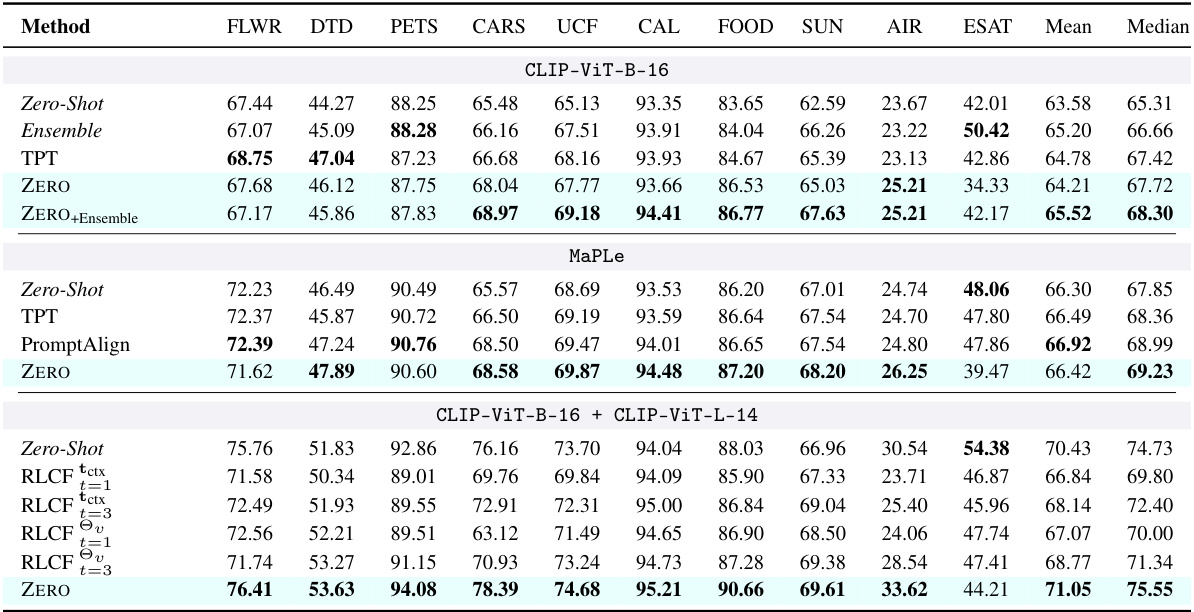

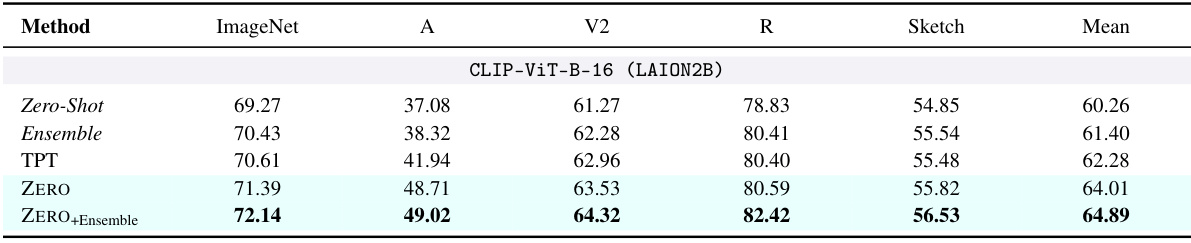

This table presents the results of the proposed ZERO method and three other Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods on various datasets representing natural distribution shifts. The methods are grouped by the baseline vision-language model used (CLIP-ViT-B-16, MaPLe, and CLIP-ViT-B-16 + CLIP-ViT-L-14). Top-1 accuracy is reported for each dataset and method, showing how well each method adapts to these challenging, out-of-distribution datasets. The best performing method within each group is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

ZERO: A Novel TTA#

The proposed method, ZERO, offers a novel approach to Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) by leveraging the marginal probability distribution of model predictions over augmented views. ZERO’s key innovation lies in its simplicity: it eliminates the need for online backpropagation and parameter updates, making it significantly faster and more memory-efficient than existing TTA methods. This is achieved by marginalizing the model outputs after setting the softmax temperature to zero, effectively selecting the most confident prediction. The theoretical analysis provides insights into ZERO’s effectiveness by demonstrating that the marginal probability distribution itself already serves as a strong classifier that’s largely unaffected by entropy minimization. Empirically, ZERO consistently outperforms state-of-the-art TTA methods while exhibiting remarkable computational efficiency. However, ZERO’s performance is sensitive to the reliability of augmentation techniques, highlighting the importance of carefully selecting augmentation strategies to maintain model calibration. Despite its simplicity, ZERO offers a strong baseline for future TTA research and underscores the significance of evaluating simple, computationally efficient baselines.

MEM’s Hidden Power#

The heading “MEM’s Hidden Power” suggests an investigation into the underappreciated potential of Marginal Entropy Minimization (MEM) in vision-language models. The authors likely demonstrate that MEM, while commonly used for test-time adaptation (TTA), achieves surprisingly strong results through a simpler, more efficient approach they term ZERO. ZERO leverages the core idea of MEM but eliminates the need for online backpropagation, leading to significantly faster inference and reduced memory consumption. This implies that the computationally expensive optimization steps inherent in traditional MEM-based TTA may be unnecessary, a key finding that challenges existing paradigms. The analysis likely provides both theoretical justifications and empirical evidence demonstrating that ZERO often surpasses state-of-the-art TTA methods, highlighting a previously unrecognized strength of MEM and offering a novel, computationally efficient baseline for future research in TTA for vision-language models.

Augmentation Effects#

Data augmentation, a cornerstone of modern machine learning, presents a complex interplay of benefits and drawbacks, especially within the context of test-time adaptation (TTA). While augmentations are crucial for creating diverse training data and improving model robustness, their effect during test-time adaptation needs careful consideration. Overconfidence is a significant concern, where augmentations can lead to inflated confidence scores in model predictions that aren’t necessarily accurate. This makes it more difficult to rely solely on the model’s confidence estimates when choosing among augmented views of a test instance. Additionally, augmentations can introduce noise or lead to out-of-distribution (OOD) samples. The optimal selection strategy for leveraging augmentations during TTA isn’t merely a matter of simply augmenting N times and averaging, but demands careful consideration of how to filter unreliable views and avoid misleading the model’s decision process. Therefore, a robust TTA strategy requires not just diverse augmentations, but also mechanisms to assess augmentation quality and mitigate the detrimental effects of overconfidence and noise.

TTA’s Limitations#

Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods, while offering compelling advantages for improving model robustness, face inherent limitations. A primary concern is the reliance on data augmentation, which, while effective in generating diverse views, can introduce noise or even out-of-distribution samples, leading to unreliable predictions and potentially degrading model calibration. The effectiveness of TTA is also heavily dependent on the specific model architecture and the nature of the data distribution. Methods effective in one domain may not generalize well to others. Furthermore, many TTA methods introduce computational overhead, slowing inference significantly; this is often seen in approaches using online backpropagation. Ensuring sufficient diversity in augmented views without excessive computational cost or introducing overconfidence presents a major challenge. Finally, a thorough theoretical analysis is needed to understand the conditions under which TTA can guarantee consistent improvements across diverse scenarios, addressing fundamental assumptions and limitations that can affect prediction reliability.

Future of TTA#

The future of Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) hinges on addressing its current limitations. Improving efficiency is crucial; methods like ZERO, while effective, still require multiple forward passes. Future work should explore latent-space augmentation and efficient mechanisms to select the most informative augmented views. Theoretical advancements are also needed, specifically in relaxing assumptions about data independence among augmented views. Research into better calibration techniques will be vital for reliable predictions. Finally, exploring the synergy between TTA and retrieval from external knowledge bases offers exciting possibilities to improve generalization capabilities further.

More visual insights#

More on figures

Figure 1(a) compares the expected error rate of a standard CLIP model (e(y)) against the error rate of a model that uses the marginal probability distribution (p) obtained from multiple augmented views of the input image. The results show that the error rate of p lower-bounds e(y), indicating that using the marginal probability improves performance. Figure 1(b) illustrates the reliability diagrams, comparing the confidence levels of the model predictions against their actual accuracy. The original model shows good calibration, but when augmentations are used, overconfidence significantly increases despite minimal improvement in overall accuracy.

This figure shows the relationship between the entropy of the pre-Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) marginal probability distribution and the invariance ratio. The invariance ratio measures how often the arg max of the pre-TTA marginal probability distribution remains unchanged after applying Marginal Entropy Minimization (MEM). The figure demonstrates a trend where as the entropy decreases (less uncertainty), the invariance ratio increases (the arg max is more likely to remain unchanged after MEM). Even within the top 10% of most uncertain samples, invariance holds more than 82% of the time.

Figure 1(a) shows that the error of the marginal probability distribution p is always lower than the expected error of the model, even in practical use cases where the label space is large. Figure 1(b) shows that augmentations largely un-calibrate the model due to overconfidence.

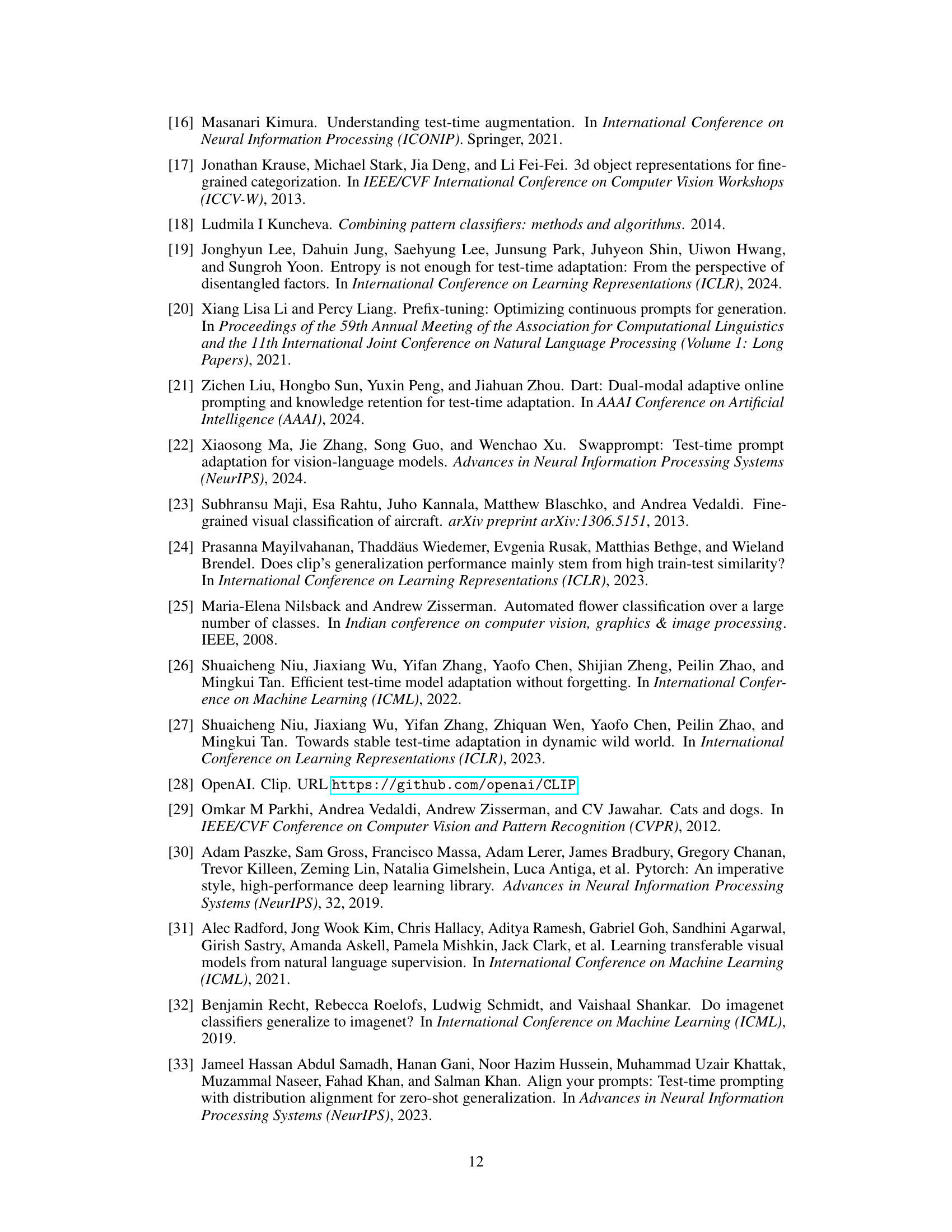

This figure displays reliability diagrams for CLIP-ViT-B-16 on four datasets known for their distribution shifts from ImageNet. Each row shows two diagrams: one for the original dataset and one for an augmented and filtered version. The diagrams visualize the model’s calibration by plotting accuracy against confidence for various confidence intervals. The Expected Calibration Error (ECE) is also indicated for both versions in each dataset. It illustrates the impact of augmentations on model calibration, specifically showing a significant increase in overconfidence after augmentation.

Figure 1(a) compares the error rate of standard inference with the error rate of using the marginal probability distribution (p). It shows that the error rate of p is lower than standard inference’s error rate. Figure 1(b) uses reliability diagrams to illustrate how augmentations affect the model. It highlights that while augmentations improve overall accuracy, they make the model’s confidence scores unreliable (overconfident).

This figure shows the reliability diagrams of CLIP-ViT-B-16 on four datasets for natural distribution shifts (ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, and ImageNet-Sketch). Each row displays the Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and accuracy for both the original dataset (left) and an augmented and filtered version of the dataset (right). The diagrams visually represent the model’s calibration, showing how well the model’s predicted confidence aligns with its actual accuracy. The comparison highlights the impact of augmentations on the model’s calibration.

This figure shows examples of satellite images and their augmentations used in the experiment. The augmentations are simple random resized crops and horizontal flips. The figure displays three examples of satellite images with their ground truth labels. For each image, three augmented views are presented, sorted by the confidence of CLIP-ViT-B-16’s prediction. The goal is to illustrate how these augmentations impact the model’s predictions and confidence.

More on tables

This table presents the results of the Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods on datasets representing natural distribution shifts. The table is organized by the Vision-Language Model (VLM) used as the base model (CLIP-ViT-B-16, MaPLe, and CLIP-ViT-B-16 + CLIP-ViT-L-14). Within each group, different TTA methods are compared (Zero-Shot, Ensemble, TPT, ZERO, ZERO+Ensemble, MaPLe, PromptAlign, RLCF). The top-1 accuracy is reported for each method and dataset (ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, ImageNet-Sketch). The best performing method within each group is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of the Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods on various datasets representing natural distribution shifts. The table is organized by the Vision-Language Model (VLM) used as a baseline for each TTA method (CLIP-ViT-B-16, MaPLe, CLIP-ViT-B-16 + CLIP-ViT-L-14). For each VLM, several TTA methods are evaluated (Zero-Shot, Ensemble, TPT, ZERO, ZERO+Ensemble, MaPLe, PromptAlign, RLCF variants). The top-1 accuracy is reported for each method and dataset. Bold text indicates the best performing method within each group of similar baseline models. The datasets used include ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, and ImageNet-Sketch. The table helps quantify the performance improvement achieved by different TTA approaches over a standard zero-shot baseline and allows for comparison among various TTA techniques.

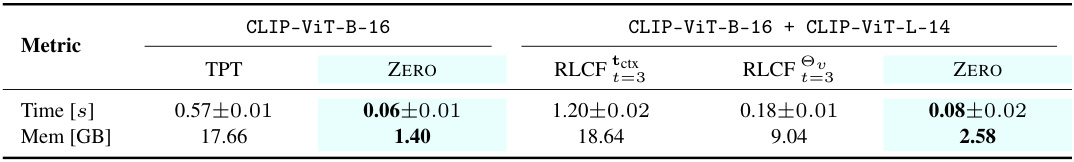

This table compares the computational requirements (runtime and memory usage) of different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods for vision-language models. It shows that the proposed ZERO method is significantly faster and more memory-efficient than existing methods like Test-Time Prompt Tuning (TPT) and Reinforcement Learning from CLIP Feedback (RLCF).

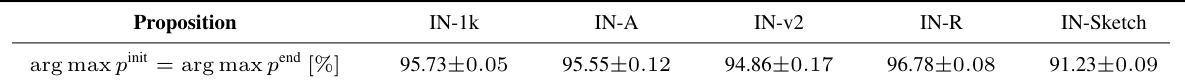

This table presents empirical evidence supporting Proposition 2.1, which states that the prediction of the marginal probability distribution (p) is invariant to Marginal Entropy Minimization (MEM). The table shows the percentage of times that the arg max of the pre-TTA marginal probability distribution (pinit) equals the arg max of the post-TTA marginal probability distribution (pend) across five datasets: ImageNet-1k, ImageNet-A, ImageNet-v2, ImageNet-R, and ImageNet-Sketch. The results show that, in most cases, the prediction of p remains unchanged after MEM.

This table presents the results of the Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods on five datasets representing natural distribution shifts. The methods compared include Zero-Shot, Ensemble, Test-Time Prompt Tuning (TPT), ZERO, and ZERO+Ensemble. The results highlight the performance of each method compared to a standard zero-shot baseline and the improvement achieved by ZERO, especially when using an ensemble of prompts.

This table presents the results of Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) experiments using OpenAI’s CLIP-ViT-B-16 model with prompts learned using Context Optimization (Coop). The performance of three TTA methods (Zero-Shot, TPT, and ZERO) is evaluated on five datasets representing natural distribution shifts (ImageNet, ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, and ImageNet-Sketch). The table shows the top-1 accuracy achieved by each method on each dataset, highlighting the best performing method in bold.

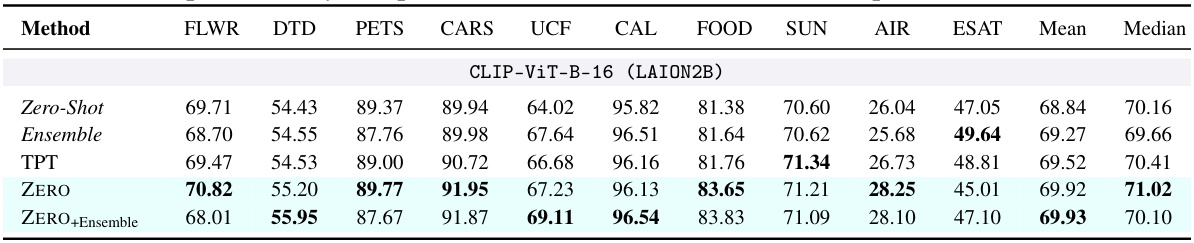

This table presents the results of fine-grained image classification experiments using the CLIP-ViT-B-16 model pretrained on a large language dataset. Multiple test-time adaptation (TTA) methods are compared against a zero-shot baseline. The table shows the top-1 accuracy achieved by each method on 10 different datasets, highlighting the best-performing method for each dataset.

This table presents the results of applying several Test-Time Adaptation (TTA) methods to vision-language models (VLMs) on datasets designed to evaluate robustness against natural distribution shifts. The methods are grouped by the baseline VLM used, and top-1 accuracy is reported. The table allows for a comparison of the performance of different TTA techniques across various datasets and baselines, highlighting the best performing method within each group.

This table presents the results of the experiment on natural distribution shifts for various test-time adaptation (TTA) methods. The methods are grouped by the baseline vision-language model used. For each group, the table shows the top-1 accuracy for each dataset (ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, ImageNet-Sketch), and the average accuracy across datasets. The best performing method in each group is highlighted in bold. The table provides a comparison of different TTA strategies in handling challenging, out-of-distribution data.

This table compares the zero-shot accuracy of CLIP, its accuracy on augmented datasets (created using the method described in Section 3.1), and the accuracy of ZERO (with a percentile of 0.1) on 10 fine-grained classification datasets. It also calculates the difference in accuracy between zero-shot CLIP and the augmented version (Gap) and the improvement achieved by ZERO compared to zero-shot CLIP (Improvement). A negative Spearman’s correlation (-0.95) between Gap and Improvement suggests that when the negative impact of augmentations is smaller, ZERO provides greater improvements. This implies that ZERO’s effectiveness is enhanced when the quality of augmented views is higher.

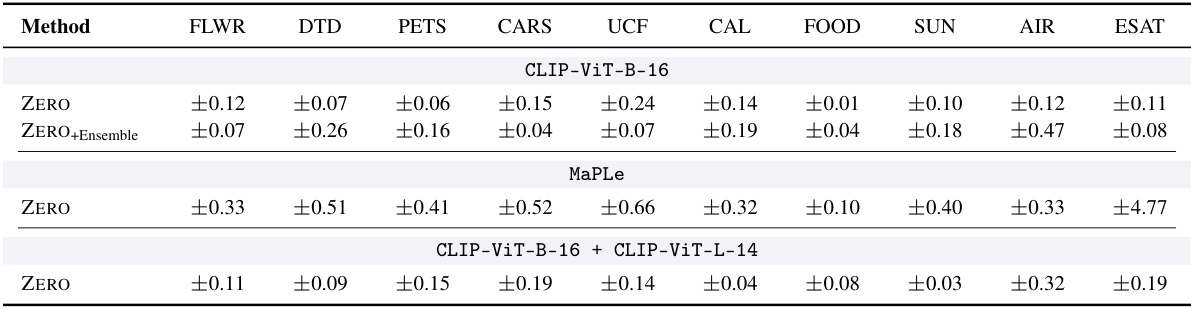

This table shows the standard deviations for the ZERO method’s top-1 accuracy results on 10 fine-grained classification datasets. The standard deviations are broken down by model (CLIP-ViT-B-16, MaPLe, CLIP-ViT-B-16 + CLIP-ViT-L-14) and variant (ZERO, ZERO+Ensemble). Each value represents the standard deviation calculated across three separate runs for each dataset.

Full paper#